Here we report that low concentrations of alcohol (1–3 mM) increased Cl− currents gated by a recombinant GABAA receptor, α4β2δ, by 40–50% in Xenopus laevis oocytes. We also found greater hippocampal expression of receptors containing α4 and δ subunits, using a rat model1 of premenstrual2 syndrome (PMS) in which 1–3 mM alcohol preferentially enhanced GABA-gated currents, and low doses of alcohol attenuated anxiety and behavioral reactivity. The alcohol sensitivity of δ-containing receptors may underlie the reinforcing effects of alcohol during PMS, when eye saccade responses to low doses of alcohol are increased2.

Alcohol is an addictive recreational drug that reduces anxiety at low doses and causes sedation at high doses3. These effects are similar to those of drugs that enhance the function of GABAA receptors, which gate the Cl− currents that mediate most inhibitory neurotransmission in the brain. Acutely high doses of alcohol potentiate GABA-gated currents3 at both native3 and recombinant GABAA receptors4, and chronically alter GABAA receptor expression5. Low doses of alcohol have not been shown to directly modulate recombinant GABAA receptors3, although there is indirect evidence for such effects at native receptors6,7.

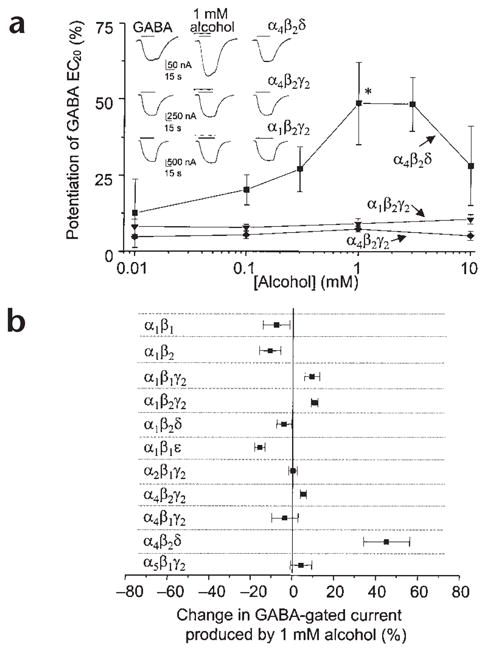

It has been suggested that discrepancies between the alcohol sensitivity of native and recombinant receptors may be due to their subunit composition1. We therefore investigated the effects of low concentrations of alcohol on different subtypes of recombinant GABAA receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Low (1 mM) concentrations of alcohol selectively increased GABA-gated currents at α4β2δ receptors by 45 ± 11% (P < 0.05, Fig. 1a). Substitution of γ2 for the δ subunit abolished this GABA-modulatory effect of alcohol (Fig. 1a), as did substitution of α1 for α4 when co-expressed with β2δ (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, none of the other subunit combinations that yielded functional receptors (Supplementary Methods online) were sensitive to low concentrations of alcohol (Fig. 1a and b). Thus, co-expression of α4 and δ subunits is necessary for potentiation by 1 mM alcohol.

Fig. 1.

Low concentrations of alcohol potentiate GABA responses at α4β2δ receptors. (a) The effects of alcohol on responses to GABA (EC20 = 0.03 μM α4β2δ, 1.7 μM α1β2γ2s, 5.6 μM α4β2γ2s) were measured by two-electrode voltage-clamp recording at −70 mV in oocytes expressing recombinant GABAA receptors. Inset, representative traces showing currents activated by GABA in the absence and presence of 1 mM alcohol. (b) Effects of 1 mM alcohol on GABA(EC20)-gated currents at various GABAA receptor subtypes (n = 8–20, *P < 0.05). Experiments were conducted according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

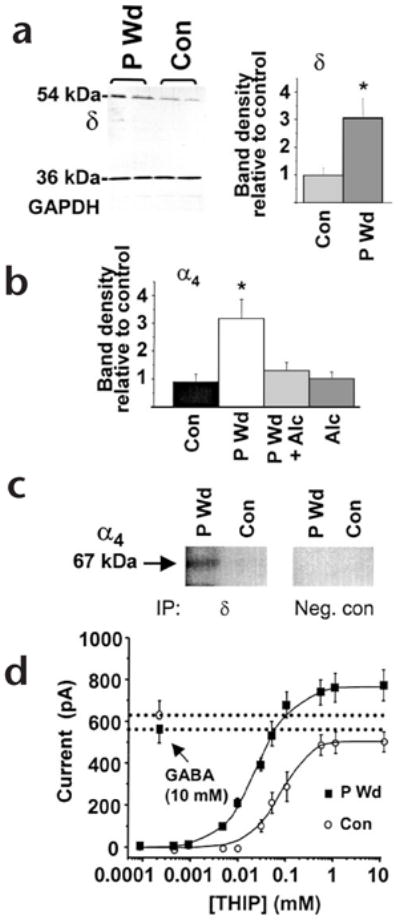

The α4βδ GABAA receptors are expressed at very low levels in most regions of the brain8. Predicting that physiological states that are associated with increased sensitivity to alcohol (such as PMS) may involve increased expression of α4βδ, we used a rodent model of PMS1 to test this hypothesis. With chronic in vivo administration and withdrawal of progesterone, we replicated the hormonal and behavioral facets of PMS2. Expression of δ and α4 subunit proteins in the hippocampus was three-fold higher after progesterone withdrawal (Fig. 2a and b, and Supplementary Fig. 1), as was δ-subunit mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 1). Co-assembly of these subunits was determined using co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2c) and verified by an increased efficacy of THIP, a GABA partial agonist, relative to GABA after progesterone withdrawal (Fig. 2d). This is characteristic of α4βδ receptor expression9. Co-assembly of β2 with α4δ has not been tested directly but is suggested by reports of high levels of β2 in areas rich in α4 and δ subunits.

Fig. 2.

Progesterone withdrawal increases α4βδ GABAA receptors. (a) Left, western blot showing increased expression of the δ subunit (54 kDa), but not a control protein (GAPDH, 36 kDa) after progesterone withdrawal (P Wd) compared to control (Con). Right, mean values (n = 20–25, performed in triplicate). (b) Increases in α4 protein following P Wd were prevented by in vivo administration of alcohol (0.5 g/kg × 3, intraperitoneally) during the final two hours of the withdrawal period (P Wd + Alc; n = 9–10). (c) Co-assembly of α4 and δ GABAA receptor subunits. After immunoprecipitation (IP) using protein A beads coupled to antibodies for the δ subunit (IP, δ) or a cytosolic protein (IP, Neg. con) membranes were probed with digoxygenin-labeled anti-α4 on a western blot (n = 4 hippocampi, in duplicate). A prominent 67-kDa band was detected after P Wd, but was barely detectable under control conditions. (d) The maximum current produced by THIP compared to that produced by 10 mM GABA was 1.41 after P Wd (THIP EC50 = 39 ± 2 μM), and 0.95 in control neurons (THIP EC50 = 81 ± 6 μM). This was determined using whole-cell patch clamp recording in neurons from CA1 hippocampus (n = 10–15, *P < 0.05).

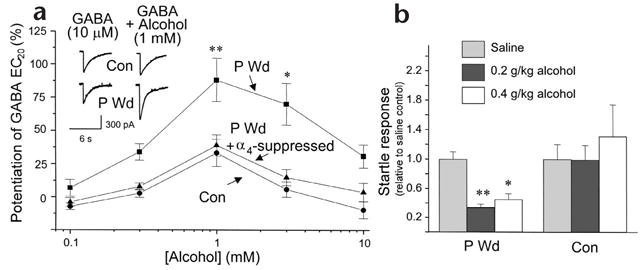

Concomitant with upregulation of α4βδ receptors in the progesterone-withdrawal model, 1 mM alcohol produced a 81 ± 21% potentiation of GABA-gated currents recorded from hippocampal neurons in vitro (Fig. 3a). Higher concentrations (10 mM and greater) of alcohol were not as effective in potentiating GABA-gated currents. After progesterone withdrawal, low doses of alcohol (0.2–0.4 g/kg) administered in vivo also decreased the acoustic startle response, a measure of behavioral excitability, suggesting a greater anxiolytic effect of alcohol at this time (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Low doses of alcohol potentiate GABA-gated currents in hippocampal pyramidal neurons and decrease behavioral excitability after progesterone withdrawal. (a) GABA (10 μM)-gated currents recorded in the presence or absence of alcohol (0.1–10 mM), measured by whole-cell patch clamp recording after progesterone withdrawal (P Wd) or under control conditions (con). Inset, representative traces. Suppression of α4 subunit expression (P Wd + α4 suppressed), as described in Fig. 2b, abolished the stimulatory effects of low concentrations of alcohol after P Wd (n = 20–25 cells/concentration, 8–10 rats/group). (b) Low doses of alcohol administered to P Wd (but not control) rats significantly lowered the acoustic startle response, expressed relative to the saline control (n = 5–11, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005).

To verify that native α4βδ receptors were sensitive to low doses of alcohol, we repeated the progesterone withdrawal experiments after suppressing α4 subunit expression. We have previously shown that, following progesterone withdrawal, injection of a GABA modulator prevents expression of the α4 subunit1. Thus, we used alcohol here to suppress expression of the α4 protein following progesterone withdrawal (P Wd + Alc; Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2). Under these conditions, the GABA-modulatory effects of 1 mM alcohol were prevented in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 3a; P Wd + α4 suppressed), again implicating α4βδ receptors as sensitive to low doses of alcohol. There is also corroborating evidence that the reinforcing and anti-convulsant properties of alcohol are reduced in transgenic mice lacking the δ subunit10.

It is thought that α4βδ receptors are expressed at extrasynaptic sites8 where they may dampen neuronal excitability, primarily by acting as a resistive shunt11. Enhanced function of these receptors by low concentrations of alcohol in women with PMS would further decrease neuronal excitability, leading to behavioral stress-reduction. Blood alcohol levels of 1–3 mM may result from consumption of a half glass of wine12 or less13. The reported increase in alcohol consumption and propensity for alcoholism in women with PMS14 may thus be accounted for by these enhanced reinforcing properties of alcohol. More broadly, it is conceivable that alterations in GABAA receptors, perhaps including α4β2δ, are involved in the genetic predisposition for alcoholism in which there is an increased sensitivity to low doses of alcohol15.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank M. Akabas, D. Dow-Edwards, S. Melnick, R. Markowitz, A. Smirnov and Y. Ruderman for technical assistance. Supported by National Institutes of Health grants DA09618 and AA12958 (S.S.S.), NS35047 (K.W.) and Wallenberg and Swedish Brain Foundation grants (I.S.P.).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Neuroscience website.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Smith SS, et al. Nature. 1998;392:926–930. doi: 10.1038/31948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundstrom I, et al. Neuroendocrinology. 1998;67:126–138. doi: 10.1159/000054307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueno S, et al. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:76S–81S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mihic SJ, et al. Nature. 1997;389:385–389. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahmoudi M, Kang MH, Tillakaratne N, Tobin AJ, Olsen RW. J Neurochem. 1997;68:2485–2492. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68062485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koob GF, et al. Alcohol. 1988;5:437–443. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(88)90079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan FJ, Berton F, Madamba SG, Francesconi W, Siggins GR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5049–5054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Somogyi P. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1693–1703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01693.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adkins CE, et al. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38934–38939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mihalek RM, et al. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1708–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brickley SG, Revilla V, Cull-Candy SG, Wisden W, Farrant M. Nature. 2001;409:88–92. doi: 10.1038/35051086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalant H, LeBlanc AE, Wilson A, Homatidis S. Can Med Assoc J. 1975;112:953–958. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holford NH. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1987;13:273–292. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198713050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLeod DR, Foster GV, Hoehn-Saric R, Svikis DS, Hipsley PA. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:664–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen HL, Poresz B, Begleiter H. Electroencepalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;86:368–376. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(93)90132-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.