Abstract

Tumor-induced T cell tolerance is a major mechanism that facilitates tumor progression and limits the efficacy of immune therapeutic interventions. Regulatory T cells (Treg) play a central role in the induction of tolerance to tumor antigens yet the precise mechanisms regulating its induction in vivo remain to be elucidated. Using the A20 B cell lymphoma model, here we identify myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) as the tolerogenic APCs capable of antigen uptake and presentation to tumor-specific Tregs. MDSC-mediated Treg induction requires arginase but is TGFβ independent. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of MDSC function respectively with NOHA or sildenafil abrogates Treg proliferation and tumor-induced tolerance in antigen specific T cells. These findings establish a role for MDSCs in antigen-specific tolerance induction through preferential antigen uptake mediating the recruitment and expansion of Tregs. Furthermore, therapeutic interventions such as in vivo phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE-5)-inhibition which effectively abrogate the immunosuppressive role of MDSCs and reduce Treg numbers, may play a critical role in delaying and/or reversing tolerance induction.

Keywords: myeloid derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells, tumor-induced tolerance, lymphoma, sildenafil

Introduction

The clonotypic idiotype of malignant B cells was the first tumor-specific antigen identified as capable of eliciting a T cell mediated immune response(1), (2). Despite the existence of this tumor-antigen and the well-documented expression of MHC class I and II molecules (3) as well as co-stimulatory molecules by a majority of human B cell malignancies, no spontaneous clinically significant immune response in these diseases has been documented (4). A number of studies have demonstrated that malignant B cells can process and present antigen to T cells in vitro, including the presentation of epitopes derived from their own unique immunoglobulin idiotype to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells(5-7). However, despite of their intrinsic antigen-presenting capabilities, B-cell tumors fail to be eliminated and tumor specific T cells are tolerized rather than activated in vivo (8). An understanding of why a T cell-mediated immune response is not elicited but suppressed in vivo is essential for the development of new therapeutic strategies aimed at optimizing the clinical efficacy of immunotherapy in these diseases.

In attempting to address these issues, we previously showed that a murine B-cell lymphoma (A20) transfected to express the model antigen influenza hemagglutinin (HA) activates HA-specific CD4+ T cells from T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice in vitro. However, with the adoptive transfer of HA-specific T cells into A20-HA bearing mice, the transgenic T cells are antigen experienced but anergized (8, 9). A more accurate analysis of the phenotype of these anergic CD4+ T cells revealed two subpopulations. The first population is CD25-/FOXP3neg and does not proliferate whereas the second CD25+/FOXP3+ population proliferates and inhibits the effector function of peptide stimulated naïve T cells (10, 11).

More recently we showed that in vivo disruption of host cross-presentation removes the tolerogenic mechanisms induced by the tumor and unmasks the intrinsic ability of malignant B cells to directly present tumor antigens (12, 13). Despite these findings, the true nature of the tolerogenic APC remains elusive.

Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) have recently been recognized as critical mediators of tumor progression in numerous solid tumors through their inhibition of tumor-specific immune responses (14). This monocyte/macrophage population is characterized by the expression of CD11b (15), F4/80 (16), IL4Rα (17), variable expression of Gr1 and low expression of CD11c, MHC class I and MHC class II (18). Whereas the number of MDSCs may not increase in certain models (19), their suppressive function clearly parallels increases in tumor burden (20). These cells blunt antitumor cytotoxic T cell (CTL) responses through the expression of arginase (Arg) and/or nitric oxide synthase (NOS)(21), or the secretion of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)(19). The activation of all these suppressive pathways seems to be regulated by IL4Rα since genetic ablation or pharmacological down-regulation of this receptor on MDSCs restores tumor-specific T cell responsiveness and immune-surveillance (17, 22).

Recently, the administration of Progenipoietin-1 (a synthetic G-CSF/Flt-3 ligand molecule) to donors, in an allogeneic bone marrow transplantation model, generated MDSCs that upon transfer suppressed the initiation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in recipients by inducing a population of MHC class-II-restricted, IL-10 producing Tregs (23). Similarly in a colon carcinoma murine model MDSCs either generated or expanded the pool of CD4+CD25+ FOXP3+ Treg cells (24).

Here we demonstrate a role for MDSCs during lymphoma progression. Specifically, with an increasing tumor burden MDSCs up-regulate IL4Rα expression, increase their suppressive activities, uptake and process tumor associated antigens (TAA), and importantly, by expanding naturally occurring tumor-specific Tregs, induce T cell tolerance.

Materials and methods

Mice

BALB/c (Thy1.2+/+CD45.2+/+) mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). TCR transgenic mice (6.5 Tg mice) on a BALB/c background expressing an αβ TCR specific for amino acids 110-120 from hemagglutinin (HA) were a gift from H. von Boehmer (Harvard Medical School, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA). The 6.5 Tg mice on Thy1.1+/+ or Thy1.1+/1.2+ background were used in the experiments as specified. Clone 4 mice transgenic for the H-2Kd–restricted TCR recognizing the influenza virus, HA peptide (HAp512–520) were a kind gift of LA Sherman (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). CD45.1+/+ BALB/c mice were a gift of H. Levitsky (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). Experiments using mice were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

The following antibodies were used for flow cytometry analysis: anti-mouse CD45.2 (peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCP]), anti-mouse CD11b (phycoerythrin [PE] or Allophycocyanin [APC]), Anti-mouse B220 (PE), anti-mouse CD124 (PE), anti-mouse CD80 (PE), anti-mouse CD86 (PE) anti-mouse Gr-1 (PE), anti-mouse IAd (PE), anti-mouse H2d (PE), anti-mouse CD11c (APC), anti-mouse F4/80 (APC), anti-mouse Thy1.2 (APC, or Fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]), anti-mouse Thy1.1 (PerCP or phycoerythrin PE), anti-mouse CD25 (PE), anti-mouse CD4 (APC or PerCP), anti-mouse FOXP3 (FITC, APC or PE [e-Biosciences, San Diego, CA]), anti-mouse IgG2a (streptavidin). Chloromethylfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester labeling of cells (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was previously described (22). All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (Mountain View, CA) unless otherwise specified. All fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was of surface expression except for FOXP3, for which cells were permeabilized. A total of 50000 gated events were collected on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) unless otherwise specified, and analyzed using FCS3 express software (De Novo software Thornhill, Ontario Canada).

Tumor cells and adoptive T cell transfer

A20-HA and A20WT cells were previously described (8). A20-HAGFP (a kind gift of H Levitsky, Johns Hopkins University) was generated by stable transfection of the A20-HA tumor with the enhanced green fluorescent protein and selected following in vivo passages and maintained in RPMI 10% FCS supplemented with G418 (400 μg/ml) and hygromycin (400 μg/ml). A20-HAGFP tumor progression is similar to the parental cell lines A20-HA and A20WT (data not shown). Tumor cells (1 × 106) were injected via tail vein. For adoptive transfer using whole CD4+ T cells, single-cell suspensions obtained from lymph nodes and spleens of 6.5 Tg donors were enriched for CD4+ cells via negative selection using the CD4 isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The percentage of lymphocytes positive for CD4 and the clonotypic TCR (monoclonal antibody [mAb] 6.5) was determined by flow cytometry. A total of 2.5 × 106 CD4+ 6.5 TCR+ T cells were injected intravenously into each BALB/c recipient. Vaccination was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 107 pfu of HA-encoding recombinant Vaccinia virus 25 days after tumor challenge.

Cells purification

Splenic CD11b+ cells were purified as previously described (22). CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25- T cell were magnetically enriched using the CD4/CD25 isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech) from the spleen and lymph nodes of 6.5 Tg mice. For experiments requiring the purification of CFSElow clonotypic cells, T cell were first magnetically enriched for CD4, labeled with Thy1.1-PE and sorted using a cell sorter (FACSVantage SE; BD Biosciences). To maximize MDSC and DC purity in some experiments, cells were sorted using a FACsARIA (BD Biosciences) after magnetic pre-enrichment.

Co-culture experiments

Sorted MDSC or DCs (105) were cultured for 5 days with 105 purified clonotypic Thy1.1+ T cells and with 106 Thy1.1-/- BALB/c splenocytes in 96 flat bottom well plates. Proliferation or phenotype was evaluated by flow cytometry.

Drugs and inhibitors

Sildenafil (Pfizer) was dissolved in the drinking water (20 mg/kg/24 h), NOHA and l-NMMA (Calbiochem) were used at 500 μM in vitro, anti TGF-β neutralizing antibody clone 2G7 (a kind gift of C. Drake Johns Hopkins University) at 50μg/ml.

Enzymatic Assays

The arginase assay was performed as previously described (25) on purified CD11b+cells. NOS activity was measured as nitrate/nitrite production on purified CD11b+ cultured for 24h in DMEM, 10% FCS supplemented with 50 mM of L-arginine, using the nitrate nitrite colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemical Ann Arbor MI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Results were normalized to 106 cells. Data are from triplicate wells. TGF-β was determined by ELISA (R&D systems Minneapolis MN) on the supernatant of purified CD11b+ cells cultured for 24h in AIM-V (Invitrogen). The supernatants were activated through acidification/neutralization before being tested. No TGF-β was detected without activation.

Results

Preferential antigen uptake by MDSCs

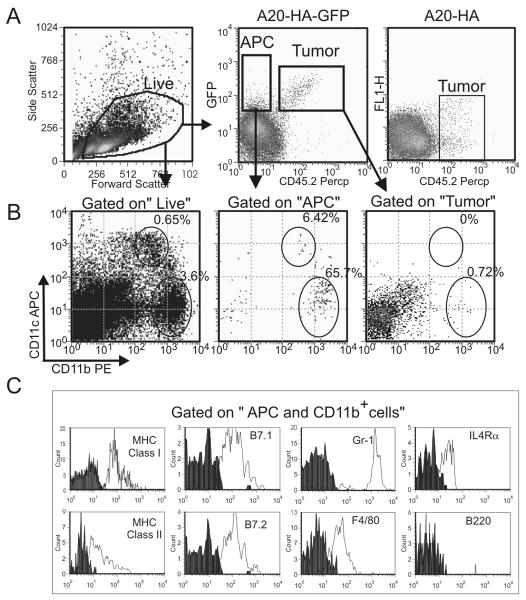

We previously showed that tumor-induced tolerance requires cross-presentation from BM derived APCs (12). While the precise cell population responsible remains unclear, the requirements for cross-presentation by APCs are well defined and include: 1) antigen uptake; 2) processing; and 3) presentation through their MHC molecules. To evaluate antigen uptake by APCs in our model, we used the CD45.2+ A20-HA-GFP tumor, a B-cell lymphoma transfected to co-express the HA antigen a model of tumor associated antigens (TAA) and the GFP molecule. These modifications do not interfere with normal tumor growth (data not shown) and permit identification of the malignant cells in vivo through expression of GFP as well as the congenic marker, CD45.2, in the CD45.1 BALB/c background.

A20-HA-GFP (CD45.2+/+) was injected i.v. into CD45.1+/+ BALB/c mice. Analysis on day 28 revealed the presence of a CD45.2-/GFP+ population consistent with antigen capture (Fig 1A). Further analysis of this population showed that a majority of the cells (65.7%) are characterized by a CD11bhigh/CD11clow phenotype (Fig.1B) whereas only few (6.4%) possessed a CD11blow/CD11chigh phenotype characteristic of myeloid DCs. As expected, few cells within the tumor gate possessed markers for either MDSCs or myeloid DCs. Further analysis of the CD45.2- GFP+ CD11bhigh population demonstrates low expression of MHC class I and class II molecules and of the co-stimulatory molecules B7.1 and B7.2, and high expression of granulocyte marker Gr-1. Moreover, this population expresses IL4Rα and F4/80 but is negative for B220 (Fig.1C). Taken together, this phenotype is consistent with that of MDSCs described in many murine solid tumors (reviewed in (14)) and excludes the possibility of contamination with residual tumor (B220+). The fact that the majority of host GFP+ cells share a phenotype consistent with MDSCs suggests that they may play an important role in antigen uptake and tolerance induction in this model.

Figure 1. Phenotypic analysis of APCs in lymphoma.

Splenocytes from CD45.1+/+ BALB/c mice challenged 28 days before with 106 CD45.2+ A20-HA/GFP cells or with CD45.2+ A20-HA as control, were stained with anti-CD45.2-PerCP, anti-CD11b-PE and anti-CD11c-APC antibodies and analyzed by FACS. A) Gating strategies: a first gate (Live) was drawn on the Forward vs side scatter plot to exclude aggregate and cellular debris, while a second gate (APCs: Antigen Presenting Cells) was designed on the GFP+ CD45.2- population. B) CD11b and CD11c population were determined by gating in Live (B, left dot plot) or in Llive and APC (B right dot plot). C) Alternatively splenocytes were labeled with anti-CD45.2-PerCP, anti-CD11b-APC antibodies and with PE conjugated antibodies against the indicated marker. The histograms are gated on the hierarchical gate CD11b+ and APCs and Live. Data represent 3 pooled spleens representative of other 2 experiments. 105 events were acquired for analysis.

Properties of CD11b+ MDSCs isolated from lymphoma bearing mice

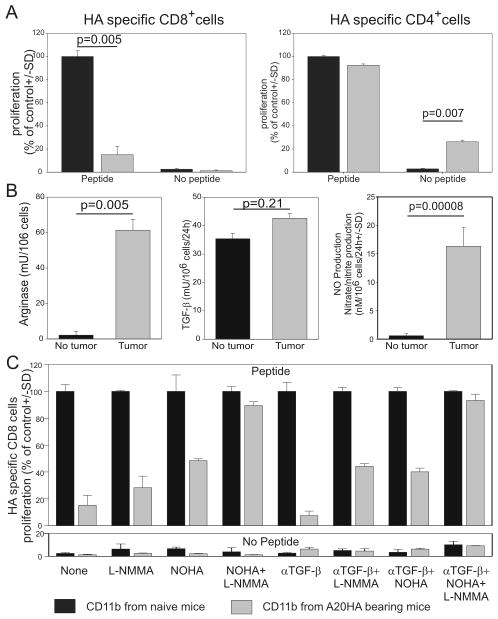

Although the cells identified in Fig.1 are phenotypically similar to the MDSCs described in solid tumors, further functional analyses are required to determine if these CD11b+cells are indeed MDSCs. In solid tumors, MDSCs strongly suppress antigen driven CD8 T cell proliferation yet have minimal impact on CD4 expansion.

It is well established that impairment of T cell effector function is mediated by mechanisms that require Arg, NOS or both enzymes. TGF-β production by MDSCs has also been shown to suppress T cell function (14). To evaluate if these functional properties also existed in the B-cell lymphoma model, we isolated CD11b+ cells from mice injected with A20-HA (gray bars) or PBS (naïve mice, black bars) 28 days earlier. Purified splenic CD11b+ cells were admixed with naïve BALB/c splenocytes and either HA-specific (clone 4) CD8+ (Fig.2A left panel) or HA-specific (6.5) CD4+ T cells (Fig.2A right panel). As expected, while the addition of CD11b+ cells from naïve mice did not alter antigen specific T cell proliferation, tumor-derived CD11b+cells inhibited the proliferation of HA-specific CD8+ cells stimulated with the relevant peptide (Fig.2A left panel). In contrast, HA-specific CD4+ T cell function was not impaired by tumor-derived MDSCs (right panel). Interestingly, in the absence of exogenous peptide but in the presence of CD11b+ cells isolated from A20-HA bearing mice, proliferation of CD4+ T cells could suggest endogenous uptake, processing and presentation by CD11b+ cells of tumor-derived antigens.

Figure 2. Molecular properties of CD11b+ cells isolated from lymphoma-bearing mice.

Mice were injected intravenously with 106 A20-HA cells or with PBS on day 0. On day 28 splenic CD11b+ cells were magnetically purified. A) An aliquot of CD11b+ cells (105 cells) was admixed with HA-specific, thy1.1+, CFSE labeled, magnetically purified CD4+ or CD8+ cells (105) in the presence of Thy1.2 Balb/c splenocytes as feeder (106) with or without relevant peptide. After 5 days, cell proliferation was determined as CFSE dilution by FACS analysis by gating on the clonotypic population. Data are normalized on the controls (proliferation of T cells cultured with CD11b+ cells isolated from naïve mice). B) Aliquots of CD11b+ were frozen and later tested for arginase or plated to determine TGF-β secretion or NO production as described in the materials and methods. C) The proliferation was repeated as described in (A) in the presence of NOHA (an arginase inhibitor), L-NMMA (a NOS2 inhibitor), anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibody, or with different combinations of these molecules. Data derived from one experiment representative of two.

As previously demonstrated in solid tumors (14), CD11b+ cells from lymphoma bearing mice also demonstrated pronounced arginase activity and nitric oxide (NO) production, but failed to show increases in TGF-β secretion (Fig.2B). To further evaluate which mechanism(s) were responsible for CD8 inhibition, we repeated the suppression assay shown in Fig.2A with the addition of NOHA (an arginase inhibitor), L-NMMA (an NOS2 specific inhibitor), and anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibody (clone 2G7) alone or in combination (Fig.2C). While the addition of anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibody failed to revert MDSC suppression on CD8+ T cells, the addition of either NOHA or L-NMMA partially restored T cell proliferation. Moreover, as previously reported in solid tumors(25), combined inhibition of both NOHA and L-NMMA fully restored T cell proliferation.

Taken together these data indicate that MDSC isolated from A20-HA-bearing mice share many functional properties with MDSCs found in solid tumors. Interestingly, since HA-specific CD4+ T cells proliferation occurred even in the absence of exogenous cognate peptide, these findings suggest that tumor-derived MDSCs are capable of antigen cross-presentation and likely mediate tolerance induction.

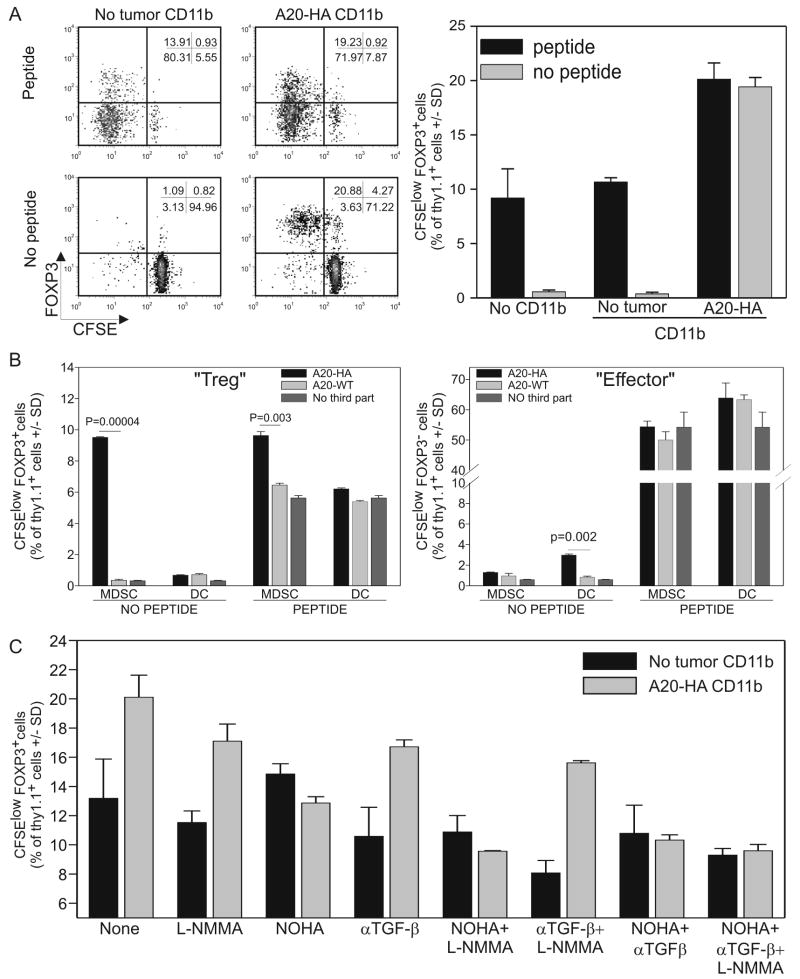

In vitro MDSCs preferentially induce proliferation of natural regulatory T cells

CD4+ T cells encompass various populations with different cellular and immunological functions (e.g. naïve, effector, regulatory, etc.). We, therefore, examined the role of MDSCs on these populations. Splenic CD11b+ MDSCs were obtained from BALB/c mice injected with either PBS or A20-HA 28 days earlier and purified. They were then co-cultured with HA-specific, Thy1.1+, CD4 purified, CFSE-labeled T cells and Thy1.2 BALB/c splenocytes used as feeder cells (Fig.3). In Fig.2 we showed that the addition of tumor-derived CD11b+ cells failed to reduce HA-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation. However, the phenotype of this proliferating clonotypic CD4+ population is significantly altered by tumor-derived CD11b+ cells (Fig.3A left panel). In fact, analysis of the CFSElow population revealed that the control co-cultures (no CD11b+ cells or CD11b+ cells from naïve mice) pulsed with the HA-peptide contained FOXP3+ cells representing 13.7 ± 0.8 % of the proliferating population (CFSElow). However, this percentage significantly increased with CD11b+ cells purified from A20-HA-bearing mice (23.6 ± 2 %) (Fig.3A right panel). Most interesting, however, is the selective expansion of FOXP3+ cells (77.3± 3.2% of CFSElow cells) seen in the absence of exogenous peptide when co-cultured with A20-HA-derived CD11b+ cells. This finding underscores the ability of tumor-derived MDSCs to selectively expand regulatory T cells and seems to suggest that exogenous peptide can influence the expansion of only FOXP3neg cells.

Figure 3. FOXP3+ CD4 T cells are increased after co-cultured with MDSCs.

A) CD11b+ cells were isolated from naïve or A20-HA tumor-bearing mice. 105 cells were then co-cultured with 105 HA-specific, magnetically purified, CFSE labeled, Thy1.1+CD4+ T cells and with 106 Thy1.1-/- BALB/c splenocytes in the presence or absence of the relevant peptide. After 5 days the cultures were labeled with anti-CD4 and anti-thy1.1, permeabilized and then labeled with anti-FOXP3. The dot plots are gated on the clonotypic T cell population. B) Results from 3 replicate wells are represented as the histogram mean +/-SD of FOXP3+CFSElow cells gated on the CD4+/Thy1.1+ population. C) Either high purity CD11bhigh,CD11clow MDSC or high purity CD11blow,CD11chigh MHC class IIhigh dendritic cells were sorted using a FacsAria cell sorter from spleens of mice challenged with A20WT or A20HA 28 days prior. MDSCs (105) or DCs (105) were cultured with CFSE-labeled, HA-specific, Thy1.1+/+ CD4+ T cells (105) and Thy1.2+/+ Balb/c splenocytes (106) as feeder cells. The cultures were analyzed after 3 days by flow cytometry as described in (A). The proliferation of clonotypic FOXP3+ T cells (left panel) or clonotypic FOXP3neg T cells (right panel) was analyzed using Cell Diva and FCS software. C) The same experiment described in (A) was conducted in the presence of the inhibitors described in Fig2. Data derived from triplicate wells of 1 experiment representative of a total of 3 experiments.

We, thus, evaluated the effect of different amounts of exogenous peptide in vitro on CD4 proliferation (Suppl fig 1). In the absence of MDSCs, both FOXP3+ and FOXP3neg T cell proliferation correlates with the amount of exogenous peptide added (Suppl. Fig.1 left panels). Interestingly, in the presence of A20HA-derived MDSCs, Treg proliferation is elevated and independent of the amount of exogenous peptide added (Suppl.Fig.1 upper right). In contrast, proliferation of the effector, FOXP3 neg T cells is similar to the control and unaltered by the presence of A20HA-derived MDSCs (suppl. fig.1 compare lower panels).

Since splenocytes are used as feeder cells in these experiments,, it is possible that different APC populations may be responsible for Treg or effector T cell proliferation. To evaluate this hypothesis, highly purified MDSCs, (CD11b+, CD11Clow, MHC class IIlow) or dendritic cells (CD11chigh, MHC class IIhigh and CD11blow/-) were sorted from spleens of mice challenged with A20HA or A20WT 4 weeks prior. Sorted cells were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+/- 6.5+/- HA specific CD4+ T cells in the presence of Thy1.2+ Balb/c splenocytes for 48 hours (Fig.3B). The relevant peptide was added where indicated. In the absence of exogenous peptide, A20HA-derived MDSCs significantly stimulated Treg proliferation while no effect was observed on FOXP3neg effector T cells (Fig 3B). In contrast, A20HA-derived DCs induced a small but significant proliferation of effector CD4+ T cells with no measurable effect on Treg proliferation (Fig 3B). The addition of exogenous peptide again minimized the observed differences. Taken together these data support the hypothesis that different APC populations selectively expand specific CD4+ subsets.

To evaluate if the same mechanisms involved in MDSC-mediated CD8+ T cell suppression are involved in the differential proliferation of regulatory FOXP3+ compared to effector T cells, we repeated the co-culture experiments described in Fig.2C utilizing clonotypic CD4 T cells. As shown in Fig.3C, L-NMMA and the anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibody showed only modest decreases in FOXP3+ T cell proliferation. In contrast, the addition of the arginase inhibitor, NOHA, completely reduced MDSC-induced Treg proliferation to levels comparable to those seen in the control group (CD11b cells obtained from non tumor-bearing mice).

Taken together, these data strongly suggest that MDSCs can alter the homeostatic equilibrium between regulatory and effector T cells. The preferential expansion of Tregs in the culture seems to be determined by both the presence of tumor-derived MDSC and their arginase activity.

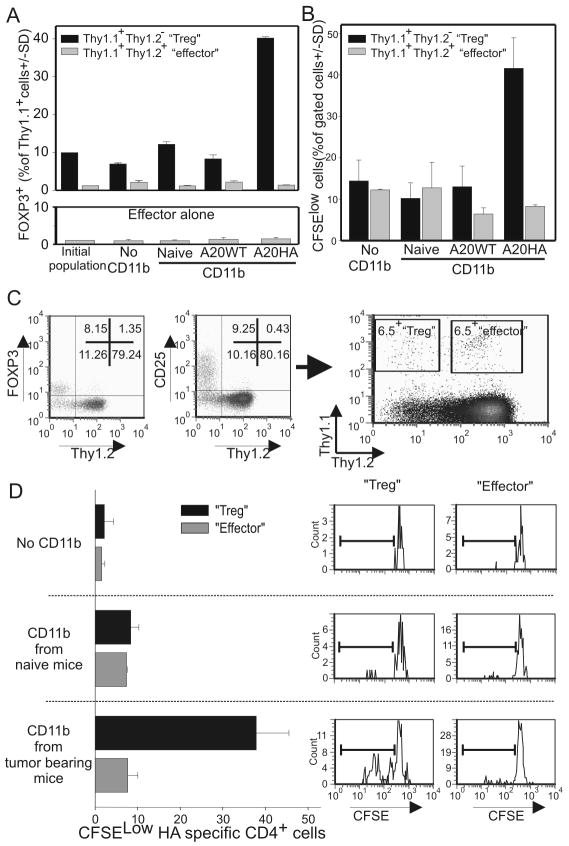

MDSCs expand regulatory T cells from a pre-existing population of natural Tregs

The experiments described above demonstrate that MDSCs can expand the pool of regulatory T cells. However, they do not establish whether this FOXP3+/CFSElow population is derived from the conversion of FOXP3neg, effector T cells or from the selective expansion of a pre-existing population of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells nor whether MDSC-mediated tumor antigen processing and presentation are required. To answer these questions, HA-specific CD4+/CD25+ “Tregs” were purified from Thy1.1+/+/Thy1.2-/- 6.5+ or Thy1.1+/-/Thy1.2-/- 6.5+ tumor free mice and admixed with CD25–depleted, HA-specific CD4+ “effector” T cells from Thy1.1+/-/Thy1.2+/- 6.5+ naïve mice at a 1:10 ratio, respectively. This mixture, in which almost 90% of the FOXP3+ cells are negative for the Thy1.2 marker (Suppl.fig.2), was co-cultured in the absence of exogenous peptide with purified CD11b+cells obtained from: 1) naïve, 2) A20-WT, or 3) A20-HA mice. Two days later, the cells were analyzed for expression of FOXP3, Thy1.1 and Thy1.2. If MDSC-induced Tregs originated from a pre-existing regulatory population (Thy1.1+/+/Thy1.2-/-), most of the FOXP3+ cells on analysis would be Thy1.2 negative. On the contrary, if the generation of Tregs resulted from the conversion of effector T cells (Thy1.1+/-/Thy1.2+/-), the FOXP3+ T cells would be Thy1.2 positive.

As expected, CD11b+ cells from naïve mice did not increase the regulatory T cell pool. Similar results were also obtained with the A20WT-derived MDSCs. In contrast, A20-HA-derived CD11b+ cells expanded FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells (Fig.4A upper panel and Suppl.Fig.2). The fact that Treg expansion can be induced only by CD11b+ cells isolated from A20-HA bearing mice and not A20WT invokes the role of cross-presentation of tumor antigens by MDSCs as the critical requirement for Treg proliferation. Moreover, since most newly generated FOXP3+ cells are Thy1.2 negative, this result strongly suggests that MDSCs mediate Treg expansion from a pre-existing natural Treg population and not by conversion of naïve/effector T cells. This finding is supported by: 1) the absence of any significant increase in the percentage of FOXP3+ cells when regulatory T cells are depleted (Fig.4A lower panel); and 2).the CFSE analysis demonstrating the selective proliferation of the preexisting Thy1.2neg regulatory population (Fig.4B)

Figure 4. Expanded Treg are derived from a preexisting regulatory pool and not from the conversion of FOXP3neg CD4+ T cells.

A) HA-specific CD4+/CD25+ T cells (104) isolated from Thy1.1+/+ 6.5 mice and CD4+CD25- T cells purified from Thy1.1+/-/Thy/1.2+/- 6.5 mice (105) were cultured with Thy1.2+/+ Balb/c splenocytes (106) and with splenic CD11b+ cells (105) magnetically purified from the spleens of mice injected with PBS, A20HA or A20WT 28 days prior. No exogenous peptide was added to the culture. Five days later cells were labeled with anti thy1.1, anti thy1.2 and FOXP3 antibodies and analyzed by FACS. Average +/- SD of triplicate wells was analyzed by gating either on the thy1+thy1.2- population (black bar) or on the Thy1.1+/Thy1.2+ population (gray bar) from the mixture culture (upper panel) or on CD25-depleted, HA-specific, CD4+ T cells cultured with the same CD11b+ cells (lower panel-effector alone). B) The experiment was repeated with CFSE labeling of T cells. Proliferation was determined by CFSE dilution on either the CD4+ Thy1.1+/Thy1.2- “Treg” population (black bars) or on the Thy1.1+/Thy1.2+ “effector” population (gray bars). C) HA-specific CD4+CD25+T cells isolated from Thy1.1+/+ Thy1.2-/-6.5 mice were admixed (1:10 ratio) with CD4+CD25- T cells sorted from Thy1.1+/-/Thy/1.2+/- 6.5 mice (left panel). This mixture was CFSE labeled and injected alone or with purified CD11b+ cells from mice injected with A20-HA or A20WT 28 days prior in a 1:1 ratio into Thy1.2 Balb/c mice. Splenocytes were examined three days later for Thy1.1 and Thy1.2 expression (right panel). Adoptively transferred “Tregs” can be identified as the Thy1.1+/Thy1.2- population while “effector” T cells by co-expression of Thy1.1 and Thy1.2. Proliferation of each population was determined by CFSE dilution. (D) 106 splenocytes were acquired and analyzed. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD of 3 mice.

For in vivo confirmation of the above-mentioned in vitro findings, HA-specific, CD4+/CD25+ “regulatory” T cells (Thy1.1+/+Thy1.2-/-) purified from naïve mice were admixed at a 1:10 ratio with CD25-depleted, HA-specific, CD4+ effector T cells (Thy1.1+/- /Thy1.2+/-) as previously described. This mixture was CFSE labeled and injected into Thy1.2+/+ BALB/c mice alone or with naïve or A20-HA-derived CD11b+ cells (Fig.4C left panels). In this system, adoptively transferred “effector” clonotypic T cells co-express both the Thy1.1 and Thy1.2 congenic markers. “Regulatory” clonotypic T cells are only positive for the Thy1.1 marker and the host T cells are negative for Thy1.1 expression (Fig 4C right panel). Splenocytes were harvested 60 hours later and the CFSE dilution was analyzed by gating on either the adoptively transferred Thy1.1+/Thy1.2- “Tregs” (Fig.4C upper left quadrant) or Thy1.1+/Thy1.2+ “effector” T cells (Fig.4C upper right quadrant). The control groups (no CD11b or CD11b cells isolated from naïve mice) showed virtually no proliferation of the adoptively transferred T cells. In contrast, co-injection of T cells with tumor-derived CD11b+ cells preferentially expanded the Thy1.1+/Thy1.2neg “Treg” population but not the effector T cells (Fig.4D). These data confirm the in vitro findings by showing that MDSCs induce the proliferation of tumor specific regulatory T cell.

These results strongly suggest that MDSCs play an important role in inducing regulatory T cell expansion but not in the conversion of regulatory FOXP3+ T cells from FOXP3neg effector T cells by a mechanism that requires tumor associated antigen capture, processing and presentation by MDSCs.

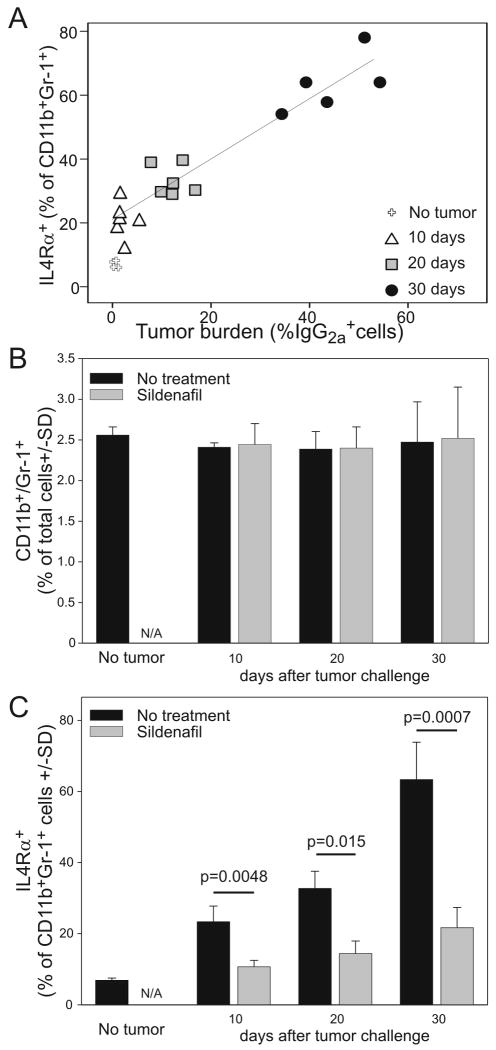

IL4Rα expression on MDSCs correlates with tumor progression and can be inhibited by sildenafil

Recently we showed that IL4Rα expression plays an important role in MDSC mediated T cell suppression in solid tumors (17). Genetic ablation of this marker on macrophages and granulocytes is, in fact, sufficient to restore not only anti-tumor T cell responsiveness but also efficacy of adoptively transferred, tumor-primed, CD8+ T cells(17). Similar results can be obtained by the pharmacological inhibition of PDE5 using sildenafil (Viagra®)(22). Since IL4Rα is also expressed on lymphoma-derived MDSCs (Fig.1) we asked whether sildenafil could alter its expression on MDSCs during lymphoma progression. In splenocytes from A20-HA bearing mice, we examined whether the presence of MDSCs correlated with tumor burden at various time points following tumor challenge. MDSCs defined by the classical markers CD11b and Gr1 do not accumulate during tumor progression (Fig.5B) and their numbers in the spleen do not correlate with tumor burden (Suppl. Fig.3). In contrast, IL4Rα up-regulation on MDSCs significantly correlates with tumor progression (Spearman p value >0.001) (Fig.5A,C). This finding supports the notion that the growing tumor burden is associated with increases in the suppressive phenotype of MDSCs but not with their accumulation in the secondary lymphoid organs in the A20 model. Although interesting, this phenomenon is not unique to lymphoid malignancies since similar findings were also seen in the 15-12RM fibrosarcoma model (19).

Figure 5. IL4Rα expression on CD11b+ cells correlates with tumor progression and can be down-modulated by sildenafil.

Mice were injected on day 0 with 106 A20-HA cells and either treated with sildenafil or left untreated. At the indicated time points, mice were sacrificed and splenocytes analyzed by FACS for (A) IgG2a expression - as a measure of tumor burden, or (B, C) for the co-expression CD11b, Gr1 and IL4Rα to determine MDSC expansion.

Based on our data showing that sildenafil can down-regulate IL4Rα expression on MDSCs in solid tumors (22), we examined its role during B-cell lymphoma progression. As expected, sildenafil effectively down-regulates IL4Rα expression on lymphoma-derived MDSCs (Fig.5C). However, in contrast to its measurable anti-tumor effect in solid tumors (22), it does not significantly reduce A20HA tumor outgrowth (data not shown). This contradictory result can possibly be explained in several ways: 1) Immune-mediated eradication is primarily a CD4 and not CD8-dependent process (26) and sildenafil has less effect on activating CD4 compared to CD8 effector T cells (22); or 2) The possibility that other immunosuppressive pathways are also present in the A20 system such as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase(IDO), the expression of which can convert effector T cells into Tregs and thus regulate the immune response during lymphoma progression (27).

Taken together, these data show that: 1) IL4Rα expression on MDSCs correlates with A20-HA lymphoma progression; and 2) in vivo sildenafil administration can down-regulate IL4Rα expression.

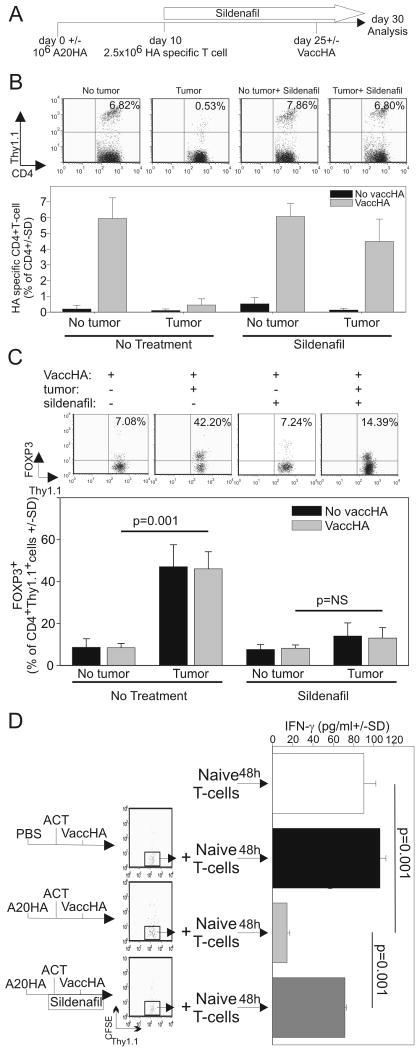

Sildenafil reduces lymphoma-induced T cell anergy and regulatory T cell expansion

The data described above underscores the ability of lymphoma-induced MDSCs to cross-present tumor antigens to regulatory T cells (Fig.1, 3, 4) through an arginase dependent mechanism (Fig.3B). Since most MDSC suppressive pathways can be inhibited by down-regulating IL4Rα (17, 22, 28, 29), we asked if sildenafil could also reverse tumor-induced T cell anergy and regulatory T cell proliferation. To this end, mice were either challenged with A20-HA or left tumor-free and given purified Thy1.1+, HA-specific, CD4+ T cells 10 days later. Sildenafil was added to the drinking water of half the animals at the time of T cell transfer. Two weeks later, half the mice in each group were primed with VaccHA (Fig 6A). Clonal expansion (Fig.6B) as well as FOXP3 expression (Fig.6C) was evaluated 5 days after VaccHA priming. While VaccHA immunization induced a robust expansion of clonotypic T cells in naïve mice, antigen driven proliferation was strongly inhibited in tumor-bearing mice (Fig.6B). Interestingly, sildenafil was sufficient to restore the proliferative capacity of otherwise anergic tumor-specific T cells in tumor-bearing mice. As previously reported (10, 11), T cell anergy correlated with FOXP3 expression. In fact, more then 40% of the adoptively transferred clonotypic T cells were FOXP3+ in the tumor-bearing mice. In the absence of tumor, Tregs represented only 5-10% of the clonotypic T cells. Interestingly, sildenafil administration to A20-HA bearing mice reduced FOXP3+ T cell expansion in tumor-specific T cells to approximately 14% (Fig.6C).

Figure 6. In vivo sildenafil administration reduces Treg proliferation and prevents T cell anergy.

A) Experimental schema. Mice were injected with A20-HA (106cells) or PBS on day 0. All the mice received 2.5×106 HA-specific, Thy1.1+/+, CD4 purified T cells on day 10 and half were then administered sildenafil in the drinking water. On day 25 half of the mice in each group were vaccinated with VaccHA (107 PFU) and sacrificed 5 days later. (B) clonal expansion and (C) FOXP3 expression was evaluated by FACS analysis. (D) The experiment was repeated as described above with CFSE labeled clonotypic T cells. CD4+ T cells were purified on day 30 and CD4+/Thy1.1+/CFSElow cells were further purified by cell sorting. To evaluate their suppressive activity, 3×104 CFSElow cells were co-cultured with naïve HA-specific T cells in the presence of the relevant peptide and irradiated BALB/c splenocytes as feeder cells. IFN-γ production was evaluated 48h later by ELISA.

In this tumor model, the majority of CFSElow clonotypic T cells harvested on day 30 expressed high levels of GITR and FOXP3, and suppressed the effector function of naïve T cells consistent with a regulatory T cell phenotype (10, 11). To confirm these previous findings and to evaluate the impact of sildenafil on regulatory T cell expansion, thirty days after transfer, HA-specific CFSElow CD4+ Thy1.1+/+ T cells were isolated from A20-HA-bearing mice (Fig.6A). CFSElow purified T cells were obtained from: 1) tumor-free; 2) tumor-bearing; or 3) tumor-bearing, sildenafil treated mice were admixed with naïve HA-specific, CD4+ T cells (CFSElow/naïve T cell 1:3 ratio) in the presence of the cognate peptide (Fig.6D). IFN-γ production from naïve T cells was significantly impaired in the presence CFSElow cells from A20-HA-bearing mice but not with CFSElow cells from non tumor-bearing donors. Sildenafil nearly completely eliminated the regulatory T cell phenotype of the A20HA CFSElow cells.

These data provide evidence that PDE5 inhibition can profoundly abrogate Treg expansion and overcome T cell anergy in this model. Moreover, considering that the primary cellular target of sildenafil is likely the MDSC and not T cells (22), these data again point to the myeloid suppressor population as the mediator of tumor-induced T cell anergy.

Discussion

The early events in tumor-specific T cell anergy involve interactions in an increasingly complex immunosuppressive network through mechanisms including cross-presentation by functionally impaired host APCs (12, 13, 30, 31) and expansion of regulatory T cells (10, 11). Both expansion of a pre-existing regulatory cell pool and the de novo generation of Tregs from FOXP3neg cells can contribute to tumor-specific T cell tolerance (11). In the A20 lymphoma model, the conversion of CD4+CD25neg cells into CD4+CD25+ Tregs has been recently associated with tumor associated indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression (27). Here we showed that the expansion of a pre-existing pool of Tregs can be mediated by MDSCs.

While considerable evidence exists pointing to an important role of MDSCs in the generation of cancer-induced immune suppression, their exact role within this network remains unclear. Using the A20 lymphoma model stably, we show that MDSCs are the tolerogenic APCs that induce antigen-specific T cell tolerance. This occurs preferentially through cross-presentation of tumor antigens resulting in the subsequent expansion of the pre-existing natural regulatory T cells and not the generation of de novo Tregs. Although extensively studied, the role of MDSCs has thus far been only described in solid tumors (14) or in subcutaneous lymphoma models (32). In those models, MDSCs generally expand in secondary lymphoid organs and in the tumor bed where they suppress the tumor-specific T cell response by mechanisms requiring TGF-β secretion (19), arginase induction (25),(33), and/or nitric oxide production (21).

Here for the first time we describe a role for MDSCs in a systemic hematopoietic malignancy, A20 B cell lymphoma. In our model, MDSCs fail to expand during tumor progression (Fig.5B). Interestingly, however, they acquire IL4Rα expression during tumor progression – a critical requirement for MDSC mediated suppression (17). IL4Rα up-regulation on MDSCs during lymphoma progression strongly suggests that systemic tumor outgrowth does not affect MDSC recruitment but rather their differentiation toward a suppressive phenotype. This is supported by our in vitro data showing that MDSCs isolated from lymphoma-bearing mice acquire arginase activity (Fig.2B), the ability to secrete NO (Fig.2B) and the capacity to suppress CD8 T cell proliferation (Fig.2A). Underscoring the critical role of these cells is the recent demonstration that antigen specific CD8 tolerance is induced by MDSC-mediated nitrosylation of tyrosine residues on the CD8 TCR (34). In fact, the genetic disruption in macrophages and neutrophils (17), or pharmacological inhibition (22, 28) of this marker on MDSC is sufficient to revert their suppressive activities and to re-establish tumor immune surveillance.

Considerable interest exists in establishing links between the various immunosuppressive pathways such as MDSCs and Tregs. MDSCs, in fact, share many features with immature DCs (e.g. low expression of MHC class II, expression of CD80, the ability for antigen uptake etc.) that are often associated with either T cell tolerization or Treg expansion (30). In an allogeneic bone marrow transplant setting, the transfer of MDSCs into recipient mice suppressed the initiation of GVHD through Treg induction (23). Moreover, using a murine melanoma model and a rat colon carcinoma model, Ghiringhelli et al. elegantly showed that TGF-β producing CD11b+/CD11c+/MHC Class IIlow cells were responsible for Treg expansion both intratumorally and in the draining lymph nodes (35).

Our data not only confirm previous results in solid tumors but also extend these observations to a hematologic malignancy and provide evidence as to the putative mechanisms involved. MDSCs isolated from A20-HA bearing mice expand the pre-existing regulatory T cell pool even in the absence of exogenous peptide (Fig.3).

Furthermore, by analyzing the effect of A20HA-derived MDSCs and DCs we provide new data supporting the hypothesis that different APC populations significantly influence the resultant immune response (36). In fact, while CD11chighMHC Class IIhigh DCs from A20HA tumor bearing mice stimulate effector CD4+ T cell proliferation, MDSCs promote Treg expansion (Fig.3B). These findings suggest that the relative number of each population can determine the immunological outcome. Accordingly, in the spleens of mice challenged with A20HAGFP 28 days prior, MDSCs loaded with the antigen (Suppl.fig.4) greatly outnumbered their DC counterparts (GFP+CD11bhigh =2.93% vs. GFP+CD11chigh =0.02%)

Contrary to previous reports, various pieces of evidence seem to exclude a predominant role of TGF-β in Treg expansion in our model: 1) the presence of tumor does not significantly increase TGF-β production by MDSCs (Fig.2B); 2) the addition of an anti-TGF-β neutralizing antibody to the culture fails to inhibit FOXP3+ T cell expansion (Fig.3C); 3) in vivo anti TGF-β administration fails to reverse either T cell anergy or Treg expansion (Suppl. Fig.5). Although these differences can be attributable to intrinsic differences in the tumor type (solid vs hematologic), the compartment (lymph nodes vs spleen), or the background of the mice (C57Bl/6 vs BALB/c), this data clearly indicate that MDSCs can regulate Treg homeostasis through TGF-β independent mechanisms. The fact that the addition of NOHA reverses MDSC-mediated Treg expansion (Fig.3B) suggests that this process is arginase dependent. Arginase expression plays an important role in MDSC mediated suppression of CD8+ T cell proliferation either in concert with NOS to generate peroxynitrite (25) or by depleting the microenvironment of the semi-essential amino acid L-arginine (33). Our data suggests a new scenario whereby modulation of Treg expansion through arginase metabolism controls effector T cell function.

Interestingly, differences in the mechanisms used by MDSCs to suppress CD8+ effector function and to induce CD4+ Treg proliferation emerged. While Arg1 and NO production are both required to suppress CD8+ proliferation, CD4+ Treg proliferation appears to only require arginase activity. Several hypotheses can explain these results: 1) CD4+ and CD8+ cells are differentially susceptible to L-arginine deprivation (37). L-arginine has, in fact, been shown to be important for CD8+ T cell proliferation, while L-arginine depletion does not inhibit CD4 proliferation. Similarly, CD4+ proliferation is unaltered in the presence or absence of NOS2 while CD8+ expansion is greatly inhibited (38). 2) Through L-ornithine, arginase can generate polyamines with different outcomes on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells signaling. For example, putresceine can alter the Ca2+ influx in ConA stimulated CD4+ T cells while no effect is observed in CD8+ T cells (39). Finally 3), arginase can induce MDSCs to produce superoxide that may have different effects on effector or regulatory T cells. Superoxide can anergize activated effector cells by lowering the affinity of the TCR(34). Furthermore, by down-regulating PTEN expression (40), it can possibly restore the ability of Tregs to respond to IL-2 and to proliferate (41). However, further studies are required to understand which, if any, of these pathways regulate Treg proliferation.

Although the connection between MDSCs and Tregs has been previously suggested (24), it is still unclear whether MDSCs increase Treg numbers through the conversion of naïve T cells or the expansion of a pre-existing antigen specific regulatory T cell population. Using a system whereby the regulatory and effector populations are distinguished by the presence of the congenic markers Thy1.1 and Thy1.2, tumor-derived MDSCs expand the pre-existing regulatory T cell population rather then convert naïve T cells into regulatory ones in vitro (Fig 4B,C). Moreover, we extend these findings to our in vivo model (Fig 4D). By co-transferring A20-HA-derived MDSCs and regulatory Thy1.1+/Thy1.2- FOXP3+ as well as effector Thy1.1+/Thy1.2+ CD25-/FOXP3- T cells into naïve mice, we were able to demonstrate the expansion of the pre-existing Tregs. Considering that these adoptive transfer experiments were subsequently performed in non tumor-bearing mice and thus removed from their tumor-induced immunosuppressive micro-environment, we show that A20-HA-derived MDSCs are sufficient per se to induce the proliferation of HA-specific Tregs.

We previously showed that PDE5 inhibition with sildenafil (Viagra®) can restore tumor immunity by reversing the MDSC-mediated suppressive pathways in solid tumors (22). Here we extend these findings to lymphoma. Sildenafil treatment down-regulated IL4Rα on MDSCs (Fig.5), reduced the number of tumor-specific Tregs and reverted tumor-induced T cell anergy (Fig.6). These data indicate that sildenafil can effectively reverse the immunosuppressive state in hematological malignancies and provides additional confirmation that MDSCs play a central role in Treg induction and T cell anergy. While we cannot fully exclude that sildenafil acts solely on MDSCs, our data would suggest that it does not directly augment T cell function. However, PDE5 inhibition may interfere with other immunosuppressive pathways in vivo that ultimately reduce T cell tolerance and improve effector T cell function. This hypothesis, however, requires further investigation.

Finally, it must be pointed out that despite sildenafil treatment, 14% of the clonotypic T cells remain FOXP3+ as compared to the 5-10% present in the non-tumor bearing mice. Although this can be attributable to the incomplete pharmacologic inhibition of PDE5, an intriguing hypothesis is that this increase derived from A20HA-mediated IDO activity converted effector cells into regulatory ones (27)

In conclusion, our findings describe a tight inter-relationship between host tumor-derived MDSCs, Treg induction (10, 11), and antigen-specific T cell anergy (8, 9, 42) responsible for the immunosuppressive state associated with an increasing tumor burden in lymphoma-bearing mice. Furthermore, by demonstrating the ability to pharmacologically reverse this tolerogenic process through the functional blockade of tumor-derived MDSCs, we point to a critical role of MDSCs in mediating immune suppression and provide new hope for the immunological treatment of hematological malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Diana Lopez for her critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by NIH grant 1 R01 CA124996-01A1.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Eisen HN, Sakato N, Hall SJ. Myeloma proteins as tumor-specific antigens. Transplant Proc. 1975;7:209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janeway CA, Jr, Sakato N, Eisen HN. Recognition of immunoglobulin idiotypes by thymus-derived lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:2357–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.6.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultze JL, Cardoso AA, Freeman GJ, et al. Follicular lymphomas can be induced to present alloantigen efficiently: a conceptual model to improve their tumor immunogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8200–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longo DL. Lymphoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 1997;9:389–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glimcher LH, Kim KJ, Green I, Paul WE. Ia antigen-bearing b cell tumor lines can present protein antigen and alloantigen in a major histocompatibility complex-restricted fashion to antigen-reactive T cells. 1982;155:445–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.2.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss, Bogen B. B-lymphoma cells process and present their endogenous immunoglobulin to major histocompatibility complex-restricted T cells. 1989;86:282–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Bendandi M, Deng Y, et al. Tumor-specific recognition of human myeloma cells by idiotype-induced CD8(+) T cells. Blood. 2000;96:2828–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staveley-O'Carroll K, Sotomayor E, Montgomery J, et al. Induction of antigen-specific T cell anergy: An early event in the course of tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1178–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sotomayor EM, Borrello I, Tubb E, et al. Conversion of tumor-specific CD4+ T-cell tolerance to T-cell priming through in vivo ligation of CD40. Nat Med. 1999;5:780–7. doi: 10.1038/10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou G, Drake CG, Levitsky HI. Amplification of tumor-specific regulatory T cells following therapeutic cancer vaccines. Blood. 2006;107:628–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou G, Levitsky HI. Natural regulatory T cells and de novo-induced regulatory T cells contribute independently to tumor-specific tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;178:2155–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horna P, Cuenca A, Cheng F, et al. In vivo disruption of tolerogenic cross-presentation mechanisms uncovers an effective T-cell activation by B-cell lymphomas leading to antitumor immunity. Blood. 2006;107:2871–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sotomayor EM, Borrello I, Rattis FM, et al. Cross-presentation of tumor antigens by bone marrow-derived antigen-presenting cells is the dominant mechanism in the induction of T-cell tolerance during B-cell lymphoma progression. Blood. 2001;98:1070–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serafini P, Borrello I, Bronte V. Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: recruitment, phenotype, properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bronte V, Apolloni E, Cabrelle A, et al. Identification of a CD11b+/Gr-1+/CD31+ myeloid progenitor capable of activating or suppressing CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2000;96:3838–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. STAT1 signaling regulates tumor-associated macrophage-mediated T cell deletion. J Immunol. 2005;174:4880–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallina G, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, et al. Tumors induce a subset of inflammatory monocytes with immunosuppressive activity on CD8 T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2777–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI28828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apolloni E, Bronte V, Mazzoni A, et al. Immortalized myeloid suppressor cells trigger apoptosis in antigen- activated T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;165:6723–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terabe M, Matsui S, Park JM, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta production and myeloid cells are an effector mechanism through which CD1d-restricted T cells block cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated tumor immunosurveillance: abrogation prevents tumor recurrence. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1741–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Serafini P, De Santo C, Marigo I, et al. Derangement of immune responses by myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:64–72. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:641–54. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serafini P, Meckel K, Kelso M, et al. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition augments endogenous antitumor immunity by reducing myeloid-derived suppressor cell function. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2691–702. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacDonald KP, Rowe V, Clouston AD, et al. Cytokine expanded myeloid precursors function as regulatory antigen-presenting cells and promote tolerance through IL-10-producing regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:1841–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, et al. Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1123–31. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bronte V, Serafini P, De Santo C, et al. IL-4-induced arginase 1 suppresses alloreactive T cells in tumor- bearing mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:270–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lundin KU, Hofgaard PO, Omholt H, Munthe LA, Corthay A, Bogen B. Therapeutic effect of idiotype-specific CD4+ T cells against B-cell lymphoma in the absence of anti-idiotypic antibodies. Blood. 2003;102:605–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curti A, Pandolfi S, Valzasina B, et al. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by human leukemic cells results in the conversion of CD25- into CD25+ T regulatory cells. Blood. 2007;109:2871–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terabe M, Matsui S, Noben-Trauth N, et al. NKT cell-mediated repression of tumor immunosurveillance by IL-13 and the IL-4R-STAT6 pathway. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:515–20. doi: 10.1038/82771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinha P, Clements VK, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Reduction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and induction of M1 macrophages facilitate the rejection of established metastatic disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:636–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabrilovich D. Mechanisms and functional significance of tumour-induced dendritic-cell defects. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:941–52. doi: 10.1038/nri1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fricke I, Gabrilovich DI. Dendritic cells and tumor microenvironment: a dangerous liaison. Immunol Invest. 2006;35:459–83. doi: 10.1080/08820130600803429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Van Ginderachter JA, Brys L, De Baetselier P, Raes G, Geldhof AB. Nitric oxide-independent CTL suppression during tumor progression: association with arginase-producing (M2) myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:5064–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Zabaleta J, et al. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5839–49. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagaraj S, Gupta K, Pisarev V, et al. Altered recognition of antigen is a mechanism of CD8+ T cell tolerance in cancer. Nat Med. 2007;13:828–35. doi: 10.1038/nm1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghiringhelli F, Puig PE, Roux S, et al. Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF-beta-secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:919–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morelli AE, Coates PT, Shufesky WJ, et al. Growth factor-induced mobilization of dendritic cells in kidney and liver of rhesus macaques: implications for transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83:656–62. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000255320.00061.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochoa JB, Strange J, Kearney P, Gellin G, Endean E, Fitzpatrick E. Effects of L-arginine on the proliferation of T lymphocyte subpopulations. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2001;25:23–9. doi: 10.1177/014860710102500123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffman RA, Mahidhara RS, Wolf-Johnston AS, Lu L, Thomson AW, Simmons RL. Differential modulation of CD4 and CD8 T-cell proliferation by induction of nitric oxide synthesis in antigen presenting cells. Transplantation. 2002;74:836–45. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas T, Gunnia UB, Yurkow EJ, Seibold JR, Thomas TJ. Inhibition of calcium signalling in murine splenocytes by polyamines: differential effects on CD4 and CD8 T-cells. Biochem J. 1993;291(Pt 2):375–81. doi: 10.1042/bj2910375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim S, Clement MV. Phosphorylation of the survival kinase Akt by superoxide is dependent on an ascorbate-reversible oxidation of PTEN. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1178–92. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bensinger SJ, Walsh PT, Zhang J, et al. Distinct IL-2 receptor signaling pattern in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:5287–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sotomayor EM, Borrello I, Levitsky HI. Tolerance and cancer: a critical issue in tumor immunology. Crit Rev Oncog. 1996;7:433–56. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v7.i5-6.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.