Abstract

Calcimimetics activate the calcium-sensing receptor (CaR) and reduce parathyroid hormone (PTH) by increasing the sensitivity of the parathyroid CaR to ambient calcium. The calcimimetic, cinacalcet, is effective in treating secondary hyperparathyroidism in dialysis patients [chronic kidney disease (CKD 5)], but little is known about its effects on stage 3–4 CKD patients. We compared cinacalcet and paricalcitol in uremic rats with creatinine clearances “equivalent” to patients with CKD 3–4. Uremia was induced in anesthetized rats using the 5/6th nephrectomy model. Groups were 1) uremic control, 2) uremic + cinacalcet (U+Cin; 15 mg·kg−1·day−1 po for 6 wk), 3) uremic + paricalcitol (U+Par; 0.16 μg/kg, 3 × wk, ip for 6 wk), and 4) normal. Unlike U+Par animals, cinacalcet promoted hypocalcemia and marked hyperphosphatemia. The Ca × P in U+Cin rats was twice that of U+Par rats. Both compounds suppressed PTH. Serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 was decreased in both U+Par and U+Cin rats. Serum FGF-23 was increased in U+Par but not in U+Cin, where it tended to decrease. Analysis of tibiae showed that U+Cin, but not U+Par, rats had reduced bone volume. U+Cin rats had similar bone formation and reduced osteoid surface, but higher bone resorption. Hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, low 1,25-(OH)2D3, and cinacalcet itself may play a role in the detrimental effects on bone seen in U+Cin rats. This requires further investigation. In conclusion, due to its effects on bone and to the hypocalcemia and severe hyperphosphatemia it induces, we believe that cinacalcet should not be used in patients with CKD without further detailed studies.

Keywords: calcimimetics, vitamin D, hyperphosphatemia, uremia, bone formation and bone resorption

patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) almost universally develop secondary hyperparathyroidism (SH) leading to a variety of adverse effects on bone in CKD patients (28, 36, 40, 41). The progression of SH is accompanied by a decrease in both the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and the calcium-sensing receptor (CaR) in the parathyroid gland (5, 16, 20, 22, 26). Studies in patients with CKD show the efficacy not only of active vitamin D compounds in the treatment of SH (10, 38) but also of newer calcimimetic drugs as well (3, 23, 29). Active vitamin D compounds suppress both parathyroid hormone (PTH) synthesis and secretion (30, 34) via the VDR, but due to the calcemic and phosphatemic properties of 1,25-(OH)2D3, the active form of vitamin D3, vitamin D analogs which retain the therapeutic properties of 1,25-(OH)2D3, but are less calcemic and phosphatemic, have been developed and are currently in use for the treatment of SH in dialysis patients (2, 4, 39).

One of these analogs, a specific VDR activator (VDRA), currently used in patients is paricalcitol. Paricalcitol is effective at suppressing PTH but is much less calcemic and phosphatemic than 1,25-(OH)2D3 (8). On the other hand, calcimimetic drugs act by activating the CaR and enhancing the gland's sensitivity to extracellular calcium (Ca), resulting in the suppression of PTH secretion without the induction of hypercalcemia (14, 27). Currently, the calcimimetic, cinacalcet, is used in dialysis patients (CKD stage 5) for the treatment of SH.

Cinacalcet treatment in patients on hemodialysis can effectively suppress PTH levels and lower serum Ca and phosphorus (P) concentrations leading to a reduction in the Ca × P product of ∼13% (3). This effect is in contrast to vitamin D therapy, which, if not well monitored, can increase serum Ca and P. The decrease in serum P with cinacalcet therapy is likely due to decreased release of P from bone and/or decreased intestinal absorption of P. However, the impact of cinacalcet on P can be significantly different in nondialysis-dependent CKD patients (stages 3–4). In the presence of renal function, the decrease in PTH by cinacalcet causes a decrease in urinary P excretion leading to P retention and an increase in serum P (6, 7). Indeed, in a phase III trial of cinacalcet in nondialysis-dependent CKD patients treated for 32 wk, cinacalcet led to a 21% increase in serum P (7). In addition, serum Ca was 1 mg/dl lower in cinacalcet-treated participants. While the hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia resulted in a Ca × P product that did not differ from control, it is questionable whether having a “good” Ca × P product at the expense of hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia is beneficial to these patients. Indeed, independent of serum Ca levels, a high serum P has been shown to be associated with increased mortality in this patient population (19). In studies in this same patient group (CKD 3–4), paricalcitol treatment induced a significant suppression of serum PTH without the development of hyperphosphatemia (8). Thus, a decrease in PTH cannot be the whole explanation for the development of the hyperphosphatemia observed in cinacalcet-treated patients with CKD 3–4. Since little is known about how cinacalcet affects stage 3–4 CKD patients, we designed the present study to compare the serum chemistries, urinary phosphate excretion, FGF-23 expression, and bone histomorphometry in paricalcitol- and cinacalcet-treated rats with renal function equivalent to stages 3–4 CKD.

METHODS

Animal Studies

Chronic.

All studies were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee in accordance with federal regulations. Renal insufficiency was induced by 5/6 nephrectomy in a group of female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing from 225 to 250 g. This involves the ligation of several branches of the left renal artery and excision of the right kidney. At the onset of uremia, rats were divided into groups and treated for 6 wk as follows: uremic control (UC; vehicle: 100 μl propylene glycol), uremic + paricalcitol (U+Par; 0.16 μg/kg body wt ip, 3 × wk), and uremic + cinacalcet (U+Cin; 15 mg/kg body wt daily by gavage). A group of normal rats also served as control (N). The dose of 15 mg/kg body wt for cinacalcet was chosen after consulting both the literature and experts in the field of calcimimetics. All animals were fed a diet containing 1.2% P and 0.8% Ca and given tap water ad libitum. On days 10 and 2 before death, the rats received an injection of calcein (10 mg/ml in PBS, 0.1 ml/100 g body wt) for histomorphometric analysis. The last few days of the study, the rats were placed in metabolic cages and urine was collected for 2- to 24-h periods for analysis of urinary P and Ca excretion. At the end of the 6-wk treatment period, the rats were killed ∼20 h after their last treatment. Blood was taken for analysis of serum chemistries, alkaline phosphatase, PTH, FGF-23, 1,25-(OH)2D3, and COOH-terminal telopeptides of rat type I collagen (RatLaps). The tibiae were harvested, cleaned of muscle, and stored in 70% ETOH until histomorphometric analyses were performed. Total Ca was determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Perkin-Elmer, model 1100B, Norwalk, CT) and ICa using a Nova 8 electrolyte analyzer (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA). Plasma Cr, P, and alkaline phosphatase were determined by autoanalyzer (COBAS MIRA plus, Branchburg, NJ). Serum PTH was determined using a rat PTH ELISA kit from Immutopics (San Clement, CA). Serum FGF-23 was determined using an FGF-23 ELISA kit from Kainos Laboratories (Tokyo, Japan). Serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 was assessed using a 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D RIA from Immunodiagnostics Systems (Fountain Hills, AZ) and RatLaps was determined using a RatLaps ELISA kit also from Immunodiagnostics Systems.

Acute FGF-23 study.

A sample of blood was drawn via the tail from previously untreated normal rats and rats that had been uremic for 2–3 wk for determination of serum FGF-23. Rats were then given cinacalcet (30 mg/kg body wt) by oral gavage or paricalcitol [1.2 μg/kg body wt ip (300 ng/rat)]. Another blood sample was obtained 24 h later. Pre- and posttreatment serum samples were analyzed for FGF-23.

Bone histomorphometry measurements of tibial trabecular bone.

Randomly selected tibiae from each group were analyzed. After being dehydrated in ethanol, tibiae were embedded, undecalcified, in methylmethacrylate. The proximal tibial metaphyses were sectioned longitudinally with a Leica/Jung 2265 microtome in 5-μm-thick sections for von Kossa and tetrachrome double staining for analysis by light microscopy and in 8-μm-thick sections, which were left unstained, for measurement of fluorochrome-based indexes. Tibial shafts were cut into 40-μm sections using a precision diamond wire saw (Well Diamond Wire Saw, Norcross, GA). Bone histomorphometric analyses were performed in the secondary spongiosa of the right proximal tibia that included the trabecular area between 0.1 and 3 mm proximal to the growth plate and within the cortex. Bone architectural parameters were evaluated using a semiautomatic image analysis Bioquant system (Bioquant Image Analysis, Nashville, TN) linked to a microscope equipped with transmitted and fluorescent light.

Statistical Analyses

All data are expressed as means ± SE. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey posttest was used for comparison between uremic groups. Student's nonpaired t-test was used to compare the normal control group with individual uremic groups and a Student's paired t-test was used to compare pre- and postmatched data within a group.

RESULTS

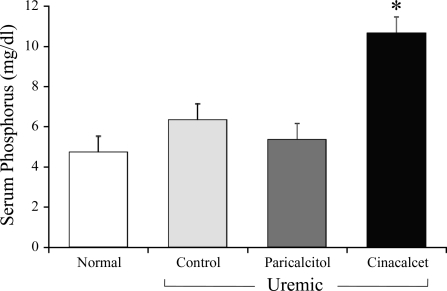

There was no significant difference in body weight between the groups (normal = 251.5 ± 4.1, UC = 248.4 ± 3.5, U+Par = 251.7 ± 2.6, and U+Cin = 263.6 ± 5.4). Table 1 shows serum chemistries from all groups of rats in the chronic study. As expected, serum creatinine (Cr) was similarly increased and Cr clearance decreased in the three groups of uremic rats compared with normal control (N) animals (P < 0.01). As seen by both ionized Ca (ICa) and total Ca, cinacalcet-treated rats (U+Cin) became slightly hypocalcemic compared with the other three groups (P < 0.01). As highlighted also in Fig. 1, serum P was markedly increased in rats receiving cinacalcet (P < 0.01), but not in UC rats or U+Par rats. This increase in P in U+Cin rats was accompanied by a marked increase in the Ca × P product (P < 0.01) that was more than twice that of the normal group. The Ca × P in UC or U+Par rats did not differ from normal. Six weeks of uremia increased serum PTH levels. While treatment with either paricalcitol or cinacalcet suppressed this increase, the suppression did not reach significance. Rats were killed ∼20 h after their last treatment. Whereas suppression of PTH by cinacalcet is more transient, requiring daily dosing, suppression of PTH by active vitamin D analogs is more sustained, requiring less frequent dosing. We therefore drew blood from U+Cin rats 4 h after their final treatment (16 h before death) for PTH determinations. These results are also depicted in Table 1. Four hours after the final cinacalcet treatment, PTH was dramatically lower, 24.1 ± 3.0 pg/ml. Total serum alkaline phosphatase was elevated in all three uremic groups (N: 37.8 ± 4.7, UC: 52.5 ± 4.3, P = 0.059; U+Par: 48.1 ± 3.5, P = 0.100; and U+Cin: 89.9 ± 7.0 U/l, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Serum chemistries

| Normal (n = 6) | UC (n = 14) | U + Par (n = 11) | U + Cin (n = 12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 1.39 ± 0.10d | 1.25 ± 0.05d | 1.31 ± 0.14d |

| Phosphorus, mg/dl | 4.70 ± 0.13 | 6.31 ± 0.80 | 5.33 ± 0.45c | 10.62 ± 1.23a,d |

| Ionized calcium, mg/dl | 4.73 ± 0.02 | 4.53 ± 0.06e | 4.81 ± 0.04a,c | 3.97 ± 0.07a,d |

| Total calcium, mg/dl | 9.72 ± 0.15 | 9.57 ± 0.16 | 9.77 ± 0.17c | 8.99 ± 0.09d,e |

| Ca × P product, mg2/dl2 | 45.6 ± 1.2 | 60.2 ± 7.6 | 51.9 ± 4.4c | 95.3 ± 10.9d,e |

| PTH, pg/ml | 39.4 ± 5.04 | 365.5 ± 150.8 | 189.2 ± 68.8 | 251.5 ± 60.2 |

| (4 h) 24.1 ± 3.0 | ||||

| Cr clearance, ml/min | 0.79 ± 0.04 | 0.40 ± 0.03d | 0.41 ± 0.02d | 0.43 ± 0.03d |

Values are means ± SE; n = number of rats. Normal or uremic (5/6 nephrectomized) rats underwent one of the following experimental protocols for 6 wk: normal + vehicle (propylene glycol), uremic + vehicle (UC), uremic + paricalcitol (U + Par), and uremic + cinacalcet (U + Cin).

P < 0.01 vs. UC,

P < 0.05 vs. UC using ANOVA and Tukey posttest.

P < 0.01 vs. U + Cin using ANOVA and Tukey posttest.

P < 0.01 vs. normal,

P < 0.05 vs. normal comparing normal with uremic groups, using nonpaired t-test.

Fig. 1.

Effect of paricalcitol and cinacalcet on plasma phosphorus in uremic rats. At the onset of uremia, rats were given vehicle (100 μl of propylene glycol), paricalcitol (0.16 μg/kg body wt ip, 3 × wk), or cinacalcet (15 mg/kg body wt daily by gavage) for 6 wk. Normal rats served as control. Results are expressed as means ± SE (*P < 0.01 vs. all other groups); n = 6 for normal, n = 14 for uremic control, n = 11 uremic + paricalcitol, and n = 12 for uremic + cinacalcet.

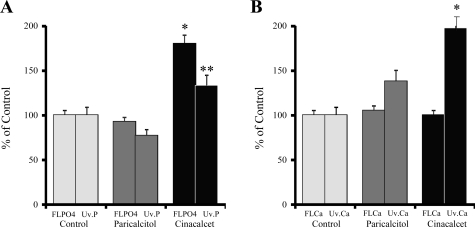

Urinary P and Ca results are shown in Fig. 2. As seen in Fig. 2A, the filtered load of P (FLPO4) and urinary excretion of P (Uv.P) were not different between UC rats and U+Par animals. However, the FLPO4 was 94% higher in U+Cin rats compared with U+Par animals (180.2 vs. 92.7%, P < 0.001 or 4.18 ± 0.25 vs. 2.15 ± 0.16 mg/min, P < 0.001). The Uv.P, although slightly increased in the U+Cin rats, did not compensate for the significant increase in the FLPO4. Due to the hypocalcemia seen in cinacalcet-treated rats, we expected to see a concomitant decrease in urinary Ca. To the contrary, Fig.2B shows that while the FLCa was unchanged among the three uremic groups, 24-h urinary Ca excretion was significantly increased (197.3%) in uremic rats treated with cinacalcet compared with both UC rats and with U+Par animals (P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Effect of paricalcitol and cinacalcet on filtered load of phosphorus (FLPO4) and urinary phosphorus excretion (Uv.P; A) and on filtered load of calcium (FLCa) and urinary calcium excretion (Uv.Ca; B) in uremic rats. At the onset of uremia, rats were given vehicle (100 μl of propylene glycol), paricalcitol (0.16 μg/kg body wt ip, 3 × wk), or cinacalcet (15 mg/kg body wt daily by gavage) for 6 wk. At the end of the study, 24-h urinary collections were analyzed. Results are the average of 2 24-h urinary collections and are expressed as means ± SE (*P < 0.001 vs. uremic control and uremic + paricalcitol, **P < 0.01 vs. uremic control and uremic + paricalcitol); n = 14 for uremic control, n = 11 uremic + paricalcitol, and n = 12 for uremic + cinacalcet.

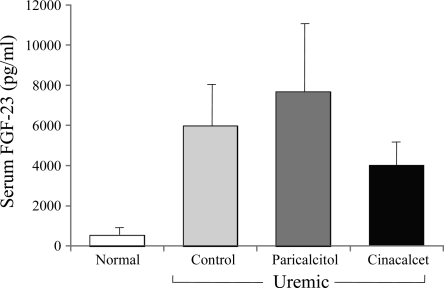

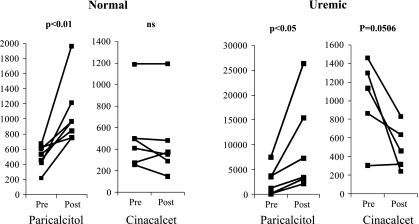

After 6 wk of treatment, serum FGF-23 levels (Fig. 3) were higher in U+Par rats compared with UC animals (7,650 ± 3,462, range = 1,383 to 41,339 vs. UC: 5,962 ± 2,545, range = 910–29,606 pg/ml). FGF-23 levels were actually lower in the cinacalcet group (3,987 ± 1,045 pg/ml, range = 1,097–13,691). However, due to the wide range of serum levels of FGF-23 seen in uremic rats, significance could not be detected. We therefore performed acute studies in normal and uremic rats to monitor changes in FGF-23 in individual rats using paired t-analysis (Fig. 4). After a single injection of 300 ng of paricalcitol, FGF-23 significantly increased in both normal (pre: 502 ± 59 vs. post: 1,062 ± 162 pg/ml, P < 0.01) and uremic rats (pre: 2,327 ± 1,033 vs. post: 8,675 ± 3,418 pg/ml, P < 0.05). Treatment with cinacalcet treatment had no effect on serum FGF-23 in normal rats (pre: 519 ± 141 vs. post: 472 ± 151 pg/ml), but produced a decrease in FGF-23 levels in uremic rats (1,009 ± 202 vs. post: 496 ± 108 pg/ml, P = 0.0506).

Fig. 3.

Effect of paricalcitol and cinacalcet on serum FGF-23 in uremic rats. At the onset of uremia, rats were given vehicle (100 μl of propylene glycol), paricalcitol (0.16 μg/kg body wt ip, 3 × wk), or cinacalcet (15 mg/kg body wt daily by gavage) for 6 wk. Normal rats served as control. Results are expressed as means ± SE; n = 6 for normal, n = 14 for uremic control, n = 11 uremic + paricalcitol, and n = 12 for uremic + cinacalcet.

Fig. 4.

Effect of paricalcitol and cinacalcet on serum FGF-23 in normal and uremic rats. Normal or uremic rats were treated with 1 dose of paricalcitol (300 ng/rat ip) or cinacalcet (30 mg/rat by gavage). Blood was drawn before and 24 h after treatment. Results were analyzed by paired t-test. Each line represents an individual animal; n = 7 for normal + paricalcitol, n = 6 for normal + cinacalcet, n = 6 for uremic + paricalcitol, and n = 5 for uremic + cinacalcet. Notice the different scales used, which clearly demonstrate the differences in response between paricalcitol- and cinacalcet-treated groups, especially in uremic animals. NS, not significant.

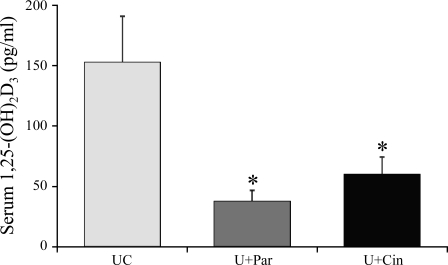

Figure 5 shows that treatment with either paricalcitol or cinacalcet significantly decreases serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels compared with UC animals (UC: 152.2 ± 22.7; U+Par: 37.1 ± 12.3, P < 0.01; and U+Cin: 59.2 ± 19.3 pg/ml, P < 0.01).

Fig. 5.

Effect of paricalcitol and cinacalcet on serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 in uremic rats. At the onset of uremia, rats were given vehicle (100 μl of propylene glycol), paricalcitol (0.16 μg/kg body wt ip, 3 × wk), or cinacalcet (15 mg/kg body wt daily by gavage) for 6 wk. Normal rats served as control. Results are expressed as means ± SE; n = 6 for normal, n = 14 for uremic control (UC), n = 11 uremic + paricalcitol (U+Par), and n = 12 for uremic + cinacalcet (U+Cin).

The key bone histomorphometric parameters of this study are trabecular bone volume, trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) and number (Tb.N), osteoid surface (OS), bone formation rate (BFR), and osteoclast surface (Table 2). Cinacalcet seemed to have a negative effect on bone balance with rats displaying decreased bone volume and increased bone resorption, but similar bone formation compared with untreated uremic rats. Bone volume was significantly decreased in U+Cin rats compared with all other groups (P < 0.001). In addition, BS was dramatically reduced in this group (P < 0.001). While Tb.Th did not significantly vary among the four groups, Tb.N was markedly decreased with cinacalcet treatment (P < 0.001) and trabecular spacing (Th.Sp) markedly increased (P < 0.01). The decrease in trabecular bone was supported by an increase in osteoclast surface/BS (Oc.S/BS) in the U+Cin group (7.94 ± 1.29%) compared with normal rats (2.20 ± 0.14%, P < 0.01), UC rats (4.38 ± 0.89%), and with rats treated with paricalcitol (3.12 ± 0.62%, P < 0.05). OS, while higher than in normal rats, was decreased with cinacalcet treatment compared with UC rats and U+Par animals (P < 0.05). Importantly, BFRs and mineral apposition rates in all three uremic groups, while higher than normal (P < 0.01), did not differentiate from each other.

Table 2.

Bone histomorphometry

| Normal (n = 4) | UC (n = 5) | U + Par (n = 6) | U + Cin (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV/TV, % | 21.5 ± 2.4 | 23.9 ± 1.4 | 19.7 ± 1.7e | 10.5 ± 1.2a,g |

| BS, mm | 83.5 ± 4.0 | 89.1 ± 6.5 | 77.4 ± 8.8d | 40.7 ± 5.1a,g |

| Tb.Th, μm | 65.7 ± 4.7 | 71.9 ± 2.1 | 71.2 ± 1.3 | 64.2 ± 3.0 |

| Tb.N, 1/mm2 | 3.26 ± 0.26 | 3.32 ± 0.16 | 2.76 ± 0.21d | 1.62 ± 0.15a,g |

| Tb.Sp, μm | 246.6 ± 23.7 | 232.3 ± 15.5 | 303.4 ± 32.3e | 588.8 ± 59.0a,h |

| Oc. S/BS, % | 2.20 ± 0.14 | 4.38 ± 0.89 | 3.12 ± 0.62f | 7.94 ± 1.29h |

| OS, % | 1.55 ± 0.43 | 17.46 ± 5.21i | 11.24 ± 3.39 | 5.25 ± 1.15c |

| BFR, μm/day | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 1.01 ± 0.21h | 0.99 ± 0.14g | 0.70 ± 0.07h |

| MAR, μg/day | 1.73 ± 0.28 | 4.35 ± 0.56h | 4.65 ± 0.36g | 3.79 ± 0.09g |

Values are means ± SE; n = number of rats. BV/TV, bone V/tissue; BS, bone surface; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular spacing; OS, osteoid surface; BFR, bone formation rate; MAR, mineral apposition rate.

P < 0.001 vs. UC.

P < 0.01 vs. UC.

P < 0.05 vs. UC using ANOVA and Tukey posttest.

P < 0.001 vs. U + Cin,

P < 0.01 vs. U + Cin,

P < 0.05 vs. U + Cin using ANOVA and Tukey posttest.

P < 0.001 vs. normal,

P < 0.01 vs. normal,

P < 0.05 vs. normal comparing normal with uremic groups, using nonpaired t-test.

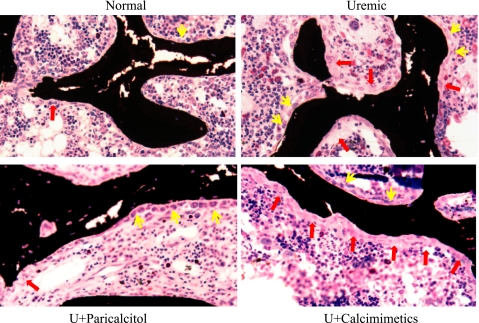

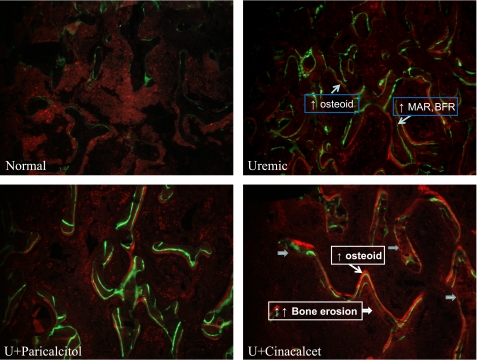

Figure 6 shows von Kossa staining of tibiae from all four groups of rats and again highlights the differences in bone histomorphometry seen in U+Cin rats, particularly the marked increase in osteoclastic surface. Bone turnover in the proximal tibial metaphyses is shown in Fig. 7. Tibiae from UC rats displayed dramatic increases in the osteoid seam (bright red stain), which represents undermineralized tissue. The double fluorescent labels on the BS indicate increased bone formation. Compared with normal animals, U+Par rats also displayed an increased osteoid seam and increased bone formation, but to a much lesser degree than the UC rats. U+Cin rats had lower osteoid formation but their rate of bone formation was similar to UC rats. There were dramatic increases in scalloped surface with an absence of labeling, indicating an increase in bone resorption compared with other groups. RatLaps, COOH-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen, are released into the circulation when bone matrix is degraded during osteoclastic bone resorption, and were assessed in serum. The RatLaps results supported the bone histomorphometric analyses showing increased osteoclastic activity in cinacalcet-treated rats (N: 7.9 ± 0.4, UC: 39.0 ± 8.4, U+Par: 27.6 ± 4.0, and U+Cin: 67.7 ± 23.4 ng/ml).

Fig. 6.

von Kossa and tetrachrome staining of 5-μm sections of proximal tibial metaphyses from normal and uremic rats treated with vehicle, paricalcitol, or cinacalcet. At the onset of uremia, rats were given vehicle (100 μl of propylene glycol), paricalcitol (0.16 μg/kg body wt ip, 3 × wk), or cinacalcet (15 mg/kg body wt daily by gavage) for 6 wk. Yellow arrows indicate osteoblast surface and red arrows indicate osteoclast surface.

Fig. 7.

Fluorochrome bases analysis of 8-μm sections of proximal tibial metaphyses from normal and uremic rats treated with vehicle, paricalcitol, or cinacalcet. At the onset of uremia, rats were given vehicle (100 μl of propylene glycol), paricalcitol (0.16 μg/kg body wt ip, 3 × wk), or cinacalcet (15 mg/kg body wt daily by gavage) for 6 wk. Normal rats served as control. On days 10 and 2 before death, the rats received an injection of calcein (10 mg/ml in PBS, 0.1 ml/100 g body wt). Bright red staining represents the osteoid seam (undermineralized tissue). Single and double green fluorescent labels on the bone surface represent increased bone formation.

DISCUSSION

Calcimimetic drugs are allosteric activators of the CaR and reduce PTH by increasing the sensitivity of the parathyroid gland CaR to ambient Ca (14, 27). The calcimimetic, cinacalcet, is used to treat SH in dialysis patients (CKD 5) and has been shown to reduce the Ca × P product by ∼13% (3). Little is known, however, about the effects of cinacalcet on predialysis CKD patients (stages 3–4). We therefore studied 5/6th nephrectomized rats with Cr clearances “equivalent” to patients with CKD 3–4 to compare the effects of cinacalcet and the VDRA, paricalcitol, on serum chemistries, urinary P and Ca, serum PTH, serum 1,25-(OH)2D3, serum FGF-23, and bone histomorphometric measurement of bone architecture and surface-based bone turnover.

In the current study, cinacalcet treatment significantly decreased serum Ca. The decrease in PTH by cinacalcet would account, at least in part, for this decrease. Twenty-four-hour urinary Ca excretion, however, was significantly higher in U+Cin rats compared with all other groups. Increases in urinary Ca excretion in patients treated with cinacalcet have also been reported (6, 7) and are probably due to the activation of the renal CaR. In addition, 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels are markedly lower in both the cinacalcet- and paricalcitol-treated rats compared with UC rats. The lower levels of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in the cinacalcet rats could also play a role in the hypocalcemia seen in this group. While PTH is also suppressed in the U+Par group, the actions of this VDRA on intestine and bone are likely responsible for the maintenance of serum Ca levels. Thus, the decrease in serum Ca seen with cinacalcet treatment is most likely due to the combination of a decrease in serum PTH, lower levels of 1,25-(OH)2D3, and an increase in urinary Ca excretion. Serum P was markedly increased in cinacalcet-treated rats, a response not seen in patients on chronic hemodialysis (stage 5 CKD) (3). Even with the hypocalcemia in this group, the sharp increase in serum P resulted in a marked elevation in the Ca × P product. The hyperphosphatemia could have resulted from several things. First, the uremic rats in this study are equivalent to CKD stage 3–4 and still have renal function, so the suppression of PTH seen with cinacalcet treatment might have caused a decreased urinary P excretion leading to P retention. PTH levels in paricalcitol-treated rats, however, are also similarly decreased, but there was no increase in serum P. These results are supported by studies in predialysis patients (CKD 3–4) treated with paricalcitol (8). Another possibility for this discrepancy could be changes in serum FGF-23. FGF-23 is a member of the fibroblast growth factor family and has an important role in P metabolism (32, 33, 37). FGF-23 promotes phosphaturia by inhibiting P reabsorption in the proximal tubule by inducing endocytosis of the sodium-phosphate transporter, NaPi IIa (1). Vitamin D compounds are one of the most important activators of FGF-23 (21, 31), and, as expected, serum FGF-23 levels were increased in paricalcitol-treated rats in this study. Conversely, the decrease in serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 seen in cinacalcet-treated rats may explain why serum FGF-23 was decreased in these animals. The increase in FGF-23 in U+Par rats could explain, at least in part, why these rats did not get hyperphosphatemia. On the other hand, the decrease in FGF-23 levels in cinacalcet-treated rats might contribute to the hyperphosphatemia seen in this group. However, while the decrease in 1,25-(OH)2D3 might indirectly promote the hyperphosphatemia by lowering serum FGF-23 in cinacalcet-treated rats, a decrease in 1,25-(OH)2D3 would also reduce intestinal P absorption thereby reducing the FLPO4. This did not happen. Perhaps a more important contributor to the increased FLPO4 in this group might be the increase bone resorption. The resulting bone mobilization of P may be a key cause of the increased FLPO4 seen with cinacalcet treatment.

In this study, 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels are significantly lower in paricalcitol- and cinacalcet-treated rats compared with UC animals. Cinacalcet decreases serum PTH and increases serum P, both of which inhibit 1,25-(OH)2D3 production (17) and could explain the decrease in serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 seen with cinacalcet treatment. This decrease in serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 may play a role in the bone abnormalities seen in cinacalcet-treated rats. We expected serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels to be lower in paricalcitol-treated rats since VDRA treatment is known to decrease serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 by activating the 24 hydroxylase (11), and they were. Even though 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels are low in rats receiving paricalcitol, treatment with this VDRA essentially replaces 1,25-(OH)2D3, thereby avoiding possible detrimental effects seen with decreased 1,25-(OH)2D3.

The role of vitamin D in bone remodeling is complex since vitamin D affects both bone resorption and formation. 1,25-(OH)2D3 promotes bone formation by inhibiting the proliferation of osteoblast precursors and promoting their differentiation into a more mature phenotype (15). In studies in MG-63 cells, an osteoblastic-like cell line, our lab found that paricalcitol had the same effect as 1,25-(OH)2D3 in inducing the VDR, osteocalcin, alkaline phosphatase, and proliferation (13). Thus, paricalcitol seems to have similar effects on bone as its parent compound, 1,25-(OH)2D3. Further studies in vivo in uremic rats examined the effect of paricalcitol on both the prevention (prophylactic treatment from the onset of uremia) and treatment (2 mo after the establishment of SH) of SH and bone disease (42). Paricalcitol was successful in both preventing and suppressing SH. In prophylactic studies, UC rats showed a threefold increase in cancellous bone mass and marked increases in eroded surface, mineralization lag time, BFR, and cortical bone porosity compared with normal rats. Paricalcitol ameliorated these changes. After SH was established, bone indexes continued to worsen in UC animals, but paricalcitol treatment improved bone histology by reducing cortical bone porosity, woven bone formation, mineralization lag time, and BFR.

While PTH levels in the cinacalcet and paricalcitol groups were similar 24 h after the last treatment, PTH values can vary greatly after cinacalcet treatment depending on when the sample is drawn. In the present study, PTH levels dropped to 24.1 pg/ml 4 h after cinacalcet treatment, but by 20 h had risen to 251.5 pg/ml. This is not the case with vitamin D compounds, which are known to cause a more prolonged suppression of PTH (35). It is unclear whether there is any relevance in the differences in the profile of PTH suppression between these two compounds and what effect this might have on bone.

It is not clear what prolonged treatment with cinacalcet might have on bone in CKD patients, but both osteoblasts and osteoclasts possess the CaR (18, 44). In osteoblasts, increased extracellular Ca and CaR agonists stimulate chemotaxis and increased proliferation (44). The release of high concentrations of extracellular Ca due to resorbing activity inhibits bone resorption by causing osteoclast retraction and detachment from the bone surface (BS) (9).

Recent studies also show that the CaR is also involved in osteoclast differentiation and apoptosis (26). In these studies, Mentaverri et al. (25) demonstrated a 70% decrease in osteoclastic differentiation in RANKL-stimulated bone marrow cells from CaR−/− mice demonstrating that the CaR is intimately involved in osteoclast differentiation.

Recently, Dvorak et al. (12) showed that increased signaling by the CaR in mature osteoblasts can enhance bone resorption. This group generated transgenic mice with a constitutively active mutant CaR targeted to mature osteoblasts to study the effect of over activity of the CaR, in this cell type, on bone. Their results were similar to our results in cinacalcet-treated rats. Over activity of the osteoblastic CaR reduced bone volume and density and diminished the trabecular network. Bone loss was caused by an increase in the number as well as the activity of osteoclasts. In addition, BFRs in their study were also unchanged. RANKL was significantly increased in femurs from mice overexpressing the CaR, as well, likely driving the enhanced osteoclastogenesis. While we did not measure RANKL, an elevation in this ligand could be responsible for the increased Oc.S/BS seen in cinacalcet-treated rats.

With cinacalcet treatment, we see no change in bone formation but a marked decrease in bone volume and trabecular number and an increase in Th.Sp, clearly indicating that there is negative bone balance occurring in cinacalcet-treated rats. The increase in Oc.S/BS suggests that increased bone resorption exceeds bone formation and therefore results in bone loss. There were also greater areas of BS lined with osteoclasts observed in von Kossa and tetrachrome double-stained sections of tibiae from these animals. We were surprised to find similar bone resorption but decreased bone volume in the cinacalcet-treated rats since PTH was considerably lower than in UC rats. In addition, these observations are in contrast to those reported in hemodialysis patients. Malluche et al. (24) found that after a year of cinacalcet treatment, bone turnover and tissue fibrosis had decreased in most of the cinacalcet-treated dialysis patients in their study. After a 52-wk treatment period, Yajima and colleagues (43) also saw a decrease in fibrosis and bone turnover as well. It is unclear why there is such a difference in the results seen in rats with renal function equivalent to CKD 3–4 and in hemodialysis patients. Nguyen-Yamamoto and collaborators, however, recently reported results from a study comparing the effects of cinacalcet and VDRAs on PTH and mineral homeostasis in mice with a targeted deletion of the 25-hydroxyvitamin d-1α-hydroxylase (abstract ASN Sa-FC389, 2008). They found that paricalcitol and doxercalciferol, another VDRA, produced sustained decreases in serum PTH while the decrease in PTH after cinacalcet treatment was cyclic. The two VDRAs normalized serum Ca and P and improved mineralization of osteomalacic bones while cinacalcet did not. Hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, decreased 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels, and cinacalcet itself may all play a role in the detrimental effects on bone seen in this study. A potential direct effect of cinacalcet on bone requires further investigation.

In conclusion, due to its effects on bone and to the severe hyperphosphatemia it induces, we believe that cinacalcet should not be used in patients with CKD without further detailed studies.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by Washington University Research in Renal Diseases Grant 31030, Abbott Pharmaceuticals, and the WUCKDR O'Brien Center Grant P30DK079333.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Slatopolsky received grant support and honoraria from Genzyme and Abbott Pharmaceutical. E. Slatopolsky and Washington University may receive income based on a license of related technology by the University of Wisconsin.

Present address of M. Tokumoto: Kyushyu Dental College, Fukuoka, Japan.

Present address of H. Nakamura: Dept. of Nephrology, Showa Univ. School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bacic D, Wagner CA, Hernando N, Kaissling B, Biber J, Murer H. Novel aspects in regulated expression of the renal type IIa Na/Pi cotransporter. Kidney Int Suppl 91: S5–S12, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bikle DD. Clinical counterpoint: Vitamin D: new actions, new analogs, new therapeutic potential. Endocr Rev 13: 765–784, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Block GA, Martin KJ, de Francisco A, Turner SA, Avram MM, Suranyi MG, Hercz G, Cunningham J, Abu-Alfa AK, Messa P, Coyne DW, Locatelli F, Cohen RM, Evenepoel P, Moe SM, Fournier A, Braun J, McCary LC, Zani VJ, Olson KA, Drüeke TB, Goodman WG. Cinacalcet for secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 350: 1516–1525, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown AJ, Ritter CS, Finch JL, Morrissey J, Martin KJ, Murayama E, Nishii Y, Slatopolsky E. The noncalcemic analogue of vitamin D, 22-oxacalcitriol, suppresses PTH synthesis and secretion. J Clin Invest 84: 728–732, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown AJ, Dusso A, Lopez-Hilker S, Lewis-Finch J, Grooms P, Slatopolsky E. 1,25(OH)2D3 receptors are decreased in parathyroid glands from chronically uremic dogs. Kidney Int 35: 19–23, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Charytan C, Coburn JW, Chonchol M, Herman J, Lien YH, Liu W, Klassen PS, McCary LC, Pichette V. Cinacalcet hydrochloride is an effective treatment for secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with CKD not receiving dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 58–67, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chonchol M, Locatelli F, Abboud HE, Charytan C, de Francisco AL, Jolly S, Kaplan M, Roger SD, Sarkar S, Albizem MB, Mix TC, Kubo Y, Block GA. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of cinacalcet HCL in participants with CKD not receiving dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 197–207, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coyne D, Acharya M, Qiu P, Abboud H, Batlle D, Rosansky S, Fadem S, Levine B, Williams L, Andress DL, Sprague SM. Paricalcitol capsule for the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism in stages 3 and 4 CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 47: 263–276, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Datta HK, MacIntyre I, Zaidi M. The effect of extracellular calcium elevation on morphology and function of isolated rat osteoclasts. Biosci Rep 9: 747–751, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dunlay R, Rodriguez M, Felsenfeld AJ, Llach F. Direct inhibitory effect of calcitriol on parathyroid function (sigmoidal curve) in dialysis. Kidney Int 36: 1093–1098, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dusso AS, Negrea L, Finch J, Kamimura S, Lopez-Hilker S, Mori T, Nishii Y, Brown A, Slatopolsky E. The effect of 22-oxacalcitriol on serum calcitriol. Endocrinology 130: 3129–3134, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dvorak MM, Chen T, Orwoll B, Orwoll B, Garvey C, Chang W, Bikle DD, Shoback DM. Constitutive activity of the osteoblast Ca2+-sensing receptor promotes loss of cancellous bone. Endocrinology 148: 3156–3163, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Finch JL, Dusso AS, Pavlopoulos T, Slatopolsky EA. Relative potencies of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and 19-nor-(OH)2D2 on inducing differentiation and markers of bone formation in MG-63 cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1468–1474, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fox J, Lowe SH, Conklin RL, Nemeth EF. The calcimimetic NPS R-568 decreases plasma PTH in rats with mild and severe renal or dietary secondary hyperparathyroidism. Endocrine 10: 97–103, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franceschi RT, James WM, Zerlauth G. 1 alpha, 25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 specific regulation of growth, morphology and fibronectin in a human osteosarcoma cell line. J Cell Physiol 123: 401–409, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gogusev JT, Duchambon P, Hory BM, Giovannini M, Goureau Y, Sarfati E, Drüeke TB. Depressed expression of calcium receptor in parathyroid gland tissue of patients with hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int 51: 328–336, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henry HL, Norman AW. Vitamin D: metabolism and biological actions. Annu Rev Nutr 4: 493–520, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kameda T, Mano H, Yamada Y, Takai H, Amizuka N, Kobori M, Izumi N, Kawashima H, Ozawa H, Ikeda K, Kameda A, Hakeda Y, Kumegawa M. Calcium-sensing receptor in mature osteoclasts, which are bone resorbing cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 245: 419–422, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kestenbaum B, Sampson JN, Rudser KD, Patterson DJ, Seliger SL, Young B, Sherrard DJ, Andress DL. Serum phosphate levels and mortality risk among people with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 520–528, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kifor O, Moore FD, Wang P, Goldstein M, Vassilev P, Kifor I, Hebert SC, Brown EM. Reduced immunostaining for the extracellular Ca sensing receptor in primary and uremic secondary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81: 1598–1606, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kolek OI, Hines ER, Jones MD, LeSueur LK, Lipko MA, Kiela PR, Collins JF, Haussler MR, Ghishan FK. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates FGF23 gene expression in bone: the final link to a renal-gastrointestinal-skeletal axis that controls phosphate transport. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289: G1036–G1042, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Korkor AB. Reduced binding of [3H] 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the parathyroid glands of patients with renal failure. N Engl J Med 316: 1577–1582, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindberg JS, Moe SM, Goodman WG, Coburn JW, Sprague SM, Liu W, Blaisdell PW, Brenner RM, Turner SA, Martin KJ. The calcimimetic AMG 073 reduces parathyroid hormone and calcium × phosphorus product in secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int 63: 248–254, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Malluche HH, Monier-Faugere MC, Wang G, Frazã OJM, Charytan C, Coburn JW, Coyne DW, Kaplan MR, Baker N, McCary LC, Turner SA, Goodman WG. An assessment of cinacalcet HCl effects on bone histology in dialysis patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Clin Nephrol 69: 269–278, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mentaverri R, Yano S, Chattopadhyay N, Petit L, Kifor O, Kamel S, Terwilliger EF, Brazier M, Brown EM. The calcium sensing receptor is directly involved in both osteoclast differentiation and apoptosis. FASEB J 20: 2562–2564, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Merke J, Hugel U, Zlotsowski A, Szabó A, Bommer J, Mall G, Ritz E. Diminished parathyroid 1,25(OH)2D3 receptor in experimental uremia. Kidney Int 32: 350–353, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nemeth EF, Steffey ME, Hammerland LG. Calcimimetics with potent and selective activity on the parathyroid calcium receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 4040–4045, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parfitt AM. The hyperparathyroidism of chronic renal failure: a disorder of growth. Kidney Int 52: 3–9, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quarles LD, Sherrard DJ, Adler S, Rosansky SJ, McCary LC, Liu W, Turner SA, Bushinsky DA. The calcimimetic AMG 073 as a potential treatment for secondary hyperparathyroidism of end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 575–583, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russell JD, Lettieri D, Sherwood LM. Suppression by 1,25-(OH)2D of transcription of the parathyroid hormone gene. Endocrinology 119: 2864–2866, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saito H, Maeda A, Ohtomo S, Hirata M, Kusano K, Kato S, Ogata E, Segawa H, Miyamoto K, Fukushima N. Circulating FGF-23 is regulated by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and phosphorus in vivo. J Biol Chem 280: 2543–2549, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, Muto T, Hino R, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Nakahara K, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res 19: 429–435, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shimada T, Katitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Tomizuka K, Yamashita T. Targeted ablation of FGF-23 demonstrates essential physiological role for FGF-23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest 113: 561–568, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Silver J, Russell J, Sherwood LM. Regulation by vitamin D metabolites of messenger RNA for pre-pro-parathyroid hormone in isolated bovine parathyroid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82: 4270–4273, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Silver J, Naveh-Many T, Mayer H, Schmelzer HJ, Popovtzer MM. Regulation by vitamin D metabolites of parathyroid hormone gene transcription in vivo in the rat. J Clin Invest 78: 1296–1301, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Silver J, Bar Sela S, Naveh-Many T. Regulation of parathyroid cell proliferation. Curr Op Nephrol Hyperten 6: 321–326, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sitara D, Razzaque MS, Hesse M, Yoganathan S, Taguchi T, Erben RG, Jüppner H, Lanske B. Homozygous ablation of fibroblast growth factor-23 results in hyperphosphatemia and impaired skeletogenesis, and reverses hypohphosphatemia in Phex-deficient mice. Matrix Biol 23: 421–432, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Slatopolsky E, Weerts C, Thielan J, Horst R, Harter H, Martin K. Marked suppression of secondary hyperparathyroidism by intravenous administration of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol in uremic patients. J Clin Invest 74: 2136–2143, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Slatopolsky E, Finch J, Ritter C, Denda M, Morrissey J, Brown A, DeLuca H. A new analog of calcitriol, 19-nor-1,25-(OH)2D2, suppresses parathyroid hormone secretion in the absence of hypercalcemia. Am J Kidney Dis 26: 852–860, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Slatopolsky E, Finch J, Denda M, Ritter C, Zhong M, Dusso A, MacDonald PN, Brown AJ. Phosphorus restriction prevents parathyroid gland growth. High phosphorus directly stimulates PTH secretion in vitro. J Clin Invest 97: 2534–2540, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Slatopolsky E, Brown AJ, Dusso AS. Pathogenesis of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int 56, Suppl 73: S14–S19, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Slatopolsky E, Cozzolino M, Lu Y, Finch J, Dusso A, Staniforth M, Wein Y, Webster J. Efficacy of 19-nor-1,25-(OH)2D2 in the prevention and treatment of hyperparathyroid bone disease in experimental uremia. Kidney Int 63: 2020–2027, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yajima A, Akizawa T, Tsukamoto Y, Kurihara S, Ito A. Impact of cinacalcet hydrochloride on bone histology in patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. Ther Apher Dial 1: S38–S43, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yamaguchi T, Chattopadhyay N, Kifor O, Butters RR, Jr, Sugimoto T, Brown EM. Mouse osteoblastic cell line (MC3Tc-E1) expresses extracellular calcium (Ca2=o)-sensing receptor and its agonists stimulate chemotaxis and proliferation of MC3T3–E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res 13: 1530–1538, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]