Abstract

Since 2006, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society heart failure (HF) guidelines have published annual focused updates for cardiovascular care providers. The 2010 Canadian Cardiovascular Society HF guidelines update focuses on an increasing issue in the western world – HF in ethnic minorities – and in an uncommon but important setting – the pregnant patient. Additionally, due to increasing attention recently given to the assessment of how care is delivered and measured, two critically important topics – disease management programs in HF and quality assurance – have been included. Both of these topics were written from a clinical perspective. It is hoped that the present update will become a useful tool for health care providers and planners in the ongoing evolution of care for HF patients in Canada.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Disease management, Ethnicity, HF, Heart failure clinic, Minority, Outcomes, Performance indicator, Peripartum, Pregnancy, Quality assurance, Quality of care

Abstract

Depuis 2006, la Société canadienne de cardiologie publie chaque année une mise à jour de ses Lignes directrices sur l’insuffisance cardiaque (IC) ciblées, à l’intention des professionnels de la santé cardiovasculaire. La mise à jour 2010 des Lignes directrices de la Société canadienne de cardiologie sur l’IC porte sur un problème croissant en Occident, l’insuffisance cardiaque chez les minorités ethniques, et sur un tableau rare mais important, l’insuffisance cardiaque chez la femme enceinte. En outre, comme on accorde depuis peu une plus grande attention à l’évaluation de la façon dont les soins sont prodigués et évalués, deux autres sujets d’une grande importance sont abordés : les programmes de prise en charge de l’IC et l’assurance de la qualité. Ces deux derniers volets ont été rédigés d’un point de vue clinique. Il est à espérer que la présente mise à jour deviendra un outil pratique pour les professionnels de la santé et les planificateurs, compte tenu de l’évolution constante des soins prodigués aux patients atteints d’IC au Canada.

Since 2006, the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) has been publishing heart failure (HF) guidelines as part of a commitment to a multiyear, closed-loop initiative to provide support for the best practice of HF management. The systematic review strategy and methods for formulating the recommendations are described in more detail on the CCS HF Consensus Program Web site in the Terms of Reference section (www.hfcc.ca, navigate to www.hfcc.ca/downloads/stage3/Terms_of_Reference_CDT.pdf).

Individuals from all relevant professional groups are represented and include the Canadian Pharmacists Association, the Canadian Council of Cardiovascular Nurses, the Canadian Geriatrics Society, the Canadian Society of Internal Medicine, the College of Family Physicians of Canada, and the Canadian Association of Advanced Practice Nurses. In response to needs assessments of cardiovascular care providers, the objective of the 2010 CCS HF consensus update is to provide Canadian practitioners with recommendations and advice in four emerging areas – HF in ethnic minority populations, HF and pregnancy, disease management of HF clinic care, and HF quality improvement and assurance. Each of these topics is approached from a clinical perspective with recommendations and practical tips designed for relevancy to the practicing clinician.

An extensive dissemination and implementation program has been developed for the CCS HF Consensus Program. In addition to the CCS National HF Workshop Initiative, bilingual versions of a handy ‘pocket card’ and slide kit have been developed based on the recommendations from 2006 to 2009 and are available online. Details regarding these and other initiatives can be found on the CCS HF Consensus Program Web site (http://hfcc.ca/index.aspx).

The class of recommendation and the grade of evidence were determined according to Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Classes of recommendations and levels of evidence

| Class | Definition |

| I | Evidence or general agreement that a given procedure or treatment is beneficial, useful and effective |

| II | Conflicting evidence or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness or efficacy of the procedure or treatment |

| IIa | Weight of evidence is in favour of usefulness or efficacy |

| IIb | Usefulness or efficacy is less well established by evidence or opinion |

| III | Evidence or general agreement that the procedure or treatment is not useful or effective and in some cases may be harmful |

| Level | Definition |

| A | Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses |

| B | Data derived from a single randomized clinical trial or nonrandomized studies |

| C | Consensus of opinion of experts and/or small studies |

HF IN ETHNIC MINORITY POPULATIONS IN CANADA

Recommendations

Health care providers should consider the prevalent etiological factors for HF, language, ethnoculture and social values, and diagnostic patterns as well as the potential barriers to health care that are specific to their patients with HF from an ethnic minority group. (Class I, level C)

- In the management of black subjects with HF, the following are recommended:

- ○ Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors as standard therapy in patients with HF and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of less than 40%. (Class I, level A)

- ○ Beta-blockers as standard therapy in patients with HF and an LVEF of less than 40%. (Class I, level B)

- ○ A combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate as part of standard therapy in addition to beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors in patients with moderate to severe HF and an LVEF of less than 35%. (Class I, level B)

Practical tips

- Family and social values within the ethnocultural background underlie a patient’s attitudes and beliefs toward health and disease. When managing patients from ethnic minority groups with HF, health care professionals, where possible, should do the following:

- ○ Ensure proper language translation is available and include family members in the overall management plan.

- ○ Provide medical information or educational aids in a language understood by patients or their caregivers.

- ○ Respect local traditions and be careful not to impose professionals’ own values.

- ○ Work as multidisciplinary teams.

- ○ Include community health representatives, where appropriate.

Health care workers and patients should be aware of the risk factors for the development of HF such as hypertension and obesity, which are more prevalent in certain ethnic groups, and should work to prevent and treat these conditions.

- During assessment, etiologies that are prevalent in a patient’s home region must be considered in addition to common causes of HF in Canada.

- ○ Chagas disease and rheumatic heart disease, besides coronary artery disease, should be considered in those who recently arrived from South America.

- ○ Rheumatic heart disease should still be considered in a patient who recently immigrated from Africa.

Diastolic HF or HF with preserved systolic function is especially common in patients of Chinese, black and Aboriginal descent.

Treatment of a patient with HF from an ethnic minority group should follow the same treatment recommendations from current practice guidelines. However, consideration should be given to lower starting dosages for pharmacotherapy in certain ethnic groups (ie, Chinese and Japanese patients frequently are administered a lower starting dose of ACE inhibitors or beta-blockers). Target dosage remains identical to guideline recommendations.

Recommendations and practical tips that pertain to specific ethnic minority groups are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Basic overview of the four most common ethnic minority populations in Canada

| Population, % of minorities in Canada | Important risk factors for HF prevention | Language and ethnocultural considerations | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Asian, 25% | Diabetes, obesity and the metabolic syndrome | Mostly speak English Family involvement in health care behaviour is common |

Evidence-based therapy from HF guidelines |

| Chinese, 24% | Hypertension* | Mostly speak Cantonese and Mandarin Family involvement in health care behaviour is common |

Follow HF guidelines Be aware of the use of traditional Chinese medicines |

| Black, 15.8% | Hypertension | Almost all speak English, apart from Quebec, where French is prominent | Follow HF guidelines Consider adding nitrate/hydralazine combination in those with severe HF |

| Aboriginal, 24% | Diabetes, obesity | Cree and Ojibwe are the main spoken languages Frequently need to involve family and community representatives in health care initiatives |

Follow general HF guidelines |

Coronary artery disease, diabetes and obesity are rapidly emerging risk factors. HF Heart failure

General considerations

Few places in the world possess the racial diversity that is present in Canada. Based on the Statistics Canada 2006 Census (1), the visible minority population surpassed five million, reaching 16.2% of the population. Of these, the four most common minorities in Canada include Chinese, South Asian, black and Aboriginal groups. Together, these four groups comprise over 88% of visible minorities in Canada and, as such, the focus of the present section will primarily be on them. In addition, most of the data currently published in this arena has been observational in nature. However, apart from ethnocultural data, most of the published data suggest that there are more similarities than differences among these populations and Caucasians with respect to diagnosis or treatment of HF. To understand and manage a person’s illness, it is necessary to appreciate the effects of the person’s culture, experiences and social environment. Hope and morale may be crucial to patients’ adaptation and maintenance of involvement in the management of their condition (2), and gaps in communications as a result of ethno-cultural differences between the patients and the health care workers may have a detrimental effect on patients’ adaptation to their illness.

To date, there have been very few published population-based epidemiological studies of HF in countries outside North America and western Europe. It is generally believed that rheumatic heart disease is a major cause of HF in sub-Saharan Africa, and certain parts of Asia and South America. Hypertension is an important cause of HF in Asia and in the African and African American populations, whereas Chagas disease is a cause of HF in subjects from South America (3). However, because these regions constantly undergo epidemiological and economic transitions, the epidemiology of HF is likely to increasingly resemble that of the western world. The large international case-controlled INTERHEART study (4) has demonstrated that the impact of conventional and potentially preventable risk factors on the risk of myocardial infarctions is consistent across different geographical regions and different ethnic groups. This implies that similar preventive measures for myocardial infarction and the subsequent development of HF may be applicable to different ethnic populations in different geographical locations. There is little evidence to indicate that the criteria used to diagnose HF substantially differs among ethnic populations. For example, a recent study from the United States (US) (5) demonstrated that the diagnostic performance of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide is similar in African Americans and non-African Americans. With respect to the treatment of patients with HF, relatively few large-scale randomized controlled intervention trials in HF have included regions outside Europe and the US. Smaller clinical trials (6,7) have shown the effectiveness of ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers in HF patients from Africa and Asia. Given the fundamental nature of the derangements in HF, our current approach, including neurohormonal blockade and the appropriate use of devices, will likely be effective, although dosages and responses may differ slightly among ethnic groups.

The South Asian population

The South Asian population, representing those from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and surrounding countries, is currently the largest and fastest growing visible minority group, comprising 25% of all visible minorities (4% of Canadians) (1). South Asian Canadians have varying backgrounds, which limits generalities that can be made about their social and community life. The majority of South Asians who seek medical care speak or are accompanied by family members who speak English. It is common for South Asian patient populations to involve or depend on extended families and/or community figures or relations in their medical decision making.

South Asians have increased susceptibility to premature morbidity and mortality from coronary artery disease (8–11). Hypertension (as well as diabetes and dyslipidemia) is a major problem in Asia Pacific regions, including China, and high blood pressure is poorly controlled (12,13). In a study conducted in Leicestershire, United Kingdom (14), involving 5789 consecutive patients admitted with HF, admission rates for HF were higher among South Asian patients than white patients. At the first admission, South Asian patients were younger and more frequently had concomitant diabetes or acute coronary syndrome than white patients, although clinical outcomes were similar. In a matched historical cohort study – also conducted in Leicestershire – of patients newly hospitalized for HF (15), the South Asian patients had rates of previous coronary artery disease that were similar to Caucasian patients, but more often had previous hypertension and diabetes. At follow-up, South Asian patients had a lower mortality rate than Caucasian patients. A retrospective sequential chart review of South Asians and non-South Asian white individuals hospitalized with a primary diagnosis of HF at two Toronto (Ontario)-area community hospitals demonstrated that South Asians were younger, of lower body mass index and were more often diabetic, although they did not suffer increased mortality (16). These data suggest that South Asians suffer a higher risk factor burden for the development of coronary artery disease and subsequent HF, although their outcomes may not be different. Thus, to prevent HF in the South Asian population, health care professionals as well as the South Asian community should be made aware of their unique risk profile so that appropriate ethnocultural-specific screening procedures and support programs can be implemented.

The Chinese population

The Chinese population represents the second largest visible minority group, comprising 24% of the minority population in Canada (1). Chinese is the third most commonly spoken language in Canada and many Chinese people do not understand English well. Modern Chinese people continue to emphasize family values and maintain close family links, which play a prominent role in health behaviours and medical decision making. Evidence from a large survey (17) of a cohort of Chinese people in two large Canadian cities indicated a lack of awareness of symptoms of stroke and myocardial infarction and risk factors for heart disease. This lack of knowledge, combined with social and ethnocultural factors, may confound the management of Chinese patients with HF or at risk of developing HF. One strategy that helps to break the language barrier is to provide health information designed specifically for Chinese patients, exemplified by the Chinese language brochure entitled “Living with HF”, produced recently by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (www.heartandstroke.on.ca/site/c.pvI3IeNWJwE/b.3581609/k.90B3/Multicultural_Resources.htm).

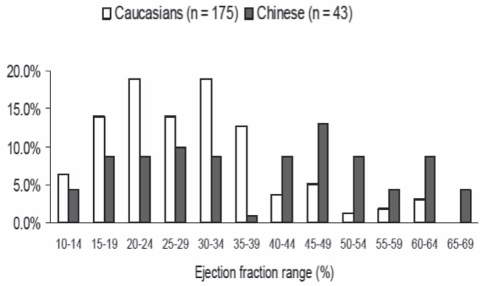

Available data, which are not definitive, point to hypertension being the most important identifiable risk factor in Chinese people with HF (18,19). In a prospective study (20) of 730 consecutive Hong Kong Chinese patients admitted to the hospital with HF, the main identifiable risk factors were hypertension (37%), coronary artery disease (31%), diabetes (21%), valvular heart disease (15%), cor pulmonale (27%), idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (4%) and miscellaneous (10%). In women, hypertension was the most common cause of HF at all ages but in men younger than 70 years of age, coronary artery disease was equal in frequency to hypertension (36% and 35%, respectively) (20). A subsequent study reported by the same group (21) evaluated 200 consecutive patients with the typical features of HF using two-dimensional Doppler echocardiography. The results showed 66% of patients had an LVEF of greater than 45% (which was more common in those older than 70 years of age) and an additional 12.5% had significant valvular heart disease. These investigators concluded that HF with a normal LVEF is more common than systolic HF in Chinese patients and that this may be related to an older age at presentation and the high prevalence of hypertension. These results are supported by those of a case-mix study (22) from an urban tertiary care centre in Toronto, where Chinese patients with HF were older and were more likely to have an ejection fraction of greater than 40% (and a higher median ejection fraction) than their Caucasian counterparts (Figure 1). The metabolic syndrome has been identified in an increasingly large proportion of Chinese adults; obesity has become an important public health concern in China (23). Investigations conducted by the Shanghai Investigation Group of HF in 1980, 1990 and 2000 (24), based on 2178 hospitalized patients with HF, found that the etiology of HF had shifted from mainly rheumatic valvular disease to coronary artery disease during the previous 20 years (24). It is anticipated that antecedent factors for incident HF in the Chinese population will increasingly mirror those of the western world.

Figure 1).

Distribution of left ventricular ejection fraction values in Caucasian and Chinese patients with heart failure. Data from reference 22

There are no large-scale randomized controlled trials of pharmacological and device therapy conducted specifically among Chinese patients with HF. The recently published Hong Kong diastolic HF study (25) investigated 150 Chinese patients with HF and preserved systolic function, and reported no significant additional benefit by adding irbesartan or ramipril to diuretic treatment. It has been stated that Chinese subjects experience a high incidence of cough when treated with ACE inhibitors (26,27). However, most of the studies that reported a high incidence of ACE inhibitor-induced cough in Chinese patients involved a very small number of patients and did not compare Chinese patients with Caucasian patients simultaneously. In the Perindopril Protection Against Recurrent Stroke Study (PROGRESS) (28,29), there were no differences in cough among the Asian and non-Asian participants. Given the compelling data in support of the benefit of ACE inhibition in HF with systolic dysfunction, a Chinese patient with HF should not be denied the initiation of an ACE inhibitor based on anticipated intolerance. The doses of antihypertensive agents prescribed in Asian patients are frequently lower than in Caucasian patients, due in part to a perception of greater sensitivity (30) and, therefore, a higher risk of hypotension in Asian patients. Although this is by no means a uniform finding, it is a common practice to start vasodilator medications at lower doses and to titrate the dose slower than in a Caucasian patient, but with a goal of eventually reaching the same target dose. As such, current recommendations from the Chinese guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic HF closely resemble those contained in guidelines in the western world (31).

It is quite common for Chinese patients to consume traditional Chinese medicines in which herbal medicines form the key component in combination with their prescribed western medicines. In Canada, the use of these combinations is largely incidental rather than intentional; this means that patients typically do not advise their clinicians of concomitant use, which may expose the patients to potentially undesirable drug-drug or herb-drug interactions. Examples of many such interactions that may be relevant when managing a patient with HF include a change in the effect of warfarin with the use of dong quai, or an attenuation of the effect of diuretics and vasodilators with the use of fu ling and ma huang (32).

The black population

Black Canadians constitute 2.5% of the Canadian population (1). While many black individuals in Quebec are of Haitian (as well as Central African) descent and speak French, the majority of black individuals living elsewhere in Canada speak English. Most of the population and randomized controlled data have been derived from the US. In the US, African Americans have a higher prevalence of HF than persons of other ethnicities. They also present with symptoms of HF at younger ages, which are less likely to be due to coronary artery disease than in Caucasians (33–35). Recently published data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study (36) indicated that one in 100 African American men and women develop HF at an average age of 39 years, which is 20 times the rate in Caucasians. Incident HF in African Americans before 50 years of age was associated with antecedent hypertension, obesity, chronic kidney disease and systolic dysfunction that were already present before 35 years of age (36). These data imply that relatively young black subjects with risk factors should be a target of more aggressive intervention for HF prevention. Data from the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) trials (37–39) suggest poorer outcomes for black HF patients, while other reports suggest that clinical characteristics independent of HF may contribute to these outcomes.

Longstanding clinical observations suggest that black individuals with hypertension respond less well than Caucasians to ACE inhibitors (40). Retrospective subgroup analyses of data from randomized trials (41) suggest the response of black individuals and Caucasians with HF and left ventricular systolic dysfunction to ACE inhibition may differ. However, these post hoc analyses do not provide sufficient evidence to support a strategy other than routine use of ACE inhibitors in black individuals with HF and systolic dysfunction. Although the Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial (BEST) (42) with bucindolol did not find a beneficial effect of beta blockade in black individuals with HF, a subgroup analysis of data from the US Carvedilol Trials (43–45), as well as other trials, suggests that the beneficial effect of beta-blockers on outcomes in black individuals with HF with systolic dysfunction is similar to the effects in the overall population. The total data to date therefore support the use of ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers in black patients with HF and systolic dysfunction.

Data from the earlier Vasodilator-HF Trial (VHeFT) I and II (46) suggested black patients with HF and an LVEF of less than 35% were particularly responsive to hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate. The African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT) (47) enrolled 1050 black patients who had New York Heart Association class III or IV symptoms of HF with dilated ventricles and systolic dysfunction. In this randomized trial, subjects were assigned to receive a fixed combination of isosorbide dinitrate plus hydralazine or placebo in addition to standard therapy for HF. The primary end point was a composite score made up of weighted values for death from any cause, a first hospitalization for HF, and change in the quality of life. The study was terminated early because of a significantly higher mortality rate in the placebo group than in the group given the fixed combination of isosorbide dinitrate plus hydralazine. The mean primary composite score was significantly better in the group given isosorbide dinitrate plus hydralazine than in the placebo group, as well as its components: 43% reduction in the rate of death from any cause, 33% relative reduction in first hospitalization for HF, and an improvement in the quality of life. These data support the addition of the combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine to the standard medical regimen for black patients with moderately severe HF due to low ejection fraction.

The Aboriginal population

Data from the 2006 Census on Canada’s Aboriginal population counted 1,172,790 First Nations, Métis and Inuit people (the three political groupings), representing 3.8% of Canada’s total population. More than one-half of the country’s 1.2 million Aboriginal people are living off reserve. The First Nations population has a growth rate that is three times the Canadian rate (see the “Assembly of First Nations Royal Commission on Aboriginal People at 10 years: A Report Card 2006”, available at www.afn.ca). Aboriginal people were almost four times as likely as non-Aboriginal people to live in a crowded dwelling and were three times as likely to live in a dwelling in need of major repairs. The life expectancy is 7.4 years less and 5.2 years less for First Nations men and women compared with Canadian men and women, respectively. Furthermore, there is also evidence to indicate that geographical location, compared with Aboriginal identity, appears to have a large impact on health status and the use of physician services, with on-reserve Aboriginals reporting a lower likelihood of having seen a physician and ranking their health as poor (48).

The Study of Health Assessment and Risk Evaluation in Aboriginal Peoples (SHARE-AP) (49) reported a higher frequency of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among Aboriginal people and a greater burden of atherosclerosis compared with Canadians of European ancestry. These were accompanied by social, economic and cultural changes in the past decades, which might have had an impact on the observed increase in hospitalization for coronary artery disease (50). With the increasing incidence of diabetes that accompanies the transition from traditional to urban lifestyles (51,52), it is anticipated that the incidence of CVD and HF will also increase.

There are no Canadian data available that can directly guide the management of HF in the Aboriginal population. In patients who commenced dialysis in Alberta, Saskatchewan or Manitoba, the risk of death from HF was higher in Aboriginals than in Caucasians (hazard ratio [HR] 1.66, 95% CI 1.51 to 1.83) (53). A report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (54) has indicated that HF is a major cause of illness and death among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The prevalence of HF in Australian Aboriginals was nearly twice as high as in non-Aboriginal Australians.

When managing Aboriginal patients with HF, non-Aboriginal health care professionals should understand the logic and rationale of another system of thought in which health is perceived as a harmonious order. There is a need to understand that health encompasses physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual well-being; to recognize the multigenerational legacies of colonization and importance of local history; to respect traditional beliefs and healing practices; and to acknowledge the role of the social determinants of health and, in many communities, inadequate resources. Health care professionals may need to additionally adapt their treatment plans and education programs for communities that are geographically remote. Non-Aboriginal health care workers caring for Aboriginal patients with HF may adopt a holistic approach in offering advice and care for their patients, respecting local traditions and by being careful not to impose their own values (55). Health care workers should work in multidisciplinary teams and include community health representatives. Aboriginal patients might be operating in a second language, might need an interpreter, and might not be comfortable questioning someone who is perceived to have greater power and knowledge. A chronic disease management program (DMP), such as the Chronic Disease Outreach Program (56), designed to improve awareness and management of hypertension, renal disease and diabetes in remote Australian Aboriginal communities may be adopted for the prevention and treatment of HF in Canadian Aboriginals.

In summary, an appreciation of the ethnocultural diversity of Canada is essential to successful prevention and treatment of HF among the multiethnic groups. Strong ongoing efforts to increase the awareness of risk factors for the development of HF and inclusion of ethnic populations in randomized controlled trials are required to improve the outcome of HF in patients from ethnic minority groups (22).

HF AND PREGNANCY

Definition

Evidence of inadequate cardiac output despite elevated or normal cardiac filling pressure secondary to cardiac dysfunction occurring during pregnancy, labour and delivery, or in the early postpartum period.

Recommendations

Health care professionals should be aware of the cardiovascular changes associated with normal pregnancy because those changes may unmask pre-existing heart conditions or precipitate decompensation in established or new-onset HF. (Class I, level C)

Cardiac testing of women with worsening or suspected new-onset HF during pregnancy should include echocardiography; radiation should be avoided where possible. (Class I, level C)

Women with a history of HF should have a complete preconception evaluation and counselling by an individual with expertise and experience in HF and pregnancy before becoming pregnant or as early as possible once pregnancy is known. Risk of transmission of inheritable cardiac disease should be addressed where appropriate. (Class I, level C)

Women with mechanical heart valves, Eisenmenger’s syndrome, Marfan syndrome with aortopathy, and cardiomyopathy/peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) with reduced LVEF should be referred to a regional centre with expertise in management of HF in pregnancy for evaluation, ongoing care and discussion of the health consequences of continuing the pregnancy. (Class I, level C)

A risk score used to identify predictors associated with the development of unfavourable cardiac events in women with heart disease (Table 3) may be used to allow for establishment of a plan of management for the antepartum, peripartum and postpartum periods. (Class I, level C)

Where possible, cardiac medications of a certain class (such as beta-blockers) should be switched to a member of that class where safety in pregnancy has been accepted. (Class IIa, level C)

Women with HF during pregnancy should be closely followed during their pregnancy and monitored at the time of delivery and the early postpartum period. (Class I, level C)

Anticoagulation during pregnancy should be undertaken according to the American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) 2008 (84). (Class I, level C)

In most instances, the decision regarding timing and mode of delivery is based on obstetrical factors. Caesarean deliveries are not routinely necessary. Delivery before term for cardiac decompensation is rarely required. (Class IIa, level C)

Patients with PPCM who do not recover normal left ventricular function should be advised against future pregnancies due to the high risk of worsening HF and death. (Class I, level B)

Patients with PPCM who recover normal left ventricular function should be advised regarding the potential for recurrent left ventricular dysfunction in subsequent pregnancies. (Class I, level B)

Pregnant women (or those in the peripartum period) with acute decompensated HF should be managed according to the CCS guidelines for acute decompensated HF and should be referred to a tertiary centre with expertise in advanced HF management, including mechanical circulatory support and cardiac transplantation. (Class I, level C)

Several commonly used cardiac medications, such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), aldosterone antagonists and warfarin, are teratogenic. Their use should be avoided or, in the case of warfarin, restricted to certain portions of the pregnancy. (Class I, level C)

TABLE 3.

Predictors and the rate of maternal cardiac complications

| Number of maternal conditions | Estimated/expected risk (primarily hospitalization), % | Observed event rate, % |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 3 |

| 1 | 27 | 30 |

| >1 | 75 | 66 |

Practical tips

The possibility of HF and/or PPCM should be considered in patients with new-onset dyspnea or hemodynamic decompensation late in pregnancy, during labour and delivery, or in the postpartum period.

Dyspnea of normal pregnancy is often described as an inability to get enough air in, to get a deep breath, or both. Mild dyspnea on exertion alone does not suggest HF.

The diagnosis of HF may be a challenge because many women in their final month of pregnancy experience symptoms identical to early HF. Progressive dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea and recumbent cough are likely to be indicative of HF.

On physical examination, healthy pregnant women may hyperventilate but the rate of respiration should be normal. Pulmonary crackles are rarely observed in normal pregnancy and their presence suggests HF. The jugular venous pulsation may be mildly distended with an exaggerated X and Y descent in normal pregnancy.

With echocardiography, cardiac chambers are normal or slightly enlarged, and atrioventricular valve regurgitation increases mildly during pregnancy. Diastolic dysfunction may be observed in patients with severe pre-eclampsia, although this is an uncommon cause of HF in pregnant women. Normal cardiac structures and preserved LVEF suggests a noncardiac cause for symptoms.

Clear diagnostic criteria for B-type natriuretic peptide/N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels and HF in the pregnant patient are not yet available; however, normal levels make HF very unlikely.

Noncardiac conditions that may mimic decompensated HF include pneumonia, pulmonary embolus, amniotic fluid embolus, renal failure with volume overload and acute lung injury, while cardiac failure may be secondary to myocardial infarction or severe pre-eclampsia.

The risk of thromboembolism associated with PPCM is increased due to the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy, and is highest during the first four weeks postpartum.

To optimize outcome in high-risk populations, tertiary regional centres should have a multidisciplinary team with expertise in management of HF in pregnancy, which should include obstetrical, anesthesia and neonatology specialists, as well as cardiology expertise in HF.

Pain control during delivery is very important in patients with limited cardiac reserve because pain results in tachycardia and may precipitate cardiac decompensation.

Patients should be monitored carefully throughout labour, but also in the early postpartum period, when decompensation may also occur. In women at highest risk, close monitoring in an intensive care unit or cardiac care unit for the first 24 h to 48 h may be useful.

Medications that may be used for pregnant women with HF are shown in Table 4. A more comprehensive list of medications is available at www.motherisk.org.

TABLE 4.

Medications that may be useful for pregnant women with heart failure (HF)

| Medication | Use in pregnancy |

|---|---|

| Beta-blockers | Should be continued or initiated during pregnancy Requires close fetal monitoring for growth retardation Beta-1 selective antagonists preferred to avoid potential increased uterine tone and decreased uterine perfusion |

| Digoxin | May be used if volume overload symptoms persist despite vasodilator and diuretic therapy |

| Diuretics | May be used, but with caution regarding excessive volume contraction leading to reduced placental perfusion |

| Hydralazine | May be used for management of HF symptoms or elevated blood pressure |

| Nitrates | May be used to treat decompensated HF in pregnancy |

Hemodynamic changes of normal pregnancy and precipitation of HF

During the course of pregnancy, there are a large number of pregnancy-induced hemodynamic changes in the cardiovascular system, which are summarized in Table 5 (57–64). During the peripartum period, further changes are noted as well (65–68). Maternal position can have a significant effect on cardiac output. In the supine position, the gravid uterus can cause vena cava compression resulting in decreased venous return and decreased cardiac output by as much as 25% (69). There is a further increase in cardiac output due to sympathetic stimulation, pain and the autotransfusion of blood from the placenta, while systemic resistance may increase due to these changes and the loss of the low-resistance placenta circuit. Within 1 h of delivery, cardiac output returns to third trimester values. Hemodynamic changes do not fully return to baseline until six months postpartum.

TABLE 5.

Hemodynamic changes in normal pregnancy

| Parameter |

Trimester |

Peripartum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Second | Third | ||

| Blood volume | Rises | Rises | Maximum at 45%–50% early on, additional 33% increase in twin gestation | Potential rapid autotransfusion from placenta due to sympathetic stimulation and uterine contraction |

| Peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure | Gradual drop, diastolic more such that pulse pressure increases | At lowest point in mid pregnancy | Gradual reversion to normal | Variable changes depending on stage and sympathetic stimulation |

| Heart rate | Increases | Peaks at 20% increase late | 20% increase | Further increase |

| Cardiac output | Increases | Increases | Maximal 30%–50% increase early | Further increase up to 31% in labour, 49% in second stage. Return to 3rd trimester values within 1 h of delivery |

While these changes are well tolerated by healthy women, those with heart disease can decompensate. It is essential to be familiar with these cardiovascular adaptations because women with a new-onset or pre-existing left ventricle dysfunction may exhibit marked clinical deterioration during the course of pregnancy (Table 5).

Common causes of HF in women of childbearing age

Congenital heart disease;

Valvular heart disease;

Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy;

Familial cardiomyopathies;

Drug-induced (ie, adriamycin) cardiomyopathy;

PPCM;

Ischemic cardiomyopathy; and

Hypertension-related cardiomyopathy.

During pregnancy, women with new or pre-existing left ventricular dysfunction are at risk for developing pulmonary edema as well as supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias. Rarely, cardiac transplants may be necessary and deaths can occur (70,71). Cardiac decompensation can occur anytime during pregnancy; however, there are specific periods when the risk is increased. Clinical deterioration can occur late in the second trimester, during the third trimester or in the peri-partum period, which is high risk due to rapid hemodynamic changes that take place.

Evaluation of HF in pregnancy

The diagnosis and evaluation of HF in pregnancy is more challenging than in nonpregnant patients. Such changes may result in symptoms and signs that can mimic HF. A high index of suspicion for cardiac diseases is essential to identify those at risk (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Cardiovascular symptoms and signs, and the pregnant state

| Findings | Noted in normal pregnancy | Not seen in normal pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Dizziness, palpitations | Common | Syncope on exertion |

| Dyspnea | Common (75%) if mild, not progressive | Progressive or New York Heart Association functional class IV |

| Orthopnea | Common, especially late in term | |

| Decreased exercise capacity | Mild, not progressive | New York Heart Association functional class IV symptoms |

| Chest pain | Common, may be musculoskeletal in origin, not progressive. Not typically anginal | Typical angina pain, severe or tearing pain may be dissection, especially late in term/peripartum |

| Pulse | Increased volume, rate | Decreased volume or upstroke |

| Peripheral edema | Mild, common | Severe or progressive edema |

| Apical beat | Mildly displaced laterally, hyperdynamic | Double or triple apex beat, thrill |

| Heart rate | Sinus tachycardia common | Atrial fibrillation, persistent supraventricular tachycardia, symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias |

| Neck veins | May be mildly distended | Progressively distended with dominant V wave |

| Heart sounds | Increased S1, S2, S3 common Systolic ejection murmur common; continuous murmur (venous hum, mammary souffle) not common |

Opening snap, pericardial rub, S4 Late peaking systolic murmur, diastolic murnur, other continuous murmurs |

Distinguishing the symptoms and signs of a normal pregnancy from those of HF requires careful clinical assessment (72,73). The principal findings are noted in Table 6. The 12-lead electrocardiogram in normal pregnancy frequently shows sinus tachycardia and nonspecific ST-T wave changes, and may show atrial and/or ventricular ectopy. Changes of left atrial enlargement or left ventricular hypertrophy may be related to heart position (74).

The initial assessment of suspected HF in the pregnant patient should include a detailed history to document functional status, physical examination, electrocardiography and echocardiography to assess whether pregnancy-related cardiovascular changes are likely to be tolerated. Echocardiography is the noninvasive investigation of choice in pregnancy because it provides important cardiac structural and functional information and does not involve exposure to radiation (75,76). It should be arranged urgently in the setting of suspected HF in the pregnant patient. Measurement of plasma B-type natriuretic peptide may be useful in confirming a diagnosis of HF when the diagnosis is not clear (77–79). Bloodwork should include complete blood count, electrolytes, renal function and thyroid-stimulating hormone. The use of x-ray in pregnant women (with fetal shielding in place) should be used only if judged clinically essential. Coronary angiography is rarely required.

Noncardiac conditions that may mimic decompensated HF include pneumonia, pulmonary embolus, amniotic fluid embolus, renal failure with volume overload and acute lung injury, while cardiac failure may be secondary to myocardial infarction or severe pre-eclampsia.

Pregnancy and chronic cardiovascular disease

In addition to this, four major maternal cardiac conditions are associated with a very high (up to 50%) maternal risk for mortality during or after pregnancy – ongoing HF with an LVEF of less than 35%, pulmonary hypertension, Eisenmenger’s syndrome and Marfan syndrome with an enlarged aortic root. Most experts consider pregnancy to be contraindicated in these settings. Patients with cardiac conditions and prepregnancy New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I or II symptoms tolerate pregnancy well with a mortality rate of less than 1%, while those in classes III and IV have a mortality rate of 5% to 15% (80). A prospective, observational study (81,82) examining maternal cardiac events in patients with pre-existing cardiac disease was undertaken. In this study, four conditions were shown to be predictors of adverse maternal events (primarily HF or hospitalization) – maternal NYHA functional class III or IV, or cyanosis before pregnancy; history of transient ischemic attack, HF or arrhythmia; left heart obstructive lesions; and left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF of less than 40%). A score outlining a risk of events based on the number of predictors was generated and validated in their dataset (Table 3). Given the increased rate of maternal events, we recommend that the pregnant patient with one or more of these conditions should be referred early to a cardiac specialist in maternal cardiology. Paradoxically, pregnant patients with a cardiovascular condition may also be prescribed unnecessary therapies (activity limitation, caesarean section). As such, these patients may benefit from consultation by physicians with expertise in maternal cardiology (83).

In addition, maternal conditions associated with unfavourable neonatal events following pregnancy include anticoagulation, an NYHA class of greater than II or cyanosis before pregnancy, left ventricular inflow or outflow tract obstruction, smoking and multiple gestations (81,84).

Women with HF during pregnancy should be followed closely. To optimize pregnancy outcome in this population, a multidisciplinary management team should be established, including obstetrical, cardiac, anesthesia and neonatology specialists. Pregnant women with underlying cardiac disease will tend to initially develop worsening HF symptoms during the second trimester of pregnancy, although symptoms may occur or worsen at any time, including postpartum. Once HF is diagnosed, efforts to treat volume overload should be undertaken, but with judicious care to avoid rapid volume removal or depletion.

Anesthetic considerations

Pregnant women with chronic or new-onset HF require specialized anesthetic management during labour and delivery. Prepartum anesthetic evaluation is recommended for planning of optimal monitoring and the anesthetic approach. The goals of management of anesthesia in these patients are avoidance of excessive anesthetic-induced myocardial depression, maintenance of normovolemia, attenuation of increases in systemic vascular resistance, and minimization of myocardial wall stress and sympathetic stimulation associated with pain (85).

The decision regarding timing and mode of delivery should be made for obstetrical reasons: early delivery is not required unless medical management is unsuccessful and the patient is hemodynamically deteriorating. Induction of labour is not contraindicated and vaginal delivery is preferable to caesarean delivery unless necessary for obstetrical reasons. Early administration of labour anesthesia is very important in patients with limited cardiac reserve because pain results in tachycardia and may precipitate cardiac decompensation.

Patients should be monitored carefully with noninvasive blood pressure, continuous maternal electrocardiography, tocodynamometry with fetal heart rate monitoring throughout labour and the early post-partum period when decompensation is most likely to occur. Maternal pulse oximetry is reserved for those at highest risk. More invasive monitoring with central venous, pulmonary artery and systemic pressure is indicated in the setting of the hemodynamically compromised or unstable patient, or when fluid volume monitoring is critical.

There is no consensus as to the optimal technique of labour anesthesia. Epidural anesthesia, if introduced slowly and carefully, produces changes in preload and afterload that may be advantageous in the setting of reduced ventricular function (86,87). Caution must be taken to avoid sudden sympathetic blockade. Spinal or combined spinal-epidural anesthesia (with or without caesarean section) with the use of spinal opioids rather than spinal local anesthetics, has been suggested to provide adequate analgesia with less hemodynamic instability (88–90). Other anesthetic or obstetrical issues are discussed in detail elsewhere (91,92).

PPCM

Definition

PPCM is defined as a dilated cardiomyopathy (LVEF of less than 45%) with the development of HF in the last month of pregnancy or within five months after delivery, in the absence of a demonstrable cause for HF and in the absence of documented heart disease before the last month of pregnancy (93,94). HF presenting earlier than the last month of pregnancy may be part of the same spectrum of disease, despite not meeting traditional criteria, and these patients tend to have the same demographics, degree of cardiac dysfunction and prognosis (95). The incidence of PPCM varies widely geographically, ranging from an incidence of one per 2289 to one per 4000 live births in the United States (96,97), to an incidence of one per 300 live births in Haiti (96). Risk factors for the development of PPCM include the following (85,93):

Multiparity;

Multiple fetus gestations;

Older maternal age (older than 30 years);

History of gestational hypertension;

African descent;

Maternal cocaine use; and

Long-term oral tocolytic therapy.

The cause of PPCM is unknown but certain etiologies have been considered including nutritional deficiencies, various viral infections (98–100), myocarditis (101–104), myocyte apoptosis (105,106), development of maternal cardiac autoantibodies (107,108) and oxidative stress linked to proteolysis’ cleavage of prolactin into a potent cardiotoxic subfragment (109).

In a pregnant woman presenting with new-onset HF, the diagnosis of PPCM is made by documenting reduced LVEF and by ruling out other potential causes of cardiac dysfunction. It is particularly important to assess for the presence of pre-eclampsia, infections, thyroid dysfunction and toxins (eg, ethanol or cocaine). In some cases, coronary artery disease needs to be excluded. While stress echocardiography may be the safest test to assess for coronary artery disease during pregnancy, in the setting of acute cardiac decompensation and evidence of potential ischemic etiology, coronary angiography with view to revascularization may be performed with the use of abdominal shielding.

The treatment and goals of therapy for PPCM are similar to the management of chronic systolic HF in pregnant women. Case reports have indicated improvement in patients with PPCM treated with bromocriptine (110), but no high-quality data exist for this therapy or for immunomodulatory (ie, intravenous immunoglobulin) agents. Patients who deteriorate or who fail to respond to standard antifailure therapy should be considered early on for transfer to a centre of excellence in advanced HF for consideration of mechanical circulatory support or other therapies such as cardiac transplantation (111).

Prognosis

With appropriate medical therapy, approximately 50% of patients with PPCM will recover cardiac function, usually within six months (112,113). If symptoms persist longer than this, myocardial damage is more likely irreversible, although recovery can occur with optimal medical therapy up to and beyond 12 months (114,115). However, even in women with echocardiographically recovered ventricular function, contractile reserve may be impaired (116). Mortality rates range between 10% and 23%, with death being attributed to pump failure, sudden cardiac death and thromboembolic events (117). Recovery is less likely in women with increased left ventricular dimension (larger than 5.6 cm) and those with left ventricular thrombus (112). The outcome of PPCM requiring cardiac transplantation (4% to 7% of patients) is good, with survival similar to patients undergoing transplantation for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. The risk of worsening cardiac function in subsequent pregnancies is largely dependent on the extent of subsequent left ventricular recovery. The risk of poor outcome of subsequent pregnancy is high in patients with incomplete left ventricular recovery. Even in patients with recovered left ventricular function, there is an increased risk of complications including recurrent HF and reduced LVEF with subsequent pregnancy (118,119).

ACUTE DECOMPENSATED HF DURING PREGNANCY

In general, patients presenting with acute decompensated HF in pregnancy should be managed according to the CCS acute decompensated HF management algorithm (77). In patients with worsening HF or difficult-to-manage pulmonary edema in the setting of preserved blood pressure, intravenous vasodilators such as nitrates can be used with close monitoring. The use of nesiritide in this setting has not been studied, and should only be considered if believed to be essential to management. Nitroprusside is not recommended except in the setting of an acute need for significant afterload reduction where all other interventions have been insufficient, due to the risk of fetal cyanide toxicity. When decompensation is associated with hypotension, unresolved pulmonary edema and/or evidence of organ hypoperfusion, inotropic support with dopamine, dobutamine or milrinone should be considered depending on the clinical scenario. In the setting of severe hypotension requiring vasopressor support, dopamine may be less deleterious to uterine blood flow than phenylephrine or noradrenaline. In the setting of cardiogenic shock, an intra-aortic balloon pump may be considered; however, these patients are best managed by urgent transfer to a centre with expertise and capability to provide mechanical circulatory support and/or cardiac transplantation. Because many women will recover cardiac function in the setting of PPCM, listing for cardiac transplantation is usually delayed until absolutely necessary to allow for cardiac recovery.

DMPs

Recommendations

Specialized hospital-based clinics or DMPs staffed by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dieticians and other health care professionals with expertise in HF management should be developed and used for assessment and management of higher-risk (eg, two or more HF admissions in six months) HF patients. (Class I, level A)

Multidisciplinary care should include close follow-up, and patient and caregiver education in an outpatient HF clinic and/or through telemanagement or telemonitoring, or home visits by specialized HF health care professionals where resources are available. (Class I, level A)

Patients with recurrent HF hospitalization should be referred to a DMP by family physicians, emergency room physicians, internists or cardiologists for follow-up within four weeks of hospital or emergency department discharge, or sooner where feasible. (Class I, level A)

Practical tips

The optimal care model should reflect local circumstances, current resources and available health care personnel. In some situations, it may be beneficial to include HF care in an integrated model of care with other chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, which is related to the development of cardiovascular disease.

Integration of a DMP into a primary care setting with adequate specialist support may be the most feasible solution in certain health care settings.

Practical resources to aid in HF diagnosis and management should be made available across the continuum of community health care delivery.

Teaching patients to control their sodium and fluid intake, to weigh themselves daily and to recognize symptoms of worsening HF as well as providing an algorithm to adjust a patient’s diuretics are key strategies to clinical stability in patients with recurrent fluid retention.

HF (function) clinics may also provide a full range of treatment options including pharmacological, interventional, electrophysiological and surgical therapeutic options. Repeat contacts, including by telephone or Internet calls, by experienced health care professionals to HF patients, appears to be an important intervention in preventing recurrent HF hospitalizations.

Communication among relevant care providers for HF patients is essential to realize the benefits of DMPs.

In Canada, suggestions on how to set up a multidisciplinary HF (function) clinic are available at www.chfn.org. Routine follow-up and protocols are available at www.qhfs.org and www.sqic.ca.

HF mortality and morbidity remain high despite the available therapies, and management of these patients can be challenging. A DMP typically refers to multidisciplinary efforts to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of care for selected patients suffering from chronic conditions. These programs involve interventions designed to improve adherence to scientific guidelines and treatment plans (120). HF DMPs can be grouped into three overlapping categories – HF clinics, home-based care and telemonitoring. There have been a number of studies over the past 15 years examining the effects of DMPs for HF patients (121). The majority of these studies have been small single-centre studies. During the past few years, a number of systematic reviews and larger randomized controlled trials (122–127) have been performed to better estimate the effects of DMPs for HF patients on mortality and morbidity. These reviews generally found that DMPs reduce both all-cause and HF hospitalizations (122,123,125–127). One review (124) reported a trend to reduce hospitalization rather than a significant reduction. This may be due to a limited number of studies included in the analysis.

Pooled data from several meta-analyses (122,123,127) have demonstrated a significant reduction in mortality of 25%. Other studies have either not examined mortality (126) or examined it in a combined outcome of hospital readmission or death, showing an 18% decrease (125). One meta-analysis (124) demonstrated a nonsignificant 20% reduction in mortality (P=0.15), although this finding may be underpowered.

Since these meta-analyses were published, more recent data have been reported from a variety of sources. Data from smaller (single- and two-centre) studies (128–131) demonstrated a significant reduction in hospitalization and a trend toward a reduction in mortality. A larger study (428 patients) by Cleland et al (132) examining home telemonitoring (HTM) compared with either nurse telephone support (NTS) or usual care found that there was no statistically significant difference between groups for the number of days lost as a result of death or hospitalization. There was a trend for fewer days lost to death or hospitalization for those in the HTM group (12.7%) compared with the NTS (15.9%) or usual care (19.5%) groups, and significantly lower one-year mortality for NTS (27%) or HTM (29%) compared with usual care (45%).

There have been three studies with more than 1000 patients in each study published over the past few years (133–135). In a study by Galbreath et al (133), 1069 NYHA class I to IV patients (mainly NYHA class II to IV) with systolic or diastolic dysfunction were randomly assigned to receive DMP or usual care for 18 months. The DMP consisted of telephone monitoring by disease managers with recommendations made to the patient’s primary care physician. Patients in this group also received bathroom scales to monitor weight and a toll-free number they could call 24 h/day, seven days/week. Telephonic DMP was found to reduce mortality (P=0.037) with a trend toward improvement in cardiac event-free survival (P=0.074). When the analysis was restricted to the group of patients with systolic dysfunction, there was a reduction (P=0.012) in both mortality and improvement in cardiac event-free survival. This benefit in systolic HF patients was greatest in those most severely ill (mortality for treatment group for NYHA class I HR 1.32, P value nonsignificant; NYHA class II HR 0.76, P value nonsignificant; NYHA class III/IV HR 0.54, P=0.048). In patients with preserved LVEF, there was no significant benefit found for mortality or cardiac event-free survival. There was an improvement (P<0.001) in the NYHA score in the DMP. For those with systolic HF, there were significantly more patients (P=0.002) in the treatment group (54.4%) on guideline-recommended treatment compared with the control group (43.3%).

The randomized trial of telephone intervention in chronic HF (DIAL) (134) recruited 1518 mainly NYHA class II to III HF patients, with 20% having preserved LVEF (LVEF of greater than 40%) HF and 80% having reduced LVEF (LVEF of 40% or less) HF. All patients received usual care by an attending cardiologist with the intervention group also receiving education, counselling and monitoring by nurses through frequent telephone follow-up delivered from a single centre. The mean length of follow-up was 16 months (range seven to 27 months). In the treatment group, there was a significant reduction in the primary outcome of any cause death or HF admission (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.97; P=0.025), HF hospitalizations (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.91; P=0.003) and all-cause admissions (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.99; P=0.049), but not for mortality (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.23; P=0.69). In contrast to the Galbreath et al study, similar point estimates for HF hospitalization, adherence to HF therapy and quality of life were not different for the preserved and reduced LVEF groups of patients.

The Coordinating Study Evaluating Outcomes of Advising Counseling in HF (COACH) (135) was a multicentre randomized controlled trial in which 1023 patients were enrolled after hospitalization because of HF. Patients were assigned to one of three groups: a control group consisting of follow-up by a cardiologist; a basic support group with cardiologist and HF nurse follow-up that included education as well as strategies to improve adherence and the ability to contact the nurse if necessary; and an intensive support group that included every component of the basic support group plus monthly contact by the HF nurse – this group also received advice from a physiotherapist, a dietician and a social worker. There were two primary outcomes – one was a composite of HF hospitalization or death from any cause, and the other was the number of unfavourable days, defined as the number of days lost because of death or hospitalization during the 18 months of follow-up. There was no significant benefit for either primary outcome for the basic or intensive support groups compared with controls. However, the control group had unusually close follow-up throughout the study. This may have accounted to some extent for the lack of difference in the primary outcome in the intervention group compared with the control group. For the two intervention groups combined, there was a trend toward a reduction in mortality (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.08; P=0.18).

The long-term benefits of a DMP are not as well established because the studies to date have not examined whether the benefits of these programs continue after the patient is referred back to their primary care physician. A recent study by Nguyen et al (136) examined the long-term benefit of a six-month DMP. In this study, patients were randomly assigned to DMP or usual care for six months and then at the end of this time, followed for a mean of 2.8 years. At the end of 2.8 years of follow-up, there were no differences between the DMP and usual care with regard to the primary outcome of all-cause death, hospital admissions and emergency room visits (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.37). These findings suggest the possibility that long-term follow-up is required after the initial exposure to a DMP and that it may not be possible to discharge these patients from the DMP without first enhancing the capacity of primary care physicians to manage HF. Another important area that has not been well explored is whether men and women are equally enrolled in DMPs and whether they derive the same benefits. A recent study has addressed this question and examined the records of 765 patients referred to one of three DMPs in Montreal, Quebec (137). The LVEF and NYHA functional class at entry were similar among men and women with a reduced LVEF. Among patients with preserved LVEF, women were more symptomatic, with a greater NYHA class at entry into the DMP (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.18 to 5.38). The prescription profiles were similar between men and women. These findings suggest that for reduced LVEF HF, there is no difference with regard to referral. However, when HF is associated with preserved LVEF, there may be a delay in referring women to a DMP.

The DMPs assessed have had variable structures, the studies for the most part have involved only a single centre and the sample sizes have been relatively small. Because of this, it has been difficult to define the best type of DMP for HF patients. However, the published overview analyses have been able to provide some direction with regard to the most effective type of DMP. Multidisciplinary programs involving both a doctor and a nurse specializing in HF management appear to be a consistent requirement for these programs, with the potential for further benefit from the addition of other allied health professionals such as a pharmacist (122,123,126,127,138). Combinations of in-clinic and telephone follow-ups would appear to be important with entry into the DMP as soon as possible after discharge (122,124,125). The DMP should involve education, exercise and psychosocial counselling, self-care supportive strategy, optimization of the medication regimen and medical referrals for deterioration (122,124,125,127).

The majority of data suggest a DMP is of benefit for HF patients. Whether a DMP is a cost-effective way to manage these patients is not well established. The studies suggest a DMP may be cost effective or the extra cost associated with a DMP is acceptable (131,139–142). In a recent analysis by Whellan et al (143), an interesting concept based on the American system of reimbursement is presented. This paper suggested that although DMPs may provide patients with improved clinical outcomes and decreased hospitalizations that save third-party payers money, limited financial incentives are currently in place for health care providers and hospitals to initiate these programs.

QUALITY ASSURANCE AND HF

Recommendations

Health care systems should provide for quality assurance in both the process and content of care provision. (Class I, level C)

- Quality assurance programs should ensure the following to improve adherence to HF guidelines and improve patient outcomes (Class I, level B):

- ○ Use evidence-based performance indicators to identify care gaps in the management of HF in a particular population.

- ○ Provide intervention supports such as clinical tools or practice change to facilitate best practices.

- ○ Provide feedback and education to assist HF care professionals meet these performance indicators.

Practical tips

Selection of performance indicators that have been associated with improved patient outcomes in randomized clinical trials is preferred.

Quality improvement initiatives that combine practice audits with multifaceted, proscriptive education strategies are preferred.

Recent reviews also suggest the greatest gain in terms of quality of care is system change with an emphasis on the multidisciplinary team approach.

Strategies shown to result in improved care processes and/or outcomes usually have included administrative support, change management support, resource support and a physician champion.

Broader regional, provincial and national frameworks are required to promote and facilitate quality assurance initiatives at all levels of HF care.

Quality assurance: What is it?

The Institute of Medicine (144) defines quality of care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge”. In addition to whether care for a particular condition achieves desired health outcomes, other considerations in gauging quality of care include accessibility, the quality of the patient experience when receiving care, and how the processes of care delivery are structured in a manner to constrain health care costs (145–147).

Quality assurance is a process whereby a health care organization can ensure that the care it delivers for a particular illness meets accepted quality standards (144,145). Inherent characteristics of this process include the following:

Existence of evidence-based clinical guidelines for the illness of interest, and from which quality of care performance indicators can be derived. These indicators can refer to structures, processes or outcomes of care (148,149).

Development and maintenance of a health information database representative of the patients served by the health care organization and pertinent to the illness of interest. The database can be audited and benchmarked against the performance indicators to assess the quality of care.

Development of mechanisms to address care deficiencies identified in the database audit and improve the quality of care. More in-depth evaluative work may be required to understand causes of these deficiencies and to inform potential care improvement strategies.

Repeated database audits to assess the effectiveness of measures taken to improve care delivery, and to ensure the ongoing delivery of quality care.

Quality assurance considerations for HF care

Chronic HF is a common health condition associated with a significant clinical and economic burden of illness, and has been identified as a priority condition for quality assurance (144). While recent evidence suggests modest improvements in HF-related outcomes (150), the care provided to many HF patients, particularly those who are elderly, still fails to meet the standards set out in the CCS recommendations on HF (151–155).

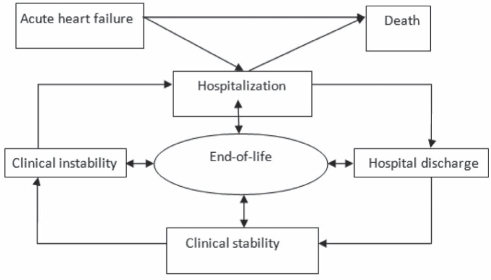

Applying quality assurance methods to chronic HF requires consideration of the often unpredictable illness trajectory, characterized by periods of relative stability that are punctuated by episodes of acute decompensation (156). This may be conceptualized as in Figure 2, which illustrates the HF cycle, components of which are potential objects for quality assurance, and which include the following:

Periods of acute decompensation that may last from days to weeks, and may culminate in resolution, hospitalization or death.

Hospitalization phase, from admission to either death or discharge.

Transition period, from hospital discharge to the resumption of outpatient care.

Chronic, apparently stable outpatient phase.

Figure 2).

The heart failure cycle

At all stages of the HF cycle, there is continuing reference to end-of-life planning and care.

What performance indicators have been developed for HF?

It is neither feasible nor necessary to adapt all recommendations in HF guidelines as performance indicators. Accordingly, several organizations have developed through consensus processes restricted sets of performance indicators deemed sufficiently representative of the guidelines to be considered indicators of quality HF care. These organizations include the Canadian Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Team (CCORT)/CCS (157), the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (158), the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) (159), and the Assessing the Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) project (160), and are summarized in Table 7. It is unclear which, if any, set of performance measures is superior in gauging the quality of HF care. All have the drawback of focusing on the hospital and transition phases of HF, and do not address the processes of health care delivery. They do, however, share several core performance indicators including the use of ACE inhibitors in eligible patients, the importance of appropriate patient education and the assessment of left ventricular function.

TABLE 7.

Summary of performance indicators for heart failure (HF) by development group

| Indicator | CCORT inpatient (157) | CCORT outpatient (157) | Canadian primary care (196) | AHA/ACC inpatient (158) | AHA/ACC outpatient (158) | JCAHO (159) | OPTIMIZE-HF (176) | ACOVE (160) | IMPROVE HF (179,180) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutics | |||||||||

| ACEi and/or ARB if LV systolic dysfunction in eligible patients | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Use of beta-blockers (evidence based or not) in eligible patients | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Use of statins in eligible patients if underlying CAD, PVD, CVD or diabetes | x | ||||||||

| Aldosterone antagonists for eligible patients | x | x | x | ||||||

| Anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Use of ICD in eligible patients | x | ||||||||

| Use of CRT in eligible patients | x | ||||||||

| Avoid 1st and 2nd generation CCBs if LV systolic dysfunction | x | ||||||||

| Avoid type 1 antiarrhythmic agents if LV systolic dysfunction (unless ICD in place) | x | ||||||||

| Investigations | |||||||||

| Outpatient assessment including one or more of regular volume assessment, weight, blood pressure, activity level | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Appropriate baseline blood/urine tests, ECG, CXR | x | x | |||||||

| Appropriate biochemical monitoring of renal function and electrolytes | x | x | x | ||||||

| Assessment of LV function | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Measure digoxin levels if toxicity suspected | x | ||||||||

| Education and follow-up | |||||||||

| HF patient education/discharge instructions | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Outpatient follow-up within 4 weeks | x | ||||||||

| Advice on smoking cessation | x | x | x | ||||||

Please refer to primary references for specific details regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria, and implantation requirements for each quality indicator. ACEi Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACOVE Assessing the Care of Vulnerable Elders Project; AHA/ACC American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology; ARB Angiotensin Receptor Blocker; CAD Coronary artery disease; CCB Calcium channel blocker; CCORT Canadian Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Team; CRT Cardiac resynchronization therapy; CVD Cerebrovascular disease; CXR Chest x-ray; ECG Electrocardiogram; ICD Implantable cardioverter defibrillator; IMPROVE HF Registry to Improve the Use of Evidence-Based Heart Failure Therapies in the Outpatient Setting; JCAHO Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; LV Left ventricle; OPTIMIZE-HF Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure; PVD Peripheral vascular disease

What care improvement mechanisms should be considered?

Numerous initiatives to improve the management of HF have been developed and evaluated in different care settings, and have met with varying degrees of success. Strategies used in these initiatives have included passive dissemination of educational information to health care providers and patients, computerized order sets, automatically generated suggestions for care interventions, automated reminders attached to echocardiography results, as well as intensive education, direct feedback and care support from expert clinicians (161–171). Strategies that rely on passive dissemination of information to health care providers are, at best, modestly effective (162,167,168). More proscriptive strategies, either through computerized order sets or direct feedback and support from specialists, may be more successful. Involvement of end users in the development of strategies for improving HF care may increase their likelihood of success (164,172). A systematic review (173) of computerized decision support for prescribing suggested that most studies resulted in improved prescribing, although few reported on patient-relevant outcomes. Another systematic review (174) suggested that strategies that combine practice audits with feedback regarding gaps between the care provided for a particular condition and clinical practice guidelines have small to moderate effects on improving care quality. However, the effects may be larger when baseline adherence to clinical guidelines is low and intensity of audit and feedback is high. Multifaceted interventions may also be more likely to succeed (174). Recent reviews also suggest that the greatest gain in terms of quality of care is system change with an emphasis on the multidisciplinary team approach.

Quality assurance in HF: What is the evidence?

A number of large prospective registry-based programs aiming to improve the quality of HF care are underway in the United States. Results from a study of 3657 US hospitals (175), in which hospital-reported performance measures were linked to Medicare claims data, suggested that two HF care quality indicators (assessment of left ventricular function and use of ACE inhibitors in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction) were only marginally associated with improvements in mortality rates at 30 days and one year.

The Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) (176) was a large prospective registry targeting hospitalized patients admitted with HF or who develop HF during hospitalization. Data were collected regarding the JCAHO and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association performance indicators for HF, as well as for performance indicators developed specifically for the registry, which include the use of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), aldosterone antagonists and beta-blockers for eligible patients without contraindications (Table 7). Health care providers were encouraged to attend workshops and rounds. Evidence-based pathways, algorithms and standardized orders were provided to guide patient care, and an Internet-based tool provided participating institutions with real-time quality-of-care reports and benchmark comparisons with other institutions.

During a two-year period from January 2003 to December 2004, the OPTIMIZE-HF program was associated with increased use of evidence-based beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, statins and anticoagulants in eligible patients, and continued high prescription rates for ACE inhibitors and ARBs (176,177). The program was also associated with an increase in the use of discharge education, smoking cessation counselling and assessment of left ventricular function (176,177). The use of computerized tools was associated with lower inpatient mortality (4.1% versus 2.5%, P<0.001), postdischarge mortality and readmissions (34.8% versus 38.2%, P=0.02; which was no longer significant after propensity risk adjustment) (177). Further data from OPTIMIZE-HF (178) suggested that of all indicators, only beta-blocker prescription was associated with a 52% reduction in mortality (95% CI 0.21 to 0.70) at 90 days. Only the use of ACE inhibitors for patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction was associated with reduced combined mortality and rehospitalization at three months.