Abstract

Bacterial polysulfide reductase (PsrABC) is an integral membrane protein complex responsible for quinone coupled reduction of polysulfide, a process important in extreme environments such as deep-sea vents and hot springs. We determined the structure of polysulfide reductase from Thermus thermophilus at 2.4 Å resolution, revealing how the PsrA subunit recognizes and reduces its unique poly anionic substrate. The integral membrane subunit PsrC was characterized using the natural substrate menaquinone-7 and inhibitors, providing a comprehensive representation of a quinone binding site and revealing the presence of a water filled cavity connecting the quinone binding site on the periplasmic side to the cytoplasm. These results suggest that polysulfide reductase could be a key energy-conserving enzyme of the T. thermophilus respiratory chain, utilizing polysulfide as the terminal electron acceptor and pumping protons across the membrane via a previously unknown mechanism.

Thermus thermophilus is an obligate aerobe that resides in geothermal hot springs and has received considerable attention due to its biotechnological potential1. The energy coupling enzymes of this organism have been characterized, and several characteristic components of an aerobic electron transfer chain have been identified; a proton-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase composed of 15 subunits with menaquinone-7 (MK-7) as the endogenous electron acceptor2,3, a soluble cytochrome c552 (ref. 4), a bc1 complex5, and two terminal enzymes: a ba3- and a caa3-type heme-copper oxidase6,7. The former is a high-affinity oxidase expressed during low oxygen tension8,9, while the latter is observed during normal oxygen levels10. Interestingly, in addition to these enzymes, sequencing of the T. thermophilus (HB27) genome revealed the presence of a gene cluster encoding a polysulfide reductase1 (Psr).

Psr is the enzyme responsible for quinone-coupled reduction of polysulfides, a class of compounds composed of chains of sulfur atoms, which in their simplest form are present as an anion with general formula Sn2−. In nature, polysulfides are found in particularly high concentrations in extreme environments, usually volcanic or geothermically active, such as deep-sea vents and hot springs11. Here, the reduction and oxidation of polysulfides are vital processes for many bacteria and are essential steps in the global sulfur cycle. In particular, the reduction of polysulfide to hydrogen sulfide in these environments is usually linked to energy-generating respiratory processes, supporting growth of many microorganisms, particularly hyperthermophiles12,13.

Psr is a membrane bound enzyme belonging to a well studied molybdenum (Mo) or tungsten (W) containing enzyme family; the Mo/W bis-MGD oxidoreductases14. The bis-MGD enzymes are generally composed of two membrane associated subunits and one integral membrane subunit with five to nine membrane spanning helices (TMs). Psr has an integral membrane subunit predicted to have eight TMs15, which does not contain any redox centres, such as the heme b molecules found in many other membrane-bound bis-MGD enzymes16,17.

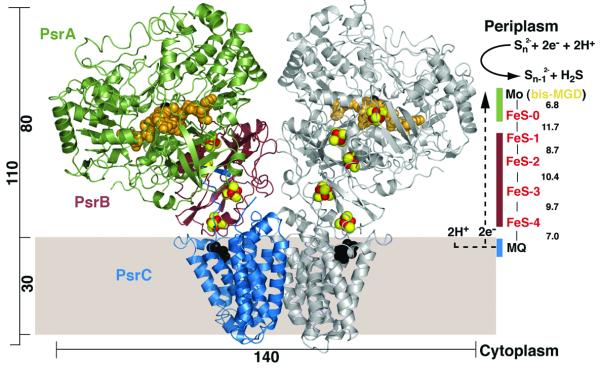

During the reaction cycle of Psr, two electrons and two protons are released from the bound substrate, MK-7, and the electrons are transferred via five 4Fe-4S iron-sulfur clusters to the bis-MGD cofactor to reduce polysulfide. The reactions Psr catalyzes are summarized as follows (also see Fig. 1);

Previously, it has been shown that another bis-MGD enzyme, the periplasmic nitrate reductase (Nap), is coupled to aerobic respiration in Rhodobacter sphaeroides18, where it is suggested to play a key role in redox balancing and protecting the cell from over-reduction of the quinone pool19. Recently it was also revealed that, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) reductase, a bis-MGD enzyme, is expressed in high levels in Escherichia coli during aerobic growth. This enzyme was proposed to be involved in pH homeostasis20. Taken together, these results suggest that bis-MGD enzymes have more versatile and diverse roles in cellular homeostasis and physiology than previously thought.

Figure 1.

Overall structure of Psr. Ribbon representation of PsrABC dimer viewed parallel to the membrane, with one monomer illustrated in light grey for clarity. The PsrA, PsrB, and PsrC subunits in the monomer to the left are colored green, ruby, and blue, respectively. The MGD cofactors are illustrated in orange and Mo is shown in black. Five [4Fe-4S] clusters are shown in red (Fe atoms) and yellow (S atoms), and PCP is illustrated in black. All distances, including edge-to-edge distances between redox centres, are in Å. In the catalytic cycle of Psr, menaquinol is reduced on the periplasmic side of the membrane, releasing two protons and electrons (dotted line). The electrons are transported via the iron-sulfur clusters to the active site Mo, where polysulfide is reduced with the evolution of hydrogen sulfide. All structural figures were made using PyMOL (http://pymol.sourceforge.net).

High expression levels of Psr have been detected in T. thermophilus during aerobic growth. Hence, the existence of a classically anaerobic sulfur enzyme in T. thermophilus raises intriguing questions with regard to physiological function, and what potential importance it plays in cellular respiration. Furthermore, whereas enzyme activity involving oxygen atom transfer to or from substrate has been well characterized for bis-MGD enzymes21-23, the precise mechanism by which microorganisms reduce sulfur remain unclear.

In an effort to answer these questions, and to define the architecture of polysulfide reductases and related enzymes, we have determined the high-resolution structures of native and quinone-bound polysulfide reductase from T. thermophilus. The structures provide comprehensive insight into quinone-linked polysulfide reduction, and we propose a possible key link to T. thermophilus energy conservation via a previously uncharacterized proton pumping mechanism.

RESULTS

Overall structure

We have solved crystal structures of the native T. thermophilus Psr and complexes of Psr with three quinone analogs. The crystal packing reveals an (ABC)2 dimer configuration, with a total molecular weight of ~260 kDa (Fig. 1). The dimer is likely to be physiological. This is supported by an extensive interface between the two heterotrimeric (ABC) monomers (2,614 Å2), and an intricate hydrogen bond network between the PsrB subunits in the dimer. A dimeric configuration was also found to be physiological for nitrate reductase (NarGHI), another membrane-bound enzyme in the bis-MGD oxidoreductase family17. The overall molecular organization of PsrABC resembles those of formate dehydrogenase-N (FdnGHI) and NarGHI16,17, with two membrane associated (PsrA and PsrB) and one integral membrane subunit (PsrC).

The PsrA and PsrB subunits are situated on the same side of the inner membrane as the N- and C-terminus of the PsrC subunit, which hydropathy analyses indicate to be situated in the periplasm15,24. In addition, the N-terminus of PsrA contains a ‘twin arginine translocase’ (TAT) motif, indicating that this subunit is a substrate of the TAT translocase machinery25. N-terminal sequencing and the structure of the PsrA subunit illustrate an absence of the first 28 amino acids (including the TAT signal motif), suggesting that this signal has been processed and that the PsrAB dimer is situated in the periplasmic space.

The catalytic PsrA subunit

The PsrA subunit (733 residues) contains two molybdopterin guanine dinucleotide cofactors (bis-MGD), designated P and Q following the DMSO reductase nomenclature26, and a cubane-type [4Fe-4S] cluster.

The subunit folds into four distinct domains that are related by an internal pseudo two-fold symmetry. Domain I includes four Cys residues coordinating the [4Fe-4S] cluster, designated FeS-0. Domains II and III form α/β sandwiches, anchoring the bis-MGD cofactor through multiple hydrogen-bonding interactions. The fourth domain is a β-barrel structure and participates in the coordination of the bis-MGD cofactor. The four domains can be superimposed on the corresponding domains of the FdnG subunit from E. coli FdnGHI with an r.m.s. deviation of 1.84 Å for 525 Cα atoms, using the program O27. The major differences between the two structures are found in the channel leading from the periplasm to the active site. The region is shaped like a ‘funnel’, formed by the α/β sandwiches in Domains II and III, with the active site situated at the bottom (Fig. 2a, b). The opening of the funnel is narrow, and residues (predominantly with basic side chains) lining the entrance are possibly important for substrate selectivity, as has been suggested for other bis-MGD enzymes28.

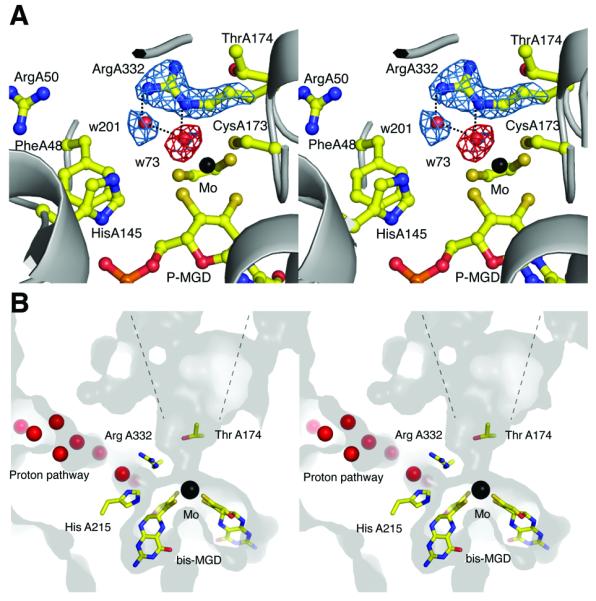

Figure 2.

Stereoviews of the active site. (a) 2|Fo|−|Fc| electron density map (blue) is shown for Arg A332 and w201, and |Fo|−|Fc| map (red) is shown at the position for the oxo (=O) group (omit map for the oxo) bound to the Mo atom. Maps are contoured at 2 and 4 σ, respectively. Hydrogen bonds between Arg A332 and water molecules are shown as dotted lines. (b) Stereoviews of the active site and putative proton delivery channel in PsrA. The surface and interior of the protein are shown in light and dark grey, respectively. Crystallographic water molecules are shown as red spheres.

The crystals of Psr were obtained under oxidizing (aerobic) conditions. The Mo is therefore likely to be present in its oxidized MoVI state. In the crystal structure of the native enzyme, the Mo ion is coordinated by the sulfur group of CysA173, and a water molecule (w73), in addition to the four sulfurs provided by the cis-thiolate groups of the bis-MGD cofactor (Fig. 2a). The average distance between the cis-thiolate S and Mo is 2.35 Å, while the distances between Mo and S (CysA173), and Mo to w73 are 2.24 Å and 2.14 Å respectively. The coordination geometry of the Mo ion resembles that of a trigonal prism, in agreement with previous bis-MGD structures14. The distance between w73 and Mo indicates that it is an oxo (O=) group and not a hydroxide (OH-) group. An additional water molecule (w201) is situated 2.52 Å from w73 (Fig. 2a). In our structure, ArgA332 provides hydrogen bonds to the two water molecules.

This ligation pattern where an Arg residue is coordinating two water molecules is a common feature among peroxidases29,30, although it has previously not been observed in bis-MGD enzymes. In peroxidases, an Arg residue coordinates two water molecules that are generated through the reduction of H2O2, a reaction that is catalyzed by a His residue and heme Fe29,30. By structural analogy, it is possible that the two water molecules (w73, w201) in our structure represent the positions of two sulfur atoms in the polysulfide substrate, and that ArgA332 is key to the coordination of the substrate at the active site. In addition, Nε2 of HisA145 lies in close proximity to w201 and could be involved during substrate turnover, possibly acting as a general acid-base catalyst in the reaction, as observed in peroxidases29.

Other residues in close proximity to the active site include PheA48, ArgA50, SerA169, ThrA174, and HisA215, which may be involved in substrate specificity or in the catalytic cycle (Fig. 2). PheA48 corresponds to Trp116 in R. capsulatus DMSO reductase, a residue that has been shown to be important for substrate coordination31. In addition, HisA215 may be involved in proton delivery to the active site; a highly structured solvent chain leads from this residue to the exterior of the protein (Fig. 2b).

Previously, structural determination of bis-MGD enzymes has illustrated details of catalytic reactions involving transfer of an oxygen atom32. In contrast, the tetrathionate-, thiosulfate-, and polysulfide reductases catalyse reactions involve either sulfur transfer (rather than oxygen transfer) or reductive cleavage of an S–S bond33. In these reactions it has been postulated that the substrate remains directly ligated to the Mo center during the catalytic cycle, giving a Mo[S]6 core34. Assuming that S atoms replace water molecules w73 and w201, we can postulate that Mo is indeed hexa-coordinated by S atoms during the catalytic cycle, and that ArgA332 is acting as a direct ligand to the substrate. Hence, binding of the substrate would cleave the polysulfide, releasing S(n-1)2− and leaving a Mo[S]6 core. The delivery of electrons and protons would thereafter generate H2S and leave a Mo[S]5 core.

The electron transfer in PsrB

The PsrB subunit is composed of 194 residues and belongs to a superfamily of [4Fe-4S] containing electron transfer subunits that are commonly found in oxidoreductases35. Accordingly, PsrB shows high sequence identity with the corresponding subunits of tetrathionate and membrane bound DMSO reductases, and has a similar fold to the corresponding subunit of Nar and Fdh-N.

The four FeS clusters in PsrB and FeS-0 (in PsrA) are aligned in a single chain, and the distances between the adjacent redox centers are well within the 14 Å limit for physiological electron transfer36 (Fig. 1). The redox potentials for the Psr clusters are not known; however, those for E.coli DMSO reductase and Nar have been determined to −50/180 (FeS-4), −120/−50 (FeS-3), −330/−420 (FeS-2), and −240/130 (FeS-1) mV, respectively37. The clusters for both of these enzymes show a similar distribution of redox potentials. Therefore it is possible that the Psr clusters follow the same pattern. It has been observed that these enzymes show much faster enzymatic turnovers than the calculated electron transfer rates based on the measured redox potentials and distances36. This is explained by the re-organization of charges during the electron transfer, which affects the redox potentials of the clusters. This also seems to be the case for Psr as the reported kcat, ca 3,000 s−1 for polysulfide reduction using tetrahydrobiopterin38, is considerably faster than the estimated electron transfer rate (several 100 ms) based on the distances for Psr and the redox potentials for DMSO reductase36,37.

In DMSO reductase, the FeS-4 of DmsB (corresponding to PsrB) has been shown to be the first electron acceptor in the electron transfer pathway from MKH2 to Mo36, and mutations to residues in the immediate environment of FeS-4 were shown to have a marked effect on the electron transfer from MKH2 to the cluster. The DmsB mutant Pro80His/Pro80Asp rendered the enzyme incapable of accepting electrons from the MKH2 site37. The corresponding residue in our structure (ProB71) lies proximal to FeS-4 and in the direct pathway of electrons from MKH2 to FeS-4. Mutations to these residues could therefore lead to structural rearrangements in the local environment, impairing electron transfer from the quinone binding pocket (see below) to the FeS-4.

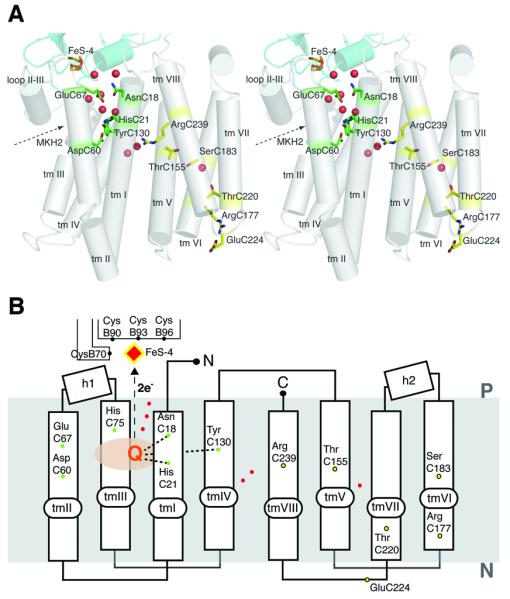

Integral membrane subunit PsrC

The PsrC subunit (250 residues) is composed of eight transmembrane helices, (labeled tmI-tmVIII), which are divided into two four-helix bundles designated hb1 (N-terminal) and hb2 (C-terminal) (Fig. 3). PsrC contains the MKH2 oxidation site, but lacks other redox centres. The two four-helix bundles are tilted approximately 15° to the membrane normal in opposite directions, resembling the letter ‘X’. Both the N- and C-termini are situated in the periplasmic space, and are tethered to the rest of the protein through an intricate hydrogen-bonding network. The loops connecting the eight TMs of PsrC are shorter than in homologous subunits (see below), a typical property of thermostable proteins39. Two C subunits form a very stable dimer through the extensive hydrophobic interactions between the hb2 domains (buried surface ~745 Å2). The sequences of hb1 and hb2 show a considerable (26%) identity indicating that PsrC is a product of a gene duplication event. However, the two domains differ in the lengths and tilt angles of the individual helices, preventing superimposition of their 3D structures.

Figure 3.

Structure of the integral membrane subunit. (a) Cylinder representation of PsrC viewed parallel to the membrane. Trans-membrane helices are numbered from tm I to tm VIII. Residues involved in quinone coordination (green) and residues implicated in the proton pumping mechanism (yellow) are also shown. Crystallographic water molecules are shown as red dots. (b) Schematic representation of PsrC. The residues involved in quinone coordination and postulated proton pathways are shown as green and yellow dots, respectively (see main text for details). Crystallographic water molecules are shown as red dots.

The overall tertiary fold of the subunit is very different from the membrane anchors of other structurally characterized quinone-oxidoreductases. Previous structures of membrane-bound bis-MGD enzymes have revealed five TMs16,17, while succinate dehydrogenases and fumarate reductases contain six TMs40-44. The Psr structure is the first representative of the ‘NrfD-type’ family (Pfam 03916) of membrane-bound bis-MGD quinone-oxidoreductases. This includes tetrathionate-, DMSO-, polysulfide, and nitrite reductases (NrfD). These enzymes have in common a subunit with 8 or 9 predicted TMs and have an active site on the periplasmic side of the membrane, which receives electrons from quinol oxidation sites situated in membrane embedded subunits33.

Quinone binding pocket

The quinone binding site was characterized by co-crystallization experiments using (i) MK-7, the only known quinone of T. thermophilus3, (ii) an inhibitor pentachlorophenol (PCP) and (iii) ubiquinone-1 (UQ1). In the crystal structures, all three compounds were found in the same pocket, suggesting this site is the physiological quinone-binding site (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2 online). The pocket is situated on the periplasmic side of the membrane in the N-terminal four-helix bundle (hb1), and in close proximity to FeS-4 (Fig. 3). It is composed of residues from tmII, tmIII and the horizontal helix between tmII and tmIII (hII-III) of hb1 and from a short loop region (residues B91-B95) of the PsrB subunit.

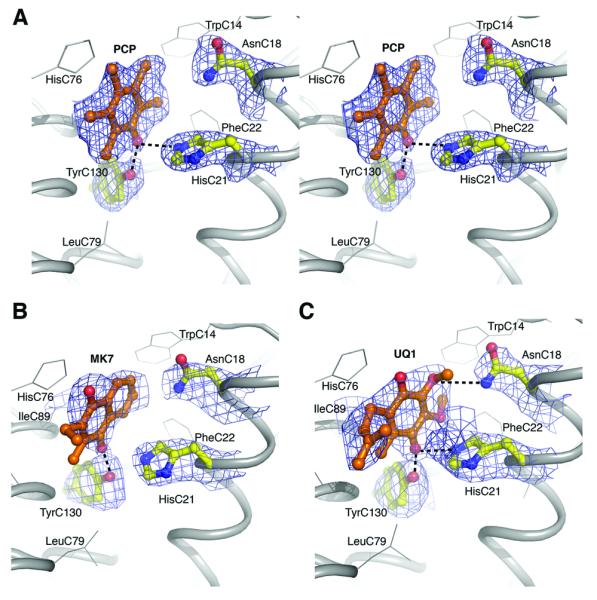

Fig. 4.

Quinone binding site in hb1. (A) Stereo view of omit map and atomic model of PCP. |Fo|−|Fc| map contoured at 1.5 σ. Residues implicated in PCP coordination are also shown. Hydrogen bonds are illustrated as dotted lines. (B) MK-7 coordination. |Fo|−|Fc| omit map contoured at 1.0 σ (C) UQ1 coordination. |Fo|−|Fc| omit map contoured at 1.0 σ

The pocket is mainly hydrophobic, with the quinone sandwiched between LeuC64 and IleC89, and surrounded by the side chains of TrpC14, PheC22, LeuC79, AlaC93, LeuC96, and IleB91. The three quinone analog complexes exhibit slight variations with respect to the hydrogen bonding of the substrate (Fig. 4). In the MK-7 bound structure, the side chain of TyrC130 is a direct ligand of the O1 carbonyl group. The nearby HisC21 is too far away to provide an additional hydrogen bond (O1- HisC21 4.1 Å). However, in the PCP bound structure, both TyrC130 and HisC21 act as ligands to the hydroxyl group of PCP, which is equivalent to O1 in MK-7. Hence, we cannot exclude the possibility that HisC21 takes part in quinone binding. Histidine residues are often involved in quinone coordination16,17. Interestingly, the equivalent residue to T. thermophilus HisC21 is a Tyr residue in all homologous enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). Replacement of this residue with a phenylalanine in PsrC of W. succinogenes (Y23F) causes loss of enzyme activity38, indicating that a polar or ionizing residue at this position is essential for activity and/or quinone binding. The O4 carbonyl of MK-7 is un-coordinated in the crystal structure. However, it is possible that water molecules not resolved in the electron density map are acting as ligands, as was suggested for Nar, Fdh-N, and Sqr16,17,40. It is also possible that the reduced MK-7 binds slightly differently in the binding pocket during the oxidation cycle, as proposed for Sqr45. In the UQ1-Psr complex structure, AsnC18 is hydrogen bonded to the methoxy1 group of UQ1, thus this residue could also be involved in the substrate specificity or form a part of the proton ejection pathway to the periplasm.

Other residues in the quinone binding pocket, which may play a role in the oxidation cycle of MKH2, are the ionisable residues AspC60 and GluC67. AspC60 is not found in other NrfD type enzymes; AspC60 is in hydrogen bonding distance to HisC21, and sequence alignment shows that the hydrogen bonded pair of AspC60 and HisC21 are in all related enzymes replaced by a tyrosine residue (Supplementary Fig. 3). GluC67 is invariantly a carboxyl or histidine residue in NrfD type enzymes and some mutants of this residue have reduced activity in W. succinogenes, indicating that it could be involved in proton transfer from the Q-site to periplasm38.

Putative proton pathway

In the C-terminal four-helix bundle, hb2, no binding pocket for quinone or any other cofactor was found. However, the domain contains several conserved residues that could be of functional importance. A charged residue, ArgC239 (tmVIII; Fig. 3), is in close proximity to the MK-7 binding site. This residue is strictly conserved in polysulfide-, tetrathionate-, nitrite-, and DMSO reductases. The corresponding residue in the homologous W. succinogenes PsrC subunit was mutated (R305K; W. succinogenes numbering) and resulted in an inactive enzyme38. It was suggested that the Arg residue stabilizes the deprotonated quinone38. However, in our structure the guanidinium group is situated ~ 10 Å from the quinone (ArgC239- MK-7 O1) and approximately 5 Å toward the cytoplasmic side of the membrane median. Although the residue could still be coupled to the charge of the quinone, it is too far away to be directly involved in quinone binding. One possible role for ArgC239 is in stabilization of the helices close to the MK binding site. The guanadinium group of ArgC239 is hydrogen bonded to the main chain carbonyl groups of PheC22 and PheC152, bridging tmI and tmV. In Fdh-N a histidine residue (Hisβ275) was proposed to play a similar role16.

A more intriguing proposal would be that ArgC239 is part of a conformational proton pump. Psr has been reported to have an H+/e− ratio of 0.5 (ref. 38,46). In other words, Psr could translocate one H+ from the cytoplasm to the periplasm during the two electron reduction of polysulfide using MKH2. Our Psr structure reveals that the MKH2 binding site is on the periplasmic side. This means that there is no charge/proton transfer during the reactions, given that both protons from MKH2 are released into the periplasm (two protons and two electrons are released from MKH2 and received by polysulfide on the same side of the membrane).

In addition, the Psr structure reveals that PsrC accommodates a possible proton relay network. Central to this is a hydrophilic cavity partially occupied by water molecules (Fig. 3). This is similar to proton pathways observed in cytochrome c oxidases47,48. The relay network starts from GluC224 and ArgC177 on the cytoplasmic surface of hb2, and leads through hb2 to ArgC239 via ThrC220, SerC183, a water molecule and ThrC155 (Fig. 3). The pathway from this point is less clear. One possibility is that it reaches the periplasmic surface through several polar residues in the hb2. More likely the pathway crosses over to hb1 and connects to AspC60 and HisC21, via three water molecules observed around ArgC239 (Fig. 3). Taken together, this suggests that Psr could incorporate an additional proton-translocation-machinery, energized by redox reactions in the quinone site as proposed for Complex I (ref. 49,50). Such proton-translocation-machinery based on redox reactions coupled to conformational changes would provide an attractive mechanism for efficient energy conservation in T. thermophilus.

Confirmation of the precise nature and functional role of this proposed proton pathway awaits future experiments. In these, mutagenesis work should be paralleled with the development of reliable activity assay systems for both polysulfide reduction by MKH2 and proton pumping, which to date has been difficult due to fast self-oxidation of MKH2 and high proton permeability of liposomes at the physiological temperature of the enzyme (ca 440K). Also, the key residues shown in this paper are, despite a general low homology between thermophilic and mesophilic organisms, conserved in homologous enzymes in other bacteria. Therefore, comparative studies with other members of the ‘NrfD-type’ family would be very informative, as it has (for example) been reported that E. coli DMSO reductase does not translocate protons51.

DISCUSSION

The crystal structure of Psr presented here provides molecular insight into sulfur reduction by bis-MGD enzymes. The proximate environment of the active site in PsrA indicate that ArgA332 is critical for substrate coordination, and comparison with peroxidase reveal a plausible reaction mechanism for reduction of polysulfide. Furthermore, the structural information provided by the quinone analog complexes presents a major contribution to the limited number of available structures of quinone-interacting membrane complexes. Analysis of the complexes provides a detailed characterization of the MK-7 binding site in PsrC (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 2). A number of residues were identified as important for quinone coordination and proton removal, although the relative importance of the individual residues is difficult to establish, as there could be conformational flexibility during the quinone turnover. However, mutants of equivalent residues to HisC21, TyrC130, and GluC67 in W. succinogenes38 nearly abolished activity, indicating that these are of particular importance.

The structure of Psr unveiled a new architecture of the membrane anchor protein. The detailed structural analyses lead to the proposal of a proton pump scheme utilizing conformational change in the membrane domain. Previous studies of membrane bound bis-MGD enzymes have shed light on anaerobic proton motive force generation by the redox loop mechanism and provided details with regard to their catalytic mechanisms16,17. Psr has previously only been discussed in anaerobic respiratory pathways where they have been implicated as a component of redox loops. However, high expression levels of an electroneutral Psr under aerobic conditions contradicts previous observations and it raises questions with regard to its coupling to respiration in T. thermophilus. One explanation is that in hot springs, where the dissolved oxygen level is low, presence of an alternative oxidase system that can utilize abundant polysulfide for proton pumping would provide a selective advantage.

In summary, our structural studies represent an important first step towards a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism and function of polysulfide reductase and provide a framework for further investigations. Importantly the structure not only confirms many previous functional and mechanistic proposals, but also engenders a number of new experimentally testable hypotheses.

METHODS

Protein purification and crystallization

We cultured T. thermophilus cells as described in ref. 52. After harvesting, cells were run twice through a French press and membranes were harvested by centrifugation for 3 hours at 45k × g. Membranes were resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, before addition of Triton-X100 (Tx100) to a final concentration of 10 % (v/v). Unsolubilized protein and debris were pelleted by centrifugation at 45,000 × g, and the supernatant containing the solubilized membrane protein was applied to a pre-equilibrated (buffer A; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 + 0.1 % (v/v) Tx100) Q-Sepharose FF column (Pharmacia, Sweden). Protein was eluted using a linear gradient from buffer A to buffer B (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 400 mM NaCl, 0.1 % (v/v) Tx100), with Psr eluted at approximately 250 mM NaCl.

Psr containing fractions were concentrated and diluted with buffer A until the NaCl concentration was approximately 100 mM. The sample was then applied to a DEAE column (Merck, Germany), pre-equilibrated with buffer C (buffer A + 100 mM NaCl), and eluted with a linear gradient from 100-280 mM NaCl. Psr fractions were pooled, concentrated, and loaded onto a Superdex-200 gel filtration column (Pharmacia, Sweden). The column was pre-equilibrated and run at 0.5 ml min−1 with buffer containing 30 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.05 % (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM). Psr eluted from the gelfiltation step was buffer exchanged to 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 containing 0.05 % (w/v) DDM using an Amicon Ultra-15 with 100 Mw cut-off filter and concentrated to approximately 15 mg ml−1. The purity of the sample was approximately 95 %, as estimated by SDS-PAGE, and individual subunits were confirmed by mass spectrometry.

The native complex was crystallized at 20°C by the hanging drop vapour diffusion method, by mixing 1 μl of protein solution with 1 μl of reservoir solution containing 0.1 M MES pH 6.5, 30-34 % (v/v) PEG400, and 200 mM CaCl2. Crystals appeared within 48 hours and grew to full size in approximately 2 weeks. The contents of the crystals were confirmed by analyzing washed and dissolved crystals on SDS-PAGE. Data for menaquinone- or inhibitor-bound structures were obtained from co-crystallization experiments, where the menaquinone/inhibitor was added to the reservoir solution before mixing with protein solution. Concentrations for inhibitors in co-crystallization setups were 0.5 mM for PCP, and 1mM for UQ1 and MK-7 (all from Sigma).

Data collection and structure determination

The data collection and structure refinement statistics are presented in Table 1. Three wavelength MAD data near the Fe K-edge were collected with a MARmosaic 225 CCD detector at beamline ID23-1 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble). PCP-inhibitor data were collected with an ADSC Q4 CCD detector at beamline ID14-2 at ESRF, while native (high-resolution), Q1- and MK-7 complex data were collected using a MARmosaic 300 detector at beamline ID23-D at the Advanced Photon Source (APS, Chicago). All image data were collected at 100K and processed using Denzo & Scalepack53 or Mosflm54 and Scala55. Crystals belonged to the orthorhombic space group P212121 with cell dimensions a = 115.3 Å, b = 163.6 Å, and c = 238.9 Å containing two molecules in the asymmetric unit. The positions of the ten iron-sulfur clusters in the asymmetric unit were initially determined using MAD peak data in SnB56. The phasing power values (acentric/centric) were 0.76/0.26 and 0.85/0.26 for the Fe peak and inflection data sets, respectively. The ‘superclusters’ were refined using MLPHARE55, followed by 100 cycles of density modification in DM55, using two-fold non-crystallographic symmetry averaging and 72 % solvent content. DM was furthermore used for phase extension to 2.8 Å resolution (high resolution native data; Table 1), after which the density was readily interpretable (Supplementary Fig. 4 online).

Table 1.

Data collection, phasing and refinement statistics for MAD (Fe), native, and inhibitor bound structures

| Native | PCP- complex |

MK- complex |

Q1- complex |

Fe-MAD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||||

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | ||

| Cell dimensions | |||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 118.4, 166.3, 246.4 |

116.5, 165.5, 245.4 |

115.4, 163.6, 238.9 |

114.6, 161.2, 239.6 |

117.0, 164.8, 244.4 |

||

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

90, 90, 90 |

90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

90, 90, 90 | ||

| Peak | Inflection | Remote | |||||

|

|

|||||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0332 | 0.9333 | 0.9793 | 0.9793 | 1.7400 | 1.7425 | 0.9330 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40-2.4 (2.53- 2.4) * |

40-2.5 (2.64- 2.5) |

40-3.1 (3.27-3.1) |

40-3.1 (3.27- 3.1) |

40-2.8 (2.95-2.8) |

40-2.8 (2.95-2.8) |

40-2.8 (2.95- 2.8) |

| R merge | 0.106 (0.576) |

0.115 (0.633) |

0.107 (0.555) |

0.120 (0.573) |

0.096 (0.463) |

0.085 (0.186) |

0.073 (0.247) |

| I/σI | 6.5 (1.8) | 10.6 (1.6) |

12.7 (2.1) | 10.7 (1.9) |

18.4 (2.0) | 21.5 (2.1) | 20.5 (2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 93.5 (88.9) |

94.9 (89.9) |

96.7 (97.7) |

99.5 (100.0) |

97.6 (88.1) | 97.9 (88.7) |

93.4 (77.6) |

| Redundancy | 3.5 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| Refinement | |||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 40.0-2.4 | 40.0-2.5 | 40.0-3.1 | 40.0-3.1 | |||

| No. reflections | 621,212 | 783,961 | 373,618 | 300,226 | |||

| Rwork/Rfree | 24.9/25.3 | 28.3/28.9 | 27.1/27.5 | 30.1/31.4 | |||

| No. atoms | |||||||

| Protein | 18638 | 18638 | 18638 | 18638 | |||

| Ligand/ion | 270 | 294 | 300 | 306 | |||

| Water | 1306 | 1306 | 1306 | 1306 | |||

| Average B-factors | |||||||

| Protein | 58.9 | 55.6 | 77.0 | 78.3 | |||

| Ligand/ion | 47.2 | 65.4 | 64.1 | 63.5 | |||

| Water | 67.1 | 82.7 | 82.7 | 85.0 | |||

| R.m.s deviations | |||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.025 | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.020 | |||

| Bond angles (°) | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 | |||

Two crystals were used to solve the native structure, in addition to one crystal for each inhibitor complex.

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

The model was manually built into the experimental density map using the program O28. Refinement was carried out with alternating cycles of REFMAC55 and manual rebuilding. Water molecules were found using the program ARP57, and final refinement rounds were performed using the program CNS58, with the native structure refined to 2.4 Å resolution with Rwork of 0.249 and Rfree of 0.253. The final model contains two molecules with a total of 2,346 residues, ten [4Fe-4S] clusters, two Mo-bis-MGD cofactors, and 1306 water molecules. The geometry of the model was checked using the program PROCHECK59. For the final refined structure, 84.7% and 15.3% of the residues were in the favored and allowed regions, respectively, of the Ramachandran plot.

Structures of inhibitor bound complexes and native high-resolution structure were obtained by rigid body refinement using REFMAC55, and final refinement in CNS58. All water molecules from the native high-resolution structure were kept for the quinone analog complexes as this gave the lowest R-values.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Australian Research Council (ARC; DP0666970 to M.J.), Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (No. 18370055 and 19042008 to K.Y.). M.J. was recipient of the EMBO Long-term Fellowship. Data collection was done at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) and GM/CA-CAT at Advanced Photon Source (APS). The authors acknowledge support of Stephen Corcoran, Nagarajan Venugopolan, and Michael Becker at GM/CA-CAT, and beamline scientists at ID23-1, ESRF, for scientific support and assistance with data collection. GM/CA-CAT beamline (ID23) is supported by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of General Medical Science. Visits to APS were supported by Australian Nuclear Science Technology Organization (ANSTO). A part of the work was performed at the Diamond Membrane protein Laboratory supported by the Wellcome trust. M.J. has been a European Molecular Biology Organization Long-Term Fellow. We thank U. Kappler, M. Maher, M. Rapp, B. Byrne, and L. Carpenter for critical assessment of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Accession codes. Protein Data Bank: Coordinates and structure factors for the native and quinone analog complexes have been deposited with accession codes 2VPW (MK-7), 2VPX (UQ1), 2VPY (PCP), and 2VPZ (native).

References

- 1.Henne A, et al. The genome sequence of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:547–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yano T, Chu SS, Sled' VD, Ohnishi T, Yagi T. The proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (NDH-1) of thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus HB-8. Complete DNA sequence of the gene cluster and thermostable properties of the expressed NQO2 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4201–4211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins MD, Shah HN, Minnikin DE. A note on the separation of natural mixtures of bacterial menaquinones using reverse phase thin-layer chromatography. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1980;48:277–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1980.tb01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hon-Nami K, Oshima T. Purification and some properties of cytochrome c552 from an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus HB8. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 1977;82:769–776. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mooser D, et al. A four-subunit cytochrome bc(1) complex complements the respiratory chain of Thermus thermophilus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1708:262–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann BH, Nitsche CI, Fee JA, Rusnak F, Munck E. Properties of a copper-containing cytochrome ba3: a second terminal oxidase from the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:5779–5783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fee JA, Yoshida T, Surerus KK, Mather MW. Cytochrome caa3 from the thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus: a member of the heme-copper oxidase superfamily. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1993;25:103–114. doi: 10.1007/BF00762852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soulimane T, et al. Structure and mechanism of the aberrant ba3-cytochrome c oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 2000;19:1766–1776. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keightley JA, et al. Molecular genetic and protein chemical characterization of the cytochrome ba3 from Thermus thermophilus HB8. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:20345–20358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fee JA, Choc MG, Findling KL, Lorence R, Yoshida T. Properties of a copper-containing cytochrome c1aa3 complex: a terminal oxidase of the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus HB8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1980;77:147–151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock TD. Thermophilic microorganisms and life at high temperatures. Springer-Verlag; New York, N.Y: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blöchl E, et al. Pyrolobus fumarii, gen. and sp. nov., represents a novel group of archaea, extending the upper temperature limit for life to 113 degrees C. Extremophiles. 1997;1:14–21. doi: 10.1007/s007920050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Schoonen MAA, Nordstrom DK, Cunningham KM, Ball JW. Sulfur geochemistry of hydrothermal waters in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, USA. II. Formation and decomposition of thiosulfate and polythionate in Cinder Pool. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2000;97:407–423. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothery RA, Workun GJ, Weiner JH. The prokaryotic complex iron-sulfur molybdoenzyme family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.09.002. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothery RA, Kalra N, Turner RJ, Weiner JH. Sequence similarity as a predictor of the transmembrane topology of membrane-intrinsic subunits of bacterial respiratory chain enzymes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;4:133–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jormakka M, Törnroth S, Byrne B, Iwata S. Molecular basis of proton motive force generation: structure of formate dehydrogenase-N. Science. 2002;295:1863–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1068186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertero MG, et al. Insights into the respiratory electron transfer pathway from the structure of nitrate reductase A. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:681–687. doi: 10.1038/nsb969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavira M, Roldán MD, Castillo F, Moreno-Vivián C. Regulation of nap gene expression and periplasmic nitrate reductase activity in the phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides DSM158. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:1693–1702. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.6.1693-1702.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellington MJ, et al. Characterization of the expression and activity of the periplasmic nitrate reductase of Paracoccus pantotrophus in chemostat cultures. Microbiology. 2003;149:1533–1540. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ansaldi M, Théraulaz L, Baraquet C, Panis G, Méjean V. Aerobic TMAO respiration in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;66:484–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raaijmakers HC, Romão MJ. Formate-reduced E. coli formate dehydrogenase H: The reinterpretation of the crystal structure suggests a new reaction mechanism. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2006;11:849–854. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMaster J, Enemark JH. The active sites of molybdenum- and tungsten-containing enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998;2:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hille R. The Mononuclear Molybdenum Enzymes. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2757–2816. doi: 10.1021/cr950061t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner JH, Shaw G, Turner RJ, Trieber CA. The topology of the anchor subunit of dimethyl sulfoxide reductase of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:3238–3244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santini CL, et al. A novel sec-independent periplasmic protein translocation pathway in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1998;17:101–112. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schindelin H, Kisker C, Hilton J, Rajagopalan KV, Rees DC. Crystal structure of DMSO reductase: redox-linked changes in molybdopterin coordination. Science. 1996;272:1615–1621. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1991;47:110–9. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simala-Grant JL, Weiner JH. Modulation of the substrate specificity of Escherichia coli dimethylsulfoxide reductase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;251:510–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berglund GI, et al. The catalytic pathway of horseradish peroxidase at high resolution. Nature. 2002;417l:463–468. doi: 10.1038/417463a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsui T, Ozaki S, Liong E, Phillips GN, Watanabe Y. Effects of the location of distal histidine in the reaction of myoglobin with hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:2838–2844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridge JP, Aguey-Zinsou KF, Bernhardt PV, Hanson GR, McEwan AG. The critical role of tryptophan-116 in the catalytic cycle of dimethylsulfoxide reductase from Rhodobacter capsulatus. FEBS Lett. 2004;563:197–202. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hille R. Molybdenum enzymes. Essays Biochem. 1999;34:125–37. doi: 10.1042/bse0340125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hensel M, Hinsley AP, Nikolaus T, Sawers G, Berks BC. The genetic basis of tetrathionate respiration in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;32:275–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagarajan K, et al. Structural and functional analogue of the active site of polysulfide reductase from Wolinella succinogenes. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:4532–4533. doi: 10.1021/ic049665i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berks BC, et al. Sequence analysis of subunits of the membrane-bound nitrate reductase from a denitrifying bacterium: the integral membrane subunit provides a prototype for the dihaem electron-carrying arm of a redox loop. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;15:319–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Page CC, Moser CC, Chen X, Dutton PL. Natural engineering principles of electron tunneling in biological oxidation-reduction. Nature. 1999;402:47–52. doi: 10.1038/46972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng VW, Rothery RA, Bertero MG, Strynadka NC, Weiner JH. Investigation of the environment surrounding iron-sulfur cluster 4 of Escherichia coli dimethylsulfoxide reductase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8068–8077. doi: 10.1021/bi050362p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dietrich W, Klimmek O. The function of methyl-menaquinone-6 and polysulfide reductase membrane anchor (PsrC) in polysulfide respiration of Wolinella succinogenes. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:1086–1095. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szilágyi A, Závodszky P. Structural differences between mesophilic, moderately thermophilic and extremely thermophilic protein subunits: results of a comprehensive survey. Structure. 2000;8:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yankovskaya V, et al. Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science. 2003;299:700–704. doi: 10.1126/science.1079605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lancaster CR, Kröger A, Auer M, Michel H. Structure of fumarate reductase from Wolinella succinogenes at 2.2 A resolution. Nature. 1999;402:377–85. doi: 10.1038/46483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iverson TM, Luna-Chavez C, Cecchini G, Rees DC. Structure of the Escherichia coli fumarate reductase respiratory complex. Science. 1999;284:1961–1966. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun F, et al. Crystal structure of mitochondrial respiratory membrane protein complex II. Cell. 2005;121:1043–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang LS, et al. 3-nitropropionic acid is a suicide inhibitor of mitochondrial respiration that, upon oxidation by complex II, forms a covalent adduct with a catalytic base arginine in the active site of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:5965–5972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511270200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horsefield R, et al. Structural and computational analysis of the quinone-binding site of complex II (succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase): a mechanism of electron transfer and proton conduction during ubiquinone reduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:7309–7316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hedderich R, et al. Anaerobic respiration with elemental sulfur and with disulfides. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1999;22:353–381. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwata S, Ostermeier C, Ludwig B, Michel H. Structure at 2.8 A resolution of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature. 1995;376:660–9. doi: 10.1038/376660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsukihara T, et al. The whole structure of the 13-subunit oxidized cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 A. Science. 1996;272:1136–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holt PJ, Morgan DJ, Sazanov LA. The location of NuoL and NuoM subunits in the membrane domain of the Escherichia coli complex I: implications for the mechanism of proton pumping. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:43114–43120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohnishi T, Salerno JC. Conformation-driven and semiquinone-gated proton-pump mechanism in the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4555–4561. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bogachev AV, Murtazina RA, Skulachev VP. H+/e− stoichiometry for NADH dehydrogenase I and dimethyl solfoxide reductase in anaerobically grown Escherichia coli cells. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:6233–6237. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6233-6237.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yokoyama K, Akabane Y, Ishii N, Yoshida M. Isolation of prokaryotic V0V1-ATPase from a thermophilic eubacterium Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:12248–12253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leslie AGW. Joint CCP4 + ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography. 1992;26 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weeks CM, Miller R. The design and implementation of SnB v2.0. J. Appl. Cryst. 1999;32:120–124. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perrakis A, Morris RM, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nature Struct. Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brünger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK - a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Applied Crystallography. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.