Abstract

Background/Aims

Studies have investigated the use of different types of radiofrequency capsules for comparison or sequential capsule endoscopy, but none have compared the MiroCam device - which utilizes a novel data transmission technology - with other capsules. This study compared the feasibility of sequential capsule endoscopy using the MiroCam and PillCam SB devices, which employ different transmission technologies.

Methods

Patients with diseases requiring capsule endoscopy were enrolled. After a 12-hour fast, one randomly selected capsule was swallowed. The second capsule was swallowed once fluoroscopy had indicated that the first capsule had migrated below the gastric outlet.

Results

The total operating time in 24 patients was 702±60 min (mean±SD) for the MiroCam and 446±28 min for the PillCam SB (p<0.0001). The rate of a complete examination to the cecum was 83.3% for the MiroCam and 58.3% for the PillCam SB (p=0.031). Diagnostic yields for the MiroCam, PillCam SB, and sequential capsule endoscopy were 45.8%, 41.7%, and 50.0%, respectively. The agreement rate between the two capsules was 87.5%, with a κ value of 0.74. Electrical interference in data transmission between the two capsules was not observed, but temporary visual interferences were observed in seven patients (29.2%).

Conclusions

Sequential capsule endoscopy with the MiroCam and PillCam SB produced slight but nonsignificant increases in the diagnostic yield, and the two capsules did not exhibit electrical interference. A larger trial is necessary for elucidating the usefulness of sequential capsule endoscopy.

Keywords: Capsule endoscopy, Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, Feasibility study, Diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

M2A (renamed PillCam SB; Given Imaging, Yokneam, Israel) was the first developed wireless capsule endoscope providing noninvasive and visual diagnosis of small bowel disease. Capsule endoscopy (CE) provides great diagnostic value in various small bowel diseases compared to conventional modalities.1,2 Recently, other new wireless capsule endoscopes including EndoCapsule (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and MiroCam (IntroMedic, Seoul, Korea), have become available for small bowel examination in clinical situations.3,4 Among them, MiroCam received both Korean market clearance and the Conformité Européenne (CE) mark in 2007.

MiroCam uses a novel technology for data transmission, Human Body Communication, which is different from the radiofrequency telemetry of PillCam SB and EndoCapsule.3 Human Body Communication uses the human body as a conductive medium for data transmission from the capsule endoscope to electrodes attached to the body.4 As a result, this technology spends less electrical power for data transmission, confers a longer operating time with a small size (24×11 mm), and provides higher-resolution images (320×320 pixels at 3 frames per second) compared to PillCam SB.4 Longer operating times may reduce the rate of incomplete examinations to the cecum by CE, which has been reported to be 17-25% throughout the lifetime of the battery.5,6 However, no prospective randomized trial has been reported in diseased patients to compare the operating times, complete examination rates to the cecum, and diagnostic yields between MiroCam and PillCam SB.

The concept of sequential CE originated from previous studies on repeat examinations with CE. Repeat CE and second-look CE in selected patients with non-diagnostic results during their first CE have identified additional new findings in patients with recurrent or persistent obscure gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and iron deficiency anemia.7-9 Therefore, sequential CE with two capsules in all subjects could increase diagnostic yield, compared to a single CE.

We tested the feasibility of sequential CE utilizing MiroCam and PillCam SB, and also compared two capsule endoscopes in a prospective randomized design.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

Patients with an indication for CE, such as obscure GI bleeding, chronic abdominal pain, and chronic diarrhea were enrolled. Patient ages ranged from 20 to 75 years. Patients with a history of intestinal obstruction and those with swallowing difficulties were excluded. The patients with obscure GI bleeding underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy prior to CE examination. Approval was obtained from the institutional review board of Severance Hospital (Seoul, Korea). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

2. Procedures of sequential CE

Enrolled patients fasted for 12 hours, and on the day of examination, swallowed 30 mL of simethicone 30 minutes before the first CE. The order of swallowing two capsules was randomized. Eight antenna or electrodes were attached to the abdominal wall according to the manufacturer's instructions. The first capsule endoscope was swallowed with water, and its location was traced under fluoroscopy at 30 minutes intervals. After the first capsule endoscope passed through the gastric outlet, the second capsule endoscope was ingested with water. Both the antennas and electrodes were detached simultaneously after sufficient battery time of MiroCam or PillCam SB. Data from each capsule endoscope were uploaded to respective computer installed with the appropriate reading software.

3. Data analysis

Two gastroenterologists interpreted the images from each capsule endoscope, and were kept from knowing the results from the other capsule endoscope. When two gastroenterologists reviewing the same patient were not in agreement, a third gastroenterologist assisted in the interpretation of the images. The readers were not completely blinded because the reading programs were clearly distinct. The personal history and information from other modalities were not informed to the readers. Abnormal findings of CE images were labeled according to the Capsule Endoscopy Structured Terminology (CEST).10 We classified mucosal lesions of the small bowel into three categories. Significant abnormal findings were defined as mucosal lesions strongly associated with disease. Abnormal findings were defined as any mucosal lesion. Clinical diagnoses were made based on clinical signs and symptoms of the patients and interpretation of images with significant abnormal findings. Diagnostic yield was calculated as the number of patients with significant abnormal findings divided by the number of all patients.

Operating times of the two capsule endoscopes were compared with the paired t-test, and completion rates and diagnostic yields were compared using McNemar test. The kappa test was used to measure an agreement between MiroCam and PillCam SB. p-values were considered to be significant when they were less than 0.05.

RESULTS

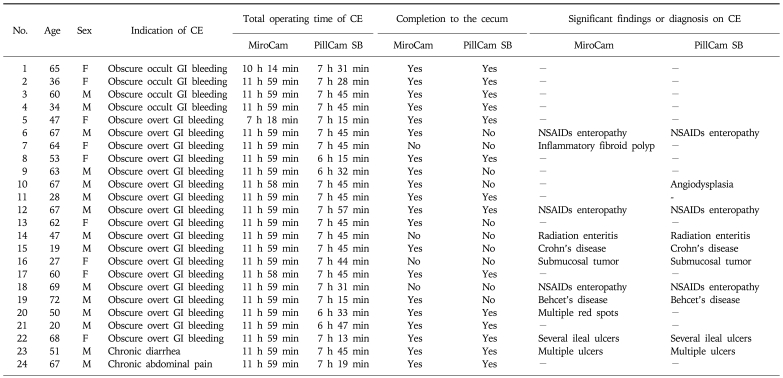

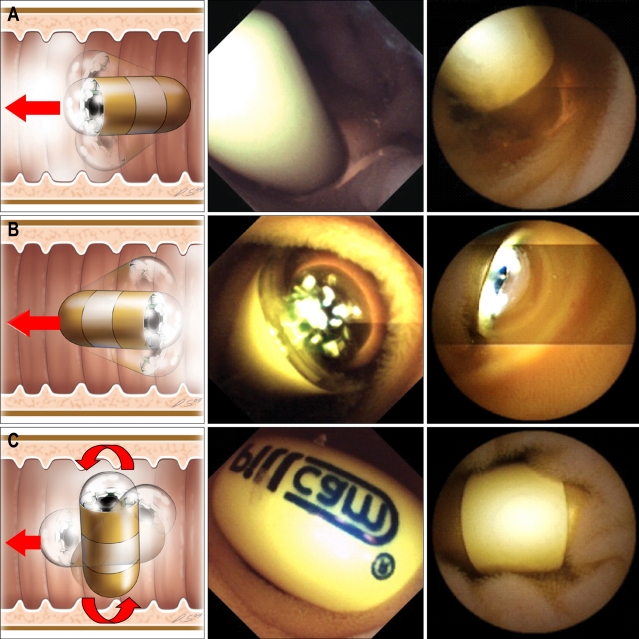

Twenty four patients were enrolled between June 2007 and January 2009 (Table 1). The mean age was 52.6±16.7 years. Indications of CE were obscure GI bleeding in 22 patients (91.7%) with a lowest hemoglobin concentration of mean 8.2±2.0 g/dL, chronic diarrhea in one patient, and abdominal pain in one patient. The mean interval time of ingestion between MiroCam and PillCam SB was 3 h 7 min±3 h 58 min. The mean total operating times of MiroCam and PillCam SB were 11 h 44 min±1 h, and 7 h 26 min±28 min (p<0.0001), respectively. Completion rates to the cecum by MiroCam and PillCam SB was 83.3% and 58.3%, respectively (p=0.031). Diagnostic yields of MiroCam and PillCam SB were 45.8% and 41.7% (p>0.05), respectively. The sequential CE of two capsules slightly increased the diagnostic yield to 50.0% compared to a single CE, but this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2). The agreement rate between MiroCam and PillCam SB was 87.5% with a kappa value of 0.74 (Table 3). No complication related to CE occurred. Interference of electrical transmission between MiroCam and PillCam SB was not observed in any patient, and images were captured and transferred completely during the lifetime of the battery. However, temporary visual interferences disturbing front visual fields due to physical obstruction of the capsule were observed in seven patients (29.2%) (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients and Technical Information of the MiroCam and PillCam SB Capsule Endoscopes

CE, capsule endoscopy; GI, gastrointestinal; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

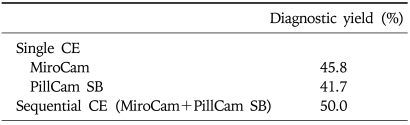

Table 2.

Diagnostic Yields for Detecting Significant Abnormal Findings in Capsule Endoscopy

CE, capsule endoscopy.

Table 3.

Agreement between the MiroCam and PillCam SB

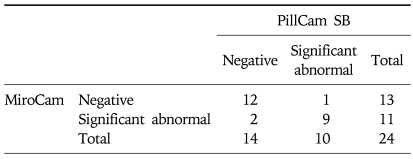

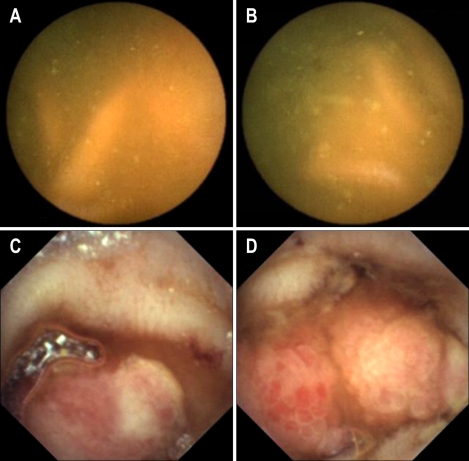

Fig. 1.

Temporary visual interferences and tumbling movements of the MiroCam and PillCam SB. Oblique-forward movement (A), oblique-reverse movement (B), and perpendicular and rotational movements (C).

DISCUSSION

The concept of second-look CE was first reported in 2004.8 "Repeat CE" have revealed new findings not previously observed in prior CE in patients with obscure GI bleeding in two studies.7,9 The second-look CE or repeat CE was performed on selected patients with negative finding in prior CE, but the sequential CE was a procedure of continuous swallowing two capsules in all patients. The sequential CE has been prospectively attempted in three studies.11-13 One of them, using two same capsules of PillCam SB, reported that the second capsule found 10% more new lesions in 41 patients with obscure GI bleeding.13 In other trial, the combination of PillCam SB and EndoCapsule showed increase in the diagnostic yield from 33.3% or 47.1% of each single capsule endoscope up to 52.9% in patients with obscure GI bleeding.12 In another study, the combination of PillCam SB (65%) and EndoCapsule (72.5%) revealed 77.5% of the detection rate of abnormal lesions in 40 patients with obscure GI bleeding.11 Our study showed that the combination of MiroCam and PillCam SB had 50% of the detection rate in 22 patients with obscure GI bleeding. However, we did not prove the significant efficacy of sequential CE, compared to single CE. Further trials for investigation of the efficacy of sequential CE will be needed.

Since the development of M2A, several different types of capsule endoscopes have become commercially available. EndoCapsule was developed by Olympus Medical System, and utilizes charged coupled device (CCD) technology for the image sensor, rather than the complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) of PillCam SB and MiroCam.3 EndoCapsule had a comparable diagnostic yield to PillCam SB for obscure GI bleeding in two randomized trials.11,12 In addition, EndoCapsule had a significantly longer recording time than PillCam SB (591 min vs 471 min, respectively), and a higher frequency of identifying abnormal findings than PillCam SB (47.1% vs 33.3%).11,12 MiroCam uses a different technology for data transmission from PillCam SB and EndoCapsule. Our study was the first pilot study to directly compare MiroCam and PillCam SB, and demonstrated that MiroCam had longer operating time than PillCam SB, and a comparable diagnostic yield to PillCam SB. Our study showed the relatively low diagnostic yields for obscure GI bleeding (45.5% in MiroCam and 40.9% in PillCam SB among 22 patients), but the low values are close to rates of other studies.1,5

EndoCapsule does not electrically interfere with PillCam SB, even when operating in the same patient, although both the capsules use the same radiofrequency communication for data transmission.11,12 MiroCam also did not interact with PillCam SB in our study. Two of the same capsules will cause electrical interference when operating simultaneously in the same patient on the same day. Therefore, a long lag-time greater than the battery lifetime of the capsule is needed to successfully perform sequential CE with two same capsules.13 Sequential CE of two different capsules can be performed in the same day, after a short time interval to avoid visual interference. Moreover, sequential CE may increase the detection rate of abnormal findings in the small intestine.

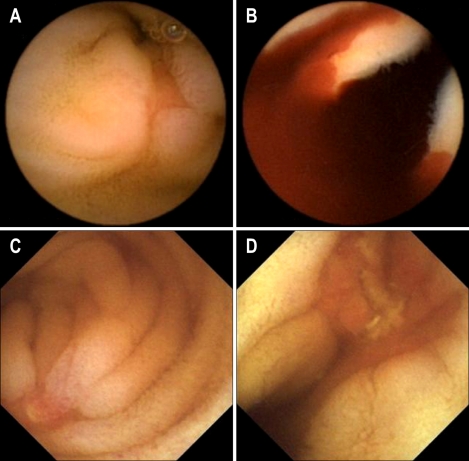

In our study, MiroCam had a higher complete examination rate to the cecum than PillCam SB. The completion rate of PillCam SB was lower than those in other reports.6 However Rastogi et al.14 reported 50% of incompletion rate of PillCam SB. This low rate might be caused by sampling bias. If an abnormal lesion is located in the distal ileum, MiroCam is more likely to detect it than PillCam SB. For example, in one patient, MiroCam found a large polypoid mass at 11 h 31 min in the distal ileum, whereas PillCam SB was unable to detect the lesion because its short battery lifetime expired after 7 h 45 min (Fig. 2). The risk factors for incomplete examination of CE in the small bowel are long gastric transit time, previous small bowel surgery, hospitalization, and poor bowel cleansing in a retrospective study using PillCam SB.15,16 Sufficiently long operating times of capsule endoscope can overcome some portion of these risk factors.

Fig. 2.

In patient 7, the MiroCam reveales a polypoid mass in the distal ileum at 11:31 (C, D), but the PillCam SB is not able to capture the lesion due to its shorter battery life (A, B).

Indications of CE include obscure GI bleeding, small bowel Crohn's disease, small bowel tumors, celiac disease and abdominal pain. In our study, obscure GI bleeding was a major indication (91.7%) of CE although all indications of CE were included. High prevalence of obscure GI bleeding might cause this selection bias. In addition, other indications, small bowel Crohn's disease, small bowel tumors, celiac disease and abdominal pain, have low diagnostic rate of positive findings on CE, and therefore a lot of subjects may be necessary for evaluation of efficacy of sequential CE.17-19

It is well documented that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) can cause small bowel mucosal injury, such as red spot, erosion, ulcer and stricture, since CE has become available for evaluation of small bowel.20 This NSAID-induced enteropathy is often found as an origin of obscure GI bleeding in patient taking NSAID. Recently, aspirin is also suggested to cause enteropathy similar to NSAID-induced enteropathy although its association of cause and effect remains clarified.21 In our study, three of six patients taking aspirin were diagnosed with NSAID-induced enteropathy. One patient taking aceclofenac had negative finding in small bowel on CE.

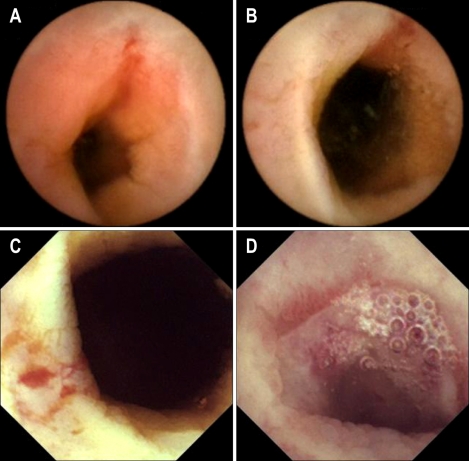

The swallowing order of two capsules did not cause any significant difference in operating time and diagnostic yield (The data were not shown in the Result Section). However, one capsule could detect active bleeding focus, while the other capsule could detect an ulcer without current bleeding at the same site. For example, PillCam SB was the second capsule in one patient (Fig. 3), and it detected active bleeding in the small intestine; however, MiroCam, the first capsule swallowed 1 h 50 min before, found an ulceration without current bleeding at the same site.

Fig. 3.

In patient 5, the PillCam SB reveales active bleeding from an ulcer (A, B), but the MiroCam showes only ulcer without active bleeding at the distal ileum, which is suspected to be the same site as in A and B (C, D).

In our study, two capsules were ingested separately to avoid visual interference, but in seven patients, the two capsule endoscopes were intermittently close to each other in the small bowel to partially interrupt the visual field of one or both by physical obstruction, or by light when the light-emitting diode (LED) was on, as shown Fig. 1. Two capsule endoscopes can interfere with each other visually if the times of ingestion are not adequately separated. Cave et al.12 reported intermittent visualization of the other capsule endoscope with a 40-minute interval between ingestion. To prevent the encounter of two operating capsule endoscopes, the time interval for ingestion should be at least 1 hour.

The tumbling movement of capsule endoscopes was first observed in a comparison study of EndoCapsule and PillCam SB.12 The present study showed that the tumbling movements included oblique inclination and rotation, and that the capsule endoscope rapidly changed its position in the small intestine. The tumbling movements are illustrated in Fig. 1. When the capsule endoscope is positioned randomly, it causes a blind area in the small bowel mucosa that decreases the diagnostic yield.12

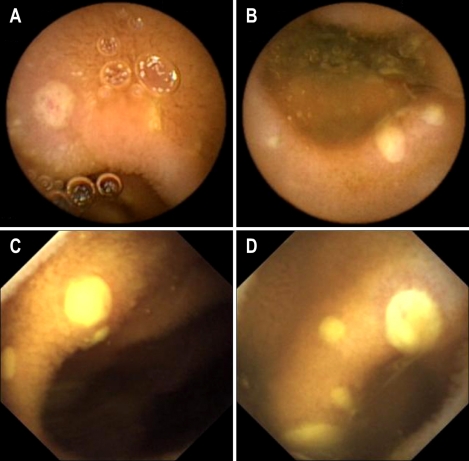

Our study has two limitations. Number of the enrolled patients were small although of a pilot study. A head-to-head prospective study between MiroCam and PillCam SB has not been previously evaluated, and therefore we tried to compare two capsule endoscopes. The results of our study showed that MiroCam was comparable to PillCam SB in diagnostic yield; however larger scale trials are necessary to compare two capsule endoscopes. The other problem is the failure to blind the reviewer of CE images. The reviewers were gastroenterologists and employed in the same hospital where our study was performed, but they were prohibited from participation in care of the enrolled patients and were not given information about the patients. However, the complete blindness could not be achieved because the reading programs of two capsule endoscopes were obviously different, and the patients' names were showed on the reading programs. In addition, evaluation of image quality was not performed in our study (Figs 4 and 5).

Fig. 4.

Patient 14 has a history of pelvic radiotherapy. The PillCam SB (A, B) and MiroCam (C, D) reveales stricture with ulcer, suggesting a bleeding focus.

Fig. 5.

In patient 21, the PillCam SB (A, B) and MiroCam (C, D) reveales multiple ulcers.

In conclusion, sequential CE with MiroCam and PillCam SB showed slight increase in the diagnostic yield, but it was not statistically significant. Two capsule endoscopes did not cause interference from each other. Further trails to test the efficacy of sequential CE using two different capsule endoscopes will be necessary. As subsidiary findings, MiroCam had longer operating time, higher completion rate, and comparable diagnostic yield, compared to PillCam SB in the small bowel disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported in part by a grant from the 21st Century Frontier R&D Project sponsored by the Korean Ministry of Knowledge Economy, by a grant from the Brain Korea 21 Project for Medical Sciences of Yonsei University College of Medicine, and by IntroMedic Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea. Special thanks go to Jin Suk Jang of Yonsei Clinical Trial Center, Seoul, Korea, for helpful cooperation and Dong-Su Jang for the illustrations.

References

- 1.Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, et al. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407–2418. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L. Meta-analysis: capsule enteroscopy vs. conventional modalities in diagnosis of small bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:595–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gheorghe C, Iacob R, Bancila I. Olympus capsule endoscopy for small bowel examination. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bang S, Park JY, Jeong S, et al. First clinical trial of the "MiRo" capsule endoscope by using a novel transmission technology: electric-field propagation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pennazio M, Eisen G, Goldfarb N. ICCE consensus for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1046–1050. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Franchis R, Avgerinos A, Barkin J, Cave D, Filoche B. ICCE consensus for bowel preparation and prokinetics. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1040–1045. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones BH, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK, et al. Yield of repeat wireless video capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1058–1064. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bar-Meir S, Eliakim R, Nadler M, et al. Second capsule endoscopy for patients with severe iron deficiency anemia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:711–713. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viazis N, Papaxoinis K, Vlachogiannakos J, Efthymiou A, Theodoropoulos I, Karamanolis DG. Is there a role for second-look capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding after a nondiagnostic first test? Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:850–856. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korman LY, Delvaux M, Gay G, et al. Capsule endoscopy structured terminology (CEST): proposal of a standardized and structured terminology for reporting capsule endoscopy procedures. Endoscopy. 2005;37:951–959. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann D, Eickhoff A, Damian U, Riemann JF. Diagnosis of small-bowel pathology using paired capsule endoscopy with two different devices: a randomized study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1041–1045. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cave DR, Fleischer DE, Leighton JA, et al. A multicenter randomized comparison of the Endocapsule and the PillCam SB. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimble JS, Chak A, Isenberg GA, Cooper GS, Wong RC. Variation in diagnostic yield of back-to-back capsule endoscopy in obscure GI bleeding: final results. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:AB185. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rastogi A, Schoen RE, Slivka A. Diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes of capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:959–964. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westerhof J, Weersma RK, Koornstra JJ. Risk factors for incomplete small-bowel capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endo H, Matsuhashi N, Inamori M, et al. Abdominal surgery affects small bowel transit time and completeness of capsule endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1066–1070. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shim KN, Kim YS, Kim KJ, et al. Abdominal pain accompanied by weight loss may increase the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy: a Korean multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:983–988. doi: 10.1080/00365520600548974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fry LC, Carey EJ, Shiff AD, et al. The yield of capsule endoscopy in patients with abdominal pain or diarrhea. Endoscopy. 2006;38:498–502. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rondonotti E, Pennazio M, Toth E, et al. Small-bowel neoplasms in patients undergoing video capsule endoscopy: a multicenter European study. Endoscopy. 2008;40:488–495. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higuchi K, Umegaki E, Watanabe T, et al. Present status and strategy of NSAIDs-induced small bowel injury. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:879–888. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endo H, Hosono K, Inamori M, et al. Characteristics of small bowel injury in symptomatic chronic low-dose aspirin users: the experience of two medical centers in capsule endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:544–549. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0040-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]