Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Unexplained abdominal pain in children has been shown to be related to parental responses to symptoms. This randomized controlled trial tested the efficacy of an intervention designed to improve outcomes in idiopathic childhood abdominal pain by altering parental responses to pain and children's ways of coping and thinking about their symptoms.

METHODS

Two hundred children with persistent functional abdominal pain and their parents were randomly assigned to one of two conditions—a three-session intervention of cognitive-behavioral treatment targeting parents' responses to their children's pain complaints and children's coping responses, or a three-session educational intervention that controlled for time and attention. Parents and children were assessed at pretreatment, and 1 week, 3 months, and 6 months post-treatment. Outcome measures were child and parent reports of child pain levels, function, and adjustment. Process measures included parental protective responses to children's symptom reports and child coping methods.

RESULTS

Children in the cognitive-behavioral condition showed greater baseline to follow-up decreases in pain and gastrointestinal symptom severity (as reported by parents) than children in the comparison condition (time × treatment interaction, P < 0.01). Also, parents in the cognitive-behavioral condition reported greater decreases in solicitous responses to their child's symptoms compared with parents in the comparison condition (time × treatment interaction, P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

An intervention aimed at reducing protective parental responses and increasing child coping skills is effective in reducing children's pain and symptom levels compared with an educational control condition.

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal pain is the most common recurrent pain complaint of childhood (1,2). Medical evaluations rarely yield evidence of an organic disease etiology. Instead, the majority of children with persistent complaints of abdominal pain meet criteria for pediatric functional abdominal pain (FAP), which is defined as episodic or continuous abdominal pain without evidence of an inflammatory, anatomic, metabolic, or neoplastic process that explains the subject's symptoms (3). FAP is associated with considerable disruption of normal activity, including school attendance, and emotional distress in both children and parents (4-6). It also has a significant impact on health-care costs, accounting for more than 50% of visits to pediatric gastroenterology practices (7). Moreover, FAP of childhood oft en persists into adulthood and may be related to adult irritable bowel syndrome (8-11). Finally, currently available medications have very limited effectiveness for FAP (12).

Previous research shows that the ways parents respond to their child's pain reports as well as beliefs about the significance of pain and levels of psychological distress in the child and the parent are associated with the occurrence of FAP in children (4,6,13-21). Of particular significance for this study, Levy et al. (22) have shown that parent solicitous responses to the child's report of pain and/or gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are related to an increase in both GI symptoms and disability.

Several randomized controlled trials to test the effectiveness of pain interventions in children, using a self-management approach that includes components of cognitive-behavioral therapy and involvement of parents in treatment, yielded encouraging findings for this approach (23-28). However, methodological limitations in these studies have made interpretation of results difficult. These limitations have included the use of poorly defined comparison conditions, small sample sizes, limited or no follow-up assessment, and lack of attention to the reliability and integrity of the content of the intervention for both treatment groups.

The aim of this study was thus to test the efficacy of an intervention that (i) taught children and their parents cognitive-behavioral strategies for managing the child's symptoms of FAP and (ii) taught parents social learning strategies to reduce solicitousness to illness behavior in their children and to both model and reinforce healthier ways for their children to respond to GI discomfort. The primary hypotheses were that at the end of the intervention and during follow-up, children in a Social Learning/Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (SLCBT) group, compared with children in a Education Support (ES) group would (i) exhibit a greater decrease in pain, other GI symptoms, and functional disability; and (ii) parents in this condition would demonstrate greater reductions in solicitous responses to illness behavior.

Secondary hypotheses were that children in the SLCBT condition, compared with children in the ES group would (iii) exhibit greater reductions in anxiety and depression, and (iv) demonstrate more adaptive pain beliefs and cognitive coping skills at the end of treatment and during follow-up.

METHODS

Design and procedure

The study was a prospective, randomized, controlled trial with blinded assessment of outcome. The treatment was comprised of three sessions that were approximately 1 week apart (see Intervention section below). Participants completed assessments at baseline (1 week before treatment and before knowledge of treatment condition assignment), 1 week post-treatment, 3 months post-treatment (3 mos post-tx), and 6 months post-treatment (6 mos post-tx). At all assessment points, parents were mailed a packet of questionnaires to complete on their own and mail back. Children completed assessments through telephone. A nurse from the Pediatric Clinical Research Center at Seattle Children's Hospital administered the phone assessment. Appointments were scheduled in advance, and answer keys were mailed to children before the calls. Answer keys guided children through the questions and response options, aiding administration. Nurse assessors were blind to the treatment assignment of the children.

Participants

Participants included 200 children and teens, aged 7–17 years, with chronic abdominal pain, and their parents. Families were recruited over a 4-year period from 2005–2009 through physician referral from the pediatric GI clinics at Seattle Children's Hospital and the Atlantic Health System in Morristown, New Jersey. Seattle participants were also recruited through local area clinics and community-posted flyers. All interested participants were screened for eligibility by the physician co-investigator in the respective GI clinic. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Seattle Children's Hospital and the Atlantic Health System. Parents gave informed consent, and children gave assent before commencement of research procedures. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov as study number NCT00494260.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) child ages 7–17 years, (ii) three or more episodes of recurrent abdominal pain during a 3-month period, and (iii) child and parent cohabited for the past 5 years or, in cases of divided custody, for at least half of the child's lifetime. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) positive physical or laboratory findings which would explain the abdominal pain, (ii) any chronic disease (e.g., Crohn's, ulcerative colitis, pancreatitis, diabetes, epilepsy, celiac sprue), (iii) lactose intolerance as diagnosed by the attending physician, (iv) major surgery within the past year, (v) developmental disabilities requiring full-time special education or impairing ability to communicate, and (vi) non-English speaking.

Randomization and assignment

Participants were enrolled by a researcher at the recruitment site before randomization. Randomization was then performed by a different researcher using a computerized random-number generator, stratifying by age (8–11 and 12–17 years). This was performed after completion of the baseline assessment. Participants were blind to their group assignment until commencement of the first treatment session.

Study flow

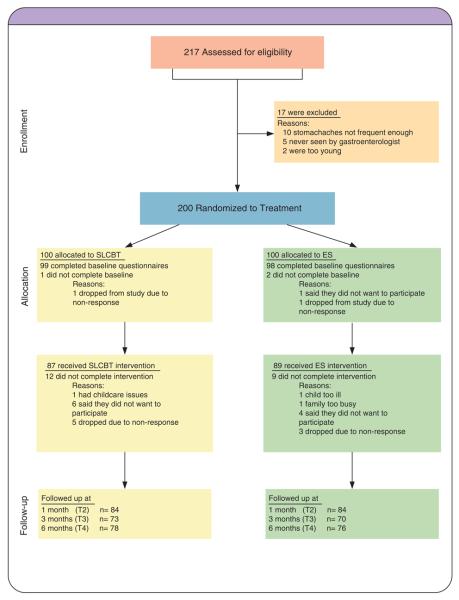

Figure 1 illustrates the disposition of all participants at all stages of the study. As shown, 217 were assessed for eligibility and 200 were found to be eligible. These 200 participants were randomly assigned to two treatment conditions, SLCBT (n = 100) or ES (n = 100). Eighty-seven participants completed the three sessions of the SLCBT intervention and 89 completed the three sessions of the ES intervention. The overall attrition rate was 10.5%.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

Intervention conditions

Participants in both conditions continued with their regular medical care as recommended by their health-care team. Following completion of assessment, all participants met with one of 14 trained therapists (Master's degree or higher) for three in-person sessions spaced approximately 1 week apart (mean time spread from session 1 to session 3 = 19.06 days, s.d. = 7.60). Study therapists were trained in and administered both interventions. Participant families had the choice of having these sessions in the hospital clinic or, for convenience, their homes. The home option was chosen approximately 28% of the time. The family was asked to have the primary care parent attend with the child. Sessions lasted approximately 75 min. The clinician spent time with the parent and child together, then the child or parent alone followed by the other (the order being their choice), then both together again. About 60% of the time was spent with child and parent together, 20% with the parent alone, and 20% with the child alone.

Social learning and cognitive-behavioral therapy

The SLCBT condition was based on two principles derived from previous research: (i) parents who respond solicitously to the child's pain reports and parents who report GI symptoms themselves (i.e., who may model illness behavior) tend to have children with more abdominal pain and other GI symptoms (22), and (ii) parent and children's beliefs about the significance of pain and the ways they cope with pain may influence the amount of pain the child reports.

The SLCBT treatment condition consisted of three major components: relaxation training, working with parent and child to modify family responses to illness and wellness behaviors, and cognitive restructuring to address and alter dysfunctional cognitions regarding symptoms and their implications for functioning through cognitive therapy techniques. Active skill practice in session and identification and assignment of skills to practice between sessions occurred throughout the study.

The first session began with an introduction to the study and a rationale for the treatment components, as well as rapport building with the family. An assessment of current functioning and symptom presentation was conducted to help provide the therapist with information needed to work with the family in altering maladaptive patterns of behavior and beliefs. All three components were introduced in the first session along with their rationale. The primary focus in the first session was on teaching relaxation training as a stress and symptom management tool and introducing concepts of social learning, modeling, and reinforcement. The latter included an introduction to understanding how social responses can influence the experience of pain, and education in redirecting attention to wellness behaviors, coping and skill building rather than illness behavior. Relaxation training included training in paced diaphragmatic breathing, and progressive muscle relaxation. Training in imagery was also included if children had difficulty with other types of relaxation.

The second session began with a review of the homework (relaxation and social learning assignments). It then expanded on the rationale for examining cognitions regarding symptoms. A specific technique for examining and challenging unhelpful thoughts was presented in simplified form appropriate to the age level of the child and demonstrated in session. Parents and children were instructed in how to identify and modify such cognitions. In addition, troubleshooting and expansion of skills in relaxation and social learning were targeted in this session.

The third session again began with a review of homework, which included the cognitive homework as well as relaxation and social learning assignments. The focus of this session was on review and consolidation of skills learned, and development of a plan with the family for maintaining skill use after treatment ended. There were opportunities for troubleshooting any difficulties the family may have had in implementing the treatment and answering questions.

Education Support

The ES condition was developed to provide a credible alternative condition that would control for therapist and patient time and attention. It included three sessions with the same amount of therapist time as SLCBT. Care was taken to include homework assignments, which required similar time and effort as SLCBT assignments. Similar to SLCBT, the first session also began with an introduction to the study, rationale for the treatment, rapport building, and assessment. The content of the ES condition focused on education about GI system anatomy and function, information about the United States Departments of Agricultural nutrition guidelines, and additional food-related information, such as how to read food product labels. Therapists did not endorse any specific food or diet recommendations.

Measures

Baseline characteristics

Demographic characteristics were assessed by parent report. Baseline duration of child abdominal pain was assessed with an item from the parent-report version of the Questionnaire on Pediatric Gastrointestinal Symptoms (QPGS). The QPGS assesses the Rome III symptom criteria for pediatric functional GI disorders and has good content validity and test-retest reliability (29-31).

Primary outcome variables

Pain was assessed by the Faces Pain Scale-Revised (32). This scale consists of four line drawings of faces showing gradual increases in pain expression. We focus here on the current pain item: “Choose the face that shows how much you hurt right now.” Ratings were made independently by children with respect to their own pain and parents with respect to their child's pain.

GI Symptoms were assessed using the GI Symptom subscale of the Children's Somatization Inventory (33-35). Seven items (nausea or upset stomach; constipation; loose bowel movements or diarrhea; stomachaches; vomiting; feeling bloated or gassy; and food making you sick) are rated for severity during the past 2 weeks using a 0–4 scale by asking, “In the last 2 weeks, how much were you bothered by each symptom?”. Response options were “not at all”, “a little”, “some”, “a lot”, and “a whole lot” . Children rated the items with respect to their own symptoms, and parents rated the items with respect to their child's symptoms.

General disability was measured with the Functional Disability Inventory (36,37). The Functional Disability Inventory was developed specifically for children and adolescents. This scale was selected because it was recommended as an outcome measure in the consensus statement on core outcome domains and measures for pediatric pain (38). Respondents are asked to rate the extent to which activities such as “walking to the bathroom” or “playing sports” have been difficult or posed a physical challenge during the past week using a 0–4 scale. Children rated the items with respect to themselves, and parents rated the items with respect to their child.

Secondary outcome variables

Child depression was measured using the parent- and child-report versions of the Child Depression Inventory (39). Summary scores are reported (theoretical range of 0–54, with higher values indicative of greater depressive symptomatology).

Child anxiety was measured using the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (40). It contains multiple subscales, but we focus here on the Anxiety Disorders Index. Sample items are “I feel tense or uptight” and “I keep my eyes open for danger.”

Process variables

Parental solicitousness in response to pain behavior was measured using the Protectiveness subscale of the Adults' Responses to Children's Symptoms (18,41). Sample items include, “When your child has a stomachache or abdominal pain, how often do you bring him/her special treats or little gifts?” or “…let him/her stay home from school?” Ratings are made on a 0–4 scale, with higher values indicative of greater solicitousness.

Pain coping skills were measured using the Pain Response Inventory (42,43). The Pain Response Inventory is a child self-report questionnaire designed to assess responses to pain. It includes multiple subscales, but the ones targeted by the SLCBT intervention and analyzed in this study were the Catastrophizing, Distract/Ignore, and the Minimizing Pain subscales. The catastrophizing subscale contains items such as, “When you have a stomachache, how oft en do you think to yourself that you might be really sick?” The Distract/Ignore subscale contains items such as, “When you have a stomachache, how often do you do something you enjoy so you won't think about it?” The Minimizing Pain subscale contains items such as, “When you have a stomachache, how often do you tell yourself that it's not that bad?” Items are rated on a 0–4 scale.

Pain beliefs were assessed using the Pain Beliefs Questionnaire (PBQ) (42,44). The Pain Beliefs Questionnaire measures pain threat with items assessing the perceived duration, frequency, and seriousness of the abdominal pain condition, as well as the intensity and duration of individual pain episodes. Two additional subscales assess emotion-focused coping (items such as, “I know I can handle it no matter how bad my stomach hurts”) and problem-focused coping (items such as, “When I have a bad stomachache, I can find ways to feel better”). Children completed the items with respect to themselves, and parents completed the items with respect to their child.

Condition comparability and treatment fidelity

To assess the comparability of the treatment arms on measures of treatment participation, we measured the number of sessions completed by participants and adherence to homework assigned. To assess comparability of therapist competence across the two conditions, participants were asked to rate their belief in their therapist's competence on a 9-point scale, following completion of the first treatment session. This scale was then mailed in a sealed stamped envelope, and thus not seen by the therapist.

To assess fidelity to the protocols associated with each condition, an experienced intervention trainer listened to audiotapes of at least one session for 20% of the cases who completed treatment. These sessions were scored to determine whether the therapist had included the appropriate elements for that treatment condition. Sessions were sampled from each therapist, and were selected within therapists on a random basis. Approximately one-third of these session tapes were also rated to determine if any elements specific to the other condition had been included (i.e., if treatment conditions were cross-contaminated).

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL) and SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC). A series of linear mixed model regression analyses for repeated measures data were conducted to examine the effects of treatment condition over time on each of the primary, secondary, and process-oriented variables. Mixed model analyses allow for the specification of a covariance structure that accounts for within-subject correlation over time. Unlike traditional approaches to analysis of repeated measures data that eliminate subjects with missing data, mixed models use all available data to generate valid maximum likelihood parameter estimates when the data are assumed to be missing at random. Each repeatedly measured dependent variable was regressed on time, treatment condition, and the interaction of the two with baseline as the time referent. The interaction term provides parameter estimates comparing treatment effects at each time point. Child age and gender were treated as covariates in all models. Given our hypotheses regarding greater baseline to follow-up improvement in the SLCBT group as compared with the ES comparison group, our overarching focus lay on results for the time × treatment interactions as opposed to main effects. Analyses were conducted using an intent-to-treat approach. On the basis of a two-sided a α-level of 0.05, the randomization of 100 patients to each treatment group provided adequate statistical power to detect differences as small as 0.4 s.d.s between groups.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for the two treatment groups, in addition to baseline values of the outcome and process variables. Participants included 200 children between the ages of 7 and 17 years and their parents. Children were primarily female (consistent with other research (9)) and Caucasian, as were their parents. In addition, most parents were college-educated, married or cohabitating, and employed at least part-time. With respect to baseline clinical characteristics, 26% of the responding parents reported that they had been diagnosed or treated for irritable bowel syndrome. A large proportion of parents (67%) also reported that their child had experienced abdominal pain for a duration of 12 months or longer.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample as a function of treatment condition

| SLCBT | ES | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent demographics and clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, M (s.d.) | 43.7 (6.9) | 43.8 (5.8) | 0.872 |

| Gender, n (%) female | 95 (95.0) | 93 (93.0) | 0.552 |

| Race, n (%) Caucasian | 92 (95.8) | 93 (97.9) | 0.414 |

| Educational status, n (%) 4-year college degree | 61 (62.2) | 59 (62.1) | 0.984 |

| Employment status, n (%) employed full- or part-time | 67 (74.4) | 70 (77.8) | 0.600 |

| Marital status, n (%) married or cohabiting | 78 (79.6) | 76 (80.9) | 0.827 |

| IBS diagnosis, n (%) | 20 (27.0) | 17 (22.7) | 0.538 |

| Child demographics and clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, M (s.d.) | 11.12 (2.6) | 11.3 (2.5) | 0.663 |

| Gender, n (%) female | 71 (71.0) | 74 (74.0) | 0.635 |

| Race, n (%) Caucasian | 85 (93.4) | 87 (97.8) | 0.157 |

| Abdominal pain in past 12 months, n (%) | 61 (67.8) | 57 (65.5) | 0.670 |

| Parent-reported outcomes and process variables | |||

| Child current pain (FACES) | 2.04 (2.18) | 1.41 (1.91) | 0.035 |

| Child functional disability (FDI) | 0.86 (0.77) | 0.81 (0.71) | 0.635 |

| Child GI symptom severity (CSI) | 1.25 (0.71) | 1.10 (0.69) | 0.131 |

| Child depression (CDI) | 9.06 (6.67) | 7.75 (6.26) | 0.163 |

| Parental solicitousness (ARCS) | 1.14 (0.53) | 1.18 (0.57) | 0.588 |

| Perceived threat (PBQ) | 2.07 (0.59) | 2.00 (0.53) | 0.344 |

| Problem-focused coping (PBQ) | 1.61 (0.86) | 1.52 (0.83) | 0.469 |

| Emotion-focused coping (PBQ) | 2.58 (0.70) | 2.51 (0.78) | 0.498 |

| Child-reported process variables | |||

| Catastrophizing (PRI) | 1.63 (0.86) | 1.56 (0.87) | 0.536 |

| Distract/ignore (PRI) | 2.32 (0.79) | 2.31 (0.81) | 0.929 |

| Pain minimization (PRI) | 1.15 (0.88) | 1.48 (0.90) | 0.010 |

ARCS, Adults Responses to Children's Symptoms; CDI, Child Depression Inventory; CSI, Children's Somatization Inventory; ES, Education Support; FACES, Faces Pain Scale-Revised; FDI, Functional Disability Inventory; GI, gastrointestinal; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; PBQ, Pain Beliefs Questionnaire; PRI, Pain Response Inventory; SLCBT, Social Learning/Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

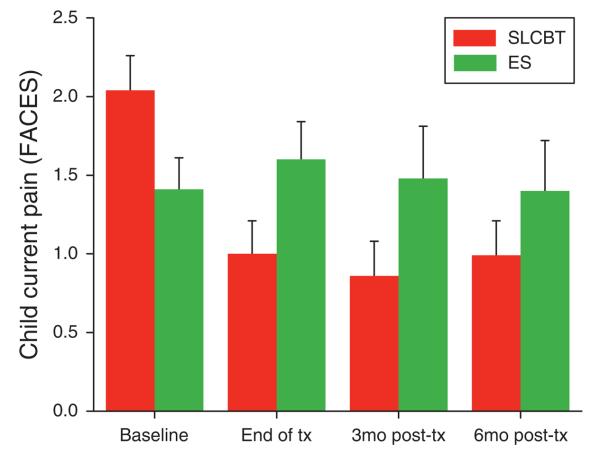

Baseline characteristics generally did not differ as a function of treatment group with the exception of two outcome measures: parent-reported child current pain (FACES) and child-reported pain minimization (PRI). Parents ultimately randomized to the SLCBT condition reported greater baseline levels of child pain as compared with those randomized to the ES condition (see baseline time point in Figure 2); and children ultimately randomized to the ES condition reported greater pain minimization coping skill as compared with those randomized to the SLCBT condition.

Figure 2.

Parent-reported child current pain (FACES): baseline to follow-up raw scores by treatment condition (M + s.e.). FACES, Faces Pain Scale-Revised.

Condition comparability and treatment fidelity

Participation in treatment was compared across conditions by examining completion data on participants who completed at least one session of either condition. Of these, 87% of SLCBT participants and 89% of ES participants completed all three sessions (P > 0.05). Homework adherence rates for SLCBT and ES were also similar, at 86.7 and 82.4 % , respectively (P > 0.05). Finally, parents gave ratings of 8.27 and 8.01 in the SLCBT and ES conditions, respectively, on a 9-point scaled question asking about how competent their therapist appeared (P > 0.05).

Assessments of fidelity of treatment implementation indicated that, overall, 94% of intervention elements were present for the SLCBT condition and 94% for the ES condition (calculated across therapists). None of SLCBT sessions included elements of the ES condition and none of the ES sessions included elements of the SLCBT condition, indicating excellent differentiation of the two conditions.

Table 2 presents results of the linear mixed models for the outcome and process variables.

Table 2.

Results of the linear mixed models: child age- and gender-adjusted mean changes from baseline (s.e.)

| End of tx | 3 Months post-tx | 6 Months post-tx |

P value for time × treatment interaction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-reported primary outcomes | ||||

| Child current pain (FACES) | < 0.01 | |||

| SLCBT | −1.04 (0.25)** | −1.16 (0.29)** | −0.99 (0.31)** | |

| ES | 0.21 (0.25) | −0.06 (0.31) | 0.06 (0.33) | |

| Difference | −1.25 (0.35)** | −1.10 (0.43)* | −1.04 (0.45)* | |

| Child functional disability (FDI) | 0.10 | |||

| SLCBT | −0.44 (0.08)** | −0.36 (0.10)** | −0.41 (0.09)** | |

| ES | −0.17 (0.08)* | −0.33 (0.10)** | −0.29 (0.10)** | |

| Difference | −0.27 (0.11)* | −0.03 (0.14) | −0.11 (0.14) | |

| Child GI symptom severity | < 0.01 | |||

| SLCBT | −0.38 (0.06)** | −0.47 (0.09)** | −0.52 (0.08)** | |

| ES | −0.05 (0.07) | −0.24 (0.10)* | −0.33 (0.09)** | |

| Difference | −0.33 (0.09)** | −0.23 (0.13) | −0.19 (0.12) | |

| Parent-reported secondary outcome | ||||

| Child depression (CDI) | 0.08 | |||

| SLCBT | −1.76 (0.38)** | −2.68 (0.53)** | −2.65 (0.54)** | |

| ES | −0.36 (0.40) | −1.68 (0.57)** | −1.32 (0.57)* | |

| Difference | −1.40 (0.55)* | −1.00 (0.77) | −1.32 (0.79) | |

| Parent-reported process variables | ||||

| Parental solicitousness | < 0.0001 | |||

| SLCBT | −0.55 (0.05)** | −0.49 (0.06)** | −0.44 (0.06)** | |

| ES | −0.16 (0.05)** | −0.25 (0.06)** | −0.21 (0.06)** | |

| Difference | −0.39 (0.07)** | −0.24 (0.08)** | −0.23 (0.08)** | |

| Perceived threat (PBQ) | < 0.0001 | |||

| SLCBT | −0.45 (0.05)** | −0.60 (0.06)** | −0.58 (0.06)** | |

| ES | −0.09 (0.05) | −0.31 (0.06)** | −0.25 (0.06)** | |

| Difference | −0.36 (0.07)** | −0.30 (0.08)** | −0.34 (0.09)** | |

| Problem-focused coping (PBQ) | < 0.0001 | |||

| SLCBT | 0.91 (0.09)** | 0.83 (0.10)** | 0.77 (0.10)** | |

| ES | 0.23 (0.10)* | 0.21 (0.10)* | 0.36 (0.10)** | |

| Difference | 0.68 (0.13)** | 0.61 (0.14)** | 0.41 (0.14)* | |

| Emotion-focused coping (PBQ) | 0.02 | |||

| SLCBT | 0.55 (0.06)** | 0.64 (0.07)** | 0.63 (0.07)** | |

| ES | 0.29 (0.06)** | 0.39 (0.07)** | 0.36 (0.08)** | |

| Difference | 0.26 (0.09)** | 0.25 (0.10)* | 0.27 (0.10)** | |

| Child-reported variables | ||||

| GI symptom severity | 0.03 | |||

| SLCBT | −0.39 (0.06)** | −0.40 (0.07)** | −0.56 (0.07)** | |

| ES | −0.14 (0.06)* | −0.28 (0.07)** | −0.37 (0.08)** | |

| Difference | −0.25 (0.08)** | −0.12 (0.09) | −0.20 (0.11) | |

| Catastrophizing (PRI) | 0.16 | |||

| SLCBT | −0.51 (0.08)** | −0.60 (0.09)** | −0.65 (0.09)** | |

| ES | −0.24 (0.08)** | −0.44 (0.09)** | −0.48 (0.09)** | |

| Difference | −0.27 (0.12)* | −0.15 (0.12) | −0.17 (0.13) | |

| Distract/ignore (PRI) | 0.01 | |||

| SLCBT | 0.28 (0.08)** | 0.20 (0.08)* | 0.21 (0.09)* | |

| ES | −0.03 (0.08) | −0.08 (0.09) | 0.12 (0.09) | |

| Difference | 0.32 (0.11)** | 0.28 (0.12)* | 0.09 (0.12) | |

| Pain minimization (PRI) | < 0.001 | |||

| SLCBT | 0.44 (0.10)** | 0.51 (0.10)** | 0.61 (0.11)** | |

| ES | −0.13 (0.10) | −0.04 (0.10) | 0.05 (0.11) | |

| Difference | 0.57 (0.14)** | 0.55 (0.15)** | 0.56 (0.15)** |

CDI, Child Depression Inventory; ES, Education Support; FACES, Faces Pain Scale-Revised; FDI, Functional Disability Inventory; GI, gastrointestinal; PBQ, Pain Beliefs Questionnaire; PRI, Pain Response Inventory; SLCBT, Social Learning/Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; tx, treatment.

A single asterisk denotes P<0.05; a double asterisk denotes P<0.01. Tests of significance within treatment groups assess change from baseline at a given follow-up time point. Tests of significance between treatment groups (difference estimates) assess SLCBT/ES differences in change over time. For all measures except PBQ emotion-focused and problem-focused coping, negatively signed estimates indicate improvement (e.g., pain reduction) relative to baseline. For the two coping subscales, positively signed estimates indicate improvement (increased coping confidence) relative to baseline.

Primary outcomes

Pain

Parents in the SLCBT condition reported greater reductions in their child's pain from baseline to follow-up relative to parents in the ES condition at the end of tx, 3 mos post-tx, and 6 mos post-tx. (See Figure 2 for raw data as a function of time and treatment condition.) This is supported by the significant time × treatment interaction for parent-reported pain shown in Table 2. A commensurate time × treatment interaction did not emerge for child-reported pain, P>0.05 (data not shown).

Functional disability

Functional disability as reported by parents decreased (improved) from baseline to post-tx in both treatment conditions, more so for SLCBT than ES at the end of tx, but the overall time × treatment interaction did not reach statistical significance. Child-reported disability likewise showed improvement over time in both treatment conditions, with no significant time × treatment effect (P > 0.05, data not shown).

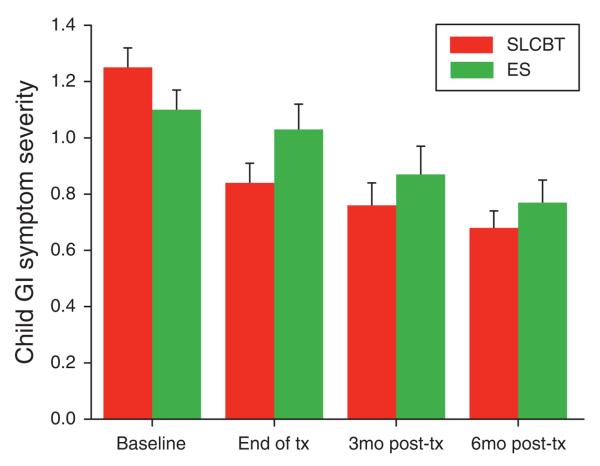

GI symptom severity

GI symptom severity as reported by the parent improved significantly more in the SLCBT condition than in the ES condition (Table 2), although this difference was significant only at the immediate post-treatment time point. See Figure 3 for raw scores as a function of time and treatment condition. A similar pattern emerged for child-reported GI symptom severity as shown in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Parent-reported child gastrointestinal (GI) symptom severity: baseline to follow-up raw scores by treatment condition (M + s.e.).

Secondary outcomes

Child depression and anxiety

Parent-reported child depression improved more in the SLCBT group compared with the ES group; this difference was statistically significant at the end of tx. Child self-reported depression, in contrast, did not differ as a function of time and treatment condition, nor did child self-reported anxiety (P > 0.05, data not shown).

Process variables

Parental solicitousness in response to pain behavior

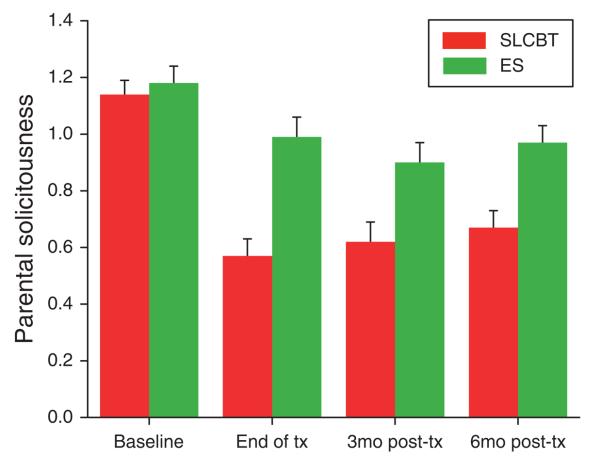

As predicted, the SLCBT group showed a significantly greater reduction in parental protectiveness (solicitousness in response to pain reports) than the ES group. This difference was significant at all three follow-up time points. See Table 2 for results of the mixed models and Figure 4 for the raw data.

Figure 4.

Parental solicitousness: baseline to follow-up raw scores by treatment condition (M + s.e.).

Pain beliefs

Parents in the SLCBT condition reported greater reductions in the perceived threat of their child's pain relative to parents in the ES condition, at all three time points. In addition, parents in the SLCBT condition (again, relative to those in the ES condition) reported greater baseline to follow-up increases in their child's emotion-focused and problem-focused coping confidence; these effects too held for all follow-up time points. Turning to child-reported pain beliefs, similar results emerged only for problem-focused coping confidence. Children in the SLCBT condition reported greater baseline to follow-up increases in their problem-focused coping confidence relative to those in the ES condition—at the end of tx and 3 mos post-tx (P value for time × treatment interaction < 0.05, data not shown).

Coping skills

Children in the SLCBT condition reported greater baseline to follow-up increases in pain minimization relative to children in the ES condition, at all three time points. They also demonstrated greater increases in the ability to distract themselves and ignore their pain—at the end of tx and 3 mos post-tx as shown in the bottom portion of Table 2.

DISCUSSION

This study has demonstrated that a very brief social learning/cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention can reduce parent-reported abdominal pain and related GI symptoms in children compared with an educational support condition. Children in families in the SLCBT group improved significantly more than children in the ES group on abdominal pain-related symptoms and desirable beliefs and pain coping strategies, as well as parental solicitousness in response to pain behaviors. Most importantly, many of these differences were maintained 6 months after intervention. The study included features that addressed many of the methodological limitations of previous studies, including a comparison condition that controlled for time and attention, follow-up to determine if the intervention effects were maintained, and a large sample size. In addition, we demonstrated that the interventionists adhered to the treatment protocols and maintained the integrity of the interventions.

Two of three primary outcome measures selected a priori improved more in the SLCBT group than in the ES group; these were current pain intensity as reported by parents and GI symptom severity as reported by both parents and children. Although it may be argued that current pain captures data on this symptom at only a single time point and thus may be a less reliable indicator by itself of improvement, the GI Symptom Severity score provides a measure of symptoms, including abdominal pain, over the previous 2 weeks, and provides an arguably more stable estimate of pain and other symptoms over a longer time period. We believe that the use of different measures to tap both current and longer term report of symptoms based on multiple sources (parent and child report) provides a balanced measurement strategy that affords a more comprehensive assessment of outcome. We were not able to demonstrate a significant difference between conditions in functional disability following treatment, possibly due to a floor effect. As shown in Table 2, both treatments yielded substantial, statistically significant reductions in functional disability relative to baseline, and the SLCBT group showed greater reduction at the end of tx; however, the time × treatment interaction demonstrated only a trend (P = 0.10).

On the basis of social learning theory, we hypothesized that the frequency and intensity of children's reports of pain and GI symptoms may be influenced, at least in part, by parental responses. Therefore, our SLCBT condition was designed to decrease solicitous parental responses. As hypothesized, the significantly greater decrease in the process variable of parental solicitousness was found in this condition compared with the ES group. These results, combined with the previously reported improvements in pain and other outcomes in the SLCBT condition, support the social learning component of the treatment. This finding is also consistent with data obtained by Walker et al. (21). In this laboratory study, a water load symptom provocation task was used to induce discomfort in well children and abdominal pain patients. Compared with children whose parents were given no instructions, symptom complaints increased in children whose parents were instructed to pay attention to their symptoms, while the complaints of children whose parents were instructed to distract their child decreased. They also found that parents of children with pain rated distraction as having greater potential negative impact on their children than attention. Thus, this study succeeded in changing parents' behavior in a direction that was likely contrary to their beliefs. Nevertheless, most did not drop out of treatment and they rated their therapists as highly competent.

The cognitive-behavioral approach component of the SLCBT condition, which aimed at improving children's coping strategies, was also supported by the significantly greater improvements in the SLCBT condition compared with the ES condition on most of the coping scales. Therefore, the process variables demonstrated that the SLCBT intervention was effective in its two major objectives—reducing solicitous responses of parents and improving coping skills of children.

Another finding of interest in this study is that although child-reported outcomes are in the expected direction, they are not as strong as parent-reported outcomes. This is not uncommon, as parents and children have been shown to have different perspectives on children's symptoms (45). However, it could be argued that parental perceptions are important and critical to maintenance of improvement, as parents influence how symptoms affect a child's life, such as health-care utilization and school attendance. In any case, these differences support obtaining reports from both parents and children, as was done in this study.

Because the SLCBT training directed parents to pay less attention to their child's pain reports, it could be suggested that this treatment did not modify the amount of pain experienced by the child, but only the amount of pain reported to parents. The failure to find significant differences between groups in child report of pain might be seen as supporting this. However, the significant time × treatment interaction in problem-focused coping, which was based on child report (Table 2), shows that children in the SLCBT condition developed greater confidence in their ability to find ways to feel better compared with children in the ES condition. Moreover, the SLCBT group did not report greater increases in emotion-focused coping confidence—a measure that assesses one's ability to handle pain even if it is really bad. If they had simply stopped complaining about pain, one would expect an increase in emotion-focused coping confidence and no change in problem-focused coping confidence. Finally, although not reaching the conventional criterion of statistical significance, functional disability as reported by parents decreased (improved) from baseline to post-tx more so for SLCBT than ES at the end of tx. These findings support the interpretation that the SLCBT treatment produced significant reductions in FAP, which were not limited to the child reporting less pain to parents.

This study's goals were ambitious: the demonstration of a long-term change in a chronic pattern of behavior over and above changes observed in an attention placebo comparison condition, utilizing a very brief three session intervention. We kept the intervention brief so that it could be realistically implemented within a real-world medical practice, without placing an undue burden on either providers or families. These goals were achieved. However, it may be possible that a longer intervention including more sessions with the family could be more powerful in producing larger changes that are maintained over time. Further research on such methods, including the use of technologies that could minimize staff time by using either the internet (26) or phone contact appears worthwhile.

Limitations of the study should be noted. Participants were a volunteer group who had been referred by providers or responded to notices regarding the study. Consequently, they may not be representative of the larger population of families and children with FAP. Despite randomization, differences between conditions were observed on two baseline measures: parent-reported child current pain (on which the SLCBT group reported a higher baseline level) and child-reported pain minimization (on which the ES group reported a higher score). As noted previously, these baseline levels were controlled for in subsequent analyses of these measures. Also, Figure 2 counters any potential argument that baseline differences might explain the differences in pain reports following treatment because of a floor effect. Use of brief standardized interventions, although necessary for testing efficacy in randomized controlled trials, and deliberately chosen here for ease of conduct in a clinical setting, may not reflect results that might be obtained with longer interventions tailored to individual families. Further research is needed to determine the effective components of treatment and most effective modes of delivery. However, this study does provide an important step toward incorporating cognitive-behavioral treatment into the arsenal of interventions for children with FAP and their families.

Several practice implications can be derived from this study. First, clinicians should recognize the important role that parent responses to children's symptoms may have in influencing child coping and dysfunction, as they treat families in which a child suffers from FAP. Parent education and support for encouraging coping and wellness behaviors in their children may be an important aspect of working with these families. This study also suggests that parents and children may have beliefs about the child's symptoms that could similarly be addressed with helpful coping strategies. Clinicians could discuss these concepts directly with parents, or auxiliary staff may be involved for this purpose. The change by parents observed here, despite the likely possibility from the study by Walker et al. (21) of their having differing initial perspectives about what behavior on their part could be helpful, supports the notion that this approach can be effectively implemented. Finally, it should be noted that the SLCBT intervention in this study, although relatively brief, was nevertheless delivered by trained behavior therapists, and referral to individuals with this training may be appropriate in some situations.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported by grant number 5R01HD036069 from the National Institutes of Health—National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article : Rona L. Levy, MSW, PhD, MPH, FACG, AGAF.

Specific author contributions : Rona L. Levy participated by conceptualizing, planning, and conducting the study, collecting and interpreting data, and drafting the manuscript. Shelby L. Langer contributed by conducting the study, collecting, analyzing and interpreting data, and drafting the manuscript. Lynn S. Walker contributed by planning and conducting the study, interpreting data, and drafting the manuscript. Joan M. Romano contributed by planning and conducting the study, interpreting data, and drafting the manuscript, and by training therapists in the intervention and assessing their adherence to the treatment protocol. Dennis L. Christie and Nader Youssef contributed by planning and conducting the study and collecting data. Melissa M. DuPen contributed by collecting and interpreting data and drafting the manuscript. Andrew D. Feld contributed by planning and conducting the study and interpreting data. Sheri A. Ballard contributed by collecting data and drafting the manuscript. Ericka M. Welsh contributed by analyzing and interpreting data and drafting the manuscript. Robert W. Jeffery contributed by planning and conducting the study and drafting the manuscript. William E. Whitehead contributed by planning and conducting the study, interpreting data, and drafting the manuscript. Melissa Young and Melissa J. Coffey contributed by collecting data. All authors have reviewed and approved the final paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Potential competing interests : William E. Whitehead is a member of the Board of Directors of the Rome Foundation. Nader Youssef is currently the Director of Clinical Research at AstraZeneca LP. At the time the study was conducted, however, he was not affiliated with this company and contributed to the project by his appointment at Goryeb Children's Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGrath PA. Pain in Children: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. Guilford; New York, USA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwille IJD, Giel KE, Zipfel S, et al. A community-based survey of abdominal pain prevalence, characteristics, and health care use among children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1062–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Degnon Associates; McLean, VA, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campo JV, Bridge J, Lucas A, et al. Physical and emotional health of mothers of youth with functional abdominal pain. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:131–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claar RL, Walker LS, Smith CA. Functional disability in adolescents and young adults with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: the role of academic, social, and athletic competence. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999;24:271–80. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/24.3.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker LS, Greene JW. Children with recurrent abdominal pain and their parents: more somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression than other patient families? J Pediatr Psychol. 1989;14:231–43. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/14.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starfield B, Hoekelman RA, McCormick M, et al. Who provides health care to children and adolescents in the United States? Pediatrics. 1984;74:991–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotopf M, Carr S, Mayou R, et al. Why do children have chronic abdominal pain, and what happens to them when they grow up? Population based cohort study. Br Med J. 1998;316:1196–1200. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell S, Poulton R, Talley NJ. The natural history of childhood abdominal pain and its association with adult irritable bowel syndrome: birth-cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2071–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker LS, Garber J, Van Slyke DA, et al. Long-term health outcomes in patients with recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1995;20:233–45. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/20.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker LS, Guite JW, Duke M, et al. Recurrent abdominal pain: a potential precursor of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents and young adults. J Pediatr. 1998;132:1010–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saps M, Di Lorenzo C. Pharmacotherapy for functional gastrointestinal disorders in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:101–3. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181a15f49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy RL, Langer SL, Walker LS, et al. Relationship between the decision to take a child to the clinic for abdominal pain and maternal psychological distress. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:961–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campo JV, Bridge J, Ehmann M, et al. Recurrent abdominal pain, anxiety, and depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2004;113:817–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, et al. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr. 1996;129:220–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramchandani PG, Hotopf M, Sandhu B, et al. The epidemiology of recurrent abdominal pain from 2 to 6 years of age: results of a large, population-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:46–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramchandani PG, Stein A, Hotopf M, et al. Early parental and child predictors of recurrent abdominal pain at school age: results of a large population-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:729–36. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000215329.35928.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Slyke DA, Walker LS. Mothers' responses to children's pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:387. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000205257.80044.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker LS, Claar RL, Garber J. Social consequences of children's pain: when do they encourage symptom maintenance? J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:689–98. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.8.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Psychosocial correlates of recurrent childhood pain: a comparison of pediatric patients with recurrent abdominal pain, organic illness, and psychiatric disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;102:248–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker LS, Williams SE, Smith CA, et al. Parent attention versus distraction: impact on symptom complaints by children with and without chronic functional abdominal pain. Pain. 2006;122:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, et al. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2442–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duarte MA, Penna FJ, Andrade EM, et al. Treatment of nonorganic recurrent abdominal pain: cognitive-behavioral family intervention. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:59–64. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000226373.10871.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, McGrath PJ. Online psychological treatment for pediatric recurrent pain: a randomized evaluation. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:724–36. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humphreys PA, Gevirtz RN. Treatment of recurrent abdominal pain: components analysis of four treatment protocols. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31:47–51. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palermo TM, Wilson AC, Lewandowski A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an internet-delivered family cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2009;146:205–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robins PM, Smith SM, Glutting JJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral family intervention for pediatric recurrent abdominal pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:397–408. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders MR, Shepherd RW, Cleghorn G, et al. The treatment of recurrent abdominal pain in children: a controlled comparison of cognitive-behavioral family intervention and standard pediatric care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:306–14. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baber KF, Anderson J, Puzanovova M, et al. Rome II versus Rome III classification of functional gastrointestinal disorders in pediatric chronic abdominal pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:299–302. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31816c4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caplan A, Walker LS, Rasquin A. Validation of the pediatric Rome II criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders using the questionnaire on pediatric gastrointestinal symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:305–16. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000172749.71726.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker LS, Lipani TA, Greene JW, et al. Recurrent abdominal pain: symptom subtypes based on the Rome II criteria for pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:187–91. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, et al. The faces pain scale—revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93:173–83. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garber J, Walker LS, Zeman J. Somatization symptoms in a community sample of children and adolescents: further validation of the children's somatization inventory. Psychol Assess. 1991;3:588–95. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker LS, Beck JE, Garber J, et al. Children's somatization inventory: psychometric properties of the revised form (CSI-24) J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:430–40. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker LS, Garber J, Greene JW. Somatization symptoms in pediatric abdominal pain patients: relation to chronicity of abdominal pain and parent somatization. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1991;19:379–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00919084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claar RL, Walker LS. Functional assessment of pediatric pain patients: psychometric properties of the functional disability inventory. Pain. 2006;121:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker LS, Greene JW. The functional disability inventory: measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:39–58. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, et al. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:771–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory (CDI): Technical Manual Update. Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; North Tonawanda, NY, USA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, et al. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–65. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker LS, Levy RL, Whitehead WE. Validation of a measure of protective parent responses to children's pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:712–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210916.18536.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker LS, Baber KF, Garber J, et al. A typology of pain coping strategies in pediatric patients with chronic abdominal pain. Pain. 2008;137:266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker LS, Smith CA, Garber J, et al. Development and validation of the Pain Response Inventory for Children. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:392–405. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker LS, Smith CA, Garber J, et al. Testing a model of pain appraisal and coping in children with chronic abdominal pain. Health Psychol. 2005;24:364–74. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garber J, Van Slyke DA, Walker LS. Concordance between mothers' and children's reports of somatic and emotional symptoms in patients with recurrent abdominal pain or emotional disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26:381–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1021955907190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]