Abstract

Activation of phospholipases leads to the release of arachidonic acid and lysophospholipids that play prominent roles in regulating vasomotor tone. To identify the role of calcium-independent phospholipase A2β (iPLA2β) in vasomotor function, we measured vascular responses to phenylephrine (PE) and ACh in mesenteric arterioles from wild-type (WT; iPLA2β+/+) mice and those lacking the β-isoform (iPLA2β−/−) both ex vivo and in vivo. Vessels isolated from iPLA2β−/− mice demonstrated increased constriction to PE, despite lower basal smooth muscle calcium levels, and decreased vasodilation to ACh compared with iPLA2β+/+ mice. PE constriction resulted in initial intracellular calcium release with subsequent steady-state constriction that depended on extracellular calcium influx. Endothelial denudation had no effect on vessel tone or PE-induced constriction although the dilation to ACh was significantly reduced in iPLA2β+/+ vessels. In contrast, vessels from iPLA2β−/− constricted by 54% after denudation, indicating smooth muscle hypercontractility. In vivo, blood pressure, resting vessel diameter, and constriction of mesenteric vessels to PE were not different in iPLA2β−/− vessels compared with WT mouse vessels. However, relaxation after ACh administration in situ was attenuated, indicating an endothelial inability to induce dilation in response to ACh. In cultured endothelial cells, inhibition of iPLA2β with (S)-(E)-6-(bromomethylene)tetrahydro-3-(1-naphthalenyl)-2H-pyran-2-one (BEL) decreased endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation and reduced endothelial agonist-induced intracellular calcium release as well as extracellular calcium influx. We conclude that iPLA2β is an important mediator of vascular relaxation and intracellular calcium homeostasis in both smooth muscle and endothelial cells and that ablation of iPLA2β causes agonist-induced smooth muscle hypercontractility and reduced agonist-induced endothelial dilation.

Keywords: vascular smooth muscle, vascular endothelium, calcium signaling, 12- hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, lysophosphatidylcholine

the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying hypertension and vascular complications of diabetes relate, in part, to the impaired relaxation of vascular smooth muscle. For instance, ACh-induced mouse or rat mesenteric vessel dilation is reduced in conditions of oxidative stress, diabetes, or hypertension (11, 19, 23, 24). ACh-mediated endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation has been attributed primarily to the activation of endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) and the formation of NO to relax smooth muscle cells. In rodent mesenteric vessels NO contributes 50% to 80% of the ACh-mediated dilatory response (4, 23, 24, 33). However, a substantial portion of the vasodilatory response to ACh cannot be accounted for by NO alone and has previously been demonstrated to result from the action(s) of an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) (23, 31). Although the precise chemical identity of EDHF is unknown, substantial evidence indicates that it is an oxygenated eicosanoid metabolite, such as epoxyeicosatrienoic acid, which is formed by a cytochrome P-450 mono-oxygenase following the release of arachidonic acid (AA) from its endogenous storage pools. Thus EDHF could also cause endothelial membrane hyperpolarization, which spreads to adjacent smooth muscle cells via heterocellular gap junctions to cause further vessel relaxation (9). Importantly, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids have been shown to induce vasodilation in rat mesenteric vessels (4, 31) in the absence of alterations in NO. The strongest evidence for the importance of NO-independent effects in vascular relaxation is that mice deficient in eNOS still exhibit ACh-mediated vasodilatation (38).

The majority of arachidonic acid released in endothelial cells is mediated by intracellular PLAs2, which catalyze the hydrolysis of fatty acid substituents, e.g., arachidonic acid, from glycerophospholipid substrates (25, 40). Although both Ca2+-dependent PLA2 (cPLA2) and Ca2+-independent PLA2 (iPLA2) forms of the enzyme are present in mammalian cells (34), the predominant activity in endothelium is derived from iPLA2 (25) and is sensitive to inhibition by (E)-6-(bromomethylene)tetrahydro-3-(1-naphthalenyl)-2H-pyran-2-one (BEL) (20). iPLA2 activities are broadly distributed in mammalian tissues (22), and nine members of the iPLA2 family have been identified. This family of enzymes is defined by the presence of a patatin-like homology domain (20 kDa), which contains consensus sequences for a nucleotide binding fold (GXGXXG) and a serine α/β-hydrolase motif (GXSXG) (21). These enzymes are classified as PNPLA1–9 (HUGO nomenclature), reflecting the nine genes encoding this family of proteins in the human genome.

In vascular smooth muscle cells, iPLA2 contributes to the regulation of calcium homeostasis. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates iPLA2β (20, 35, 39), which activates store-operated channels that facilitate calcium influx resulting in smooth muscle contraction (30). Recently, we reported that the iPLA2-generated arachidonic acid was essential to vasodilation resulting from application of ACh to rat mesenteric arteries in vitro (33), although iPLA2 did not appear to contribute to purine-induced dilation of rat middle cerebral arteries (41). In addition, calcium-independent isoforms of PLA2 were found to regulate calcium entry in aortic endothelial cells (5). To further clarify the action of iPLA2β in vascular contraction and relaxation in resistance vessels, we generated mice null for iPLA2β (iPLA2β−/−) by homologous recombination (2, 3). The goals of the present study were to determine whether genetic ablation of iPLA2β attenuates phenylephrine (PE)-induced constriction and ACh-mediated relaxation in resistance vessels. Using a well-accepted ex vivo assay of vascular reactivity in isolated mesenteric arterioles together with in vivo assessment of vascular relaxation, we demonstrated an important role for iPLA2β in rendering vascular smooth muscle from iPLA2β−/− animals hypercontractile, despite lower calcium levels in these cells. In addition, vessels from these animals exhibited reduced endothelium-dependent agonist-induced relaxation likely due to reduced eNOS phosphorylation and agonist-induced calcium influx into the endothelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of mice and pressurized vessels.

All protocols were approved by the Animal Studies Committee at Washington University. Mice homozygous for disruption of the iPLA2β allele (iPLA2β−/−) were generated as described previously and established in a C57/BL6 background (2, 3). Animals were genotyped as described previously (2, 3). Male knockout mice over 12 wk of age (25–35 g) and age-matched wild-type controls (iPLA2β+/+) were anesthetized with ketamine (87 mg/kg ip) and xylazine (13 mg/kg ip). The abdomen was shaved and incised in the midline to access the small intestine. A 5- to 7-cm loop of the jejunum was withdrawn from the incision into a petri dish and kept moist with saline. Adipose and loose connective tissues were carefully removed from two to three second or third order mesenteric arterioles with the aid of a dissecting microscope. For ex vivo analysis of vascular reactivity, 2- to 3-mm lengths of the exposed vessels without branches were excised and transferred to a petri dish with 2.0 mmol/l MOPS buffer containing 10% wt/vol of dialyzed bovine serum albumin and (in mmol/l) 144 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.5 MgSO4, 2.0 pyruvate, 5.0 glucose, 0.02 ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 1.21 NaH2PO4 at 20°C. The mouse was then euthanized by anesthetic overdose. For in vivo video-microscopic imaging of the mesenteric vessels, the mouse was placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot 300; Nikon, Melville, NY) in a U-shaped piece of malleable lead covered with an insulated heating pad. Rectal body temperature was monitored and maintained near 37°C by adjustments in the heating pad temperature. The mesentery with exposed vessels was draped over a 4-mm high clear plexiglass rod mounted in the center of a plexiglass plate positioned over the microscope objective (40×) that permitted observation of the vessels as well as superfusion of the area and collection of the drained solution by suction. A 26-gauge catheter (Venisystems Abbocath-T; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) was inserted into an exposed jugular vein, and patency was maintained by periodic flushes with warmed saline.

Diameter measurements of excised mesenteric vessels.

Excised mesenteric arterioles from either wild-type or iPLA2β knockout mice were transferred in MOPS buffer to an organ bath (2.5 ml volume) mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert S100TV; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). The vessel was cannulated on one side with a perfusion pipette and occluded on the other side with a collecting pipette (17). No luminal flow was allowed in the experiment. The vessels were observed with a video camera system (MTI CCD-72; Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN), and the video images were recorded on digital video tape. Diameter measurements were made in response to agonists added to the bath (17). Briefly, the internal diameters were measured online at 60 mmHg and 37°C with a computerized diameter tracking system (sampling rate of 10 Hz; Diamtrak 3 Plus; Montech, Melbourne, Australia) that also stored the digital still images for analysis. After a 20-min equilibration period, the vessel diameter was measured and the bath solution was replaced with warmed MOPS buffer containing freshly dissolved PE (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) titrated to induce maximal constriction. Preliminary data showed maximal constriction with 100 μmol/l PE, which was then used in all subsequent experiments. Since mesenteric vessels of this caliber do not develop spontaneous tone (38), we used the PE stimulation as an indicator of viability and discarded vessels that yielded <20% change in diameter. The diameter of the arteriole was measured after both maximal and steady-state constriction with PE (within 2 min) after which the bath solution was changed to MOPS buffer containing 100 μmol/l PE plus 0.1 μmol/l ACh (Sigma). After relaxation of the vessel to a new steady state, the diameter was measured and the bath solution exchanged with MOPS buffer containing 100 μmol/l PE and 1.0 μmol/l ACh. The steady-state diameter was then measured again. The bath solution was changed to MOPS buffer alone to achieve baseline relaxation to the original (pre-PE) vessel diameter. In wild-type vessels, the experiment was then repeated with buffers containing the mechanism-based inhibitor of iPLA2 BEL (10 μmol/l). In preliminary experiments, we confirmed that the BEL vehicle (ethanol, 0.1%) had no effect on vessel responses. In a subset of experiments, we tested the capacity of the vessels to constrict to a depolarizing stimulus by exposing vessels from both wild-type and iPLA2β knockout mice to MOPS buffer containing 40 mmol/l potassium chloride.

Measurement of intracellular calcium in arteriolar smooth muscle cells.

Isolated and cannulated vessels from either wild-type or iPLA2β knockout mice were loaded extraluminally with the Ca2+-sensitive dye fura-2 according to methods reported previously (8). Briefly, fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester (50 μg of fura-2 AM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was predissolved in 10 μl of dry DMSO containing 20% of Pluronic (Molecular Probes) as a dispersing agent diluted to 100 μl with distilled H2O and then to a final volume of 10 ml with MOPS buffer (5 μmol/l fura-2 AM final concentration). The vessels were incubated with the fura-2 AM solution for 15 min at 37°C in the dark, followed by washing and equilibration with MOPS buffer for 20 min. Light emissions following excitation at 340 and 380 nm (sampling rate of 10 Hz) were compared ratiometrically following application of 100 μmol/l PE, PE plus 10 μmol/l ACh, and after washout with MOPS buffer using a photon multiplier-based detection system (C&L Instruments, Hershey, PA). Simultaneous video measurements of vessel diameters were made utilizing a 730-nm laser and a Diamtrak system. Estimates of the intracellular calcium levels were determined after system calibration as described previously (8, 13). Extraluminal fura-2 application has been reported to specifically load the smooth muscle cells with the endothelium not contributing to the fura-2 signal (10, 26). To confirm this in our preparation, in some vessels we measured the fura-2 ratio before and after endothelial denudation via air embolus as described previously (18). In PE preconstricted vessels endothelial denudation reduced the dilatory response to ACh (10 μmol/l) by 74% in wild-type vessels (P < 0.05, n = 3), indicating successful endothelial impairment. However, the fura-2 signal was unchanged after denudation (wild-type vessels, ratio 0.71 ± 0.06 before and 0.69 ± 0.06 after embolus, n = 4; iPLA2β knockout vessels, ratio 0.53 ± 0.02 before and 0.52 ± 0.01 after embolus), confirming that the endothelium did not contribute to the fura-2 signal.

Videomicroscopic imaging of in vivo mesenteric vessels.

The mesenteric arcade was superfused with 10 mmol/l HEPES buffer containing (in mmol/l) 135 NaCl, 2.6 NaHCO3, 0.34 Na2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 5 KCL, 1.4 CaCl2, 1.17 MgSO4, 0.025 EDTA, and 5.5 glucose at pH 7.35–7.4. The solution was pumped (Masterflex Cartridge Pump Model 7519-20; Cole Palmer, Vernon Hills, IL) at 0.75 ml/min through an oxygenator composed of 25 m of thin-walled silicone tubing in a flask gassed with 95%O2-5% CO2. The solution was heated to 37°C (Radnoti heat exchanger; Radnoti, Monrovia, CA) before being dripped on the exposed vessels. One of the dissected vessels was located at 40× magnification with a digital camera (Nikon Coolpix 5000, maximum zoom) attached to a color monitor (Sony PVM-1342Q; Sony, San Diego, CA). A baseline image of the vessel was then saved for analysis of the inner diameter. The superfusate buffer was switched to HEPES buffer containing fresh 100 μmol/l PE (shown to yield maximal constriction in preliminary studies), and an image of the constricted vessel was saved after 5 min. Superfusion with PE was continued, and 16 μmol/l ACh in buffer (0.2 ml) was injected into the jugular venous catheter. Preliminary studies showed that bolus injection of 16 μmol/l ACh induced relaxation of the mesenteric arterioles without affecting heart function (as determined by measuring heart rate from the surface ECG). Images of the vessel were saved every 30 s for 5 min after injection of ACh. The vessel was then superfused with buffer alone for at least 4 min to restore the original diameter before moving to another vessel to repeat the process. Images stored in the digital camera were uploaded to a personal computer containing Jasc Paintshop Pro 6.0 software (Corel; Ottawa, ON, Canada). With the use of the 40× image micrometer scale, the pixel coordinates provided by Paintshop were expressed as a pixel-to-micron ratio that was used to analyze vessel images. The distance between points (X,Y) on the opposite edges of the vessel were calculated in pixels with use of the Pythagorean theorem: pixel distance = [(X2-X1)2 + (Y2-Y1)2]0.5. The resulting distance was multiplied by the pixel-to-micron ratio to yield the diameter of the vessel in microns.

Measurements of blood pressure.

In a separate set of experiments, blood pressure was measured in intact animals anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane in oxygen since this anesthetic causes minimal cardiac depression in mice. A 1.4-F catheter pressure probe (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was passed into the ascending aorta via a cutdown of the right common carotid artery. Mean arterial blood pressure and heart rate were recorded with use of a Powerlab/4sp data acquisition system (ADInstuments, New Castle, Australia).

Determination of iPLA2β mRNA levels.

Tissue-specific expression of iPLA2β was analyzed using RT-PCR as described previously (3). Briefly, PCR conditions typically employed a 30-cycle reaction with steps at 53°C for 30 s, 72°C for 2 min, and 94°C for 30 s per cycle. PCR products were resolved by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The following primer sets were utilized for amplification from cDNA encoding iPLA2β: OF, 5′-CTGCAGAATTCCATGTCGAAAGATAACATGGAG-3′; OR, 5′-CCGAAGCGGCCGCTCCTTCATACGGAAGTACAC-3′; FF, 5′-ATGATTATCAGCATGGACAGCA-3′; R, 5′-ACACAGGTTACAGGCACTTGAGG-3′. Primer sets were utilized to amplify PCR products from iPLA2β+/+ heart and mesentery cDNA.

Cell culture of endothelial cells.

EA.hy 926 endothelial cells derived from human umbilical vein endothelium were kindly provided by Dr. Cora-Jean S. Edgell (Pathology Department, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). Cell cultures were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 100 U/ml benzylpenicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, HT supplement (100 μmol/l hypoxanthine, 16 μmol/l thymidine) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. These cells were seeded, grown in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C to confluence, subcultured routinely using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA, and used for experiments within nine passages.

Fluorometric determination of nitric oxide.

Confluent cells in 6-mm tissue culture dishes were washed twice with HBSS supplemented with 0.35 g/l NaHCO3, 1.8 mmol/l CaCl2, 100 μmol/l L-arginine, and 0.8 mmol/l MgSO4 (pH 7.4) and were preincubated in the same buffer for 4 h to allow cells to become quiescent. The buffer solution was then aspirated, and the cells were incubated for 10 min in fresh HBSS in the presence or absence of agonists. For iPLA2 inhibition experiments, cells were pretreated with the indicated concentration of BEL [racemic-, (R)- or (S)-BEL] or ethanol vehicle alone (<0.1% vol/vol in final concentration) for 10 min at 37°C and the buffer solution was replaced at the time of agonist stimulation. Racemic BEL is a generic inhibitor of iPLA2, (S)-BEL is a specific inhibitor for the iPLA2β, and (R)-BEL for the iPLA2γ isoform (20).

After stimulation with 100 μmol/l ATP, the supernatants were collected for spectrofluorometric quantification of NO release. The NO assay was done according to the manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Briefly, aliquots (80 μl) of the collected supernatants were placed in a white 96-well microplate. Ten microliters of nitrate reductase solution and 10 μl of cofactor solution were prepared and added to each well for conversion of nitrate (NO3−) into nitrite (NO2−). After a 2-h incubation at room temperature, samples were further incubated for 40 min in the presence of the fluorescent probe 2,3-diaminonaphthalene (Cayman Chemical, used as provided by the manufacturer). To terminate the reaction and enhance fluorometric sensitivity, 10 μl of 2.8 mol/l NaOH was added and the fluorescence of each well was then measured at room temperature using a Spectra Max Gemini XS spectrofluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) with 365 nm excitation and 450 nm emission wavelengths.

Intracellular calcium measurements in endothelial cells.

Similar to the vessel experiments, intracellular calcium concentrations were measured in cultured endothelial cells using fura-2 AM. Confluent cells were split 1:4 onto Delta TPG dishes (0.17 mm thick; Bioptechs, Butler, PA) and grown for 24 h. After cells were washed with HBSS twice, they were incubated for 90 min in the dark in HBSS (pH 7.4) containing 5 μmol/l fura-2 AM [predissolved in DMSO containing F-127 Pluronic (0.02% final concentration)]. The cells were washed again to remove unincorporated fura-2 AM. For BEL inhibition experiments, cells were incubated in HBSS containing the indicated concentrations of BEL or ethanol vehicle (0.1% vol/vol) alone for 15 min. After excess BEL was washed away, fresh buffer solution (including 200 μmol/l EGTA for Ca2+-free media) was placed into the dishes, followed by a 10-min preincubation period before fluorescence measurements. The dishes were mounted on the stage of a Zeiss inverted digital microscope (40×) and cells were illuminated alternatively with 340 nm/380 nm light for excitation, and data were collected at 510 nm as the fixed emission wavelength. The concentration of intracellular Ca2+ was calculated based upon the fluorescence intensity ratio (Ratio F340/F380). Image data were analyzed by using Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). Chemicals used were racBEL, (S)-, (R)-BEL (10 μmol/l), AAME (20 μmol/l), 1-palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC, 10 μmol/l), 12-hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (12-HETE, 4 μmol/l), ATP 100 μmol/l, 5,8,11,14-eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA, 20 μmol/l, a nonmetabolizable analog of AA, which blocks cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, and cytochrome P-450 epoxygenase pathways), 17-octadecynoic acid (17-ODYA; 10 μmol/l, a cytochrome P-450 epoxygenase and ω-hydroxylase inhibitor), ibuprofen (20 μmol/l, a cyclooxygenase inhibitor), and nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA; 20 μmol/l, a lipoxygenase inhibitor).

eNOS phosphorylation Western blotting analysis.

EA.hy 926 cells utilized for Western blotting were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 500 μl of 50 mmol/l Tris, pH 7.4, containing 150 mmol/l NaCl, 1 mmol/l EDTA, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 1 mmol/l phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin. Protein concentration was determined with a Bio-Rad protein assay utilizing bovine serum albumin as standard. Western blotting with an antibody against phospho-eNOS at Ser1177 was performed following the manufacturer's protocol (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) using 7% SDS-PAGE gels with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated protein A for detection by enhanced chemiluminescence. Phospho-eNOS at Ser1177 was detected at ∼130 kDa.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. N indicates the number of animals, with one or two vessels per animal studied for ex vivo and two or three vessels studied per animal for in vivo experiments. Results from multiple vessels were averaged. Differences between means were determined using the paired or unpaired Student's t-test as appropriate. Differences in responses to agonists and inhibitors between knockout and wild-type animals were determined by ANOVA or repeated-measures ANOVA as appropriate. For nonparametric evaluation we used the Mann-Whitney test. For cell culture experiments, only one treatment was applied per culture. Results from multiple cultures were averaged, and the effects of agonists and antagonists on calcium responses were determined by Student's t-test. A level of P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of iPLA2β expression.

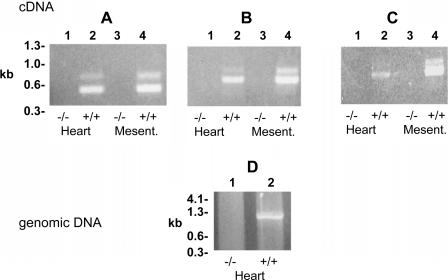

The presence of iPLA2β in the mesenteric arteries under study in iPLA2β+/+ animals was confirmed by RT-PCR. As anticipated, genetic ablation of iPLA2β by homologous recombination resulted in the complete absence of iPLA2β message in the mesenteric vessels (Fig. 1) as well as in all other tissues examined previously (2, 3).

Fig. 1.

PCR amplification of calcium-independent phospholipase A2β (iPLA2β) message from iPLA2β−/− and iPLA2β+/+ mouse tissues. Three primer pair sets (see materials and methods) were utilized to amplify iPLA2β message from cDNA libraries from heart (lanes 1 and 2) and mesenteric arterioles (Mesent lanes 3 and 4). A: OF and OR amplified a 431 nt product. B: RR and OR amplified a 683 nt product. C: OF and R amplified an 898 nt product. D: PCR amplification of iPLA2β genomic DNA utilizing primers 5′-TCAGCAGCATTGCTCTACAGACCA-3′ and 5′-CAGGCTCCAAAGACTTGGGTCTCG-3′ to amplify a 978 nt in iPLA2β+/+ (lane 2) but not iPLA2β−/− mice (lane 1).

Vascular responses of mesenteric vessels to PE and ACh using pressurized ex vivo preparations.

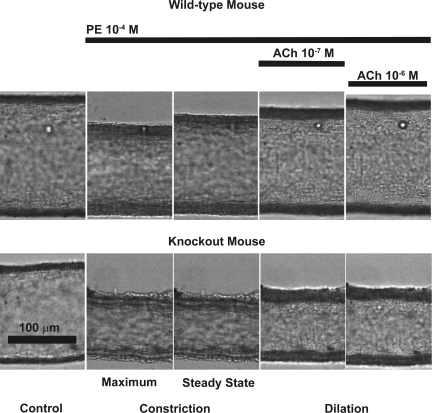

After anesthesia, mesenteric vessels were harvested and subjected to analysis using quantitative video microscopy. First, the effects of PE-mediated constriction and ACh-induced dilation of mesenteric vessels from iPLA2β+/+ and iPLA2β−/− mice were examined. Examples of the vasomotor responses and representative traces of diameter changes are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, A and B, respectively. Vessels isolated from iPLA2β−/− mice had an average diameter of 168 ± 28 μm (n = 5) that was not different from the diameter of vessels from wild-type animals (165 ± 4 μm, n = 5; Mann-Whitney test). Vessels from both groups of mice constricted significantly to PE (100 μmol/l). However, vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice showed significantly higher maximal and steady-state constriction responses to PE than wild-type vessels (48 ± 11 vs. 83 ± 4 μm and 48 ± 9 vs. 91 ± 7 μm, respectively). Addition of ACh 10−5 mol/l dilated wild-type vessels but had no significant effect on vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice. Replacing the PE containing buffer with MOPS buffer resulted in all examined vessels returning to their baseline diameters. To elucidate the contribution of the endothelium to the diameter responses, we denuded an additional three vessels each from wild-type and iPLA2β−/− animals. Denudation did not affect the resting diameter of wild-type vessels (240 ± 11 vs. 240 ± 10 μm). Constriction to PE (100 μmol/l) was not significantly enhanced (101 ± 12 vs. 84 ± 7 μm), but the dilation to ACh (10 μmol/l) was reduced by 74% (P < 0.05, paired t-test), indicating endothelial damage. Vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice, however, constricted from 234 ± 27 to 111 ± 13 μm (P < 0.05, paired t-test) following denudation. In preliminary experiments, we also tested 100 μmol/l PE, which enhanced the vessel constriction (average 123 vs. 54 μm), whereas addition of ACh (10 μmol/l) did not change the diameter (average 55 μm).

Fig. 2.

Video microscopic images demonstrating typical responses of mesenteric arterioles from wild-type and iPLA2β−/− (knockout) mice to phenylephrine (PE) and ACh. Isolated mesenteric vessels were pressurized as described in materials and methods. The mesenteric arteriole isolated from iPLA2β−/− mouse shows enhanced constriction to PE (100 μmol/l) and reduced dilation to ACh (0.1 and 1 μmol/l) compared with a vessel isolated from a wild-type animal, which fully dilates in response to the same concentration of ACh.

Fig. 3.

Differences in calcium signaling and vascular tone of pressurized wild-type (WT) and iPLA2β knockout (KO) mesenteric arterioles stimulated with PE and ACh. Changes in intracellular calcium concentration (measured as the ratio of the fura-2 fluorescence at 340/380 nm) and vessel diameter were determined as described in materials and methods. A and B: representative tracings of fura-2 calcium fluorescence ratios (upper trace, left axis) and diameter changes (lower trace, right axis) for a WT (A) and a KO (B) vessel. C: absolute vessel diameter responses and calcium ratios in all vessels from WT (n = 5) and KO (n = 5) mice indicate that maximum (Max) and steady-state constriction responses to PE (100 μmol/l) were significant (‡P < 0.05 from respective control, ANOVA) with the constriction significantly enhanced in KO vessels compared with WT (*P < 0.05, ANOVA). The basal control fura-2 calcium ratio was significantly lower in KO vessels compared with WT control (†P < 0.05). Vessels from KO mice did not dilate in response to ACh [10 μmol/l; not significant (NS)] in contrast with normal vessel dilation in WT controls (¶P < 0.05 between steady-state diameter and ACh diameter). In addition, dilation of WT vessel coincided with a decrease in the calcium ratio (¶), whereas the calcium ratio in KO vessels was not significant (NS). D: although most relative diameter and calcium responses reflect the absolute values, the initial relative calcium response was much higher in KO vessels (§P < 0.05).

Vessels from wild-type and iPLA2β−/− mice similarly constricted to depolarizing potassium chloride (40 mmol/l). The vessel from the wild-type mice decreased their diameter from 212 ± 2 to 128 ± 2 μm, a decrease of 60 ± 2% (n = 3) with vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice constricting from a diameter of 196 ± 1 μm before to 121 ± 1 μm in response to depolarization, a decrease of 64 ± 2% (n = 3).

Ratiometric calcium measurements in isolated vessels.

To determine the role of intracellular free calcium in mediating the observed effects, concomitant measurements of vessel diameter and intracellular calcium ratios were made in vessels from iPLA2β+/+ and iPLA2β−/− animals. Vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice had a significantly lower basal fluorescence ratio (R = 0.47 ± 0.02 or 41 nmol/l Ca2+) compared with vessels from wild-type mice (0.80 ± 0.01 or 172 nmol/l Ca2+), indicating a lower calcium level in mesenteric vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice. Mesenteric arterioles isolated from iPLA2β−/− animals demonstrated an increase in intracellular calcium after addition of 100 μmol/l PE (R = 0.80 ± 0.23 or 172 nmol/l Ca2+) that coincided with vessel constriction of the vessel. Vessels from iPLA2β+/+ animals also showed an increase in calcium fluorescence ratio (1.17 ± 0.03 or 355 nmol/l Ca2+) consistent with constriction. Although the absolute increase in the calcium fluorescence ratio was similar (ΔR = 0.36 for wild-type vessels and ΔR = 0.34 for iPLA2β−/−), vessels from iPLA2β−/− animals demonstrated substantially greater vasoconstriction. In both iPLA2β+/+ and iPLA2β−/− vessels, the fluorescence ratio decreased after an initial peak, which coincided with reaching an increased steady-state diameter in wild-type vessels. However, the diameter in iPLA2β−/− vessels did not increase even after the decrease in fluorescence ratio. Addition of ACh 10−5 mol/l significantly dilated the wild-type vessels coincident with a significant decrease in calcium level. In stark contrast, addition of ACh did not dilate vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice or decrease their calcium fluorescence ratio.

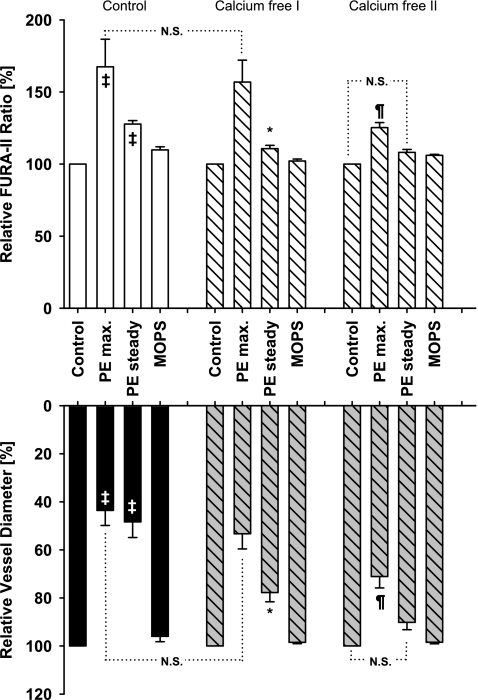

Comparisons between the PE responses of iPLA2β+/+ and iPLA2β−/− vessels demonstrated that the relative increase of the calcium fluorescence ratio was higher in iPLA2β−/− vessels (169 ± 16%) compared with iPLA2β+/+ vessels (145 ± 5%; P < 0.05). In seven vessels from iPLA2β−/− animals, the calcium containing MOPS buffer was replaced with calcium free buffer by replacing the calcium chloride with equimolar sodium chloride. After 10 min of incubation, the PE stimulation (PE dissolved in Ca2+-free MOPS) was repeated. Despite removal of the extracellular calcium, PE stimulation resulted in an initial constriction and a simultaneous Ca2+-signal increase, which was not different from that observed in the calcium control, suggesting the release of intracellular calcium. This constriction was followed by a rapid relaxation and decrease in calcium level with the steady-state constriction greatly reduced compared with calcium control, indicating that the steady-state constriction is depending upon the influx of extracellular calcium. A second PE stimulation further reduced the initial PE-induced constriction and calcium level, indicating that intracellular calcium stores had been greatly depleted. Furthermore, within seconds, the vessels returned to a steady-state diameter that was not different from their control diameter. We repeated this experiment in four vessels from wild-type animals (diameter of 215 ± 24 μm) and found that the decreases in diameter and calcium responses paralleled those observed in iPLA2β−/− vessels (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicate the participation of both intracellular and extracellular calcium in facilitating calcium-mediated, agonist-induced contraction. In particular, sustained contraction requires a stimulus-mediated sustained influx of extracellular calcium. Moreover, a second stimulation with PE reduced both the initial and steady-state vasoconstriction, in parallel with the calcium signal, which would suggest that the initial PE response relies predominantly on calcium release from intracellular, depletable stores, whereas the steady-state constriction largely depends on the influx of extracellular calcium (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of extracellular calcium ion removal on PE-induced constriction. In calcium containing buffer (control), vessels from iPLA2β knockout mice constricted significantly to extraluminal PE (100 μ mol/l) concurrent with a significant increase in calcium levels (‡P < 0.05 from respective controls, ANOVA; n = 7). Calcium removal strongly attenuated steady-state constriction (calcium free I; *P < 0.05, ANOVA), but not initial maximum constriction (NS) or initial calcium response (NS) compared with calcium control consistent with the initial constriction dependent on intracellular calcium release and the steady-state constriction on extracellular calcium influx. A second stimulation with PE (calcium free II) greatly diminished the initial maximum constriction (¶) and calcium response (¶), indicating that intracellular calcium stores have been depleted (calcium free 2, right). Furthermore, the vessel dilated within seconds with the diameter and the calcium level no longer different from calcium free II control (NS).

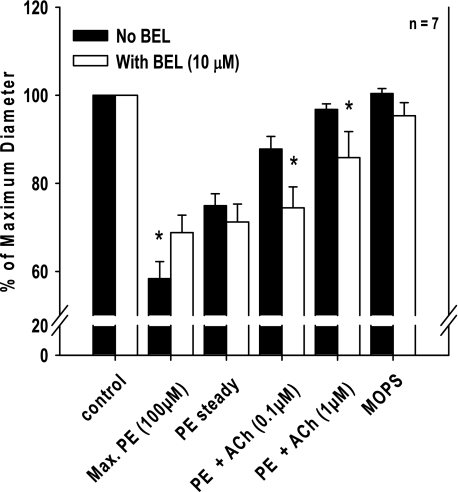

Inhibition of iPLA2β with BEL attenuates PE-mediated vasoconstriction and ACh-mediated vasorelaxation.

The baseline diameter of iPLA2β+/+ vessels was 181 ± 8 μm (n = 7) and was not significantly changed after treatment with BEL (184 ± 9 μm). Application of 100 μmol/l PE resulted in a marked constriction of the mesenteric vessels (106 ± 8 μm or 58% of control diameter) that was significantly attenuated in the presence of BEL (125 ± 6 μm or 68% of control diameter; Fig. 5). However, a spontaneous, partial relaxation to a steady-state constriction during continued exposure to PE was not different either before (136 ± 6 μm) or after (129 ± 4 μm) BEL treatment. Moreover, application of increasing doses of ACh to the constricted vessels induced a nearly complete relaxation response for untreated iPLA2β+/+ vessels with diameters returning to 176 ± 7 μm (97% of control diameter), but only resulted in partial relaxation to 157 ± 9 μm (85% of control diameter; P < 0.05 vs. control) for BEL-treated vessels. Replacement of the PE-containing buffer with MOPS buffer resulted in complete relaxation to control diameters in all examined vessels (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of (E)-6-(bromomethylene)tetrahydro-3-(1-naphthalenyl)-2H-pyran-2-one (BEL) on PE-induced constriction and dilation of mesenteric arterioles in response to ACh. After PE (100 μmol/l) preconstriction and application of ACh (0.1 and 1 μmol/l), pressurized vessels isolated from wild-type mice were treated with BEL and the PE and ACh stimulation repeated. BEL (10 μmol/l) significantly reduced the maximum constriction response to PE but had no effect on the steady-state constriction. However, BEL significantly reduced the dilation responses to ACh (0.1 and 1 μmol/l). *P < 0.05 between control (n = 7, repeated-measures ANOVA).

Vascular responses to agonists in vivo and arterial blood pressure measurements.

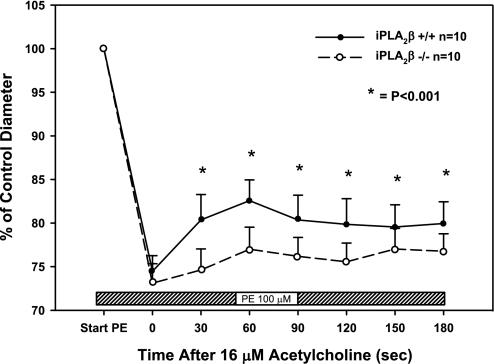

To confirm the importance of these results in intact animals, intravital microscopy was performed on mesenteric vessels from iPLA2β+/+ and iPLA2β−/− mice. Similar results to those obtained with excised vessels were observed during contraction and relaxation of mesenteric arteries in vivo. Application of 100 μmol/l PE to the surface of the mesentery led to a 25% reduction in diameter for iPLA2β+/+ vessels (180 ± 5 to 135 ± 5 μm; n = 10) and a 27% reduction in diameter for iPLA2β−/− vessels (170 ± 5 to 125 ± 6 μm; n = 10) with the average control diameters not different (unpaired t-test; Fig. 6). However, although intravenous injection of 16 μmol/l ACh induced 11 ± 2% relaxation over 60 s in vessels from iPLA2β+/+ animals, only 5 ± 2% relaxation occurred in vessels from iPLA2β−/− animals (P < 0.05 vs. iPLA2β+/+; Fig. 6), indicating reduced endothelium-dependent dilation. Aortic blood pressure was not significantly different between wild-type and knockout animals averaging 76.5 ± 4.7 mmHg in iPLA2β+/+ wild-type and 78.6 ± 4.6 mmHg in iPLA2β−/− mice (n = 6 in each group).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of vasomotor responses in mesenteric arterioles of wild-type and iPLA2β knockout mice in vivo. Arteriolar diameters were measured using video microscopy. Superfusion with PE (100 μmol/l) constricted the vessels similarly in both wild-type (n = 10) and iPLA2β−/− (n = 10) mice. An intravenous bolus injection of ACh (16 μmol/l) dilated the wild-type vessels more than the knockout vessels, indicating that the in vivo vasodilatory response to ACh is attenuated in mice null for iPLA2β. *P < 0.001 between groups by repeated-measures ANOVA.

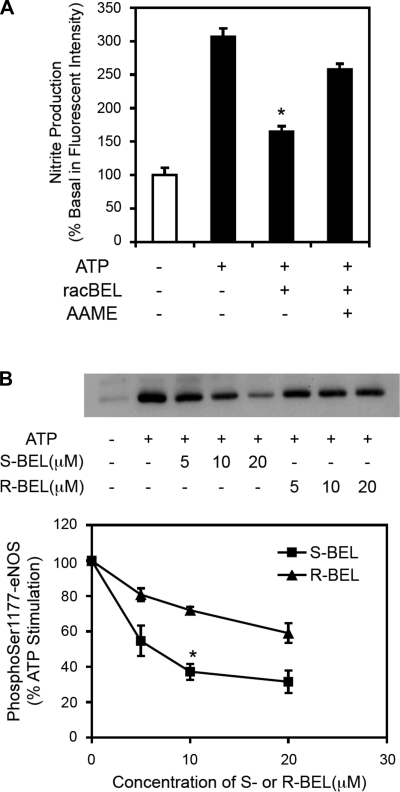

Inhibition of endothelial NO production and eNOS phosphorylation by BEL.

To further elucidate the contribution of iPLA2β on vascular regulation and its possible contribution to endothelial function, we studied the effect of iPLA2β inhibition in cultured endothelial cells. As shown in Fig. 7A, inhibition of iPLA2β with racemic BEL (5 μmol/l) caused a significant decrease in nitrite production that was partially restored by adding the membrane permeable arachidonic acid analog arachidonyl methyl ester (AAME; 20 μmol/l) as substrate. These results indicate that arachidonic acid produced by iPLA2β contributes to NO production in endothelial cells. Since phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 regulates eNOS activity (27) we measured the phosphorylation state of eNOS by Western blot using an antibody against phospho-Ser1177. The iPLA2β-enantioselective mechanism-based inhibitor (S)-BEL reduced phosphorylation at Ser1177 by more than 50% (Fig. 7B), indicating that iPLA2β activity contributes to the activation of eNOS.

Fig. 7.

Effects of BEL and analog arachidonyl methyl ester (AAME) on ATP-stimulated nitric oxide (NO) production and endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) phosphorylation in endothelial cells. Cultured EA.hy926 endothelial cells were stimulated with ATP (100 μmol/l) and iPLA2β was inhibited by either racemic BEL (racBEL) or the (S) and (R) enantiomers of BEL. A: RacBEL (5 μmol/l) significantly inhibited NO production (measured as nitrite) that was partially restored by administration of AAME (20 μmol/l). *P < 0.01 compared with ATP-stimulated controls (n = 3). B: representative Western blot of eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 (top) with the corresponding quantification of the density data (bottom) demonstrating that (S)-BEL (5 μmol/l, specific for iPLA2β), but not (R)-BEL (5 μmol/l), dose-dependently reduced eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177. These results indicate that iPLA2β contributes to agonist-stimulated NO production by regulating eNOS phosphorylation. *P < 0.01 compared with ATP-stimulated controls (n = 3).

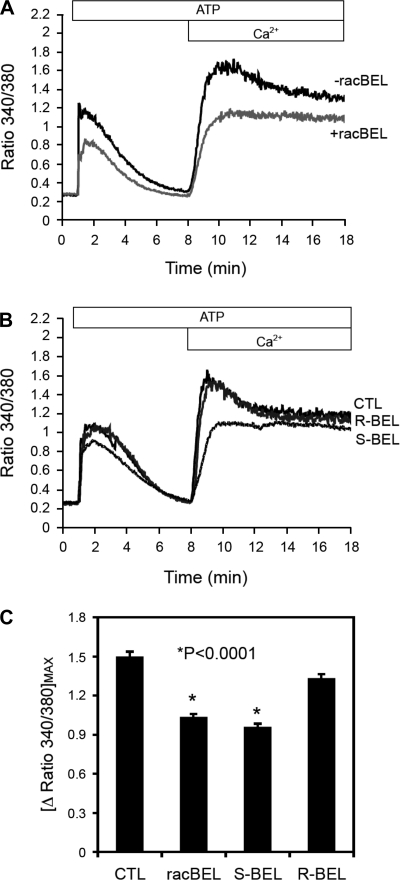

Endothelial iPLA2β mediated calcium responses in cultured cells.

Similar to the vessel experiments, agonist-induced calcium increases consisted of both intracellular calcium release and extracellular calcium influx (Fig. 8A). Inhibition with racemic BEL (10 μmol/l) reduced and delayed endothelial calcium response similar to the specific inhibition of iPLA2β with (S)-BEL (10 μmol/l; Fig. 8B), indicating that iPLA2β reaction products and/or their downstream metabolites likely contribute to agonist-induced intracellular calcium release and extracellular calcium influx.

Fig. 8.

Effect of BEL on calcium signaling as measured by fura-2 fluorescence ratio (340 nm to 380 nm) in endothelial cells. Cultured EA.hy926 endothelial cells were pretreated with either racemic BEL (racBEL) or its enantiomers (S)-BEL or (R)-BEL before stimulation with ATP (100 μmol/l). A: representative experiment showing that racBEL reduced and delayed (note rightward-shift of the curve rise and peak amplitude) ATP-induced intracellular calcium release and extracellular calcium influx. B: representative experiment showing that the ATP-induced calcium response was inhibited by (S)-BEL (a specific inhibitor for iPLA2β) but not R-BEL, indicating participation of iPLA2β products in agonist-induced calcium signaling. C: composite data from n ≥ 4 experiments showing decreased calcium flux with racemic BEL and (S)-BEL but not (R)-BEL. These data indicate that iPLA2β contributes to the regulation of agonist-induced intracellular calcium release and extracellular calcium influx. *P < 0.0001 compared with ATP-stimulated controls.

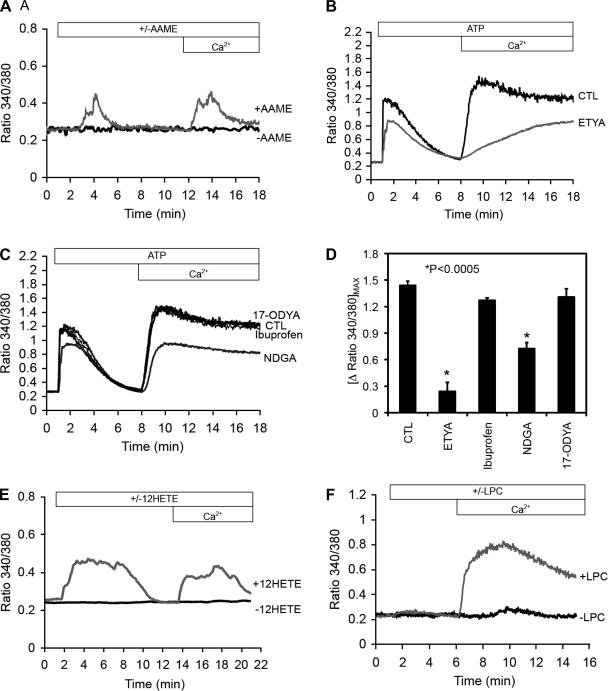

Identification of downstream iPLA2β generated lipid mediators modulating endothelial cell calcium responses.

To further investigate the putative role(s) of iPLA2β in endothelial cell Ca2+ responses, we tested multiple lipid mediators either generated directly by the iPLA2β reaction or through downstream products that may be generated after the release of arachidonic acid by iPLA2β activity. To deliver arachidonic acid across the cell membrane without the typical obligatory sequential coupling to acyl-CoA synthesis, AAME (20 μmol/l) was used, which readily crosses cell membranes allowing access to multiple intracellular membrane compartments before hydrolysis by intracellular esterases to generate free arachidonic acid. The addition of AAME to endothelial cells resulted in a rapid release of calcium from internal stores in calcium free medium and also caused a rise in the calcium signal when calcium was added to the medium (Fig. 9A). We next examined the effects of ETYA, a generic inhibitor of all AA oxidative pathways (12), and found that it reduced ATP-induced cellular calcium increase both from intracellular and extracellular sources (Fig. 9B). Inhibition of arachidonic acid ω-oxidation and epoxygenase-dependent epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (EET) formation by 17-octadecynoic acid (17-ODYA; 10 μmol/l) had no effect on ATP (100 μmol/l)-induced calcium release from intracellular stores, indicating that neither 20-HETE (ω-hydroxylase product) nor EETs (epoxygenase products) are likely involved in iPLA2β-dependent endothelial calcium regulation (Fig. 9, C and D). Similarly, cyclooxygenase inhibition with ibuprofen (20 μmol/l) did not alter ATP-induced calcium flux, indicating that prostanoids are also not involved in this pathway (Fig. 9, C and D). However, lipoxygenase inhibition with nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA; 20 μmol/l) decreased the calcium response indicating that lipoxygenase products such as hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) contribute to the calcium response (Fig. 9, C and D). We found that 12-HETE (4 μmol/l; Fig. 9E), but not 5-HETE or 15-HETE (data not shown), caused increases in intracellular calcium ion similar to AAME, indicating that HETEs may be the downstream product involved in intracellular calcium release. In contrast, administration of LPC (10 μmol/l), a by-product of iPLA2β activity, caused a strong extracellular calcium influx response but did not contribute to intracellular calcium release (Fig. 9F). Previous studies have demonstrated that HETEs contribute to microvascular calcium regulation (28).

Fig. 9.

Representative intracellular calcium profiles (fura-2 ratio, 340 nm to 380 nm) showing the importance of iPLA2β-dependent mediators in the regulation of calcium signaling in endothelial cells. A: cell permeable arachidonic acid derivative AAME caused intracellular calcium release and similar extracellular calcium influx when calcium was added to the medium. B: general inhibition of AA oxidative pathways with 5,8,11,14-eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA) reduced both intracellular and extracellular calcium flux compared with control (CTL). C: inhibition of epoxygenases with 17-octadecynoic acid (17-ODYA) or inhibition of cyclooxygenase with ibuprofen had no effect on the calcium responses. However, inhibiting lipoxygenase with nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) reduced the intracellular and extracellular calcium fluxes, indicating the importance of lipoxygenase metabolites. D: composite data from n ≥ 4 experiments show that arachidonic acid-based lipoxygenase products (*P < 0.0005 from CTL) but not cyclooxygenase or cytochrome 450 products contribute to agonist-induced calcium signaling. E: stimulation with 12-hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (12-HETE) caused similar intracellular and extracellular calcium fluxes as seen with AAME. F: 1-palmitoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) did not cause intracellular calcium increase but caused a strong extracellular calcium influx as seen with ATP stimulation (Fig. 8A).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate multiple important roles of iPLA2β in regulating vasomotor function and calcium signaling in vascular cells. First, it confirms that iPLA2β-generated arachidonic acid and its downstream metabolites are essential to ACh-induced vascular relaxation in vivo and ex vivo. Second, iPLA2β plays a significant role in the agonist-induced constriction of isolated mesenteric arterioles with genetic ablation of iPLA2β in mice resulting in enhanced agonist-induced smooth muscle contraction in isolated vessels. Third, genetic ablation of iPLA2β lowered basal smooth muscle calcium levels, indicating that iPLA2β regulates cytosolic calcium levels and modulates smooth muscle contractility. Fourth, iPLA2β contributes to endothelial-dependent vasomotor responses by regulating eNOS phosphorylation and changes in intracellular calcium concentration in response to agonists. Finally, the iPLA2β-initiated production of eicosanoids leads to the generation of downstream metabolites such as 12-HETE that modulate intracellular calcium homeostasis, whereas the generation of both eicosanoids and LPC contribute to the regulation of agonist-induced extracellular calcium influx in endothelial cells. Collectively, these results underscore the importance of multiple pathways of signaling mediated by iPLA2β that emanate from the concomitant release of arachidonic acid and lysolipids by this enzyme during cellular signaling and demonstrate that iPLA2β-mediated pathways modulate both smooth muscle cell basal calcium homeostasis and stimulus-provoked alterations in calcium concentration, contraction, and relaxation.

Genetic ablation of iPLA2β leads to alterations in vascular responsivity and changes in calcium homeostasis.

In arterioles from mice lacking iPLA2β−/− (Fig. 3), the response to PE-mediated constriction was enhanced compared with that of wild-type controls. Moreover, ACh-mediated vasodilation of the PE-constricted vessels was significantly attenuated. The lack of a vasodilatory response to ACh in PE-constricted vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice indicates that iPLA2β is an essential component mediating vasodilatory responses to ACh (Fig. 3). Remarkably, vessels isolated from iPLA2β−/− mice displayed a significantly lower basal calcium level compared with wild-type vessels (Fig. 3). These findings demonstrate that iPLA2β ablation results in a disruption of calcium homeostasis and sensitivity of downstream calcium-mediated signaling in these vessels. The mechanism(s) responsible for the decreased cytosolic calcium level in iPLA2β−/− vessels with enhanced responsivity to a given concentration of calcium remains to be elucidated. Although the PE-induced absolute calcium alterations were consistently higher in wild-type vessels, the constriction response to added PE was higher in iPLA2β−/− vessels compared with vessels from iPLA2β+/+ animals (Fig. 3C). One possibility is that iPLA2β−/− vessels were more sensitive to small calcium increases through increased kinase activation of contractile proteins that contributed to the increased constriction response to a given calcium concentration. Alternatively, a decreased capacity of the endothelium to cause vasodilation may enhance PE-induced vasoconstriction since the final vessel diameter is the sum of smooth muscle constriction and endothelium-dependent dilation. Denudation of wild-type vessels did not result in an enhanced tone, although the dilation to ACh was significantly reduced. This indicates that under resting conditions, the endothelium did not contribute significantly to the resting diameter. Denudation also did not significantly enhance the constriction to PE, indicating that denudation does not result in agonist-induced smooth muscle hypercontractility in wild-type vessels. However, denudation of iPLA2β−/− vessels induced a significant constriction, indicating that in these vessels the vascular smooth muscle has a significant tone under resting conditions and that an endothelial contribution significantly offsets that tone. The latter observation may be an adaptive response, which would explain the lack of differences in either control vessel diameters and blood pressures in vivo. Since inhibition of iPLA2β in endothelial resulted in a decline of the eNOS activity, the endothelium could compensate by producing other relaxation factors such as prostacyclin or EDHF (1, 37). Alternatively, dilatory mechanisms depending on NO activity may be enhanced to compensate for the reduced NO availability. The mechanism by which the endothelium compensated for the increased smooth muscle tone in iPLA2β−/− vessels remains to be established in further studies. In preliminary experiments, we studied the response to PE in two iPLA2β−/− vessels and found that after denudation the constriction to PE was increased by 56%, further indicating hypercontractility of the smooth muscle. Subsequent ACh did not change the vessel diameter. It is interesting to note that depolarizing KCl did not enhance constriction in vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice. This may indicate a difference in agonist-induced constriction versus constriction induced by a depolarizing agent. Further studies will be needed to elucidate this difference. Taken together, these results would suggest that iPLA2β−/− vessels agonist-induced smooth muscle hypercontractility and not an inability of the endothelium to dilate the vessels is responsible for the enhanced constriction to PE.

After removal of extracellular calcium, vessels from iPLA2β−/− mice still showed a significant initial constriction to PE, indicating that during this phase, calcium is released from intracellular stores (Fig. 4). The subsequent steady-state constriction, however, was markedly less than that observed before calcium removal, suggesting that extracellular calcium contributes to this phase. Subsequent restimulation with PE showed a significantly reduced constriction, indicating that intracellular calcium stores were likely depleted (Fig. 4). This would suggest that PE causes an initial calcium release from intracellular stores resulting in a maximal constriction with the subsequent steady-state constriction dependent upon the influx of extracellular calcium.

These data, taken together, indicate that iPLA2β has a significant role in cellular calcium homeostasis and calcium-contractile coupling. The profound effect of iPLA2β ablation on the basal calcium level (in iPLA2β−/− mice) may explain the lack of blood pressure differences between the wild-type and knockout animals since the lower calcium level in knockout vessels presumably results in a decreased basal vessel tone, thereby representing a compensatory mechanism for preventing hypertension. In addition, the endothelium may provide a compensatory mechanism to offset smooth muscle hypercontractility.

Inhibition of iPLA2β with BEL.

We reported previously that in vitro pharmacological inhibition of iPLA2β with BEL (1 μmol/l) did not affect the PE-induced constriction of rat mesenteric arterioles but greatly decreased the vessel dilation in response to ACh (33). These results have been confirmed in our present ex vivo analysis of arterioles from wild-type mice in which BEL significantly reduced the dilatory response to ACh (Fig. 5). Our data also show that inhibition of iPLA2β with BEL can affect the maximum constrictor response to PE, which was not observed in mouse aorta (5). Nevertheless, the steady-state vessel diameter following treatment with PE was not affected by BEL. Using an ex vivo preparation similar to ours, Park et al. (30) also studied the effect of iPLA2β inhibition with BEL and found that it eliminated the PE-induced constriction in mouse mesenteric vessels. Previous studies from this group have reported that 25 μmol/l BEL dilated PE-constricted vessels (30). The reason for these differences compared with our data is not clear. Park et al. (30) and Smani et al. (35) both used 25 μmol/l BEL, whereas we have routinely used 10 μmol/l, which is ∼five- to 10-fold above the IC50 of BEL for iPLA2β at 2 μmol/l in vitro (20) and 1 μmol/l ex vivo (33). Remarkably, iPLA2β−/− mice demonstrated a greater constriction after PE administration compared with WT mice. Taken together, the results using mice in which iPLA2β was genetically ablated, in conjunction with pharmacological inhibition by BEL, provide new insights into the contribution of iPLA2β on vasomotor regulation and identify the differences between chronic compensated removal of iPLA2β activity through genetic ablation and those which occur following acute pharmacological inhibition with mechanism-based inhibition by BEL. It seems reasonable that pharmacological inhibition with BEL, which blunted the PE effect, may have also blunted contributions from the multiple other iPLA2 family members as well as other enzymes that are targets for BEL. The effects of iPLA2β ablation on calcium levels, vascular contraction, and vascular relaxation have not been reported previously.

Role of iPLA2-dependent mediators in vascular calcium signaling.

Increased cytosolic calcium is an important signal for the production of endothelial dilators including NO (38). Thus decreased iPLA2β activity may not only result in reduced concentrations of arachidonic acid-dependent vasodilators such as prostanoids or cytochrome P-450-derived EDHFs but also NO production due to reduced intracellular calcium availability.

To further study the contribution of iPLA2β activity to vascular regulation, we measured the agonist-induced phosphorylation of eNOS in cultured endothelial cells. Cell lines originating from a variety of vessels including EA.hy926 cells have previously served as a reliable model to study endothelial cell (6) and PLA2 biology (14). Although iPLA2 enzyme activity has been shown in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (16), such activity has not been shown in EA.hy926 cells. Our data indicate, for the first time, specific iPLA2β activity in these cells, making them a suitable model to study iPLA2β-related mechanisms in vascular endothelium. We found that inhibition of iPLA2β by BEL strongly decreased eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177, thus decreasing eNOS activity and production of NO (Fig. 7). Therefore, this decrease in eNOS activity could, in part, explain the reduced dilation response of the iPLA2β−/− blood vessels to endothelium-dependent agonists. Furthermore, we found that lipid products of iPLA2β catalytic activity can mediate both intracellular calcium release as well as extracellular calcium influx. Since eNOS activity is dependent upon calcium-activated calmodulin, a reduction in intracellular calcium would also result in an attenuation of NO-mediated signaling. Moreover, acute inhibition of iPLA2β with BEL may result in a decrease in the concentration of free arachidonic acid, thereby decreasing the availability of vasoactive eicosanoids and reducing phospholipase C stimulation and subsequent diglyceride generation. Thus other endothelium-dependent vasodilatory factors such as PGI2 or EDHF whose action or production depend on intracellular calcium signaling would be affected. General inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolic pathways with ETYA showed that arachidonic acid oxidative products contribute to both intracellular and extracellular calcium fluxes (Fig. 9). Inhibition of cyclooxygenase with ibuprofen or inhibition of cytochrome P-450 epoxygenase(s) with 17-ODYA did not affect the calcium response as measured by fura-2 fluorescence (Fig. 9C), indicating that their respective mediators PGI2 or EETs are not likely involved in endothelial calcium regulation. In contrast, in this model application of 12-HETE resulted in intracellular calcium release similar to AAME, indicating that HETEs may contribute to endothelial calcium regulation similar to results found in other cells (15, 29). Indeed, inhibiting lipoxygenases with nordihydroguaiaretic acid reduced the intracellular calcium response to ATP, indicating that lipoxygenase products such as HETEs may be involved (Fig. 9C). 12-HETE production in endothelial cells has been described previously (32), but its effect on endothelial calcium regulation has not been reported. AAME caused calcium release from intracellular stores in our experiments. The present results identify a prominent downstream AA metabolite (e.g., 12-HETE) in endothelial cells that could mediate the previously observed vasodilatory effects of AA in rat mesenteric arterioles (33). These results differ from observations in mouse intact aorta where AA caused vasoconstriction (5) consistent with the release of an AA-derived vasoconstriction factor (36), indicating that the released active AA metabolite and its subsequent vasomotor activity may differ between vascular beds. Our results are in agreement with previous reports demonstrating LPC-induced increases in extracellular calcium influx into endothelial cells (5, 7).

In summary, we have demonstrated that ablation of iPLA2β in mice effectively eliminated the dilation of mesenteric arterioles in response to ACh, indicating that iPLA2β activity may be a major upstream regulator of vascular reactivity. Although vessels from knockout animals had lower basal calcium levels, PE-induced vasoconstriction was enhanced compared with vessels from wild-type animals. Endothelial denudation in iPLA2β−/− vessels caused significant tone development, indicating that the endothelium may have adapted by a yet unknown mechanism to compensate for the increased agonist-induced smooth muscle hypercontractility enabling resting tone and blood pressure to be maintained. However, agonist-induced endothelium-dependent dilation was reduced likely due to decreased eNOS phosphorylation and agonist-induced calcium responses. Our results demonstrate an important role of iPLA2β activity in vascular smooth muscle cell calcium homeostasis and regulation of contractility as well as regulation of eNOS activity and endothelial agonist-induced calcium responses.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 2RO1-HL-41250 (to R. W. Gross), PO1-HL-57278 (to R. W. Gross and D. R. Abendschein), R37-DK-34388 (to J. Turk), and PO1-NS-32636 and RO1-NS-30555 (to H. H. Dietrich).

DISCLOSURES

R. W. Gross has financial relationships with Lipospectrum and Platomics, which did not contribute to this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Mary L. Ellsworth (Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO) for editorial review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abboud K, Bassila JC, Ghali-Ghoul R, Sabra R. Temporal changes in vascular reactivity in early diabetes mellitus in rats: role of changes in endothelial factors and in phosphodiesterase activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H836–H845, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bao S, Miller DJ, Ma Z, Wohltmann M, Eng G, Ramanadham S, Moley K, Turk J. Male mice that do not express group VIA phospholipase A2 produce spermatozoa with impaired motility and have greatly reduced fertility. J Biol Chem 279: 38194–38200, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao S, Song H, Wohltmann M, Ramanadham S, Jin W, Bohrer A, Turk J. Insulin secretory responses and phospholipid composition of pancreatic islets from mice that do not express Group VIA phospholipase A2 and effects of metabolic stress on glucose homeostasis. J Biol Chem 281: 20958–20973, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohlooly Y, Carlson L, Olsson B, Gustafsson H, Andersson IJ, Tornell J, Bergstrom G. Vascular function and blood pressure in GH transgenic mice. Endocrinology 142: 3317–3323, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boittin FX, Gribi F, Serir K, Beny JL. Ca2+-independent PLA2 controls endothelial store-operated Ca2+ entry and vascular tone in intact aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H2466–H2474, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouis D, Hospers GA, Meijer C, Molema G, Mulder NH. Endothelium in vitro: a review of human vascular endothelial cell lines for blood vessel-related research. Angiogenesis 4: 91–102, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhuri P, Colles SM, Damron DS, Graham LM. Lysophosphatidylcholine inhibits endothelial cell migration by increasing intracellular calcium and activating calpain. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 218–223, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietrich HH, Kimura M, Dacey RG., Jr N-omega-L-arginine constricts cerebral arterioles without increasing intracellular calcium levels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H1681–H1686, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dora KA, Sandow SL, Gallagher NT, Takano H, Rummery NM, Hill CE, Garland CJ. Myoendothelial gap junctions may provide the pathway for EDHF in mouse mesenteric artery. J Vasc Res 40: 480–490, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falcone JC, Kuo L, Meininger GA. Endothelial cell calcium increases during flow-induced dilation in isolated arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H653–H659, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forgione MA, Weiss N, Heydrick S, Cap A, Klings ES, Bierl C, Eberhardt RT, Farber HW, Loscalzo J. Cellular glutathione peroxidase deficiency and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1255–H1261, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glitsch MD, Bakowski D, Parekh AB. Effects of inhibitors of the lipo-oxygenase family of enzymes on the store-operated calcium current ICRAC in rat basophilic leukaemia cells. J Physiol 539: 93–106, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison-Shostak DC, Lemasters JJ, Edgell CJ, Herman B. Role of ICE-like proteases in endothelial cell hypoxic and reperfusion injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 231: 844–847, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasegawa G, Kumagai S, Yano M, Wang YG, Kobayashi Y, Saito Y. 12(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid induces cAMP production via increasing intracellular calcium concentration. FEBS Lett 554: 127–132, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbert SP, Walker JH. Group VIA calcium-independent phospholipase A2 mediates endothelial cell S phase progression. J Biol Chem 281: 35709–35716, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horiuchi T, Dietrich HH, Hongo K, Dacey RG., Jr Comparison of P2 receptor subtypes producing dilation in rat intracerebral arterioles. Stroke 34: 1473–1478, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horiuchi T, Dietrich HH, Tsugane S, Dacey RG., Jr Analysis of purine- and pyrimidine-induced vascular responses in the isolated rat cerebral arteriole. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H767–H776, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikawa T, Kohno F, Kawase R, Yamamoto Y, Nakayama K. Contribution of nitric oxide produced by inducible nitric oxide synthase to vascular responses of mesenteric arterioles in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Br J Pharmacol 141: 269–276, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins CM, Han X, Mancuso DJ, Gross RW. Identification of calcium-independent phospholipase A (iPLA2)beta, and not iPLA2gamma, as the mediator of arginine vasopressin-induced arachidonic acid release in A-10 smooth muscle cells. Enantioselective mechanism-based discrimination of mammalian iPLA2s. J Biol Chem 277: 32807–32814, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins CM, Mancuso DJ, Yan W, Sims HF, Gibson B, Gross RW. Identification, cloning, expression, and purification of three novel human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 family members possessing triacylglycerol lipase and acylglycerol transacylase activities. J Biol Chem 279: 48968–48975, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson Forsell PK, Kennedy BP, Claesson HE. The human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 gene multiple enzymes with distinct properties from a single gene. Eur J Biochem 262: 575–585, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Marquer-Domagala F, Finet M. Comparison of the nitric oxide and cyclo-oxygenase pathway in mesenteric resistance vessels of normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol 121: 588–594, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsay RM, Peet RS, Wilkie GS, Rossiter SP, Smith W, Baird JD, Williams BC. In vivo and in vitro evidence of altered nitric oxide metabolism in the spontaneously diabetic, insulin-dependent BB/Edinburgh rat. Br J Pharmacol 120: 1–6, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McHowat J, Kell PJ, O′Neill HB, Creer MH. Endothelial cell PAF synthesis following thrombin stimulation utilizes Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2. Biochemistry 40: 14921–14931, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meininger GA, Zawieja DC, Falcone JC, Hill MA, Davey JP. Calcium measurement in isolated arterioles during myogenic and agonist stimulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H950–H959, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michell BJ, Griffiths JE, Mitchelhill KI, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Tiganis T, Bozinovski S, de Montellano PR, Kemp BE, Pearson RB. The Akt kinase signals directly to endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Curr Biol 9: 845–848, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller AW, Katakam PV, Lee HC, Tulbert CD, Busija DW, Weintraub NL. Arachidonic acid-induced vasodilation of rat small mesenteric arteries is lipoxygenase-dependent. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 304: 139–144, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nazarewicz RR, Zenebe WJ, Parihar A, Parihar MS, Vaccaro M, Rink C, Sen CK, Ghafourifar P. 12(S)-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) increases mitochondrial nitric oxide by increasing intramitochondrial calcium. Arch Biochem Biophys 468: 114–120, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park KM, Trucillo M, Serban N, Cohen RA, Bolotina VM. The role of iPLA2 and store-operated channels in agonist-induced Ca2+ influx and constriction of cerebral, mesenteric, and carotid arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1183–H1187, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parkington HC, Chow JA, Evans RG, Coleman HA, Tare M. Role for endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in vascular tone in rat mesenteric and hindlimb circulations in vivo. J Physiol 542: 929–937, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosolowsky M, Campbell WB. Synthesis of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic (HETEs) and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) by cultured bovine coronary artery endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Lipids Lipid Metab 1299: 267–277, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seegers HC, Gross RW, Boyle WA. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2-derived arachidonic acid is essential for endothelium-dependent relaxation by acetylcholine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 302: 918–923, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta 1488: 1–19, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smani T, Zakharov SI, Leno E, Csutora P, Trepakova ES, Bolotina VM. Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 is a novel determinant of store-operated Ca2+ entry. J Biol Chem 278: 11909–11915, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang EHC, Vanhoutte PM. Prostanoids and reactive oxygen species: team players in endothelium-dependent contractions. Pharmacol Ther 122: 140–149, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Virdis A, Cetani F, Giannarelli C, Banti C, Ghiadoni L, Ambrogini E, Carrara D, Pinchera A, Taddei S, Bernini G, Marcocci C. The sulfaphenazole-sensitive pathway acts as a compensatory mechanism for impaired nitric oxide availability in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Effect of surgical treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 920–927, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waldron GJ, Ding H, Lovren F, Kubes P, Triggle CR. Acetylcholine-induced relaxation of peripheral arteries isolated from mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Br J Pharmacol 128: 653–658, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolf MJ, Wang J, Turk J, Gross RW. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates smooth muscle cell calcium-independent phospholipase A2. A novel mechanism underlying arachidonic acid mobilization. J Biol Chem 272: 1522–1526, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie Z, Gong MC, Su W, Turk J, Guo Z. Group VIA phospholipase A2 (iPLA2beta) participates in angiotensin II-induced transcriptional up-regulation of regulator of g-protein signaling-2 in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 282: 25278–25289, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.You J, Marrelli SP, Bryan RM., Jr Role of cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor dilations of rat middle cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22: 1239–1247, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]