Abstract

Sensory feedback from muscles and peripheral sensors acts to initiate, tune or reshape motor activity according to the state of the body. Yet, sensory neurons often show low levels of activity even in the absence of sensory input. Here we examine the functional role of spontaneous low-frequency activity of such a sensory neuron. The anterior gastric receptor (AGR) is a muscle tendon organ in the crab stomatogastric nervous system whose phasic activity shapes the well-characterized gastric mill (chewing) and pyloric (filtering) motor rhythms. Phasic activity is driven by a spike initiation zone near the innervated muscle. We here demonstrate that AGR possesses a second spike initiation zone, which is located spatially distant from the innervated muscle in a central section of the axon. This initiation zone generates tonic activity and is responsible for the spontaneous activity of AGR in vivo, but does not code sensory information. Rather, it is sensitive to the neuromodulator octopamine. A computational model indicates that the activity at this initiation zone is not caused by excitatory input from another neuron, but generated intrinsically. This tonic activity is functionally relevant, because it modifies the activity state of the gastric mill motor circuit and changes the pyloric rhythm. The sensory function of AGR is not impaired since phasic activity suppresses spiking at the central initiation zone. Our results thus demonstrate that sensory neurons are not mere reporters of sensory signals. Neuromodulators can elicit non-sensory coding activity in these neurons that shapes the state of the motor system.

Keywords: sensory neuron, sensory-motor-integration, stomatogastric nervous system, central pattern generation, spontaneous activity

Introduction

It is generally assumed that the spike activity of sensory neurons codes information about the sensory modality it provides to the central nervous system (CNS). This view presumes that spike initiation occurs close to the innervated sensory structure and codes the sensory signal. Many sensory neurons, however, are spontaneously active even without sensory input. Such baseline activity counters the idea of a sensory neuron as a simple reporter of the sensory signal. We examine the role of spontaneous activity generated by a spike initiation zone of a sensory neuron that is distinct from its sensory dendritic structure. In particular, we explore the hypothesis that tonic activity of a sensory neuron can shape the activity state of a motor network and thus changes the motor response to inputs from other sensory pathways.

Sensory feedback from the muscles and periphery acts to initiate, tune or reshape the motor activity according to the state of the periphery. The anterior gastric receptor (AGR) is a muscle tendon organ in the stomatogastric nervous system (STNS; Fig. 1A) whose activity times the output of the gastric mill central pattern generator (Simmers & Moulins, 1988a; 1988b; Smarandache & Stein, 2007). AGR participates in a long-loop reflex pathway; that is, all of its effects appear to be mediated indirectly via projection neurons in the commissural ganglia (Combes Simmers & Moulins, 1988a; Combes et al., 1995; Combes et al., 1999). Due to the rhythmic movements of the gastric mill muscles, AGR activity is usually patterned in time with the gastric mill rhythm. However, AGR is also often tonically active, both in the acutely isolated STNS preparation and in vivo. We are interested in the generation and function of this tonic activity.

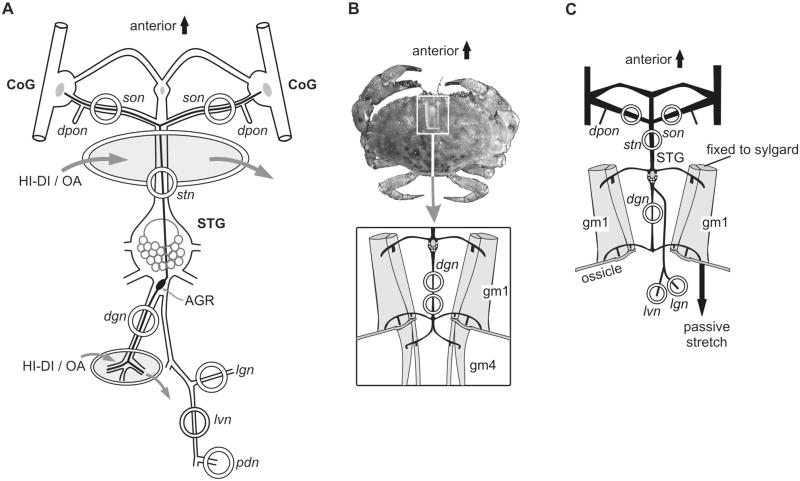

Figure 1.

Experimental setup. A Schematic, isolated STNS preparation of the stomatogastric nervous system. The soma of the anterior gastric receptor (AGR) is located in the stomatogastric ganglion (STG). AGR is a bipolar neuron which projects one axon through the dorsal gastric nerve (dgn) and another through the stomatogastric (stn) and superior oesophageal nerves (sons). Action potentials were recorded extracellularly at the indicated regions (open circles) of the sons, stn, dgn, lvn (lateral ventricular nerve), pdn (pyloric dilator nerve) and lgn (lateral gastric nerve). In some experiments, the stn or the dgn was selectively superfused with high divalent (HI-DI) saline or octopamine (OA) as indicated in the shaded region. Gastric mill rhythms were elicited by stimulating the dpon (dorsal posterior oesophageal nerve). B Top: dorsal view of Cancer pagurus. The carapace was opened for in vivo dgn recording. Bottom: schematic drawing of nerve and muscle positions as seen through the opening in the carapace. The position of the extracellular dgn recordings is indicated (open circles). gm1, gastric mill muscle 1 (protractor muscle). gm4, gastric mill muscle 4 (retractor muscle). C. Neuromuscular preparation. The STNS was isolated, but the gm1 muscles were left intact and transferred along with the innervating nerves to the Petri dish. The anterior muscle apodemes were immobilized by pinning them to the Sylgard. We either recorded during isometric muscle contractions or during passive muscle stretch.

Neurons often possess a complex anatomical morphology that can lead to local signal processing within the cell structure. A functional compartmentalization of the dendritic structure, for example, can be manifested in multiple spike initiation zones (Yuste & Tank, 1996; Antic et al., 2000; Golding et al., 2002; Oesch et al., 2005; Holthoff et al., 2006), which are considered to be important in synaptic integration and amplification. Multiple spike initiation zones are also found in axons, for example in leech heart interneurons whose axons span multiple ganglia and can generate spikes in these ganglia (Kristan et al., 2005). Additional spike initiation zones in the axon can also be subject to neuromodulation and overwrite the centrally-generated activity (Meyrand et al., 1992; Bucher et al., 2003; Goaillard et al., 2004; Le et al., 2006).

We demonstrate that the sensory neuron AGR possesses two spike initiation zones, one of which is spatially distant from the innervated muscle and located in a central section of the axon. This initiation zone is sensitive to the neuromodulator octopamine and generates tonic activity that is responsible for the spontaneous tonic activity of the sensory neuron in vivo. The AGR tonic activity is functionally relevant and alters the state of the motor circuits, emphasizing the importance of functional compartmentalization in sensory neurons in shaping motor output.

Materials and Methods

Animals and preparation

Adult crabs, Cancer pagurus, were purchased from commercial sources (Feinfisch GmbH, Neu-Ulm, Germany). Animals were kept in filtered aerated artificial seawater (10–12 °C). Animals were anesthetized by packing them on ice for 30–40 min. Experiments were performed on the isolated STNS preparation (Fig. 1A; in vitro), the intact animal (Fig. 1B; in vivo) or in a neuromuscular preparation (Fig. 1C). Dissections were carried out as previously described in Guitierrez & Grashow (2009; in vitro preparation) and Smarandache et al. (2008) (in vivo preparation). Experiments were carried out in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 24th November 1986 (86/609/EEC) and with the Guidelines laid down by the US National Institutes of Health regarding the care and use of animals for experimental procedures.

Solutions

During all recordings in the petri-dish, preparations were superfused continuously with chilled (10–13 °C) C. pagurus saline. Saline had the following compositions [mM*l−1]: NaCl, 440; MgCl2, 26; CaCl2, 13; KCl, 11; trisma base, 10; maleic acid, 5; pH 7.4–7.6. In some experiments, the stomatogastric nerve (stn, Fig, 1A) was superfused with octopamine (Sigma) containing saline or high divalent saline (HI-DI) in [mM/l]: NaCl, 439; MgCl2, 130; CaCl2, 64.5; KCl, 11; trisma base, 11.2; maleic acid, 5; pH 7.4–7.6). Alternatively, solutions were applied to the stn with a 5 ml syringe. The octopamine concentration was 10−5 M unless stated otherwise.

Dissection and electrophysiology

In vitro preparation

The isolated STNS preparation (Fig. 1A) was pinned down in a silicone elastomer-lined (ELASTOSIL RT-601, Wacker, Munich, Germany) petri dish and continuously superfused (7–12 ml/min) with physiological saline (10–13 °C). Standard techniques were used for extracellular and intracellular recordings (for details see Stein et al. (2005). Petroleum jelly-based cylindrical compartments were used to electrically isolate nerve sections from the bath. One of two stainless steel electrodes was placed inside the compartment to record the activity on the nerve. The other wire was placed in the bath as reference electrode. Extracellular signals were recorded, filtered and amplified through an amplifier from AM Systems (Model 1700, Carlsborg, WA, USA). To facilitate intracellular recordings, we desheathed the stomatogastric ganglion (STG) and visualized it with white light transmitted through a darkfield condenser (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Sharp microelectrodes (15–25 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing 0.6 M K2SO4 and 0.02 M KCl. Intracellular current injections were accomplished using NPI NEC 10L amplifier (NPI Electronic GmbH, Tamm, Germany) in bridge mode. STG neurons were identified by their activity patterns, synaptic interactions and axonal projection pathways in combination with current injections, as described previously (Weimann et al., 1991; Bartos & Nusbaum, 1997; Blitz & Nusbaum, 1997). The gastric mill rhythm was monitored by the activity of the lateral gastric neuron (LG, 1 cell), the dorsal gastric neuron (DG, 1 cell) and the gastric mill motor neurons (GMs, 4 cells). This rhythm was considered spontaneously active when LG, a member of the gastric mill central pattern generator, produced bursts of action potentials. The gastric mill cycle period was defined as the duration between the onset of an impulse burst in LG and the onset of the subsequent LG burst. LG activity was monitored either via intracellular recordings from its soma in the STG or via extracellular recordings from the lateral gastric nerve (lgn). DG activity was recorded extracellularly from the dorsal gastric nerve (dgn). Gastric mill rhythms were elicited via extracellular stimulation of the paired dorsal posterior oesophageal nerves (dpon stimulation; Beenhakker et al., 2004) with 10 stimulus trains of 6 s duration (20 Hz stimulation frequency) and 4 s inter-train intervals. Dpon stimulation reliably elicits a gastric mill rhythm which involved antiphase bursting activity of the protractor and retractor motor neurons. The rhythm outlasted the stimulus for at least 10 minutes. All measurements were taken after the end of the dpon stimulation and, therefore, included no artifacts.

The pyloric rhythm was monitored by measuring the activities of the lateral pyloric, pyloric constrictor, ventricular dilator, inferior cardiac and pyloric dilator (PD) neurons. Activities were measured on the lateral ventricular nerve (lvn) and the pyloric dilator nerve (pdn; Fig. 1A). The period of the rhythm was determined by the time between two consecutive bursts of the two PD neurons. For these neurons, the total number of spikes was determined from the pdn recording.

AGR was either recorded intracellularly from its soma in the STG or extracellularly, or both. AGR action potentials could be monitored on the stomatogastric nerve (stn), the paired superior oesophageal nerves (sons) and the dgn (Smarandache & Stein, 2007). Multi-sweep recordings were used to detect AGR spikes and to determine the initiation zone at which spikes were generated.

Activity was measured as the number of action potentials per burst, the mean intraburst spike frequency, burst duration, duty cycle or, in the case of tonic firing, as instantaneous frequency or average firing frequency of an arbitrarily chosen section of the recording (duration ranged from 20 to 130 s). Mean values for all gastric mill-related parameters as well as those for the pyloric rhythm were determined from measurements of at least 8 consecutive cycles of rhythmic activity.

Neuromuscular preparation (Fig. 1C)

For these experiments, the STNS was isolated, but the gm1 muscles were left intact and transferred along with the innervating nerves to the petri dish. The stomach wall underneath the muscles was removed. We stretched the gm1 muscles such that total muscle length corresponded to the resting length measured beforehand during dissection of the animal. We then immobilized the anterior muscle apodemes, which connect the muscles to the carapace, and the posterior ossicles. In this experimental setup it was possible to record AGR and motor neuron activities with extracellular recordings. In addition, isometric muscle contractions could be elicited by activating the gastric mill rhythm with dpon stimulation (see above).

In vivo preparation (Fig. 1B; see also Stein et al., 2006)

The dorsal carapace and the hypodermis above the STNS and the stomach muscles were opened. Custom-made extracellular hook electrodes were attached to the dgn and fixed with a holder to the remaining carapace. DG and AGR activities were monitored from recordings of the dgn. All dissections were done in physiological saline at ~4°C. After implanting the electrodes, the carapace was sealed with a plastic cover and dental cement (Protemp II, ESPE AG, Seefeld, Germany) and the animals were placed back in the tank. Only measurements recorded from animals that survived more than two days were used.

Data analysis

Data were recorded onto computer hard disk using Spike2 (ver. 6.02–6.06; CED, Cambridge, UK) and a micro 1401 board (CED). Data were analyzed using Spike2 script language. Individual scripts are available at http://www.neurobiologie.de/spike2. Final figures were prepared with CorelDraw (version 12 for Windows). Graphics and statistics were generated using Excel (Microsoft) or Origin (version 7.0237; Northampton, MA, USA). Normally distributed data were tested with a non-directional paired t-test or a One-Way-ANOVA (Holm-Sidak-method). Other data were additionally tested with Friedman RM ANOVA on Ranks, non-directional Wilcoxon signed rank test or One-way-ANOVA for repeated measures on Ranks using Turkey Test. Data are either presented as mean ± SD or as box plots containing median, minimum and maximum, upper and lower quartiles and mean. N refers to the number of animals, while n gives the number of trials or consecutive cycles measured. For all statistical tests, significance with respect to control is indicated on the figures using the following symbols: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Computational model

To investigate whether action potentials generated at the anterior spike initiation zone of AGR can interfere with those generated at the posterior initiation zone during muscle contractions, we built a computational model of a single long axon and initiated spikes at the two ends of the model axon. To enable the model axon to generate both low- and high-frequency activity, we based this model on the Connor and Stevens model neuron (Connor & Stevens, 1971; Dayan et al., 2001). The model axon had a diameter of 5 μm and length of 20 mm with specific axial resistance Ra = 200 Ω · cm, specific membrane resistance Rm = 3333 Ω · cm2, and specific membrane capacitance Cm = 1 μm/cm2. The model axon had a length constant of λ = 0.456 mm and membrane time constant τm = 3.33 ms. For numerical simulations, the model was compartmentalized to compartments of 0.1 λ length. Simulations were run with a time step of 10 μs with a fourth order Runge-Kutta numerical scheme using the software Network (http://stg.rutgers.edu/software/network.htm).

The model included three voltage-gated ionic currents, INa, IKd and IA and the voltage in each compartment obeyed the current balance equation:

where each voltage-gated ionic current (vgic = Na, Kd or A) was modeled as a Hodgkin-Huxley type current:

with activation kinetics m and (for vgic = Na and A) inactivation kinetics h. The activation and inactivation variables obeyed the equation:

where x=m or h. The maximal conductances of the voltage-gated currents were calculated from the specific conductances (in S·cm2): GNa = 1.2×108, GKd = 1.7×107 and GA = 3.2×107, according to the surface area of the compartment. The ionic reversal potentials were (in mV): Eleak = −17, ENa = 55, EKd = EA = −77.5. Additional model equations were as follows:

With these equations, the model axon was capable of producing action potentials in a frequency range of 0.1–100 Hz.

Action potentials were generated at either end of the model axon using two different protocols. In protocol 1, a DC depolarizing current was injected to produce a constant spike rate. The results obtained with this protocol were equivalent when compared to those obtained by adding a constant conductance with a reversal potential at 0 mV, equivalent to a modulatory excitation (data not shown). In protocol 2, action potentials were generated with a brief depolarizing pulse of 2 nA amplitude and 2 ms duration applied at a constant frequency. The results obtained with this protocol were equivalent to those obtained when a fast excitatory input from a presynaptic neuron was applied to the end of the axon (data not shown).

Results

AGR shows tonic activity in vivo and in vitro

The sensory neuron AGR has been characterized as a muscle tendon organ (Combes et al., 1995; Smarandache & Stein, 2007) because it innervates tendon-like structures of the bilaterally symmetric gastric mill muscles gm1 and encodes the tension of these muscles in its firing frequency. In the isolated STNS preparation, AGR is always spontaneously active and shows tonic firing with low firing frequencies. In the crab Cancer pagurus, this tonic activity seems to originate from a spike initiation zone located anterior to the AGR soma (Fig. 1A) and thus spatially distant from the innervated muscles (Smarandache & Stein, 2007). Here, we study the functional impact of this tonic AGR activity on the gastric mill central pattern generator (CPG) in the stomatogastric ganglion. For this purpose, we first characterized the range of available AGR firing frequencies, the origin of the action potentials and the effects of changes in firing frequency on the motor pattern. We compared data from intact animals, neuromuscular preparations and isolated STNS preparations.

(1) Intact animals

Previous studies have shown that AGR projects through the dorsal gastric nerve (dgn) and that its soma is located in the STG. AGR activity can readily be recorded and identified on the dgn with permanently implanted hook electrodes (Smarandache et al., 2008). The dgn also contains the axons of the gastric mill motor neurons (GMs) and of the dorsal gastric neuron (DG). In these recordings, AGR usually showed low-frequency tonic firing (Fig. 2A; f = 3.66 ± 2.2 Hz; N = 17) which showed variability across animals (Fig. 2B; f range 0.7 to 9.4 Hz).

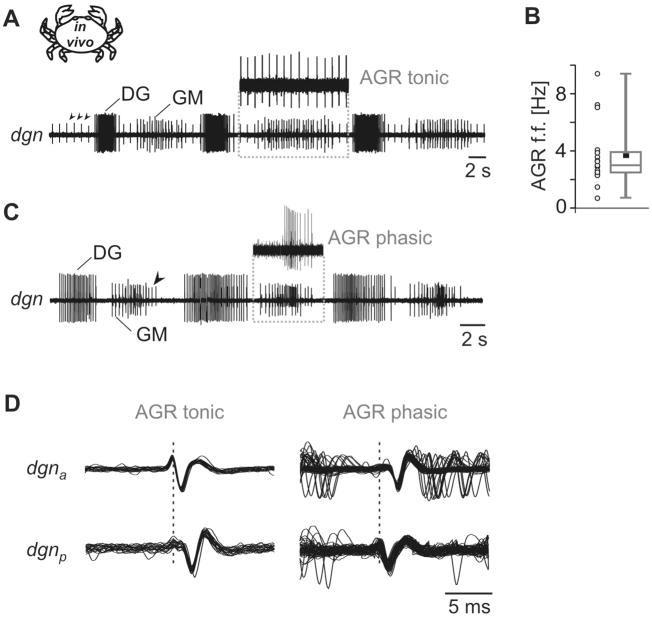

Figure 2.

In vivo recordings indicate that tonic and phasic AGR activity originates from different spike initiation zones. A. Extracellular recording of dgn in vivo during a gastric mill rhythm. In this example AGR showed tonic activity. Arrowheads point at AGR action potentials. Inset: AGR action potentials were extracted from the recording to demonstrate its tonic activity. B. Variability of spontaneous AGR activity in vivo. Plot of average tonic AGR firing frequency and boxplot summarizing 17 preparations. Number of trials per animal 55 < n < 424. C. Same animal as in panel A during a different gastric mill rhythm. Here, AGR was phasically active during the burst of the GM neurons. Inset: Phasic AGR activity. D. Multisweep recordings of two extracellular dgn recordings in vivo. dgnp, posterior recording; dgna, anterior recording (see also Fig. 1B). Left: spikes traveled in posterior direction (n = 20 sweeps). Right: spikes traveled in anterior direction (n = 60 sweeps). Schematic inset in A indicates in vivo recording.

During gastric mill rhythmic activity, AGR continued to fire tonically in some cases (Fig. 2C) whereas its activity became phasic during others (Fig. 2C). AGR phasic activity was phase-locked to that of the motor neurons. Whenever tonic activity ceased and phasic firing began, the AGR spike shape was clearly altered. To explain the difference in spike shape, we attached a second hook electrode to the dgn (N = 7). We found that in all these recordings the tonically generated AGR spikes were traveling from the STG towards the muscles and were thus efferent (Fig. 2D, left). By contrast, when AGR was phasically active, spikes were afferent and traveled from the muscles towards the STG (Fig. 2D, right). This indicated that AGR generated two types of action potentials and that the direction of spike conduction changed whenever AGR was phasically activated, as was previously suggested (Smarandache & Stein, 2007).

(2) Neuromuscular preparations

One of the disadvantages of recording from intact animals is the limited number of recording probes. As a consequence, we were not able to determine where the AGR spikes are generated, through which nerves they propagate, what their targets are and if they interact. For example, it is known that all AGR actions on the STG motor patterns are mediated indirectly via neurons located in the commissural ganglia (CoGs; Smarandache & Stein, 2007). In intact animals, however, we could not test whether AGR action potentials generated at the central spike initiation zone invaded the CoGs, or if they were even generated in these ganglia. We thus devised a neuromuscular preparation (see Fig. 1C and Material and methods) with the paired protractor muscles gm1 and their innervations left intact. AGR spikes were traced on the dgn, the stn and the sons. In all 27 preparations, AGR was tonically active spontaneously (Fig. 3A, left; f = 4.57 ± 1.26 Hz; N = 27). While in eight experiments spikes originated in the periphery, in 19 experiments they were generated at a spike initiation zone that was located in the anterior section of AGR and thus spatially distant from the innervated muscle. Here, spikes first appeared on the stn, and propagated antidromically to the dgn and orthodromically to the son (Fig. 3B, f = 4.37 ± 1.18 Hz; N = 19).

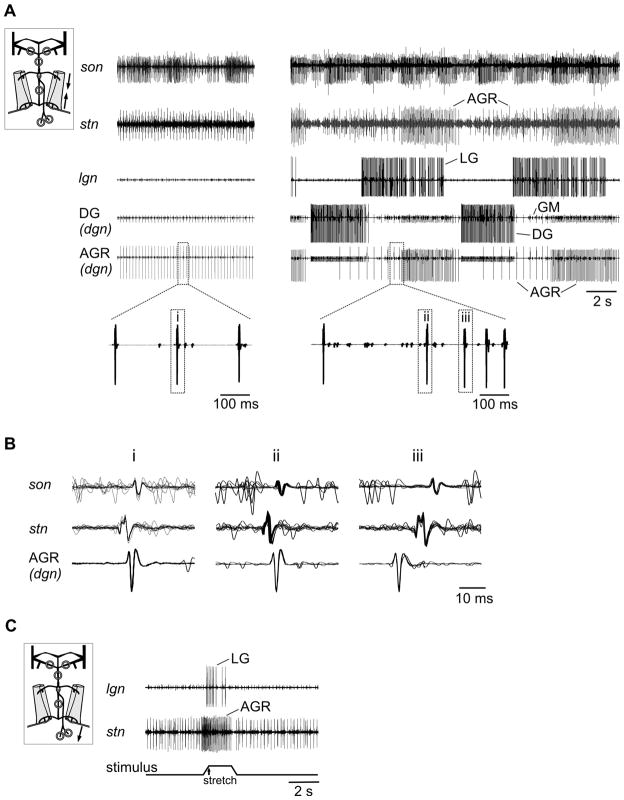

Figure 3.

The direction of AGR spike propagation depended on whether AGR was tonically or phasically active in the neuromuscular preparation. A. Left: Extracellular recordings of son, stn, lgn and dgn (two lower traces). For illustration, the size of DG was enlarged on the DG/dgn trace and that of AGR on the bottom trace (AGR/dgn). Right: After dpon stimulation a gastric mill rhythm was present. AGR was phasically activated during the protraction phase (indicated by the activity burst of the protractor neuron LG). In between phasic activity, AGR was tonically active. Inset: Stretch of dgn recording which shows the change in AGR action potential shape when it switches from tonic (i, ii) to phasic (iii) activity. B. Multisweep recordings of son, stn, and dgn. Left (i): during tonic activity, the AGR spike first appeared on the stn and propagated to the son and dgn (n = 10 sweeps). Middle (ii): in between AGR bursts, spikes first appeared on the stn, then on the son and dgn (n = 10 sweeps). Right (iii): AGR spikes were generated in a posterior section of AGR and thus first appeared on the dgn, then on stn and son (n = 10 sweeps). C. When passive stretch was applied to one of the two bilaterally symmetric gm1 muscles, AGR was activated and, as a consequence, the LG motor neuron started to fire. Schematic insets in A and C indicate recording in neuromuscular preparation.

When we elicited a gastric mill rhythm with extracellular stimulation of the nerve dpon (Fig. 3A right; see also Beenhakker et al., 2004), the gm1 muscles performed isometric contractions and AGR firing frequency increased phasically: Whenever the protractors (GM and LG neurons) were active, AGR generated a burst of action potentials (Fig. 3A, right). In between its bursts and after a short pause in firing AGR returned to tonic activity. The AGR spikes during these intervals of tonic activity were generated in the stn (Fig. 3B, ii), as they were during the tonic activity in the absence of the gastric mill rhythm described above. During the bursts, however, the timing of the action potentials on the different nerves indicated that spikes were generated in the posterior section of AGR and thus near the muscle (Fig. 3B, iii). Therefore, the direction of spike propagation changed depending on whether AGR was bursting or tonically active with low firing frequencies.

Similarly, when we applied passive stretch to the muscles (in the absence of a gastric mill rhythm) by moving the micromanipulator connected to the posterior muscle in the posterior direction (N = 8 preparations), AGR responded with an increase in firing frequency (Fig. 3C). Here, as in the case of the AGR bursts during the gastric mill rhythm, the action potentials originated close to the muscle and traveled towards the CoGs. In accordance with previous studies (Smarandache & Stein, 2007) the activity of the motor circuits in the STG was affected whenever AGR firing frequency exceeded 10 Hz in this condition. Since all AGR actions are mediated indirectly via interneurons in the CoGs (Smarandache & Stein, 2007), the spikes generated at the muscle spike initiation zone must have reached the CoGs. In fact, in all eight tested animals not only stretch-elicited but also tonically occurring spikes appeared on the son recording (Fig. 3B, i), which indicates that both types of action potentials invaded the CoGs and affected the targets of AGR in these ganglia. Furthermore, spike shape and amplitude on the son were similar for both types, which further supported this hypothesis.

(3) Isolated STNS preparations

We found similar results when all muscles were removed and consequently the AGR dendrites which innervate the muscles were severed (N = 53). AGR was tonically active in all preparations (f = 2.91 ± 1.33 Hz). In about half of the isolated STNS preparations the spike initiation zone in the anterior section of AGR was responsible for the spontaneous activity (f = 2.86 ± 1.09 Hz; N = 26 of 53; see also Fig. 6A, example shown in Fig. 4A, left). In 21 preparations, spikes first appeared on the dgn and traveled in anterior direction (f = 3.01 ± 1.61 Hz; Fig. 4A, right). They were thus generated by the posterior spike initiation zone. In six preparations, episodes were found during which spontaneous activity was observed at both the anterior and the posterior spike generating areas such that action potentials were traveling in both directions at the same time. Because the firing frequencies were generally low and, moreover, the total length of stn and dgn is below two centimeters, spike collisions occurred whenever spike initiation on both sides was within a few tens of milliseconds. Spike collisions were obvious from spike failures on one of the recordings. Figure 4B demonstrates this for an AGR action potential which originated in the stn section of the AGR axon (outlined arrow), but did not reach the dgn recording because it collided with a spike traveling in the opposite direction (* in Fig. 4B). After the collision, the direction of spike propagation changed and subsequent action potentials (black arrows) were generated at the posterior spike initiation zone.

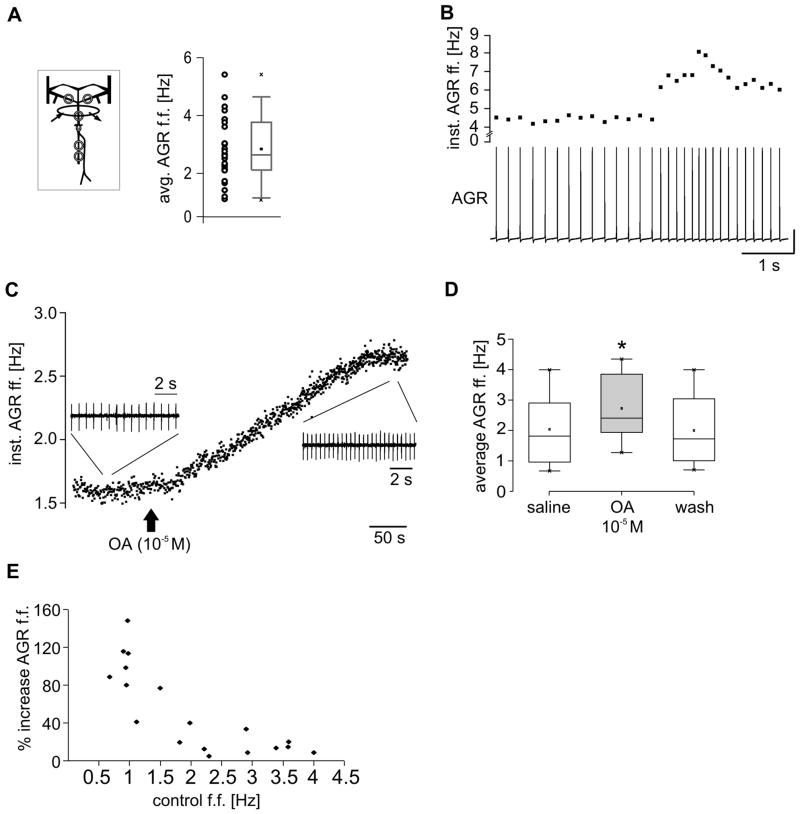

Figure 6.

Octopamine (OA) excites the anterior spike initiation zone. A. Variability of firing frequencies of the anterior spike initiation zone in vitro. Plot of average tonic AGR firing frequency for different animals and boxplot summarizing 26 preparations. Number of trials per animal 20 < n < 307. B. Spontaneous increase of AGR firing frequency. Top: instantaneous AGR firing frequency. Bottom: intracellular AGR recording. Vertical scale bar: 20 mV, most hyperpolarized membrane potential: −62 mV. C. Instantaneous firing frequency of AGR during Octopamine (OA; 10−5 M) application to the stn. Octopamine excited the anterior spike initiation zone. Insets: Original recordings of AGR spikes on dgn in saline (left) and in octopamine (right), demonstrating the increase in AGR firing frequency. D. Boxplot of AGR firing frequency in saline, octopamine and washout (N = 18 animals; trial number per animal: n > 41. Shown are the 25% and 75% percentiles plus median (line) and mean (small square). The whiskers give minimum and maximum values. E. The octopamine effect on AGR firing frequency depended on the control firing frequency (in saline). Plot of percentage increase in firing frequency as a function of the control frequency. Schematic inset in A indicates in vitro recording.

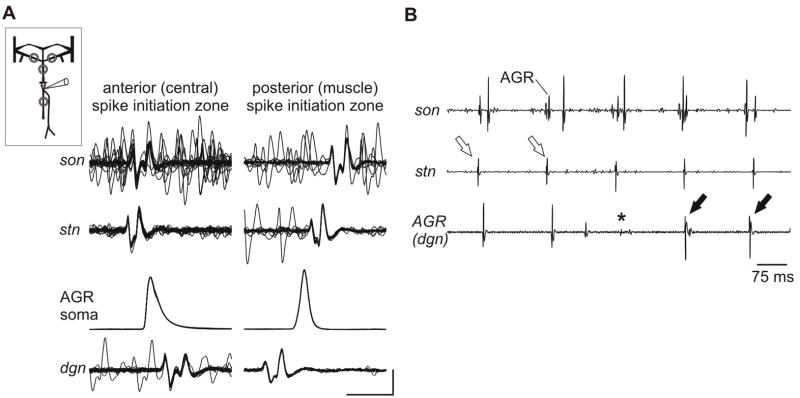

Figure 4.

Action potentials originating at different spike initiation zones can collide on the common axon. A. Multisweep recordings of son, stn, AGR soma and dgn in vitro. Left: AGR spikes were generated at a spike initiation zone in the stn and propagated to the soma and the dgn as well as to the son (n = 25 sweeps). Right: AGR spike first appeared on the dgn and propagated to the son (n = 12 sweeps). Vertical scale bar: 20 mV; horizontal scale bar: 20 ms. B. Extracellular recordings of son, stn and dgn showing a switch in the direction of spike propagation and a collision of antidromic and orthodromic action potentials. Outlined arrows indicate action potentials that were elicited at the anterior spike initiation zone. Black arrows indicate spikes elicited at the posterior initiation zone. The different types of action potentials collided in the axon such that one spike was missing on the dgn recording (*). Schematic inset in A indicates in vitro recording.

Switching off the active spike initiation zone activates the other

The results presented in Fig. 4B indicate that whichever spike initiation zone has the highest intrinsic firing frequency is active. We tested this hypothesis by applying high divalent saline (HI-DI) selectively to either the stn or dgn (Fig. 1A) in isolated STNS preparations. Seven preparations for each condition were tested. HI-DI increases spike threshold and thus reduces the firing frequency of a neuron if applied to the area where spikes are initiated (Beenhakker et al., 2004). Figure 5A shows the result of an experiment in which the anterior spike initiation zone was active with a firing frequency of 2.6 Hz. Immediately after application of HI-DI to the stn the direction of spike propagation changed and spikes were now generated at the posterior spike initiation zone (Figs. 5B & 5C). Spike frequency dropped to 1.9 Hz, suggesting that the posterior spike initiation zone possessed a lower intrinsic firing frequency than the anterior zone, which allowed the anterior zone to lead the pace of AGR activity in control conditions.

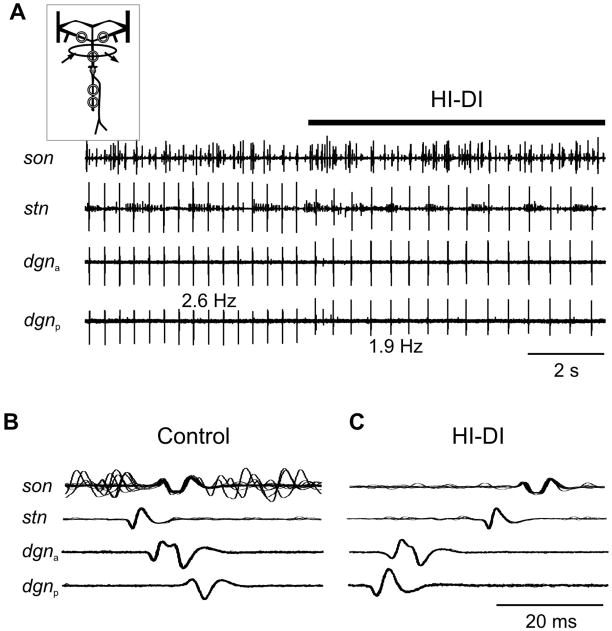

Figure 5.

Decreasing the intrinsic firing frequency of the anterior spike initiation zone activates the posterior spike initiation zone. A. Original recording of AGR on the son, stn and dgn during application of HI-DI to the stn. The dgn was measured at two recording sites, one close to the STG (dgna) and another one more posterior on the nerve (dgnp). In HI-DI, AGR spike frequency dropped and spike shape changed. B. Multisweep recordings showing that in saline action potentials were generated at the anterior spike initiation zone in the stn (n = 16 sweeps). C. Multisweep recordings showing that during application of HI-DI to the stn action potentials were generated at the posterior spike initiation zone (n = 10 sweeps).

Similarly, in preparations in which the posterior spike initiation zone was spontaneously active, application of HI-DI to the dgn changed the direction of spike propagation and the anterior initiation zone became active. The direction of spike propagation could be reverted in both experimental conditions by washing the stn or dgn, respectively, with saline, thus restoring the original firing frequencies. When the soma was hyperpolarized by intracellular current injection or voltage clamped, the two spike initiation zones were active independently (N = 5).

Octopamine excites the anterior spike initiation zone

There is a great variability in average AGR firing frequency among animals (Fig. 6A; N = 26). We also found sudden changes in AGR firing frequency within single preparations. Figure 6B shows an intracellular recording of a spontaneously active AGR. Without experimental perturbation, AGR frequency increased from about 4.5 Hz to 7 Hz in less than a second. Similar changes in firing frequency were also seen in intact animals. How can such changes be mediated? The anterior spike initiation zone is located in the stn, and it has been shown previously that neuromodulators such as octopamine act on axons in this nerve (Goaillard et al., 2004). We thus tested whether the AGR anterior spike initiation zone is sensitive to such modulatory influences by applying 10−5 M octopamine selectively to the stn (see Fig. 1A). All other parts of the STNS were superfused with regular saline. In all experiments octopamine application increased tonic AGR firing (N = 18). Figure 6C shows the time course of the change in AGR firing frequency during octopamine application. The insets show the original recording of AGR on the dgn immediately before octopamine application and at the point of its maximum effect. On average, octopamine increased the firing frequency significantly from 2.04. ± 1.11 Hz in saline to 2.73 ± 0.99 Hz (N = 18; χ22 = 27.111, P ≤ 0.001; Friedmann RM-ANOVA on Ranks) which returned to near control values after wash (2.00 ± 1.12 Hz).

Octopamine effects appeared weaker in preparations with higher spontaneous firing frequencies, indicating that perhaps its excitatory actions are state-dependent, as seen with other modulators (Nusbaum & Marder, 1989). Plotting the percentage increase in AGR firing frequency as a function of the control frequency (Fig. 6E) confirmed that octopamine had a prominent effect when AGR firing frequencies were low, but a much weaker effect when they were high.

In contrast, octopamine application to the posterior spike initiation zone did not change AGR firing frequency (N = 3). In summary, our results demonstrate that the firing frequency of the anterior spike initiation zone is subject to neuromodulatory influences and may thus be activated and regulated separately from that of the posterior zone. Furthermore, they support the hypothesis that the spike initiation zone with the highest firing probability drives the firing of the neuron in a winner-take-all manner. The firing probability of the central spike initiation zone can be increased with octopamine and that of the peripheral zone by stretch of the muscle (sensory function).

Changes in tonic firing affect the motor activity

Previous studies have pointed out that AGR can show tonic activity even in the presence of ongoing gastric mill and pyloric rhythms (Smarandache & Stein, 2007). Our data show that this tonic AGR activity originates from the anterior spike initiation zone and that it can elicit higher firing frequencies under neuromodulatory influences (Fig. 6D). Could this centrally generated tonic activity affect the motor circuits and thus provide an additional function besides the known afferent coding of muscle tension?

To investigate this question we recorded the AGR soma intracellularly and injected either repetitive or tonic depolarizing current. The first was used to elicit tonic AGR activity with different, but defined frequencies. Current injections into the AGR soma elicited a third type of action potential. These first appeared on the intracellular recording and with a brief delay on dgn, stn and son recordings and thus traveled in both directions (Fig. 7A, i). The presence of these action potentials on the son indicates that they also invaded the CoGs. In support of this hypothesis, we found that whenever current injection was strong enough to elicit firing frequencies of 10 Hz and more, AGR stimulation affected the STG motor neurons (Fig. 7A, ii), an effect known to be mediated via the activity of the CoG projection neurons (Smarandache & Stein, 2007). Spike initiation at the AGR soma suppressed the initiation of spikes in other zones whenever the elicited spike frequency exceeded the spontaneous frequency.

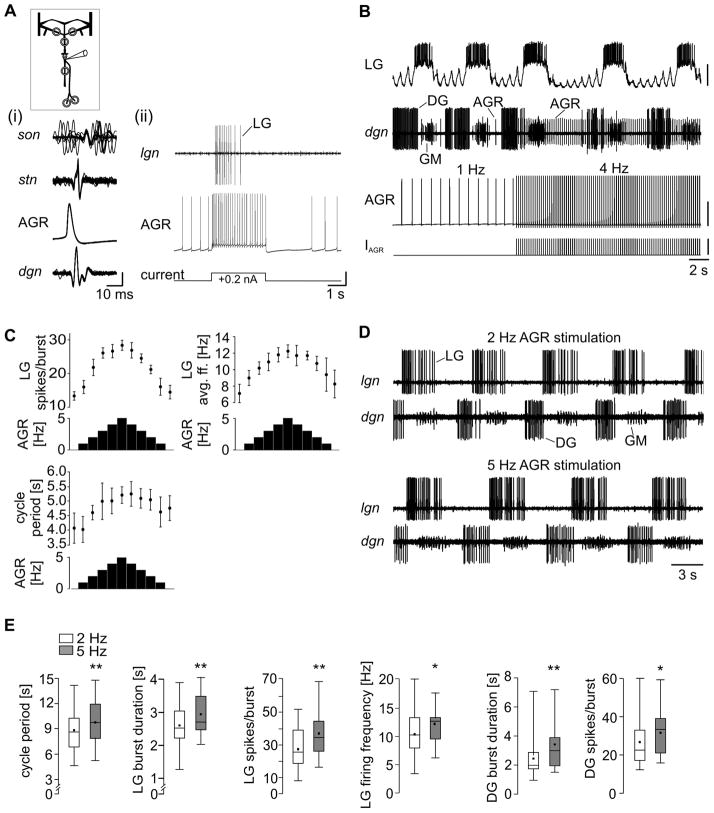

Figure 7.

Changes in tonic AGR firing affect the gastric mill motor pattern. A. (i). Multisweep recordings of dgn, AGR (intracellular trace), stn and son which demonstrate that action potentials elicited by current injection reached the son. (ii). AGR activity elicited by current injection affected motor activity. Vertical scale bars, 20 mV. B. Effect on ongoing gastric mill rhythm. AGR firing frequency was increased via repetitive current injections into the soma from a spontaneous activity of about 1 Hz to 4 Hz. Intracellular recording of the lateral gastric neuron LG along with extracellular recording of dgn showing the activities of DG and GM (4 cells). Bottom: intracellular AGR recording and current injection. Most hyperpolarized Vm LG: −73 mV; AGR: −60 mV. Scale bars, LG: 20 mV; AGR: 40 mV; IAGR: 5 nA. C. Effect of increasing and decreasing AGR firing frequency on the gastric mill motor rhythm in one animal. Shown are the effects on LG spikes per burst and firing frequency, as well as on gastric mill cycle period. Number of cycles measured in each condition: 9≤n≤12. D. Comparison of ongoing gastric mill rhythm during 2 Hz AGR (top) and 5 Hz (bottom) stimulation. AGR activity was digitally removed from the dgn recording. E. Box plots of several gastric mill rhythm parameters (N = 15) at 2 Hz (white) and 5 Hz (grey) AGR stimulation frequency. Trial number per animal: 8 ≤ n ≤ 18. Shown are the 25% and 75% percentiles plus median (line) and mean (small square). The whiskers give minimum and maximum values. Schematic inset in A indicates in vitro recording.

We then tested the impact of changes in AGR frequency on the gastric mill and pyloric motor patterns. The first requires inputs from higher control centers in the CNS (such as the projection neurons in the CoGs) in order to be active. We elicited the gastric mill rhythm with dpon stimulation (see Materials and Methods), which causes a long lasting activity of specific modulatory projection neurons in the CoGs (Blitz et al., 2004). Measurements were taken after the end of the dpon stimulation. Figure 7B shows an example recording of the elicited gastric mill rhythm. Spontaneous AGR firing frequency was about 1 Hz (Fig. 7B, left). We then stimulated AGR with a frequency of 4 Hz. Immediately after the onset of stimulation, the gastric mill rhythm changed noticeably (Fig. 7B, right). The most prominent effect of the increase in tonic AGR activity was an increase in cycle period. A more systematical change of AGR firing frequency in one-Hertz steps from 0 Hz to 5 Hz and back revealed that several rhythm parameters were affected by even a 1 Hz change of tonic firing frequency. Figure 7C shows this effect in a single preparation, in which the LG neuron number of spikes per burst, its intraburst firing frequency and the cycle period of the rhythm showed changes that corresponded to those of AGR: they increased with increasing AGR firing frequency and they decreased again when AGR firing frequency was decreased. The LG number of spikes per burst, for example, increased from 13.27 ± 1.3 (N = 11) when AGR was silent to 28.27 ± 1.5 (N = 11) when AGR was stimulated with 5 Hz and it decreased again to 14.40 ± 2.0 (N = 10) when AGR firing stopped. During the same stimulation, intraburst firing frequency of LG increased from 7.11 ± 1.1 Hz (N = 11; AGR silent) to 12.26 ± 0.8 Hz (N = 11; 5 Hz AGR stimulation) and returned to 8.25 ± 1.7 Hz (N = 10; AGR silent). The gastric mill cycle period showed a hysteresis during this stimulation protocol. While it increased from 4.07 ± 0.5 s (N = 10) when AGR was not firing to 5.21 ± 0.3 s (N = 10) during 5 Hz AGR stimulation, it did not fully return to its original value, but rather averaged 4.76 ± 0.4 s (N = 9) when AGR stimulation ended.

Due to the fact that AGR firing frequency could not be reliably turned off or depressed to 1 Hz in all preparations, we compared the effects of a 2 Hz tonic firing to those at 5 Hz in all investigated preparations. Figure 7D shows a gastric mill rhythm during these two stimulation frequencies (top two recordings: 2 Hz; bottom two recordings: 5 Hz). Clearly, the 3 Hz increase of tonic AGR activity slowed down the rhythm. On average, we found a significant increase in the gastric mill cycle period from 8.73 ± 2.5 s to 9.71 ± 2.8 s (P = 0.001); LG burst duration from 2.64 ± 0.7 s to 2.93 ± 0.6 s (P = 0.008); LG spikes per burst from 27.85 ± 13.5 to 36.47 ± 13.8 (P = 0.002); and LG firing frequency from 10.36 ± 4.4 Hz to 12.05 ± 3.3 Hz (P = 0.03; all comparisons N = 15; non-directional paired t-test; Fig. 7E).

For the retractor neuron DG, we found different effects of AGR firing frequency, depending on when its activity was measured. This is exemplified by the recordings in Figs. 7B and 7D. In Fig. 7D (bottom), which shows DG activity several gastric mill cycles after the increase of AGR firing frequency, DG bursts appear to be of longer duration. In fact, when we measured eight or more consecutive cycles after the change in AGR firing frequency, DG burst duration increased significantly from 2.61 ± 1.6 s to 3.42 ± 1.9 s (N = 15; P = 0.009; non-directional paired t-test; Fig. 7E). DG bursts during 5 Hz AGR stimulation contained significantly more spikes than during 2 Hz stimulation (27.59 ± 13.9 during 2 Hz stimulation, 31.80 ± 12.6 during 5 Hz stimulation, N = 15; P = 0.01; non-directional paired t-test). In contrast, Figure 7B shows the immediate effect of an increase in AGR firing: The first DG burst after the onset of AGR stimulation was clearly weaker and shorter than those before the increase in AGR firing frequency.

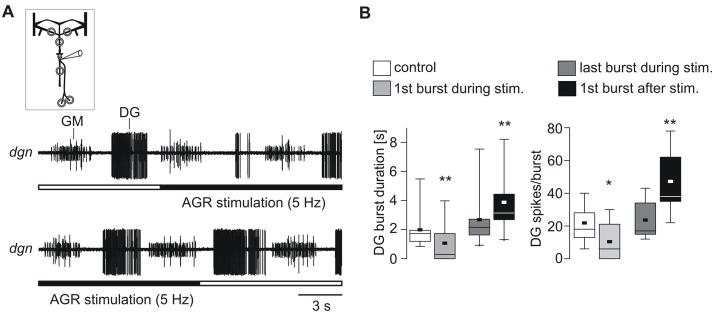

To scrutinize the more transient effects of a change in AGR firing frequency on DG, we compared the DG burst immediately before increasing AGR firing frequency to 5 Hz with that immediately after the transition. Similarly, we compared the last DG burst at 5 Hz to that of the first after the end of stimulation. As seen in Figure 8A, increasing AGR firing frequency shortened the first DG burst (top recording), while turning off the stimulation and a return to the lower firing frequency had the opposite effect and prolonged the burst (bottom recording). The duration of the first DG burst during the 5 Hz stimulation (1.06 ± 1.3 s; median: 0.63 s; N = 10) dropped by more than 46% in comparison to the control DG burst before the 5 Hz situation (Fig. 8B; 1.98 ± 1.3 s; median 1.77 s; N = 10; P = 0.004; non-directional paired t-test). In three of the ten experiments, the first DG burst was completely suppressed. In contrast, the burst duration of the first DG burst after the end of the 5 Hz stimulation (3.88 ± 2.0 s; median: 3.31 s; N = 10; non-directional paired t-test) was more than 45% longer than the DG burst immediately before the end of the 5 Hz stimulation (2.66 ± 1.9 s; median: 2.18 s; N = 10; P = 0.006; non-directional paired t-test). The transient effects due to the changing of the AGR firing frequency were also mirrored by the number of DG spikes per burst: DG generated significantly more spikes immediately before AGR firing frequency was increased, compared to right after the increase (21.80 ± 11.4; median:19.0, before increase vs. 10.40 ± 11.7; median: 7.0, after; N = 10; P = 0.014; non-directional paired t-test). When we decreased AGR firing frequency again the number of DG spikes per burst doubled from 23.60 ± 11.3 (median: 17.0) to 47.20 ± 18.2 (median: 45.5; N = 10; P = 0.004; non-directional paired t-test). In fact, the number of DG spikes in the burst following the transition back to 2 Hz was even significantly higher than that of the control situation before the 5 Hz stimulation (N = 10, P = 0.002; RM ANOVA on Ranks). In summary, even a small increase in the tonic firing of AGR caused (1) higher activities of the LG and DG neurons and a concomitant increase in gastric mill cycle period and (2) transiently diminished DG activity.

Figure 8.

Changes in tonic AGR firing had transient effects on the motor pattern. A. Extracellular recordings of dgn showing that DG burst duration and number of spikes were reduced immediately after the beginning of a 5 Hz stimulation (top) and increased after the end of the stimulation (bottom). AGR activity was digitally removed from dgn recording. B. Box plots showing the results of N = 10 animals. Left: Duration of the control DG burst before AGR stimulation (outlined), first burst during stimulation (light grey), last burst during stimulation (dark grey) and first burst after stimulation (black). Right: Similar, but for DG spikes per burst. Schematic inset in A indicates in vitro recording.

In addition to the effects of AGR on the gastric mill rhythm, we found that the faster pyloric rhythm was also affected by changes in tonic AGR firing. The pyloric rhythm is strongly influenced by the activity of the gastric mill neuron LG (Bartos & Nusbaum, 1997), which, as we show above, is affected by changes in AGR firing (Fig. 7E). Thus, to assess whether the pyloric rhythm was directly affected by changes in tonic AGR firing we considered the pyloric response in the absence of the gastric mill rhythm. This could be done, because, unlike the gastric mill rhythm, the pyloric rhythm is spontaneously active in vitro without stimulation of modulatory projections.

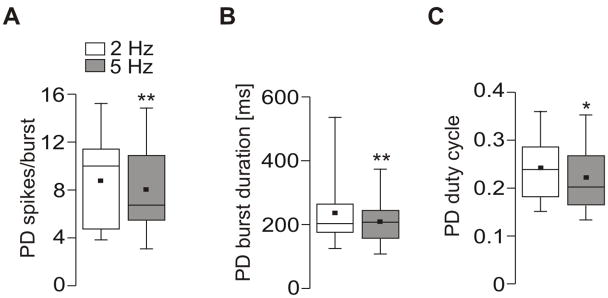

Only the activities of the PD neurons were affected by changes in tonic AGR firing while all other pyloric parameters remained unchanged. When we compared AGR firing at 2 Hz and 5 Hz, the number of PD spikes per burst showed a small but consistent decrease from 8.7 ± 3.9 (median: 10.0) to 8.0 ± 3.8 (median: 6.7; N = 12, P = 0.042; non-directional paired t-test; Fig. 9A). At the same time, PD burst duration decreased from 237 ± 111 ms (median: 203) to 210 ± 73ms (median: 207; N = 12, P = 0.01; non-directional paired t-test; Fig. 9B) such that PD firing frequency did not change. The PD duty cycle, however, was shortened from 0.24 ± 0.07 (median 0.24) to 0.22 ± 0.06 (median: 0.20; N = 12, P = 0.019; non-directional paired t-test; Fig 9C).

Figure 9.

Changes in AGR firing frequency influence the PD neurons. Box plots (N = 12) of PD number of spikes per burst (A), PD burst duration (B), and duty cycle (C) during 2 Hz and 5 Hz AGR stimulation. Given are the 25% and 75% percentiles as well as median (line) and mean (small square). The whiskers show minimum and maximum values.

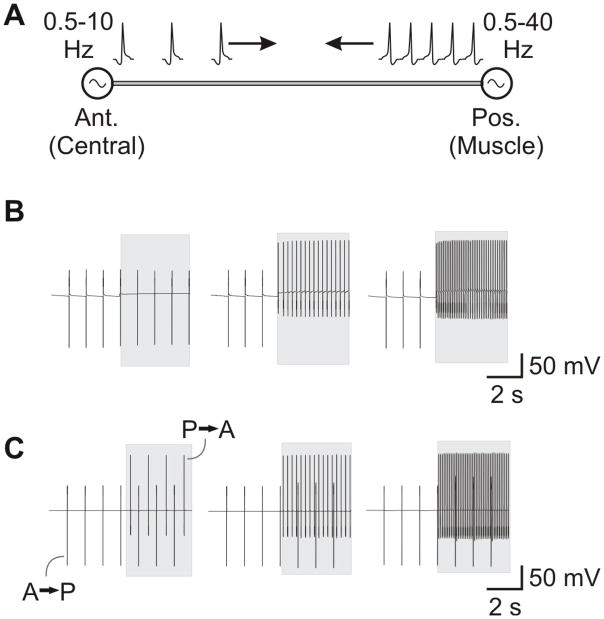

Our results so far have demonstrated that AGR possesses two spatially separated spike initiation zones and that activity of both initiation zones is functionally relevant. The anterior appears to be responsible for the spontaneous tonic activity usually present in AGR, and its spikes can collide with those from the posterior initiation zone on the common axon. To test whether these collisions can interfere with the sensory information about muscle tension provided by the posterior spike initiation zone, we used a computational model of the AGR axon between both spike initiation areas (Fig. 10A). In this model, the axon had a constant conduction velocity of ~2 m/s and a length of 20 mm. Spikes were initiated at both axon terminals and traveled towards the opposite end. We used a range of firing frequencies for each spike initiation zone. The anterior zone generated spikes with firing frequency between 0.5 and 10 Hz, while the posterior zone ranged from 0.5 to 40 Hz. We chose these frequencies to overlap the range of frequencies observed for tonic AGR firing in intact animals (Fig. 2B) and phasic AGR activity (Smarandache et al., 2008). We then varied both frequencies independently and examined whether one spike initiation zone dominated. We used two protocols: Either the initiation zone was depolarized with injected DC current (or, equivalently, with a tonic modulatory conductance; see methods) or it was stimulated with brief 2 ms current pulses (or, equivalently, with brief excitatory EPSPs). The latter mode of stimulation should imitate the potential possibility that action potentials in the anterior zone may be generated due to electrical or chemical excitation of AGR by another neuron.

Figure 10.

Model of the AGR axon and the two sites of spike initiation. A. The AGR was modeled as a 20 mm long axon with diameter of 5 μm based on the Connor-Stevens model (Connor & Stevens, 1971). Action potentials were generated on the anterior end at 0.5–10 Hz and the posterior end at 0.5–40 Hz. B. When action potentials at the anterior end were generated by depolarization of the anterior end, they were suppressed when the posterior end produced action potentials at higher rates (middle and right panels) but not when it produced action potentials at equal or lower rates (left panel). C. In contrast, when action potentials at the anterior end (A→P) were generated with brief excitatory stimuli (here 2 ms, 2 nA current pulses), they were not suppressed by action potentials generated from the posterior end (P→A), even when the latter were at rates up to 10 times higher. At even higher rates, the posterior end suppressed the action potentials generated in the anterior end (not shown). Here, the action potentials at the posterior end are generated by depolarizing that end. In B and C: the anterior end is stimulated throughout the 8 second trace but the posterior end is stimulated in the latter half (light grey boxes); the anterior end is stimulated to produce activity at around 1 Hz; the posterior end is stimulated to produce activity at 1 (left), 4 (middle) or 10 (right) Hz; shown is the difference between the voltages of two axon locations that are 400 μm apart.

When action potentials at the two ends were generated by depolarization, the site that generated a higher frequency always dominated and suppressed the opposite spike initiation zone (e.g., Fig 10B). When the two zones had frequencies within 0.5 Hz, the zone that produced spikes first dominated (e.g., the leftmost panel of Fig. 10B). Spike collisions were rare, because each action potential traversed the length of the axon within 10 ms. When spike collision occurred, it was only for a single spike, after which the higher-frequency zone dominated (e.g., the middle and right panels of Fig. 10B).

In contrast, when one or both zones were stimulated with brief pulses, the action potentials generated on the two sides would pass through to the opposite side without suppressing the ability of the opposite side to generate spikes, even when the spike frequency on one side was up to ten times higher than on the opposite side (e.g. Fig. 10C). Yet, when spike frequency on one side was more than ten-fold larger than on the opposite side it would typically dominate and silence the opposite spike initiation zone. This result implies that if the centrally-generated spikes were due to excitation of AGR by another neuron, these spikes would not necessarily be suppressed by the afferent sensory spikes.

Together, these modeling results suggest that (1) action potentials generated in the central spike initiation zone are due to modulation of the AGR axon rather than to excitation from another neuron and (2) action potentials generated at the spike initiation zone in the anterior section of AGR do not affect the afferent sensory function of AGR. Additionally, the dominance of the high-frequency spike initiation zone indicates that phasic activity of AGR (during which spike frequency is high) would suppress the central tonic activity during each burst but centrally-generated tonic activity may be present between bursts of phasic activity.

Discussion

It is generally assumed that the spike activity of sensory neurons informs the CNS about the sensory stimulus to which it responds. Here, we show that the muscle tendon organ AGR possesses two spike initiation zones, one of which is located spatially distant from the innervated muscle in a central section of the sensory axon. This initiation zone generates tonic activity and it is responsible for the spontaneous activity of the sensory neuron in vivo. The tonic activity originating from this initiation zone is functionally relevant, because it changes the activity state of the gastric mill CPG and has a small influence on the pyloric CPG. Interestingly, the central spike initiation zone of AGR is sensitive to the neuromodulator octopamine. This modulatory amine has been shown to be present in unidentified neuronal processes and to modulate the actions of projection axons in this region of the CNS (Goaillard et al., 2004). Thus, our results indicate that central neuromodulation of the sensory neuron AGR produces a baseline tonic activity that influences rhythmic motor activity when AGR is not acting in its sensory capacity.

Consequences of tonic activity in AGR for the gastric mill motor output

Many proprioceptors provide phasic and/or tonic excitatory input to the central nervous system. AGR phasic activity can shape and even entrain the gastric mill motor output and, interestingly, the AGR influence during its phasic activity can be modified by actions of other sensory inputs such as the pyloric stretch receptor neurons (Barriere et al., 2008). Besides its phasic activity, AGR is often tonically active in the absence of the gastric mill rhythm, but also when a gastric mill rhythm is present. It is these situations, in which AGR can affect the state of the motor system. Here, we show that tonic AGR activity even at low firing frequencies affects a gastric mill rhythm that was elicited by a different sensory pathway. While we never observed that tonic stimulation of AGR elicited a gastric mill rhythm if none had been present before (as observed during phasic stimulation; Smarandache & Stein 2007), it clearly affected ongoing rhythms. Tonic AGR activity thus appears to set the stage for other inputs (central or sensory) that act on the STNS circuits. If these inputs activate the gastric mill rhythm or enhance ongoing rhythms, tonic AGR activity could consequently lead to the activation of its own sensory activity. In this case, changes in the firing frequency of the central spike initiation zone would determine the sensitivity of the system to different other sensory stimuli.

The effects of changes in tonic AGR firing were particularly obvious in the activity of the retractor neuron DG. While the steady state effect of a higher AGR firing frequency on DG was an increase in burst duration, the immediate response was a weakening of the DG burst. Similarly, the effect of lowering the AGR firing frequency was a transient increase in the DG burst duration but a long-term reduction in this duration. These bidirectional effects can be explained by a combination of fast inhibition and a larger but slower excitation. It has previously been shown that AGR indirectly inhibits DG (Smarandache & Stein, 2007), most likely via its actions on the descending projection neurons in the commissural ganglia. The origin of the excitatory response in steady state is unknown. Some descending projection neurons, however, are capable of releasing transmitter at firing frequencies as low as 2 Hz (Stein et al., 2007). If they also respond to small changes in firing frequencies of their presynaptic neurons, they may well provide the necessary input to excite DG.

An increase in the tonic activity of AGR also had a small but significant influence on the pyloric PD neurons. Because these neurons are members of the pyloric pacemaker ensemble which is the primary drive of the pyloric rhythm, such a reduction has consequences for the phase relationship of the network and could potentially modify the motor function.

Why are sensory neurons spontaneously active?

Many sensory neurons show low-level tonic activity in the absence of sensory stimuli. The function of such activity is mostly unknown, but is often considered a mechanism to increase the sensitivity of the sensory organ to stimuli allowing for quicker and more reliable responses to sensory inputs. For example, the photoreceptors of the eye tonically release transmitters (Heidelberger, 2007), such that even small changes in their membrane potential affect the postsynaptic cells. While this may be true for stimulus-driven activity, the function of a centrally-generated activity in a sensory neuron must be different. We demonstrate that centrally-generated activity of a sensory organ affects the response of the nervous system to inputs from other sensory organs that perceive different sensory modalities. Specifically, tonic activity of the muscle tendon organ modifies the motor rhythm activated in response to mechanosensory input provided by the ventral cardiac neurons, which we activated by stimulating the sensory nerve dpon.

We found that the tonic firing frequency of AGR, even at low values, can alter the response of gastric mill and pyloric neurons. More importantly, the state of the motor network is sensitive to small changes in the AGR firing frequency (as low as 1 Hz), indicating a fine-tuned coding of the motor state by the stimulus-independent activity of the sensory neuron.

Multiple spike initiation zones

The existence of multiple spike initiation zones in individual neurons has been demonstrated in a large number of invertebrate and vertebrate preparations and in a variety of cell types, including interneurons (Hughes & Wiersma, 1960; Tauc & Hughes, 1963; Calabrese, 1980; Chen et al., 1997), motor neurons (Kriebel et al., 1969; Korn & Bennett, 1971; Vedel & Moulins, 1977) and sensory neurons (O’Shea, 1975; Combes et al., 1993; Westberg et al., 2000; Evans et al., 2003). The function of multiple sites of spike initiation is often not clear. If present in dendrites, they appear to be involved in the integration of synaptic inputs from different, spatially separated sources. For example, the Lateral Giant Movement Detector in the locust possesses one spike initiation zone for visual input, and another one for auditory input (O’Shea, 1975). It has been suggested that multiple trigger zones could functionally subdivide the neuron (Antic et al., 2000), and that mechanisms exist that change the impulse origin, the direction of impulse propagation, and the pattern of activity (Chen et al., 1997; Antic et al., 2000).

Multiple spike initiation zones on the axon appear to be less frequent, but have also been demonstrated to exist in several systems (for review see Pinault, 1995). In small nervous systems it may be advantageous to combine multiple functions in a single cell for neural economy (Heitler & Goodman, 1978; Clark et al., 2006), for example by adding spatially separated axonal spike initiation zones that innervate different targets (Killian et al., 2000).

Our results demonstrate that multiple spike initiation zones that perform different functions can exist on the same axon. When performing sensory tasks, AGR activates the gastric mill motor systems and provides cues for its timing (Smarandache & Stein, 2007). In contrast, when no sensory information is provided, the central spike initiation becomes active, leading to a functional compartmentalization of AGR. Our results suggest that the central axonal tree is acting as a premotor interneuron regulating the state of the motor system. A similar functional compartmentalization has been shown on the population level in muscle spindle afferents of the rabbit trigeminal muscle. During particular phases of mastication, the central axons of these afferents appear to be decoupled from their stem axons and somata and generate action potentials in response to synaptic input (primary afferent depolarization). Their central axons thus act as premotor neurons carrying inputs from the masticatory CPG.

Action potentials generated at AGR’s central initiation site are also conducted antidromically toward the soma. Antidromic spiking, in general, may transfer some kind of information about the state of the neuron to its dendrites (for reviews see Pinault, 1995; Waters et al., 2005) and, in sensory neurons, potentially modulate the fidelity of afferent signaling (Bevengut et al., 1997; Lin & Fu, 1998; Cattaert et al., 1999; Gossard et al., 1999; Le Ray et al., 2005; Rossignol et al., 2006). They may also interfere with orthodromic spike propagation. One of the best known examples of such interference is the collision of antidromic spikes in the dorsal root reflex pathway (for review see Rossignol et al., 2006). For AGR, our model indicates that the activity of the central spike initiation zone should not interfere with sensory signals as long as the sensory signals cause AGR to produce a higher spike rate than the central spike initiation zone. Additionally, the model indicates that the central activity of AGR is not caused by excitatory input from another neuron and is generated intrinsically.

When AGR is tonically active, the intrinsic spike frequencies of the different spike initiation zones determine which zone is active. We demonstrate that the central spike initiation zone is excited by octopamine and that the increase of its firing frequency is sufficient to shut off tonic firing of the muscle spike initiation zone. A lack of neuromodulatory actions at the anterior spike initiation zone may thus also account for the generally lower AGR firing frequencies in isolated STNS preparations when compared to intact animals and also for the fact that in almost half of these preparations the muscle spike initiation zone was active. Neuromodulatory actions on axons have been demonstrated in the STNS (Meyrand et al., 1992; Bucher et al., 2003; Goaillard et al., 2004; Le et al., 2006), but not for sensory neurons. In most examples, the centrally-generated activity is terminated when the axonal spike initiation zone becomes active. Similarly, we found that octopamine excites the anterior spike initiation zone of AGR which then determines the tonic firing frequency. Thus, the tonic activity generated by sensory neurons can be modulated and maybe even regulated independently from their activity during sensory coding. This indicates a functional role of the second spike initiation zone in controlling the state of the postsynaptic circuits.

Together, our results demonstrate that sensory neurons are not mere reporters of sensory signals, but can modulate both central and sensory information in a manner that depends on the state of a particular motor pattern or the body.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by an Albert and Ellen Grass Faculty Grant to WS and FN at the Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Mass, USA. Additional support was provided by DFG STE 937/5-1, 5-2 and DFG DA 1188/1-1.

Abbreviations

- AGR

anterior gastric receptor

- CNS

central nervous system

- CoG

commissural ganglion

- CPG

central pattern generator

- DG

dorsal gastric neuron

- dgn

dorsal gastric nerve

- dpon

dorsal posterior oesophageal nerve

- f

frequency

- GM

gastric mill motor neuron

- HI-DI

high divalent saline

- LG

lateral gastric neuron

- lgn

lateral gastric nerve

- lvn

lateral ventricular nerve

- OA

octopamine

- PD

pyloric dilator neuron

- pdn

pyloric dilator nerve

- son

superior oesophageal nerve

- STG

stomatogastric ganglion

- stn

stomatogastric nerve

- STNS

stomatogastric nervous system

References

- Antic S, Wuskell JP, Loew L, Zecevic D. Functional profile of the giant metacerebral neuron of Helix aspersa: temporal and spatial dynamics of electrical activity in situ. J Physiol. 2000;527(Pt 1):55–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriere G, Simmers J, Combes D. Multiple mechanisms for integrating proprioceptive inputs that converge on the same motor pattern-generating network. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8810–8820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2095-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Nusbaum MP. Intercircuit control of motor pattern modulation by presynaptic inhibition. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2224–2256. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02247.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenhakker MP, Blitz DM, Nusbaum MP. Long-lasting activation of rhythmic neuronal activity by a novel mechanosensory system in the crustacean stomatogastric nervous system. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:78–91. doi: 10.1152/jn.00741.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevengut M, Clarac F, Cattaert D. Antidromic modulation of a proprioceptor sensory discharge in crayfish. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:1180–1183. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz DM, Beenhakker MP, Nusbaum MP. Different sensory systems share projection neurons but elicit distinct motor patterns. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11381–11390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3219-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz DM, Nusbaum MP. Motor pattern selection via inhibition of parallel pathways. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4965–4975. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-04965.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher D, Thirumalai V, Marder E. Axonal dopamine receptors activate peripheral spike initiation in a stomatogastric motor neuron. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6866–6875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06866.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese RL. Control of multiple impulse-initiation sites in a leech interneuron. J Neurophysiol. 1980;44:878–896. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.5.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaert D, El Manira A, Bevengut M. Presynaptic inhibition and antidromic discharges in crayfish primary afferents. J Physiol Paris. 1999;93:349–358. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(00)80062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WR, Midtgaard J, Shepherd GM. Forward and backward propagation of dendritic impulses and their synaptic control in mitral cells. Science. 1997;278:463–467. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DA, Biron D, Sengupta P, Samuel AD. The AFD sensory neurons encode multiple functions underlying thermotactic behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7444–7451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1137-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes D, Meyrand P, Simmers J. Motor pattern specification by dual descending pathways to a lobster rhythm-generating network. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3610–3619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03610.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes D, Simmers J, Moulins M. Structural and functional characterization of a muscle tendon proprioceptor in lobster. J Comp Neurol. 1995;363:221–234. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes D, Simmers J, Nonnotte L, Moulins M. Tetrodotoxin-sensitive dendritic spiking and control of axonal firing in a lobster mechanoreceptor neurone. J Physiol. 1993;460:581–602. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JA, Stevens CF. Prediction of repetitive firing behaviour from voltage clamp data on an isolated neurone soma. J Physiol. 1971;213:31–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan P, Abbott LF, Massachusetts Institute of, T . Theoretical neuroscience: Computational and mathematical modeling of neural systems. MIT Press; Cambridge, Mass: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Evans CG, Jing J, Rosen SC, Cropper EC. Regulation of Spike Initiation and Propagation in an Aplysia Sensory Neuron: Gating-In via Central Depolarization. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2920–2931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02920.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goaillard JM, Schulz DJ, Kilman VL, Marder E. Octopamine modulates the axons of modulatory projection neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7063–7073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2078-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding NL, Staff NP, Spruston N. Dendritic spikes as a mechanism for cooperative long-term potentiation. Nature. 2002;418:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nature00854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossard JP, Bouyer L, Rossignol S. The effects of antidromic discharges on orthodromic firing of primary afferents in the cat. Brain Res. 1999;825:132–145. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez GJ, Grashow RG. Cancer borealis stomatogastric nervous system dissection. J Vis Exp. 2009 doi: 10.3791/1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberger R. Mechanisms of tonic, graded release: lessons from the vertebrate photoreceptor. J Physiol. 2007;585:663–667. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitler WJ, Goodman CS. Multiple Sites of Spike Initiation in a Bifurcating Locust Neurone. J Exp Biol. 1978;76:63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Holthoff K, Kovalchuk Y, Konnerth A. Dendritic spikes and activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:369–377. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GM, Wiersma CAG. Neuronal Pathways and Synaptic Connexions in the Abdominal Cord of the Crayfish. J Exp Biol. 1960;37:291–307. [Google Scholar]

- Killian KA, Bollins JP, Govind CK. Anatomy and physiology of neurons composing the commissural ring nerve of the cricket, Acheta domesticus. J Exp Zool. 2000;286:350–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn H, Bennett MV. Dendritic and somatic impulse initiation in fish oculomotor neurons during vestibular nystagmus. Brain Res. 1971;27:169–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90379-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel ME, Bennett MV, Waxman SG, Pappas GD. Oculomotor neurons in fish: electrotonic coupling and multiple sites of impulse initiation. Science. 1969;166:520–524. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3904.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristan WB, Jr, Calabrese RL, Friesen WO. Neuronal control of leech behavior. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:279–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ray D, Combes D, Dejean C, Cattaert D. In vivo analysis of proprioceptive coding and its antidromic modulation in the freely behaving crayfish. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:1013–1027. doi: 10.1152/jn.01255.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T, Verley DR, Goaillard JM, Messinger DI, Christie AE, Birmingham JT. Bistable Behavior Originating in the Axon of a Crustacean Motor Neuron. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1356–1368. doi: 10.1152/jn.00893.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TB, Fu TC. Which afferents induce and transmit dorsal root reflex in rats? Neurosci Lett. 1998;247:75–78. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyrand P, Weimann JM, Marder E. Multiple axonal spike initiation zones in a motor neuron: serotonin activation. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2803–2812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02803.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusbaum MP, Marder E. A modulatory proctolin-containing neuron (MPN). II. State-dependent modulation of rhythmic motor activity. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1600–1607. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01600.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea M. Two sites of axonal spike initiation in a bimodal interneuron. Brain Res. 1975;96:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90577-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesch N, Euler T, Taylor WR. Direction-selective dendritic action potentials in rabbit retina. Neuron. 2005;47:739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinault D. Backpropagation of action potentials generated at ectopic axonal loci: hypothesis that axon terminals integrate local environmental signals. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1995;21:42–92. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(95)00004-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol S, Dubuc R, Gossard JP. Dynamic sensorimotor interactions in locomotion. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:89–154. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmers J, Moulins M. A disynaptic sensorimotor pathway in the lobster stomatogastric system. J Neurophysiol. 1988a;59:740–756. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.3.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmers J, Moulins M. Nonlinear interneuronal properties underlie integrative flexibility in a lobster disynaptic sensorimotor pathway. J Neurophysiol. 1988b;59:757–777. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.3.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smarandache CR, Daur N, Hedrich UB, Stein W. Regulation of motor pattern frequency by reversals in proprioceptive feedback. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:460–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smarandache CR, Stein W. Sensory-induced modification of two motor patterns in the crab, Cancer pagurus. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:2912–2922. doi: 10.1242/jeb.006874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein W, DeLong ND, Wood DE, Nusbaum MP. Divergent co-transmitter actions underlie motor pattern activation by a modulatory projection neuron. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1148–1165. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein W, Eberle CC, Hedrich UBS. Motor pattern selection by nitric oxide in the stomatogastric nervous system of the crab. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2767–2781. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein W, Smarandache CR, Nickmann M, Hedrich UB. Functional consequences of activity-dependent synaptic enhancement at a crustacean neuromuscular junction. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:1285–1300. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauc L, Hughes GM. Modes of Initiation and Propagation of Spikes in the Branching Axons of Molluscan Central Neurons. The Journal of General Physiology. 1963;46:533–549. doi: 10.1085/jgp.46.3.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedel JP, Moulins M. A motor neuron involved in two centrally generated motor patterns by means of two different spike initiating sites. Brain Res. 1977;138:347–352. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90751-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters J, Schaefer A, Sakmann B. Backpropagating action potentials in neurones: measurement, mechanisms and potential functions. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2005;87:145–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weimann JM, Meyrand P, Marder E. Neurons that form multiple pattern generators: identification and multiple activity patterns of gastric/pyloric neurons in the crab stomatogastric system. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:111–122. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberg KG, Kolta A, Clavelou P, Sandstrom G, Lund JP. Evidence for functional compartmentalization of trigeminal muscle spindle afferents during fictive mastication in the rabbit. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:1145–1154. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuste R, Tank DW. Dendritic integration in mammalian neurons, a century after Cajal. Neuron. 1996;16:701–716. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]