Abstract

Background

Little is known about the influence of parent-adolescent relationships and peer behavior on emotional distress and risky behaviors among Asian American adolescents; in particular, cross-cultural and longitudinal examinations are missing from the extant research.

Objectives

To test and compare a theoretic model examining the influence of family and peer factors on adolescent distress and risky behavior over time, using a nationally representative sample of Chinese, Filipino, and White adolescents.

Methods

Data was utilized from Waves I (1994) and II (1995)of the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health; the sample comprised 194 Chinese, 345 Filipino and 395 White adolescents and weighted to correct for design effects, yielding a nationally representative sample. Structural equation modeling was used to test the theoretic model for each ethnic group separately, followed by multiple group analyses.

Results

The measurement model was examined for each ethnic group, using both unweighted and weighted samples and were deemed equivalent across groups. Tests of the theoretic model by ethnicity revealed that for each group, family bonds have significant negative effects on emotional distress and risky behaviors. For Filipino and White youth, peer risky behaviors influenced risky behaviors. Multiple group analyses of the theoretic model indicated that the three ethnic groups did not differ significantly from one another.

Discussion

Findings suggest that family bonds and peer behavior exert significant influences on psychological and behavioral outcomes in Asian American youth and that these influences appear to be similar with White adolescents. Future research should be directed towards incorporating variables known to contribute to the impact of distress and risky behaviors in model testing, and validating findings from this study.

Keywords: adolescent health, Asian Americans, emotional distress, risky behaviors, structural equation modeling

An estimated 34% of adolescents in the United States experience depressive symptoms (Essau & Petermann, 1999). Twenty to 50% of depressed youths have two or more other emotionally distressed states, which include dysthymia, anxiety disorders, disruptive disorders, and substance use (Roberts, 2000). Threats to well-being and physical health, curtailed attainment of life goals, and suicide represent a few consequences of adolescent depression and involvement in risky behaviors (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992).

Individual, family, and environmental variables are known to play key roles in the mental health of White adolescents (Compas, Hinden, & Gerhardt, 1995; Kaslow, Deering, & Racusin, 1994). Much less is known, however, about the relation between these variables and emotional distress and risky behaviors in Asian American (AA) adolescents. Although researchers have consistently noted the lack of empirical data on factors associated with the well-being of AA adolescents over the past 20 years (Uba, 1994), systematic examination of family and environmental factors such as parent-adolescent relationships and peer relationships and their outcomes, particularly over time, are missing in the literature.

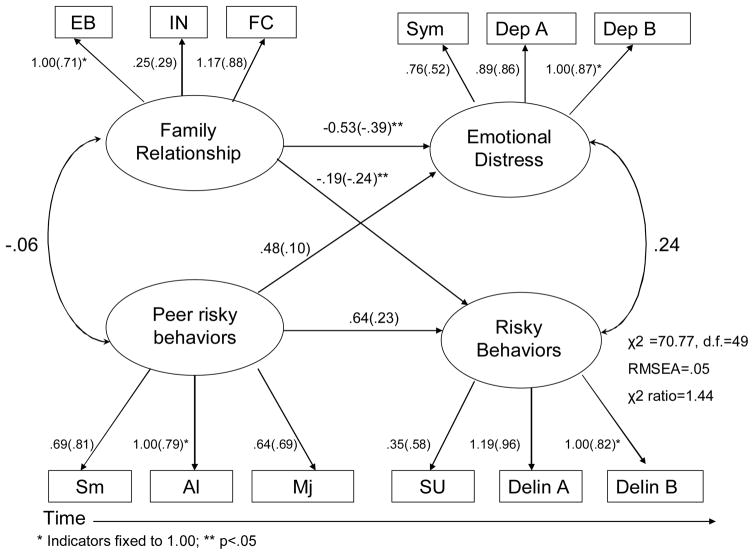

The purpose of this study was to begin to address these gaps by testing and comparing a theoretic model (Figure 1) positing the direction and valence of family and peer factors on emotional distress and risky behaviors across time among nationally representative samples of Chinese, Filipino, and White adolescents, using data drawn from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health (Add Health). The hypotheses in the proposed model are that across time (T1 to T2), (a) family bonds will predict decreased emotional distress and risky behaviors and (b) peer risky behaviors will predict increased adolescent risky behaviors.

Figure 1.

Heuristic Model of Family Bonds and Peer Risky Behaviors on Emotional Distress and Risky Behaviors

Background and Significance

Asian Americans

Chinese and Filipinos comprise the two largest Asian subgroups in the US, 2.4 and 1.8 million, respectively (United States Census, 2001). These two subgroups are quite distinct from one another, but the tendency to view all AAs as one group ignores critical social and cultural differences amongst them. Studies in which AA subgroups are distinguished from each other are limited by small sample sizes. Further, despite being the second largest Asian subgroup in the United States, there is little research on Filipino Americans. Without sufficient knowledge about subgroup differences, interventions aimed on addressing family and peer influences on adolescent well-being cannot be designed and tested adequately.

Family bonds and emotional distress in adolescence

Much of the existing literature points to the importance of emotional closeness between parent and child as a protective factor in mitigating against poor psychological and behavioral outcomes (Resnick et al., 1997; Romer, 2003). Equally important is the closeness between parent and child that results from engaging in activities together. This form of instrumental bond fosters family togetherness, increases the likelihood of open communication, establishes routines, and serves as an indicator of family integration and stability (McCubbin, McCubbin, & Thompson, 1986; Resnick et al., 1997). Research indicates that strong family bonds have an inverse relation to depressive symptomatology in adolescents (Barber, 1997; Lewinsohn et al., 1994; Raja, McGee, & Stanton, 1992). However, only a few studies to examine these variables have been conducted with AAs and fewer still use longitudinal data or nationally representative samples (Chen, Roberts, & Aday, 1998; Fuligni, 1998; Greenberger & Chen, 1996).

Chiu, Feldman, and Rosenthal (1992) examined the perception of parental behavior and distress in Euro-American, Chinese American, and Chinese Australian adolescents. They found that Chinese American and Euro-American adolescents differed in their responses on parental involvement and control, but warmth had a consistent negative relation with distress and psychosomatic complaints across all ethnic groups. Similar findings were reported by Greenberger and Chen (1996), who found that Chinese and Korean adolescents felt less understood by their mothers and perceived less maternal warmth compared with their Euro-American peers. Parental warmth and low conflict were predictive of reduced depression among younger AA adolescents. Perceived parental relationships were associated more strongly with depressed mood than was a global measure of family cohesion, suggesting that examination of individual relationships within the family is essential in relation to AA adolescent depression.

In one of the few studies with Filipino adolescents, Fuligni (1998) explored the relation between beliefs and expectations about authority and autonomy and perceived conflict and cohesion with parents among Euro-American, Mexican, Filipino and Chinese adolescents 12–16 years old. Compared to Euro-Americans, Filipino students were less willing to openly disagree with their parents, and Chinese students had delayed expectations for autonomy. Longitudinal analyses indicated that adolescents were more willing to disagree with their parents over time, regardless of ethnicity.

Family relationships and risky behaviors in adolescence

The relation between family variables and risky behavior has not been well-examined in AA adolescents, although positive family relationships (e.g. support) have been shown to be protective factors in drug and alcohol use (Jessor, van den Bos, Vanderryn, & Costa, 1995; Resnick, Harris, & Blum, 1993; Viner et al., 2006). Chen et al. (1998) found no difference in the level and types of misconduct reported by Euro-American, Chinese American, and Chinese (residing in China) youth, despite lower levels of parental warmth and monitoring among Chinese Americans compared with their Euro-American counterparts. However, family relationships and peer sanctions accounted for 62% of the variance in the resultant model of misconduct for Chinese Americans, highlighting the importance of family and peer relationships in this group. Analyses of large data sets further confirm that family factors are associated strongly with delinquent behavior (Duncan, Boisjoly, & Harris, 2001), but the patterns of associations between family bonds and risky behaviors may vary by specific risk behavior and by ethnicity (Viner et al., 2006).

Peer risky behaviors and risky behaviors in adolescence

In a number of studies with non-Asian samples, the relation between peer processes in risky behaviors has been documented; peer nonparticipation in risky behaviors is related to greater well-being and fewer conduct problems in adolescence (Costa, Jessor, & Turbin, 1999; Donovan, Jessor, & Costa, 1999; Eggert, Thompson, Herting, & Randell, 2001). In contrast, some research suggests that peer variables are not correlated strongly with delinquent behaviors (Duncan et al., 2001). With the exception of Chen et al. (1998), who reported that peer sanctions of misconduct were correlated with misconduct in Chinese American adolescents, the relation between peer risky behaviors and risky behaviors among AA adolescents has not been examined. This is particularly salient for prevention research, because it is well-established that the patterns of peer influence on adolescent risky behaviors are not uniform (Stanton & Burns, 2003).

In summary, studies on psychological and behavioral outcomes among AA adolescents are extremely limited and almost nonexistent in nursing; research on the differences between AA subgroups is also insufficient. Of particular concern is the lack of research with Filipino adolescents, which precludes any conclusions on the well-being and behaviors of this population. Comparative analysis between Chinese and Filipino adolescents and the extent to which family and peer influences are similar or different is fundamental to identifying the unique processes within each subgroup, which would have implications on the design and implementation of efficacious interventions.

Theoretical Framework

This study was guided by the ecological theory of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986). Bronfenbrenner (1979) posits that individual development is a function of the interaction of multiple ecological systems. Adolescent development must be viewed within the context of the family, sociocultural, and physical environments. Research indicates that the family system, parent-child interactions, and peer relationships play a key role in mediating or buffering against poor psychological outcomes (Birmaher, Ryan, Williamson, Brent, & Kaufman, 1996; Ge, Conger, Lorenz, Shanahan, & Elder, 1994) and that adolescents thrive developmentally in family environments characterized by close parent-adolescent bonds (Steinberg, 2000).

Methods

Study Overview, Design, and Procedures

Data from Wave 1 and Wave 2 of the Add Health project collected in 1994 (Wave 1) and 1995 (Wave 2; Udry, 2003) was utilized in this study. Add Health is an ecologically framed, nationally representative study of individual, family, and environmental influences on various aspects of health, including mental health and substance use. The primary sampling frame for this study included all high schools in the US that had an 11th grade and at least 30 students in the school (n = 26,666). A random sample of 80 high schools were selected and stratified by region, urbanicity, school type, and size. The largest feeder school, either a middle or junior high school, for each of the 80 high schools was recruited, resulting in 80 high schools and 52 feeder schools. A random subsample of adolescents in grades 7–12 from these schools participated in an in-home interview (n = 12,118) which included questions on health status, behaviors, peer networks, and family dynamics (Harris et al., 2003).

Self-identified Chinese, Filipino, and White adolescents who completed the in-home interviews together with their parents during the two time points were included in this longitudinal study. Consent to use this dataset was obtained from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) under the contractual agreement held by Dr. Willgerodt of the University of Washington and reviewed by the Human Subjects Divisions of both UNC-CH and the University of Washington.

Sample

The sample for this study (Table 1) was composed of 194 Chinese, 335 Filipino, and 345 randomly selected White adolescents. All of the Chinese and Filipino cases with complete data were included; however, because of the large number of White cases available, a subsample of 345 cases was selected randomly, allowing the three study group sizes to remain relatively similar in size. In the analyses, weights were incorporated to adjust for study design effects to ensure that results are nationally representative with unbiased estimates (Chantala & Tabor, 1999). With the design weights, the study samples represented 77,775 Chinese, 178,503 Filipino, and 503,493 White youth.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics by Ethnicity

| Chinese (n = 194) | Filipino (n = 335) | White (n = 345) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |||

| Range | 13–19 | 12–20 | 12–21 |

| Mean (SD) | 15.7 (1.40) | 16.7 (1.35) | 15.6 (1.53) |

| Income (in thousands of dollars) | |||

| Range | 2–600 | 0–450 | 0–999 |

| Mean (SD) | 67.60 (73.18) | 46.83 (30.24) | 55.51 (87.76) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 107 (54%) | 180 (54%) | 155 (45%) |

| Female | 87 (46%) | 155 (46%) | 190 (55%) |

Measurement

Examined were the influences of family and peers over time on adolescent risk behaviors; data on family bonds and peer risky behaviors were utilized from the Wave 1 data collected in 1994, and emotional distress and risky behaviors were examined from Wave 2, collected 1 year later.

Family bonds

The concept of family bonds was defined in terms of emotional bonds, instrumental bonds, and family closeness (Table 2). Emotional bonds was the adolescent’s perception of encouragement, emotional availability, and closeness with their mother. Responses were summed to create a total score; higher scores reflected a higher degree of maternal support. Instrumental bonds was the frequency with which the adolescent engaged in activities with their mother. Answers were summed to create a total score; higher scores reflect engaging in more activities. Family closeness referred to the extent to which the adolescent feels the family is close and attentive to one another; a summed score was a marker of family closeness, and higher scores reflected higher levels of family closeness.

Table 2.

Measurement of Study Variables

| Variable | Sample Items | Range | Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Bonds | |||

| Emotional Bonds (6 items) | “Most of the time your mother is warm and loving to you” | 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) | .82–.87 |

| Instrumental Bonds (10 items) | “Have you gone shopping with your mother in the past 4 weeks’ | 0 (no), 1(yes) | N/A |

| Family Closeness (4 items) | “Your family pays attention to you” | 1(not at all) to 5 (very much) | .74–.77 |

| Peer Risky Behaviors | |||

| Smoking (1 item) | “How many of your 3 best friends smoke cigarettes at least once a month?” | 0 to 3 | |

| Alcohol (1 item) | “How many of your 3 best friends drink alcohol at least once a month?” | 0 to 3 | .75–.80 |

| Marijuana (1 item) | “How many of your 3 best friends smoke marijuana at least once a month?” | 0 to 3 | |

| Emotional Distress | |||

| Depression (19 items) | “How often have you felt sad” | 0 (never) to 3 (most of the time) | .86–.88 |

| Symptoms (14 items) | “How often do you have trouble falling asleep?” | 0 (never) to 4 (every day) | .78–82 |

| Risky Behaviors | |||

| Substance Use (6 items) | “Have you ever tried smoking?” | 0 (no), 1 (yes) | N/A |

| Delinquency (15 items) | “How many times have you painted graffiti?” | 0 (never) to 3 (5 or more times) | .79–.81 |

Peer risky behavior

Peer risky behavior was measured using 3 items: how many of their three best friends drink alcohol without parental supervision, smoke cigarettes, or smoke marijuana at least once a month. Responses were summed so that higher scores reflect higher levels of peer engagement in risky behaviors.

Emotional distress

Emotional distress was defined broadly, using items relating to depressive and somatic symptoms from Wave 2. Depression was measured with 19 items in the Feelings Scale, which is a modified version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Because adolescents often express emotional distress in terms of physical complaints, somatic symptoms were included and assessed using the frequency of symptoms over the past 12 months. Responses were summed so that higher scores indicated higher levels of emotional distress.

Risky behaviors

Substance use and delinquency were considered risky behaviors for this study. Substance use was defined to include smoking; drinking alcohol without parental supervision; or using marijuana, cocaine, inhalants, or other illegal drugs. Responses were summed to determine the number of substances an individual had tried. Delinquency was indexed using a 14-item scale to ask if a respondent had engaged in delinquent activities.

Data Analysis

Missing data

Complete datasets are required to conduct complex survey design estimation procedures (LISREL 8.8 for Windows, 2007). The proportion of missing data for family income was high (30%). To avoid unnecessary loss of cases in the analyses, regression imputations were used to replace the missing data (Allison, 2002; Little, 1992) prior to structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses. Correlations between all the variables in the study were examined for each ethnic group to identify variables that were correlated with income. Stepwise regression analyses were conducted, incorporating variables significantly correlated with income to estimate missing values. The remaining cases with missing data (<1%) were removed from the data set, resulting in the final sample size noted above.

Structural equation modeling

In SEM, the covariance structure is used to model the relations among several variables, including observed and latent variables. In SEM, two types of models are examined. Confirmatory factor analysis is used to evaluate the fit of the measurement model to the empirical data. Once the measurement model is specified, tests of the structural or theoretic model are conducted to examine the hypothesized effects of the latent variables on one or more outcome variables. Data in this study were weighted to correct for study design effects to ensure that results are nationally representative (Chantala & Tabor, 1999). With weighted data, complex survey design estimation procedures are employed, using full information maximum likelihood estimation, which is robust to violations of normal distribution. Many of the goodness-of-fit indices typically used to evaluate structural equation models, however, are not provided in complex survey design analyses; in these weighted analyses, the full information maximum likelihood chi-square, p-value, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) are provided to evaluate the fit the theoretic model.

In this study, measurement and theoretic models were examined separately for each ethnic group. Also, the data represented two points in time, thus the measurement models for each ethnic group were estimated within each time period. That is, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted for family bonds and peer risky behaviors at Time 1 (Wave 1) and for emotional distress and risky behaviors at Time 2 (Wave 2). Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypothesized effects of family bonds and peer risky behaviors on risky behaviors and emotional distress for each ethnic group; these tests were followed by multigroup analyses to compare model estimates across ethnic groups. Age and gender are known to be associated with the study outcomes, and were incorporated into the analyses as control variables. Parameter estimates were comparable in separate analyses conducted without these two variables. Thus, results are reported without the inclusion of age and gender; details of the analysis are presented with the results. The data were analyzed using LISREL 8.7 (Jöreskog, & Sörbom, 2006).

Results

Descriptive statistics for the major variables are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, Range and Correlation Matrix of Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese n = 194 | |||||||||||||

| 1. Emotional Bonds | 1 | .27 | .63 | −.14 | −.15 | −.03 | −.37 | −.29 | −.30 | −.05 | −.03 | −.03 | |

| 2. Instrumental Bonds | 1 | .20 | −.05 | .01 | −.03 | −.08 | −.02 | −.13 | −.10 | −.08 | −.02 | ||

| 3. Family Closeness | 1 | −.07 | −.09 | −.04 | −.43 | −.41 | −.27 | −.27 | −.30 | −.25 | |||

| 4. Peers, Smoke | 1 | .48 | .56 | .07 | .07 | .08 | .43 | .01 | .11 | ||||

| 5. Peers, Alcohol | 1 | .55 | .07 | .12 | .01 | .56 | .16 | .24 | |||||

| 6. Peers, Marijuana | 1 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .52 | .18 | .27 | ||||||

| 7. Depression A | 1 | .77 | .51 | .14 | .20 | .22 | |||||||

| 8. Depression B | 1 | .57 | .13 | .22 | .19 | ||||||||

| 9. Symptoms | 1 | .17 | .15 | .10 | |||||||||

| 10. Substance Use | 1 | .52 | .52 | ||||||||||

| 11. Delinquency A | 1 | .77 | |||||||||||

| 12. Delinquency B | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 25.60 | 3.66 | 15.54 | .28 | .51 | .25 | .57 | 1.41 | 1.12 | 5.34 | 5.53 | 10.63 | |

| SD | 3.78 | 1.94 | 2.62 | .63 | .84 | .65 | 1.00 | 2.11 | 2.01 | 3.34 | 4.03 | 5.17 | |

| Range | 13–30 | 0–8 | 7–20 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–5 | 0–15 | 0–13 | 0–16 | 0–19 | 1–29 | |

| Filipino n = 335 | |||||||||||||

| 1. Emotional Bonds | 1 | .30 | .54 | −.00 | −.04 | −.06 | −.20 | −.20 | −.22 | −.11 | −.04 | −.00 | |

| 2. Instrumental Bonds | 1 | .10 | −.04 | −.01 | −.12 | −.14 | −.08 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | −.01 | ||

| 3. Family Closeness | 1 | −.13 | −.08 | −.07 | −.23 | −.27 | −.23 | −.16 | −.12 | −.09 | |||

| 4. Peers, Smoke | 1 | .63 | .57 | .18 | .09 | .08 | .44 | .15 | .25 | ||||

| 5. Peers, Alcohol | 1 | .54 | .11 | .08 | .08 | .46 | .15 | .25 | |||||

| 6. Peers, Marijuana | 1 | .18 | .14 | .17 | .47 | .23 | .37 | ||||||

| 7. Depression A | 1 | .75 | .52 | .09 | .09 | .07 | |||||||

| 8. Depression B | 1 | .58 | .09 | .18 | .16 | ||||||||

| 9. Symptoms | 1 | .19 | .23 | .18 | |||||||||

| 10. Substance Use | 1 | .34 | .47 | ||||||||||

| 11. Delinquency A | 1 | .75 | |||||||||||

| 12. Delinquency B | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 25.63 | 3.50 | 15.80 | .69 | .79 | .52 | 1.00 | 1.57 | 1.39 | 7.45 | 6.87 | 10.83 | |

| SD | 4.10 | 1.91 | 2.84 | 1.01 | 1.05 | .95 | 1.18 | 2.10 | 2.12 | 3.84 | 4.40 | 5.35 | |

| Range | 8–30 | 0–9 | 4–20 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–5 | 0–15 | 0–13 | 0–20 | 0–26 | 0–27 | |

| White n = 345 | |||||||||||||

| 1. Emotional Bonds | 1 | .20 | .62 | −.15 | −.16 | −.09 | −.29 | −.25 | −.23 | −.14 | −.22 | −.16 | |

| 2. Instrumental Bonds | 1 | .15 | −.04 | −.09 | −.05 | −.03 | −.08 | −.11 | −.13 | −.03 | −.01 | ||

| 3. Family Closeness | 1 | −.14 | −.20 | −.16 | −.26 | −.22 | −.19 | −.16 | −.22 | −.19 | |||

| 4. Peers, Smoke | 1 | .56 | .48 | .22 | .13 | .04 | .44 | .01 | .14 | ||||

| 5. Peers, Alcohol | 1 | .61 | .14 | .11 | .12 | .48 | .22 | .25 | |||||

| 6. Peers, Marijuana | 1 | .05 | .01 | .01 | .46 | .16 | .20 | ||||||

| 7. Depression A | 1 | .77 | .44 | .22 | .14 | .15 | |||||||

| 8. Depression B | 1 | .59 | .19 | .17 | .18 | ||||||||

| 9. Symptoms | 1 | .20 | .16 | .12 | |||||||||

| 10. Substance Use | 1 | .31 | .28 | ||||||||||

| 11. Delinquency A | 1 | .80 | |||||||||||

| 12. Delinquency B | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 26.24 | 4.00 | 16.12 | .88 | 1.13 | .58 | 1.31 | 1.42 | 1.47 | 5.44 | 5.25 | 12.06 | |

| SD | 3.48 | 1.96 | 2.56 | 1.12 | 1.21 | .97 | 1.27 | 2.07 | 2.26 | 3.80 | 4.23 | 6.22 | |

| Range | 18–30 | 0–10 | 6–20 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–3 | 0–5 | 0–18 | 0–21 | 0–25 | 0–25 | 1–37 | |

Measurement Model

The measurement model consisted of four latent variables: family bonds, peer risky behaviors, risky behaviors, and emotional distress (Table 4). Each was indexed with three indicators, standard in SEM. Emotional bonds (EB), instrumental bonds (IB), and family closeness (FC) were the three indicators used to measure family bonds. The three single indicators of risky behaviors included: the sum of substance use (SU) and the delinquency scale which was split randomly into 2 scales (Delinquency A and Delinquency B) to create three indicators for the latent variable. Similarly, emotional distress was indexed using: somatic symptoms (Symp) and two randomly split subscales of the CES-D (Depression A and Depression B), to create three indicators for emotional distress.

Table 4.

Measurement Model Factor Loadings of Observed Variables on Latent Variables for Chinese, Filipino and White Youth Using Weighted Sample

| Latent Variables | Observed Variables | Estimates (Standardized Estimates) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Filipino | White | ||

| χ2 = 72.10, df = 48, p < .05, RMSEA = .05 | χ2 = 72.96, df = 48 p < .05, RMSEA = .04 | χ2 = 90.68, df = 48, p < .05, RMSEA = .05 | ||

| Family Bonds | Emotional Bondsa | 1.00 (.73) | 1.00 (.76) | 1.00 (.87) |

| Instrumental Bonds | 0.25 (.31) | .12 (.20) | .11 (.18) | |

| Family Closeness | 1.13 (.87) | .79 (.87) | .65 (.78) | |

| Peer Risky Behaviors | Peers, Smoke | 0.69 (.81) | 0.85 (.81) | 0.75 (.69) |

| Peers, Alcohola | 1.00 (.79) | 1.00 (.84) | 1.00 (.86) | |

| Peers, Marijuana | 0.65 (.69) | 0.72 (.70) | 0.70 (.74) | |

| Emotional Distress | Depression_A | .89 (.86) | .83 (.82) | .70 (.76) |

| Depression_Ba | 1.00 (.87) | 1.00 (.94) | 1.00 (.95) | |

| Symptoms | .76 (.52) | .85 (.64) | .99 (.62) | |

| Risky behaviors | Substance Use | 0.35 (.58) | .37 (.55) | .19 (.30) |

| Delinquency A | 1.20 (.97) | 1.16 (.86) | 1.02 (.94) | |

| Delinquency Ba | 1.00 (.82) | 1.00 (.84) | 1.00 (.86) | |

Notes.

Indicator fixed to 1.00, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation

For each latent variable, the strongest indicator based on item-total correlation using reliability analysis was fixed to 1 to serve as the referent indicator. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the measurement model; the factor loadings for the indicators were generally adequate for each ethnic group (Table 4). Except for two indicators, all indicators loaded on their respective factor at .52 or greater; all loadings were statistically significant. Instrumental support proved to be a weak indicator, but retained to capture both the emotional and instrumental support that adolescents experience. A similar rationale was used to retain substance use in the risky behavior construct.

As mentioned above, the LISREL software does not calculate the typical series of model fit indices when estimating models using complex survey designs (those incorporating weights to ensure nationally representative data). To provide more information regarding model goodness-of-fit statistics, the models for each ethnic group were calculated first using unweighted data, and then recalculated using weighted data. Models estimated using the unweighted data provided approximations of model fit to assist in the interpretation of the weighted models. For the initial analysis using unweighted data for the Chinese, Filipino, and White samples, goodness-of-fit indices ranged from .98–.99, with values above 0.90 indicating good fit. The comparative-fit indexes ranged from .98–1.0, with values greater than 0.90 indicating good fit; and RMSEA ranged from .00–.08, with values less than .08 indicating an adequate fit. Based on these criteria, the overall fit of the models by ethnicity were judged to be good. The measurement models were estimated subsequently using data with survey design weights. Fit indices for models estimated using the weighted sample data were as follows. For Time 1, Chinese: χ2 = 2.3, df = 8, p = .97, RMSEA < .001; Filipino: χ2 = 14.55, df = 8, p = .07, RMSEA = .05; and White: χ2 = 4.09, df = 8, p = .85, RMSEA < .001, and for Time 2, Chinese: χ2 = 3.84, df = 8, p = .97, RMSEA < .001; Filipino: χ2 = 7.73, df = 8, p = .46, RMSEA < .001; and White: χ2 = 9.23, df = 8, p =.32, RMSEA = .02, fully consonant with results from the unweighted analysis described above. Also, the ratio of chi square to degrees of freedom for each model was less than 2.0, indicating a good fit (Byrne, 2001).

To determine if the measurement models were equivalent across ethnic groups, multigroup analyses were conducted, allowing the parameters for each of the three models to be estimated freely and then constraining the parameters to be equal across the three study groups, thereby testing a no difference model between groups. The chi-square difference test was used to evaluate for model differences between groups and were found to be nonsignificant (Chinese-Filipino: χ2diff = 1.29, dfdiff = 8; Chinese-White: χ2diff = 3.46, dfdiff = 8; Filpino-White: χ2diff = 4.96, dfdiff = 8), indicating that the measurement models were equivalent across groups (group invariant; Hoyle & Panter, 1995). In subsequent structural analyses of the theoretical models, the measurement component of the models was constrained to be equal across groups.

Theoretical Model

The posited theoretical model (Figure 1) was tested to examine if, across time, family bonds or peer risky behaviors directly influenced emotional distress and risky behaviors. Results for each ethnic group are presented first, followed by results of the multigroup analyses. As noted above, the survey design estimation procedures do not provide all the fit indices typically used in SEM. Therefore, the model was evaluated by examining three fit indices: the maximum likelihood chi-square statistic, RMSEA, and the chi-square ratio.

Tests of Theoretic Model by Ethnicity

Model fit and parameter estimates are summarized in Figures 2, 3, and 4 for each of the three study samples. Standardized coefficients are analyzed when examining parameter estimates within ethnic groups, while unstandardized coefficients are useful when examining between groups; thus, both are provided here. For Chinese youth, family bonds had direct, negative, and significant effects on emotional distress (b = −.53, β= −.39) and risky behaviors (b = −.19, β =−.24) across time. Similarly, among Filipinos, family bonds had significant negative effects on emotional distress (b = −.67, β = −.53) and risky behaviors (b = −.10, β = −.19). In addition for Filipino youth, across time, peer risky behaviors contributed to a significant increase in risky behaviors (b = .46, β = .25). Similar effects were noted among the White youth. Family bonds influenced emotional distress (b = −.37, β = −.31) and risky behaviors (b = −.18, β = −.30) and peer risky behaviors influenced increases in risky behaviors (b = .45, β = .23).

Figure 2.

Unstandardized (Standardized) Parameter Estimates from Structural Equation Analyses for Chinese

Figure 3.

Unstandardized (Standardized) Parameter Estimates from Structural Equation Analyses for Filipino

Figure 4.

Unstandardized (Standardized) Parameter Estimates from Structural Equation Analyses for Whites

Multigroup Analyses of Theoretic Model

Analyses were conducted to test if family bonds and peer risky behaviors had similar influences on emotional distress and risky behaviors among the three ethnic groups. First, a model was tested in which the paths between groups were constrained to be equal (fully constrained model). Second, an unconstrained model was tested in which paths were allowed to vary uniquely for each group. Chi-square difference tests were used to compare these two models and to evaluate if, in general, the paths predicted in the theoretic model differed across the groups. If the models differed, then additional chi-square difference tests were conducted. Models were tested by constraining one path at a time and comparing this model with the fully unconstrained model.

The multigroup analyses indicated that there were no differences between the constrained and unconstrained models among the Chinese and White youth and the Filipino and White youth (Table 5). Although differences were noted between the Chinese and Filipino youth, no significant differences were found when each path was analyzed against the unconstrained model.

Table 5.

Chinese, Filipino, and White Multigroup Analyses of Structural Models

| Groups | Model | ML χ2, Degrees of Freedom | RMSEA | χ2diff |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese-Filipino | ||||

| Model 1 | Theoretical paths fully constrained | 202.92 df = 108 |

.06 | |

| Model 2 | Paths unconstrained | 144.92* df = 104 |

.04 | 58 |

| Model 1A | Family and ED path free | 144.52 df = 105 |

.04 | NS |

| Model 1B | Family and RB path free | 142.67 df = 105 |

.04 | NS |

| Model 1C | PRB and ED path free | 144.28 df = 105 |

.04 | NS |

| Model 1D | PRB and RB path free | 145.32 df = 105 |

.04 | NS |

| Chinese-White | ||||

| Model 1 | Theoretic paths fully constrained | 159.52 df = 108 |

.04 | |

| Model 2 | Theoretic paths unconstrained | 162.87 df = 104 |

.05 | 3.35 NS |

| Filipino-White | ||||

| Fully constrained model | 165.20 df = 108 |

.04 | ||

| Unconstrained gammas | 167.85 df = 104 |

.04 | 2.65 NS |

|

Notes.

Significantly different from constrained models, p < .05, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation

Discussion

Tests of the theoretic model by ethnicity indicated that across time for all three ethnic groups, family bonds had a significant negative effect on emotional distress and risky behaviors over time. This is consistent with the family and adolescent literature supporting the notion that positive family bonds are protective in nature, particularly with respect to risky behaviors (Stanton & Burns, 2003). Also demonstrated was that for all three ethnic groups, family bonds exerted a stronger influence on emotional distress than they did on risky behaviors, which validates research pointing to the direct inverse relation between positive family relationships and emotional distress (Dornbusch, 1989; Steinberg, 2000).

Although the relations among family bonds, psychological well-being, and risky behaviors are consistent with research findings with other ethnic groups, the specific aspects of family relationships need more examination among Asian youth. The factor loadings for instrumental support were relatively weak but were retained as indicators of family bonds in order to maintain the theoretical distinction between emotional closeness and instrumental support. Further assessments are needed to determine if the weak loadings were the result of an inadequate measure of instrumental support or if the emotional support that an adolescent perceives from their parent and family are the critical elements of family bonds. In this initial examination, however, results suggest that the association between family bonds and psychological and behavioral outcomes over time in AA youth appear to be similar with White youth.

Peer risky behaviors significantly influenced emotional distress and risky behaviors among both Filipino and White adolescents. The same effects were not evident for Chinese youth. This attenuated effect of peer influence might be explained by stronger adherence to traditional Chinese family values. In Asian families, particularly in Chinese culture, children have been raised traditionally to accept that the needs of the family take precedence over the desires of the individual. Parents are expected to be obeyed and the behavior of the individuals reflects on the family as a whole (Uba, 1994). Because of this strong and enduring emphasis on maintaining familial honor, it is possible that adolescents close to their parents would subscribe closely to the same traditional Chinese values and that this would serve as a more powerful behavioral influence compared with peer behaviors. These effects might also be artifacts related to the small sample size and low variability in peer risky behaviors noted in the Chinese sample. Clearly further research is needed, particularly among Filipino youth, to understand the role of peers on adolescent behaviors.

Results from the multigroup analyses indicate that the effects of family bonds and peer behavior on emotional distress and risky behaviors are similar between all three ethnic groups. Although family bonds and peer behavior exerted significant influences on distress and risky behaviors in adolescents, these influences did not vary across subgroups. This finding was unexpected, particularly given the vast amount of literature that points to family relations as being uniquely important and a unique source of stress in adolescence in Asian cultures. Additionally, it is often hypothesized that, given the greater Westernization of the Philippines compared with China, Filipino adolescents might not adhere to the traditional Asian values with the same level of intensity as Chinese youth, thereby making Filipino adolescents more similar to White youth. Findings from this nationally representative longitudinal study, however, did not support either hypothesis. However, other research using these Add Health data indicated that mean differences in perceptions of family relationships and amount of risky behaviors and emotional distress differed by generation for Chinese and Filipino youth (Willgerodt & Thompson, 2005, 2006). Also, the influence of family on emotional distress and risky behaviors may vary by generational status; these hypotheses were not tested due to sample size. Findings from this study, however, point to the need to understand how different generations of Chinese and Filipino adolescents define and perceive different components of family bonds. Also underscored was the importance of research to compare ethnic groups to one another; unfortunately, much of the extant research focuses on single ethnic minority groups.

As noted earlier, age and gender, which may contribute to the impact of family and peers on risky behaviors and emotional distress, were examined in the analyses but did not contribute significantly to the findings. Further model testing should be directed towards incorporating other demographic variables known to contribute to these outcomes. Regardless, the lack of significant findings with respect to ethnicity highlight the necessity for more longitudinal comparative studies to understand the mechanisms and impact of family processes and peer behavior on adolescent well-being and behavior among different cultural groups.

Limitations

Although this study is the first of its kind, several limitations should be noted. First, while the constructs were created by selecting appropriate items, they nevertheless were constrained by the data that were available. Chinese and Filipino adolescents may define and experience aspects of family bonds in ways that are not captured in these indicators. Thus, the assessment of family support, closeness, and involvement is a fundamental consideration in future research with AA teens. Similarly, the measurement of peer risky behaviors captured only one facet of risk behaviors (substance use) and would need to be measured more comprehensively in future studies. Second, the relatively small sample size of Chinese youth and low variability of peer risky behaviors and risky behavior may account for the nonsignificant findings. Despite these limitations, however, this study provides nationally representative and longitudinal results which are timely and contribute to building an important foundation for future research with Asian American youth.

Conclusion

Understanding and articulating the protective and risk factors associated with adolescent psychological well-being and risky behaviors are important as the AA youth population grows. This study fills a void in existing research by testing a model empirically to predict the effects of family bonds and peer behavior on emotional distress and risky behaviors across time and conducting comparative analyses of these models between ethnic groups. Findings from this nationally representative longitudinal study provide an initial insight into the influence of family and peers on adolescent health over time among Chinese, Filipino, and White adolescents, yet comparative analyses suggest that ethnic differences do not exist in these influences. Further research should be directed towards determining how AA adolescents define and perceive family bonds, if they differ from other ethnic and cultural groups, and validating findings from this study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a career development award (NINR #K01 NR08334-02). This research was based on data from the Add Health project, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry (PI) and Peter Bearman, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to the Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Additional information on the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health can be obtained at http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/.

Thank you to Dr. Elaine Adams Thompson for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript and for her thoughtful comments and review.

References

- Allison PD. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Introduction: Adolescent socialization in context: Connection, regulation, and autonomy in multiple contexts. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12(2):173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J. Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Part II. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(12):1575–1583. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22(6):723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic Concept, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chantala K, Tabor J. National longitudinal study of adolescent health: Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the add-health data. 1999 Retrieved March 16, 2007, from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carolina Population Center Web site: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/files/weight1.pdf.

- Chen IG, Roberts RE, Aday LA. Ethnicity and adolescent depression: The case of Chinese Americans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186(10):623–630. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu ML, Feldman SS, Rosenthal DA. The influence of immigration on parental behavior and adolescent distress in Chinese families residing in two Western nations. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1992;2(3):205–239. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Hinden BR, Gerhardt CA. Adolescent development: Pathways and processes of risk and resilience. Annual Review of Psychology. 1995;46:265–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa FM, Jessor R, Turbin MS. Transition into adolescent problem drinking: The role of psychosocial risk and protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:480–490. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Adolescent problem drinking: Stability of psychosocial and behavioral correlates across a generation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(3):352–361. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM. The sociology of adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology. 1989;15:233–259. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Boisjoly J, Harris KM. Sibling, peer, neighbor, and schoolmate correlations as indicators of the importance of context for adolescent development. Demography. 2001;38(3):437–447. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert LL, Thompson EA, Herting JR, Randell BP. Reconnecting youth to prevent drug abuse, school dropout, and suicidal behaviors among high-risk youth. In: Wagner E, Waldron HB, editors. Innovations in adolescent substance abuse intervention. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science; 2001. pp. 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- Essau AC, Petermann F. Depressive disorders in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment. Northvale, NJ: Aronson; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. Authority, autonomy, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion: A study of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(4):782–792. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Shanahan M, Elder GH. Mutual influences in parent and adolescent psychological distress. Development Psychology. 1994;31(3):406–419. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C. Perceived family relationships and depressed mood in early and late adolescence: A comparison of European and Asian Americans. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(4):707–716. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Florey F, Tabor J, Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry R. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design. 2003 Retrieved from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Panter AT. Writing about structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 134–175. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, van den Bos J, Vanderryn J, Costa FM. Protective factors in adolescent problem behavior: Moderator effects and developmental change. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31(6):923–933. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL for Windows [Computer Software] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Deering CG, Racusin GR. Depressed children and their families. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14(1):39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Rohde P, Gotlib IH, Hops H. Adolescent psychopathology II: Psychosocial risk factors for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103(2):302–315. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LISREL 8.8 for Windows. WebHelp file. Computer software and online help manual. 2007 Retrieved August 6, 2007, from http://www.ssicentral.com/lisrel/WebHelp/index.htm.

- Little RJA. Regression with missing X’s: A review. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1992;87:1227–1237. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin H, McCubbin M, Thompson A. Family time and routines scale. In: McCubbin H, Thompson A, editors. Family assessment for research and practice. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, Madison; 1986. pp. 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general populations. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Raja N, McGee R, Stanton WR. Perceived attachments to parent and peers and psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1992;21(4):471–485. doi: 10.1007/BF01537898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blub RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Harris LJ, Blum RW. The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1993;29(Suppl 1):S3–S9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE. Depression and suicidal behavior among adolescents: The role of ethnicity. In: Cuellar I, Paniagua A, editors. Handbook of multicultural mental health: assessment and treatment of diverse populations. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 359–388. [Google Scholar]

- Romer D. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton BF, Burns J. Sustaining and broadening intervention effect. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Adolescence. 5. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Uba L. Asian Americans: Personality patterns, identity, and mental health. New York: The Guilford Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), Waves I & II, 1994–1996; Wave III, 2001–2002 [machine-readable data file and documentation] Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Profiles of general demographic characteristics: 2000 Census of population and housing. 2001 Available at www.census.gov/prod/cen2000/dp1/2khus.pdf.

- Viner RM, Haines MM, Head JA, Bhui KB, Taylor S, Stansfeld SA, et al. Variations in associations of health risk behaviors among ethnic minority early adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(1):55. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willgerodt MA, Thompson EA. The influence of ethnicity and generational status on parent and family relations among Chinese and Filipino adolescents. Public Health Nursing. 2005;22(6):460–471. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willgerodt MA, Thompson EA. Ethnic and generational influences on emotional distress and risk behaviors among Chinese and Filipino American adolescents. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006;29(4):311–324. doi: 10.1002/nur.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]