Abstract

Motivation: Lysine acetylation is a post-translational protein modification and a primary regulatory mechanism that controls many cell signaling processes. Lysine acetylation sites are recognized by acetyltransferases and deacetylases through sequence patterns (motifs). Recently, we used high-resolution mass spectrometry to identify 3600 lysine acetylation sites on 1750 human proteins covering most of the previously annotated sites and providing the most comprehensive acetylome so far. This dataset should provide an excellent source to train support vector machines (SVMs) allowing the high accuracy in silico prediction of acetylated lysine residues.

Results: We developed a SVM to predict acetylated residues. The precision of our acetylation site predictor is 78% at 78% recall on input data containing equal numbers of modified and non-modified residues.

Availability: The online predictor is available at http://www.phosida.com

Contact: mmann@biochem.mpg.de

1 INTRODUCTION

Post-translational protein modification (PTM) is a fundamental regulatory mechanism that controls many cell signaling processes (Cohen, 2001; Hunter, 2000). Lysine acetylation is a reversible PTM with a well known role in regulating gene expression through the modification of core histone tails. Individual reports have shown that lysine acetylation is also involved in other diverse biological processes suggesting a broader regulatory function. However, technological limitations have prevented a global analysis of lysine acetylation until recently.

Our study on the human in vivo acetylome provided a global picture of lysine acetylation (Choudhary et al., 2009). We used high-resolution mass spectrometry to identify 3600 lysine acetylation sites on 1750 proteins and found that lysine acetylation targets large macromolecular complexes that are involved in diverse cellular processes predominantly in the nucleus but also in the cytoplasm. Consensus sequence analysis revealed stringent constraints on the local sequence context around the acetylation sites. For example, amino acids with a bulky side chain were enriched in the −2 and +1 positions, which is in agreement with the frequent occurrence of acetylated lysines in ordered regions of proteins. In contrast, positively charged amino acids were almost completely excluded from the −1 position. These observations suggest that such patterns in the primary sequence may allow the differentiation between acetylated and non-acetylated lysines as a basis for in silico prediction.

Various algorithms have already been applied to the prediction of other post-translational modifications. For example, for the prediction of phosphorylation events Netphos uses neural networks (Blom et al., 1999), whereas Scansite employs a profile method (Obenauer et al., 2003). In previous studies, we constructed species-specific phosphorylation site predictors on the basis of support vector machines (SVM) (Gnad et al., 2007; Zielinska et al., 2009). These SVM-based predictors are part of the analysis toolkit of the PHOSIDA database (Gnad et al., 2007).

The basic idea of SVMs is to transform observed features of a given instance into a vector-based feature space (Noble, 2006). Each dimension of this feature space reflects a certain attribute. After the transformation of positive (e.g. acetylated lysines) and negative instances (e.g. non-acetylated lysines) into the vector space, a ‘maximum margin hyperplane’ that separates the two datasets is created. Here, the feature space is the sequence context of the acetylation site. For the classification of a new instance—in this case the sequence to be analyzed for possible acetylation—it has to be transformed into the feature space and categorized depending on the vector localization relating to the separating hyperplane.

We took advantage of the large number of in vivo acetylation sites from our human dataset (Choudhary et al., 2009) to create the first high-accuracy acetylation site predictor and make it publicly available via PHOSIDA.

2 METHODS

To train and test the acetylation site predictor, we used 3417 in vivo acetylation sites with their surrounding sequences as the positive set. To create a negative set of the same size, we randomly selected 3417 lysines from identified human peptides that have not been found to be acetylated according to the MAPU database (Gnad et al., 2009).

Initially, we randomly split the dataset into a training set (70%) and a test set (30%). Consequently our training set contained 4784 samples (2392 positive and 2392 negative instances), while the test set contained 2030 samples (1015 positive and 1015 negative instances). To select the model, we investigated several common kernel functions [Gaussian radial basis function (RBF), linear, polynomial and sigmoid] and trained the SVM on the basis of two to eight amino acids surrounding the site to the N- and C-terminus as described (Gnad et al., 2007). Each dimension is defined by the position within the surrounding region and the amino acid type. The possible values in each dimension are 0 and 1. Initially, for a given sequence all dimensions have value 0. Each amino acid type is encoded by an integer N ranging from 1 to 20 and the corresponding dimension (i*20 + N) has the value 1 if the amino acid is in position i relative to the site.

A few sites out of the negative set may turn out to be acetylation sites in future experiments. This problem was addressed by optimizing the ‘C parameter’ of the SVM, which controls the softness of the margin. For each kernel and for each surrounding sequence length, we optimized the parameters C and γ by varying them from 2−10 to 210 in multiplicative steps of two and chose the best combination of both parameters out of the 21 × 21 possibilities. For the polynomial function, we optimized d by varying from 1 to 10. The optimization was based on a 10-fold cross-validation on the training set. The kernel functions are as follows (u and v present feature vectors):

|

Having selected the best performing kernel function and surrounding sequence size, the accuracy of the optimal model was finally determined by using the test set.

The SVMs were implemented using the C# programming language. The acetylation predictor is available online via the PHOSIDA database (http://www.phosida.com). It enables web users to predict acetylation sites within any input protein sequence using a specified precision–recall cutoff. PHOSIDA lists predicted acetylated sites along with the true-positive rate that corresponds to the resulting score.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

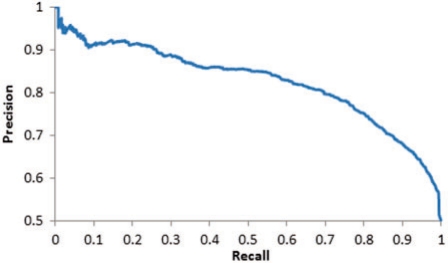

The 10-fold cross-validation-based training showed that the RBF function (with C = 1, γ = 0.25) along with input sets that comprise the site with four amino acids to both termini was the most powerful model. Notably, the precision–recall curves did not yield appreciably higher accuracies for larger window sizes. The corresponding precision–recall curve is shown in Figure 1. On the test set, at the score cutoff yielding 77% precision and 77% recall in the training set, the predictor generated 78% true positives and 78% true negatives, verifying the expected performance.

Fig. 1.

Precision-recall curve for acetylation site prediction. The line presents the trade-off between false positives and false negatives.

We also applied our test set to the SVM-based acetylation predictor LysAcet (Li et al., 2009) and the clustering-based prediction method PredMod (Basu et al., 2009). These predictors achieved true-positive rates of 53 and 25%, and true-negative rates of 52 and 75%, respectively. The lower accuracies in comparison to our predictor are likely caused by the smaller input datasets used in developing them. PredMod, for example, was based on only 56 lysines of the major human core histones.

A comparison with the motif-based prediction of acetylation sites (Schwartz et al., 2009) also showed that our predictor yields higher specificities at any given sensitivity value, which might also result from the quality of our data. Schwartz et al. (2009) used acetylation sites whose accuracy is not easy to determine because they have not yet been published.

The good performance of our predictor indicates stringent sequence constraints on acetylation modification recognition patterns that are readily distinguished from the sequences surrounding unmodified lysines. In contrast, other PTMs including phosphorylation have less readily detectable primary sequence preferences.

Interestingly, our previous large-scale acetylation study showed relatively high overlap of the measured human acetylome in the three cell lines studied and the fact that it covered most of the in vivo sites described in the literature (Choudhary et al., 2009). This suggests that a substantial proportion of all acetylation sites was sampled. As mentioned above, our observation that acetylation sites can be predicted quite accurately implies relatively clear sequence constraints. It also suggests a limited number of possible acetylation sites, which apparently are already well sampled in vivo identification by high accuracy mass spectrometry.

However, there are sites that have not or cannot easily be detected via mass spectrometry and for these our predictor provides valuable information. It can also be applied to predict acetylated sites in proteins of species that are closely related to human and whose acetylome has not been measured so far.

In the case of phosphorylation, we have previously found that species-specific predictors improve accuracy for more distantly related organisms (Hilger et al., 2009). As more lysine acetylomes of other organisms are determined by high-resolution mass spectrometry, it will be interesting to see if our predictor is also capable to predict acetylation sites of other species or whether species-specific lysine acetylation predictors will be required.

Funding: German Research Foundation (DFG grant 1563) RECESS (partial).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Basu A, et al. Proteome-wide prediction of acetylation substrates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13785–13790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906801106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N, et al. Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:1351–1362. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary C, et al. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P. The role of protein phosphorylation in human health and disease. The Sir Hans Krebs Medal Lecture. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001;268:5001–5010. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnad F, et al. PHOSIDA (phosphorylation site database): management, structural and evolutionary investigation, and prediction of phosphosites. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R250. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnad F, et al. MAPU 2.0: high-accuracy proteomes mapped to genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D902–D906. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilger M, et al. Systems-wide analysis of a phosphatase knock-down by quantitative proteomics and phosphoproteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1908–1920. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800559-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. Signaling–2000 and beyond. Cell. 2000;100:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81688-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, et al. Improved prediction of lysine acetylation by support vector machines. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009;16:977–983. doi: 10.2174/092986609788923338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble WS. What is a support vector machine? Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1565–1567. doi: 10.1038/nbt1206-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obenauer JC, et al. Scansite 2.0: proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3635–3641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, et al. Predicting protein post-translational modifications using meta-analysis of proteome scale data sets. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:365–379. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800332-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinska DF, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans has a phosphoproteome atypical for metazoans that is enriched in developmental and sex determination proteins. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:4039–4049. doi: 10.1021/pr900384k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]