Abstract

Objectives To determine the relation between the HIV/AIDS epidemic and support for dependent elderly people in Africa.

Design Retrospective analysis using data from Demographic and Health Surveys.

Setting 22 African countries between 1991 and 2006.

Participants 123 176 individuals over the age of 60.

Main outcome measures We investigated how three measures of the living arrangements of older people have been affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic: the number of older individuals living alone (that is, the number of unattended elderly people); the number of older individuals living with only dependent children under the age of 10 (that is, in missing generation households); and the number of adults age 18-59 (that is, prime age adults) per household where an older person lives.

Results An increase in annual AIDS mortality of one death per 1000 people was associated with a 1.5% increase in the proportion of older individuals living alone (95% CI 1.2% to 1.9%) and a 0.4% increase in the number of older individuals living in missing generation households (95% CI 0.3% to 0.6%). Increases in AIDS mortality were also associated with fewer prime age adults in households with at least one older person and at least one prime age adult (P<0.001). These findings suggest that in our study countries, which encompass 70% of the sub-Saharan population, the HIV/AIDS epidemic could be responsible for 582 200-917 000 older individuals living alone without prime age adults and 141 000-323 100 older individuals being the sole caregivers for young children.

Conclusions Africa’s HIV/AIDS epidemic might be responsible for a large number of older people losing their support and having to care for young children. This population has previously been under-recognised. Efforts to reduce HIV/AIDS deaths could have large “spillover” benefits for elderly people in Africa.

Introduction

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is changing demographic and household structures in sub-Saharan Africa.1 The effect of the disease on child mortality,2 life expectancy,3 and dependent children is well established. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that by 2007, HIV/AIDS had orphaned more than 12 million children in sub-Saharan Africa.4 However, the toll of the epidemic on Africa’s elderly population is poorly characterised.

Despite the epidemic’s effects, the number of adults over the age 60 in Africa is projected to rise by 55% between 2010 and 2025, a 135% increase since 1995.5 6 These changes will increase the dependency ratio and the demand for old age support. In parallel to this demographic transition, however, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is decreasing the supply of family caregivers. Unlike many other diseases, HIV/AIDS causes deaths primarily among working age adults,7 8 who often serve as primary caregivers for dependent elderly family members.9 10

In middle income and high income countries, the informal caregiving burden associated with longer lifespans has historically generated political pressure for governments to create old age security programmes. With a few exceptions, formal arrangements for elderly care do not yet exist in sub-Saharan Africa. Instead, family members continue to play a vital role in supporting aging kin.11 12

In this paper, we quantitatively assessed the extent to which HIV/AIDS is responsible for diminishing support and increasing isolation among older individuals in sub-Saharan Africa. This phenomenon has been described qualitatively and analysed in a few select countries using demographic simulation methods.13 14 15 16 We analysed nationally representative household survey data from a large number of African countries to examine the relation between the HIV/AIDS epidemic and household support structures for elderly individuals in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

Study population and data

Our data on the characteristics of the elderly population and on living arrangements came from the Demographic and Health Surveys conducted by Macro International, Calverton, MD. These surveys are nationally representative household level surveys of many low income and middle income countries and are performed approximately once every five years. The standard survey includes questions about household composition and living arrangements such as age, relationship to head of household, education, and marital status of each member of the household.

In our analysis, we included all sub-Saharan countries where multiple Demographic and Health Surveys had been conducted between 1991 and 2006 and included explicit primary sampling units and strata. Our final sample included 123 176 older individuals (age 60 or older) surveyed during 58 Demographic and Health Survey waves in 22 countries—Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

We investigated how three measures of the living arrangements of older people have been affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic: the number of older individuals living alone without any prime age adults (that is, the number of unattended elderly people); the number of older individuals living with only dependent children (that is, in missing generation households); and the number of prime age adults per household where an elderly individual lives. Unattended elderly people may require support and may be harmed by living without prime age adults. In missing generation households, older individuals are likely to care for the young children, incurring the burdens of child support in addition to the hardships of caring for themselves without adult support. Elderly individuals may also lose support if some but not all of their adult caregivers die and they are left with fewer prime age providers in the house. For this reason, we also considered the number of adults per household in households with at least one older person and at least one prime age adult.

We defined an elderly person to be 60 years of age or older, a prime age adult to be between the ages of 18 and 59, and a dependent child to be under the age of 10. We used the age criterion of 60 years or older to define an older individual because it captures the oldest 5% of the African population, who may require financial and physical support (by comparison, the oldest 5% of the population in the US comprise people who are more than 75 years old.17 We considered dependent children to be those under the age of 10 because it is unclear whether 11 to 18 year olds would care for elderly people or be cared for by elderly people.

We used AIDS mortality (rate of AIDS related deaths per 1000 people) as a measure of the severity of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and as the primary predictor for the living conditions of older people. To arrive at the AIDS mortality rate, we divided the annual number of AIDS related deaths in each country by the population (in thousands) during that year. Our estimates of annual AIDS related deaths came from public reports of country and year mortality data produced by UNAIDS.4 UNAIDS calculates the number of AIDS related deaths by using HIV and AIDS incidence values from antenatal clinic and sentinel surveillance data combined with information on survival and antiretroviral drug use.18 We used mid-year country population estimates published by the US Census Bureau’s population division as denominators for constructing AIDS mortality rates.

Statistical analysis

For dichotomous dependent variables—unattended elderly people and missing generation households—we estimated the importance of the AIDS mortality rate by using probit models fit by maximum likelihood estimation. For the number of prime age adults living in households with older people, we estimated our parameter of interest using ordinary least squares regressions. Where we used probit models, we report marginal effects, which represent the change in likelihood of the outcome given a one point change in the predictor variable. See the web extra for a detailed explanation of the estimation techniques and sensitivity analysis, as well as further discussion of sample selection.

The Demographic and Health Surveys data include a rich set of socioeconomic variables. In adjusted analyses, we controlled for age, sex, place of residence (urban or rural), education, country, and whether households had electricity, flush toilets, plumbing, dirt floors, bikes, and radios. We adjusted for whether participants lived in urban or rural areas because previous research suggests that younger adults are presently migrating to urban areas at high rates—a trend that might be correlated with the AIDS mortality rate.19 We included whether households had electricity, flush toilets, plumbing, bikes, dirt floors, and radios as a measure of socioeconomic status, because poverty may modify the effect of the epidemic on living conditions.

To adjust for unobserved differences between countries and to account for common linear changes over time, we included country dummy variables and a survey year variable. Given that the Demographic and Health Surveys data are available for only some years in some countries, we were unable to include country dummy and survey year variables simultaneously. In this paper, we present the version with country dummy variables. The version with year dummy variables yielded similar results and is available in the web extra. In all our statistical analyses, we used information about sampling stratification and primary sampling units in order to properly estimate standard errors. The web extra provides further details on our selection and use of control variables.

We then used our results to estimate the increase in the number of unattended elderly people associated with the severity of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in each country. Firstly, we multiplied the estimated marginal effects of the AIDS mortality rate by each country’s mortality rate in 2006, yielding the fraction of older people who were unattended as a result of a death from AIDS. Secondly, we multiplied this fraction by the total number of older people in each country, yielding the estimated number of unattended elderly people as a result of HIV/AIDS. We used 95% confidence intervals for the coefficients in our probit models to construct lower and upper bounds for the size of the unattended elderly population.

Results

The proportion of unattended elderly people out of the total number of older individuals in sub-Saharan Africa increased significantly from 23.5% at the earliest surveys (median year 1993) to 26.1% at the most recent surveys (median year 2004; P=0.04). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample. Compared with older individuals who lived with prime age adults, unattended elderly people were less likely to be men, to live in urban environments, and to have completed primary school (P<0.001 for all). They were also less likely to have assets at home such as radios (P<0.001), suggesting that living alone is associated with lower socioeconomic status.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the elderly population

| Total (n=123 176) | Unattended elderly* (n=32 196) | Attended elderly (n=90 980) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.7 | 69.9 | 68.2 | <0.001 |

| Male (%) | 51.6 | 35.7 | 57.4 | <0.001 |

| Urban (%) | 18.0 | 14.1 | 19.5 | <0.001 |

| Has a radio at home (%) | 44.9 | 25.8 | 51.8 | <0.001 |

| Completed primary school (%) | 8.9 | 7.1 | 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Proportion of unattended elderly† | ||||

| Earliest survey | — | 23.5% | — | — |

| Most recent survey | — | 26.1% | — | — |

| P value | — | 0.04 | — | — |

*Unattended elderly refers to individuals over the age 60 who live with no prime age adults (age 18-59).

†A comparison of the proportion of elderly people living without prime age adults over time. The median year of the earliest survey was 1993 and the most recent survey 2004.

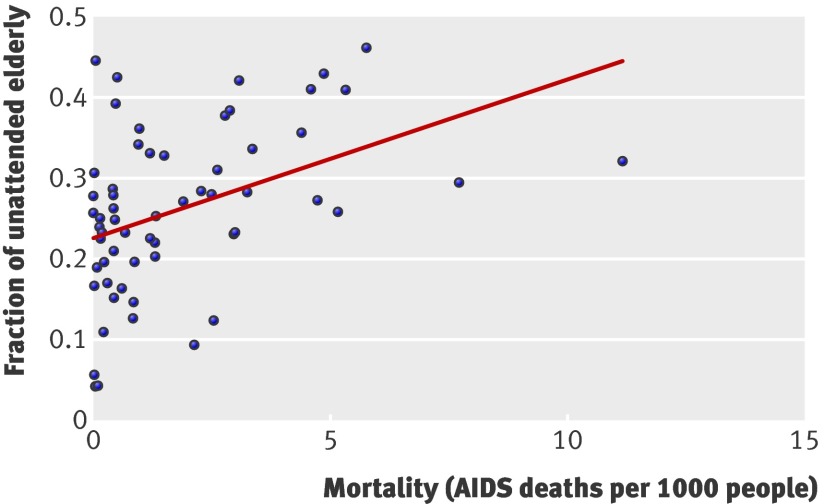

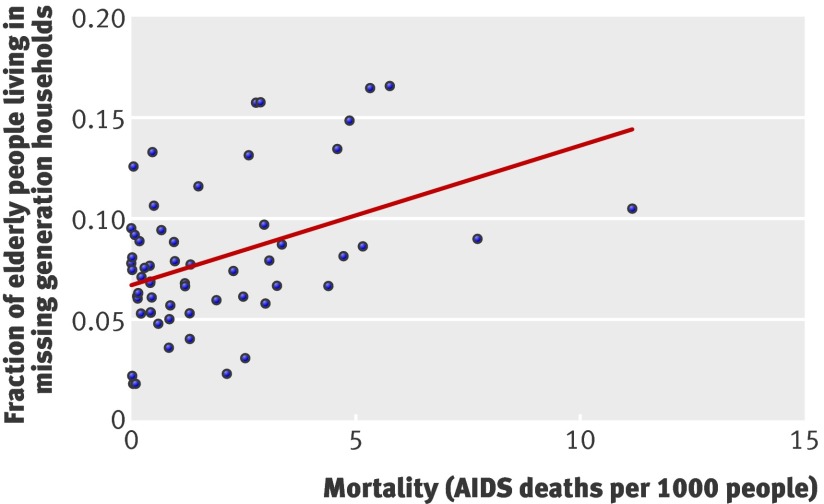

Figure 1 shows the relation between the AIDS mortality rate (AIDS related deaths per 1000 people) and the proportion of elderly people living alone without any prime age adults. Each data point in the figure represents a country-year observation. The scatterplot and accompanying regression line (fit by ordinary least squares using population weighted samples) show a positive correlation between the AIDS mortality rate and the proportion of unattended elderly individuals. Figure 2 shows the association of the AIDS mortality rate with the proportion of missing generation households. This figure suggests an association between the severity of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the proportion of older people serving as primary caretakers of young children. Further analyses presented in the web extra suggest that this relation is not attributable to the undue influence of outliers.

Fig 1 AIDS mortality rate and the proportion of older people living alone without any adults between the ages of 18 and 59. The line represents unadjusted linear regression showing higher fractions of unattended elderly people associated with higher AIDS mortality rates. The primary analysis uses a probit regression

Fig 2 AIDS mortality rate and the proportion of older people living in missing generation households—that is, households where older people live with children under the age of 10 and without any adults between the ages of 18 and 59. The line represents unadjusted linear regression showing higher rates of elderly individuals living in missing generation households associated with higher AIDS mortality rates. The primary analysis uses a probit regression

The results of tests for the strength of the association between the AIDS mortality rate and the living arrangements of elderly individuals are shown in table 2. We present the marginal effects obtained from the probit models and coefficient estimates obtained from the linear regressions (using population weights in all cases). The severity of the HIV/AIDS epidemic was significantly and positively associated with the proportion of older people living unattended. After adjusting for age, sex, place of residence (urban or rural), education, measures of household wealth (that is, whether individuals had electricity, flush toilets, plumbing, dirt floors, bikes, and radios), and country, a one point increase in the AIDS mortality rate was associated with a 1.53% increase in the proportion of older people living alone (95% CI 1.19% to 1.87%; P<0.001) and a 0.42% increase in the proportion of older people living in missing generation households (95% CI 0.31% to 0.58%; P<0.001). The unadjusted analysis yielded similar results to the adjusted analysis.

Table 2.

AIDS mortality rate and changes in support for elderly people in Africa*

| Model | Unadjusted estimate | Adjusted estimate† | 95% confidence interval | Adjusted standard error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of unattended elderly people (%) | Probit | 2.27 | 1.53 | 1.19 to 1.87 | 0.17 |

| Proportion of elderly individuals living in missing generation households‡ (%) | Probit | 0.75 | 0.42 | 0.31 to 0.58 | 0.08 |

| Number of prime age adults per elderly household§ | Ordinary least squares | −0.13 | −0.07 | −0.09 to −0.06 | 0.01 |

*All regression coefficients reflect the changes in outcome variable given an increase in the annual AIDS death rate of one additional death in 1000 people. Values from the probit models are marginal effects estimates and those from the ordinary least squares regression are coefficient estimates. Population weights are used for all estimates.

†Adjusted for age, sex, residence (urban or rural), education, measures of household wealth, and country.

‡Older individuals living with only dependent children under the age of 10 years.

§Measures changes in the number of prime age adults per elderly household among households with at least one prime age adult.

We observed a similar pattern between the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the number of prime age adults living with elderly individuals (table 2). An increase in the annual AIDS mortality rate of one extra death per 1000 people was associated with 0.13 fewer prime age adults per elderly individual in households with at least one prime age adult. After adjustment, the number of prime age adults per elderly household fell by 0.07 for each one point increase in AIDS mortality rate (95% CI −0.09 to −0.06 P<0.001).

Finally, we used our parametric estimates to assess the population impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on the living arrangements of elderly individuals in each of the countries examined. Table 3 shows estimates of the number of unattended elderly people linked to AIDS mortality in 2006. The calculations in table 3 assume that the same parametric relation between unattended elderly people and AIDS mortality within our study sample holds for each country in 2006. The results of the “leave one out” analysis presented in the web extra suggest that this assumption is reasonable because the parametric relation is stable across countries and time.

Table 3.

Number of unattended elderly people associated with AIDS mortality in 2006 by country*

| Country | Number of unattended elderly |

|---|---|

| Benin | 1600-2500 |

| Burkina Faso | 4500-7000 |

| Cameroon | 25 500-40 100 |

| Chad | 7600-12 000 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 24 100-38 000 |

| Ethiopia | 38 800-61 000 |

| Ghana | 13 100-20 600 |

| Guinea | 2200-3500 |

| Kenya | 57 000-89 700 |

| Madagascar | 500-700 |

| Malawi | 31 200-49 100 |

| Mali | 2900-4600 |

| Mozambique | 44 700-70 400 |

| Namibia | 3100-4800 |

| Niger | 1900-3000 |

| Nigeria | 109 400-172 300 |

| Rwanda | 4400-7000 |

| Senegal | 900-1400 |

| Tanzania | 57 200-90 100 |

| Uganda | 33 100-52 200 |

| Zambia | 30 200-47 500 |

| Zimbabwe | 89 400-140 700 |

| Total | 582 200-917 000 |

*Estimates were obtained using the marginal effects from the adjusted probit model and population estimates from the US Census Bureau’s international database. The range represents the 95% confidence bounds of the marginal effects when controlling for age, sex, residence (urban or rural), education, measures of household wealth, and country.

Our estimates suggest that in the 22 African countries included in our study, an additional 582 200-917 000 elderly people were living unattended because of deaths from AIDS in 2006 (using the 95% upper and lower confidence bounds for each country). Using similar methods, we estimated that the HIV/AIDS epidemic was responsible for an additional 141 000-323 100 older individuals living in missing generation households in the 22 study countries in 2006. Notably, only 70% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa lives in these countries, suggesting that the overall numbers for the entire continent are even larger.

Discussion

Principal findings

We provide strong evidence that the share of older people living without adult caregivers in sub-Saharan Africa is associated with the spread of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (that is, the fraction of elderly people without caregivers is higher in countries where HIV/AIDS is more prevalent). Although the epidemic’s toll is known to extend beyond those infected, its effect on the population of older individuals in Africa was previously under-recognised. We demonstrate that increases in AIDS mortality are strongly associated with at least three changes in the living conditions of the older people: an increase in the number living without any prime age adults; an increase in the number living by themselves in households with children under age 10 (who presumably depend on them for care); and a decrease in the number of prime age adults living with elderly individuals in households where elderly and prime age adults live together. We identified several risk factors associated with living without the support of prime age adults (that is, the most vulnerable older people): female sex, little education, living in a rural area, and poor household wealth. These results imply a disproportionate effect of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on elderly individuals with lower socioeconomic status.

Strengths and limitations

This paper is the first multi-year, cross national study of the relation between HIV/AIDS mortality and living arrangements of elderly individuals in Africa. Previous studies have examined the effect of HIV/AIDS on older people in specific countries or regions20 21 22 23; however, the scope of the association remained poorly characterised. Other research emphasised that elderly individuals may be a resource for prime age adults with HIV/AIDS, overlooking the burden that this situation places on older people.24 25 26 Our study includes data from countries that represent the majority of Africa’s population, allowing us to provide more generalisable estimates.

The number of prime age adults has declined, shifting greater responsibility to Africa’s elderly people. A substantial portion of the older people in our sample lived with only young children. Our findings are likely to be an underestimate of the true caretaking burden on older people for two main reasons. Firstly, we excluded all children older than 10 years, some of whom are likely to need care. Secondly, we were unable to identify households in which older people might also care for their ailing or debilitated adult children who have AIDS. These elderly individuals, who were previously supported through advanced age and failing health, may find themselves as the primary caretakers of young children or without the support of prime age adults.

Although this study estimates the scope and prevalence of unattended elderly individuals, it does not address several important issues. We did not directly evaluate whether the health of unattended older people was worse than that of elderly individuals who were supported by prime age adult family members (although it may be reasonable to assume so). We also know little about the quality of life of older people who live alone, although it is likely that becoming the primary caregiver of young children is a physical and financial burden for older people.

Additionally, it is possible that there is an association between AIDS mortality and elderly individuals choosing to live alone for reasons not related to the HIV/AIDS epidemic or prime age adults choosing to live apart from their elderly relatives. We did not find evidence supporting these scenarios. Repeated analysis of subsets of the data yielded consistent results, but we cannot entirely rule out unobserved confounders.

Conclusions and policy implications

The link between the high proportion of elderly people living without prime age adults and AIDS mortality could have important policy implications for African countries. This phenomenon coincides with demographic changes that are projected to increase the size of the elderly population. The number of elderly people who may require substantial support but have no prime age family members to care for them could pose significant challenges to communities and governments. Given that most countries in sub-Saharan Africa do not have “safety net” programmes for the elderly and governments are not likely to enact broad new support programmes for older people in the immediate future, prime age adults will be increasingly important in caring for the elderly population. Thus, policies that reduce morbidity and mortality from HIV/AIDS in the adult population may have considerable “spillover” benefits for tolder people.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa is changing the demographic landscape. We show the existence of a new population of elderly individuals who lack support from adults and who may need to provide for their grandchildren. Future work is needed to examine more closely the health and overall welfare of this population, but our work suggests that reducing AIDS deaths in Africa may provide substantial benefits to this under-recognised population.

What is already known on this topic

The number of adults over the age 60 in Africa is projected to rise by 55% between 2010 and 2025

The HIV/AIDS epidemic is decreasing the number of adults aged between 18 and 59 (prime age adults)

Previous studies have examined the effect of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on the living arrangements of elderly individuals in specific countries or regions, but it is unclear whether their findings apply beyond of populations considered

Previous studies also do not consider the burden imposed on older people by the fall in the number of prime age adults caused by the HIV/AIDS epidemic

What this study adds

This paper is the first multi-year, cross national study of the relation between AIDS mortality and the living arrangements of elderly individuals in Africa

A one point increase in the AIDS mortality rate was associated with a 1.5% increase in the proportion of older people living alone and a 0.4% increase in the proportion of elderly individuals living with children under the age of 10 and without prime age adults

In the 22 African countries included in our study, deaths from AIDS were associated with an additional 582 200-917 000 elderly people living unattended and 141 000-323 100 elderly individuals living with only dependent children in 2006

Our study includes data from countries that represent the majority of sub-Saharan Africa’s population, making our estimates more generalisable than those of previous studies

We thank participants at the research in progress seminar at Stanford Medical School for their insights.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study conception and design; interpretation of the data; writing of the manuscript; and approval of the final submission. TK coded the data and performed the statistical analysis. TK is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging (K02-AG024237), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K01-HD053504), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (T32-HS000028), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K01-AI084582), and the Stanford Center for Demography and Economics of Aging (P30-AG017253). The supporting agencies had no part in formulating, analysing, or writing this work.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and all authors declare: (1) Financial support for the submitted work from the bodies listed in the funding statement; (2) No financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (3) No spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (4) No non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval and signed patient consent forms were not required for our study.

Data sharing: Technical appendix available from tkautz@uchicago.edu.

Cite this as: BMJ 2010;340:c2841

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary appendix

References

- 1.Gregson S, Nyamukapa C, Lopman B, Mushati P, Garnett GP, Chandiwana SK, et al. Critique of early models of the demographic impact of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa based on contemporary empirical data from Zimbabwe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:14586-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newell ML, Brahmbhatt H, Ghys PD. Child mortality and HIV infection in Africa: a review. AIDS 2004;18(suppl 2):27-34S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piot P, Bartos M, Ghys PD, Walker N, Schwartlaender B. The global impact of HIV/AIDS. Nature 2001;410:968-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2008. http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/default.asp.

- 5.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population prospects: the 2006 revision, highlights. 2007. www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2006/WPP2006_Highlights_rev.pdf.

- 6.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World urbanization prospects: the 2005 revision. 2006. www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WUP2005/2005wup.htm.

- 7.Nyirenda M, Hosegood V, Bärnighausen T, Newell ML. Mortality levels and trends by HIV serostatus in rural South Africa. AIDS 2007;21:73-9S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith J, Mushati P, Kurwa F, Mason P, Gregson S, Lopman B. Changing patterns of adult mortality as the HIV epidemic matures in Manicaland, eastern Zimbabwe. AIDS 2007;21(suppl 6):81-6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aboderin I. Decline in material family support for older people in urban Ghana, Africa: understanding processes and causes of change. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2004;59:128-37S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrientos A, Gorman M, Heslop A. Old age and poverty in developing countries: contributions and dependence in later life. World Dev 2003;31:555-70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unanka GO. Family support and health status of the elderly in Imo State of Nigeria. J Soc Issues 2003;58:681-95. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cattell MG. Models of old age among the Samia of Kenya: family support of the elderly. J Cross Cult Gerontol 1990;5:375-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ssengonzi R. The plight of older persons as caregivers to people infected/affected by HIV/AIDS: evidence from Uganda. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2007;22:339-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wachter KW, Knodel J, VanLandingham M. Parental bereavement: heterogeneous impacts of AIDS in Thailand. J Econometrics 2003;112:193-206. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wachter KW, Knodel J, VanLandingham M. AIDS and the elderly of Thailand: projecting familial impacts. Demography 2002;39:25-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knodel J, VanLandingham M. The impact of the AIDS epidemic on older persons. AIDS 2002;16(suppl):77-83S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Database. Population Division, US Census Bureau. Washington, DC: 2008. http://www.census.gov/.

- 18.Ghys PD, Brown T, Grassly NC, Garnett G, Stanecki KA, Stover J, et al. The UNAIDS estimation and projection package: a software package to estimate and project national HIV epidemics. Sex Trans Infect 2004;80:5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agesa RU. One family, two households: rural to urban migration in Kenya. Rev Econ Household 2004;2:161-78. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ntozi JPM, Zirimenya S. Changes in household composition and family structure during the AIDS epidemic in Uganda. In: Caldwell JC, Orubuloye IO, Ntozi JPM, eds. The continuing African HIV/AIDS epidemic. Australian National University, National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Health Transition Centre, 1999:193-209.

- 21.Merli MG, Palloni A. The HIV/AIDS epidemic, kin relations, living arrangements, and the African elderly in South Africa. In: Cohen B, Menken J, eds. Aging in sub-Sahran Africa: recommendations for further research. The National Academies Press, 2006:117-65.

- 22.Zimmer Z, Dayton J. Older adults in sub-Saharan Africa living with children and grandchildren. Popul Stud (Camb) 2000;59:295-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nyambedha EO, Wandibbaa S, Aagaard-Hansen J. Changing patterns of orphan care due to the HIV epidemic in western Kenya. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:301-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knodel J, VanLandingham M, Saengtienchai C, Im-em W. Older people and AIDS: quantitative evidence of the impact in Thailand. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:1313-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dayton J, Ainsworth M. The elderly and AIDS: coping strategies and health consequences in rural Tanzania. Policy Research Division Working Papers 2002, No. 160. http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/wp/160.pdf.

- 26.Williams A, Bennett E, Himmavanh V, Salazar F. “They just go home and die”: health care and terminal illness in rural northeast Thailand. Asian Stud Rev 1996;20:98-108. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary appendix