Abstract

The effect of preexisiting hyperglycemia on cerebral blood flow (CBF) and brain penetrating arterioles before and after 2 h of ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion was determined. Male Wistar rats that were either hyperglycemic (50 mg/kg streptozotocin; n=24) or normoglycemic (n=24) were subjected to transient ischemia by filament occlusion or nonischemic. CBF was measured prior to ischemia using microspheres and during transient ischemia using laser Doppler. Edema was compared by wet/dry weights. Constriction to apamin, TRAM-34, and L-NNA, inhibitors of small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (SK and IK) and nitric oxide, were compared in penetrating arterioles from the ischemic hemisphere to investigate changes in basal tone and endothelium-dependent vasodilator responses. Preexisiting hyperglycemia did not affect CBF in non-ischemic animals or after transient ischemia; however, edema was significantly greater. Ischemia and reperfusion caused decreased basal tone in penetrating arterioles similarly in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals that was restored by apamin, and further increased by TRAM-34 and L-NNA. The restoration of tone in penetrating arterioles by apamin and TRAM-34 suggests that transient ischemia activates SK and IK channels in penetrating arterioles. This effect of ischemia was not different between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals, suggesting that it was related to ischemia and reperfusion rather than hyperglycemia.

Keywords: Hyperglycemia, Ischemic stroke, Lenticulostriate arterioles, Calcium-activated potassium channels, Cerebral edema

Introduction

Hyperglycemia is common in acute stroke, affecting 30–50% of patients, often without preexisting diabetes [1–4]. Numerous studies have shown that admission hyperglycemia worsens stroke outcome and is an independent risk factor for death and disability following ischemic stroke [4–9]. The risk of death in nondiabetic hyperglycemic stroke patients is increased 3-fold [9], suggesting that it is hyperglycemia per se and not complications associated with diabetes that contributes to poor outcome in these patients.

In animal studies, hyperglycemia has also been shown to aggravate ischemic injury. Preexisting hyperglycemia increases infarction, edema formation, and hemorrhagic transformation during transient ischemia [10–13]. Both metabolic derangements [13] and increased perfusion deficit due to poor reperfusion [10–12] have been shown to contribute to worsened outcome with hyperglycemic stroke. In addition, longer ischemia and more severe hyperglycemia appear to impact the vasculature to cause poor recanalization, suggesting that the vascular effects of hyperglycemia in worsening stroke outcome may be related to the duration of ischemia and degree of hyperglycemia [14].

Although hyperglycemia occurs with all stroke subtypes, the detrimental effects of high admission glucose appear to occur only with cortical stroke and not lacunar. Several clinical and experimental studies have shown that hyperglycemia does not worsen outcome from lacunar stroke and in some studies, patients with hyperglycemia had better outcome than normoglycemic patients [8, 15–18]. For example, results from the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) found that hyperglycemia worsened outcome in non-lacunar stroke, but not in lacunar stroke [8]. In addition, in the placebo arm of the TOAST trial, hyperglycemic patients with lacunar stroke had better outcome than normoglycemic patients. Further, a study that specifically compared the impact of hyperglycemia on outcome from lacunar and cortical strokes found that moderate hyperglycemia (between 8 and 12 mmol/L) significantly worsened outcome with cortical stroke, but was associated with more favorable outcome in patients with lacunar stroke [15]. The beneficial effect of hyperglycemia on lacunar stroke has also been suggested by animal studies. Animals with end-artery infarcts, as opposed to proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), had decreased infarct and better outcome with hyperglycemia [17, 18].

The underlying mechanism by which hyperglycemia improves lacunar stroke is not clear, but has been suggested to involve lactate production in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes that protect axons in white matter [15]. Another possibility is that the effect of hyperglycemia and/or ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) has a different effect on the vasculature involved in lacunar vs. cortical strokes. The major vascular segment involved in lacunar stroke is the penetrating (lenticulostriate) arterioles [19]. Unlike the pial circulation, these arterioles are long and largely unbranched vessels without a collateral supply [20]. They have been shown to be functionally distinct from upstream arteries (e.g., MCA) in that they have greater basal tone and are unresponsive to some neurotransmitters (norepinephrine and serotonin) [21]. In addition, penetrating arterioles appear to have a greater influence of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) on basal tone, compared to larger cerebral arteries, that can contribute to cerebral blood flow (CBF) [22, 23]. In a study comparing the effect of I/R on MCA and penetrating arterioles from the same animals, basal tone and EDHF responses were well preserved in penetrating arterioles after I/R, but not MCA, suggesting there are significant differences in how vascular segments respond to I/R [23].

In the present study, we investigated the effect of hyperglycemia on the function of penetrating arterioles from within the MCA territory (lenticulostriates), including changes in endothelial function and basal tone. We also investigated how these vessels were affected after MCAO under normoglycemic and hyperglycemic conditions. In addition, because changes in CBF can affect outcome, we also measured CBF prior to and after MCAO in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals.

Methods

Animals

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animals were male Wistar rats (350–380 g) that were either normoglycemic (N=24) or hyperglycemic (N=24) for 6 days by streptozotocin (50 mg/kg i.p.). Glucose was measured on days 0, 1, and 6 by a commercially available glucose monitor (Accucheck).

Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion

Some normoglycemic (n=12) and hyperglycemic (n=12) animals underwent MCAO for 2 h followed by 30 min of reperfusion by filament occlusion, as previously described [23]. Briefly, animals were anesthetized by a mixture of isoflurane in room air and oxygen. A mid-line incision was made, and the common carotid and external carotid arteries were exposed. After ligation of the common carotid artery, a 5-O monofilament coated with silicone was inserted into the external carotid artery and advanced into the internal carotid artery to the bifurcation with the middle cerebral artery. Reperfusion was accomplished by withdrawing the suture. Blood gases were maintained within normal ranges by adjusting the amount of inspired air and measured at the start, middle, and end of each surgery by a blood gas analyzer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physiological characteristics of normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals used

| Normoglycemic MCAO (n=12) |

Hyperglycemic MCAO (n=12) |

Normoglycemic Microspheres (n=6) |

Hyperglycemic Microspheres (n=6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 91±2 | 347±21** | 125±10 | 316±34** |

| Weight (g) | 361±10 | 320±15* | 363±12 | 328±16 |

| Blood gases start | ||||

| pH | 7.41±0.006 | 7.43±0.007 | 7.37±0.013 | 7.40±0.017 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 41.4±1.0 | 38.3±0.8 | 27.7±5.5 | 31.1±3.2 |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 240.8±15.5 | 260.0±10.4 | 174.3±26.8 | 131.7±9.8 |

| Blood gases middle | ||||

| pH | 7.40±0.005 | 7.40±0.008 | 7.36±0.009 | 7.40±0.016 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 47.3±0.6 | 43.7±1.1 | 35.5±4.6 | 37.6±3.3 |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 164.7±11.7 | 195.3±19.5 | 141.2±22.8 | 127.2±9.1 |

| Blood gases end | ||||

| pH | 7.40±0.004 | 7.39±0.006 | 7.39±0.010 | 7.41±0.006 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 47.5±0.6 | 47.1±0.8 | 40.1±3.7 | 40.3±1.5 |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 172.4±18.3 | 199.4±22.7 | 154.7±17.1 | 143.5±12.7 |

p<0.05 vs. normoglycemic;

p<0.01 vs. normoglycemic

Measurement of CBF

CBF was continuously measured during MCAO and for 30 min of reperfusion by laser Doppler flowmetry, as previously described [23, 24]. Briefly, the flow probe was affixed over a thinned area of skull posterior to the coronal suture and lateral to the sagittal suture over the middle cerebral artery perfusion domain. In addition, because acute hyperglycemia has been shown to affect CBF [25, 26], we measured absolute CBF using microspheres in nonischemic normoglycemic (n=6) and hyperglycemic (n=6) animals. Briefly, under pentobarbital anesthesia, a catheter (PE50) was placed into the left ventricle via the carotid artery and fluorescent microspheres (shaken vigorously) were injected within 10–20 s. After 1 min, reference samples were taken from both brachial arteries at a known flow rate (0.21 mL/min). The animal was then euthanized by decapitation, and the brain was removed and processed for determination of fluorescence in both the reference samples and brain tissue. CBF was calculated by the equation CBF = (Ct × 100 × Qr)/Cr, where Ct and Cr are the counts in the tissue and reference samples, respectively, and Qr is the flow rate of the reference sample. CBF is expressed as mL per 100 g brain tissue per minute.

Measurement of Edema

Because dissection of penetrating arterioles destroyed brain tissue, infarction was not measured. However, in previous studies, we have found that infarction was ~40% greater in similarly hyperglycemic animals compared to normoglycemic [27]. To assess the effect of MCAO on stroke outcome, edema was measured in normoglycemic (n=6) and hyperglycemic (n=6) animals by wet/dry weights. Briefly, ipsilateral and contralateral cerebral cortex (brainstem and cerebellum removed) were weighed wet then dried over-night at 90°C. The brain sections were then weighed dry, and the ratio of wet to dry weight for each hemisphere was used as a measure of edema.

Isolated and Pressurized Penetrating Arterioles

Isolation and mounting of penetrating arterioles in a pressurized arteriograph chamber has been previously described [23, 24]. Once mounted and pressurized to 40 mmHg, basal tone and constriction in response to cumulative addition of apamin (300 nM), TRAM-34 (1.0 µM), and L-NNA (0.1 mM) were determined, as previously described [23]. These compounds specifically inhibit SK and IK channels in endothelium and eNOS, respectively. Glucose concentration was adjusted in the bath solution so that it matched the animals’ glucose, determined at the time of euthanasia.

Data Calculations

Vascular tone was calculated as a percent decrease in diameter from the fully relaxed diameter in papaverine by the equation: (1−(ϕtone/ϕpapav))×100%; where ϕtone is the diameter of vessel with tone, and ϕpapav is the diameter in papaverine. Percent constriction was calculated as a percent change in diameter from baseline by the equation: (1−(ϕdrug/ϕbaseline))×100%, where ϕdrug is the diameter of vessel in either apamin, TRAM-34, or L-NNA, and ϕbaseline is the diameter prior to giving the drug.

Statistics

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between groups were determined using one-way analysis of variance with a post hoc Student–Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons, where appropriate. Differences in water content between contralateral and ipsilateral hemispheres were determined using paired t test.

Drugs and Solutions

All experiments were conducted using Krebs PSS (a bicarbonate-based buffer aerated with 5% CO2, 10% O2, and 85% N2 to maintain pH), and the ionic composition was (mmol/L): NaCl 119.0, NaHCO3 24.0, KCl 4.7, KH2PO4 1.18, MgSO4 7H2O 1.17, CaCl2 1.6, and EDTA 0.026. PSS was made each week and stored without glucose at 4°C; glucose was added to the PSS prior to each experiment and adjusted to match the level of glucose for each animal. Apamin and TRAM-34 were purchased from Tocris Biosciences (Ellisville, MO, USA) and kept frozen until used. L-NNA and papaverine were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Results

Effect of Hyperglycemia on CBF

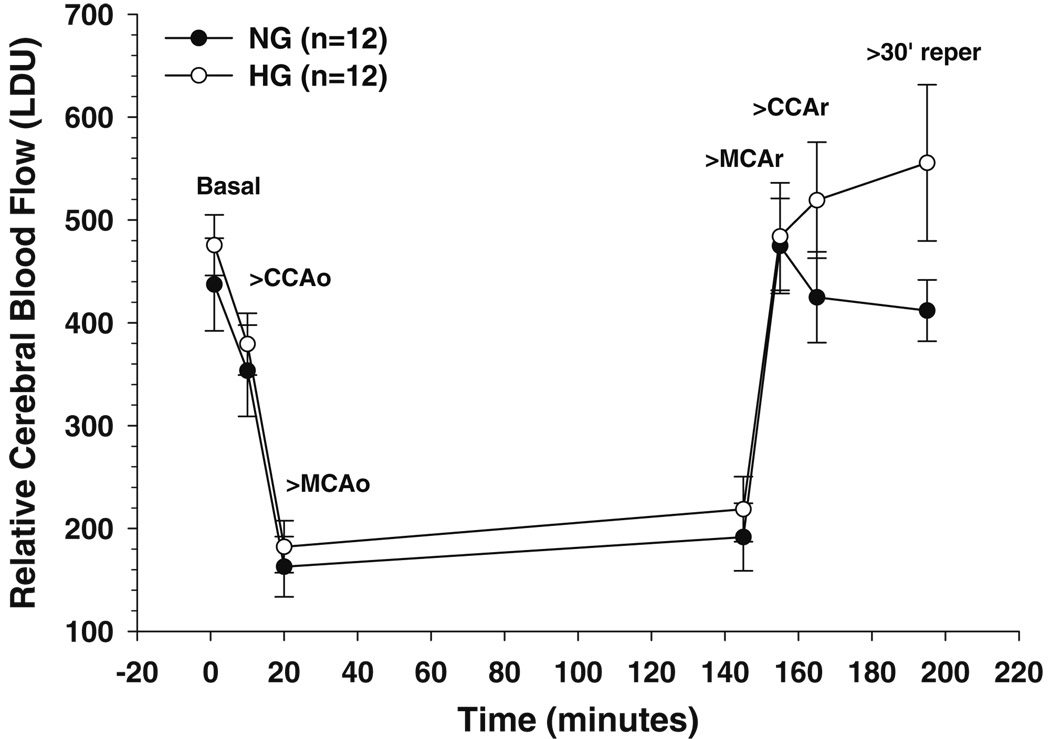

Hyperglycemia has been shown to affect perfusion deficit during MCAO and worsen stroke outcome [10–12]. We therefore measured CBF during MCAO and for 30 min of reperfusion using laser Doppler. Figure 1 shows changes in relative CBF during MCAO for hyperglycemic and normoglycemic animals. There was no difference in the depth of ischemia that was maintained for the duration of occlusion (2 h). Reperfusion resulted in recanalization in both groups of animals, with hyperglycemic animals tending to have higher flows after 30 min of reperfusion than normoglycemic animals (p=0.092).

Fig. 1.

Relative changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) during MCAO and for 30 min of reperfusion using laser Doppler flowmetry. Changes in flow in response to carotid occlusion (CCAo) and middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) and after restoration of CBF to allow reperfusion of the middle cerebral artery (MCAr) and carotid artery (CCAr). There was no difference in CBF either basally or in response to occlusion between normoglycemic (closed circles) and hyperglycemic (open circles) animals. Reperfusion restored CBF to normal in both groups, with hyperglycemic animals tending to have higher flows after 30 min of reperfusion compared to normoglycemic (p=0.09)

Because laser Doppler is a relative measure of CBF, we wanted to know if hyperglycemia affected basal blood flow that could influence perfusion deficit and outcome. We therefore used microspheres in nonischemic hyperglycemic and normoglycemic animals. There was no difference in CBF between groups. Blood flow for hyperglycemic vs. normoglycemic animals at baseline was 81±6 vs. 73±8 mL per 100 g per min; p>0.05. These results suggest that hyperglycemia did not influence basal blood flow and that comparison of CBF between groups using laser Doppler is an accurate approach.

Table 1 shows physiological parameters for animals that underwent MCAO and measurement of CBF with microspheres. All blood gases and pH were within normal ranges. Blood glucose was higher in the hyperglycemic animals, as expected. Hyperglycemic animals had smaller body weights than their normoglycemic controls.

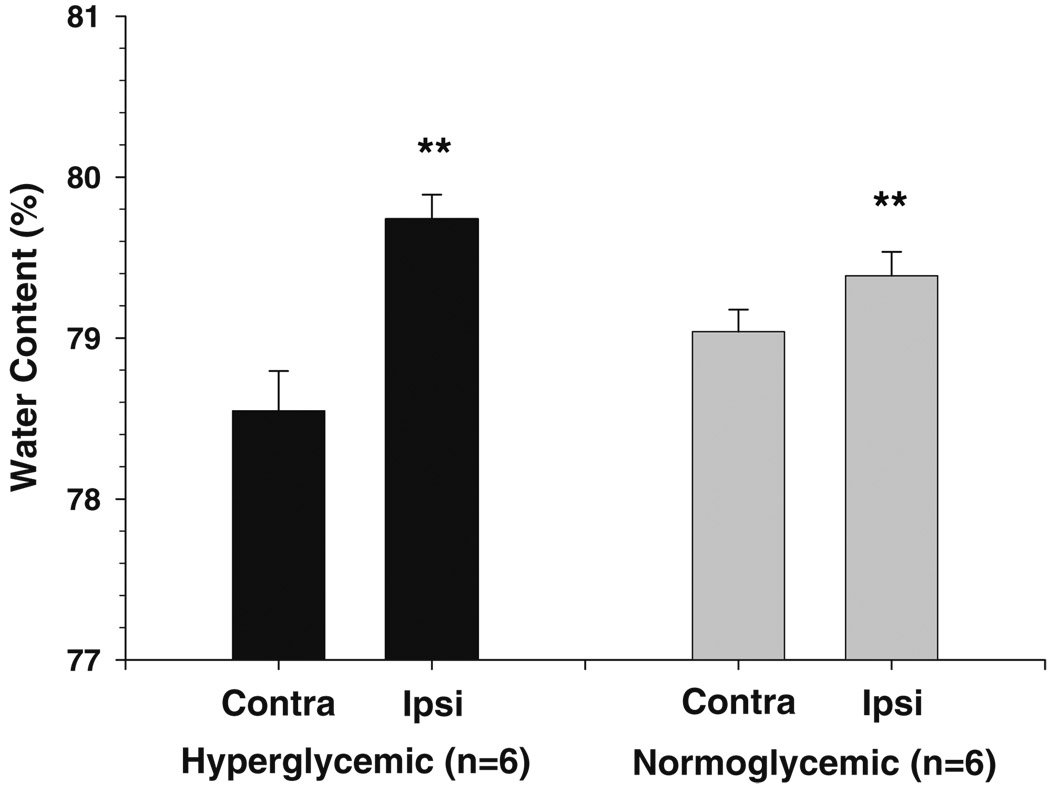

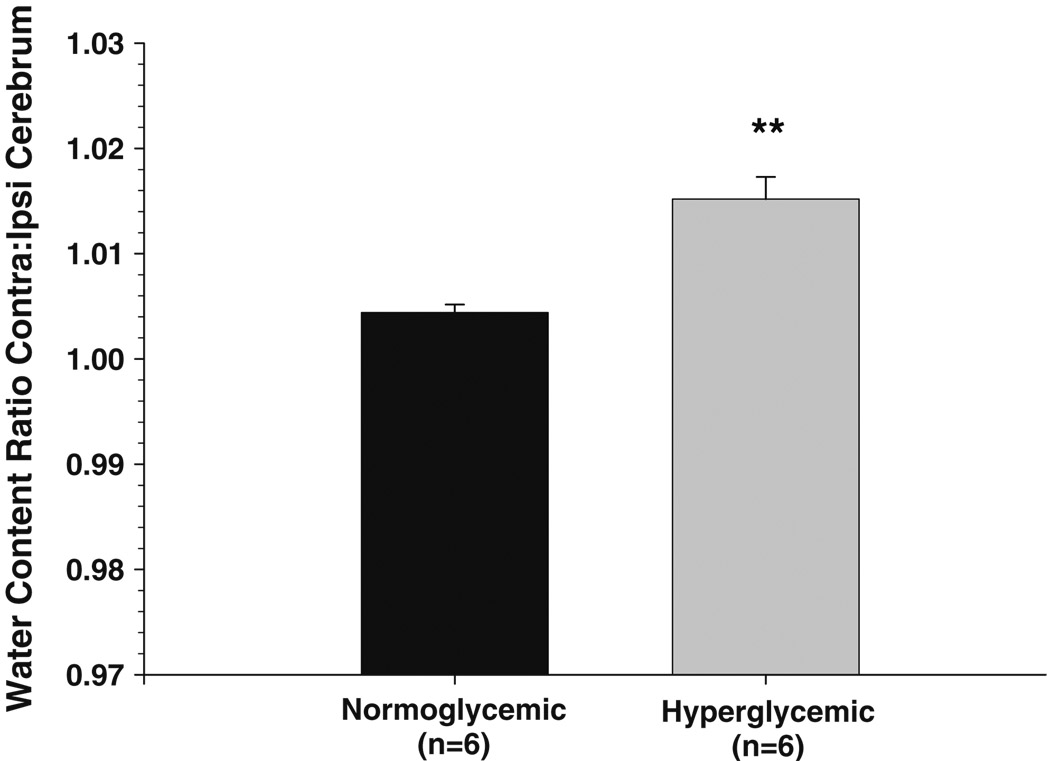

Effect of Hyperglycemic on Cerebral Edema Formation

MCAO increased water content in the ipsilateral hemisphere compared to contralateral in both normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals (Fig. 2). Hyperglycemic animals had a significantly greater increase in water compared to normoglycemic animals, as seen by calculating the ratio of water between the two hemispheres (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Brain water content in ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres from normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals after 2 h of ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion. MCAO caused vasogenic edema and increased water content in the ipsilateral hemisphere in both normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals (**p<0.01 vs. contralateral)

Fig. 3.

Ratio of ipsilateral to contralateral water content after 2 h of ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals. Hyperglycemic animals had a significantly greater increase in water content compared to normoglycemic animals (**p<0.01 vs. normoglycemic)

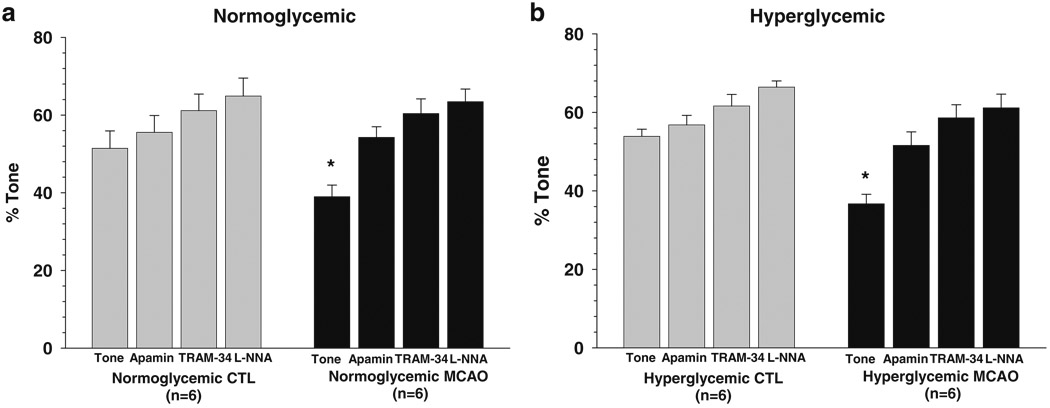

Effect of Hyperglycemia and MCAO on Basal Tone and Endothelial Vasodilator Production

The function of penetrating arterioles was assessed prior to stroke in nonischemic animals and after MCAO in both hyperglycemic and normoglycemic animals by measuring basal tone and constriction to inhibitors of endothelium-dependent vasodilators. SK and IK channels have been shown to be expressed only in endothelium, and their activation is a critical step in EDHF responses [23, 28, 29]. Therefore inhibition of these channels interferes with EDHF production [28, 29]. A previous study demonstrated that penetrating arterioles constrict in response to channel inhibition, suggesting basal EDHF production in these arterioles that mitigates tone [23]. Similarly, inhibition of eNOS with the L-NNA causes constriction in these and other cerebral vessels, suggesting basal NO production that also contributes to vascular tone [23, 24, 30]. Constriction in response to these inhibitors is a common approach to assessing basal production of vasodilator [21–24, 30].

Figure 4a shows percent tone under basal conditions and after addition of apamin, TRAM-34, and L-NNA in normoglycemic animals that were nonischemic and after MCAO. Penetrating arterioles under nonischemic conditions had considerable basal tone (51±5%) that was somewhat diminished by MCAO (38±3%; p<0.05). Addition of apamin caused constriction in both groups of arterioles that was greater after MCAO. In fact, apamin restored tone in penetrating arterioles after MCAO such that it was similar to controls (56±4% vs. 54±3%; p>0.05). Addition of TRAM-34 and L-NNA increased tone further in both groups.

Fig. 4.

Percent tone in penetrating arterioles basally at 40 mmHg and after cumulative addition of apamin (300 nM), TRAM-34 (1.0 µM), and L-NNA (0.1 mM) prior to and after 2 h of ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion. Normoglycemic animals are shown in a, and hyperglycemic animals are shown in b. Penetrating arterioles had considerable basal tone that was increased with addition of apamin, TRAM-34, and L-NNA. There was no difference in tone between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals prior to MCAO. However, after MCAO, arterioles had diminished tone that was restored by apamin, suggesting that ischemia and reperfusion activate these channels. There was no difference in tone after MCAO between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals. *p<0.05 vs. nonischemic

Figure 4b shows percent tone of penetrating arterioles in hyperglycemic animals under the same conditions. Similar to normoglycemic animals, penetrating arterioles had considerable basal tone (54±2%) that was diminished after MCAO (37±2; p<0.05). Also similar to normoglycemia, apamin caused constriction and restored tone in penetrating arterioles from hyperglycemic animals after MCAO such that it was not different from nonischemic arterioles (57±2% vs. 52±3%; p>0.05).

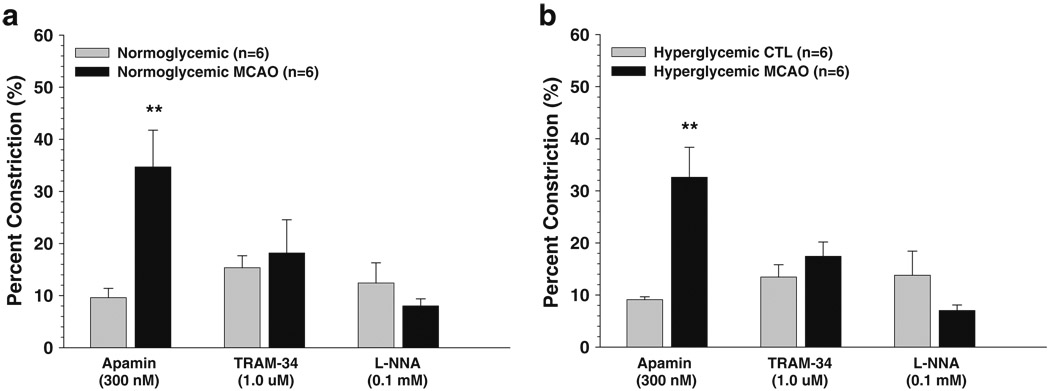

There was no difference in basal tone or constriction to inhibitors between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals under nonischemic conditions or after I/R. However, there was a significant increase in constriction to SK channel inhibition with apamin after I/R in both normoglycemic and hyperglycemic penetrating arterioles. Figure 5 shows the percent constriction to apamin, TRAM-34, and L-NNA in normoglycemic (Fig. 5a) and hyperglycemic (Fig. 5b) animals. Notice that similar to our previous study [23], SK and IK channel inhibition with apamin and TRAM-34 caused constriction in all groups of arterioles, suggesting that these arterioles possess basal EDHF production that mitigates basal tone. In addition, constriction to apamin was significantly increased after MCAO in both normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals, suggesting that I/R diminished tone through activation of these channels. It is worth noting that percent constriction was calculated from the baseline diameter after cumulative addition of inhibitor in order to limit the number of animals used. Thus, it is possible that TRAM-34 would have produced a similar constriction as apamin if given first. In any case, SK and IK channels appear to be basally active in penetrating arterioles, an effect that is increased with I/R.

Fig. 5.

Percent constriction of penetrating arterioles after cumulative addition of apamin (300 nM), TRAM-34 (1.0 µM), and L-NNA (0.1 mM) prior to and after 2 h of ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion. Normoglycemic animals are shown in a, and hyperglycemic animals are shown in b. All vessels from all groups constricted to apamin, TRAM-34, and L-NNA, suggesting that basal EDHF and NO are produced in these vessels that mitigate tone. There was no difference in constriction between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals prior to MCAO; however, arterioles responded with greater constriction to apamin after MCAO. There was no difference in constriction after MCAO between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals. **p<0.01 vs. nonischemic

Discussion

The present study investigated the effect of hyperglycemia on reperfusion blood flow and the function of penetrating (lenticulostriate) arterioles before and after MCAO. We found that prior to MCAO, hyperglycemia had no effect on CBF or basal tone of penetrating arterioles. Similar to our previous study [23], arterioles from both groups of animals constricted to apamin, TRAM-34, or L-NNA, suggesting a significant influence of EDHF and NO in mitigating basal tone that was not affected by hyperglycemia. However, transient MCAO decreased tone in penetrating arterioles that was restored by apamin, suggesting that I/R decreases tone via activation of SK channels in the endothelium. The effect of MCAO on tone was similar between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals, suggesting that this effect was independent of glucose and more related to I/R. Lastly, we did not find any effect of hyperglycemia on perfusion deficit or reperfusion blood flow with hyperglycemia. These results suggest that after 30 min of reperfusion, hyperglycemia does not affect perfusion deficit, reperfusion blood flow, or endothelium-dependent vasodilator production in penetrating arterioles.

Previous studies have shown that hyperglycemia increased perfusion deficit and impaired reperfusion compared to normoglycemic animals after longer durations of I/R [10–12]. For example, Quast et al. showed increased perfusion deficit after 2-h ischemia with 2 h of reperfusion that positively correlated with blood glucose levels [10]. Kawai et al. also showed decreased reperfusion in hyperglycemic animals after 2 h of ischemia with 2 h of reperfusion [11]. In contrast, Gisselsson et al. found that hyperglycemia caused more severe tissue damage after 30 min of ischemia with 1 h of reperfusion [13]. These investigators did not find any effect of hyperglycemia on reperfusion blood flow, suggesting that metabolic derangements (e.g., lactic acidosis) contribute to brain injury after shorter durations of reperfusion. In the present study, 2 h of ischemia with 30 min of reperfusion did not affect perfusion deficit or reperfusion blood flow; however, it is possible that longer reperfusion would have an effect that was not seen at this time period of reperfusion.

The effect of hyperglycemia on stroke outcome with longer reperfusion appears to be related to reperfusion blood flow and not to an effect of glucose on CBF prior to MCAO. In the studies above, there was no difference between CBF and cerebral blood volume between hyperglycemic and normoglycemic rats measured in the contralateral hemispheres [10–13]. Similarly, the present study did not measure any difference in CBF prior to MCAO using either microspheres or laser Doppler. Numerous studies have measured CBF in response to acute hyperglycemia and diabetes and have shown increased [13, 31, 32], decreased [25, 33, 34], and no change with hyperglycemia [10, 11, 26]. The discrepancy between these studies is not clear, but may relate to how hyperglycemia was induced. For example, i.p. injection of glucose was shown to decrease CBF due to a change in plasma osmolality [25]. In addition, longer periods of hyperglycemia or diabetes may have effects on capillary integrity or vascular function that is not seen with shorter durations [35].

The present study investigated the effect of hyperglycemia on penetrating arterioles before and after MCAO because these vessels are the segment most involved in lacunar strokes, a subset of stroke that appears to benefit from moderate hyperglycemia. We found that there was no effect of hyperglycemia prior to stroke on basal tone or constriction to apamin, TRAM-34, or L-NNA. After MCAO, penetrating arterioles had decreased tone to a similar level in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic conditions. In addition, tone was similarly restored in both groups by apamin, suggesting that I/R activates SK channels to decrease tone and possibly increase flow to limit the perfusion deficit. It is worth noting that although tone was diminished in penetrating arterioles after MCAO, there was still considerable tone remaining in these vessels (37–38%). In fact, two previous studies did not find any significant difference in tone in these arterioles before and after MCAO, suggesting they are more resistant to I/R than upstream MCA that have been shown to be significantly affected by MCAO [23, 24, 36]. It also appears that similar to previous studies, EDHF responsiveness is prominent and preserved in these vessels after MCAO. This is in contrast to other vasodilators such as NO that have been shown to be significantly impaired after I/R [23, 24, 37]. In the present study, constriction to L-NNA was non-significantly decreased in both normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals after MCAO, whereas constriction to apamin was significantly increased. Together, these results suggest that in penetrating arterioles, EDHF may be an important vasodilator under conditions in which NO is impaired. The prominent role of EDHF in penetrating arterioles compared to upstream vessels [23], and its preservation during I/R that can maintain CBF, may be one reason why lacunar strokes are not worsened by hyperglycemia.

Other studies have found that hyperglycemia and diabetes have a significant effect on cerebral arteries, and most find decreased endothelium-dependent vasodilator production [38, 39]. However, to our knowledge, none have specifically investigated the effect of hyperglycemia on penetrating arterioles. While we found no effect of hyperglycemia on penetrating arterioles, it is possible that more severe glucose conditions would have an effect. Worsened stroke outcome has been shown to positively correlate with the severity of glucose in cortical stroke, and while patients with lacunar stroke were shown to benefit from moderate hyperglycemia, more severe hyperglycemia (<12 mmol/L) worsened outcome [15]. Future studies are needed to determine if more severe hyperglycemia affects penetrating arterioles in a way that could worsen stroke outcome.

In addition to an effect on penetrating arteriolar tone, MCAO caused a significant increase in brain water content in both normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals. The increase in water content is likely due to vasogenic edema that occurs from blood–brain barrier disruption during reperfusion [40]. While there was no difference between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals in water content of the ipsilateral hemisphere, hyperglycemic animals had a greater increase in water compared to the contralateral side (Fig. 3). An increase in BBB disruption has been found consistently with both hyperglycemia and diabetes in stroke [35, 41, 42], and it is likely that this difference would become more pronounced with longer reperfusion.

Conclusion

In summary, we have shown that preexisiting hyperglycemia prior to MCAO did not affect CBF or penetrating arteriole function, including basal tone or constriction to apamin, TRAM-34, and L-NNA. After MCAO, penetrating arterioles from both groups of animals had diminished tone that was restored by SK/IK channel inhibition with apamin and TRAM-34, suggesting that I/R activates these channels. The effect of MCAO was not different between normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals, suggesting that this effect was due to I/R rather than hyperglycemia.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the continued support of the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke grant NS043316 and the Totman Medical Research Trust.

References

- 1.Kiers L, Davis SM, Larkins R, Hopper J, Tress B, Rossiter SC, Carlin J, Ratnaike S. Stroke topography and outcome in relation to hyperglycaemia and diabetes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:263–270. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.4.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott JF, Robinson GM, French JM, O'Connell JE, Alberti KG, Gray CS. Prevalence of admission hyperglycaemia across clinical subtypes of acute stroke. Lancet. 1999;353:376–377. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)74948-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulsinelli WA, Levy DE, Sigsbee B, Scherer P, Plum F. Increased damage after ischemic stroke in patients with hyperglycemia with or without established diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1983;74:540–544. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stead LG, Gilmore RM, Bellolio MF, Mishra S, Bhagra A, Vaidyanathan L, Decker WW, Brown RD., Jr Hyperglycemia as an independent predictor of worse outcome in non-diabetic patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10(2):181–186. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo E, Chan YW, Yu YL, Huang CY. Admission glucose level in relation to mortality and morbidity outcome in 252 stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19:185–191. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weir CJ, Murray GD, Dyker AG, Lees KR. Is hyperglycaemia an independent predictor of poor outcome after acute stroke? Results of a long term follow up study. BMJ. 1997;314:1303. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7090.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons MW, Barber PA, Desmond PM, Baird TA, Darby DG, Byrnes G, et al. Acute hyperglycemia adversely affects stroke outcome: a magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:20–28. doi: 10.1002/ana.10241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruno A, Biller J, Adams HP, Jr, Clarke WR, Woolson RF, Williams LS, et al. Acute blood glucose level and outcome from ischemic stroke. Neurology. 1999;52:280. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capes SE, Hunt D, Malmberg K, Pathak P, Gerstein HC. Stress hyperglycemia and prognosis of stroke in nondiabetic and diabetic patients: a systematic overview. Stroke. 2001;32:2426–2432. doi: 10.1161/hs1001.096194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quast MJ, Wei J, Huang NC, Brunder DG, Sell SL, Gonzalez JM, Hillman GR, Kent TA. Perfusion deficit parallels exacerbation of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in hyperglycemic rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17(5):553–559. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199705000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai N, Keep RF, Betz AL. Hyperglycemia and the vascular effects of cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 1997;28(1):149–154. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venables GS, Miller SA, Gibson G, Hardy JA, Strong AJ. The effects of hyperglycaemia on changes during reperfusion following focal cerebral ischaemia in the cat. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:663–669. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.48.7.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gisselsson L, Smith ML, Siesjö BK. Hyperglycemia and focal brain ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19(3):288–297. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199903000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martini SR, Kent TA. Hyperglycemia in acute ischemic stroke: a vascular perspective. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(3):435–451. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uyttenboogaart M, Koch MW, Stewart RE, Vroomen PC, Luijckx GJ, De Keyser J. Moderate hyperglycaemia is associated with favourable outcome in acute lacunar stroke. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 6):1626–1630. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulter G, Elting JW, De Keyser J. Increased serum neuron specific enolase concentrations in patients with hyperglycemic cortical ischemic stroke. Neurosci Lett. 1998;253:71–73. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00595-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginsberg MD, Prado R, Dietrich WD, Busto R, Watson BD. Hyperglycemia reduces the extent of cerebral infarction in rats. Stroke. 1987;18:570–574. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prado R, Ginsberg MD, Dietrich WD, Watson BD, Busto R. Hyperglycemia increases infarct size in collaterally perfused but not end-arterial vascular territories. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1988;8:186–192. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feekes JA, Cassell MD. The vascular supply of the functional compartments of the human striatum. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 8):2189–2201. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Friedman B, Lyden PD, Kleinfeld D. Penetrating arterioles are the bottleneck in the perfusion of neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:365–370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609551104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cipolla MJ, Li R, Vitullo L. Perivascular innervation of penetrating brain parenchymal arterioles. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.You J, Johnson TD, Marrelli SP, Bryan RM., Jr Functional heterogeneity of endothelial P2 purinoceptors in the cerebrovascular tree of the rat. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(3 Pt 2):H893–H900. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cipolla MJ, Smith J, Kohlmeyer MM, Godfrey JA. SKCa and IKCa Channels, myogenic tone, and vasodilator responses in middle cerebral and parenchymal arterioles: effect of ischemia and reperfusion. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1451–1457. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cipolla MJ, Bullinger LV. Reactivity of brain parenchymal arterioles after ischemia and reperfusion. Microcirculation. 2008;15(6):495–501. doi: 10.1080/10739680801986742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duckrow RB. Decreased cerebral blood flow during acute hyperglycemia. Brain Res. 1995;703(1–2):145–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li PA, Gisselsson L, Keuker J, Vogel J, Smith ML, Kuschinsky W, Siesjö BK. Hyperglycemia-exaggerated ischemic brain damage following 30 min of middle cerebral artery occlusion is not due to capillary obstruction. Brain Res. 1998;804(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00651-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannah R, Vitullo L, Cipolla MJ. Preexisting hyperglycemia during stroke is associated with enhanced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and worsened stroke outcome. FASEB J. 2005;19:A1230. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wulff H, Kolski-Andreaco A, Sankaranarayanan A, Sabatier J-M, Shakkottai V. Modulators of small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels and their therapeutic indications. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1437–1457. doi: 10.2174/092986707780831186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeish AJ, Sandow SL, Neylon CB, Chen MX, Dora KA, Garland CJ. Evidence for involvement of both IKCa and SKCa channels in hyperpolarizing responses of the rat middle cerebral artery. Stroke. 2006;37:1277–1282. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217307.71231.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andresen J, Shafi NI, Bryan RM., Jr Endothelial influences on cerebrovascular tone. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:318–327. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00937.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sieber FE, Brown PR, Wu Y, Koehler RC, Traystman RJ. Cerebral blood flow responsivity to CO2 in anesthetized chronically diabetic dogs. Am J Physiol. 1993;264(4 Pt 2):H1069–H1075. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.4.H1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grill V, Gutniak M, Björkman O, Lindqvist M, Stone-Elander S, Seitz RJ, Blomqvist G, Reichard P, Widén L. Cerebral blood flow and substrate utilization in insulin-treated diabetic subjects. Am J Physiol. 1990;258(5 Pt 1):E813–E820. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.5.E813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duckrow RB, Beard DC, Brennan RW. Regional cerebral blood flow decreases during chronic and acute hyperglycemia. Stroke. 1987;18(1):52–58. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duckrow RB. Effect of hemodilution on regional cerebral blood flow during chronic hyperglycemia in rats. Stroke. 1990;21(7):1072–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.7.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamada H, Yu F, Nito C, Chan PH. Influence of hyperglycemia on oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats: relation to blood–brain barrier dysfunction. Stroke. 2007;38(3):1044–1049. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258041.75739.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cipolla MJ, Curry AB. Middle cerebral artery function after stroke: the threshold duration of reperfusion for myogenic activity. Stroke. 2002;33(8):2094–2099. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000020712.84444.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marrelli SP, Khorovets A, Johnson TD, Childres WF, Bryan RM., Jr P2 purinoceptor-mediated dilations in the rat middle cerebral artery after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H33–H41. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujii K, Heistad DD, Faraci FM. Effect of diabetes mellitus on flow-mediated and endothelium-dependent dilatation of the rat basilar artery. Stroke. 1992;23(10):1494–1498. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.10.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayhan WG, Patel KP. Acute effects of glucose on reactivity of cerebral microcirculation: role of activation of protein kinase C. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(4 Pt 2):H1297–H1302. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.4.H1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simard JM, Kent TA, Chen M, Tarasov KV, Gerzanich V. Brain oedema in focal ischaemia: molecular pathophysiology and theoretical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(3):258–268. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayhan WG. Cerebral circulation during diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Ther. 1993;57(2–3):377–391. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90062-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ennis SR, Keep RF. Effect of sustained-mild and transient-severe hyperglycemia on ischemia-induced blood–brain barrier opening. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(9):1573–1582. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]