Abstract

Adenosine regulates a wide variety of physiological processes via interaction with one or more G-protein-coupled receptors (A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R). Because A1R occupancy promotes fusion of human monocytes to form giant cells in vitro, we determined whether A1R occupancy similarly promotes osteoclast function and formation. Bone marrow cells (BMCs) were harvested from C57Bl/6 female mice or A1R-knockout mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates and differentiated into osteoclasts in the presence of colony stimulating factor-1 and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand in the presence or absence of the A1R antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentyl xanthine (DPCPX). Osteoclast morphology was analyzed in tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase or F-actin-stained samples, and bone resorption was evaluated by toluidine blue staining of dentin. BMCs from A1R-knockout mice form fewer osteoclasts than BMCs from WT mice, and the A1R antagonist DPCPX inhibits osteoclast formation (IC50=1 nM), with altered morphology and reduced ability to resorb bone. A1R blockade increased ubiquitination and degradation of TRAF6 in RAW264.7 cells induced to differentiate into osteoclasts. These studies suggest a critical role for adenosine in bone homeostasis via interaction with adenosine A1R and further suggest that A1R may be a novel pharmacologic target to prevent the bone loss associated with inflammatory diseases and menopause.—Kara, F. M., Chitu, V., Sloane, J., Axelrod, M., Fredholm, B. B., Stanley, R., Cronstein, B. N. Adenosine A1 receptors (A1Rs) play a critical role in osteoclast formation and function.

Keywords: P1 receptors, osteoporosis

Bone loss is a major public health problem that most often affects postmenopausal women and patients undergoing long-term treatment with glucocorticoids (1). The bone loss in many important skeletal disorders, such as osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, hypercalcemia of malignancy, and bone metastases, results at least in part from increased osteoclast activity (2). Osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells (MNCs) belonging to the monocyte/macrophage family (3,4,5,6,7) that are responsible for bone resorption and play a crucial role in bone remodeling. They differentiate from precursors under the influence of 2 requisite cytokines, colony stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1; also known as macrophage colony stimulating factor), and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) (8). Whereas increased osteoclast formation or function leads to accelerated bone resorption and may lead to osteoporosis or osteolysis, diminished osteoclast formation or function leads to the formation of overly mineralized bone, osteopetrosis. Most clinical bone diseases result from a slower rate of bone formation than resorption over time, and most currently available therapies for osteoporosis inhibit osteoclast formation or activity. There is, however, a clear need for novel therapeutic agents for patients who do not respond to or tolerate currently available agents.

Adenosine, the metabolic product of adenine nucleotide dephosphorylation, is generated intracellularly and extracellularly from the catabolism of adenine nucleotides and is present in the extracellular space, where it regulates a variety of physiological processes via interaction with specific cell surface receptors. Adenosine receptors are members of the large superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors. Four subtypes are currently recognized: A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 receptors, which are present in virtually every tissue (9). We have previously reported that, among other effects, adenosine A1 receptor (A1R) stimulation promotes multinucleated giant cell formation by human peripheral blood monocytes (10). Moreover, we have found that deletion or blockade of adenosine A1Rs leads to increased bone density and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss without affecting bone formation (11).

Because adenosine A1R activation promotes human multinucleated giant cell formation, and osteoclasts are multinucleated giant cells formed from myeloid precursors, we determined whether adenosine A1Rs similarly regulate osteoclast formation or function. Here we identify adenosine and its A1Rs as essential factors in the regulation of osteoclast maturation and function. Using gene-targeted mice, we show that A1 blockade or deficiency leads to decreased numbers of functionally diminished osteoclasts. In addition, we provide evidence for impaired osteoclast terminal differentiation in vitro. These results suggest a novel role for adenosine A1Rs in osteoclast maturation/function and bone remodeling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Recombinant mouse RANKL and CSF-1 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). We purchased 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentyl xanthine (DPCPX) for in vivo studies from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada). Lymphocyte separation medium (LSM) was purchased from Fisher (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA). α-MEM (Cambrex Bio Science, East Rutherford, NJ, USA) was used for all incubations, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Mouse IgG anti-TRAF6 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Animals

A1R-knockout (A1KO) mice were a gift of Dr. Bertil Fredholm (Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden) and have previously been described in detail (12). Female A1KO mice were bred onto a C57BL/6 background (>10 backcrosses) in the New York University School of Medicine (NYU SoM) Animal Facility. All protocols were approved by the NYU SoM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from wild-type (WT) bone marrow cells (BMCs), splenocytes, RAW264.7 macrophages, and osteoclasts derived from bone marrow. Cells were plated on 24-well plates. After the cultured cells became confluent in tissue culture flasks, cells were lysed in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Paisley, UK), and total RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First, single-stranded complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from total RNA from each sample using a cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) in a volume of 50 μl, followed by amplification of specific cDNAs with specific primers. Each cycle consisted of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C and 30 s of annealing and 30 s of extension at 72°C. To generate products corresponding to mRNA-encoding adenosine receptors in mice, gene products for adenosine receptors A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 and GAPDH mRNAs were assessed by RT-PCR for 30 cycles. The following sequences of primers were used: GAPDH, sense 5′-CTACACTGAGGACCAGGTTGTCT-3′ and antisense GGTCTGGGATGGAAATTGTG; A1, sense 5′-CCTGCTTCTGTTTCCCAAAG-3′ and antisense 5′-CCACAAGGGAGAGAATCCAG-3′; A2A, sense 5′-AGCCAGGGGTTACATCTGTG-3′ and antisense 5′-TACAGACAGCCTCGACATGTG-3′; A2B, sense 5′-CAAGTGGGTGATGAATGTGG-3′ and antisense 5′-TTTCCGGAATCAATTCA- AGC-3′; A3, sense 5′-ACTTCTGGGCAGAAGTCTGACAAG and antisense 5′-TTCGTCAACCCTGTTACCTGACTG-3′. All primers were designed to cross an intron.

Osteoclast differentiation from BMCs

BMCs were isolated from 6- to 8-wk-old female C57BL/6 or A1KO mice. Femora and tibiae were aseptically removed and dissected free of adherent soft tissues. The bone ends were cut, and the marrow cavity was flushed out with α-MEM from one end of the bone using a sterile 21-gauge needle. The bone marrow was carefully dispersed by pipetting with a plastic Pasteur pipette to obtain a single-cell suspension. The cells were washed twice and resuspended (3×105 cells/ml) in α-MEM containing 10% FBS, and this suspension was added to 24-well plates (500 μl/well). All cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. At d 3, nonadherent cells were removed, the adherent monolayer was washed with PBS, and the adherent bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) were harvested following a 10-min incubation in 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen) on ice. Cells were then centrifuged, resuspended in α-MEM, and counted, and equal numbers of viable cells were replated in α-MEM with 10% FCS, 30 ng/ml CSF-1, and 100 ng/ml RANKL on either tissue culture plates or glass or dentine coverslips for osteoclast formation. Cultures were fed every third day by replacing 500 μl of culture medium with an equal quantity of fresh medium and reagents. After incubation for 7 d, wells were prepared for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining by rinsing the cultures with PBS and fixation in 4% PFA in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, followed by staining for TRAP for 1 h at 37°C. The staining solution was then removed and replaced with PBS. The number of TRAP-positive MNCs containing ≥3 nuclei was scored (13).

Spleen cell cultures

In some experiments, splenic osteoclast precursors were studied. Splenic cells were isolated from 5- to 8-wk-old female C57BL/6, 129S/v WT, or adenosine A1KO mice as described previously, with the following modifications (14, 15). The spleen was placed on top of a 100-μm cell strainer in a 50-ml falcon tube and mashed with a plunger, and the released cells were rinsed through the strainer with 8 ml PBS. The cells that did not adhere to the strainer were layered on top of LSM and centrifuged at 1500 g for 20 min. The macrophage/lymphocyte band was located ∼1 cm below the top of the LSM. The PBS was aspirated until 1 ml above the band, then 1 ml of separation medium including the band was diluted with 19 ml of PBS and centrifuged at 1500 g for 15 min. PBS was removed, and 10 ml of αMEM was added. The cells were counted and resuspended (4×105 cells/ml) in αMEM containing 10% FBS. This suspension was added to 24-well plates (500 μl/well) (14,15,16).

Morphological characterization of cultured osteoclasts

Osteoclasts were generated from BMCs extracted from the femurs and tibiae of 3 WT and 3 A1KO mice in stromal cell-free cultures using standard methods described previously (17, 18). Briefly, BMCs were grown in Petri dishes in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 100ng/ml CSF-1 for 3 d. The adherent BMMs were used as osteoclast precursors. To differentiate osteoclasts, BMMs were harvested and replated at 7500 cells/ml in either fibronectin-coated glass coverslips or tissue culture plates (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in α-MEM with 10% FCS, 30 ng/ml CSF-1, and 100 ng/ml RANKL, in triplicate, in the presence or absence of the adenosine A1 antagonist DPCPX. After 6 d in culture, cells plated on glass were fixed and stained fluorescently with Alexa 555 Phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and DAPI as described previously (19). To evaluate osteoclast morphology, averages of 400 osteoclasts were examined in each sample. To evaluate the osteoclast height, the distance between the basolateral membrane (top of the cell) and the ruffled border (bottom of the cell, facing the bone) of cells plated on dentin was measured using confocal microscopy.

In vitro bone resorption and osteoclast differentiation assay

Osteoclast precursors from WT and A1KO cells were cultivated on whale dentin slices (Immunodiagnosyic Systems, Fountain Hills, AZ, USA) for 6 d in the presence of 30 ng/ml CSF-1 and 100 ng/ml RANKL, with a change of medium at d 3. Cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature and TRAP stained. In some experiments, cells were removed with sodium hypochlorite, and the resorptive pits were stained with toluidine blue and analyzed by light microscopy.

Western blots of TRAF6

The levels of TRAF6 were evaluated by Western blotting of whole-cell lysates prepared from RANKL-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells treated with medium alone, RANKL (50 ng/ml), or RANKL plus DPCPX (1 μM) for 30 min. Cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed with 1% Nonidet P-40-containing lysis buffer. Proteins were separated by electrophoresis through 10% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and exposed to anti-TRAF6 murine monoclonal antibodies. Western blots were developed and visualized, as we have previously described (20).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance for differences between groups was determined by use of ANOVA or Student’s t test. All statistics were calculated using GraphPad® software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Expression of adenosine receptors

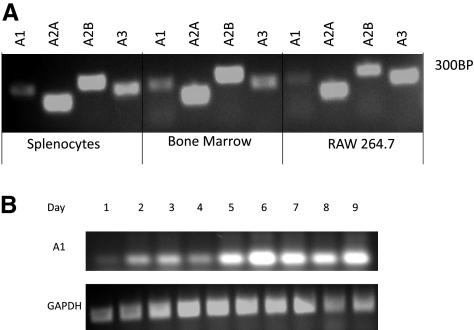

The mRNAs for all 4 adenosine receptor subtypes were expressed in murine BMCs and splenocytes from WT animals as well as in murine monocytic cell line RAW264.7, as assessed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1A). A1R is highly expressed in hematopoietic cells, including BMMs. Its expression, detected by RT-PCR, appeared to be up-regulated during osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 1B). However, the role of A1R in osteoclast differentiation and function is unclear. To address this question we examined the effects on pharmacological inhibition or targeted deletion of A1R on osteclastogenesis in vitro.

Figure 1.

mRNA for all 4 adenosine receptor subtypes is expressed in osteoclasts and their precursors. A) Total RNA was isolated from murine BMCs, splenocytes, and RAW264.7 cells, reversed transcribed, and subjected to RT-PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. Message for all 4 adenosine receptors was detected in all cell types studied. B) Adenosine A1R expression in WT bone marrow-derived macrophages induced to differentiate into osteoclasts was examined by RT-PCR at indicated time points. GAPDH is shown as a loading control.

Osteoclast precursors from adenosine A1KO mice have reduced capacity to differentiate into osteoclasts in vitro

Previous studies have demonstrated that A1Rs play an important role in the formation of multinuclear giant cells from human peripheral blood monocytes (10). To determine whether they play a similar role in osteoclast formation, we compared the capacity of BMMs from WT and adenosine A1KO mice to form multinucleated osteoclasts in response to RANKL and CSF-1 in vitro. BMMs from 3 WT and 3 A1KO mice were exposed to CSF-1 and RANKL for 7 d to induce osteoclastic differentiation. Cultures of A1KO BMMs formed significantly fewer TRAP-positive cells than WT counterparts, although there was no loss of precursor cells from the cultures (Fig. 2). In addition, while WT cultures formed large TRAP-positive cells that displayed the typical spread and multinucleated characteristics of in vitro differentiated osteoclasts (Fig. 2A, left panel), A1KO cultures contained only smaller, poorly spread TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (Fig. 2A, right panel). These data suggest the hypothesis that A1R deficiency is associated with a defect in CSF-1 and RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis in vitro.

Figure 2.

A1KO BMCs generate fewer, morphologically altered osteoclasts in vitro. A) BMCs were induced to differentiate into osteoclasts in the presence of CSF-1 and RANKL for 6 d, fixed, and stained for TRAP. Osteoclastic cells from A1KO mice are less intensely TRAP+ and much smaller and contain fewer nuclei than control osteoclasts. B) Quantitative evaluation of osteoclast differentiation in A1KO and WT BMC cultures.

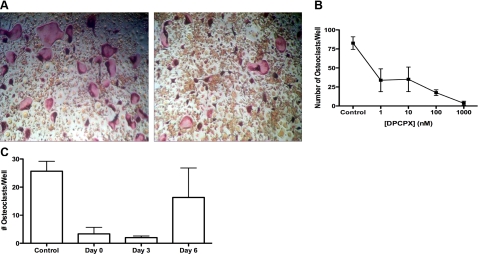

DPCPX, a selective adenosine A1R antagonist, inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro

To eliminate the possibility that developmental defects are responsible for the poor formation of A1-deficient osteoclasts from bone marrow precursors in vitro, we determined whether exogenous or endogenously released adenosine regulates osteoclast formation in vitro. If low levels of endogenously generated adenosine acting at A1Rs are necessary for osteoclast formation, then the highly selective and potent adenosine A1R antagonist, DPCPX (>1000 references to date; see http://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed&cmd= DetailsSearch&term=dpcpx+A1+receptor&log$= activity) is expected to block osteoclastogenesis. In the presence of DPCPX, significantly fewer osteoclasts form from precursors, and the osteoclasts that do form are smaller and do not spread, findings nearly identical to those observed in the cells from A1KO mice (Fig. 3A, B). A DPCPX concentration of 1 nM was sufficient to significantly inhibit osteoclast formation, and almost complete inhibition was seen at a DPCPX concentration of 1 μM. These concentrations fall within the range required to inhibit adenosine A1R function (21). Identical results were obtained with splenic osteoclast precursors and RAW264.7 cells (data not shown). Again, there was no reduction in the number of undifferentiated precursor cells in the cultures treated with DPCPX (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

A1R antagonist DPCPX inhibits osteoclast development. BMCs from WT mice were induced to differentiate to osteoclasts by culture in CSF-1 and RANKL in the presence or absence of various concentrations of DPCPX. After 7 d, cells were fixed and stained for TRAP, and the number of MNCs per well was quantitated. A) DPCPX (1 mM) inhibits CSF-1 and RANKL-induced formation of TRAP-positive MNCs; representative photomicrographs (×200) of cells cultured for 7 d in the presence of RANKL and DPCPX. B) DPCPX inhibits osteoclast formation in a dose-dependent fashion. Average ± sem value of TRAP + MNCs/control well was 248 ± 24. Each point represents results of ≥3 separate determinations carried out in triplicate with BMCs from different mice. *P < 0.05; ANOVA. C) Osteoclast precursors were induced to differentiate, and DPCPX was added to the culture on d 0, 3, and 6 after addition of RANKL to cultures. All cultures were fixed and stained after 7 d of incubation in the presence of RANKL. Each point represents 3 determinations carried out with BMCs from different mice in triplicate.

To determine the developmental stage at which DPCPX inhibited osteoclast differentiation, osteoclast precursors were incubated with CSF-1 and RANKL, and DPCPX was added to cultures on d 0, 3, or 6 before harvesting the cells on d 7. DPCPX inhibited osteoclast formation when added at d 0, but inhibition decreased when DPCPX addition was delayed (Fig. 3C), suggesting that adenosine A1 blockade targets early events in osteoclast differentiation. In contrast, the selective adenosine A1R agonist N6cyclopentyladenosine did not significantly increase osteoclast number (data not shown).

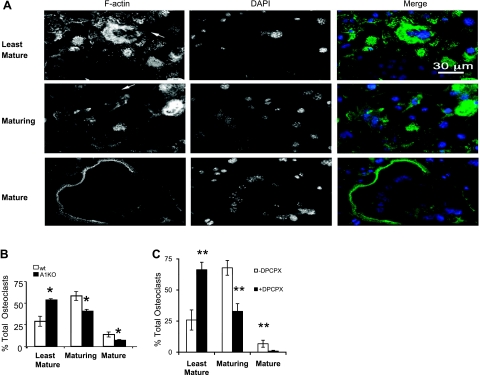

A1R is required for osteoclast differentiation and function in vitro

Both A1R deficiency and the pharmacologic inhibition of A1R led to the development of fewer, morphologically altered osteoclasts (Figs. 2 and 3). This phenotype could be due to defects in the osteoclast precursors, to defects in spreading due to inappropriate remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton, or both. We therefore studied the effects of A1R on actin ring formation in osteoclasts cultured on glass coverslips and visualized by confocal microscopy. Osteoclasts cultured on glass exhibit 3 distinct morphologies; Fig. 4A, top panel, shows the least mature osteoclasts, which may represent an early stage in osteoclast differentiation; these are generally small with <5 nuclei centrally located and surrounded by a ring of F-actin. Podosomes are usually absent in these cells. Figure 4A, middle panel, shows maturing osteoclasts, which are variable in size, dendritic shaped, and contain >5 nuclei distributed throughout the cytoplasm; their podosomes are located in patches at the edge of each pseudopod. These osteoclasts may represent fusion intermediates because they are often connected with other maturing cells through cytoplasmic bridges (Fig. 4A, middle panel, arrow). The bottom panel in Fig. 4A shows mature osteoclasts, which are large with numerous nuclei located at the periphery near the peripheral podosome belt. Interestingly, the proportion of least-mature osteoclasts is substantially increased in A1KO cultures, whereas maturing and mature osteoclasts are significantly decreased (Fig. 4B). We observed a similar maturation defect in osteoclasts that formed in the presence of DPCPX (Fig. 4C), and there were fewer nuclei per osteoclast in the presence of DPCPX (5.3+0.2 vs. 7.2+1.1 nuclei/osteoclast, n=12, P<0.02). These data further confirm that the A1R plays an important role in osteoclast fusion and differentiation.

Figure 4.

Abnormal phenotype of osteoclasts formed from A1KO mouse bone marrow precursors. BMCs were cultured on glass coverslips and treated with CSF-1 and RANKL with or without DPCPX (1 mM), as described in Materials and Methods. F-actin was detected by Alexa 555-Phalloidin staining, and nuclei were labeled with DAPI. A) Morphology of the least mature (arrow indicates osteoclast), maturing (arrow indicates cytoplasmic bridge), and mature osteoclasts cultured on glass. B) Quantitative evaluation of number of least mature, maturing, and mature osteoclasts in WT and A1KO cultures. C) Quantitative evaluation of the number of least mature, maturing, and mature osteoclasts in BMC cultures treated or not with DPCPX (1 mM). Data represent mean ± sd proportion of different types of osteoclasts. *P < 0.05 vs. WT, **P < 0.01 vs. DPCPX; ANOVA.

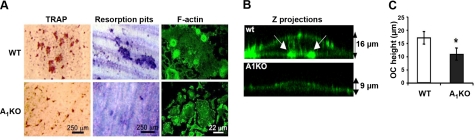

A1R deficiency leads to defective bone resorption in vitro

To investigate whether A1KO osteoclasts are functional, we next examined their morphology and bone resorptive capacity when cultured on dentin slices. Consistent with the morphology of cells plated on plastic or glass, A1KO cells plated on dentin developed fewer and smaller TRAP-positive cells (Fig. 5A, left panels) that excavated smaller bone resorptive pits stained by toluidine blue (Fig. 5A, center panels). Osteoclasts express several characteristic features, such as a highly polarized morphology (22), either in vitro or in bone tissue. They strongly adhere to the substrate, which they break down in a tightly closed zone marked by a sealing zone surrounded by an actin ring (23). This zone delineates a domain located extracellularly in which lysosomal enzymes and protons are secreted, allowing the targeted resorption of bone and extracellular matrix (24).

Figure 5.

Osteoclasts from A1KO mice cultured on dentin form abnormal actin rings and resorb less bone. A) Osteoclast formation on dentin coverslips (left panels) and bone resorption (center panels) by WT and A1KO-deficient cells were visualized by TRAP and toluidine blue staining, respectively. Morphology of the actin cytoskeleton was evaluated in Alexa 555-Phalloidin-stained samples (right panels). B) Cross-sections through 3-dimensional projections of WT and A1KO osteoclasts grown on dentin coverslips and labeled with Alexa 555-Phalloidin were visualized by confocal microscopy. Arrows indicate borders of the sealing zone. C) Osteoclast height was determined by confocal microscopy as mean ± sd distance from dentin surface to apex of dorsal membrane of osteoclasts (n=12 cells/genotype, samples from 3 mice). *P < 0.05; Student’s t test.

When plated on dentin slices, osteoclasts obtained from WT mice developed strong sealing zones, indicated by the presence of F-actin rings (Fig. 5A, right panels; B, arrows). In contrast, A1KO osteoclasts failed to form F-actin rings (Fig. 5A). Instead, F-actin was distributed in patches throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 5B). To evaluate whether the inability of A1KO osteoclasts to generate actin rings leads to nonpolarized and hence dysfunctional osteoclasts, we measured the distance between the basolateral membrane facing the marrow space and the ruffled border (osteoclast height), which is used as an index for osteoclast polarization (25). A1KO osteoclasts showed significantly reduced height compared with WT osteoclasts (Fig. 5B, C), indicating defective osteoclast polarization. Taken together, these data indicate an essential role for A1R in osteoclast fusion, actin cytoskeleton remodeling, and bone resorption in vitro. Consistent with this observation, in an independent study we observed that A1KO osteoclasts also fail to form ruffled borders in vivo (11). These results suggest that disrupted actin cytoskeletal organization in A1KO osteoclasts may be responsible for the morphological and functional defects observed in vitro and in vivo.

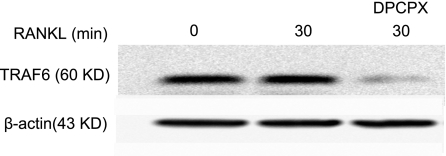

Adenosine A1R blockade results in loss of cellular TRAF6

The observation that in A1KO mice osteoclast differentiation is defective in vitro (Figs. 2345), whereas the number and histological appearance of osteoclasts does not appear to be affected in vivo (11), is reminiscent of observations made in TRAF6 KO mice (8, 26, 27). During osteoclastogenesis, RANKL stimulates its receptor, RANK, which recruits adapter proteins of the TRAF family, leading to activation of NF-κB and Jun N-terminal kinase pathways (28). Among TRAF family members, TRAF6 is thought to be the most critical in RANKL signaling, as demonstrated by the osteopetrotic phenotype of TRAF6−/− mice despite the apparently normal number and appearance of osteoclasts in these mice (8, 26, 27). To further assess whether regulation of TRAF6 expression contributes to the A1R-mediated suppression of osteoclastogenesis in vitro and osteoclast function in vitro and in vivo, we stimulated RAW264.7 cells for 30 min with RANKL in the presence or absence of DPCPX. As shown in Fig. 6, treatment with DPCPX induced significant TRAF6 loss (58±25% reduction of TRAF6, P<0.05, n=6).

Figure 6.

Effect of A1R blockade on intracellular signaling in osteoclasts. RAW 264.7 cells were incubated for 3 d, washed, and stimulated with RANKL for 30 min in the presence or absence of DPCPX, as described. Cells were lysed, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon membranes for blotting with anti-TRAF6 antibody. Blots were stripped and blotted with β-actin antibody (loading control). Representative experiment from 6 discrete experiments is shown.

DISCUSSION

Osteoclasts play a critical role in osteoporosis and in bone loss associated with inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Indeed, osteoclasts are targets for bisphosphonates and, indirectly, for agents targeting RANKL. We have found that both the deletion and the blockade of adenosine A1Rs prevent bone loss in a murine model for postmenopausal osteoporosis following ovariectomy (11), underscoring the potential therapeutic importance of the effects described here. This is the first study to demonstrate that A1R deletion or blockade inhibits the differentiation of osteoclast-like cells from bone marrow precursors. Because the effects of A1R deletion and pharmacologic blockade with DPCPX on osteoclast formation are identical, this provides strong and self-reinforcing evidence that the A1R plays a critical role in osteoclast differentiation. Moreover, A1R blockade inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast formation at an early stage. Similarly, the formation of a sealing zone delineated by an actin ring is essential for bone resorption (29, 30), and A1KO osteoclasts form poor actin rings and, as a consequence, have diminished capacity to resorb bone. Collectively, these results indicate that A1R deficiency impairs osteoclastogenesis and leads to generation of morphologically and functionally deficient osteoclasts.

Adenosine is present in nearly all body fluids, and its concentration is tightly regulated. Adenosine may be produced intracellularly from the catabolism of adenine nucleotides or, as appears to be the greater source of endogenous adenosine, the extracellular dephosphorylation of adenine nucleotides by ectoenzymes (31,32,33,34). Adenosine itself has a very short half-life in biological fluids because of its rapid deamination to inosine, which is inactive at most adenosine receptors, and/or cellular uptake and rephosphorylation to adenine nucleotides (33, 34). Extracellular adenosine concentrations may increase at sites of rapid cellular turnover and under conditions of hypoxia or other forms of cellular stress (35,36,37,38). Moreover, neutrophils have been shown to secrete adenine nucleotides that are converted to adenosine extracellularly in response to chemotactic stimuli and that act locally to promote chemotaxis (39,40,41). Thus, it is likely that other receptor-ligand interactions may stimulate a similar local increase in adenosine concentration as well (42). In bone, the presumed source of adenosine is the large number of rapidly proliferating cells, although osteoclasts and osteoblasts likely also release physiologically active adenosine concentrations (43).

Previous studies (43) have indicated that adenosine stimulates the production of interleukin-6 and inhibits osteoprotegerin production by osteoblasts, effects that should enhance osteoclast function, via adenosine A2B receptors, although other researchers have not observed adenosine-mediated effects on osteoblast function (44). When studied in vivo, we found no evidence for a change in osteoblast number, morphology, or function in adenosine A1R-deficient mice or following ingestion of a selective adenosine A1R antagonist (11).

Crosstalk between adenosine receptors and cytokine receptors plays a strong role in regulating inflammatory responses, and inflammatory cytokines regulate adenosine receptor expression and function (45,46,47). A report by Takanayaki et al. (48) indicates that interferon-γ inhibits osteoclast formation by promoting the ubiquitination and proteolysis of TRAF6, effects similar to loss or depletion of adenosine A1Rs. Thus, one explanation for adenosine receptor-mediated promotion of osteoclast formation is that adenosine A1Rs enhance interferon-γ production or responses in osteoclast precursors. Alternatively, the effects of interferon-γ on osteoclast formation may be mediated by stimulation of adenosine release and activation of A1Rs.

Note that our results are consistent with the hypothesis that adenosine A1R activation is required to prevent the degradation of TRAF6, a critical signaling molecule in osteoclasts. Prior observations indicate differing effects of TRAF6 deletion on osteoclast number and morphology in vivo; it has been reported by Lomaga and colleagues (16) that TRAF6-deficient mice have normal numbers of multinucleated osteoclasts in their bones with apparently reduced function, but others have observed diminished numbers of osteoclasts associated with bone (16, 26). One explanation for the different observations by these 2 groups is that osteoclasts may form in a TRAF6-independent fashion following stimulation by TNF-α in the presence of other signaling molecules, such as TGF-β (41). The osteopetrosis observed when A1Rs were deleted (11) was not nearly as severe as that observed in the absence of TRAF6, a finding that may be due to the presence of residual TRAF6 in the osteoclasts of A1KO mice, leading to a less severe phenotype.

Adenosine A1Rs are expressed on many different cell types and classically signal via pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi proteins (49). Adenosine A1Rs may also signal via G15/G16 (50,51,52), a G protein expressed nearly exclusively in cells of hematopoietic origin (53) that is not inhibited by pertussis toxin treatment. There are clear overlaps in the signaling from these 2 different G proteins, and there are redundancies in the signaling pathways triggered via these G proteins and via TRAF6. For example, signaling from A1Rs has previously been shown to activate NFκB via phospholipase C-γ-mediated activation of protein kinase C and via c-Src. Moreover, adenosine A1Rs in excitable tissue directly activate a KATP channel (54,55,56,57,58), and osteoclasts express a number of ion channels (59,60,61,62) that regulate their function. Thus, adenosine A1Rs may signal for diminished TRAF6 ubiquitination by any of these mechanisms.

An alternative mechanism by which A1Rs regulate osteoclast function is suggested by parallels to calcitonin receptors. Similar to adenosine receptors, calcitonin receptors can be coupled to the cAMP pathway via activating (Gs) and inhibitory (Gi) G proteins and also to the protein kinase C pathway. Calcitonin inhibits both osteoclast formation and bone resorption (63). Like calcitonin, the cell-permeant cAMP analog dibutyryl cAMP and agents that activate adenylyl cyclase (forskolin and cholera toxin) have been reported to inhibit osteoclast motility and induce retraction (64). Moreover, both calcitonin and dibutyryl cAMP lead to disintegration of the actin ring in resorbing osteoclasts. In contrast, Moonga et al. (65) found that relatively low concentrations of dibutyryl cAMP inhibited motility but did not induce osteoclast retraction, whereas relatively high concentrations of the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin induced retraction but did not affect motility. These observations led to the suggestion that cAMP mediates the effect of calcitonin on osteoclast motility, whereas elevation of [Ca2+]i mediates retraction (64). The adenosine A1R inhibits activation of adenylyl cyclase (66), and an alternative explanation for our findings is that blockade of adenosine A1R permits cAMP accumulation and downstream signals that inhibit osteoclast maturation and bone resorption.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kevin McHugh (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA) for providing the RAW264.7 cell line. This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (AR54897, AR41911, and AA13336 to B.N.C.; RO1 CA25604 to E.R.S.; and K01 AR054486-02 to V.C.), the NYU-HHC Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1RR029893), a New York Community Trust blood diseases grant (V.C.), the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Cancer Center (P30 CA13330; to E.R.S.), and the Kaplan Cancer Center of New York University School of Medicine. In addition, the Musculoskeletal Repair and Regeneration Core Center at the Hospital for Special Surgery (AR046121) provided technical assistance. B.N.C. holds or has filed applications for patents on the use of adenosine A2AR agonists to promote wound healing and use of A2AR antagonists to inhibit fibrosis; use of adenosine A1R antagonists to treat osteoporosis and other diseases of bone; use of adenosine A1R and A2BR antagonists to treat fatty liver; and use of adenosine A2AR agonists to prevent prosthesis loosening. Consultancies (within past 2 yr): King Pharmaceutical (licensee of patents on wound healing and fibrosis above), CanFite Biopharmaceuticals, Savient Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche Pharmaceuticals, Cellzome, Tap (Takeda) Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus Laboratories, Regeneron (Westat, DSMB), Sepracor, Amgen, Endocyte, Protalex, Allos, Inc., Combinatorx, Kyowa Hakka. Honoraria/speaker bureaus: Tap (Takeda) Pharmaceuticals. Stock: CanFite Biopharmaceuticals, received for membership on Scientific Advisory Board.

References

- Finkelstein J S, Dawson-Hugues B. Osteoporosis. Goldman L, Bennett J C, editors. Philadelphia: Saunders; Cecil Textbook of Medicine. (21st ed) 2000:1366–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Rodan G A, Martin T J. Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science. 2000;289:1508–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda T, Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Jimi E, Gillespie M T, Martin T J. Modulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the new members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and ligand families. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:345–357. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsenty G, Wagner E F. Reaching a genetic and molecular understanding of skeletal development. Dev Cell. 2002;2:389–406. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolagas S C. Birth and death of bone cells: basic regulatory mechanisms and implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:115–137. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Z H, Kim H H. Signal transduction by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B in osteoclasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Tanaka S, Murakami H, Owan I, Tamura T, Suda T. Postmitotic osteoclast precursors are mononuclear cells which express macrophage-associated phenotypes. Dev Biol. 1994;163:212–221. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum S L. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B B, Ap I J, Jacobson K A, Klotz K N, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill J T, Shen C, Schreibman D, Coffey D, Zakharenko O, Fisher R, Lahita R G, Salmon J, Cronstein B N. Adenosine A1 receptor promotion of multinucleated giant cell formation by human monocytes: a mechanism for methotrexate-induced nodulosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arth Rheum. 1997;40:1308–1315. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199707)40:7<1308::AID-ART16>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara F M, Doty S B, Boskey A, Goldring S, Zaidi M, Cronstein B N. Adenosine A1R blockade or deletion increases bone density and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Arth Rheum. 2010;62:534–541. doi: 10.1002/art.27219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B, Halldner L, Dunwiddie T V, Masino S A, Poelchen W, Gimenez-Llort L, Escorihuela R M, Fernandez-Teruel A, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu X J, Hardemark A, Betsholtz C, Herlenius E, Fredholm B B. Hyperalgesia, anxiety, and decreased hypoxic neuroprotection in mice lacking the adenosine A1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9407–9412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161292398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Goto M, Mochizuki S I, Tsuda E, Morinaga T, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Suda T, Higashio K. A novel molecular mechanism modulating osteoclast differentiation and function. Bone. 1999;25:109–113. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sells Galvin R J, Gatlin C L, Horn J W, Fuson T R. TGF-beta enhances osteoclast differentiation in hematopoietic cell cultures stimulated with RANKL and M-CSF. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265:233–239. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Lorenzo J A, Freeman A M, Tomita M, Morham S G, Raisz L G, Pilbeam C C. Prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 is required for maximal formation of osteoclast-like cells in culture. J Clin Investig. 2000;105:823–832. doi: 10.1172/JCI8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomaga M A, Yeh W C, Sarosi I, Duncan G S, Furlonger C, Ho A, Morony S, Capparelli C, Van G, Kaufman S, van der Heiden A, Itie A, Wakeham A, Khoo W, Sasaki T, Cao Z, Penninger J M, Paige C J, Lacey D L, Dunstan C R, Boyle W J, Goeddel D V, Mak T W. TRAF6 deficiency results in osteopetrosis and defective interleukin-1, CD40, and LPS signaling. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1015–1024. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.8.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani M R, Fuller K, Kim N S, Choi Y, Chambers T. Prostaglandin E2 cooperates with TRANCE in osteoclast induction from hemopoietic precursors: synergistic activation of differentiation, cell spreading, and fusion. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1927–1935. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers T J, Owens J M, Hattersley G, Jat P S, Noble M D. Generation of osteoclast-inductive and osteoclastogenic cell lines from the H-2KbtsA58 transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5578–5582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitu V, Pixley F J, Macaluso F, Larson D R, Condeelis J, Yeung Y G, Stanley E R. The PCH family member MAYP/PSTPIP2 directly regulates F-actin bundling and enhances filopodia formation and motility in macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2947–2959. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z, Borea P A, Varani K, Wilder T, Yee H, Chiriboga L, Blackburn M R, Azzena G, Resta G, Cronstein B N. Adenosine signaling contributes to ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. J Clin Investig. 2009;119:582–594. doi: 10.1172/JCI37409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M J, Klotz K N, Lindenborn-Fotinos J, Reddington M, Schwabe U, Olsson R A. 8-Cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX): a selective high affinity antagonist radioligand for A1 adenosine receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1987;336:204–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00165806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann D, Guicheux J, Gouin F, Passuti N, Daculsi G. Cytokines, growth factors and osteoclasts. Cytokine. 1998;10:155–168. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltel F, Destaing O, Bard F, Eichert D, Jurdic P. Apatite-mediated actin dynamics in resorbing osteoclasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5231–5241. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. Molecular mechanisms of bone resorption: an update. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1995;266:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccio R, Teitelbaum S L, Fujikawa K, Chappel J, Zallone A, Tybulewicz V L, Ross F P, Swat W. Vav3 regulates osteoclast function and bone mass. Nat Med. 2005;11:284–290. doi: 10.1038/nm1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito A, Azuma S, Tanaka S, Miyazaki T, Takaki S, Takatsu K, Nakao K, Nakamura K, Katsuki M, Yamamoto T, Inoue J. Severe osteopetrosis, defective interleukin-1 signalling and lymph node organogenesis in TRAF6-deficient mice. Genes Cells. 1999;4:353–362. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzoso G, Carlson L, Xing L, Poljak L, Shores E W, Brown K D, Leonardi A, Tran T, Boyce B F, Siebenlist U. Requirement for NF-kappaB in osteoclast and B-cell development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3482–3496. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong B R, Josien R, Lee S Y, Vologodskaia M, Steinman R M, Choi Y. The TRAF family of signal transducers mediates NF-kappaB activation by the TRANCE receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28355–28359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaananen H K, Horton M. The osteoclast clear zone is a specialized cell-extracellular matrix adhesion structure. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2729–2732. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.8.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakkakorpi P T, Vaananen H K. Kinetics of the osteoclast cytoskeleton during the resorption cycle in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:817–826. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650060806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst M M, Schrader J. Adenine nucleotide release from isolated perfused guinea pig hearts and extracellular formation of adenosine. Circ Res. 1991;68:797–806. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.3.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon P F, Taylor C T, Stahl G L, Colgan S P. Neutrophil-derived 5′-adenosine monophosphate promotes endothelial barrier function via CD73-mediated conversion to adenosine and endothelial A2B receptor activation. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1433–1443. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deussen A, Moser G, Schrader J. Contribution of coronary endothelial cells to cardiac adenosine production. Pflügers Arch. 1986;406:608–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00584028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J D, Gordon J L. Vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells in culture selectively release adenine nucleotides. Nature. 1979;281:384–386. doi: 10.1038/281384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meininger C J, Schelling M E, Granger H J. Adenosine and hypoxia stimulate proliferation and migration of endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H554–H562. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.3.H554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi H, King G L, Ferrara N, Aiello L P. Hypoxia regulates vascular endothelial growth factor receptor KDR/Flk gene expression through adenosine A2 receptors in retinal capillary endothelial cells. Investig Ophthamol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1311–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne R M, Belardinelli L. Effects of hypoxia and ischaemia on coronary vascular resistance, A-V node conduction and S-A node excitation. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1985;694:9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb08795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blay J, White T D, Hoskin D W. The extracellular fluid of solid carcinomas contains immunosuppressive concentrations of adenosine. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2602–2605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito L, Montesinos M C, Schreibman D M, Balter L, Thompson L F, Resta R, Carlin G, Huie M A, Cronstein B N. Methotrexate and sulfasalazine promote adenosine release by a mechanism that requires ecto-5′-nucleotidase-mediated conversion of adenine nucleotides. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:295–300. doi: 10.1172/JCI1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madara J L, Patapoff T W, Gillece-Castro B, Colgan S P, Parkos C A, Delp C, Mrsny R J. 5′-Adenosine monophosphate is the neutrophil-derived paracrine factor that elicits chloride secretion from T84 intestinal epithelial cell monolayers. J Clin Investig. 1993;91:2320–2325. doi: 10.1172/JCI116462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel P A, Junger W G. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitaraman S V, Merlin D, Wang L, Wong M, Gewirtz A T, Si-Tahar M, Madara J L. Neutrophil-epithelial crosstalk at the intestinal lumenal surface mediated by reciprocal secretion of adenosine and IL-6. J Clin Investig. 2001;107:861–869. doi: 10.1172/JCI11783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B A J, Elford C, Pexa A, Francis K, Hughes A C, Deussen A, Ham J. Human osteoblast precursors produce extracellular adenosine, which modulates their secretion of IL-6 and osteoprotegerin. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:228–236. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S J, Gray C, Boyde A, Burnstock G. Purinergic transmitters inhibit bone formation by cultured osteoblasts. Bone. 1997;21:393–399. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoa N D, Montesinos C M, Williams A J, Kelly M, Cronstein B N. Th1 cytokines regulate adenosine receptors and their downstream signalling elements in human microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:3991–3998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoa N D, Montesinos M C, Reiss A B, Delano D, Awadallah N, Cronstein B N. Inflammatory cytokines regulate function and expression of adenosine A2A receptors in human monocytic THP-1 cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:4026–4032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoa N D, Postow M, Danielsson J, Cronstein B N. Tumor necrosis factor-α prevents desensitization of Gαs-coupled receptors by regulating GRK2 association with the plasma membrane. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1311–1319. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.016857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayanagi H, Ogasawara K, Hida S, Chiba T, Murata S, Sato K, Takaoka A, Yokochi T, Oda H, Tanaka K, Nakamura K, Taniguchi T. T-cell-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis by signalling cross-talk between RANKL and IFN-gamma. Nature. 2000;408:600–605. doi: 10.1038/35046102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B B, Arslan G, Halldner L, Kull B, Schulte G, Wasserman W. Structure and function of adenosine receptors and their genes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s002100000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye R D. Regulation of nuclear factor kappaB activation by G-protein-coupled receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:839–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Sang H, Rahman A, Wu D, Malik A B, Ye R D. G alpha 16 couples chemoattractant receptors to NF-kappa B activation. J Immunol. 2001;166:6885–6892. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A M, Wong Y H. G16-mediated activation of nuclear factor kappaB by the adenosine A1 receptor involves c-Src, protein kinase C, and ERK signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53196–53204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatruda T T, 3rd, Steele D A, Slepak V Z, Simon M I. G alpha 16, a G protein alpha subunit specifically expressed in hematopoietic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5587–5591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker A L, Linden J. Cloned receptors and cardiovascular responses to adenosine. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27:62–67. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Huang X, Zhong H, Mortensen R M, D'Alecy L G, Neubig R R. Endogenous RGS proteins and Galpha subtypes differentially control muscarinic and adenosine-mediated chronotropic effects. Circ Res. 2006;98:659–666. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207497.50477.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosche L I, Wellner-Kienitz M C, Bender K, Pott L. G protein-independent inhibition of GIRK current by adenosine in rat atrial myocytes overexpressing A1 receptors after adenovirus-mediated gene transfer. J Physiol. 2003;550:707–717. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart C, Standen N B. Adenosine-activated potassium current in smooth muscle cells isolated from the pig coronary artery. J Physiol. 1993;471:767–786. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Han J, Ho W, Earm Y E. Modulation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in rabbit ventricular myocytes by adenosine A1 receptor activation. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H325–H333. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova S V, Dixon S J, Sims S M. Osteoclast ion channels: potential targets for antiresorptive drugs. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:637–654. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidema A F, Dixon S J, Sims S M. Electrophysiological characterization of ion channels in osteoclasts isolated from human deciduous teeth. Bone. 2000;27:5–11. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(00)00287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker K D, Gay C V. Depolarization of osteoclast plasma membrane potential by 17beta-estradiol. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1861–1866. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.11.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidema A F, Barbera J, Dixon S J, Sims S M. Extracellular nucleotides activate non-selective cation and Ca(2+)-dependent K+ channels in rat osteoclasts. J Physiol. 1997;503:303–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.303bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm S, Lundberg P, Lerner U H. Calcitonin inhibits osteoclast formation in mouse haematopoetic cells independently of transcriptional regulation by receptor activator of NF-{kappa}B and c-Fms. J Endocrinol. 2007;195:415–427. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova S V, Shum J B, Paige L A, Sims S M, Dixon S J. Regulation of osteoclasts by calcitonin and amphiphilic calcitonin conjugates: role of cytosolic calcium. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003;73:265–273. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-1051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moonga B S, Alam A S, Bevis P J, Avaldi F, Soncini R, Huang C L, Zaidi M. Regulation of cytosolic free calcium in isolated rat osteoclasts by calcitonin. J Endocrinol. 1992;132:241–249. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1320241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie T V, Fredholm B B. Adenosine A1 receptors inhibit adenylate cyclase activity and neurotransmitter release and hyperpolarize pyramidal neurons in rat hippocampus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;249:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]