Abstract

We have investigated the usage of gold-plated bare fiber probes for in situ imaging of retinal layers and surrounding ocular tissues using time-domain common-path optical coherence tomography. The fabricated intra-vitreous gold-plated micro-fiber probe can be fully integrated with surgical tools working in close proximity to the tissue to provide subsurface images having a self-contained reference plane independent to the Fresnel reflection between the distal end of the probe and the following medium for achieving reference in typical common-path optical coherence tomography. We have fully characterized the probe in an aqueous medium equivalent to the vitreous humor in the eye and were able to differentiate various functional retinal tissue layers whose thickness is larger than the system’s resolution.

1 Introduction

In recent advanced ophthalmic microsurgery and post-surgery diagnosis, optical coherence tomography (OCT) has been introduced for a noninvasive and real-time imager and sensor with ultrahigh subsurface resolution [1–4]. Accordingly, there have been many successful developments so far to obtain high-resolution intraocular images using non-intruding probes and/or scanning tools for two-dimensional or three-dimensional optical cross-sectional imaging [5–9]. Especially, OCT-based imaging and guided surgeries gain their merit in that conventional microsurgery has been performed or guided by a surgical microscope or angioscope which could limit the surgeon’s view or make the surgeon tired during the operation [10, 11]. Therefore, clinically, there is a need for minimally invasive OCT probes that can be encapsulated into a surgical catheter and be directly inserted into the ocular tissues for image acquisition and surgical navigation [12–16]. In addition, the imaging/sensing probe should not experience performance degradation for various in situ or in vivo OCT-guided eye operations. In the case of the eye, for instance, which is filled with vitreous humor (index ~1.336), the imaging probe should perform equally well both inside and outside the eye.

Common-path optical coherence tomography (CPOCT) has gained much interest in recent years due to its robust and stable configuration resulting from the fact that sample and reference arms share the same fiber optic path [17–21]. Thus, CPOCT systems are inherently simpler and more robust which results in easier to obtain high-resolution sub-surface images with resolution of a several micrometers depending on the source characteristics [22, 23]. For a typical CPOCT system, the sample object probe tip not only functions as a transceiver or a pin-hole but provides the reference plane which is the main difference compared to conventional Michelson interferometer OCT. In other words, for the common-path configuration, the reference signal is obtained not by the additional or external reference arm but by the probe tip itself, which is relying on an approximately 3.59% reflectivity between the single-mode optical fiber probe (index ~1.467) and the air (index ~1.00). Thus, if the probe is submerged in the aqueous medium (index ~1.333), the magnitude of the reflectivity decreases to 0.24% due to the reduced index differences at the interface of fiber tip to the water resulting in a smaller reference level which is one of the factors that determine the reconstructed object signal intensity from the interferometer receiver. Instead, by thin-film coating the probe tip end using chemically stable and biomedically safe or proved metals for the reference reflection, we could achieve an appropriate magnitude of reference signals that do not depend on the reflectivity in the interface media for CPOCT systems unless the light beam is totally absorbed or reflected by that thin metal film or plate.

In order to meet and/or satisfy all the objectives mentioned above, we have fabricated gold-coated micro-fiber probes (Au-μFP) and demonstrated their imaging capability using a frog (Rana catesbeiana, or North American Bullfrog) eye as an imaging sample. We believe the Au-μFPs can be fully integrated with micro-retinal surgical [24–27] instruments working in close proximity to the tissue, which will provide a tool for measuring tissue distances, and for obtaining OCT images of the internal retinal tissue planes. Au-μFP allows for a strong reference reflection from the probe tip not depending on the reflectivity due to the refractive index differences in between the media even when the probe is submerged in the liquid or in contact with the tissue. No focusing lens was implemented with Au-μFP in order to limit the probe size to the current fiber diameter of 125 μm rather than concentrating on building a sufficiently narrow scanning probe for B-mode lateral scanning using a fine focusing lens so that we could maintain the simple scanning by using stepper motors for a transversely moving stage for evaluating the miniature probe.

2 Experimental setup

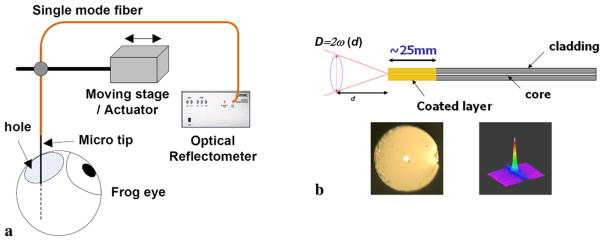

The all-fiber CPOCT system uses a single-probe arm working as both sample and reference arm and providing the reference plane at the distal end of the probe [18]. The reference and signal travel through the same arm and route to a fiber optic auto correlator. The auto correlation is achieved by a pair of piezo-electrically controlled fiber stretchers changing the delay time. The correlated beams were detected by a PIN photodetector for reconstructing the scanned depth profile or A-mode scan. In order to obtain the B-mode imaging (transverse scan), a high-resolution stepper motor (Newport 850G) was utilized for precise scanning steps. The experimental setup to scan the frog eye is illustrated in Fig. 1(a) where Au-μFP was fixed vertically by a holder for in situ specimen scanning and the computer controls the CPOCT system and the stepper motor. A small hole was punctured in the side of a frog eye to insert the Au-μFP and the tip of Au-μFP was placed in front of the frog retina. We replaced the lost vitreous humor with 0.9% NaCl saline solution to maintain the shape of the eye and retina during the measurement.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of in situ frog retina imaging using common-path optical coherence tomography with gold-coated micro-fiber optic probe:

(a) experimental setup;

(b) gold-coated fiber probe (d: distance from the fiber probe to the sample, D: beam diameter determined by beam waist ω(d) at distance d). Microscope images of gold-coated probe (bottom left) and beam profile (bottom right)

Au-μFPs were fabricated from standard single-mode optical fiber (Corning SMF-28). The fiber was cleaved using an ultrasonic cleaver (FK11) and a thin-film gold-palladium (Au-Pd) alloy was deposited on the end-face using a standard sputtering technique (Denton Vacuum DESK II). An Au-μFP is schematically shown in Fig. 1(b). The total length of the gold-coated fiber region was approximately 25 mm and the deposition time was between 5–25 s which determines the total thickness of the coated layer. The palladium (Pd) alloy helps the gold layer deposit evenly in a few nanometer thin uniform coated layer without beading as could otherwise result from the surface tension of the pure gold. The digital microscope image is shown in the bottom left of Fig. 1(b) where a white light lamp source was coupled to highlight the fiber core area and the magnification was × 1000 for the top view image.

The axial (or depth) CPOCT resolution depends on the light source bandwidth that determines the coherence length (lc) of the source. We used a commercial super luminescent diode (SLD) as a broadband light source. The measured spectrum at 2 mW output power has a center wavelength of 1330 nm (λ0) and a bandwidth of 51 nm (Δλ). Hence, these source parameters provide an axial resolution of 15 μm in the air (n0 = 1) expressed by

| (1) |

Thus, the CPOCT axial resolution in the water could be estimated of around 11 μm by simply dividing the resolution in the air by the refractive index of water, which is 1.333. Using the 1.3 μm wavelength source allows higher power operation and greater penetration depth due to the reduced scattering; however, it provides a lower resolution compared to the 0.8 μm systems commonly used for micro structure imaging in ophthalmology [28, 29].

The illuminating beam size, which relates directly to the lateral resolution, is independent on the axial resolution and only depends on the optical characteristics of the fiber probe. The transverse resolution in our case was limited because we did not use a focusing element. In the case without focusing, the Rayleigh distance (d0) is approximately 70 μm from the Au-μFP tip, which is defined as the distance (d) at which the beam radius ,

| (2) |

where ω0 is the initial mode field radius at the fiber end facet (~4.7 μm), n is the refractive index of the medium (~1.333), and λ0 is the operating wavelength (~1.33 μm). Accordingly, the lateral beam size (D, or beam diameter, 2ω) can be determined by the beam waist of the initial mode field at the facet of the fiber (ω0) using an equation given by

| (3) |

As a result, we kept the distance between the probe and the sample near or within the Rayleigh range to have an almost evenly distributed beam as well as to have more forward direction power which reduces as 1/d2 where both effects could significantly reduce the OCT SNR as a function of depth in the image object resulting in a loss of image contrast immediately outside the Rayleigh range.

On the other hand, the two-dimensional far-field beam profile was measured by an infrared (IR) CCD camera (Ophir BeamStar FX) as shown on the bottom right of Fig. 1(b). The background line was verified to be due to the noise of the detector operating at the end of the wavelength range of the detector. Therefore, the profile slightly differs from the perfect Gaussian profile because of this equipment limitation. The far-field beam profile is he same as that for the normal standard single-mode fiber profile without any coating. We have measured the correlation between the beam profile and the perfect Gaussian shape to be better than 0.9, while the ellipticity, which is the ratio between the smaller and larger beam widths, is greater than 0.95.

3 Results and discussions

The reflectivity of Au-μFP was characterized by measuring the reference signal from the probe tip when the probe was submerged in an aqueous medium (distilled water) to mimic the in situ condition (the refractive index of vitreous humor is ~1.336). It is desirable to achieve a stronger reference signal in order to obtain a higher image signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) below detector saturation region given as [18]

| (4) |

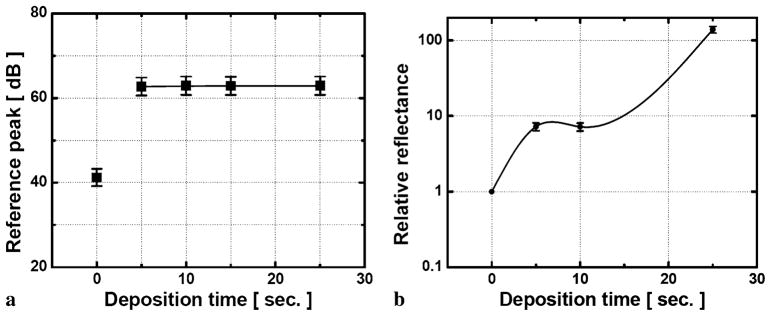

where ρ is the detector responsivity, Pr is the reflected reference power, is the returned sample power, and represents the total noise of the system. The Au-μFP was connected to the CPOCT and the reference signal was obtained from the partial reflection at the probe end without any specimen. The reflectivity of the gold-coated probe depends on the coating thickness and the relationship between the corresponding deposition times. The reference reflectivity is measured in Fig. 2(a) where the reference magnitude increases from 41 to 62 dB as the deposition time increases from 5 to 25 s in free space and remains at a steadily higher constant at 62 dB in the water condition. (62 dB is the maximum SNR for our common-path OCT system.) Here, 0 s deposition corresponds to a bare fiber probe without any coating having reference magnitude of 62 dB in free space, whereas it is reduced to 42 dB in aqueous condition. These phenomena, that metal coatings have smaller reflections, are due to the relationship between the thickness of the thin gold film and the skin depth of ~5 nm at this wavelength range. If the coated layer is not thick enough compared to the skin penetration, the metallic layer does not effectively act as a mirror to reflect the light in lower deposition time but it has some sort of transparency or opacity rather than the silvered case, except that it is relatively greater than the skin depth (e.g., 25 s deposition) [30]. However, in the aqueous condition, the liquid-state water effectively thickens the total layer so that the coated layer becomes silvered. Thus, we could also further optimize the reflectance and the transmittance in the near infrared range by controlling the thickness and the density of the gold film surface resulting in a half-silvered mirror [31]. We should mention that, for all these cases, there were no observable spectral shape changes both in the reflected and transmitted beam that could affect the reference signal or image results during the measurement.

Fig. 2.

Optical performance of the probe in the aqueous environment: (a) effect of deposition time on reference peak level; (b) relative reflectance vs. deposition time in water

We further measured the reflectance in the aqueous environment in Fig. 2(b) as a function of deposition time. When the gold-coated fiber is submerged into the water, the reflectance (normalized to the reflectance for normal bare fiber in the water) having the silvered effect by the water is much greater than the case of the normal fiber with no coating in which reflectance reduces due to the decreased refractive index difference in the fiber (1.467)-water (1.333) interface from the fiber (1.467)-air (1.000) one. As expected, the reflectance without any coating (0 s) becomes ~1/15 compared to the value in the air from 3.59% to 0.24%. However, with more than 15 s of deposition, the layer thickness became too thick and the metal layer acted as a highly reflective mirror. The resulting reflectance was too large and did not permit any light transmission. Here, the ideal deposition time was found to be around 15 s, which provided an ideal thickness of the coated layer, which resulted in approximately 1.7% reflection in the water which is more than 7 times greater than that without the coating.

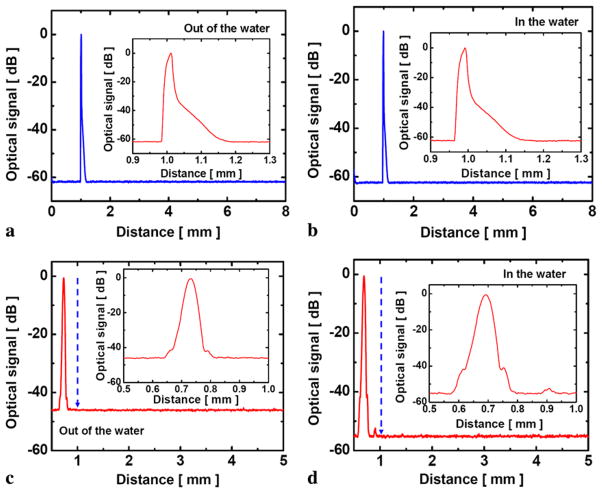

Figures 3(a) and (b) show in detail the asymmetrical peak of 62 dB with 8 mm full scanning range obtained by our CPOCT system where the optical signal range was normalized to the peak power and the same results were obtained in both cases when the probe was in and out of the water. We can also observe an exponential decay of the absorbed light with increasing metallic thickness or correspondingly the deposition time from the reconstructed reference signal in the inset figures. Consequently, we used a probe with a thinner gold coating plate for the experiment. This was accomplished simply by reducing the deposition time to less than 15 s from the initial time of more than 20 s. The amount of reflection or reference signal when Au-μFP was submerged in the water was higher than that from the bare fiber-air interface reference signal. A-mode scans of Au-μFP (10s deposition) in the water and air is shown in Figs. 3(c) and (d), respectively. The insets show the detailed shape of the reflected reference signal by the coated layer.

Fig. 3.

A-mode (depth) scan images of reference signal: (a) thick (25 s deposition) coated probe in air; (b) thick (25 s deposition) coated probe in water; (c) thin (10 s deposition) coated probe in air; (d) thin (10 s deposition) coated probe in water

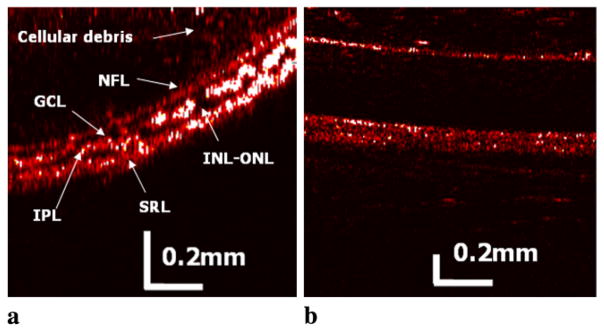

To obtain the cross-sectional image of frog retinal and other ocular tissue images, the step size for the B-scan (transverse) was set to 5 μm using a stepper motor, while the A-scan (depth) resolution was determined by the axial resolution as previously mentioned. This represents over-sampling, since the beam is not focused and the size of the beam at the surface of the tissue is in the order of 20–30 μm. The depth A-scan direction is from the top and the transverse B-scan direction to the right. In Fig. 4, the false color tomogram images of the retina (a) and the surrounding tissue such as the sclera (b) were obtained. Here, the lateral resolution is limited due to the lack of a focusing lens. In the same manner, some portion of the scattered signal from the imaged object will not be effectively coupled into the fiber probe and also the signal will experience some amount of reflections which will have direct deteriorative effect on the OCT SNR and contrast due to the diverging beam without lens based on the point-spread function of the OCT image quality. In addition, because the tissue scattering coefficient decreases with wavelength, the already low reflectivity of the nuclear layers in the retina will be further decreased at 1.3 μm as compared to the shorter near infrared light as 0.8 μm. However, it has recently been reported that even with diverging beam, the transverse (or lateral) resolution can be compensated to be narrow enough for a microscopic imaging rather than simply diverging within the tissues [32]. Thus, even though we have these limitations described, we could distinguish multiple dark and bright layers in the retina, which depends on the existence of nuclei corresponding to darker layers. Fundamentally, OCT finds the retinal layers which have contrasting structure and reflectivity in which enhanced scattering appears to correlate with horizontally oriented layers such as the nerve fiber layer and the plexiform layers forming bright layers, whereas lower reflectivity correlates with nuclei and vertical structures resulting in dark layers as labeled in Fig. 4(a). The first bright and dark layers are the optic nerve fibers (ONF) and the ganglion cell layers (GCL), respectively. The next brighter layer is the inner plexiform layer (IPL) followed by the inner nuclear and outer nuclear layers (INL-ONL) with very thin outer plexiform layer (OPL). We were unable to differentiate this 5 μm thick outer plexiform layer (the thinnest in retinal layers) in the frog retina sandwiched between the inner and outer nuclear layers where the depth resolution is lower than the layer’s thickness as well as other factors limiting the SNR beyond the Rayleigh distance of the beam. The remaining bright layer includes the sub-retinal segments and pigment epithelium [29, 33]. We could also observe some real floating matter or particles of cellular debris in the vitreous humor above the retina and sclera area. The above results, which contain the information of relative reflectivity and location of ocular structures by OCT, can potentially provide the state of the vitreoretinal interface and the condition of attachment to the macula as well as the intra-retinal pathology in terms of thickness and the presence of intra-retinal cysts where many of the early pathological changes are associated with the ocular diseases [34].

Fig. 4.

Scanned false color OCT images of retina and other ocular tissues obtained from frog eye: (a) retina; (b) sclera

4 Conclusions

We have successfully demonstrated in situ OCT imaging of a frog retina and its inner functional layers using CPOCT with an Au-μFP operating at the center wavelength of 1.3 μm. The miniaturized Au-μFPs by optimizing to a semitransparent gold thin-film layer with 1.7% reference reflectance were able to perform simple A-mode and B-mode scans in the water with no observable deterioration in their performance or damage to the specimen, which is a feature required for practical medical applications. Our results are promising for potential use in a variety of minimally invasive ophthalmic surgeries and retinal disease diagnostic procedures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant BRP 1R01 EB 007969-01.

Contributor Information

J.-H. Han, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 N. Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA, jhan16@jhu.edu, Fax: +1-410-5165566

I.K. Ilev, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Food and Drug Administration, 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, Silver Spring, MD 20993, USA

D.-H. Kim, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Food and Drug Administration, 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, Silver Spring, MD 20993, USA

C.G. Song, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 N. Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; School of Electronics & Information Engineering, Center for Advanced Image and Information Technology, Chonbuk National University, 664-14 1-Ga Deokjin-dong, Jeonju, Jeonbuk 561-756, South Korea

J.U. Kang, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, 3400 N. Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA

References

- 1.Ikeda F, Iida T, Kishi S. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:718. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayanagi K, Sharma S, Kaiser PK. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2009;40:195. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20090301-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong HT, Lim MC, Sakata LM, Aung HT, Amerasinghe N, Friedman DS, Aung T. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:256. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SJ, Bressler NM. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20:46. doi: 10.1097/icu.0b013e3283199162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feltgen N, Junker B, Agostini H, Hansen L. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:716. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bynoe L, Hutchins R, Lazarus H, Friedberg M. Retina. 2005;25:625. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200507000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fingler J, Readhead C, Schwartz DM, Fraser SE. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5055. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez A, Proupim N, Sanchez M. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1103. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.137471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joeres S, Llacer H, Heussen FMA, Weiss C, Kirchhof B, Joussen A. Eye. 2008;22:782. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srinivasan VJ, Adler DC, Chen Y, Gorczynska I, Huber R, Duker JS, Schuman JS, Fujimoto JG. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5103. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costello F, Hodge W, Pan Y, Eggenberger E, Coupland S, Kardon R. Mult Scler. 2008;14:893. doi: 10.1177/1352458508091367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosa CC, Rogers J, Pedro J, Rosen R, Podoleanu A. Appl Opt. 2007;46:1795. doi: 10.1364/ao.46.001795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao XC, Yamauchi A, Perry B, George JS. Appl Opt. 2005;44:2019. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.002019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han S, Sarunic MV, Wu J, Humayun M, Yang C. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13:020505. doi: 10.1117/1.2904664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma U, Kang JU. Rev Sci Instrum. 2007;78:113102. doi: 10.1063/1.2804112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yaqoob Z, Wu J, McDowell EJ, Heng X, Yang C. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11:063001. doi: 10.1117/1.2400214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vakhtin AB, Kane DJ, Wood WR, Peterson KA. Appl Opt. 2003;42:6953. doi: 10.1364/ao.42.006953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma U, Fried NM, Kang JU. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 2005;11:799. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leitgeb RA, Michaely R, Lasser T, Sekhar SC. Opt Lett. 2007;32:3453. doi: 10.1364/ol.32.003453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan KM, Mazilu M, Chow TH, Lee WM, Taguchi K, Ng BK, Sibbett W, Herrington CS, Brown CTA, Dholakia K. Opt Express. 2009;17:2375. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.002375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu X, Li X, Kim DH, Ilev I, Kang JU. Chin Opt Lett. 2008;6:899. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levitz D, Thrane L, Frosz MH, Andersen PE, Andersen CB, Valanciunaite J, Swartling J, Hansen PR. Opt Express. 2004;12:249. doi: 10.1364/opex.12.000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Han JH, Liu X, Kang JU. Appl Opt. 2008;47:4833. doi: 10.1364/ao.47.004833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leng T, Miller J, Bilbao K, Palanker D, Huie P, Blumenkranz M. Retina. 2004;24:427. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200406000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bower BA, Zhao M, Zawadzki RJ, Izatt JA. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:041214. doi: 10.1117/1.2772877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tameesh M, Lakhanpal M, Fujii G, Javaheri M, Shelley T, D’Anna S, Barnes AC, Margalit E, Farah M, De Juan E, Jr, Humayun MS. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:829. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott I. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:161. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Považay B, Hermann B, Unterhuber A, Hofer B, Scattmann H, Zeiler F, Morgan JE, Falkner-Radler C, Glittenberg C, Blinder S, Drexler W. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:041211. doi: 10.1117/1.2773728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fankhauser F, Kwasniewska S. Lasers in Ophthalmology: Basic, Diagnostic and Surgical Aspects: A Review. Kugler; Monroe: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hecht E. Optics. 3. Addison-Wesley; Reading: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang M, Zhou C, Jiang D. Infrared Phys Technol. 2008;51:572. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ralston TS, Marks DL, Carney PS, Boppart SA. Nat Phys. 2007;3:129. doi: 10.1038/nphys514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karwoski CJ, Frambach DA, Proenza LM. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:1607. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.6.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuman JS, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG. Optical Coherence Tomography of Ocular Diseases. 2. Slack; New Jersey: 2004. [Google Scholar]