Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To provide updated, evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and assessment of adults with hypertension.

EVIDENCE:

MEDLINE searches were conducted from November 2008 to October 2009 with the aid of a medical librarian. Reference lists were scanned, experts were contacted, and the personal files of authors and subgroup members were used to identify additional studies. Content and methodological experts assessed studies using prespecified, standardized evidence-based algorithms. Recommendations were based on evidence from peer-reviewed full-text articles only.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

Recommendations for blood pressure measurement, criteria for hypertension diagnosis and follow-up, assessment of global cardiovascular risk, diagnostic testing, diagnosis of renovascular and endocrine causes of hypertension, home and ambulatory monitoring, and the use of echocardiography in hypertensive individuals are outlined. Changes to the recommendations for 2010 relate to automated office blood pressure measurements. Automated office blood pressure measurements can be used in the assessment of office blood pressure. When used under proper conditions, an automated office systolic blood pressure of 135 mmHg or higher or diastolic blood pressure of 85 mmHg or higher should be considered analogous to a mean awake ambulatory systolic blood pressure of 135 mmHg or higher and diastolic blood pressure of 85 mmHg or higher, respectively.

VALIDATION:

All recommendations were graded according to strength of the evidence and voted on by the 63 members of the Canadian Hypertension Education Program Evidence-Based Recommendations Task Force. To be approved, all recommendations were required to be supported by at least 70% of task force members. These guidelines will continue to be updated annually.

Keywords: Blood pressure, Diagnosis, Guidelines, High blood pressure, Hypertension, Risk factors

Abstract

OBJECTIF :

Fournir des recommandations probantes et à jour pour le diagnostic et l’évaluation des adultes hypertendus.

DONNÉES PROBANTES :

Des recherches dans MEDLINE ont été exécutées entre novembre 2008 et octobre 2009 avec l’aide d’un bibliothécaire médical. On a dépouillé les listes de référence, communiqué avec des experts et utilisé les dossiers personnels des auteurs et des membres des sous-groupes pour repérer d’autres études publiées. Des spécialistes du contenu et de la méthodologie ont évalué les études au moyen d’algorithmes normalisés, probants et préétablis. Les recommandations sont fondées sur des données probantes tirées d’articles intégraux révisés par des pairs.

RECOMMANDATIONS :

Le présent document contient des recommandations sur la mesure de la tension artérielle, les critères de diagnostic et de suivi de l’hypertension, l’évaluation du risque cardiovasculaire global, les tests diagnostiques, le diagnostic des causes rénovasculaires et endocriniennes de l’hypertension, la surveillance ambulatoire et à domicile et le recours à l’échocardiographie chez les hypertendus. Les changements aux recommandations pour 2010 portent sur les mesures automatisées de la tension artérielle en cabinet. On peut utiliser ces mesures dans l’évaluation de la tension artérielle en cabinet. Lorsqu’on les utilise dans les bonnes conditions, une tension artérielle systolique de 135 mmHg ou plus ou diastolique de 85 mmHg ou plus doit être considérée comme analogue à une tension artérielle systolique ambulatoire moyenne pendant l’éveil de 135 mmHg ou plus et diastolique de 85 mmHg ou plus, respectivement.

VALIDATION :

Toutes les recommandations sont classées selon la solidité des données probantes, et les 63 membres du groupe de travail des recommandations probantes du Programme éducatif canadien sur l’hypertension ont exercé leur vote à leur égard. Pour être approuvées, toutes les recommandations devaient obtenir un consensus d’au moins 70 % de la part des membres du groupe de travail. Les présentes lignes directrices continueront d’être mises à jour chaque année.

Hypertension affects 27% of the Canadian adult population 35 to 64 years of age (1), and remains one of the most common modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease in Canada and globally (2,3). The present document summarizes the 2010 Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) recommendations for the diagnosis and assessment of hypertension in adults, focusing on those recommendations that are new or updated. For issues related to the diagnosis and evaluation of high blood pressure (BP) in children and adolescents, the reader is referred to separate guidelines (4). A more detailed discussion of previous changes to the Canadian recommendations is available in previous publications (5–10). Summary documents of all recommendations, including downloadable slide kits, are available free of charge on the Canadian Hypertension Society Web site (www.hypertension.ca).

METHODS

The previously published methodology remains unchanged (11) and was previously detailed (12). In brief, grade A recommendations are based on studies with high levels of internal validity, statistical precision, generalizability and clinical relevance. Grade B and C recommendations are derived from studies characterized by lower internal validity, precision or generalizability, or from studies reporting intermediate/surrogate outcomes instead of more clinically relevant ones. Grade D recommendations are based on expert opinion or studies with lower levels of internal validity or precision than grade C recommendations.

THE 2009 CHEP RECOMMENDATIONS

I. Accurate measurement of BP

Recommendations

Health care professionals who have been specifically trained to measure BP accurately should assess BP in all adult patients at all appropriate visits to determine cardiovascular risk and monitor antihypertensive treatment (grade D).

Use of standardized measurement techniques (Table 1) is recommended when assessing BP (grade D).

Automated office BP measurements can be used for the assessment of office BP (grade D).

When used under proper conditions, automated office systolic BP (SBP) values of 135 mmHg or higher or diastolic BP (DBP) values of 85 mmHg or higher should be considered analogous to a mean awake ambulatory SBP of 135 mmHg or higher and a DBP of 85 mmHg or higher, respectively (grade D).

TABLE 1.

Recommended technique for measuring blood pressure in the office*

|

Steps apply to measurement by auscultation and oscillometry using an upper arm cuff, with the exception of steps iv to vii, which are specific to auscultation.

Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

Background

Some fully automated BP measuring devices available for use in the clinic are capable of taking repeated BP measurements when a patient is alone in the examining room. Using repeat measure devices in this manner has been referred to as automated office BP (AOBP) measurement. The 2010 CHEP recommendations include the use of AOBP as a device for the assessment of office BP.

The therapeutic thresholds for interpreting automated readings remain undetermined and, at present, there are no studies that directly relate AOBP readings to the occurrence of cardiovascular events. Some studies (13,14) have shown that an AOBP reading of 135/85 mmHg is approximately equivalent to an ambulatory BP reading of 135/85 mmHg. One small study (15) in a selected population has related repeated automated office readings to repeated manual office readings (on which the current therapeutic thresholds are based). In a representative group of Ontario adults, the automated readings were 3/3 mmHg lower than manual readings at a single visit (16). In a small selected group of firefighters, the difference between automated and manual office readings disappeared over a span of three to five visits (15). Other studies have reported higher differences between automated office readings and manual office readings (17).

Research studies to date have often used populations that are likely to have had a high prevalence of white coat hypertension (ie, patients referred for ambulatory BP monitoring [ABPM]), used readings taken in a specialist’s office, used office readings that were taken on a single occasion, or used manual office readings that were not performed by a trained technician using standardized techniques (17,18). These limitations could increase the difference between automated and manual BP readings, limiting the ability to define the exact threshold for treating hypertension based on automated office readings in an unselected population of patients in a primary health care setting. Furthermore, it may be more appropriate to compare bands, or ranges of BP values, when comparing the different techniques rather than considering an AOBP reading of 135/85 mmHg to be equivalent to a manual office reading of 140/90 mmHg.

Further research is required to determine whether AOBP measurements can predict target organ damage and cardiovascular events better than manual office readings.

Several AOBP devices have been independently validated for clinical accuracy including the BpTRU automatic BP monitor (BpTRU Medical Devices, Canada – the most commonly used device in Canada), the BPM-100 electronic oscillometric office BP monitor, the Omron office digital BP HEM-907 monitor (Omron Canada Inc, Canada), and the Microlife WatchBP Office professional device (Microlife AG Swiss Corporation, Switzerland) (13,19–21). However, most of the available research in this area has been based on results obtained with the BpTRU device.

When used under proper conditions (Table 1), the available evidence suggests that repeat automated office SBP values of 135 mmHg or higher, or DBP values of 85 mmHg or higher, should be considered analogous to a mean awake ambulatory SBP reading of 135 mmHg or higher and a DBP of 85 mmHg or higher, respectively (13,14). Furthermore, it appears that the white coat effect may be reduced or even eliminated when the BpTRU device is used properly (22).

It is important to note that to date, only one article (23) has reported an association between AOBP readings and target organ damage; no data are available that relate AOBP readings to prognosis.

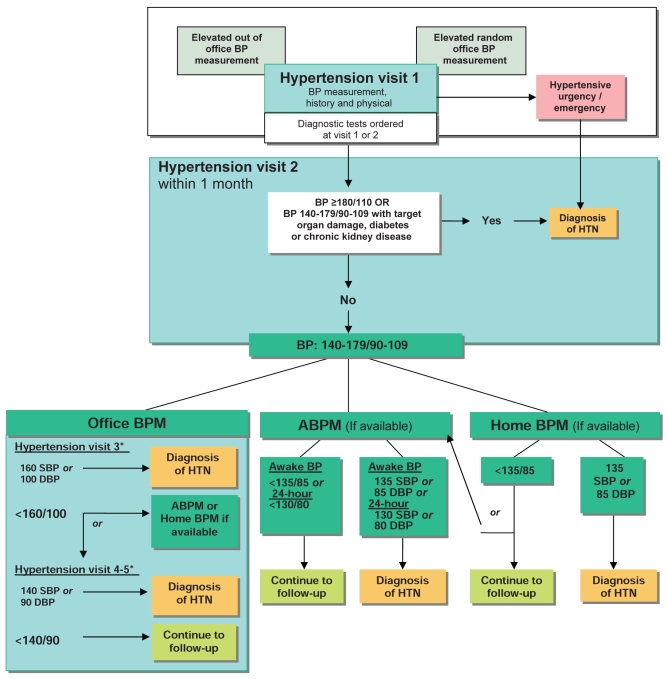

II. Criteria for diagnosis of hypertension and recommendations for follow-up (Figure 1)

Figure 1).

The expedited assessment and diagnosis of patients with hypertension (HTN): Focus on validated technologies for blood pressure (BP) assessment. *Thresholds refer to BP values averaged across the corresponding number of visits and not just the most recent office visit. ABPM Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BPM Blood pressure monitoring; DBP Diastolic blood pressure; SBP Systolic blood pressure. Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

Recommendations

At initial presentation, patients demonstrating features of a hypertensive urgency or emergency (Table 2) should be diagnosed as hypertensive and require immediate management (grade D).

If SBP is 140 mmHg or higher and/or DBP is 90 mmHg or higher, a visit should be scheduled specifically for the assessment of hypertension (grade D). If BP is high-normal (SBP 130 mmHg to 139 mmHg and/or DBP 85 mmHg to 89 mmHg), annual follow-up is recommended (grade C).

At the initial visit for the assessment of hypertension, if SBP is 140 mmHg or higher and/or DBP is 90 mmHg or higher, at least two more readings should be taken during the same visit using a validated device and according to the recommended procedure for accurate BP determination (Table 1). The first reading should be discarded and the latter two averaged. A history and physical examination should be performed and, if clinically indicated, diagnostic tests to search for target organ damage (Table 3) and associated cardiovascular risk factors (Table 4) should be arranged within two visits. Exogenous factors that can induce or aggravate hypertension should be assessed and removed if possible (Table 5). Schedule visit 2 within one month (grade D).

At visit 2 for the assessment of hypertension, patients with macrovascular target organ damage, diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease (CKD) (glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the SBP is 140 mmHg or higher and/or the DBP is 90 mmHg or higher (grade D).

- At visit 2 for the assessment of hypertension, patients without macrovascular target organ damage, diabetes mellitus and/or CKD can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the SBP is 180 mmHg or higher and/or the DBP is 110 mmHg or higher (grade D). Patients without macrovascular target organ damage, diabetes mellitus or CKD but with lower BP levels should undergo further evaluation using any of the three approaches outlined below:

- Office manual BP measurements: Using office manual BP measurements, patients can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the SBP is 160 mmHg or higher or the DBP is 100 mmHg or higher averaged across the first three visits, or if the SBP is 140 mmHg or higher or the DBP is 90 mmHg or higher averaged across five visits (grade D).

- ABPM measurements: Using ABPM (see section VIII), patients can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the mean awake SBP is 135 mmHg or higher or the DBP is 85 mmHg or higher, or if the mean 24 h SBP is 130 mmHg or higher or the DBP is 80 mmHg or higher (grade C).

- Home BP measurement: Using home BP measurements (see section VII), patients can be diagnosed as hypertensive if the average SBP is 135 mmHg or higher or the DBP is 85 mmHg or higher (grade C). If the average home BP is lower than 135/85 mmHg, it is advisable to perform 24 h ABPM to confirm that the mean 24 h ABPM value is lower than 130/80 mmHg and the mean awake ABPM value is lower than 135/85 mmHg before diagnosing white coat hypertension (grade D).

Investigations for secondary causes of hypertension should be initiated in patients with suggestive clinical and/or laboratory features (outlined below) (grade D).

If at the final diagnostic visit the patient is not diagnosed as hypertensive, and has no evidence of macrovascular target organ damage, the patient’s BP should be assessed at yearly intervals (grade D).

Hypertensive patients receiving lifestyle modification advice alone (nonpharmacological treatment) should be followed up at three- to six-month intervals. Shorter intervals (every one or two months) are needed for patients with higher BPs (grade D).

Patients on antihypertensive drug treatment should be seen monthly or every two months, depending on BP level, until readings on two consecutive visits are below their target (grade D). Shorter intervals between visits will be needed for symptomatic patients and those with severe hypertension, intolerance to antihypertensive drugs or target organ damage (grade D). Once the target BP has been reached, patients should be followed up at three- to six-month intervals (grade D).

TABLE 2.

Examples of hypertensive urgencies and emergencies

| Asymptomatic diastolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy |

| Acute aortic dissection |

| Acute left ventricular failure |

| Acute myocardial ischemia |

Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

TABLE 3.

Examples of target organ damage

| Cerebrovascular disease |

| Stroke |

| Ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage |

| Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| Dementia |

| Vascular dementia |

| Mixed vascular dementia and dementia of the Alzheimer’s type |

| Hypertensive retinopathy |

| Left ventricular dysfunction |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Coronary artery disease |

| Myocardial infarction |

| Angina pectoris |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Renal disease |

| Chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) |

| Albuminuria |

| Peripheral artery disease |

| Intermittent claudication |

Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

TABLE 4.

Examples of key cardiovascular risk factors for atherosclerosis

| Nonmodifiable |

| Age ≥55 years |

| Male sex |

| Family history of premature cardiovascular disease (age <55 years in men and <65 years in women) |

| Modifiable |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

| Poor dietary habits |

| Abdominal obesity |

| Dysglycemia |

| Smoking |

| Dyslipidemia |

| Stress |

| Nonadherence |

A history of clinically overt atherosclerotic disease (eg, peripheral arterial disease, previous stroke or transient ischemic attack) indicates a very high risk for a recurrent atherosclerotic event. Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

TABLE 5.

Examples of exogenous factors that can induce or aggravate hypertension

| Prescription drugs |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors |

| Corticosteroids and anabolic steroids |

| Oral contraceptive and sex hormones |

| Vasoconstricting or sympathomimetic decongestants |

| Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporin, tacrolimus) |

| Erythropoietin and analogues |

| Antidepressants: Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| Midodrine |

| Other substances |

| Licorice root |

| Stimulants including cocaine |

| Salt |

| Excessive alcohol use |

Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

Background

The criteria for the diagnosis of hypertension have been discussed in detail previously (24). It should be emphasized that when using manual office BPs to diagnose hypertension, the thresholds given above refer to readings averaged over the specified number of visits, and not solely on the last visit. There was considerable discussion about how best to incorporate the assessment of AOBP into the existing diagnostic algorithm for hypertension, but a consensus was not reached. This will be addressed further in the 2011 CHEP recommendations.

III. Assessment of overall cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients

Recommendations

Global cardiovascular risk should be assessed. Multifactorial risk assessment models can be used to more accurately predict an individual’s global cardiovascular risk (grade A) and to use antihypertensive therapy more efficiently (grade D). In the absence of Canadian data to determine the accuracy of risk calculations, avoid using absolute levels of risk to support treatment decisions (grade C).

Consider informing patients of their global risk to improve the effectiveness of risk factor modification (grade B).

Background

Recognizing the importance of global risk assessment as a component of hypertension therapy (25), the 2006 recommendations (26) included a detailed review of risk assessment tools (27) including the Framingham Heart Study model (www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/framingham/riskabs.htm) (28–31), the Cardiovascular Life Expectancy model (www.chiprehab.com) (32), and the Symptoms-Causes-Output-Resources-Effects (SCORE) model (www.scorecanada.ca) (33). Measurement of the ankle-brachial index may improve the accuracy of cardiovascular risk prediction beyond risk scoring alone (34).

Detailed guidelines for hypertension treatment based on absolute risk thresholds are not currently available given the lack of published studies examining the validity of these models in the Canadian population. Moreover, one’s absolute risk level may not be an accurate reflection of whether one’s risk is elevated compared with other individuals of the same age and sex. For instance, a woman younger than 40 years of age who smokes and has elevated BP can have a substantially increased RR of cardiovascular disease while her absolute risk remains well below 10% over the next 10 years. The problem is that absolute risk over the short term underestimates the lifelong impact of an increased RR. On the other hand, a 70-year-old man with mild isolated hypertension may have a 10-year risk above 20% while his RR is average compared with his peers. Absolute risk without consideration of RR may result in the over-treatment of older individuals and the under-treatment of younger individuals.

Global risk assessment in general, and the use of these models specifically, can be used as a tool to assist physicians in identifying subjects with hypertension who are most likely to benefit from therapy (35). When considering an individual’s future risk of developing cardiovascular disease and the potential impact of antihypertensive therapy, one should consider assessing both the risk of future cardiac as well as cerebrovascular events (36).

A number of recently published randomized clinical trials among individuals with dyslipidemia and/or hypertension have demonstrated that explicitly calculating a patient’s cardiovascular risk and discussing the results can significantly increase the likelihood of achieving treatment targets (37,38). These studies suggest that informed patients are more adherent to lifestyle recommendations and/or pharmacotherapy, while informed physicians are more effective at implementing treatment guidelines.

IV. Routine and optional laboratory tests for the investigation of patients with hypertension

Recommendations

- Routine laboratory tests that should be performed for the investigation of all patients with hypertension include:

- urinalysis (grade D);

- blood chemistry (potassium, sodium and creatinine) (grade D);

- fasting blood glucose (grade D);

- fasting serum total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides (grade D); and

- standard 12-lead electrocardiography (grade C).

Assess urinary albumin excretion in patients with diabetes (grade D).

- All treated hypertensive patients should be monitored according to the current Canadian Diabetes Association guidelines for the new appearance of diabetes (grade B).

- During the maintenance phase of hypertension management, tests (including those for electrolytes, creatinine and fasting lipids) should be repeated with a frequency reflecting the clinical situation (grade D).

Background

There are no changes to these recommendations for 2010.

V. Assessment for renovascular hypertension

Recommendations

- Patients presenting with two or more of the clinical clues listed below, suggesting renovascular hypertension, should be investigated (grade D):

- sudden onset or worsening of hypertension and age older than 55 years or younger than 30 years;

- the presence of an abdominal bruit;

- hypertension resistant to three or more drugs;

- a rise in serum creatinine level of 30% or more associated with the use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist;

- other atherosclerotic vascular disease, particularly in patients who smoke or have dyslipidemia; and

- recurrent pulmonary edema associated with hypertensive surges.

When available, the following tests are recommended to aid in the usual screening for renal vascular disease: captopril-enhanced radioisotope renal scan, Doppler sonography, magnetic resonance angiography and computed tomographic angiography (for those with normal renal function) (grade B). A captopril-enhanced radioisotope renal scan is not recommended for those with CKD (glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) (grade D).

Background

There are no changes to these recommendations for 2010.

VI. Endocrine hypertension

Recommendations

A. Hyperaldosteronism: Screening and diagnosis

- Screening for hyperaldosteronism should be considered for the following patients (grade D):

- hypertensive patients with spontaneous hypokalemia (K+ level lower than 3.5 mmol/L);

- hypertensive patients with marked diuretic-induced hypokalemia (K+ level lower than 3.0 mmol/L);

- patients with hypertension refractory to treatment with three or more drugs; and

- hypertensive patients found to have an incidental adrenal adenoma.

Screening for hyperaldosteronism should include assessment of plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity (Online Table 1; available at www.canjcardiol.com or www.pulsus.com).

For patients with suspected hyperaldosteronism (on the basis of the screening test, Online Table 1 [iii]), a diagnosis of primary aldosteronism should be established by demonstrating inappropriate autonomous hypersecretion of aldosterone using at least one of the manoeuvres listed in Online Table 1 (iv). When the diagnosis is established, the abnormality should be localized using any of the tests described in Online Table 1 (v).

B. Pheochromocytoma: Screening and diagnosis

If pheochromocytoma is strongly suspected, the patient should be referred to a specialized hypertension centre, particularly if biochemical screening tests (Online Table 2; available at www.canjcardiol.com or www.pulsus.com) have already been found to be positive (grade D).

- The following patients should be considered for screening for pheochromocytoma (grade D):

- patients with paroxysmal and/or severe (BP 180/110 mmHg or higher) sustained hypertension refractory to usual antihypertensive therapy;

- patients with hypertension and multiple symptoms suggestive of catecholamine excess (eg, headaches, palpitations, sweating, panic attacks and pallor);

- patients with hypertension triggered by beta-blockers, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, micturition or changes in abdominal pressure; and

- patients with incidentally discovered adrenal mass, patients with hypertension and multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A or 2B, von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis, or von Hippel-Lindau disease.

For patients with positive biochemical screening tests, localization of pheochromocytomas should employ magnetic resonance imaging (preferable), computed tomography (if magnetic resonance imaging is unavailable) and/or iodine-131 metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy (grade C for each modality).

Background

There are no changes to these recommendations for 2010.

VII. Home measurement of BP

Recommendations

Home BP readings can be used in the diagnosis of hypertension (grade C).

- The use of home BP monitoring on a regular basis should be considered for patients with hypertension, particularly those with:

- diabetes mellitus (grade D);

- CKD (grade C);

- suspected nonadherence (grade D);

- demonstrated white coat effect (grade C); and

- BP controlled in the office but not at home (masked hypertension) (grade C).

When white coat hypertension is suggested by home monitoring, its presence should be confirmed with ABPM before making treatment decisions (grade D).

Patients should be advised to purchase and use only home BP monitoring devices that are appropriate for the individual and have met the standards of the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, the most recent requirements of the British Hypertension Society protocol or the International Protocol for validation of automated BP measuring devices. Patients should be encouraged to use devices with data recording capabilities or automatic data transmission to increase the reliability of reported home BP values (grade D).

Home SBP values of 135 mmHg or higher or DBP values of 85 mmHg or higher should be considered elevated and associated with an increased overall mortality risk analogous to office SBP readings of 140 mmHg or higher or DBP readings of 90 mmHg or higher (grade C).

Health care professionals should ensure that patients who measure their BP at home have adequate training and, if necessary, repeat training in measuring their BP. Patients should be observed to determine whether they measure BP correctly and should be given adequate information about interpreting these readings (grade D).

The accuracy of all individual patients’ validated devices (including electronic devices) must be regularly checked against a device of known calibration (grade D).

Home BP values for assessing white coat hypertension or sustained hypertension should be based on duplicate measures, morning and evening, for an initial seven-day period. First-day home BP values should not be considered (grade D).

Background

Information on validated BP monitors can be found at the following Internet address: www.hypertension.ca/chep/approved-home-bp-devices. There are no changes to these recommendations for 2010.

VIII. Ambulatory BP measurement

Recommendations

Ambulatory BP readings can be used in the diagnosis of hypertension (grade C).

- ABPM should be considered when an office-induced increase in BP is suspected in treated patients with:

- BP that is not below target despite receiving appropriate chronic antihypertensive therapy (grade C);

- symptoms suggestive of hypotension (grade C); or

- fluctuating office BP readings (grade D).

Physicians should use only ABPM devices that have been validated independently using established protocols (grade D).

Therapy adjustment should be considered in patients with a 24 h ambulatory SBP of 130 mmHg or higher or DBP of 80 mmHg or higher, or an awake SBP of 135 mmHg or higher or DBP of 85 mmHg or higher (grade D).

The magnitude of changes in nocturnal BP should be taken into account in any decision to prescribe or withhold drug therapy based on ambulatory BP (grade C) because a decrease in nocturnal BP of less than 10% is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

Background

There are no changes to these recommendations for 2010.

IX. Role of echocardiography

Recommendations

Routine echocardiographic evaluation of all hypertensive patients is not recommended (grade D).

An echocardiogram for assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy is useful in selected cases to help define the future risk of cardiovascular events (grade C).

Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular mass as well as of systolic and diastolic left ventricular function is recommended for hypertensive patients suspected of having left ventricular dysfunction or coronary artery disease (grade D).

Patients with hypertension and evidence of heart failure should have an objective assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction, either by echocardiogram or nuclear imaging (grade D).

Background

There are no changes to these recommendations for 2010.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The CHEP Recommendations Task Force will continue to monitor the published literature and update these guidelines annually based on new developments and feedback from stakeholders and other users of these recommendations.

ONLINE TABLE 1.

Hyperaldosteronism: Screening and diagnosis

| i) Plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity (see ii below for conversion factors) should be measured under standardized conditions, including the collection of morning samples taken from patients in a sitting position after resting at least 15 min. Antihypertensive drugs may be continued, with the exception of aldosterone antagonists, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-adrenergic antagonists and clonidine. | ||

| ii) Renin, aldosterone and ratio conversion factors: | ||

| A. To estimate: | B. From: | Multiply (B) by: |

| Plasma renin concentration (ng/mL) | Plasma renin activity (ng/mL/h) | 0.206 |

| Plasma renin activity (g/L/s) | Plasma renin activity (ng/mL/h) | 0.278 |

| Plasma aldosterone concentration (pmol/L) | Plasma aldosterone concentration (ng/dL) | 28 |

| iii) Definition of a positive screening test: plasma aldosterone to renin activity ratio greater than 550 pmol/L/ng/mL/h (or 140 pmol/L/ng/L when renin is measured as renin mass or concentration). | ||

iv) Manoeuvres to demonstrate autonomous hypersecretion of aldosterone:

| ||

v) Differentiating potential causes of primary aldosteronism:

| ||

Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

ONLINE TABLE 2.

Pheochromocytoma: Screening and diagnosis

Biochemical screening tests for pheochromocytomas:

|

Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

Footnotes

SPONSORS: The CHEP process is sponsored by the Canadian Hypertension Society, Blood Pressure Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the College of Family Physicians of Canada, the Canadian Pharmacists Association, the Canadian Council of Cardiovascular Nurses, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Kramer H, et al. Hypertension treatment and control in five European countries, Canada, and the United States. Hypertension. 2004;43:10–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000103630.72812.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannel WB. Blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor: Prevention and treatment. JAMA. 1996;275:1571–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA, et al. The 2007 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23:529–38. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70797-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan NA, Hemmelgarn B, Padwal R, et al. The 2007 Canadian Hypertension Education Program Recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 2 – therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23:537–50. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70798-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, Khan NA, et al. The 2008 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:455–63. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70619-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan NA, Hemmelgarn B, Herman RJ, et al. The 2008 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 2 – therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:465–75. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan NA, Hemmelgarn B, Herman RJ, et al. The 2009 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 2 – therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:287–98. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70492-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, Khan NA, et al. The 2009 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:279–86. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70491-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarnke KB, Campbell NR, McAlister FA, Levine M. A novel process for updating recommendations for managing hypertension: Rationale and methods. Can J Cardiol. 2000;16:1094–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAlister FA. The Canadian Hypertension Education Program – a unique Canadian initiative. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:559–64. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70277-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beckett L, Godwin M. The BpTRU automatic blood pressure monitor compared to 24 hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the assessment of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-5-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Consistent relationship between automated office blood pressure recorded in different settings. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14:108–11. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e32832c5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell NR, Conradson HE, Kang J, Brant R, Anderson T. Automated assessment of blood pressure using BpTRU compared with assessments by a trained technician and a clinic nurse. Blood Press Monit. 2005;10:257–62. doi: 10.1097/01.mbp.0000173486.44648.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers MG, McInnis NH, Fodor GJ, Leenen FH. Comparison between an automated and manual sphygmomanometer in a population survey. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:280–3. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers MG. Automated blood pressure measurement in routine clinical practice. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:59–62. doi: 10.1097/01.mbp.0000200481.64787.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers MG, Godwin M. Automated measurement of blood pressure in routine clinical practice. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9:267–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.06512.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright JM, Mattu GS, Perry TL, Jr, et al. Validation of a new algorithm for the BPM-100 electronic oscillometric office blood pressure monitor. Blood Press Monit. 2001;6:161–5. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White WB, Anwar YA. Evaluation of the overall efficacy of the Omron office digital blood pressure HEM-907 monitor in adults. Blood Press Monit. 2001;6:107–10. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stergiou GS, Tzamouranis D, Protogerou A, Nasothimiou E, Kapralos C. Validation of the Microlife Watch BP office professional device for office blood pressure measurement according to the international protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13:299–303. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283057af6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27:280–6. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831b9e6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell NR, McKay DW, Conradson H, Lonn E, Title LM, Anderson T. Automated oscillometric blood pressure versus auscultatory blood pressure as a predictor of carotid intima-medial thickness in male firefighters. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21:588–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA, Myers MG, et al. The 2005 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21:645–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topol EJ, Lauer MS. The rudimentary phase of personalised medicine: Coronary risk scores. Lancet. 2003;362:1776–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA, Grover S, et al. The 2006 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:573–81. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70279-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grover SA, Hemmelgarn B, Joseph K, Milot A, Tremblay G. The role of global risk assessment in hypertension therapy. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:606–13. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson KM, Wilson PW, Kannel WB. An updated coronary risk profile. A statement for health professionals. Circulation. 1991;83:356. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1414–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Grundy S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: Results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286:180–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Agostino RB, Russell MW, Huse DM, et al. Primary and subsequent coronary risk appraisal: New results from the Framingham study. Am Heart J. 2000;139:272–81. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.96469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grover SA, Paquet S, Levinton C, et al. Estimating the benefits of modifying risk factors of cardiovascular disease: A comparison of primary vs secondary prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:655–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: The SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration. Fowkes FG, Murray GD, et al. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham risk score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:197–208. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cooney MT, Dudina AL, Graham IM. Value and limitations of existing scores for the assessment of cardiovascular risk: A review for clinicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1209–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grover SA, Lowensteyn I, Joseph L, et al. Patient knowledge of coronary risk profile improves the effectiveness of dyslipidemia therapy: The CHECK-UP study: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2296–303. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benner JS, Erhardt L, Flammer M, et al. A novel programme to evaluate and communicate 10-year risk of CHD reduces predicted risk and improves patients’ modifiable risk factor profile. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1484–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ONLINE TABLE 1.

Hyperaldosteronism: Screening and diagnosis

| i) Plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity (see ii below for conversion factors) should be measured under standardized conditions, including the collection of morning samples taken from patients in a sitting position after resting at least 15 min. Antihypertensive drugs may be continued, with the exception of aldosterone antagonists, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-adrenergic antagonists and clonidine. | ||

| ii) Renin, aldosterone and ratio conversion factors: | ||

| A. To estimate: | B. From: | Multiply (B) by: |

| Plasma renin concentration (ng/mL) | Plasma renin activity (ng/mL/h) | 0.206 |

| Plasma renin activity (g/L/s) | Plasma renin activity (ng/mL/h) | 0.278 |

| Plasma aldosterone concentration (pmol/L) | Plasma aldosterone concentration (ng/dL) | 28 |

| iii) Definition of a positive screening test: plasma aldosterone to renin activity ratio greater than 550 pmol/L/ng/mL/h (or 140 pmol/L/ng/L when renin is measured as renin mass or concentration). | ||

iv) Manoeuvres to demonstrate autonomous hypersecretion of aldosterone:

| ||

v) Differentiating potential causes of primary aldosteronism:

| ||

Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program

ONLINE TABLE 2.

Pheochromocytoma: Screening and diagnosis

Biochemical screening tests for pheochromocytomas:

|

Reprinted with permission from the Canadian Hypertension Education Program