Abstract

This study examined the challenges faced by family members at the end of life in different care settings and how those challenges compare across settings. A total of 30 participants, who had a family member die in inpatient hospice, a skilled nursing facility or a community support program were interviewed. Semi-structured interviews were recorded and transcribed. Text was coded using qualitative thematic analysis. Themes were determined by consensus. Twelve challenges were identified across care sites. Two themes emerged in all three settings: bearing witness and the experience of loss. The study findings contribute to our knowledge of family perceptions of care in different settings and raises awareness of the need for further research describing the experiences at the end of life in different settings and the importance of creating and testing interventions for both setting specific needs and universal issues.

Keywords: Family caregiver, terminal care, settings

Background

Understanding the needs and experiences of family members at the end of life across service settings is part of the national agenda for social work research in palliative and end-of-life care (Kramer, Christ, Bern-Klug, & Francoeur, 2005). Family members are often intimately involved in the care of individuals and face numerous challenges and difficulties at the end of the patient's life. These challenges are related not only to the emotional response to the dying process and the demands of the caregiving role, but also to unmet needs in service delivery systems (Aoun, Kristjanson, & Oldham, 2006; Aoun, Kristjanson, Currow, & Hudson, 2005; Jo, Brazil, Lohfield, & Willison, 2007; Kristjanson, Walton, & Toye, 2005). Most investigators have examined challenges facing family members in one setting, but a few have compared the similarities and differences in challenges across settings. Examining the experiences of family members in different settings may provide better understanding of the breadth of issues that challenge families at the end of life and identify potential targets for interventions that may better meet family needs. It is possible that planning for education and training of health care staff which is appropriate to both the population and the setting could be facilitated.

Several studies have sought to understand the experiences and preferences of family members at the end of life and offer insights about their needs and perceptions regarding quality of care (Baer & Hanson, 2000; Hebert, Schulz, Copeland, & Arnold, 2009; Jo, Brazil, Lohfield, & Willison, 2007; Keegan, et al., 2001; King, Bell, & Thomas, 2004; Milberg, Strang, Carlsson, & Borjesson, 2003; Perreault, Fothergill-Bourbonnais, & Fiset, 2004; Pierce, 1999; Proot, et al., 2003; Rogers, Karlsen, & Addington-Hall, 2000; Stajduhar, 2003; Steinhauser, Christakis, et al., 2000; Steinhauser, Clipp, et al., 2000; Teno, et al., 2004; Thompson, Menec, Chochinov, & McClement, 2008; Waldrop, Kramer, Skretny, Milch, & Finn, 2005; Wilson & Daley, 1999). Family members are often challenged by the emotional feelings of helplessness associated with the progression of the illness (Andershed, 2006; Perreault, Fothergill-Bourbonnais, & Fiset, 2004), the difficulties of bearing witness to the changes (Kruse, 2004) and the acceptance of the reality of death or comprehension of death (Andershed, 2006; Perreault et al., 2004). Family members express the universal need for quality care for the patient and the desire to have complete confidence that the patient's needs will be met (Andershed, 2006; Aoun et al., 2005; Keegan et al., 2001; Milberg, Strang, Carlsson, & Borjesson, 2003; Weitzner, McMillan, & Jacobsen, 1999). Family members express fundamental needs including good communication between the family and the healthcare team (Aoun et al., 2005; Broback & Bertero, 2003; Keegan et al., 2001; King, Bell, & Thomas, 2004; Pierce, 1999; Rogers, Karlsen, & Addington-Hall, 2000; Rose, 1999), respect for the patient (Andershed, 2006; Rogers et al., 2000), and the desire to be present at the time of death (Andershed, 2006; Andershed & Ternestedt, 1999; Perreault et al., 2004; Pierce, 1999; Wilson & Daley, 1999).

Other investigations of family member's experiences and challenges in distinctive settings of care have revealed a number of challenges in these settings that may or may not be shared across care sites. Studies in the home setting have shown that family members have feelings of uncertainty (Broback & Bertero, 2003) and the task of balancing burden and capacity (Andershed, 2006; Proot et al., 2003), which is tempered by the family members' love for the patient (Andershed, 2006; Grbich, Parker, & Maddocks, 2001). Studies in the home setting have also revealed that caregivers are challenged by caregiving tasks (Andershed, 2006; Stajduhar, 2003) and adjusting to the caregiver role (Broback & Bertero, 2003). In the hospital, families have identified challenges with getting patient needs met such as personal care or hygiene and dissatisfaction with the environment (Rogers et al., 2000). A growing body of research shows that family members are often more satisfied with both the physical and the emotional/spiritual care when hospice is involved especially in the skilled nursing facility setting (Andershed, 2006; Baer & Hanson, 2000; Teno, Clarridge et al., 2004). Because these studies set out to answer different research questions and employ different methods to do so, it is difficult to know how universal or distinctive these challenges might be.

Studies examining perceptions of patients, families and healthcare providers concerning quality of dying across settings have delineated the differences in perceptions of patients, families, physicians and other caregivers, and drew attention to the necessity of “attending to aspects of care that are not intuitively important to clinicians but are critical to patients and their families” (Steinhauser, Christakis et al., 2000, p. 2481). Steinhauser and others (Steinhauser, Christakis et al., 2000; Steinhauser, Clipp et al., 2000) conducted two studies across settings including a university medical center, a Veterans' Administration medical center and a community hospice. There was agreement between all groups that basic hygiene, being comfortable with and trusting the healthcare team, knowing what to expect about the patient's physical condition, good communication, symptom relief, and presence of family are important. It is notable that although there was agreement on the importance of 26 of the 44 items identified, there was disagreement between groups on 41% of the items.

There has been little research examining family perceptions of care in the inpatient hospice setting despite the recent threefold increase in percentage of hospice patients receiving inpatient care (Han, Remsburg, McAuley, Keay, & Travis, 2006). Most hospice patients receiving inpatient care are found in skilled nursing facilities or hospitals (Han et al., 2006). But there is a growing interest in free-standing hospices and more hospice agencies are building separate hospice inpatient facilities (Long, 2008).

While prior research has illuminated understanding of differential perceptions of families and professionals regarding the family member's experiences and insights regarding quality of care and attributes of a good death, additional research is needed to understand the similar and distinctive challenges at the end of life faced by families in different settings. The current study uses qualitative methods to describe the challenges experienced by family members of persons receiving care at the end of life in three settings. This study was guided by two primary research questions, “What are the challenges faced by family members at the end of life in different care settings?” and “How do these challenges compare across settings?”

Methods

Design and Sample

This exploratory, retrospective and descriptive study involved family members of individuals who had died in one of three settings. References to the “setting” reflect the program of care in which the dying person was cared for: an inpatient hospice facility (IHF), a skilled nursing facility (SNF), and a non-profit fully integrated managed care community support program (CSP) for older adults. All programs were in a Midwestern city. The inpatient hospice sample included patients who chose care in a free-standing inpatient hospice facility. None had been previously enrolled in hospice in their homes. Most individuals dying in inpatient hospice have been transferred directly from a hospital or skilled care facility because they need assistance with pain and symptom management and they have a very short prognosis. The SNF provided standard skilled nursing care. They were not affiliated with a hospice or palliative care program at the time of the study. The CSP provides interdisciplinary community-based healthcare and long-term support to individuals receiving Medicare and Medicaid, who are eligible for skilled nursing care. The primary goal of the program is to promote independence and quality of life and most people live at home while receiving services, although they may transfer to assisted living, skilled care, or a hospital, if needed. Many CSP participants have family members who serve as caregivers. None of the participants from the CSP were receiving home hospice services. For a more complete description of the CSP setting, please refer to Kramer & Auer (2005).

A total of 30 family members of individuals who died in one of the above settings in the previous six to twelve months were interviewed using semi-structured questions from the Family Interview Guide. The dying individuals had been present in the setting of their death for at least 48 hours before death. The target population included family members who were identified as “next of kin” or “primary caregiver” in the medical records of the agency providing care to the deceased. Participants were required to speak English and be at least 18 years of age.

Procedure

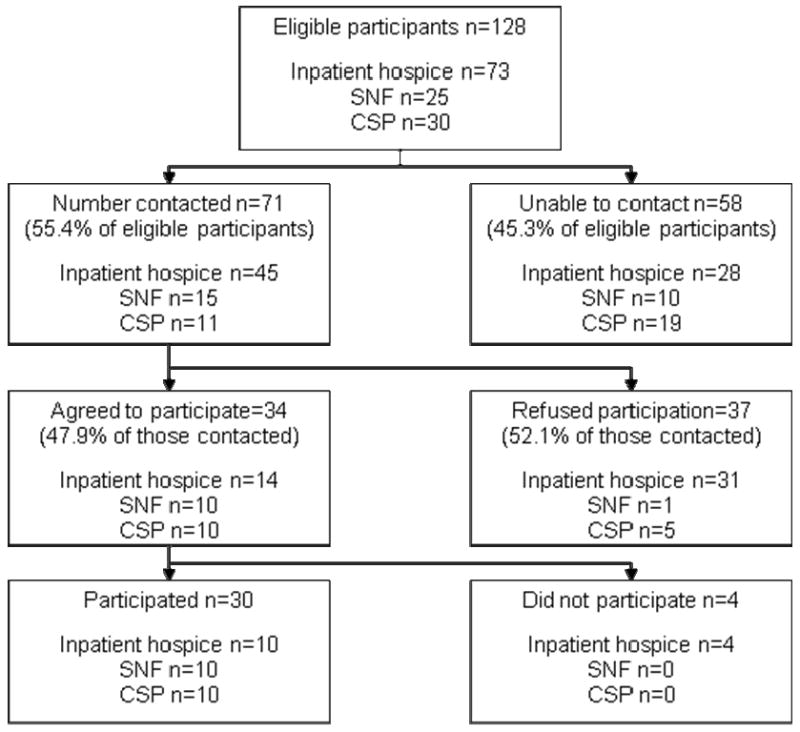

Family members of individuals from each organization who had died six to 12 months before the study began were sent letters providing information about the study and were instructed to contact the agency if they did not want their name and phone number given to the researchers. Researchers received lists of names and phone numbers of all of the eligible individuals since none opted out. A total of 128 eligible participants were on the list; 73 from the inpatient hospice facility, 25 from the CSP and 30 from the SNF (see Figure 1). This list was put into random order using a random number generator and potential participants were contacted in numeric random order by telephone and given information on the study. If a participant was not contacted, a message was left if they had an answering machine or if someone else answered. At least three attempts were made to reach each potential participant. The first ten from each site who agreed to participate were scheduled for a telephone or in person interview, and chose their preferred setting for the interview (i.e., their own home, private room in library, research office, and agency offices).

Figure 1.

Details of recruitment by site

The interviews of inpatient hospice family members were conducted by author K.A.K. and the interviews of SNF and CSP were conducted by author C.H.S. Both were trained by author K.T.K. and the audiotapes of first interviews conducted by each were reviewed by K.T.K. with the interviewer to assure consistency. Interviews lasted from 45 to 90 minutes. Respondents were invited to share information about how the care receiver came to enroll in the program and to share their experiences regarding the quality of care provided during the last week of the care receiver's life using the Family Interview Guide. The Family Interview Guide contains 16 open-ended questions and was developed by the researchers to explore the experience of family members at the final place of care across a number of settings. The guide was piloted with individuals who experience the death of a loved one in the previous year. This paper focuses on their response to four questions: “What were the hardest things for you? What things were easier than you expected? What things surprised you? If you could change anything, what would it be?” Other questions in the Family Interview Guide focused on family suggestions for doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals caring for dying individuals and their families.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Each interview was transcribed and reviewed by one of the investigators for accuracy. The text of the transcribed responses of the Family Interview Guide was read by all investigators several times to obtain an overall understanding. We followed a three-step approach to qualitative thematic analysis and code development frequently employed in qualitative research (Boyatzis, 1998). Codes were not developed a priori, but were generated by each researcher independently and inductively. Each researcher reviewed the transcripts at least three times and coded the findings independently employing an initial line by line open coding of the transcripts. Three of the researchers met to discuss coding and to come to consensus on the codes for each question and response. There was an 88% agreement between the three researchers. Differences in coding were usually related to semantics, not concepts and these differences were resolved by consensus. Consensus was reached in all instances. Themes were identified from repeated readings of the transcripts and the preliminary codes. This process yielded key words and themes that formed initial codes. Next, we clustered the codes into families of categories. Finally, we developed and refined themes to represent broader conceptual categories and the clusters of codes (Coffey & Atkinson, 1996). There was no disagreement between researchers concerning categories or themes. Cross case interpretative summaries were prepared for each setting, and then the summaries were analyzed for common meanings and themes. After a summary of findings was completed, the researchers returned to the original texts to verify that the themes were accurate to the original text and context. We reached a point of data saturation whereby no additional codes emerged (Drisko, 1997; Patton, 2002).

Ways of Addressing Trustworthiness

A variety of strategies were employed to ensure trustworthiness. Each transcript was verified for accuracy. Strategies for enhancing analytic rigor included peer debriefing and a co-coding process involving ongoing comparative analysis and discussion and inter-subjective agreement between the researchers; auditing that involved careful documentation of the process followed in the development of codes, memos, and analytic decisions (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Padgett, 1998).

Results and Discussion

Participants

Thirty participants, ten from each setting, were interviewed. A large number of eligible participants were unreachable (See figure 1). Of the 58 who were not reached, at least three attempts were made to reach each one: one of the family members died, 22 did not answer the phone and had no answering machine, 14 did not respond to messages left on an answering machine, and 18 had the phone disconnected or the number had changed and the new number was not available. Four inpatient hospice family members agreed to participate but did not show for their appointments, even when the interview was to take place in the participant's home. The demographic characteristics of the persons interviewed are reported in Table 1. Similar to the demographic characteristics reported in national estimates of persons involved in providing care for others (Marks, 1996; Stone, Cafferata, & Sangl, 1987), the majority of respondents were female, and either spouses or adult children across all service settings. While slightly more were adult children of the deceased in the IHF and CSP, there were equal numbers of children, spouses, and other relatives from the SNF. Most were Caucasian, and respondents' mean age ranged from 60 in the IHF family member group to about 64 in the CSP and approximately 70 in the SNF.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Family Member | IHF n=10 |

CSP n=10 |

SNF n=10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean | 60.29 | 63.67 | 69.78 |

| Range | 30-73 | 36-84 | 58-87 |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| Male | 2 | 3 | 2 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White, not Hispanic | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Black | 1 | 1 | |

| Relationship to patient | |||

| Spouse or partner | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Child | 4 | 6 | 3 |

| Friend | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sibling | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other relative | 2 | 0 | 3 |

The patients whose family members participated in this study shared some similarities and some differences. The majority of the care recipients across all settings were female and approximately one-half of them were married at the time of death, with the exception of the SNF care recipients, of whom only 4 were married. CSP care recipients were the oldest with an average age of 86, compared to a mean age of 74 and 82 in the IHF and the SNF respectively.

Findings

There were a total of 12 primary challenges identified in this study. As shown in Table 2, two of these challenges were reported by family members across the three care settings and others were distinctive to one or two sites. Table 2 outlines the themes and illustrates them with quotes from family members. Of the three settings, a wider range of challenges were reported for the SNF (n = 9) as compared to the other two programs. We first describe and provide examples of the challenges in common across settings and then differentiate setting specific challenges.

Table 2.

Common and Distinctive Challenges

| CHALLENGES | Inpatient Hospice Facility | Skilled Nursing Facility | Community Support Program |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bearing Witness | To helplessness. “To see that and know that you could do nothing for him…All he could do is move this arm and he'd get so frustrated and hit the bed. That's all he could do and you couldn't do anything for him.” IHF family member #1 | To suffering. [What was hardest was] “The fact that she had a catastrophic illness and she underwent a number of esophageal dilations that were distressful for her and we knew that she wasn't going to be able to survive that.” NH family member #5 | To decline. “I think the hardest thing was watching him go downhill…I think the worst was when he called me at work one day and said ‘I can't see. Everything is a blur.’” CSP family member #10 |

| Experience of Loss | “I think trying to be alone at night was the hardest thing at first. I don't think I'll ever get used to staying at home completely, but other women have done it…But I think that was the hardest part at first.” IHF family member #1 | “The most difficult thing for me, the whole thing was first triggered by the untimely and unexpected passing of my sister [not the patient]…and then realizing my mother's life was coming to an end.” SNF Family Member #6 | “Understanding the mental capacity and limitations when they're not your parents anymore is difficult 'cuz they just aren't the same.” CSP family member #2 |

| Unmet Patient Needs and Wishes | “They were, they were helpful to an extent, but they knew that they could not kill him. That's what he asked for, to be killed. And his personal physician who was also a good friend of his and me, was, told him right out, ‘If I do this, I will be in jail.’ And so he knew it and I knew it and so he couldn't do very much. It's, it's handicapped. It's, it's a horrible law.”IHF family member #10 | “The only contact I got with his doctor was two days before he died when I pleaded with him to do something because they told me he was throwing up blood at the nursing home when I came that day. And so I tried getting a hold of the doctor immediately…he didn't call me until 5-6:00 that night and I'm sitting here frustrated all day. This man is throwing up blood! There must be something seriously wrong. He should be getting some medical attention… I still haven't accepted this; I still wake up with nightmares about it” SNF family member #1 | |

| Reality of Death | [What was hardest was] “Knowing the time had come. That she had pretty much made up her mind that she was not going to cooperate with life any longer. That she was giving up…she had always been a fighter, always been a survivor, she had a lot of things that she overcame through her life. But she did give up with her blindness; that was the start of it. And this was the final straw to see, and to know that she was going to die.” IFH family member #6 | “…the most difficult thing for me the whole thing was … realizing my mother's life was coming to an end and it was simply adjusting to that…it was emotionally upsetting in a way that I don't even think I was realizing at the time”. SNF family member #6 | |

| Final Communications Between Patient & Family | “To me it was extremely frustrating that I could not converse with him. He could not express himself. ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ questions were somewhat helpful but not always. And it was a time when we should have touched, we should have had possibilities to really say things we wanted to say and we couldn't and that was the very hardest.” IHF family member #10 | “Later he tried to tell me something but his speech was so slurred that I just sat and held his hand. I couldn't understand what he was saying. I said ‘Um hm’, instead of saying I didn't know what he said…that was the hardest point right there.” SNF Family member #9 | |

| Placement Related Regrets | “I think I would have brought her here a little earlier. If there could have been a way, and of course at the time we didn't know this, had we known how fast things were going to change…for all of us, to kind of ease into the acceptance, again with the help that was offered to us here.” IHF family member #2 | “I often felt that I should have just kept him at home or maybe he should have gone to hospice instead of a nursing home. That was hardest, besides losing him, you know.” SNF family member #7 | |

| Uncertainty | “I think the hard part was that I wasn't sure, and I'm still not, was she in a lot of pain that there was this much medication? I don't understand. She was so good and then so bad…that's still a little fuzzy in my head.” IHF family member #2 | “She'd get bad and then she'd get better and she'd get bad and get better, and so I don't know if that was harder, but it was not within my experience, so you never knew exactly what to expect…and she was my mother so it was very hard period.” CSP family member #4 | |

| Fulfilling Obligations Surrounding Death | “The actual physical labor of cleaning out his apartment, arranging his affairs was quite difficult. He had not kept things in a very orderly manner for at least a year, so it was amazing how much stuff there was to pack. I still have some actually, nearly a year later. So that was, that was very hard, but it was kind of like while you were doing that at least you weren't just worrying.” IHF family member #9 | ||

| Caregiving Tasks and Responsibilities | “Sometimes she'd get up to try to go to the bathroom while I was asleep and then she'd fall on the floor and I'd have to get up and get her up and I'd have to change the bed. It wound up that I was up all night practically all night every night with her and finally, I wasn't young myself at this point and I was starting to get worn out.” CSP family member #7. | ||

| Absence of Trust in Care Providers | “The hardest thing probably was just watching her and hoping that things were going well. That's in the back of your mind all of the time… [if] she was being taken care of and she wasn't suffering.” SNF family member #3 | ||

| Personal Belongings Compromised | “she lost money on a number of occasions…one time it was $300…they didn't keep a record of what she had.” | ||

| Insufficiencies in Communication with Staff | “I did not get any information about his medications, his health situation or anything.” SNF family member #1 |

Challenges in Common across Settings

There were two primary themes that emerged as challenges in all three settings: Bearing witness and experience of loss. These challenges are related to the universal human experience of death and dying and the individual's response to it.

Bearing witness

We came to understand from family members in all settings, that bearing witness, which includes being an observer to the experience of the dying person, was especially difficult. Family members shared examples of bearing witness to the patient's helplessness, cognitive and physical decline, suffering, final good-byes, and to giving up. Family members also spoke about how difficult it was watching a loved one in pain and not receiving adequate medication. One family member spoke of how poignant it was witnessing her mother say good-bye to other family members for the last time.

Bearing witness occurs whenever one observes another's state without being able to affect the outcome. It can include elements of helplessness. These findings support those in other studies reporting that both caregivers and palliative care nurses “bear witness” to decline and suffering at the end of life. Caregivers have described this act as difficult (Kruse, 2004), possibly because of the existential questions that it raises; while it is seen as a caring act among palliative care nurses, (Arman, 2007).

Experience of loss

Family members in all settings discussed the experience of loss that resulted from the patient's illness and decline, but in some instances other simultaneous life losses as well. Some found that the loss of the companionship following admission to a facility and being alone was the hardest thing for them to deal with. For others, relinquishing the caregiving role was a difficult loss. Others found particular aspects of loss difficult, such as losing the parent figure. Still other family members spoke of the loss when the dying person did not recognize them anymore.

Prior research has acknowledged the loss and grief experienced among family caregivers of seriously ill persons in a variety of settings (Clukey, 2008; Dumont, Dumont, & Mongeau, 2008; Kiely, Prigerson, & Mitchell, 2008), yet little attention has been given to other simultaneous life losses that family members may be confronted with and how these losses may complicate their ability to cope with the caregiving experience, the impending death of the patient, and bereavement adjustment. Additional research is needed to identify contributing factors and consequences, and design and test interventions to more skillfully address these primary challenges.

While there has been extensive research to document the pervasive nature of loss, and many support strategies and interventions are available to health and human service professionals (Hooyman & Kramer, 2008), loss-related needs of family members may not be adequately assessed and addressed across settings of care. Assessing for other recent deaths in the family, or prior losses that are stimulated by the dying process should be explored.

Common Challenges in Inpatient Hospice Facility and the Skilled Nursing Facility

Unmet patient needs or wishes

Caregivers of persons who died in both the inpatient hospice and the SNF shared instances in which their family member's needs or wishes were not met. For SNF residents, the examples appeared to be related to lack of staff responsiveness. One family member told of how the patient and family member were forced to take care of the patient's personal care needs themselves, because these needs were not met by the staff.

“She ended up bathing herself, and she didn't do a good job. I go over and help her, but they should have enough staff in order to help somebody when they couldn't do it”. SNF family member #5

Unmet patient wishes in the inpatient hospice setting were clearly wishes that could not be met in that setting as they related to assisted suicide (see quote in Table 2). The state in which this study was conducted has a law preventing assisted suicide. As a result, the hospice staff could not provide that option, despite the intensity of the patient's desire.

Each person who spoke with us about a loved one whose needs or wishes were not met was especially distressed and visibly upset, even up to a year after the event. The issue of patient needs or wishes being unmet has been previously addressed in literature about skilled nursing facilities as a key indicator of poor quality (Bowers, Fibich, & Jacobson, 2001; Kayser-Jones, 2002; Munn et al., 2008; Reynolds, Henderson, Schulman, & Hanson, 2002; Thompson, Menec, Chochinov, & McClement, 2008). There is an important difference for care providers between needs and wishes, especially when the wishes are for events or things which are not possible, but there did not seem to be any difference in the emotional reaction of the family members. Meeting patient needs is essential to good care in any setting, but there may be barriers to meeting some patients' wishes, such as the legal barriers to assisted suicide in this case. In such cases it is important to address the emotional impact of the wish being unfulfilled in addition to explaining why the request or desire cannot be met.

Reality of death

Families in both the inpatient hospice and SNF talked about how hard it was to accept the reality that their loved one was actually dying, even if the person had been very ill for a long time. We found this somewhat surprising especially in the inpatient hospice setting where there may be a higher degree of expectation that family members will be accepting of the impending death by virtue of admission to hospice. Family members sometimes didn't realize how hard this was for them until later. These findings suggest that individuals often find it hard to accept the reality that their loved one is dying, even when they have had a long and serious illness and are admitted into a palliative care program. While accepting the reality of death is a prominent feature of the palliative care movement (Callahan, 2009), it has rarely been addressed in research. When it has, it is usually because researchers found that accepting the reality of death was hard for family, caregivers or healthcare professionals (de Araujo, da Silva, & Francisco, 2004) or as a suggestion that healthcare professionals should be more open about the reality of death (Csikai, 2006). Families' difficulties accepting the reality of death are important to bear this in mind as we are working with families of the dying. We may clearly see that the patient is nearing death, but the family may still experience shock when the realization hits them that this time their loved one will not recover. Practitioners may want to acknowledge the difficulty of bearing witness to the decline and or suffering of the patient. Attention should be given to the development of interventions to prepare families to “bear witness” at the end of life.

Final communications between patient and family

Family members talked about how important it was that they could communicate with their loved one until the end. When the dying person's condition prohibited communication, families were frustrated and felt cheated. Allowing time for important communication before giving sedating medications or before performing procedures that alter communication ability may have a profound effect on the family. If sudden clinical changes occur that prevent two-way communication, support for the family and encouragement for them to tell their family member those last important messages should be given.

Placement-related regrets

In both the inpatient hospice facility and the SNF family members expressed regrets regarding when and where they placed their loved one; however the nature of these regrets varied. In the SNF the regret focused on whether this was the best choice for the patient. In the inpatient hospice the regrets focused more on the timing of the inpatient hospice facility admission. It makes sense that the CSP families did not have regrets related to placement, since the goal of the program is to help people remain in their own homes for as long as possible.

While there is little information about length of stay in hospice facilities, short length of stay is a well documented concern of home hospice care providers. Family members of patients with life-threatening illnesses shared perceptions that longer lengths of stay would provide greater benefits for patients (Rickerson, Harrold, Kapo, Carroll, & Casarett, 2005) and caregivers of patients who had shorter lengths of stay were less satisfied with the care provided by hospice programs (Stillman & Syrjala, 1999). Knowledge gained from experienced family members regarding placement related regrets, may be shared with those considering hospice admission. Additional research is needed to understand the factors related to delayed admission so that these factors can be addressed directly.

Systems-related challenges to the optimal timing for placement in appropriate care settings should be acknowledged and addressed both by specific institutions and by the health care community. Families told us about both their regrets in placing family members in facilities shortly before their death and in not placing family members earlier into hospice. While no one can predict the best time for placement, open discussion of changes and early discussion of options, including hospice, might help patients and family members make decisions they can live with. Such discussions require education of a multitude of health professionals in different settings and cooperation between agencies to facilitate timely transitions in care.

Common Challenges in Inpatient Hospice Facility and the Community Support Program

Uncertainty

In both the inpatient hospice and the CSP family members talked about the challenge of uncertainty. They spoke of their doubts about the amount of pain medication their loved one received and whether it was necessary. They also spoke of the uncertainty of the disease process that posed challenges for them. Uncertainty is a concept that has been studied extensively in illness, especially cancer. It has been thoroughly described (Mishel & Braden, 1987; Mishel, Hostetter, King, & Graham, 1984; Mishel, Padilla, Grant, & Sorenson, 1991) and a number of interventions have been tested to reduce uncertainty (Bailey, Mishel, Belyea, Stewart, & Mohler, 2004; Mishel et al., 2002; Mishel et al., 2003). Uncertainty has recently been described as it relates to those facing the end of their lives (Gardner, 2008) and their family caregivers (Browning, 2009; Hebert, Schulz, Copeland, & Arnold, 2009). Communication between the family and the healthcare team was the primary means of decreasing or managing uncertainty by family members in these studies (Browning, 2009; Hebert et al., 2009).

Distinctive Challenges Raised in Single Settings

Inpatient Hospice Facility

Fulfilling family obligations surrounding death

Inpatient hospice family members talked about the challenge of making decisions to discontinue treatments, notifying other family members and making funeral arrangements. For some inpatient hospice families, these challenges were easier than they expected, for others they were much harder.

The doctors were feeding him his medicine – the lady up the street she said you can legally take his medicine away. And I said, well I'm not going to make that decision alone. I said we're going to make it as a family. But my oldest son, he wasn't too sure about doing that. He says, well I guess I need to go along with the rest of the family. He went out to see him [the patient] and he said “Mom, we made the best decision we could. Take the medicine away”. IHF family member #1

Although it is very likely that family members in other programs also are challenged by obligations surrounding the death, it is possible that the nature of admission criteria to hospice (i.e., prognosis of six months or less, meeting the Hospice Medicare guidelines), causes family members to make different decisions that make this challenge more pronounced in their response to study questions. These decisions may not be as salient or pronounced in other long-term care settings where the Medicare eligibility of the patient for care is not dependent on federal guidelines. Further work to explore the nature and extent of family obligations surrounding the death in this and other settings and how service providers might support family members to prepare them to meet these is needed.

Another topic that was discussed by inpatient hospice facility families was pain. We have chosen to place the issue of pain under “uncertainty” since the discussion of pain was a participant who wondered whether their loved one received too much pain medication. The other mention of pain in this study was from an inpatient hospice facility family member who spoke of the poor quality of pain management prior to inpatient hospice admission. The rarity of family members mentioning pain in this study is very different from previous research results. Pain management is a significant issue at the end of life. Problems with pain management have been well documented in the hospital, in hospice and in skilled nursing facilities (Desbiens et al., 1996; Johnson, Teno, Bourbonniere, & Mor, 2005; Strassels, Blough, Hazlet, Veenstra, & Sullivan, 2006; Teno, Kabumoto, Wetle, Roy, & Mor, 2004). It is curious that is was not raised by more participants in this study.

Community Support Program

Caregiving tasks and responsibilities

Families in the CSP, where the goal was to keep the person in their home as long as possible, often faced challenges in completing caregiving tasks and responsibilities. They spoke of the hardships of caregiving including social isolation and physical difficulties in providing care, the need to persevere through these hardships, and the burden imposed by having variations in the quality and consistency of personal care attendants. Multiple family members talked about how the inconsistency in personal care attendants made caregiving more challenging. One possible reason for this was the feeling of having their privacy invaded. Family members told of how difficult and disruptive it was to have different people in and out of the home.

Family caregivers told us how difficult it was keeping up with what their loved one's preferences for care were from day to day.

The hardest part was…she wanted to go off medication and die. And then she went back on again because she didn't want to. And it was just, I was in the middle and I had to make decisions. “OK, let go”, and then, “no”, she didn't want to go…and it was just terrible, terrible…It's really just too much to go through, thank God. But she made all of the decisions, and whatever she wanted I did, or what I thought she wanted. CSP family member #8

Community-based programs rely on family members to provide as much hands on care as is needed, and we know that end-stage family caregivers experience significant burdens and stressors including primary (i.e., providing near acute care) and secondary (i.e., family role conflict, work conflict, financial strain) stressors (Waldrop, Kramer, Skretny, Milch, & Finn, 2005). These caregiving issues would also be expected in a home hospice family member. Consumer-directed programs are expected to grow in the coming years and to face a workforce shortage of personal care attendants (Benjamin, Matthias, Kietzman, & Furman, 2008). The shortage makes it difficult to provide consistency in care providers which was reported as troublesome by family members. Some programs are investigating whether to pay family and friends to provide personal care as one way to buffer the financial and work related conflicts that may often arise (Benjamin et al., 2008). Additional interventions to help end-stage caregivers in the community setting feel less isolated, more skilled in providing care, and to have greater voice regarding hiring practices of personal care attendance are needed to address this challenge. Additional research comparing caregiving needs of those in community support programs and caregivers of those living at home in hospice would also be warranted.

Skilled Nursing Facility

There were three distinctive challenges expressed by family members of persons who died in the SNF facility that were not reported by family members in other settings

Absence of trust in care providers

Families of those who died in the SNF spoke about absence of trust in care providers and the need to be there to assure that the patient was well-cared for. One family member spoke of the strain this absence of trust put on her as she attempted to be with her loved one every day and feeling as if she needed to be present.

I was there every day except for the last day that he died… My husband said to me “can't you just take one day off and we go out of town?” Cuz he could tell I was getting stressed out about it…So it happened I was not in town the day that it happened. SNF family member #1

Families told us of how the concerns about their loved one's care were constantly in their awareness. This concern echoes those raised in previous research where families felt they needed to be present to assure their loved one's quality care (Teno, Casey, Welch, & Edgman-Levitan, 2001). For most people, trust in care providers is one of the key elements to having a good death experience (Kehl, 2006). The most logical way of addressing this need is to address the fact that patients' needs are not being met. Until we consistently address basic needs, such as cleanliness, safety, pain and symptom management, there will continue to be concerns from families about trusting care.

Personal belongings compromised

Family members spoke of a sense of violation when personal belongings were stolen or destroyed. One family member reported that the patient's “wedding rings were stolen off of her,” and another noted that “she lost money on a number of occasions…one time it was $300…they didn't keep a record of what she had.”

Insufficiencies in communication with staff

The lack of communication between staff, family and physicians was another challenge that family members felt could have been improved. One family member said, “I'd say the communication…between the kitchen and the staff who knew the patients could have been better.” SNF family member #2

More challenges were reported by family members of persons who died in the SNF than in the other two programs, and as opposed to the challenges reported in the other two settings, a number of these challenges could be construed as quality of care concerns. These include unmet patients needs, absence of trust in care providers, personal belongings compromised, insufficiencies in communication with staff and placement related regrets. Good pain and symptom management, clear communication, trust, respect, responsiveness to patient and family, and care of physical needs and belongings are all considered essential for quality palliative care (National Consensus Project Steering Committee, 2004). Nearly 25% of older adults die in long-term-care settings (Temkin-Greener & Mukamel, 2002), and several studies document insufficiencies in quality of care at the end of life in these settings (Kayser-Jones, 2002; Munn et al., 2008; Teno, Gruneir, Schwartz, Nanda, & Wetle, 2007). Additional work is needed to build on efforts to increase collaborative partnerships between nursing homes and palliative care programs, improve the knowledge and skills of nursing home staff, and plan research to design and test interventions in long term care settings. It is interesting that uncertainty was not raised in this setting, despite the evidence that poor communication contributes to uncertainty, yet in the CSP and inpatient hospice settings insufficiencies in communication was not mentioned while uncertainty was addressed.

Overall, much work needs to be done to address family concerns in every setting where people die. Universal concerns of family members facing the death of a loved one should be addressed in initial education and training of professionals working with those facing the end of life. Concerns that are consistently seen in multiple setting might best be addressed through specialty organizations and education programs. Single site concerns should be handled in orientation to a setting, and issues that are highly individual should be assessed for with every patient and family. Additional work looking at multiple settings that uses consistent methods will help us design and train the generation of professionals who will take care of us at the end of our lives.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study. The sample size was very small and only one agency was used to represent each setting. Even within the same community, the findings may differ in different hospitals or skilled care facilities. We cannot assume that the challenges reported by family members of persons enrolled in this particular community based program will be similar to those in other community based programs for older persons. This was a relatively resource rich and comprehensive interdisciplinary program that infused many palliative care principles, and only four challenges were reported. Other community-based programs may face different challenges. Respondents in our study were primarily Caucasian and not representative of the racial and ethnic mix of the community. This may be due to recruitment methods or due to the fact that some of the agencies involved such as the inpatient hospice and SNF have a greater percentage of Caucasians than the general population of the community.

Another limitation of the study is that member checking was not used to assure that participants were in agreement with the conclusions drawn. Member checking was not feasible for a number of reasons. There was a relatively long period of time during data collection (approximately 14 months). As we described at the beginning of the results section, almost one-half of the eligible family members were unreachable six to twelve months after the death. This is similar to the recruitment found in other studies concerning care at the end of life or of those with cancer (Kirchhoff & Kehl, 2008; Northouse et al., 2006). It was thought that additional participants were likely to move or die between data collection and review since some studies have shown increased mortality among widows and rate of moving in the recently bereaved (Bowling & Charlton, 1987; Browning & Cartwright, 1982).

Finally, the settings chosen created a limitation. These findings do not reflect all of the settings in which people die. In particular, home hospice families or those receiving home health services were not included. Future research should be expanded to include home hospice, home health and assisted living facilities, as well as hospitals to get a better picture of issues for the families at the end of life across settings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we know little about family perceptions of care for a dying person across different settings. This lack of knowledge hinders our efforts in educating professionals who work with the families of dying individuals and may impair the ability to optimize care, especially as individuals cross settings in the last days and weeks of their lives. This study provides preliminary evidence of common concerns across settings such as the universal human experiences of bearing witness and the experience of loss. It also provides initial evidence of differences in family challenges in different settings, such as the unmet patient needs and wishes, reality of death, final communication between the dying person and their family, and placement regrets that were considered the most difficult aspects of family experiences for some in the inpatient hospice or the skilled nursing facility. It confirms previous research highlighting inadequate end-of-life care in SNFs leading to the families' lack of trust in providers. And it raises questions as to why pain management was so rarely mentioned by the family members in this study as pain management is generally considered extremely important to family members (Byock, Corbeil, & Goodrich, 2009; Downey, Engelberg, Curtis, Lafferty, & Patrick, 2009)

Further research is needed to address the common and distinctive needs of patients and families in different care programs. Caring professionals should be aware of these issues and seek to meet family members' needs in each setting where people die. This study suggests areas for additional study and supports the need for describing the experiences at the end of life in different settings and the importance of creating and testing interventions for both setting-specific needs and universal issues.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funds from the Charlotte Jane & Ralph A. Rodefer Chair at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, School of Nursing. Dr. Kehl was supported by grant 1UL1RR025011 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health during the writing of this manuscript. The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Lioness Ayres, PhD in developing the interview questions.

References

- Andershed B. Relatives in end-of-life care--part 1: a systematic review of the literature the five last years, January 1999-February 2004. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15(9):1158–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andershed B, Ternestedt BM. Involvement of relatives in care of the dying in different care cultures: Development of a theoretical understanding. Nursing Science Quarterly. 1999;12(1):45–51. doi: 10.1177/08943189922106404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoun S, Kristjanson L, Oldham L. The challenges and unmet needs of people with neurodegenerative conditions and their carers. Journal for Community Nurses. 2006;11(1):17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aoun S, Kristjanson LJ, Currow DC, Hudson PL. Caregiving for the terminally ill: at what cost? Palliat Med. 2005;19(7):551–555. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1053oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arman M. Bearing witness: an existential position in caring. Contemp Nurse. 2007;27(1):84–93. doi: 10.5555/conu.2007.27.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer WM, Hanson LC. Families' perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):879–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey DE, Mishel MH, Belyea M, Stewart JL, Mohler J. Uncertainty intervention for watchful waiting in prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(5):339–346. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200409000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin AE, Matthias RE, Kietzman K, Furman W. Retention of paid related caregivers: who stays and who leaves home care careers? Gerontologist. 2008;48(Spec No 1):104–113. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.supplement_1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers BJ, Fibich B, Jacobson N. Care-as-service, care-as-relating, care-as-comfort: understanding nursing home residents' definitions of quality. Gerontologist. 2001;41(4):539–545. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A, Charlton J. Risk factors for mortality after bereavement: a logistic regression analysis. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1987;37(305):551–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Broback G, Bertero C. How next of kin experience palliative care of relatives at home. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2003;12(4):339–346. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning AM. Empowering family members in end-of-life care decision making in the intensive care unit. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2009;28(1):18–23. doi: 10.1097/01.DCC.0000325092.39154.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning AM, Cartwright A. Life after a death: A study of the elderly widowed. New York: Tavistock Publications; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Byock IR, Corbeil YJ, Goodrich ME. Beyond polarization, public preferences suggest policy opportunities to address aging, dying, and family caregiving. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26(3):200–208. doi: 10.1177/1049909108328700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan D. Death, mourning, and medical progress. Perspect Biol Med. 2009;52(1):103–115. doi: 10.1353/pbm.0.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clukey L. Anticipatory mourning: processes of expected loss in palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2008;14(7):316, 318–325. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2008.14.7.30617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey AJ, Atkinson PA. Making sense of qualitative data: Complementary research strategies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Csikai EL. Bereaved hospice caregivers' perceptions of the end-of-life care communication process and the involvement of health care professionals. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(6):1300–1309. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Araujo MM, da Silva MJ, Francisco MC. Nursing the dying: essential elements in the care of terminally ill patients. Int Nurs Rev. 2004;51(3):149–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbiens NA, Wu AW, Broste SK, Wenger NS, Connors AF, Jr, Lynn J, et al. Pain and satisfaction with pain control in seriously ill hospitalized adults: findings from the SUPPORT research investigations. For the SUPPORT investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatmentm. Critical Care Medicine. 1996;24(12):1953–1961. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199612000-00005. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey L, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, Patrick DL. Shared priorities for the end-of-life period. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(2):175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drisko J. Strengthening qualitative studies and reports: Standards to enhance academic integrity. Journal of Social Work Education. 1997;33:10. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont I, Dumont S, Mongeau S. End-of-life care and the grieving process: family caregivers who have experienced the loss of a terminal-phase cancer patient. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(8):1049–1061. doi: 10.1177/1049732308320110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DS. Cancer in a dyadic context: older couples' negotiation of ambiguity and search for meaning at the end of life. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2008;4(2):135–159. doi: 10.1080/15524250802353959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grbich C, Parker D, Maddocks I. The emotions and coping strategies of caregivers of family members with a terminal cancer. Journal of Palliative Care. 2001;17(1):30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Remsburg RE, McAuley WJ, Keay TJ, Travis SS. TRENDS: National Trends In Adult Hospice Use: 1991-1992 To 1999-2000. Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):792–799. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert RS, Schulz R, Copeland VC, Arnold RM. Preparing family caregivers for death and bereavement. Insights from caregivers of terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooyman N, Kramer BJ. Living through loss: Interventions across the life span. New York: Columbia University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Brazil K, Lohfield L, Willison K. Caregiving at the end of life: Perspectives from spousal caregivers and care recipients. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2007;5(1):11–17. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507070034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VM, Teno JM, Bourbonniere M, Mor V. Palliative care needs of cancer patients in U.S. nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(2):273–279. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser-Jones J. The experience of dying: an ethnographic nursing home study. Gerontologist. 2002;42(Spec No 3):11–19. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan O, McGee H, Hogan M, Kunin H, O'Brien S, O'Siorain L. Relatives' views of health care in the last year of life. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2001;7(9):449–456. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2001.7.9.9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehl KA. Moving toward peace: an analysis of the concept of a good death. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23(4):277–286. doi: 10.1177/1049909106290380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely DK, Prigerson H, Mitchell SL. Health care proxy grief symptoms before the death of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(8):664–673. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181784143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N, Bell D, Thomas K. Family carers' experiences of out-of-hours community palliative care: a qualitative study. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2004;10(2):76–83. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.2.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff KT, Kehl KA. Recruiting participants in end-of-life research. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;24(6):515–521. doi: 10.1177/1049909107300551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer BJ, Auer C. Challenges to providing end-of-life care to low-income elders with advanced chronic disease: lessons learned from a model program. Gerontologist. 2005;45(5):651–660. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer BJ, Christ GH, Bern-Klug M, Francoeur RB. A national agenda for social work research in palliative and end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(2):418–431. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristjanson LJ, Walton J, Toye C. End-of-life challenges in residential aged care facilities: a case for a palliative approach to care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11(3):127–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse B. The meaning of letting go: The lived experience for caregivers of persons at the end of life. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2004;6(4):215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Long J. Inpatient hospice facilities more common. Chicago Tribune. 2008 9/15/2008. Retrieved July 17, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marks NF. Caregiving across the lifespan: National prevalence and predictors. Family Relations. 1996;45:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Milberg A, Strang P, Carlsson M, Borjesson S. Advanced palliative home care: next-of-kin's perspective. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2003;6(5):749–756. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, Stewart JL, Bailey DE, Jr, Robertson C, et al. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 2002;94(6):1854–1866. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel MH, Braden CJ. Uncertainty. A mediator between support and adjustment. West J Nurs Res. 1987;9(1):43–57. doi: 10.1177/019394598700900106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel MH, Germino BB, Belyea M, Stewart JL, Bailey DE, Jr, Mohler J, et al. Moderators of an uncertainty management intervention: for men with localized prostate cancer. Nurs Res. 2003;52(2):89–97. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel MH, Hostetter T, King B, Graham V. Predictors of psychosocial adjustment in patients newly diagnosed with gynecological cancer. Cancer Nurs. 1984;7(4):291–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel MH, Padilla G, Grant M, Sorenson DS. Uncertainty in illness theory: a replication of the mediating effects of mastery and coping. Nurs Res. 1991;40(4):236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn JC, Dobbs D, Meier A, Williams CS, Biola H, Zimmerman S. The end-of-life experience in long-term care: five themes identified from focus groups with residents, family members, and staff. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):485–494. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Consensus Project Steering Committee. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Rosset T, Phillips L, Mood D, Schafenacker A, Kershaw T. Research with families facing cancer: the challenges of accrual and retention. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(3):199–211. doi: 10.1002/nur.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett D. Qualitative methods in social work research : challenges and rewards. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Perreault A, Fothergill-Bourbonnais F, Fiset V. The experience of family members caring for a dying loved one. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2004;10(3):133–143. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.3.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce SF. Improving end-of-life care: gathering suggestions from family members. Nurs Forum. 1999;34(2):5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1999.tb00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proot IM, Abu-Saad HH, Crebolder HF, Goldsteen M, Luker KA, Widdershoven GA. Vulnerability of family caregivers in terminal palliative care at home; balancing between burden and capacity. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2003;17(2):113–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds K, Henderson M, Schulman A, Hanson LC. Needs of the dying in nursing homes. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2002;5(6):895–901. doi: 10.1089/10966210260499087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickerson E, Harrold J, Kapo J, Carroll JT, Casarett D. Timing of hospice referral and families' perceptions of services: are earlier hospice referrals better? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):819–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A, Karlsen S, Addington-Hall J. ‘All the services were excellent. It is when the human element comes in that things go wrong’: dissatisfaction with hospital care in the last year of life. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(4):768–774. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose KE. A qualitative analysis of the information needs of informal carers of terminally ill cancer patients. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8(1):81–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajduhar KI. Examining the perspectives of family members involved in the delivery of palliative care at home. J Palliat Care. 2003;19(1):27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(19):2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Christakis NA, McIntyre LM, Tulsky JA. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;132(10):825–832. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman MJ, Syrjala KL. Differences in physician access patterns to hospice care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1999;17(3):157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R, Cafferata GL, Sangl J. Caregivers of the frail elderly: a national profile. Gerontologist. 1987;27(5):616–626. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassels SA, Blough DK, Hazlet TK, Veenstra DL, Sullivan SD. Pain, demographics, and clinical characteristics in persons who received hospice care in the United States. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(6):519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin-Greener H, Mukamel DB. Predicting place of death in the program of all-inclusive care for the elderly (PACE): participant versus program characteristics. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):125–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Casey VA, Welch LC, Edgman-Levitan S. Patient-focused, family-centered end-of-life medical care: views of the guidelines and bereaved family members. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 2001;22(3):738–751. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(1):88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, Nanda A, Wetle T. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: a national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Kabumoto G, Wetle T, Roy J, Mor V. Daily pain that was excruciating at some time in the previous week: prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):762–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson GN, Menec VH, Chochinov HM, McClement SE. Family satisfaction with care of a dying loved one in nursing homes: what makes the difference? J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(12):37–44. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20081201-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop DP, Kramer BJ, Skretny JA, Milch RA, Finn W. Final transitions: family caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(3):623–638. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzner MA, McMillan SC, Jacobsen PB. Family caregiver quality of life: differences between curative and palliative cancer treatment settings. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management. 1999;17(6):418–428. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SA, Daley BJ. Family perspectives on dying in long-term care settings. J Gerontol Nurs. 1999;25(11):19–25. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19991101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]