Abstract

Background

Collaboration with patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) highlights that outcomes important to them include fatigue, coping and life enjoyment. However, these are not commonly measured in clinical trials. There is little evidence about which outcomes patients would prioritise, nor what factors influence patients’ prioritisation.

Objective

To develop a complementary core set with patients to promote inclusion of their priority outcomes in pharmacological interventions.

Methods

Nominal groups were conducted with RA patients to rank 63 outcomes generated from previous in-depth interviews. A multi-centre postal survey provided the final selection of core outcomes for the RAPP-PI, in which RA patients rated the importance of the priority outcomes from the nominal groups and ranked the top 6.

Results

26 patients participated in 5 nominal group discussions, and reduced the 63 initial outcomes to 32 most important. 254 participants in the survey ranked priority treatment outcomes to form the RAPP-PI: pain, activities of daily living, joint damage, mobility, life enjoyment, independence, fatigue, and valued activities. The 8 priorities represent three domains of treatment outcomes: direct impact of RA, psychosocial well-being, and function/participation. Chi-squared tests showed that disease severity, disease duration, gender and patients’ perceptions of managing, self-efficacy and normality influenced the selection of priority treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

Collaboration with patients has captured their perspective of priority outcomes from pharmacological interventions. Whilst there is some overlap with professional core outcomes, the additional use of this complementary set will give a broader evaluation of effectiveness of interventions from the key stakeholders: patients.

Background

Qualitative research with RA patients identified that there may be treatment outcomes important to patients that are frequently not being measured in clinical trials, such as fatigue, coping, returning to/ maintaining a normal life, and life enjoyment (1-5). A systematic review of the reporting of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in recent pharmacological trials of RA indicated that while function, patient global assessment and pain are commonly reported (in 83%, 61% and 56% of the 109 studies reviewed), outcomes such as fatigue, coping, and sleep disturbance are not (6). Quality of life, which may measure a range of outcomes important to patients, was measured in just 19.2% of the studies (6). Core outcomes currently measured in clinical trials included in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) core set (7) and Disease Activity Score (DAS) (8), have been carefully constructed by professionals based on both evidence and expert opinion. However, whilst these contain PROs that may be important to patients (pain, function, global health), there has been no systematic attempt to understand the patient perspective of priority outcomes. However, attempts have been made to measure activities important to patients, such as valued activities (which may or may not be essential) (9), or weighting the importance of essential activities of daily living (ADL) to assess the personal impact of disability (10).

Twenty-three outcomes identified in patient focus groups (2) were rated for importance by patients in a multi-centre study (11). ‘Staying independent’, ‘reducing pain’, and ‘keeping mobile’ were the most frequently selected in the top 3 (by 39%, 36% and 34% respectively) and are already in the ACR core set. However, ‘returning to/ maintaining a normal lifestyle’, ‘feeling well in myself’ and ‘enjoying my life’ were also commonly selected (by 26%, 20% and 18% respectively), but are not in the ACR core set or DAS. A patient-derived composite response index is being developed by a EULAR initiative: the RA Impact of Disease (RAID) index (12). Seven domains identified by professionals in a literature search, and reviewed by a patient panel were weighted by patients from 10 European countries: pain (21%), functional disability (16%), fatigue (15%), emotional well-being (12%), sleep (12%), coping (12%), and physical well-being (12%) (12). These studies suggest patient priorities only partly overlap with those included in core sets developed by health professionals.

It has also been shown that anti-TNF therapy changes outcome priorities for RA patients. After 12 months of treatment, there were significant decreases in the selection of pain (baseline: 88.4%, follow-up 71.1%) and hand and finger function (57.2%, 43.4%), but increases in the selection of household tasks (16.2%, 24.3%) (13). Hewlett et al. showed that gender influenced the prioritisation of outcomes, with women selecting fatigue more frequently than men (16.8% vs 7.8% P=0.05); and men selecting work role (19.5% vs 10.3% P=0.04) and side effects (18.2% vs 4.8% p<0.0001) more frequently than women (11). The RAID study found that patients rated their domains independently of their demographic characteristics (gender, age and disease duration), but this may be a result of how the variables were dichotomised for analysis (12). However, countries with a lower gross domestic product rated the physical group of domains (pain, functional disability, physical well-being and sleep disturbance) more highly. Overall, there is minimal research on the factors influencing treatment outcome prioritisation in RA.

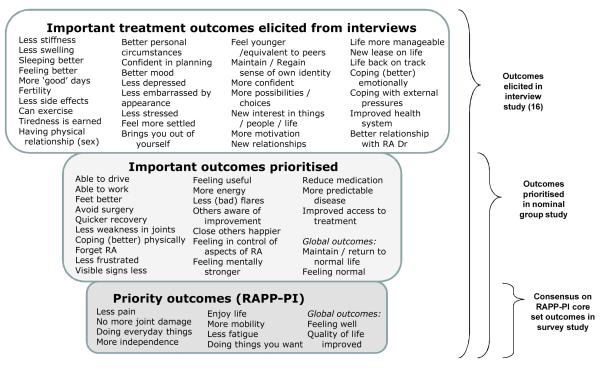

There are several issues in capturing the patient perspective that have not been addressed in the above studies. First, most studies to identify important outcomes were based on prioritisation of outcomes from standard scales, or before the widespread use of current treatment paradigms. Second, the meaning of well-being and normality has not been clarified. Third, patients’ experiences may change their expectations and judgements of what is important as a result not only of treatment efficacy, but also of response shift or adaptation, which has not been accounted for in these studies (14). Fourth, the interpretation and analysis of individualised instruments of patients’ treatment priorities remains problematic in large clinical trials (15). Therefore, it may be important to aim for the standardisation of patients’ priority outcomes whilst still incorporating their personal importance, patients’ ability to manage them, and adaptation. The objective of the current work was to develop a patient consensus on a core set of drug treatment outcome priorities, incorporating the meaning of complex outcomes such as well-being and normality, and to determine the factors associated with the prioritisation of specific outcomes. Previously, in-depth interviews were conducted by the authors with 23 RA patients on a range of medication types to elicit patient priority treatment outcomes (16). Sixty-three outcomes important to patients were identified, providing a sound foundation on which to develop a complementary patient core set (Figure 1). This paper reports the second and third studies in the construction of the patient core set.

Figure 1.

Prioritisation of treatment outcomes from interviews, nominal groups and survey

Methods

Ethics approval was granted by Brighton East Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (ref. 07/H1107/138) for the studies, and written consent taken before participation. A patient research partner (P.R.) was part of the steering committee.

Nominal groups study: Patient prioritisation of important treatment outcomes

Nominal groups (17) were used with patients (experts with valuable knowledge of living with RA) to rate the importance of and prioritise the 63 outcomes previously generated in the interview study (16). Patients with RA (18) attending outpatient appointments were identified from clinical notes. Participants were purposively sampled for a range of medications, disease duration, disease activity (DAS patient opinion (general health) Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (Considering all the ways your arthritis affects you, how well are you doing?) (8), gender, age and work status. Five nominal groups were held, with three rounds:

Round 1: Patients were asked to individually rate the 63 outcomes using four categories of importance: not important/not applicable, important, very important, most important. Only the most important outcomes were used in Round 2.

Round 2: After sharing their most important outcomes, debate and discussion followed amongst these expert groups. A consensus was formed on the most important outcomes to be represented in a core set of measures for drug intervention and a single group list was created.

Round 3: Patients were asked to individually rank the top 5 outcomes from the group list for personal importance.

The discussions were transcribed verbatim and the qualitative data are reported in full elsewhere (publication forthcoming).

Analyses, nominal groups

The priority scores were calculated from the outcomes prioritised by patients in their top 5 (Round 3), (1st = 5 points, 2nd = 4 points etc) and summed across all 5 groups. Data are presented as a percentage of the maximum possible priority score (number of participants × 5 points).

Survey study: Final selection of priority treatment outcomes for the RAPP-PI core set

A representative sample of people with RA was recruited for a postal survey through four centres in the UK. Three diverse outpatient rheumatology departments included patients empowered to order their own patient reviews (Site 1), patients on anti-TNF therapy database (Site 2), and those attending a psychological support service (Site 3). The fourth site was a patient charity, the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS), and a random sample was selected from the membership database. 1.4% of patients from Site 1, 61.3% from Site 3 and 25.9% from Site 4 were also receiving anti-TNF therapy. The survey questionnaire was laid out in seven sections:

Clinical status

DAS patient opinion VAS, five Numerical Rating Scales (NRS) to assess different components of well-being (global, physical, emotional, managing, and external stresses) (19), pain intensity NRS (20), fatigue intensity NRS (21), and satisfaction with social support NRS (constructed with P.R.) (all last seven days, 0-10).

Socio-demographic

Age, gender, educational achievement, work status, and ethnicity.

Outcomes

Scoring outcome importance and ranking the 32 treatment outcomes from the nominal group study was in four stages. First, outcomes (excluding the global ones) were individually scored for importance on a 5-point Likert scale. Second, patients selected six outcomes as being “most important”. Third, patients ranked their six selected outcomes in order of importance. Fourth, the global outcomes (improved quality of life, feeling well, feeling normal, and return to/maintain a normal life) were individually scored for importance on a 5-point Likert scale. Two different orderings of the outcomes were used to assess whether this affected the importance scoring.

Beliefs

Rheumatoid Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (RASE, 28-140, high good) (22)

Normality

A 7-item scale on perceptions of normality in RA was drafted from the interview data (16). A 5-point Likert scale was used (Appendix 1, Supplemental Table).

Medication

Disease duration, prescribed medications, medication satisfaction, and co-morbidities.

Disability

Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ, 0-3, high bad) (23)

Six patient research partners provided feedback on the survey and it was piloted with seven patients attending clinic. Consent forms were returned by participants with the completed survey. A second survey was posted to non-responders in Sites 2 and 3, which had lower initial response rates than Sites 1 and 4.

Analyses, survey study

Rating importance

The percentage of participants rating an outcome as very important was calculated (selecting category 5, from range 1-5).

Relative importance

The percentage selecting an outcome in their top 6 priorities was calculated. The priority scores (1st - 6th) were then summed from the top 6 ranked outcomes for all participants and data presented as a percentage of the maximum possible priority score, to create the draft RAPP-PI.

Factors

Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was used to determine the internal reliability of the outcomes overall (24). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) using a Direct Oblimin rotation on the importance scores (1-5) was used to explore the data for factors or groupings of outcomes that tended to be rated in similar ways (24). PCA was also used to indicate the multidimensionality of the final RAPP-PI core set. Chi-squared tests were applied to determine the association between the prioritisation of outcomes (1=selected, 0=not selected) and gender, disease duration (≤5 years / >5 years), patient’s perception of managing their RA (0-4 not managing, 5-7 moderately well, 8-10 well), self-efficacy (28-65 low, 66-103 moderate, 104-140 high), perceptions of normality (7-16 low, 17-26 moderate, 27-35 high) and disease severity (0-4 mild, 5-7 moderate, 8-10 severe for pain and fatigue, 0-1 low, 1.125-2 moderate, 2.125 – 3 high for HAQ scores).

Results

Nominal group study: Patient prioritisation of important treatment outcomes

Five nominal groups with 26 RA patients were conducted (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics for nominal group and survey participants

| Variable | Nominal groups (N=26) |

Survey (N=254) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | Female | 21 | 80.8 | 192 | 75.6 |

| Male | 5 | 19.2 | 62 | 24.4 | |

| Age | Under 40 | 2 | 7.7 | 11 | 4.3 |

| 40-59 | 8 | 30.7 | 89 | 35.0 | |

| 60-69 | 12 | 46.2 | 80 | 31.5 | |

| 70+ | 4 | 15.4 | 74 | 29.1 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 26 | 100.0 | 249 | 98.0 |

| Asian / British Asian | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Black / British Black | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Mixed ethnicity | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.8 | |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Work status | Working | 5 | 19.2 | 64 | 25.5 |

| Not working | 21 | 80.8 | 190 | 74.5 | |

| Medication | Biologics | 13 | 50.0 | 100 | 39.4 |

| DMARDs | 13 | 50.0 | 131 | 51.6 | |

| Oral steroids only* | 10 | 3.9 | |||

| Not taking medication | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 5.1 | |

| Disease duration | 0 < 5 yrs | 4 | 15.4 | 62 | 24.4 |

| ≥5<10 yrs | 5 | 19.2 | 66 | 26.0 | |

| ≥10<20yrs | 10 | 38.5 | 60 | 23.6 | |

| > 20 yrs | 7 | 26.9 | 66 | 26.0 | |

| DAS patient opinion VAS |

0≤4 (mild disease activity) | 11 | 42.3 | 128 | 50.4 |

| >4≤7 | 8 | 30.8 | 95 | 37.4 | |

| >7≤10 (flare) | 7 | 26.9 | 31 | 12.2 | |

| HAQ* | 0-1.000 (mild disability) | 64 | 25.2 | ||

| 1.125-2 | 105 | 41.3 | |||

| 2.125-3 (severe) | 85 | 33.5 | |||

Collected in Study 3 only

Round 1

Overall, groups selected a mean of 14 outcomes (out of 63) as “Not important/not applicable” (range of outcomes selected individually 0-48), 24 as “Important” (7-40), 11 as “Very important” (3-34), and 14 as “Most important” (5-32). In the “Not important/not applicable” category, 84.6% selected ‘Fertility’, 53.8% ‘New relationships/socialise more’, and 50% ‘Less embarrassed by visible signs’. One new outcome “Weakness in wrists” was added by Group 4.

Round 2

38 different outcomes were selected for prioritisation as being important across all 5 group lists, with a mean of 10 outcomes prioritised by each group.

Round 3

Across all groups, 32 outcomes (Figure 1) were selected by at least one individual in their top 5 most important outcomes, indicating the diversity of priorities across the RA population. The top 5 outcomes prioritised overall by the nominal groups were ‘Less pain’ (43.8% of possible maximum priority score for outcome), ‘No more joint damage’ (40.8%), ‘Less fatigue’ (16.2%), ‘Able to do everyday things’ (14.6%), and ‘More mobility’ (13.1%). Of the global outcomes, ‘Improved quality of life’ was ranked highest (23.1%), compared to ‘Return to/ maintain normal life’ (20.8%), ‘Feel well’ (20.0%) and ‘Feeling normal’ (10.0%).

All 32 outcomes selected in the top 5 in Round 3 were taken forward to the survey study, with the exception of ‘Improved access to treatment’ which, in discussion with the patient research partner (P.R.), was felt to be a specific outcome of receiving anti-TNF therapy in the UK. It was decided that the four global outcomes would be listed separately from the more specific 27 outcomes in the final selection of priority outcomes in the survey study.

Survey study: Selection of priority treatment outcomes for the RAPP-PI core set

254 participants completed the postal surveys (Site 1: n=68; 2: 58; 3: 43; 4: 85) and were representative overall of an RA population (Table 1). The percentage of participants rating an outcome as very important is shown in Table 2 (Column 1). The percentage selecting them in their top 6 showed greater differentiation with just 12 outcomes being chosen by >20% of participants (Column 2). Calculating the percentage of maximum possible priority score identified the top 6 prioritised as: ‘Less pain’ (42.0%), ‘Doing everyday things’ (28.5%), ‘No more (visible) joint damage’ (28.5%), ‘More mobility’ (24.4%), ‘Enjoy life’ (24.2%), and ‘More independent’ (22.5%) (Column 3). However, it was decided to explore the data further before making a final selection for the RAPP-PI.

Table 2.

Ranking of treatment outcomes by survey participants

| Treatment outcomes (RAPP-PI outcomes in bold) |

% choosing outcome as very important |

% choosing outcome in Top 6 (priority) |

% maximum priority score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less pain | 77.6 | 43.7 | 42.0 |

| Doing everyday things | 77.6 | 39.4 | 28.5 |

| No more joint damage | 82.3 | 39.8 | 28.5 |

| More mobility | 79.5 | 33.1 | 24.4 |

| Enjoy life | 73.6 | 32.3 | 24.2 |

| More independence (physical) | 79.5 | 30.3 | 22.5 |

| Less fatigue | 68.1 | 31.1 | 21.9 |

| Do things you want to do | 68.9 | 27.2 | 18.1 |

| Able to drive | 60.6 | 31.9 | 20.2 |

| Avoid surgery | 61.4 | 25.2 | 14.9 |

| Less (bad) flares | 72.8 | 20.9 | 13.6 |

| Less weakness | 75.6 | 20.5 | 13.0 |

| Feet better | 63.4 | 15.0 | 10.3 |

| Cope (better) physically | 68.9 | 15.0 | 10.2 |

| Reducing medication | 39.8 | 15.4 | 8.6 |

| Able to work | 26.4 | 11.0 | 6.5 |

| More energy | 68.9 | 13.0 | 6.4 |

| Less frustrated | 57.5 | 9.8 | 5.1 |

| Feel useful | 54.7 | 9.1 | 4.6 |

| Mentally stronger e.g. empowered | 60.9 | 9.4 | 4.6 |

| Close others happier | 49.6 | 7.1 | 4.3 |

| Forget about RA / Focus not on RA | 52.8 | 5.1 | 3.2 |

| Feeling in control of aspects of RA | 58.3 | 5.5 | 3.0 |

| Visible signs less | 37.0 | 6.3 | 2.3 |

| More predictable disease | 46.1 | 3.5 | 1.8 |

| Quicker recovery | 38.6 | 5.1 | 1.7 |

| Others aware of improvement | 22.8 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| Global outcomes: | |||

| Quality of life improved | 81.1 | - | - |

| Feeling well | 79.5 | - | - |

| Maintain / return to normal life | 74.0 | - | - |

| Feeling (more) normal | 66.9 | - | - |

The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was 0.91 for all 31 treatment outcomes, which is high. ‘Able to work’ and ‘Able to drive’ were identified as increasing the coefficient to 0.92 and therefore increasing reliability if they were deleted. There was a significant association between age and the importance scores of both ‘Able to work’ (X2=74.49, p<0.001) and ‘Able to drive’ (X2=34.61, p<0.001), where the importance of both outcomes declined with age, although less strongly for driving. There was no significant association between disease duration and the importance of ‘Able to work’ (X2=5.60, P=0.23) or ‘Able to drive’ (X2=2.43, P=0.66). Since the association was with age, rather than related to the condition, it was decided to exclude these two outcomes from the final selection of outcomes and the PCA (29 items).

PCA on the importance scores generated five components, explaining 55.68% of the variance overall (Table 3). Within the functional outcomes, PCA indicated that ‘More mobility’ and ‘More independence’ would capture different data from ‘Doing everyday things’ and ‘Doing things you want’ since they loaded on different components. After review with the steering committee (including P.R.), the components were labelled Direct impact of RA (Component 1: accounting for 34.97% of the variance), Overall wellness (2: 6.35% additional variance), Assessment/Intrusion of RA (3: 5.52%), Psychosocial well-being (4: 4.75%), and Function/Participation (5: 4.10%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

PCA of importance scores for treatment outcomes and associated percentage of variance

| Treatment outcomes | Components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct impact of RA |

Overall wellness |

Assessment/ Intrusion of RA |

Psycho- social well- being |

Function/ Partici- pation |

|

| Less flares | .721 | ||||

| More mobility | .684 | ||||

| Less weakness | .651 | ||||

| Less pain | .616 | ||||

| Better feet | .585 | ||||

| More/maintain independence | .551 | ||||

| More energy | .531 | ||||

| Less fatigue | .511 | ||||

| Less frustrated | .455 | .329 | |||

| More predictable disease | .437 | .422 | |||

| Control aspects of RA | .408 | .363 | |||

| Mentally stronger | .396 | .362 | |||

| Feel normal | .784 | ||||

| Return to/maintain normal life | .778 | ||||

| Feel well | .748 | .325 | |||

| Improve quality of life | .695 | .328 | |||

| Others aware of improvement | .684 | .366 | |||

| Reduce medication | .639 | .320 | |||

| Quicker recovery | .616 | ||||

| Visible signs less | .517 | ||||

| Close others happier | .756 | ||||

| Focus not on RA | .661 | ||||

| Enjoy life | .593 | ||||

| Feel useful | .518 | ||||

| Coping (physically) | .493 | ||||

| Able to do everyday things | .637 | ||||

| Do things you want to do | .342 | .562 | |||

| No more joint damage | .465 | .510 | |||

| Avoid surgery | .366 | .506 | |||

|

| |||||

| Eigenvalues | 10.14 | 1.84 | 1.60 | 1.38 | 1.19 |

| % Variance | 34.97 | 6.35 | 5.52 | 4.75 | 4.10 |

| % Cumulative variance | 34.97 | 41.31 | 46.84 | 51.58 | 55.68 |

Chi-squared tests showed that the prioritisation of treatment outcomes varied according to variables of gender, disease duration, perceptions of managing, self-efficacy, perceptions of normality, and disease severity (Table 4). Men more frequently selected ‘Able to drive’ (X2=7.73, p=0.009), and women more frequently selected ‘Less fatigue’ as a priority (X2=4.83, p=0.028). Those diagnosed >5 years were significantly more likely to prioritise ‘Mentally stronger’ (X2=5.53, p=0.34) than those diagnosed ≤5 years. Those managing well, with high self-efficacy, or greater perceptions of normality were more likely to prioritise ‘Enjoy life’ and/or ‘Doing things you want’. In contrast, those who were not managing, with lower self-efficacy or lower sense of normality were more likely to prioritise symptoms and impairment, including ‘More mobility’, ‘Less pain’ and ‘Less fatigue. Greater pain, fatigue and disability were associated with the prioritisation of those symptoms and also impairment-related outcomes, such as function and visible deformity. In contrast, ‘Enjoy life’ and ‘Doing things you want’ were more likely to be selected as a priority by those with less disease severity.

Table 4.

Factors influencing prioritisation of treatment outcomes

| Variable | Patient outcome | X2 | P-value | % participants selecting outcome as priority (1st-6th) in survey |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Able to drive | 7.73 | 0.009 | Female | 29.2 |

| Male | 48.4 | ||||

| Less fatigue | 4.83 | 0.028 | Female | 39.6 | |

| Male | 24.2 | ||||

| Disease duration | Mentally stronger | 5.53 | 0.034 | ≤ 5 yrs | 4.1 |

| >5 yrs | 14.6 | ||||

| Managing RA (NRS) |

Coping better (physically) |

12.33 | 0.004 | Not managing | 24.1 |

| Managing moderately | 23.5 | ||||

| Managing well | 6.1 | ||||

| Fatigue | 9.96 | 0.023 | Not managing | 48.1 | |

| Managing moderately | 41.2 | ||||

| Managing well | 22.0 | ||||

| More mobility | 9.12 | 0.009 | Not managing | 50.0 | |

| Managing moderately | 42.4 | ||||

| Managing well | 25.6 | ||||

| Enjoy life | 7.87 | 0.009 | Not managing | 31.5 | |

| Managing moderately | 28.2 | ||||

| Managing well | 50.0 | ||||

| Do things you want | 7.16 | 0.036 | Not managing | 27.8 | |

| Managing moderately | 23.5 | ||||

| Managing well | 41.5 | ||||

| Reduce medication | 7.06 | 0.023 | Not managing | 18.5 | |

| Managing moderately | 9.4 | ||||

| Managing well | 25.6 | ||||

| Self-efficacy (RASE questionnaire) |

Mentally stronger | 15.40 | 0.000 | Self-efficacy: Low | 66.7 |

| Moderate | 5.0 | ||||

| High | 13.0 | ||||

| Enjoy life | 11.16 | 0.004 | Self-efficacy: Low | 66.7 | |

| Moderate | 27.7 | ||||

| High | 47.3 | ||||

| Coping better (physically) |

7.55 | 0.023 | Self-efficacy: Low | 66.7 | |

| Moderate | 21.8 | ||||

| High | 13.7 | ||||

| Perceptions of normality (Normality scale) |

Less pain | 21.79 | 0.000 | Normality: Low | 77.6 |

| Moderate | 50.0 | ||||

| High | 38.3 | ||||

| Less fatigue | 14.22 | 0.001 | Normality: Low | 47.8 | |

| Moderate | 38.9 | ||||

| High | 16.7 | ||||

| Enjoy life | 13.28 | 0.001 | Normality: Low | 25.4 | |

| Moderate | 37.3 | ||||

| High | 56.7 | ||||

| Do things you want | 6.06 | 0.048 | Normality: Low | 19.4 | |

| Moderate | 33.3 | ||||

| High | 38.3 | ||||

| Pain intensity (NRS) |

Cope better | 13.64 | 0.001 | Pain: Mild | 10.9 |

| Moderate | 54.3 | ||||

| Severe | 34.8 | ||||

| Enjoy life | 12.21 | 0.002 | Pain: Mild | 52.9 | |

| Moderate | 28.4 | ||||

| Severe | 35.4 | ||||

| Less pain | 10.71 | 0.005 | Pain: Mild | 42.5 | |

| Moderate | 54.9 | ||||

| Severe | 69.2 | ||||

| Fatigue intensity (NRS) |

Less fatigue | 24.86 | 0.000 | Fatigue: Mild | 12.7 |

| Moderate | 34.9 | ||||

| Severe | 55.7 | ||||

| Quicker recovery | 9.13 | 0.010 | Fatigue: Mild | 5.5 | |

| Moderate | 1.6 | ||||

| Severe | 11.4 | ||||

| Less pain | 7.46 | 0.024 | Fatigue: Mild | 43.6 | |

| Moderate | 51.9 | ||||

| Severe | 67.1 | ||||

| Enjoy life | 6.49 | 0.039 | Fatigue: Mild | 50.9 | |

| Moderate | 38.8 | ||||

| Severe | 28.6 | ||||

| Physical disability (HAQ) |

More mobility | 24.80 | 0.000 | Disability: Mild | 17.2 |

| Moderate | 41.0 | ||||

| Severe | 57.6 | ||||

| Able to work | 17.28 | 0.000 | Disability: Mild | 25.0 | |

| Moderate | 9.5 | ||||

| Severe | 3.5 | ||||

| Everyday activities | 11.74 | 0.003 | Disability: Mild | 57.8 | |

| Moderate | 51.4 | ||||

| Severe | 31.8 | ||||

| Enjoy life | 7.67 | 0.022 | Disability: Mild | 53.1 | |

| Moderate | 34.3 | ||||

| Severe | 32.9 | ||||

| Do things you want | 6.98 | 0.030 | Disability: Mild | 37.5 | |

| Moderate | 35.2 | ||||

| Severe | 20.0 | ||||

| Visible signs | 6.02 | 0.049 | Disability: Mild | 12.5 | |

| Moderate | 6.7 | ||||

| Severe | 2.4 |

The final selection of priority outcomes for the RAPP-PI are based on the priority scores (Table 2), with the exclusion of ‘Able to drive’ on the basis of the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients and its association with age rather than disease. The steering committee (including P.R.) decided on the basis of the feasibility of a core set, to include only the top 8 treatment outcomes prioritised by patients. Therefore the RAPP-PI outcomes are: ‘Less pain’, ‘Doing everyday things’, ‘No more joint damage’, ‘More mobility’, ‘Enjoy life’, ‘More independent’, ‘Less fatigue’, and ‘Doing things you want’ (highlighted in Table 2). Figure 1 shows the process of how the outcomes were generated and prioritised through three studies: previous interviews (16), nominal groups, and survey.

Discussion

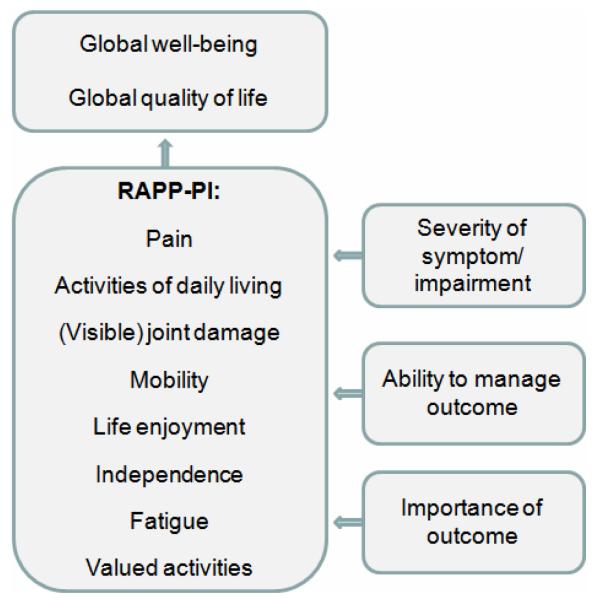

In this article, a complementary core set of priority patient-derived outcomes is proposed: the Rheumatoid Arthritis Patient Priorities – Pharmacological Interventions (RAPP-PI). This has been rigorously developed through mixed methods, grounded in patient collaboration. Overall, eight specific outcomes were prioritised by patients as essential in measuring the patient perspective of the impact of RA in relation to drug interventions: pain, ADL, joint damage, mobility, life enjoyment, independence, fatigue, and valued activities. These patient-selected outcomes are in line with the published literature on RA patient priorities (1-5, 9, 25). It is proposed that each of the RAPP-PI outcomes is measured for 1) severity, 2) the patient’s perceived ability to manage the outcome, and 3) the personal importance of the outcome (Figure 2), based on the qualitative interview (16) and nominal group data, and the chi-squared analyses on the survey data. The outcomes ‘Feeling well’ and ‘Improved quality of life’ should be measured in addition, as global measures of the impact of RA on the patient, since they were rated as very important by >75% of participants (Table 2). The patient research partner suggested that ability to work and drive should be included within the instrument to measure everyday activities in order to increase face validity.

Figure 2.

The patient-generated RAPP-PI core set

There are overlaps between the patient-derived RAPP-PI and the professionally developed ACR core set (7), which includes pain and function. However, the RAPP-PI proposes that function should separately measure ADL, mobility (getting from place to place), independence, and valued activities, based on the survey analysis. The majority of trials on RA did not measure fatigue between 2005 and 2007 (6), but following patient delegate participation and subsequent research, OMERACT has now recommended fatigue is measured alongside the ACR core set (26). Patients have prioritised life enjoyment and joint damage as priority outcomes to measure, neither of which are in the professional core sets. The patient global assessment of disease activity variable in the ACR core set may capture some aspects of these 8 outcomes, depending on the instrument used, but this has not yet been tested. Therefore, using both the HAQ (23) to measure the patient’s assessment of function and the AIMS (27) to measure the broader impact of RA in clinical trials may be preferable, until a specific RAPP-PI measure is constructed.

The DAS28 algorithm includes a patient opinion VAS (worded as either disease activity or general health) (8, 28). This may globally capture aspects of the priority outcomes selected by patients in this study, but may not be an adequate substitute for measuring each of the RAPPI-PI outcomes separately and this requires testing. The 8 RAPP-PI priority outcomes mostly overlap with the ICF components: body functions (pain, fatigue), body structures (joint damage), and activities and participation (activities of daily living, mobility, independence, valued activities) (29). However, the priority outcome ‘Enjoy life’ does not, nor the global outcomes ‘Improved quality of life’, ‘Feel well’, ‘Feel normal’ and ‘Return to/ maintain a normal life’ or other indicators of adaptation or self-management. Coenen et al. (30) reported that aspects of coping and disease management could not be linked to ICF categories. These could be allotted to the ICF component Personal Factors, but this has yet to be classified.

In the RAID study (12), Hewlett et al.’s survey (11) and in these data, pain was selected by patients in the top 2 outcomes, and functional outcomes and fatigue are in the top 8 of outcomes across the three studies. The finding that improvements in pain and aspects of physical function are of the highest importance to patients with RA is consistent with previous rheumatology studies (31-33). Sleep is a RAID domain that is not represented in the RAPP-PI. ‘Better sleep’ was an outcome elicited during the interview study (17), but was not prioritised by patients in the nominal group study. It is possible that the RAID domain of ‘physical well-being’ will simply duplicate the measurement of the pain, functional disability, fatigue and sleep domains, unless there is a systemic unwellness that is otherwise not assessed.

To facilitate the standardisation of outcomes important to patients that are assessed in clinical trials, the RAPP-PI was limited to eight outcomes. However, this results in the loss of assessment of individual variation in prioritisation as shown in Table 4. Further research is required to determine whether this variability could lead to profiling of patient subgroups, which may enhance clinical care. In order to be used, the RAPP-PI must be measurable in a way that captures the patients’ understanding of each outcome. More research is required to determine which validated scales exist to measure the priority outcomes in the RAPP-PI, and to develop new scales where required. The aim is to specify the outcome measures to be used for RAPP-PI, avoiding the current variety of PROMs in use (6). These scales may provide important additional patient-reported data in clinical decisions, for example in addition to the DAS for deciding eligibility for biologic therapies (34). The RAPP-PI outcomes were prioritised on the basis of pharmacological interventions. For non-pharmacological interventions other outcomes generated in the interview study, but not prioritised in the nominal groups or survey, may become priorities and should be considered (16).

This study has strengths and weaknesses. Due to the large numbers of outcomes being selected as very important by patients, it was not possible to rank all outcomes and only the top 5 (nominal group study) or top 6 (survey study) were ranked. This limited statistical analysis to chi-squared tests on binary data (selected/ not selected as a priority). However, patient partners involved in the research design emphasised that it would be difficult to rank more outcomes than this. Despite efforts to recruit participants from other ethnic groups, the participants were almost exclusively caucasian. Further research is planned to address this. Overall, the rigorous methodology ensured that the final RAPP-PI core set is both grounded in individual patient experiences (individual interviews) (16) and is generalisable to the UK caucasian RA population (survey study). The debate about the best methodology for developing core sets of measures for rheumatological conditions, incorporating both the patient and professional perspective is an on-going process in OMERACT (35). This study presents a mixed method approach that has been used to elicit important outcomes, establish the meaning of outcomes used by patients, and determine which outcomes are prioritised by a representative sample.

Conclusion

This study has developed a patient generated Rheumatoid Arthritis Patient Priorities for Pharmacological Interventions (RAPP-PI) core set to complement the existing professional core sets. It will facilitate the standardisation of PROs most important to patients, to be used in RA trials. The data presented in this paper may explain the known difference in patient and professional perspectives of RA outcomes, illustrating the potential patient mismatch between perceptions of disability and actual disability, and also of patient discrepancy between perceived change and actual change in outcomes. Further research is required to determine appropriate scales for these priority outcomes and to develop a RAPP-PI composite score. This study provides a methodological example of how to collaborate with patients in the development of a patient-derived core set.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who took part, staff at the different hospitals and National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society who helped with recruitment, the Arthritis Research Campaign for funding the PhD studentship, and the Medical/ Economic and Social Research Councils for funding the post-doctoral fellowship that provided time for dissemination.

Footnotes

PhD studentship from Arthritis Research Campaign (ARC).

Interdisciplinary post-doctoral fellowship from Medical / Economic and Social Research Councils (MRC / ESRC).

References

- 1.McPherson KM, Brander P, Taylor WJ, McNaughton HK. Living with arthritis -- what is important? Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(16):706–21. doi: 10.1080/09638280110049919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr A, Hewlett S, Hughes R, Mitchell H, Ryan S, Carr M, et al. Rheumatology outcomes: The patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(4):880–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahlmen M, Nordenskiold U, Archenholtz B, Thyberg I, Ronnqvist R, Linden L, et al. Rheumatology outcomes: The patient’s perspective. A multicentre focus group interview study of Swedish rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology. 2005;44(1):105–10. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall NJ, Wilson G, Lapworth K, Kay LJ. Patients’ perceptions of treatment with anti-TNF therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Rheumatology. 2004;43:1034–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards J. An exploration of patients experiences of anti-TNF therapy. Musculoskeletal Care. 2004;2(1):40–50. doi: 10.1002/msc.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalyoncu U, Dougados M, Daures J, Gossec L. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in recent tirals in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:183–90. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B, et al. The amercian college of rheumatology preliminary cores set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(6):729–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Heijde D, Hof M, Piet L, Putte L. Development of a disease activity score based on judgement in clinical practice by rheumatologists. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(3):579–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz PP, Morris A, Yelin EH. Prevalence and predictors of disability in valued life activities among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(6):763–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewlett S, Smith AP, Kirwan JR. Measuring the meaning of disability in rheumatoid arthritis: The personal impact health assessment questionnaire (PI HAQ) Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(11):986–93. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.11.986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewlett S, Carr M, Ryan S, Kirwan J, Richards P, Carr A, et al. Outcomes generated by patients with rheumatoid arthritis: How important are they? Musculoskeletal Care. 2005;3(3):131–42. doi: 10.1002/msc.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gossec L, Dougados M, Rincheval N, Balanescu A, Boumpas DT, Canadelo S, et al. The elaboration of the preliminary rheumatoid arthritis impact of disease (RAID) score: A EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(11):1680–85. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.100271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ten Klooster PM, Veehof MM, Taal E, van Riel PLCM, van de Laar MAFJ. Changes in priorities for improvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis during 1 year of anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007;66:1485–90. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.069765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr A, Gibson B, Robinson P. Is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ. 2001;322:1240–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr A, Higginson I. Are quality of life measures patient centred? BM J. 2001;322:1357–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S. What outcomes from pharmacological treatments are important to people with rheumatoid arthritis? Creating the basis of a patient core set. Arthrit Care Res. doi: 10.1002/acr.20034. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones J, Hunter D. Qualitative research: Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S. Measuring well-being in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): The development of five well-being numerical rating scales (NRS) Rheumatology. 2009;48(Suppl. 1):i156. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yazici Y, Bergman M, Pincus T. Time to score quantitative rheumatoid arthritis measures: 28-joint count, disease activity score, health assessment questionnaire (HAQ), multidimensional HAQ (MHAQ), and routine assessment of patient index data (RAPID) scores. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(4):603–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicklin J, Cramp F, Kirwan J, Hewlett S. Standardising visual analogue scales to measure fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2008;47(Suppl. 1):ii154. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewlett S, Cockshott Z, Kirwan J, Barrett J, Stamp J, Haslock I. Development and validation of a self-efficacy scale for use in british patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RASE) Rheumatology. 2001;40(11):1221–30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.11.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(2):137–45. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabachnick LS, Fidell BG. Using multivariate statistics. Harper Collins; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamm T, Wright J, Machold K. Occupational balance of women with rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2004;2(2):101–12. doi: 10.1002/msc.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirwan J, Minnock P, Adebajo A, Bresnihan B, Choy E, de Wit M, et al. Patient perspective: Fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):1174–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meenan RF, Gertman PM, Mason JH. Measuring health status in arthritis: The arthritis impact measurement scales. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:146–52. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.How to use the DAS28. [homepage on the Internet] [Accessed 10/02/09]. Available from: http://www.das-score.nl/www.das-score.nl/index.html.

- 29.Stucki G, Cieza A, Geyh S, Battistella L, Lloyd J, Symmons D, et al. ICF core sets for rheumatoid arthritis. J Rehabil Med. 2004;44(Suppl):87–93. doi: 10.1080/16501960410015470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coenen M, Stamm T, Cieza A, Amann E, Kollerits B, Stucki G. Validation of the comprehensive ICF core set for rheumatoid arthritis from the patients’ perspective using focus groups. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(4):R84. doi: 10.1186/ar1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Archenholtz B, Bjelle A. Reliability, validity and sensitivity of a Swedish version of the revised and expanded arthritis impact measurement scales (AIMS2) J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1370–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwoh CK, Ibrahim S. Rheumatology patient and physician concordance with respect to important health and symptom status outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:372–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4<372::AID-ART350>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heiberg T, Kvien TK. Preferences for improved health examined in 1,024 patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Pain has highest priority. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47(4):391–7. doi: 10.1002/art.10515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NICE . Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid. NICE; London: 2007. Report No.: Technology appraisal guidance no. 130. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tugwell P, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon L, Strand V, Idzerda L. OMERACT: An international initiative to improve outcome measurement in rheumatology. Trials. 2007;8(38) doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.