Abstract

Kidney fibrosis, a typical characteristic of chronic renal disease, is associated with tubular epithelial cell apoptosis. The results of our recent studies have shown that Omi/HtrA2 (Omi), a proapoptotic mitochondrial serine protease, performs a crucial function in renal tubular epithelial apoptotic cell death in animal models of acute kidney injury, including cisplatin toxicity and ischemia-reperfusion insult. However, the role of Omi in tubulointerstitial disease-associated fibrosis in the kidney remains to be clearly defined. We evaluated the potential function and molecular mechanism of Omi in ureteral obstruction-induced kidney epithelial cell apoptosis and fibrosis. The mice were subjected to unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) via the ligation of the left ureter near the renal pelvis. UUO increased the protein level of Omi in the cytosolic fraction of the kidney, with a concomitant reduction in the mitochondrial fraction. UUO reduced the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), a substrate of Omi, and pro-caspase-3, whereas it increased cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (cleaved PARP) and the number of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells. When mice were treated with ucf-101, an inhibitor of the proteolytic activity of Omi (6.19 μg/day ip), on a daily basis beginning 2 days before UUO and continuing until the end of the experiment, the Omi inhibitor protected XIAP cleavage after UUO and reduced the increment of PARP cleavage and the numbers of TUNEL-positive cells. Furthermore, the Omi inhibitor significantly attenuated UUO-induced increases in fibrotic characteristics in the kidney, including the atrophy and dilation of tubules, expansion of the interstitium, and increases in the expression of collagens, α-smooth muscle actin, and fibronectin. In conclusion, Omi/HtrA2 is associated with apoptotic signaling pathways in tubular epithelial cells activated by unilateral ureteral obstruction, thereby resulting in kidney fibrosis.

Keywords: XIAP, kidney fibrosis, ucf-101, α-SMA

urinary tract obstruction results in renal functional loss and morphological changes including hydronephrosis, infiltration of leukocytes, tubular atrophy, and dilation, as well as increased interstitial fibrosis (21). This disease, as well as its corresponding rodent model, unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO), leads to tubulointerstititial disease and fibrosis, both of which are common components of a number of renal diseases and important contributors to chronic progressive disease leading to end-stage renal disease. An accumulating body of evidence suggests that tubular cell apoptosis contributes to fibrotic kidney changes that occur in conjunction with ureteral obstruction. Stretch, ischemia, and oxidative stress followed by UUO are primary causes of tubular cell apoptosis. Increased apoptosis and stress activate cellular infiltration, interstitial cell proliferation, and interstitial fibrosis (8, 21).

Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is mediated by either the extrinsic pathway, which involves the activation of death receptors on the cell surface, or the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway, which involves the release of several proapoptotic factors from the mitochondria to the cytosol, thereby inducing caspase activations (11). The process of apoptosis is highly regulated and involves several proapoptotic and antiapoptotic proteins. The antiapoptotic proteins include inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAP) such as the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), c-IAP1, c-IAP2, and survivin (7, 35). XIAP directly inhibits caspases and reduces apoptotic cell death.

Omi/HtrA2 (Omi) is a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial serine protease that is released from the mitochondria into the cytoplasm upon the induction of apoptosis (5, 36). Once in the cytoplasm, Omi degrades XIAP and a variety of other substrates to promote caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death (5, 36). We have previously reported that cisplatin treatment induces Omi activation in kidney tubular epithelial cells and facilitates cell death (4). Furthermore, ucf-101, a specific inhibitor of the proteolytic activity of Omi, proved able to protect the kidneys of mice and zebrafish against cisplatin toxicity (13). The results of other studies have demonstrated that Omi activation can also regulate apoptotic cell death in focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (1, 33), as well as myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (2, 24). The role of Omi in tubulointerstitial disease and associated fibrosis in the kidney, however, has yet to be clearly defined. In this study, we attempted to determine whether Omi may play a causative role in apoptosis resulting in tubulointerstitial reaction, as well as in the fibrosis that occurs in a mouse model of UUO-induced kidney injury. Our results clearly showed that Omi performs a pivotal role in the development and progression of UUO-induced kidney impairment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation.

Experiments were conducted using 8-wk-old male BALB/c mice. The mice were permitted free access to water and standard mouse chow. In all cases, the studies were approved by the Kyungpook National University Institution Animal Care and Use Committee. Each animal group consisted of at least four mice. UUO was conducted as described previously (28). The mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg body wt ip; catalog no. P3761; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The left kidney was exposed through the site of the left flank incision. The left ureter was obstructed completely near the renal pelvis using a 6-0 silk tie. Sham-operated mice underwent the same surgical procedure except for the ureter ligation. The animals were treated with either ucf-101 (6.19 μg/day ip; catalog no. 496150; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) or vehicle, beginning 2 days before the operation, and continued until the end of the experiment. Kidneys were either perfusion-fixed in PLP (4% paraformaldehyde, 75 mM l-lysine, 10 mM sodium periodate; Sigma) for histological studies, or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for biochemical studies. PLP-fixed kidneys were washed with PBS three times for 5 min each, embedded in oxytetracycline compound (Sakura FineTek, Torrance, CA) at −20°C or in paraffin at room temperature, and then cut into 4-μm frozen sections or 2-μm paraffin sections using a cryotome (CM1850; Leica, Bensheim, Germany) or a microtome (catalog no. RM2165; Leica), respectively.

Collagen deposition.

To evaluate collagen deposition, the paraffin-sections were stained with Masson's trichrome in accordance with standard protocols. Images were collected with a digital camera (Carl Zeiss, Munich, Germany). Each experimental animal group consisted of more than four mice. Collagen deposition was analyzed in 10 random fields (0.1 mm2/field) using LabWorks 4.5 software (Ultra-Violet Products, Cambridge, UK).

Western blot analysis.

Western blot analyses were conducted as previously described (14–16, 18, 19), using various antibodies against the following proteins: Omi/HtrA2 (1:1,000 dilution, catalog no. NB110–57068; Novus, Littleton, CO), fibronectin (1:2,500 dilution; catalog no. sc-8422; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; 1:5,000 dilution; catalog no. A2547; Sigma), β-actin (1:5,000 dilution; catalog no. A5316; Sigma), manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD; 1:2500 dilution; catalog no. 574596; Calbiochem), copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD; 1:2,500 dilution; catalog no. AB1237; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), XIAP (1:1,000 dilution; catalog no. 54174; AnaSpec, San Jose, CA), pro-cysteine-aspartic acid protease (pro-caspase-3; 1:500 dilution; catalog no. sc-7148; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (cleaved PARP; 1:2,500 dilution; catalog no. 9544; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). Cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were separated as described previously (14, 16, 18, 19). The densities of the immunoblots were analyzed with LabWorks 4.5 software (Ultra-Violet Products).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay.

The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols, as previously described (15, 20). The sections were observed under an LSM 5 confocal microscope or an Axioplan-2 epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss). Images were collected with a digital camera (Carl Zeiss) and merged using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software. TUNEL-positive cells were counted in 10 random fields (0.1 mm2/field) per kidney.

Caspase-3 activity assay.

The caspase-3 activity assay was conducted using a Caspase-3 Fluorescent Assay Kit (catalog no. 2220–1; Peptron, Daejeon, Korea) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols. In brief, the frozen kidneys were homogenized in a lysis buffer. The homogenates were then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min. The supernatants (containing ∼250 μg total protein) were incubated with 50 mM of the caspase-3 substrate (acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-amino-4-methylcoumarin, Ac-DEVD-AMC) in a 2× reaction buffer in a 96-well plate for 1 h at 37°C. The fluorescence was read on a Molecular Devices SPECTRAmax Gemini spectrofluorometer using a 360-nm excitation and 460-nm emission filter. A substrate alone was served as a related control.

Immunofluorescence of α-SMA.

Immunofluorescence staining was conducted as previously described (15, 17, 18), using a polyclonal anti-α-SMA (1:200 dilution; Sigma) antibody. The sections were visualized under an Axioplan-2 epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss). Images were collected with a digital camera (Carl Zeiss). The α-SMA-positive area was counted in 10 random fields (0.1 mm2/field) of the kidneys.

Statistics.

Results were expressed as the means ± SE. Statistical differences among groups were calculated using ANOVA followed by least-significant difference post hoc comparisons using the SPSS 12.0 program. Differences between groups were considered statistically significant at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

UUO induces apoptotic tubular epithelial cell death and fibrosis.

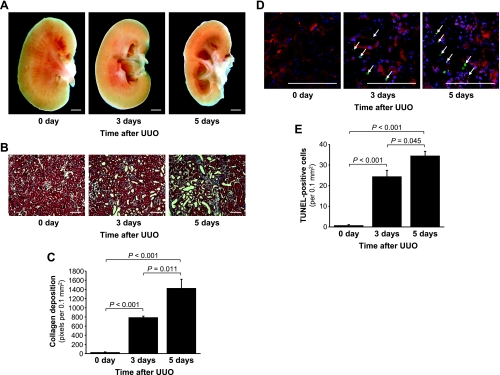

After UUO, the renal pelvic space in obstructed kidneys was gradually expanded, whereas the contents of the cortex and medulla gradually decreased (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, UUO resulted in the expansion of the interstitial area and tubular dilation and atrophy (Fig. 1B). Because extracellular matrix accumulation is a typical characteristic of kidney fibrosis, we determined the deposition of collagens using Masson's trichrome staining. Collagen deposition increased in the kidneys after UUO (Fig. 1, B and C), which was consistent with the results of previous studies (25, 31). Also consistent with the results of other studies, the obstructed kidneys evidenced tubular atrophy, flattening, and the dilation and accumulation of collagens in the interstitium (Fig. 1, B and C). Collagen deposition (Fig. 1, B and C) and TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 1, D and E) increased markedly over 5 days after UUO.

Fig. 1.

Collagen deposition and apoptosis in mouse kidneys subjected to unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO). The left kidneys of male BALB/c mice were subjected to UUO as described in materials and methods. Three or five days after UUO, the kidneys were harvested, hemisected (A), and cut into 2-μm thickness for Masson trichrome staining (B). The blue color indicates collagen. C: collagen deposition was quantified by counting the number of blue pixels in a 0.1-mm2 field of the kidney section using LabWorks analysis software (10 fields/kidney). D: apoptosis was evaluated via a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. The arrows indicate TUNEL-positive cells. E: TUNEL-positive cells were quantified as the number of positive nuclei in a 0.1-mm2 field of the kidney section using LabWorks analysis software (10 fields/kidney). 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was used to stain the nuclei blue. The red color emitted at 650–710 nm was used to detect general morphology without any treatment. Day 0 indicates before UUO. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). Scale bars: 1 mm in A and 100 μm in B and D.

UUO results in Omi release from the mitochondria into the cytosol, XIAP degradation, and apoptosis.

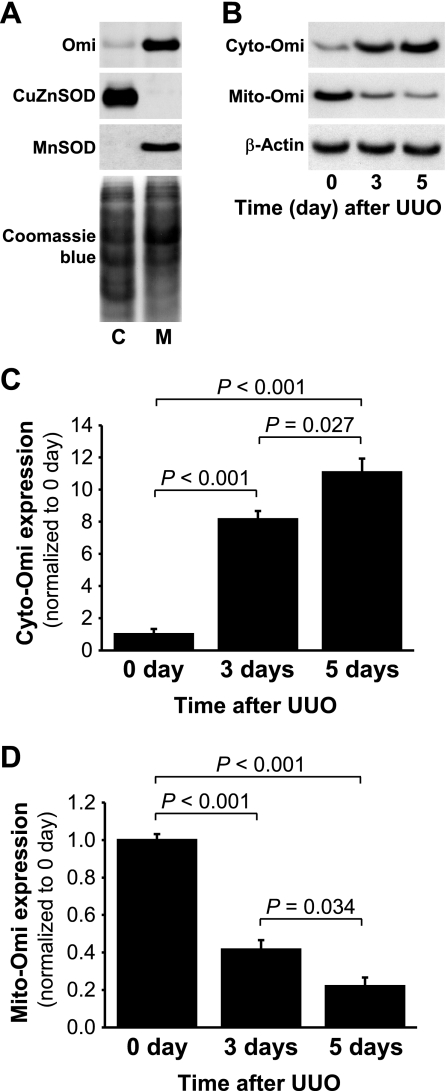

To evaluate the localization of Omi, we isolated cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. These fractions were probed via Western blot analysis using antibodies against CuZnSOD, a cytosolic-specific antioxidant protein, and MnSOD, a mitochondrial-specific antioxidant protein (Fig. 2A). CuZnSOD and MnSOD were expressed specifically in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions, respectively (Fig. 2A). In the normal kidneys, Omi protein was located almost exclusively in the mitochondria, with very little or none present within the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). Three and five days after UUO, cytosolic Omi (cyto-Omi) expression increased significantly (Fig. 2, B and C), whereas mitochondrial Omi (mito-Omi) expression was reduced (Fig. 2, B and D), thereby indicating that UUO resulted in the release of Omi protein from the mitochondria into the cytosol.

Fig. 2.

Activation of Omi/HtrA2 (Omi) protease in kidneys subjected to UUO. Kidneys were harvested at 0, 3, or 5 days after the UUO induction. A: Omi, copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (CuZnSOD) in the cytosolic fraction (C), and manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) expression in the mitochondrial fraction (M) were determined by Western blot analysis using antibodies against these proteins. Coomassie blue staining was used to detect proteins on the SDS-PAGE gels. B: cytosolic Omi (cyto-Omi) in the cytosolic fraction and mitochondrial Omi (mito-Omi) in the mitochondrial fraction expressions were evaluated by Western blot analysis using antibodies against those proteins, with β-actin used as a control to ensure equal loading of cytosolic fractions (C and D). The protein bands were quantified using LabWorks analysis software. Values are means ± SE (n = 4).

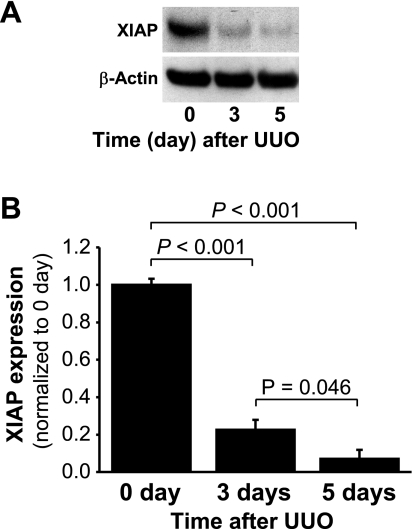

In the cytosol, Omi binds to and cleaves XIAP, a very potent inhibitor of caspase-3 and apoptosis (5, 34, 36). Caspase-3, in turn, cleaves PARP to facilitate cellular disassembly and apoptosis (9, 26). We determined that the levels of XIAP protein were reduced significantly after UUO compared with the controls (Fig. 3, A and B), as expected considering the increase in cytosolic Omi with UUO.

Fig. 3.

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) expression in the kidneys subjected to UUO. Kidneys were harvested 0, 3, or 5 days after UUO. A: XIAP expression in the whole kidney lysate was determined by Western blot analysis using antibodies against this protein, with β-actin utilized as a loading marker. B: protein bands were quantified using LabWorks analysis software. Values are means ± SE (n = 4).

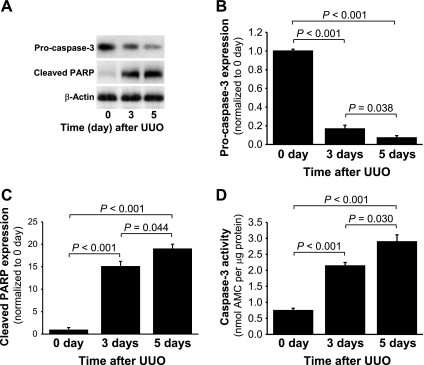

Pro-caspase-3 expression also decreased over time after UUO (Fig. 4, A and B), with associated increases in caspase-3 activity (Fig. 4D). Caspase-3 activation results in the cleavage of PARP, which is a specific substrate for this protease (Fig. 4, A and C). These results clearly demonstrate that UUO-induced apoptosis is associated with the release of Omi to the cytosol, XIAP degradation, caspase-3 activation, and PARP cleavage.

Fig. 4.

Pro-caspase-3, cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (cleaved PARP) expression, and caspase-3 activity in the kidneys subjected to UUO. Kidneys were harvested 0, 3, or 5 days after UUO. A: pro-caspase-3 and cleaved PARP expressions in the whole kidney lysate were evaluated via Western blot analysis using antibodies against these proteins, with β-actin used as a loading marker. B and C: protein bands were quantified using LabWorks analysis software. D: caspase-3 activity in the whole kidney lysate was measured using a Caspase-3 Fluorescent Assay Kit. Acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Ac-DEVC-AMC) was used as a substrate of the caspase-3 enzyme. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). AMC, 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin.

Ucf-101 attenuates XIAP degradation, caspase-3 activation, and PARP cleavage following UUO.

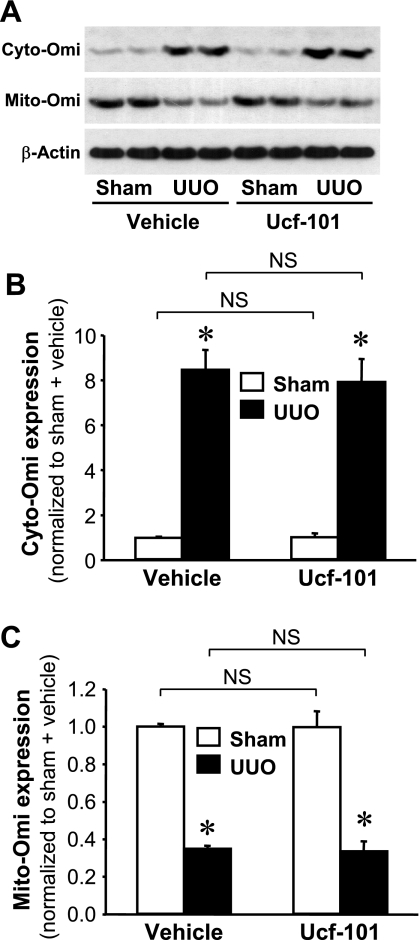

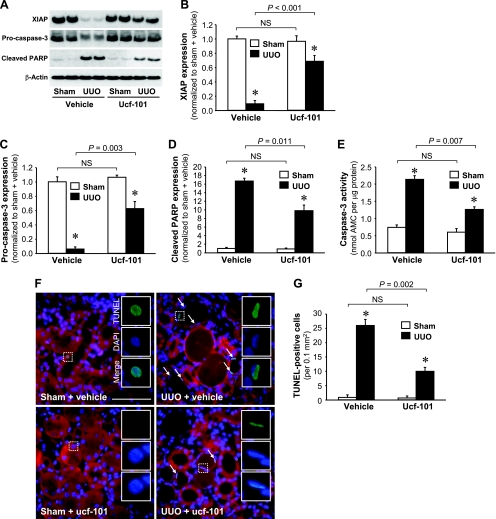

To determine whether Omi activation is important for the apoptosis that follows UUO, mice were treated with ucf-101, an inhibitor of the proteolytic activity of Omi (5, 13). The administration of ucf-101 did not prevent the mobilization of Omi from the mitochondria to the cytosol after UUO (Fig. 5, A–C). However, ucf-101 did attenuate the degradation of XIAP (Fig. 6, A and B), the degree of pro-caspase-3 loss (Fig. 6, A and C), PARP cleavage (Fig. 6, A and D), and the activity of caspase-3 (Fig. 6E). The increases in the numbers of TUNEL-positive cells noted in conjunction with UUO were inhibited significantly by the administration of ucf-101, but not as the result of vehicle treatment (Fig. 6, F and G). These data clearly demonstrated that the inhibition of Omi activation protects the kidney against UUO-induced apoptosis via the inhibition of the downstream effectors of Omi: XIAP degradation, caspase-3 activation, and finally PARP cleavage.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ucf-101 on Omi release into the cytoplasm by UUO. Male BALB/c mice were treated with either vehicle or ucf-101 (Omi inhibitor) for 5 days, beginning 2 days before and continuing for 3 days after UUO or sham-operation (sham). The kidneys were harvested 3 days after the operation. A: cyto-Omi in the cytosolic fraction and mito-Omi in the mitochondrial fraction expressions were evaluated by Western blot analysis using antibodies against these proteins, with β-actin used as an equal loading marker of the cytosolic fraction. B and C: protein bands were quantified using LabWorks analysis software. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). NS, no significant difference. *P < 0.05 vs. respective sham.

Fig. 6.

Effect of ucf-101, an inhibitor of Omi, on apoptotic signal activation and apoptosis induced by UUO. Male BALB/c mice were treated with either vehicle or ucf-101 for 5 days, beginning 2 days before UUO or sham. Kidneys were harvested 3 days after the operation. A: XIAP, pro-caspase-3, and cleaved PARP protein levels in the whole kidney lysate were determined via Western blot analysis using antibodies against these proteins, with β-actin used as an equal loading marker. B–D: protein bands were quantified using LabWorks analysis software. E: caspase-3 activity in the whole kidney lysate was measured using a Caspase-3 Fluorescent Assay Kit. Ac-DEVC-AMC was used a substrate of the caspase-3 enzyme. F: apoptosis was determined via TUNEL assay. Arrows indicate TUNEL-positive cells. White rectangular areas were separated into TUNEL, DAPI, and merged images. G: TUNEL-positive cells were quantified as the number of positive nuclei in a 0.1-mm2 field of the kidney section (10 fields/kidney). Blue indicates DAPI-stained nuclei. Red emitted at 650–710 nm is used here to view the general morphology of the tissue without any treatment. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). Scale bars = 50 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. respective sham.

Ucf-101 administration attenuates renal fibrosis after UUO.

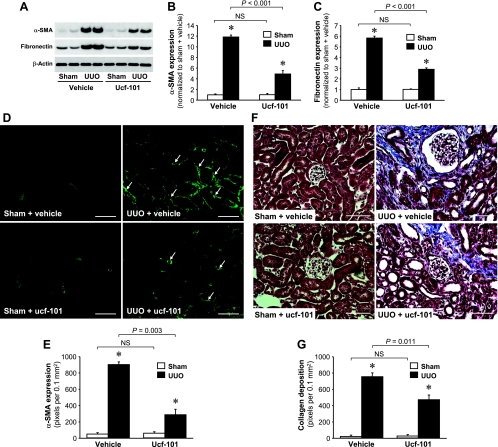

To assess whether ucf-101 attenuated kidney fibrosis after UUO, we quantitated the expression of α-SMA, a marker of myofibroblasts, and fibronectin, an extracellular matrix marker. UUO was shown to induce a dramatic increase in α-SMA (Fig. 7, A and B) and fibronectin expression in vehicle-treated animals (Fig. 7, A and C). Ucf-101 treatment significantly reduced the increases in α-SMA and fibronectin noted in association with UUO (Fig. 7, A–C). α-SMA expression was also evaluated via immunofluorescence staining using the antibody against the protein. α-SMA was prominently expressed in the interstitium and peritubule areas (Fig. 7D). The area of α-SMA expression was reduced significantly in the kidneys of ucf-101-treated mice compared with vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 7, D and E). Additionally, UUO-induced collagen deposition in the interstitium was attenuated significantly as the result of ucf-101 administration (Fig. 7, F and G).

Fig. 7.

Ucf-101 reduces α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), fibronectin expression, and collagen deposition in kidneys subjected to UUO. Male BALB/c mice were treated with either vehicle or ucf-101 beginning 2 days before UUO or sham and continuing until the kidneys were harvested 3 days after the operation. A: α-SMA and fibronectin expressions were determined via Western blot analysis using antibodies against these proteins, with β-actin used as an equal loading marker. B and C: protein bands were quantified using LabWorks analysis software. D and F: α-SMA expression and collagen deposition were determined via immunofluorescence staining and Masson's trichrome staining, respectively. D: arrows indicate α-SMA-positive cells. F: blue indicates collagen. E and G: positive areas of α-SMA and Masson's trichrome were quantified by counting the number of positive-color pixels in a 0.1-mm2 field of the kidney section using LabWorks analysis software (10 fields/kidney). Values are ± SE (n = 4). Scale bars = 50 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. respective sham.

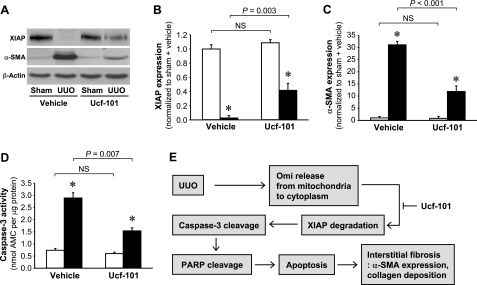

To investigate the impact of Omi inhibition in UUO-induced kidney fibrosis and apoptotic signal pathways at a later time point, we determined XIAP, α-SMA expression, and caspase-3 activity 10 days after UUO. Consistent with 3 days after UUO (Figs. 6, A, B, and E, and 7, A and B), the administration of ucf-101 significantly attenuated the decrease in XIAP expression (Fig. 8, A and B) and the increases in α-SMA expression (Fig. 8, A and C) and caspase-3 activity (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

Ucf-101 reduces XIAP, α-SMA expression, and caspase-3 activity 10 days after UUO. Male BALB/c mice were treated with either vehicle or ucf-101 beginning 2 days before UUO or sham and continuing until the kidneys were harvested 10 days after the operation. A: XIAP and α-SMA expressions were determined via Western blot analysis using antibodies against these proteins. β-Actin expression was determined to evaluate the equal loading marker of samples. B and C: protein bands were quantified using LabWorks analysis software. D: caspase-3 activity was measured using a Caspase-3 Fluorescent Assay Kit. Ac-DEVC-AMC was used a substrate of the caspase-3 enzyme. E: scheme of Omi pathway in UUO. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). Scale bars = 50 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. respective sham.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we determined that UUO results in the release of Omi from the mitochondria into the cytosol, resulting in XIAP degradation, which consequently induces apoptosis in the tubular epithelial cells, and also that the inhibition of Omi protease by ucf-101 attenuates XIAP degradation and apoptotic kidney epithelial cell death, demonstrating the attenuation of UUO-induced fibrosis in the kidney, as summarized in Fig. 8E. This indicates that the targeting of Omi protease activity may prove useful in the treatment of fibrotic kidney diseases.

The blockage of urine flow by a ureteral obstruction induces a mechanical stretching of the tubular epithelial cells and ischemia as the result of impeded blood flow, thereby resulting in tubular cell injury. The injured tubule cells generate cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species, thereby resulting in the recruitment of inflammatory cells (19, 21). These cells, in turn, generate factors that accelerate tubular epithelial cell death, leading to kidney fibrosis characterized by the accumulation of leukocytes, expansion of the interstitium, increased extracellular matrix production, and tubular atrophy and dilation. It has been previously suggested that the inhibition of tubular cell death may protect kidneys against the development of fibrosis. The direct inhibition of caspase activity in a rat ischemia-reperfusion model resulted in reduced inflammation and fibrosis (6). Cell-permeable antioxidants that act on the mitochondria protect against the apoptosis and development of fibrosis in the UUO model (27). In this study, the level of Omi protein released into the cytosol is correlated with the degree of apoptosis, resulting in fibrosis, induced by UUO. Once in the cytoplasm, Omi degrades XIAP and a variety of other substrates to promote caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death (5, 36). Additionally, ucf-101, an inhibitor of Omi protease activity, significantly mitigates all of these morphological and biochemical changes after UUO. Several in vivo animal experiments have provided evidence for a possible proapoptotic role for Omi in heart and brain ischemia-reperfusion injury (3, 24), cisplatin-induced kidney injury (4, 13), and Huntington's disease (10). These results implicate the activation of Omi after UUO as a pivotal contributor to the tubular cell apoptosis which ultimately results in kidney fibrosis.

Omi induces apoptosis by binding to and degrading XIAP, a major caspase-dependent cell death inhibitor protein (1, 2, 26, 30, 32). Among the IAP family, XIAP is the most potent inhibitor of caspases and apoptosis. Omi, upon release from the mitochondria, interacts with both baculovirus IAP repeat (BIR) domain 2 (BIR2) and BIR3 domains of XIAP. The BIR2 of XIAP inhibits caspase-3 and caspase-7, effector caspases, and BIR3 inhibits caspase 9, an initiator caspase (34). Caspases initiate apoptotic cell death via the cleavage of specific substrate proteins (7, 23). Additionally, Omi induces atypical caspase-independent cell death, a process that requires its proteolytic activity (23, 34, 37). It has been demonstrated that ucf-101 does not directly inhibit caspase-3 activation (5). This indicates that the antiapoptotic effect of ucf-101 is associated with the inhibition of Omi protease activation. It has recently been noted that ucf-101 affected other proteases (22). Therefore, we were not able to entirely dismiss the possibility that ucf-101 may affect other proteases in UUO kidneys. Omi/HtrA2 is part of a family consisting of four members with substantial similarity in their catalytic domains (29). Ucf-101 might affect their function, as well as the function of other uncharacterized proteases (5, 22, 29). None of the other HtrA2 family members have thus far been implicated in the process of apoptosis; all of them, with the exception of Omi, are extracellular proteins (36). This suggests that ucf-101 effectively inhibited Omi/HtA2. A number of previous in vitro and in vivo animal studies have clearly demonstrated that the presence of ucf-101 protects against XIAP cleavage as well as the cleavage of other Omi-specific substrates, thereby indicating that the primary target of ucf-101 is the Omi protease (3, 4, 10, 12, 13, 24, 26).

Collectively, the results of this study show that UUO-induced kidney fibrosis is regulated by the Omi-XIAP-apoptotic pathway as described in the Fig. 8E, thereby suggesting that the targeting of the proteolytic activity of Omi may constitute a viable strategy for the treatment of fibrotic kidney diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by a Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD; KRF-2008-313-E00015 to K. M. Park) and National Institutes of Health Grants DK39773 (to J. V. Bonventre) and DK055734 (to A. Zervos).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Althaus J, Siegelin MD, Dehghani F, Cilenti L, Zervos AS, Rami A. The serine protease Omi/HtrA2 is involved in XIAP cleavage and in neuronal cell death following focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Neurochem Int 50: 172–180, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhuiyan MS, Fukunaga K. Activation of HtrA2, a mitochondrial serine protease mediates apoptosis: current knowledge on HtrA2 mediated myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Ther 26: 224–232, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bhuiyan MS, Fukunaga K. Inhibition of HtrA2/Omi ameliorates heart dysfunction following ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat heart in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol 557: 168–177, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cilenti L, Kyriazis GA, Soundarapandian MM, Stratico V, Yerkes A, Park KM, Sheridan AM, Alnemri ES, Bonventre JV, Zervos AS. Omi/HtrA2 protease mediates cisplatin-induced cell death in renal cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F371–F379, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cilenti L, Lee Y, Hess S, Srinivasula S, Park KM, Junqueira D, Davis H, Bonventre JV, Alnemri ES, Zervos AS. Characterization of a novel and specific inhibitor for the pro-apoptotic protease Omi/HtrA2. J Biol Chem 278: 11489–11494, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daemen MA, van 't Veer C, Denecker G, Heemskerk VH, Wolfs TG, Clauss M, Vandenabeele P, Buurman WA. Inhibition of apoptosis induced by ischemia-reperfusion prevents inflammation. J Clin Invest 104: 541–549, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deveraux QL, Reed JC. IAP family proteins—suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev 13: 239–252, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Docherty NG, O'Sullivan OE, Healy DA, Fitzpatrick JM, Watson RW. Evidence that inhibition of tubular cell apoptosis protects against renal damage and development of fibrosis following ureteric obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F4–F13, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feldenberg LR, Thevananther S, del Rio M, de Leon M, Devarajan P. Partial ATP depletion induces Fas- and caspase-mediated apoptosis in MDCK cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 276: F837–F846, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goffredo D, Rigamonti D, Zuccato C, Tartari M, Valenza M, Cattaneo E. Prevention of cytosolic IAPs degradation: a potential pharmacological target in Huntington's Disease. Pharmacol Res 52: 140–150, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gross A, McDonnell JM, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family members and the mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev 13: 1899–1911, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hegde R, Srinivasula SM, Zhang Z, Wassell R, Mukattash R, Cilenti L, DuBois G, Lazebnik Y, Zervos AS, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Identification of Omi/HtrA2 as a mitochondrial apoptotic serine protease that disrupts inhibitor of apoptosis protein-caspase interaction. J Biol Chem 277: 432–438, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hentschel DM, Park KM, Cilenti L, Zervos AS, Drummond I, Bonventre JV. Acute renal failure in zebrafish: a novel system to study a complex disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F923–F929, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim J, Jang HS, Park KM. Reactive oxygen species generated by renal ischemia and reperfusion trigger protection against subsequent renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F158–F166, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim J, Jung KJ, Park KM. Reactive oxygen species differently regulate renal tubular epithelial and interstitial cell proliferation after ischemia and reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. First published February 17, 2010; doi:1011/52/ajprenal.00701-2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim J, Kil IS, Seok YM, Yang ES, Kim DK, Lim DG, Park JW, Bonventre JV, Park KM. Orchiectomy attenuates post-ischemic oxidative stress and ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. A role for manganese superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem 281: 20349–20356, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim J, Kim JI, Kwon TH, Park KM. Kidney tubular cell regeneration starts in the deep cortex after ischemia. Korean J Nephrol 27: 536–544, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim J, Kim KY, Jang HS, Yoshida T, Tsuchiya K, Nitta K, Park JW, Bonventre JV, Park KM. Role of cytosolic NADP+-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase in ischemia-reperfusion injury in mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F622–F633, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim J, Park JW, Park KM. Increased superoxide formation induced by irradiation-preconditioning triggers kidney resistance to ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1202–F1211, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim J, Seok YM, Jung KJ, Park KM. Reactive oxygen species/oxidative stress contributes to progression of kidney fibrosis following transient ischemic injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F461–F470, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klahr S, Morrissey J. Obstructive nephropathy and renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F861–F875, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klupsch K, Downward J. The protease inhibitor Ucf-101 induces cellular responses independently of its known target, HtrA2/Omi. Cell Death Differ 13: 2157–2159, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kroemer G, Martin SJ. Caspase-independent cell death. Nat Med 11: 725–730, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu HR, Gao E, Hu A, Tao L, Qu Y, Most P, Koch WJ, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Alnemri ES, Zervos AS, Ma XL. Role of Omi/HtrA2 in apoptotic cell death after myocardial ischemia and reperfusion. Circulation 111: 90–96, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ma J, Nishimura H, Fogo A, Kon V, Inagami T, Ichikawa I. Accelerated fibrosis and collagen deposition develop in the renal interstitium of angiotensin type 2 receptor null mutant mice during ureteral obstruction. Kidney Int 53: 937–944, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martins LM, Iaccarino I, Tenev T, Gschmeissner S, Totty NF, Lemoine NR, Savopoulos J, Gray CW, Creasy CL, Dingwall C, Downward J. The serine protease Omi/HtrA2 regulates apoptosis by binding XIAP through a reaper-like motif. J Biol Chem 277: 439–444, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mizuguchi Y, Chen J, Seshan SV, Poppas DP, Szeto HH, Felsen D. A novel cell-permeable antioxidant peptide decreases renal tubular apoptosis and damage in unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1545–F1553, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Park KM, Kramers C, Vayssier-Taussat M, Chen A, Bonventre JV. Prevention of kidney ischemia/reperfusion-induced functional injury, MAPK and MAPK kinase activation, and inflammation by remote transient ureteral obstruction. J Biol Chem 277: 2040–2049, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quesneville H, Nouaud D, Anxolabehere D. Detection of new transposable element families in Drosophila melanogaster and Anopheles gambiae genomes. J Mol Evol 57, Suppl 1: S50–S59, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schimmer AD. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins: translating basic knowledge into clinical practice. Cancer Res 64: 7183–7190, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seok YM, Kim J, Park MJ, Boo YC, Park YK, Park KM. Wen-pi-tang-Hab-Wu-ling-san attenuates kidney fibrosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion in mice. Phytother Res 22: 1057–1063, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Srinivasula SM, Gupta S, Datta P, Zhang Z, Hegde R, Cheong N, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins are substrates for the mitochondrial serine protease Omi/HtrA2. J Biol Chem 278: 31469–31472, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Su D, Su Z, Wang J, Yang S, Ma J. UCF-101, a novel Omi/HtrA2 inhibitor, protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 292: 854–861, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suzuki Y, Imai Y, Nakayama H, Takahashi K, Takio K, Takahashi R. A serine protease, HtrA2, is released from the mitochondria and interacts with XIAP, inducing cell death. Mol Cell 8: 613–621, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suzuki Y, Nakabayashi Y, Takahashi R. Ubiquitin-protein ligase activity of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein promotes proteasomal degradation of caspase-3 and enhances its anti-apoptotic effect in Fas-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 8662–8667, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vande Walle L, Lamkanfi M, Vandenabeele P. The mitochondrial serine protease HtrA2/Omi: an overview. Cell Death Differ 15: 453–460, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yang QH, Church-Hajduk R, Ren J, Newton ML, Du C. Omi/HtrA2 catalytic cleavage of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) irreversibly inactivates IAPs and facilitates caspase activity in apoptosis. Genes Dev 17: 1487–1496, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]