Abstract

The fatigue and fracture behavior of hard tissues are topics of considerable interest today. This special group of organic materials comprises the highly mineralized and load-bearing tissues of the human body, and includes bone, cementum, dentin and enamel. An understanding of their fatigue behavior and the influence of loading conditions and physiological factors (e.g. aging and disease) on the mechanisms of degradation are essential for achieving lifelong health. But there is much more to this topic than the immediate medical issues. There are many challenges to characterizing the fatigue behavior of hard tissues, much of which is attributed to size constraints and the complexity of their microstructure. The relative importance of the constituents on the type and distribution of defects, rate of coalescence, and their contributions to the initiation and growth of cracks, are formidable topics that have not reached maturity. Hard tissues also provide a medium for learning and a source of inspiration in the design of new microstructures for engineering materials. This article briefly reviews fatigue of hard tissues with shared emphasis on current understanding, the challenges and the unanswered questions.

Keywords: bone, cementum, dentin, enamel, fatigue crack growth, fracture toughness

1. INTRODUCTION

Within the last decade there has been an increase in the number of studies aimed at understanding fatigue of hard tissues. This is not a new subject as published work on fatigue of bone appeared over 50 years ago [1]. The rise in interest is for good reason and can be attributed to a number of factors. Hard tissues represent those that are highly mineralized (comparatively, and generally over 40% mineral by volume) and are principally load bearing. Based on the cyclic nature of loads transmitted in the oral environment and throughout the skeletal system, progressive degradation of these materials through “fatigue” is a relevant concern. In addition, there has been an increase in the average lifespan of both men and women, and most of these individuals seek to maintain an active life, an essential element of longevity [2, 3]. That places greater physical demands on the human body, and over an extended period of time. Simply put, these realities equate to a greater number of cycles that the skeletal system must endure, and fatigue has become increasingly relevant.

Some of the developing interest in fatigue of hard tissues appears to come from the new understanding itself, and the promise of improved diagnostic technologies. For example, there is now greater interest in development of methods/models for predicting and/or preventing failures that originate from damage identified within hard tissues (e.g. identification of flaws using imaging techniques and prescribing interventions) [4]. Some of this new understanding is leading to a greater awareness that there are certain physiological conditions that increase the fragility and/or susceptibility of these tissues to fatigue [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. While much of the interest in this topic is focused on the development of knowledge to address obstacles to lifelong health, there is expanding interest in the opportunities for applying this knowledge towards the development of bio-inspired materials and structures [11, 12]. And despite all the immediate and tangible applications of knowledge from studies on fatigue of hard tissues, there are some less obvious, but equally valuable rewards. These natural composites possess fascinating microstructures that are a delight to study and learn from.

2. MICROSTRUCTURE

There are a total of four hard tissues in the human body that includes bone, cementum, dentin and enamel. Interestingly, all four of these tissues are located in the oral environment and only one is located both within and external to this environment (i.e. bone). Bone, cementum and dentin are very similar in that all three are connective tissues, each is comprised of the same principle constituents, and are roughly a balance of organic and inorganic material by volume. The structure of these materials plays an important role on their fatigue behavior and is an essential topic for this review. A comparison of the density and some selected mechanical properties of the hard tissues is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Typical range of some physical and mechanical properties of the hard tissues.

| Property | Bone | Cementum | Dentin | Enamel | Ti6Al4V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm3) | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.1–2.2 | 3.0 | 4.4 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | 12–21 | 2–20 | 12–20 | 70–110 | 114 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 60–130 | N/A | 60–100 | 10–70 | 900–1200 |

| Fracture toughness (MPa m0.5) | 2–8 | N/A | 1.5–2.1 | 0.7–2.1 | 70–100 |

| Endurance strength (MPa)a | 23b | N/A | 24.44b | N/A | 300c |

| m (power law exponent) | 4–10 | N/A | 10–20 | 6–9 | 4 |

| ΔKth (MPa m0.5) | ~0.5 | N/A | ~0.6 | ~0.4 | 4.6 |

Stress amplitude reported or apparent at 106.

Zero to tension (flexure).

Fully reversed.

2.1 Bone

Cortical bone comprises the outer shell of bones of the skeletal system and is comparatively dense with regards to the more porous interior cancellous (trabecular) bone (Fig. 1(a)). Based on its architecture and composition, cortical bone is often described as a complex hierarchical composite [13, 14] as it exhibits important structural elements operating from the nanoscale to the mesoscale. By volume it is comprised of approximately 50% mineral and 50% organic matter (with approx. 25% collagen and 25% water). Cortical bone is comprised of type I collagen fibrils (approximately 50 to 70 nm diameter and a few micrometers in length) that are bound and supported by an arrangement of carbonated apatite nanocrystals (of roughly 2–3 nm thickness, 30 to 60 nm width and up to 100 nm length) [13]. The collagen fibrils and apatite crystals combine to form mineralized fibrils (or bundles, much less than a micrometer in diameter), which are then organized into a lamellar structure with adjacent lamellae oriented orthogonally, and with thickness between 3 and 7 μm [14]. On a microscopic scale cortical bone is traversed by a sparse distribution of canals, i.e. the Haversian canals (50 to 90 μm in diameter), which are aligned along the long axis of bone. Each of the canals is surrounded by the lamellae in a concentric fashion, which form the osteon, i.e. the basic metabolic unit [15, 16]. In adults the individual osteons are “secondary osteons” (not original) and are bounded by the cement sheaths or “cement lines” as they appear when viewed in cross-section (Fig. 1(a)). While the composition is still under evaluation, there is evidence that the cement line exhibits lower collagen content [17, 18] and a slightly different mineral composition [19] than the osteons.

Figure 1.

Unique from the other hard tissues, bone has the capacity to undergo self-repair, a coordinated process of resorption and remodeling controlled at the cellular level [20]. There is strong evidence that micro-damage arising from fatigue triggers the remodeling process, or at least plays a role in its initiation [21, 22]. Remodeling is important to this topic as damaged bone is replaced by the deposition of new bone; secondary osteons develop and replace existing primary or secondary osteons. As such, there is an increase in the number and density of cement lines, as well as a reduction in the osteon size and increase in number of Haversian Canals over the course of one’s life [19, 23].

Trabecular bone is viewed as a cellular solid and is differentiated from cortical bone by its large porosity and mosaic structure (Fig. 1(a)). Morphological evaluations have shown that the bone volume fraction varies widely with anatomic site, ranging from 5% to up to 60 % [24]. The basic structural element is the trabeculae, which are both rods and plates of boney tissue. Like cortical bone, the trabeculae are comprised of lamellae that are derived from an assembly of the same primary constituents. But the lamellae in trabecular bone are arranged longitudinally along the trabeculae and not in a Haversian system. Due to the site-specific cellular architecture, the mechanical behavior is often described with regards to the density. There are excellent reviews covering this topic [24, 25].

2.2 Cementum

The cementum serves as one of the primary connective tissues of the periodontium and exists between the root dentin and alveolar bone (Fig. 1(b)). It occupies a region that is comparatively thin near the junction with enamel (< 100 μm), but ranges from roughly 100 to 300 μm thick near the root apex [26]. Cementum is approximately 45% to 50% hydroxyapatite, with the remainder comprised of the organic components including collagen and non-collagenous matrix proteins [26, 27].

A detailed description of the microstructure that supports an understanding of the mechanical behavior of this tissue appears to be developing. In a simplistic sense, the cementum is characterized according to whether it contains cells or not. Acellular cementum (i.e. primary cementum), located most adjacent to the dentin, comprises the majority of tissue in the upper two thirds of the root. In general, cellular cementum (i.e. secondary cementum) occupies the lower third of the root region [26], but there are spatial variations in this distribution, and regions in which the acellular and cellular regions alternate. There is further subdivision of the acellular cementum into intrinsic (i.e. afibrillar) and extrinsic fiber structures. The latter is comprised of collagen fibril bundles that are of lower mineralization and extend orthogonal or oblique to the tooth root; it also contains extensions of the collageneous Sharpey’s fibers from the periodontal ligament. The former is located closest to the tooth surface and comprised of more highly mineralized fibrils that run essentially parallel to the root surface and orthogonal to the extrinsic fibers. Cellular cementum is comprised of both intrinsic afibrillar and extrinsic fiber structures that appear to be oriented mostly normal to the root surface. Cellular cementum also contains cementoblasts, which contribute to the deposition of cementum in phases throughout life. But unlike bone, the cementum is not capable of remodeling.

2.3 Dentin

Like bone, dentin exhibits a complex hierarchical structure [28] and is comprised of both organic and inorganic components. Dentin is comprised of approximately 45% mineral and 55% organic material (33% collagen and 22% water) by volume [26]. On a microscopic scale the most distinct features are the dentin tubules (Fig. 1(b)), which are a network of microscopic channels that extend radially outward from the pulp towards the dentin-enamel junction (DEJ) and cementum with density range from 20,000 to 60,000 to per mm2 [29]. The tubules decrease in diameter from approximately 2.5 μm (near the pulp) to less than 1 μm (at the DEJ). Each tubule is bounded by a highly mineralized cuff of peritubular dentin consisting of apatite crystals [26]. The region between the tubules is regarded as the intertubular dentin and consists of a collagen fibril mesh oriented essentially perpendicular to the tubules and bound by apatite crystallites [28, 30]. The collagen fibrils have diameter of between 50 to 100 nm, whereas the apatite crystals have approximately 5 nm thickness and remaining dimensions dependent on distance from the pulp (needle-like at pulp and plate-like at DEJ) [31]. Dentin is incapable of remodeling, which raises the importance of damage introduced within this tissue and the potential for degradation of the structural behavior with cyclic loading.

2.4 Enamel

Enamel, the outermost tissue of the human tooth, serves as a protective enclosure for the dentin and the vital pulp (Fig. 1(a)). Comprised of approximately 87% mineral and only 13% organic matter (2% protein and 11% water) by volume, enamel is the most highly mineralized tissue of the human body [26, 32]. The inorganic portion is largely comprised of carbonated hydroxyapatite crystals in the form of nano-scale rods (~25 to 30 nm thick, ~60 to 70 nm width and considerably greater length) that systematically combine to form long ‘keyhole’ shaped rods (4–8 μm in diameter) [26, 32]. These micro-scale rods are the enamel “prisms” and arranged in a columnar fashion, extending from the dentin enamel junction (DEJ) to the occlusal surface. The rods are partially surrounded by a sheath (t ≪ 1 μm) of non-collagenous organic matrix, the composition of which differentiates it from the other hard tissues.

3. FATIGUE BEHAVIOR

The fatigue properties of cortical bone and dentin were recently reviewed by Kruzic and Ritchie [33]. That detailed treatment addresses the fatigue behavior from a mechanistic perspective and includes work on human tissues as well as that of other animals (bovine, elephant, equine, etc). It is an informative review. Here, in the interest of brevity, the effort is primarily focused on studies on human tissues and a presentation of important highlights. It also extends the discussion to trabecular bone, cementum and enamel. There is also more emphasis on the importance of aging and other factors on the fatigue behavior.

3.1 Bone

Cortical Bone

Of the four hard tissues, the fatigue behavior of cortical bone has received the most attention and over the longest period. Much of the interest is associated with the development of stress fractures that occur with intense activity and the incidence of fragility fractures in the elderly [34]. Early work showed that human bone exhibits a traditional fatigue life response (analogous to engineered metals), but that bone undergoes considerable time-dependent deformation. Of importance, Carter and Caler [35] noted that tissue from young individuals exhibited superior fatigue resistance, an early forecast that aging is important to the fatigue response. A related study by this team showed that the time to failure of bone is a function of the cumulative creep and fatigue damage [36]. A transition in behavior was identified where creep dominated the responses for cyclic stress range (Δσ) exceeding 60 MPa as shown in Figure 2. At lower stresses the life was primarily a function of the accumulation of fatigue damage.

Figure 2.

Fatigue tests performed at different frequencies have demonstrated that stress-based models predict time to failure of human cortical bone better than cycles to failure [37, 38]. Moreover, the permanent strain that evolves with fatigue of bone can be estimated by models developed for creep [39]. The creep deformation in bone has been attributed to dissociation of the hydroxyapatite crystals from the organic matrix, causing increase in load transfer to the collagen and viscoplastic deformation of the fibrils [40]. The nature of degradation in bone with cyclic loading is also dependent on the stress ratio. For example, zero to tension fatigue of human femoral bone promoted time dependent degradation (i.e. creep), whereas zero to compression loading promoted cyclic damage only [37]. A fractographic analysis showed that cyclic tension resulted in failure at the cement lines and promoted osteonal pullout, whereas cyclic compression caused failure on an oblique plane consistent with the maximum shear stress, which is consistent with the earlier work of Carter and Hayes [41] with bovine bone.

Due to the difficulties in working with human tissues, experimental studies in this area are often conducted with animal tissues. But subtle differences in microstructure can be of tremendous importance. A comparison of bovine femoral bone (lamellar bone) and red deer antler (ostoenal bone with slightly lower mineralization) under zero to tension loading showed that bone exhibited the highest fatigue strength [42]. However, the antler was far more damage tolerant and underwent a reduction in modulus prior to failure almost 3 times greater than that of bone. Besides the contribution of microstructure, differences in the fatigue strength of bones across species [43] have also been attributed to the stressed volume and population of intrinsic defects [44]. Changes in the microstructure of bone that result from remodeling are also important here. An evaluation of stress life fatigue in cyclic tension, compression and shear found that heterogeneity in the hardness between the osteons and interstitial areas (a by-product of remodeling) was the most important factor to the fatigue response [10]; the fatigue strength decreased with increasing heterogeneity. That observation is unique from the notion that remodeling increases the fatigue strength as new secondary osteons are significantly more effective at arresting fatigue cracks than old osteons [45]. Yet, remodeling appears to play an essential role in preventing fragility failures as there is a reduction in the fracture toughness of bone with increasing degree of microcracking [46].

After the coalescence of damage has progressed to the initiation of a well-defined flaw, fatigue crack propagation ensues in this tissue. Few studies have examined fatigue crack growth of cortical bone. The earliest were conducted with bovine [47] and equine [48] bone. Recent work has provided a mechanistic understanding of fatigue crack growth in human bone [49, 50] for cyclic extension parallel to the ostoens. Overall, cyclic crack extension in these studies occurred over a stress intensity range (ΔK) of 0.5≤ΔK≤3.0 Mpa·m0.5 with growth rates ranging from 2×10−7 to 3×10−2 mm/cycle. Utilizing the conventional power law [51] for modeling the steady state region of response the growth exponents ranged from 4.4 to 9.5 (Table 1). The fatigue crack growth behavior of compact human bone is influenced by the magnitude of stress and the contributing mechanisms (cyclic and time-dependent). At low cyclic driving forces (ΔK ≤ 1 Mpa·m0.5) crack growth appears to be enabled by alternating blunting and resharpening of the crack tip, i.e. true fatigue. Yet, at higher driving forces the crack extends primarily by static processes (i.e. creep) with only minor assistance from cyclic loading. This behavior is similar to the contributions of creep to the S-N response noted by Carter and Caler [36] and discussed by Taylor [34]. Cyclic extension occurred primarily along the cement lines [49]. Also, the crack path was littered with so-called “uncracked ligament bridges”, which act to bridge the crack and increase the resistance to fracture through the reduction in the local stress intensity. This extrinsic mechanism of toughening is the primary component [52] responsible for the rising R-curve behavior of human bone [53, 54]. And in evaluations on the propagation of small surface cracks (a ≤ 1 mm) in bone [50, 55] the formation of these ligaments promote deceleration and arrest of fatigue cracks (Fig. 3), consistent with short crack behavior of more common extrinsic toughening materials [56].

Figure 3.

Trabecular Bone

In contrast to the large number of studies on cortical bone, very few studies have examined fatigue of human trabecular bone [9, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61]. This is rather surprising since loosening of implants is often related to fatigue of trabecular bone [62].

Due to the difficulties of gripping the rather porous and delicate architecture, experimental studies of trabecular bone are commonly performed under cyclic compression. A clever study performed by Choi and Goldstein [57] compared fatigue of trabecular and cortical human bone using miniature beam specimens (approx. 0.12×0.12×1.5 mm) tested in 4-point loading. The beams were prepared from single trabeculae or cortical bone, thereby minimizing the influence of bone volume fraction (or porosity). The fatigue strength of trabecular bone was 20% to 40% lower than the cortical bone, the degree of difference increasing with life. The difference in fatigue behavior was rationalized by the unique microstructure; the specimens of cortical bone contained a single or no cement lines, whereas the plate-like assembly of lamellae in trabecular bone resulted in many cement lines. Those orientated normal to the maximum principal stress served as potent defects for crack initiation.

The fatigue behavior of trabecular bone follows the traditional S-N behavior. Moreover, the tissue undergoes a reduction in modulus with cyclic loading and there is substantial evidence of creep. A comparison of the fatigue responses for bovine and human trabecular bone showed that they are consistent and can be modeled using a single power law relation if the yield strain is included in the assessment [58]. The conformity in responses suggests that while the monotonic behaviors are site specific (due to density variations), the dominant cyclic processes regulating fatigue are occurring at the ultrastructural level. Indeed, the current opinion concerning mechanical degradation induced by fatigue appears to be that the damage initiation and propagation is regulated by the trabeculae [61]. Orientation of the trabeculae contributes to anisotropy in the fatigue behavior (Figure 4). Nevertheless, a detailed mechanistic evaluation of fatigue and fracture in trabecular bone, like that developing for cortical bone [63, 64], has not been presented.

Figure 4.

Aging of Bone

Experimental studies have reported that the elastic modulus, strength and toughness of human bone decrease with individual age [65, 66, 67]. There are also notable variations in the R-curve behavior with age including a reduction in both the initiation toughness and growth toughness [64, 68]. Despite evidence that aging is important to the fatigue behavior [69], this topic has received limited attention and remains an important area of research. There has been some effort in understanding the formation and accumulation of microcracks in aged cortical bone [70, 71]. This work suggests that both the rate of accumulation and severity of microcracks increase with individual age. Microcracking in bone is discussed in more detail in earlier reviews [33, 34]. It is clear that there is a reduction in the fatigue strength of cortical [10, 69] and trabecular [9] bone with age. But the most recent evaluation of cortical bone showed that the fatigue behavior was more highly correlated with heterogeneity between the osteon and interstitial areas than with donor age [10]. The degradation is potentially attributed to the increasing cement line density, and properties of the collagen matrix [72, 73, 74, 75], both of which could reduce the damage initiation resistance and the extent of intrinsic mechanisms of crack growth toughening.

It is important to recognize that age is not a physical parameter, but simply serves as an indice for the apparent microstructural changes. There is an increase in microcrack density of bone with age [70] that triggers remodeling, but there is also an increase in porosity with repeated bone turnover, as well as with the incidence of osteoporosis [76]. Age-related fragility fractures are generally attributed to a reduction in bone mass and/or reduction in bone mineral density (BMD). An alternative to this belief contends that the degradation is due to high rates of remodeling [77]. That would promote an increase in number of secondary osteons and cement line density, thereby reducing the degree of extrinsic toughening available for promoting crack growth resistance. Studies aimed at characterizing fatigue response in terms of the remodeling rates, and secondary osteon size could provide new insight, but will require improved methods for studying remodeling in a quantitative manner. Of equal importance, there are differences in the age-dependent remodeling rates between individuals of specific ethnic backgrounds [77], which could contribute to the rate of degradation in fatigue behavior with age. These issues are of substantial importance and offer opportunities for interesting research.

3.2 Cementum

The cementum has two primary mechanical functions, namely to facilitate anchoring the tooth to the alveolar bone and to serve as a partial shock absorber with the periodontal ligament. Of the four hard tissues considered, evaluations on the mechanical properties of the cementum are comparatively rare. Ho and colleagues [27, 78, 79] have performed some recent investigations and reported some new information on structure and mechanical behavior. These mechanical assessments have focused on hardness and elastic modulus using nanoindentation methods. Similar to the structure, the mechanical behavior exhibits substantial hetereogeneity as evident from the large range in elastic modulus (Table 1). No studies have been reported on the fatigue behavior of this tissue. There is limited cementum available for such studies and, undoubtedly, a number of consequent difficulties. Nevertheless, there appears to be a wealth of valuable information here regarding the design of fatigue resistant adhesive systems and joints that require both rigidity and energy dissipation. The cementum promises to be an interesting material to learn from and one that will likely receive considerable attention in the future.

3.3 Dentin

Interest in the fatigue properties of dentin emerged only a decade ago [80]. That is surprising considering that cyclic stresses caused by thermal “fatigue” were reported to induce cracks in teeth much earlier [81] and that tooth fracture has been a significant problem in restorative dentistry [82, 83]. Studies on fatigue of human dentin have distinguished that dentin exhibits the traditional S-N response [5, 6, 68, 84, 85]. Collectively these studies have established that dentin exhibits an apparent endurance limit that ranges from approximately 20 to 50 MPa, and that it is dependent on the frequency of loading [84], the mean stress [68] and the tubule orientation [85]. Orientation of loading relative to the tubules is important due to the range of loading conditions posed by cyclic contact and the changes caused by introduction of a restorative material [86]. The apparent endurance strength of dentin (defined at 107 cycles) is 24 and 44 MPa for tissue with tubules aligned parallel and perpendicular to the maximum normal stress (Fig. 5(a)) [85]. The difference is attributed to the collagen fibrils, which are oriented roughly perpendicular to the tubules [31]. Note that the microstructure of dentin is misleading as the peritubular cuffs look like reinforcing fibers in a fibrous composite. However, the mineralized collagen fibrils, which are generally not visible in a microscopic assessment, are primary contributors to anisotropy in the fatigue behavior.

Figure 5.

Similar to bone, dentin exhibits greater fatigue life and larger apparent endurance strength at higher load frequencies [84]. An analysis of the responses in terms of time to failure revealed time dependence and raised some question as to whether the cyclic response is “true” cyclic fatigue. But further work by this group using elephant dentin has established that the cyclic responses are true cyclic fatigue that is assisted by time dependent degradation [87]. A related study considering mean stress effects distinguished that there is a reduction in the fatigue life of dentin with increasing tensile mean stress and increasing stress ratio [53]. That study also found that the lifetime data were bounded by the Gerber parabola [88] at lower lives and by the Goodman line [89] at longer lives, a quality that is consistent with the behavior of most engineering metals [56].

Fatigue crack growth in dentin was initially studied using tissue of bovine teeth [90, 91]. The first study performed with human dentin utilized a compliance approach [84]. Cyclic extension followed a power law form with a growth exponent of 8.76 and a stress intensity threshold of ΔKth =1.06·MPa m0.5. Cyclic growth characterized using the direct crack measurement approach [7] provided considerably higher growth exponent (13.3±1.3) and lower ΔKth (0.7 MPa·m0.5), quantities indicating that dentin is highly susceptible to fatigue crack growth. Interestingly, fatigue crack growth surfaces in dentin exhibit striations (Fig. 6). A comparison of striation patterns from laboratory specimens and crack surfaces in restored teeth has been used to estimate the cyclic stresses contributing to fatigue crack growth in vivo [8]. Flaws introduced during restorative practices may play an important role in the incidence of tooth fractures. Indeed, cracks exceeding 100 μm in length have been identified in preparation of dentin using lasers for hard tissue ablation [92]. Surprisingly, no study has distinguished contributions from the surface integrity on the fatigue life of dentin.

Figure 6.

Though the characteristics of intrinsic flaws in dentin are not well understood, a quantitative assessment of the critical flaw size and cyclic stress envelope promoting fatigue failure has been performed. Kruzic and Ritchie [4] adopted the Kitagawa and Takahashi [93] and El Hadad [94] methods, which enable a marriage of the stress-life and damage tolerant approaches. A Kitagawa – Takahashi diagram was constructed for a stress ratio (R) of 0.1 and conditions where the tubules were oriented parallel to the maximum cyclic stress. The information detailed by a Kitagawa-Takahashi diagram for dentin (or any tissue) may provide clinicians a means of assessing the risk of fractures, provided that the flaws can be imaged prior to reaching instability. But that diagram has also been used to describe the relative anisotropy of dentin’s fatigue behavior in terms of flaw size for flaws oriented parallel (0°), oblique (45°) and perpendicular (90°) to the tubules (Fig. 5(b)) [95]. Evident here, human dentin undergoes a transition from fatigue to fatigue crack growth at the lowest cyclic stress range when the tubules are aligned with the direction of cyclic stress. Using the ratio of critical stress range (Δσc) to quantify the degree of anisotropy (r = Δσc(max)/Δσc(min)), r = 2 within the stress-life regime and reduces to approximately 1.2 under fatigue crack growth. Human dentin exhibits the largest degree of anisotropy within the stress-life regime (i.e. short crack regime), indicating that structural anisotropy plays the largest role on the accumulation of damage and crack initiation.

Aging of Dentin

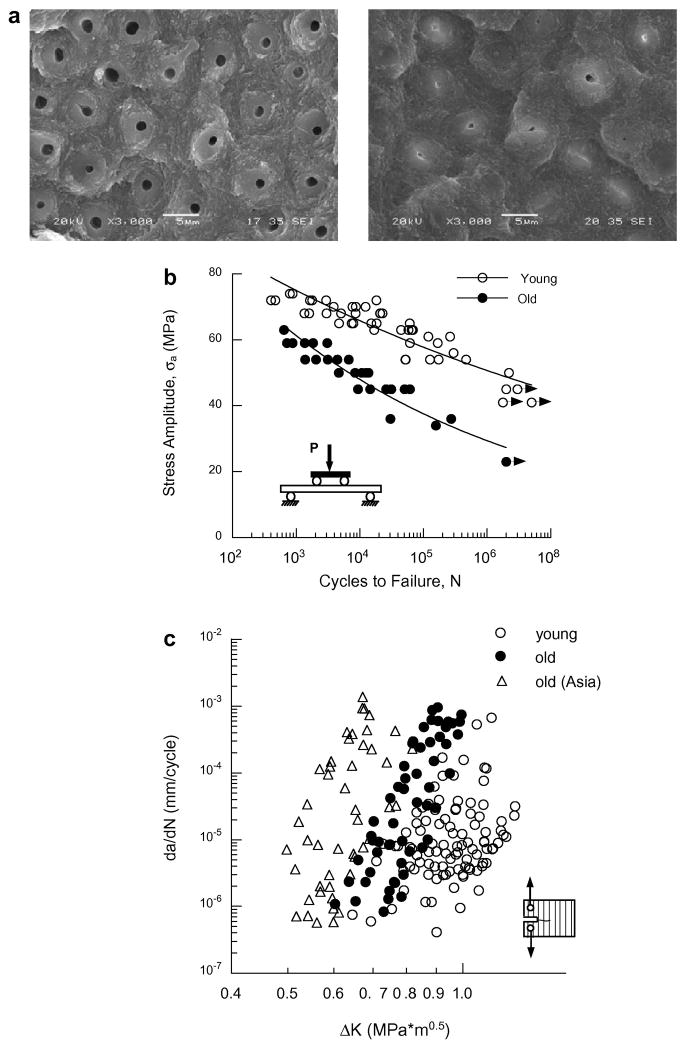

The importance of aging on the mechanical behavior of dentin was recently reviewed by author [96]. Aging of dentin is accompanied by a reduction in the tubule diameter due to the deposition of mineral within the lumens (Figure 7(a)). This process begins in the third decade of life and results in an increase in mineralization [6, 97]. After an adequate degree of mineral is deposited within the tubules the tissue appears transparent. There are also some changes in the mineralized collagen matrix with aging, but this is less well understood [98, 99]. Independent studies of the R-curve behavior for crack extension parallel (in plane) [100, 101] and perpendicular [102] to the dentin tubules report significant reductions in the crack growth resistance of dentin with age. Yet, studies of the fatigue behavior have reported slightly conflicting responses. Kinney et al [6] found that transparent dentin (from old individuals) exhibited lower apparent fatigue strength for lives from 103 to 105 cycles, but negligible difference for 106 cycles. In contrast, Arola and Reprogel [5] showed that old dentin exhibits significantly lower fatigue life than that of young dentin, throughout the stress-life range (Fig. 7(b)). The ratio of endurance strength (at 107) to ultimate strength for young and old dentin is approximately 0.5 and 0.38, respectively. These ratios are well within the range reported for engineering metals [56]. The smaller ratio for old dentin emphasizes the increased sensitivity to fatigue, and contributions from the change in microstructure.

Figure 7.

Age is also important to the fatigue crack growth resistance of dentin. The Region II crack growth responses for young and old (50 ≤ individual age) dentin are shown in Figure 7(c). Though the average fatigue crack growth exponent for the old dentin (m=21.6±5.2) is significantly greater than that of the young dentin, differences are most evident in the average rate of fatigue crack growth [7]. The average rate of fatigue crack growth in the old tissue is more than 100 times greater than that in young dentin. Thus, cracks introduced within dentin during routine restorative procedures are far more likely to cause tooth fracture in senior patients. Note that the comparison of fatigue crack growth responses (Fig. 7(c)) also includes data for senior individuals from Asia with comparable age distribution. Results from this preliminary study indicate that there are significant differences in the fatigue properties between the dentin of these two different ethnic groups [103]. Further work is presently underway to establish how ethnic background and/or diet contribute to the aging process and the fatigue properties of this hard tissue.

Unique from bone, the reduction in fatigue resistance of dentin with age is associated with an increase in density, not a reduction, and through a decrease in number of natural stress concentrations by filling of the dentin tubules. Though flaws have been distinguished to be an important contributor to the structural behavior of dentin [6], no study has characterized these flaws, and whether there are intrinsic flaws in this tissue. One aspect of the fatigue behavior of dentin that has not been addressed is the spatial dependence. Evaluations reported thus far have been primarily limited to coronal dentin. The tubule density is greater within the tooth root and the age-related microstructural changes begin in the tooth root and progress coronally [104]. There would be some value in establishing if there are differences in the fatigue properties of root and coronal dentin and if the degradation in fatigue properties of root dentin begins at an earlier age, or are more severe.

3.4 Enamel

Due to its high mineral content, the enamel of teeth would be expected to exhibit limited resistance to fatigue and fatigue crack growth. Indeed, cracks or craze lines are commonly viewed on the surface of teeth, but these seldom lead to tooth fracture. They are potentially arrested at the Dentin Enamel Junction (DEJ) [105], or immediately beneath the enamel within the mantle dentin [106]. Nevertheless, the fatigue properties of enamel have received limited attention.

To the author’s knowledge no study has been reported on the stress-life fatigue behavior of enamel. The fatigue crack growth resistance of enamel has been recently studied using a novel approach that embodies a small piece of enamel within a miniature CT specimen [107, 108]. Measures of cyclic extension parallel to the prisms have shown that enamel exhibits prominent short-crack behavior [56] and then transitions to a long-crack response (Fig. 8(a)). Fatigue crack growth initiates at a relatively low stress intensity range (ΔKo = 0.39±0.09 Mpa·m0.5) and continues to instability at ΔK of 0.65±0.14 MPa·m0.5, much less than half the reported fracture toughness [108, 109]. Using a Paris model to characterize the steady-state responses, the exponent ranges from 5.6 to 9.2 [107]. These values are not substantially different from those of some common monolithic engineering ceramics. But in comparing the fatigue crack growth responses with that of sintered hydroxyapatite (HAp) having nearly identical crystallinity, chemistry and density, the HAp required significantly lower driving forces for initiation of cyclic extension (ΔKth ~0.13 MPa·m0.5) and throughout the growth range. A 4% increase in organic content (over that of HAp) and tailored distribution contributes to a 3-fold increase in required cyclic driving force. Surprisingly, the fatigue crack growth resistance of enamel is not substantially lower than that of human bone and dentin (Fig. 8(b)), despite the low mineral content. Hence, the microstructure of enamel is extremely effective in resisting cyclic crack growth in this comparatively hard and brittle material.

Figure 8.

Extrinsic mechanisms of toughening are clearly active in the crack wake (Fig. 9(a)) during both cyclic and monotonic crack growth in enamel. Nearest the anatomic tooth surface (i.e. in the outer enamel) crack extension occurs between and parallel to the prisms (Fig. 9(b)), resulting in crack growth extending directly towards the vital pulp. This would appear a reckless design by nature as cracks reaching the pulp would require tooth extraction. However, this characteristic is actually ingenious as the guided crack is prevented from curving back towards the tooth’s surface and facilitating chipping; the crack is arrested before reaching the dentin. Almost midway through the enamel thickness the prisms undergo crossing, an architecture regarded as decussation. Upon reaching this region the crack undergoes bifurcation (e.g. Fig. 9(c)) and a number of toughening mechanisms develop including bridging induced by unbroken ligaments of tissue (Fig. 9(d)) and crack curving and twisting (Fig. 9(e)). Microcracking about the primary crack and secondary bridging induced by ligaments of organic matter provide further resistance [108]. This concert of mechanisms is extremely effective in promoting retardation and crack arrest. In fact, recent evaluations of the R-curve behavior indicate that these mechanisms result in toughness exceeding 2.0 Mpa·m0.5 [109].

Figure 9.

Teeth subjected to large occlusal loads may develop cracks about the DEJ at natural fissures [110]. That would enable cracks to initiate and extend from the inner enamel outwards (i.e. the “reverse” direction). Measures of cyclic crack extension in the reverse direction show that rates range from 6.7 10−8 to 3.8 10−5 mm/cycle, but that total growth history extends over less than 0.7 mm (far less than the forward direction) [108]. Cyclic extension in the reverse direction occurred almost exclusively in the short crack regime with minimal steady state behavior. The apparent ΔKth for this orientation (0.53 Mpa·m0.5) is nearly 40 % greater than that for the outer enamel and nearly equivalent to that at instability (ΔKc = 0.68 MPa·m0.5). The crack growth resistance was attributed to the same extrinsic mechanisms identified in forward crack growth. However, the mechanisms evolved for growth within the inner enamel only and the crack reached instability prior to escaping the decussated zone. The graded microstructure of enamel achieves an increase in crack growth resistance with cyclic extension and that it is optimized for cracks initiating from the tooth’s surface and propagating inward. That raises questions to participation of the DEJ to crack growth resistance. A study of cyclic crack extension from enamel towards the DEJ indicated that the cracks were deflected to grow along the interface [105]. It is unknown whether the DEJ works in the same capacity for cracks growing from dentin into enamel.

There are a number of remaining components of the fatigue behavior of enamel that remain unknown. For example, the studies conducted thus far have been limited to an examination of fatigue crack growth. The stress life fatigue response is of interest, especially considering the potential for damage to develop as a result of cyclic contact between enamel and engineered ceramics used for crown replacement. And of equal relevance, the influence of microstructural changes induced by chemical treatments on the fatigue properties is a timely concern, but one that has not been addressed. There are also issues related to spatial variations in the fatigue response and whether the properties are consistent throughout the crown of the tooth, or whether there are differences in properties between anterior and posterior teeth. The studies conducted thus far have been limited to an examination of enamel from extracted 3rd molars, teeth that will rarely be enrolled in chewing. There appears to be something to learn from the microstructure of enamel in the design of hard and fatigue-resistant brittle systems. A quantitative evaluation of the anisotropy and a mechanistic evaluation of the response could nurture the development of new microstructures and/or engineered behavior.

4. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

In review of the fatigue behavior of hard tissues there are a number of challenges and remaining questions. Some of these items were presented in the context of the individual tissues. It should be evident from the review that there is a significant extent of degradation in the stress-life and fatigue crack growth properties of bone and dentin with aging. These changes are primary contributors to the increase in fragility fractures and tooth fractures in senior individuals. But the majority of existing knowledge addresses what happens, and there are many remaining questions that involve why and when. For bone, the declining fatigue resistance and fracture toughness appears to be a complicated function of changes in bone mass, rate of remodeling and potential changes in the collagen. In dentin, the reduction in fatigue crack growth resistance can be attributed to the diminished contribution of extrinsic toughening; cause for the reduction in damage initiation resistance and its onset are less well understood. Thus, additional knowledge of contributions from the individual constituents on the mechanisms of fatigue and fracture behavior in the hard tissues is critical. Furthermore, the evaluations conducted thus far have bounded the behavior by extremes (young and old), with less emphasis on the age at which the reduction in fatigue resistance begins, and how it progresses with maturation. This is where the issues related to ethnic background and nutrition may become relevant, making such studies not only interesting, but also worthwhile.

Bone dentin and enamel exhibit substantial anisotropy in their microstructure. In bone, cement lines have been identified as comparatively “weak” interfaces that play an important role in cyclic crack growth, especially in crack deflection [75]. And in enamel, cyclic crack growth occurs almost exclusively along the interprismatic regions and parallel to the rods [109]. In contrast, dentin exhibits the most anisotropy during the initiation of a crack, and apparently less during cyclic crack extension, despite the structural similarity to bone. Little effort has been spent exploring the nature of this anisotropy and if it can be adopted or patterned in engineered systems. Also of interest, to the author’s knowledge no experimental study has quantified the role of remodeling on the fatigue response of bone, or pursued studies on the ability for dentin and enamel to self-repair in the presence of evolving fatigue damage. These are important concepts and have tremendous merit.

Much of the work on fatigue of hard tissues has focused on those occupying the largest volume. Both the enamel and cementum play unique functional roles that are quite different from those of bone and dentin, but have received little attention. The interfaces between these two tissues and dentin are regions that exhibit unique damage tolerance; a mechanistic understanding of their fatigue properties could provide new models for the development of fatigue resistant interfaces. Indeed, biomimetic principles are now being used in the development of tough hybrid materials with hierarchical microstructures that are able to achieve toughness in excess of 300 times their constituents [12, 111]. But these studies are often directed towards maximizing crack growth resistance through biomimetic analogs that achieve extrinsic mechanisms of toughening. There appears to be tremendous opportunities for using these materials to inspire new concepts for resistance to damage initiation, and then the capacity for invoking self repair.

5. CLOSING REMARKS

The pursuit of lifelong health and interest in extending the current definitions of an active and high quality of life have raised the level of interest in the fatigue properties of hard tissues. There has been some progress towards understanding the importance of the microstructure of these materials on their fatigue properties, and contributions from changes related to aging and disease, particularly with bone and dentin. But this area of research has not reached maturity and there are a number of fundamental topics remaining to be addressed. There is still tremendous distance between the knowledge obtained from laboratory studies and the application of this knowledge in medical practice. Due to the complexity of their microstructures, advancements in this area will require a better understanding of the microstructure of these materials and a distinction of contributions from the constituents, acting alone and in concert, on the primary mechanisms of damage initiation and crack growth resistance. These pursuits will undoubtedly fuel investigations in this area for decades to come.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges support from the National Institute of Health through NIDCR R01 DE016904 and NIDCR R01 DE017983.

References

- 1.Evans FG, Lebow M. Strength of human compact bone under repetitive loading. J Appl Physiol. 1957;10:127–130. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1957.10.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shephard RJ. Aging, Physical Activity, and Health, illustrated ed. Human Kinetics Pub Inc; Champaign, IL: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westendorp RG. What is healthy aging in the 21st century? Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:404S–409S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.404S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruzic JJ, Ritchie RO. Kitagawa-Takahashi diagrams define the limiting conditions for cyclic fatigue failure in human dentin. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:747–751. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arola D, Reprogel RK. Effects of aging on the mechanical behavior of human dentin. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4051–4061. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinney JH, Nalla RK, Pople JA, Breunig TM, Ritchie RO. Age-related transparent root dentin: mineral concentration, crystallite size, and mechanical properties. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3363–3376. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajaj D, Sundaram N, Nazari A, Arola D. Age, dehydration and fatigue crack growth in dentin. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2507–2517. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bajaj D, Sundaram N, Arola D. An examination of fatigue striations in human dentin: In vitro and in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;85:149–159. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dendorfer S, Maier HJ, Hammer J. How do anisotropy and age affect fatigue and damage in cancellous bone? Stud Health Technol Inform. 2008;133:68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zioupos P, Gresle M, Winwood K. Fatigue strength of human cortical bone: age, physical, and material heterogeneity effects. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;86:627–636. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deville S, Saiz E, Nalla RK, Tomsia AP. Freezing as a path to build complex composites. Science. 2006;311:515–518. doi: 10.1126/science.1120937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munch E, Launey ME, Alsem DH, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Ritchie RO. Tough, bio-inspired hybrid materials. Science. 2008;322:1516–1520. doi: 10.1126/science.1164865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rho JY, Kuhn-Spearing L, Zioupos P. Mechanical properties and the hierarchical structure of bone. Med Eng Phys. 1998;20:92–102. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(98)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiner S, Wagner HD. The material bone: Structure-mechanical function relations. Ann Rev Mater Sci. 1998;28:271–298. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Currey JD. Mechanical properties of vertebrate hard tissues. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 1998;212:399–411. doi: 10.1243/0954411981534178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Currey JD. Bones: Structure and Mechanics. 2. Princeton University Press; Princeton, New Jersey: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaffler MB, Burr DB, Frederickson RG. Morphology of the osteonal cement line in human bone. Anat Rec. 1987;217:223–228. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092170302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skedros JG, Holmes JL, Vajda EG, Bloebaum RD. Cement lines of secondary osteons in human bone are not mineral-deficient: new data in a historical perspective. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2005;286:781–803. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burr DB, Schaffler MB, Frederickson RG. Composition of the cement line and its possible mechanical role as a local interface in human compact bone. J Biomech. 1988;21:939–945. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(88)90132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jee WSS. The skeletal tissues. In: Weiss L, editor. Cell and tissue biology: A textbook of histology. Urban and Schwartzenberg, Baltimore: 1989. pp. 211–259. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burr DB, Martin RB, Schaffler MB, Radin EL. Bone remodeling in response to in vivo fatigue microdamage. J Biomech. 1985;18:189–200. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(85)90204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burr DB. Remodeling and the repair of fatigue damage. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;53(Suppl 1):S75–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01673407. discussion S80–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson DD. Age changes in bone mineralization, cortical thickness, and haversian canal area. Calcif Tissue Int. 1980;31:5–11. doi: 10.1007/BF02407161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keaveny TM, Hayes WC. A 20-year perspective on the mechanical properties of trabecular bone. J Biomech Eng. 1993;115:534–542. doi: 10.1115/1.2895536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keaveny TM, Morgan EF, Niebur GL, Yeh OC. Biomechanics of trabecular bone. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2001;3:307–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.3.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ten Cate AR. Oral Histology: Development, Structure, and Function. 7. Mosby-Year Book Inc; St. Louis: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho SP, Yu B, Yun W, Marshall GW, Ryder MI, Marshall SJ. Structure, chemical composition and mechanical properties of human and rat cementum and its interface with root dentin. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinney JH, Marshall SJ, Marshal GW. The mechanical properties of human dentin: a critical review and re-evaluation of the dental literature. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:13–29. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pashley DH. Dentin: a dynamic substrate - a review. Scanning Microsc. 1989;3:161–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall GW, Jr, Marshall SJ, Kinney JH, Balooch M. The dentin substrate: structure and properties related to bonding. J Dent. 1997;25:441–458. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(96)00065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinney JH, Pople JA, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ. Collagen orientation and crystallite size in human dentin: a small angle X-ray scattering study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:31–37. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-0006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson C, Kirkham J, Shore R. Dental enamel: Formation to destruction. 1. CRC press; Boca Raton: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kruzic JJ, Ritchie RO. Fatigue of mineralized tissues: Cortical bone and dentin. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2008;1:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor D. Failure processes in hard and soft tissues. In: Milne I, Ritchie RO, Karihaloo BL, editors. Comprehensive structural integrity: Fracture of materials from nano to macro. Vol. 9. Elsevier Inc; Oxford, UK: 2003. pp. 35–96. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carter DR, Caler WE. Cycle-dependent and time-dependent bone fracture with repeated loading. J Biomech Eng. 1983;105:166–170. doi: 10.1115/1.3138401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carter DR, Caler WE. A cumulative damage model for bone fracture. J Orthop Res. 1985;3:84–90. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100030110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caler WE, Carter DR. Bone creep-fatigue damage accumulation. J Biomech. 1989;22:625–635. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(89)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zioupos P, Currey JD, Casinos A. Tensile fatigue in bone: are cycles-, or time to failure, or both, important? J Theor Biol. 2001;210:389–399. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cotton JR, Zioupos P, Winwood K, Taylor M. Analysis of creep strain during tensile fatigue of cortical bone. J Biomech. 2003;36:943–949. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rimnac CM, Petko AA, Santner TJ, Wright TM. The effect of temperature, stress, and microstructure on the creep of compact bovine bone. J Biomech. 1993;26:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90360-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carter DR, Hayes WC. Compact bone fatigue damage: a microscopic examination. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1977;127:265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zioupos P, Wang XT, Currey JD. Experimental and theoretical quantification of the development of damage in fatigue tests of bone and antler. J Biomech. 1996;29:989–1002. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(96)00001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor D. Fatigue of bone and bones: an analysis based on stressed volume. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:163–169. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor D, O’Brien F, Prina-Mello A, Ryan C, O’Reilly P, Lee TC. Compression data on bovine bone confirms that a “stressed volume” principle explains the variability of fatigue strength results. J Biomech. 1999;32:1199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kennedy OD, Brennan O, Mauer P, Rackard SM, O’Brien FJ, Taylor D, Lee TC. The effects of increased intracortical remodeling on microcrack behaviour in compact bone. Bone. 2008;43:889–893. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.07.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yeni YN, Fyhrie DP. Fatigue damage-fracture mechanics interaction in cortical bone. Bone. 2002;30:509–514. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wright TM, Hayes WC. The fracture mechanics of fatigue crack propagation in compact bone. J Biomed Mater Res. 1976;10:637–648. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820100420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gibeling JC, Shelton DR, Malik CL. Application of fracture mechanics to the study of crack propagation in bone. In: Rack H, Lesuer D, Taleff E, editors. Structural Biomaterials for the 21st Century. TMS; Warrendale, PA: 2001. pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Aspects of in vitro fatigue in human cortical bone: time and cycle dependent crack growth. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2183–2195. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kruzic JJ, Scott JA, Nalla RK, Ritchie RO. Propagation of surface fatigue cracks in human cortical bone. J Biomech. 2006;39:968–972. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paris PC, Gomez MP, Anderson WP. A rational analytical theory of fatigue. Trend Eng. 1961;13:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nalla RK, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Mechanistic fracture criteria for the failure of human cortical bone. Nat Mater. 2003;2:164–168. doi: 10.1038/nmat832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Effect of aging on the toughness of human cortical bone: evaluation by R-curves. Bone. 2004;35:1240–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Mechanistic aspects of fracture and R-curve behavior in human cortical bone. Biomaterials. 2005;26:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akkus O, Rimnac CM. Cortical bone tissue resists fatigue fracture by deceleration and arrest of microcrack growth. J Biomech. 2001;34:757–764. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suresh S. Fatigue of Materials. 2. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi K, Goldstein SA. A comparison of the fatigue behavior of human trabecular and cortical bone tissue. J Biomech. 1992;25:1371–1381. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(92)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haddock SM, Yeh OC, Mummaneni PV, Rosenberg WS, Keaveny TM. Similarity in the fatigue behavior of trabecular bone across site and species. J Biomech. 2004;37:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00245-8. Erratum in: J Biomech 39 (2006) 593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamamoto E, Crawford RP, Chan DD, Keaveny TM. Development of residual strains in human vertebral trabecular bone after prolonged static and cyclic loading at low load levels. J Biomech. 2006;39:1812–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rapillard L, Charlebois M, Zysset PK. Compressive fatigue behavior of human vertebral trabecular bone. J Biomech. 2006;39:2133–2139. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dendorfer S, Maier HJ, Taylor D, Hammer J. Anisotropy of the fatigue behaviour of cancellous bone. J Biomech. 2008;41:636–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mann KA, Miller MA, Race A, Verdonschot N. Shear fatigue micromechanics of the cement-bone interface: An in vitro study using digital image correlation techniques. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:340–346. doi: 10.1002/jor.20777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ritchie RO, Kruzic JJ, Muhlstein CL, Nalla RK, Stach EA. Characteristic dimensions and the micro-mechanisms of fracture and fatigue in “nano” and “bio” materials. Int J Fract. 2004;128:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ritchie RO, Kinney JH, Kruzic JJ, Nalla RK. A fracture mechanics and mechanistic approach to the failure of cortical bone. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct. 2005;28:345–371. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Currey JD, Brear K, Zioupos P. The effects of ageing and changes in mineral content in degrading the toughness of human femora. J Biomech. 1996;29:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zioupos P, Currey JD. Changes in the stiffness, strength, and toughness of human cortical bone with age. Bone. 1998;22:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang X, Puram S. The toughness of cortical bone and its relationship with age. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:123–135. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000007797.92559.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nalla RK, Kinney JH, Marshall SJ, Ritchie RO. On the in vitro fatigue behavior of human dentin: effect of mean stress. J Dent Res. 2004;83:211–215. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zioupos P, Wang XT, Currey JD. The accumulation of fatigue microdamage in human cortical bone of two different ages in vitro. Clin Biomech. 1996;11:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(96)00010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schaffler MB, Choi K, Milgrom C. Aging and matrix microdamage accumulation in human compact bone. Bone. 1995;17:521–525. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Norman TL, Wang Z. Microdamage of human cortical bone: incidence and morphology in long bones. Bone. 1997;20:375–379. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zioupos P, Currey JD, Hamer AJ. The role of collagen in the declining mechanical properties of aging human cortical bone. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;45:108–116. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199905)45:2<108::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang X, Shen X, Li X, Agrawal CM. Age-related changes in the collagen network and toughness of bone. Bone. 2002;31:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00697-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ager JW, Nalla RK, Breeden KL, Ritchie RO. Deep-ultraviolet Raman spectroscopy study of the effect of aging on human cortical bone. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:034012. doi: 10.1117/1.1924668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, Balooch M, Ager JW, 3rd, Ritchie RO. Role of microstructure in the aging related deterioration of the toughness of human cortical bone. Mater Sci Eng C. 2006;26:1251–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Poole KE, Compston JE. Osteoporosis and its management. BMJ. 2006;333:1251–1256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39050.597350.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heaney RP. Is the paradigm shifting? Bone. 2003;33:457–465. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ho SP, Goodis H, Balooch M, Nonomura G, Marshall SJ, Marshall G. The effect of sample preparation technique on determination of structure and nanomechanical properties of human cementum hard tissue. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4847–4857. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ho SP, Senkyrikova P, Marshall GW, Yun W, Wang Y, Karan K, Li C, Marshall SJ. Structure, chemical composition and mechanical properties of coronal cementum in human deciduous molars. Dent Mater. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.04.005. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tonami K, Takahashi H. Effects of aging on tensile fatigue strength of bovine dentin. Dent Mater J. 1997;16:156–69. doi: 10.4012/dmj.16.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brown WS, Jacobs HR, Thompson RE. Thermal fatigue of teeth. J Dent Res. 1972;51:461–467. doi: 10.1177/00220345720510023601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cameron CE. The cracked tooth syndrome: Additional findings. J Am Dent Assoc. 1976;93:971–975. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1976.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eakle WS, Maxwell EH, Braly BV. Fractures of posterior teeth in adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986;112:215–218. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1986.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nalla RK, Imbeni V, Kinney JH, Staninec M, Marshall SJ, Ritchie RO. In vitro fatigue behavior of human dentin with implications for life prediction. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66:10–20. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arola D, Reprogel RK. Tubule orientation and the fatigue strength of human dentin. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2131–2140. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arola D, Galles LA, Sarubin MF. A comparison of the mechanical behavior of posterior teeth with amalgam and composite MOD restorations. J Dent. 2001;29:63–73. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kruzic JJ, Nalla RK, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Mechanistic aspects of in vitro fatigue-crack growth in dentin. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gerber H. Bestimmung der Zulassigen Spannungen in Eisen-konstruktionen. Z Bayer Arch Ingenieur-Vereins. 1874;6:101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goodman J. Mechanics applied to engineering. 9. Longmans, Green and Co; London: 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arola D, Rouland JA, Zhang D. Fatigue and fracture of bovine dentin. Exp Mech. 2002;42:380–388. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arola D, Rouland JA. The effects of tubule orientation on fatigue crack growth in dentin. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;67:78–86. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Staninec M, Meshkin N, Manesh SK, Ritchie RO, Fried D. Weakening of dentin from cracks resulting from laser irradiation. Dent Mater. 2009;25:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kitagawa H, Takahashi S. Applicability of fracture mechanics to very small cracks or the cracks in the early stages. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Mechanical Behavior of Materials; Metals Park, OH: ASM; 1976. pp. 627–631. [Google Scholar]

- 94.El Haddad MH, Topper TH, Smith KN. Prediction of non propagating cracks. Eng Fract Mech. 1979;11:573–584. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Arola D, Reid J, Cox ME, Bajaj D, Sundaram N, Romberg E. Transition behavior in fatigue of human dentin: structure and anisotropy. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3867–3875. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Arola D. Fracture and Aging in Dentin. In: Curtis RV, Watson TF, editors. Dental Biomaterials: Imaging, Testing and Modeling. Woodhead Publishing; Cambridge, UK: 2007. pp. 314–340. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Porter AE, Nalla RK, Minor A, Jinschek JR, Kisielowski C, Radmilovic V, Kinney JH, Tomsia AP, Ritchie RO. A transmission electron microscopy study of mineralization in age-induced transparent dentin. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7650–7660. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walters CDR. Eyre Collagen crosslinks in human dentin: increasing content of hydroxypyridinium residues with age. Calcif Tissue Int. 1983;35:401–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02405067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ager JW, 3rd, Nalla RK, Balooch G, Kim G, Pugach M, Habelitz S, Marshall GW, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. On the increasing fragility of human teeth with age: a deep-UV resonance Raman study. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1879–1887. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Koester KJ, Ager JW, 3rd, Ritchie RO. The effect of aging on crack-growth resistance and toughening mechanisms in human dentin. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1318–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koester KJ, Ager JW, 3rd, Ritchie RO. Aging and fracture of human cortical bone and tooth dentin. JOM. 2008;60:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nazari A, Bajaj D, Zhang D, Romberg E, Arola D. On the reduction in fracture toughness of human dentin with age. J Mech Beh Biomed Mater. 2009;2:550–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bajaj D, Ivancik J, Arola D. Ethnic background influences the crack growth resistance of dentin. J Dent Res. 2008;85(Spec Issue):0438. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carrigan PJ, Morse DR, Furst ML, Sinai IH. A scanning electron microscopic evaluation of human dentinal tubules according to age and location. J Endod. 1984;10:359–363. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(84)80155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dong XD, Ruse ND. Fatigue crack propagation path across the dentinoenamel junction complex in human teeth. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66:103–109. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Imbeni V, Kruzic JJ, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ, Ritchie RO. The dentin enamel junction and the fracture of human teeth. Nat Mater. 2005;4:229–232. doi: 10.1038/nmat1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bajaj D, Nazari A, Eidelman N, Arola DD. A comparison of fatigue crack growth in human enamel and hydroxyapatite. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4847–4854. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bajaj D, Arola D. Fatigue and fracture of human enamel: Role of prism decussation. Acta Biomater. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.04.013. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bajaj D, Arola D. On the R-Curve behavior of human tooth enamel. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4037–4046. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lawn BR, Lee JJW, Constantino PJ, Lucas PW. Predicting failure in mammalian enamel. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2009;2:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Launey ME, Munch E, Alsem DH, Barth HB, Saiz E, Tomsia AP, Ritchie RO. Designing highly toughened hybrid composites through nature-inspired hierarchical complexity. Acta Mater. 2009;57:2919–2932. [Google Scholar]