Abstract

Objective

To determine the feasibility and safety of aripiprazole augmentation for incomplete response to sequential SSRI and SNRI pharmacotherapy in late-life depression.

Method

This study was a 12-week open-label pilot study of 24 patients aged 65 and above (mean age 73.9) diagnosed with MDD who responded partially (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HRSD, 17-item] score of 11–15) or not at all (HRSD >15) to a 16-week trial of escitalopram, followed by either duloxetine (up to 120 mg/d for 12 weeks) or venlafaxine (up to 225 mg/d for 12 weeks). Subjects received 2.5–15 mg/day of adjunctive aripiprazole (average dose 9.0 mg) for 12 weeks. The criterion for remission during treatment with aripiprazole was HRSD ≤ 10 for 2 consecutive weeks.

Results

Of 24 subjects in the intent to treat study group, 19 completed 12 weeks of augmentation with aripiprazole, 12/24 (50%) met criteria for remission, and 2/24 discontinued due to side effects (sedation, akathisia). The mean HRSD score decreased significantly by 6.4 (5.8) points (paired t-test for means, p<0.01, df=16). There were no relapses among the 12 subjects who participated in continuation treatment over a median period of 27.6 weeks.

Conclusions

In older adults with MDD with incomplete response to SSRI and SNRI pharmacotherapy, aripiprazole was well tolerated, and symptoms of depression improved significantly during treatment with aripiprazole. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive aripiprazole for incomplete response in late-life depression is warranted, to further evaluate benefit and risk.

Keywords: aripiprazole, incomplete response, late-life depression

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common in older adults, with estimates of point prevalence ranging from 6–10% in primary care clinic populations 1. Although pharmacotherapy is effective for late life non-psychotic MDD, approximately 50% of older adults with MDD do not respond completely to initial treatment with antidepressant pharmacotherapy, as seen in two large-scale studies, PROSPECT and IMPACT 1;2. Incomplete or partial responders show impaired psychosocial functioning, a guarded prognosis with heightened risk for relapse, and increased mortality 3. The high rate of incomplete response older adults, together with the absence of data on its management, is both a clinical and public health concern.

Recently, atypical antipsychotic agents have been studied as adjunctive or augmentation pharmacotherapy for incomplete response in young and middle-aged adults with major depression. The use of atypical antipsychotics is based upon their effects on serotonergic and dopamininergic neurotransmitter systems, both of which may have a role in anxiety and depression 4;5. A recent meta-analysis found 10 double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of augmentation of an antidepressant with an atypical antipsychotic agents 6. Augmentation with olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine were found to have utility for difficult-to-treat depression. However, the use of atypical antipsychotic agents in late-life depression has not been studied with respect either to efficacy, durability of response, tolerability, or acceptability. We present preliminary information in this report.

The addition of aripiprazole to standard antidepressant pharmacotherapy has been examined in young and mid-life patients with MDD. A double-blind, controlled study of 358 young and middle-aged adults showed that adjunctive aripiprazole therapy may help patients with MDD who respond incompletely to initial antidepressant pharmacotherapy 7. Patients who had an incomplete response to 6 weeks of an SSRI were randomized to receive placebo or 2–20 mg/day of aripiprazole, aiming for an overall target dose of 10 mg/day aripiprazole. Patients taking adjunctive aripiprazole reported significantly greater remission rates compared to placebo: 26.0% vs 15.7%. Aripiprazole was generally well tolerated, with commonly reported adverse events of akathisia (23.1% aripiprazole vs 4.5% placebo), restlessness (14.3% aripiprazole vs 3.4% placebo), and headache (10.8% aripiprazole vs 6.0% placebo). Patients taking aripiprazole had a significantly greater mean weight change compared to placebo.

Evaluating the use of atypical antipsychotics like aripiprazole in late-life is still in its early stages. An open trial of aripiprazole augmentation in 20 older adults with MDD that had not remitted after 6 weeks of treatment with an SSRI was associated with improvement in 50% of the patients 8. The most frequent side effects were dry mouth, agitation/anxiety, drowsiness, nausea, headaches, and blurred vision. These side effects were experienced by 9 patients (45%), 5 of whom described them as moderate to severe. Three patients (15%) discontinued aripiprazole due to side effects.

We hypothesized that combined pharmacotherapy using an antidepressant with aripiprazole would be an effective, tolerable, and acceptable treatment strategy for older adults with incomplete response to sequential treatment with both SSRI and SNRI. We chose aripiprazole for several reasons. Relative to other atypical antipsychotics, it has lower anticholinergicity and less tendency to promote weight gain. Data from controlled evaluations in non-geriatric adults show efficacy, utility, and acceptability as adjunctive pharmacotherapy in incomplete responders 7.

Methods

Subjects

Between June 1, 2006 and June 1, 2007, 24 subjects aged 65 and above were recruited for aripiprazole augmentation therapy as part an open-label pilot study nested in a larger, 5-year study of maintenance therapies in late-life depression (MTLD-III; MH43832, C.F. Reynolds PI). Altogether a total of 268 patients began treatment in the parent MTLD-III study, and 130 remitted and were able to be randomly assigned to experimental maintenance treatment cells. The 24 participants in the apriprazole pilot study were a subgroup of the 268 who began MTLD-III. Recruitment occurred by word of mouth, referrals from clinicians, advertisements, and presentations to lay groups of older adults and their families. All subjects were currently experiencing a non-psychotic, unipolar major depressive episode as established by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), had a baseline rating of 15 or higher on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-17), and scored at least 18 on the Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE). Participants were excluded from enrollment in the MTLD-III if they had a SCID lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective or other psychotic disorders, a history of alcohol/drug abuse within the past 12 months, or if they had a diagnosis of dementia. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Enrollment Criteria for the Open-Label, Pilot Study

The current study was an open-label pilot study of aripiprazole augmentation in patients who responded partially (11–15 on the HRSD) or not at all (>15) to first-line antidepressant pharmacotherapy with escitalopram (up to 20 mg for 16 weeks), followed by either duloxetine (up to 120 mg/d) or venlafaxine (up to 225 mg/d) for 12 weeks.

Measures and Assessments

Subjects’ demographic information and history of depression were assessed and a physical examination was performed before study entry. Key assessments (baseline and at weekly follow-ups) included depression severity (HRSD-17) 9, anxiety severity (Brief Symptom Inventory- Anxiety subscale) 10, UKU Side Effect Scale (UKU) 11, and weight. Since akathisia is a common side effect of atypical antipsychotics, including aripiprazole, we also examined the item in UKU scale which is specific for akathisia complaints. We defined akathisia as a side effect if a subject experienced a one point increase at any one time point during aripiprazole exposure. Similarly, we monitored restlessness as a side effect using an item from the BSI-anxiety subscale. Restlessness was scored as: no restlessness (0 points); mild restlessness (1 point); significant, but transient (2 points); significant, but persistent (3 points).

Demographic and clinical characteristic of participants

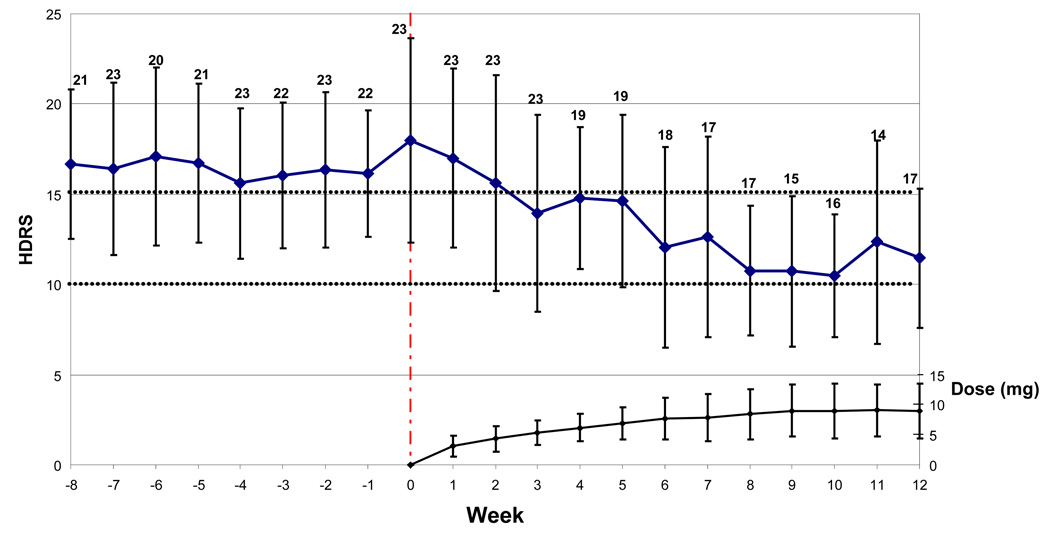

The subjects who received augmentation therapy with aripiprazole had a mean age of 73.9 (SD 6.6; range: 65–91). Of the participants, 58.3% were female; 8.3% were black; and 75.0% had a history of an anxiety disorder. 70.8% had HRSD scores of 15 or higher at start of aripiprazole administration; and 29.1% had HRSD score of 11–14 at the time of aripiprazole administration. The fact that 29% could be considered partially remitted at entry into the augmentation phase could have decreased the likelihood of demonstrating significant improvement over the next 12 weeks and thus provides a useful preliminary test of aripiprazole value. At the start of aripiprazole treatment, the mean baseline HRSD score was 18.0 (SD 5.7). Furthermore, the baseline BSI anxiety subscale score was 1.4 (SD 0.8). The baseline UKU side effects score was 13.4 (SD 5.4). All subjects except one had pre-treatment Folstein scores of ≥26; one subject had a score of 21.

Intervention with aripiprazole

Once patients began aripiprazole, the dose of the current antidepressant medication was held constant as aripiprazole dose was titrated according to tolerability and clinical improvement. The starting dose was 2.5 mg per day and the maximal dose was 15 mg per day. We increased dose in 2.5 mg/d increments weekly. The average dose of aripiprazole at 12 weeks was 9.0 mg per day (SD: 4.5). Because treatment non-adherence or self-medication with alcohol could both be confounding factors in determining the clinical benefit of adjunctive aripiprazole, we addressed these issues by asking at each clinic visit if participants finished the antidepressant medication and aripiprazole allotment for the given week. Similarly, we asked about the number of alcoholic beverages consumed at each weekly visit, reasoning that self-medication with alcohol can be associated with difficult-to-treat depression.

An intent-to-treat mixed effect analysis examined weekly depression scores over 12 weeks of treatment in all 24 subjects. Changes in depression, anxiety and side effect scores from week 0 to week 12 were tested with paired t-tests. At baseline severity of depression (HRSD) and anxiety (BSI) were correlated with one another (r=.60, n=23, p=.003).

Results

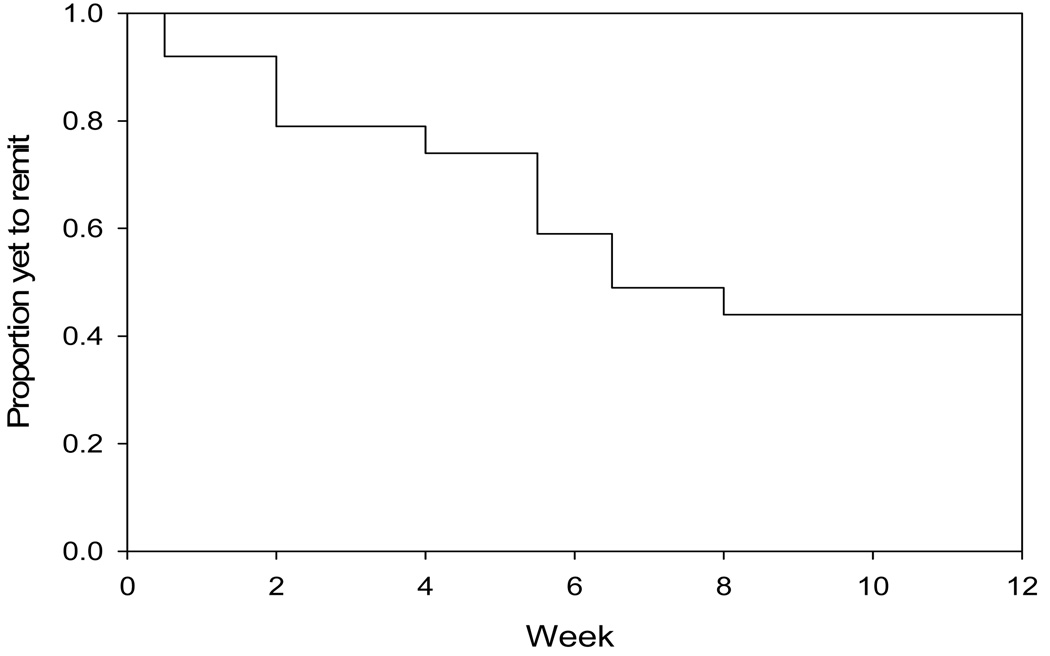

Nineteen of 24 (79%) patients completed all 12 weeks of augmentation with aripiprazole, and 12/24 (50%) met criteria for remission (Figure 1). Hamilton depression scores showed a significant decrease during exposure to aripiprazole (mixed effects analysis, F(1,23)=21.20, p<.0001); Figure 2 shows changes in Ham-D during initiation and titration of aripiprazole.

Figure 1.

Aripiprazole augmentation of SNRI in TRLLD: Survival Curve of Time to Remission

Figure 2.

Improvement in Depressive Symptoms (Ham-D) Following Initiation of Aripiprazole Augmentation

Three of 24 (13%) dropped out by week 12 due to failure to improve or withdrawal of consent, and 2/24 (8%) discontinued due to side effects (one each: sedation, akathisia). Side effects were also examined via the UKU side effects scale 11. Overall UKU scores showed a decline (indicating fewer reports of somatic complaints than before use of aripiprazole). However, the mean score of the UKU-Neurologic subscale increased (it includes a specific akathisia item).

We examined akathisia and restlessness in more detail, given the association of aripiprazole with these side effects in studies of young adults. Six of 24 (25%) subjects had a positive score on the UKU-akathisia item during at least one time point; however, in all but one case these were mild and/or transient. On the other hand, 74% of subjects reported an at least mild increase in the BSI-restlessness item on at least one time point during the 12-week trial. In the absence of a placebo and given overall decreases in anxiety, these data are difficult to interpret; however, clinically we observed that most of these subjects had an initial decrease in restlessness from baseline (representing improved anxiety) during the initial portion of the 12-week trial, with a subsequent increase in restlessness as the aripiprazole dose approached 15mg/day. Akathisia was typically mild and transient, only infrequently resulting in medication discontinuation. However, restlessness may reflect a common and dose-related side effect that could counteract aripiprazole’s therapeutic effect. Our preliminary results are in agreement with studies of aripiprazole in younger adults with TRD 7;12, which found that restlessness at higher doses of aripiprazole typically resolved promptly with a lowering of the dose. Our results are also comparable to a small study of aripiprazole augmentation in elderly depressed patients (mean age 63) who had responded incompletely to six weeks of escitalopram 8. That 12-week study had similar completion (75%) and remission rates (50% reached Ham-D≤10), and similar adverse events were observed (mainly restlessness).

We also examined metabolic changes and weight gain. One subject had a significant increase in lipids, and none had a significant increase in blood sugar, suggesting that metabolic effects were infrequent with aripiprazole. Weight gain was highly variable: 9/15 (60%) gained <2kg (mean [range] 0.8 [−0.7– 1.8]) while 6/15 (40%) gained >3kg (mean [range] 4.7 [3.2–6.4]), suggesting that an examination of sources of weight gain variability would be useful. We were not able to determine whether weight gain represented an increase in adiposity vs. an increase in lean body mass with remission from depression.

Finally, we examined continuation treatment outcomes: the 12 remitted subjects continued treatment over a median period of 27.6 weeks. None of these participants experienced relapse of a major depressive episode. One of 12 participants was non-compliant with study procedures (due to respondent burden and other treatment preferences) and exited the study. UKU side effect scores remained stable, and body mass index was also stable over 6 months of continuation phase pharmacotherapy. One participant each had a spike in glucose, triglycerides, and cholesterol/LDL. In general, glucose and TG showed minimal change, suggesting that aripiprazole does not cause insulin resistance as do some other stypicols. These pilot data support the feasibility and acceptability of continuation treatment with aripipazole.

Adherence

The mean percentage of medication doses taken was 91.6% (standard deviation 17.8%) and the median percentage of doses taken was 98.1%. Eighteen subjects (75%) reported missing at least one dose of aripiprazole. Three patients (12.5%) reported an average of greater than one missed dose per week; two of those patients subsequently discontinued aripiprazole.

Alcohol use

Nine subjects (37.5%) reported no alcohol use while in the study, while 15 subjects (62.5%) reported at least one instance of alcohol use. One subject, who reported an average of 57.5 drinks per week, dropped out of the study after two weeks.

Discussion

In older adults with MDD showing incomplete response to seqential SSRI and SNRI pharmacotherapy, remission was achieved in 50% during aripiprazole augmentation. In subjects who remitted, improvements in depression were stable throughout continuation treatment (median: 6-months). Aripiprazole was well-tolerated, with a low rate of dropout due to side effects (8%) and a high completion rate (79%), but restlessness and weight gain were not uncommon. A larger, placebo-controlled study is needed to test hypotheses related to remission, stability of remission, tolerability, safety, and outcome predictors.

We established incomplete response to SSRI and SNRI pharmacotherapy before exposing patients to aripiprazole. Even in this difficult-to-treat group, the use of aripiprazole was associated with clinically meaningful reductions in symptom burden. Two of 24 patients left the study because of apparent side effects (sedation, akathisia). Thus, overall, aripiprazole was well tolerated. Future placebo-controlled studies of adjunctive aripiprazole are needed to evaluate metabolic, neurologic, and electrocardiographic effects of aripiprazole systematically. This approach will allow simultaneous estimates of both potential benefit and risk.

Other data have suggested that sequential treatment of incomplete response in late life depression leads to a cumulative overall response rate of about 75%. That is, whether we augment with antidepressants (e.g., 13) or switch to a different class of antidepressant (e.g., 14), about 50% of incomplete responders show meaningful clinical improvement. In this context, adjunctive use of aripiprazole seems to be a promising strategy to evaluate. It has been shown in a placebo-controlled trial to be an effective adjunctive therapy in young and middle-aged adults with incomplete antidepressant response 7, and our pilot data suggest but do not prove that it may be efficacious and well-tolerated in older adults who have failed sequential pharmacotherapy with SSRI and NRI agents.

Regarding the necessity of a geriatric trial, older patients with depression usually have a high burden of medical illness, are subject to extensive medication regimens, and often experience adverse drug effects 15. In general, pharmacokinetic changes associated with aging result in higher and more variable drug concentrations in older patients. Nonetheless, available information on pharmacokinetics of antidepressants is inadequate particularly with regard to medical subgroups and potential drug interactions 16. Because geriatric patients have been excluded from RCT’s, a placebo-controlled geriatric study is needed to determine specifically whether aging-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors influence treatment response or tolerability.

In future controlled evaluation of aripiprazole, the role of potential predictors and moderators of treatment response variability should be systematically evaluated. These include symptoms of anxiety (e.g., 17), coexisting medical burden (e.g., 18), and pharmacogenetic polymorphisms (e.g., 19).

Finally, developing treatment strategies that are practicable in general medical settings, where most older Americans receive treatment for depression (if they receive it at all), is of great public health significance 1;2. A proven pharmacologic augmentation strategy, with well documented benefit to risk ratio, would be amenable to dissemination and uptake in primary care medicine.

Table 1.

Measures of Clinical Change during Exposure to 12 Weeks of Aripiprazole

| Measure | N | Mean (SD) at Week 0 |

Mean (SD) at Week 12 |

Change (SD) |

Effect Size1 |

T | p-value2 | Degrees of Freedom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRSD-17 | 17 | 17.9 (5.7) | 11.5 (3.9) | −6.41 (5.08) |

1.26 | 5.20 | <0.01 | 16 |

|

Anxiety subscale of BSI |

14 | 1.52 (0.86) | 0.77 (0.98) | −0.752 (1.169) |

0.64 | 2.41 | 0.03 | 13 |

|

UKU- Total |

17 | 13.7 (5.8) | 10.0 (4.0) | −3.71 (4.88) |

0.76 | 3.13 | <0.01 | 16 |

|

UKU- Psych |

17 | 7.7 (2.7) | 5.6 (2.2) | −2.05 (2.28) |

0.90 | 3.73 | <0.01 | 16 |

|

UKU- Neuro |

17 | 0.8 (0.9) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.35 (1.11) |

0.32 | −1.31 | 0.21 | 16 |

|

UKU- Auto |

17 | 4.4 (2.8) | 2.5 (1.6) | −1.88 (2.96) |

0.64 | 2.62 | 0.02 | 16 |

|

UKU- Other3 |

17 | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.1) | −0.12 (1.36) |

0.09 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 16 |

Cohen’s d effect size

Paired t-test for means

Symptoms in the UKU-Other subscale include rash, skin changes, weight loss or gain, and sexual desire and dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the ACISR/LLMD Clinical Trials Management Unit for their care of the participants in this study.

Supported by P30 MH071944, R37 MH43832, R01 MH37869, and T32 MH19986; the John A. Hartford Foundation; and by the UPMC endowment in geriatric psychiatry. Bristol Meyers Squibb supplied aripiprazole for the conduct of this pilot study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None

Clinical Trials Gov No.: NCT00177671

Reference List

- 1.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late-life: Consensus statement update. JAMA. 1997;278:1186–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein DJ, Westenberg HGM, Liebowitz MR. Social anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: Serotonergic and dopaminergic neurocircuitry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbee JG, Conrad EJ, Jamhour NJ. Aripiprazole augmentation in treatment-resistant depression. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16:189–194. doi: 10.1080/10401230490521954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Smith J, et al. Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotic medications for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:826–831. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berman RM, Marcus RN, Swanink R, et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:843–853. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutherford B, Sneed J, Miyazaki M, et al. An open trial of aripiprazole augmentation for SSRI non-remitters with late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:986–991. doi: 10.1002/gps.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derogatis L. Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures manual. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, et al. The UKU side effect rating scale. A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1987;334:1–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb10566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adson DE, Kushner MG, Fahnhorst TA. Treatment of residual anxiety symptoms with adjunctive aripiprazole in depressed patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Affect Disord. 2005;86:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dew MA, Whyte EM, Lenze EJ, et al. Recovery from major depression in older adults receiving augmentation of antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:892–899. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karp JF, Whyte EM, Lenze EJ, et al. Rescue pharmacotherapy with duloxetine for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor nonresponders in late-life depression: Outcome and tolerability. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:457–463. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lotrich FE, Pollock BG. Aging and clinical pharmacology: implications for antidepressants. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:1106–1122. doi: 10.1177/0091270005280297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollock BG. The pharmacokinetic imperative in late-life depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:S19–S23. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000162809.69323.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreescu C, Lenze EJ, Dew MA, et al. Effect of comorbid anxiety on treatment response and relapse risk in late-life depression: Controlled study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190:344–349. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.027169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reynolds CF, Dew MA, Pollock BG, et al. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1130–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollock BG, Ferrell RE, Mulsant BH, et al. Allelic variation in the serotonin transporter promoter affects onset of paroxetine treatment response in late-life depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:587–590. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]