Introduction

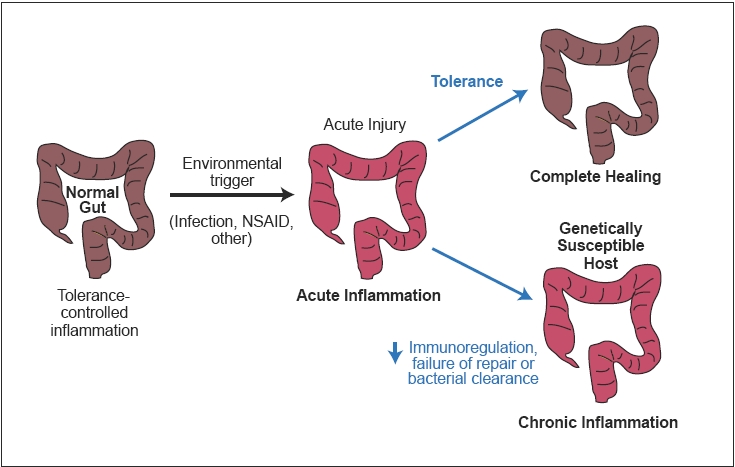

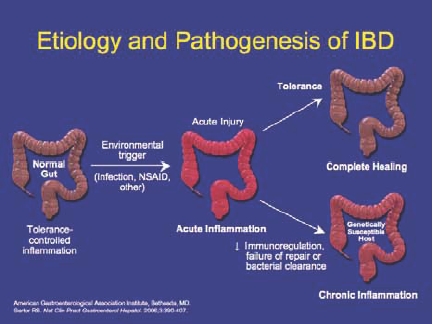

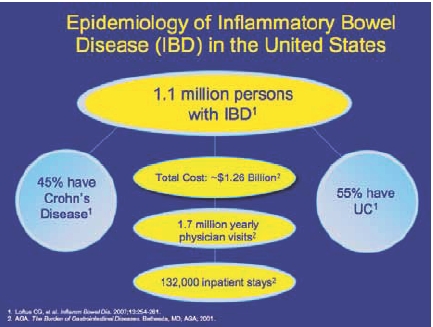

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic disease of the bowel, characterized by inflammation of the colonic mucosa. Symptoms include rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal cramping. Approximately 250,000–500,000 individuals in the United States suffer from UC, and its annual incidence ranges from 2–7 per 100,000 people.1 Although the pathophysiology of UC is not fully understood, an abnormal immune response causes chronic inflammation, which is believed to be triggered by both environmental and genetic factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Etiology and pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis.

American Gastroenterological Association Institute, Bethesda, MD.

Sartor RB. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;3:390-407.

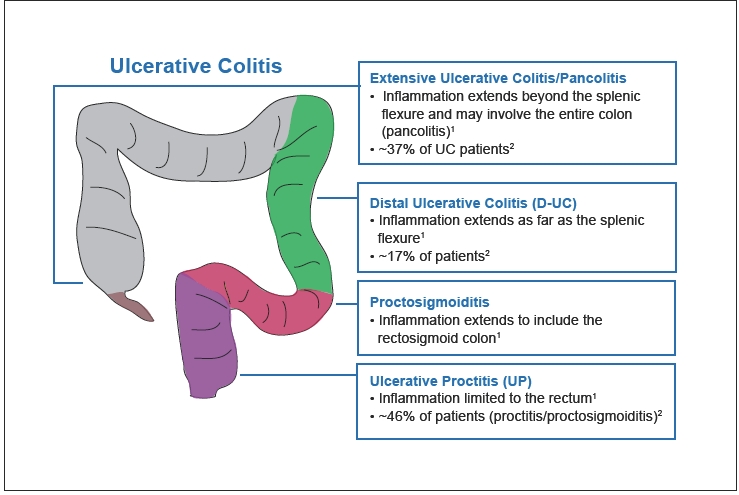

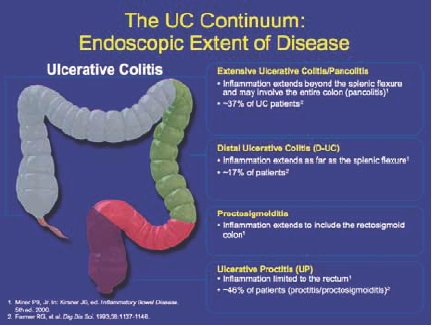

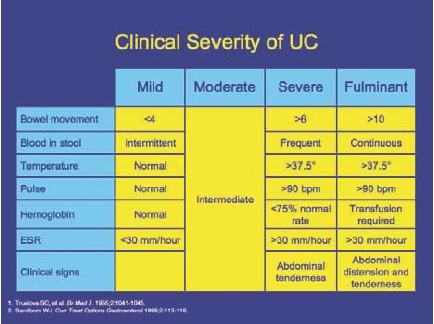

UC is categorized according to the severity of symptoms and extent of disease (Figure 2). Disease severity is defined as mild, moderate, severe, or fulminant depending on symptom severity, the number of stools per day, changes in erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and signs of toxicity.1,2 Ulcerative proctitis is defined as inflammation that is limited to the rectum, whereas proctosigmoiditis extends into the rectosigmoid colon. Together, proctitis and proctosigmoiditis affect approximately 46% of patients with UC.3 Distal UC, often referred to as “left-sided disease,” involves inflammation of the colon up to the splenic flexure and affects 17% of UC patients.3 In extensive UC, inflammation extends beyond the splenic flexure and may include the entire colon (pancolitis). Pancolitis accounts for approximately 37% of patients with UC.3 Symptoms are often correlated with the location of inflammation and can range from intermittent rectal bleeding in patients with mild proctitis, to increased urgency, tenesmus, cramps, weight loss, and colon perforation in patients with more extensive, severe disease.

Figure 2.

The ulcerative colitis continuum: endoscopic extent of disease.

1. Miner PB, Jr. In: Kirsner JB, ed. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 5th ed. 2000.

2. Farmer RG, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1137-1146.

Treatment guidelines recommend endoscopy and symptom assessment to confirm the diagnosis of UC and determine the extent and severity of the disease.2 Biopsy of the colonic mucosa may show distortion of the architecture of the mucosal crypts and the presence of increased numbers of inflammatory cells within the mucosa.

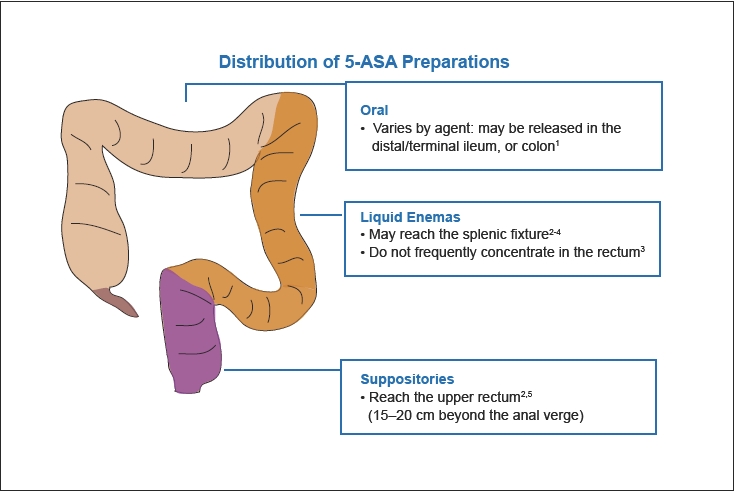

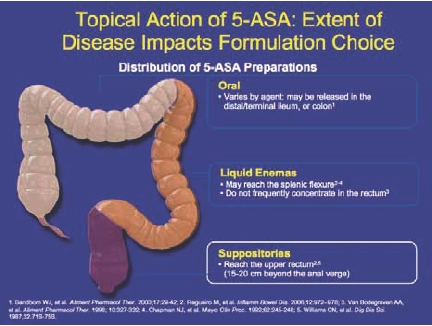

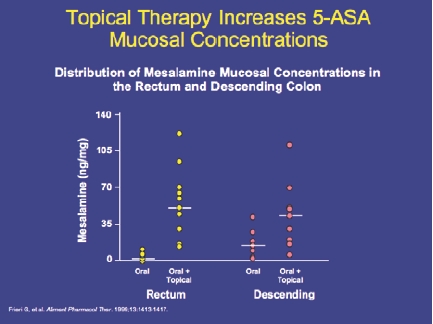

Mesalamine, or 5-aminosalycylate (5-ASA), has emerged as the first-line choice in treating mild-to-moderate UC. Oral agents are available, but most formulations require a high number of pills per day and may fail to deliver the active agent to the area of inflammation (Figure 3). Topical agents (in the form of enemas or suppositories) are considered to be more effective than oral agents in inducing remission in disease manifesting below the splenic flexure, and the combination of oral and topical agents is considered to be more effective than either alone.4 Corticosteroids are considered second-line therapy for induction of remission in distal disease that is refractory to 5-ASA but steroids are associated with high toxicity, particularly when used for longer than 3 months. The immunomodulators 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and azathioprine are recommended for patients with extensive disease, who fail to improve on 5-ASAs or steroids.

Figure 3.

Topical action of 5-ASA: extent of disease impacts formulation choice.

1. Sandborn WJ, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:29-42.

2. Regueiro M, et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:972-978.

3. Van Bodegraven AA, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:327-332.

4. Chapman NJ, et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;62:245-248.

5. Williams CN, et al. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:71S-75S.

Both oral and rectal 5-ASA formulations are used in the maintenance of remission. Steroids are not recommended for maintenance because of both lack of long-term efficacy and the risk of side effects, whereas azathioprine or 6-MP may be used in patients for whom 5-ASA therapy is not sufficient. Patients with moderate or severe refractory disease usually require hospitalization for treatment with intravenous steroids, cyclosporine or surgical resection of the colon. Some patients may be treated successfully as outpatients with anti-TNF biologic therapies or may receive this therapy with variable results as inpatients.

The following roundtable discussion was convened to discuss the latest issues in diagnosis, treatment, and induction and maintenance of remission in patients with UC and proctitis.

Roundtable Discussion

How do you discuss the differences between colitis and proctitis or proctosigmoiditis with your patients? What are the biggest challenges facing patients and physicians in distinguishing colitis, proctitis, and proctosigmoiditis?

Dr. Stephen Hanauer People do not generally understand the function of their digestive systems. We provide diagrams of the gastrointestinal tract, discuss its function, and then move on to bowel movements and the action of the sphincters. It is important to explain to patients with proctitis or colitis why they have urgency and incontinence, and the mechanisms that are involved in these symptoms. I provide a simple story to patients about the rectum and its importance in the body, and how it has the ability to sense the difference between gas and defecation. When the patient can understand how the rectum works, he or she can also begin to understand why proctitis can cause difficulties in passing gas or problems with urgency and leakage.

Dr. David Rubin And understanding this process also helps the patient understand the time needed for relief with topical versus oral medications.

SH Patients should know why the drugs work, and why eliminating inflammation allows the rectum to pass gas again. Even physicians may not understand the physiology of proctitis, particularly the fact that it is a state of constipation. Patients have urgency and frequent trips to the toilet, but they are constipated because of slow transit on the left side of the bowel. The first thing that proctitis patients report when relapsing is a change in gas. The smell of their flatus begins to change because they are becoming more constipated.

DR I discuss the rectum with every colitis patient I see. I do discuss the colon, but then I teach patients about the rectum and its job of sensing and storing waste.

SH There is confusion regarding bowel movements in general. Patients will report that they are having 20 bowel movements per day, but in truth, particularly if they have proctitis, they may make 20 trips to the toilet to pass blood and mucous, but only pass an actual stool once every three days. Inflammation also increases sensitivity. When the rectum is inflamed, it does not stretch. It is constantly going into spasm, which causes a great deal of urgency.

Dr. Daniel Present It is very common for new patients to tell me that they have UC when they actually have proctitis or proctosigmoiditis. I point out to them that it is important to make the distinction because if the inflammation does not extend upwards into the colon, there is a lower risk of cancer. There are also distinctions in insurability for patients diagnosed with colitis versus proctitis or proctosigmoiditis.

What are your treatment practices for new patients who present with ulcerative proctitis?

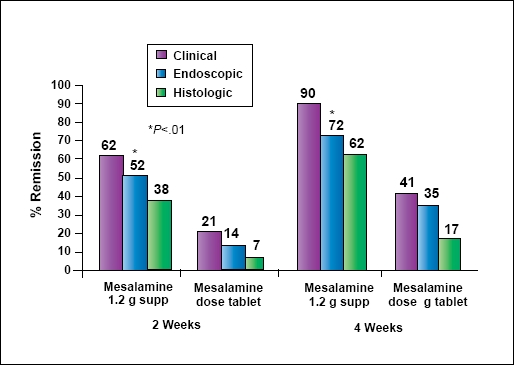

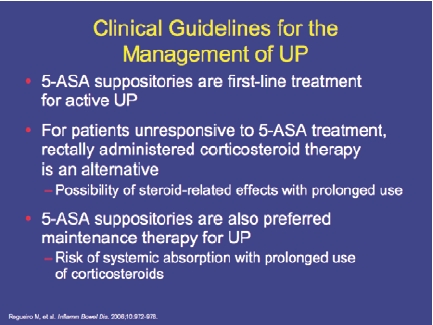

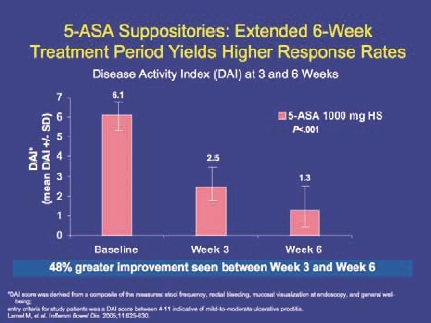

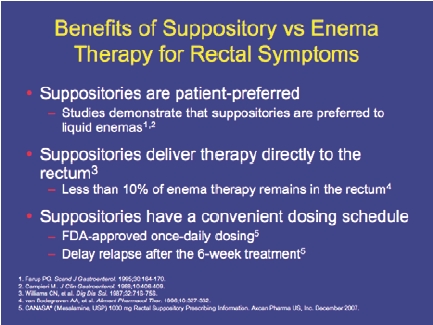

DR Rectal 5-ASA therapy is the best first-line option. However, the decision is often closely related to the education level of the patient. Patients who are educated choose to use rectal therapy because they know it is more effective in proctitis (Figure 4). They are more willing to use suppositories, adding enemas where needed to reach proctosigmoid or left-sided disease.

SH I have seen the opposite occur: patients who received enema therapy and improved proximally, but still had residual proctitis that improved with suppositories. The main point for physicians is that when patients are not responding to therapy, we need to reassess them rather than providing empiric therapy. We need to perform a flexible sigmoidoscopy exam to discover any residual disease. In some patients, the exam will show residual disease in the sigmoid colon. In other patients, it will show residual disease in the rectum of patients with established distal disease. Understanding each case will allow the physician to better target therapy according to the location of the disease.

Figure 4.

5-ASA suppositories: higher remission rates vs oral 5-ASA in ulcerative proctitis.

Gionchetti P, et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:93-97.

For new patients who present with ulcerative proctosigmoiditis, what is the first therapy that you use?

SH The drug of choice is a 5-ASA. If you apply the available evidence, the combination of oral and rectal delivery is more effective than rectal delivery alone, which is, in turn, more effective than oral delivery. However, in practice, clinical choices depend on the patient’s history and symptoms. Most patients–particularly young ones–choose to try an oral method first and avoid rectal therapies. However, if they do not respond to oral therapy and they have a lot of rectal symptoms, physicians usually recognize that topical therapy is very effective in quickly eliminating rectal symptoms.

DP In practice, I always use a combination of oral and rectal therapies. At the outset of treatment, I negotiate with the patient as to how long they will have to remain on the rectal therapy. This usually involves placing the patient on rectal medicine for two to three weeks for immediate symptom relief, then tapering it off. Although there is limited data showing that the combination of oral and rectal routes is better, I believe that it is significantly better from a clinical standpoint.

What are your treatment practices for patients who present with left-sided colitis?

DR I would use combination therapy for more extensive disease. In particular, I would use a 2.4 g oral 5-ASA plus an enema if the patient is willing to use it. If the patient is not comfortable using an enema, I would opt for a suppository. I would prescribe this combination until remission, at which point we discuss options for stopping the rectal therapy and continuing oral maintenance.

SH My approach would depend on the severity of the patient’s disease. If they had mild-to-moderate symptoms, I would probably go with oral therapy alone. Although the evidence for combination therapy is better, the issues are tolerability and adherence. All of the oral agents, whether they are conjugates or pure mesalamine, provided a good response in patients with left-sided disease and those with extensive disease. On the other hand, the combination of oral and topical therapy with 5-ASAs is better than oral therapy alone.

What is the optimal dose range of 5-ASAs for left-sided colitis?

SH As far as the dose is concerned, if the patient has mild to moderate symptoms, I usually start with 2 to 3 grams of oral 5-ASA. If the patient does not respond to this dose, I would increase the dose or add topical therapy.

DP I tend to start at higher doses. When a patient presents with mild to moderate disease, I am not sure if it will progress to moderate-to-severe or whether they will not respond to the therapy. I usually start a new patient on a higher dose of 5-ASAs: 3.6–4.8 grams, depending on severity. The higher dose allows us to improve symptoms quickly, and then lower the dose as needed. I always prescribe a combination of oral and topical agents. The use of suppository or enema depends on the patient: usually older patients will take the enemas, while younger patients will not.

DR As physicians, we always talk about dosing of oral 5-ASAs. But when you are considering the dose of medication to which you are exposing the patient, I add up the oral and rectal doses to arrive at a total. When I am discussing it with my colleagues, I might say, “Look, you are delivering 4 grams rectally and 2.4 grams orally.” Then, if the patient fails to improve on that regimen, that is helpful information for me to have.

DP I do not think about dosing that way, because of the delivery system. When you give an oral 5-ASA, a lot of it never delivers to the rectum. It sits above the rectum and waits to be passed out. So, in that case, if you pile on higher oral doses, some of the medication may get to the rectum. I would rather clinically overtreat with 5-ASAs for two to three weeks than undertreat.

SH I would say that we agree on the high-dose therapy, meaning doses up to 4.8 g daily for a majority of patients. But I think that now that we have data from several different clinical trials of different formulations and doses, we may be basing our decisions on our biased experience of seeing refractory patients. Because when you randomize untreated patients with mild disease to 2.4 g or 4.8 g, the patients with mild disease actually respond better to the lower, 2–2.4 g dose, than to the higher dose. The patients with more severe symptoms are those who have failed previous therapy, and they respond better to the higher dose.5 This has been a consistent finding with both the Multi-Matrix System (MMX) formulation and the delayed release formulations. There may be some subtle intolerance to high-dose 5-ASA in patients with mild disease.

DP Of all the patients on the MMX formulation, none had a flare-up that was longer than four weeks. So they were not the chronic patients that we tend to see in our practices.

SH I think an important point of distinction is whether you are treating a therapy-naïve patient or a refractory patient. The naïve patients do seem to respond better to lower doses, and of course the refractory patients have proven that they are not responding to those doses.

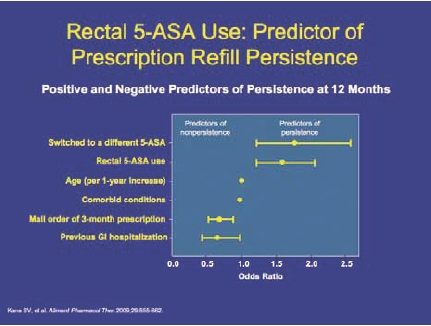

What are the main issues surrounding patient compliance in maintaining remission of UC?

DR There are many reasons why patients reduce their doses. The first is that they may inadvertently miss a dose and realize that nothing negative happened. That is a misunderstanding of the purpose of maintenance therapy. The second reason is that the patient may forget to refill their prescription, restart one week late, and notice no problems. So patients start to have a belief that maintenance therapy is optional, or that they do not need it in order to sustain some level of symptom relief. Also, many patients have a lack of understanding about the disease itself and the likelihood of relapse. And patients—especially young ones—do not acknowledge or accept that they have a chronic condition that is going to impact them for the rest of their lives.

SH I agree. When we first meet patients, we tell them that they have a chronic condition and that there is no medicine to cure it. So patients want to look beyond our knowledge. There is also a problem in physician understanding and communication. In my practice, we see many patients for second opinions who were diagnosed with colitis or proctitis, received a 6-week prescription, and never received any further instructions or follow-up. They stop therapy, begin bleeding again, and go back for another 6 weeks of treatment. Presumably these patients had not seen experienced gastroenterologists, but rather primary care physicians or colorectal surgeons who do not have a strong background in IBD or gastroenterology. But it is very common that the disease is not explained to the patients as a chronic condition for which they will need to be followed for the long term.

DR There are also the usual reasons for noncompliance: cost, forgetfulness. In many of my patients, these things happen, but I believe it is very important to acknowledge the tendency for patients to want to really understand their disease. They need to prove it to themselves a little bit before they are going to buy into what you have to say, no matter how much you try to educate them.

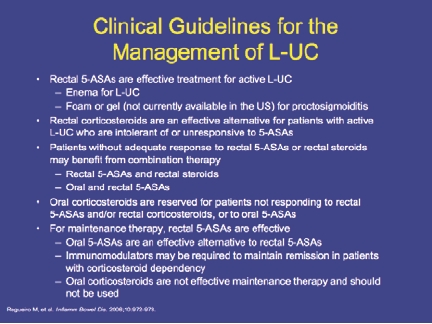

What is the role of topical steroids in the treatment of UC?

SH The evidence shows that topical 5-ASAs are superior to cortisone, budesonide, and beclomethasone.

DP 5-ASAs are superior in chronic maintenance.

SH They are also superior in induction. However, there is also evidence—not much—that the combination of a 5-ASA and a steroid is better than either alone. In one study by Mulder and colleagues,6 the combination of beclomethasone and 5-ASA enemas was found to be more effective than either alone.

SH That brings up the important data from a study by Marteau and colleagues7 that looked at colitis patients, even those with extensive colitis, and found that the addition of topical therapy was superior in inducing remission, even if patients had the disease in the upper colon. So I think we all agree that if you heal the rectum, the patient feels better, independent of the extent of colitis. Patients with Crohn’s disease can have an ileorectal anastomosis and have a normal quality of life and near-normal stooling, as long as they have a healthy rectum. So a healthy rectum is the treatment goal.

DP I see patients who are on 5-ASAs and they are not working. I switch them to topical cortisone and then use a combination, alternating days but ultimately trying to switch back to 5-ASAs alone because I believe it provides better maintenance. But many physicians do not do this. The next step for a patient who will not accept or cannot hold rectal therapy would be to try immunomodulator therapy with 6-MP or azathioprine.

Do you believe that 5-ASA therapy should continue in patients with UC or proctitis who require immunomodulators or biological agents?

SH First of all, the evidence base for immunomodulators in UC is not as robust as it is for Crohn’s disease. Nevertheless, they are part of the UC treatment guidelines from the United States,2 Great Britain,8 and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO).9 The main study10 that demonstrated the benefit of azathioprine took patients who were in remission on azathioprine and randomized them to continue or discontinue that therapy. But the majority of those patients were on 5-ASAs and they continued with their regimens, so we do not have any evidence regarding the potential benefit of 5-ASAs in that population. Similarly, the ACT 1 and ACT 2 studies11 did not randomize patients according to whether they were on 5-ASAs and receiving infliximab. However, it did not appear that any of the baseline medicines, including 5-ASAs, steroids, and immunosuppressives, affected the benefit of infliximab in patients who were not responding to the conventional therapies.

On the other hand, there are two rationales for continuing 5-ASA therapy. First, we know that it has an independent maintenance benefit from numerous trials with sulfasalazine and mesalamine, both orally and rectally, in UC. Secondly, there is a potential chemotherapeutic effect in preventing neoplasia.

DR One of the things that I have come to appreciate is the different mechanisms by which we can control disease. I have started to become a fan of combination therapies, even without as much evidence. I use this approach to provide coverage for my patients across different potential disease pathways. So, despite the lack of evidence, I have left sicker patients or those with a higher risk of neoplasia on 5-ASA therapy. Not just for chemopreventive benefit, but because I actually think there may be some other clinical benefits.

SH UC typically heals from the top to the bottom, so the rectum is often the most difficult part to heal. In patients who achieve benefit from immunosuppressants or biologics, sometimes there is residual proctitis that benefits from topical 5-ASA therapy in addition to the oral treatment, at least empirically.

Do you believe that 5-ASAs enhance the effect of azathioprine or 6-MP?

SH There are two mechanisms by which they could improve the benefit. One is the effect of 5-ASAs on the metabolism of azathiopine and 6-MP. Because mesalamine is a weak inhibitor of TPMT, there is the danger of inducing leukopenia in patients who start on a thiopurine first and then add a 5-ASA because you may be increasing levels of 6-thioguanine. Usually this is not the case: patients usually receive immunosuppressives when they are already on the 5-ASA, so it is not as perceptible of a problem. I would caution that whenever you start or stop a 5-ASA in the presence of a thiopurine, there is a potential impact on metabolism.

DR The second reason for the possible benefit of combination therapy would be additive. If they work by different mechanisms, or if they work completely alone and they add to the control of the disease, there is a benefit in some patients. But I cannot tell you how much of a benefit.

SH I agree. We learned this many years ago from our original experience using topical mesalamine. Because when we were using it originally as an enema and we followed patients prospectively, we found that as long as the enema reached the proximal extent of the colitis, the patients achieved significant benefits independent of their baseline medicine, whether or not they were on oral sulfasalazine at the time. Even if they were on oral steroids, we found that topical 5-ASA improved colitis in these patients, even if they were refractory. Of course, these findings led to comparative studies of steroids plus topical 5-ASAs.

DP In my clinical experience, the needed dose of 6-MP or azathioprine are lower than what is being used in studies and in the general population. I do not use 1.5 mg/kg, although that dosage was used in the controlled trial. In practice, the vast majority of my patients are taking 1 mg/ kg on average. I do not know if that is because I always use a combination of 5-ASA drugs. So each of my patients is different, but for maintenance of remission, you need very little of the immunomodulator if you are using it in combination with a 5-ASA.

DR When I first started my clinical practice, I was thinking in black and white terms. If someone fails therapy with a 5-ASA, the drug is off the table. Now I have started to realize that there are many shades of grey. When someone fails a 5-ASA, if they have had a partial response, there may be a benefit to adding another therapy rather than just starting from scratch with something new. Now the challenge is in figuring out how to do this more specifically.

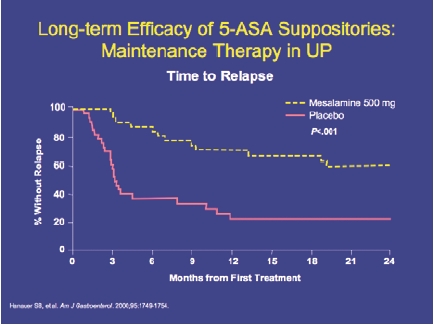

What is the role of rectal 5-ASAs in patients who have achieved remission?

SH It has been my observation that patients who require rectal therapy to get into remission typically require it to stay in remission. They need some continuation of rectal dosing, sometimes only one or two nights per week. These are patients who did not improve on oral therapy but did improve when they moved to rectal therapy. I have had difficulty in transitioning those patients back to oral therapy. Dr. Present’s hypothesis and observation has also been that oral therapy may prevent the proximal extension of distal colitis.

DP I looked at the old data that came out of the Cleveland Clinic,12 which used barium enemas. Farmer showed that, at the end of two years, approximately 10% of patients had developed disease extension. Subsequent data13 showed an even higher percentage of patients whose disease had extended. In my practice, the new patients I see always receive oral and rectal 5-ASA therapy. I tell the patient that this regimen will last for two years to prevent extension. At two years, I perform an endoscopy to see if there is real healing. If patients stay on their medication, data suggest that the disease will not extend. However, it is very difficult to get patients to stay on their medication. Once they have failed and returned to recurrent chronic disease, they are usually willing to take suppositories or enemas. Unfortunately, patients often need to go through that phase, particularly young people.

Mucosal healing has become an important endpoint in clinical trials, but does it influence your treatment of UC?

DR If I see mucosal healing, I’m happy. But the question is, should it be an incidental achievement? In other words, if I am doing a surveillance exam or I am investigating the persistence of symptoms and the mucosa is healed, I am happy and I believe it means the patient is going to be stable for some period of time. If I am doing an examination on a patient who is asymptomatic and I see that the mucosa is inflamed, I am more concerned about it. I think it is important but I do not treat to achieve it.

SH The reasons to achieve mucosal healing (above and beyond a clinical remission) are twofold. First, there is some evidence that endoscopic and histologic remission—and histologic remission means the absence of neutrophils—are associated with a prolonged duration of maintenance. The second is the recent data14,15 showing that long-standing UC inflammation is associated with an increased risk of neoplasia. Mucosal healing is desirable. The problem is the cost of healing it in a patient who is feeling well. I think most of us would accept increasing the dosage of a 5-ASA to achieve it, but few of us are willing to try a more aggressive therapy in a patient who is feeling well because of the risk of side effects with the next level of therapies (steroids or biologic agents). Other experts say that it may be worthwhile to add an immunosuppressant, but we do not have much data to suggest efficacy and safety.

DP As I interpret the data from ACT 1 and ACT 2,11 they had more patients with mucosal healing than with clinical remission, which indicates to me that mucosal healing does not have a good objective definition. I would prefer histological healing to be the definition of healing. Histologic healing takes years to achieve.

DR But you are talking about histologic normalcy as opposed to histologic recovery or healing. The absence of neutrophils is not the same as the absence of architectural distortion.

SH It used to be stated that in UC, the mucosa would heal but you would be left with some architectural distortion, even in the absence of neutrophils. I agree with Dr. Present that we are seeing more and more patients now with longstanding remissions who have both endoscopic healing and histologic normalcy after a number of years.

DR This begs the question: “Is that longstanding remission a different state of the disease, and do we treat patients differently if they have achieved it?” I am interested in developing a trial that uses histologic healing—not normalcy—as the desired endpoint. Physicians would escalate therapy based not on symptoms, but on what they find on biopsy.

SH There is some evidence out of Norway16 that showed that patients with mucosal healing had reduced risks for hospitalization, colectomy, and need for steroids.

DR That study did not define therapies a priori. The idea of a new study would be to try to define a treatment approach that succeeds in achieving mucosal healing, and compare that to a group of patients randomized to management based on symptoms.

What would it take to make mucosal healing the standard clinical endpoint in UC?

SH Several things are necessary. The first is a clear demonstration that mucosal healing makes a difference in other outcomes. We are close to having these data. However, the second need is for a surrogate endpoint that corresponds with mucosal healing, as providing endoscopy on a regular basis for every patient is impractical. Calprotectin is a potential marker, but it has not been standardized or validated to correlate with mucosal healing per se. Rather, it discriminates between inflammation and non-inflammation.

What are the most important developments in terms of molecular markers of cancer in UC patients?

SH We have known for many years that visible or pathologic dysplasia tend to occur in a field of the colon where there are aneuploid changes. At IOIBD, I presented some data from one of our investigators who is looking at gene chip profiling in the mucosa in patients with UC, low-grade dysplasia, and polyps or cancer. We were able to identify more than 20 genes that are upregulated in patients who have dysplasia in and around the lesion. We do not know which genes promote transformation to neoplasia, but our technology is improving, and we must factor that in when we think about future detection.

How do infections such as cytomegalovirus and C. difficile factor into your treatment of UC?

DP I have many patients who do not respond to anything. Before we send the patient in for surgery, we always do a biopsy to rule out cytomegalovirus (CMV). If the patient is not very symptomatic and is not in a rush to go to surgery, I give an empiric course of vancomycin, because I think there is more C. difficile than we are detecting. In several cases, patients have had conflicting results on tests to detect C. difficile. I wonder whether many refractory UC patients are actually positive for either CMV or C. difficile. When C. difficile is superimposed on active UC, the patient usually ends up undergoing surgery.

DR Our experience is the same. In one month that we measured this phenomenon in our practice, 50% of our hospitalized patients either had C. difficile on admission or were found to have it while they were in the hospital. There is also a group of patients who appear to have moderate UC without pseudomembranes after a stool study and endoscopic study. It does not appear to be C. difficile, but the stool sample tests positive.

SH It is becoming more difficult for me to tell the difference between UC and C. difficile endoscopically.

DR If a patient receives antibiotics and they develop C. difficile, does that lead them to IBD? There is anecdotal evidence of this phenomenon, certainly for the patient who presents with an acute or chronic case of diarrhea.

DP More commonly, C. difficile leads to irritable bowel syndrome rather than IBD.

What are the current issues regarding the prevention and treatment of post-surgical recurrence of UC?

DP I believe it is important to distinguish among pouchitis, irritable pouch, cuffitis, and Crohn’s disease in the inflow tract. When a patient presents with symptoms after a pouch procedure, physicians must consider all of these issues. Patients should be fully evaluated. Physicians should perform endoscopy and know what they are looking for. Shen and colleagues17,18 have offered guidelines for diagnosis of post-operative conditions based on bleeding and other parameters. They have been using 5-ASA suppositories for cuffitis treatment.19 In my practice, we have used these as well, with good success.

Do you believe that 5-ASAs work in pouchitis?

DR No.

DP I agree. I have not had any success with this. There have been very few controlled trials on the treatment of pouchitis.20 Current studies are examining the use of tinidazole as a prophylaxis.

What are the current treatment approaches for radiation proctitis?

DP We are not seeing much radiation proctitis any more, with the better machinery that our radiotherapists are using. When it was more common, the standard treatment was with 5-ASA suppositories. Many patients were also treated with these as a prophylaxis before they even developed proctitis.

DR Yes, many patients who received radiation therapy for cervical, prostate, or rectal cancer developed acute proctosigmoiditis, which rarely came to the attention of a gastroenterologist. Radiation oncologists were treating it themselves because they anticipated it as an inflammatory process that was a side effect of their therapy. Some patients developed radiation proctopathy later, with vascular ectasias and more problems. So there have been several studies investigating 5-ASA therapy during radiation exposure to limit the acute proctosigmoiditis. One of the more recent prospective and placebo-controlled studies21 showed a benefit of oral 5-ASA therapy in reducing that acute problem, but we do not know if it can reduce the subsequent radiation proctopathy and vascular ectasias.

SH That later phase can appear 10 to 20 years after radiation therapy.

DR Yes, they do not yet have the follow-up for those individuals. But it is enough to say that 5-ASA therapy should be administered to patients before and during their radiation treatments.

Biographies

Slide Library

For a free electronic download of these slides, please direct your browser to the following web address: http://www.clinicaladvances.com/index.php/our_publications/gastro_hep-issue/gh_June_2009/

Emerging Issues in Ulcerative Colitis and Ulcerative Proctitis: Individualizing Treatment to Maximize Outcomes

CME Post-Test: Circle the correct answer for each question below.

-

In the United States, the incidence of UC is: ___ per 100,000 people per year:

2–7

8–12

1

13–17

-

Proctitis and proctosigmoiditis affect approximately___% of patients with UC:

26

36

46

56

-

According to Dr. Hanauer, what is the definition of histologic remission?

absence of architectural distortion in the mucosa

absence of neutrophils

absence of basilar lymphoid aggregates

absence of crypt abcesses

-

According to Dr. Hanauer, what is the first sign that a patient with proctitis is in relapse?

change in smell of flatus

increased urgency in defecating

blood in stool

more frequent stool

-

What is the first-line therapy recommended for ulcerative proctosigmoiditis?

oral 5-ASAs

rectal 5-ASAs

IV infliximab

combination of oral and rectal 5-ASAs

-

According to data from the Cleveland Clinic, what percentage of UC patients developed disease extension after 2 years?

6%

10%

15%

18%

-

According to Dr. Rubin, what would be an ideal endpoint to use in a future trial of treatments for UC?

Mucosal healing

histologic healing

mucosal normalcy

symptom relief

-

According to Dr. Present, the dose of 5-ASA and 6-MP used in practice is ____ than the doses used in clinical trials:

lower

higher

equal to

-

Why should 5-ASAs be provided before and during radiation treatment for cervical, prostate, or rectal cancer?

to treat underlying UC

to prevent extension of UC

to prevent radiation proctitis

to make radiation more effective

-

5-ASA therapy is considered to be effective in treating pouchitis.

True

False

Evaluation Form Emerging Issues in Ulcerative Colitis and Ulcerative Proctitis: Individualizing Treatment to Maximize Outcomes

To assist us in evaluating the effectiveness of this activity and to make recommendations for future educational offerings, please take a few minutes to complete this evaluation form. You must complete this evaluation form to receive acknowledgment for completing this activity.

Please answer the following questions by circling the appropriate rating: 1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

Extent to Which Program Activities Met the Identified Objectives

| After completing this activity, I am now better able to: | |||||

| 1. Describe the different physiologic manifestations of ulcerative colitis, proctitis, and proctosigmoiditis. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. Outline the use of different formulations of oral and topical mesalamine in the treatment of these disease states. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. Describe therapy options for patients with mild-to-moderate disease that is refractory to mesalamine treatment. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Overall Effectiveness of the Activity

| The content presented: | |||||

| Was timely and will influence how I practice | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Enhanced my current knowledge base | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Addressed my most pressing questions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Provided new ideas or information I expect to use | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Addressed competencies identified by my specialty | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Avoided commercial bias or influence | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Impact of the Activity

Name one thing you intend to change in your practice as a result of completing this activity.

________________________________________________________________________________

Please list any topics you would like to see addressed in future educational activities.

________________________________________________________________________________

Additional comments about this activity. _________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________

Follow-up

As part of our continuous quality improvement effort, we conduct postactivity follow-up surveys to assess the impact of our educational interventions on professional practice. Please indicate if you would be willing to participate in such a survey:

Yes, I would be interested in participating in a follow-up survey.

Yes, I would be interested in participating in a follow-up survey.

No, I’m not interested in participating in a follow-up survey.

No, I’m not interested in participating in a follow-up survey.

If you wish to receive acknowledgment for completing for this activity, please complete the post-test by selecting the best answer to each question, complete this evaluation verification of participation, and fax to: (303) 790-4876.

Post-test Answer Key

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Request for Credit

Name ____________________________ Degree __________________________________

Organization ____________________________________ Specialty ___________________________________

Address ___________________________________________________________________________________

City, State, Zip ______________________________________________________________________

Telephone ___________________ Fax ________________________________ E-mail ____________________________________

Signature ________________________________________ Date ________________

For Physicians Only:

I certify my actual time spent to complete this educational activity to be: ______________________

I participated in the entire activity and claim 1.0 credits. I participated in the entire activity and claim 1.0 credits. |

I participated in only part of the activity and claim _____ credits. I participated in only part of the activity and claim _____ credits. |

Footnotes

Supported through an educational grant from Axcan Pharma.

Sponsored by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest:Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) assesses conflict of interest with its instructors, planners, managers, and other individuals who are in a position to control the content of CME activities. All relevant conflicts of interest that are identified are thoroughly vetted by PIM for fair balance, scientific objectivity of studies utilized in this activity, and patient care recommendations. PIM is committed to providing its learners with high-quality CME activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in healthcare and not a specific proprietary business interest of a commercial interest.

The faculty reported the following financial relationships or relation-ships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Stephen B. Hanauer, MD: Dr. Hanauer discloses the following. Consulting fees: Axcan Pharma, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma.

Daniel H. Present, MD: Dr. Present discloses the following. Grant/Research support: Abbott Laboratories, Alaven, Centocor, Inc., Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Mayo Clinic, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, National Institutes of Health (University of Pennsylvania), Tech Lab, Teva Pharmaceuticals, USA, UCB, Inc. Consultant/Scientific advisor: Abbott Laboratories, Alaven, Axcan Pharma, Centocor, Inc., Elan Pharmaceuticals, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Salix Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Inc. Speaker’s bureau: Axcan Pharma, Elan Pharmaceuticals, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Shire Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Inc.

David T. Rubin, MD: Dr. Rubin discloses the following. Consulting fees: Shire Pharmaceuticals, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Axcan Pharma, Centocor, Inc. Grant support: Salix Pharmaceuticals, Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals.

The following planners and managers, Linda Graham, RN, BSN, BA, Jan Hixon, RN, BSN, MA, Trace Hutchison, PharmD, Julia Kirkwood, RN, BSN and Jan Schultz, RN, MSN, CCMEP hereby state that they or their spouse/life partner do not have any financial relationships or relationships to products or devices with any commercial interest related to the content of this activity of any amount during the past 12 months.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use:This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM), Gastroenterology & Hepatology, and Axcan Pharma, do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications.

The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of PIM, Gastro-Hep Communications, or Axcan Pharma. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

Disclaimer:Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patient’s conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer’s product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

Funding for this clinical roundtable summary has been provided through an educational grant from Axcan Pharma. Support of this monograph does not imply the supporter’s agreement with the views expressed herein. Every effort has been made to ensure that drug usage and other information are presented accurately; however, the ultimate responsibility rests with the prescribing physician. Gastro-Hep Communications, Inc., the supporter, and the participants shall not be held responsible for errors or for any consequences arising from the use of information contained herein. Readers are strongly urged to consult any relevant primary literature. No claims or endorsements are made for any drug or compound at present under clinical investigation.

Contributor Information

Stephen B. Hanauer, Professor of Medicine and Clinical Pharmacology Director, Section of Gastroenterology and Nutrition University of Chicago.

Daniel H. Present, Professor of Medicine Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

David T. Rubin, Associate Professor of Medicine Co-Director, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center University of Chicago.

References

- 1.Loftus EV, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, et al. Ulcerative colitis in Olmstead county, Minnesota, 1940-1993: Incidence, prevalence and survival. Gut. 2000;46:336–343. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.3.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornbluth A, Sachar B. Ulcerative Colitis Practice Guidelines in Adults (Update): American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1371–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farmer RG, Easley KA, Rankin GB. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1137–1146. doi: 10.1007/BF01295733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safdi M, DeMicco M, Sninsky C, et al. A double-blind comparison of oral versus rectal mesalamine versus combination therapy in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1867–1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA, Sandborn WJ, et al. MMX mesalazine for the induction of mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis: efficacy and tolerability in specific patient subpopulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;1:1094–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulder CJ, Fockens P, Meijer JW, et al. Beclomethasone dipropionate (3Mg) versus 5-aminosalycylic acid (2g) versus the combination of both (3 mg/2 g) as retention enemas in active ulcerative proctitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:549–553. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marteau P, Probert CS, Lindgren S, et al. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalazine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54:960–965. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.060103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SPL, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl V):v1–v16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.043372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis SPL, Stange EF, Lémann M, et al. European evidence-based consensus on the management of ulcerative colitis: current management. Gut. 2006;55(Suppl I):i16–i35. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.081950b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawthorne AB, Logan RF, Hawkey CJ, et al. Randomised controlled trial of azathioprine withdrawal in ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 1992;305:20–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6844.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis N Engl J Med. 2005. 353 2462 2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farmer RG. Long-term prognosis for patients with ulcerative proctosigmoiditis (ulcerative colitis confined to the rectum and sigmoid colon) J Clin Gastroenterol. 1979;1:47–50. doi: 10.1097/00004836-197903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farmer RG. Clinical patterns, natural history, and progression of ulcerative colitis. A long-term follow-up of 1116 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1137–1146. doi: 10.1007/BF01295733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huo D, Rothe JA, Rubin DT, et al. Increased inflammatory activity is an independent risk factor for dysplasia and colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a case-control analysis with blinded prospective pathology review. 2006 May;:20–25. Oral presentation at Digestive Disease Week. Los Angeles, CA. Abstract 14. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, et al. Cancer surveillance in long-standing ulcerative colitis: endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut. 2004;53:11813–1816. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.038505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen B, Remzi FH, Lavery IC, et al. A proposed classification of ileal pouch disorders and associated complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen B, Lashner B. Diagnosis and treatment of ileal pouch diseases in patients with underlying ulcerative colitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s11938-006-0019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen B, Lashner BA, Bennett AE, et al. Treatment of rectal cuff inflammation (cuffitis) in patients with ulcerative colitis following restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1527–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maser EA, Present DH. Pouch-ouch. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:70–74. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f2dfa3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahraus CD, Bettenhausen D, Malik U, et al. Prevention of acute radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis by balsalazide: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial in prostate cancer patients. In J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1483–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]