Abstract

We and others have clearly demonstrated that a topoisomerase I (Top1) inhibitor, such as camptothecin (CPT), coupled to a triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) through a suitable linker can be used to cause site-specific cleavage of the targeted DNA sequence in in vitro models. Here we evaluated whether these molecular tools induce sequence-specific DNA damage in a genome context. We targeted the insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I axis and in particular promoter 1 of IGF-I and intron 2 of type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) in cancer cells. The IGF axis molecules represent important targets for anticancer strategies, because of their central role in oncogenic maintenance and metastasis processes. We chemically attached 2 CPT derivatives to 2 TFOs. Both conjugates efficiently blocked gene expression in cells, reducing the quantity of mRNA transcribed by 70–80%, as measured by quantitative RT-PCR. We confirmed that the inhibitory mechanism of these TFO conjugates was mediated by Top1-induced cleavage through the use of RNA interference experiments and a camptothecin-resistant cell line. In addition, induction of phospho-H2AX foci supports the DNA-damaging activity of TFO-CPT conjugates at specific sites. The evaluated conjugates induce a specific DNA damage at the target gene mediated by Top1.—Oussedik, K., François, J.-C., Halby, L., Senamaud-Beaufort, C., Toutirais, G., Dallavalle, S., Pommier, Y., Pisano, C., Arimondo, P. B. Sequence-specific targeting of IGF-I and IGF-IR genes by camptothecins.

Keywords: DNA regulation, specific DNA cleavage, topoisomerase I poisons, triplex-forming oligonucleotides, anticancer agents

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I and its receptor play a pivotal role in normal and neoplastic cell growth through antiapoptotic and metastasis pathways (1,2,3,4). IGF-I signaling seems to be enhanced in many tumors, such as colorectal cancer (5), thyroid cancer (6), lung cancer (7), breast cancer (8), hepatocarcinoma (9), and prostate cancer (10,11,12,13). The type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-IR) is a phylogenetically conserved tyrosine kinase receptor known to affect proliferation and motility of tumoral cells (14). It is involved in oncogenic maintenance and metastatic processes and is a relevant therapeutic target (1, 15). Recently, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and antibodies have been used to block the action of IGF-I and its receptor (16,17,18,19). Numerous nucleic acid-based strategies, including antisense RNA, antisense oligonucleotides, ribozymes, triplex-forming oligonucleotides, short hairpin RNA, and short interfering RNA (siRNA), have also been developed to block IGF and IGF-IR expression (17, 20,21,22,23,24). Although these strategies have demonstrated the role of these proteins in the induction and maintenance of the tumoral phenotype both in cellular models and in vivo (15), use of these molecules has shown the difficulties of having highly specific inhibitors. In fact, the homology of IGF-IR with the insulin receptor (IR) is a major obstacle to the development of an IGF-IR-specific molecule; this is especially an issue with the tyrosine kinase inhibitors and antibodies approaches (25). In the case of the nucleic acid-based strategies, the major drawbacks are mainly related to low efficacy and triggering of undesired side effects, as the theoretical high specificity due to base pairing remains an appealing element of these approaches. Thus, there is a real need for drugs that selectively and efficiently block IGF-I and its receptor expression in cancer cells in order to reverse the tumor status.

Previously, we developed an original approach to target topoisomerase I (Top1)-mediated DNA cleavage to a specific site on DNA through the use of Top1 inhibitors covalently attached to sequence-specific DNA ligands (26, 27). The conjugates induce a Top1-mediated DNA cleavage specifically at the binding site of the DNA ligand in vitro. Recently, we (28) have shown that camptothecin (CPT) derivatives, potent Top1 inhibitors, coupled to triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFOs) are able to target a DNA sequence present upstream of a luciferase gene in a plasmid transiently transfected in HeLa cells, leading to reporter gene inhibition. Here, the TFOs, one targeting IGF-I and one IGF-IR, were linked to 2 CPT derivatives, 10-carboxymethyloxycamptothecin (10CPT) and 7-(aminoethyloxyiminomethyl)-camptothecin (ST1968). Both types of conjugates efficiently blocked gene expression in cancer cells through the DNA cleavage action of Top1. We confirmed that the inhibitory mechanism of these TFO conjugates was mediated by Top1-induced cleavage through the use of RNA interference experiments and a camptothecin-resistant cell line. In addition, the induction of phospho-H2AX foci supports the DNA-damaging activity of TFO-CPT conjugates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides and nomenclature

All oligonucleotides were purchased from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium) or Sigma (Lyon, France) and purified with quick-spin Sephadex G-25 fine (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France); sequences are given in Fig. 1. Concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically at 25°C with molar extinction coefficients at 260 nm. TFOs contained the following modified bases: M, 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine and P, 5-propynyl-2′-deoxyuridine. The nomenclature used for TFOs and conjugates is the following: the abbreviation TFO is followed by the number 1 when targeting IGF-I and by 2 when targeting IGF-IR, then by the letter L (for linker) and by the letter n (for the number of carbon atoms in the linker) when relevant, and finally, by an abbreviation for the camptothecin derivative (10CPT or ST1968). TFOs bind in the major groove in an orientation parallel to the oligopurine strand of the target duplex. The siRNAs directed against the rat Top1 (5′-cuugacugccaagguguucTT-3′) and the human Top1 (5′-ggacuccaucagauacuauTT-3′) were adapted from Sordet et al. (29). The siRNA control for this experiment was an siRNA (at 100 nM) that does not affect Top1 expression (human: 5′ caaaacccagcgggagaagTT 3′, rat: 5′ caaaacccagagagagaagTT 3′). The IGF-IR siRNA (5′-caaugaguacaacuaccgcTT-3′) was previously described by Bohula et al. (30). In oligonucleotide sequences, lowercase letters indicate ribo residues; uppercase letters indicate deoxynucleotides.

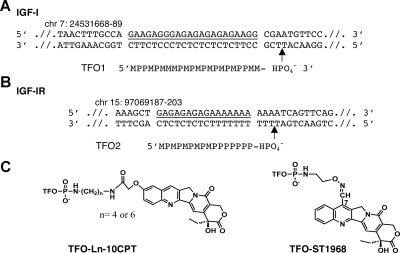

Figure 1.

A) Sequence of TFO1 and the rat IGF-I promoter 1 DNA target (underscored) used in this study. B) Sequence of the target region in intron 2 of human IGF-IR. TFO2 is directed against a 16-bp sequence (underscored). TFOs bind in the major groove, parallel to the oligopurine strand of the duplex M, 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine and P, 5-propynyl-2′-deoxyuridine. Positions on the genomes are annotated (Ensembl Release 48). Arrows indicate the cleavage site induced by the conjugates. C) Chemical structures of the camptothecin conjugates.

Synthesis of conjugates

10CPT was conjugated to the terminal amino group of a diaminoalkyl linker arm of the oligonucleotide (TFO-Ln-10CPT) as described by Arimondo et al. (28). For synthesis of TFO-ST1968, 500 μg (∼70 nmol) of 3′-phosphorylated oligonucleotide (TFO1 or TFO2) was precipitated as hexadecyltrimethylammonium salt and then dissolved in 50 μl of dry Me2SO. Solutions of 4-N,N-dimethylaminopyridine (5 mg in 25 μl of Me2SO, 41 μmol), dipyridyl disulfide (6.6 mg in 25 μl of Me2SO, 30 μmol), and triphenylphosphine (7.9 mg in 25 μl of Me2SO, 30 μmol) were added. After 15 min of incubation at room temperature, the activated oligonucleotide was precipitated with 2% LiClO4 in acetone. A solution of ST1968 (500 μg, 1 μmol) in a Me2SO:H20 (80:20) solution was then added. The mixture was kept at room temperature for 2 h to give the desired TFO-ST1968 conjugate.

Purification and characterization of conjugates

After precipitation with 2% LiClO4 (v/v) in acetone, the oligonucleotide conjugates (TFO-Ln-10CPT and TFO-ST1968) were purified by reverse-phase HPLC with a linear acetonitrile gradient (0→80% CH3CN in 0.2 M ammonium acetate). The average yield was 40% for TFO-Ln-10CPT and 60% for TFO-ST1968. The oligonucleotide-drug conjugates were characterized by ultraviolet spectroscopy, denaturing gel electrophoresis, and mass spectrometry: TFO1-L6-10CPT MS (ES−) m/z: 7441 [M-H]− (calculated: 7440); TFO1-ST1968 (ES−) m/z: 7354 [M-H]− (calculated: 7354); TFO2-L4-10CPT MS (ES−) m/z: 5618 [M-H]− (calculated: 5618); and TFO2-ST1968 MS (ES−) m/z: 5560 [M-H]− (calculated: 5560).

Plasmids and DNA fragments

The plasmid p(−19,+358)rIGF1-Hook, used in Top1 cleavage assays, resulted from the subcloning of the 377 bp DraI-HindIII fragment of the pIGF-1711/luc (31) into the pHook-3 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) opened at HindIII and DraI sites. The digestion of the p(−19,+358)rIGF1-Hook by XbaI and FspI yielded a 230-bp fragment containing the 22-bp IGF-I promoter I target duplex. The 3′-end of this fragment was labeled by the Klenow polymerase and [α-32P]dATP (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The plasmid pCAPS was purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN, USA), and the 54-bp IGF-IR duplex target, corresponding to part of IGF-IR intron 2, was inserted at the Mlu NI unique restriction site. The digestion of the plasmid by EcoRI and EcoRV yielded a 277-bp fragment suitable for the 3′-end labeling by the Klenow polymerase and [α-32P]dATP (GE Healthcare).

Top1 cleavage assay

Top1 DNA cleavage products were analyzed on the above-described radiolabeled target duplexes (231 and 277 bp; 50 nM) with 2 U of human Top1 as described by Arimondo et al. (28). The experiments were repeated 5 times.

Cell cultures

The rat hepatocarcinoma cell line (LFCLI1) stably expresses luciferase under the control of the IGF-I promoter (32). This cell line was grown in minimal essential medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.2 mg/ml geneticin (Sigma) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Human prostate cancer cells (DU145) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA; HTB-81). DU145RC0.1 cells are camptothecin resistant; this resistance is conferred by a mutated Top1 (33). These cell lines were grown in the RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cell transfections

Transfections of conjugates, control oligonucleotides, and siRNA were performed by using Nanofectin (PAA Laboratories, Pasching, Austria) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for LFCLI1 cells and Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) for DU145 and DU145RC0.1 cells.

Measurement of luciferase activity

Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 110,000 cells/ml in 125 μl. Twenty-four hours after transfection of the conjugates or control oligonucleotides, Photinus pyralis luciferase activity was measured in cell extracts using the Luciferase Assay Reagent kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Luminescence was measured using a microplate luminometer (Victor2; Wallac, Wellesley, MA, USA). The experiments were performed in triplicate. A phosphorothioate antisense oligonucleotide, containing 5-propynyl U (U) and propynyl C (C) and directed against the luciferase gene (Asluc: 5′-CGUGAUGUUCACCUC-3′), was used as control for efficacy of transfection; a mutated antisense oligonucleotide (mutAsluc: 5′-CGCUUUCUAUAGCGC-3′) was used as a negative control. The phosphodiester conjugate (SCR-L6-10CPT; SCR: 5′-PPPPMPPPPMMMMMMP-3′), in which 10CPT is bound to an oligonucleotide that does not form a triplex with either the IGF-I promoter 1 sequence or the IGF-IR intron, was also used as a control.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Cells were seeded in 48-well plates and transfected with the oligonucleotides at the 1 μM final concentration using cationic lipids. After 24 h, cells were lysed with SideStep buffer (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). For the cDNA synthesis and the qPCR reaction, we used the kit Brilliant SYBR Green SideStep qRT-PCR Master Mix, 2Step (Stratagene). For IGF-IR mRNA, we used Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA) primers IGF-IR (IGF-IR_QT00005831). For the IGF-I system, the luciferase primer set used was designed to produce a 200-bp product (forward 5′-GAAGAGATACGCCCTGGTTC-3′ and reverse 5′-GGCTGCGAAATGTTCATACT-3′). Two housekeeping genes (GAPDH_QT00199633 and GUSBB_QT00046046; Qiagen) were used as controls. Data were normalized to the levels of these housekeeping genes. All qRT-PCR experiments were run in quadruplicate. PCR efficacy was between 95 and 99.6% with these primers.

Western blotting analysis of IGF-IR

Levels of IGF-IR protein were analyzed 72 h after treatment at 1 μM. Proteins extracts were prepared in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 50 mM NaF, 0.1 mM NaVO4, 1 mM DTT, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Biosciences). After 20 min on ice, the extracts were centrifuged and supernatants were stored at −70°C. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated on an 8% acrylamide SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 0.1% Tween/PBS and then treated with 1 μg/ml anti IGF-IRB (C-20) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or 2 μg/ml AC-74 monoclonal anti β-actin antibody (Sigma). Proteins were visualized with ECL Plus (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative expression corresponds to the ratio between IGF-IR and β-actin bands, determined by ImageProPlus software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Fluorescence microscopy of histone γ-H2AX localization

Cells were seeded in 48-well plates and transfected with the oligonucleotides at the 1 μM final concentration on use of cationic lipids (Oligofectamine or Nanofectin, as described above). After 24 h, cells were attached to glass coverslips using poly-l-lysine and were fixed and permeabilized using 4% paraformaldehyde and ice-cold 70% ethanol. After 2 PBS washes, nonspecific binding was blocked using PBS with 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and 8% FCS at room temperature for 1 h. Cells were washed 3 times, 5 min each, in PBS 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and 1% FCS. Fixed cells were stained with primary anti-phosphoH2AX monoclonal antibody (1:1500 in PBST-1% BSA; JBW301; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA) and tagged with fluorescent Cy3-anti-mouse IgG antibody (TRITC goat anti-mouse IgG; 1:500 in PBST-1% BSA; Sigma) for 45 min at room temperature. Slides were mounted using PPD mounting liquid [1 g/L p-phenylenediamine (Sigma) in 90% glycerol buffered with 10% PBS] and sealed. Immunofluorescence microscopy was done in a Leica DMIRE2 microscope system equipped with a Plan Apo ×100 numerical aperture 1.4 oil objective (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were recorded with a coolsnap HQ CCD Camera (Roger Scientific Princeton Instruments, Monmouth, NJ, USA), collected as TIFF files, and processed with Metamorph (Universal Imaging Corp., Marlow, UK). Image bit depth is 12 bits, and pixel size is 0.129 μm.

Colony growth inhibition assay

DU145 cells were transfected as above described and seeded at 100/dish (60 mm diameter). One week after treatment, the colonies were fixed with ethanol and stained with Crystal Violet (Sigma). Colonies were observed and counted.

Proliferation assay

Cells were tested 72 h after transfection with CellTiter 96 AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RESULTS

Choice of target sequences and conjugates

To target IGF-I, we chose a 23-bp oligopurine · oligopyrimidine sequence located in the promoter 1 (Fig. 1A) that we previously identified and studied in vitro (34). In this study, we used TFO1, a 22-nt oligonucleotide containing 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine (M) instead of 2′-deoxycytidine and 5-propynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (P) instead of 2′-deoxythymidine in order to increase the triplex stability and enhance triplex formation in cells (35). In the case of IGF-IR, we chose the 16-nt TFO2, which targets a purine-rich 16-bp sequence located in the second intron (Fig. 1B). This base-modified TFO2 was previously used as model system to optimize conjugates and targeting in vitro (27).

Two camptothecin derivatives were used: 10CPT and ST1968 (Fig. 1C). The latter is a derivative of gimatecan (36), a powerful Top1 inhibitor currently in phase II clinical trials (37). These CPT derivatives were covalently linked to the 3′-end of the TFOs as described previously (28). The correct positioning of the inhibitor in the DNA-Top1 complex active site through formation of the triple helix necessitates the use of an appropriate linking arm (27). Briefly, 10CPT was covalently attached to the TFO through a diamine linker arm (Ln, n=4 for TFO2 and 6 for TFO1; Fig. 1C). ST1968 was linked directly to the TFO through the alkyl chain at position 7, functionalized with a primary amine.

Triple-helix stability

Triplex-helix formation by the TFO-Ln-10CPT and TFO-ST1968 was evaluated by gel retardation assays after different incubation times (2–48 h) at pH 7.2 and 37°C. The triplexes formed between 2 and 16 h and remained stable to at least 48 h (Supplemental Fig. 1). Table 1 reports the C50 (concentration of TFO or conjugate at which 50% of triplex is formed) after 24 h of incubation. The conjugates, TFO-10CPT and TFO-ST1968, formed slightly less stable triplexes than the respective TFOs alone (2- to 5-fold).

TABLE 1.

Stability of the triple helix

| Conjugate | C50 (nM) |

|---|---|

| IGF-I target duplex | |

| TFO1 | 120 ± 50 |

| TFO1-L6-10CPT | 300 ± 50 |

| TFO1-ST1968 | 220 ± 120 |

| IGF-IR target duplex | |

| TFO2 | 90 ± 60 |

| TFO2-L6-10CPT | 520 ± 30 |

| TFO2-ST1968 | 240 ± 70 |

Values are means ±se of 3 independent experiments. C50 is the concentration at which 50% of the triplex is formed after incubation for 24 h at 37°C in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 10% sucrose, and 0.5 μg/μl tRNA.

In vitro cleavage by Top1

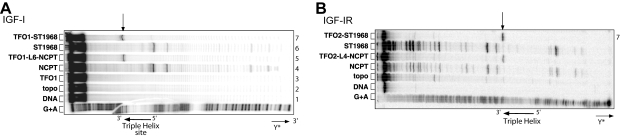

We then verified that the conjugates induced Top1-mediated DNA cleavage specifically at the triplex site (Fig. 2) using radioactively labeled DNA targets (a 230-bp target in the case of IGF-I, and a 277-bp target in the case of IGF-IR) according to the procedure described by Arimondo et al. (27). Although 10CPT and ST1968 induced cleavages at many sites along the DNA target (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 6), conjugates (lanes 5 and 7) induced only sequence-specific DNA cleavage at the triplex site (Fig. 2, arrow). Treatment with the conjugate TFO-ST1968 resulted in 15 ± 0.2% cleavage of the target in both systems, and TFO-Ln-10CPT treatment resulted in 10 ± 1% cleavage. It is noteworthy that the conjugates were used at concentrations 10 times lower (1 μM) than those used for the drugs alone (10 μM). The conjugates thus significantly increased the local concentration of the drug at the binding site of the TFO.

Figure 2.

Sequence analysis of the Top1-mediated cleavage products of IGF-I and IGF-IR. Duplexes were radiolabeled on the 3′-end of the oligopyrimidine-containing strand. Adenine/guanine lane (G+A) corresponds to Maxam-Gilbert sequencing. Arrows indicate positions of cleavage sites. A) IGF-I: lane 1, duplex alone; lane 2, duplex incubated with Top1; lane 3, duplex incubated with Top1 in the presence of 1 μM TFO; lane 4, 10 μM 10CPT; lane 5, 1 μM TFO1-L6-10CPT; lane 6, 10 μM ST1968; lane 7, 1 μM TFO1-ST1968. B) IGF-IR: lane 2, duplex alone; lane 3, duplex incubated with Top1; lane 4, duplex incubated with Top1 in the presence of 10 μM 10CPT; lane 5, 1 μM TFO2-L4-10CPT; lane 6, 10 μM ST1968; lane 7, 1 μM TFO2-ST1968.

Cellular activity of conjugates

Activity of IGF-I conjugates on an integrated luciferase reporter system

To measure the cellular activity and the mechanism of action of the conjugates directed against the promoter 1 of IGF-I, we used a luciferase reporter gene construct. The rat hepatocellular carcinoma cell line LF was engineered to contain the P. pyralis luciferase gene under the control of the IGF-I promoter 1 integrated into the cell’s genome (Fig. 3A, LFCLI1; ref. 32). The specific Top1-mediated DNA cleavage induced by the conjugates on the IGF-I promoter 1 should prevent luciferase gene transcription (which can be detected as a decrease in light signal). TFO1-L6-10CPT and TFO1-ST1968 conjugates and control oligonucleotides were transfected into the cells with various commercial cationic lipids and dendrimers. We used an antisense oligonucleotide that targets the P. pyralis luciferase gene (Asluc) as a control (38). It is difficult to efficiently transfect nucleic acids into this cell line: the best results were obtained with Nanofectin.

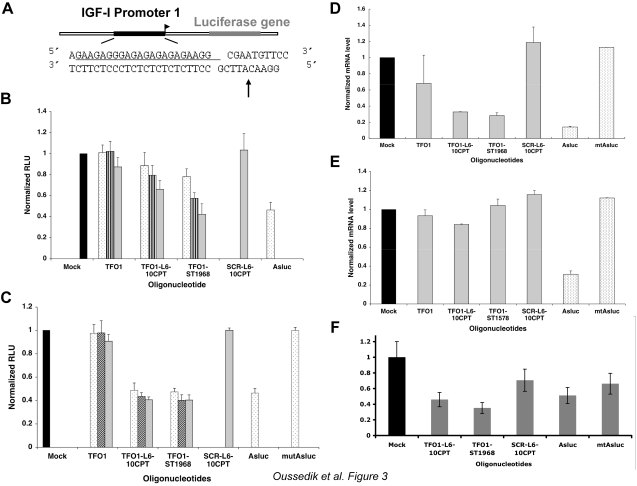

Figure 3.

Cellular activity of the IGF-I conjugates. A) Experimental construction in rat hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. B) Activity 24 h after transfection. LFCLI1 cells (black bars) were transfected with the oligonucleotides at 100 nM (dotted bars), 500 nM (hatched bars), or 1000 nM (gray bars) using Nanofectin. Relative luciferase activity is expressed as light units normalized to total protein amount and to the untreated cells. Values are means ± sd (error bars) from 3 independent experiments. C) Activity 72 h after transfection. D) Measurement of luciferase mRNA by qRT PCR at 1 μM (gray) of conjugates and 100 nM of antisense luciferase (Asluc) and mutated antisense luciferase (mtAsluc). Cells were analyzed 24 h after transfection, IGF-I signal was normalized to untreated cells and to β-glucuronidase (GUSB). Values are means ± sd from 3 independent experiments. E) Same experiment as in D except that cells were transfected with 100 nM siRNA directed against human Top1 72 h before transfection of the conjugates. F) Same experiment as in E except that cells were transfected with 100 nM siRNA control, 72 h before transfection of the conjugates.

We observed a dose-dependent decrease of the luciferase signal in the presence of the conjugates (40% for TFO1-L6-10CPT and 60% for TFO1-ST1968, both at 1 μM, 24 h after transfection; Fig. 3B). The TFO1 alone, protected at the 3′-end by a hexamethyleneamino group, had a negligible effect even at the highest concentration. This stressed the importance of the CPT linked to the TFO. We also used a control conjugate (SCR-L6-10CPT) in which the 10CPT is bound to an oligonucleotide that does not form a triplex on the IGF-I promoter 1 target. No inhibition of the luciferase gene was observed in its presence, indicating that the CPT attached to an oligonucleotide that does not bind on the DNA had no effect. This is in agreement with our previous findings on transient luciferase constructions (28), in which we observed that when the DNA triplex target was mutated, the TFO-CPT showed no activity, clearly indicating that the TFO moiety of the conjugates does not allow the CPT to bind to the DNA/Top1 complex; thus, no residual DNA binding capability of CPT was present. The TFO moiety of the conjugate acts as a negative tail that induces binding of the CPT moiety in the cleavage complex only at the site where the triple helix is formed (27). The positioning of the inhibitor by the TFO is such that it can activate an inactive CPT derivative (39). The effect of the sequence-specific conjugates was observed at least 72 h after treatment (Fig. 3C), with an increase in efficacy of inhibition at the lower concentration. The conjugate TFO1-ST1968 was particularly effective. Experiments were carried out up to a maximum of 72 h because we have shown that the presence of the CPT moiety at the 3′ end of the TFO protects the conjugates from degradation, which is not very significant up to 72 h (40).

We quantified the effect at the transcription level by measuring the luciferase mRNA by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3D). The DNA cleavage induced by the TFO1-L6-10CPT and TFO1-ST1968 conjugates on the IGF-I promoter 1 resulted in a reduction of the amount of luciferase mRNA. TFO1-L6-10CPT and TFO1-ST1968 conjugates (at 1 μM) reduced the level of mRNA by 70% compared with levels without conjugate. The luciferase antisense (Asluc) resulted in a reduction of 80% at 100 nM, while the mutated antisense had no effect (mtAsluc). Additional controls (TFO1 and SCR-L6-10CPT) clearly demonstrated that only TFO1-L6-10CPT and TFO1-ST1968 conjugates inhibited transcription of the luciferase signal by positioning the CPT on the IGF-I promoter.

The use of the luciferase gene under control of the IGF-I promoter 1 in the hepatocarcinomas allowed us to observe the action of the conjugates in a genomic context. We then confirmed the role of Top1 in the inhibition through the use of an siRNA directed against the rat Top1 (adapted from ref. 29). By Western blot, we determined that Top1 expression was inhibited by the siRNA between 72 and 96 h after transfection of the siRNA (Supplemental Fig. 2). In this window, the conjugates were unable to inhibit luciferase transcription (Fig. 3E); in contrast, Asluc, which does not act via a Top1-mediated DNA cleavage, inhibited transcription even though Top1 was silenced. When an siRNA control was used, which does not knock down Top1, the conjugates were still active (Fig. 3F). These results clearly indicated that the conjugates reached their target on the genome and inhibited the expression of the targeted gene by a Top1- and CPT-mediated mechanism.

Activity of IGF-IR conjugates on an endogenous target

We then assessed whether the conjugates directed against IGF-IR were active on the endogenous gene overexpressed in the prostate tumor cell line DU145, commonly used to test the effect of IGF-IR inhibition (22, 30), because of a strong correlation between defective regulation of the IGF-IR network and prostate carcinogenesis (2, 10,11,12,13).

We followed the effect of the conjugates on IGF-IR transcription in DU145 cells by qRT-PCR. Figure 4A shows the quantitation of IGF-IR mRNA 24 h after transfection with Oligofectamine of TFO2-L4-10CPT, TFO2-ST1968, and the control conjugate SCR-L6-10CPT, which binds neither to the IGF-I promoter 1 nor to the intron 2 of IGF-IR. The efficacy of transfection was verified using siRNA targeting the IGF-IR mRNA (30). Between 70 and 80% inhibition of IGF-IR was observed in the presence of the TFO2-L6-10CPT and TFO2-ST1968 conjugates at 1 μM. No inhibition was observed in the presence of TFO2, protected against 3′-exonucleases at its 3′ end. The siRNA directed against IGF-IR gave a 45% inhibition at 100 nM, whereas no inhibition was observed with a nonspecific siRNA (sicontr). The control conjugate SCR-L6-10CPT had no effect. The IGF-IR protein levels were also decreased specifically of ∼50% 24 h after transfection of the conjugates at 1 μM as evaluated by Western blotting analysis (Fig. 4B and Supplemental Fig. 4), while TFO2 alone is inactive, confirming a Top1-mediated effect.

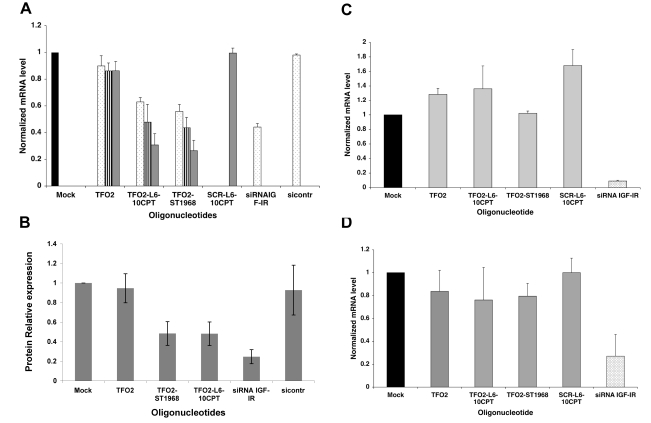

Figure 4.

A) Quantification of mRNA IGF-IR in DU145 cells. Conjugates (1 μM, gray bars; 0.5 μM, hatched bars; and 0.1 μM, dotted bars) and siRNAs (10 nM, dotted bars) were transfected into cells with Oligofectamine. mRNA quantity was measured 24 h after transfection. Experiments were run 4 times (means ± sd). IGF-IR signal was normalized to untreated cells and to the standard gene GUSB. B) Mean value of 3 experiments run in duplicate measuring IGF-IR protein levels 72 h after treatment with TFO2, TFO2-ST1968, TFO2-L6-10CPT, siRNA IGF-IR, and sicontr of DU145 cells transfected in the presence of Oligofectamine. Oligonucleotides were 1000 nM, except si was 10 nM. β-actin was used as an internal control. C) Quantification of mRNA IGF-IR in DU145RCI0.1 cells; transfections as in A. D) Quantification of mRNA IGF-IR in DU145 cells in presence of siRNA targeting Top1. Transfections as in A, but cells were first transfected with 100 nM Top1 siRNA 72 h before transfection of conjugates and controls.

Again to test the role of the Top1 in the activity of the conjugates, we inhibited human Top1 expression in DU145 cells using an siRNA (29). Transfections of the conjugates were carried out 72 h after siRNA treatment, and the IGF-IR mRNA was analyzed after additional 24 h. In fact, the Top1 expression levels were the lowest between 72 and 96 h after transfection of the siRNA (Supplemental Fig. 2), and cells have also recovered from the first transfection after this time. As shown in Fig. 4B, no inhibition of the IGF-IR mRNA was observed in the presence of the conjugates or controls after inhibition of Top1; only the siRNA directed against IGF-IR was active when Top1 was knocked down.

A further verification of the specific role of the CPT moiety of the conjugates came from experiments in the camptothecin-resistant cell line DU145RC0.1 (Fig. 4C). In this cell line, resistance to camptothecin is conferred by the Top1 mutation R364H (33). No statistically significant inhibition of IGF-IR was observed in the presence of the TFO2-L6-10CPT and TFO2-ST1968 conjugates. The siRNA targeting IGF-IR inhibited mRNA production, indicating that the absence of inhibition with the conjugates was due to the insensitivity of mutated Top1 to camptothecin and not to inefficient transfection.

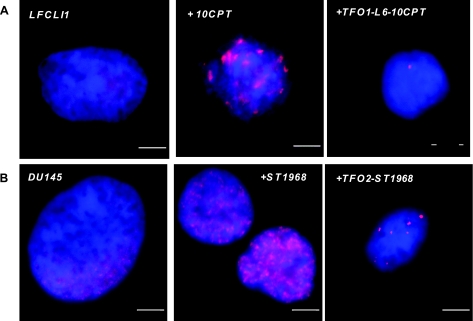

The sequence specificity of the DNA damage induced by the conjugates was demonstrated by analysis of γ-H2AX foci by immunofluorescence. Histone γ-H2AX is a commonly used biomarker of DNA damage (41). As shown in Fig. 5, treatment with 1 μM TFO1-L6-10CPT induced only 1 γ-H2AX focus in LFCLI1 cells after 24 h (Fig. 5A, right, single spots or doublets, corresponding to cells in G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle, respectively, were observed in 24 of 50 cells), while 10CPT alone (1 μM for 2 h) induced many foci (Fig. 5A, middle). Interestingly, treatment with the conjugate resulted in 1 focus instead of the expected 3 (there are 2 alleles of the endogenous IGF-I gene and 1 in the promoter of the integrated luciferase construction). Apparently, the only site in the genome accessible to triplex formation was the promoter of the luciferase construct. This may be related to the fact that IGF-I expression is low in this cell line as measured by qRT PCR (CT value >32 cycles at 1 μg total RNA). In some cases, the accessibility of the DNA target to triplex formation is correlated to the expression activity of the gene (42). In DU145 cells, we observed a discrete number of H2AXγ foci induced by TFO2-ST1968 (24 h at 1 μM; Fig. 5B, right), 4 to 14 in 58 of the 100 observed cells, none in 15 of the cells, and >15 foci in 27 of the 100 observed cells, whereas ST1968 alone (2 h at 1 μM; Fig. 5B, middle) induced a large number of DNA breaks. Clearly the conjugates greatly reduced the damage induced by CPT in cells. In the case of TFO2, the triplex target is present ∼220 times in the human genome (Ensembl Release 49) and clearly only a small number were accessible to triplex formation in DU145 cells, as confirmed for IGF-IR (Supplemental Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained in a human lung adenocarcinoma cancer cell line A549 in which IGF-IR is also overexpressed (Supplemental Fig. 6; ref. 43). Again the conjugates induce a specific DNA damage. In this cell line, a smaller number of foci is observed (1–4, mainly), clearly indicating that the target accessibility is different from cell type to cell type.

Figure 5.

Detection of γH2AX foci. Nucleus was revealed by DAPI staining (blue), and γH2AX foci were stained using rhodamine (red). A) Untreated LFCLI1 cells (left), LFCLI1 cells treated with 10CPT (1 μM, 2 h, middle), and LFCLI1 cells transfected with TFO1-L6-10CPT (1 μM, 24 h, right). B) DU145 cells (left), DU145 cells treated with ST1968 (1 μM, 2 h, middle), and DU145 cells transfected with TFO2-ST1968 (1 μM, 24 h, right). Nuclei from cells in G1 and G2 phases of the cell cycle show red signals as single spots or doublets, respectively. All nuclei were counterstained with DAPI to verify nuclear integrity before analysis. Scale bar = 5 μm.

The cytotoxicity of the conjugates was evaluated in DU145 cells by an MTS assay. At 1 μM, we observed 66 ± 7% of mortality for TFO2-L4-10CPT 72 h after transfection with Oligofectamine, comparable to free CPT (estimated to 77±13%), while TFO2-ST1968 showed a mortality of 46 ± 12%. It is important to underscore that the conjugates recognize a smaller number of sites compared with CPT; thus, we expected little mortality but still they recognize more than just 1 site. In the case of the rat hepartocarcinoma LFCLI1 cells, the TFO1 conjugates recognized only the IGF-I promoter site and we observed a mortality of ∼40% for the conjugates TFO1-L6-10CPT and TFO1-ST1968, against 75% for CPT alone. However, the cytotoxicity measured is partially due to the transfection process, which is known to be quite toxic for cells (TFOP showed a mortality of 20±6%). By performing colony growth inhibition assays, we tested the effect of the TFO-CPT on the number of colonies and the number of cells per colony that the DU145 cells could make after transfection. The TFO2-L4-CPT and TFO2-ST1968 induced a decrease in the number of colonies (9±2 and 12±8, respectively, compared with 42±3 in nontreated cells) and also in the number of cells per colony. Similarly, TFO2-P decreased also the number of colonies (15±2) and of cells per colony, again indicating a toxicity related to the transfection of the triplex.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated chemotherapeutic agents targeting IGF-I and IGF-IR genes, key genes involved in cancers, including those of the prostate. There is a critical need to develop more effective and efficient treatments for prostate cancer, because of the limited efficacy of the currently available chemotherapies (44). Derivatives of CPT, such as topotecan and irinotecan, are already used in treatment of colon, ovarian, and pediatric cancers (37). Camptothecins induce cell death by binding to the DNA-Top1 complexes, stabilizing them (45,46,47). The main drawback of these molecules is their lack of sequence specificity, which causes numerous harmful side effects. Therefore, it would be useful to develop sequence-specific camptothecins. We and others have clearly demonstrated that a Top1 inhibitor, such as camptothecin or rebeccamycin, coupled to a TFO through a suitable linker can be used to cause site-specific cleavage of the targeted DNA sequence in in vitro models (27, 48) and in cellular transient reporter systems (28). However, the strategy has never been applied to an endogenous target of therapeutic interest. Other studies have demonstrated the cellular efficacy of TFOs conjugated to daunomycin, a Top2 inhibitor, without demonstrating a mechanism via a Top2-mediated DNA cleavage (49,50,51). Thus, a clear demonstration of the mechanism of action in cells of the conjugates of TFOs attached to topoisomerase inhibitors was lacking.

Here we demonstrate that the CPT conjugates were active against 2 genes, IGF-I and IGF-IR. Although attachment of the CPT derivative to the TFO decreased the triplex affinity relative to unconjugated TFO, the 4 CPT-TFO conjugates induced a sequence-specific Top1-mediated DNA cleavage in vitro at a 10-fold lower concentration than the CPT derivatives alone. In addition, these conjugates specifically inhibited gene expression in cells and induced targeted DNA damage.

Notably, the conjugates efficiently inhibited transcription. The chemical characteristics of the conjugates and the optimization of the transfection protocols maximized penetration, and a dose-response effect was observed. In the case of IGF-I, the target sequence was present in the promoter and, by specifically inducing Top1-mediated DNA cleavage in the IGF-I promoter, we successfully reduced the quantity of mRNA transcribed from the regulated gene by 70%. By specifically inducing Top1-mediated DNA cleavage in intron 2 of IGF-IR, we successfully reduced the quantity of mRNA by 70–80%. In the case of the protein, we observed an inhibition of 50%. The use of DU145RC0.1 cells, in which Top1 is mutated and resistant to CPT, allowed us to show that the conjugates acted by recruiting Top1 to the triplex site. A further confirmation derived from the use of the RNA interference to transiently reduce Top1 levels both in the LFCLI1 cells and in the DU145 cells. Moreover, the conjugates were still cytotoxic, even if less than CPT alone, and reduced the number of colonies formed by the DU145 cells. It is important to underscore that the conjugates target the action of CPT to specific sites (here IGF-I and IGF-IR), inducing at these sites DNA damage mediated by Top1. The number of sites is extremely reduced compared with the drug alone, as shown by the visualization of γH2AX foci; however, a strong cytotoxicity is still observed, opening the road to the study of the importance of targeting specifically DNA damage in antitumor strategies and of the number of damages that induce an effect. Notably, Hanahan and Weinberg (52) have reported that cancer cells become dependent on particular features and thus on particular genes that are overexpressed or silenced in cancers.

Notably, not all the multiple sites that are targeted by the TFO2 conjugates in the genome are observed in the immunofluorescence experiments; furthermore, the number of sites observed depends on the cell line (compare the experiments on DU145 cells in Fig. 5 to those on A549 cells in Supplemental Fig. 6). This is probably due to the accessibility of the DNA target (as previously exemplified for TFOs in ref. 42). So it is difficult to establish a clear correlation between spots and the presence of the number of copies of the DNA target.

In summary, the evaluated sequence-specific camptothecins induce a highly specific and efficient Top1-mediated DNA cleavage in rat hepatocarcinoma cells and DU145 cells. An advantage of our strategy compared with other oligonucleotide strategies is that the conjugates TFO2-L6-10CPT and TFO2-ST1968 affect the DNA itself and not the RNA, the product of gene expression. More generally, TFO-based conjugates can be used in a large range of cellular applications, for targeted genome modifications (53), and also in antitumor approaches. The conjugates might constitute a new alternative to currently used drugs, because of their specificity and efficacy. More studies are undergoing to validate their use in tumor models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tiphanie Durfort and Frédéric Chapuis for technical help, Dr. Jean-Louis Mergny and Lucio Merlini for suggestions and useful discussions, Dr. P. Rotwein (Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA) for providing IGF-I plasmids, Christophe Chamot for help with the fluorescence microscopy, and Dr F. Morel (Service de Cytogénétique Cytologie et Biologie de la Reproduction, Center Hospitalier Universitaire Morvan, Brest, France) for providing IGF-IR probes. This work was supported by grants from Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer; a Sigma Tau collaboration grant; a Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health grant to Y.P.; and fellowships to K.O. from Assocation pour la Recherche sur les Tumeurs de la Prostate and Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

References

- Baserga The insulin-like growth factor-I receptor as a target for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:753–768. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev D, Yee D. Disrupting insulin-like growth factor signaling as a potential cancer therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1–12. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani A A, Yakar S, LeRoith D, Brodt P. The role of the IGF system in cancer growth and metastasis: overview and recent insights. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:20–47. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:915–928. doi: 10.1038/nrc2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M, Gupta S, Goldspink G, Winslet M. The insulin-like growth factor system and colorectal cancer: clinical and experimental evidence. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:201–208. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0776-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciampolillo A, De Tullio C, Perlino E, Maiorano E. The IGF-I axis in thyroid carcinoma. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:729–735. doi: 10.2174/138161207780249209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamouzis M V, Papavassiliou A G. The IGF-1 network in lung carcinoma therapeutics. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnik J L, Reichart D B, Huey K, Webster N J, Seely B L. Elevated insulin-like growth factor I receptor autophosphorylation and kinase activity in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1159–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexia C, Fallot G, Lasfer M, Schweizer-Groyer G, Groyer A. An evaluation of the role of insulin-like growth factors (IGF) and of type-I IGF receptor signalling in hepatocarcinogenesis and in the resistance of hepatocarcinoma cells against drug-induced apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1003–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennigens C, Menetrier-Caux C, Droz J P. Insulin-Like Growth Factor (IGF) family and prostate cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;58:124–145. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Abel U, Grobholz R, Hermani A, Trojan L, Angel P, Mayer D. Up-regulation of insulin-like growth factor axis components in human primary prostate cancer correlates with tumor grade. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinbach D S, Lokeshwar B L. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins in prostate cancer: cause or consequence? Urol Oncol. 2006;24:294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti S, Proietti-Pannunzi L, Sciarra A, Lolli F, Falasca P, Poggi M, Celi F S, Toscano V. The IGF axis in prostate cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:719–727. doi: 10.2174/138161207780249128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Girnita A, Girnita L. Role of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signalling in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2097–2101. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann F, Garcia-Echeverria C. Blocking the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor as a strategy for targeting cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1041–1047. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoith D, Helman L. The new kid on the block(ade) of the IGF-1 receptor. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:201–202. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedemann J, Macaulay V M. IGF1R signalling and its inhibition. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:S33–S43. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Pinzi V, Bourhis J, Deutsch E. Mechanisms of disease: signaling of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor pathway–therapeutic perspectives in cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:591–602. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee D. Targeting insulin-like growth factor pathways. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:R7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois J C, Lacoste J, Lacroix L, Mergny J L. Design of antisense and triplex-forming oligonucleotides. Methods Enzymol. 2000;313:74–95. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)13006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo N, Ye J J, Liang S J, Mineo R, Li S L, Giannini S, Plymate S R, Sikes R A, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y. The role of insulin-like growth factor-II in cancer growth and progression evidenced by the use of ribozymes and prostate cancer progression models. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2003;13:44–53. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(02)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada M, Inoue H, Masuda T, Ikeda D. Insulin-like growth factor I secreted from prostate stromal cells mediates tumor-stromal cell interactions of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4419–4425. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y J, Imsumran A, Park M Y, Kwon S Y, Yoon H I, Lee J H, Yoo C G, Kim Y W, Han S K, Shim Y S, Piao W, Yamamoto H, Adachi Y, Carbone D P, Lee C T. Adenovirus expressing shRNA to IGF-1R enhances the chemosensitivity of lung cancer cell lines by blocking IGF-1 pathway. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojan J, Cloix J F, Ardourel M Y, Chatel M, Anthony D D. Insulin-like growth factor type I biology and targeting in malignant gliomas. Neuroscience. 2007;145:795–811. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen J S, Macaulay V M. Targeting the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor as a treatment for cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:589–603. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimondo P B, Bailly C, Boutorine A, Ryabinin V, Syniakov A, Sun J S, Garestier T, Helene C. Directing topoisomerase I-mediated DNA cleavage to specific sites by camptothecin tethered to minor and major groove ligands. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:3045–3048. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010817)40:16<3045::AID-ANIE3045>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimondo P B, Boutorine A, Baldeyrou B, Bailly C, Kuwahara M, Hecht S M, Sun J S, Garestier T, Helene C. Design and optimization of camptothecin conjugates of triple helix- forming oligonucleotides for sequence-specific DNA cleavage by topoisomerase I. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3132–3140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110181200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimondo P B, Thomas C J, Oussedik K, Baldeyrou B, Mahieu C, Halby L, Guianvarc'h D, Lansiaux A, Hecht S M, Bailly C, Giovannangeli C. Exploring the cellular activity of camptothecin-triple-helix-forming oligonucleotide conjugates. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:324–333. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.324-333.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordet O, Khan Q A, Plo I, Pourquier P, Urasaki Y, Yoshida A, Antony S, Kohlhagen G, Solary E, Saparbaev M, Laval J, Pommier Y. Apoptotic topoisomerase I-DNA complexes induced by staurosporine-mediated oxygen radicals. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:50499–50504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohula E A, Salisbury A J, Sohail M, Playford M P, Riedemann J, Southern E M, Macaulay V M. The efficacy of small interfering RNAs targeted to the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF1R) is influenced by secondary structure in the IGF1R transcript. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15991–15997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall L J, Kajimoto Y, Bichell D, Kim S W, James P L, Counts D, Nixon L J, Tobin G, Rotwein P. Functional analysis of the rat insulin-like growth factor I gene and identification of an IGF-I gene promoter. DNA Cell Biol. 1992;11:301–313. doi: 10.1089/dna.1992.11.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignet N, Brun A, Degert C, Delord B, Roux D, Helene C, Laversanne R, Francois J C. The spherulites(TM): a promising carrier for oligonucleotide delivery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3134–3142. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.16.3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urasaki Y, Laco G S, Pourquier P, Takebayashi Y, Kohlhagen G, Gioffre C, Zhang H, Chatterjee D, Pantazis P, Pommier Y. Characterization of a novel topoisomerase I mutation from a camptothecin-resistant human prostate cancer cell line. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1964–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacoste J, Francois J C, Helene C. Triple helix formation with purine-rich phosphorothioate-containing oligonucleotides covalently linked to an acridine derivative. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1991–1998. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.10.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix L, Lacoste J, Reddoch J F, Mergny J L, Levy D D, Seidman M M, Matteucci M D, Glazer P M. Triplex formation by oligonucleotides containing 5-(1-propynyl)-2′-deoxyuridine: decreased magnesium dependence and improved intracellular gene targeting. Biochemistry. 1999;38:1893–1901. doi: 10.1021/bi982290q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallavalle S, Ferrari A, Biasotti B, Merlini L, Penco S, Gallo G, Marzi M, Tinti M O, Martinelli R, Pisano C, Carminati P, Carenini N, Beretta G, Perego P, De Cesare M, Pratesi G, Zunino F. Novel 7-oxyiminomethyl derivatives of camptothecin with potent in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 2001;44:3264–3274. doi: 10.1021/jm0108092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier Y. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:789–802. doi: 10.1038/nrc1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel Y, Lacoste J, Frayssinet C, Sarasin A, Garestier T, Francois J C, Helene C. Inhibition of gene expression by anti-sense C-5 propyne oligonucleotides detected by a reporter enzyme. Biochem J. 1999;339:547–553. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimondo P B, Laco G S, Thomas C J, Halby L, Pez D, Schmitt P, Boutorine A, Garestier T, Pommier Y, Hecht S M, Sun J S, Bailly C. Activation of camptothecin derivatives by conjugation to triple helix-forming oligonucleotides. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4171–4180. doi: 10.1021/bi048031k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekhoff P, Halby L, Oussedik K, Dallavalle S, Merlini L, Mahieu C, Lansiaux A, Bailly C, Boutorine A, Pisano C, Giannini G, Alloatti D, Arimondo P B. Optimized synthesis and enhanced efficacy of novel triplex-forming camptothecin derivatives based on gimatecan. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:666–672. doi: 10.1021/bc800494y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao V A, Agama K, Holbeck S, Pommier Y. Batracylin (NSC 320846), a dual inhibitor of DNA topoisomerases I and II induces histone gamma-H2AX as a biomarker of DNA damage. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9971–9979. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macris M A, Glazer P M. Transcription dependence of chromosomal gene targeting by triplex-forming oligonucleotides. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3357–3362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong A, Kong M, Ma Z, Qian J, Cheng H, Xu X. Knockdown of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor enhances chemosensitivity to cisplatin in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2008;40:497–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2008.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arianayagam M, Chang J, Rashid P. Chemotherapy in the treatment of prostate cancer–is there a role? Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36:737–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster D A, Palle K, Bot E S, Bjornsti M A, Dekker N H. Antitumour drugs impede DNA uncoiling by topoisomerase I. Nature. 2007;448:213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature05938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand C, Antony S, Kohn K W, Cushman M, Ioanoviciu A, Staker B L, Burgin A B, Stewart L, Pommier Y. A novel norindenoisoquinoline structure reveals a common interfacial inhibitor paradigm for ternary trapping of the topoisomerase I-DNA covalent complex. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:287–295. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staker B L, Hjerrild K, Feese M D, Behnke C A, Burgin A B, Jr, Stewart L. The mechanism of topoisomerase I poisoning by a camptothecin analog. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242259599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matteucci M, Lin K-Y, Huang T, Wagner R, Sternbach D D, Mehrotra M, Besterman J M. Sequence-specific targeting of duplex DNA using a camptothecin-triple helix forming oligonucleotide conjugate and topoisomerase I. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:6939–6940. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone G M, McGuffie E, Napoli S, Flanagan C E, Dembech C, Negri U, Arcamone F, Capobianco M L, Catapano C V. DNA binding and antigene activity of a daunomycin-conjugated triplex-forming oligonucleotide targeting the P2 promoter of the human c-myc gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2396–2410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli S, Negri U, Arcamone F, Capobianco M L, Carbone G M, Catapano C V. Growth inhibition and apoptosis induced by daunomycin-conjugated triplex-forming oligonucleotides targeting the c-myc gene in prostate cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:734–744. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stierle V, Duca M, Halby L, Senamaud-Beaufort C, Capobianco M L, Laigle A, Jolles B, Arimondo P B. Targeting MDR1 gene: synthesis and cellular study of modified daunomycin-triplex-forming oligonucleotide conjugates able to inhibit gene expression in resistant cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1568–1577. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg R A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez K M, Narayanan L, Glazer P M. Specific mutations induced by triplex-forming oligonucleotides in mice. Science. 2000;290:530–533. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.