Abstract

Mesalamine (5-aminosalicylic acid; 5-ASA) represents the cornerstone of first-line therapy for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis (UC). Current guidelines suggest that the combination of oral and rectal therapies provide optimal symptom resolution and effectively maintain remission in the majority of these patients. Although effective, most oral 5-ASA formulations have a high pill burden and rectal therapies are associated with low adherence. Recent research has examined patterns of compliance, as well as the efficacy of different dose levels of 5-ASA in terms of symptom resolution, the maintenance of remission, and improvements in quality of life. The ASCEND I, II, and III trials found that doses of 4.8 g/day are more effective than 2.4 g/day doses in patients with moderate disease, those with previous steroid use, and those with a history of multiple medications. The benefits of effective long-term 5-ASA therapy include the avoidance of more costly and potentially toxic drugs (such as corticosteroids and biologic therapies), as well as improvements in quality of life, reductions in the need for future colectomy, and a lower risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Current Treatment Landscape of Mild-to-Moderate

5-ASA Efficacy

According to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) treatment guidelines, ulcerative colitis (UC) is classified as mild in patients who have fewer than 4 bowel movements daily with minimal bleeding and no significant urgency or abdominal pain.1 Studies that have compared 2.4 g and 4.8 g doses of mesalamine have determined that patients with mild disease will improve just as readily on lower doses as on higher doses.2 For moderate disease, defined as 4–6 daily bowel movements with greater urgency and tenesmus,1 patients do tend to improve more readily on the 4.8 g/day dose.3,4

The optimal number of doses per day for treating mild-to-moderate UC is an area of some discussion. The first available 5-ASA formulation, sulfasalazine, was first given in the early 1950s and required division into multiple daily doses because of the risk for adverse events such as nausea and headache. The multiple daily dosing strategy carried over into the development of subsequent 5-ASA therapies, and questions remain as to whether once-daily dosing is as effective as twice-daily dosing in the initial induction phase of therapy. Currently, two oral therapies are approved for once-daily administration (one for induction of remission and one for maintenance). However, empiric practitioner evidence suggest that all current 5-ASA formulations may be administered effectively in a once-daily regimen. It appears that taking the prescribed medication regularly is more important than dividing the doses.

Importantly, mucosal healing has been documented with 5-ASA therapy, even though the trial endpoints to prove this have varied considerably among the different studies. The goal of induction therapy for UC should be to resolve UC patients' symptoms as quickly as possible. Swift and successful induction of clinical remission encourages patient trust of their physician and is important in fostering a functional long-term relationship for the effective treatment of this chronic disease. With this in mind, an anxious patient with moderately active disease should be started on a combination of oral and topical medications. However, this regimen needs to be adjusted for the realistic needs of each patient's situation. For college students living in a dormitory environment, nightly enemas are not feasible. Patients who travel 3 or more days per week for work may need to take enemas for fewer days per week or take them on weekends only. For these patients, oral therapy alone will induce remission, but it may do so more slowly. Overall, 5-ASAs have been proven to achieve remission in approximately 70% of UC patients.1

In clinical practice, disease extent is not as important as symptom severity when making treatment decisions. Although it is true that patients with proctitis or left-sided disease will most likely gain benefit from topical therapy, in reality, most patients prefer oral therapy. I begin by prescribing combination therapy in the hopes that eventually remission can be maintained with oral therapy only. There are patients who will continue to need enemas or suppositories once or twice weekly to maintain remission and when these individuals realize that rectal therapy can make the difference between asymptomatic remission and symptomatic flares, they are usually happy to comply.

Patient Relation Strategies to Improve 5-ASA Adherence

It is important to consult with patients frequently at the beginning of therapy. In my practice, I usually schedule an appointment approximately 2 weeks after the initiation of therapy, and then again at the three-month point. This juncture is crucial because three months is often the point at which patients will begin to forget drug therapy, or purposely interrupt their regimen. Over the first several years, I will see patients every 6 months and eventually drop down to annual visits if treatment is going well. It is crucial that physicians do a better job of explaining the importance of adherence. For each patient, we must find an effective way to communicate that continuous drug therapy is important. When I treat young people who are distracted by their cell phones, I suggest that they use the phone to set an alarm. They can choose the time of day that is most convenient to take their medication, then set the alarm to remind themselves on a daily basis.

As discussed later in his section, Dr. Seymour Katz recommends that patients stay on the same dose of 5-ASA that allowed them to achieve remission for maintenance. This is an area of ongoing investigation, particularly if the patient started with 4.8 g daily. My preference is to try and lower the dose gradually if the patient has had a solid remission without inflammation for over a year.

Alternatives to 5-ASA Therapy

Physicians often move their patients to corticosteroids almost immediately after oral 5-ASAs fail to resolve bleeding, urgency, or tenesmus symptoms. We should try to convince the patients that these medications may take up to 4 weeks to work. However, long-term steroid use carries a high risk of adverse events.1 Although moon facies and acne are mostly reversible, these can be devastating side effects for a young, single individual. In addition, it is not beneficial to plant the seed in a patient that steroids are the only effective option for them. I will frequently emphasize the severe adverse effects of osteonecrosis, osteoporosis, hypertension, and cataracts to help persuade the patient and family to give their treatment time to work. Furthermore, many physicians believe that if steroids are used to induce remission, it is unlikely that 5-ASAs will maintain remission effectively. This may not be true in the case of patients who have been prematurely switched to steroid therapy without an adequately long enough course of appropriate doses of 5-ASA products, including combination oral and topical therapy if necessary.

The immunosuppressives azathioprine and 6-MP are effective,5 but they have an even slower onset of action than 5-ASAs. However, these agents do appear to work, even though the evidence in UC is not as strong as it is with Crohn's disease. In the long term, these agents increase patients' baseline risk of lymphoma by up to four times.1 As with all medicine, the risks versus the benefits of any individual therapy in terms of efficacy and quality of life must be discussed fully with the patient and family. Methotrexate is more commonly considered in the treatment of Crohn's disease, but it also has efficacy in UC.6 Methotrexate has a faster onset of action than other therapies, but has not been studied extensively in UC.

Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents such as infliximab and adalimumab represent the newest additions to the UC arsenal.7,8 There is excellent published trial evidence that infliximab is effective in inducing improvement in 70% of patients. The other 2 agents have not submitted data on efficacy in UC at this time. They work quickly, and are effective in achieving and maintaining remission as well as inducing mucosal healing. However, they are expensive agents with unknown long-term safety profiles. There is some evidence that they may increase the incidence of certain neoplasms, including the lymphoma that we see with azathioprine and 6-MP.

References

- 1.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults (update): American College of Gastroenterology. Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1371–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Dallaire C, Archambault A, Yacyshyn B, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablets) compared to 2.4 g/day (400 mg tablets) for the treatment of mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: The ASCEND I trial. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:827–834. doi: 10.1155/2007/862917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandborn WJ, Regula J, Feagan BG, Belousova E, Jojic N, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800-mg tablet) is effective for patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1934–1943. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA, Sandborn WJ, et al. MMX mesalazine for the induction of mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis: efficacy and tolerability in specific patient subpopulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;1:1094–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gisbert JP, Linares PM, McNicholl AG, Mate J, Gomollon F. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of azathioprine and mercaptopurine in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:126–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Matary W, Vandermeer B, Griffiths AM. Methotrexate for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD007560. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007560.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afif W, Leighton JA, Hanauer SB, Loftus EV, Jr, Faubion WA, et al. Open-label study of adalimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis including those with prior loss of response or intolerance to infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1302–1307. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Challenges in Effective 5-ASA Administration

The classic symptoms of UC include diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and hematochezia. These symptoms remind patients to be adherent with medical therapy, and normally patients do comply better with therapy during active disease periods. However, during the maintenance phase, adherence drops considerably. In a study by Kane and colleagues,1 researchers examined pharmacy refill records for 94 patients with clinically quiescent UC who were prescribed maintenance doses of mesalamine. After analyzing 6 months' worth of refill data, the investigators found that only 40% of patients were adherent to drug therapy (defined as the consumption of at least 80% of dispensed drug supply). The study showed that male gender, the use of multiple concomitant medications, and single status were significantly associated with lower drug adherence. This community-based study produced much lower rates of compliance than has been found in clinical trials, where patients are under more strict supervision. It is not surprising that compliance is low among patients in remission: without the daily reminder for the need for medication—in the form of troubling symptoms—patients tend to feel comfortable and begin to skip doses, particularly those that are normally taken in the middle of the day.

Lowering Pill Burden and Optimizing Daily Regimens

Pill burden is another important consideration in adherence. If an individual is mandated to take medication on a 4-times daily (QID) basis, the chances are that they will be less likely to adhere to therapy. In an important adherence review by Claxton and colleagues,2 the researchers identified 76 studies across a range of diseases where compliance was measured using electronic monitoring. They found that dose-taking compliance declined as the number of daily doses increased: the mean compliance rate for QID dosing was only 51%, while the rate for once-daily dosing was 79% (P<.001 among dose schedules).

The use of multiple daily dosing in UC was originally based on the pharmacokinetics of sulfasalazine, where peaks and troughs occurred quickly. The QID dosing schedule for this drug was difficult for patients to follow, but since it was the only regimen available at the time, it set the standard for UC care. However, sulfasalazine had a host of other drawbacks in addition to the need for multiple dosing. With sulfasalazine, 30% of patients experienced adverse events and 50% stopped medical therapy. Twenty percent of the 5-ASA in sulfasalazine was absorbed systemically and excreted in the urine.

In 1977, Azad Khan and colleagues3 discovered that the active moiety of sulfasalazine was 5-ASA, and since then, multiple 5-ASA agents have been developed. When delayed-release mesalamine was developed, it offered three-times-daily (TID) dosing. Because the majority of individuals tolerate mesalamine extremely well, it is the first drug used in mild-to-moderate disease, and it serves as the cornerstone of the armamentarium for UC.

There are currently several mesalamine formulations that are designed with once-daily administration, including MMX mesalamine, which is approved for induction therapy, and extended-release mesalamine granules, which are approved for maintenance therapy. The QDIEM Study4 recently compared once-daily and twice daily dosing of delayed-release mesalamine as maintenance therapy for 1,023 patients with UC in remission. Sandborn and colleagues found that once-daily dosing was as effective as twice-daily dosing for maintenance therapy, and patients on both regimens had low rates of withdrawals due to adverse events, implying that many, if not all, mesalamine formulations can be effectively dosed once daily.

Long-Term Benefits of Improved Adherence

When counseling patients, there are several benefits to adherence that should be emphasized. The first is that medication will eradicate active symptoms. In addition, it is important to discuss the effect of drug therapy on lowering the risk of colorectal cancer. Velayos and colleagues5 were among the first researchers to perform a meta-analysis examining the role of 5-ASA therapy in reducing cancer or dysplasia among patients with UC. They analyzed 9 studies, enrolling a total of 1,932 subjects. The researchers found a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 0.51 for the protective association between 5-ASA use and colorectal cancer (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.37–0.69), and the same OR for the combined endpoint of colorectal cancer and dysplasia (95% CI: 0.38–0.69).

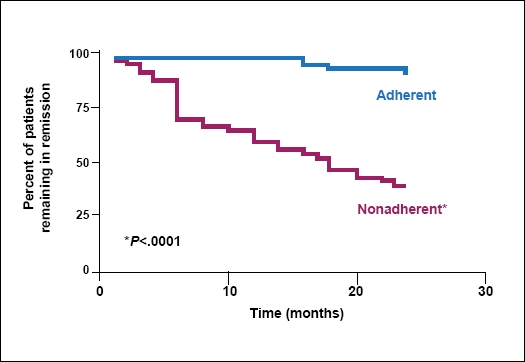

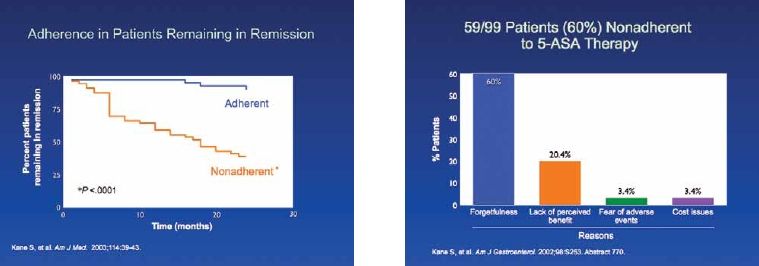

Another key benefit to maintenance therapy is that patients are much more likely to relapse if they stop taking their prescribed medication. Kane and colleagues6 followed 99 patients who had UC in remission for at least 6 months. The researchers assessed patients for adherence (defined as refilling at least 80% of prescribed medication) and for disease recurrence at 6, 12, and 24 months. They found that patients who were not adherent with medication had more than a five-fold risk of recurrence than adherent patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adherence in patients remaining in remission.

Adapted from Kane S, et al. Am J Med. 2003;114:39-43.

Patients who maintain remission also have reduced risks of hospitalization and surgery. A study by Frøslie and associates7 enrolled 740 patients newly diagnosed with UC or Crohn's disease between 1990 and 1994. The researchers performed clinical and endoscopic evaluations on each patient at 1 year and 5 years, and analyzed the impact of mucosal healing on a variety of factors. They found that mucosal healing was significantly associated with less inflammation (P=.02), less of a need for steroid use (P=.02), and a lower risk of future colectomy(P=.02).

5-ASA-Refractory/Steroid-Dependent Disease

It is important to optimize 5-ASA therapy, whether it involves maximizing the dose of oral therapy or adding a topical agent. If symptoms fail to improve on optimized mesalamine therapy, physicians often contemplate the addition of corticosteroids. Steroids work rapidly and are relatively safe in the short term. However, corticosteroids are well recognized to have significant potential problems and many patience develop steroid dependence. In a natural history study of steroid use conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota, which followed 173 patients with CD and 185 patients with UC, rates of steroid-dependence after 1 year of treatment were 28% among CD patients and 22% among UC patients.8

Osteonecrosis is a rare but serious complication of steroid therapy. It is characterized by the death of bone cells and can lead to cortical decompression or hip replacement. In a study by Vakil and colleagues,9 7 (4.3%) of 161 patients developed this complication over a 10-year follow-up period of corticosteroid treatment for inflammatory bowel disease. The mean duration of steroid treatment was 42 weeks, and surgery for the disease was required in 4 of the 7 patients. Osteoporosis is another potential side effect of corticosteroid use,10 and can lead to fractures and significant pain, morbidity, and mortality. The National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study11 found that the cosmetic side effects of moon face, acne, and striae occurred at alarming rates in patients on steroid therapy, in 47%, 30%, and 6% of patients, respectively. Whereas moon face and acne can be resolved, striae can only be removed with plastic surgery.

For patients refractory to conventional 5-ASA therapy, it is tempting to try a first-pass, rapidly metabolized steroid such as budesonide. However, a placebo-controlled study by Lindgren and colleagues12 found only nonsignificant decreases in relapse rates for patients receiving budesonide enemas versus those receiving placebo enemas. Overall, budesonide has not been embraced as an accepted therapy for UC. There are several novel agents under investigation, but it is too early to gauge their usefulness.

References

- 1.Kane SV, Cohen RD, Aikens JE, et al. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2929–2933. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azad Khan AK, Piris J, Truelove SC. An experiment to determine the active therapeutic moiety of sulphasalazine. Lancet. 1977;2:892–895. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandborn WJ, Kane SV, Korzenik JR, et al. Once daily dosing of delayed-release oral mesalamine (400 mg tablet) is as effective as twice daily dosing for maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis: results of the QDIEM Study. Oct, 2009. pp. 23–28. Presentation at the American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting. San Diego, California. Abstract 39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Velayos FS, Terdiman JP, Walsh JM. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1345–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kane SV, Huo D, Aikens J. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, et al. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faubion WA, Jr, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a popula-tion-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255–260. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vakil N, Sparberg M. Steroid-related osteonecrosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:62–67. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90764-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults (update): American College of Gastroenterology. Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(7):1371–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singleton JW, Law DH, Kelley ML, Jr, et al. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: adverse reactions to study drugs. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:870–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindgren S, Lofberg R, Bergholm L, et al. Effect of budesonide enema on remission and relapse rate in distal ulcerative colitis and proctitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:705–710. doi: 10.1080/00365520212512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Utilizing Higher 5-ASA Concentrations to Improve Efficacy

ASCEND I-III Trials

5-ASA therapy has a well-documented history of preventing relapse in UC and several older studies have supported the use of permanent maintenance therapy at dose levels of up to 4.8 g/day.1 Most recently, the ASCEND trials investigated the dose-response effect of 5-ASA therapy in the induction and maintenance of remission. In ASCEND I,2 301 patients with mild-to-moderate disease were given either 2.4 g/day or 4.8 g/day of delayed-release oral mesalamine. The primary endpoint was overall improvement, which was defined as either complete remission or a response to therapy at week 6. Among all study participants, 51% of patients who received the lower dose experienced improvement, compared with 56% of those who received the higher dose, which was not a statistically significant difference. However, when results were stratified by disease severity, the researchers found that patients with moderate disease had a more substantial dose response than the overall study population. In the moderate disease subgroup, 57% of patients achieved treatment success with the 2.4 g/day dose, compared with 72% who received the 4.8 g/day dose (P=.0384). Thus, patients with more severe disease benefitted much more from higher doses than from lower ones.

The ASCEND II3 trial focused solely on patients with moderately active UC. The trial enrolled 386 patients who were randomized to receive the same doses as in ASCEND I, and the same endpoints were used. The trial confirmed that the higher dose is more effective than the lower dose in these patients: 72% achieved treatment success at week 6 at the higher dose, compared with 59% at the lower dose (P=.036). The investigators concluded that patients with moderate UC were significantly more likely to achieve success when they received 4.8 g/day than when they received 2.4 g/day of mesalamine.

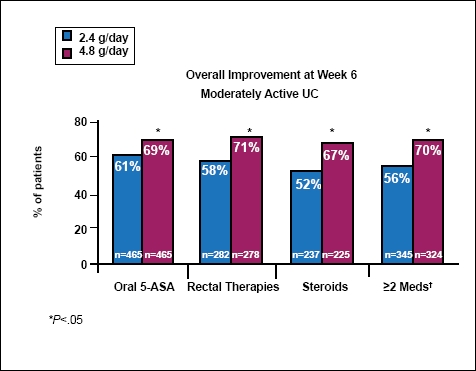

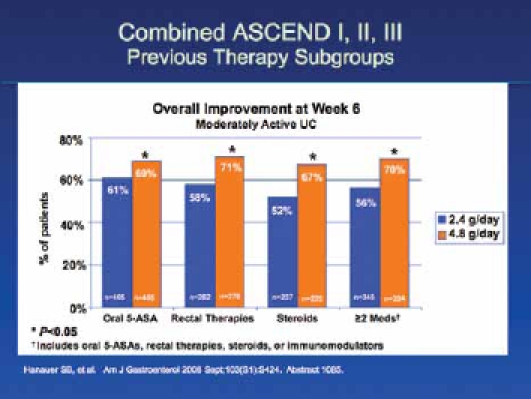

In ASCEND III,4 772 patients with moderate UC were randomized to receive 2.4 g/day versus 4.8 g/day doses of mesalamine, and there was no statistically significant difference between the higher and lower dose regimens in terms of overall improvement. Whereas 70% of patients at the higher dose level achieved success, 66% of patients did at the lower dose. However, in a subgroup analysis, the researchers found that patients with difficult-to-treat disease responded better to higher doses than to lower doses. Difficult-to-treat patients included those previously treated with corticosteroids, oral 5-ASAs, rectal therapies, or other UC medications, as well as those receiving multiple medications simultaneously. The results from ASCEND III are meaningful for those of us in clinical practice, as these difficult-to-treat patients are often the ones that we see most frequently in our offices. This is a very important subgroup that benefits from higher doses, and a longer duration of therapy, in order to enter remission (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Previous therapy subgroups of combined ASCEND I, II, and III trials.

†Includes oral 5-ASAs, rectal therapies, steroids, or immunomodulators.

One delayed-release mesalamine HD 800 mg tablet has not been shown to be bioequivalent to 2 delayed-release mesalamine 400 mg tablets.

Adapted from Hanauer SB, et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(S1):S424. Abstract 1085.

It is important to consider the definitions of overall improvement that were included in the ASCEND trials. Overall improvement was based on the Physician's Global Assessment, which includes the parameters of rectal bleeding, stool frequency, a sigmoidoscopy score, and a clinical assessment. A patient functional assessment score was also used, which involved patient-reported assessments of symptoms. Overall, the researchers found that the 4.8 g/day dose was noninferior to the 2.4 g/day dose.

When Dr. Lichtenstein pooled the data from the ASCEND trials,5 he focused on the results for improvements in stool frequency and rectal bleeding. In this analysis, improvement was considered a decrease from baseline of more than one point, and clinical remission was defined as a score of 0 for stool frequency and bleeding. In all, his analysis included 1,220 patients, 618 of whom received 2.4 g/day of mesalamine and 602 who received a 4.8 g/day dose. At 3 weeks of treatment, a slightly higher percentage of high-dose patients had improvements in rectal bleeding: 76% of patients on the higher dose improved, compared with 72% on the lower dose. However, for the symptom of stool frequency, 73% of patients on higher doses experienced improvements, versus 64% of those on the lower doses (P=.003). There was also a small but measurable difference in remission rates for the 2 dose groups: 25% in the higher-dose group achieved remission, compared with 20% in the lower-dose group. At 6 weeks, the 4.8 g/day group also had more improvement in rectal bleeding: 83% achieved improvement, compared with 79% in the 2.4 g/ day group. While the different doses appeared to produce similar response rates for the original endpoints, this analysis showed that there are some discernible differences for specific symptoms at different dosing levels. In 2007, when trials of Multi Matrix (MMX) mesalamine were published,6,7 the authors found no significant differences in response rates for 2.4 g/day doses and 4.8 g/day doses. However, it is important to note that these results were not broken out into disease severity or treatment history analyses.

In 2008, Irvine and colleagues examined the effect of mesalamine on the quality of life (QoL) of UC patients by analyzing the combined results of ASCEND I and ASCEND II.8 They found that mesalamine improved QOL significantly across dose levels, with a mean increase of 29.6 and 39.7 points on the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) at 3 and 6 weeks, respectively (P<.0001). They found that QoL improvements were greater for patients with moderate disease than for those with mild disease.

Other Dose-Response Considerations

In an effort to further understand the impact of UC on patients' QoL, we surveyed 772 patients, 51% of whom had experienced 3 to 10 disease flares in the preceding 2 years.9 We found that, among QoL factors, UC had the greatest impact on patients' personal life, with 55% of respondents reporting a moderate or severe impact. For 49% of participants, UC had a moderate/severe impact on work life, and 39% of patients reported that UC had a moderate/severe impact on interactions with friends and family members. This study highlighted the need to provide support systems for patients, so we not only treat the symptoms of UC, but help patients contend with the strain that this disease places on their lives. In my practice, I am impressed by the incidence of depression among my UC patients. It is extremely important to address depression and other QoL concerns in clinical practice.

Although guidelines recommend the use of 5-ASAs at doses up to 4.8 g/day before switching to second-line therapies,10 many physicians tend to dismiss 5-ASA therapy before reaching maximum recommended dosing. In a recent study, we tracked the use of 5-ASA therapy before the initiation of immunosuppressant therapy in 2,599 patients with UC.11 We determined the most recent dose of delayed-release mesalamine that was filled prior to each patient's first dose of immunosuppressive therapy. Among all patients, the mean daily dose of delayed-release mesalamine was 3.48 g/day before switching to immunosuppressant therapy. However, 39% of all patients followed had been taking mesalamine at a most recent daily dose of 2.4 g/day or lower. These findings highlight the need to optimize 5-ASA therapy, with higher doses and longer durations of therapy, before moving on to more risky and costly drugs. I recommend that physicians provide the highest doses of 5-ASA therapy for at least 12 weeks before giving up on these agents, unless symptoms become truly unbearable before the end of that period.

One of the main problems in current treatment practices for UC is that physicians work very hard at attaining remission, but are they are less willing to work with patients to maintain remission. Kane and colleagues12 provided data showing that if patients do not adhere to maintenance therapy, they will relapse. In my practice, I recommend high-dose, maintenance therapy, because of the general principal that whatever puts a patient into remission will keep him/ her in remission.

Another key component to the UC treatment plan is the addition of rectal 5-ASA therapies. Although compliance can be very poor with topical therapies, there is a large body of evidence to show that the use of combination therapy provides a faster induction of remission than oral therapies alone.13-15 Often, quick results can be provided with the daily use of a 1-g mesalamine enema.

Although the need for it seems obvious, many physicians lack a system for tracking UC patients who are in remission. In my experience, the most effective way to maintain remission is to see patients in the office and have a direct conversation with them. Because patients often stop therapy when they begin to feel better, postcards and phone calls from nurse practitioners are simply not enough to encourage adherence. In addition, treating physicians should keep themselves up-to-date on the latest studies to support their suggestions for drug therapy, as IBD patients tend to be extremely well-educated on the available research and require convincing arguments in order to follow physician directives.

References

- 1.Sachar DB. Maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. J Clin Gastreonterol. 1995;20:117–122. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199503000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Dallaire C, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8g/ day (800 mg tablets) compared with 2.4 g/day (400 mg tablets) for the treatment of mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: the ASCEND I trial. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:827–834. doi: 10.1155/2007/862917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanauer SB. Delayed-release oral mesalamine at 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablet) for the treatment of moderately active ulcerative colitis: the ASCEND II trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2478–2485. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sandborn WJ, Regula J, Feagan BG, et al. Delayed-release oral mesalamine 4.8 g/ day (800 mg tablet) is effective for patients with moderately active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1934–1943. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein GR. Poster presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. San Diego, CA. 2009 Oct;:23–28. Poster # 306. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamm MA, Sandborn WH, Gassull M, et al. Once-daily, high-concentration MMX mesalamine in active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:66–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA, Boddu P, et al. Effect of once- or twice-daily MMX mesalamine (SPD476) for the induction of remission of mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irvine EJ, Yeh CH, Ramsey D, et al. The effect of mesalazine therapy on quality of life in patients with mildy and moderately active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:1278–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz S, Hershberger M. Patient Perceptions of the Impact of Ulcerative Colitis in Daily Life. 2009. Oct, pp. 23–28. Presentation at the 74th American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting, San Diego, California. Abstract 1184.

- 10.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults (update): American College of Gastroenterology. Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(7):1371–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz S, Pasquale M. Daily dosing of delayed release mesalamine prior to immunosuppressive use. 2009. Oct, pp. 23–28. Presentation at the 74th American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting, San Diego, California. Abstract 1199.

- 12.Kane SV, Huo D, Aikens J. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng SC, Kamm MA. Therapeutic strategies for the management of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:935–50. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safdi M, DeMicco M, Sninsky C, et al. A double-blind comparison of oral versus rectal mesalamine versus combination therapy in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1867–1871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marteau P, Probert CS, Lindgren S, et al. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalazine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut. 2005;54:960–965. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.060103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biographies

Slide Library

For a free electronic download of these slides, please direct your browser to the following web address: http://www.clinicaladvances.com/index.php/our_publications/gastro_hep-issue/gh_february_2010/

Notes

5-ASA Dose-Response: Maximizing Efficacy and Adherence

CME Post-Test: Circle the correct answer for each question below.

-

According to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) treatment guidelines, ulcerative colitis (UC) is classified as mild in patients who have fewer than __ bowel movements per day with minimal bleeding and no urgency or abdominal pain.

4

6

2

3

-

True or false? The immunomodulators azathioprine and 6-MP are effective, with a faster onset of action than 5-ASAs.

True

False

-

According to Dr. Safdi, ___ months is the crucial point at which UC patients discontinue maintenance therapy for UC.

6

3

2

9

-

In a review by Claxton and colleagues that examined compliance patterns across a variety of disease states, what was the mean compliance rate for QID dosing?

79%

37%

51%

43%

-

True or false? Kane and colleagues found that patients who were not adherent with medication had more than a five-fold risk of UC recurrence than adherent patients.

True

False

-

Yearly monitoring of BUN/creatinine should be performed on patients taking 5-ASA to look for what complication?

Interstitial nephritis

Severe dehydration

Congestive heart failure

Hepatitis

-

In ASCEND I, which UC patient group was found to have a significant dose response to higher doses of delayed-release oral mesalamine?

Patients with mild UC

Patients with bloody stools but no urgency upon defecation

Patients with moderately active UC

Patients with high quality of life scores

-

In ASCEND III, difficult-to-treat patients were defined as:

Highly nonadherent patients

Patients with the most severe symptoms

Patients with a history of depression

Those previously treated with UC therapies

-

True or false? Studies of Multi Matrix System mesalamine found a strong dose response at 4.8 g/day for the entire patient cohort.

True

False

-

Dr. Katz recommends high doses of 5-ASA for how many weeks before moving on to alternate therapies?

12

16

8

6

Evaluation Form 5-ASA Dose-Response: Maximizing Efficacy and Adherence

PIM is committed to excellence in continuing education, and your opinions are critical to us in this effort. To assist us in evaluating the effectiveness of this activity and to make recommendations for future educational offerings, please take a few minutes to complete this evaluation form. You must complete this evaluation form to receive acknowledgment for completing this activity.

Please rate your level of agreement by circling the appropriate rating:

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

Learning Objectives

After participating this activity, I am now better able to:

| 1. Describe the current unmet needs in the use of 5-ASA therapy for mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. Summarize the latest research on dose-response to higher concentrations of 5-ASA drug and its efficacy. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. Discuss the importance of achieving and sustaining remission and the effect of this goal on long-term outcomes. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. Review methods to ensure patient adherence. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Based upon your participation in this activity, choose the statement(s) that apply:

I gained new strategies/skills/information that I can apply to my area of practice.

I gained new strategies/skills/information that I can apply to my area of practice.

I plan to implement new strategies/skills/information into my practice.

I plan to implement new strategies/skills/information into my practice.

What strategies/changes do you plan to implement into your practice? ________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________

What barriers do you see to making a change in your practice? ______________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Which of the following best describes the impact of this activity on your performance?

I will implement the information in my area of practice.

I will implement the information in my area of practice.

I need more information before I can change my practice behavior.

I need more information before I can change my practice behavior.

This activity will not change my practice, as my current practice is consistent with the information presented.

This activity will not change my practice, as my current practice is consistent with the information presented.

This activity will not change my practice, as I do not agree with the information presented.

This activity will not change my practice, as I do not agree with the information presented.

Please rate your level of agreement by circling the appropriate rating:

1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neutral 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree

The content presented:

| Enhanced my current knowledge base | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Addressed my most pressing questions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Promoted improvements or quality in health care | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Was scientifically rigorous and evidence-based | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Avoided commercial bias or influence | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Would you be willing to participate in a post-activity follow-up survey?

Yes

Yes  No

No

Please list any topics you would like to see addressed in future educational activities:_________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________

If you wish to receive acknowledgment for completing for this activity, please complete the post-test by selecting the best answer to each question, complete this evaluation verification of participation, and fax to: (303) 790-4876.

Post-test Answer Key

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Request for Credit

Name __________________________________ Degree _____________________________________

Organization _____________________________________ Specialty _____________________________________

Address _____________________________________________________________________________

City, State, Zip _________________________________________________________________________

Telephone _________________________ Fax __________________________ E-mail _____________________________________

Signature _____________________________________ Date ______________________

For Physicians Only: I certify my actual time spent to complete this educational activity to be: ______

I participated in the entire activity and claim 1.0 credits.

I participated in the entire activity and claim 1.0 credits.

I participated in only part of the activity and claim _____ credits.

I participated in only part of the activity and claim _____ credits.

Project ID: 6699

Footnotes

Supported through an educational grant from Warner Chilcott.

Sponsored by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest:Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM) assesses conflict of interest with its instructors, planners, managers, and other individuals who are in a position to control the content of CME activities. All relevant conflicts of interest that are identified are thoroughly vetted by PIM for fair balance, scientific objectivity of studies utilized in this activity, and patient care recommendations. PIM is committed to providing its learners with highquality CME activities and related materials that promote improvements or quality in healthcare and not a specific proprietary business interest of a commercial interest.

The faculty reported the following financial relationships or relationships to products or devices they or their spouse/life partner have with commercial interests related to the content of this CME activity:

Seymour Katz, MD: Dr. Katz discloses the following. Consultant/Scientific Advisor: Procter & Gamble Co., Abbott Laboratories, UCB, Inc. Research/ Clinical Trial Support: Procter & Gamble Co., Abbott Laboratories, Pfizer Inc., Elan Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers-Squibb Co., Hutchison Medi- Pharma Limited, Otsuka, Prometheus Laboratories, Eisai Pharmaceuticals, Millennium Pharma. Speakers' Bureau: Procter & Gamble Co., Abbott Laboratories, UCB, Inc.

Gary R. Lichtenstein, MD: Dr. Lichtenstein discloses the following. Consultant, research: Abbott Corporation, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Inc, Ferring, Procter & Gamble, Prometheus Laboratories, Inc, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Shire Pharmaceuticals, UCB. Research: Astra-Zeneca, Inc, Millenium Pharmaceuticals. Consultant: Elan, Schering-Plough Corporation, Wyeth.

Michael A. Safdi, MD: Dr. Safdi discloses the following. Consultant: Procter & Gamble, Centocor, Shire. Contracted research: Procter & Gamble, Centocor, Abbott Laboratories, Shire, UCB, Inc.

The following planners and managers, Linda Graham, RN, BSN, BA, Jan Hixon, RN, BSN, MA, Trace Hutchison, PharmD, Julia Kirkwood, RN, BSN and Jan Schultz, RN, MSN, CCMEP hereby state that they or their spouse/life partner do not have any financial relationships or relationships to products or devices with any commercial interest related to the content of this activity of any amount during the past 12 months.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use:Disclosure of Unlabeled Use: This educational activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not indicated by the FDA. Postgraduate Institute for Medicine (PIM), Gastroenterology & Hepatology, and Warner Chilcott do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications.

The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of PIM, Gastro-Hep Communications, or Warner Chilcott. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

Disclaimer:Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any procedures, medications, or other courses of diagnosis or treatment discussed or suggested in this activity should not be used by clinicians without evaluation of their patient's conditions and possible contraindications or dangers in use, review of any applicable manufacturer's product information, and comparison with recommendations of other authorities.

Funding for this Clinical Roundtable Monograph has been provided through an educational grant from Warner Chilcott. Support of this monograph does not imply the supporter's agreement with the views expressed herein. Every effort has been made to ensure that drug usage and other information are presented accurately; however, the ultimate responsibility rests with the prescribing physician. Gastro-Hep Communications, Inc., the supporter, and the participants shall not be held responsible for errors or for any consequences arising from the use of information contained herein. Readers are strongly urged to consult any relevant primary literature. No claims or endorsements are made for any drug or compound at present under clinical investigation.

Contributor Information

Seymour Katz, Clinical Professor, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York.

Gary R Lichtenstein, Director, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Program, Professor of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Michael A Safdi, Ohio Gastroenterology & Liver Institute Cincinnati, Ohio.