Abstract

Background/Aims

Little information is available on whether the speed of eating differs between individuals with and without dyspepsia, mainly because controlled studies are usually not feasible.

Methods

A survey was applied to 89 individuals with relatively controlled eating patterns, using questionnaires that assessed eating time and functional dyspepsia (FD) based on the Rome III criteria.

Results

The prevalence of FD was 12% (11 of 89 participants), and 7% (6 of 89) were diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The proportion of individuals reporting that they ate their meals rapidly was higher for those with FD than for those without FD or GERD (control) (46% vs 17%, p=0.043), as was the reported eating speed (7.1±1.5 vs 5.8±2.0 [mean±SD], p=0.045; visual analog scale on which a higher score indicated faster eating). However, the measured eating time did not differ significantly between FD and controls (11.0±2.8 vs 12.8±3.3 minutes, p=0.098). The proportion of individuals who ate their meals within 13 minutes was significantly higher for those with FD than for controls (91% vs 51%, p=0.020).

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that eating speed affects dyspepsia. Further studies are warranted.

Keywords: Diet habits, Eating speed, Functional dyspepsia

INTRODUCTION

The study on role of dietary factors in causing dyspeptic symptoms has received little attention.1 However, many patients with functional dyspepsia (FD) report that their symptoms are related to the ingestion of food, and patients are often advised to modify their dietary habits.1,2 As FD is a heterogeneous disorder, 'diet' might play a role in numerous ways in a given individual.1 It has been challenging to determine the relevant dietary factors that are associated with FD. Studies that have investigated eating patterns (meal size, frequency, eating speed) have reported conflicting results with regard to whether eating patterns of patients with functional dyspepsia differ from healthy controls.2-4 One problem with such studies is that 'diet' is a factor that is very difficult to 'control' for the purpose of a study.

In this study, we evaluated a group of individuals with relatively 'controlled' eating patterns. Participants in this study were cadets (sophomores and juniors) studying at the Armed Forces Nursing Academy. The unique advantage of this situation is that the cadets have very uniform lifestyles and very similar eating patterns. All cadets live in a dormitory, awake at the same time, have regular exercise in the morning and evening, do not smoke, and do not drink alcohol during the school semester. They have breakfast, lunch and supper at the same time and eat the same food. The most pronounced difference in the eating patterns is the speed with which they eat their food; since they eat the same food at the same time. This provides a unique opportunity to study the impact of the speed of eating on dyspeptic symptoms. In this study, we investigated the association between eating speed and functional dyspepsia in this relatively 'controlled' environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Subjects

We performed a survey on 95 cadets (sophomores and juniors) studying at the Armed Forces Nursing Academy of the Republic of Korea Army. Among these cadets, 89 (94%) completed the survey. All participants were women, with a median age of 22 (range, 20 to 25). The body mass index (kg/m2) was 20.5±1.6. They were all living in a dormitory, and had very uniform lifestyles. They awoke early in the morning, had regular exercise in the morning and evening, had three meals per day at regular time intervals including breakfast, and ate the same food for a year or two. Smoking was prohibited in this environment, so there were no participants that smoked. Alcohol ingestion was also prohibited during the school semester.

2. Protocol

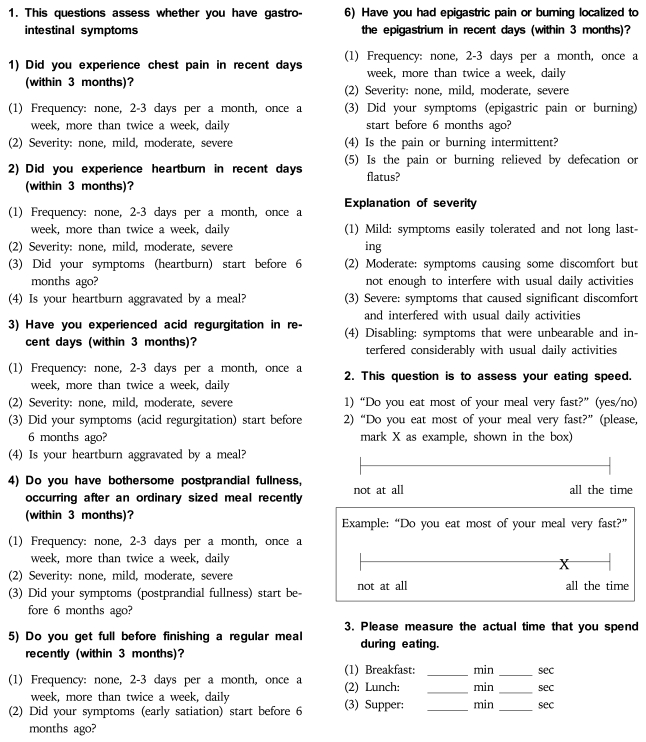

The survey was performed on two occasions. On the first-day, the investigator provided the participants with a standardized explanation of the questions and definitions of symptoms, and asked the cadets to complete the questionnaire that was designed to diagnose functional dyspepsia. The questionnaire was originally developed by the Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, available at www.ksgm.org (Korean), and was modified by the investigators by adding questions regarding the speed of eating (Appendix 1). Following the survey, participants were asked to measure and record the actual time that was spent for eating (breakfast, lunch and supper) for a day. After that the same questionnaire was repeated to validate the questionnaires. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice.

3. Diagnosis of functional dyspepsia

The diagnosis of functional dyspepsia was made using the Rome III criteria.5 When an individual responded that they had bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain or burning for the last three months, with symptom onset at least six months before the survey, then individuals were diagnosed as having functional dyspepsia. The epigastric pain syndrome and the postprandial distress syndrome were also assessed according to Rome III criteria.5 We also evaluated the cadets for heartburn and acid regurgitation. When these typical reflux symptoms met the following criteria of, mild symptoms occurring more than twice per week or severe symptoms occurring more than once a week, a provisional diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease was made.6

4. Assessments of eating speed

The eating speed of an individual was assessed in three ways. First, they answered "yes or no" to the question "Do you eat most of your meal very fast?" Second, the eating speed was assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS), where 10 indicated fast eating and 0 slow eating. Third, actual eating time was assessed. In this study actual eating time was assessed as follows. During survey, we provided cadets a paper to write their actual eating time for a day (Appendix 1). The investigator explained how to measure actual eating time and asked the cadet to record the actual eating time by measuring time that was spent for eating using their stopwatch or clock after finishing their each meal. A day was set to measure actual diet time (The next day after first survey). The exact recipe of the breakfast comprised of breads, soup, corn flakes and vegetable salads. The lunch comprised of a bowel of cooked rice with several side dishes (fish, noodles mixed with vegetables, pre-seasoned mixed soup and Kimchi). The supper comprised of a bowl of cooked rice with pres-seasoned mixed soup, pork and Kimchi. The cadets measured their actual diet time while eating same food items, and recorded the actual eating time for their breakfast, lunch and supper. Mean eating time of an individual was calculated by adding the actual time that was spent eating for a breakfast, lunch and supper divided by three, and was used for analysis.

5. Statistical analysis

Numeric variable with normal distribution was expressed with mean and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variable was expressed with number and percentage. Group comparisons were performed using the chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for discrete variables, as appropriate, and the t-test for continuous variables. Pearson correlation test was done to see the correlation between eating speed assessed by VAS and actual measured eating time. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Validation of the questionnaire

Twenty questions were assessed for reproducibility by the kappa score. Out of 20 questions, the kappa score was greater than 0.4 in every case, and above 0.7 for 13 questions.

2. Prevalence of functional dyspepsia

The prevalence of functional dyspepsia by Rome III criteria was 12% (11 of 89 participants). The epigastric pain syndrome and postprandial distress syndrome were present in 36% (4 of 11) and 64% (7 of 11), respectively. In addition, 7% (6 of 89) were diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease.

3. Eating speed

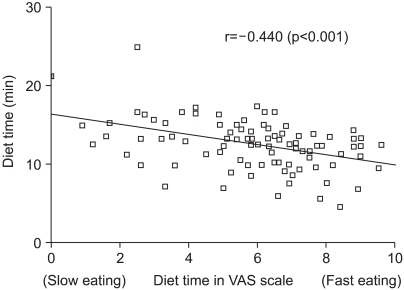

For the yes or no question, 19 (21%) replied that they ate their meals fast. The VAS of eating speed was 5.9±2.0. The self-reported actual time that was spent for eating was 12.6±3.2. There was a correlation between the eating speed measured by VAS and self-reported measured eating time (r=-0.440, p<0.001, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

There is a significant correlation between visual-analogscale (VAS) score and measured eating time (r=-0.440, p<0.001).

4. Relationship between eating speed and functional dyspepsia

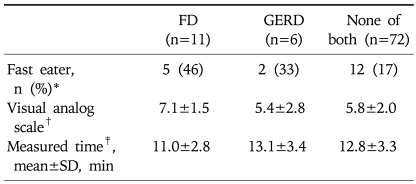

The proportion of individuals that reported that they ate their meals fast, VAS for eating speed and actual time measured for meals are shown in Table 1. Compared to individuals without FD or GERD (control), more proportion of individuals with FD regarded themselves as fast eater. VAS was also significantly higher (high VAS means fast eating) among individuals with FD compared to control. However, the difference in the actual measured time was not statistically significant between individuals with FD control.

Table 1.

Association between Eating Speed and Functional Dyspepsia

FD, functional dyspepsia; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; SD, standard deviation.

*FD vs none, p=0.043; FD vs GERD, p=1.000; GERD vs none, p=0.293; †FD vs none, p=0.045; FD vs GERD, p=0.215; GERD vs none, p=0.632; ‡FD vs none, p=0.098; FD vs GERD, p=0.198; GERD vs none, p=0.814.

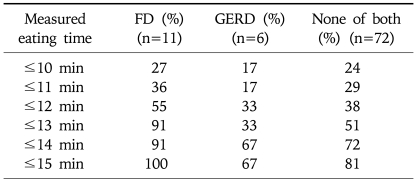

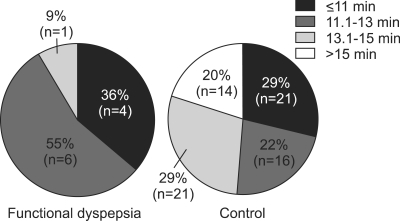

Table 2 shows cumulative proportion of individuals according to their measured eating time among patients with FD, GERD and control. Most of individuals with FD ate their meals within 13 minutes. Proportion of patients who ate their meal within 13 minutes was significantly higher in individuals with FD compared to control (91% vs 51%, p=0.020, Fig. 2) or GERD (91% vs 33%, p=0.028).

Table 2.

Cumulative Proportion of Functional Dyspepsia Patients Who Eat Faster than Their Reported Eating Time

FD, functional dyspepsia; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Fig. 2.

The proportion of individuals who eat their meal within 13 minutes is higher for functional dyspepsia patients than for the controls (91% vs 51%, p=0.020).

DISCUSSION

FD is a heterogeneous disorder, and 'diet' might play a role in numerous ways in a given individual.1 'The speed of eating' might play a role in FD, and sometime patients are often advised to eat slowly. However, there has been few data that directed looked for impact of 'diet speed' on dyspeptic symptoms. In this study, we aimed to see whether 'diet speed' has any role in FD in both subjective and objective ways. Subjective tools included a "yes or no" question and VAS for 'diet speed', and objective tool was measuring actual diet time that was spent for eating.

In subjective terms, there seems an association between eating speed and FD. A higher proportion of individuals with FD considered themselves fast eaters than control (46% vs 17%, p=0.043). The VAS score was also significantly higher in the cadets with FD than control (7.1±1.5 vs 5.8±2.0, p=0.045). In contrast to our findings, Carvalho et al.7 reported that there was no significant difference in patients with FD and controls with regard to self report of eating fast (36.6% vs 26.7%, FD vs control, respectively). Although the differences in their study were not statistically significant, a greater proportion of patients with FD considered themselves as fast eaters, too.

To our knowledge, we first directly measured actual eating time, and compared among patients with FD and control. The eating time might be influenced by the situation of the meal, amount of consumed food, appetite, type of recipe, culture and numerous other factors. Thus, comparison of eating time is meaningful if all this possible contributing factors are well controlled. Measuring actual eating time and comparing between groups were considered meaningful in this study because of special characteristics of study participants. The cadets had same type of food in similar situation. But, still, we were unable to measure possible contributing factors that might be related to eating time, such as appetites, amount of consumed food. Because the studied group of individuals were all women, within the same age group, and with a very similar body mass index, the amount of the meal would not be expected to differ very much among participants. However since we did not correct the measured eating time for amount of consumed food, the measured diet time might have been biased. Furthermore, we only measured a diet time on a single day, so it may not truly reflect a person's diet speed. Nevertheless, when VAS was tested with actual measured diet time, we found a good correlation between VAS and actual eating time, suggesting that individual who feel herself as a fast eater have actually ate fast in this study. Thus further analysis was carried out using 'measured eating time.'

Using this objective variable (measured eating time), we found that individuals with FD ate their meals about 1.8 minutes faster that control. But this was not statistically significant difference (p=0.098), and the actual difference (1.8 minutes) was small. This suggests that while patients with FD considered themselves as a fast eater, there is no difference in actual eating time. Although we did not find the statistically significant difference in measured actual eating time, considering limitations of measured actual eating time and results of subjective variables (yes/no question and VAS for eating speed), we further looked how many patients had their meal within measured eating time (Table 2, Fig. 2). Interestingly, in this analysis, we noticed that most of individuals with FD ate their meals within 13 minutes, while control were not. This difference were significant, indicating that more proportion of FD patients eat their meals within certain cut-off time (13 minutes in this study) compared to control. Taken together, results of this study suggest that there is possibility of real difference in the 'speed of eating' between FD vs control.

The interpretation of this data is limited by several factors. First, sample size of this study was small (n=89), and actual number of patients with FD was very small (n=11), which made our study statistically low-powered. Second, it is unclear whether diet speed is an etiological factor that might involve in the pathophysiology of FD. Pathophysiology of FD is believed to be multi-factorial, including disordered gastric emptying and gastroduodenal motility, accommodation of the proximal stomach, intragastric food distribution, visceral hypersensitivity, functional abnormalities in the central nervous system, and psychological factors.8-14 It is plausible that fast eating may alter gastric emptying and gastroduodenal motility or alter the accommodation of the proximal stomach. However, the association between diet speed and FD may be merely an association because of other possible etiological factor, such as psychological factors. In order to see whether 'speed of eating' is an etiological factor, studies which investigate all these possible factors along with 'speed of eating' is needed.

Despite these limitations, this study showed that 'diet speed' might be related to dyspeptic symptoms in both subjective and objective ways. Advising patients to eat slowly has no side effects. If FD patients benefit by this simple measure, it would be rational to identify fast eater among FD patients, and advise them to eat slowly. Although this study cannot provide strong scientific evidence for recommending FD patients to eat slowly, this study provide some evidence to warrant further evaluation of 'diet speed' in patients with FD.

In summary, the results of this study suggested a possible role of eating speed in functional dyspepsia. Maybe patients with FD might benefit by eating slowly. Further studies are required to address whether modulation in the eating speed have any place in the management of functional dyspepsia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The view expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Ministry of National Defense, or the Government of Korea.

APPENDIX

Appendix 1

(Original version was in Korean)

Footnotes

Financial support, None. Potential competing interests, None.

References

- 1.Feinle-Bisset C, Horowitz M. Dietary factors in functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:608–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullan A, Kavanagh P, O'Mahony P, Joy T, Gleeson F, Gibney MJ. Food and nutrient intakes and eating patterns in functional and organic dyspepsia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feinle-Bisset C, Vozzo R, Horowitz M, Talley NJ. Diet, food intake, and disturbed physiology in the pathogenesis of symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:170–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuperus P, Keeling PW, Gibney MJ. Eating patterns in functional dyspepsia: a case control study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50:520–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. quiz 1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalho RV, Lorena SL, de Souza Almeida JR, Mesquita MA. Food intolerance, diet composition, and eating patterns in functional dyspepsia patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:60–65. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0698-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jian R, Ducrot F, Piedeloup C, Mary JY, Najean Y, Bernier JJ. Measurement of gastric emptying in dyspeptic patients: effect of a new gastrokinetic agent (cisapride) Gut. 1985;26:352–358. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.4.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monnikes H, Tebbe JJ, Hildebrandt M, et al. Role of stress in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Evidence for stress-induced alterations in gastrointestinal motility and sensitivity. Dig Dis. 2001;19:201–211. doi: 10.1159/000050681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camilleri M, Malagelada JR, Kao PC, Zinsmeister AR. Gastric and autonomic responses to stress in functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:1169–1177. doi: 10.1007/BF01296514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausken T, Svebak S, Wilhelmsen I, et al. Low vagal tone and antral dysmotility in patients with functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:12–22. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanghellini V, Ghidini C, Maccarini MR, Paparo GF, Corinaldesi R, Barbara L. Fasting and postprandial gastrointestinal motility in ulcer and non-ulcer dyspepsia. Gut. 1992;33:184–190. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troncon LE, Bennett RJ, Ahluwalia NK, Thompson DG. Abnormal intragastric distribution of food during gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia patients. Gut. 1994;35:327–332. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mearin F, Cucala M, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. The origin of symptoms on the brain-gut axis in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]