Abstract

Background

Abdominal surgery is thought to be a risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD). The aims of this study were to discern pre-operative factors associated with post-surgical CDAD, examine outcomes after post-surgical CDAD, and compare outcomes of post-surgical vs. medical CDAD.

Methods

Data from 3904 patients who had abdominal surgery at Montefiore Medical Center were extracted from Montefiore's clinical information system. Cases of 30-day post-surgical CDAD were identified. Pre-operative factors associated with developing post-surgical CDAD were identified using logistic regression. Medical patients and surgical patients with post-surgical CDAD were compared for demographic and clinical characteristics, CDAD recurrence and 90-day post-infection mortality.

Results

The rate of 30-day post-surgical CDAD was 1.2%. After adjustment for age and co-morbidities, factors significantly associated with post-surgical CDAD were: antibiotic use (OR: 1.94), proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use (OR: 2.32), prior hospitalization (OR: 2.27), and low serum albumin (OR: 2.05). In comparison with medical patients with CDAD, post-surgical patients with CDAD were significantly more likely to have received antibiotics (98.0% vs. 85.2%), less likely to have received a PPI (38.8% vs. 58.3%), or have had a prior hospitalization (42.9% vs. 67.1%). Post-surgical patients with CDAD had decreased risk of mortality when compared with medical patients with CDAD (HR 0.36).

Conclusions

CDAD is an infrequent complication after abdominal surgery. Several avoidable pre-operative exposures (e.g., antibiotic and PPI use) were identified that increase the risk of post-surgical CDAD. Post-surgical CDAD is associated with decreased risk of mortality when compared with CDAD on the medical service.

Introduction

Clostridium difficile is the most common nosocomial pathogen and the cause of 10-20% of cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and most cases of antibiotic-associated colitis.1 Both the incidence2 and the severity3 of C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) are increasing in the United States.4-6 Abdominal surgery is thought to be a risk factor for CDAD,7 and post-surgical CDAD has been well described. The reported rates of post-surgical CDAD range from 0.2% to 8.4% depending on the surgical population studied and types of operations performed.7-13 No study has been reported, however, that compares post-surgical CDAD and medical CDAD with respect to risk factors and outcomes.

In the general medical inpatient population, established risk factors for CDAD include: antibiotic exposure,14, 15 advanced age,16, 17 and hospitalization, especially in the intensive care unit.18 Other implicated risk factors include: overall severity of disease,19 use of proton-pump-inhibitors,20-22 previous hospitalizations,23 gastric and post-pyloric tube feedings,24 and chemotherapy.25 Whether some or all of these exposures also are associated with post-surgical CDAD is not known, although prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis8 and the addition of oral preoperative antibiotics9 have been associated with increased risk of post-surgical CDAD.

Developing CDAD has been said to worsen outcomes in the non-surgical inpatient setting26 and in the general population,3 however, no study has reported the outcomes of post-surgical CDAD or made a comparison with the outcomes of CDAD in the non-surgical setting.

The aims of this analysis were to determine pre-operative factors associated with post-surgical CDAD, to examine outcomes of post-surgical CDAD, and to compare the outcomes of patients who had post-surgical CDAD with those who had non-surgical CDAD. We hypothesized that pre-operative factors associated with the development of post-surgical CDAD would include: pre-operative antibiotics, proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), increased length of hospital stay, and previous hospitalization. In addition, we hypothesized that outcomes for patients with post-surgical CDAD would be worse than for post-surgical patients without CDAD.

Methods

Study setting and data collection

Montefiore Medical Center consists of The Moses Division Hospital, a 706-bed tertiary care center, and The Weiler Division Hospital, a 381-bed teaching hospital, both of which are associated with Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The patient populations served by these two hospitals differ with respect to demographic and clinical characteristics, but both hospitals adhere to the same infection control policies and practices administered by a common infection control department, patient safety officer, and antibiotic steward.

To generate the post-surgical C. difficile cohort, we extracted data on all patients who underwent an inpatient abdominal surgical procedure within 30 days of admission to either hospital from January1, 2006 through February 28, 2008. Qualifying abdominal procedures included surgery involving the stomach, small bowel, colon, appendix, anorectum, gallbladder and biliary tract, pancreas, hernia repair or non-otherwise specified abdominal surgery (A full list of procedures and V-codes can be found in appendix 1.)

Appendix 1.

Comparison of two hospital sites

| Weiler (n = 1612) | Moses (n = 2278) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-surgical CDAD | 15 (0.9) | 31 (1.4) | 0.22 |

| Age | 54.5 ± 18.7 | 51.7 ± 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Male | 504 (31.2) | 800 (35.0) | 0.01 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| White | 423 (26.2) | 316 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Black | 473 (29.3) | 693 (30.3) | 0.5 |

| Latino | 597 (37.0) | 1012 (44.3) | <0.001 |

| Oth/Unknown | 122 (7.6) | 266 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| Any antibiotic given* | 438 (27.1) | 604 (26.5) | 0.67 |

| Cephalosporin† | 39 (2.4) | 57 (2.5) | 0.86 |

| Quinolone | 114 (7.1) | 140 (6.1) | 0.26 |

| Clindamycin | 14 (0.9) | 23 (1.0) | 0.65 |

| Imipenim | 19 (1.2) | 23 (1.0) | 0.62 |

| PPI‡ | 166 (10.3) | 225 (9.8) | 0.65 |

| Prior Hosp§ | 328 (20.3) | 477 (20.9) | 0.67 |

| Admission Albumin | 3.58 ± 0.82 | 3.74 ± 0.73 | <0.001 |

| Charlson Score | 2.50 ± 2.74 | 2.18 ± 2.43 | 0.002 |

Continuous variables reported as mean ± standard deviation

Dichotomous variables reported as number (percent)

any antibacterial given within 30 days before surgical procedure

3rd or 4th generation cephalosporins: cefipime, ceftriaxone, cefpodoxime, cefotaxin

any PPI given within 10 days before surgical procedure

any hospitalization within 180 days before surgical procedure

To generate the comparison cohort of C. difficile on the medical service we extracted data on all inpatients on the medical service from both hospitals who had a positive C. difficile toxin test from January 1, 2007 through February 28, 2008.

Subjects were deemed as having post-surgical C. difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) if they had a positive C. difficile toxin within 30 days after the surgical procedure and the presence of diarrhea documented in the inpatient chart. Subjects on the medical service were deemed as having CDAD if they had a positive C. difficile toxin and the presence of diarrhea documented in the inpatient chart. Diarrhea was recorded as present if physician or nursing notes documented diarrhea within 2 days of the positive toxin result. CDAD was deemed as community acquired if the positive toxin occurred within 48 hours of admission, as has been done previously.27

For both cohorts, data on patient age, race-ethnicity, gender, prior medication use, laboratory values, ICD-9 codes, prior admissions, re-admissions, and in-hospital mortality were extracted from a replicate of Montefiore's clinical information system using Clinical Looking Glass™ a quality improvement health care surveillance software (Emerging Health Information Technology, Yonkers, NY). The Charlson co-morbidity score, a risk adjustment tool used for research, that measures overall co-morbidity using ICD-9 diagnosis codes,28, 29 was calculated using information derived from Clinical Looking Glass. The data replicate is merged with the social security death registry each month, which allowed extraction of 30-day mortality rates after discharge. The Institutional Review Board of Montefiore Medical Center approved the study.

Outcome Variables

For the descriptive analysis of post-surgical CDAD, the main outcome variables were: presence of CDAD, and 90-day post-operative mortality. CDAD was analyzed as a dichotomous variable defined by the presence of a positive C. difficile toxin assay in the electronic medical record and diarrhea documented in the inpatient chart within 2 days of the positive toxin result and 30 days of surgery. Subjects with community acquired CDAD were excluded. 90-day post-operative mortality was analyzed as a time-to-event variable using the social security death registry to obtain the date of death.

For the analysis comparing post-surgical CDAD with medical CDAD, the main outcome variables were recurrence of CDAD and 90-day post-infection mortality. Recurrence was analyzed as a time-to-event variable defined by recurrence of symptoms and a second positive C. difficile toxin at least 15 days, but not more than 90 days, after the first positive toxin. 90-day post-infection mortality was analyzed as a time-to-event variable using the social security death registry to obtain the date of mortality.

Independent Variables

Independent covariates examined for each subject included: demographic characteristics (age, gender, race-ethnicity), albumin and white blood cell count at the time of CDAD diagnosis, the Charlson co-morbidity score, prior admissions to Montefiore Medical Center within 180 days, and prior use of antibiotics and proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs).

Prior exposure to antibiotics was analyzed as a dichotomous variable; a subject was coded as having been exposed to antibiotics if a dose of any systemic antibacterial agent was given during the 30 days prior to the surgical procedure (excluding antibiotics given as prophylaxis within two hours of surgery). Prior exposure to PPIs was analyzed as a dichotomous variable and coded as having been exposed if a dose of PPI (omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, or esomeprazole) was given during the 10 days prior to the surgical procedure.

The Charlson co-morbidity score was treated as a continuous variable and was used as a risk-adjustment covariate.

Statistical analysis

All patients with a qualifying abdominal procedure and those who had a positive C. difficile toxin assay and diarrhea were characterized using descriptive statistics of demographic data. Factors thought potentially associated with post-surgical CDAD were tested using bivariate logistic regression. Factors found to significantly associated with post-surgical CDAD were tested using multivariate logistic regression, after adjustment for patient age and Charlson co-morbidity score. To test whether there was heterogeneity in the associations between risk factors and CDAD across the two hospitals, regression models were constructed to test for interactions between factors, hospital and the development of CDAD.

Surgical patients with and without post-surgical CDAD were compared with respect to 90-day mortality using Kaplan-Meier methods. The independent association between post-surgical CDAD and mortality was assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model. To test whether there was heterogeneity in the association between CDAD and mortality risk across the two hospitals, a Cox proportional hazards model was constructed to test for interaction between CDAD, hospital and mortality.

Medical and surgical patients with post-surgical CDAD were compared using chi-squared, t-tests, or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests as appropriate for demographic and clinical characteristics, and using the Kaplan-Meier method for outcomes recurrence and 90-day post-infection mortality. Propensity score methods were used to match each surgical case of CDAD with 5 controls from the pool of medical CDAD using a non-parsimonious logistic regression model.30, 31 Variables included in the propensity score model were: age, sex, Charlson co-morbidity score, and community vs. hospital acquired infection. Then, for each post-surgical CDAD case, 5 propensity score matched controls were selected using a nearest neighbor greedy match protocol without replacement.32 To minimize matching bias, data were randomly sorted prior to matching.

Cases of post-surgical CDAD and matched controls with medical CDAD were compared with respect to 90-day recurrence and 90-day mortality using the method of Kaplan and Meier and log rank tests.

STATA software, version 10.0, (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Study population

From January 1, 2006 through February 28, 2008, there were 3904 patients at Montefiore Medical Center who underwent a qualifying surgical procedure (Table 1). 805 (20.6%) of the patients had had a prior hospitalization within the previous six months. 1042 (26.8%) patients had been exposed to pre-operative antibiotics and 391 (10.0%) had been exposed to pre-operative PPIs.

Table 1.

Description of Patient Population

| All Procedures (n = 3904) | Post-surgical CDAD (n = 46) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.9 ± 18.8 | 65.5 ± 15.7 |

| Male No. (%) | 1304 (33.4) | 12 (26.1) |

| Race/ethnicity No. (%) | ||

| White | 739 (18.9) | 13 (28.3) |

| Black | 1166 (29.9) | 14 (30.4) |

| Hispanic | 1609 (41.2) | 17 (37.0) |

| Other/Unknown | 388 (9.9) | 2 (4.3) |

| Antibiotics given* | 1042 (26.8) | 22 (47.8) |

| Cephalosporin† | 96 (2.5) | 4 (8.7) |

| Fluoroquinolone | 254 (6.5) | 12 (26.1) |

| Clindamycin | 37 (0.9) | 2 (4.3) |

| Imipenim | 42 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Proton-Pump Inhibitor given‡ | 391 (10.0) | 13 (28.3) |

| Prior Hospitalization§ | 805 (20.6) | 19 (41.3) |

| Admission Albumin | 3.69 ± 0.77 | 3.05 ± 0.90 |

| White Blood Cell Count | 11.5 ± 4.9 | 11.4 ± 5.7 |

| Charlson Score | 2.31 ± 2.57 | 3.74 ± 3.31 |

| Hospital | ||

| Moses Division Hospital | 2287 (58.6) | 31 (67.4) |

| Weiler Division Hospital | 1617 (41.4) | 15 (32.6) |

Continuous variables reported as mean ± standard deviation

Dichotomous variables reported as number (percent)

any antibacterial given within 30 days before surgical procedure

3rd or 4th generation cephalosporins: cefipime, ceftriaxone, cefpodoxime, cefota

any PPI given within 10 days before surgical procedure

any hospitalization within 180 days before surgical procedure

Post-surgical CDAD

46 patients (1.2%) had CDAD within 30 days after their operative procedure. Compared with all patients undergoing abdominal surgery, patients with post-surgical CDAD were older (mean 65.5 vs. 52.9 years, p < 0.001), more likely to have been given pre-operative antibiotics (47.8% vs. 26.8%, p < 0.001) and PPIs (28.3% vs. 10.0%, p < 0.001), and more likely to have had a prior hospitalization (41.3% vs. 20.6%, p < 0.001), and to have a lower mean albumin (3.05 vs. 3.69 g/dl, p < 0.001).

Pre-operative risk factors for post-surgical CDAD

Data on pre-operative factors associated with post-surgical CDAD are presented in Table 2. Significant pre-operative risk factors were age (OR: 1.46 for each 10-year increment in age; 95% CI: 1.24-1.73), antibiotic use within 30 days prior to surgery (OR: 2.54; 95% CI: 1.42-4.55), high-risk antibiotic use within 30 days prior to surgery (OR: 4.80; 95% CI: 2.57-8.98), proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) use within 10 days prior to surgery (OR: 3.62; 95% CI: 1.89-6.95), prior hospitalization (OR: 2.75; 95% CI: 1.52-4.97), and low serum albumin level on admission (OR: 2.51 for each loss of 1 g/dl, 95% CI: 1.70-3.71).

Table 2.

Pre-Operative Factors Associated with Post-operative Toxin Positivity on Bivariate Analysis

| Bivariate Analysis | Adjusted Analysis* | |

|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | |

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |

| p-value | p-value | |

| Age† | 1.46 | |

| (1.24 - 1.73) | ||

| <0.001 | ||

| Pre-operative Abx‡ | 2.54 | 1.94 |

| (1.42 - 4.55) | (1.07 - 3.52) | |

| 0.002 | 0.03 | |

| High-risk Abx§ | 4.80 | 3.42 |

| (2.57 - 8.98) | (1.80 - 6.50) | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Pre-operative PPI∥ | 3.62 | 2.32 |

| (1.89 - 6.95) | (1.18 - 4.58) | |

| <0.001 | 0.01 | |

| Prior Hospitalization | 2.75 | 2.27 |

| (1.52 - 4.97) | (1.30 - 3.96) | |

| 0.001 | 0.004 | |

| Low Albumin¶ | 2.51 | 2.05 |

| (1.70 - 3.71) | (1.29 - 3.25) | |

| <0.001 | 0.002 |

Adjusted for age and Charlson co-morbidity score

Odds ratio for each 10-year increment in age

Any antibiotic given within 30 days prior to the procedure

Cephalosporin (3rd & 4th generation), flouroquinolones, clindamycin, imipenim

Proton pump inhibitor given within 10 days prior to the procedure

Odds ratio for each loss of 1 g/dl

After adjustment for age and Charlson co-morbidity score, factors significantly associated with post-surgical CDAD were: antibiotic use (OR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.07-3.52), high-risk antibiotic use (OR: 3.42; 95% CI: 1.80-6.50), PPI use (OR: 2.32; 95% CI: 1.18-4.58), prior hospitalization (OR: 2.27; 95% CI: 1.30-3.96), and low serum albumin (OR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.29-3.25). Hospital site did not significantly affect the association between pre-operative risk factors and the development of post-operative CDAD (all p-values for interaction = ns).

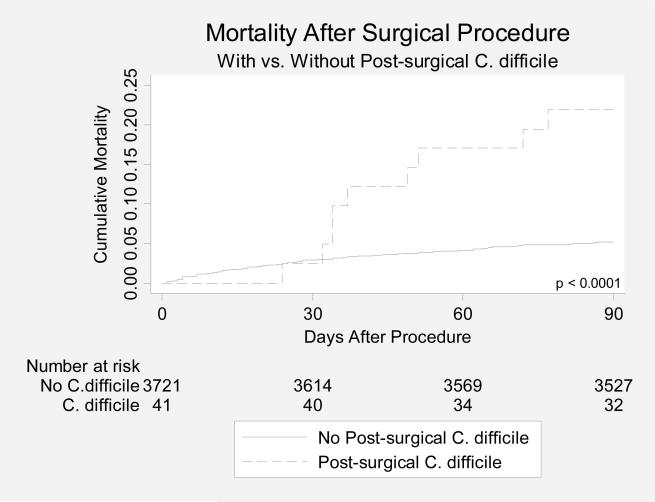

Post-operative Mortality

Post-surgical patients with CDAD had a significantly increased 90-day mortality (p < 0.0001, Figure 1.) on bivariate analysis, compared with post-surgical patients without CDAD; after adjustment for age, albumin value, creatinine value, Charlson comorbidity score, and prior hospitalizations, however, post-surgical CDAD was not associated with increased risk of mortality (HR: 1.30; 95% CI: 0.64-2.66), compared with post-surgical patients without CDAD. Hospital site did not significantly affect the association between CDAD and mortality (p for interaction = 0.99).

Figure 1.

Post-surgical vs. Medical CDAD

In comparison with medical patients with CDAD, post-surgical patients with CDAD were significantly more likely to have received antibiotics (98.0% vs. 85.2%; p=0.01), less likely to have received a PPI (38.8% vs. 58.3%; p=0.009), and less likely to have had a prior hospitalization (42.9% vs. 67.1%; p=0.001). Medical patients were more likely to have received a high-risk cephalosporin (30.3% vs. 18.4%), but the difference was not significant (p = 0.08). (Table 3.)

Table 3.

Comparison of CDAD in Medical vs. Post-Surgical Patients

| Medical CDAD (n = 432) | Post-Surgical CDAD (n = 49) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 67.9 ± 17.1 | 64.4 ± 15.8 | 0.09 |

| Male | 162 (37.5) | 12 (24.5) | 0.07 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.89 | ||

| White | 121 (28.0) | 14 (28.6) | 0.93 |

| Black | 142 (32.9) | 15 (30.6) | 0.75 |

| Hispanic | 142 (32.9) | 18 (36.7) | 0.59 |

| Other/Unknown | 27 (6.2) | 2 (4.1) | 0.55 |

| Any antibiotic given* | 368 (85.2) | 48 (98.0) | 0.01 |

| Cephalosporin† | 131 (30.3) | 9 (18.4) | 0.08 |

| Quinolone | 196 (45.4) | 21 (42.9) | 0.74 |

| Clindamycin | 10 (2.3) | 3 (6.1) | 0.12 |

| Imipenim | 29 (6.7) | 5 (10.2) | 0.37 |

| Proton-Pump Inhibitor given‡ | 252 (58.3) | 19 (38.8) | 0.009 |

| Prior Hospitalization§ | 290 (67.1) | 21 (42.9) | 0.001 |

| Admission Albumin | 2.72 ± 0.71 | 2.66 ± 0.70 | 0.69 |

| White Blood Cell Count∥ | 15.7 ± 14.2 | 14.5 ± 5.4 | 0.49 |

| Charlson Score | 3.13 ± 2.48 | 3.63 ± 3.25 | 0.54 |

| Community Aquired¶ | 162 (37.5) | 3 (6.1) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital | 0.47 | ||

| Moses Division Hospital | 268 (62.0) | 33 (67.3) | |

| Weiler Division Hospital | 164 (38.0) | 16 (32.7) |

Continuous variables reported as mean ± standard deviation and compared using a t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate

Dichotomous variables reported as number (percent) and compared using a chi-squared test

any antibacterial given within 30 days before diagnosis of CDAD

3rd or 4th generation cephalosporins: cefipime, ceftriaxone, cefpodoxime, cefotaxime

any PPI given within 10 days before diagnosis of CDAD

any previous hospitalization within 180 days before diagnosis of CDAD

measured at the time of CDAD diagnosis

infection discovered within 48hrs of admission

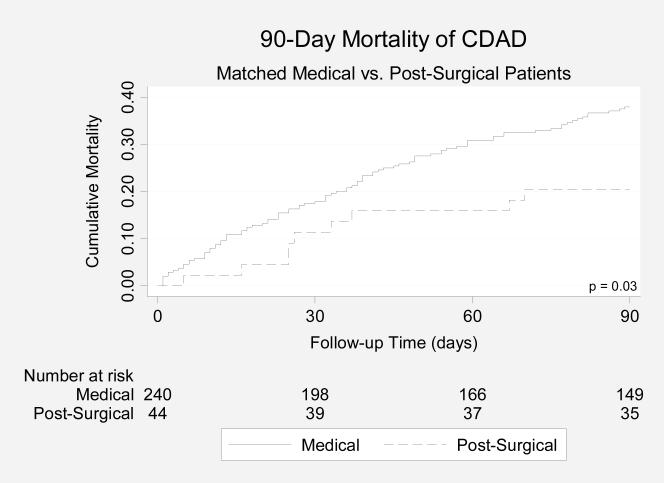

Compared with medical patients with CDAD, patients with post-surgical CDAD had a significantly lower 90-day mortality rate (19.0% vs. 36.2%; p=0.009; Figure 2A). After adjustment for age, albumin, antibiotics, and Charlson score, post-surgical CDAD was independently associated with lower mortality compared with medical CDAD (HR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.15-0.83).

Figure 2A.

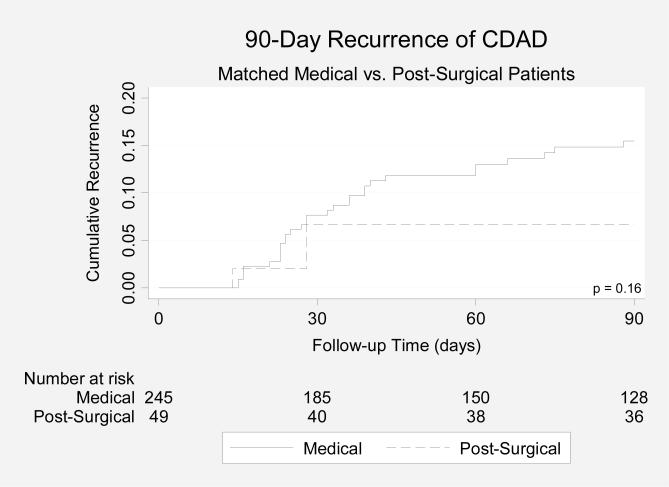

Compared with medical patients with CDAD, patients with post-surgical CDAD had a lower 90-day recurrence rate (6.2% vs. 12.6%), but the difference was not significant (p = 0.14, Figure 2B).

Figure 2B.

Discussion

The 30-day incidence of post-surgical CDAD in our study (1.2%) is similar to what has been reported previously. We found, however, that risk for developing post-surgical CDAD was increased with exposure to pre-operative antibiotics and PPIs, having a prior hospitalization, and having a low albumin level at the time of the procedure. The association between antibiotics and post-surgical CDAD is particularly strong for the high-risk antibiotics we examined: 3rd and 4th-generation cephalosporins, flouroquinolones, clindamycin, and imipenim/meropenim.

Given the increased risk of post-surgical CDAD associated with antibiotic use, unnecessary use of high-risk antibiotics before surgery should be avoided. In our analysis, we did not consider antibiotics given within two hours of the procedure. This prophylactic dose given immediately before surgery is associated with dramatically reduced rates of wound infection and post-operative sepsis.33, 34 It is likely that any increased risk of post-operative CDAD associated with such prophylactic use of antibiotics would be outweighed by benefit.

PPI use also was associated with increased risk for post-surgical CDAD, possibly by allowing C. difficile spores safe transit through the hypochlorhydric stomach of patients treated with these agents. Pre-operative PPIs are used for prophylaxis against stress-related mucosal damage which is common post-operatively,35 and preventable.36 It is likely that the benefit of pre-operative PPIs outweighs their potential risk for CDAD.

We have found an association between low albumin and increased risk of post-surgical CDAD. It is possible that low albumin, associated with chronic disease, is a marker for poor immune function. Poor anti-toxin IgA antibody response has been associated with increased risk of recurrence after an episode of CDAD,37 and immunosuppression has been associated with the development of CDAD,38, 39 thus low albumin may be associated with CDAD through poor immune function. Postoperative impairment of cell-mediated immunity is another potential risk factor for CDAD which may last up to days after surgery.40

In previous studies, the lowest reported rates of post-surgical CDAD were in patients undergoing cardiovascular procedures (0.2%-1.2%);8, 12, 13 moderate rates were observed in populations that included general surgery procedures (2.0%-5.6%);7, 10 and the highest rate was reported in patients undergoing aortic procedures (8.4%).11 Our patient population all had surgical procedures that entered the abdominal cavity, and the rate of post-surgical CDAD that we observed (1.2%) is in the low range; we found no evidence that entering the abdominal cavity increases the incidence of post-surgical CDAD. We suspect that the differences in rates reported above reflect the underlying differences in patient risks and exposures, rather than variable risk associated with specific procedures.

We found that post-surgical CDAD differs from CDAD on the medical service in several respects. Post-surgical CDAD is more commonly associated with antibiotic use, and less commonly associated with PPI use and prior hospitalization. In addition, post-surgical CDAD may have a better prognosis that medical CDAD.

Despite the strengths of our study, it does have some limitations. Our definition of CDAD included only patients with diarrhea in whom a C. difficile toxin assay was positive. Whether there were additional patients with CDAD who were treated empirically without a positive toxin assay, or were diagnosed by the presence of toxic megacolon, or by endoscopy, is unclear, and it is possible that we have underestimated the true incidence of post-surgical CDAD. We were unable to stratify our analysis by specific operation performed, and so it is unclear if specific surgical procedures are associated with increased or decreased risk for developing post-surgical CDAD.

In summary, CDAD infrequently complicates abdominal surgery. We have been able to describe several potentially avoidable pre-operative exposures (e.g. antibiotic and PPI use) that increase the risk of post-surgical CDAD. It appears that post-surgical CDAD is a disease that is different from CDAD on the medical service, with different exposure profiles and better outcomes.

Appendix 2.

Comparison of Matched Cohorts

| Medical CDAD (n = 245) | Post-Surgical CDAD (n = 49) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.0 ± 17.3 | 64.4 ± 15.8 | 0.80 |

| Male | 78 (31.8) | 12 (24.5) | 0.31 |

| Charlson Score | 3.46 ± 2.55 | 3.63 ± 3.25 | 0.86 |

| Community Acquired | 15 (6.1) | 3 (6.1) | 1.00 |

Continuous variables reported as mean ± standard deviation and compared using a t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate

Dichotomous variables reported as number (percent) and compared using a chi-squared test

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The Institute for Medical Effectiveness Research, a joint project of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the North Shore-LIJ Health System, the Clinical Investigation Core of the Center for AIDS Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH P30 AI51519), and the Montefiore Mentored Health Services Research Career Development Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Portions of this research were presented at The American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting, October, 2007, Philadelphia, PA.

Reference List

- 1.Gerding DN. Disease associated with Clostridium difficile infection. Ann Intern Med. 1989 February 15;110(4):255–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-4-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald LK, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Secular trends in hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile disease in the United States, 1987-2001. J Infect Dis. 2004 May 1;189(9):1585–9. doi: 10.1086/383045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redelings MD, Sorvillo F, Mascola L. Increase in Clostridium difficile-related mortality rates, United States, 1999-2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 September;13(9):1417–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.061116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermsen JL, Dobrescu C, Kudsk KA. Clostridium difficile infection: a surgical disease in evolution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 September;12(9):1512–7. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricciardi R, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD, Baxter NN. Increasing prevalence and severity of Clostridium difficile colitis in hospitalized patients in the United States. Arch Surg. 2007 July;142(7):624–31. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.7.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Kollef MH. Increase in adult Clostridium difficile-related hospitalizations and case-fatality rate, United States, 2000-2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 June;14(6):929–31. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.071447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent KC, Rubin MS, Wroblewski L, Hanff PA, Silen W. The impact of Clostridium difficile on a surgical service: a prospective study of 374 patients. Ann Surg. 1998 February;227(2):296–301. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199802000-00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harbarth S, Samore MH, Carmeli Y. Antibiotic prophylaxis and the risk of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea. J Hosp Infect. 2001 June;48(2):93–7. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2001.0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wren SM, Ahmed N, Jamal A, Safadi BY. Preoperative oral antibiotics in colorectal surgery increase the rate of Clostridium difficile colitis. Arch Surg. 2005 August;140(8):752–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarter MD, Abularrage C, Velasco FT, Davis JM, Daly JM. Diarrhea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea on a surgical service. Arch Surg. 1996 December;131(12):1333–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430240087012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulstrode NW, Bradbury AW, Barrett S, et al. Clostridium difficile colitis after aortic surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1997 September;14(3):217–20. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(97)80195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crabtree T, Aitchison D, Meyers BF, et al. Clostridium difficile in cardiac surgery: risk factors and impact on postoperative outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007 April;83(4):1396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geroulanos S, Donfried B, Schumacher F, Turina M. Cefuroxime versus ceftriaxone prophylaxis in cardiovascular surgery. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1985;11(3):201–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronsson B, Mollby R, Nord CE. Antimicrobial agents and Clostridium difficile in acute enteric disease: epidemiological data from Sweden, 1980-1982. J Infect Dis. 1985 March;151(3):476–81. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wistrom J, Norrby SR, Myhre EB, et al. Frequency of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in 2462 antibiotic-treated hospitalized patients: a prospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001 January;47(1):43–50. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlstrom O, Fryklund B, Tullus K, Burman LG. A prospective nationwide study of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in Sweden. The Swedish C. difficile Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1998 January;26(1):141–5. doi: 10.1086/516277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pepin J, Valiquette L, Cossette B. Mortality attributable to nosocomial Clostridium difficile-associated disease during an epidemic caused by a hypervirulent strain in Quebec. CMAJ. 2005 October 25;173(9):1037–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marra AR, Edmond MB, Wenzel RP, Bearman GM. Hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease in the intensive care unit setting: epidemiology, clinical course and outcome. BMC Infect Dis. 2007 May 21;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-42. 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyne L, Sougioultzis S, McFarland LV, Kelly CP. Underlying disease severity as a major risk factor for nosocomial Clostridium difficile diarrhea. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002 November;23(11):653–9. doi: 10.1086/501989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dial S, Delaney JA, Barkun AN, Suissa S. Use of gastric acid-suppressive agents and the risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease. JAMA. 2005 December 21;294(23):2989–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dial S, Delaney JA, Schneider V, Suissa S. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of community-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated disease defined by prescription for oral vancomycin therapy. CMAJ. 2006 September 26;175(7):745–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aseeri M, Schroeder T, Kramer J, Zackula R. Gastric acid suppression by proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 September;103(9):2308–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price MF, Dao-Tran T, Garey KW, et al. Epidemiology and incidence of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea diagnosed upon admission to a university hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2007 January;65(1):42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bliss DZ, Johnson S, Savik K, Clabots CR, Willard K, Gerding DN. Acquisition of Clostridium difficile and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients receiving tube feeding. Ann Intern Med. 1998 December 15;129(12):1012–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamthan AG, Bruckner HW, Hirschman SZ, Agus SG. Clostridium difficile diarrhea induced by cancer chemotherapy. Arch Intern Med. 1992 August;152(8):1715–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dubberke ER, Butler AM, Reske KA, et al. Attributable outcomes of endemic Clostridium difficile-associated disease in nonsurgical patients. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 July;14(7):1031–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1407.070867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Issa M, Vijayapal A, Graham MB, et al. Impact of Clostridium difficile on inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 March;5(3):345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992 June;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998 October 15;17(19):2265–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Agostino RB, Jr., D'Agostino RB., Sr Estimating treatment effects using observational data. JAMA. 2007 January 17;297(3):314–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching [computer program] Boston College School of Economics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke JS, Condon RE, Bartlett JG, Gorbach SL, Nichols RL, Ochi S. Preoperative oral antibiotics reduce septic complications of colon operations: results of prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical study. Ann Surg. 1977 September;186(3):251–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197709000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis RT. Oral versus systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in elective colon surgery: a randomized study and meta-analysis send a message from the 1990s. Can J Surg. 2002 June;45(3):173–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin LF. Stress ulcers are common after aortic surgery. Endoscopic evaluation of prophylactic therapy. Am Surg. 1994 March;60(3):169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spirt MJ. Stress-related mucosal disease: risk factors and prophylactic therapy. Clin Ther. 2004 February;26(2):197–213. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP. Association between antibody response to toxin A and protection against recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Lancet. 2001 January;357(9251):189–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03592-3. %20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Svenungsson B, Burman LG, Jalakas-Pornull K, Lagergren A, Struwe J, Akerlund T. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of Clostridium difficile strains from patients with diarrhea: low disease incidence and evidence of limited cross-infection in a Swedish teaching hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 2003 September;41(9):4031–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4031-4037.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West M, Pirenne J, Chavers B, et al. Clostridium difficile colitis after kidney and kidney-pancreas transplantation. Clin Transplant. 1999 August;13(4):318–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammer JH, Nielsen HJ, Moesgaard F, Kehlet H. Duration of postoperative immunosuppression assessed by repeated delayed type hypersensitivity skin tests. Eur Surg Res. 1992;24(3):133–7. doi: 10.1159/000129199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]