Abstract

Hochu-ekki-to is a traditional herbal (Kampo) medicine that has been shown to be effective for patients with Kikyo (delicate, easily fatigable, or hypersensitive) constitution. Previous case reports have suggested that this herbal drug was effective for a certain subgroup of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD). We aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Hochu-ekki-to in the long-term management of Kikyo patients with AD. In this multicenter, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study, 91 Kikyo patients with AD were enrolled. Kikyo condition was evaluated by a questionnaire scoring system. All patients continued their ordinary treatments (topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, emollients or oral antihistamines) before and after their protocol entry. Hochu-ekki-to or placebo was orally administered twice daily for 24 weeks. The skin severity scores, total equivalent amount (TEA) of topical agents used for AD treatment, prominent efficacy (cases with skin severity score = 0 at the end of the study) rate and aggravated rate (more than 50% increase of TEA of topical agents from the beginning of the study) were monitored and evaluated. Seventy-seven out of 91 enrolled patients completed the 24-week treatment course (Hochu-ekki-to: n = 37, placebo: n = 40). The TEA of topical agents (steroids and/or tacrolimus) was significantly (P < 0.05) lower in the Hochu-ekki-to group than in the placebo group, although the overall skin severity scores were not statistically different. The prominent efficacy rate was 19% (7 of 37) in the Hochu-ekki-to group and 5% (2 of 40) in the placebo group (P = 0.06). The aggravated rate was significantly (P < 0.05) lower in the Hochu-ekki-to group (3%; 1 of 37) than in the placebo group (18%; 7 of 39). Only mild adverse events such as nausea and diarrhea were noted in both groups without statistical difference. This placebo-controlled study demonstrates that Hochu-ekki-to is a useful adjunct to conventional treatments for AD patients with Kikyo constitution. Use of Hochu-ekki-to significantly reduces the dose of topical steroids and/or tacrolimus used for AD treatment without aggravating AD.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, Hochu-ekki-to, Kampo medicine, randomized controlled trial, steroid, tacrolimus, (traditional) herbal medicine

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common, chronic, relapsing eczematous skin disease with severe pruritus (1–3). The incidence of AD appears to be increasing worldwide (4,5), among which the percentage of adolescent- and adult-type AD cases have also been increasing (6,7). The precise pathogenesis of AD remains obscure and appears complex. Topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, emollients and oral antihistamines are used as the first-line treatments in standard therapeutic guidelines for AD (2,3,8). However, long-term application of topical steroids could induce local adverse effects such as skin atrophy and telangiectasia in a substantial number of patients. Topical tacrolimus is a potent calcineurin inhibitor that does not exhibit the hormonal adverse effects associated with steroid therapy (9,10). The major adverse effect in using topical tacrolimus is sensation of skin burning or irritation after application (11). In addition, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a public health advisory to inform healthcare professionals and patients of a potential cancer risk by the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors (http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/2005/ANS01343.html). This concern is based on animal studies, case reports with a small number of patients, or knowledge of the drug's action mechanism as immunosuppressant. According to the FDA statement, it may take human studies of 10 years or longer to determine if the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors is actually linked to cancer development in human. These adverse effects and emotional fear of long-term use of topical steroids and/or tacrolimus have caused topical steroid/tacrolimus phobia in substantial number of patients with AD worldwide who would like to avoid these topical agents if possible (12). Moreover, clinical experience has shown that some of AD patients are really refractory to these conventional treatments, and indeed current AD therapeutic guidelines recommend further intensive treatments such as ultraviolet phototherapy or oral cyclosporine for such patients (8).

In Japan, an alternative approach has been pursued to treat these grave and/or refractory AD patients with traditional herbal medicine such as Saiko-seikan-to, Shohu-san, Oren-gedoku-to, Byakko-ka-ninjin-to, Tokaku-joki-to, Unkei-to, Hochu-ekki-to and so on (13–33). These prescriptions comprise several elemental herbs, combined use of which is thought to help increase the treatment effects and to diminish adverse reactions of each individual herb. Among these prescriptions, formula like Tokaku-joki-to are mainly aimed at eliminating disease factors, whereas Hochu-ekki-to is aimed at correcting abnormal homeostasis of the body. Each prescription is selected individually according to the pharmacological features and the constitution of each patient. Hochu-ekki-to is composed of hot water extracts from 10 species of herbal plants and is used for patients with Kikyo constitution. Kikyo, or deficiency of Ki, is defined as delicate, easily fatigable, or hypersensitive constitution typically associated with poor gastrointestinal functions, anorexia and night sweats (34). In experiments using animal models, orally administered Hochu-ekki-to exhibits various immunopharmacological effects, especially anti-allergic properties. They include suppression of serum IgE level and eosinophil infiltration and improvement of dermatitis through controlling Th1/Th2 balance possibly by inducing interferon γ production from intraepithelial lymphocytes (35–42). In addition, Hochu-ekki-to helps to correct leukocytopenia of mice treated with anti-cancer agents and augments the resistance against bacterial infections (43,44). These results suggest that Hochu-ekki-to may be applicable to the treatment of AD patients who have Kikyo constitution. Although accumulating reports have shown clinical efficacy of Hochu-ekki-to for AD patients (13,15,17,20,21,25,27,29–33), no placebo-controlled study has previously been conducted.

In this double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial, we address a question of whether Hochu-ekki-to has beneficial effects for Kikyo patients with AD who have been treated with conventional modalities.

Methods

Hochu-ekki-to

Hochu-ekki-to fine granules of 7.5 g contain hot water extract (6.4 g) from 10 species of medicinal plants including Ginseng radix (4.0 g), Atractylodis rhizoma (4.0 g), Astragali radix (4.0 g), Angelicae radix (3.0 g), Zizyphi fructus (2.0 g), Bupleuri radix (2.0 g), Glycyrrhizae radix (1.5 g), Zingiberis rhizoma (0.5 g), Cimicifugae rhizoma (1.0 g) and Aurantii nobilis Pericarpium (2.0 g).

Assessment of Kikyo Condition

Kikyo condition was evaluated by a questionnaire scoring system. As shown in Table 1, the scoring questionnaire consisted of one ‘must have’ major sign (10 points) and 10 minor signs (2 points each). The patients who had the major sign and earned 18 points or more using the questionnaire were determined as Kikyo constitution.

Table 1.

Questionnaire scoring system for Kikyo constitution

| Items | Signs and conditions | Scores |

|---|---|---|

| Major sign (must-have) | Easy fatigability or lack of perseverance | 10 |

| Susceptibility to infections | Susceptible to cold | 2 |

| Delayed recovery from cold | 2 | |

| Vulnerable to other infectious diseases (herpes virus etc) | 2 | |

| Susceptible to suppuration | 2 | |

| Anorexia | Recent very little eating | 2 |

| Appetite loss | 2 | |

| Easily-becoming full stomach | 2 | |

| Nahrungsverweigerung | 2 | |

| Digestive symptom | Diarrhea (laxity) | 2 |

| Others | Easy drowsiness especially after meals | 2 |

| Total scores | 30 |

Patients who have the major sign and earn 18 points or more in this questionnaire scoring system are determined as Kikyo constitution.

Study Population

Patients (20–40 years of age) with Kikyo constitution who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of Japanese Dermatological Association for AD were eligible for this study. All the 91 AD patients enrolled had been treated with topical steroids (mild, strong, or very strong rank) and/or topical tacrolimus for more than 4 weeks prior to the study, and were expected to continue the same therapeutic regimen after the initiation of the study. Patients were not eligible for the study if they had been treated with only weak topical steroids (without stronger topical steroids or tacrolimus), strongest topical steroids, systemic steroids, oral suplatast tosilate, allergen desensitization therapy, or any other herbal medicines for <4 weeks prior to the study. The study was approved by the responsible ethics committee and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Good Clinical Practice. An informed witnessed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Study Protocols

The study was performed in a multicenter, double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled parallel-group design. The patient number was randomly assigned a treatment code of either Hochu-ekki-to or placebo using a block size of 10 (5 per each group) by an independent controller of the investigators. This code was concealed from the investigators. During trial period, patients were randomized to receive twice daily either Hochu-ekki-to fine granules (Kracie Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) or its inactive placebo which were indistinguishable by its appearance, odor and savor. The daily doses were 7.5 g. All patients continued their ordinary treatments such as topical steroids (other than strongest class), topical tacrolimus, emollients or oral anti-histamines. The skin severity score, amounts of topical agents, adverse effects and laboratory examination including serum IgE, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) or eosinophil counts were monitored at pre (0-week)-, mid (12-week)- and post (24-week)-treatment. The prominent efficacy (skin severity score = 0 at the end of the study) rate and the aggravated rate (more than 50% increase of amounts of topical agents from the beginning of the study) were also evaluated.

Assessment of Skin Severity Scores

The skin severity scores of AD patients were assessed using the scoring system by the Atopic Dermatitis Severity Evaluation Committee of Japanese Dermatological Association (issued 2001). The skin severity scores were composed of eruption intensity score and affected skin area score. The body surface was divided into five sites, namely head and neck, anterior trunk, posterior trunk, upper extremities and lower extremities. The eruption intensity and affected skin area were evaluated and scored. Eruption intensity scores were evaluated using three eruption items: (i) erythema/acute papules, (ii) oozing/crusts and excoriation and (iii) lichenification/chronic papules and nodules) in the severest area scored from 0 to 3 points (0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, or 3 = severe) for each item in each body site. The affected skin area was also evaluated and scored in each body site as 0, 1, 2, 3 points when affected skin area was absent, less than one-third, one-third to two-third, more than two-third of each body site, respectively. Thus, the skin severity score ranges from 0 to 60 points.

Assessment of the Dosage of Topical Steroids and Topical Tacrolimus

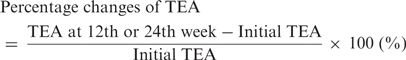

At each patient visit, the actual amounts used of topical steroids and/or topical tacrolimus were measured by weighing the returned ointment tubes from examinees. The amount of topical agents (steroids and tacrolimus) per day was expressed as total equivalent amount (TEA) (gram arbitrary unit; gau) by multiplying potency equivalent factors as follows; weak rank steroids = × 1, mild rank steroids = × 2, strong rank steroids = × 4, very strong rank steroids = × 8, tacrolimus = × 4. Percent change of TEA to that of the beginning of the study was calculated for each patient at 12th and 24th week of treatment using the following formula;

|

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software (version 8.02; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) under the Windows XP operating system. Data were expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SE). A P-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Treatment efficacy was analyzed by comparing the difference between Hochu-ekki-to and placebo control groups using unpaired Student's t-test or Fisher's exact test.

Results

Patient Enrollment and/or Exclusion

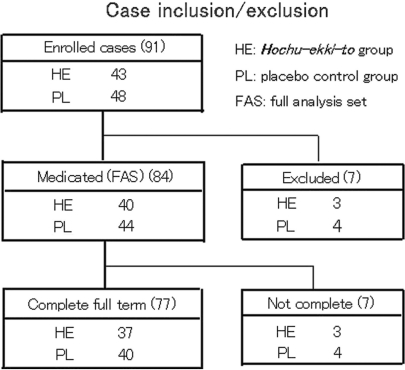

In total, 91 patients were enrolled and randomized in this trial from February to November 2002. Seven out of the initial 91 enrolled patients were excluded from subsequent analysis for the following reasons; agreement acquisition violation (n = 4), eligibility violations (n = 2) and failure to take trial medicine at all (n = 1). Thus the number of patients who actually received medication (hereafter termed ‘full analysis set: FAS’ group) and who were analyzed was 84 (Hochu-ekki-to: n = 40, placebo: n = 44). Seventy-seven out of the 84 patients completed the 24-week treatment course (Fig. 1), including a patient in whom TAE of topical agents could not be assessed because of the insufficient descriptions on the item. There were no statistically significant differences between Hochu-ekki-to- and control groups in terms of age, sex, physique, duration of AD morbidity, incidence of past- or present history of other allergic or non-allergic diseases, Kikyo score, skin severity score, initial TAE of topical agents per day (Supplementary data 1). Two out of the 7 dropped-out cases during the trial (One each in placebo and Hochu-ekki-to group) were excluded because of a significant aggravation of skin eruption and occurrence of headache, respectively. Others were found unfit for further analyses (dismissal of medication etc).

Figure 1.

The chart of case enrollment and exclusion. Among the 91 enrolled AD patients, 84 patients were medicated and 77 out of the 84 patients completed full term (for 24 weeks) of trial.

Clinical Efficacy of Hochu-ekki-to

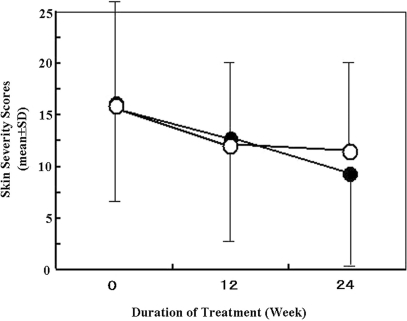

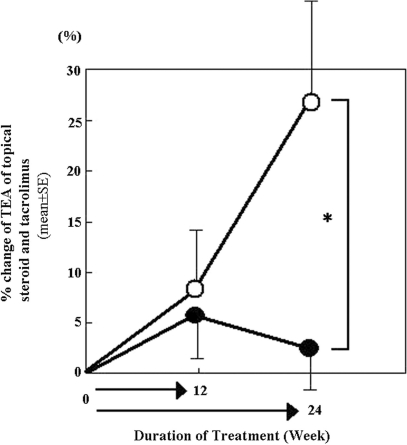

The overall skin severity score gradually decreased as examination went on and was slightly lower in Hochu-ekki-to group (closed circle) than in placebo group (open circle) at 24th week (Fig. 2). The TEA of topical agents gradually increased in the placebo group during the trial period, whereas such increase of TEA was minimal to unchanged in the Hochu-ekki-to group. The percent change of TEA at 24th week was significantly (P < 0.05) lower in the Hochu-ekki-to group (closed circle) than in the placebo control group (open circle) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

The time course change of skin severity score during examination. Skin severity scores were assessed at pre-, mid (12-week)- and post (24-week)-treatment in Hochu-ekki-to- (closed circle) and placebo group (open circle). Data were expressed as the mean ± SD. There is no significant difference between Hochu-ekki-to- and placebo groups.

Figure 3.

The time course change of equivalent dosage of topical agent during examination. The percent changes of TEA of topical agents were assessed at pre-, mid (12-week)- and post (24-week)-treatment in Hochu-ekki-to- (closed circle) and placebo group (open circle). Data were expressed as the mean ± SE. The TEA of topical agents gradually increased in the placebo group as trial went, while such increase was minimal to unchanged in the Hochu-ekki-to group. *P < 0.05.

Since Hochu-ekki-to was thought to be a slow-acting herbal medicine and the present trial was relatively long-term, we wondered if a striking beneficial effect was observed in a certain population of patients by long-term use of Hochu-ekki-to. Therefore, we analyzed a prominent efficacy rate, the rate of patients whose skin severity score became 0 at the end of the study. The prominent efficacy rate was indeed moderately higher in the Hochu-ekki-to group (19%; 7 of 37) than in the placebo group (5%; 2 of 40), although there was not a significant difference (P = 0.06). Furthermore, the aggravated rate, defined as ratio of patients whose TEA had increased more than 50% at 24 weeks from the beginning of the study, was significantly lower in the Hochu-ekki-to group (3%; 1 of 37) than in the placebo group (18%; 7 of 39) (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the serum IgE, LDH, or eosinophil counts in peripheral blood in both groups (data not shown).

Adverse Events and Abnormal Laboratory Findings

The adverse events, including those of unclear causality with treatment using tested agents, were observed in 13 of 40 patients (32.5%, total 33 events) in the Hochu-ekki-to group and in 12 of 44 patients (27.3%, total 20 events) in the placebo group. All the adverse events were moderate symptoms such as nausea and diarrhea etc or slight increase or decrease of laboratory data (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse effects

| The number of cases with adverse effects | Adverse effects (the number of cases if not one), including those of unclear causality with treatment using tested agents | |

|---|---|---|

| Hochu-ekki-to group | 13/40 (32.5%) | Symptoms: nausea (2), diarrhea (2), stomach discomfort (2), enlarged feeling of abdomen, epigastralgia, anorexia, loose stools, right hypochondrium pain, malaise, dizziness, headache, light-headed feeling, rhinitis, acne pustulosa, feverish thirstiness, dental caries. |

| Laboratory data: eosinophilia (3), GPT elevation, IgE elevation, BUN decline, serum K elevation. | ||

| Placebo-control group | 12/44 (27.3%) | Symptoms: ovarian disorder (2), diarrhea, epigastric discomfort, anorexia, malaise, hives, insomnia, feverish limbs. |

| Laboratory data: eosinophilia (4), LDH elevation (2), GOT elevation (2), γ-GTP elevation, serum total protein decline, hemoglobin decline. |

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that 24-week oral administration of Hochu-ekki-to has a substantial benefit over placebo in the treatment of Kikyo patients with AD. The administration of Hochu-ekki-to significantly reduces dosage of topical steroids and/or tacrolimus, compared with placebo, although there was no significant difference in the mean skin severity scores between both groups. These results indicate that the patients in the placebo group need significantly more topical steroids and/or tacrolimus in order to control their skin conditions. In keeping with this notion, the post-treatment prominent efficacy rate tends to be higher in the Hochu-ekki-to group than in the placebo group. In contrast, the aggravated rate was significantly lower in the Hochu-ekki-to group than in the placebo group. It was surprising that 19% of patients in the Hochu-ekki-to group were devoid of skin eruption after the 24-week treatment. Considering the long-term history of the majority of the 7 ‘eruption-free’ patients (10–34 years, mean ± SD: 21.9 ± 8.0), this marked improvement would indicate the beneficial effects of Hochu-ekki-to, as ‘spontaneous’ healing was not likely to take place in those severe AD patients during the course of trial.

Hochu-ekki-to, however, did not seem to be effective for all the AD patients in this trial. Individual difference of intestinal flora has been proposed to be one of the major reasons for such disparity of the efficiency of Kampo therapy. It is because active components of orally administered herbal drugs are known to be assimilated through the intestinal mucosa under the influence of the intestinal flora (45). Although we generally advise patients to choose traditional Japanese diet in usual Kampo treatment as intestinal flora can be affected by daily diet, we have avoided intensive intervention during this trial period, assuming that such intervention could be a considerable stress for certain patients and could significantly influence their clinical course of skin symptoms by increasing itch sensation etc. The clinical action of Hochu-ekki-to appears to be rather mild and limited; however, the present study clearly demonstrates an add-on beneficial effect of this herbal drug over the conventional treatments. Kampo herbal drugs are broadly classified into two categories, immediate acting- and slow acting ones. Since Hochu-ekki-to is considered to work in the latter manner, supporting the inactive Kikyo body to become warm and active. Thus, it needs to be administered for a long time to be shown effective. A long-term (for 24 weeks) administration was adopted in our protocol design because of the relatively slow acting profile of Hochu-ekki-to. The significant clinical benefits indeed appeared at 24th week rather than 12th week, as shown by the reduction of TEA of topical agents and of the reduced aggravated rates.

Kampo herbal drugs are usually prescribed according to patient's Sho (constitution/condition) such as Yin (negativity) and Yang (positivity) or Kyo (deficiency) and Jitsu (fullness) and to target components to treat such as Ki (energy, spirit and function), Ketsu (blood and organs) and Sui (fluid), all of which are considered to be basic components constituting human body. Hochu-ekki-to is recommended to be used for Kikyo condition, a state of functional deficiency. In our trial, only AD patients with Kikyo constitution were selected eligible by using the questionnaire scoring system. This selection may favorably contribute to carve in relief of the clinical significance of Hochu-ekki-to over placebo, thus it remains to be tested if the herbal drug has such beneficial effect on AD patients without Kikyo constitution.

Although considerable attention has been paid on traditional herbal medicines as a treatment option for AD (13–33), there are only a few reports examining their efficacy in a randomized, double blind manner, as reviewed by Armstrong and Ernst (46). Sheehan et al. (47–49) have reported the usefulness of the composite herbs of Zemaphyte® in a randomized, double blind cross-over trial, where it was shown that the Zemaphyte's composite herbs possess anti-inflammatory and anti-congestive function (48). However, a subsequent trial by Fung et al. (50) failed to confirm its superiority over placebo. Although efficacies of herbal medicines are now being recognized even outside the Asian countries (51), there has been no report of double-blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial of herbal drugs as treatment for AD other than Zemaphyte® before the present study.

In conclusion, our results indicate that Hochu-ekki-to is a useful adjunct to conventional treatments for Kikyo patients with AD. We contend that it can reduce the dosage of topical steroids and tacrolimus without aggravating the clinical course of AD.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at eCAM online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by Kracie Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). We are indebted to participating investigators in the Study; Yamano Dermatological Clinic: T. Yamano; Tanizaki Dermatological Clinic: Y. Tanizaki; Shimizu Dermatological Clinic: N. Shimizu; Iriki Dermatological Clinic: A. Iriki; Higashihie Dermatological Clinic: A. Nishie; Haradoi Hospital; H. Ikematsu, K. Hayashida; Department of Dermatology, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine: H. Teramae, H. Kutsuna, K. Yoshida; Osaka City General Hospital: S. Suzuki, K. Nakano; Osaka City Juso Hospital: S. Kuniyuki, Hoshigaoka Koseinenkin Hospital: H. Kato, C. Yasunaga; Izumi City Hospital: K. Yoshioka, T. Murakami. In addition, we thank Takuya Kawakita, Hide-itiro Ogasawara, Kazunori Yamamoto, Ai Iwabuti, Yuki Kubo and Katsutaka Sakai of Kracie Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

References

- 1.Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockholm) Suppl. 1980;92:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furue M, Furukawa F, Hide M, Takehara K. Guidelines for therapy for atopic dermatitis 2004. Jpn J Dermatol. 2004;114:135–42. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoare C, Li Wan Po A, Williams H. Systematic review of treatments for atopic eczema. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4:1–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams HC. Is the prevalence of atopic dermatitis increasing? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:385–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1992.tb00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams H, Robertson C, Stewart A, Aït-Khaled N, Anabwani G, Anderson R, et al. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:125–38. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi M, Ueda H. Increase of adult atopic dermatitis (AD) in recent Japan. Environ Dermatol. 2000;7:133–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saeki H, Tsunemi Y, Fujita H, Kagami S, Sasaki K, Ohmatsu H, et al. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis determined by clinical examination in Japanese adults. J Dermatol. 2006;33:817–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis C, Luger T, Abeck D, Allen R, Graham-Brown RA, De Prost Y, et al. ICCAD II faculty. International consensus conference on atopic dermatitis II (ICCAD II): clinical update and current treatment strategies. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(Suppl 63):3–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.148.s63.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazarous MC, Kerdel FA. Topical tacrolimus protopic. Drugs Today. 2002;38:7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reitamo S, Rissanen J, Remitz A, Granlund H, Erkko P, Elg P, et al. Tacrolimus ointment does not affect collagen synthesis: results of a single-center randomized trial. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:396–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soter NA, Fleischer AB, Jr, Webster GF, Monroe E, Lawrence I. Tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in adult patients: part II, safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(Suppl 1):S39–46. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.109817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charman CR, Morris AD, Williams HC. Topical corticosteroid phobia in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:931–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi K, Ishii M, Asai Y, Hamada T. Experiences of therapy for skin disease by Japanese herbal medicine. Kampo Med. 1981;5:9–11. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horiguchi Y, Horiguchi N, Okamoto Y, Okamoto H, Oguchi M, Ozaki M. Effect of Saiko-seikan-to on atopic dermatitis. Hifuka kiyo. 1983;78:145–50. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto I. Clinical dermatology 7, eczema and dermatitis II, atopic dermatitis. The Kampo. 1986;4:2–17. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ninomiya F. Kampo for adult atopic dermatitis. Gendai Toyo igaku. 1988;9:162–5. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi H, Ishii M, Tanii T, Kono T, Hamada T. Kampo therapies for atopic dermatitis: the effectiveness of Hochu-ekki-to. Nishinihon Hifu. 1989;51:1003–13. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morohashi M, Takahashi S. Kampo medicine for atopic dermatitis. Allerugi no Rinsho. 1989;9:711–4. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada H, Tsujii Y, Yamagami N, Aragane Y, Saeki M, Harada M, et al. Clinical effectiveness of Sairei-to for atopic dermatitis. Nishinihon Hifu. 1990;52:1202–7. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuji Y, Tsujimoto Y, Iikura Y, Kamiya A, Uchida Y, Kurashige T, et al. Study of clinical efficacy of Hochu-ekki-to for child patients with atopic dermatitis. Rinsho Kenkyu. 1993;70:4012–21. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamada T. Kampo therapy in dermatology. In: Dermatological Oriental Medicine Study Group (eds), editor. State of Herb Treatments in Dermatology. Vol. 5. Tokyo: Igakushoin; 1994;. pp. 3–21. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terasawa K, Kita T, Shimada Y, Shibahara N, Ito T. Four cases report of atopic dermatitis successfully treated with Tokaku-joki-to. Jpn J Oriental Med. 1995;46:45–54. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuda O, Terasawa K. Unkei-to related Kampo formulas for atopic dermatitis. Curr Ther. 1995;13:2041–4. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujinaga H, Terasawa K. A case with atopic dermatitis in whom Keigai-rengyo-to related formula was effective. Curr Ther. 1996;14:513–5. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishii M, Kobayashi H, Mizuno N, Takahashi K, Yamamoto I. Japanese herb treatments of adult atopic dermatitis by diet and Japanese herb remedy—evaluation of disappearance of disease phases. In: Dermatological Oriental Medicine Study Group (eds), editor. State of Herb Treatments in Dermatology. Vol. 9. Tokyo: Sogoigaku Co.;; 1997. pp. 63–77. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goto H, Kita T, Shintani T, Shimada Y, Terasawa K. On the indication of Shishi-zai. Jpn J Oriental Med. 1997;48:225–32. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Natsuaki M. Kampo therapy for eczema and dermatitis. Derma. 1998;11:27–32. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ninomiya F. Experience of Shishi-hakuhi-to in the treatment of dermatitis. Kampo kenkyu. 1999;326:38–42. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishii M. Combination therapy with diet and traditional Japanese medicine for intractable adult atopic dermatitis—Interpretation of dietary influence. In: Dermatological Oriental Medicine Study Group (eds), editor. State of Herb Treatments in Dermatology. Vol. 10. Tokyo: Kyowa Kikaku Tsushin; 1999. pp. 35–42. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi H, Mizuno N, Teramae H, Kutsuna H, Ueoku S, Onoyama J, et al. Diet and Japanese herbal medicine for recalcitrant atopic dermatitis: efficacy and safety. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2004;30:197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi H, Mizuno N, Teramae H, Kutsuna H, Ueoku S, Onoyama J, et al. The effects of Hochu-ekki-to in patients with atopic dermatitis resistant to conventional treatment. Int J Tissue React. 2004;26:113–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi H, Takahashi K, Mizuno N, Kutsuna H, Ishii M. An alternative approach to atopic dermatitis: part I—case-series presentation. Evid based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:49–62. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi H, Takahashi K, Mizuno N, Kutsuna H, Ishii M. An alternative approach to atopic dermatitis: part II—Summary of cases and discussion. Evid based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:145–55. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terasawa K. Evidence-based reconstruction of Kampo medicine: part II—the concept of Sho. Evid based Complement Alternat Med. 2004;1:119–23. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaneko M, Kishihara K, Kawakita T, Nakamura T, Takimoto H, Nomoto K. Suppression of IgE production in mice treated with a traditional Chinese medicine, Bu-zhong-yi-qi-tang (Japanese name: Hochu-ekki-to) Immunopharmacology. 1997;36:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(96)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaoka Y, Kawakita T, Kishihara K, Nomoto K. Effect of a traditional Chinese medicine, Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang on the protection against an oral infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Immunopharmacology. 1998;39:215–23. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tahara E, Satoh T, Watanabe C, Nagai H, Shimada Y, Terasawa K, et al. Effect of Kampo medicines on IgE-mediated biphasic cutaneous reaction in mice. J Trad Med. 1998;15:100–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawakita T, Nomoto K. Immunopharmacological effects of Hochu-ekki-to and its clinical application. Prog Med. 1998;18:801–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaneko M, Kawakita T, Nomoto K. Inhibition of eosinophil infiltration into the mouse peritoneal cavity by a traditional Chinese medicine, Bu-zhong-yi-qi-tang (Japanese name: Hochu-ekki-to) Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1999;21:125–40. doi: 10.3109/08923979909016398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishimitsu R, Nishimura H, Kawauchi H, Kawakita T, Yoshikai Y. Dichotomous effect of a traditional Japanese medicine, bu-zhong-yi-qi-tang on allergic asthma in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:857–65. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi H, Mizuno N, Kutsuna H, Teramae H, Ueoku S, Onoyama J, et al. Hochu-ekki-to suppresses development of dermatitis and elevation of serum IgE level in NC/Nga mice. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2003;29:81–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao XK, Fuseda K, Shibata T, Tanaka H, Inagaki N, Nagai H. Kampo medicines for mite antigen-induced allergic dermatitis in NC/Nga Mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:191–9. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li XY, Takimoto H, Miura S, Yoshikai Y, Matsuzaki G, Nomoto K. Effect of a traditional Chinese medicine, Bu-zhong-yi-qi-tang (Japanese name: Hochu-ekki-to) on the protection against Listeria monocytogenes infection in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1992;14:383–402. doi: 10.3109/08923979209005400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaneko M, Kawakita T, Kumazawa Y, Takimoto H, Nomoto K, Yoshikawa T. Accelerated recovery from cyclophosphamide-induced leukopenia in mice administered a Japanese ethical herbal drug, Hochu-ekki-to. Immunopharmacology. 1999;44:223–31. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(99)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuo F, Zhou ZM, Yan MZ, Liu ML, Xiong YL, Zhang Q, et al. Metabolism of constituents in Huangqin-tang, a prescription in traditional Chinese medicine, by human intestinal flora. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:558–63. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Armstrong NC, Ernst E. The treatment of eczema with Chinese herbs: a systemic review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:262–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheehan MP, Rustin MH, Atherton DJ, Buckley C, Harris DJ, Brostoff J, et al. Efficacy of traditional Chinese herbal therapy in adult atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 1992;340:13–7. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92424-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheehan MP, Atherton DJ. A controlled trial of traditional Chinese medicine plants in widespread non-exudative atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1992;126:179–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb07817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheehan MP, Atherton DJ. One-year follow up of children treated with Chinese medicinal herbs for atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:488–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb03383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fung AY, Look PC, Chong LY, But PPH, Wong E. A controlled trial of traditional Chinese herbal medicine in Chinese patients with recalcitrant atopic dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:387–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Latchman Y, Whittle B, Rustin M, Atherton DJ, Brostoff J. The efficacy of traditional Chinese herbal therapy in atopic eczema. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1994;104:222–6. doi: 10.1159/000236669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.