Abstract

Objective

Increased risk of cancer and other adult diseases have been associated with perinatal exposure to adverse conditions such as stress and famine. Recently, Insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) was identified as the first gene associated with altered expression caused by fetal exposure to poor nutrition. IGF-II regulates fetal development and breast cancer cell survival, in part, by regulating anti-apoptotic proteins through activation of the IGF-I and insulin receptors. African-American (AA) women have a lower overall breast cancer (BC) incidence, however, they present with advanced disease at diagnosis, poorer prognosis and lower survival than Caucasian (CA) women. The reasons for the BC survival disparity are not well understood. We hypothesize that IGF-II plays a role in the survival disparity observed among AA breast cancer patients by stimulating rapid tumor growth, inhibiting apoptosis and promoting metastasis.

Design

This study examines IGF-II expression and regulation of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin in Hs578t (ER−), CRL 2335 (ER−) and CRL 2329 (ER+) breast cancer cells and compares with the expression of these proteins in paired breast tissue samples from AA and CA women by qRT PCR and Western blotting.

Results

IGF-II expression was significantly higher in AA cell lines and tissue samples when compared to Caucasians. IGF-II siRNA treatment decreased antiapoptotic protein levels in all cell lines (regardless of ER status). These effects were blocked by the addition of recombinant IGF-II. Of significance, IGF-II expression and regulation of Bcl-XL and survivin in cell lines correlated with their expression in paired breast tissues.

Conclusions

IGF-II and the antiapoptotic proteins differential expression among AA and CA patients may contribute to the breast cancer survival disparities observed between these ethnic groups.

Keywords: insulin-like growth factor II, Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, Survivin, Breast cancer, African-American, Caucasian, health disparities

Introduction

Differences in breast cancer incidence and mortality rates among multicultural/ethnic populations suggest that etiologic factors differ in their biologic expression and impact on disease outcome: African-American (AA) women have a lower overall incidence of breast cancer than do Caucasian (CA) women, but AA women have a higher overall mortality rate. This survival disparity is particularly pronounced among AA women younger than 45 years, in whom incidence and mortality are higher than in CA women [1].

The insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) plays a pivotal role in fetal and cancer development by signaling through the IGF-I and Insulin receptors, thus regulating proliferation, apoptosis and energy production [2, 3]. Furthermore, transgenic animal models that result in constitutive IGF-II expression also show a significant increase in breast cancer that develops at an early age and is more aggressive [4]. IGF-II promotes proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, and stimulates angiogenesis and transformation of breast cancer cells [5, 6]. We recently demonstrated that IGF-II regulates the anti-apoptotic proteins survivin, Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL in MCF-7 (CA, ER+) breast cancer cells. These survival proteins inhibit mitochondrial membrane depolarization and prevent cell death [7, 8]. We demonstrated that the precursor form of IGF-II (proIGF-II) was more potent than mature IGF-II (mIGF-II) in up-regulating these proteins through increased phosphorylation of IRS-1 at tyrosine 632, which subsequently binds SH2 domains in the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K [8]. ProIGF-II also induced a more potent activation of the Akt pathway, with an earlier and transient activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK cascade. Moreover, activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway has been shown to inhibit the pro-apoptotic protein Bax translocation from cytoplasm to mitochondria, thus promoting cell survival [9]. Inhibition of IGF-II by Resveratrol (RSV) [10] caused the inhibition of all three proteins and stimulated mitochondrial membrane depolarization and apoptosis. Thus, IGF-II plays a critical role in regulating key proteins that are essential in protecting the mitochondria and preventing apoptosis.

Therefore, the present study focuses on IGF-II expression and its regulation of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin in African-American and Caucasian breast cancer cell lines [Hs578t (CA, ER−), CRL 2335 (AA, ER−) and CRL 2329 (AA, ER+)], and demonstrates how the “in vitro” studies correlate with differential expression of IGF-II and subsequently Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin expression among AA and CA breast tissue samples, as part of the mechanism(s) leading to the breast cancer health disparities.

Materials and Methods

Breast cancer tissue specimens

Paired frozen breast cancer and normal tissue specimens were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CHTN) from African-American (AA) and Caucasian (CA) women with ages ranging from 20–90 years (median age per group was African-American malignant (AAM)=60.2 years, Caucasian malignant (CAM)=60.1 years, African-American normal (AAN)=51.9 years and Caucasian normal (CAN)=62.7 years). All malignant samples were stage II or III (AAM stage II n=10, stage III n=17; CAM stage II n=12, stage III n=11). Total number of samples (n) per group is as follows: AAN= 23, CAN= 20, AAM= 27 and CAM= 24. Non-stained slides were also obtained with the tissue specimens as well as a pathology report containing information about patient age, macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of normal and tumor tissues, estrogen/progesterone/Her2 receptors status, and tumor grade/stage and metastases number and sites.

Cell culture

Hs578t (CA, ER−), CRL-2335 (AA, ER−) and CRL-2329 (AA, ER+) breast carcinoma cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C, using DMEM/F12 or RPMI media (ATCC) supplemented with 10 ml of 5,000 units penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/ml penicillin and 100 units/ml streptomycin sulfate, Cellgro), 4 mM L-glutamine (Cellgro), 3 µg/ml β-amphotericin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone). Recombinant human precursor IGF-II (proIGF-II, aa 1–156, non-glycosylated) and recombinant mature IGF-II were purchased from GroPep (Adelaide, Australia), and PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ) respectively. Cell lysates (CL) were collected (9 hrs), centrifuged (800 rpm for 5 min), and kept frozen (−20°C) until assayed.

SiRNA transfection

Hs578t, CRL-2335 and CRL-2329 breast cancer cells were seeded at a density of 5×105 cells/well in 6 well plates. 5pmols siRNA were added to the cells followed by 24 hrs incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were also treated with recombinant human IGF-II (mIGF-II, proIGF-II) for 9 hrs. Cell lysates were prepared using the Complete Lysis-M kit (Roche Applied Science, Germany), according to the manufacturer protocol and stored at −20°C until assayed.

Western blot analysis

Tissue cell lysates (50–75 mg) were prepared in RIPA buffer (1XTBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.004% sodium azide, 10 µl/ml PMSF, 10 µl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail, 10 µl/ml sodium orthovanadate) and used to load polyacrylamide-SDS gradient gels [(4–12%) (30 µg)], transferred to a PVDF membrane (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using X-Cell SureLockR electrophoretic Transfer module (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Protein concentration was measured using the Coomassie Plus Protein Assay Reagent™ (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). PVDF membranes were blocked with 1% BSA IgG free (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in PBS/0.05% Tween for 2 hrs. Membranes were then incubated with anti-IGF-II monoclonal antibody (Amano), anti-survivin monoclonal antibody, anti-Bcl-2 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), and anti-Bcl-XL polyclonal antibody (BD Biosciences) and incubated at 4°C overnight. The blots were also probed with cytokeratin 18 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), used as an epithelial cell marker. After 3 × 10 min washes in PBS/0.05% Tween, the corresponding biotinylated secondary antibodies (1:1000, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) were added to the membranes (1 hr at RT), followed by 3 × 10 min washes and incubation with HRP complexes (1:1000 Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Protein visualization was achieved by using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) and autoradiography with Hyperfilm ECL film (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). The signals on the x-ray films were quantified using ChemiImager™ 4000 (Alpha Innotech Corporation).

RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted using Tri reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 40–70 mg of frozen tissue per sample was homogenized in the Tri reagent by using a hand-held homogenizer (Kontes, Thomas Scientific, NJ). Total RNA was kept at −80° C until assayed.

Real Time PCR

One Step SYBR real-time RT-PCR was performed to assess IGF-II mRNA expression (For- 5’-GAC CGC GGC TTC TAC TTC AG-3’ and Rev- 5’-AAG AAC TTG CCC ACG GGG TAT-3’) survivin (For-5’-TCA AGG ACC ACC GCA TCT CTA C-3’ and Rev- 5’-TGA AGC AGA AGA AAC ACT GGG C-3’), Bcl-2 (For-5’-ATG TGT GTG GAG AGC GTC AAC C-3’ and Rev-5’-AGC CAG GAG AAA TCA AAC AGA GG-3’), Bcl-X (For-5’-GGA AAG CGT AGA CAA GGA GAT GC-3’ and Rev-5’-TCC ACA AAA GTA TCC CAG CCG-3’). GAPDH was used as an internal control (For-5’- ACA ACT TTG GTA TCG TGG AAG GAC-3’ and Rev- 5’- CAG GGA TGA TGT TCT GGA GAG C-3’).

PCR amplifications were performed using the iCycler (BIO-RAD). Reactions were performed in a mixture consisting of a 50 µL volume solution containing 1X SYBR Green supermix PCR buffer (BIO-RAD), (100mM KCL, 6 mM MgCl2, 40mM Tris-HCL, PH 8.4, 0.4mM of each dNTP [dATP, dCTP, dGTP and dTTP], iTaq DNA Polymerase 50 U/mL, SYBR Green I, 20mM Fluorescein) 300 nM of each primer, 0.25U/mL MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) and 0.4U/mL Rnase Inhibitor (Promega). The RT-PCR protocol starts with 30 min at 42°C for the RT. Prior to the PCR step iTaq DNA polymerase activation at 95 °C for 10 min was performed. Followed by 30 sec denaturation at 95 °C, 15 sec annealing at 57 °C, and 1.5 min elongation at 72 °C for 40 cycles. Fluorescence was detected at the end of every 72°C extension phase. To exclude the contamination of non-specific PCR products such as primer dimers, melting curve analysis was applied to all final PCR products after the cycling protocol.

Immunohistochemistry

IGF-II immunohistochemical analysis was performed using purified rabbit polyclonal anti-human IGF-II antibody. The IGF-II antibody was produced by immunizing one rabbit (Y819) with an IGF-II aa peptide (51–64, CYFSRPASRVSRRSR-amide) followed by affinity purification (YenZym antibodies, LLC); this antibody is able to recognize mature as well as precursor IGF-II and does not crossreact with IGF-I. Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin were detected by anti-survivin monoclonal antibody, anti-Bcl-2 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), and anti-Bcl-XL polyclonal antibody (BD Biosciences). 5µm tick paraffin block sections were de-waxed, rehydrated and treated with 1X antigen retrieval solution (Reveal, Biocare Medical). After endogenous peroxidase blocking (H2O2 3%), slides were incubated in corresponding primary antibodies (1:10) with blocking serum (mouse or rabbit ABC staining Systems, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C. The antibodies were revealed with the corresponding anti-mouse or anti-rabbit biotinylated antibodies for 30 min at room temperature, followed by streptavidin/peroxidase label (30 min at room temperature) using diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen as a substrate. The samples were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted. Tissue sections were washed with 1X PBS between each immunostaining step.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences between mean values were determined by using one-way ANOVA (for protein expression analysis between all groups), paired T test (for comparison between paired normal and tumor samples) and independent T test (for comparison between AA-CA samples) by using the SPSS 15.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). *Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM of three or more replicate experiments. A level of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

IGF-II siRNA effect on Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin in AA (CRL-2335, CRL-2329) and CA (Hs578t) breast cancer cell lines

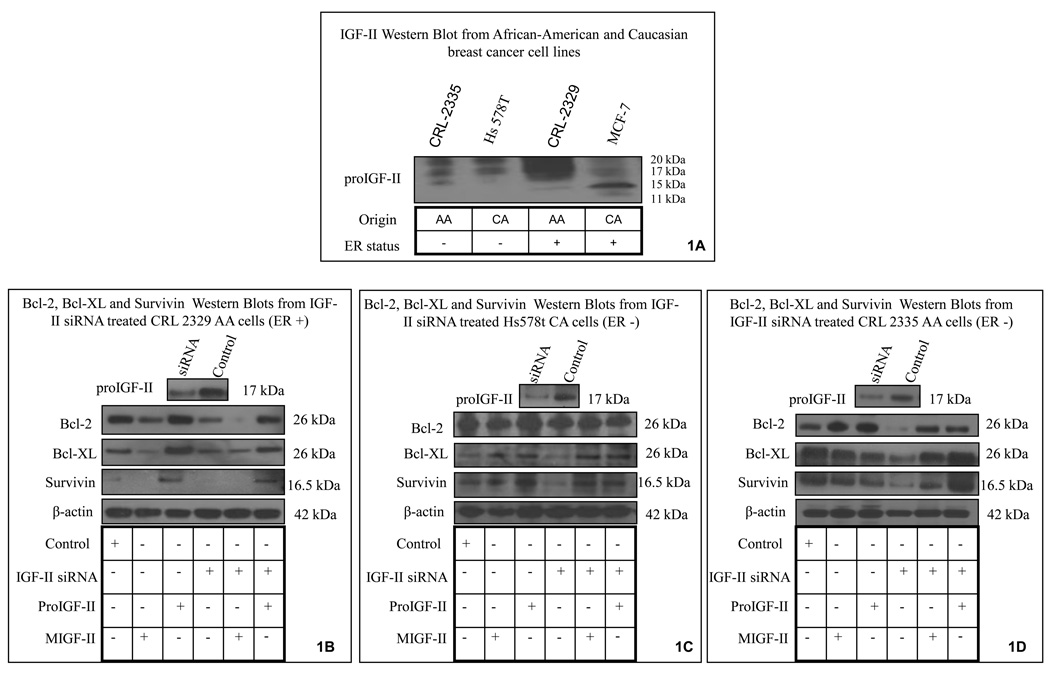

We started by analyzing IGF-II protein expression in breast cancer cell lines derived from AA and CA women. As seen on figure 1A, AA cell lines (CRL-2335 and CRL-2329) expressed higher levels of IGF-II protein than CA (MCF-7 and Hs587t) cell lines. The bands seen ranged from 11–17 kDa (due to differential glycosylation) and correspond to the precursor form of IGF-II (proIGF-II). Please note that although the IGF-II antibody used (Amano) recognizes both forms of IGF-II (mature and precursor), proIGF-II was the predominant form expressed. Figure 1B–D shows that transient transfection of IGF-II siRNA blocked 70% of IGF-II expression in all three cell lines used. Next, we proceeded to analyze IGF-II siRNA effect on Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin protein expression.

Figure 1.

IGF-II, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin protein expression in African-American and Caucasian breast cancer cell lines (CRL-2335, CRL-2329 and Hs578t) assessed by Western blot analysis. Figure 1A shows IGF-II Western blot in AA and CA breast cancer cells for comparison purposes. Although the monoclonal IGF-II antibody used (Amano) recognizes both forms (mature and precursor), proIGF-II was the predominant form expressed (11–17 kDa, according to glycosylation levels). Figures 1B–D shows IGF-II siRNA transfection effect on IGF-II levels for each cell line (top panel). Lower panels show Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin protein expression in IGF-II transfected cells and cells treated with either mature or proIGF-II. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Figure 1B shows representative Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin Western blots from CRL-2329 cells transfected with IGF-II siRNA, where these protein levels decreased by 60, 40 and 30% respectively. Addition of recombinant proIGF-II (100 ng/ml) to siRNA transfected cells had a significant effect on increasing Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin protein levels when compared to mIGF-II. Figure 1C shows Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin Western blots from Hs578t cells transfected with IGF-II siRNA where anti-apoptotic protein levels decreased by 30, 20 and 50% respectively. Addition of recombinant precursor and mature IGF-II to siRNA transfected cells had a significant effect on increasing Bcl-XL and survivin as compared to siRNA transfected cells. Transfection of CRL-2335 cells with IGF-II siRNA induced significant downregulation of all three anti-apoptotic proteins [(80, 70 and 80%) (Figure 1D)]. Addition of recombinant proIGF-II to siRNA transfected cells had a significant effect on increasing Bcl-XL and survivin proteins than recombinant mIGF-II.

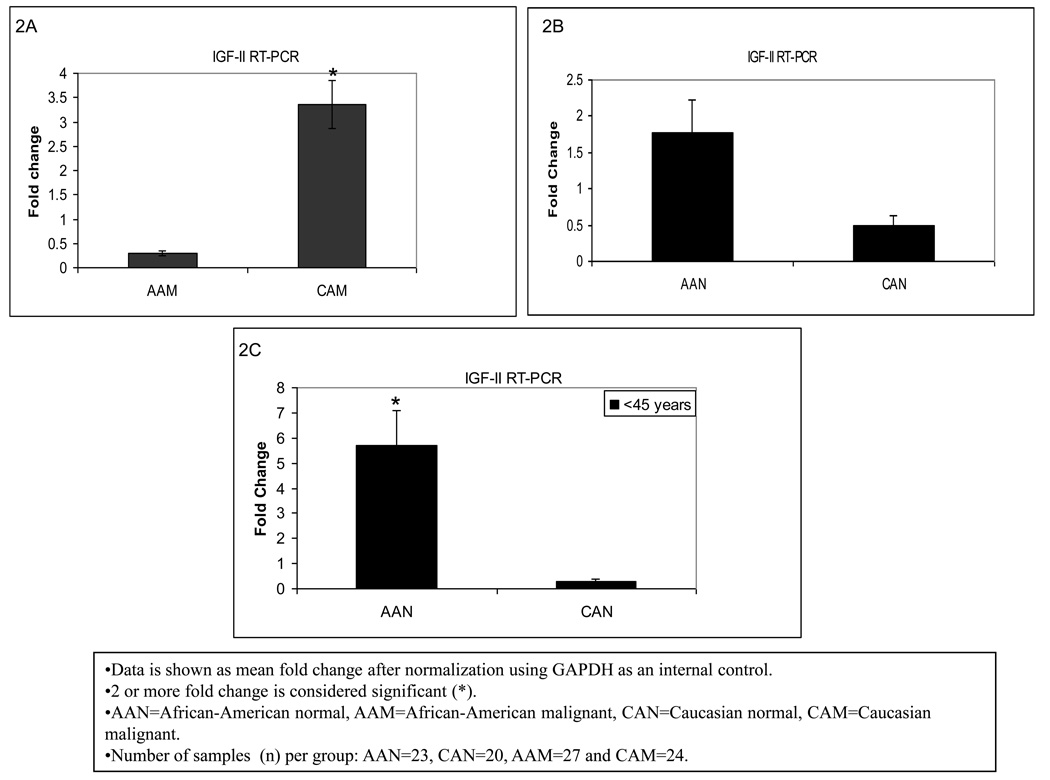

IGF-II mRNA expression in paired AA and CA breast cancer and normal tissue samples

Breast cancer mortality rates are higher among AA as compared to CA women for all ages. In this respect, we tested our hypothesis that IGF-II might contribute to this disparity, by analyzing IGF-II gene expression using Real Time-PCR in breast tumor and normal tissue samples from AA and CA women. Noteworthy, our results showed significantly higher levels of IGF-II mRNA (3 fold) in CA breast cancer tissue samples (CAM) as compared to AA tumor samples (AAM) (Figure 2A). Interestingly, in the present study normal samples from AA women (AAN) were found to express higher levels of IGF-II mRNA (1.8 fold) as compared to normal samples from CA women (CAN) as seen in figure 2B. Furthermore, since there is a slightly higher incidence of breast cancer in AA females 45 years or younger than in CA women, we compared IGF-II mRNA expression between AAN and CAN for this specific age group. As seen in figure 2C, normal tissues from AA women expressed significantly higher levels of IGF-II mRNA (5.5 fold) as compared to CA women for the same age group. No significant changes were observed in older women.

Figure 2.

IGF-II gene expression in African-American and Caucasian paired breast tissue samples assessed by Real Time-PCR (RT-PCR). Figure 2 (A–C) shows IGF-II gene expression represented as fold change after normalization using GAPDH as an internal control. Two (2) or more fold change was considered significant (*). Figure 2A shows IGF-II mRNA fold change between AAM and CAM for all samples. Figure 2B shows IGF-II mRNA comparison between AAN and CAN for all samples, while Figure 2C represents IGF-II mRNA fold change for AAN and CAN only in samples from women younger than 45 years of age.

AAN=African-American normal tissue, AAM=African-American malignant tissue, CAN=Caucasian normal tissue and CAM=Caucasian malignant tissue. Total number of patients (n) analyzed per group was as follows: AAN= 23, AAM=27, CAN=20 and CAM=24.

Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin mRNA expression in AA and CA breast tissue samples

CAN and CAM samples expressed higher levels of Bcl-2 mRNA than AAN and AAM respectively, although these changes did not reach statistical significance. Similarly Bcl-XL mRNA expression was not significantly different between the two ethnic groups. Noteworthy, Bcl-XL expression likewise IGF-II mRNA levels, was higher in AAN when compared to CAN in <45 years old women (data not shown).

Survivin, like IGF-II, is unique among other inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) because it is selectively expressed during development and in most human cancers but not in normal adult tissues. Re-expression of these proteins in cancer plays a significant role in apoptosis inhibition and tumor progression. Our study showed that AAM expressed higher levels of survivin mRNA than AAN, while this difference was much smaller for the CA samples (CAM as compared to CAN, data not shown).

IGF-II protein expression in AA and CA breast cancer tissues

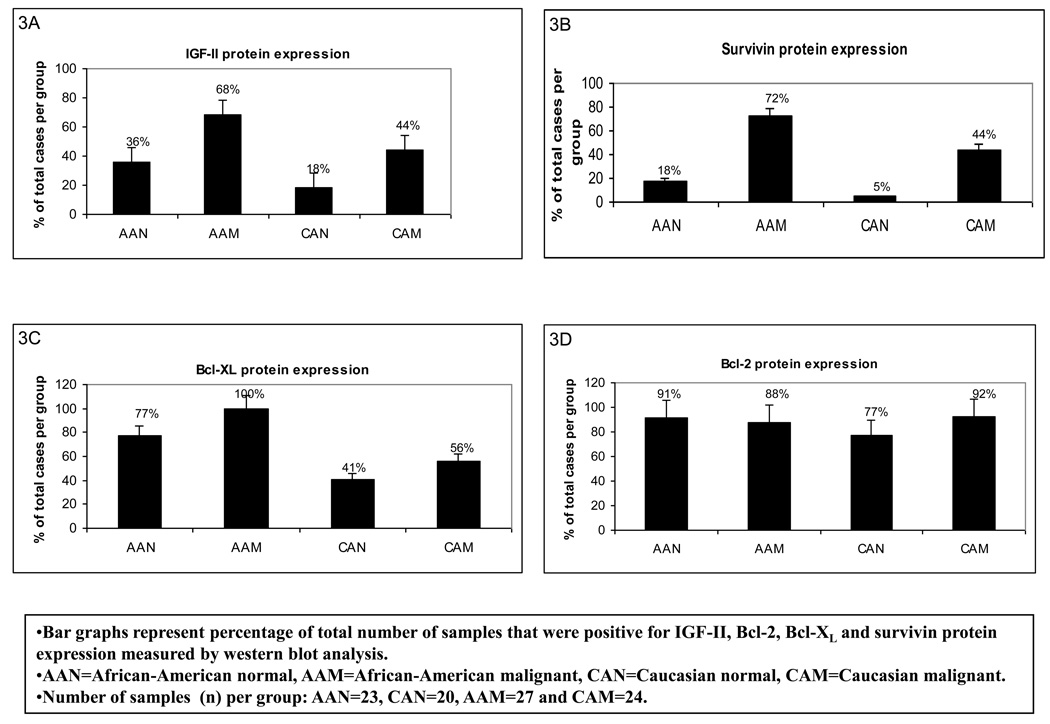

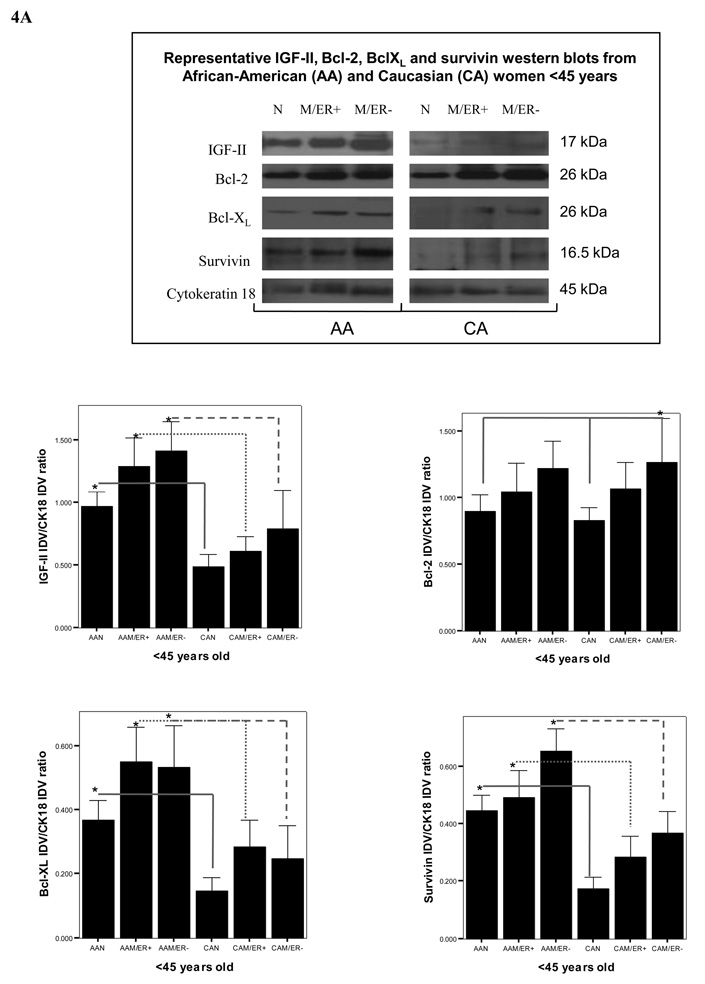

Protein translation is a key stage in the regulation of gene expression and cell growth. Changes in IGF-II production are likely to be executed at the post-transcriptional levels, so rapid adjustments can take place at crucial normal and tumor developmental stages. We used Western blot analysis to study the correlation between IGF-II mRNA and protein expression. As seen in figure 3A, our results show that a higher number of AA malignant samples (68%) expressed IGF-II protein when compared to CA malignant samples (44%), AAN (36%) and CAN (18%) samples. Furthermore, the precursor form of IGF-II (proIGF-II, 11–17 kDa) was the predominant form detected by Western blot, while the mature form (mIGF-II, 7.5 kDa) was only seen in 3 tumor samples (AAM). Since breast tissue samples constitute a heterogeneous population of cells (epithelial, adipocytes and stromal cells) we used the epithelial cell marker cytokeratin 18 to estimate IGF-II levels originating from epithelial cells by Western blot analysis. Tumors from AA women produced higher levels of IGF-II protein when compared to CA malignant samples at all age groups (figures 4A–B, top panels on Western blot data). The discrepancy observed between IGF-II mRNA (higher in CAM) and protein levels (higher in AAM) could be the result of differential IGF-II post-transcriptional regulation; In this regard, preliminary studies in our laboratory have shown increased levels of IGF-II mRNA binding proteins (IMPs) in AA tissue samples as compared to CAM samples. Of significance, normal tissues from AA women expressed significantly higher IGF-II levels when compared to normal tissue samples from CA women (figures 4A–B, top panels on Western blot data). Lower panels (figures 4A–B) show bar graphs of densitometry units on three separate experiments. Although ER (−) tumors from AA and CA tumor samples expressed more IGF-II protein than ER (+) tumors, no statistically significant difference was reached. Please note that although only one Western blot is depicted as a representative experiment, the bar graphs represent Western blot from all samples per each group (AAN, AAM, CAN and CAM). Higher IGF-II levels may translate into increased risk not only for fibrocystic changes, but also malignant transformation of normal mammary tissue contributing to the increase incidence of breast cancer seen in younger AA women, and the overall increased mortality rate in this ethnic group.

Figure 3.

Bar graph representation of percentage of total number of samples that were positive for IGF-II, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin protein expression from African-American (AA) and Caucasian (CA) paired breast tissue samples. Data was assessed by western blot analysis and presented as percentage of cases that showed positive bands for the corresponding proteins (panels A–D). Total number of patients (n) analyzed per group was as follows: AAN= 23, AAM=27, CAN=20 and CAM=24.

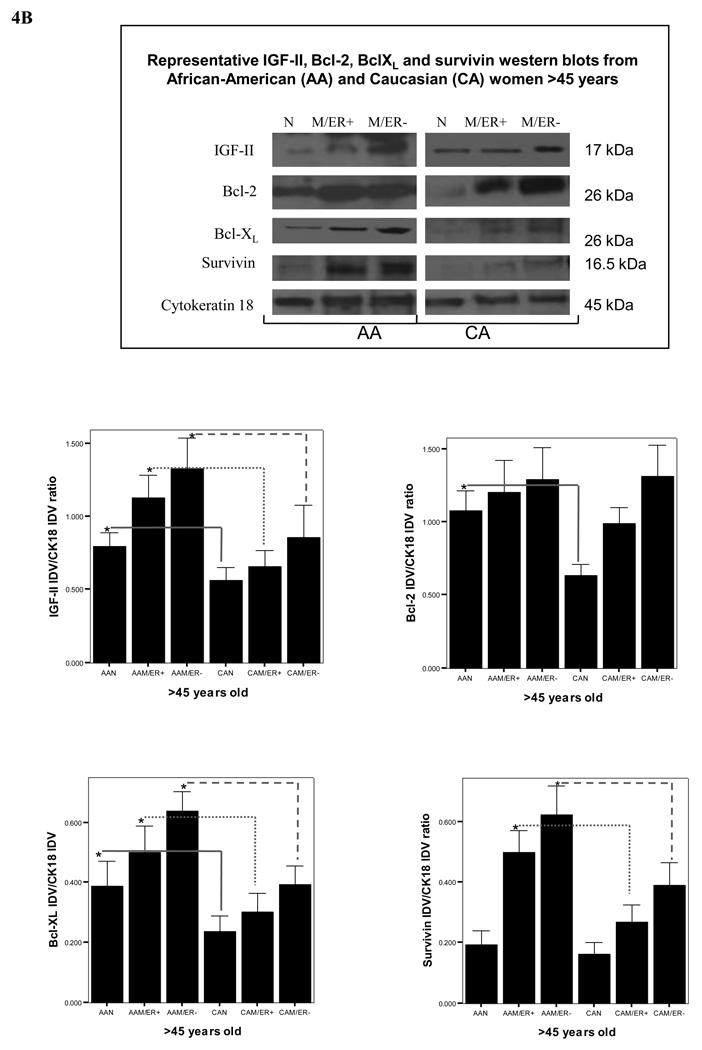

Figure 4.

Representative Western blot analyses of IGF-II, Bcl-XL, Bcl-2 and survivin in paired tissue samples from African-American (AA) and Caucasian (CA) women (<45 and >45 years of age, figures 4A and 4B respectively). The samples were separated into these two age groups based on the higher incidence of breast cancer in AA women younger than 45 years (but not after 45 years). Immunoreactive bands for IGF-II, Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, survivin and cytokeratin 18 were identified using ECL, scanned by densitometry and normalized to cytokeratin 18.The 17 kDa band represents pro-IGF-II and represents the main form of IGF-II produced by breast epithelial and malignant cells. Cytokeratin 18 was used as an epithelial cell marker (45 kDa). Lower panels (A–D) show bar graphs of IGF-II, Bcl-XL, Bcl-2 and survivin data normalized to cytokeratin 18 and presented as the mean ± SE of all samples per group. Asterisks indicate values statistically different (*p<0.05). Total number of patients (n) analyzed per group was as follows: AAN= 23, AAM=27, CAN=20 and CAM=24.

Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin protein expression in AA and CA breast cancer tissues

Since we have shown that these anti-apoptotic proteins are regulated by IGF-II “in vitro” in AA and CA breast cancer cell lines, we proceeded to examine if there was a correlation between IGF-II protein expression and Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin levels in AA and CA tissue samples. As expected, a higher number of tumor samples from AA women expressed survivin as compared to CA tumor samples (72% vs. 44% respectively) (Figures 3B). Of significance, higher number of normal AA tissue samples expressed survivin protein as compared to normal CA samples (18% vs. 5% respectively). Similarly, all malignant samples (100%) from AA women expressed Bcl-XL protein as compared to 56% of tumor samples from CA women (Figure 3C). No significant changes were detected among AA and CA in Bcl-2 protein expression (figure 3D).

As seen on figure 4A–B, semi-quantitative analysis of survivin, Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 protein levels (measured by Western blot analysis and using cytokeratin 18 as an epithelial cell marker) showed significant increase in survivin levels in AAM at all age groups [ER (+) and ER (−)] as compared to AAN tissues, while it was only significantly increased in CAM samples from women with ER (−) tumors only. Bcl-XL expression was higher in AAM as compared to AAN, CAM and CAN groups. Bcl-2 protein expression was significantly increased in CAM as compared to CAN, while no difference was seen between normal and tumor samples from AA women. Furthermore, Bcl-2 levels were higher in AAN as compared to CAN (>45 years).

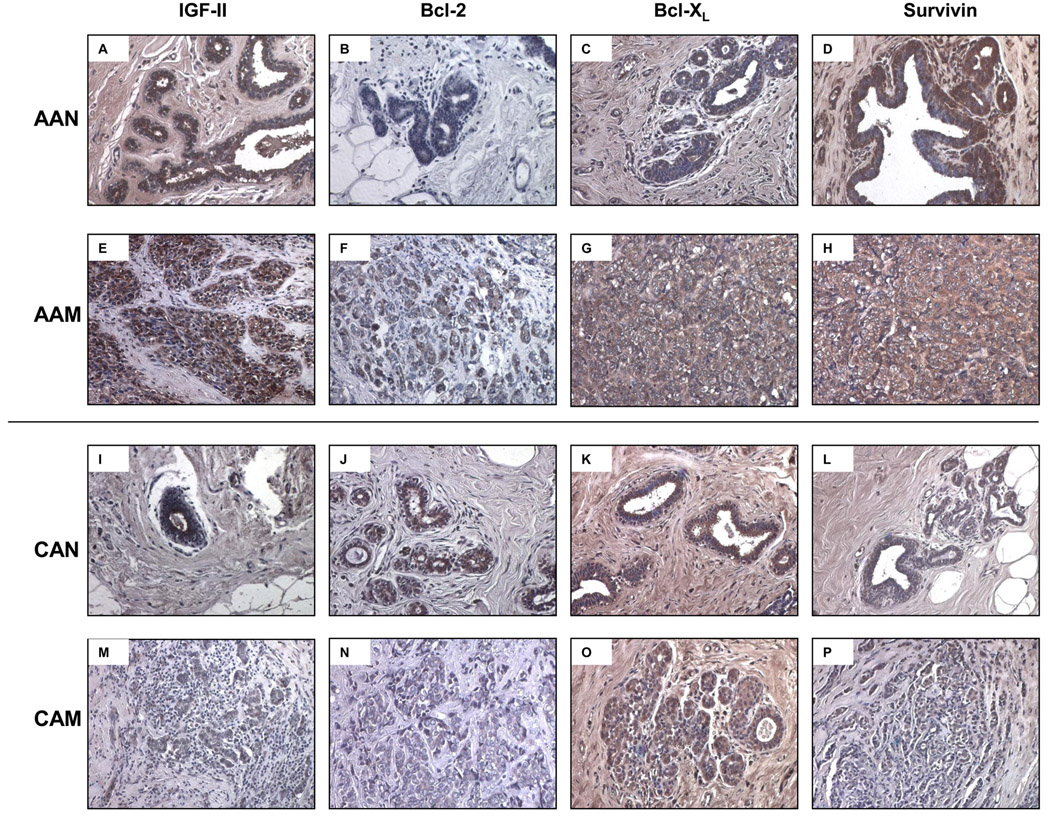

IGF-II, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin immunohistochemistry in AA and CA paired breast tissue samples

To further confirm IGF-II and the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin differential expression shown by Western blot analysis, we proceeded to assess their expression by immunohistochemistry. As seen on figure 6A normal tissue samples from AA women expressed higher levels of IGF-II as compared to their CA counterparts (figure 5I). Similarly Bcl-XL and survivin protein levels were higher in the tumor samples from AA women (figures 5 G–H) than in CA tumor samples (figures 5 O–P). Please note that both tumor samples (AA and CA) shown in the picture correspond to invasive ductal carcinomas (Bloom and Richardson’s grade III).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry of IGF-II, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin in human normal and malignant breast tissue samples. Malignant AA and CA samples correspond to ER (+) invasive ductal carcinomas (IDC) Bloom and Richardson’s grade III. Panels A–D and E–H corresponds to IGF-II, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin immunostaining, in AAN and AAM samples respectively. Panels I–L and M–P corresponds to IGF-II, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin immunostaining, in CAN and CAM samples respectively. Original magnifications 20× (insert represent a 40× section). Total number of patients (n) analyzed per group was as follows: AAN= 7, AAM=7, CAN=5 and CAM=5.

Discussion

Although all women are potentially at risk of developing breast cancer, differences in this heterogenous disease incidence and mortality rates among diverse ethnic populations suggest that multiple etiologic factors are at play. The role of genetics and the environment, cultural dynamics and sociodemographic differences across populations dictate the final outcome: a more or less aggressive type of the disease. Our present study addresses the need of a more comprehensive molecular approach to better understand health disparities in breast cancer, by investigating IGF-II expression and its regulation of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin in AA and CA breast cancer cell lines and by studying how it compares to IGF-II and the anti-apoptotic proteins expression in breast tissue samples from AA and CA women. IGF-II is a potent mitogen associated with increased cancer cell survival, proliferation [10], and an elevated risk of breast cancer recurrence [11]. We have previously demonstrated that IGF-II regulates the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin in the ER (+) MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, leading to inhibition of mitochondrial membrane depolarization, cell survival and chemoresistance [7, 8]. These findings prompted us to study the effects of IGF-II (mature and precursor forms), and IGF-II siRNA on the expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin in AA and CA breast cancer cells and analyzing how it compares to IGF-II and the anti-apoptotic proteins expression in breast tissue samples from AA and CA women. We demonstrated that overall proIGF-II had a more potent effect than mIGF-II in up-regulating these proteins following transient transfection with IGF-II siRNA, regardless of estrogen receptor (ER) status. We also found that survivin and Bcl-XL protein levels (like IGF-II), were significantly increased in AA tumors samples as compared to CA tumor samples. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in Bcl-2 levels. Survivin overexpression in breast tumors correlates with increased tumor grade, recurrence risk and decreased cancer patient survival [12], while Bcl-XL overexpression results in increased lymph node metastases due to higher resistance to apoptotic stimuli, increased cell survival and enhanced anchorage-independent growth [13]. In the present study, we first evaluated IGF-II expression between AA and CA breast cancer cell lines, which was shown to be increased in cells originating from AA women with breast carcinoma. Similarly, IGF-II protein expression was found to be higher in African-American (AA) tumor samples as compared to Caucasian (CA) tumors. Although a clear definition of different ethnic groups is controversial, the decreased incidence (except for women less than 45 years of age) and increased mortality rates in AA females have been mainly explained by factors such as low socioeconomic status and later stage at diagnosis, while factors contributing to distinct tumor biology remain poorly defined. Increased IGF-II levels are associated with cell proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis [5, 6]. Furthermore, in both AA cell lines [CRL-2329 (ER+) and -2335 (ER−)] and the CA cell line MCF-7 [7, 8] transfected with IGF-II siRNA, proIGF-II was more potent than mIGF-II in increasing Bcl-XL and survivin levels. This differential effect between pro- and mIGF-II was not observed in the ER (−) CA cell line Hs578t. The differential effect between proIGF-II and mIGF-II shown in this study is of great significance, due to the fact that both forms bind the IGF1R with the same affinity. Nevertheless, we have previously shown that proIGF-II induces increased Akt phosphorylation and an earlier and transient activation of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway leading to cell proliferation as compared to mIGF-II (which induced a prolonged Ras/MEK/ERK activation) and possibly growth arrest of MCF-7 cells [8]. Of note, the increased IGF-II expression seen in AA tissue samples correlates with increased BclXL and survivin expression, while CA tissue samples expressed lower levels of IGF-II and subsequently decreased levels of the antiapoptotic proteins were observed in all age groups, pointing towards an important IGF-II regulatory effect on antiapoptotic proteins “in vivo”. Survivin, a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAPs) family has the ability to suppress apoptosis initiated by both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways and participates in the regulation of cell division by controlling microtubule stability and mitotic spindle assembly [14]. In breast carcinomas, survivin levels correlate with high grade tumor and high proliferation rate, indicating that survivin has a role in cell proliferation as well as in apoptosis [15]. Survivin, like IGF-II, is strongly and diffusely expressed in embryonic and fetal organs and is overexpressed in a variety of tumors including breast carcinomas [15, 16]. Overall, increased survivin expression in cancer is an unfavorable prognostic marker that correlates with decreased survival, increased risk of recurrence, regional lymph node invasion and metastasis [16].

Bcl-XL over-expression has been correlated with increased nodal involvement and higher tumor grade in breast cancer patients [13, 17]. Metastasis, the most important cause of patient mortality from cancer, involves the ability of cancer cells to migrate from the primary tumor, survive in blood or lymphatic circulation and invade distant tissues. In this regard, Bcl-XL upregulation may be a potential marker of tumor progression since it correlates with poor patient survival and metastasis, in part, by mediating a phenotype in which redox pathways and glycolysis are coupled to protect breast cancer metastatic cells during transit to a distant tissue [17, 18].

Bcl-2, (a member of the Bcl family like Bcl-XL) is an anti-apoptotic protein expressed in a variety of embryonic and adult tissues. Its tumorigenic potential has been demonstrated in animal models and is supported by the finding of over-expression of Bcl-2 in a variety of tumors and lymphomas where Bcl-2 acts as an oncogene [19]. Conversely, in many solid organ tumors, including breast cancer, Bcl-2 expression is associated with favorable prognostic indicators such as low grade, estrogen receptor positivity and good outcome [20]. Bcl-2 also seems to differ substantially in the potency by which it inhibits apoptosis as compared to Bcl-XL in “in vitro” studies [21].

Previous studies have shown high pro-IGF-II protein levels (as compared to mIGF-II) in the epithelium of tumors originating from the breast, prostate and bladder [22]. Although IGF-II protein levels were higher in AAM and AAN tissue samples as compared to Caucasian samples, there was no correlation with IGF-II mRNA levels. Mu et al [11] showed a correlation between high tissue levels of IGF-II peptide and increased risk of recurrence, and a lack of correlation between IGF-II mRNA and protein levels in breast cancer tissues (CA tissue samples). The discrepancy observed between IGF-II mRNA and protein levels in AA as well as in CA breast tissue samples could be the result of differential IGF-II post-transcriptional regulation which includes, but is not limited to, specific promoter activation (P1-P4) leading to the production of mRNAs with different translational capabilities [23]. Moreover, altered production of IGF-II mRNA binding proteins (IMP-1 and IMP-3) also modulate IGF-II mRNA stability, localization and translation rate of the IGF-II mRNAs [23, 24]. Noteworthy, IGF-II levels from normal AA tissue samples were significantly higher than in their CA counterparts. Higher IGF-II levels expressed may be responsible for the increased risk of malignant transformation found in younger AA women (<45 years) [25].

Of great significance is the possible link between proIGF-II in diabetes and cancer observed among AA breast cancer patients. It has also been shown that overexpression of IGF-II may lead to type 2 diabetes in a transgenic mouse model, through a direct effect of IGF-II on β-cell proliferation through activation of the IGF-IR, insulin receptor and/or hybrid receptors (26). Transgenic mice overexpressing IGF-II in β-cells were hyperinsulinemic early in life and showed altered glucose and insulin tolerance tests, and developed insulin resistance. Interestingly, adult rodents express very low levels of IGF-II, whereas high levels of serum IGF-II persist in humans [26]. Thus, elevated IGF-II protein levels in normal AA women as compared with normal CA women may not only increase the risk for breast cancer, but may also contribute to the development of insulin resistance and diabetes in this ethnic group. Furthermore, type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, which are more common in AA women, have been associated with increased breast cancer risk [27]. In addition, proIGF-II is the critical form that regulates insulin secretion, since it is the IGF-II E-peptide (preptin) that stimulates insulin secretion (28). Of note, this is the same IGF-II form detected at higher levels in cells and tissues from AA patients.

In summary, our study provides evidence that demonstrates that increased IGF-II expression is associated with increased protein levels of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and survivin. This constitutes an exciting observation because it indicates that IGF-II could regulate these proteins “in vivo”. Since these proteins increase tumor growth, promote metastasis and inhibit cell death, they represent a powerful target to address the breast cancer health disparity observed among AA breast cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by 5P20 MD001632, and NIGMS 5R25GM060507

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute, DC-CPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program (SEER) SEER Stat Database: Mortality-All COD, Public-Use with State, Total U.S. for Expanded Races/Hispanics (1991–2001) 2004 April; Released http://www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 2.Morrione A, Valentinis B, Xu S-Q, Yumet G, Louvi A, Efstratiadis A, Baserga R. Insulin-like growth factor II stimulates cell proliferation through the insulin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1997;94:3777–3782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sciacca L, Constantino A, Pandini G, Mineo R, Frasca F, Scalia P, Sbraccia P, Goldfine ID, Vigneri R, Belfiore A. Insulin receptor activation by IGF-II in breast cancers: evidence for a new autocrine/paracrine mechanism. Oncogene. 1999;18:2471–2479. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pravtcheva DD, Wise TL. Metastazing mammary carcinomas in H19 enhancers-Igf2 transgenic mice. The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1998;281:43–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perdue JF, LeBon TR, Kato J, Hampton B, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y. Binding specificities and transducing function of the different molecular weight forms of IGF-II on IGF-IR. Endocrinology. 1991;129:3101–3108. doi: 10.1210/endo-129-6-3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De León DD, Wilson DM, Powers M, Rosenfeld RG. Effects of insulin-like growth factors and IGF receptor antibody on the proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Growth Factors. 1992;6:327–336. doi: 10.3109/08977199209021544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalla Singh S, Moretta D, Almaguel F, Wall NR, De León M, De León D. Differential effect of proIGF-II and IGF-II on resveratrol induced cell death by regulating survivin cellular localization and mitochondrial depolarization in breast cancer cells. Growth Factors. 2007;25:363–372. doi: 10.1080/08977190801886905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalla Singh S, Moretta D, Almaguel F, De León M, De León D. Precursor IGF-II and mature IGF-II induce Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL expression through different signaling pathways in breast cancer cells. Growth Factors. 2008;26:92–103. doi: 10.1080/08977190802057258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco-Aparicio C, Pequeño B, Moneo V, Romero L, Leal JF, Velazco J, Fominaya J, Carnero A. Inhibition of PI3K synergizes with gemcitabine in low-passage tumor cell lines correlating with Bax translocation to the mitochondria. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2005;16:977–987. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000180117.93535.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vyas S, Asmerom Y, De León DD. Resveratrol regulates IGF-II in breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4224–4233. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mu L, Katsaros D, Wiley A, Lu L, Rigault IR, Smith S, Khubchandani S, Sochirca O, Arisio R, Yu H. Peptide concentrations and mRNA expression of IGF-I, IGF-II and IGFBP-3 in breast cancer and their associations with disease characteristics. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:151–162. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croci DO, Cogno IS, Vittar NB, Salvatierra E, Trajtenberg F, Podhajeer OL, Osinaga E, Rabinovich GA, Rivorola VA. Silencing survivin gene expression promotes apoptosis of human breast cancer cells through a caspase-independent pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 2008;105:381–390. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.España L, Fernandez Y, rubio N, Torregrosa A, Blanco J, Sierra A. Overexpression of Bcl-XL in human breast cancer cells enhances organ-selective lymph node metastasis. Breast Cancer Res and Treat. 2004;87:33–44. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000041579.51902.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giodini A, Kallio MJ, Wall NR, Gorbsky GJ, Tognin S, Marchisio PC, Symons M, Altieri DC. Regulation of microtubule stability and mitotic progression by survivin. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2462–2467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hinnis AR, Luckett JC, Walker RA. Survivin is an independent predictor of short-term survival in poor prognostic breast cancer patients. British Journal of Cancer. 2007;96:639–645. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka K, Iwamoto S, Gon G, Nohara T, Iwamoto M, Tanigawa N. Expression of survivin and its relationship to loss of apoptosis in breast carcinomas. Clinical Cancer Research. 2000;6:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olopade OI, Adeyanju MO, Safa AR. Overexpression of Bcl-X protein in primary breast cancer is associated with high tumor grade and nodal metastases. Cancer J Sci Am. 1997;3:230–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.España L, Martín B, Aragüés R, Chiva C, Oliva B, Andreu D, Sierra A. Bcl-XL mediated changes in metabolic pathways of breast cancer cells. American Journal of Pathology. 2005;167:1125–1137. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pietenpol JA, Papadopoulos N, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Paradoxical inhibition of solid tumor cell growth by Bcl-2. Cancer Research. 1994;54:3714–3717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callagy GM, Pharoah PD, Pinder SE, Hsu FD, Nielsen TO, Ragaz J, Ellis IO, Huntsman D, Caldas C. Bcl-2 is a prognostic marker in breast cancer independently of the Nottingham prognostic index. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12:2468–2475. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fiebig AA, Zhu W, Hollerbach C, Leber B, Andrews DW. Bcl-XL is qualitatively different from and ten times more effective than Bcl-2 when expressed in a breast cancer cell line. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:213–217. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li SL, Goko H, Xu ZD, Kimura G, Sun Y, Kawachi MH, Wilson TG, Wilczynski S, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y. Expression of insulin like growth factor (IGF)-II in human prostate, breast, bladder and paraganglioma tumors. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;291:469–479. doi: 10.1007/s004410051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen SK, Christiansen J, Hansen T, Larsen MR, Nielsen FC. Human insulin-like growth factor II leader 2 mediates internal initiation of translation. Biochem J. 2002;363:37–44. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vikesaa J, Hansen J, Jonson L, Borup R, Wewer UM, Christiansen J, Nielsen FC. RNA-binding IMPs promote cell adhesion and invadopodia formation. The EMBO Journal. 2006;25:1456–1468. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Lingle WL, Degnim AC, Ghosh K, Vierkant RA, Maloney SD, Pankratz VS, Hillman DW, Suman VJ, Johnson J, Blake C, Tlsty T, Vachom CM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Visscher DW. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devedjian J-C, George M, Casellas A, Pujol A, Visa J, Pelegrin M, Gros L, Bosch F. Transgenic mice overexpressing insulin-like growth factor II in β cells develop type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;105:731–740. doi: 10.1172/JCI5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose DP, Haffner SM, Baillargeon J. Adiposity, the metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer in African-American and White American women. Endocrine Reviews. 2007;28:763–777. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchanan CM, Phillips AR, Cooper GJ. Preptin derived from proinsulin-like growth factor II (proIGF-II) is secreted from pancreatic islet β-cells and enhances insulin secretion. Biochem J. 2001;360:431–439. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3600431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.