Abstract

Motivation: New generation sequencing technologies producing increasingly complex datasets demand new efficient and specialized sequence analysis algorithms. Often, it is only the ‘novel’ sequences in a complex dataset that are of interest and the superfluous sequences need to be removed.

Results: A novel algorithm, fast and accurate classification of sequences (FACSs), is introduced that can accurately and rapidly classify sequences as belonging or not belonging to a reference sequence. FACS was first optimized and validated using a synthetic metagenome dataset. An experimental metagenome dataset was then used to show that FACS achieves comparable accuracy as BLAT and SSAHA2 but is at least 21 times faster in classifying sequences.

Availability: Source code for FACS, Bloom filters and MetaSim dataset used is available at http://facs.biotech.kth.se. The Bloom::Faster 1.6 Perl module can be downloaded from CPAN at http://search.cpan.org/∼palvaro/Bloom-Faster-1.6/

Contacts: henrik.stranneheim@biotech.kth.se; joakiml@biotech.kth.se

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

The era of personal genomics is fast approaching, as a result of which whole human genomes will be obtained on a routine basis. Currently, only a fraction of such sequences contain relevant sought-after information and the remaining sequences need to be removed. More complex datasets are also becoming increasingly available, derived from: metagenome studies that contain a mixture of genetic material from different organisms present in environmental or patient samples (Allander et al., 2005; Rusch et al., 2007); studies of dynamic methylation pattern profiles (Down et al., 2008); and sequencing of re-arranged and mutated genomes (Ley et al., 2008). To handle and analyse this vast amount of data requires fast, accurate and specialized methods that can align a large number of sequences onto genomes or reference sequences. The increasing need for faster algorithms has led to the development of software such as MEGABLAST (Zhang et al., 2000), SSAHA (Ning et al., 2001) and BLAST-like alignment tool (Kent, 2002) for longer DNA sequence reads. More recently, SOAP (Li et al., 2008b), MAQ (Li et al., 2008a), SHRIMP (Rumble et al., 2009), BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009) and Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) have been developed for shorter DNA sequence reads. Many of these algorithms can detect single nucleotide changes.

For most of these existing methods a hash-table must be built containing either the query (BLAST, MAQ and SHRIMP) or reference (SSAHA, BLAT and SOAP) sequences; this hash-table must then be searched to align reads.

One important issue in metagenomic studies is the classification of sequences as ‘novel’, or belonging to a known genome, i.e. filtering out data that has been seen before. There is a need for a fast pre-processing step that reduces the complexity of the data before more careful analysis is performed. Often, it is the novel reads that are of interest and the location of other reads in their originating genomes is irrelevant. This means that alignment tools, such as those mentioned above, actually perform more computations than necessary.

A Bloom filter is a space-efficient data structure with fast look-up times and a manageable risk of producing false positives. It was originally developed by Burton Bloom in the 1970s to reduce the amount of space required to contain hash-coded information (Bloom, 1970). In this article, an algorithm is described, fast and accurate classification of sequence (FACSs), which uses a novel scheme to classify sequence reads as belonging to one of many reference sequences or being ‘novel’. The algorithm transforms the reference sequence into Bloom filters, and then the Bloom filters can be queried for exact matches. This method allows rapid classification of sequences using references as large as the human genome.

In this study, the FACS algorithm was evaluated using a synthetic long-read metagenomic dataset and was compared to conventional methods [BLAT and sequence search and alignment by hashing algorithm 2 (SSAHA2)] with respect to speed, sensitivity and specificity. FACS was then used to analyse and remove human sequences from an experimental metagenomic dataset containing 177 184 sequences generated using a Roche 454-FLX sequencer. This was done in an effort to show that FACS can be used to classify sequences to known genomes while reducing the complexity of the dataset and retain ‘novel’ reads. For this task, FACS was 21 times faster than BLAT and 31 times faster than SSAHA2, while achieving similar accuracy as both methods.

2 METHODS

FACS consists of two Perl scripts, BloomBuild and FACS, which were used, respectively, for creating and interrogating Bloom filters. The Bloom filters were created by supplying the reference sequences to BloomBuild with the desired K-mer and specified Bloom filter false positive rate. The query sequences were then classified according to the references by using the FACS script to interrogate the Bloom filters. Running time for FACS and BloomBuild scales linearly with the total sequence lengths.

2.1 Bloom filters

A Bloom filter can be used to determine whether an element is part of a reference set. It is a very compact hash-based data structure with efficient look-up times and a manageable risk of giving false positives.

A Bloom filter is a bitmap of size m- and k-associated hash functions that maps elements to positions in the bitmap. Initially all bits are set to 0. An element is added to the filter by computing the k hashes and setting the resulting k bitmap elements to 1. To determine whether an element is present in the filter, the k-hash functions are applied to the element and the resulting positions are looked up in the bitmap. If all bits are 1, the element is most likely part of the set; otherwise, the element is definitely not in the set. The time needed to either add or query the filter is constant, O(k), and is independent of the number of elements already in the set.

As mentioned earlier Bloom filters can give rise to false positives because the bit-patterns between elements can overlap. However, since a bit is never set to zero during operations, false negatives are not possible (Bloom, 1970).

The optimal number of k-associated hash functions to use in the Bloom filter is related to the bitmap size m and the number of elements n by the following equation (Broder and Mitzenmacher, 2004):

Therefore, the size of the bitmap must grow linearly with the number of elements in the bitmap to keep a fixed false positive probability.

2.2 Generation of a synthetic metagenome dataset by MetaSim

A synthetic metagenome dataset generated by MetaSim (Richter et al., 2008) was created for evaluating the effect of different parameter settings of the FACS method. Given a set of genomes, MetaSim can collect samples from these genomes to create a metagenome dataset using simulations of different sequencing techniques, for example, Roche's 454-Pyrosequenching (GS-FLX generation). The synthetic metagenome dataset was created by MetaSim (version 0.9.4, built February 18, 2009) using the 454-preset, producing 100 000 reads (Supplementary Table 1). In this task, reads were generated with an average length of 269 nt containing random sequencing errors that were introduced according to the MetaSim 454 sequencing error model. The synthetic dataset consisted of 19 microbial genomes that were also used in the MetaSim software description (Richter et al., 2008), with the addition of three viruses and two human chromosomes. The viral and human sequences were added to further increase the complexity of the synthetic dataset and to mimic the experimental metagenome dataset (Allander et al., 2005) that will be analysed by FACS. The relative abundance of each species was set at 100; therefore, the percentage of reads sampled from each species reflected its genome size. The origin of each sequence generated by MetaSim was recorded in the header of the sequence and served as a key for classification.

2.3 Experimental metagenome sample isolated from the human respiratory tract

DNA and RNA were extracted from pooled naso-pharyngeal aspirates samples (Allander et al., 2005) and subjected to random polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Allander et al., 2001). The generated PCR products were purified by spin column and gel excision (Allander et al., 2005). The purified PCR products were then sequenced on a 454-FLX sequencer at the Royal Institute of Technology, using Roche's shotgun protocol for library preparation and sequencing (Margulies et al., 2005). The sequencing run generated 177 184 reads, from the purified DNA sample, that passed all quality control filters built into the 454 pipeline; these reads were included in this study.

2.4 BLAT and SSAHA2

To compare the performance of different methods, BLAT, SSAHA2 and FACS were used to examine both datasets; these comparative methods were chosen as they represent conventional long DNA read alignment methods, although in this study FACS does not return alignment coordinates. The synthetic dataset also served to ensure that an adequate match score cut-off of sequence identity and alignment length was used. Sequences classified to a reference in each analysis were withdrawn from further analysis since they do not represent ‘novel’ reads.

BLAT (Standalone BLAT version 34) was used with the binary help file 11occ to avoid repetitive and low-complexity sequences (Kent, 2002). In some cases the fastMap option was enabled, as this produces more semi-global and local alignments. Both options improve the speed of BLAT but reduce the sensitivity of the method.

SSAHA2 (version 2.3) was used with the 454 option (-kmer 12, -skip 3, -ckmer 6, -cmatch 10, -seeds 2, -score 30 and sense 1) to tune the algorithm for 454 reads (Ning et al., 2001).

2.5 Investigation of classification characteristics

MEGABLAST was used as a tool to better understand the differences in resulting classification between FACS and the other methods. For this purpose, sequences that had been classified as false positives in the synthetic dataset and uniquely classified in the experimental metagenome dataset were analysed using MEGABLAST. A sequence was identified as a having low-complexity if it was filtered out by MEGABLAST.

MEGABLAST (version 2.2.20, April 21, 2009) and the nt/nr database (downloaded from: ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/db/, April 21, 2009) were used with a word size of 16 (Zhang et al., 2000). A sequence similarity of 45% with an alignment spanning over at least 45% of the query length served as a match cut-off for correct classification. False positives produced with FACS, BLAT and SSAHA2 according to the key from the synthetic dataset were considered as homologues, and thus correctly classified if the sequence produced 500 hits with E-values <10−50 using MEGABLAST. Sequences uniquely classified with each method were further characterized according to MEGABLAST results as: correctly classified if a match according to the match criterion was found to the same reference genome; false positive if no match to the same genome was found and a match in another reference genome was found, which did pass the match criterion; non-significant if no match in any reference genome was found, which passed the match criterion.

3 IMPLEMENTATION

The Perl scripts, BloomBuild and FACS, rely on the Perl module Bloom-Faster-1.5A; an updated version is available from CPAN (http://search.cpan.org/∼palvaro/Bloom-Faster-1.6/, July 6, 2009). When supplied with the number of elements to insert and the allowable false positive probability, the module automatically calculates the optimal number of k-associated hash functions and the size of the bitmap m.

All tests and analyses were carried out on a 2.83 GHz Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU with 23 GiB running Feodora release 10.

3.1 Generation of Bloom filters

The Bloom filters were created using a false positive frequency <0.05%. A filter for each reference genome (Supplementary Table 2) was created by parsing it with a 1-base offset sliding window approach and inserting all subsequences of size K, K-mers, in the filter. It takes ∼500 min to build the filters required for the human genome using a K-mer size of 21 bases. The filters only need to be created once and can then be loaded when required. However, a change in K-mer size requires new filters to be made for that specific K-mer size. The maximum size of Bloom filters used in this study was 312 MB.

3.2 Classification of reads using FACS

For a query to be classified as belonging to a reference genome, it needs to accumulate a match score surpassing a chosen cut-off value, which is based on sequence similarity.

In this study, each query sequence was divided by a sliding window into K-mers and each K-mer was interrogated against the Bloom filter. If a match was found for a K-mer then the sequential K-mers beginning within the matching K-mer were not queried further. Each query accumulated a match score that was related to the K-mer size for every positive hit in the filter, i.e. 1 point for every base. A filtering step called Quick Pass, was included in the algorithm, to faster discard non-significant alignments. Quick Pass was set to use a K-mer offset sliding window approach on the query and to require only one K-mer match in the reference to initiate the more thorough analysis with a 1-base offset sliding window approach. Initial tests showed a high degree of false positives in classification when analysing very short sequences; this was expected due to the small ratio of the query sequence and K-mer size. Therefore, query sequences shorter than 61 bases were removed from the analysis. Sequences classified in each analysis as belonging to a reference were withdrawn from further querying since they do not represent ‘novel’ reads.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Evaluation of the FACS method with the synthetic metagenome dataset

To find adequate parameters for FACS, a synthetic metagenome dataset was created by MetaSim (Richter et al., 2008). One hundred and thousand reads with an average length of 269 bases were sampled in silico using the 454 setting from 19 microbial genomes, 3 viruses and human chromosomes 8 and 21 (Supplementary Table 1). The effect on classification efficiency of the parameters K-mer size and sequence identity match cut-off were investigated while monitoring the number of classified reads and the number of true and false positives (Supplementary Table 3). As expected, increasing the size of the K-mer and the match cut-off resulted in fewer classified reads and fewer false positives. A K-mer size of 17 or 21 bases had acceptable sensitivity to resolve a reference genome as large as human chromosome 8 (146 MB) and allowed accurate classification of ∼98% of the reads. A K-mer size of 21 bases while using 35–80% sequence identity match cut-off resulted in 100% specificity and no false positives.

Interestingly, the longest K-mer used, which consisted of 35 bases, had a small increase in false positive rate while using the 35–40% sequence identity match cut-offs compared to the shorter K-mers. The reason for this is presently unclear.

Reads that were classified as false positives, according to the sampling from MetaSim, using K-mers of 17, 21, 25 and 35 bases were verified using MEGABLAST.

Suspected false positives from the classification that found no match in the corresponding reference genome with MEGABLAST, but over 500 hits and an E-value <10−50, were considered as homologous sequences to the reference genome, and therefore correctly classified. These homolog sequences accounted for <0.056% of all classified reads in the four K-mer sets with the different FACS match cut-off values.

4.2 Comparison of the FACS, BLAT and SSAHA2 methods with the synthetic metagenome dataset

To enable the performance of FACS to be evaluated on the synthetic metagenome dataset it was compared to the performance of BLAT and SSAHA2 on the same dataset (Table 1).

Table 1.

Timing, sensitivity and specificity of FACS versus BLAT and SSAHA2 on the synthetic metagenome dataset

| Method | K-mer | Time | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| size | (min) | (%) | (%) | |

| SSAHA2/454a | 12 | 32.4 | 98.6 | 98.9 |

| BLAT/11occa | 11 | 12.5 | 99.8 | 100 |

| BLAT/11occ/fastMapa | 11 | 1.5 | 43.6 | 100 |

| BLAT/11occ/fastMapb | 11 | 1.5 | 66.4 | 100 |

| FACSb | 21 | 1.7 | 98.1 | 100 |

| FACSc | 21 | 1.7 | 99.8 | 100 |

Sensitivity = true positives/(true positives + false negatives), specificity = true positives/(true positives + false positives). Classified reads were removed from further querying of subsequent reference genomes.

aMatch cut-off: 65% sequence similarity over an alignment spanning at least 70% of the query length.

bMatch cut-off: 45% sequence similarity.

cMatch cut-off: 35% sequence similarity.

The results were comparable for the three methods in terms of sensitivity and specificity, with the exception of BLAT when using the fastMap option, the sensitivity of which suffered from excluding introns and produced many local and semi-global alignments.

When using fastMap, BLAT finished in a similar timeframe as FACS, but had poor sensitivity when this option was selected. Without fastMap, BLAT takes seven times longer than FACS to process the sequences.

SSAHA2, being as sensitive as FACS, required a significantly longer time to process sequences, and took 19 times longer than FACS to finish the classification.

The simulated dataset showed that FACS, using a K-mer size of 17 or 21 bases at different match cut-offs, had adequate sensitivity, specificity and speed to apply it to a real metagenome dataset.

4.3 Evaluation of FACS using an experimental metagenome dataset

FACS, BLAT and SSAHA2 were used to analyse an experimental metagenome dataset (Allander et al., 2005) containing 177 184 reads generated using massive parallel Pyrosequencing from human respiratory tract samples. The metagenome dataset is highly likely to consist of human mitochondrial, as well as human and microbial genome sequences present in the human respiratory tract. The analysis was conducted to determine whether all human and mitochondrial DNA sequences could be filtered out. The nature of sequences uniquely classified with each method was then further characterized using MEGABLAST.

4.3.1 Analysis using the human mitochondrion as a reference

The human mitochondrial reference was run in a separate analysis before the human chromosomal reference to remove mitochondrial sequences from further processing as they do not represent ‘novel’ reads (Supplementary Table 4). Four different match cut-off values for FACS were evaluated when using the mitochondrial reference (Supplementary Fig. 1).

All three methods finished the mitochondrial analysis within 30 s. BLAT was the fastest method followed by SSAHA2, while FACS was the slowest. This is due to the extremely small size (∼16 kb) of the human mitochondrial genome, which enabled a small hash table and index for SSAHA2 and BLAT to sort through, respectively. The small reference also enabled a K-mer size of only 12 bases to be used in the FACS method, which improves sensitivity and specificity compared to using longer K-mers.

The number of classified reads was similar between the three methods, except for BLAT/11occ/fastMap, which classified fewer reads. Most of the classified reads were shared between the methods but each algorithm had a number of reads uniquely classified (Fig. 1). Of the unique SSAHA reads, 50.2% were shorter than 60 bases, and therefore not considered in the FACS classification. Furthermore, 17.3% of the reads were between 61 and 74 bases long, making a mismatch at the end of the read very costly for the FACS algorithm. The remaining 32.4% of the reads were longer than 74 bases.

Fig. 1.

Venn diagram comparing read classification using three methods, with the human mitochondrial genome as a reference.

To understand the differences in classification between the methods, MEGABLAST was used on all sequences uniquely classified by one method. First, a way of interpreting the results returned by MEGABLAST was investigated. Different match cut-off values were used with MEGABLAST to evaluate the reads classified with each method (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, using a long alignment length as a match cut-off with MEGABLAST biases the results towards BLAT and SSAHA2, since FACS do not have an alignment length requirement, while BLAT and SSAHA were unfavoured by using an E-value match cut-off. Therefore, a sequence similarity of 45% with an alignment spanning over at least 45% of the query length was used. Of the unique FACS reads, 96.2% could be verified as belonging to the mitochondrial genome using MEGABLAST (Supplementary Fig. 2A). These are reads that were missed by both SSAHA2 and BLAT. Of the unique BLAT/11occ and SSAHA reads, 100% and 99.1% could be verified by MEGABLAST using the same word size and match criterion, respectively. There were two false positive hits for FACS and SSAHA both belonging to human and no false positive hits for BLAT/11occ according to the results from MEGABLAST using the same match criterion.

Low-complexity reads according to MEGABLAST filtering made up 1.2% of the unique FACS reads.

4.3.2 Analysis using the human genome as a reference

After removal of the mitochondrial sequences, the remaining reads of the experimental metagenome dataset were analysed (Table 2) using the human genome build 36 version 3 as a reference (Supplementary Table 2). Four different match cut-off values for FACS were evaluated when using the human reference (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Classified reads from the experimental dataset using the human genome as a reference

| Method | K-mer Size | Time (min) | Reads Classified |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSAHA2/454a | 12 | 189 | 48 692 |

| BLAT/11occa | 11 | 129 | 39 403 |

| BLAT/11occ/fastMapb | 11 | 11 | 24 244 |

| FACSc | 21 | 6 | 40 074 |

aMatch cut-off: 65% sequence similarity over an alignment spanning at least 70% of the query length.

bMatch cut-off: 45.5% sequence similarity.

cMatch cut-off: 45% sequence similarity.

SSAHA2/454 was 31.5 times slower than FACS and classified slightly more reads.

BLAT/11occ was 21.5 times slower than FACS and reached almost the same number of classified reads. BLAT/11occ/fastMap was 1.8 times slower than FACS, and classified 0.57 times fewer reads.

The results show that FACS is the method that classifies the most sequences in the shortest length of time.

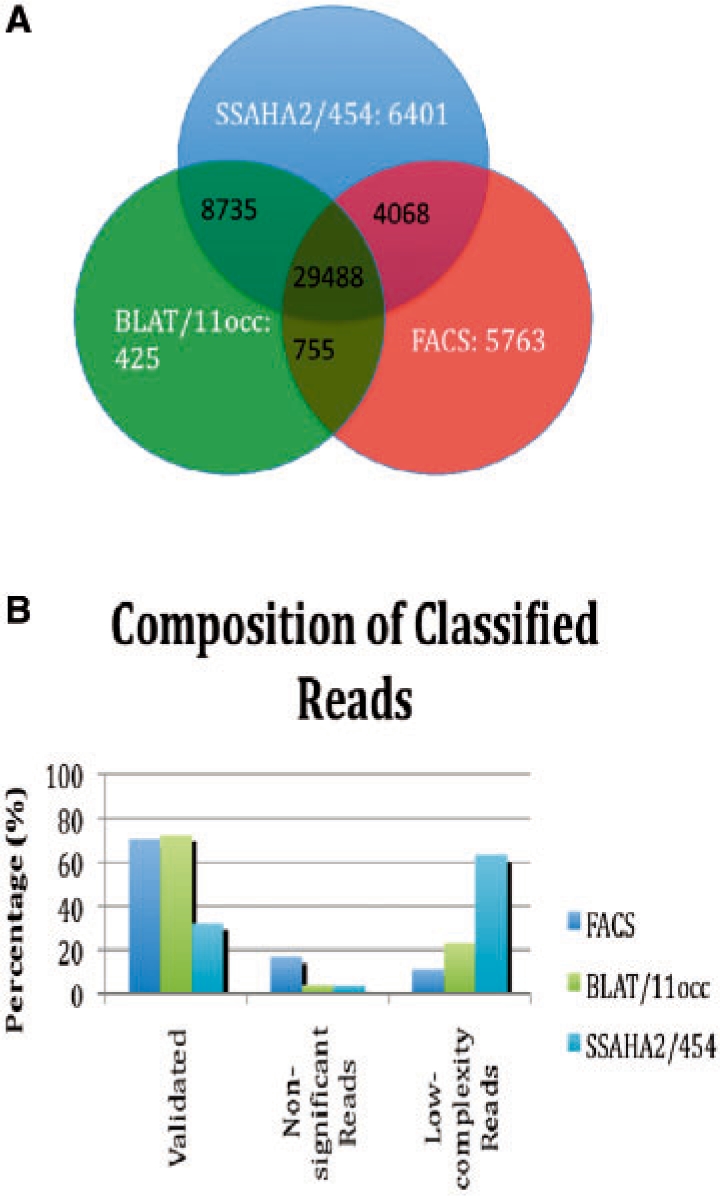

FACS had the highest number of unique reads and only 29 488 of the reads were found in the intersection between all three methods (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

(A) Venn diagram comparing read classification using three methods with the human genome as a reference. (B) Nature of the unique reads for the three methods.

Different match cut-off values were used with MEGABLAST to evaluate the reads classified with each method (Supplementary Fig. 4). As in the mitochondrial analysis a sequence similarity of 45% with an alignment spanning over at least 45% of the query length was used, in an effort to reduce bias. When using MEGABLAST to find common properties in the populations of unique reads, FACS together with BLAT/11occ had the most unique reads that could be verified as being correctly classified (∼70 and 72% respectively, Fig. 2B). Of the unique SSAHA2 reads only ∼32% could be verified by MEGABLAST. SSAHA2 had the lowest percentage of non-significant unique reads (∼3.7%). Surprisingly, SSAHA2 classified the most low-complexity reads (∼63%) even though it should avoid K-mers that are abundant in the genome, while BLAT/11occ had ∼23.1% unique reads that were considered low-complexity by MEGABLAST filtering.

Furthermore, there was a ∼0.06%, 0.001% and 0.04% false positive hit rate for FACS, BLAT/11occ and SSAHA2, respectively.

Of the unique reads that were classified with BLAT/11occ and SSAHA2/skip2, ∼49% were shorter than 61 bases, and therefore rejected from the FACS analysis (as described above in section 3.2).

5 DISCUSSION

This study used a novel algorithm called FACS, which utilizes the compact hash-based data structure of Bloom filters for fast and accurate classification of sequences. The algorithm was optimized using a synthetic metagenome dataset generated by MetaSim, which consisted of 100 000 reads sampled from 19 microbial genomes, 3 viruses and 2 human chromosomes. FACS was then put to the test in removing all human and mitochondrial sequences from a real metagenome dataset containing 177 184 reads generated using massive parallel Pyrosequencing. The sample was derived from a molecular exploration of the human respiratory tract, searching for previously unknown viral species [data to be published elsewhere and see Allander et al., (2005)]. Of the experimental metagenome dataset, 30.9% of the sequences could be classified as belonging to either human or mitochondrial references with FACS. The performance of FACS was evaluated by comparing it to BLAT and SSAHA2. The FACS method was 21 and 31 times faster than BLAT and SSAHA2, respectively, in classifying sequences in the experimental dataset while achieving comparable accuracy. This makes the FACS method ideal for quickly classifying reads to genomes or large references from a complex dataset. As the number of sequences to be analysed increases the advantage of using FACS compared to BLAT or SSAHA2, in terms of speed, should be even more pronounced.

The sensitivity and specificity of the filter is very dependent on the reference filter size, the K-mer size, the match cut-off and the Bloom filter false positive frequency. This study has shown that a K-mer of 17–21 bases and match criterion of 40–55% sequence identity is adequate for analysing genomes ranging from microbial to human. However, the optimal use of the FACS method should not use a constant K-mer size, but adapt it according to the size of the reference, as was the case for the experimental metagenome dataset in this study. Ultimately, the choice of match criterion will depend on the desired K-mer size, reference size and the application for which the method is being used. Furthermore, it was also demonstrated that the FACS cut-off, although low in strict sequence similarity, is stringent and performs equally well as the match cut-off used with BLAT and SSAHA2. This is an outcome of the different algorithms that make up each method. The match cut-offs were chosen based on their effect on the sensitivity and specificity of each method when trained on the synthetic metagenome dataset. This was conducted in an effort to find the best match cut-off possible for each method and reduce the risk of bias.

The results for both the synthetic MetaSim dataset and the experimental metagenome dataset, when using the human mitochondrial reference, showed relatively few unique reads for each method. This is due to the reasonably well-behaved simulated reads and small reference genomes making it relatively easy to analyse. Conversely, when using the human genome as a reference for the experimental metagenome dataset, the number of unique reads classified by each method increased substantially. This change reflects the complexity of the human genome and a certain bias of each method. Of the reads unique to BLAT/11occ and SSAHA2/skip2, ∼49% were shorter than 61 bases. This explains some of the differences between the FACS, BLAT and SSAHA2 methods, since FACS did not consider reads shorter than 61 bases in this study. Some low-complexity reads will not be considered by BLAT or SSAHA2, while FACS does not have any low-complexity filter. However, both SSAHA2 and BLAT classifies more low-complexity reads than FACS. It was interesting that FACS was so insensitive to low-complexity reads even though it does not have any low-complexity filter. Furthermore, classifying low-complexity reads with FACS does not take any additional time compared to an ordinary sequence, unlike BLAT that uses a binary help file 11occ to avoid analysing low-complexity reads and SSAHA2 which ignores K-mers that are abundant in the genome, in order to increase speed. Since the reference genomes in the synthetic metagenome dataset were not repeat-masked before MetaSim sampled them, ∼6000 sequences consisted mostly of N:s (uncalled bases) from the genome assemblies. FACS will try to classify these sequences but they were excluded from the analysis for BLAT and SSAHA2 since neither method will try to align them.

That so many unique reads are found using each method leads to further questions: how many methods are needed for complete classification? How stringent must match criteria be to make certain that the classified reads belong to the reference sequence, while keeping the fraction of false negatives low?

A sequence similarity of 45% with an alignment spanning over at least 45% of the query was chosen as a match criterion when using the MEGABLAST. This was done in an effort to minimize any potential bias of a high alignment length condition or an E-value as the match criterion. Only uniquely classified reads from the true dataset and suspected false positives from the synthetic dataset were verified with MEGABLAST due to the slow processing of this algorithm, making it a very time-consuming task to verify all classified sequences.

This study used no Bloom filters >312 MB, due to an observation that the filters became unspecific if they were larger than this size. Hence, the human genome had to be split up into individual chromosomes and chromosomes that would generate Bloom filters >312 MB were split into two before the Bloom filters were created. There is theoretically no reason why larger filters cannot be used. The look-up time is independent of the number of elements in the filter, thus using larger and fewer filters should increase the classification speed substantially. There are a number of improvements that could be made to make the classification of reads even faster including: implementing FACS in a compiled language such as C++, using larger and fewer filters, optimizing the scoring system and using a specifically designed filter for classifications.

In conclusion, this is the first exploration of Bloom filters for fast and accurate DNA sequence classification from metagenome datasets using the novel algorithm FACS. It was shown that FACS is the fastest method, with similar accuracy and sensitivity as the BLAT or SSAHA2 methods. This method is suitable for a number of specialized tasks, such as the removal of already known sequences from metagenome datasets before in-depth analysis of the remaining sequences, as used in this study. Another application is the relative quantification of bacterial species in a microbial community, such as the human respiratory tract. A related algorithm based on Bloom filters has also been used on sequence data to detect and calculate the frequency of induced sun mutations in human skin (Stranneheim,S. et al. submitted for publication).

The FACS method is faster and with similar accuracy as BLAT and SSAHA2, making it suitable for a number of other applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dmitriy Ryaboy and Peter Alvaro for creating the Bloom::Faster module, without their Perl module this study would not have been possible. We would also like to thank Daniel Klevebring and Magnus Bjursell for technical support and input and the technical staff at the Royal Institute of Technology responsible for the 454-FLX.

Funding: Swedish Research Council (grant number 2006-6022).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Allander T, et al. A virus discovery method incorporating DNase treatment and its application to the identification of two bovine parvovirus species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:11609–11614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211424698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allander T, et al. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BH. Space/time trade-offs in hash coding with allowable errors. Commun. ACM. 1970;13:422–426. [Google Scholar]

- Broder A, Mitzenmacher M. Network applications of Bloom filters: a survey. Internet Mathemathics. 2004;1:485–509. [Google Scholar]

- Down TA, et al. A Bayesian deconvolution strategy for immunoprecipitation-based DNA methylome analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:779–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley TJ, et al. DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature. 2008;456:66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. 2008a;18:1851–1858. doi: 10.1101/gr.078212.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, et al. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008b;24:713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M, et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning Z, et al. SSAHA: a fast search method for large DNA databases. Genome Res. 2001;11:1725–1729. doi: 10.1101/gr.194201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DC, et al. MetaSim: a sequencing simulator for genomics and metagenomics. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumble SM, et al. SHRiMP: accurate mapping of short color-space reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch DB, et al. The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: northwest Atlantic through eastern tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e77. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, et al. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J. Comput. Biol. 2000;7:203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.