Abstract

The ongoing characterization of the genetic and epigenetic alterations in the gliomas has already improved the classification of these heterogeneous tumors and enabled the development of rodent models for analysis of the molecular pathways underlying their proliferative and invasive behavior. Effective application of the targeted therapies that are now in development will depend on pathologists’ ability to provide accurate information regarding the genetic alterations and the expression of key receptors and ligands in the tumors. Here we review the mechanisms that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of the gliomas and provide examples of the cooperative nature of the pathways involved, which may influence the initial therapeutic response and the potential for development of resistance.

Keywords: glioblastoma, astrocytoma, genetic alterations, signaling pathway alterations

GLIOMAS

Introduction and Histological Classification

The most common primary brain tumor is the glioma. Histologically, gliomas can resemble astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or ependymal cells; thus, on the basis of their morphologic appearance they are classified as astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, or ependymomas, respectively (1–5). Astrocytomas express glial fibrillary acidic protein, an intermediate filament found in astrocytes that is routinely used as an aid in classifying a glioma as an astrocytoma. Because astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas account for the vast majority of gliomas, we focus on these two types in this review.

Primary brain tumors account for 1.4% of all cancers and 2.4% of all cancer deaths in the United States, and approximately 20,500 newly diagnosed cases and 12,500 deaths are attributed to primary malignant brain tumors each year (see http://www.cbtrus.org). The risk factors for the development of a glioma are not clear, but occupational exposure to organic solvents or pesticides appears to be a predisposing factor (6; http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/brain). It has also been suggested that cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection may play a role in the etiology or progression of some gliomas, based on detection of CMV RNA in glioblastoma (GBM) tumors (7). There are two peak incidences of gliomas, one in the age group of 0 to 8 years (8) and the second in the age group of 50 to 70 years (5), and there is a slight male predominance (9).

The symptoms of patients presenting with a glioma depend on the anatomical site of the glioma in the brain and can include headaches; nausea or vomiting; changes in speech, vision, hearing, or balance; mood and personality alterations; seizures or convulsions; and memory deficits (see http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/brain). The time frame of the onset of symptoms depends in part on the grade of the glioma; with GBM tumors the onset of symptoms is typically rapid. Surgical biopsy is necessary to determine whether the tumor is a primary brain tumor and to diagnose the tumor type and grade.

Glioma tumors are histologically separated into Grades I through IV according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. Grade I tumors typically have a good prognosis and more frequently occur in children (5, 8), and Grade II tumors are characterized on histologic examination by hypercellularity: These Grade II tumors have a 5–8-year median survival. Grade III astrocytoma tumors (anaplastic astrocytoma tumors) are characterized on histologic examination according to hypercellularity, as well as nuclear atypia and mitotic figures (see Figure 1). Anaplastic astrocytoma has a 3-year median survival (10–14). Grade IV gliomas, also known as GBMs, are characterized on histologic examination according to hypercellularity, nuclear atypia, mitotic figures, and evidence of angiogenesis and/or necrosis (see Figure 2). The median survival for patients with GBM tumors is 12–18 months (5, 15), and older patients (>60 years of age) typically have a survival that is somewhat shorter than the median.

Figure 1.

Anaplastic astrocytoma (World Health Organization Grade III). A mitotic figure is shown in the bottom center of the photomicrograph, and tumor nuclei are pleomorphic. Both are typical of an anaplastic astrocytoma.

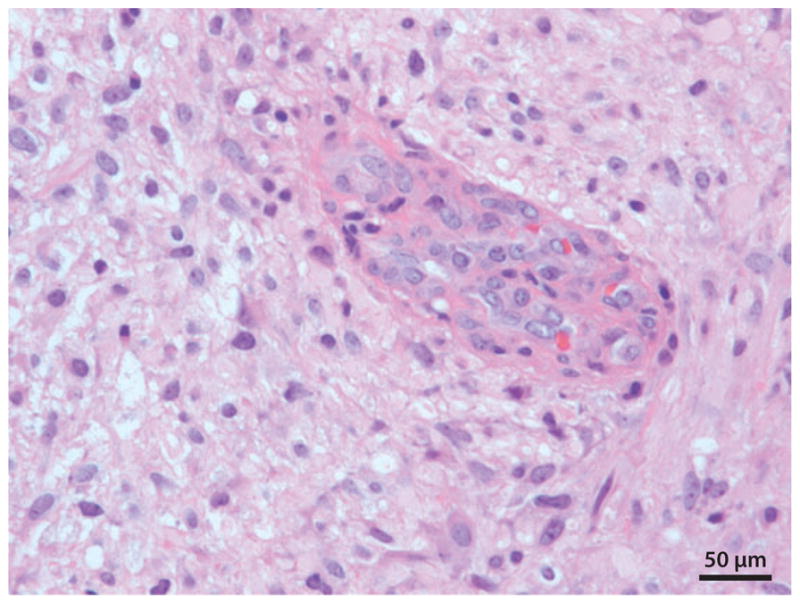

Figure 2.

Glioblastoma tumor (World Health Organization Grade IV). Endothelial cell proliferation (angiogenesis) is shown in the center of this photomicrograph.

Oligodendroglioma tumors are histologically separated into Grades II and III according to the WHO criteria. The Grade II tumors exhibit hypercellularity and bland nuclei on histologic examination (see Figure 3), and the Grade III tumors (anaplastic oligodendrogliomas) exhibit the additional histologic features of prominent mitotic figures and evidence of angiogenesis (see Figure 4) (5).

Figure 3.

Oligodendroglioma (World Health Organization Grade II). The cleared cytoplasm and bland monomorphic nuclei typical of an oligodendroglioma are shown in this photomicrograph.

Figure 4.

Anaplastic oligodendroglioma (World Health Organization Grade III). Nuclear atypia and endothelial cell proliferation (angiogenesis) typical of an anaplastic oligodendroglioma are shown in this photomicrograph.

Major Genetic Alterations

The ongoing characterization of the genetic alterations in glioma tumor cells is revealing considerable variability among tumors of the same type and grade. This heterogeneity may contribute to the current limitations in predicting patient survival on the basis of histologic analysis of glioma type and grade alone (1–5) and suggests that classification of certain types and grades of gliomas according to their genetic phenotype will lead to a more accurate prediction of survival and response to therapy (1–4).

Grade I tumors, which are benign, typically do not progress to Grade II, III, or IV tumors, and their genetic alterations are different from those found in the Grade II–IV tumors; thus, they are not discussed herein. Oligodendroglioma (WHO Grade II) and anaplastic oligodendroglioma tumors (WHO Grade III) frequently exhibit loss of heterozygosity (LOH) on chromosomes 1p and 19q (observed in 40%–90% of biopsies, depending on the study) (see Table 1; 1–4). This is the most common genetic alteration found in oligodendroglioma tumors and predicts a favorable response to certain chemotherapeutic agents, a favorable response to radiation therapy, and longer survival even after recurrence (16). Glioma biopsy tissue can be routinely tested for LOH of 1p and 19q by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or by Southern blotting in the pathology laboratory. It is not yet known which genes at the 1p and 19q loci are involved in the promotion of growth of the oligodendroglioma tumors nor how the loss of these genes contributes to a more favorable therapeutic response and a more favorable prognosis (17); however, at least one of these genes may be involved in the initiation of oligodendroglial tumorigenesis (1–4). Another common genetic alteration in oligodendroglial tumors is downregulation of the tumor suppressor and lipid phosphatase PTEN gene. Downregulation of this gene has been found in 50% of these tumors, and this downregulation appears to be a consequence of methylation of the promoter region (18). Amplification of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα) occurs in approximately 7% of oligodendroglial tumors (19, 20).

Table 1.

Common genetic alterations in gliomasa

| Genetic alteration | Normal gene function | Incidence | Laboratory tests | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oligodendrogliomas (WHO Grades II and III) | ||||

| LOH of 1p/19q | Unknown; multiple tumor-suppressor genes at these loci, e.g., DMBT1, Mxi | 40%–90%, depending on the study | aCGH (21, 22) | 1–4, 21, 22 |

| FISH | 21, 22 | |||

| LOH | 21, 22 | |||

| PDGFRα amplification | Stimulates cell proliferation and migration due to an autocrine loop | 7% | aCGH (23) | 19, 20, 23 |

| FISH | 20 | |||

| Southern blot | 20 | |||

| PTEN (10q23) deletion due to LOH of chromosome 10q | Tumor suppressor; negatively regulates AKT signaling | 21% | aCGH (23) | 23, 24 |

| PTEN mutation | Inhibits angiogenesis | 8% | LOH | 24 |

| Poor prognosis if mutation present | SSCP | 23, 24 | ||

| PTEN promoter methylation | Tumor suppressor; negatively regulates AKT signaling | 50% | Methylation-specific PCR (18) | 18 |

| Inhibits angiogenesis | ||||

| Poor prognosis if mutation present | ||||

| Astrocytomas (WHO Grade II) and anaplastic astrocytomas (WHO Grade III) | ||||

| PDGFRα and -β amplification/mutation | Stimulates cell proliferation and migration due to an autocrine loop | PDGFRα (3%–33%) | aCGH (23) | 1–4, 23, 25–27 |

| PDGF-A/-B/-C/-D amplification | Overexpression of PDGF-B can initiate gliomagenesis when expressed in the neural stem/progenitor cell | FISH | 26 | |

| Southern blot | 27 | |||

| p53 mutation (chromosome 17p) | Cell-cycle arrest | Grade II astrocytoma (35%–50%) | PCR-DGGE (28) | 1–4, 28, 29 |

| PCR-SSCP | 29 | |||

| Rb deletion or mutation (chromosome 13q14) | Regulates cell-cycle progression | LOH (30%) | LOH (30) | 1–4, 30–33 |

| Mutation (13%–25%) | PCR-SSCP | 30, 33 | ||

| Deletion or mutation of p16INK4A/CDKN2A due to either loss of chromosome 9p or hypermethylation | Encodes p16 and ARF genes | Anaplastic astrocytoma (12%–62.5%) | LOH (34–36) | 1, 34–36 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor | ||||

| MDM2 amplification or mutation (chromosome 12q) | P53 regulator | Anaplastic astrocytoma (13%–43%) | Southern blot (37) | 37–40 |

| aCGH (41) | ||||

| Loss of chromosome 22q and gain of 7q | Unknown | Grade II astrocytoma (20%–30% of all gliomas) | LOH (42, 43) | 42, 43 |

| PTEN promoter methylation | Tumor suppressor; negatively regulates AKT signaling | 43% | Methylation-specific PCR (18) | 18 |

| Inhibits angiogenesis | ||||

| Poor prognosis if mutation present section | ||||

| c-Kit (4q12) | Class III receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) | 6%–28% | FISH (26, 44) | 26, 44 |

| Oncogene to promote tumorgenesis | ||||

| Glioblastomas (WHO Grade IV) | ||||

| EGFR amplification (aneuploidy of chromosome 7)/gain-of-function mutation (in frame deletion of exons 2–7 on chromosome 7) | Promotes cell proliferation, invasion, and angiogenesis | Primary GBM (36%–60%), secondary GBM (8%) | Southern (45) | 3, 31, 32, 45–48 |

| Induces resistance to apoptosis | Anaplastic Astrocytomas (15%) | aCGH | 48 | |

| May mediate radiation resistance | – | – | – | |

| PTEN (10q23) deletion due to LOH of chromosome 10q or mutation, or methylaton of PTEN promoter | Tumor suppressor; negatively regulates AKT signaling | LOH: primary GBM (47%–70%), secondary GBM (54%–63%) | aCGH (23) | 46, 47 |

| Inhibits angiogenesis | Mutation: primary GBM (14%–47%) | LOH (24) | 46, 47, 49–51 | |

| Poor prognosis if mutation present | Secondary GBM (4%) | SSCP (23, 24) | 18 | |

| PTEN promoter methylation: primary GBM (9%) | Methylation-specific PCR | 18 | ||

| PDGFR-α and -β (4q12) amplification | Stimulates cell proliferation and migration due to an autocrine loop | Primary GBM (20%–29%) | FISH (44) | 1–4, 14, 25, 27, 44, 52 |

| Overexpression of PDGF-B can initiate gliomagenesis when expressed in the neural stem and progenitor cell | Secondary GBM (60%) | Southern blot | 27 | |

| p53 mutation (chromosome 17p) | Cell-cycle arrest | Primary GBM (28%) | PCR-DGGE (28) | 28, 29, 32, 53 |

| Secondary GBM (65%) | PCR-SSCP | 29, 53 | ||

| Rb deletion or mutation (chromosome 13q14) | Regulates cell-cycle progression | Secondary GBM (40%) | LOH (30) | 1–4, 30–33 |

| PCR-SSCP | 30, 33 | |||

| DMBT1 deletion due to LOH of chromosome 10q | Homolog of the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich (SRCR) superfamily | LOH (59% of all GBM) | Differential duplex PCR (54) | 54 |

| Potential tumor suppressor | Homozygous deletion (22% of all GBM) | – | – | |

| Mxi1 (10q25 deletion) due to LOH of chromosome 10q | Putative tumor suppressor, potent antagonist of Myc oncogene | LOH (65% of all GBM) | Genomic PCR (55) | 17, 55 |

| MDM2 amplification or mutation | P53 regulator | 10%–15% | Southern (32, 37, 56, 57) | 32, 37, 38, 56, 57 |

| KIT (4q12) | Class III receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) | 15% | MLPA (58) | 58 |

| Oncogene; promotes tumorgenesis | ||||

| MGMT promoter methylation (chromosome 10q) | DNA-repair enzyme | Primary GBM (36%) | Chromatin accessibility assay (59) | 32, 59–62 |

| Secondary GBM (75%) | Methylation-specific PCR | 59, 62 | ||

Abbreviations: aCGH, array comparative genomic hybridization; CDKN, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor; DMBT, deleted in malignant brain tumors; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; GBM, glioblastoma; c-Kit, Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral homolog; LOH, loss of heterozygosity analysis; MDM2, ouse double minute 2 homolog; MGMT, O6-methylguanine–DNA methyltransferase; MLPA, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification; Mxi1, max interactor 1; PCR-DGGE, polymerase chain reaction–based denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PDGFR, PDGF receptor; PTEN, lipid phosphatase and tensin homolog; Rb, retinoblastoma gene; SSCP, single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis.

Astrocytoma tumors (WHO Grade II) frequently (3%–33%) exhibit amplification of the PDGFRα and/or PDGFRβ genes and of the genes encoding their ligands, PDGF-A and -B or -C and -D (1–4, 14, 25, 52). The amplification of the PDGFRα gene may result from amplification of chromosome 4q12 (14, 25, 52). These genetic alterations probably play an important role in gliomagenesis, given that retroviral expression of PDGF-B in neural progenitor cells can initiate gliomagenesis in newborn mice and in adult rats (see Table 1) (1, 10, 63). In astrocytomas that do not express high levels of PDGF-A and -B, expression of PDGF-C and -D may be increased and is thought to substitute for the protumorigenic role of PDGF-B (25). Loss of p53 is also a common genetic event in astrocytoma tumors (WHO Grade II) (2–4).

In the more malignant form of astrocytoma, anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO Grade III), loss of the gene that encodes the cell-cycle progression regulator Rb, which occurs as a consequence of the deletion of chromosome 13q13, is detected in approximately 30% of tumors (Table 1) (1–4, 31). Downregulation or mutation of the tumor-suppressor gene p16INK4A/CDKN2A occurs in approximately 50% of these tumors. The downregulation can occur as a result of either hypermethylation of the promoter region or loss of the chromosome 9p region (1). The p16INK4A and ARF genes are encoded by a single genetic locus known as INK4a/ARF, which is located at chromosome 9p21 (1) and encodes the precursor of p16INK4A and ARF (1). Approximately 50% of anaplastic astrocytoma tumors have a mutation of the p53 gene (1–4). In addition, the gene encoding the endogenous p53 inhibitor, MDM2 (on chromosome 12q), is amplified in 13% to 43% of these tumors (37–40). As a consequence of the alterations in the Rb1/CDK4/p16INK4A and p53/p14ARF genes, signals that negatively regulate the cell cycle are interrupted, resulting in deregulated cell proliferation (3, 31). Loss of chromosome 22q and gain of chromosome 7q are also found in approximately 20% of anaplastic astrocytoma tumor samples, but the identity of the gene(s) or loci that contribute to anaplastic astrocytoma tumorigenesis or progression is not yet known (42, 43).

GBM tumors (WHO Grade IV) can be subdivided into primary and secondary tumors on the basis of the patient’s age at presentation and the genetic alterations in the tumor. Primary GBM tumors present de novo in older patients (typically >60 years of age) without a preexisting lower-grade glioma, and they account for approximately 90% of all GBM tumors. Secondary GBM tumors arise from a pre-existing Grade II or III astrocytoma or from a mixed glioma (oligoastrocytoma) (1–4). In primary GBM tumors, amplification and/or mutation of the gene encoding epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), found on chromosome 7, occurs in up to 60% of tumors (3, 31). The most common mutation is a gain-of-function mutation due to an in-frame deletion of exons 2–7; this mutation results in the constitutive activation of EGFR, which can promote glioma cell proliferation and invasion (3, 31, 32, 46, 47). Deletion of the lipid phosphatase gene, PTEN, due to LOH of chromosome 10q or mutation, is also a common genetic occurrence in the primary GBM tumors; this deletion results in increased AKT/mTOR activity, which promotes cell survival, proliferation, and invasion (1–4). Both amplification of the EGFR gene and LOH of the PTEN gene can be readily detected by FISH or Southern blotting in the pathology laboratory. Several other potential tumor-suppressor gene candidates on chromosome 10q, such as DMBT1 (deleted in malignant brain tumors 1) (54) and the Myc antagonist Mxi1 (17, 55), have been proposed. Also, the MDM2 gene (an inhibitor of p53 on chromosome 12q) is amplified in approximately 10% to 15% of GBM tumor samples (38). Hypermethylation of the promoter of the gene encoding the DNA-repair enzyme, MGMT, occurs in both primary GBM (36%) and secondary GBM (75%) tumors and indicates a better response to temozolomide therapy (32, 60, 61).

Heterogeneity in glioma tumors is also found within individual tumors. For example, certain areas of a glioma tumor may experience hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia results in the activation of proangiogenic genes and a focally increased angiogenic response (64). Also, breakdown of the blood-brain barrier can occur focally within a glioma tumor, resulting in leakage of serum-derived extracellular matrix proteins into certain areas of the tumor. Focal expression of serum-derived extracellular matrix proteins can alter integrin signaling and the motility of the glioma cells.

Molecular Mechanisms Contributing to the Proliferative and Invasive Phenotype

Like other malignant tumors, glioma tumors proliferate rapidly. This highly proliferative phenotype is due to the loss of multiple cell-cycle inhibitors as well as to increased signaling from multiple growth factor receptors that act through downstream effectors to exert positive effects on the regulation of the cell cycle. The growth factors receptors that initiate a proproliferative signal in these tumors include EGFR and PDGFR (1–4). Frequently, expression of both the ligand and the receptor is increased in glioma tumors, suggesting that there exists an autocrine or paracrine loop that amplifies signaling (65, 66).

Importantly, the EGFR and the PDGFR growth factor receptors cooperate or coordinate with cell-adhesion receptors, such as integrins and ephrins, resulting in an amplification of the growth factor receptor signal (67–71). Growth factor receptors and cell-adhesion receptors typically rapidly activate focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a cytoplasmic nonreceptor tyrosine kinase. FAK is a major positive regulator of cell-cycle progression (72, 73) and acts by increasing extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) activity and cyclin D1 transcription, as well as by inhibiting expression of p27Kip1 (74–77).

Gliomas are invasive tumors (78). For the malignant gliomas, the invasive phenotype is a highly characteristic feature; others have referred to this phenotype as a signature feature (78–80). As with the proliferative phenotype, growth factor receptor signaling plays a major role in promoting the invasive phenotype in cooperation with, or in coordination with, cell-adhesion receptors and proteases (67–71, 81). Multiple growth factor receptors have been shown to promote glioma cell migration and invasion, including c-Met (82), EGFR (83, 84), and PDGFR (67, 85). Typically, there is increased expression of both the growth factor receptor and ligand in the tumor, again suggesting that an autocrine or paracrine loop that promotes signaling is in place (1–4).

Members of several different families of cell-adhesion receptors, including members of the integrin family (86, 87), the Eph/Ephrin family (88–90), and the CD44 family (91–93), have been shown to promote glioma cell migration and invasion. In some instances, expression of cell-adhesion receptors, such as integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 (87, 94–96), is increased in malignant glioma tumors. The integrin receptors provide the interaction with the cytoskeleton of the cell that generates the traction that enables the cell to pull itself forward. Regarding the Eph/Ephrin family, current data indicate that the Ephrin-B3 ligand and the Eph-B3 receptor promote glioma cell invasion (88–90). Cell-surface receptors from different classes or families probably cooperate or coordinate signaling events in a context-dependent manner that is also regulated temporally.

Signaling molecules in the glioma cells act downstream of the cell-surface growth factor receptor and cell-adhesion receptor to amplify and propagate the proinvasion signal. These signaling molecules include cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases, adaptor molecules, and cytoskeletal proteins (97). For example, both the tyrosine kinase FAK (72, 86, 98, 99) and another member of this family, Pyk2 (100, 101), can promote glioma cell migration and invasion in a context-dependent manner. The Src family tyrosine kinases also are necessary for glioma cell invasion (67, 73, 102). Adaptor molecules from the Crk-associated substrate (CAS) family, such as HEF1 and p130CAS, promote glioma invasion (86), and members of the Crk family of adaptor molecules act downstream of HEF1 or CAS proteins in this process (103, 104). Two signaling molecules that regulate glioma cell survival and proliferation, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and PTEN, also regulate glioma cell migration and invasion (103, 105). PI3K positively regulates glioma cell migration and invasion (105). PTEN appears to negatively regulate these processes; thus, the loss of PTEN function in malignant gliomas can promote glioma cell invasion (103).

Glioma cell invasion most likely requires protease degradation of the extracellular matrix. Several families of proteases, including the serine proteases, cathepsins, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and the ADAMTS family of metalloproteases (81, 88, 106), have been shown to play a role in glioma cell migration and invasion. Protease activity can be regulated by multiple factors in a tumor. One important aspect of this regulation is the localization of protease function in specific regions of the tumor cell membrane. An example of this process is the localization of the serine protease, urokinase. Urokinase expression is increased in GBM tumors in vivo (96, 107–109), and downregulation either of urokinase or of its receptor (the urokinase receptor) inhibits glioma cell invasion (110, 111). The binding of urokinase to its receptor localizes this protease to specific areas of the cell membrane and promotes its activity in these areas because the binding of urokinase to its receptor is necessary for optimal protease activity. Also, the receptor colocalizes with specific integrin receptors on the cell membrane, further specifying the membrane region that exhibits protease activity (81, 112). A second example is the binding of MMP-2 to integrin alpha v beta 3 on the cell surface, which both localizes and enhances the activity of this protease (113). Thus, proteases act in concert with cell-surface receptors and downstream signaling molecules to promote glioma cell invasion (114).

Animal Models of Malignant Astrocytoma and Oligodendroglioma

Animal models of astrocytoma tumors have been created. Central nervous system–specific inactivation of the genes encoding the tumor suppressors p53 and Nf1 leads to the spontaneous onset of Grade II and III astrocytoma tumors, as well as to GBM tumors in mice (115). This gliomagenesis can be accelerated by haploinsufficiency of the PTEN gene (116), and in neural progenitor cells conditional inactivation of p53 coordinates with a haploinsufficiency of PTEN and Nf1 to induce astrocytoma tumor formation (117). These models support the concept that the genetic alterations in human tumors, such as p53 loss and loss of PTEN function, are probably important in the development of astrocytomas (Grades II and III).

Rodent models of GBM tumors are also available. In a somatic gene-transfer model, simultaneous retroviral expression of constitutively active Ras and Akt gives rise to the formation of high-grade gliomas that are morphologically similar to human GBM tumors (118). Although Ras mutations are uncommon in GBM tumors, one study (119) suggests that Ras activity is increased in human GBM biopsies due to a point mutation. In mice, the combination of EGFR amplification and either loss of p53 plus CDK4 overexpression or loss of INK4a-ARF is sufficient to induce glioma tumor formation that resembles that of human GBM tumors (120, 121). In an EGFR transgenic mouse model, LOH of p16INK4a, p19ARF, and PTEN cooperates with the amplification of EGFR to induce a highly infiltrative GBM tumor (121). Also, simultaneous deletion of p53 and PTEN in the mouse central nervous system generates an acute-onset, high-grade malignant glioma tumor that is histologically similar to human GBM tumors (122). A new model of GBM tumor has been created by retroviral expression of PDGF-B in adult rat neural progenitor cells (85). In this model, intracranial injection of retrovirus containing PDGF-B alone or in combination with PDGFRα results in the development of GBM-like tumors (63, 85). To date, individual disruption or LOH of a single gene regulating the cell cycle, such as p53, INK4a, or ARF, has been insufficient to initiate gliomagenesis in vivo (123). Taken together, these studies suggest that alterations in neural progenitor cells probably give rise to at least some high-grade gliomas.

There are limitations in the use of the above-discussed models. These include the facts that the tumor cells are not of humor origin and that the rodents can in some instances require several months to reliably develop glioma tumors.

Xenograft models of malignant astrocytoma have been extensively used to assess the function of various signaling molecules or matrix proteins in glioma growth and invasion (74, 124). Xenograft models that transplant human malignant astrocytoma/glioma cells into the brains of immunocompromised mice (athymic nude or SCID) have the advantage of being relatively rapid models with which to assess the role of a particular molecule in positively or negatively regulating proliferation and/or regulating invasion in vivo. One disadvantage of human xenograft models is that most human glioma cell lines are not invasive when propagated in vivo (125–128). Another disadvantage is that the propagation of human malignant astrocytoma/glioma cell lines in culture can result in their loss of key genetic alterations, such as expression of the mutant EGFR (129, 130), that are the most likely to be important in gliomagenesis. This limitation has been overcome by propagating primary human GBM tumors in the nude mouse (either subcutaneously or intracerebrally) instead of in culture; when these tumors are propagated in vivo, the genetic alterations found in the patients biopsy are retained (131). For xenograft models it is also important to propagate the tumors for experimental analysis in an orthotopic environment (the brain) because the microenvironment in the brain (i.e., the extracellular matrix, growth factors, and stromal cells) is different from that found in the subcutaneous tissue.

Several animal models of oligodendroglioma tumors have been established. One model uses the somatic gene-transfer technology in which retrovirally expressed PDGF-B is injected intracranially into newborn mice, resulting in PDGF-B expression in neural progenitor cells and the induction of oligodendroglioma tumors (63). Xenografts of neural progenitor cells or of astrocytes expressing ectopic PDGF-B can also induce oligodendroglioma tumors in mice after 12 weeks (10). These models support the concept that upregulation of PDGFR signaling through upregulation of the PDGF-B ligand is sufficient to induce gliomagenesis (10, 14).

Contribution of Cancer Stem Cells

Tumor cells expressing markers of neural progenitor cells, which are able to self-renew and to differentiate, have been termed cancer stem cells (79). Typically, these cells account for less than 5% of the tumor cells within one tumor, although the number varies significantly among different studies (79, 132–135). A key feature of these cells is their ability, when injected, to more rapidly form a tumor in immunocompromised mice, as compared to injection of the non–cancer stem cell tumor population (79, 132, 135). Another key feature of these cells is their ability to form a highly invasive xenograft tumor in immunocompromised mice (79, 132, 135). These cells are thought to reside in the perivascular area of the tumor, referred to as the vascular niche (133). The molecules typically used to identify these cancer stem cells include CD133 (79, 132, 135). Cancer stem cells in gliomas probably contribute to tumorigenesis, development into the highly invasive phenotype, and radiation resistance (134).

CONCLUSIONS

Characterization of the genetic and epigenetic alterations in gliomas has led to protein structure-function studies that have elucidated both how the signaling pathways are altered and their effect on cell proliferation, survival, and invasion. These studies clearly indicate the complexity of the regulation of these processes and suggest a dynamic process in which the cells of the tumor respond in a context-dependent manner to their microenvironment by cooperation and cross talk among receptors and intersecting signaling pathways. They also indicate how the tumor cells can promote invasion through remodeling of their microenvironment. Importantly, knowledge of these genetic alterations has allowed scientists to create rodent models to test the importance of such alterations in vivo, to determine whether they are necessary for gliomagenesis or tumor progression (see Table 1), and to test novel therapeutic approaches that target the pathways associated with the alterations.

Increasing knowledge of the genetic and epigenetic alterations in the different types and stages of gliomas has already had an impact on diagnosis. As profiles generated for glioma tumors create subcategories of each tumor type and grade, therapy will likely become more individualized and lead toward a personalized medicine approach for treating glioma tumors. Currently, for Grade IV tumors (GBMs) the standard therapeutic approach is surgical tumor debulking, followed by radiation and chemotherapy (15). Several different approaches that target various aspects of the tumorigenesis cascade are in various stages of development, and some have been entered into clinical trials (see Table 2). Animal models have shown, however, that malignant glioma tumors develop resistance to new therapies; thus, the field must continue to advance so that new therapeutic approaches and strategies that match the pace of development of tumor resistance can be developed.

Table 2.

Clinical trials with different inhibitors targeting molecules that facilitate glioma invasion

| Mechanism(s) | Targeted molecule or pathway | Drug (company)/compound | Phase/condition | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell adhesion, proliferation, and migration | Integrin α5β1 | ATN-161 (Attenuon)/antagonist | Phase II: malignant glioma | 136 |

| Integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5 | Cilengitide (EMD Pharmaceuticals)/antagonist | Phase I: pediatric brain tumors Phase II: gliomas |

136 | |

| ECM | Tenascin | 131I-81C6 (NCI)/mAb | Phase I: brain and CNS tumors | NIHa |

| Cytoplasmic kinase | Src | Dasatinib (Bristol-Myers Squibb)/inhibitor | Phase II: recurrent GBM | NIH |

| PI3K/mTOR | XL765 (Exelixis)/inhibitor | Phase I: GBM malignant gliomas, mixed gliomas | NIH | |

| Growth factors | EGFR | ZD6474 (AstraZeneca) | Phases I and II: gliomas | 136 |

| MAb-425 (Drexel University)/anti-EGFR-425 mAb | Phase II: high-grade gliomas | NIH | ||

| Erlotinib/(TARCEVA/NCI)/antagonist | Phases I and II: recurrent malignant gliomas | NIH | ||

| Gefitinib (NIH)/peptide | Phases I and II: GBM | – | ||

| PDGFR | AZD2171 (AstraZeneca)/kinase inhibitor | Phase I: CNS tumors Phase II: GBM |

136 | |

| Imatinib (Novartis)/inhibitor | Phase II: GBM | NIH | ||

| Suramin (Bayer/NCI)/inhibitor | Phase II: GBM | 136 | ||

| Vatalanib (Novartis)/kinase inhibitor | Phase II: GBM | 136 | ||

| Sorafenib (Bayer)/kinase inhibitor | Phase II: GBM | NIH | ||

| c-Met | MGCD265 (MethylGene)/kinase inhibitor | Phase I: GBM | 137 | |

| XL184 (Exelixis)/kinase inhibitor | Phase II: GBM | NIH | ||

| Cytoskeletal machinery | Microtubule | Panzem (EntreMed)/colchicine site-binding microtubule depolymerizing agent | Phase II: recurrent GBM | NIH; 136, 138 |

| Matrix proteinase | MMP | Prinomastat (Agouron)/inhibitor | Phase II: GBM | 136 |

The information in this table was extracted from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) website (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov) through a search for “glioma, brain cancer, glioblastoma and angiogenesis.” Clinical trials that are open, closed, enrolling, or completed are included in this table. Irrelevant drug listings were excluded. Many drugs have been utilized in multiple concurrent clinical trials. The primary investigator and clinical trial information can be found on this website.

Abbreviations: ECM, extracellular matrix; GBM, glioblastoma; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; PDGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Contributor Information

Candece L. Gladson, Email: gladsoc@ccf.org.

Richard A. Prayson, Email: prayso@ccf.org.

Wei (Michael) Liu, Email: liuw@ccf.org.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Louis DN. Molecular pathology of malignant gliomas. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2006;1:97–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason WP, Cairncross JG. The expanding impact of molecular biology on the diagnosis and treatment of gliomas. Neurology. 2008;71:365–73. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319721.98502.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao RD, Uhm JH, Krishnan S, James CD. Genetic and signaling pathway alterations in glioblastoma: relevance to novel targeted therapies. Front Biosci. 2003;8:e270–80. doi: 10.2741/897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sathornsumetee S, Rich JN. Designer therapies for glioblastoma multiforme. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1142:108–32. doi: 10.1196/annals.1444.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:492–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savitz DA, Checkoway H, Loomis DP. Magnetic field exposure and neurodegenerative disease mortality among electric utility workers. Epidemiology. 1998;9:398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell DA, Xie W, Schmittling R, Learn C, Friedman A, et al. Sensitive detection of human cytomegalovirus in tumors and peripheral blood of patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2008;10:10–18. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollack IF. Brain tumors in children. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1500–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412013312207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Population-based studies on incidence, survival rates, and genetic alterations in astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:479–89. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai C, Celestino JC, Okada Y, Louis DN, Fuller GN, Holland EC. PDGF autocrine stimulation dedifferentiates cultured astrocytes and induces oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas from neural progenitors and astrocytes in vivo. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1913–25. doi: 10.1101/gad.903001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleihues P, Louis DN, Scheithouer BW, Rorck LLB, Reifenberg G, et al. The WHO classification of tumors in the nervous system. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;60:215–25. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleihues P, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Histological Typing of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. New York: Springer; 1993. p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleihues P, Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. The new WHO classification of brain tumours. Brain Pathol. 1993;3:255–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1993.tb00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih AH, Holland EC. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and glial tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2006;232:139–47. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stupp R, Mason WP, Van Den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nutt CL. Molecular genetics of oligodendrogliomas: a model for improved clinical management in the field of neurooncology. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E2. doi: 10.3171/foc.2005.19.5.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maher EA, Furnari FB, Bachoo RM, Rowitch DH, Louis DN, et al. Malignant glioma: genetics and biology of a grave matter. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1311–33. doi: 10.1101/gad.891601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiencke JK, Zheng S, Jelluma N, Tihan T, Vandenberg S, et al. Methylation of the PTEN promoter defines low-grade gliomas and secondary glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology. 2007;9:271–79. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shoshan Y, Nishiyama A, Chang A, Mork S, Barnett GH, et al. Expression of oligodendrocyte progenitor cell antigens by gliomas: implications for the histogenesis of brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10361–66. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith JS, Wang XY, Qian J, Hosek SM, Scheithauer BW, et al. Amplification of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-A (PDGFRA) gene occurs in oligodendrogliomas with grade IV anaplastic features. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59(6):495–503. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.6.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohapatra G, Betensky RA, Miller ER, Carey B, Gaumont LD, et al. Glioma test array for use with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue: Array comparative genomic hybridization correlates with loss of heterozygosity and fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Mol Diagn. 2006;8:268–76. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2006.050109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith JS, Alderete B, Minn Y, Borell TJ, Perry A, et al. Localization of common deletion regions on 1p and 19q in human gliomas and their association with histological subtype. Oncogene. 1999;18:4144–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bigner SH, Matthews MR, Rasheed BKA, Wiltshire RN, Friedman HS, et al. Molecular genetic aspects of oligodendrogliomas including analysis by comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:375–86. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65134-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasaki H, Zlatescu MC, Betensky RA, Ino Y, Cairncross JG, Louis DN. PTEN is a target of chromosome 10q loss in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas and PTEN alterations are associated with poor prognosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:359–67. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61702-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lokker NA, Sullivan CM, Hollenbach SJ, Israel MA, Giese NA. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGR) autocrine signaling regulates survival and mitogenic pathways in glioblastoma cells: evidence that the novel PDGF-C and PDGF-D ligands may play a role in the development of brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3729–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puputti M, Tynninen O, Sihto H, Blom T, Maenpaa H, et al. Amplification of KIT, PDGFRA, VEGFR2, and EGFR in gliomas. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:927–34. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleming TP, Saxena A, Clark WC, Robertson JT, Oldfield EH, et al. Amplification and/or over-expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptors and epidermal growth factor receptor in human glial tumors. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4550–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campomenosi P, Ottaggio L, Moro F, Urbini S, Bogliolo M, et al. Study on aneuploidy and p53 mutations in astrocytonias. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1996;88:95–102. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thangnipon W, Mizoguchi M, Kukita Y, Inazuka M, Iwaki T, et al. Distinct pattern of PCR-SSCP analysis of p53 mutations in human astrocytomas. Cancer Lett. 1999;141:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henson JW, Schnitker BL, Correa KM, von Deimling A, Fassbender F, et al. The retinoblastoma gene is involved in malignant progression of astrocytomas. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:714–21. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soni D, King JA, Kaye AH, Hovens CM. Genetics of glioblastoma multiforme: mitogenic signaling and cell cycle pathways converge. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Genetic pathways to primary and secondary glioblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1445–53. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuzuki T, Tsunoda S, Sakaki T, Konishi N, Hiasa Y, Nakamura M. Alterations of retinoblastoma, p53, p16(CDKN2), and p15 genes in human astrocytomas. Cancer. 1996;78:287–93. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960715)78:2<287::AID-CNCR15>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Deimling A, Bender B, Jahnke R, Waha A, Kraus J, et al. Loci associated with malignant progression in astrocytomas: a candidate on chromosome 19q. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1397–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dehais C, Laigle-Donadey F, Marie Y, Kujas M, Lejeune J, et al. Prognostic stratification of patients with anaplastic gliomas according to genetic profile. Cancer. 2006;107:1891–97. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brat DJ, Seiferheld WF, Perry A, Hammond EH, Murray KJ, et al. Analysis of 1p, 19q, 9p, and 10q as prognostic markers for high-grade astrocytomas using fluorescence in situ hybridization on tissue microarrays from radiation therapy oncology group trials. Neuro-Oncology. 2004;6:96–103. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reifenberger G, Liu L, Ichimura K, Schmidt EE, Collins VP. Amplification and overexpression of the MDM2 gene in a subset of human malignant gliomas without p53 mutations. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2736–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hulleman E, Helin K. Molecular mechanisms in gliomagenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 2005;94:1–27. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(05)94001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rainov NG, Dobberstein KU, Bahn H, Holzhausen HJ, Lautenschlager C, et al. Prognostic factors in malignant glioma: influence of the overexpression of oncogene and tumor-suppressor gene products on survival. J Neurooncol. 1997;35:13–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1005841520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korkolopoulou P, Christodoulou P, Kouzelis K, Hadjiyannakis M, Priftis A, et al. MDM2 and p53 expression in gliomas: a multivariate survival analysis including proliferation markers and epidermal growth factor receptor. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:1269–78. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fischer U, Meltzer P, Meese E. Twelve amplified and expressed genes localized in a single domain in glioma. Hum Genet. 1996;98:625–28. doi: 10.1007/s004390050271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ino Y, Silver JS, Blazejewski L, Nishikawa R, Matsutani M, et al. Common regions of deletion on chromosome 22q12.3-q13.1 and 22q13.2 in human astrocytomas appear related to malignancy grade. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:881–85. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199908000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schrock E, Blume C, Meffert MC, du Manoir S, Bersch W, et al. Recurrent gain of chromosome arm 7q in low-grade astrocytic tumors studied by comparative genomic hybridization. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1996;15:199–205. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199604)15:4<199::AID-GCC1>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joensuu H, Puputti M, Sihto H, Tynninen O, Nupponen NN. Amplification of genes encoding KIT, PDGFRα and VEGFR2 receptor tyrosine kinases is frequent in glioblastoma multiforme. J Pathol. 2005;207:224–31. doi: 10.1002/path.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shinojima N, Tada K, Shiraishi S, Kamiryo T, Kochi M, et al. Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6962–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujisawa H, Reis RM, Nakamura M, Colella S, Yonekawa Y, et al. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 10 is more extensive in primary (de novo) than in secondary glioblastomas. Lab Investig. 2000;80:65–72. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ohgaki H, Dessen P, Jourde B, Horstmann S, Nishikawa T, et al. Genetic pathways to glioblastoma: a population-based study. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6892–99. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hui AB-Y, Lo KW, Yin XL, Poon WS, Ng HK. Detection of multiple gene amplifications in glioblastoma multiforme using array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Lab Investig. 2001;81:717–23. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kraus JA, Glesmann N, Beck M, Krex D, Klockgether T, et al. Molecular analysis of the PTEN, TP53 and CDKN2A tumor suppressor genes in long-term survivors of glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2000;48:89–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1006402614838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt EE, Ichimura K, Goike HM, Moshref A, Liu L, Collins VP. Mutational profile of the PTEN gene in primary human astrocytic tumors and cultivated xenografts. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:1170–83. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199911000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang SI, Puc J, Li J, Bruce JN, Cairns P, et al. Somatic mutations of PTEN in glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4183–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liang ML, Ma J, Ho M, Solomon L, Bouffet E, et al. Tyrosine kinase expression in pediatric high grade astrocytoma. J Neurooncol. 2008;87:247–53. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9513-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shiraishi S, Tada K, Nakamura H, Makino K, Kochi M, et al. Influence of p53 mutations on prognosis of patients with glioblastoma. Cancer. 2002;95:249–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mollenhauer J, Wiemann S, Scheurlen W, Korn B, Hayashi Y, et al. DMBT1, a new member of the SRCR superfamily, on chromosome 10q25.3–26.1 is deleted in malignant brain tumours. Nat Genet. 1997;17:32–39. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wechsler DS, Shelly CA, Petroff CA, Dang CV. MXI1, a putative tumor suppressor gene, suppresses growth of human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4905–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biernat W, Tohma Y, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. Alterations of cell cycle regulatory genes in primary (de novo) and secondary glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;94:303–9. doi: 10.1007/s004010050711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He J, Reifenberger G, Liu L, Collins VP, James CD. Analysis of glioma cell lines for amplification and overexpression of MDM2. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;11:91–96. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870110205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holtkamp N, Ziegenhagen N, Malzer E, Hartmann C, Giese A, von Deimling A. Characterization of the amplicon on chromosomal segment 4q12 in glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-Oncology. 2007;9:291–97. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watts GS, Pieper RO, Costello JF, Peng YM, Dalton WS, Futscher BW. Methylation of discrete regions of the O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) CpG island is associated with heterochromatinization of the MGMT transcription start site and silencing of the gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5612–19. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mrugala MM, Chamberlain MC. Mechanisms of disease: temozolomide and glioblastoma—look to the future. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:476–86. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qian XC, Brent TP. Methylation hot spots in the 5′ flanking region denote silencing of the O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3672–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uhrbom L, Hesselager G, Nister M, Westermark B. Induction of brain tumors in mice using a recombinant platelet-derived growth factor B–chain retrovirus. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5275–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaur B, Khwaja FW, Severson EA, Matheny SL, Brat DJ, Van Meir EG. Hypoxia and the hypoxia-inducible-factor pathway in glioma growth and angiogenesis. Neuro-Oncology. 2005;7:134–53. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704001115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uhrbom L, Nerio E, Holland EC. Dissecting tumor maintenance requirements using bioluminescence imaging of cell proliferation in a mouse glioma model. Nat Med. 2004;10:1257–60. doi: 10.1038/nm1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arwert E, Hingtgen S, Figueiredo JL, Bergquist H, Mahmood U, et al. Visualizing the dynamics of EGFR activity and antiglioma therapies in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7335–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ding Q, Stewart JE, Jr, Olman MA, Klobe MR, Gladson CL. The pattern of enhancement of Src kinase activity on platelet-derived growth factor stimulation of glioblastoma cells is affected by the integrin engaged. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39882–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304685200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berrier AL, Yamada KM. Cell-matrix adhesion. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:565–73. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Borges E, Jan Y, Ruoslahti E. Platelet derived growth factor receptor β and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 bind to the β3 integrin through its extracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39867–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alam N, Goel HL, Zarif MJ, Butterfield JE, Perkins HM, et al. The integrin-growth factor receptor duet. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:649–53. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee TH, Seng S, Li H, Kennel SJ, Avraham HK, Avraham S. Integrin regulation by vascular endothelial growth factor in human brain microvascular endothelial cells: role of α6β1 integrin in angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40450–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cox BD, Natarajan M, Stettner MR, Gladson CL. New concepts regarding focal adhesion kinase promotion of cell migration and proliferation. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:35–52. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stettner MR, Wang W, Nabors LB, Bharara S, Flynn DC, et al. Lyn kinase activity is the predominant cellular SRC kinase activity in glioblastoma tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5535–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ding Q, Grammer JR, Nelson MA, Guan JL, Stewart JE, Jr, Gladson CL. p27Kip1 and cyclin D1 are necessary for focal adhesion kinase regulation of cell cycle progression in glioblastoma cells propagated in vitro and in vivo in the scid mouse brain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6802–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao J, Zheng C, Guan J. Pyk2 and FAK differentially regulate progression of the cell cycle. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3063–72. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao J, Pestell R, Guan JL. Transcriptional activation of cyclin D1 promoter by FAK contributes to cell cycle progression. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:4066–77. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.12.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhao J, Bian ZC, Yee K, Chen BP, Chien S, Guan JL. Identification of transcription factor KLF8 as a downstream target of focal adhesion kinase in its regulation of cyclin D1 and cell cycle progression. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1503–15. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rao JS. Molecular mechanisms of glioma invasiveness: the role of proteases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5821–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Demuth T, Berens ME. Molecular mechanisms of glioma cell migration and invasion. J Neurooncol. 2004;70:217–28. doi: 10.1007/s11060-004-2751-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lakka S, Rao J. Role and regulation of proteases in human gliomas. In: Lendeckel U, Hooper N, editors. Proteases in the Brain. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 151–77. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lamszus K, Schmidt NO, Jin L, Laterra J, Zagzag D, et al. Scatter factor promotes motility of human glioma and neuromicrovascular endothelial cells. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:19–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980105)75:1<19::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim HD, Guo TW, Wu AP, Wells A, Gertler FB, Lauffenburger DA. Epidermal growth factor-induced enhancement of glioblastoma cell migration in 3D arises from an intrinsic increase in speed but an extrinsic matrix- and proteolysis-dependent increase in persistence. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4249–59. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lund-Johansen M, Bjerkvig R, Humphrey PA, Bigner SH, Bigner DD, Laerum OD. Effect of epidermal growth factor on glioma cell growth, migration, and invasion in vitro. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6039–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Assanah M, Lochhead R, Ogden A, Bruce J, Goldman J, Canoll P. Glial progenitors in adult white matter are driven to form malignant gliomas by platelet-derived growth factor–expressing retroviruses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6781–90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0514-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Natarajan M, Stewart JE, Golemis EA, Pugacheva EN, Alexandropoulos K, et al. HEF1 is a necessary and specific downstream effector of FAK that promotes the migration of glioblastoma cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:1721–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ding Q, Stewart J, Jr, Prince CW, Chang PL, Trikha M, et al. Promotion of malignant astrocytoma cell migration by osteopontin expressed in the normal brain: differences in integrin signaling during cell adhesion to osteopontin versus vitronectin. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5336–43. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2002.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nakada M, Miyamori H, Kita D, Takahashi T, Yamashita J, et al. Human glioblastomas overexpress ADAMTS-5 that degrades brevican. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:239–46. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nakada M, Drake KL, Nakada S, Niska JA, Berens ME. Ephrin-B3 ligand promotes glioma invasion through activation of Rac1. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8492–500. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nakada M, Niska JA, Miyamori H, McDonough WS, Wu J, et al. The phosphorylation of EphB2 receptor regulates migration and invasion of human glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3179–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Radotra B, McCormick D. Glioma invasion in vitro is mediated by CD44-hyaluronan interactions. J Pathol. 1997;181:434–38. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199704)181:4<434::AID-PATH797>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Koochekpour S, Pilkington GJ, Merzak A. Hyaluronic acid/CD44H interaction induces cell detachment and stimulates migration and invasion of human glioma cells in vitro. Int J Cancer. 1995;63:450–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910630325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Merzak A, Koocheckpour S, Pilkington GJ. CD44 mediates human glioma cell adhesion and invasion in vitro. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3988–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Paulus W, Baur I, Schuppan D, Roggendorf W. Characterization of integrin receptors in normal and neoplastic human brain. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:154–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gladson CL, Cheresh DA. Glioblastoma expression of vitronectin and the αvβ3 integrin: adhesion mechanism for transformed glial cells. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:1924–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI115516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gladson CL, Pijuan-Thompson V, Olman MA, Gillespie GY, Yacoub IZ. Up-regulation of urokinase and urokinase receptor genes in malignant astrocytoma. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1150–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Furnari FB, Fenton T, Bachoo RM, Mukasa A, Stommel JM, et al. Malignant astrocytic glioma: genetics, biology, and paths to treatment. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2683–710. doi: 10.1101/gad.1596707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Natarajan M, Hecker TP, Gladson CL. FAK signaling in anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma tumors. Cancer J. 2003;9:126–33. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang D, Grammer JR, Cobbs CS, Stewart JE, Jr, Liu Z, et al. p125 focal adhesion kinase promotes malignant astrocytoma cell proliferation in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:4221–30. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.23.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lipinski CA, Tran NL, Bay C, Kloss J, McDonough WS, et al. Differential role of proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 and focal adhesion kinase in determining glioblastoma migration and proliferation. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:323–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lipinski CA, Tran NL, Menashi E, Rohl C, Kloss J, et al. The tyrosine kinase pyk2 promotes migration and invasion of glioma cells. Neoplasia. 2005;7:435–45. doi: 10.1593/neo.04712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kleber S, Sancho-Martinez I, Wiestler B, Beisel A, Gieffers C, et al. Yes and PI3K bind CD95 to signal invasion of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:235–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tamura M, Gu J, Takino T, Yamada KM. Tumor suppressor PTEN inhibition of cell invasion, migration, and growth: differential involvement of focal adhesion kinase and p130Cas. Cancer Res. 1999;59:442–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gu J, Tamura M, Pankov R, Danen EH, Takino T, et al. Shc and FAK differentially regulate cell motility and directionality modulated by PTEN. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:389–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ling J, Liu Z, Wang D, Gladson CL. Malignant astrocytoma cell attachment and migration to various matrix proteins is differentially sensitive to phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase inhibitors. J Cell Biochem. 1999;73:533–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Viapiano MS, Hockfield S, Matthews RT. BEHAB/brevican requires ADAMTS-mediated proteolytic cleavage to promote glioma invasion. J Neurooncol. 2008;88:261–72. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9575-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gondi CS, Lakka SS, Dinh DH, Olivero WC, Gujrati M, Rao JS. Intraperitoneal injection of a hairpin RNA–expressing plasmid targeting urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) receptor and uPA retards angiogenesis and inhibits intracranial tumor growth in nude mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4051–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yamamoto M, Sawaya R, Mohanam S, Bindal AK, Bruner JM, et al. Expression and localization of urokinase-type plasminogen activator in human astrocytomas in vivo. Cancer. 1994;54:3656–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yamamoto M, Sawaya R, Mohanam S, Rao VH, Bruner JM, et al. Expression and localization of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor in human gliomas. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5016–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gondi CS, Lakka SS, Dinh DH, Olivero WC, Gujrati M, Rao JS. RNAi-mediated inhibition of cathepsin B and uPAR leads to decreased cell invasion, angiogenesis and tumor growth in gliomas. Oncogene. 2004;23:8486–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lakka SS, Gondi CS, Dinh DH, Olivero WC, Gujrati M, et al. Specific interference of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor and matrix metalloproteinase–9 gene expression induced by double-stranded RNA results in decreased invasion, tumor growth, and angiogenesis in gliomas. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21882–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408520200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Adachi Y, Lakka SS, Chandrasekar N, Yanamandra N, Gondi CS, et al. Down-regulation of integrin alpha vbeta 3 expression and integrin-mediated signaling in glioma cells by adenovirus-mediated transfer of antisense urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) and sense p16 genes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47171–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brooks PC, Strombland S, Sanders LC, von Schalscha TL, Aimes RT, et al. Localization of matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2 to the surface of invasive cells by interaction with integrin αvβ3. Cell. 1996;85:683–93. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Belkin AM, Akimov SS, Zaritskaya LS, Ratnikov BI, Deryugina EI, Strongin AY. Matrix-dependent proteolysis of surface transglutaminase by membrane-type metalloproteinase regulates cancer cell adhesion and locomotion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18415–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhu Y, Guignard F, Zhao D, Liu L, Burns DK, et al. Early inactivation of p53 tumor suppressor gene cooperating with NF1 loss induces malignant astrocytoma. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kwon CH, Zhao D, Chen J, Alcantara S, Li Y, et al. Pten haploinsufficiency accelerates formation of high-grade astrocytomas. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3286–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Alcantara Llaguno S, Chen J, Kwon CH, Jackson EL, Li Y, et al. Malignant astrocytomas originate from neural stem/progenitor cells in a somatic tumor suppressor mouse model. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Holland EC, Celestino J, Dai C, Schaefer L, Sawaya RE, Fuller GN. Combined activation of Ras and Akt in neural progenitors induces glioblastoma formation in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25:55–57. doi: 10.1038/75596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sharma MK, Zehnbauer BA, Watson MA, Gutmann DH. RAS pathway activation and an oncogenic RAS mutation in sporadic pilocytic astrocytoma. Neurology. 2005;65:1335–36. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180409.78098.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Holland EC, Hively WP, DePinho RA, Varmus HE. A constitutively active epidermal growth factor receptor cooperates with disruption of G1 cell-cycle arrest pathways to induce glioma-like lesions in mice. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3675–85. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhu H, Acquaviva J, Ramachandran P, Boskovitz A, Woolfenden S, et al. Oncogenic EGFR signaling cooperates with loss of tumor suppressor gene functions in gliomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2712–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813314106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zheng H, Ying H, Yan H, Kimmelman AC, Hiller DJ, et al. p53 and Pten control neural and glioma stem/progenitor cell renewal and differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1129–33. doi: 10.1038/nature07443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Holland EC. Animal models of cell cycle dysregulation and the pathogenesis of gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2001;51:265–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1010609114564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Golembieski WA, Ge S, Nelson K, Mikkelsen T, Rempel SA. Increased SPARC expression promotes U87 glioblastoma invasion in vitro. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1999;17:463–72. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Finkelstein SD, Black P, Nowak TP, Hand CM, Christensen S, Finch PW. Histological characteristics and expression of acidic and basic fibroblast growth factor genes in intracerebral xenogeneic transplants of human glioma cells. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:136–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pilkington GJ, Bjerkvig R, De Ridder L, Kaaijk P. In vitro and in vivo models for the study of brain tumor invasion. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:4107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Saris SC, Bigner SH, Bigner DD. Intracerebral transplantation of a human glioma line in immunosuppressed rats. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:582–88. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.3.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tonn JC. Model systems in neurooncology. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2002;83:79–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6743-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pandita A, Aldape KD, Zadeh G, Guha A, James CD. Contrasting in vivo and in vitro fates of glioblastoma cell subpopulations with amplified EGFR. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;39:29–36. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bigner SH, Humphrey PA, Wong AJ, Vogelstein B, Mark J, et al. Characterization of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human glioma cell lines and xenografts. Cancer Res. 1990;50:8017–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Giannini C, Sarkaria JN, Saito A, Uhm JH, Galanis E, et al. Patient tumor EGFR and PDGFRA gene amplifications retained in an invasive intracranial xenograft model of glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-Oncology. 2005;7:164–76. doi: 10.1215/S1152851704000821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Dirks PB. Cancer: stem cells and brain tumours. Nature. 2006;444:687–88. doi: 10.1038/444687a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, Hogg TL, Fuller C, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444:756–60. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Marumoto T, Tashiro A, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Scadeng M, Soda Y, et al. Development of a novel mouse glioma model using lentiviral vectors. Nat Med. 2009;15:110–16. doi: 10.1038/nm.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Folkman J. Angiogenesis: an organizing principle for drug discovery? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:273–86. doi: 10.1038/nrd2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Migliore C, Giordano S. Molecular cancer therapy: can our expectation be MET? Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:641–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Risinger AL, Giles FJ, Mooberry SL. Microtubule dynamics as a target in oncology. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:255–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]