Abstract

Summary: RNA loop regions are essential structural elements of RNA molecules influencing both their structural and functional properties. We developed RLooM, a web application for homology-based modeling of RNA loops utilizing template structures extracted from the PDB. RLooM allows the insertion and replacement of loop structures of a desired sequence into an existing RNA structure. Furthermore, a comprehensive database of loops in RNA structures can be accessed through the web interface.

Availability and Implementation: The application was implemented in Python, MySQL and Apache. A web interface to the database and loop modeling application is freely available at http://rloom.mpimp-golm.mpg.de

Contact: schudoma@mpimp-golm.mpg.de; may@mpimp-golm.mpg.de; walther@mpimp-golm.mpg.de

1 INTRODUCTION

Loop structures (i.e. regions without secondary structure) are not only essential structural elements accounting for the flexibility and structural diversity of RNA molecules. They are also important functional elements. For example, they frequently represent the site at which ligands are bound to the RNA molecule. The lack of canonical base pair formation in these regions makes them accessible for intra- (e.g. tertiary structure contact formation) and intermolecular contacts (e.g. binding of small molecules or other biomolecules). The disparity between the number of available RNA sequences on the one side and experimentally verified 3D structures on the other calls for an application of computational structure modeling to bridge this gap. Recently, we reported results from a comprehensive survey of RNA loop structures and established the basis for the application of homology modeling to RNA loops(Schudoma et al., 2010). Sequence-similar loops were found to fold into very similar structures. As a critical sequence identity threshold beyond which this relationship no longer holds, 25% sequence identity was determined. Here, we present a web-based application for RNA loop structure modeling utilizing available structures extracted from the Protein Data Bank (PDB; Berman et al., 2000). In contrast to the existing RNA 3D structure modeling applications [MC-Sym/MC-Fold (Parisien and Major, 2008), NAST/C2S (Jonikas et al., 2009) and FARNA (Das and Baker, 2007)] and RNA 3D structure databases [RNAjunction (Bindewald et al., 2008), FRABASE (Popenda et al., 2008) and SCOR (Tamura et al., 2004)], our approach is specifically tailored to the application to RNA loop structures.

2 TEMPLATE LIBRARY GENERATION

We extracted loop structures [hairpins, internal loops, multiloops and (single-stranded) segments] from 1371 RNA structures in the PDB (December 2008) using secondary structure information obtained from MC-Annotate base pair annotations (Gendron et al., 2001). Segments comprise bulges as well as the individual strands of internal loops and multiloops. The extraction followed these extraction rules: (i) Stems are regions of two or more continuous canonical base pairs (including GU/UG wobble pairs). (ii) Single base pairs and stacked base pairs inducing pseudoknots are not considered to be part of the secondary structure. (iii) Segments and hairpins include one additional anchor residue on either side. For hairpin loops, this corresponds to the closing base pair of their preceding stem. These anchors allow for the matching and insertion of a loop into a specified target site. (iv) Internal loops are composed of 1–2 (with the former case representing bulges) segments. Multiloops contain a number of individual strands less or equal to their number of branching stems. We clustered the raw loop datasets by sequence length, structural similarity [as given by the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the superpositions of their reduced backbone atoms (P, O5′, C5′, C4′, C3′, O3′)], and optionally, sequence identity. Using a range (0.5 Å–3.0 Å) of incremental (0.5 Å) cutoffs, we generated eight clustered sets of template loop structures of different degrees of sequence and structural redundancy.

3 TEMPLATE LIBRARY CONTENT AND DATABASE USAGE

The database contains 13 085 hairpin loops, 46 361 single-stranded segments, 17 133 internal loops and 5756 multi-loops. For each loop, we provide information on intra-loop base pairs, sugar pucker, and base stackings as well as a visualization both as 3D structure model [using Jmol (http://www.jmol.org/)] and contact graph. Entries for structural clusters include the cluster representative structure, as well as a consensus sequence, and a list of the structures belonging to the cluster. Aside from browsing, the database can be queried by sequence (including wildcard searches or matchings with errors) or base pair patterns in MC-Search format.

4 LOOP MODELING

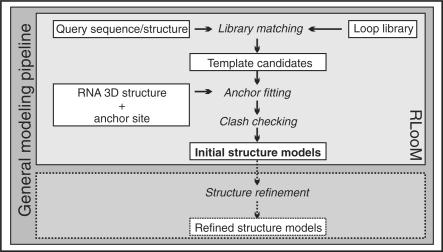

We adapted the protein loop modeling method of loops in proteins (Michalsky et al., 2003) for RNA loops. The method finds the loop templates that agree with a given query sequence and fit best into a target site of a given RNA structure. The target site is specified by a number of nucleotide positions (anchors) that depends on the loop type [cf. Section 2 (3)]. Modeling queries are dispatched in a simple XML-like structured modeling script language – RLooM Modeling Language (RLML, cf. RLooM Online Help). The modeling workflow is depicted in Figure 1. The user submits an RNA 3D structure in PDB format (e.g. a crystal structure or a generated structural model) and specifies a target loop sequence and a target site (two or more anchors depending on loop type) for the loop to be fitted into. Additionally, a query sequence or structure [base pair pattern in MC-Search format (http://major.iric.ca)] for selecting suitable loop candidates is required. An initial candidate set is generated by matching the query sequence against the selected template library (cf. Section 2). Next, each candidate loop is inserted into the target site by computing the optimal superposition of the anchors of candidate loop and target site utilizing the algorithm by Kabsch (1978). The candidate loop is rotated according to the rotation matrix associated with the optimal superposition and translated into the target site. As a quality measure, we compute RMSDa, the RMSD between the anchors after optimal superposition. Fitted candidate loops with RMSDa > 5.0 Å are automatically rejected, since they likely require a substantial change in their backbone conformation to fit into the target site. The whole construct is then checked for steric clashes (defined as atomic distances of <4.0 Å) with any surrounding atom. The server returns the 10 best model structures (with minimum RMSDa) for download. These models should be subjected to an external refinement routine in order to correct geometric inconsistencies resulting from the loop fitting.

Fig. 1.

RNA loop modeling workflow. White boxes highlight initial, intermediate and final data used in or created during the modeling process. Subroutines are given in italics.

5 CONCLUSION

We reported RLooM, a structure modeling web server for RNA loop modeling based on sequence homology and geometric constraints dictated by the site of insertion via anchor nucleotides. The server uses loop templates extracted from experimentally verified structures in the PDB. A performed benchmark (Schudoma et al., 2010) showed that homology modeling approach as implemented in RLooM yielded more accurate structural predictions than an ab initio-based modeling server [the iFoldRNA webserver (Sharma et al., 2008)] for target sequences with available sequence-similar template structures. For nine selected examples covering various loop sizes and types, our homology-based approach yielded significantly better results as judged by RMSD than obtained by using iFoldRNA [cf. Schudoma et al. (2010) Supplementary Table 1]. Evidently, for target loop sequences with no suitable structural example in the database, no prediction can be made. However, with the structural database steadily growing, this modeling gap is expected to shrink substantially over the coming years. RLooM was designed to harness the wealth of structural information already available for applications in RNA modeling. RLooM is expected to find many applications in RNA engineering and design.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Lothar Willmitzer for support and Frank Cordes for fruitful discussions during the early stages of the RNA loop modeling project.

Funding: German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (GoFORSYS Grant number 0313924 to P.M. and D.W.). Funding for open access charge: The Max Planck Society.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Berman HM, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindewald E, et al. RNAJunction: a database of RNA junctions and kissing loops for three-dimensional structural analysis and nanodesign. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D392–D397. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R, Baker D. Automated de novo prediction of native-like RNA tertiary structures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14664–14669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron P, et al. Quantitative analysis of nucleic acid three-dimensional structures. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;308:919–936. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonikas MA, et al. Coarse-grained modeling of large RNA molecules with knowledge-based potentials and structural filters. RNA. 2009;15:189–199. doi: 10.1261/rna.1270809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. A solution for the best rotation to relate two sets of vectors. Acta Cryst. 1978;A32:922–923. [Google Scholar]

- Michalsky E, et al. Loops In Proteins (LIP)–a comprehensive loop database for homology modelling. Protein Eng. 2003;16:979–985. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisien M, Major F. The MC-Fold and MC-Sym pipeline infers RNA structure from sequence data. Nature. 2008;452:51–55. doi: 10.1038/nature06684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popenda M, et al. RNA FRABASE version 1.0: an engine with a database to search for the three-dimensional fragments within RNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D386–D391. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schudoma C, et al. Sequence-structure relationships in RNA loops: establishing the basis for loop homology modeling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:970–980. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, et al. iFoldRNA: three-dimensional RNA structure prediction and folding. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1951–1952. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, et al. SCOR: Structural Classification of RNA, version 2.0. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D182–D184. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]