Abstract

Iron overload can cause insulin deficiency, but in some cases this may be insufficient to result in diabetes. We hypothesized that the protective effects of decreased iron would be more significant with increased β-cell demand and stress. Therefore, we treated the ob/ob mouse model of type 2 diabetes with an iron-restricted diet (35 mg/kg iron) or with an oral iron chelator. Control mice were fed normal chow containing 500 mg/kg iron. Neither treatment resulted in iron deficiency or anemia. The low-iron diet significantly ameliorated diabetes in the mice. The effect was long lasting and reversible. Ob/ob mice on the low-iron diet exhibited significant increases in insulin sensitivity and β-cell function, consistent with the phenotype in mouse models of hereditary iron overload. The effects were not accounted for by changes in weight or feeding behavior. Treatment with iron chelation had a more dramatic effect, allowing the ob/ob mice to maintain normal glucose tolerance for at least 10.5 wk despite no effect on weight. Although dietary iron restriction preserved β-cell function in ob/ob mice fed a high-fat diet, the effects on overall glucose levels were less apparent due to a loss of the beneficial effects of iron on insulin sensitivity. Beneficial effects of iron restriction were minimal in wild-type mice on normal chow but were apparent in mice on high-fat diets. We conclude that, even at “normal” levels, iron exerts detrimental effects on β-cell function that are reversible with dietary restriction or pharmacotherapy.

Keywords: insulin secretion, type 2 diabetes

we have reported previously that adult humans with iron overload from hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) have a high prevalence of diabetes (22%) and impaired glucose tolerance (31%) (29). The impaired glucose tolerance of HH is associated with decreased insulin secretory capacity (29). A mouse model of HH with targeted deletion of the gene most commonly mutated in hemochromatosis, Hfe, shares the same phenotype (7). In humans, the impaired insulin secretory capacity is reversed with phlebotomy therapy (1).

Increased iron stores are also significantly associated with typical type 2 diabetes (reviewed in Ref. 10). In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey cohort, the odds ratios for newly diagnosed diabetes were 4.94 for men and 3.61 for women who had elevated serum ferritin levels compared with those with normal ferritin (14). A more recent study shows an even higher relative risk, 7.4-fold (15), comparable in magnitude with the risk engendered by obesity (25). The increased diabetes risk in the general population is not accounted for by hemochromatosis (13). Similar relationships between iron and diabetes risk are seen in several other populations, including Europeans, African-Americans, gestational diabetics, prediabetics, and individuals with transfusional iron overload (2, 22, 26, 34, 35, 37). Iron has similar associations with other aspects of the metabolic syndrome (16, 20, 21, 31).

Conversely, low iron stores are associated with a lower risk of diabetes. In relatively small and/or short-term studies of non-HH subjects, phlebotomy improved insulin sensitivity and glycemia in both nondiabetic subjects (8) and type 2 diabetics with high ferritin (11). These results are concordant with rat studies in which animals with iron deficiency anemia are more insulin sensitive than controls (5). Phlebotomy in iron-overloaded individuals also improves hypertriglyceridemia (4), vascular reactivity (12), and markers of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (9).

The phenotype related to iron overload in HH differs from that caused by pure dietary iron excess. This is likely based upon the differing tissue distributions of iron in HH vs. dietary excess, which are based on the dysregulation of the iron channel ferroportin in HH (24, 36). Although HH is associated with decreased insulin secretory capacity, the insulin deficiency is compensated partially by increased insulin sensitivity both in humans (29) and the mouse model (7). However, iron overload in the general non-HH population is associated with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. This suggests that iron may have complex and multiple effects on metabolism and diabetes risk. We have shown, for example, that in pancreatic β-cells excess iron impairs mitochondrial function and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (7, 23, 29). High levels of iron in skeletal muscle, on the other hand, favor fatty acid oxidation through a mechanism dependent on AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) resulting in protection from obesity and insulin resistance when mice are fed a high-fat diet (Ref. 19 and Huang J and McClain D, unpublished observations). Finally, high levels of iron in adipose tissue downregulate serum adiponectin (Huang J and McClain D, unpublished observations), which would be predicted to increase diabetes risk. Thus, the integrated effect of iron on metabolism is mediated by complex tissue-specific effects that are both pro- and antidiabetic and that vary both with environmental (diet) and genetic influences.

We hypothesized that the effects of iron on β-cell function would be most evident when the demand on insulin secretion is greatest. For example, in an obese animal the risk of β-cell failure is high, and under these conditions the role of iron could be unmasked. Therefore, we used a mouse model of type 2 diabetes, the ob/ob (Lep−/−), exposed to a low-iron diet or iron chelators to modulate iron exposure. Consistent with our hypothesis, we find that this low-iron diet in the ob/ob mouse protects against the development of diabetes. Even more dramatic results are seen with pharmacological treatment using an iron chelation. The reduced levels of iron sufficient to induce protection do not result in anemia. The protective effect is reversible with a resumption of a normal iron diet. Finally, the effect of low iron is mediated by beneficial effects on both insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals.

Leptin-deficient ob/ob mice bred on the C57BL/6J genetic background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Five diets were used during the course of this study. Mice were routinely maintained in our animal facility on high-carbohydrate normal chow with an iron content ranging from 350 to 600 mg/kg (8656; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI). We also used defined high-carbohydrate diets with very low iron (4–6 mg/kg, TD 80396; Harlan Teklad), 35 mg/kg iron (TD TD94045; Harlan Teklad), and 500 mg/kg iron (TD04404; Harlan Teklad). The high-fat diet containing 45 kcal% as fat and 35–50 mg/kg iron (D12451; Research Diets) was supplemented with carbonyl iron to create a higher-iron, high-fat diet. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Utah.

Iron chelator treatment.

Mice were treated with FBS0701 (FerroKin BioSciences, San Carlos, CA), a magnesium salt of (S)-3́-(OH)-DADFT polyether iron chelator (3). Drug was dosed at 10 mg/kg, provided once a day, mixed in 100 mg of peanut butter. Controls received peanut butter alone.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing and insulin determination in vivo.

Experimental animals were fasted for 6 h, after which time glucose (1 g/kg body wt) was administered intraperitoneally to nonsedated animals. Tail vein blood (3 μl) was sampled for glucose determination (Glucometer Elite; Bayer, Tarrytown, NY) before and 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after glucose administration. Tail vein blood (50 μl) was also collected before and 30 min after the start of the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) for insulin determination using the Sensitive Rat Insulin Kit (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO). Homeostasis model assessments were calculated as described (28).

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption.

Oxygen consumption in cardiac muscle mitochondria was measured using a fiber-optic oxygen sensor (Ocean Optics, Orlando, FL) (6). Cardiac muscle tissue was suspended in 2.0 ml of 120 mM KCl, 3 mM HEPES, 5 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mg/ml free fatty acid BSA, pH 7.2. Respiration was measured at 25°C in a sealed glass chamber. Oxygen consumption was measured with 5 mM glutamate plus 2 mM malate as substrates, in the basal state (state 2), following the addition of 1 mM ADP (state 3), and in the presence of 1 μg/ml oligomycin to block ATP synthesis (state 4). Respiratory control ratios are the ratio of states 3 and 4.

Indirect calorimetry.

Mice were studied for 3 consecutive days in a four-chamber open-circuit Oxymas system (Comprehensive Laboratory Animal Monitoring System; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) to measure oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production.

Statistical procedures.

Descriptive statistics are represented as average ± SE. The Student t-test (2-tailed) was used to compare differences between groups. ANCOVA was used to test whether two regression lines represented independent populations.

RESULTS

Prevention of diabetes in ob/ob mice by a low-iron diet, independent of changes in weight.

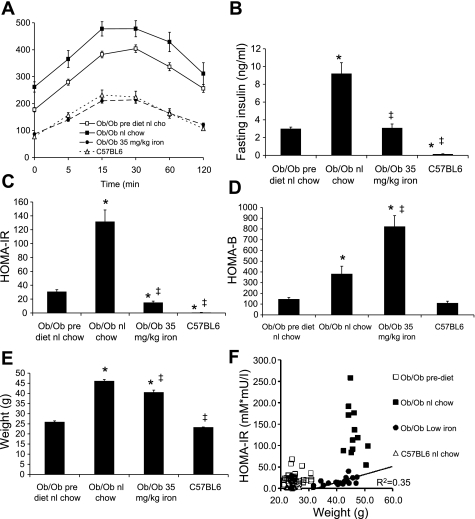

We fed ob/ob mice chow containing either 35 or 500 mg/kg iron, the latter being “normal” chow. Ob/ob mice were fed normal chow containing 500 mg/kg iron until 4–6 wk of age, at which time they were either maintained on that diet or given a chow containing 35 mg/kg iron. At the time of the change in diet, most of the mice had already developed diabetes. At the time of initiation of these diets, the mice were given an IPGTT. They were distributed into the test groups such that the areas under the glucose curve (AUCG) were equivalent between the groups at the start of the test period. After 4 wk, the IPGTT was repeated. The glucose tolerance of the group on normal chow (95% carbohydrate and 500 mg/kg iron) had worsened significantly, whereas the group on the 35 mg/kg iron diet (also 95% carbohydrate) had normal glucose tolerance, better than at the beginning of the study and equivalent to the wild-type background strain, C57BL6 (Fig. 1A). The glucose values at each time point (Fig. 1A) and the AUCG (not shown) were all significantly different between the pretest results and after 1 mo of either normal chow (higher glucose values and AUCG, P < 0.0001) or low-iron chow (lower glucose and AUCG, P < 0.0001). Fasting hyperinsulinemia was seen in all of the ob/ob mice compared with the wild-type C57BL6 mice, but whereas the ob/ob mice on normal chow approximately tripled their insulin levels from 30 to 60 days, the mice on low iron maintained the same insulin levels as at the start of the study (Fig. 1B). The results in Fig. 1, A and B, were reflected in significantly improved insulin resistance indices in the low-iron diet group, as assessed by the homeostasis model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), compared with both ob/ob mice on normal chow and their own levels at the start of the low-iron diet (Fig. 1C). After 30 days on the 500 mg/kg normal iron chow, the insulin resistance had resulted in a compensatory increase in insulin secretion measured as an increase in β-cell function assessed by the homeostasis model (HOMA-B) (P < 0.001; Fig. 1D). HOMA-B was even greater in the ob/ob mice on low iron (P < 0.01 compared with normal chow, P < 0.0001 compared with prediet).

Fig. 1.

Glucose tolerance and weights in mice fed normal (nl) chow or a low-iron diet. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing was performed on ob/ob mice on nl chow at age 4–6 wk, after which time they were maintained on that diet or placed on a lower-iron diet (35 mg/kg). The mice were retested 4 wk later. Wild-type C57BL6 mice, the background strain of the ob/ob mice, were also tested at the same age, 8–10 wk. A: results of intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing. B: fasting insulin levels. C: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). D: homeostasis model assessment of β-cell function (HOMA-B). E: weights of the mice at the 2nd glucose tolerance test. F: values for HOMA-IR were plotted as a function of weight for the individual mice studied. The relation of HOMA-IR to weight for the ob/ob mice on low iron was significant (r2 = 0.35, P = 0.006), but there was no such relationship for the ob/ob mice on higher iron. Shown are means ± SE; n = 12–20/group. In A, all glucose values differ significantly among the 3 groups of ob/ob mice; P < 0.001. In B and C, *P < 0.01 compared with prediet levels in the ob/ob mice on normal chow; ‡P < 0.01 compared with ob/ob mice on normal chow.

We also assessed the ability of a diet even lower in iron (2–6 mg/kg) to protect ob/ob mice from diabetes. On this diet, the AUCG during IPGTT was significantly better than in the mice on normal chow but was slightly inferior to that observed on the 35 mg/kg diet (AUCG 35 ± 9% higher on the very low-iron diet compared with 35 mg/kg, P < 0.05; data not shown). In addition, the mice on the very low-iron diet became mildly anemic (Table 1), so the very low-iron diet was not studied further. Importantly, however, mice on the 35 mg/kg iron diet did not exhibit significant changes in hematocrit or red blood cell indices compared with mice on the 500 mg/kg iron diet (Table 1). The mice on the 35 mg/kg diet did exhibit a 43% decrease in hepatic iron (P < 0.05) and a 12% decrease in serum ferritin (P < 0.05) compared with mice on the 500 mg/kg diet (Table 1). The effects of iron on glucose tolerance are not attributable to changes in insulin clearance, since the ratio of C-peptide to insulin did not change as a function of iron (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of dietary iron content on red blood cells and serum chemistries in ob/ob mice

| Dietary Iron Content, mg/kg |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2–6 | 35 | 500 | |

| Hematocrit, % | 47.7 ± 0.9* | 54.6 ± 3.1 | 54.2 ± 1.3 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 17.1 ± 0.5† | 17.8 ± 0.6 | 19.0 ± 0.1 |

| Mean corpuscular volume, fl | 50.2 ± 0.17 | 51.0 ± 0.8 | 51.9 ± 0.4 |

| Hepatic iron, mmol/mg protein | 2.4 ± 0.5* | 7.4 ± 0.8† | 13.0 ± 1.8 |

| Serum ferritin, mg/l | ND | 0.90 ± 0.12† | 1.02 ± 0.03 |

| Serum adiponectin | ND | 9.4 ± 1.0 | 8.6 ± 0.7 |

| Serum triglycerides, mg/dl | ND | 59 ± 6† | 98 ± 4 |

| Free fatty acids, mM | ND | 57.6 ± 5.9 | 73.0 ± 8.1 |

| C-peptide/insulin ratio | ND | 1.75 ± 0.54 | 1.27 ± 0.46 |

Results are means ± SE; n = 6–8 mice/group. ND, not determined. At 30 days of age, mice were placed on normal chow (low fat) containing the indicated concentrations of iron. After 60–90 days, blood was taken for analysis.

P < 0.05 compared with 35 and 500 mg/kg diets;

P < 0.05 compared with 500 mg/kg diet.

In this study, the ob/ob mice on low iron gained slightly less weight than the mice on normal chow, but they remained significantly obese compared with the wild-type C57BL6 mice (Fig. 1E). Because body weight is a major determinant of glucose tolerance status, we investigated whether those differences in weight might account for their improved glucose tolerance. This was not the case (Fig. 1F). The average HOMA-IR value for the cohort of ob/ob mice on low iron within the weight range of 40–45 g (17.4 ± 2.3) differed significantly from that of the ob/ob mice on normal chow within that same weight range (142.5 ± 25.1, P < 0.0001). The correlation of HOMA-IR to weight was significant for the ob/ob mice on low iron (r2 = 0.35, P < 0.01), whereas the correlation was not significant for the ob/ob mice on normal chow.

Improved serum triglyceride and fatty acid levels in ob/ob mice with dietary iron restriction.

Consistent with the improved diabetic status of the ob/ob mice on lower iron diets, the mice on 35 mg/kg chow also exhibited a 40% decrease in serum triglycerides (P < 0.01) and a trend toward lower serum free fatty acid levels (20%, P = 0.13; Table 1).

Time course and reversibility of effects of dietary iron on glucose tolerance.

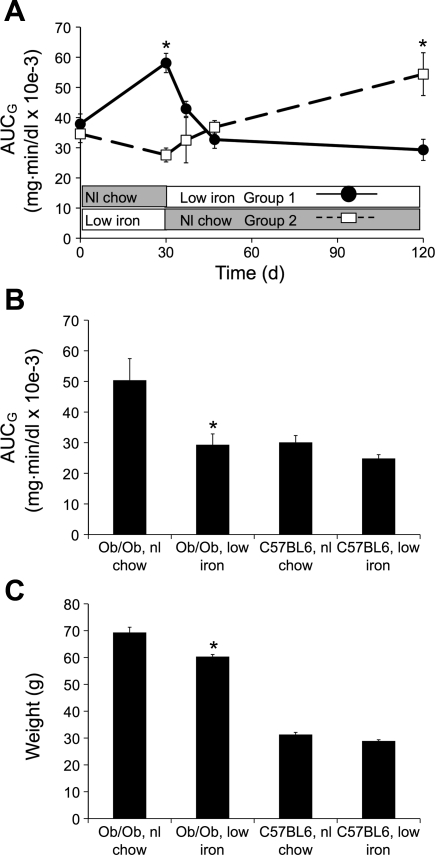

Ob/ob mice aged 4 wk had glucose tolerance testing performed, after which they were randomized to either the low-iron (35 mg/kg) or normal iron (500 mg/kg) chows. After retesting 4 wk later, the diets of the two groups were reversed, with repeat glucose tolerance testing performed 7, 17, and 90 days after the switch. Similar to the results in Fig. 1, AUCG during glucose tolerance testing differed significantly after 4 wk on low iron (35 mg/kg) compared with normal iron chow (500 mg/kg) (P < 0.001; Fig. 2A). When the mice were switched from 500 to 35 mg/kg iron chow (group 1; Fig. 2A, ●), their glucose tolerance status improved significantly within 7 days, and the protective effect persisted for ≤90 days. The mice on low iron that were switched to normal chow (group 2; Fig. 2A, □) had a somewhat slower worsening of their glucose tolerance status, becoming less glucose tolerant than group 1 17 days after the switch [P = not significant (NS)] and significantly worse at 120 days. At the termination of the study, the AUCG values for group 1 on low iron did not differ significantly from the AUCG value of group 2 measured at 30 days when that group had also been on low iron and vice versa. The AUCG values at the end of the study are shown in Fig. 2B, compared with wild-type mice on the two diets. Wild-type C57BL6 mice on low iron showed a modest (16%) but not statistically significant trend toward improved glucose tolerance. Consistent with the data in Fig. 1, ob/ob mice on low iron weighed slightly less that those on normal chow, but both groups of ob/ob mice weighed significantly more than the wild types (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Reversibility and duration of effects of low iron on glucose tolerance. Ob/ob mice aged 4 wk had glucose tolerance testing performed, after which they were randomized to either the low-iron or nl chow diets. After retesting 4 wk later, the diets of the 2 groups were reversed, with repeat glucose tolerance testing performed 7, 17, and 90 days after the switch. A: areas under the glucose curve (AUCG) for the 2 groups over time (n = 5–12/group, *P < 0.05 for the difference between the 2 groups at the indicated times). B: The AUCG values for the groups at the end of the study compared with wild-type mice of the same age on the 2 diets (*P < 0.01 for the low-iron group compared with the same strain on nl chow). C: weights of the mice at the end of the study (*P < 0.01 for the low-iron group compared with the same strain on nl chow).

Verification that the effects of the different diets are attributable only to iron content.

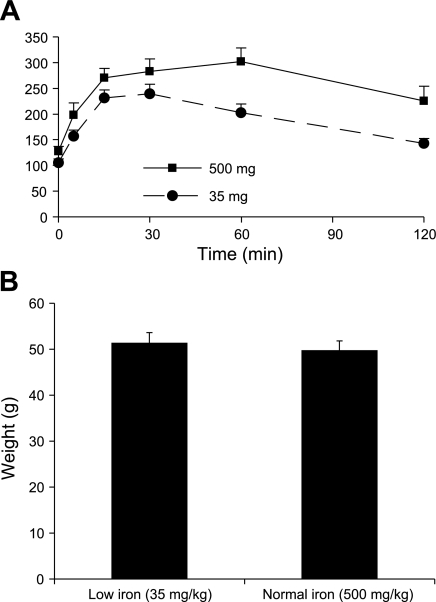

Because the above diets might have differed in other trace metals and in the relative amounts of carbohydrate derived from cornstarch vs. other sources, we sought to verify that the effects of the diets on insulin sensitivity could be isolated to iron. Therefore, we ground the low-iron diet (35 mg/kg iron) and added to it powdered carbonyl iron to match it to the normal chow iron content of 500 mg/kg. The mice on the higher-iron diet had significantly worse glucose tolerance after 3 (data not shown) and 6 wk on the diets (Fig. 3A). The AUCG was 31% higher in the high-iron group (P = 0.02). The weights of the mice did not differ on these two diets (Fig. 3B), but their weights were significantly lower than the mice on the normal pellet chow for an equivalent time (see Fig. 2), suggesting that the mice did not eat as much of the powdered food. Consistent with this, the AUCG for the low-iron group were as low as the mice on the 35 mg/kg iron pellet chow (Fig. 1), whereas the mice on the higher-iron powdered food had lower glucose excursions than the cohort on higher iron (normal) pellet chow (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

Mice on powdered diets containing 35 mg/kg iron exhibit better glucose tolerance than mice fed the same powdered diet supplemented with carbonyl iron to 500 mg/kg. Ob/ob mice (10/group) were placed on the powdered diet containing 35 mg/kg iron, with or without added carbonyl (elemental) iron, to total 500 mg/kg. Glucose tolerance testing was performed at 6 wk (A), at which time the mice were also weighed (B). Individual glucose values are significantly different at 30, 60, and 120 min.

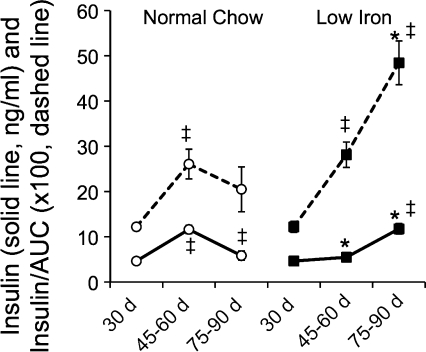

Insulin secretion does not fail in the face of obesity in mice on the low-iron diet. The data in Fig. 1 demonstrate a significant effect of the low-iron diet on both the insulin resistance and β-cell function indices HOMA-IR and -B. Our earlier data in a mouse model of hemochromatosis had also demonstrated that excess iron in β-cells resulted in oxidant stress and loss of insulin secretory capacity (23). Therefore, we investigated further the relationship between β-cell function and glucose tolerance over time. Ob/ob mice exhibited a significant increase in insulin levels 30 min after intraperitoneal glucose challenge between the ages of 30 and 45–60 days, consistent with their increasing weight and insulin resistance (Fig. 4, left solid line). However, as their diabetes status worsened between 60 and 90 days, insulin levels during the IPGTT declined. Also declining was the ratio of this insulin level to the AUCG (the insulin/AUC value is multiplied by 100 to facilitate visualization on the same graph; Fig. 4, left dotted line), an indication of their increasing inability to fully compensate for insulin resistance. In the ob/ob mice on low iron, in contrast, in the period between starting the low-iron diet on 30 and 45–60 days, insulin levels increased only slightly in the face of markedly improved glucose tolerance (see Figs. 1 and 3), resulting in a significant increase in the ratio of insulin during the IPGTT to the AUCG. These results are consistent with the decreased HOMA-IR and increased HOMA-B levels documented in Fig. 1. In the low-iron group, nearly normal glucose tolerance was maintained in the interval from 60 to 90 days (see Fig. 3), but at the expense of increased insulin secretion (Fig. 4, right solid line), as the animals aged and increased in weight. Thus the ratio of insulin to AUCG increased markedly (Fig. 4, right dotted line), demonstrating an improved capacity to maintain insulin secretion in the face of increased metabolic demand, obesity, and insulin resistance compared with the mice on normal chow.

Fig. 4.

Maintenance of insulin secretion in the face of obesity in the ob/ob mice on low-iron chow. From the intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test studies described in Fig. 3, the insulin level 30 min after glucose challenge and the AUCG values were calculated for mice on 500 mg/kg iron chow (○) and mice on reduced (35 mg/kg) iron chow (■). Insulin levels (solid lines) are presented as ng/ml. The AUCG values were g·min−1·dl over the 120-min study. The ratios of insulin to AUCG (dashed lines) were multiplied by 100 to allow visualization on the same graphing scale. Shown are means ± SE; n = 5–12/group. For the insulin values, error bars are within the data points and thus not visible. *P < 0.001 for low-iron group vs. normal chow; ‡P < 0.01 within groups for change from previous value.

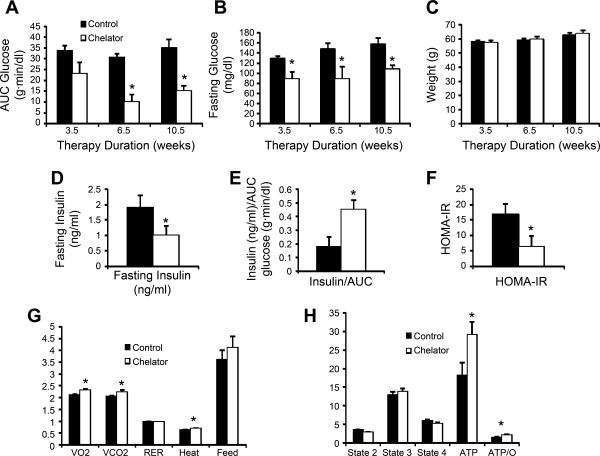

Iron chelation also protects from diabetes and preserves β-cell function in ob/ob mice. As an independent means of assessing the effects of iron on diabetes in ob/ob mice, we treated them with an oral iron chelator at a dose of 10 mg/day for ≤10.5 wk, with glucose tolerance testing performed at 3- to 4-wk intervals. AUCG trended downward after 3 wk of therapy and was decreased by 67% at 6.5 wk (P = 0.0001; Fig. 5A), with the effect being maintained at 10.5 wk (57% decrease, P < 0.001). Similar effects were seen with fasting glucose values, and in fact, the levels of fasting glucose in the treated mice were not in the diabetic range (all P < 0.05; Fig. 5B). Weights did not differ between the control and chelator-treated animals (Fig. 5C). Insulin levels were assessed at 6.5 wk and were significantly lower in the chelator-treated mice (P < 0.05; Fig. 5D). The low fasting glucose values precluded HOMA-B calculations, but as with the cohort restricted in dietary iron (Fig. 4), the chelator-treated group exhibited an improved ratio of insulin to the AUCG (P = 0.03; Fig. 5E). HOMA-IR values were also significantly lower in the treated group (Fig. 5F). No differences were noted in the red blood cell counts or red cell indices (not shown), and in fact the chelated group trended toward having higher hematocrits (50.4 ± 3.6 vs. 42.4 ± 2.5%, P = NS). In calorimetry cages, we documented that chelator-treated mice ate as much as the control mice and had higher rates of oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, and heat generation, with no change in the respiratory exchange ratio (Fig. 5G). Mitochondrial function was assessed in cardiac muscle, because the measurements in islets would require prohibitive numbers of mice. Oxygen consumption was similar between the two groups, although the chelator-treated mice had a significant increase in ATP production (60%, P < 0.05; Fig. 5H) and in the ratio of ATP production to oxygen consumption (49%, P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effects of iron chelation on glucose tolerance in ob/ob mice. At 30 days of age, mice on normal chow containing 500 mg/kg iron (5/group) were treated with 10 mg/kg of an iron chelator mixed in 100 mg of peanut butter delivered once a day. Control mice were treated with vehicle alone. Inspection verified consistently complete ingestion of the peanut butter in both groups. Glucose tolerance was assessed at 3.5, 6.5, and 10.5 wk after therapy was initiated. A: AUCG was calculated after intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing. B: fasting glucose values. C: weight of the mice over the treatment period. D–F: at the 6.5-wk test, insulin values were obtained at fasting (D) and at 30 min to allow calculation of the ratio of stimulated insulin to the AUCG (E); HOMA-IR values were also calculated (F). Low fasting glucose values in the treated mice precluded the obtaining of meaningful HOMA-B measurements. G: at the end of 10.5 wk of therapy, the mice were studied in a calorimeter. H: mice were treated for 1 wk with the chelator, at which time they were euthanized, and mitochondrial oxygen consumption was determined in permeabilized cardiac muscle fibers; n = 5 mice/group. *P < 0.05–0.001; see text for specific probability values.

Diminished protective effect of low iron in ob/ob mice on a high-fat diet.

Low iron also protected β-cell function in ob/ob mice on a high-fat diet (HOMA-B, P < 0.001; Table 2) to a degree similar to the mice on normal chow (Fig. 1). Because higher tissue iron levels also favor fatty acid oxidation and protect from high-fat-induced glucose intolerance (Huang J and McClain D, unpublished observations), we also predicted that the beneficial effects of low iron on insulin sensitivity and overall glucose disposal would not be seen to the same degree on high fat. Ob/ob mice on high fat exhibited a trend toward increased insulin resistance on the lower-iron (35 mg/kg) diet (P = NS), in contrast to the mice on the normal, high-carbohydrate chow containing 500 mg/kg iron (Fig. 1). Consistent with the counterbalancing effects of low iron on improving β-cell function but worsening insulin resistance, there was no significant difference in overall glucose tolerance between the groups, as shown by the AUCG. Weights also did not differ between the ob/ob mice on high fat/low iron compared with high fat/normal iron (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of dietary iron content on glucose tolerance in ob/ob or wild-type C57BL6 mice eating normal or high-fat chow

| Normal Chow, mg/kg iron |

High-Fat Chow, mg/kg iron |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 350 | 35 | 350 | 500 | |

| Ob/ob | |||||

| HOMA-B | 808 ± 71 | 567 ± 38* | |||

| HOMA-IR | 77.0 ± 4.9 | 68.0 ± 11.1 | |||

| AUCG, g•min−1•dl | 37.1 ± 2.8 | 40.0 ± 1.9 | |||

| Weight, g | 57.4 ± 1.2 | 58.7 ± 1.7 | |||

| C57BL6 | |||||

| HOMA-B | 76.0 ± 4.8 | 67.4 ± 3.6 | 133.5 ± 21.6† | 59.6 ± 1.9* | |

| HOMA-IR | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 19.9 ± 4.6† | 8.9 ± 1.5† | |

| AUCG, g•min−1•dl | 27.3 ± 1.4 | 34.2 ± 2.2* | 44.4 ± 4.8† | 42.5 ± 2.3† | |

| Weight, g | 28.9 ± 0.4 | 25.5 ± 1.6 | 40.6 ± 2.4† | 36.7 ± 1.2† | |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 38.4 ± 1.9 | 42.8 ± 1.8 | ND | ND | |

| Islet insulin, mg/islet | ND | ND | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 0.50 ± 0.06* | |

Results are means ± SE; n = 10 (ob/ob) or 5 (C57BL6) mice/group. HOMA-B, homeostasis model assessment of β-cell function; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; AUCG, area under the glucose curve. At 30 days of age, mice were placed on the indicated chows: normal chow (low fat) or high-fat chow containing the indicated concentrations of iron. After 45 days the mice were weighed, and glucose tolerance testing was performed.

P < 0.05 for 35 compared with 350 mg/kg chow within types of chow.

P < 0.05 for high-fat compared with normal chow of the same iron content.

Low iron improves glucose tolerance in wild-type C57BL6 mice on normal but not high-fat chow and protects β-cell function on high-fat chow. On the basis of the above results, we hypothesized that the effect of the lower-iron diet would be less evident in mice not stressed by excessive caloric intake and then only on normal (low-fat, high-carbohydrate) chow. Mice on normal chow with lower iron content (35 mg/kg) exhibited a modest 20% reduction in area under the glucose curve compared with normal chow with 350 mg/kg iron (P < 0.05; Table 2). This occurred despite a trend (13%, P = NS) toward increased weight. Neither HOMA-IR, HOMA-B, serum triglycerides, nor free fatty acids (not shown) differed in these two groups of mice. On a high-fat diet, the effect of iron on glucose tolerance was the opposite of that seen in mice on the high-carbohydrate chow. On high-fat and higher-iron chow, mice had a trend toward lower weight and improved glucose tolerance, consistent with data in other models of iron overload (Huang J and McClain D, unpublished observations). However, despite the improved glucose tolerance in the mice on higher-iron, high-fat chow, β-cell function is impaired significantly, with HOMA-B levels 55% lower than in mice on the lower-iron chow (P < 0.01) and with insulin content per islet decreased by 37% (P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

We have presented data demonstrating that decreasing iron levels through either dietary iron restriction or systemic iron chelation therapy dramatically improves the glycemia of the diabetes-prone, leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mouse. This is associated with improvements in both β-cell function and insulin sensitivity. The effects are stable over time and reversible, and they occur at levels of iron that are sufficient to maintain normal hematopoiesis. The effects are not explained by weight; for example, the ob/ob mice treated with an iron chelator exhibited normal glucose tolerance despite significant obesity that did not differ from untreated control ob/ob mice.

We have reported previously that iron impairs β-cell function at least partially by inducing oxidant stress and impairing mitochondrial function (7, 23). Maintenance of β-cell function is likely a factor in the current results, as evidenced by the fact that mice with lower iron regulate insulin levels more appropriately as a function of glycemia. We have made use of both homeostasis model (HOMA-B) calculations and ratios of stimulated insulin levels to glycemic excursions measured as the AUCG. Although neither of these values is completely validated as a measurement of β-cell function in mice, they provide an overall index of insulin responses to glucose levels, and they agree with assessments of islet insulin content (Table 2). Our results are consistent with the results in mouse models of hemochromatosis wherein β-cell function was analyzed by perifusion and immunohistochemistry, revealing both loss of β-cell mass and desensitization of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion with iron overload (23).

Mitochondrial dysfunction was prominent in the hemochromatosis model of iron overload, and consistent with those results, iron chelation significantly increased ATP production in mitochondria of the ob/ob mice on the higher-iron chow. The mechanism could not be attributed to an overall increase in oxygen consumption capacity but rather an improved coupling of oxygen consumption to ATP production. The precise mechanism underlying this mitochondrial effect of chelator therapy is under investigation.

The effects of iron as a prooxidant are not likely to be the entire explanation of its effects on insulin secretion. Iron is not simply a toxin but also plays a key role in physiological regulation of metabolism. In yeast, for example, iron is a key regulator of fuel choice and the AMPK-mediated response to glucose exhaustion (18). In multicellular organisms, iron and heme are involved in multiple processes, including signaling circadian rhythmicity (38), transcriptional regulation (30), translational regulation (17), and hypoxia responses (33), to name but a few. Likewise, “oxidant stress” itself plays a role beyond toxicity in physiological and adaptive signaling (27).

As further evidence of the role of iron in physiological regulation of metabolism, groups including ours have shown that iron affects metabolism in a wide-reaching fashion well beyond the scope of preserving insulin secretory capacity. We have shown that iron affects insulin sensitivity through complex mechanisms involving AMPK-mediated skeletal muscle glucose uptake, hepatic glucose cycling, and adipokine production (Ref. 19 and Huang J and McClain D, unpublished observations). Specifically, iron promotes fatty acid oxidation such that high-iron mice are hypermetabolic on high-fat but not normal chow, resulting in relative protection from obesity and obesity-induced insulin resistance. That such effects of iron are operative in the results reported herein is demonstrated by the fact that iron restriction is less effective in protecting mice on high-fat diets (Table 2). This is likely related to AMPK- and adiponectin-dependent effects of iron in promoting fatty acid oxidation at the expense of glucose oxidation (Huang J and McClain D, unpublished observations) and possibly other interactions of fat and iron metabolism (32). The effect of iron on altering triglyceride and fatty acid metabolism likely plays a role in the insulin-sensitizing effects of low iron, but it is likely not the sole mechanism because of the lack of significant effects of iron on these parameters in wild-type C57 mice. In summary, iron exerts pleiotropic effects across several tissues. In all models, low iron protects β-cell function, but iron's promotion of fatty acid oxidation translates to effects on obesity and metabolism that vary with diet. These effects are seen in both wild-type and ob/ob mice (Table 2), suggesting that the effects are not specific to that genetic model and not leptin dependent.

These results have significant clinical implications for human type 2 diabetes. As reviewed briefly in the introduction, increased iron stores are a significant risk factor for type 2 diabetes (2, 10, 14, 15, 22, 26, 34, 35, 37) and other aspects of the metabolic syndrome (16, 20, 21, 31). The clinical manipulation of iron stores, including by pharmacological means, may influence the natural history of diabetes and provide additional tools for the clinical management of the disease. Importantly, the chelator-treated mice described in this report maintained normal hematopoiesis and serum ferritin levels similar to untreated controls. These data suggest that similar effects might be observed in patients with high “normal” iron stores as reflected by serum ferritin. Phlebotomy of research subjects with high-normal serum ferritin in the early stages of diabetes to reduce total body iron stores is underway to test this hypothesis.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [DK-58512 (D. A. McClain) and HL-73167 (E. D. Abel)], the Research Service of the Veterans Administration (D. A. McClain), and the University of Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Research (UL1-RR025764; D. A. McClain).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham D, Rogers J, Gault P, Kushner JP, McClain DA. Increased insulin secretory capacity but decreased insulin sensitivity after correction of iron overload by phlebotomy in hereditary haemochromatosis. Diabetologia 49: 2546–2551, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afkhami-Ardekani M, Rashidi M. Iron status in women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications 23: 194–198, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergeron RJ, Wiegand J, McManis JS, Bharti N, Singh S. Design, synthesis, and testing of non-nephrotoxic desazadesferrithiocin polyether analogues. J Med Chem 51: 3913–3923, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bofill C, Joven J, Bages J, Vilella E, Sans T, Cavalle P, Miralles R, Llobet J, Camps J. Response to repeated phlebotomies in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 43: 614–620, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borel MJ, Beard JL, Farrell PA. Hepatic glucose production and insulin sensitivity and responsiveness in iron-deficient anemic rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 264: E380–E390, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudina S, Laclau MN, Tariosse L, Daret D, Gouverneur G, Bonoron-Adele S, Saks VA, Dos Santos P. Alteration of mitochondrial function in a model of chronic ischemia in vivo in rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H821–H831, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooksey RC, Jouihan HA, Ajioka RS, Hazel MW, Jones DL, Kushner JP, McClain DA. Oxidative stress, beta-cell apoptosis, and decreased insulin secretory capacity in mouse models of hemochromatosis. Endocrinology 145: 5305–5312, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Facchini FS. Effect of phlebotomy on plasma glucose and insulin concentrations. Diabetes Care 21: 2190, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facchini FS, Hua NW, Stoohs RA. Effect of iron depletion in carbohydrate-intolerant patients with clinical evidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 122: 931–939, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez-Real JM, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ricart W. Cross-talk between iron metabolism and diabetes. Diabetes 51: 2348–2354, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez-Real JM, Penarroja G, Castro A, Garcia-Bragado F, Hernandez-Aguado I, Ricart W. Blood letting in high-ferritin type 2 diabetes: effects on insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function. Diabetes 51: 1000–1004, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Real JM, Penarroja G, Castro A, Garcia-Bragado F, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ricart W. Blood letting in high-ferritin type 2 diabetes: effects on vascular reactivity. Diabetes Care 25: 2249–2255, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming DJ, Jacques PF, Tucker KL, Massaro JM, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Wilson PW, Wood RJ. Iron status of the free-living, elderly Framingham Heart Study cohort: an iron-replete population with a high prevalence of elevated iron stores. Am J Clin Nutr 73: 638–646, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford ES, Cogswell ME. Diabetes and serum ferritin concentration among US adults. Diabetes Care 22: 1978–1983, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forouhi NG, Harding AH, Allison M, Sandhu MS, Welch A, Luben R, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Wareham NJ. Elevated serum ferritin levels predict new-onset type 2 diabetes: results from the EPIC-Norfolk prospective study. Diabetologia 50: 949–956, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillum RF. Association of serum ferritin and indices of body fat distribution and obesity in Mexican American men—the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25: 639–645, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harford JB, Klausner RD. Coordinate post-transcriptional regulation of ferritin and transferrin receptor expression: the role of regulated RNA-protein interaction. Enzyme 44: 28–41, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haurie V, Boucherie H, Sagliocco F. The Snf1 protein kinase controls the induction of genes of the iron uptake pathway at the diauxic shift in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 278: 45391–45396, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J, Gabrielsen JS, Cooksey RC, Luo B, Boros LG, Jones DL, Jouihan HA, Soesanto Y, Knecht L, Hazel MW, Kushner JP, McClain DA. Increased glucose disposal and AMP-dependent kinase signaling in a mouse model of hemochromatosis. J Biol Chem 282: 37501–37507, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwasaki T, Nakajima A, Yoneda M, Yamada Y, Mukasa K, Fujita K, Fujisawa N, Wada K, Terauchi Y. Serum ferritin is associated with visceral fat area and subcutaneous fat area. Diabetes Care 28: 2486–2491, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jehn M, Clark JM, Guallar E. Serum ferritin and risk of the metabolic syndrome in U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 27: 2422–2428, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang R, Manson JE, Meigs JB, Ma J, Rifai N, Hu FB. Body iron stores in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in apparently healthy women. JAMA 291: 711–717, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jouihan HA, Cobine PA, Cooksey RC, Hoagland EA, Boudina S, Abel ED, Winge DR, McClain DA. Iron-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial manganese uptake mediates mitochondrial dysfunction in a mouse model of hemochromatosis. Mol Med 14: 98–108, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knutson MD, Oukka M, Koss LM, Aydemir F, Wessling-Resnick M. Iron release from macrophages after erythrophagocytosis is up-regulated by ferroportin 1 overexpression and down-regulated by hepcidin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 1324–1328, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kriska AM, Saremi A, Hanson RL, Bennett PH, Kobes S, Williams DE, Knowler WC. Physical activity, obesity, and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in a high-risk population. Am J Epidemiol 158: 669–675, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangiagli A, Italia S, Campisi S. Glucose tolerance and beta-cell secretion in patients with thalassaemia major. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 11: 985–986, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin P, Feng Y. Inflammation: Wound healing in zebrafish. Nature 459: 921–923, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28: 412–419, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClain DA, Abraham D, Rogers J, Brady R, Gault P, Ajioka R, Kushner JP. High prevalence of abnormal glucose homeostasis secondary to decreased insulin secretion in individuals with hereditary haemochromatosis. Diabetologia 49: 1661–1669, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mense SM, Zhang L. Heme: a versatile signaling molecule controlling the activities of diverse regulators ranging from transcription factors to MAP kinases. Cell Res 16: 681–692, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qi L, van Dam RM, Rexrode K, Hu FB. Heme iron from diet as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 30: 101–106, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rumberger JM, Peters T, Jr, Burrington C, Green A. Transferrin and iron contribute to the lipolytic effect of serum in isolated adipocytes. Diabetes 53: 2535–2541, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semenza GL. Involvement of oxygen-sensing pathways in physiologic and pathologic erythropoiesis. Blood 114: 2015–2019, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharifi F, Nasab NM, Zadeh HJ. Elevated serum ferritin concentrations in prediabetic subjects. Diab Vasc Dis Res 5: 15–18, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuomainen TP, Nyyssönen K, Salonen R, Tervahauta A, Korpela H, Lakka T, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT. Body iron stores are associated with serum insulin and blood glucose concentrations. Population study in 1,013 eastern Finnish men. Diabetes Care 20: 426–428, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viatte L, Nicolas G, Lou DQ, Bennoun M, Lesbordes-Brion JC, Canonne-Hergaux F, Schönig K, Bujard H, Kahn A, Andrews NC, Vaulont S. Chronic hepcidin induction causes hyposideremia and alters the pattern of cellular iron accumulation in hemochromatotic mice. Blood 107: 2952–2958, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson JG, Lindquist JH, Grambow SC, Crook ED, Maher JF. Potential role of increased iron stores in diabetes. Am J Med Sci 325: 332–339, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin L, Wu N, Curtin JC, Qatanani M, Szwergold NR, Reid RA, Waitt GM, Parks DJ, Pearce KH, Wisely GB, Lazar MA. Rev-erbalpha, a heme sensor that coordinates metabolic and circadian pathways. Science 318: 1786–1789, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]