Abstract

Recent data suggest adiponectin, an adipocyte-derived hormone, affects development of heart failure in response to hypertension. Severe short-term pressure overload [1–3 wk of transverse aortic constriction (TAC)] in adiponectin−/− mice causes greater left ventricle (LV) hypertrophy than in wild-type (WT) mice, but conflicting results are reported regarding LV remodeling, with either increased or decreased LV end diastolic volume compared with WT mice. Here we assessed the effects of prolonged TAC on LV hypertrophy and remodeling. WT and adiponectin−/− mice were subjected to TAC and maintained for 6 wk. Regardless of strain, TAC induced similar LV hypertrophy (∼70%) and upregulation of mRNA for heart failure marker genes. However, LV chamber size was dramatically different, with classic LV dilation in WT TAC mice but concentric LV hypertrophy in adiponectin−/− mice. LV end diastolic and systolic volumes were lower and ejection fraction higher in adiponectin−/− TAC mice compared with WT, indicating that adiponectin deletion prevented LV remodeling and deterioration in systolic function. The activities of marker enzymes of mitochondrial oxidative capacity were reduced in WT TAC mice by ∼35%, whereas enzyme activities were maintained at sham levels in adiponectin−/− TAC mice. In conclusion, in WT mice, long-term pressure overload caused dilated LV hypertrophy accompanied by decreased activity of mitochondrial oxidative enzymes. Although adiponectin deletion did not affect LV hypertrophy, it prevented LV chamber remodeling and preserved mitochondrial oxidative capacity, suggesting that adiponectin plays a permissive role in mediating changes in cardiac structure and metabolism in response to pressure overload.

Keywords: adipokine, cardiac, heart failure, hypertrophy, mitochondria

left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy in individuals with hypertension is a leading cause of heart failure (14). Hypertension increases wall stress, leading to compensatory cardiomyocyte growth and greater ventricular wall thickness, which frequently progresses to LV chamber dilation, wall thinning, and contractile dysfunction (2, 9). The molecular mechanisms underlying the progression from compensated hypertrophy to dilated heart failure are not well-understood. The pathological hypertrophic response of the LV to pressure overload has been well-documented in the mouse model of transverse aortic constriction (TAC), which in normal mice results in LV chamber expansion and contractile dysfunction, as evidenced by a decrease in ejection fraction and elevated end systolic and diastolic volumes (20). One factor that may affect the development of LV hypertrophy and progression to heart failure with an enlarged LV chamber is adiponectin, an insulin-sensitizing, anti-inflammatory adipokine (11). Adiponectin is primarily secreted by adipose tissue and exerts protective effects on the heart and vasculature (28, 31, 32). It is one of the most abundant proteins in plasma (3–30 μg/ml) and occurs in three major oligomeric forms (trimer, hexamer, and high-molecular-weight form) in human and rodent plasma (10, 11, 13). Circulating adiponectin is inversely associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and, in some cases, coronary artery disease (11, 17, 19). Adiponectin also plays a regulatory role in glucose and fat metabolism, although the exact mechanisms are unclear (36).

The role of adiponectin in the development and progression of heart failure is unclear, with generally cardioprotective effects found in studies in transgenic animals (22, 31) and clinical studies finding that elevated adiponectin is a strong positive predictor of poor outcome in heart failure patients (7, 8, 15, 18). Adiponectin deficiency has shown varying results under conditions of pressure overload in mice. Shibata et al. (31) found that mice with adiponectin deficiency subjected to 1 wk of pressure overload induced by TAC did not exhibit the typical LV hypertrophy and chamber dilation observed in wild-type (WT) mice but rather had concentric LV hypertrophy (31). Moreover, mice with adiponectin deficiency had greater mortality than WT mice following 1 wk of TAC (31). Liao et al. (22) observed that 3 wk of TAC resulted in a similar increase in mortality but a greater LV end diastolic volume and lower ejection fraction in mice with adiponectin deficiency compared with WT mice. In light of clinical studies showing a negative predictive value for adiponectin in heart failure patients, it is important to more fully investigate the effects of adiponectin on LV chamber remodeling with more long-term cardiac stress.

LV hypertrophy and heart failure also reduce the capacity for mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in the myocardium, particularly for fatty acid oxidation (34), which is associated with LV chamber expansion (26). If adiponectin deletion prevents LV dilation in response to pressure overload-induced LV hypertrophy (31), then it would be expected to also prevent the well-documented downregulation of cardiac mitochondrial oxidative capacity.

The purpose of the present study was to determine the role of adiponectin in the development of cardiac hypertrophy, LV remodeling, and systolic dysfunction in response to prolonged chronic aortic pressure overload. Male WT and adiponectin-deficient mice were subjected to pressure overload and maintained for 6 wk. We hypothesized that, compared with WT mice, adiponectin-deficient mice would: 1) display increased LV hypertrophy, 2) less LV dilation, and 3) maintenance of mitochondrial enzyme activities in response to chronic pressure overload.

METHODS

Experimental design.

Investigators were blinded to treatment when measurements were performed. The animal protocol was conducted according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 85-23) and was approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All procedures were performed between 3 and 6 h from the start of the light phase. Adiponectin−/− mice were generated on a C57BL/6J background as previously described (23). Male WT mice and adiponectin−/− mice were subjected to pressure overload or sham surgery (n = 12–15/group) and fed a standard commercial rodent chow. Tail blood pressures were measured at 3–4 wk using the tail cuff system. At 6 wk, LV function was analyzed by echocardiography, and 1–3 days later mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, blood was drawn by cardiac puncture in the right ventricle, urine was collected by puncture from the bladder, and the heart was harvested for biochemical analysis.

Induction of pressure overload.

TAC was performed on male C57BL/6J (WT) and adiponectin−/− mice (aged 8 wk, weighing 20–25 g) as described previously using a 27-gauge needle (1, 12, 21). The sham procedure was identical without aortic ligation. Animals were maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle.

Echocardiography.

LV function was assessed using a Vevo 770 High-Resolution Imaging System (Visual Sonics) with a 30-MHz linear array transducer (model 716). Anesthetized mice were shaved and placed supine on a warming pad. Two-dimensional cine loops and guided M-mode frames were recorded from the parasternal short and long axis. At the end of the study, all data were analyzed offline with software resident on the ultrasound system, and calculations were made to determine LV volumes as previously described (5, 6). Ejection fraction was calculated as: (EDV − ESV)/EDV × 100, where EDV is the end diastolic volume and ESV is the end systolic volume.

Tail cuff blood pressure and heart rate measurement.

Systolic blood pressure and heart rates were measured at 3–4 wk postsurgery on unanesthetized mice using a Hatteras Instruments SC1000 Dual-Channel Blood Pressure Analysis System (Cary, NC). Mice were warmed to increase blood flow in the tail. Animals were subjected to analysis on three consecutive days, each analysis consisting of a 5-min preliminary acclimation phase followed by 10 min of data recording. Systolic blood pressure and heart rates were recorded each minute for the 10-min period. Reported values are the means ± SE for all values obtained over the three consecutive days.

Metabolic and biochemical parameters.

Free fatty acids, triglycerides, and glucose (Wako, Richmond, VA) were assessed in the serum using enzymatic spectrophotometric methods as previously described (6). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were used to measure leptin and insulin (both from Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH) and adiponectin (Millipore, St. Charles, MO) levels in the serum (6). Tissue levels of triglycerides were measured in liver using enzymatic spectrophotometric methods. Activities of the mitochondrial marker enzymes citrate synthase and medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) were measured spectrophotometrically in the LV (6). Protein levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 were measured from LV tissue (n = 5–7/group) by ELISA (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK).

LV histology.

Histological analyses were performed on LV tissue from the lateral free wall for myocyte cross-sectional area, interstitial fibrosis, and capillary density, and oxygen diffusion distance was calculated as previously described (29).

Analysis of mRNA expression.

For assessment of mRNA expression, frozen LV tissue was homogenized using a Bullet Blender, and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Real-time RT-PCR was performed using an ABI 7900 Detection System as previously described (4, 5). The following genes were analyzed using TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA): atrial natriuretic peptide (Nppa, Mm01255747_g1); myosin heavy chain α (Myh6, Mm00440354_m1); myosin heavy chain β (Myh7, Mm00600555_m1); MCAD (Acadm, Mm00431611_m1); citrate synthase (Cs, Mm00466043_m1); uncoupling protein 3 (Ucp3, Mm01163394_m1); pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (Pdk4, Mm00443325_m1); MMP1 (Mmp1, Mm01168713_m1), MMP2 (Mmp2, Mm00439506_m1), and MMP9 (Mmp9, Mm00600164_g1); and cyclophilin A (ppia, Mm02342430_g1). A similar protocol was followed to isolate RNA from frozen epididymal fat samples, and RT-PCR was performed for adiponectin (Adipoq, Mm00456425_m1). mRNA cycle threshold values for these genes were normalized to housekeeping gene cyclophilin A and expressed as fold change relative to the standard chow sham group.

Statistical analysis.

Two-way ANOVA with the Bonferonni post hoc adjustment was used to evaluate the differences among groups based on genotype or surgical intervention. Potential differences in survival were tested using a log rank test (Sigma Stat 3.5). All data are presented as means ± SE. P < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

RESULTS

LV mass, remodeling, and contractile function.

Body masses were slightly lower in adiponectin−/− mice at baseline, but there were no differences in body mass at the end of the study (Table 1). There was 100% survival in all sham animals, but survival in TAC animals was lower in WT mice (71%) compared with adiponectin−/− mice (100%) (P = 0.03). LV mass was increased by ∼70% in response to TAC in both WT and adiponectin−/− mice (Fig. 1A), indicating LV hypertrophy. Atrial mass relative to tibia length was increased with TAC only in WT mice, and right ventricular mass relative to tibia length was increased in adiponectin−/− mice only (Table 1). The ratio of wet to dry lung weight, which is an indicator of pulmonary congestion, was not different among any of the groups, suggesting that none of the animals were in end-stage heart failure. Tail artery systolic blood pressure was significantly higher in both adiponectin−/− groups compared with WT and was reduced with TAC in WT mice (Table 1). Heart rate was elevated in response to TAC in WT mice only (Table 1). Atrial natriuretic peptide mRNA expression increased 10- to 12-fold in TAC mice regardless of strain (Fig. 1B). In addition, the ratio for myosin heavy chain β/α was markedly increased in response to TAC (∼40-fold relative) in both WT and adiponectin−/− mice (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results suggest that there was a similar degree of pathological LV hypertrophy in WT and adiponectin−/− mice subjected to TAC.

Table 1.

Body and heart parameters 6 wk postsurgery

| Sham |

TAC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | APN−/− | WT | APN−/− | |

| Baseline body mass, g | 23.2 ± 0.4 | 21.7 ± 0.4† | 22.9 ± 0.3 | 21.5 ± 0.3† |

| Terminal body mass, g | 28.0 ± 0.6 | 26.6 ± 0.8 | 26.1 ± 0.1 | 26.5 ± 0.7 |

| Tibia length, mm | 19.4 ± 0.2 | 18.9 ± 0.3 | 19.2 ± 0.2 | 18.7 ± 0.2 |

| Atrial mass/tibia length, mg/cm | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 0.55 ± 0.06 | 1.60 ± 0.29* | 1.00 ± 0.09† |

| RV mass/tibia length, mg/cm | 2.33 ± 0.34 | 1.89 ± 0.17 | 2.63 ± 0.22 | 2.78 ± 0.33* |

| Wet/dry lung weight | 4.52 ± 0.09 | 4.62 ± 0.11 | 4.58 ± 0.14 | 4.74 ± 0.18 |

| Aortic outflow tract diameter, mm | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 1.33 ± 0.07 | 1.46 ± 0.03* | 1.44 ± 0.05 |

| Systolic posterior wall thickness, mm | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 0.91 ± 0.05 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 1.26 ± 0.07*† |

| Diastolic posterior wall thickness, mm | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 0.73 ± 0.06 | 1.04 ± 0.07*† |

| Systolic anterior wall thickness, mm | 1.18 ± 0.05 | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 1.17 ± 0.06 | 1.59 ± 0.06*† |

| Diastolic anterior wall thickness, mm | 0.83 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.07 | 0.88 ± 0.08 | 1.25 ± 0.06*† |

| Relative wall thickness, mm | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.55 ± 0.05*† |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 112 ± 3 | 120 ± 3† | 99 ± 2* | 112 ± 3*† |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 597 ± 14 | 604 ± 13 | 637 ± 11* | 619 ± 11 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 12–15 mice/group. TAC, transverse arotic constriction; WT, wild type; APN−/−, adiponectin deficiency; RV, right ventricle.

P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vs. WT (†).

Fig. 1.

Left ventricular (LV) mass/tibia length (A), the mRNA expression atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP, B) and the ratio of the mRNA expression of myosin heavy chain-β to -α (C) expressed as a fraction of the sham wild-type (WT) group. TAC, transverse aortic constriction. Values are means ± SE; n = 12–15 mice/group. *P < 0.05 vs. sham.

The structural changes of the LV in response to TAC were drastically different between WT and adiponectin−/− mice. Relative wall thickness was greater in adiponectin−/− TAC mice but unchanged in WT TAC mice (Table 1). This is supported by the increase in anterior and posterior wall thicknesses at systole and diastole in response to TAC in adiponectin−/− mice only (Table 1). Furthermore, EDV and ESV were both markedly increased in WT mice after TAC but unchanged in adiponectin−/− TAC mice compared with sham (Fig. 2, A and B). The LV mass-to-EDV ratio, which shows differences in remodeling kinetics after TAC, was elevated in the adiponectin−/− mice with TAC (Fig. 2C). Ejection fraction was also preserved in adiponectin−/− mice subjected to TAC (Fig. 2D), whereas it was significantly decreased in WT TAC mice compared with sham. Thus the dilated LV hypertrophy that develops in response to TAC in WT animals is prevented by adiponectin deletion despite a similar degree of LV hypertrophy.

Fig. 2.

Echocardiographic assessment of end diastolic volume (A), end systolic volume (B), LV mass to end diastolic volume (EDV) ratio (C), and ejection fraction (D) 6 wk postsurgery. Values are means ± SE; n = 12–15 mice/group. P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vs. wild type (#).

Markers of mitochondrial function.

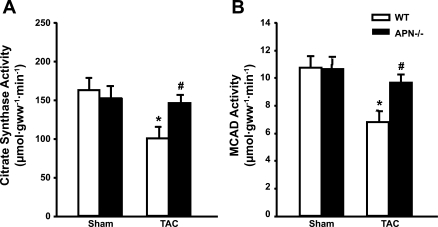

In LV hypertrophy and heart failure, mitochondrial function and the fatty acid oxidation pathway are impaired (34). The activities of mitochondrial oxidative marker enzymes, MCAD and citrate synthase, were ∼35–40% lower in WT mice after TAC but were preserved in adiponectin−/− TAC mice (Fig. 3, A and B). The mRNA expression of citrate synthase was reduced by TAC in both strains; however, the mRNA for MCAD was reduced in response to TAC only in WT mice (Table 2), which mirrors the changes in MCAD enzyme activity.

Fig. 3.

Cardiac citrate synthase activity (A) and medium chain acyl CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) activity (B). Values are means ± SE; n = 12–15 mice/group. P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vs. wild type (#).

Table 2.

mRNA expression

| Sham |

TAC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | APN−/− | WT | APN−/− | |

| LV | ||||

| Citrate synthase | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 0.61 ± 0.04† | 0.54 ± 0.05* | 0.41 ± 0.05* |

| MCAD | 1.00 ± 0.33 | 0.64 ± 0.06 | 0.41 ± 0.05* | 0.33 ± 0.04 |

| Mmp1 | 1.00 ± 0.09 | 0.36 ± 0.04† | 0.86 ± 0.14 | 0.28 ± 0.06† |

| Mmp2 | 1.00 ± 0.07 | 0.86 ± 0.19 | 1.66 ± 0.30* | 1.54 ± 0.17* |

| Mmp9 | 1.00 ± 0.16 | 1.65 ± 0.27 | 1.41 ± 0.45 | 0.84 ± 0.14* |

| Epididymal fat | ||||

| Adiponectin | 1.00 ± 0.17 | 0† | 1.04 ± 0.14 | 0† |

Data are expressed as a fraction of the WT sham group. Values are means ± SE; n = 12–15 mice/group. LV, left ventricle; MCAD, medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase; Mmp, matrix metalloproteinase.

P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vs. WT (†).

Metabolic parameters.

Serum adiponectin, as measured using a commercial ELISA kit, was significantly reduced by ∼80% in both adiponectin−/− groups (Table 3), and the mRNA level of adiponectin was undetectable in the epididymal fat pads of adiponectin−/− mice (Table 2). Serum glucose, free fatty acids, triglycerides, leptin, and insulin were not different among any of the groups (Table 3). The levels of triglycerides in the liver were not altered by surgery or genotype (Table 3).

Table 3.

Metabolic parameters

| Sham |

TAC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite | WT | APN−/− | WT | APN−/− |

| Serum adiponectin, μg/ml | 7.94 ± 1.23 | 1.70 ± 0.12† | 7.72 ± 1.27 | 1.50 ± 0.10† |

| Serum glucose, mM | 12.7 ± 0.6 | 13.0 ± 0.9 | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 11.7 ± 0.4 |

| Serum triglycerides, mg/ml | 0.26 ± 0.05 | 0.40 ± 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.07 | 0.30 ± 0.04 |

| Serum FFA, mM | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.14 | 0.61 ± 0.07 |

| Serum insulin, ng/ml | 0.66 ± 0.16 | 0.84 ± 0.23 | 0.66 ± 0.16 | 0.60 ± 0.10 |

| Serum leptin, ng/ml | 2.56 ± 0.51 | 3.83 ± 1.50 | 1.62 ± 0.37 | 1.85 ± 0.43 |

| Liver triglycerides, mg/g wet wt | 16.7 ± 2.4 | 16.7 ± 1.2 | 14.0 ± 2.1 | 13.3 ± 1.7 |

| LV MMP2, ng/mg protein | 2.71 ± 0.25 | 2.79 ± 0.39 | 2.80 ± 0.49 | 2.35 ± 0.39 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 12–15 mice/group for all metabolites except MMP2 (n = 5–7/group). FFA, free fatty acid.

P < 0.05 vs. WT (†).

LV histology.

Myocyte cross-sectional area was increased in adiponectin−/− sham mice compared with WT sham mice, and it was also increased with TAC in both strains (Table 4). There was a main effect for increased interstitial fibrosis with TAC (P = 0.023) but no difference between WT and adiponectin−/− mice. Capillary density was decreased in response to TAC in both strains, and it was also lower in adiponectin−/− sham mice compared with WT sham mice (Table 4). Oxygen diffusion distance was elevated in adiponectin−/− sham mice and WT TAC mice compared with WT sham mice. Representative images have been included in the data supplement [Supplemental Fig. S1 (Supplemental data for this article may be found on the American Journal of Physiology: Heart and Circulatory Physiology website.)].

Table 4.

LV histology

| Sham |

TAC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | APN−/− | WT | APN−/− | |

| Myocyte cross-sectional area, μm2 | 416 ± 19 | 507 ± 30† | 581 ± 21* | 637 ± 30* |

| Interstitial fibrosis, % | 13.9 ± 1.3 | 14.1 ± 1.1 | 16.6 ± 1.2 | 17.3 ± 1.5 |

| Capillary density, capillary/mm2 | 2,717 ± 174 | 2,264 ± 160† | 2,028 ± 123* | 1,847 ± 121* |

| Oxygen diffusion distance, μm | 10.5 ± 0.4 | 12.2 ± 0.6† | 13.4 ± 0.3* | 13.1 ± 0.5 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 7–8 mice/group. P < 0.05 vs. sham (*) and vs. WT (†).

MMP.

MMPs are a class of proteins actively involved in LV remodeling and hypertrophy, and increased expression of MMP can often be seen at the mRNA level (33). The mRNA levels of MMP1, MMP2, and MMP9 were differentially affected by surgery and genotype. The expression of MMP1 was reduced in both adiponectin−/− groups, and MMP2 was increased in TAC groups regardless of strain. The expression of MMP9 was decreased in adiponectin−/− TAC mice only (Table 2). The protein level of MMP2, as measured by ELISA, was unaffected by surgery or strain (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The primary goal of the present study was to determine the effects of adiponectin deficiency on the development of LV hypertrophy and heart failure in response to prolonged pressure overload. The extent of LV hypertrophy was similar in WT and adiponectin−/− mice; however, the pattern of LV remodeling was strikingly different. There was clear evidence of dilation and systolic dysfunction in WT mice but pronounced concentric hypertrophy and preserved systolic function in adiponectin−/− mice. Furthermore, although WT mice exhibited the well-described decrease in the activity of mitochondrial oxidative enzymes that typically occurs in advanced pathological LV hypertrophy and heart failure (34), the activities were maintained in adiponectin−/− mice subjected to TAC. Taken together, it appears that adiponectin plays a permissive role in the structural and metabolic cardiac remodeling that are hallmarks of pathological cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure.

The decrease in mitochondrial enzyme activities in WT mice and preservation in adiponectin−/− mice suggest that the classic downregulation of these enzymes in heart failure is the result of expansion of LV chamber volume and is not due to pathological cardiac hypertrophy per se. Maintenance of mitochondrial enzyme activities in adiponectin−/− mice after cardiac hypertrophy indicates that adiponectin plays a permissive role in decreasing mitochondrial oxidative capacity in response to TAC, as seen in WT mice. This effect could be due to direct actions of adiponectin on the myocardium or secondary to LV chamber expansion and elevation in wall stress.

Potential mechanisms for differences between WT and adiponectin−/− mice are likely due to differences in the activation of various remodeling pathways, such as MMPs. We found no consistent differences in MMP mRNA or protein levels between mouse strains. However, the activity levels of MMPs, such as MMP2 or MMP9, should be measured by zymography to determine if there are differences in collagen remodeling after TAC between WT and adiponectin−/− mice. Another potential mechanism responsible for the differences between strains is through apoptosis and related signaling. Although it is possible that apoptosis was elevated in WT mice in response to pressure overload, a recent study found that apoptosis does not play a significant role in the progression to heart failure in male mice until 12–16 wk (21), which is beyond the duration of our study. The role of apoptosis in the development and progression of heart failure is not well understood (3); however, there is no indication that apoptosis is altered in the adiponectin-deficient mice in the present study. Using TdT-dUTP nick end-labeling or annexin-V staining with more prolonged pressure overload to assess the potential differences in apoptosis between the two strains would be valuable. The results of this study indicate differences in LV structure and function at 6 wk, but it would be valuable to track the progression of adiponectin−/− TAC mice to concentric hypertrophy at earlier time points. In addition, maintaining mice for a longer duration would provide information on mortality and late-stage remodeling. It is unclear if adiponectin−/− mice will maintain thicker LV walls until they reach death or if they will progress to dilated heart failure. The structural and functional differences may be due to delayed progression to dilation in the adiponectin−/− mice. Clearly, adiponectin−/− and WT mice respond differently to pressure overload, but the exact timeline for these differences is not known.

Histological analysis demonstrated clearly cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in sham adiponectin−/− mice compared with WT mice; however, myocyte cross-sectional area was increased with TAC with no difference between strains. Assuming that adiponectin−/− mice have larger cardiomyocytes under conditions of normal blood pressure, this may confer protection in response to pressure overload due to a greater capacity to generate cardiac power when placed under chronic elevated work conditions. As expected, capillary density was also reduced in both strains with TAC, but it was lower in adiponectin−/− sham mice than WT sham mice. Because adiponectin is known to stimulate endothelial cell signaling in such a way that promotes capillary formation (27), this could explain the differences in capillary density in the sham animals. Interstitial fibrosis was not increased with TAC in each strain separately, but only as a main effect of pressure overload. The apparent lack of effect of adiponectin on interstitial fibrosis may be due to the unusually high levels of fibrosis in both sham groups, thereby eliminating the potential of adiponectin to reduce fibrosis. The specific relationship between adiponectin and fibrosis remains unclear.

While the majority of previously published reports support adiponectin as a cardioprotective adipokine (16, 19, 31, 32), its use as a biomarker for heart failure is uncertain (30). From a clinical perspective, serum adiponectin is associated with poor outcomes in heart failure patients (8, 25) and has been shown to either be a negative or positive predictor of coronary events (11, 17, 19). Elevated plasma adiponectin is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with heart failure (8, 18). In asymptomatic men, there is not a relationship between circulating adiponectin and incident heart failure (7, 15). Furthermore, in patients with established heart failure, adiponectin levels are elevated (24, 35) and associated with systolic dysfunction (25). The regulation of adiponectin levels and its prognostic value have not been evaluated over the course of the development and progression of heart failure.

In summary, we observed that, in normal mice, long-term pressure overload caused dilated LV hypertrophy accompanied by decreased activity of mitochondrial oxidative enzymes. Although adiponectin deletion did not affect LV hypertrophy, it prevented LV remodeling and preserved mitochondrial oxidative capacity, suggesting adiponectin plays a permissive but crucial role in mediating changes in cardiac structure and metabolism that are hallmarks of the cardiac response to pressure overload.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-074237 and HL-091307.

DISCLOSURES

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Kim Carpenter and Alexander Mamunes for help with the terminal surgeries and animal husbandry and Dr. Willem Kop for assistance in the statistical analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chess DJ, Xu W, Khairallah R, O'shea KM, Kop WJ, Azimzadeh AM, Stanley WC. The antioxidant tempol attenuates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and contractile dysfunction in mice fed a high-fructose diet. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2223–H2230, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diwan A, Dorn GW. Decompensation of cardiac hypertrophy: cellular mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Physiology (Bethesda) 22: 56–64, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorn GW. Apoptotic and non-apoptotic programmed cardiomyocyte death in ventricular remodelling. Cardiovasc Res 81: 465–473, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duda MK, O'Shea KM, Lei B, Barrows BR, Azimzadeh AM, McElfresh TE, Hoit BD, Kop WJ, Stanley WC. Low carbohydrate/high fat diet attenuates pressure overload induced ventricular remodeling and dysfunction. J Card Fail 14: 327–335, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duda MK, O'shea KM, Lei B, Barrows BR, Azimzadeh AM, McElfresh TE, Hoit BD, Kop WJ, Stanley WC. Dietary supplementation with omega-3 PUFA increases adiponectin and attenuates ventricular remodeling and dysfunction with pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res 76: 303–310, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duda MK, O'shea KM, Tintinu A, Xu W, Khairallah RJ, Barrows BR, Chess DJ, Azimzadeh AM, Harris WS, Sharov VG, Sabbah HN, Stanley WC. Fish oil, but not flaxseed oil, decreases inflammation and prevents pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res 81: 319–327, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel DS, Vasan RS, D'Agostino RB, Sr, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Wang TJ, Meigs JB. Resistin, adiponectin, and risk of heart failure the Framingham offspring study. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 754–762, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George J, Patal S, Wexler D, Sharabi Y, Peleg E, Kamari Y, Grossman E, Sheps D, Keren G, Roth A. Circulating adiponectin concentrations in patients with congestive heart failure. Heart 92: 1420–1424, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gradman AH, Alfayoumi F. From left ventricular hypertrophy to congestive heart failure: management of hypertensive heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 48: 326–341, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han SH, Quon MJ, Kim JA, Koh KK. Adiponectin and cardiovascular disease: response to therapeutic interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 531–538, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins TA, Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K. Adiponectin actions in the cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc Res 74: 11–18, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu P, Zhang D, Swenson L, Chakrabarti G, Abel ED, Litwin SE. Minimally invasive aortic banding in mice: effects of altered cardiomyocyte insulin signaling during pressure overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1261–H1269, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hug C, Lodish HF. The role of the adipocyte hormone adiponectin in cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol 5: 129–134, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: e1–e90, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingelsson E, Riserus U, Berne C, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Axelsson T, Lundmark P, Zethelius B. Adiponectin and risk of congestive heart failure. J Am Med Assoc 295: 1772–1774, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwashima Y, Katsuya T, Ishikawa K, Ouchi N, Ohishi M, Sugimoto K, Fu Y, Motone M, Yamamoto K, Matsuo A, Ohashi K, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Rakugi H, Matsuzawa Y, Ogihara T. Hypoadiponectinemia is an independent risk factor for hypertension. Hypertension 43: 1318–1323, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanaya AM, Wassel FC, Vittinghoff E, Havel PJ, Cesari M, Nicklas B, Harris T, Newman AB, Satterfield S, Cummings SR. Serum adiponectin and coronary heart disease risk in older Black and White Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 5044–5050, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kistorp C, Faber J, Galatius S, Gustafsson F, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Hildebrandt P. Plasma adiponectin, body mass index, and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 112: 1756–1762, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumada M, Kihara S, Sumitsuji S, Kawamoto T, Matsumoto S, Ouchi N, Arita Y, Okamoto Y, Shimomura I, Hiraoka H, Nakamura T, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with coronary artery disease in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 85–89, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei B, Chess DJ, Keung W, O'shea KM, Lopaschuk GD, Stanley WC. Transient activation of p38 MAP kinase and up-regulation of Pim-1 kinase in cardiac hypertrophy despite no activation of AMPK. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 404–410, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li XM, Ma YT, Yang YN, Liu F, Chen BD, Han W, Zhang JF, Gao XM. Downregulation of survival signalling pathways and increased apoptosis in the transition of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 36: 1054–1061, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao Y, Takashima S, Maeda N, Ouchi N, Komamura K, Shimomura I, Hori M, Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Kitakaze M. Exacerbation of heart failure in adiponectin-deficient mice due to impaired regulation of AMPK and glucose metabolism. Cardiovasc Res 67: 705–713, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda N, Shimomura I, Kishida K, Nishizawa H, Matsuda M, Nagaretani H, Furuyama N, Kondo H, Takahashi M, Arita Y, Komuro R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Tochino Y, Okutomi K, Horie M, Takeda S, Aoyama T, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Diet-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking adiponectin/ACRP30. Nat Med 8: 731–737, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McEntegart MB, Awede B, Petrie MC, Sattar N, Dunn FG, MacFarlane NG, McMurray JJ. Increase in serum adiponectin concentration in patients with heart failure and cachexia: relationship with leptin, other cytokines, and B-type natriuretic peptide. Eur Heart J 28: 829–835, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura T, Funayama H, Kubo N, Yasu T, Kawakami M, Saito M, Momomura S, Ishikawa SE. Association of hyperadiponectinemia with severity of ventricular dysfunction in congestive heart failure. Circ J 70: 1557–1562, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osorio JC, Stanley WC, Linke A, Castellari M, Diep QN, Panchal AR, Hintze TH, Lopaschuk GD, Recchia FA. Impaired myocardial fatty acid oxidation and reduced protein expression of retinoid X receptor-alpha in pacing-induced heart failure. Circulation 106: 606–612, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouchi N, Kobayashi H, Kihara S, Kumada M, Sato K, Inoue T, Funahashi T, Walsh K. Adiponectin stimulates angiogenesis by promoting cross-talk between AMP-activated protein kinase and Akt signaling in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 279: 1304–1309, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K. Targeting adiponectin for cardioprotection. Expert Opin Ther Targets 10: 573–581, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabbah HN, Stanley WC, Sharov VG, Mishima T, Tanimura M, Benedict CR, Hegde S, Goldstein S. Effects of dopamine beta-hydroxylase inhibition with nepicastat on the progression of left ventricular dysfunction and remodeling in dogs with chronic heart failure. Circulation 102: 1990–1995, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sam F, Walsh K. What can adiponectin say about left ventricular function? Heart 96: 331–332, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shibata R, Ouchi N, Ito M, Kihara S, Shiojima I, Pimentel DR, Kumada M, Sato K, Schiekofer S, Ohashi K, Funahashi T, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Adiponectin-mediated modulation of hypertrophic signals in the heart. Nat Med 10: 1384–1389, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibata R, Sato K, Pimentel DR, Takemura Y, Kihara S, Ohashi K, Funahashi T, Ouchi N, Walsh K. Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through. Nat Med 11: 1096–1103, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spinale FG. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulation and dysregulation in the failing heart. Circ Res 90: 520–530, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev 85: 1093–1129, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura T, Furukawa Y, Taniguchi R, Sato Y, Ono K, Horiuchi H, Nakagawa Y, Kita T, Kimura T. Serum adiponectin level as an independent predictor of mortality in patients with congestive heart failure. Circ J 71: 623–630, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, Yamashita S, Noda M, Kita S, Ueki K, Eto K, Akanuma Y, Froguel P, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Carling D, Kimura S, Nagai R, Kahn BB, Kadowaki T. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med 8: 1288–1295, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.