Abstract

Rpn13 is a subunit of the proteasome that serves as a receptor for both ubiquitin and Uch37, one of the proteasome’s three deubiquitinating enzymes. We have determined the structure of full length human Rpn13 (hRpn13). Unexpectedly, the ubiquitin- and Uch37-binding domains of hRpn13 pack against each other when it is not incorporated into the proteasome. This intramolecular interaction reduces hRpn13’s affinity for ubiquitin. We find that hRpn13 binding to the proteasome scaffolding protein hRpn2/S1 abrogates its interdomain interactions, thus activating hRpn13 for ubiquitin binding. hRpn13’s Uch37-binding domain, a previously unknown fold, contains nine α-helices. We have mapped its Uch37-binding surface to a region rich in charged amino acids. Altogether, our results provide mechanistic insights into hRpn13’s functional activities with Uch37 and ubiquitin, and suggest that its role as a ubiquitin receptor is finely tuned for proteasome targeting.

Introduction

The 76 amino acid modifier ubiquitin is used to expand or modify the activity of hundreds of proteins in a cell. Ubiquitin is covalently attached to protein substrates through the coordinated effort of an ATP-dependent enzymatic cascade, which is often activated by specific cellular stimuli. Multiple cycles through the cascade can culminate in the attachment of a ubiquitin chain or multiple monoubiquitination events. Although the primary amine of lysine is typically used for ubiquitin conjugation, serine hydroxyl (Wang et al., 2007b), cysteine thiol (Cadwell and Coscoy, 2005; Ravid and Hochstrasser, 2007) groups and the N-terminal end of proteins (Ben-Saadon et al., 2004; Breitschopf et al., 1998) can also be modified by ubiquitin. The moieties of a chain are linked by an isopeptide bond between one ubiquitin’s C-terminal glycine and one of seven lysines or the N-terminal methione of another ubiquitin (Kirisako et al., 2006).

Ubiquitin chains can serve as signals for degradation by the proteasome and a diverse array of cellular events relies on the ubiquitin-proteasome collaboration. A recent study in yeast indicated that all linkages with the exception of Lys63-linked chains play a significant role in signaling for degradation by the proteasome (Xu et al., 2009). Yet, even chains of Lys63 linkage can bind to several proteasomal ubiquitin receptors (Sims et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2005) and support proteasomal degradation in vitro (Hofmann and Pickart, 2001; Kim et al., 2007) as well as in vivo (Saeki et al., 2009). Therefore, ubiquitin receptors associated with the proteasome appear to be highly adaptive in recognizing ubiquitin signals.

The 20S catalytic core particle of the proteasome is capped at either end by a 19S regulatory particle, which contains ubiquitin receptors and ubiquitin processing enzymes (reviewed by Finley, 2009). The proteasome’s ubiquitin receptors typically initiate its interaction with substrates. The two major ubiquitin receptors of the proteasome are S5a/Rpn10 (Deveraux et al., 1994) and Rpn13 (Husnjak et al., 2008; Schreiner et al., 2008). S5a has two ubiquitin interacting motifs (UIMs) that bind simultaneously to ubiquitin moieties within a chain to increase affinity (Zhang et al., 2009). By contrast, Rpn13 binds ubiquitin with a single, high affinity surface within its N-terminal plextrin-homology domain (Schreiner et al., 2008). Rpn13 also binds (Hamazaki et al., 2006; Qiu et al., 2006; Yao et al., 2006) and activates (Qiu et al., 2006; Yao et al., 2006) deubiquitinating enzyme Uch37, one of the proteasome’s three deubiquitinating enzymes. Uch37 is thought to have “proof reading” capabilities that enable it to free certain poorly ubiquitinated substrates from the proteasome and thereby rescue them from degradation (Lam et al., 1997).

Whereas Rpn13 binds ubiquitin and the Rpn2 scaffolding protein of the proteasome’s regulatory particle through its N-terminal Pru (pleckstrin-like receptor for ubiquitin) domain (Husnjak et al., 2008; Schreiner et al., 2008), a fragment containing its C-terminal 266 amino acids is sufficient for binding to Uch37 (Yao et al., 2006). We used nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to solve the structure of full length human Rpn13 (hRpn13) and to define its Uch37-binding surface. Unexpectedly, we find that the two structural regions of hRpn13 interact with each other to form a compact protein structure. This interaction reduces hRpn13’s affinity for ubiquitin, as demonstrated by tryptophan quenching experiments. The hRpn13 Pru domain surface that binds human Rpn2 (hRpn2) overlaps with that used to bind its C-terminal domain and we find that binding to hRpn2 (797-953) or proteasome potentiates hRpn13 for binding to ubiquitin by breaking its interdomain interactions. These findings suggest that hRpn13’s ubiquitin receptor function is linked to its assembly into the proteasome.

Results

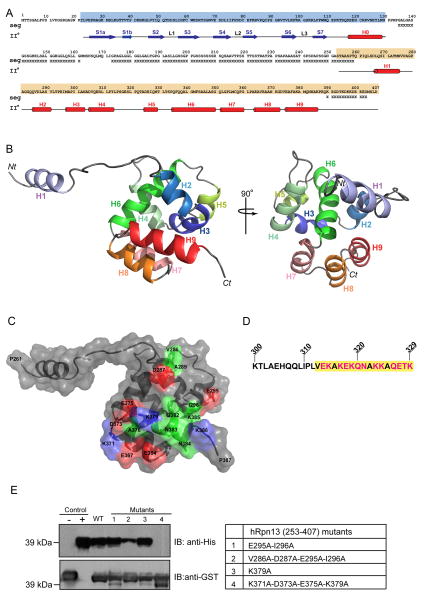

hRpn13’s C-terminal domain forms a helical bundle

hRpn13’s Pru domain is followed by 100 amino acids of low sequence complexity, rich in Gly and Ser residues (Figure 1A). We therefore hypothesized that its Uch37-binding region lies within the C-terminal segment spanning Ser253 to Asp407. By using NMR (Table 1), we found this region to contain nine α-helices, eight of which (H2-H9) form a helical bundle surrounding a compact, hydrophobic core (Figure 1B). H1 is not defined relative to H2-H9 (Figure S1A), as no NOE interactions were observed between H1 and the other secondary structural components. To determine whether this region is flexible, we acquired an 15N heteronuclear NOE enhancement (hetNOE) experiment, which measures high frequency motions. This experiment revealed that H1 and the linker region following it is flexible (Figure S1B and S1C), as expected from the NOE data. We submitted the atomic coordinates of H2-H9 to the Dali server (Holm et al., 2008) to find that although the 8-helical bundle structure has not previously been described, it has similarities with the members of the death domain superfamily, which form a 6-helical bundle (Huang et al., 1996).

Figure 1. Structure of hRpn13’s Uch37-binding domain.

(A) Primary and secondary structure of proteasome component hRpn13 highlighting its Pru domain in blue and its C-terminal structural domain in orange. Regions of low sequence complexity (as determined by the program seg (Wootton and Federhen, 1996)) are indicated with an ‘X’ and experimentally determined β-strands and α-helices with arrows and cylinders, respectively.

(B) hRpn13’s C-terminal domain forms a helical bundle. A ribbon diagram is displayed highlighting Rpn13’s nine α-helices with the orientation of structure on the left rotated by 90° relative to that on the right. This figure and that in (C) displays only one possible orientation for H1, which is not defined relative to H2-H9. Nt, N-terminus; Ct, C-terminus.

(C) Surface and ribbon view of hRpn13 displaying hydrophobic, basic and acidic residues involved in binding to Uch37 in green, blue and red, respectively, as defined by intermolecular NOE data (Figure S1D).

(D) Sequence of Uch37 spanning Lys300 – Lys329 with the hRpn13-binding surface (313-329) (Hamazaki et al., 2006) highlighted in yellow and its polar residues in red.

(E) GST pull-down assays to assess binding of His-Uch37 to GST tagged wild-type (WT) or amino acid substituted (lanes 1–4, defined in right panel) hRpn13 (253-407) loaded onto glutathione S-sepharose resin. GST-tagged hRpn13 (1-150) and direct loading of His-Uch37 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Blotting was done with anti-His (top panel) or anti-GST (bottom panel) antibody. See also Figure S1.

Table 1.

Structural statistics for NMR structure of hRpn13 (253 - 407)

| NOE distance restraints | |

|---|---|

| Total | 2503 |

| Inter-residue | 1540 |

| Sequential | 555 |

| Medium-range (|i − j| ≤ 4) | 645 |

| Long-range (|i − j| > 4) | 340 |

| Hydrogen bonds | |

| Total | 76 |

| Dihedral angle restraints (°) | |

| Total | 142 |

| ⎠ (Ni − Ciα− Ci′ − N(i+1)) | 71 |

| ⎞ (C′(i−1) − Ni − Ciα− Ci′) | 71 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most-favorable region | 72.3 |

| Additionally allowed region | 23.1 |

| Generously allowed region | 3.1 |

| Disallowed region | 1.5 |

| r.m.s.d from average structure (Å) | |

| Backbone atoms (Q285-V291, M297-Y313, A324-N329, P334-F359, A363-A385) | 0.51 ± 0.14 |

| Heavy atoms (Q285-V291, M297-Y313, A324-N329, P334-F359, A363-A385) | 1.24 ± 0.22 |

As expected, hRpn13 (253-407) binds Uch37 and intermolecular NOE interactions (Figure S1D) defined a compact binding surface composed of residues from H2, the H2-H3 loop, and H9 (Figure 1C). Charged residues are abundant at the contact surface (highlighted in red for acidic or blue for basic in Figure 1C). The complementary binding surface of Uch37, which has previously been mapped to residues Val313-Lys329 (Hamazaki et al., 2006), is similarly rich in polar residues (Figure 1D). Alanine substitutions of Val286, Asp287, Glu295, and Ile296 or of Lys371, Asp373, Glu375, and Lys379 reduces (Figure 1E, Lane 2) or abrogates (Figure 1E, lane 4) hRpn13 binding to Uch37. The effect of these mutations supports our mapping of the Uch37 contact surface, as they do not disrupt the hRpn13 protein structure, according to a 1H, 15N HSQC experiment (Figure S1E).

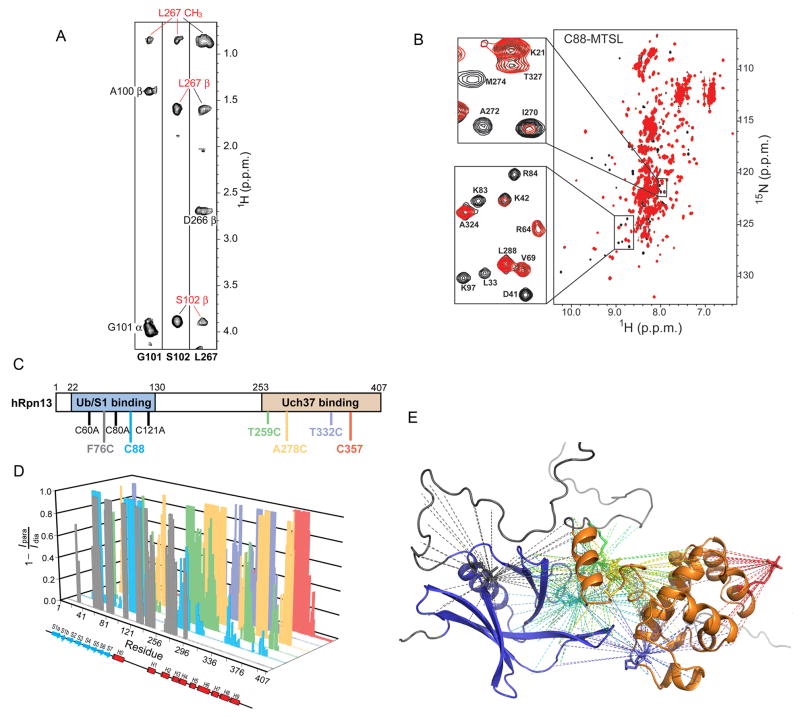

hRpn13’s two functional domains interact

Our structural analysis of hRpn13 suggested that it has two distinct domains, a ubiquitin/proteasome-binding domain, namely the Pru domain spanning residues Tyr22-Asn130 (Husnjak et al., 2008; Schreiner et al., 2008), and a Uch37-binding domain, which is encompassed in residues Ser253-Asp407 (Figure 1). We observed that titration of either domain into the other results in shifted NMR signals (Figure S2A), which is characteristic of binding. Similar spectral changes were observed when spectra of the single domain constructs were compared to those of the full length protein (Figure S2B). More direct evidence of interdomain interaction was provided by NOESY (Figure 2A) and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) interactions (Figure 2B), each of which are distance-dependent.

Figure 2. hRpn13’s Pru domain interacts with its C-terminal region spanning Ser253-Asp407.

(A) NOE interactions identified between hRpn13’s Pru domain and its C-terminal region. Each panel contains a selected region of an 15N dispersed NOESY experiment recorded on 15N, 50% 2H-labeled hRpn13 full-length protein. Interdomain NOEs are labeled in red.

(B) 1H, 15N HSQC spectrum of hRpn13 with Cys88 adducted to MTSL (red) reveals amide protons with broadened resonances due to the close proximity of the spin label. A control experiment with MTSL quenched by ascorbic acid is also displayed (black). The enlarged regions highlight inter-(top) and intra-(bottom) domain interactions.

(C), (D) Systematic MTSL spin-labeling experiments like that shown in (B) were performed with labeling at six different residue positions, as displayed in (C). In each case, only one cysteine was present and all native cysteines were substituted with alanine. In (D), paramagnetic relaxation enhancement data is summarized according to Equation (4) for each labeling scheme.

| (4) |

(E) The data in (D) is summarized onto a ribbon diagram with hRpn13’s Pru and C-terminal domains displayed in blue and orange, respectively. The PRE distance constraints are highlighted with dashed lines. The color coding in (D) and (E) follows that defined in (C).

See also Table S1 and Figure S2.

An 15N-dispersed NOESY spectrum acquired on the full length protein revealed that the structure of the Pru domain and H2-H9 mimics that of their single domain constructs (data not shown). Unambiguous interdomain NOEs appeared however between Gly101 and Ser102 of the Pru domain and Leu267 of the C-terminal domain (Figure 2A and Table S1). Additional interdomain NOEs were observed, such as between Lys103 and Leu271 (data not shown); however, these were not included in the distance constraints used to calculate the hRpn13 structure, as they overlapped with intradomain resonances. Four new unambiguous NOEs also appeared between the H1-H2 loop and helices H1 and H2 (Table S1); these are not present in the 15N-dispersed NOESY spectrum of the C-terminal fragment (data not shown).

Whereas NOEs occur between atoms that are within 6 Å, PREs are sensitive to distances ranging from 15 – 24 Å (Battiste and Wagner, 2000; Liang et al., 2006). PRE data have been used to characterize soluble (Battiste and Wagner, 2000; Donaldson et al., 2001) and membrane proteins (Liang et al., 2006; Roosild et al., 2005), and to detect transient intermediates in macromolecular complexes (Henzler-Wildman et al., 2007; Iwahara and Clore, 2006; Tang et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2007). To provide unbiased PRE constraints, we systematically labeled cysteine residues that were introduced or present in the native sequence with S-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl)methyl methanesulfonothioate (MTSL), which attaches a nitroxide spin label to the cysteine residue. In all cases, precise labeling was achieved by having only one cysteine present in the sequence (Figure 2C), as described in Experimental Procedures. This approach afforded 100 interdomain and 247 intradomain distance restraints (Figure 2D and 2E), which were combined with the NOE-derived distance restraints to solve the structure of full length hRpn13 (Table 2). Like the NOE data, the intradomain PRE constraints indicated that the structures of the Pru domain and H2-H9 were preserved compared to their single domain constructs.

Table 2.

Structural statistics for NMR structure of hRpn13

| NOE distance restraints | |

|---|---|

| Total | 4948 |

| Pru domain | 2437 |

| C-terminal region | 2507 |

| Interdomain§ | 4 |

| PRE distance restraints | |

| Total | 347 |

| Intradomain^ | 247 |

| Interdomain§ | 100 |

| Hydrogen bonds | |

| Total | 234 |

| Pru domain | 158 |

| C-terminal region | 76 |

| Dihedral angle restraints (°) | |

| Total | 351 |

| Pru domain | 209 |

| C-terminal region | 142 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most-favorable region | 62.3 |

| Additionally allowed region | 30.4 |

| Generously allowed region | 4.9 |

| Disallowed region | 2.4 |

| r.m.s.d. from average structure (Å) | |

| Backbone atoms (II° structure only) | 0.77 ± 0.16 |

| Heavy atoms (II° structure only) | 1.37 ± 0.16 |

Interdomain is defined as between the Pru domain and region spanning Ser253-Asp407

Intradomain is defined as within the Pru domain or region spanning Ser253-Asp407

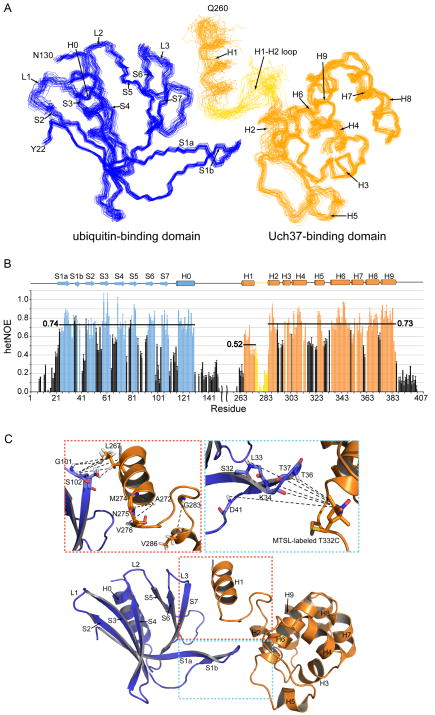

Structure of hRpn13

In full length hRpn13, the structured regions dock together at surfaces showing extensive complementarity (Figure 3A). 667 Å2 is buried from this intramolecular interaction and the Pru domain orientation relative to the C-terminal helices H1-H9 is restricted (Figure 3A). The two termini and the low complexity region that links the Pru domain to H1 showed no evidence of higher order structure in NOESY experiments (data not shown). Amide hetNOE experiments were used to test and confirm that these regions are flexible (Figure 3B and Figure S3A and S3B).

Figure 3. Structure of full-length hRpn13.

(A) NMR-derived structure of hRpn13 displaying the Pru and C-terminal domains in blue and orange, respectively. 31 structures are displayed with residues in secondary structure elements superimposed. Randomly coiled regions including the 21 N- and C-terminal residues and the linker between the Pru domain and H1 are omitted for clarity.

(B) 15N hetNOE data reveal high frequency motions for the N- and C-termini and the linker regions neighboring helix H1. Averaged values for the various structural regions are displayed for ready comparison. Error bars were determined from a repeated control spectrum, as described in Experimental Procedures.

(C) NMR data from two different sites of contact between the Pru domain and C-terminal region are highlighted. NOE interactions unique to the full length protein are noted in the expanded red box whereas the expanded blue box highlights interdomain PRE interactions observed between S1a, the S1a-S1b loop, and S1b of hRpn13’s Pru domain and MTSL-labeled Thr332Cys.

See also Figure S3.

The most dramatic change in the full length protein was observed for H1. This helix becomes ordered as it packs against the Pru domain and the H1-H2 loop (Figure 3A and 3B). Its contacts with the Pru domain are within the S6-S7 loop and S7 (Figure 3C). The hetNOE experiments support the structural data, as H1’s average value increases from 0.26 (Figure S1B) to 0.52 (Figure 3B), reflecting its more ordered state. The orientation of H1 is also defined by NOEs to the N-terminal half of the H1-H2 loop (Asn275-Ala278), which are unique to the full length protein (Table S1). The C-terminal half of this loop is less well defined (Figure 3A) due to its inherent flexibility (Figure 3B). Interdomain contacts are also apparent between the Pru domain’s S1 (S1a, the S1a-S1b loop, and S1b) and H2 and the H5-H6 loop of the C-terminal domain. This more flexible region (Figure 3B for the S1a–S1b loop) is defined by the PRE data (Figure 3C).

Interestingly, MTSL labeling of the Pru domain at amino acid position 76 caused PREs in the region spanning Met133 – Ala149 (Figure S2C). This region is flexible according to the amide hetNOE experiment (Figure 3B), exhibits no long-range NOE interactions in 15N- or 13C-dispersed NOESY experiments (data not shown), and was not resolved in the crystal structure of murine Rpn13 (1-150) (Schreiner et al., 2008). These data suggest that although Met133 – Ala149 are not rigidly defined in hRpn13, they are distributed throughout a region that is within 24 Å of the Pru domain’s ubiquitin-binding loops, which contain Phe76 (Schreiner et al., 2008).

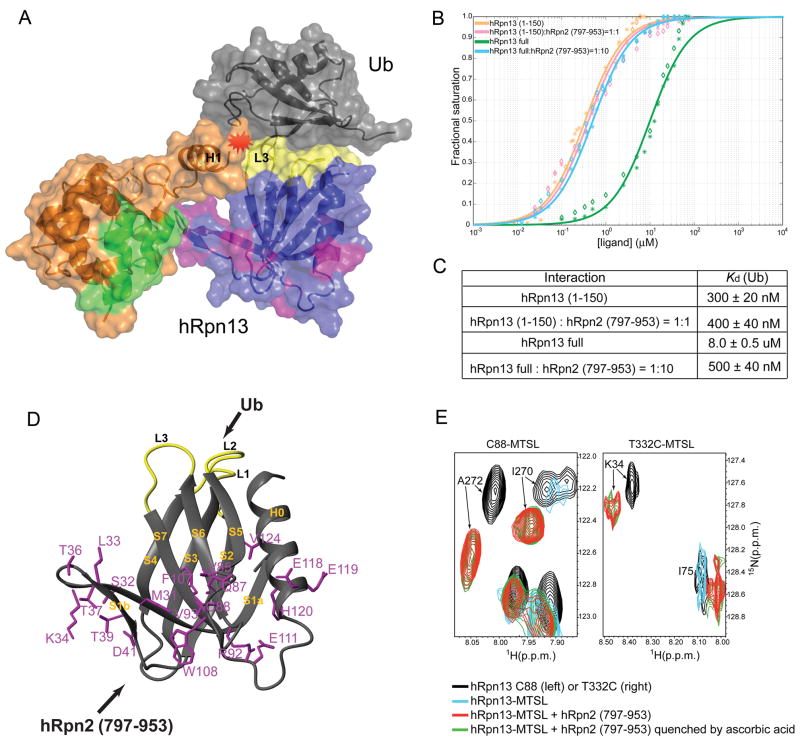

hRpn13 is activated by binding to the proteasome scaffolding protein hRpn2

Full length hRpn13 binds ubiquitin in a manner comparable to that of hRpn13 (1-150), according to NMR titration experiments (Figure S4A). Therefore, we generated an in silico hRpn13:ubiquitin model structure by superimposing hRpn13’s Pru domain onto the mRpn13 Pru:ubiquitin structure (Schreiner et al., 2008) and performed energy-minimization. This model structure revealed that the preservation of the interdomain interactions within hRpn13 would yield steric clashes between H1 and ubiquitin (Figure 4A), thus suggesting that ubiquitin binding requires loss of interdomain contacts. We therefore tested whether hRpn13’s affinity for ubiquitin is reduced in the full length protein by performing tryptophan quenching experiments in a manner identical to our previous experiments with hRpn13 (1-150) (Husnjak et al., 2008), which encompasses its Pru domain (Figure 1A). Full length hRpn13 binds ubiquitin with a Kd value of 8 ± 0.5 μM, an affinity 26-fold lower compared to the Pru domain alone (Figure 4B, C). Therefore, hRpn13’s C-terminal region reduces its affinity for ubiquitin in vitro.

Figure 4. hRpn13’s ubiquitin-binding activity is activated by proteasome scaffolding protein hRpn2.

(A) Ribbon and surface display of an hRpn13:ubiquitin model structure highlighting steric clashes (in red) that occur if the interdomain interactions are preserved. hRpn13’s Pru domain and C-terminal region are shown in blue and orange, respectively, with its ubiquitin-, hRpn2-, and Uch37-binding surfaces in yellow, purple and green, respectively. Ubiquitin is in grey. This model demonstrates why ubiquitin binding is facilitated when hRpn2 abrogates interdomain interactions.

(B), (C) Intrinsic tryptophan quenching was used to determine the affinity between hRpn13 full length protein and ubiquitin alone and with 10-fold molar excess of an hRpn2 fragment spanning 797-953. The data were compared to hRpn13 (1-150), which encompasses its Pru domain.

(D) hRpn2 (797-953) and ubiquitin bind to opposite surfaces of hRpn13’s Pru domain. The hRpn13 amino acids within the hRpn2 (797-953) binding surface, as determined by an NMR titration experiment, are highlighted in purple on a ribbon diagram of hRpn13’s Pru domain. The ubiquitin-binding loops are displayed in yellow.

(E) Superimposed 1H, 15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled hRpn13 with Cys88 (left panel) or Thr332Cys (right panel) adducted to MTSL without (blue) or with equimolar quantities of unlabelled hRpn2 (797-953) (red). Control experiments prior to MTSL treatment and hRpn2 addition (black) and in which MTSL effects are quenched with ascorbic acid after hRpn2 addition (green) are included to reveal that Lys34, Ile270 and Ala272 are affected by interdomain distance-dependent paramagnetic relaxation enhancements only in the absence of hRpn2.

See also Figure S4.

hRpn13 binds to the C-terminal end of the proteasome scaffolding protein hRpn2 (Gandhi et al., 2006; Hamazaki et al., 2006; Ito et al., 2001; Schreiner et al., 2008). We therefore tested whether hRpn2 promotes an open state of hRpn13 and hence its ubiquitin binding. Tryptophan quenching experiments revealed that hRpn2 (797-953) does not affect hRpn13 (1-150)’s affinity for ubiquitin. By contrast, the affinity of full length hRpn13 for ubiquitin is hRpn2-dependent (Figure S4B), and it exhibits an equivalent affinity compared to hRpn13 (1-150) when hRpn2 (797-953) is at 10-fold molar excess (Figure 4B, C). Therefore, hRpn2 binding appears to activate hRpn13 for ubiquitin binding.

S1 (S1a, the S1a-S1b loop, and S1b), the S5-S6 loop, S7, the S7-H0 loop and H0 of hRpn13’s Pru domain contact hRpn2 (797-953), according to an NMR titration experiment (Figure 4D and Figure S4C). These regions also interact with hRpn13’s C-terminal domain (Figure 3C), and we used PRE experiments to test and affirm that hRpn2 abrogates hRpn13’s interdomain interactions, as exemplified for Ile270, Ala272 and Lys34 (Figure 4E). In free hRpn13, Ile270 and Ala272 are attenuated when Cys88 is labeled with MTSL (Figure 4E, blue versus black), which as described above causes distance-dependent attenuation of NMR signals. Lys34 is likewise attenuated by labeling T332C with MTSL (Figure 4E, blue versus black and Figure 3C, panel boxed in blue). These interdomain PREs are lost when hRpn2 (797-953) is added, as each of these resonances is restored (Figure 4E, red). MTSL quenching with ascorbic acid does not further increase the intensity of these resonances (Figure 4E, green), indicating that the distances between these structural regions has dramatically increased upon hRpn2 binding.

We propose that free hRpn13 is in equilibrium with the state shown in Figures 3A and 3C and an open conformation in which the Pru domain does not interact with the C-terminal domain. In the absence of binding partner, the state with interdomain contacts is significantly more populated than the open conformation, as demonstrated by the observation of interdomain NOE (Figure 2A) and PRE (Figure 2B–E) interactions. Our data indicate that hRpn2 shifts this equilibrium by binding to the open conformation of hRpn13 (Figure 4E), which is more accessible to ubiquitin (Figure 4B).

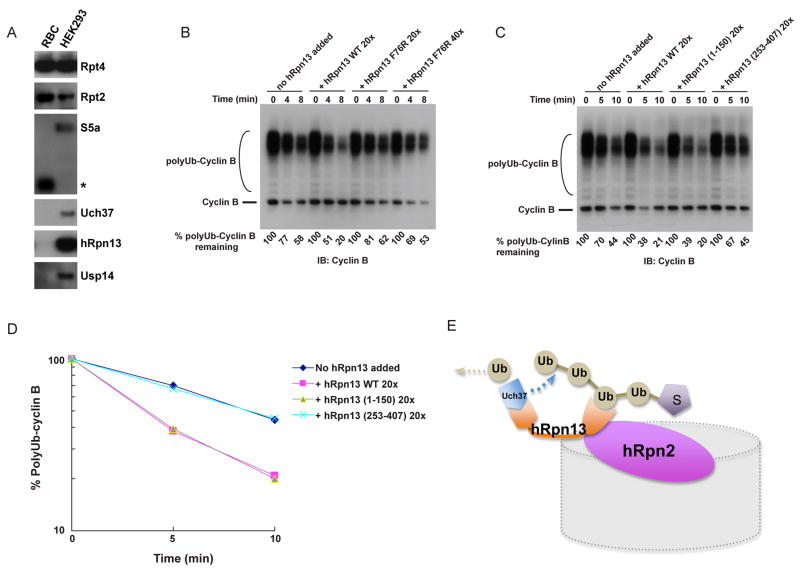

To assess hRpn13’s capacity to target ubiquitinated proteins for degradation by proteasomes, we initially tested whether it is present in proteasomes prepared from different tissues and cell lines. Purified human erythrocyte proteasomes were found to be structurally intact yet essentially devoid of both hRpn13 and full-length forms of the other known intrinsic ubiquitin receptor of the proteasome, S5a/Rpn10 (Figure 5A and Figure S5). As expected from the absence of hRpn13, Uch37 was also missing from these proteasomes. Partial deubiquitination of the test substrate, also known as chain trimming, was not observed with these proteasomes (Figure 5B), as expected based on the lack of detectable Uch37 as well as deubiquitinating enzyme Usp14 (Figure 5A). In summary, human erythrocyte-derived proteasomes provide a powerful model system for functional analysis of hRpn13 and its partner Uch37 through biochemical reconstitution. When wild-type hRpn13 was added to these proteasomes, the degradation of ubiquitinated cyclin B was strongly stimulated (Figure 5B). In contrast, the Phe76Arg mutant of hRpn13, which is specifically defective in ubiquitin recognition (Schreiner et al., 2008), did not stimulate cyclin B degradation, even when added at 40 times excess over proteasome (Figure 5B). These results provide the clearest evidence to date that Rpn13 functions as a ubiquitin receptor for the proteasome, by showing both its capacity to stimulate proteasome function in a purified in vitro system and the role of the ubiquitin-binding site in this activity of Rpn13.

Figure 5. Assembly into the proteasome potentiates hRpn13 for ubiquitin binding.

(A) Composition of human proteasomes purified from either red blood cells (RBC) or from an Rpn11-tagged line of HEK293 cells (Wang et al., 2007a). 1.5 μg of proteasomes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. The asterisk indicates a putative isoform or cleaved form of S5a. See Figure S5 for further characterization of these proteasomes.

(B) hRpn13 targets ubiquitinated cyclin B (polyUb-Cyclin B) for degradation by purified proteasomes. hRpn13 (WT or Phe76Arg variant) was added to RBC proteasomes at 20 or 40-fold molar excess, as indicated. After a 5-min preincubation, reactions were initiated by the addition of substrate. Reactions were quenched by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and subjected to SDS-PAGE/immunoblot analysis, using antibodies to cyclin B. Proteasome was present in all reactions at 4 nM.

(C), (D) Experiments were performed as described in (B) but with hRpn13 full length protein (WT), hRpn13 (1-150) or hRpn13 (253-407). The results were quantified and plotted in (D).

(E) Model of hRpn13 docked into the proteasome. Its interdomain interactions are abrogated as it binds to the proteasome’s scaffolding protein hRpn2, thus priming it for ubiquitinated substrates and Uch37. We propose that the long flexible linker region following the Pru domain may facilitate progressive cleavage of ubiquitin moieties from substrates.

See also Figure S5.

We proceeded to compare hRpn13 (1-150) and the full length protein in the degradation assay, with the C-terminal fragment hRpn13 (253-407) used as a negative control. In this experiment, full length hRpn13 demonstrated activity comparable to the Pru domain construct (Figure 5C and 5D), thus supporting our model that full length hRpn13 is activated for ubiquitin binding when docked into the proteasome (Figure 5E). We also tested whether hRpn13 binding to ubiquitinated protein enhances its binding to hRpn2 by using a GST pull-down assay, but found no such activation (Figure S4D), most likely because its affinity for hRpn2 is greater than its affinity for ubiquitin chains.

Discussion

In this study, we solve the structure of the proteasome’s ubiquitin receptor hRpn13 by NMR. We find that its two functional domains physically interact with each other when it is not docked into the proteasome and that this interaction reduces its affinity for ubiquitin. It is possible that the interdomain interactions prevent hRpn13 from inappropriately binding to ubiquitinated substrates when it is not docked into the proteasome. S. cerevisiae lacks the entire Uch37-binding domain, and correspondingly has amino acid substitutions in its Pru domain that result in a ~200-fold lower affinity for ubiquitin compared to this domain in hRpn13 (Husnjak et al., 2008).

The capacity of hRpn13 to bind ubiquitin is activated by the proteasome scaffolding protein hRpn2, which abrogates hRpn13 domain interactions. The unstructured region separating hRpn13’s two functional domains is flexible even in the absence of hRpn2, and no doubt provides a great deal of pliability in the relative orientation of hRpn13’s two functional domains when it is docked into the proteasome. A critical function of hRpn13’s C-terminal domain is to bind (Hamazaki et al., 2006; Qiu et al., 2006; Yao et al., 2006) and activate (Qiu et al., 2006; Yao et al., 2006) deubiquitinating enzyme Uch37. The crystal structure of Uch37’s catalytic domain was recently published (Nishio et al., 2009) and coordinates for the full length protein have been submitted to the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 3IHR). Full length Uch37 crystallized as a tetramer due to intermolecular interactions between α-helical extensions C-terminal to its catalytic domain. Val313-Lys329, which bind hRpn13 (Hamazaki et al., 2006), were not defined in the crystal structure, suggesting that they may be flexible, and preventing us from modeling the hRpn13:Uch37 protein complex. The docking of Uch37 to the proteasome by Rpn13’s C-terminal domain was perhaps the ancestral driving force for its existence in higher eukaryotes whereas its use to mitigate Rpn13’s ubiquitin-binding affinity when not docked into the proteasome might be a secondary adaptation.

Natural selection has been proposed to favor allosteric interactions, as the localization of functional domains within the same polypeptide increases substantially their local concentration and in turn, amplifies effects of random amino acid substitution (Kuriyan and Eisenberg, 2007). Rpn13 appears to fit this model well, as the helix at the interdomain interface (H1) is only present in higher eukaryotes (Figure S3C).

The present study has identified important regulatory interactions involving hRpn13, Uch37, hRpn2, and ubiquitin. We suspect that additional regulatory interactions among these proteins remain to be described. For example, it is not clear how hRpn13 activates Uch37, but it is possible that its strong ubiquitin-binding affinity contributes by increasing Uch37’s affinity for its substrates when in the hRpn13 complex and by helping to orient neighboring ubiquitin moieties in a configuration that is optimal for hydrolysis. In the absence of binding partner, ubiquitin moieties within Lys48-linked chains pack against each other (Cook et al., 1994; Eddins et al., 2007), with at least 85% of Lys48-linked diubiquitin in such a closed conformation at pH 6.8 (Varadan et al., 2002). hRpn13-binding causes these chains to adopt an open configuration (Schreiner et al., 2008), which may increase Uch37’s affinity for the ubiquitin linker region.

hRpn13’s ability to modulate the relative orientation of its Pru and Uch37-binding domain may contribute a driving force in Uch37 catalysis (Figure 5E). The two domains may become constrained by the simultaneous binding of Uch37 and hRpn13’s Pru domain to different ubiquitin moieties within a chain. Hydrolysis of the isopeptide bond linking the ubiquitins would enable hRpn13 to adopt a less constrained position, which may contribute to the release of the cleaved ubiquitin unit by shifting Uch37 away from the cleaved chain. Future experiments are needed to test such models and those that probe protein dynamics within the 19S regulatory particle as the proteasome processes its substrates will no doubt be invaluable to a complete understanding of proteasome function.

Experimental Procedures

Sample preparation

hRpn13, hRpn13 (253-407), and hRpn2 (797-953) or their amino acid substituted variants were expressed in Escherichia coli as fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase (GST) and thrombin (for hRpn13 (253-407)) or PreScission protease (for hRpn13 and hRpn2 (797-953)) cleavage sites. Purification was achieved by affinity chromatography on glutathione S-sepharose resin followed by size exclusion chromatography on an FPLC system. His-tagged Uch37 was purified in an identical manner, but with Ni-NTA agarose resin and elution with 250 mM imidazole. 15N ammonium chloride and/or 13C glucose was used for isotope labeling. 2H labeled glucose and D2O were used to produce 2H labeled samples. hRpn13 (1-150) was prepared as described (Schreiner et al., 2008); ubiquitin was purchased (Boston Biochem Inc.). Amino acid substitutions were introduced by using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Lys48 linked tetraubiquitin was produced as described (Pickart and Raasi, 2005).

Chemical shift assignments and structure calculation of hRpn13 (253-407)

Chemical shift assignments for hRpn13 (253-407) were obtained by using HNCA/HNCOCA and HNCO/HNCACO pairs as well as an HNCACB experiment. These were acquired on 15N, 13C, and 70% 2H labeled hRpn13 (253-407) and on Varian Inova 600 or 800 MHz spectrometers. NMR experiments acquired at 700, 800, and 900 MHz were conducted with a cryogenically cooled probe and at 25°C. hRpn13 (253-407) samples ranged from 0.6 – 0.7 mM concentration and were dissolved in Buffer 1 (20 mM NaPO4, 50 mM NaCl, 4 mM DTT at pH 6.5). All crosspeaks of the 1H, 15N HSQC spectrum were assigned and secondary structural elements assessed by using NOEs and chemical shift index values for C′ and C〈 atoms. Distance constraints for structure calculations were obtained by using a 15N-dispersed NOESY spectrum on a 15N, 50% 2H labeled sample (200 ms mixing time) and a 13C-dispersed NOESY on a 13C labeled sample dissolved in D2O (80 ms mixing times). These were acquired at 900 or 800 MHz. Backbone ⎞ and Π torsion angle constraints were derived by using TALOS (Cornilescu et al., 1999). Data processing was performed with NMRPipe (Delaglio et al., 1995) and spectra were visualized and analyzed with CARA (Diss. ETH Nr. 15947) and XEASY (Bartels et al., 1995). The NOE-derived distance constraints, hydrogen bonds and dihedral angle constraints (Table 1) were used in XPLOR-NIH version 2.24 (Schwieters et al., 2006; Schwieters et al., 2003) to determine the structure of hRpn13 (253-407). All structures from 35 starting ones had no NOE or dihedral angle violation greater than 0.3 Å or 5°, respectively.

Intermolecular and interdomain NOEs

Intermolecular NOE interactions between hRpn13 (253-407) and Uch37 were obtained by an 15N-dispersed NOESY spectrum (200 ms mixing time) acquired on 15N labeled, 100% deuterated hRpn13 (253-407) mixed with equimolar unlabeled Uch37 (Walters et al., 1997), each at 0.6 mM. NOEs between hRpn13’s Pru domain and its C-terminal region were identified in a 3D 15N-dispersed NOESY spectrum (200 ms mixing time) recorded on 15N, 50% 2H labeled hRpn13. Both spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova 900 MHz spectrometer and in Buffer 1. All experiments involving full length hRpn13 were performed at 0.1 mM to avoid aggregation.

NMR dynamic studies

Heteronuclear NOE enhancements (hetNOEs) for hRpn13 and hRpn13 (253-407) were recorded on a Varian Inova 800 MHz spectrometer. Two spectra were recorded for steady-state NOE intensities, one with 4 seconds of proton saturation to achieve the steady-state intensity and the other as a control spectrum with no saturation to obtain the Zeeman intensity. The control spectrum was repeated to determine error values. hetNOEs were calculated from the ratio described in Equation 1 (Peng and Wagner, 1994).

| (1) |

Spin labeling experiments

Only one cysteine was present in hRpn13 for the spin labeling experiments, either at position 76, 88, 259, 278, 332, 357 (Figure 2C). Expression and purification was performed as described above for the wild-type protein but with low concentrations of dithiothreitol (DTT). 1H, 15N HSQC experiments were used to confirm that there was no loss of structural integrity. Spin labeling was performed in Buffer 2 (50 mM Tris, pH 7.6) and with a 5-fold molar excess of spin labeling reagent MTSL (Toronto Research Chemicals Inc.). The reaction tubes were flushed with N2 and incubated in the dark at 4°C overnight. MTSL-labeled DTT and excess MTSL reagent were removed by extensive dialysis at 4°C in Buffer 3 (20 mM NaPO4, 50 mM NaCl, pH 6.5). DTNB (5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) assays (Riddles et al., 1979) were performed before and after spin labeling to confirm that the labeling was complete.

1H, 15N HSQC experiments were collected on a Bruker Avance 700 MHz spectrometer on samples with MTSL in the oxidized (paramagnetic) and reduced (diamagnetic) state to test for MTSL-specific effects. MTSL quenching was achieved by addition of 5-fold molar excess ascorbic acid. Spectra were acquired after incubation for 1 hour at 25°C. Identical conditions were used when equimolar hRpn2 (797-953) was added. All spectra were calibrated against the wild-type hRpn13 spectrum by using 10–12 unaffected resonances to compensate for any global effects from variations in protein concentration. PRE distances were calculated from the intensity ratio of the HSQC spectra according Equations (2) and (3) (Battiste and Wagner, 2000; Iwahara et al., 2007; Solomon and Bloembergen, 1956).

| (2) |

| (3) |

Structure calculation of hRpn13

The PRE distance constraints were defined as previously described (Battiste and Wagner, 2000; Liang et al., 2006). Protons with Ipara/Idia < 15%, including protons whose resonances were no longer detectable in the paramagnetic spectra, were assigned distance constraints ranging from 1.8 to 15 Å. Those with Ipara/Idia between 15 and 85% were assigned distance constraints of 15 to 23 Å whereas those with Ipara/Idia > 85% were not constrained. Constraints were assigned between the nitrogen atom of the MTSL ring and the amide proton attenuated.

The atomic coordinates of mRpn13 (1-150) (PDB 2R2Y) (Schreiner et al., 2008) were used to generate constraints for this domain in the structure calculations of the full length protein, as NOESY and PRE data indicated that the Pru structure is preserved in the full length protein. NOE-derived distance constraints, hydrogen bonds and dihedral angle constraints of hRpn13 (253-407) (Table 1) were also included as were the interdomain NOEs (Table S1), new intradomain NOEs (Table S1) and PRE constraints (Figure 2E). The data summarized in Table 2 was used in XPLOR-NIH version 2.24 to calculate the hRpn13 structure from 50 randomly coiled starting structures. 47 resulting structures had no NOE or dihedral angle violation greater than 0.3 Å or 5°, respectively. The 31 structures with the lowest energy were selected. All six MTSL-labeled cysteines were next replaced with the native amino acid type for hRpn13 and the structures energy-minimized by Maestro version 9.0 (Schrödinger, LLC.).

The model of hRpn13:ubiquitin was made by superimposing mRpn13 Pru:ubiquitin (PDB 2Z59) (Schreiner et al., 2008) onto the hRpn13 structure and energy-minimizing with Maestro version 9.0 (Schrödinger, LLC.).

GST pull-down analysis

0.2 nmol of purified GST-tagged hRpn13 (253-407) wild-type or mutated protein or GST-tagged hRpn13 (1-150) (as a negative control) was bound to 25 μl of pre-washed glutathione S-sepharose resin and incubated with His-tagged Uch37. Unbound protein was removed by extensive washing in Buffer 4 (20 mM NaPO4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5%(v/v) Triton X-100, pH 6.5). Proteins that were retained on the resin were fractionated by electrophoresis, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and analyzed by immunoblotting. His-tagged Uch37 was detected with mouse anti-His antibody (1:200) (Roche) followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000) (Sigma). GST-tagged hRpn13 was detected with rabbit anti-GST antibody (1:5,000) (Santa Cruz) followed by HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000) (Sigma). The same method was used for GST-tagged hRpn2 (797-953) binding to hRpn13 or hRpn13 (1-150) without or with equimolar or 5-fold molar excess Lys48-linked tetraubiquitin. hRpn13 and tetraubiquitin were detected with rabbit anti-ADRM1 antibody (1:1000) (Biomol) and mouse anti-ubiquitin antibody (1:1000) (Invitrogen), respectively.

Affinity measurements by fluorescence spectroscopy

The Kd values between ubiquitin and hRpn13 or hRpn13 (1-150) with and without hRpn2 (797-953) were determined by monitoring the change in fluorescence emission spectra between 300 and 500 nm of hRpn13 upon ubiquitin addition at 298K. Intrinsic fluorescence of two Trp residues in 1 μM hRpn13 (1-150) or hRpn13 full-length protein was measured on a JASCO FP-6200 spectrofluorometer without and with increasing molar quantities of ubiquitin (0.0083 μM – 90 μM). An excitation wavelength of 280 nm was used and spectral bandwidths for excitation and emission of 5 nm. The change in fluorescence intensity at 348 nm upon ubiquitin addition was used to generate the binding curves of Figure 4B by using Microsoft Excel. Curve fitting was achieved with Matlab v. 7.2.

In vitro protein degradation assays

Human proteasomes were prepared from an HEK293 cell line harboring HTBH-tagged Rpn11, with minor modifications in the purification (Wang et al., 2007a). Human erythrocytes-derived proteasomes were purchased from BIOMOL. Purified proteasomes (4 nM) were incubated with ~40 nM polyubiquitinated cyclin B (Ubn-ClnB) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM ATP. Where indicated, purified recombinant hRpn13 was preincubated with proteasome for 5 min prior to initiating the reaction. Reactions were terminated by adding 5x SDS-PAGE sample buffer and subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE/immunoblot analysis using anti-cyclin B1 polyclonal antibody (NeoMarkers). Ubn-ClnB was prepared as previously described (Kirkpatrick et al., 2006).

Highlights

hRpn13’s ubiquitin- and Uch37-binding domains interact

hRpn13’s Uch37-binding domain can inhibit its activity as a ubiquitin receptor

hRpn13 is activated for ubiquitin binding by docking into the proteasome

hRpn13 efficiently targets protein degradation in a purified in vitro system

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

NMR data were acquired in the NMR facility at the University of Minnesota, University of Wisconsin at Madison (NMRFAM), and University of Georgia (SECNMR). We are grateful to Klaas Hallenga (NMRFAM), Marco Tonelli (NMRFAM), and John Glushka (SECNMR) for their technical assistance. We also thank Nathaniel A. Hathaway and Randall W. King from Harvard Medical School for supplying us with cyclin B as well as Edgar Arriaga (University of Minnesota) for allowing us to use his spectrofluorometer and Yong-A Hong for help in sample preparation. Data processing and visualization occurred in the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute Basic Sciences Computing Lab. This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, CA097004 (KJW), 3R01CA097004-07S2 (KJW), and GM43601 (DF) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-07-186-01-GMC to KJW).

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The atomic coordinates of hRpn13 (253-407) and full length hRpn13 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 2kqz and 2kr0, respectively.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bartels C, Xia TH, Billeter M, Güntert P, Wüthrich K. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00417486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battiste JL, Wagner G. Utilization of site-directed spin labeling and high-resolution heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance for global fold determination of large proteins with limited nuclear overhauser effect data. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5355–5365. doi: 10.1021/bi000060h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Saadon R, Fajerman I, Ziv T, Hellman U, Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A. The tumor suppressor protein p16(INK4a) and the human papillomavirus oncoprotein-58 E7 are naturally occurring lysine-less proteins that are degraded by the ubiquitin system. Direct evidence for ubiquitination at the N-terminal residue. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41414–41421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitschopf K, Bengal E, Ziv T, Admon A, Ciechanover A. A novel site for ubiquitination: the N-terminal residue, and not internal lysines of MyoD, is essential for conjugation and degradation of the protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:5964–5973. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.20.5964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell K, Coscoy L. Ubiquitination on nonlysine residues by a viral E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2005;309:127–130. doi: 10.1126/science.1110340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WJ, Jeffrey LC, Kasperek E, Pickart CM. Structure of tetraubiquitin shows how multiubiquitin chains can be formed. J Mol Biol. 1994;236:601–609. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux Q, Ustrell V, Pickart C, Rechsteiner M. A 26 S protease subunit that binds ubiquitin conjugates. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7059–7061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson LW, Skrynnikov NR, Choy WY, Muhandiram DR, Sarkar B, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Structural characterization of proteins with an attached ATCUN motif by paramagnetic relaxation enhancement NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:9843–9847. doi: 10.1021/ja011241p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddins MJ, Varadan R, Fushman D, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Crystal structure and solution NMR studies of Lys48-linked tetraubiquitin at neutral pH. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi TK, Zhong J, Mathivanan S, Karthick L, Chandrika KN, Mohan SS, Sharma S, Pinkert S, Nagaraju S, Periaswamy B, et al. Analysis of the human protein interactome and comparison with yeast, worm and fly interaction datasets. Nat Genet. 2006;38:285–293. doi: 10.1038/ng1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki J, Iemura S, Natsume T, Yashiroda H, Tanaka K, Murata S. A novel proteasome interacting protein recruits the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH37 to 26S proteasomes. EMBO J. 2006;25:4524–4536. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henzler-Wildman KA, Thai V, Lei M, Ott M, Wolf-Watz M, Fenn T, Pozharski E, Wilson MA, Petsko GA, Karplus M, et al. Intrinsic motions along an enzymatic reaction trajectory. Nature. 2007;450:838–844. doi: 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann RM, Pickart CM. In vitro assembly and recognition of Lys-63 polyubiquitin chains. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27936–27943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Kaariainen S, Rosenstrom P, Schenkel A. Searching protein structure databases with DaliLite v.3. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2780–2781. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Eberstadt M, Olejniczak ET, Meadows RP, Fesik SW. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the Fas (APO-1/CD95) death domain. Nature. 1996;384:638–641. doi: 10.1038/384638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husnjak K, Elsasser S, Zhang N, Chen X, Randles L, Shi Y, Hofmann K, Walters KJ, Finley D, Dikic I. Proteasome subunit Rpn13 is a novel ubiquitin receptor. Nature. 2008;453:481–488. doi: 10.1038/nature06926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Chiba T, Ozawa R, Yoshida M, Hattori M, Sakaki Y. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4569–4574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahara J, Clore GM. Detecting transient intermediates in macromolecular binding by paramagnetic NMR. Nature. 2006;440:1227–1230. doi: 10.1038/nature04673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahara J, Tang C, Marius Clore G. Practical aspects of (1)H transverse paramagnetic relaxation enhancement measurements on macromolecules. J Magn Reson. 2007;184:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HT, Kim KP, Lledias F, Kisselev AF, Scaglione KM, Skowyra D, Gygi SP, Goldberg AL. Certain pairs of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) and ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) synthesize nondegradable forked ubiquitin chains containing all possible isopeptide linkages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17375–17386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609659200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T, Kamei K, Murata S, Kato M, Fukumoto H, Kanie M, Sano S, Tokunaga F, Tanaka K, Iwai K. A ubiquitin ligase complex assembles linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO J. 2006;25:4877–4887. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick DS, Hathaway NA, Hanna J, Elsasser S, Rush J, Finley D, King RW, Gygi SP. Quantitative analysis of in vitro ubiquitinated cyclin B1 reveals complex chain topology. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:700–710. doi: 10.1038/ncb1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan J, Eisenberg D. The origin of protein interactions and allostery in colocalization. Nature. 2007;450:983–990. doi: 10.1038/nature06524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YA, DeMartino GN, Pickart CM, Cohen RE. Specificity of the ubiquitin isopeptidase in the PA700 regulatory complex of 26 S proteasomes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28438–28446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B, Bushweller JH, Tamm LK. Site-directed parallel spin-labeling and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement in structure determination of membrane proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4389–4397. doi: 10.1021/ja0574825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio K, Kim SW, Kawai K, Mizushima T, Yamane T, Hamazaki J, Murata S, Tanaka K, Morimoto Y. Crystal structure of the de-ubiquitinating enzyme UCH37 (human UCH-L5) catalytic domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Wagner G. Protein Mobility from Multiple 15N Relaxation Parameters. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Probes of Molecular Dynamics. 1994:374–454. [Google Scholar]

- Pickart CM, Raasi S. Controlled synthesis of polyubiquitin chains. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:21–36. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu XB, Ouyang SY, Li CJ, Miao S, Wang L, Goldberg AL. hRpn13/ADRM1/GP110 is a novel proteasome subunit that binds the deubiquitinating enzyme, UCH37. EMBO J. 2006;25:5742–5753. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Autoregulation of an E2 enzyme by ubiquitin-chain assembly on its catalytic residue. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:422–427. doi: 10.1038/ncb1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddles PW, Blakeley RL, Zerner B. Ellman’s reagent: 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)--a reexamination. Anal Biochem. 1979;94:75–81. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90792-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosild TP, Greenwald J, Vega M, Castronovo S, Riek R, Choe S. NMR structure of Mistic, a membrane-integrating protein for membrane protein expression. Science. 2005;307:1317–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.1106392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki Y, Kudo T, Sone T, Kikuchi Y, Yokosawa H, Toh-e A, Tanaka K. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitin chain may serve as a targeting signal for the 26S proteasome. EMBO J. 2009;28:359–371. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner P, Chen X, Husnjak K, Randles L, Zhang N, Elsasser S, Finley D, Dikic I, Walters KJ, Groll M. Ubiquitin docking at the proteasome through a novel pleckstrin-homology domain interaction. Nature. 2008;453:548–552. doi: 10.1038/nature06924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Clore GM. Using Xplor-NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Progr NMR Spectroscopy. 2006;48:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J Magn Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims JJ, Haririnia A, Dickinson BC, Fushman D, Cohen RE. Avid interactions underlie the Lys63-linked polyubiquitin binding specificities observed for UBA domains. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:883–889. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon I, Bloembergen N. Nuclear magnetic interactions in the HF molecule. J Chem Phys. 1956;25:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Iwahara J, Clore GM. Visualization of transient encounter complexes in protein-protein association. Nature. 2006;444:383–386. doi: 10.1038/nature05201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C, Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Open-to-closed transition in apo maltose-binding protein observed by paramagnetic NMR. Nature. 2007;449:1078–1082. doi: 10.1038/nature06232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadan R, Walker O, Pickart C, Fushman D. Structural properties of polyubiquitin chains in solution. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:637–647. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K, Matsuo H, Wagner G. A simple method to distinguish intermonomer nuclear Overhauser effects in homodimeric proteins with C2 symmetry. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5958–5959. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Young P, Walters KJ. Structure of S5a bound to monoubiquitin provides a model for polyubiquitin recognition. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:727–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chen CF, Baker PR, Chen PL, Kaiser P, Huang L. Mass spectrometric characterization of the affinity-purified human 26S proteasome complex. Biochemistry. 2007a;46:3553–3565. doi: 10.1021/bi061994u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Herr RA, Chua WJ, Lybarger L, Wiertz EJ, Hansen TH. Ubiquitination of serine, threonine, or lysine residues on the cytoplasmic tail can induce ERAD of MHC-I by viral E3 ligase mK3. J Cell Biol. 2007b;177:613–624. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton JC, Federhen S. Analysis of compositionally biased regions in sequence databases. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:554–571. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Duong DM, Seyfried NT, Cheng D, Xie Y, Robert J, Rush J, Hochstrasser M, Finley D, Peng J. Quantitative proteomics reveals the function of unconventional ubiquitin chains in proteasomal degradation. Cell. 2009;137:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao T, Song L, Xu W, DeMartino GN, Florens L, Swanson SK, Washburn MP, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Cohen RE. Proteasome recruitment and activation of the Uch37 deubiquitinating enzyme by Adrm1. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:994–1002. doi: 10.1038/ncb1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Wang Q, Ehlinger A, Randles L, Lary JW, Kang Y, Haririnia A, Storaska AJ, Cole JL, Fushman D, Walters KJ. Structure of the S5a:K48-linked diubiquitin complex and its interactions with Rpn13. Mol Cell. 2009;35:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.