Abstract

Background/Aims

Ghrelin has recently been reported as exerting a protective effect in the damaged pancreas in rats. We investigated the correlation between severity of acute pancreatitis and serum ghrelin concentrations.

Methods

Blood samples were collected three times (at admission, after 48 hours, and at discharge) from patients admitted with acute pancreatitis. We divided the patients into nonrisk and risk groups. The risk group was defined as the presence of at least one of following risk factors for severe acute pancreatitis: Ranson's score ≥3, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II score ≥8, C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥150 mg/L, and CT severity index (CTSI) ≥4. Serum ghrelin concentrations were measured with RIA kit and analyzed based on clinical and biochemical parameters.

Results

A total of 53 patients was enrolled in this study: 28 in the nonrisk group and 25 in the risk group. At admission, the ghrelin concentration was significantly higher in the risk group (286.39±272.19 vs 175.96±138.87 pg/mL [mean±SD], p=0.049). However, the ghrelin concentration did not differ significantly between the two groups after 48 hours (p=0.450) and at discharge (p=0.678). The overall ghrelin concentration was significantly lower at admission than at discharge (240.65±247.96 vs 369.41±254.27 pg/mL, p=0.001).

Conclusions

Patients with risk factors for severe acute pancreatitis have higher serum ghrelin concentrations.

Keywords: Ghrelin, Acute pancreatitis

INTRODUCTION

Since the mortality rates of severe acute pancreatitis is high as 20 to 30% and a half of mortality occurs within 2 weeks due to multisystem organ failures, such patients should be treated actively at early stage of disease to improve outcomes. Various prognostic indices and serum markers are being used to evaluate the severity of acute pancreatitis at the beginning of treatment. The classical prognostic indices include multiple factor scoring systems such as Ranson's criteria and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II system. Serum markers include serum C-reactive protein (CRP), polymorphonuclear elastase, urine trypsinogen activation peptide, and so on.1-6 Abdominal computed tomography is useful for the evaluation of local complications of acute pancreatitis. Computed tomography severity index (CTSI) which is calculated in scores based on the CT findings is used to evaluate the severity and prognosis of acute pancreatitis.7

Ghrelin is a hormone known to promote appetite and mostly originate from the stomach and small intestine. Recent studies suggest that ghrelin increases the secretion of gastric acid and digestive enzymes in the pancreas and activates bowel movements, thereby serving an important role in the processing of the ingested foods.8 The prominent expressions of ghrelin in the endocrine cells of human fetal pancreas suggest the association of ghrelin with the development of the pancreas.9 In addition, there was a study data demonstrating that treatment with ghrelin reduces the severity of caerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats and there was another report indicating that plasma concentration of ghrelin significantly increased when the patients with acute pancreatitis recovered from illness.10,11 Therefore, we examined the association between the severity of acute pancreatitis and the concentration of ghrelin. We also analysed the pattern of change in the blood concentration of ghrelin during the course of acute pancreatitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

The concentrations of serum ghrelin were measured in the patients who were hospitalized into Gangneung Asan Hospital with acute pancreatitis from February 2008 through November 2008. Total 81 patients were enrolled in this study. Patients with tumors of the pancreas or other organs, patients with gastric ulcer in the active or healing phase and patients with hyperthyroidism were excluded from the study subjects. Patients with any history of gastrointestinal surgery were also excluded. When there were any problems in blood collections or serum storages, we excluded the corresponding patients. Among 81 patients hospitalized with acute pancreatitis, 28 patients were excluded and 53 patients were analyzed in this study.

2. Methods

A diagnosis of acute pancreatitis was made if the patients have two of the three following features: 1) abdominal pain characteristic of acute pancreatitis, which is acute epigastric pain continued for more than 24 hours, 2) serum amylase and/or lipase ≥3 times the upper limit of normal, and 3) characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on CT scan.12 To measure serum ghrelin concentration, blood samples were obtained when the patients were admitted with acute pancreatitis and 48 hours after hospitalization. The collected blood samples were centrifuged and then the separated sera were frozen at -70℃ for subsequent analysis. To examine changes in serum ghrelin concentration, blood samples were collected from some patients when they were discharged. The sera of 81 patients in total were stored and the sera of 53 patients who were suitable to this study were thawed and the ghrelin concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay. The ghrelin RIA kit (LINCO Research, St. Charles, MO, USA) was used for measurement of serum ghrelin levels. The measured ghrelin level was the total ghrelin containing both acylated ghrelin and des-acylated ghrelin.

The enrolled patients were divided into two groups: group with risk factors of severe acute pancreatitis (risk group) and group without risk factor (nonrisk group). The risk factors of severe acute pancreatitis were defined as the Ranson's score ≥3, the highest APACHE II score calculated within 48 hours after hospitalization ≥8, the CTSI calculated from the abdominal CT performed during hospitalization ≥4, and the CRP measured around 48 hours after hospitalization ≥150 mg/L.13 Patients who had one or more risk factors were classified into risk group. The leukocytes counts and the serum concentrations of amylase and lipase were measured at admission and blood glucose and body mass index (BMI) were also measured at admission and discharge. Relief of abdominal pain was determined by the day when the patient was not taken analgesics for abdominal pain. The fasting period was considered duration before ingestion of liquid diet. Generally, the duration of hospitalization was defined as the periods from admission to discharge but in the patients with acute gallstone pancreatitis who went through a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the period only up to the date of surgery was included in the hospitalization period and the period after surgery was excluded from the hospitalization period. We performed upper gastrointestinal endoscopy during the admission period.

For statistical analyses, t-tests and chi-square tests were conducted using SPSS software (version 12; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and p<0.05 was considered to be significant. When the result did not satisfy normality, we analysed the results using Mann-Whitney tests and Wilcoxon signed ranks tests. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of clinical study of Gangneung Asan Hospital.

RESULTS

1. Baseline characteristics

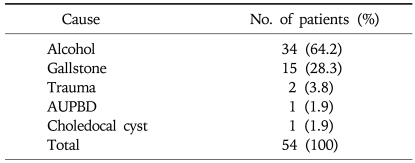

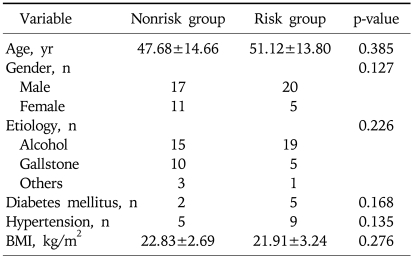

Among the enrolled 53 patients, male patients were 37 cases (69.8%) and the mean age was 49±14 (range, 19 to 85) year old. The most common cause of acute pancreatitis was alcohol abuse (n=34, 64.2%), followed by gallstone (n=15, 28.3%). Other causes consisted of trauma in 2 cases, anomalous union of pancreaticobiliary duct in 1 case, and choledocal cyst in 1 case (Table 1). Among 53 patients, 25 patients were risk group and 28 patients were nonrisk group. There were no differences in age, gender, etiology of acute pancreatitis, BMI between two groups (p>0.05) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Etiology of Acute Pancreatitis

AUPBD, anomalous union of pancreaticobiliary duct.

Table 2.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics between Nonrisk and Risk Groups

Data expressed as mean±standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index.

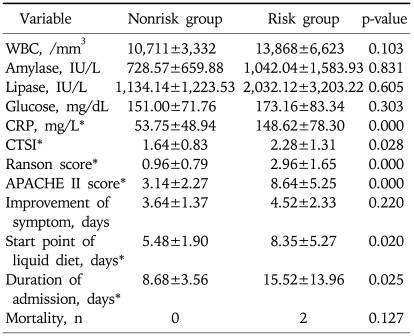

2. Univariate analysis between the risk group and the nonrisk group

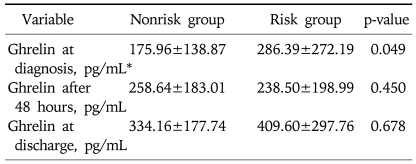

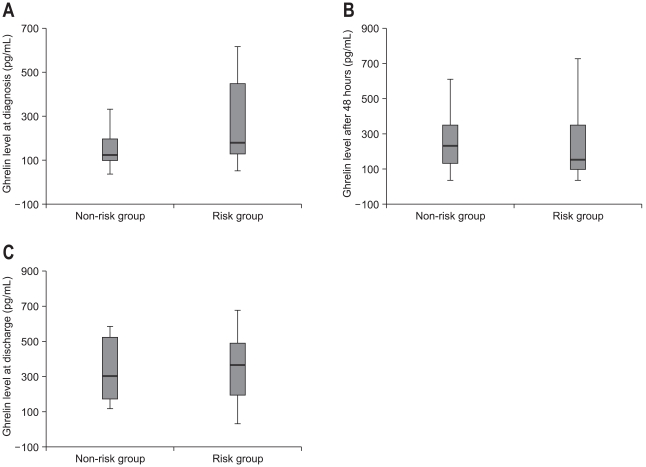

There were no differences in leukocytes count, serum amylase and lipase, and serum glucose concentration between two groups (p>0.05). Mean CRP were 148.62±78.30 and 53.75±48.94, mean CTSI were 2.28±1.31 and 1.64±0.83, mean Ranson score 2.96±1.65 and 0.96±0.79, and mean APACHE II scores 8.64±5.25 and 3.14±2.27 in risk group and nonrisk group, respectively. Although the duration of abdominal pain was not significantly different between the two groups but the fasting period and the duration of hospitalization were significantly longer in the risk group (8.35±5.27 vs 5.48±1.90 p=0.020 and 15.52±13.96 vs 8.68±3.56, p=0.025, respectively). There were 2 cases of death in risk group but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p=0.127) (Table 3). The serum ghrelin concentration at admission was significantly higher in the risk group (286.39±272.19 vs 175.96±138.87 pg/mL, p=0.049), but the ghrelin concentrations measured at 48 hours after admission and the ghrelin concentration at discharge were not significantly different between the two groups (238.50±198.99 vs 258.64±183.01 pg/mL, p=0.450 and vs 409.60±297.76 vs 334.16±177.74 pg/mL, p=0.678, respectively) (Table 4, Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Comparison of Laboratory Data, Prognostic Index, and Clinical Data between Nonrisk and Risk Groups

Data expressed as mean±standard deviation.

CRP, C-reactive protein; APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation.

*p<0.05.

Table 4.

Comparison of Ghrelin Concentration between Nonrisk and Risk Groups

Data expressed as mean±standard deviation.

*p<0.05.

Fig. 1.

The serum ghrelin concentration is significantly higher in the risk group than in the nonrisk group at admission (p=0.049) (A), but it does not differ significantly between the two groups at 48 hours after admission (p=0.450) (B) or at discharge (p=0.678) (C).

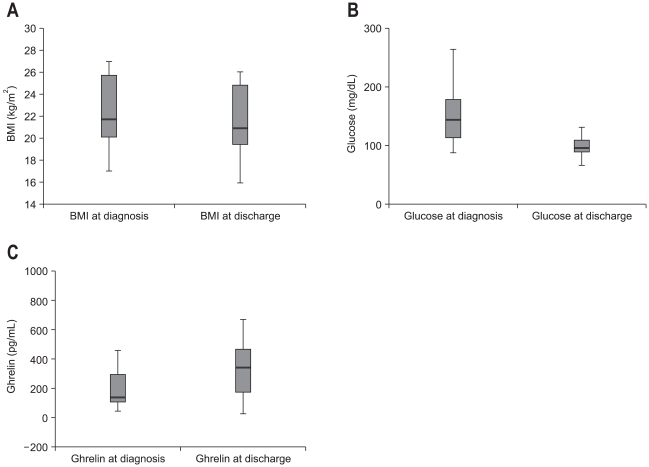

3. Changes in serum ghrelin concentration after diagnosis

Serum ghrelin concentration at discharge was measured in 25 patients among the patients analyzed in this study. Changes in BMI, serum glucose level, and serum ghrelin concentration between at admission and at discharge were analyzed. BMI decreased at that time of discharge than at admission significantly (22.44±2.85 vs 21.50±2.95 kg/m2, p=0.002) and so was serum glucose concentration (156.26±56.66 vs 110.05±48.31 mg/dL, p=0.000). On the other hand, serum ghrelin concentration was significantly higher at that time of discharge (240.65±247.96 vs 369.41±254.27 pg/mL, p=0.001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Changes in body mass index (BMI) and glucose and ghrelin concentrations between at the diagnosis and at discharge. (A) BMI is significantly higher at the diagnosis than at discharge (p=0.002). (B) Glucose concentration is significantly higher at the diagnosis than at discharge (p=0.000). (C) Ghrelin concentration is significantly lower at the diagnosis than at discharge (p=0.001).

4. Univariate analysis of serum ghrelin concentration by the etiology

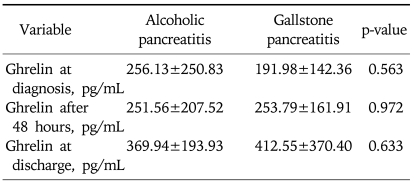

The patients included in this study were divided into alcohol group and gallstone group by etiology. The serum ghrelin concentrations between alcohol group and gallstone group were compared for statistical analysis. The serum ghrelin concentration at admission showed a tendency to lower in the gallstone group than in the alcohol group but it was not statistically significant (256.13±250.83 vs 191.98±142.36 pg/mL, p=0.563). There was no statistically significant difference in the serum ghrelin concentration at 48 hours after admission and at discharge (251.56±207.52 vs 253.79±161.91 pg/mL, p=0.972 and 369.94±193.93 vs 412.55±370.40 pg/mL, p=0.633, respectively) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of Ghrelin Concentration between Alcoholic Pancreatitis and Gallstone Pancreatitis

DISCUSSION

Ghrelin is a peptide hormone for growth hormone secretagogue receptor. About 60-70% of circulating ghrelin is secreted by the X/A-like cells existing in oxyntic glands of the gastric mucosa and most of the remainder derived from the small intestine.14 Since ghrelin was found in 1999 from stomach extract, various physiologic functions of ghrelin has been reported. Ghrelin has a direct effect on pituitary somatotroph cells in vitro and acts synergistically with growth hormone-releasing hormone to stimulate growth hormone secretion. Also, ghrelin promotes appetite to induce food intakes and increases when the body weight has been reduced thereby serving an important role in maintaining energy homeostasis.15-17 And ghrelin induces increased gastrointestinal motility and increased gastric acid secretion which may be relevant in processing ingested foods.18,19 Two studies suggest that ghrelin prevents the remodeling of the left ventricle, reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac outputs thereby showing beneficial effects in patients with heart failure.20,21 According to an animal study, intraperitoneal administration of ghrelin attenuates pancreatic damage in caerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats. Protective effect of ghrelin seems to be related to the inhibition in inflammatory process. The diminished liberation of IL-1beta, the inhibition of leukocyte infiltration into pancreas tissues, and the attenuation of decreased synthesis of DNA in pancreas are probably the major mechanisms involved in beneficial effect of ghrelin on pancreas integrity.10 In other animal study, application of ghrelin into the right cerebral ventricle of the rats subjected to caerulein-induced pancreatitis resulted in the significant reduction of pancreatic edema and morphological signs of acute pancreatitis. This was accompanied by marked increase of superoxide dismutase amount in the pancreatic tissue and increase of growth hormone blood level. It is likely that the inhibition of reactive oxygen species production and the beneficial effect of growth hormone such as tissue regeneration and maintenance of integrity could improve the natural defense mechanism against pancreatic tissue injury.22 There was a recent study which showed that ghrelin concentration increased significantly when the patients with acute pancreatitis recovered.11 This is also observed in our study.

However, careful interpretation of the test result is needed because the blood concentration of ghrelin is changed by various factors. Blood concentration of ghrelin is increased by fasting or weight reduction and it is decreased by food intake or weight gain.8,23 In our study, blood glucose and BMI were higher at admission compared to that at discharge, thus there is a possibility that these factors affected the serum ghrelin concentration. Also, there is a possibility that the ghrelin concentration at admission would have been low since blood collections at admission were done regardless of the diet states of patients. These may be limitations of this study. And it is known that blood concentration of ghrelin is affected by accompanying states. For example, it increases in cachexic states such as heart failure or malignancy and decreases in hyperthyroidism, gastric ulcer, and post-operative state such as gastric bypass surgery and total gastrectomy. Therefore, the patients accompanied by the above mentioned states were excluded from this study.24,25

Even though our study results demonstrate that the ghrelin concentration at admission was significantly higher in the patients with risk factors for severe acute pancreatitis, it is limited to use ghrelin concentration to evaluate the severity of acute pancreatitis instead of other prognostic factors because it is not easy to measure ghrelin concentration in the laboratory and blood concentration of ghrelin is affected by various factors mentioned above. But, we may consider that intensive and more aggressive management is required in the patients with acute pancreatitis whose ghrelin level increases at admission.

Given the report that the ghrelin concentration increased in the recovery period of patients with acute pancreatitis, it is supposed that ghrelin concentration may be low in acute phase of pancreatic damages. Also in our study, the ghrelin concentration at admission was significantly lower than that at discharge when the patients were analyzed regardless of risk factor. When the patients with acute pancreatitis were divided into risk group and nonrisk group for statistical analysis, the ghrelin concentration at admission was significantly lower in the nonrisk group but there was no significant difference in ghrelin concentration between the two groups after 48 hours and at discharge. The reason may be explained by the result that the frequency of acute pancreatitis caused by alcohol abuse, although not statistically significant, was higher in the risk group and most of the patients with acute pancreatitis related to alcohol abuse chronically took alcohol thus their pancreases have been damaged for a relatively long time before the admission. And we may suppose that the more acute pancreatitis is severe, the more is pancreas likely to have been damaged for a longer time. Considering the reports that ghrelin has the protective effect on pancreas, it can be thought that ghrelin concentration increases as a healing process for more prolonged and severe damage of pancreas. Besides, although not statistically significant, the ghrelin concentration at admission was lower in patients with acute pancreatitis caused by gallstone than alcohol abuse. This may be owing to the reason that the patients with gallstone pancreatitis were healthy before the onset of disease and they visited the hospital relatively early after the onset of disease. That is, it can be thought that the blood concentration of ghrelin increases after the pancreas is damaged regardless of the cause of acute pancreatitis and ghrelin provides protective effect for damaged pancreas. However, it cannot be said whether blood ghrelin concentration would decrease after pancreatitis is completely recovered because additional blood samples are not taken after discharge. The subsequent studies should be conducted later. Also, further studies are necessary to investigate beneficial effect on damaged pancreas in human.

In summary, the serum ghrelin concentration at admission was significantly higher in the patient with risk factors for severe acute pancreatitis than in the patient without the risk factor. We postulate that the increased blood concentration of ghrelin is associated with healing process of damaged pancreas in human.

References

- 1.Ranson JH, Rifkind KM, Roses DF, Fink SD, Eng K, Spencer FC. Prognostic signs and the role of operative management in acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;139:69–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson C, Heath DI, Imrie CW. Prediction of outcome in acute pancreatitis: a comparative study of APACHE II, clinical assessment and multiple factor scoring systems. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1260–1264. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dominguez-Munoz JE, Carballo F, Garcia MJ, et al. Clinical usefulness of polymorphonuclear elastase in predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis: results of a multicentre study. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1230–1234. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gudgeon AM, Heath DI, Hurley P, et al. Trypsinogen activation peptides assay in the early prediction of severity of acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 1990;335:4–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90135-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenner S, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw A, et al. Urinary trypsinogen activation peptide (TAP) predicts severity in patients with acute pancreatitis. Int J Pancreatol. 1997;21:105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02822381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puolakkainen P, Valtonen V, Paananen A, Schroder T. C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum phospholipase A2 in the assessment of the severity of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1987;28:764–771. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.6.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balthazar EJ, Robinson DL, Megibow AJ, Ranson JH. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis. Radiology. 1990;174:331–336. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.2.2296641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tritos NA, Kokkotou EG. The physiology and potential clinical applications of ghrelin, a novel peptide hormone. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:653–660. doi: 10.4065/81.5.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wierup N, Svensson H, Mulder H, Sundler F. The ghrelin cell: a novel developmentally regulated islet cell in the human pancreas. Regul Pept. 2002;107:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dembinski A, Warzecha Z, Ceranowicz P, et al. Ghrelin attenuates the development of acute pancreatitis in rat. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;54:561–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu B, Liu X, Tang C. Change of plasma ghrelin level in acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2006;6:531–535. doi: 10.1159/000096976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379–2400. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Triester SL, Kowdley KV. Prognostic factors in acute pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:167–176. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200202000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Date Y, Kojima M, Hosoda H, et al. Ghrelin, a novel growth hormone-releasing acylated peptide, is synthesized in a distinct endocrine cell type in the gastrointestinal tracts of rats and humans. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4255–4261. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hataya Y, Akamizu T, Takaya K, et al. A low dose of ghrelin stimulates growth hormone (GH) release synergistically with GH-releasing hormone in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:4552. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.8002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wren AM, Seal LJ, Cohen MA, et al. Ghrelin enhances appetite and increases food intake in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5992. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, et al. Plasma ghrelin levels after diet-induced weight loss or gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1623–1630. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tack J, Depoortere I, Bisschops R, et al. Influence of ghrelin on interdigestive gastrointestinal motility in humans. Gut. 2006;55:327–333. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.060426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuda Y, Tanaka T, Inomata N, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:905–908. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagaya N, Uematsu M, Kojima M, et al. Chronic administration of ghrelin improves left ventricular dysfunction and attenuates development of cardiac cachexia in rats with heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:1430–1435. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.095575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagaya N, Miyatake K, Uematsu M, et al. Hemodynamic, renal, and hormonal effects of ghrelin infusion in patients with chronic heart failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5854–5859. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaworek J. Ghrelin and melatonin in the regulation of pancreatic exocrine secretion and maintaining of integrity. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57(Suppl 5):83–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leite-Moreira AF, Soares JB. Physiological, pathological and potential therapeutic roles of ghrelin. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:276–288. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katergari SA, Milousis A, Pagonopoulou O, Asimakopoulos B, Nikolettos NK. Ghrelin in pathological conditions. Endocr J. 2008;55:439–453. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k07-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isomoto H, Ueno H, Nishi Y, et al. Circulating ghrelin levels in patients with various upper gastrointestinal diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:833–838. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2648-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]