Abstract

Background

The apoptotic speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) is the essential adaptor protein for caspase 1 mediated interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 processing in inflammasomes. It bridges activated Nod like receptors (NLRs), which are a family of cytosolic pattern recognition receptors of the innate immune system, with caspase 1, resulting in caspase 1 activation and subsequent processing of caspase 1 substrates. Hence, macrophages from ASC deficient mice are impaired in their ability to produce bioactive IL-1β. Furthermore, we recently showed that ASC translocates from the nucleus to the cytosol in response to inflammatory stimulation in order to promote an inflammasome response, which triggers IL-1β processing and secretion. However, the precise regulation of inflammasomes at the level of ASC is still not completely understood. In this study we identified and characterized three novel ASC isoforms for their ability to function as an inflammasome adaptor.

Methods

To establish the ability of ASC and ASC isoforms as functional inflammasome adaptors, IL-1β processing and secretion was investigated by ELISA in inflammasome reconstitution assays, stable expression in THP-1 and J774A1 cells, and by restoring the lack of endogenous ASC in mouse RAW264.7 macrophages. In addition, the localization of ASC and ASC isoforms was determined by immunofluorescence staining.

Results

The three novel ASC isoforms, ASC-b, ASC-c and ASC-d display unique and distinct capabilities to each other and to full length ASC in respect to their function as an inflammasome adaptor, with one of the isoforms even showing an inhibitory effect. Consistently, only the activating isoforms of ASC, ASC and ASC-b, co-localized with NLRP3 and caspase 1, while the inhibitory isoform ASC-c, co-localized only with caspase 1, but not with NLRP3. ASC-d did not co-localize with NLRP3 or with caspase 1 and consistently lacked the ability to function as an inflammasome adaptor and its precise function and relation to ASC will need further investigation.

Conclusions

Alternative splicing and potentially other editing mechanisms generate ASC isoforms with distinct abilities to function as inflammasome adaptor, which is potentially utilized to regulate inflammasomes during the inflammatory host response.

Background

Inflammasomes are inducible multi-protein platforms in phagocytic cells that are required for activation of caspase 1 by induced proximity during the inflammatory host response following pathogen infection and tissue damage [1]. The best characterized substrates for caspase 1 are interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18, two potent pro-inflammatory cytokines [2]. However, a number of alternative substrates have been recently identified [3,4]. While generation of bioactive IL-1β and IL-18 is regulated at multiple steps, including transcription, posttranslational processing and receptor binding [2], their maturation into the bioactive secreted 17 and 18 kDa forms is dependent on the proteolytically active caspase 1 [5,6]. Inflammasomes are activated in response to the recognition of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) derived from pathogens (PAMPs) or host (danger or stress signals) by members of the cytosolic Nod-like receptor (NLR) family of cytosolic pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [6-10]. The largest subfamily of NLRs contains a PYRIN domain (PYD) as an effector domain [11]. Activated NLRs undergo NTP-dependent oligomerization in response to DAMP recognition, and recruit the essential adaptor protein ASC by PYD-PYD interaction [12,13]. ASC subsequently bridges to caspase 1 through caspase recruitment domain (CARD)-CARD interaction [14,15]. Macrophages with ASC gene deletion are impaired in their ability to form inflammasomes and activate caspase 1 in response to a number of DAMPs, underscoring the critical role of ASC as an adaptor protein linking activated NLRs to caspase 1 [16-18]. Recently, pyrin has also been implicated in assembling an inflammasome, and the cytosolic DNA sensor AIM2 forms a caspase 1 activating inflammasome, too [19-23].

IL-1β and IL-18 have a central role in the inflammatory host response. However, dysregulation of the inflammasome complex causes their uncontrolled and excessive secretion, and is directly linked to an increasing number of human inflammatory diseases. NLRP1 polymorphisms are linked with autoimmune diseases that cluster with vitiligo, including autoimmune thyroid disease, latent autoimmune diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, pernicious anemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Addison's disease [24]. NLRP3-containing inflammasomes are linked to contact hypersensitivity, sunburn, essential hypertension, gout and pseudogout, Alzheimer's disease, and elevated expression of NLRP3 is detected in synovial fluids of RA patients [25-30]. Furthermore, hereditary mutations in NLRP3 rendering the protein constitutively active, are directly linked to cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) [31,32]. Hereditary mutations in pyrin, the causative for Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) and in PSTPIP1, a pyrin interacting protein responsible for Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne syndrome (PAPA), are responsible for impaired regulation of IL-1β maturation [33-35]. Mutant NLRP3 proteins efficiently form complexes with ASC to mediate caspase 1 activation independent of an activating ligand. This finding demonstrates the potential benefits of controlling the recruitment of ASC to NLRs.

Several molecular mechanisms have been linked to control inflammasome activation, including single PYD or CARD-containing proteins, pyrin and some NLRs [36]. We recently demonstrated that upon infections and cell stress conditions, such as treatment of cells with bacterial RNA or heat killed gram positive and gram negative bacteria, ASC redistributes from the nucleus to the cytosol, where it aggregates with NLRs and caspase 1 into perinuclear structures [37]. Sequestering ASC inside the nucleus completely prevented caspase 1 activation and processing and release of IL-1β, suggesting that redistribution of ASC might function as a check-point to prevent spontaneous and unwanted inflammasome activation.

Here we report on the identification of three ASC isoforms with distinct abilities to function as inflammasome adaptor, suggesting that differential splicing of the ASC pre-mRNA might potentially modulate the inflammatory host responses at the level of inflammasomes.

Methods

Materials and Reagents

Monoclonal ASC-PYD-specific antibodies were from MBL (D086-3, clone 23-4, 1:1000), rabbit polyclonal ASC-PYD-specific antibodies recognizing mouse ASC were from Alexis (AL177, 1:500) and ASC-CARD-specific antibodies were from Chemicon (AB3607, 1:500), and rabbit polyclonal ASC-Linker-specific antibodies were custom raised (CS3 1:10,000) using the peptide CGSGAAPAGIRAPPQSAAKPG corresponding to amino acids 93-111 of human ASC [37].

Expression Plasmids

A search of the publicly available expressed sequence tag (EST) database revealed three potential ASC isoforms: ASC-b (Acc. No. BM456838), ASC-c (Acc. No. BE560228), and ASC-d (Acc. No. BM920038). The complete open reading frame of each isoform was subsequently amplified by PCR from pooled THP-1 cell cDNAs that were induced with a cocktail of cytokines for 2 to 24 hours. ASC-b, ASC-c, and ASC-d were amplified using the common forward primer 5'-CGGAATTCGATCCTGGAGCCATGGG-3' and the common reverse primer 5'-CGCTCGAGTGACCGGAGTGTTGCTG-3' and cloned into a modified pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) in frame with an NH2-terminal myc epitope tag. The CARD of caspase 1 was amplified by high fidelity PCR and cloned into pGex4T-1 (Novagen). All other expression constructs (ASC, pro-IL-1β, pro-caspase 1, NLRP3R260W) have been previously described [37-39].

RT-PCR

THP-1 cells were differentiated into adherent macrophages by o/n culture in complete medium supplemented with 25 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Calbiochem) and further cultured for 2 days, followed by treatment with LPS as indicated. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen), reverse transcribed into cDNA (Superscript III, Invitrogen) and analyzed for ASC mRNA expression by RT-PCR using the following primer pairs: pr-1: 5'-GCTGTCCATGGACGCCTTGG-3', 5'-CATCCGTCAGGACCTTCCCGT-3' (ASC: 299 bp, ASC-b: 242 bp); pr-2: 5'-GCCATCCTGGATGCGCTGGAG-3', 5'-GGCCGCCTGCAGCTTGAAC-3' (ASC-c: 66 bp); pr-3: 5'-CTGACCGCCGAGGAGCTCAAGAAGT-3', 5'-GGCGCCGTAGGTCTCCAGGTAGAAG-3' (ASC and ASC-b: 128 bp, ASC-d: 100 bp); β actin 5'-GGATGGCATGGGGGAGGGCATA-3', 5'-TGATATCGCCGCGCTCGTCGTC-3' (533 bp).

Cell Culture

HEK293, RAW264.7, THP-1 and J774A1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 4 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics (HEK293, RAW264.7, J774A1) or RPMI medium (ATCC) containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4500 mg/l glucose, supplemented with 1500 mg/l sodium bicarbonate, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% FBS (THP-1). Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation (Sigma) from buffy coats obtained from healthy donors and countercurrent centrifugal elutriation in the presence of 10 μg/ml polymyxin B sulfate using a JE-6B rotor (Beckman Coulter). PBMC were washed in Hank's Buffered Salt Solution, resuspended in serum-free DMEM for 1 hour and then cultured in complete medium supplemented with 20% FBS for 7 days to differentiate peripheral blood macrophages (PBM). HEK293 cells were transiently transfected using Polyfect (Qiagen) or Xfect (Clontech) according the procedures recommended by the manufacturer.

Stable Cells

RAW264.7 were stably transfected with linearized expression vectors using the Amaxa Nucleofector using program H-033, 2 × 106 cells and 1.75 μg DNA, and selected with 1 mg/ml G418 for 14 days and tested for expression by immunoblot and immunofluorescence. Stable ASC-c expressing THP-1 and J774A1 cells were generated by lentivirus transduction. ASC-c was shuttled into the pLEX expression plasmid (Open Biosystems) modified to contain Myc or GFP epitope tags. Lentivirus was produced by co-expression of pLEX with pMD2.G and psPAX2 (Addgene plasmids 12259 and 12260) in 12-well dishes and 250 μl clarified culture supernatant was used to transduce 105 THP-1 and J774A1 cells using 4 μg/ml Polybrene and the ExpressMag transduction enhancing system (Sigma) in 96-well dishes for 4 hours at 32°C, followed by Puromycin selection.

Immunofluorescence

HEK293 cells were seeded onto Type I collagen-coated (5 μg/cm2) glass cover slips in 6-well plates. The following day they were transfected with plasmids encoding each of the ASC isoforms alone or co-transfected with GFP-NLRP3R260W, GFP-pro-caspase 1C285A, or HA-tagged ASC. 36 hours post-transfection, cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde, incubated in 50 mM glycine for 5 minutes and permeabilized and blocked with 0.5% saponin, 1.5% BSA, 1.5% normal goat serum for 30 minutes. Immunostaining was performed with polyclonal anti-myc or HA antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:400) or monoclonal anti-myc antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:400; Northwestern University Monoclonal Antibody Facility, 1:10,000). Secondary Alexa Fluor 488 and 546-conjugated antibodies, Topro-3, DAPI, and phalloidin were from Molecular Probes. Cells were washed with PBS containing 0.5% saponin, and cover slips were mounted using Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech). Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy on a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta and epifluorescence microscopy on a Nikon TE2000E2 with a 100× oil immersion objective and image deconvolution (Nikon Elements). Presented are representative results observed in the majority of cells from several repeats.

Subcellular fractionation

106 cells were resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCL pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM EGTA, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors), incubated on ice, adjusted to 250 mM sucrose, and lysed using a Dounce homogenizer. Samples were initially centrifuged at 4°C at 1,000 × g for 3 minutes to remove any intact cells and then centrifuged at 4°C at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes to pellet the nuclei. The cytosolic supernatant was removed, and the nuclear pellet was then washed three times in hypotonic lysis buffer with the addition of 250 mM sucrose and 0.1% NP-40 and incubated for 20 minutes on ice. Both fractions were adjusted to 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 20 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 250 mM sucrose, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.2% NP-40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and fully solubilized by brief sonication. 50 μg of protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with anti-ASC antibodies and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia) in conjunction with an ECL detection system (Pierce). Membranes were stripped and re-probed with anti-GAPDH (Sigma) and anti-Lamin A (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies as control for cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

Measurement of IL-1β secretion

HEK293 cells were seeded into type-I collagen-coated 12-well dishes, and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were co-transfected in triplicates the following day with expression constructs encoding the constitutively active NLRP3R260W (0.675 μg), pro-caspase 1 (0.15 μg), and mouse pro-IL-1β (0.375 μg), and each of the ASC isoforms ASC-b, -c, or -d (0.04 μg) or ASC (0.015 μg), either alone or in the presence of full-length ASC to reconstitute inflammasomes. The total amount of DNA was kept constant with the addition of an empty pcDNA3 vector as necessary. The media was replaced 24 hours post-transfection, and at 48 hours post transfection, the supernatants were collected, clarified by centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C, and analyzed by ELISA for mouse IL-1β release according to the manufacturer's protocol (BD Biosciences). RAW 264.7Ctrl, RAW 264.7ASC, RAW 264.7ASC-b, J774A1Ctrl, J774A1ASC-c, THP-1Ctrl, THP-1ASC-C#1, and THP-1ASC-c#2 cells were seeded into 24-well dishes and either left untreated or treated with 300 ng/ml LPS (E. coli, 0111:B4) for 16 hours followed by the collection of culture supernatants (THP-1 cells), or followed by pulsing with ATP (5 mM for RAW264.7 and 3 mM for J774A1 cells) for 15 minutes and collection of culture supernatants. Clarified culture supernatants were analyzed for secreted mouse (RAW264.7, J774A1) or human (THP-1) IL-1β by ELISA (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

In vitro protein-interaction assay

ASC and ASC-b were in vitro translated and biotinylated using the TNT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. GST-caspase 1-CARD was affinity purified from E. coli BL21, following induction with 1 mM IPTG for 4 hours at room temperature. Cells were resuspended in STS buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, and 150 mM NaCl), lysed by several rapid freeze/thaw cycles followed by the addition of lysozyme (1 mg/ml). After a 30 minute incubation on ice, 10 mM DTT and 1.4% sodium sarkosyl were added, sonicated and cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes. Cleared lysates were adjusted to 4% Triton X-100 and incubated with immobilized glutathione sepharose (Pierce) overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS, blocked for 30 minutes at room temperature in HKMEN buffer (142.4 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% NP-40, 1 mM DTT) supplemented with protease inhibitors and BSA (1 mg/ml). Following one wash with HKMEN buffer, beads were incubated overnight on a rotator with in vitro translated ASC and ASC-b. Bound proteins were washed 4 times in HKMEN buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors, boiled in Laemmli buffer, separated by SDS/PAGE, transferred onto a PVDF membrane, and detected with Streptavidin-HRP in conjugation with an enhanced chemiluminescent reagent (Millipore).

Results

Identification of three novel ASC transcripts

We recently demonstrated that ASC localizes to the nucleus of resting macrophages and that inflammatory activation causes the inducible redistribution of ASC to the cytosol [37]. We consistently noted that a monoclonal ASC specific antibody directed to the PYD of ASC also specifically recognizes a protein with slightly lower molecular weight in the cytosol also in resting macrophages, which we named ASC-b (Figure 1A). The molecular weight appeared too large to correspond to one of the PYD-only proteins (POPs), which others and we identified as negative regulators of inflammasomes, and especially POP1 shares a high sequence similarity with ASC [36,38-42]. We used a panel of commercially available ASC specific antibodies that are directed to either the PYD or the CARD, and raised a custom polyclonal antibody to the linker domain to further characterize this protein. Using this strategy, we identified that the smaller protein is recognized by PYD and CARD specific antibodies, but that our linker specific antibody fails to detect the smaller protein in total protein lysates of THP-1 cells, suggesting that the linker that connects the PYD and the CARD in ASC is lacking in the smaller protein (Figure 1B). Furthermore, a polyclonal antibody raised against amino acid residues 2 to 27 of the PYD of ASC also detects ASC and ASC-b in lysates of PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells and an additional low abundant protein, which we named ASC-c (Figure 1C). This antibody also detects ASC in mouse J774A1 macrophages, which appear to lack ASC-b, but express significant levels of a putative ASC-c (Figure 1C). Also human peripheral blood macrophages (PBM) express ASC-b, which is upregulated following LPS treatment (Figure 1D). We did not detect ASC-c under the tested conditions, but PBM express significant lower ASC levels compared to THP-1 cells, and thus ASC-c might have gone undetected. ASC is encoded from three exons, and we therefore mined the publicly available EST database to potentially identify ASC alternative transcripts. We identified three distinct transcripts of ASC in addition to the full-length transcript expressed in human tissues. Based on these sequences, we designed specific PCR primers, and amplified all three cDNAs from a pooled human THP-1 cell cDNA library. We referred to these cDNAs as ASC-b, ASC-c, and ASC-d. ASC-b was already annotated within the NCBI GenBank and has recently been characterized as vASC by Matsushita and colleagues during the preparation of our manuscript [43]. We confirmed existence of these transcripts by RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from THP-1 cells, which we differentiated into adherent macrophage-like cells by incubation with PMA and treatment with LPS. In resting cells transcripts for ASC, ASC-b, and very low transcript numbers of ASC-d were present. LPS treatment caused the appearance of ASC-c (Figure 1E), suggesting that the presence of distinct combinations of ASC splice variants might potentially affect inflammasome activity at different stages of the inflammatory response.

Figure 1.

Identification of ASC isoforms. (A) Differentiated THP-1 macrophages were separated into nuclear and cytosolic fractions and analyzed for ASC expression using a monoclonal anti-ASC antibody recognizing the PYD of ASC by immunoblot. Blots were stripped and re-probed with antibodies for the cytosolic GAPDH and nuclear Lamin A to control for fractionation efficiency. (B) THP-1 lysates were analyzed by immunoblot for ASC expression using antibodies recognizing the PYD, the linker, and the CARD, respectively. (C) Lysates from PMA-differentiated and LPS-treated (300 ng/ml) THP-1 cells and J774A1 cells were separated by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with a PYD-specific anti-ASC antibody (AL177). (D) Lysates of human peripheral blood macrophages (PBM) that were left untreated, or treated with LPS for the indicated times, were immunoblotted for ASC. (E) PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells were treated with LPS (300 ng/ml) for the indicated times and analyzed by RT-PCR for ASC transcripts using the primer pairs pr-1 (ASC, 299 bp; ASC-b, 242 bp), pr-2 (ASC-c, 66 bp), and pr-3 (ASC and ASC-b, 128 bp; ASC-d, 100 bp). A short exposure (upper panel) and long exposure (middle panel) is shown, because of the relative low abundance of ASC-d transcripts. A β -actin primer pair (533 bp, lower panel) was used as a control.

ASC-b lacks amino acids 93 to 111, corresponding to the entire linker region, resulting in a protein with a directly fused PYD and CARD (Figure 2A, B). ASC-c lacks amino acids 26 to 85 corresponding to helices 3 to 6 of the ASC-PYD, but retains an intact ASC-Linker-CARD region (Figure 2A, B). ASC-d lacks nucleotides 107 to 134, which causes a frame shift and results in a protein consisting of helices 1 and 2 (amino acids 1-35) of the ASC-PYD fused to a novel 69 amino acid peptide without recognizable homology to any other known protein (Figure 2A, B). ASC and the three alternative cDNAs encode proteins of the predicted molecular weight, when expressed in HEK293 cells (Figure 2C). The ASC proteins that are abundantly expressed in THP-1 cells and are recognized by the ASC specific antibodies directed towards the PYD and CARD of ASC are ASC and ASC-b, while mouse J774A1 macrophages predominantly express ASC and a putative ASC-c.

Figure 2.

Three novel ASC isoforms. (A) Clustal W alignment of ASC, ASC-b, ASC-c and ASC-d. ASC consists of a PYD, linker, and CARD, while ASC-b displays an in frame deletion of amino acids 93 to 111, corresponding to the complete linker region. ASC-c lacks amino acids 26 to 85 corresponding to helices 3 to 6 of the ASC-PYD, and in ASC-d amino acids 36-195 are replaced with 69 unrelated amino acids due to a frame shift resulting in the deletion of nucleotides 107 to 134 in ASC-d. (B) Schemata showing the domain structure of the ASC isoforms. (C) Myc-tagged ASC, ASC-b, ASC-c and ASC-d were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells and expression of ASC proteins with the predicted molecular weight was verified by immunoblot using anti-myc antibodies.

At least two of the three alternative transcripts, ASC-b and ASC-c are likely generated through alternative mRNA splicing. The linker is encoded on exon 2 and is flanked by splice donor and acceptor sites. ASC-c likely utilizes an alternative 3' and 5' splice site and contains a potential splice acceptor site and a less conserved splice donor site. Generation of ASC-d could involve RNA editing, but its relationship to ASC and its generation and function in inflammasome regulation will need further investigations, due to its limited homology to ASC.

ASC, ASC-b, ASC-c and ASC-d display distinct localization patterns

Ectopic expression of ASC displays a very characteristic localization pattern. It either localizes to the nucleus, diffusively throughout the cell, or to a perinuclear aggregate [44-46]. However, we recently demonstrated that this localization pattern is neither random nor caused by over expression of ASC, but that a similar distribution is also found for endogenous ASC, which is nuclear in resting macrophages, but is redistributed to cytoplasmic perinuclear aggregates in response to inflammatory activation of macrophages [37]. Therefore we investigated the localization patterns of the three alternate ASC proteins. Expression plasmids encoding each of the ASC isoforms were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells, and their subcellular distribution was analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. As previously reported, expression of full-length ASC resulted in the formation of the perinuclear aggregate (Figure 3, 1st panel) or localization to the nucleus (Figure 3, 2nd panel). However, none of the other isoforms retained the capacity to form these structures, but rather exhibited their own, unique localization pattern. ASC-b displayed a diffuse, exclusively cytoplasmic distribution (Figure 3, 3rd panel), suggesting that either the linker is required for ASC self-aggregation and nuclear import, or some degree of flexibility provided by the linker is required for nuclear localization of ASC. ASC-c was also found exclusively in the cytoplasm. However, it oligomerized into long, filamentous structures, referred to as death filaments, which are also observed when the CARD or PYD of ASC is expressed by itself (Figure 3, 4th panel) [47]. ASC-d localized primarily diffuse to the cytosol (Figure 3, 5th panel). These results suggest that the linker region of ASC is required for efficient self-aggregation.

Figure 3.

Localization of ASC isoforms. Subcellular localization of the myc-tagged ASC isoforms was examined in transiently transfected HEK293 cells. Cells were fixed and immunostained with monoclonal anti-myc antibodies and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugatetd secondary antibodies. Nuclei and actin were visualized using Topro-3 and Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated phalloidin, respectively. Images were acquired by laser scanning confocal microscopy, showing from left to right ASC (green), nucleus (blue), actin (red) and a merged composite image. The panels show ASC (1st and 2nd panels), ASC-b (3rd panel), ASC-c (4th panel), ASC-d (5th panel), and vector control (6th panel).

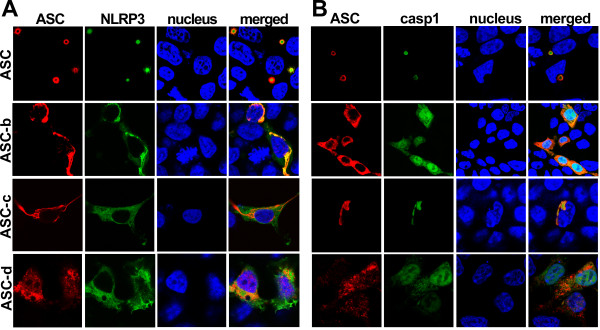

ASC, ASC-b, ASC-c and ASC-d exhibit differences in their ability to co-localize with other inflammasome components

ASC functions as an adaptor by interacting with NLRPs by PYD-PYD and with caspase 1 by CARD-CARD interaction, which are both essential to form inflammasomes, and all three proteins co-localize to aggregates [37]. We therefore tested the ability of the ASC isoforms to function as an inflammasome adaptor. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with a constitutively active GFP-tagged NLRP3R260W mutant and each myc-epitope tagged ASC isoform, immunostained with myc-specific antibodies and analyzed for co-localization by immunofluorescence microscopy. As previously shown, full-length ASC and NLRP3R260W co-localized in the perinuclear aggregates, when co-transfected (Figure 4A, 1st panel). As expected, ASC-b, which still retains a fully intact PYD, also co-localized with NLRP3R260W. Co-expression of NLRP3 caused ASC-b to relocate from its diffuse cytosolic localization to form aggregates with NLRP3 (Figure 4, 2nd panel). NLRP3 or NLRP3R260W expression alone does not cause NLRP3 aggregation (data not shown). However, while these aggregates did exhibit a perinuclear localization, they were not as small and condensed as those observed with ASC. As expected due to lacking an intact PYD, neither ASC-c nor ASC-d was able to co-localize with NLRP3R260W (Figure 4, 3rd and 4th panel).

Figure 4.

Localization of ASC isoforms, NLRP3, and caspase 1. ASC isoforms were transiently co-transfected into HEK293 cells with GFP-tagged NALP3R260W (A) or GFP-tagged pro-caspase 1C285A (B). Cells were fixed and immunostained with polyclonal anti-myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Topro-3 was used to visualize the nucleus. All images were acquired using laser scanning confocal microscopy with a 100x oil-immersion objective. Panels from left to right show ASC (red), NLRP3 or pro-caspase-1 (green), nucleus (blue), and a merged composite image.

Since ASC bridges NLRs with caspase 1, we next evaluated the capability of the ASC isoforms to interact with caspase 1. Because activation of caspase 1 would result in proteolytic cleavage of the CARD of pro-caspase 1, we expressed the C285A catalytically inactive mutant. We transiently co-transfected HEK293 cells with a GFP-pro-caspase 1C285A fusion protein and each of the ASC isoforms, which were immunostained as above and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. As previously shown, ASC did co-localize with caspase 1 into the characteristic aggregates (Figure 4B, 1st panel) [15]. Also ASC-b, and ASC-c, which both contain an intact CARD, co-localized with pro-caspase 1, though this did not cause aggregation of ASC, suggesting that pro-caspase 1 is not sufficient to cause aggregation of ASC in the absence of an NLR (Figure 4B, 2nd and 3rd panel). ASC-b retained the diffuse cytosolic localization pattern that it exhibited when expressed alone. Furthermore, it only co-localized with cytoplasmic caspase 1, as it was excluded from the nucleus. ASC-c co-localized with caspase 1 in the long filamentous structures formed by ASC-c. In contrast, ASC-d did not co-localize with pro-caspase 1, as expected due to the lack of the CARD (Figure 4B, 4th panel).

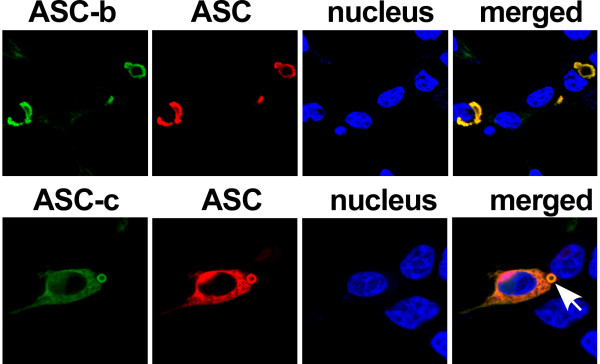

ASC co-localizes with ASC-b and ASC-c

One of the mechanisms by which inflammasome assembly is regulated is through competitive PYD-PYD and CARD-CARD interactions between PYD-only proteins (POPs) or CARD-only proteins (COPs) with ASC, caspase 1 and NLRs [36]. Previous studies demonstrated that ASC can self-oligomerize via its CARD or PYD [40,48], we wanted to explore the possibility that the truncated ASC isoforms, ASC-b and ASC-c, could impair the inflammasome adaptor function of ASC. Co-expression of ASC with ASC-b resulted in the co-localization of both proteins in the perinuclear aggregates. However, the aggregates differed from those assembled by expression of ASC, and resulted in the formation of large, irregularly shaped perinuclear aggregates, rather than the small, circular structures formed by ASC a alone (Figure 5, 1st panel). Co-expression of ASC with ASC-c also altered its subcellular localization pattern. Instead of the long filamentous structures formed by ASC-c, co-expression of ASC caused the recruitment of ASC-c to the perinuclear ASC aggregates. However, unlike those observed upon co-expression with ASC-b, these aggregates maintained all of the previously identified characteristics of ASC aggregates (Figure 5, 2nd panel). However, there is also notably less efficient self aggregation of ASC in the presence of ASC-c, further suggesting that ASC-c potentially interferes with ASC oligomerization. These results indicate that the shorter isoforms can co-localize with ASC causing their recruitment to the ASC formed aggregate.

Figure 5.

Co-localization of ASC with ASC-b and ASC-c. HEK 293 cells were transiently co-transfected with HA-tagged ASC and myc-tagged ASC-b (1st panel) or ASC-c (2nd panel). Cells were fixed and immunostained with monoclonal anti-myc (Millipore) and polyclonal anti-HA (Abcam) antibodies, and Alexa Fluor-488 and -546 conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen), respectively. Topro-3 was used to visualize the nucleus. All images were acquired using laser scanning confocal microscopy with a 100× oil-immersion objective. Panels from left to right show ASC-b/ASC-c (green), ASC (red), nucleus (blue) and a merged composite image. An arrow points to the aggregate.

Distinct ASC isoforms can either activate or inhibit inflammasome-mediated maturation of IL-1β

Because ASC is essential for inflammasome formation and maturation and release of IL-1β in macrophages, we next determined how the different ASC isoforms impact inflammasome activity. We reconstituted NLRP3 inflammasomes in HEK293 cells, which lack endogenous expression of inflammasome components, but active inflammasomes can be formed by transient expression of the core inflammasome components [37-39]. Cells were transiently co-transfected with expression plasmids encoding pro-IL-1β, pro-caspase 1, and each of the ASC isoforms in the presence or absence of the constitutively active NLRP3R260W. Culture supernatants were collected thirty-six hours post-transfection and analyzed for released IL-1β by ELISA. Only ASC and ASC-b, which contain both the PYD and the CARD, were able to promote release of IL-1β into culture supernatants (Figure 6A). Lacking the linker domain reduced the ability of ASC-b to function as an inflammasome adaptor, although it contains the necessary PYD and CARD. As expected, neither ASC-c nor ASC-d was able to generate mature IL-1β.

Figure 6.

Distinct ASC isoforms can function as either activating or inhibitory inflammasome adaptor. (A) Inflammasomes were reconstituted in HEK293 cells by transient transfection of pro-IL-1β, pro-caspase 1, ASC, ASC-b, ASC-c, ASC-d, in the absence (black bars) or presence (gray bars) of the constitutive active NLRP3R260W, as indicated. Culture supernatants were analyzed for secreted IL-1β by ELISA 36 hours post transfection. (B) The ASC deficient RAW264.7 mouse macrophage cell line was stably transfected with empty vector, myc-tagged ASC, or myc-tagged ASC-b and analyzed for IL-1β release in resting cells (black bars) and following LPS (300 ng/ml)/ATP (5 mM) activation (gray bars). (C) Inflammasomes were reconstituted in HEK293 cells as shown in Figure 6A. Secreted IL-1β was analyzed by ELISA. All experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3, +/- SD). (D) Control THP-1 cells (Ctrl) or THP-1 cells stably expressing high levels of ASC-c (#1) or low levels of ASC-c (#2) were treated with LPS (300 ng/ml) for 16 hours and analyzed for IL-1β release. Expression of ASC-c was determined by immunoblot. (E) Control J774A1 cells (Ctrl) or J774A1 cells stably expressing ASC-c were treated with LPS (300 ng/ml) for 16 hours, pulsed with 3 mM ATP for 15 minutes and analyzed for IL-1β release. Experiments in D and E were performed in triplicates (n = 2, +/- SD). Expression of ASC-c was determined by immunoblot. Note that the lysates from THP-1 and J774A1 cells were separated on the same gel and are the same exposure time.

The RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage cell line lacks ASC and is therefore deficient in the processing and release of IL-1β [49]. To test the two activating ASC isoforms under more physiological conditions, we stably transfected RAW264.7 cells with myc-tagged ASC, ASC-b, or an empty plasmid in an effort to restore the ASC deficiency in these cells. Control cells, ASC, and ASC-b stable cells were either left untreated or activated with LPS/ATP and culture supernatants were analyzed for secreted IL1β by ELISA. As previously shown, control cells did not process and release IL-1β in response to LPS and ATP. However, restoring ASC or ASC-b expression did result in a limited increase in IL-1β secretion in response to LPS/ATP, compared to resting cells (Figure 6B). As shown above in our inflammasome reconstitution system, also stable expression of ASC-b is less potent as inflammasome adaptor compared to ASC. Expression of ASC and ASC-b was confirmed by immunoblot using myc-specific antibodies (Figure 6B, insert).

Since we showed above that ASC-c and ASC-d are unable to function as inflammasome adaptor, but at least ASC-c is capable of co-localizing with caspase 1, we tested, whether ASC-c can interfere with the function of ASC as inflammasome adaptor by competing for caspase 1. We used the NLRP3 inflammasome reconstitution assay and transfected either ASC with empty vector, ASC-b, ASC-c, or ASC-d, in addition to pro-IL-1β, pro-caspase 1 and NLRP3R260W, and analyzed the culture supernatants for IL-1β as above. Co-transfection of ASC along with ASC-b caused a reduction of IL-1β release, likely because in some inflammasomes the less potent ASC-b is incorporated. As expected, co-transfection of ASC-c did significantly reduce IL-1β levels in the supernatant, suggesting that ASC-c might function similar as a CARD-only protein (COP). However, co-transfection of ASC-d did not significantly affect the previously characterized function of ASC, as determined by the similar levels of IL-1β detected in the supernatant (Figure 6C), indicating that generation of different isoforms of ASC have the potential to differentially regulate inflammasome activity. To further investigate the effect of ASC-c on inflammasome activity in a relevant cell system, we generated stable ASC-c expressing human THP-1 monocytic cell lines and mouse J774A1 macrophages by lentiviral transduction. THP-1Ctrl and THP-1ASC-c#1 (ASC-c high expressing cells) and THP-1ASC-c#2 (ASC-c low expressing cells) were treated with LPS for 16 hours and culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-1β release. While THP-1Ctrl cells robustly responded with IL-1β release to LPS treatment, THP-1ASC-c#1 cells and to a much lesser extent THP-1ASC-c#2 cells were impaired in IL-1β release, which inversely correlated with the expression levels of ASC-c, as shown by immunoblot (Figure 6D). J774A1 macrophages require LPS priming followed by ATP pulsing to secrete IL-1β. As observed for THP-1 cells, also J774A1ASC-c cells, which express an intermediate level of ASC-c, showed diminished IL-1β release compared to J774A1Ctrl cells following LPS priming and ATP pulsing (Figure 6E).

Discussion

We report the existence of novel alternative isoforms of the essential inflammasome adaptor ASC, which have the potential to differentially regulate inflammasomes. They either promote (ASC, ASC-b), inhibit (ASC-c) or do not impact (ASC-d) inflammasome function. However, it still needs to be established, whether these alternative splice forms of ASC also contribute to inflammasome activity on endogenous level. Post-transcriptional modifications, such as alternative splicing, are common in genes regulating apoptotic and inflammatory pathways [50,51], and as much as 94% of all human genes undergo alternative splicing [52]. Alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs enables the production of multiple transcripts and proteins with distinct functions from a single gene. It has been observed for transcripts encoding several other inflammatory adaptor proteins, including the Nod adaptor RIP2 and the TLR/IL-1R adaptor MyD88, IRAK1 and IRAK2, and results in either activating or inhibitory effects on downstream signaling [53-56]. Based on annotated cDNA sequences and antibody mapping, we identified three novel isoforms of ASC, designated ASC-b, ASC-c, and ASC-d. Two of these isoforms are most likely generated through alternative splicing of the ASC pre-mRNA, while the mechanism giving rise to ASC-d remains unclear.

The significance of identifying different ASC isoforms generated by alternative splicing, is their different ability to function as inflammasome adaptor. While ASC shows the strongest activity as inflammasome adaptor, ASC-b shows reduced activity in gene transfer experiments and when restored in the ASC deficient RAW264.7 macrophage cell line, suggesting that the level of inflammasome activity can be regulated by availability of recruited ASC or ASC-b. ASC-b is commonly co-expressed with ASC and both function as inflammasome adaptor, though with different efficacy. Therefore the observed upregulation of ASC-b following prolonged LPS treatment in primary human macrophages can be expected to affect inflammasome activity. In our hands, ASC-b consistently displayed lower activity compared to ASC, while Matsushita and colleagues recently showed an increase in activity of ASC-b. This discrepancy might result from the system used to address the role of ASC versus ASC-b. Matsushita and colleagues tested activity of ASC and ASC-b by co-expressing pro-caspase 1, pro-IL-1β and either ASC or ASC-b. Our localization data demonstrated that both equally co-localize with caspase 1 and also interact to a similar extend, as determined biochemically by in vitro GST pull down assay, eliminating that binding differences to caspase 1 are responsible for this result (Figure 7). Ectopic expression of ASC resulted in the formation of perinuclear aggregates, while deletion of the linker prevented these aggregates and forced ASC-b to the cytosol. However, co-expression with constitutively active NLRP3R260W or full-length ASC, but not caspase 1 was able to restore aggregate formation, suggesting that the linker is essential for self-oligomerization of ASC, but that ASC-b retains the ability to oligomerize with ASC, NLRs and caspase 1 into inflammasomes. There is currently no indication that caspase 1 itself would cause oligomerization of ASC and caspase 1 activation. The proposed mechanism suggests that NTP-mediated NLR oligomerization causes aggregation of ASC and clustering of caspase 1, followed by activation of caspase 1 by induced proximity, and our results suggest that NLRs cause ASC aggregation even in the absence of ASC self-aggregation. We performed this assay in the presence of a constitutive active NLRP3 mutant to trigger assembly of inflammasomes, which allowed us to transfect very low concentrations of ASC to prevent any effects resulting from self-oligomerization of ASC in this assay. In addition, stable expression of ASC or ASC-b in RAW264.7 macrophages resulted in low ASC expression and inflammasomes were activated using LPS/ATP, which has been recently shown by others and us to cause aggregation of ASC, NLRP3 and caspase 1 [37,57]. In this system, the lower activity of ASC-b is consistent with a recent analysis of the structure of intact ASC, which concluded that the linker region, which is absent in ASC-b, is required for providing the necessary degree of flexibility for ASC to facilitate the PYD and CARD interactions essential for inflammasome formation [58]. Thus, lack of this flexible linker would significantly impair the capability of ASC to simultaneously interact with NLRs and caspase 1, resulting in reduced maturation of IL-1β, which is consistent with our observation. Nevertheless, ASC-caspase 1 oligomers in the absence of NLRs have been implicated in pyroptosis, suggesting that ASC-b might likely prevent pyroptosis as well, while still being able to promote IL-1β and IL-18 maturation [59]. Thus, recruitment of ASC-b to pyroptosomes might be another mechanism aside from quickly releasing caspase 1 into the culture medium to prevent inflammation-induced cell death. In addition, since ASC-b is cytosolic, either the linker is directly responsible for nuclear import of ASC or some degree of flexibility provided by the linker is required for nuclear localization of ASC.

Figure 7.

ASC and ASC-b interact with pro-caspase 1 with similar affinity. Immobilized GST-caspase 1-CARD was incubated with in vitro translated and biotinylated ASC or ASC-b and subjected to in vitro GST-pull down assays using GST-caspase 1-CARD and GST control immobilized to GSH Sepharose, as indicated. Bound proteins were visualized with streptavidin-HRP and ECL-Plus detection (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). 10% of the in vitro translated proteins were loaded as 'input".

Ectopic expression of ASC-c resulted in the formation of long cytosolic filamentous structures, as shown for other proteins consisting of only a death domain fold, including ASC-CARD [48,60]. Thus, formation of these structures was consistent with the domain structure of ASC-c, which possessed a severely truncated PYD connected by the linker to the CARD. As predicted, ASC-c retained its ability to co-localize with caspase 1, which was also recruited into the filaments, while it was not capable of co-localizing with active NLRP3R260W, which would require an intact PYD. ASC-c was also able to co-localize with full-length ASC, likely, because ASC can dimerize via CARD [48]. ASC-c is essentially comprised of a CARD and might represent another member of the natural caspase 1 inhibitory CARD-only protein (COP) family [36]. Consistently, recruitment of ASC-c significantly impaired inflammasome assembly and prevented maturation of IL-1β, due to lack of an intact PYD, which is required to bridge NLRs with caspase- 1 in inflammasome reconstitution assays as well as following stable expression in LPS-activated human monocytic THP-1 cells and mouse J774A1 macrophages, indicating that in contrast to ASC and ASC-b, ASC-c appears to function as an inhibitory protein. ASC-c is low abundantly expressed in THP-1 cells, but is highly expressed in mouse J774A1 cells, where it potentially might offset the lack of CARD-only proteins in mice [36]. We did not detect ASC-c under the tested conditions in PBM, but primary human macrophages express significant lower ASC levels compared to THP-1 cells, and thus ASC-c might have been below our detection limit.

The lack of any conserved domain in ASC-d suggests that it is not functional as inflammasome adaptor. ASC-d did neither co-localize with caspase 1 nor with active NLRP3R260W, suggesting that the portion of the PYD expressed was insufficient to mediate a stable PYD-PYD interaction. Current models predict PYD-PYD interactions utilizing surfaces on either α-helices 2 and 3 or 1 and 4, suggesting that the α-helices 1 and 2 present in ASC-d are insufficient to mediate PYD-PYD interactions [61]. The interaction between ASC and NLRP3 likely occurs at a positive electrostatic potential surface (EPSP) patch on the PYD of ASC formed by Lys21, Lys22, Lys26 and Arg41, and a negative EPSP on NLRP3, and ASC-d lacks Arg41 [62]. We also could not detect endogenous ASC-d by immunoblot, although it should be detectable by ASC antibodies recognizing the PYD between amino acids 1 to 37. One explanation might be that ASC-d is expressed at very low levels, is not very stable, as indicated from transient expression experiments, is only temporarily expressed, or is not induced by the tested pro-inflammatory stimuli, but rather by anti-inflammatory stimuli during the resolution of inflammatory responses, as recently shown for Nod2. Nod2 functions as a PRR for MDP, while the dominant negative Nod2-S, which has a premature stop in the second CARD due to lack of exon 3, is induced specifically by the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, but repressed by TNF-α and IFN-γ [63]. Alternatively, splicing of ASC-d could be a mechanism to prevent generation of transcripts encoding activating ASC proteins [64]. A similar scenario has been recently proposed for RIP2-β, an alternative splice form of RIP2 lacking any of the known functions of RIP2 [56]. However, ASC-d could have a yet to be identified function, which is in part supported by the unique localization pattern observed in some cells. Nevertheless, due to the low degree of conservation between ASC and ASC-d, the precise relationship, if any, of ASC-d to ASC is currently elusive and will need further investigation.

To gain more insights into the precise expression pattern and function of ASC isoforms, further expression profiling following different cytokine treatment will be needed. One can also assume that different ASC isoforms might likely impact also other functions of ASC, including apoptosis, anoikis, pyroptosis, NF-κB and MAPK activation, however, this will need further studies. Our study revealed the existence of alternative splice variants of ASC, suggesting that the presence of distinct combinations of ASC splice variants might potentially affect inflammasome activity at different stages of the inflammatory response, and further emphasizes the existence of multiple regulatory mechanisms controlling IL-1β and IL-18 processing and release in macrophages and the significance of alternative splicing in fine-tuning the inflammatory host response.

Conclusions

Generation of different splice variants of ASC potentially provides a mechanism to regulate assembly and activity of inflammasomes and thereby release of IL-1β and IL-18 during the inflammatory host response. Expression of different ratios of activating and inhibitory isoforms of ASC might promote inflammation at early stages of infections and tissue damage, but potentially also allows to terminate these reactions during the resolution phase.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

NBB, AD, SJK and CY carried out the experiments, NBB and AD also drafted the manuscript, YR was involved in the design and interpretation of results, and CS conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, performed experiments and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Nicole B Bryan, Email: nbryan@mix.wvu.edu.

Andrea Dorfleutner, Email: a-dorfleutner@northwestern.edu.

Sara J Kramer, Email: sara-kramer@northwestern.edu.

Chawon Yun, Email: chawon-yun@northwestern.edu.

Yon Rojanasakul, Email: yrojan@hsc.wvu.edu.

Christian Stehlik, Email: c-stehlik@northwestern.edu.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the NIH (grants 5R01GM071723 and 1R21AI082406 to C.S). Plasmids pMD2.G and psPAX2 were kindly provided by Didier Trono (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne). This work was supported by the West Virginia University Imaging Core Facility and the Northwestern University Monoclonal Antibody Facility and a Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI CA060553).

References

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The Inflammasome: A molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-1b. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-18, and the interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M, Ruegg A, Werner S, Beer HD. Active caspase 1 is a regulator of unconventional protein secretion. Cell. 2008;132:818–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao W, Yeretssian G, Doiron K, Hussain SN, Saleh M. The caspase 1 digestome identifies the glycolysis pathway as a target during infection and septic shock. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36321–36329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708182200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Mayor A, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes: guardians of the body. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:229–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: guardians of cytosolic sanctity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:95–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting JP, Kastner DL, Hoffman HM. CATERPILLERs, pyrin and hereditary immunological disorders. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:183–195. doi: 10.1038/nri1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura Y, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. The inflammasome: first line of the immune response to cell stress. Cell. 2006;126:659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Munoz-Planillo R, Nunez G. The inflammasome: a caspase 1-activation platform that regulates immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ni.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting JP, Lovering RC, Alnemri ES, Bertin J, Boss JM, Davis BK, Flavell RA, Girardin SE, Godzik A, Harton JA. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity. 2008;28:285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JA, Bergstralh DT, Wang Y, Willingham SB, Ye Z, Zimmermann AG, Ting JP. Cryopyrin/NALP3 binds ATP/dATP, is an ATPase, and requires ATP binding to mediate inflammatory signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8041–8046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611496104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustin B, Lartigue L, Bruey JM, Luciano F, Sergienko E, Bailly-Maitre B, Volkmann N, Hanein D, Rouiller I, Reed JC. Reconstituted NALP1 inflammasome reveals two-step mechanism of caspase 1 activation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasula SM, Poyet J-L, Razmara M, Datta P, Zhang Z, Alnemri ES. The PYRIN-CARD protein ASC is an activating adaptor for Caspase 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21119–21122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehlik C, Lee SH, Dorfleutner A, Stassinopoulos A, Sagara J, Reed JC. Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain is a regulator of procaspase 1 activation. J Immunol. 2003;171:6154–6163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, Vucic D, French DM, Lee WP, Roose-Girma M, Erickson S, Dixit VM. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase 1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Yaginuma K, Tsutsui H, Sagara J, Guan X, Seki E, Yasuda K, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Nakanishi K. ASC is essential for LPS-induced activation of procaspase 1 independently of TLR-associated signal adaptor molecules. Genes Cells. 2004;9:1055–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Szczepanik M, Lara-Tejero M, Lichtenberger GS, Grant EP, Bertin J, Coyle AJ, Galan JE, Askenase PW, Flavell RA. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase 1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JW, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Datta P, Wu J, Juliana C, Solorzano L, McCormick M, Zhang Z, Alnemri ES. Pyrin activates the ASC pyroptosome in response to engagement by autoinflammatory PSTPIP1 mutants. Mol Cell. 2007;28:214–227. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckstummer T, Baumann C, Bluml S, Dixit E, Durnberger G, Jahn H, Planyavsky M, Bilban M, Colinge J, Bennett KL, Superti-Furga G. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ni.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009;458:509–513. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Ablasser A, Charrel-Dennis M, Bauernfeind F, Horvath G, Caffrey DR, Latz E, Fitzgerald KA. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase 1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 2009;458:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature07725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Muruve DA, Tschopp J. Innate immunity: cytoplasmic DNA sensing by the AIM2 inflammasome. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R262–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Mailloux CM, Gowan K, Riccardi SL, LaBerge G, Bennett DC, Fain PR, Spritz RA. NALP1 in vitiligo-associated multiple autoimmune disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1216–1225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Gaide O, Petrilli V, Martinon F, Contassot E, Roques S, Kummer JA, Tschopp J, French LE. Activation of the IL-1beta-processing inflammasome is involved in contact hypersensitivity. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1956–1963. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omi T, Kumada M, Kamesaki T, Okuda H, Munkhtulga L, Yanagisawa Y, Utsumi N, Gotoh T, Hata A, Soma M. An intronic variable number of tandem repeat polymorphisms of the cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome 1 (CIAS1) gene modifies gene expression and is associated with essential hypertension. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1295–1305. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeyer L, Keller M, Niklaus G, Hohl D, Werner S, Beer HD. The inflammasome mediates UVB-induced activation and secretion of interleukin-1beta by keratinocytes. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1140–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren S, Hoffman HM, Bugbee W, Boyle DL. Expression and regulation of cryopyrin and related proteins in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:708–714. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.025577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle A, Hornung V, Petzold GC, Stewart CR, Monks BG, Reinheckel T, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Moore KJ, Golenbock DT. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:857–865. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church LD, Churchman SM, Hawkins PN, McDermott MF. Hereditary auto-inflammatory disorders and biologics. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2006;27:494–508. doi: 10.1007/s00281-006-0015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojanov S, Kastner DL. Familial autoinflammatory diseases: genetics, pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:586–599. doi: 10.1097/bor.0000174210.78449.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium TFF. A candidate gene for familial mediterranean fever. Nat Genet. 1997;17:25–31. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium TIF. Ancient missense mutations in a new member of the RoRet gene family are likely to cause familial mediterranean fever. Cell. 1997;90:797–807. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoham NG, Centola M, Mansfield E, Hull KM, Wood G, Wise CA, Kastner DL. Pyrin binds the PSTPIP1/CD2BP1 protein, defining familial Mediterranean fever and PAPA syndrome as disorders in the same pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13501–13506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135380100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehlik C, Dorfleutner A. COPs and POPs: Modulators of Inflammasome Activity. J Immunol. 2007;179:7993–7998. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.7993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan NB, Dorfleutner A, Rojanasakul Y, Stehlik C. Activation of inflammasomes requires intracellular redistribution of the apoptotic speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain. J Immunol. 2009;182:3173–3182. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfleutner A, Bryan NB, Talbott SJ, Funya KN, Rellick SL, Reed JC, Shi X, Rojanasakul Y, Flynn DC, Stehlik C. Cellular PYRIN domain-only protein (cPOP) 2 is a candidate regulator of inflammasome activation. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1484–1492. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01315-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfleutner A, McDonald SJ, Bryan NB, Funya KN, Reed JC, Shi X, Flynn DC, Rojanasakul Y, Stehlik C. A Shope Fibroma virus PYRIN-only protein modulates the host immune response. Virus Genes. 2007;35:685–694. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehlik C, Krajewska M, Welsh K, Krajewski S, Godzik A, Reed JC. The PAAD/PYRIN-only protein POP1/ASC2 is a modulator of ASC-mediated NF-kB and pro-Caspase 1 regulation. Biochem J. 2003;373:101–113. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoya F, Sandler LL, Harton JA. Pyrin-only protein 2 modulates NF-kappaB and disrupts ASC:CLR interactions. J Immunol. 2007;178:3837–3845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JB, Barrett JW, Nazarian SH, Goodwin M, Ricuttio D, Wang G, McFadden G. A poxvirus-encoded pyrin domain protein interacts with ASC-1 to inhibit host inflammatory and apoptotic responses to infection. Immunity. 2005;23:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K, Takeoka M, Sagara J, Itano N, Kurose Y, Nakamura A, Taniguchi S. A splice variant of ASC regulates IL-1beta release and aggregates differently from intact ASC. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:287387. doi: 10.1155/2009/287387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto J, Taniguchi S, Ayukawa K, Sarvotham H, Kishino T, Niikawa N, Hidaka E, Katsuyama T, Higuchi T, Sagara J. ASC, a novel 22-kDa protein, aggregates during apoptosis of human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33835–33838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell BB, Vertino PM. Activation of a caspase-9-mediated apoptotic pathway by subcellular redistribution of the novel caspase recruitment domain protein TMS1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6243–6247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards N, Schaner P, Diaz A, Stcukey J, Shelden E, Wadhwa A, Gumucio DL. Interaction between Pyrin and the apoptotic speck protein (ASC) modulates ASC-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39320–39329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehlik C, Fiorentino L, Dorfleutner A, Bruey JM, Ariza EM, Sagara J, Reed JC. The PAAD/PYRIN-family protein ASC is a dual regulator of a conserved step in nuclear factor kappaB activation pathways. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1605–1615. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto J, Taniguchi S, Sagara J. Pyrin N-terminal homology domain- and caspase recruitment domain-dependent oligomerization of ASC. Biochem Biophysical Res Commun. 2001;280:652–655. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrin P, Barroso-Gutierrez C, Surprenant A. P2X7 receptor differentially couples to distinct release pathways for IL-1beta in mouse macrophage. J Immunol. 2008;180:7147–7157. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman JR, Gilmore TD. Alternative splicing in the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Gene. 2008;423:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerk C, Schulze-Osthoff K. Regulation of apoptosis by alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2005;19:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao N, Nguyen S, Ngo K, Fung-Leung WP. A novel splice variant of interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R)-associated kinase 1 plays a negative regulatory role in Toll/IL-1R-induced inflammatory signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6521–6532. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6521-6532.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy MP, O'Neill LA. The murine IRAK2 gene encodes four alternatively spliced isoforms, two of which are inhibitory. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27699–27708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens S, Burns K, Tschopp J, Beyaert R. Regulation of interleukin-1- and lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation by alternative splicing of MyD88. Curr Biol. 2002;12:467–471. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg A, Le Negrate G, Reed JC. RIP2-beta: a novel alternative mRNA splice variant of the receptor interacting protein kinase RIP2. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:1163–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Monks BG, Fitzgerald KA. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. 2009;183:787–791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Alba E. Structure and interdomain dynamics of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:32932–32941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Wu J, Yu JW, Datta P, Miller B, Jankowski W, Rosenberg S, Zhang J, Alnemri ES. The pyroptosome: a supramolecular assembly of ASC dimers mediating inflammatory cell death via caspase 1 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1590–1604. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R, Martin D, Zheng L, Ng S, Bertin J, Cohen J, Lenardo M. Death-effector filaments: novel cytoplasmic structures that recruit caspases and trigger apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1243–1253. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1243. 1243-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepinsh E, Barbals R, Dahl E, Sharipo A, Staub E, Otting G. The death-domain fold of the ASC PYRIN domain, presenting a basis for PYRIN/PYRIN recognition. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srimathi T, Robins SL, Dubas RL, Chang H, Cheng H, Roder H, Park YC. Mapping of POP1-binding site on pyrin domain of ASC. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15390–15398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801589200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstiel P, Huse K, Till A, Hampe J, Hellmig S, Sina C, Billmann S, von Kampen O, Waetzig GH, Platzer M. A short isoform of NOD2/CARD15, NOD2-S, is an endogenous inhibitor of NOD2/receptor-interacting protein kinase 2-induced signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3280–3285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZH, Wu JY. Alternative splicing and programmed cell death. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;220:64–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.1999.d01-11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]