Abstract

Circulating endothelial cells (CECs) are nonhematopoetic mononuclear cells in peripheral blood that are dislodged from injured vessels during cardiovascular disease, systemic vascular disease, and inflammation. Their occurrence during cerebrovascular insults has not been previously described. Epileptic seizures cause the long-term loss of cerebrovascular endothelial dilator function. We hypothesized that seizures cause endothelial sloughing from cerebral vessels and the appearance of brain-derived CECs (BCECs), possible early indicators of cerebral vascular damage. Epileptic seizures were induced by bicuculline in newborn pigs; venous blood was then sampled during a 4-h period. CECs were identified in the fraction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells by the expression of endothelial antigens (CD146, CD31, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase) and by Ulex europeaus lectin binding. In control animals, few CECs were detected. Seizures caused a time-dependent increase in CECs 2–4 h after seizure onset. Seizure-induced CECs coexpress glucose transporter-1, a blood-brain barrier-specific glucose transporter, indicating that these cells originate in the brain vasculature and are thus BCECs. Seizure-induced BCECs cultured in EC media exhibited low proliferative potential and abnormal cell contacts. BCEC appearance during seizures was blocked by a CO-releasing molecule (CORM-A1) or cobalt protoporphyrin (heme oxygenase-1 inducer), which prevented apoptosis in cerebral arterioles and the loss of cerebral vascular endothelial function during the late postictal period. These findings suggest that seizure-induced BCECs are injured ECs dislodged from cerebral microvessels during seizures. The correlation between the appearance of BCECs in peripheral blood, apoptosis in cerebral vessels, and the loss of postictal cerebral vascular function suggests that BCECs are early indicators of late cerebral vascular damage.

Keywords: cerebral vascular endothelium, cerebral vascular injury, postictal period, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, carbon monoxide-releasing molecule, CORM-A1

circulating endothelial cells (CECs) are nonhemopoietic mononuclear cells (MNCs) in the peripheral blood that are identified by the expression of endothelium-specific markers. These cells are thought to originate from sloughing off the vessel walls after a vascular insult (6, 8, 20, 32). Their number in healthy adults is very low but is greatly increased in numerous conditions associated with endothelial dysfunction in the systemic circulation. Elevated numbers of CECs have been reported in cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis (33), coronary syndrome (30, 41), vasculitis (25), Kawasaki disease (44), septic shock (42), sickle cell anemia (59), and diabetes (1, 36). Since the number of CECs was found to correlate with other indicators of vascular damage in cardiovascular disorders (30, 33), the measurement of CECs in peripheral blood has been suggested as a potential new noninvasive method for assessing vascular damage.

To date, the possibility of occurrence of CECs of brain origin [brain-derived CECs (BCECs)] as a result of cerebrovascular disease has not been addressed. Furthermore, there are no reports on CECs occurrence in neonates. Cerebrovascular insult during epileptic seizures in newborn pigs causes a sustained loss of endothelial dilator function in the cerebral vasculature (49). However, CECs have not been investigated as potential peripheral blood markers of cerebrovascular damage.

Carbon monoxide (CO) is produced with bilirubin/biliverdin through the enzymatic degradation of heme by heme oxygenase (HO), the enzyme essential for normal cerebrovascular endothelial function (51, 52). We have recently reported that CORM-A1, a water-soluble CO-releasing molecule that slowly releases CO in neutral and acidified solutions (40), delivers CO to the brain and exerts the biological action of the gas in the newborn cerebral circulation (66). CO, either produced endogenously by pharmacologically induced HO-1 activity, the inducible isoform of HO, or liberated from systemically administered CORM-A1, is protective against seizure-induced sustained cerebrovascular dysfunction in vivo (49, 51, 66) as well as glutamate- or TNF-α-triggered apoptosis in cultured cerebral microvascular ECs (CMVECs) (4, 5, 48).

We hypothesized that seizures cause endothelial sloughing from cerebral vessels and the appearance of BCECs, which might be novel biomarkers in the early detection of cerebral vascular damage. Therefore, the aims of the present study in the newborn piglet model of epileptic seizures were as follows: 1) characterize seizure-induced CECs and examine their possible brain origin and 2) establish the relationship between BCECs, cerebral vascular damage, and the long-term loss of cerebrovascular function.

METHODS

All protocols and procedures that involved animals were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (Memphis, TN).

Experimental models of neonatal epileptic seizures.

Seizures were induced with bicuculline (3 mg/kg) in ventilated newborn pigs (1–5 days old, 1.5–2.5 kg, either sex). Pigs were anesthetized with ketamine-acepromazine as we have previously described (49, 50, 53, 66). The use of bicuculline-induced seizures in newborn pigs is an appropriate model to study the effects of neonatal seizures that generally occur upon restriction of GABA-mediated inhibition of glutamatergic neurotransmission (11, 37, 54, 61). Enhancers of GABA inhibition (barbiturates and benzodiazepines) are antiepileptic drugs that are widely used for the treatment of seizures in human babies (14, 15). Similarly to epileptic neonates (11), bicuculline-induced seizures in ketamine-acepromazine-anesthetized piglets are characterized by a sudden onset of repetitive neuronal synchronous neuronal discharges, robust elevation in EEG amplitude, and spectral power of the EEG signals in the alpha-band (8–13 Hz), beta-band (>13 Hz), delta-band (<4 Hz), and theta-band (4–8 Hz) of over 2-h duration (50). Ketamine-acepromazine is also our preferred choice of anesthesia for survival seizure experiments because it is very rapid in onset but is short acting (49, 66). Importantly, recovery of ketamine-acepromazine-anesthetized piglets from seizures is uneventful and complication free. Animals were paralyzed with pancuronium bromide (0.2 mg/kg iv). Pancuronium attenuates the increase in mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) during seizures without affecting the cerebral blood flow response (53). Additional injections of pancuronium (0.1 ml/kg) were given if visible evidence of seizures was seen.

In the first group of experiments, which was designed to detect the acute effects of seizures on CECs, animals ventilated with room air were equipped with catheters in a femoral artery for the measurement of systemic parameters and in a femoral vein for the administration of 6% Gentran solution (0.4 ml·kg−1·h−1) and for blood collection. Venous blood was sampled before and 0.5–4.0 h after bicuculline administration. We also used kainic acid-induced seizures (58, 60) as another model to test the effects of cerebrovascular stress on the appearance of CECs. Kainic acid (20 mg/kg iv) was administered to anesthetized and air-ventilated newborn pigs, systemic parameters and the pial arteriolar diameter were monitored, and venous blood was sampled for the detection of CECs 0–4 h after seizure induction, as described above. Similar to bicuculline-induced seizures, kainic acid-induced seizures caused a sustained (>2 h) increase in cerebral blood flow, as reflected by the 70–90% dilation of pial arterioles.

The second group of experiments was designed to assess the long-term cerebrovascular outcome of bicuculline-induced seizures. All surgical procedures were minimally invasive. Anesthetized pigs were intubated through the mouth and ventilated with a supraphysiological minute volume with a gas mixture of 4% CO2-21% O2-75% N2 to maintain physiological levels of blood gases (49). A butterfly needle was inserted into the ear vein for the administration of pancuronium bromide (0.2 mg/kg iv), and bicuculline (3 mg/kg ip) was injected through a 0.22-μm Millipore filter. Animals were kept on the ventilator for 2 or 3 h until seizure activity subsided. When fully conscious, piglets were transferred to the animal care facility and kept in warmed cages with food and drink ad libitum. Postictal cerebral vascular reactivity was determined 2 days after seizures by a cranial window technique.

Experimental groups.

Three groups of experimental animals were used to test the relationships between CECs in peripheral blood, cerebral vascular damage, and the late loss of cerebrovascular function in a model of bicuculline-induced seizures: control piglets (group I), CORM-A1-pretreated piglets [2 mg/kg ip, 30 min before seizures (66); group II], and piglets pretreated with cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPP; 20 mg/kg ip, 24 h before seizures; group III) to upregulate brain HO-1 (49). All solutions were applied aseptically.

Cranial windows for intravital microscopy of cerebral pial arterioles.

To test long-term postictal cerebral vascular function, cranial windows were installed in anesthetized and ventilated piglets 2 days after seizures as previously described in detail (31, 49, 65). The space under the window was filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid, which contained (in mM) 3.0 KCl, 1.5 MgC2, 1.5 CaCl2, 132 NaCl, 6.6 urea, 3.7 dextrose, and 24.6 NaHCO3 and was equilibrated with 5% CO2-6% O2-89% N2 to pH 7.4–7.5 (Pco2: 32–36 mmHg and Po2: 40–45 mmHg) at 37°C. Pial arteriolar diameter was measured with a videomicrometer coupled to a television camera. We tested the postictal cerebrovascular dilation response to bradykinin (10−6 M), an endothelium-dependent vasodilator (49, 65).

Detection of apoptosis in cerebral pial arterioles by TUNEL staining.

Pial arterioles (100–200 μm, 3–5 arterioles/piglet) were excised from the cerebral cortex surface before seizures (group I) or 4 h after seizure induction (groups I–III) and cleaned of adherent tissues. Pial arterioles were air dried on microscopic slides, fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde (20 min), and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% citrate buffer for 7 min. DNA degradation, a hallmark of apoptosis, was detected by TUNEL using an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Cerebral arterioles were stained with the fluoresceine-based enzyme TUNEL mixture for 1 h at room temperature according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mounted slides were viewed by a Nikon Diaphot fluorescence microscope and processed using IPLab Spectrum software and Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems).

Isolation of peripheral blood MNCs.

Venous blood samples (3 ml) were collected in K3-EDTA-containing Vacutainer tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) before the induction of seizures and 30 min and 1, 2, 3, and 4 h afterward; samples were processed within 2 h. The fraction of MNCs was separated by Histopaque 1077 density gradient centrifugation (59) with some modifications. Whole venous blood was diluted 1:2 with Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS), layered on an equal volume of Histopaque 1077, and centrifuged for 30 min at 350 g at room temperature. MNCs remained at the interface, whereas erythrocytes and granulocytes were pelleted. The interface layer was collected by aspiration, rediluted 1:5 with DPBS, and pelleted for 10 min at 1,200 g. MNCs were washed three times in DPBS, resuspended in 40 μl DPBS, and transferred to microscopic slides for smears (10 μl/slide in triplicate). Smears were air dried overnight and fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in DPBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min for immunostaining. Slides were stored in 0.1% sodium azide-PBS at 4°C for up to 3 wk.

Immunomagnetic isolation of CD31+ cells from the MNC fraction.

CD31 (PECAM-1) is an endothelial surface antigen expressed by CECs. Isolated MNCs (106 cells/ml) were incubated with 25 μm Dynabeads CD31 (4.5 μm, Dynal Biotech) in DPBS-0.1% BSA for 20 min at 4°C with gentle rotation. Positive isolation of bead-bound CD31+ cells was performed using a magnetic particle concentrator (Dynal MPC-L, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were recovered after several washes in DPBS and used for microscopy analysis.

CEC outgrowth in culture.

MNCs isolated immediately after blood collection were plated on Matrigel-covered 12-well culture plates (106 cells/well) in EC-supporting medium DMEM(E), which was composed of DMEM with 20% FBS, 30 μg/ml EC growth supplement, 1 U/ml heparin, and an antibiotic-antimicotic mixture (48). The medium was changed the next day to remove unattached cells, and cells were cultured in a 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere for 2–4 wk. Media were changed twice a week. When significant outgrowth was observed, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in DPBS (pH 7.4) for 20 min and processed for immunofluorescence staining.

Cultures of CMVECs and aortic ECs from newborn pigs.

To isolate CMVECs, cerebral microvessels (60–300 μm) were treated with collagenase-dispase (2 mg/ml in DMEM for 2 h at 37°C), and detached CMVECs were separated on a Percoll density gradient as previously described (48). To isolate aortic ECs (AECs), the aorta, cut open longitudinally, was treated with collagenase-dispase (2 mg/ml in DMEM for 1 h at 37°C). Dissociated AECs were collected from the media by a 26-gauge needle syringe and pelleted. Isolated CMVECs and AECs were plated on Matrigel-coated 12-well plates (2 × 104 cells/well) and cultured in DMEM(E) for 4–5 days until confluence. CMVECs and AECs were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde in DPBS (pH 7.4) for 20 min and processed for immunofluorescence staining.

Immunofluorescence staining of CMVECs, AECs, and CECs.

Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in DPBS (20 min at room temperature). Nonspecific sites were blocked by 5% BSA-DPBS (1 h at room temperature). Cells were immunostained for endothelial antigens, CD146 (MEL-CAM), CD31 (PECAM-1), endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), constitutive HO (HO-2), and Ulex europeaus lectin 1 (UEA-1). To identify the brain origin of CMVECs and CECs, we immunodetected the brain-specific isoform of glucose transporter type 1 (GLUT1). For single-antigen staining, cells were incubated with the primary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C. For double-antigen staining, cells were incubated with the monoclonal primary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C followed by an incubation with polyclonal primary antibodies for 1 h at 37°C. Immunocomplexes were visualized with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and Alexa red-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1 h at 37°C). After three washes in DPBS, slides were rinsed in distilled water, air dried, and mounted with antifade mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for the fluorescent counterstaining of nuclei. Slides were viewed with the Nikon Diaphot deconvolution microscope. Images were collected and processed using the IPLab Spectrum software and Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems).

Statistical analysis.

Values are presented as means ± SE of absolute values or as percentages of the control. Data were analyzed by ANOVA for repeated measurements followed by Fisher's protected least-significant-difference test to isolate differences between groups. P values of <0.05 were considered significant in all statistical tests.

Materials.

CORM-A1 was a generous gift from Hector Knight (Tyco-Mallinckrodt Medical, Petten, Holland). Pancuronium bromide was from Astra Pharmaceutical Products (Westborough, MA). Bicuculline and bradykinin were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cell culture reagents were purchased from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD), Hyclone (South Logan, UT), and Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). Matrigel was from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA). Antibodies were purchased from the following sources: anti-CD146 from Upstate Millipore (Lake Placid, NY), anti-CD31 from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA), anti-eNOS from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), anti-UEA-1 from Sigma, anti-GLUT1 from Chemicon Millipore (Temecula CA), and anti-HO-2 from Stressgen (Victoria, BC, Canada). Fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies and mounting medium were from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA).

RESULTS

Effects of seizures on the cerebral and systemic circulations.

Bicuculline (3 mg/kg iv) causes immediate synchronous epileptiform discharges sustained for a 2-h period accompanied by the concomitant dilation of pial arterioles and increased cerebral blood flow to match the metabolic demands of activated neurons (49, 50). Seizures also cause an immediate and sustained increase in heart rate [from ∼120 to ∼200 beats/min (49)] and a moderate increase in MABP (from 70–80 to 95–100 mmHg; Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of bicuculline-induced seizures on mean arterial blood pressure in control, CORM-A1-pretreated, and CoPP-pretreated newborn piglets

| Control | CORM-A1 (2 mg/kg) Pretreatment | CoPP (20 mg/kg) Pretreatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 29 | 9 | 6 |

| Baseline | 75 ± 5 | 78 ± 5 | 68 ± 4 |

| Bicuculline, 10 min | 96 ± 3* | 99 ± 5* | 102 ± 7* |

| Bicuculline, 60 min | 86 ± 2 | 86 ± 4 | 90 ± 4 |

Values are means ± SE (in mmHg); n, no. of piglets/group. CORM-A1, carbon monoxide-releasing molecule; CoPP, cobalt protoporphyrin.

P < 0.05 compared with baseline values. There are no differences among control, CORM-A1-, and CoPP-pretreated piglets at any time point.

Seizures increase the number of CD146+ cells in peripheral blood.

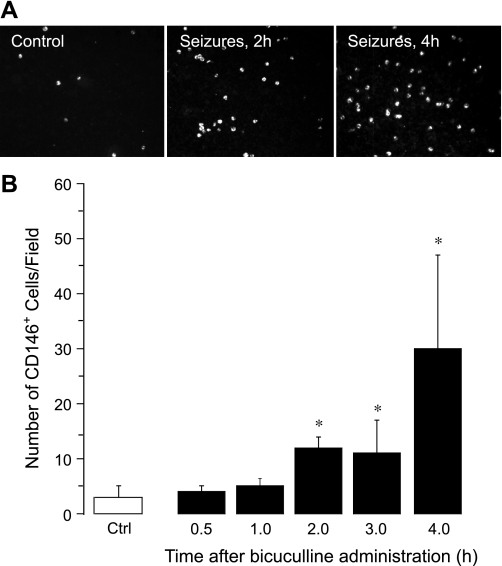

CD146, a glycoprotein involved in endothelial cell-cell contacts, is a commonly used marker for CECs (1, 3, 19, 25, 30, 33, 36, 41, 42, 44, 59). Therefore, we identified CECs in the fraction of MNCs as CD146+ cells (Fig. 1, A and B). In control animals, few CD146+ cells were detectable (3 ± 2 cells/microscopic field, n = 7 animals). Bicuculline-induced seizures caused a time-dependent increase in CECs (Fig. 1, A and B). After an initial lag period (0.5–1.0 h), the number of CECs increased 5- to 10-fold above the baseline 2–4 h after the seizure onset (30 ± 17 cells/microscopic field, P < 0.05, n = 7 animals). We also observed a time-dependent five- to sixfold increase in peripheral blood CD146+ cells in a model of kainic acid-induced seizures that occurred 2 and 4 h after the administration of kainic acid (Fig. 2). These findings indicate that prolonged seizures cause the acute appearance of CECs in peripheral blood.

Fig. 1.

Time-dependent effects of bicuculline-induced seizures on the appearance of CD146+ cells in peripheral blood (n = 7 piglets). A: representative images (×20 objective). B: numbers of CD146+ cells/microscopic field. *P < 0.05 compared with baseline control values.

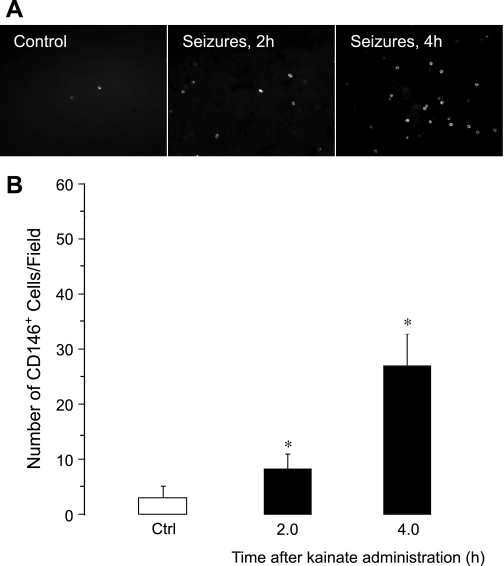

Fig. 2.

Time-dependent effects of kainic acid-induced seizures on the appearance of CD146+ cells in peripheral blood (n = 2 piglets). A: representative images (×20 objective). B: numbers of CD146+ cells/microscopic field. *P < 0.05 compared with baseline control values.

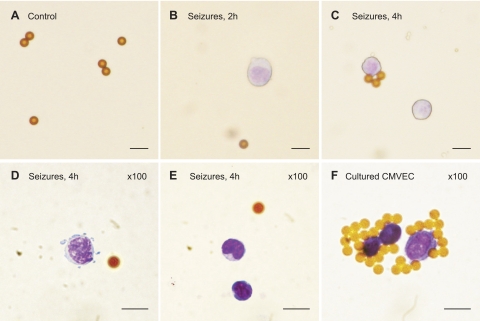

In a second approach, we identified seizure-induced CECs by another endothelium-specific antigen, CD31 [PECAM-1 (12)] using an immunomagnetic separation of MNCs on pan mouse IgG-coated superparamagnetic polystyrene beads (4.5-μm Dynabeads CD31; Fig. 3, A–F). Control MNCs contained no CD31+ cells (Fig. 3A), whereas the appearance of CD31+ cells was observed in blood collected 2 and 4 h after seizure onset (Fig. 3, B–E). Positive control isolation of CD31+ cells was performed with cultured CMVECs from newborn pigs (Fig. 3F). CECs identified as CD31+ cells were round cells of ∼12–15 μm in diameter, the size of CMVECs.

Fig. 3.

Immunomagnetic isolation of seizure-induced circulating endothelial cells (CECs) on Dynabeads CD31. Mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood collected before seizures (A), 2 h after seizure induction (B), and 4 h after seizure induction by bicuculline (C–E). Shown are representative images of CD31+ cells retained by Dynabeads CD31 (A–C: ×20 objective, D and E: ×100 objective). F: positive control, cultured newborn piglet cerebral microvascular ECs (CMVECs). Bars = 10 μm.

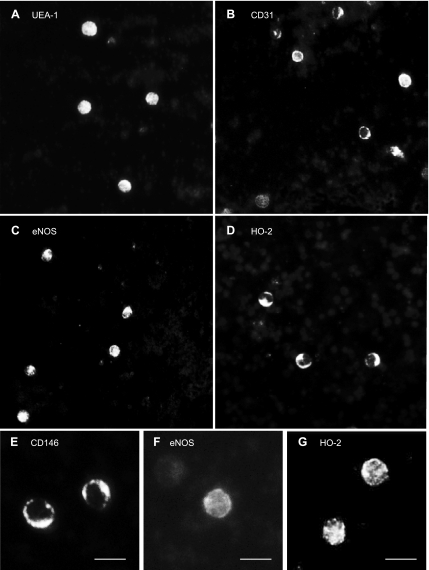

Immunological characterization of seizure-induced CECs.

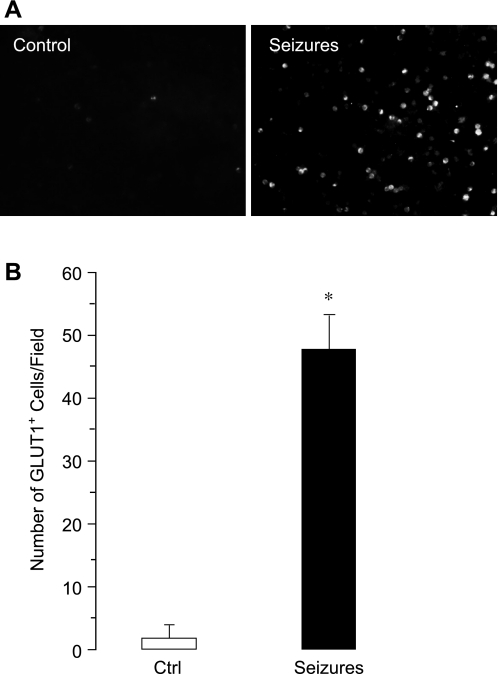

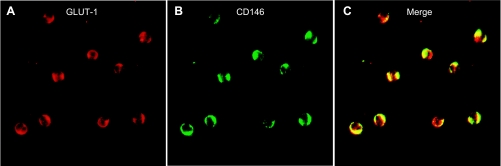

To immunophenotype the seizure-induced CECs, we sought to detect additional endothelium-specific markers: UEA-1, CD31, and eNOS. We found numerous UEA1+, CD31+, and eNOS+ cells (Fig. 4) 4 h after seizure onset, further indicating the presence of seizure-induced CECs in peripheral blood. Control MNCs did not express any of these antigens (data not shown). To provide evidence of the vascular origin of seizure-induced CECs, we immunodetected HO-2, a constitutive protein highly expressed in cerebral vascular ECs (48, 52), and GLUT1, a blood-brain barrier-specific isoform of GLUT (2, 13, 29, 47, 62). Both HO-2+ and GLUT1+ cells were immunodetected in blood 4 h after seizure induction (Figs. 4, D and G, 5, and 6A) but not in control samples. Quantitative immunodetection of the blood-brain barrier antigen demonstrated that seizures greatly increase the number of GLUT1+ cells in peripheral blood (n = 4 piglets; Fig. 5). Most importantly, GLUT1 colocalized with CD146 (Fig. 6, A–C), suggesting that seizure-induced CECs represent BCECs (CD146+/GLUT1+ cells) that originate from cerebral vessels.

Fig. 4.

Immunophenotyping of seizure-induced CECs. CECs in blood withdrawn 4 h after the onset of seizures were detected by the expression of endothelial antigens. A: Ulex europeaus lectin 1 (UEA-1); B: CD31; C and F: endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS); E: CD146; D and G: constitutive heme oxygenase (HO)-2. A–D: ×20 objective; E–G: ×40 objective. Bars = 20 μm.

Fig. 5.

Effects of bicuculline-induced seizures on the appearance of glucose transporter (GLUT)1+ cells in peripheral blood (n = 3 piglets). A: representative images (×20 objective). B: numbers of GLUT1+ cells/microscopic field. *P < 0.05 compared with baseline control (Ctrl) values.

Fig. 6.

Cerebral vascular origin of seizure-induced CECs. Brain-derived CECs (BCECs) in blood withdrawn 4 h after the onset of seizures were detected by coexpression of blood-brain barrier-specific GLUT1 (A) and CD146, an endothelial antigen (B). C: merged images of CD146+/ GLUT1+ cells.

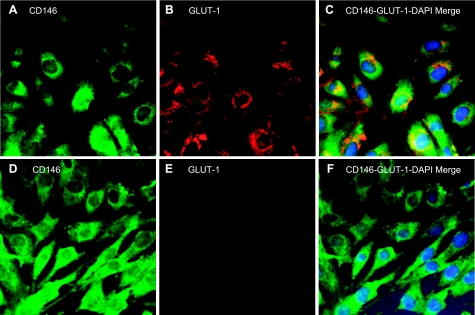

Immunophenotyping of ECs from cerebral microvessels of newborn pigs.

To verify the brain origin of seizure-induced CECs, we conducted phenotyping of ECs from cerebral microvessels (CMVECs) and from aortae (AECs) of newborn pigs. CMVECs coexpressed CD146 (an endothelial antigen) and GLUT1 (a blood-brain barrier antigen; Fig. 7, A–C). In contrast, AECs expressed CD146 but not GLUT1 (Fig. 7, D and E), indicating the specificity of GLUT1 as the marker of brain-derived ECs. These data clearly demonstrate that selected endothelium- and brain-specific antigens are coexpressed in brain-derived ECs (CD146+/GLUT1+) but not in peripheral vascular ECs (CD146+/GLUT1−) and can be used to verify the brain origin of seizure-induced CECs.

Fig. 7.

Immunophenotyping of cultured ECs from newborn pig cerebral vessels (A–C) and from the aorta (D–F) for CD146, an endothelial antigen (A and D), and GLUT1, the blood-brain barrier-specific GLUT (B and E). Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). C and F: merged images for CD146, GLUT1, and DAPI.

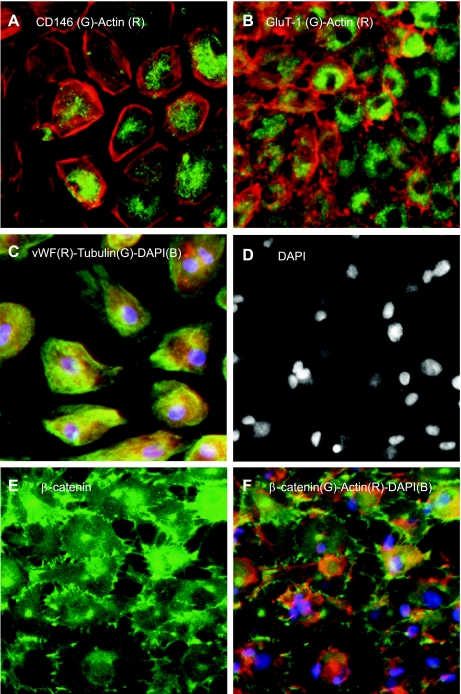

Proliferative capacity of BCECs.

The BCEC-enriched fraction of MNCs isolated 4 h after seizure induction was seeded on Matrigel-coated 12-well plates (106 cells/well) and cultured in EC growth media for 3–4 wk (n = 20 independent cultures). MNCs isolated 4 h after seizure induction showed numerous apoptotic cells, as detected by TUNEL staining (not shown). Cell growth was observed in only five cases (25%). Outgrowth cells have an endothelial phenotype as detected by the expression of endothelial markers, CD146, von Willebrand factor, and blood-brain barrier-specific GLUT1 (Fig. 8, A–C), confirming the brain origin of seizure-induced CECs. Outgrowth ECs, however, have a dramatically changed morphology and an impaired actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 8, A–C and F). Furthermore, β-catenin staining revealed the failure of outgrowth CECs to form cell contacts (Fig. 8, E and F). Many outgrowth cells have condensed and disintegrated apoptotic nuclei (Fig. 8D). Overall, seizure-induced BCECs are largely irreversibly damaged cells that are characterized by the inability to form cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts, low proliferative capacity, dramatic changes in the cell shapes, and condensed fragmented nuclei indicative of advanced apoptosis.

Fig. 8.

Outgrowths of seizure-induced BCECs. BCEC-enriched mononuclear cells from blood sampled 4 h after seizure induction were cultured in EC media for 3–4 wk. Outgrowth ECs were identified by endothelial antigens CD146 (A), von Willebrand factor (vWF; C), and blood-brain barrier-specific GLUT1 (B). Cell contacts were identified by β-catenin (E and F). The cytoskeleton was visualized with actin (A, B, and F) and tubulin (C). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (C–F). G, green; R, red; B, blue.

Seizure-induced apoptosis in pial arterioles.

We sought to determine whether seizures damage cerebral vessels and cause apoptosis-related endothelial sloughing. DNA fragmentation is a key event of advanced apoptosis. We examined the acute effects of seizures on DNA fragmentation in the cerebral vasculature by TUNEL assay. Pial cerebral arterioles (100–200 μm) from control and ictal piglets (3–5 arterioles/animal, n = 2 animals/group) were dissected from the brain surface and processed for TUNEL fluorescence staining. In control piglets, few TUNEL-positive cells were detectable (Fig. 9A), whereas 4 h after seizure onset, numerous TUNEL-positive cells were observed in cerebral vessels (Fig. 9B). These data indicate that seizures cause acute damage to cerebral vessels by initiating apoptosis.

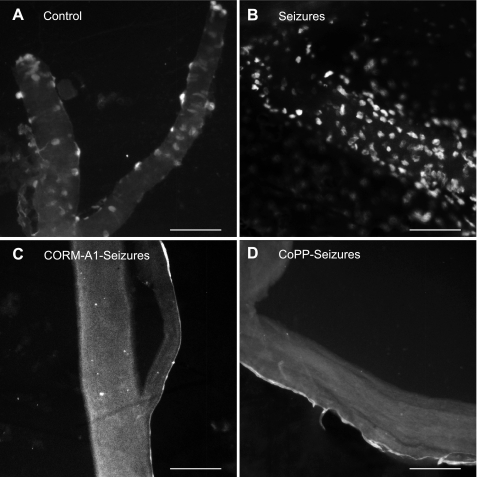

Fig. 9.

Detection of apoptosis by TUNEL staining of pial cerebral vessels from control piglets (no seizures; A) and 4 h after the induction of seizures in saline-treated piglets (B), carbon monoxide (CO)-releasing molecule (CORM-A1)-treated piglets (C), and HO-1-induced [cobalt protoporphyrin (CoPP)] piglets (D). Bars = 100 μm.

HO/CO-modulated animal model to test the correlation between seizure-induced BCECs, damage of cerebral arterioles, and postictal cerebral vascular dysfunction.

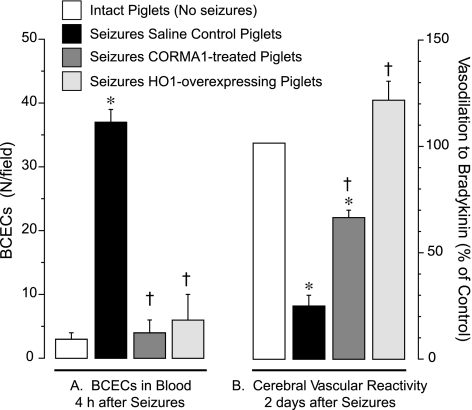

For the quantification of seizure-induced endothelial damage, we used a functional approach based on the detection of endothelium-mediated dilation of cerebral vessels. Previously, we (49, 66) demonstrated that seizures cause a sustained loss of cerebral endothelial vasodilator function during the late postictal period. The endogenous HO/CO system is critical for the cytoprotection of the cerebral vasculature from seizure-related cerebrovascular stress. We found that the loss of postictal cerebrovascular function could be ameliorated in animals treated with exogenous CO (66) or with a HO-1 inducer, CoPP (49), to boost endogenous CO production. Therefore, we experimentally manipulated the HO/CO system to investigate the functional relationships between the early appearance of BCECs, apoptosis in cerebral vessels, and late loss of postictal endothelial dilator function. To this end, seizures were induced by bicuculline in three groups of pigs pretreated with 1) saline control, 2) the CO-releasing molecule CORM-A1 (2 mg/kg ip, 30 min before seizures), and 3) CoPP (20 mg/kg ip, 24 h before seizures). In saline control piglets, seizures caused the appearance of BCECs (Fig. 10A), increased the number of apoptotic cells in cerebral arterioles (Fig. 9B), and caused >70% loss of postictal cerebral vascular endothelial function (Fig. 10B). In contrast, in piglets pretreated with CoPP or CORM-A1, the appearance of BCECs, apoptosis of pial arterioles, and late loss of postictal cerebral vascular endothelial function were greatly reduced or completely prevented (Figs. 9, C and D, and 10, A and B). We found no differences between MABP values in the different experimental groups (Table 1), so the contribution of hemodynamic factors to changes in BCECs is unlikely. These data indicate that the seizure-induced early appearance of BCECs correlates with the early onset of apoptosis in cerebral resistance arterioles (4 h) and with the subsequent late loss of cerebral vascular endothelial dilator function seen during the extended postictal period (2 days).

Fig. 10.

Correlation between the early increase in BCECs and late loss of postictal cerebral vascular endothelial function. Seizures were induced in saline control piglets (n = 7) and in piglets pretreated with CORM-A1 (2 mg/kg ip, 30 min before seizures, n = 5) or with the HO-1 inducer CoPP (20 mg/kg ip, 24 h before seizures, n = 2). A: seizure-induced BCECs were immunodetected as CD146+/GLUT1+ mononuclear cells in blood collected during baseline measurements and 4 h after seizure onset. B: endothelium-dependent cerebral vascular reactivity to bradykinin (10−6 M) tested in control intact piglets (no seizures) and 2 days after seizures. *P < 0.05 compared with intact control values; †P < 0.05 compared with seizure saline control values.

DISCUSSION

The major novel findings of our study are as follows: 1) epileptic seizures in newborn piglets result in the early appearance of CECs in the peripheral blood, as identified by endothelial antigens (CD146, CD31, and eNOS); 2) seizure-induced CECs express a blood-brain barrier-specific antigen, GLUT1, indicating their brain origin; these cells are therefore referred to as BCECs; 3) seizure-induced BCECs express HO-2, an antigen relatively specific for brain-derived ECs; 4) seizures cause apoptosis in pial cerebral vessels; 5) the appearance of BCECs coincides with the advanced apoptosis in cerebral vessels and precedes the subsequent loss of cerebral vascular function caused by seizures; and 6) apoptosis in cerebral vessels and the appearance of BCECs are prevented by cerebroprotective interventions that prevent the seizure-induced loss of cerebrovascular function (HO-1 induction or CO delivery). Overall, these data indicate that BCECs appear to predict the late loss of cerebral vascular function caused by epileptic seizures.

Seizures occur when there is an abnormal synchronized activation of neurons concomitantly with extensive glutamate release (37, 54). Seizures lasting >10–30 min are defined as status epilepticus (61, 63). In newborn babies, status epilepticus that may persist for hours and even days accounts for ∼30% of neonatal seizures (11, 14, 34, 39, 45, 56, 57, 61). In human neonates, status epilepticus causes neuronal damage and long-lasting debilitating effects on brain development and function (26, 35, 38, 63, 64). The threshold duration of sustained seizures to produce cell death is ∼30 min (38). Little is known, however, about the cerebrovascular consequences of seizures. According to ultrastructural studies (7, 16, 17, 46), seizures are associated with disruption of the blood-brain barrier in animal models and patients. Clinical symptoms that often appear after seizures (the postictal period) suggest long-term neuronal and cerebrovascular dysfunction (21). A previous study (49) from our laboratory provided experimental evidence that epileptic seizures cause a sustained loss in the responsiveness of resistance cerebral arterioles during the late postictal period, with endothelium-dependent functions being most profoundly affected. The regulation of cerebral blood flow is critical for the maintenance of neuronal function. Therefore, it is important to diagnose and treat cerebrovascular damage to improve the overall long-term outcome of seizures.

It has been recently demonstrated that during systemic vascular disease, endothelial injury may result in sloughing ECs from the vasculature and their appearance in the blood as CECs. The appearance of CECs in peripheral blood correlates with the extent of the damage to systemic vessels that occurs in coronary artery disease (20, 23, 30, 33, 41, 43), diabetes (1, 36), Kawasaki disease (44), and sickle cell anemia (59). CECs are characterized by the expression of mature endothelial antigens, including CD146 and CD31 (1, 3, 6, 8, 19, 30, 43). The increased number of CECs in various systemic vascular disorders correlates with endothelial damage (30, 33), suggesting that CECs are novel markers of endothelial injury. No attempt has been undertaken, however, to detect CECs during cerebrovascular disease.

We, for the first time, have detected correlations between BCECs, damage of the brain vasculature, and the later loss of cerebral vascular function in a model of cerebrovascular disease caused by epileptic seizures. Epileptic seizures in newborn piglets cause loss of endothelium-dependent cerebrovascular functions during the late postictal period, 2 days after seizures (49, 66). Therefore, we sought to detect whether seizures cause the appearance of CECs, which may correlate with damage in the cerebral vasculature. We demonstrated that seizures cause the appearance in peripheral blood of CD146+ and CD31+ cells that express another endothelial antigen, eNOS, and bind UEA-1. We observed the appearance of CECs in both bicuculline- and kainic acid-induced models of sustained seizures. We provided evidence that seizure-induced CECs originate from the cerebral vascular bed, because they coexpress GLUT1, a blood-brain barrier-specific GLUT. Isoforms of GLUTs are expressed in a highly controlled tissue-specific fashion. GLUT1 is a blood-brain barrier-specific transporter isoform, as evidenced by numerous reports (2, 13, 29, 47, 62). Most importantly, we provide our own data confirming the specificity of GLUT1 expression in CMVECs but not in AECs isolated from newborn piglets. Overall, these data confirm that GLUT1 is the specific marker for the brain endothelium in newborn pigs. Seizure-induced CECs also express HO-2, a constitutive cytoprotective enzyme in the cerebral vascular endothelium (51, 52). The expression pattern of endothelial and blood-brain barrier antigens in CECs is identical to that of ECs from cerebral microvessels (CMVECs). Overall, seizure-induced CECs are identified as BCECs because they coexpress both endothelium- and blood-brain barrier-specific markers.

Because there are no previous data on BCECs at baseline, in disease models, or in patients, we compared our observations with CECs detected in cardiovascular diseases. In animal models and patients with systemic cardiovascular diseases, a 3- to 20-fold increase in CECs has been reported, including 1) a 10-fold increase in CECs during the hyperglycemic stress in diabetic rats (1); 2) a 3- to 5-fold increase in CECs in patients with coronary disease and acute cerebral infarction (23, 30, 33); 3) a ≤10-fold increase in CECs after coronary angioplasty (6, 8); 4) a 10- to 20-fold increase in CECs in patients with systemic inflammatory vasculitis and systemic sclerosis (6, 8, 20); and 5) a 5- to 10-fold increase in CECs in patients with septic shock (42). Furthermore, patients with progressive cancer had, on average, three- to fourfold more CECs than healthy subjects (19). Overall, a 10-fold increase in BCECs during seizures is of the same magnitude as reported for CECs in animal vascular disease models and patients with cardiovascular disease.

What is the mechanism underlying the appearance of BCECs? Elevation of cerebral blood flow occurs during seizures to match the metabolic demands of the brain. In a model of bicuculline-induced seizures in neonatal piglets, the maximal increase in cerebral blood flow occured within the first 30 min of seizures (12, 53). Ictal hyperemia and a transient rise in blood pressure might increase shear stress and mechanically sweep away healthy brain ECs. However, we did not find any BCECs in peripheral blood during 30 and 60 min of seizures, coinciding with the occurrence of maximal cerebral hyperemia. BCECs appear only 2–4 h after seizure onset, when cerebral blood flow returns to baseline values. Therefore, it is unlikely that CECs represent healthy ECs washed off cerebral vessels by the shear force of cerebral hyperemia. Furthermore, we addressed the question of whether the appearance of BCECs could be related to changes in blood pressure. In pancuronium-paralyzed animals, seizures cause only moderate increase in MABP (12, 53). Similar to the newborn pig model, seizures in newborn babies also do not produce large changes in arterial pressure (9, 10). Importantly, we found no differences between MABP values in the different experimental groups. These data strongly suggest that significant differences in BCEC numbers among the control, CORM-A1-treated, and CoPP-treated groups are not due to the differences in hemodynamic parameters.

The appearance of BCECs in the blood is related to apoptosis in the cerebral vascular bed caused by seizures. Epileptic seizures involve the excessive release of the major excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, which reaches neurotoxic concentrations. The cytotoxic effects of glutamate are not limited to neurotoxicity. Importantly, the cerebral vascular endothelium expresses a variety of glutamate receptors and therefore represents a direct target for glutamate (22, 52). Excitotoxic levels of glutamate cause damage of the cerebral vascular endothelium by apoptosis (48). In piglet cerebral vascular ECs, glutamate initiates a series of apoptotic events that include caspase-3 activation, nuclear translocation of NF-κB, and DNA fragmentation (48). Apoptosis is accompanied by the loss of cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts, leading to the detachment of ECs from the matrix, which occurs within 4 h after glutamate stimulation (48). The apoptosis-related loss of cell contacts in the cerebral vascular endothelium has also been observed in the response to TNF-α, an inflammatory mediator (5). Furthermore, we present here novel evidence that epileptic seizures cause apoptosis in the cerebral vasculature in vivo. Advanced apoptosis, detected as DNA fragmentation by TUNEL assay, was observed 4 h after seizure onset, which coincides with the appearance of BCECs in the peripheral blood. CO prevents the apoptosis-related detachment of cultured brain ECs by decreasing oxidative stress and stabilizing cell-cell and cell-substrate contacts (4, 5). These data were confirmed by our present in vivo observations on the reduction of apoptosis and prevention of endothelial sloughing from cerebral vessels upon increasing the brain CO level by upregulating HO-1 expression or by treatment with CORM-A1. Overall, it is reasonable to conclude that BCECs are damaged ECs that have sloughed off of cerebral vessels into the bloodstream as a result of apoptosis initiated by seizure-related cerebrovascular stress.

Seizure-induced BCECs had a limited ability to attach to the matrix-covered surfaces and proliferate in EC growth media. Substantial cell growth occurred only in few cases (10–15%) and was observed after 2–3 wk in culture. Late outgrowth cells expressed mature endothelial markers and blood-brain barrier markers but had an altered cytoskeleton and were not capable of forming EC contacts and a confluent monolayer. Similarly, cultured ECs from cerebral microvessels dislodged from the matrix as a result of glutamate-induced apoptosis were not able to reattach and grow in EC media (data not shown). A limited proliferative capacity is also characteristic of CECs derived from the systemic vasculature of patients with coronary artery disease, diabetes, septic shock, and sickle cell anemia (24, 32, 42, 55, 59). It is unlikely that the late outgrowth originated from endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). EPCs from peripheral blood MNCs and other sources are defined by a high proliferative potential and the ability to differentiate into mature ECs in 7 days (18). This was not observed in our experiments. The low proliferative capacities of seizure-induced BCECs further suggest that these are mainly irreversibly damaged cells.

An important question to be addressed is what is the functional significance of changes in BCECs and apoptosis in cerebral vasculature? We hypothesized that BCECs are early peripheral markers of cerebrovascular disease. To test this hypothesis, we directionally modulated the late cerebrovascular outcome of seizures to create various models of seizures with deleterious (control) and improved long-term cerebral vascular outcome based on our previous studies (12, 49, 66). Epileptic seizures cause a loss of cerebrovascular dilatory functions during the late postictal period (2 days after an ictal episode) (49, 66). We demonstrated that the loss of cerebrovascular function is largely prevented in piglets with an increased level of CO, a cerebroprotective mediator (49, 51, 66). CO is endogenously produced by the brain and cerebral vasculature via the actions of HO (inducible HO-1 and constitutive HO-2 isoforms) (52). The long-term cerebral vascular outcome of seizures can be greatly improved by compounds that increase the endogenous level of CO in the brain by upregulating HO-1 expression or pharmacologically by a CO-releasing compound, CORM-A1 (49, 66). If our hypothesis on the functional relationships between BCECs, apoptosis, and loss in cerebral vascular function is correct, we would anticipate that the animals with improved long-term cerebral vascular outcome have less BCECs and little or no apoptotic changes in cerebral vessels. Indeed, our data demonstrate that this is the case. In both CoPP- and CORM-A1-treated piglets, we did not observe the appearance of BCECs, apoptotic changes in cerebral vessels, or loss of endothelial vasodilator function. Overall, cerebroprotective interventions that ameliorate the late loss of cerebrovascular endothelial function also prevent apoptosis in the cerebral vasculature as well as the appearance of BCECs in peripheral blood. These findings clearly indicate causative relationships between the initiation of cerebrovascular apoptosis, the early appearance of BCECs, and the late loss of cerebrovascular functions caused by seizures.

We conclude that seizures result in ECs sloughing from cerebral vessels and the early appearance of BCECs in peripheral blood that detach from the vessel wall as a result of advanced apoptosis and loss of cell contacts. Seizure-induced endothelial denudation of cerebral vessels leads to sustained loss of cerebral vascular endothelium-dependent vasodilator function during the late postictal period. Hence, we propose that BCECs are early noninvasive diagnostic markers of cerebrovascular disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-NS-046385 and R01-HL-042851 and by American Heart Association Grant R073037263. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or American Heart Association.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the technical expertise of Alex L. Fedinec, Danny Morse, and Greg Short.

Present address for A. Zimmermann: Dept. of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Szeged, Szeged H-6720, Hungary.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham NG, Rezzani R, Rodella L, Kruger A, Taller D, Volti GL, Goodman AI, Kappas A. Overexpression of human heme oxygenase-1 attenuates endothelial cell sloughing in experimental diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2468–H2477, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argandona EG, Bengoetxea H, Lafuente JV. Lack of experience-mediated differences in the immunohistochemical expression of blood-brain barrier markers (EBA and GluT-1) during the postnatal development of the rat visual cortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 156: 158–166, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardin N, Anfosso F, Masse JM, Cramer E, Sabatier F, Bivic AL, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. Identification of CD146 as a component of the endothelial junction involved in the control of cell-cell cohesion. Blood 98: 3677–3684, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basuroy S, Bhattacharya S, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Nox4 NADPH oxidase mediates oxidative stress and apoptosis caused by TNF-α in cerebral vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C422–C432, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basuroy S, Bhattacharya S, Tcheranova D, Qu Y, Regan RF, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Heme oxygenase-2 provides endogenous protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis caused by TNF-α in cerebral vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C897–C908, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blann AD, Woywodt A, Bertolini F, Bull TM, Buyon JP, Clancy RM, Haubitz M, Hebbel RP, Lip GYH, Mancuso P, Sampol J, Solovey A, Dignat-George F. Circulating endothelial cells. Biomarker of vascular disease. Thromb Haemost 93: 228–235, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolwig TG. Blood-brain barrier studies with special reference to epileptic seizures. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 345: 15–20, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boos CJ, Blann AD, Lip GY. Assessment of endothelial damage/dysfunction: a focus on circulating endothelial cells. Method Mol Med 139: 211–224, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Börch K, Pryds O, Holm S, Lou H, Greisen G. Regional cerebral blood flow during seizures in neonates. J Pediatr 132: 431–435, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boylan GB, Panerai RB, Rennie JM, Evans DH, Rabe-Hesketh S, Binnie CD. Cerebral blood flow velocity during neonatal seizures. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 80: F105–F110, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bye AM, Flanagan D. Spatial and temporal characteristics of neonatal seizures. Epilepsia 36: 1009–1016, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carratu P, Pourcyrous M, Fedinec A, Leffler CW, Parfenova H. Endogenous heme oxygenase prevents impairment of cerebral vascular functions caused by seizures. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1148–H1157, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassella JP, Lawrenson JG, Allt G, Firth JA. Ontogeny of four blood-brain barrier markers: an immunocytochemical comparison of pial and cerebral cortical microvessels. J Anat 189: 407–415, 1996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clancy RR. Summary proceedings from the neurology group on neonatal seizures. Pediatrics 117: S23–S27, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czapinski P, Blaszczyk B, Czuczwar SJ. Mechanisms of action of antiepileptic drugs. Curr Top Med Chem 5: 3–14, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cornford EM. Epilepsy and the blood brain barrier: endothelial cell responses to seizures. Adv Neurol 79: 845–862, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornford EM, Hyman S. Localization of brain endothelial luminal and abluminal transporters with immunogold electron microscopy. NeuroRx 2: 27–43, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debatin KM, Wei J, Beltinger C. Endothelial progenitor cells for cancer gene therapy. Gene Ther 15: 780–786, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duda DG, Cohen KS, di Tomaso E, Au P, Klein RJ, Scadden DT, Willett CG, Jain RK. Differential CD146 expression on circulating versus tissue endothelial cells in rectal cancer patients: implications for circulating endothelial and progenitor cells as biomarkers for antiangiogenic therapy. J Clin Oncol 24: 1449–1453, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erdbruegger U, Haubitz M, Woywodt A. Circulating endothelial cells: a novel marker of endothelial damage. Clin Chim Acta 373: 17–26, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher RS, Schachter SC. The postictal state: a neglected entity in the management of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 1: 52–59, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiumana E, Parfenova H, Jaggar JH, Leffler CW. Carbon monoxide mediates vasodilator effects of glutamate in isolated pressurized cerebral arterioles of newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1073–H1079, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Y, Liu C, Zhang X, Gao J, Yang C. Circulating endothelial cells as potential markers of atherosclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 35: 638–642, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghani U, Shuaib A, Salam A, Nasir A, Shuaib U, Jeerakathil T, MD , Sher F, O'Rourke F, Nasser AM, Schwindt B, Todd K. Endothelial progenitor cells during cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 36: 151–153, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haubitz M, Woywodt A. Circulating endothelial cells and vasculitis. Intern Med 43: 660–667, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes GL. The long-term effects of seizures on the developing brain: clinical and laboratory issues. Brain Dev 13: 393–409, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ilan N, Madri JA. PECAM-1: old friend, new partners. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15: 515–524, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingram DA, Caplice NM, Yoder MC. Unresolved questions, changing definitions, and novel paradigms for defining endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 106: 1525–1531, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klepper J, Leiendecker B. GLUT1 deficiency syndrome–2007 update. Dev Med Child Neurol 49: 707–716, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee KW, Lip GYH, Tayebjee M, Foster W, Blann AD. Circulating endothelial cells, von Willebrand factor, interleukin-6, and prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Blood 105: 526–532, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leffler CW, Mirro R, Shanklin DR, Armstead WM, Shibata M. Light/dye microvascular injury selectively eliminates hypercapnia-induced pial arteriolar dilation in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H623–H630, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Y, Weisdorf DJ, Solovey A, Hebbel RP. Origins of circulating endothelial cells and endothelial outgrowth from blood. J Clin Invest 105: 71–77, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makin AJ, Blann AD, Chung NAY, Silverman SH, Lip GYH. Assessment of endothelial damage in atherosclerotic vascular disease by quantification of circulating endothelial cells. Relationship with von Willebrand factor and tissue factor. Eur Heart J 25: 371–376, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McBride MC, Laroia N, Guillet R. Electrographic seizures in neonates correlate with poor neurodevelopmental outcome. Neurology 55: 506–513, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCabe BK, Silveira DC, Cilio MR, Cha BH, Liu X, Sogawa Y, Holmes GL. Reduced neurogenesis after neonatal seizures. J Neurosci 21: 2094–2103, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClung JA, Naseer N, Saleem M, Rossi GP, Weiss MB, Abraham NG, Kappas A. Circulating endothelial cells are elevated in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus independently of HbA1c. Diabetologia 48: 345–350, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNamara JO, Huang YZ, Leonard AS. Molecular signaling mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis. Sci STKE 2006: re12, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meldrum BS. Concept of activity-induced cell death in epilepsy: historical, and contemporary perspectives. Prog Brain Res 135: 3–11, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizrahi EM. Acute and chronic effects of seizures in the developing brain: lessons from clinical experience. Epilepsia 40: S42–S50, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motterlini R, Sawles P, Hammad J, Bains S, Alberto R, Foresti R, Green CJ. CORM-A1: a new pharmacologically active carbon monoxide-releasing molecule. FASEB J 19: 284–286, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mutin M, Canavy I, Blann A, Bory M, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. Direct evidence of endothelial injury in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina by demonstration of circulating endothelial cells. Blood 93: 2951–2958, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mutunga M, Fultan B, Bullock R, Batchelor A, Gascoigne A, Gillespie JI, Baudouin SV. Circulating endothelial cells in patients with septic shock. Am J Respir Care Med 163: 195–200, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nadar SK, Lip GY, Lee KW, Blann AD. Circulating endothelial cells in acute ischaemic stroke. Thromb Haemost 94: 707–712, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakatani K, Takeshita S, Tsujimoto H, Kawamura Y, Tokutomi T, Sekine I. Circulating endothelial cells in Kawasaki disease. Clin Exp Immunol 131: 536–540, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ortibus EL, Sum JM, Hahn JS. Predictive value of EEG for outcome and epilepsy following neonatal seizures. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 98: 175–185, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oztas B, Kilic S, Dural E, Ispir T. Influence of antioxidants on the blood-brain barrier permeability during epileptic seizures. Int J Neurosci 105: 27–35, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pardridge WM, Boado RJ, Farrell CR. Brain-type glucose transporter (GLUT-1) is selectively localized to the blood-brain barrier. Studies with quantitative western blotting and in situ hybridization. J Biol Chem 265: 18035–18040, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parfenova H, Basuroy S, Bhattacharya S, Tcheranova D, Qu Y, Regan RF, Leffler CW. Glutamate induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in cerebral vascular endothelial cells: contributions of HO-1 and HO-2 to cytoprotection. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C1399–C13410, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parfenova H, Carratu P, Tcheranova D, Fedinec A, Pourcyrous M, Leffler CW. Epileptic seizures cause extended postictal cerebral vascular dysfunction that is prevented by HO-1 overexpression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2843–H2850, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parfenova H, Daley ML, Carratu P, Leffler CW. Heme oxygenase inhibition reduces neuronal activation evoked by bicuculline in newborn pigs. Brain Res 1014: 87–96, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parfenova H, Leffler CW. Cerebroprotective functions of HO-2. Curr Pharm Design 14: 443–453, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parfenova H, Neff RA, 3rd, Alonso JS, Shlopov BV, Jamal CN, Sarkisova BV, Leffler CW. Cerebral vascular endothelial heme oxygenase: expression, localization, and activation by glutamate. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1954–C1963, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pourcyrous M, Leffler CW, Bada HS, Korones SB, Stidham GL, Busija DW. Effects of pancuronium bromide on cerebral blood flow changes during seizures in newborn pigs. Pediatr Res 31: 636–639, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raol YH, Lynch DR, Brooks-Kayal AR. Role of excitatory amino acids in developmental epilepsies. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 7: 254–260, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodella L, Lamon BD, Rezzani R, Sangras B, Goodman AI, Falck JR, Abraham NG. Carbon monoxide and biliverdin prevent endothelial cell sloughing in rats with type I diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 2198–2205, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scher MS, Aso K, Beggarly ME, Hamid MY, Steppe DA, Painter MJ. Electrographic seizures in preterm and full term neonates: clinical correlates, associated brain lesions and risk for neurological sequelae. Pediatrics 91: 128–134, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scher MS, Hamid MY, Steppe DA, Baggarly ME, Painter MJ. Ictal and interictal electrographic seizure durations in preterm and term neonates. Epilepsia 34: 284–288, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Slamberova R, Rokyta R. Occurrence of bicuculline-, NMDA- and kainic acid-induced seizures in prenatally methamphetamine-exposed adult male rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 372: 236–241, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solovey A, Lin Y, Browne P, Choong S, Wayner E, Hebbel RP. Circulating activated endothelial cells in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med 337: 1584–1590, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sperk G, Lassmann H, Baran H, Kish SJ, Seitelberger F, Hornykiewicz O. Kainic acid induced seizures: neurochemical and histopathological changes. Neuroscience 10: 1301–1315, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Volpe JJ. Neonatal seizures. In: Neurology of the Newborn (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2001, p. 178–214 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang D, Pascual JM, Yang H, Engelstad K, Jhung S, Sun RP, De Vivo DC. Glut-1 deficiency syndrome: clinical, genetic, and therapeutic aspects. Ann Neurol 57: 111–118, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wasterlain CG. Recurrent seizures in the developing brain are harmful. Epilepsia 38: 728–734, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wasterlain CG, Niquet J, Thompson KW, Baldwin R, Liu H, Sankar R, Mazarati AM, Naylor D, Katsumori H, Suchomelova L, Shirasaka Y. Seizure-induced neuronal death in the immature brain. Prog Brain Res 135: 335–353, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willis AP, Leffler CW. Endothelial NO and prostanoid involvement in newborn and juvenile pig pial arteriolar responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H2366–H2377, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimmermann A, Leffler CW, Tcheranova D, Fedinec AL, Parfenova H. Cerebroprotective effects of the CO-releasing molecule CORM-A1 against seizure-induced neonatal vascular injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2501–H2507, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]