Abstract

Objective:

The aims of this study were to examine the time-varying developmental associations between conduct problems and early alcohol use in girls between ages 11 and 15 and to test the moderating role of race.

Method:

The study is based on annual, longitudinal data from oldest cohort in the Pittsburgh Girls Study (n = 566; 56% African American, 44% White). Two models of the association between conduct problems and alcohol use were tested using latent growth curve analyses: conduct-problem-effect (conduct problems predict time-specific variation in alcohol use trajectory) and alcohol-effect (alcohol use predicts time-specific variation in conduct problem trajectory) models.

Results:

Girls' conduct problems and alcohol use increased over ages 11-15. Results provided support for a conduct-problem-effect model, although the timing of the associations between conduct problems and alcohol use differed by ethnicity. Among White girls, conduct problems prospectively predicted alcohol use at ages 11-13 but not later, whereas among African American girls, prospective prediction was observed at ages 13-14 but not earlier.

Conclusions:

Study findings indicate developmental differences in the time-varying association of conduct problems and alcohol use during early adolescence for African American and White girls. Ethnic differences in the development of alcohol use warrant further study, and have potential implications for culture-specific early screening and preventive interventions.

The link between conduct problems and adolescent alcohol use is robust (see reviews by Cerda et al., 2008, and White and Gorman, 2000). However, the direction of the developmental association between conduct problems and alcohol use over time remains unclear. Specifically, conduct problems may predict alcohol use, alcohol use may predict conduct problems, or conduct problems and alcohol use may reciprocally influence one another (e.g., Huang et al., 2001; White et al., 1993; Young et al., 2008). Alternatively, both conduct problems and alcohol use may be predicted by common risk factors (White, 1997). Few studies have focused on the time-varying (i.e., year-to-year) associations between conduct problems and alcohol use in females, although females are at increased risk for conditions that are comorbid with substance use (Costello et al., 2006). Furthermore, little is known about racial/ethnic differences in the association between conduct problems and alcohol use. Greater understanding of the time-varying association between conduct problems and alcohol use during early adolescence, a period when alcohol use begins to emerge, has implications for revealing etiologic mechanisms, and informing the timing and content of alcohol prevention efforts. We use longitudinal data, collected annually, from the Pittsburgh Girls Study (PGS) to test two models of the time-varying association between conduct problems and alcohol use during early adolescence, and the moderating effects of race/ethnicity, in African American and White girls.

Adolescent females are less likely to report alcohol use, compared with their male counterparts, and tend to drink smaller quantities with less frequency (e.g., Johnston et al., 2009; Tucker et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the narrowing gender gap in rates of substance use (Johnston et al., 2009) and females' greater risk for conditions that are comorbid with substance use compared with males (Costello et al., 2006) urge the need for increased understanding of factors, such as conduct problems, that may influence the course of alcohol use in order to prevent alcohol-related harm in females. In addition, racial/ethnic differences in patterns of alcohol use have been identified, such that African American youth tend to have later onset (e.g., Wallace et al., 2003), and somewhat distinct developmental trajectories of alcohol use compared with White youth (Flory et al., 2006; Tucker et al., 2003). Little is known about possible racial/ethnic differences in the role of conduct problems in relation to the development of alcohol use, although some research suggests that externalizing behaviors may be a more important predictor of alcohol use in White, compared with African American, girls (e.g., Chung et al., 2008).

Conduct problems tend to increase through adolescence (Fontaine et al., 2009; Odgers et al., 2008) and have been shown to generally precede and predict the onset of alcohol use (e.g., Sartor et al., 2007). Females are less likely to have conduct problems, compared with males (Fontaine et al., 2009). However, some studies suggest a stronger association between disruptive behavior disorders and substance use in girls, compared with boys (e.g., Hops et al., 1999; White and Hansell, 1996). Because of the low prevalence of conduct problems in girls, few studies have examined the developmental course of conduct problems in females. Emerging data from the PGS, a large urban community sample of girls, document an increase in conduct problems during adolescence and also suggest higher prevalence of conduct disorder among African American, compared with White, girls, even after controlling for socioeconomic status (Keenan et al., submitted for publication). Importantly, poverty (i.e., receipt of public assistance) was associated with roughly a doubling of the rate of conduct disorder in both African American and White girls at ages 7-14, suggesting contextual factors that may amplify risk for conduct disorder (Keenan et al., submitted for publication). This study will begin to address gaps in knowledge regarding the development of conduct problems in relation to alcohol use during early adolescence in African American and White females.

The co-occurrence of conduct problems with alcohol and other drug use may reflect a common etiological process or common risk factors. For example, conduct disorder and substance-use disorder were found to load on a single externalizing behaviors factor (e.g., Young et al., 2000), and a large proportion of the association between conduct disorder and substance-use disorder may reflect common genetic liability (e.g., Slutske et al., 1998). Little is known, however, about the time-varying nature of the association between conduct problems and alcohol use during early adolescence; thus, more fine-grained (i.e., year-to-year) analysis of the association may provide clues to processes underlying their co-occurrence.

We test two main models that have been proposed to explain the time-varying association between conduct problems and alcohol use. A “conduct-problem-effect” model proposes that conduct problems increase risk for alcohol use (White et al., 1993) and is supported by research suggesting the role of conduct disorder in facilitating the shift from substance use to substance-use disorder (Costello and Erkanli, 1999) and more rapid progression to dependence (White et al., 2001). Alternatively, an “alcohol-effect” model proposes that alcohol use may facilitate the development and maintenance of conduct problems. According to this model, the pharmacological effects of alcohol or activities related to obtaining and consuming alcohol may motivate or exacerbate conduct-disordered behavior (White et al., 1993).

Only a few studies have tested time-specific developmental associations between alcohol use and conduct problems in adolescence, especially with annual assessments starting in early adolescence, and none to date have tested for possible ethnic differences. One longitudinal study of males, which included three assessments at 3-year intervals over ages 12-18, found support for a conduct-problem-effect model, in which antisocial behavior led to increased alcohol use during adolescence (White et al., 1993). An extension of this work showed that the prospective association between aggression and alcohol use was stronger in females, compared with males (White and Hansell, 1996). Another longitudinal study, which involved a large sample of students in Scotland who were assessed bi-annually over ages 11-15, also provided support for a “risk-factor” model, as well as some evidence for reciprocal effects over time, particularly for females (Young et al., 2008). Huang et al. (2001) examined annual (with one 2-year lag), reciprocal, cross-lagged associations between alcohol use and interpersonal aggression during high school. They found reciprocal effects in later adolescence even when common risk factors were controlled and also found that gender did not moderate the observed relationships. Other studies that include data collected in late adolescence (e.g., ages 17-18) also found reciprocal relations between substance use and externalizing behaviors, such as violence and aggression (e.g., White et al., 1999). Thus, existing studies provide some support for both conduct-problem-effect and reciprocal-influence models but provide limited information on race/ethnic differences in the development of these two behaviors.

The goals of the current study were to examine the cross-sectional and prospective time-varying associations between conduct problems and alcohol use in girls during early adolescence, a time when alcohol use starts to emerge, and the extent to which these associations were moderated by race/ethnicity. We tested conduct-problem-effect and alcohol-effect models of the association between conduct problems and alcohol use. The models tested time-specific effects—that is the contemporaneous effects (i.e., cross-sectional associations) and prospective effects (i.e., prediction of behavior 1 year later) of conduct problems on the course of alcohol use, and, conversely, of alcohol use on the course of conduct problems using latent growth curve analyses. We hypothesized that a conduct-problem-effect model would be supported when using annual data collection during early to mid-adolescence. Because of limited data on racial/ ethnic differences in these associations, we had no hypothesis regarding ethnic differences in the association between conduct problems and alcohol use. This study adds to the literature on the early development of alcohol use by focusing on females and by testing for differences by ethnicity in the concurrent and prospective associations between conduct problems and alcohol use.

Method

Sample description

The PGS (N = 2,451) involves an urban community sample of four cohorts of girls, ages 5-8 at the first assessment, and their primary caretaker, who have been followed annually according to an accelerated longitudinal design. To identify the study sample, low-income neighborhoods were oversampled, such that neighborhoods in which at least 25% of families were living at or below poverty level were fully enumerated and a random selection of 50% of households in all other neighborhoods were enumerated (see Hipwell et al., 2002, for details on study design and recruitment). The analyses of growth in alcohol use and conduct problems presented here use 5 years of data collected in the oldest cohort during early adolescence, covering ages 11-15. To examine possible moderating effects of African American and White ethnicity/race on alcohol use and conduct problems, we excluded the small number of girls (n = 32) representing other ethnicities, resulting in an analysis sample of 566 African American (56.2%, n = 318) and White (43.8%, n = 248) girls who participated in at least one assessment at ages 11-15. At the age 11 assessment, the majority of caretakers were female (92.3%), most (55.4%) were cohabiting with a spouse or domestic partner, and about half (51.5%) completed 12 or fewer years of education. Caregivers' ages ranged from 25 to 76 years (M = 39.76, SD = 8.61). Retention over follow-up was high, with an average participation rate of 91.3% over the 5 years of data collection. There were no statistically significant differences between retained participants and those lost to follow-up on any variables used in this study (i.e., race, alcohol use, conduct problems, parent alcohol use, and family poverty).

Data collection

Separate in-home interviews for both the girl and caretaker were conducted annually by trained interviewers using a laptop computer. At each assessment, girls reported on their alcohol use in the past year, and caretakers reported on the girl's conduct problems and their own alcohol use in the past year. All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Families were compensated for their participation.

Measures

Alcohol use.

Girls reported on any use (i.e., sips, tastes, or full “standard drinks”) of beer, wine, or distilled spirits in the past year in response to items adapted from the Rutgers Health and Human Development Project (Pandina et al., 1984). At age 11, of those who reported drinking alcohol in the past year, 54 girls reported drinking alcohol less than once per month, and 5 girls reported drinking at least one time per month. The frequency of alcohol use increased every year. At age 12, 76 girls reported drinking alcohol less than once per month, and 11 girls reported drinking at least one time per month. At age 13, 93 girls reported drinking alcohol less than once per month, and 8 girls reported drinking at least one time per month. At age 14, 130 girls reported drinking alcohol less than once per month, and 18 girls reported drinking at least one time per month. Finally, at age 15, 138 girls reported drinking alcohol less than once per month, and 30 girls reported drinking alcohol at least one time per month. Because of the low variability in the frequency of alcohol use, past-year reports of any alcohol use (coded 0 = no, 1 = yes) at ages 11-15 were used.

Conduct problems.

Conduct problems were assessed using caretaker reports on the Child Symptom Inventory-Fourth Edition (CSI-4; Gadow and Sprafkin, 1994), when girls were ages 11-13 and the Adolescent Symptom Inventory-Fourth Edition (ASI-4; Gadow and Sprafkin, 1998), when girls were ages 14-15. We used parental report rather than girl self-report of conduct problems to avoid shared method variance with girls' self-report of alcohol use. The mean of caretaker-reported conduct problems ranged from 0.89 (SD = 1.56) at age 12 to 1.52 (SD = 2.62) at age 15. The mean of child-reported conduct problems ranged from 0.93 at age 11 (SD = 1.51) to 1.53 at age 15 (SD = 2.06). The association between caretaker and child report of conduct problems at each year was moderate in magnitude (range: r = .28, p < .001 at age 11 to r = 47, p < .001 at age 14). The CSI-4 and ASI-4 include Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) symptoms (e.g., truancy, stealing) of conduct disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) scored on a 4-point scale (0 = never to 3 = very often). Adequate concurrent validity, and sensitivity and specificity of conduct-disorder symptom scores to clinicians' diagnoses have been reported for the CSI-4 and ASI-4 (Gadow and Sprafkin, 1994, 1998). In the present study, the average internal consistency coefficient across the 5 years of data was α = .72, with values ranging from α = .66 (age 13) to α = .79 (age 14).

Covariates.

Two demographic variables—race (1 = White, 2 = African American) and receipt of public assistance, based on caretaker report, at age 11 (0 = no assistance, 1 = received assistance)—were included as covariates. At age 11, 12.7% of White caregivers reported receiving public assistance, compared with 36.5% of African American caregivers, χ2(1) = 38.47,p < .001. We controlled for public assistance because of the confound between race/ethnicity and socio-economic status.

We also controlled for the caretaker's report of their own alcohol use and antisocial behavior when the girl was age 11 to account for the possible genetic and environmental influences associated with the caretaker on girls' conduct problems and alcohol use. Caretakers completed the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Babor et al., 1992), which is a 10-item measure assessing past-year quantity and frequency of drinking and alcohol-related problems using 3- and 5-point response formats. To assess lifetime antisocial behavior, caretakers completed the 46-item Antisocial Behavior Checklist-Lifetime (ABC-L; Zucker and Noll, 1980). The ABC-L measures frequency of the caretaker's participation in a variety of antisocial activities in adolescence (e.g., lying to parents, being suspended from school) and in adulthood (e.g., resisting arrest, defaulting a debt). The scores for each item ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (often).

Data analytic plan

Latent growth curve models (LGCMs) were used to characterize change in girls' alcohol use (dichotomous variable: any vs. no use) and conduct problems (continuous variable) over ages 11-15. Because alcohol use is a binary variable, alcohol-use models were estimated using a weighted least squares estimator, and because conduct problems is an ordinal variable, these models were estimated using a robust maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus 5.2 (Muthén and Muthén, 2008). Missing data on dependent variables were handled through the use of the expectation maximization algorithm. For unconditional growth models, 566 cases were used; sample size for other analyses varied between n = 492-503 because of missing data for covariates. Model fit was evaluated using the chi-square goodness-of-fit test, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). For CFI and TLI, we used the conventional cutoff .90 or greater for acceptable fit and .95 or greater for good fit. RMSEA values between .05 and .08 represent acceptable fit, and values less than .05 indicate good fit (McDonald and Ho, 2002).

We first estimated unconditional LGCMs separately for alcohol use and conduct problems and then examined multiple group models to test for racial differences in growth parameters. Time points were fixed incrementally to reflect the annual assessment schedule (e.g., age 11 fixed at 0, age 12 fixed at 1, age 13 fixed at 2). We expected that the intercept variance and slope mean and variance parameters would be significant, indicating a steady increase in alcohol use and conduct problems in girls from age 11 to 15 years. To test for racial differences on growth parameters (i.e., intercept level and growth over time in alcohol use), we examined a series of nested multiple group models. Each of these nested models constrained a single parameter (e.g., intercept variance) to be equal for African American and White girls. We used a chi-square difference test to compare each nested model with the base model (i.e., the model that assumed the parameter to be unequal across races). If the constraint did not result in a significantly worse fit over the base model, the parameter was assumed to be equal for both races. In the multiple group analyses, we expected significantly higher initial alcohol use among White, compared with African American, girls (e.g., Johnston et al., 2009) but greater severity of conduct problems among African American, compared with White, girls (Keenan et al., submitted for publication).

Preliminary analyses suggested that alcohol and conduct problems did not meet a common factor model until age 15. (These data are not presented here but are available from the corresponding author on request.) Thus, we concluded that our data did not support a common factor model during this developmental window and did not pursue it further.

To examine whether race moderated the time-varying associations between conduct problems and alcohol use, we ran four multiple group models (i.e., contemporaneous and prospective versions of the conduct-problem-effect model, and contemporaneous and prospective versions of the alcohol-effect model) comparing African American and White girls. To control for possible confounds with family-level processes, receipt of public assistance and caretaker alcohol use and antisocial behavior were included as time-invariant covariates in all models. In the first pair of models, conduct problems were used as a time-varying predictor of growth in alcohol use, testing contemporaneous and prospective associations in separate models. Specifically, in Model 1, to investigate the extent to which conduct problems accounted for within-time (concurrent) elevations in alcohol use, we estimated a LGCM in which indicators of parent-reported conduct problem scores at ages 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 served as predictors of individual variability in girls' alcohol use at ages 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15, respectively. This model evaluated whether conduct problems were cross-sectionally associated with alcohol use above and beyond what was expected based on the individual-specific underlying developmental trajectory of alcohol use. In Model 2, we tested whether conduct problems predicted alcohol use in the next year, such that conduct problems at ages 11, 12, 13, and 14 were used to predict individual variability in alcohol use at ages 12, 13, 14, and 15, respectively. This model evaluated whether conduct problems uniquely predicted elevations in alcohol use above and beyond what was expected based on the individual specific underlying trajectory of alcohol use 1 year later.

Next, we examined the extent to which alcohol use exerted time-specific influences on the development of conduct problems in girls. In Model 3, we examined the contemporaneous influence of alcohol use on growth in conduct problems (similar to Model 1). For Model 4, we examined whether alcohol use prospectively predicted conduct problems 1 year later (similar to Model 2).

Results

Unconditional multiple group latent growth curve models

Alcohol use.

The unconditional linear LGCM for alcohol use in the total sample fit the data well: χ2(6, N = 566) = 9.39, p = .15, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .03. The LGCM had a significant mean slope (Ms = 0.19, z =4.24, p = .001), indicating a steady increase in the prevalence of alcohol use from ages 11 to 15 years (Table 1). The Ms value of 0.19 can be interpreted as the increase in proportion of alcohol users per year (0.19 × 4 [T15 −T11 =4 years] = .76), which corresponds to a 76% increase in proportion of users from ages 11 to 15. The variances for the intercept and slope were Di = .64, z =6.28, p < .001, and Ds = .04, z = 1.98, p = .048, respectively, indicating substantial variation across girls in initial use and alcohol use trajectory. Initial levels of alcohol use negatively, but marginally, predicted the alcohol-use slope factor (b = -0.11, z = -1.78,p = .075), such that higher initial levels of alcohol use at age 11 were somewhat predictive of less growth in alcohol use from ages 11 to 15. A quadratic trend in slope was not significant.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for alcohol use and conduct problems, by race, across the 5 years of assessment

| Age |

|||||

| Variable | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Alcohol users in the past year, % (n) | |||||

| African American | 7.7 (24) | 13.5 (41) | 13.2 (40) | 18.2(54) | 22.7 (67) |

| White | 14.8 (35) | 19.7 (46) | 26.8 (61) | 42.5 (94) | 45.2 (98) |

| Conduct problems in the past year, M (SD) | |||||

| African American | 1.19(1.82) | 1.10(1.73) | 1.18(1.87) | 1.68(2.72) | 1.89(2.94) |

| White | 0.78 (1.78) | 0.61 (1.24) | 0.72(1.76) | 0.88(1.73) | 1.06(2.05) |

Note: n = 566, representing girls who participated in at least one assessment at ages 11-15.

Multiple group analyses for the unconditional LGCM of alcohol use revealed that the intercept, Δχ2(1) = 6.98, p = .008, and slope means, Δχ2(1) = 39.17,p < .001, were not equivalent for African American and White girls. African American girls had a significantly lower intercept (i.e., fewer girls reporting alcohol use at age 11) and slower increase in alcohol use over time, compared with White girls. However, tests did not reveal any racial differences for intercept, Δχ2(1) = 0.20, p = .654, and slope variance, Δχ2(1) = 0.18, p = .671, indicating that the intraindividual variability in initial and developmental course of alcohol use did not differ substantially between African American and White girls.

Conduct problems.

Results indicate a nonlinear trajectory of conduct problems, such that initial levels of conduct problems at age 11 are somewhat higher relative to age 12 (Table 1). After age 12, conduct problems increased steadily through age 15. Overall, the average level of conduct problems in the sample was in the mild range, given that, in a normative sample of girls, scores greater than 2 indicated moderate conduct problem severity and scores greater than 4 indicated high conduct problem severity (Gadow and Sprafkin, 1994). The unconditional LGCM for conduct problems fit the data well: χ2(8, n = 566) = 13.90,p = .08, CFI = 1.00, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .04. The LGCM had a significant mean intercept (M = .99, z =13.51, p <.001), linear slope (Ms = -.15, z =-2.36,p = .018), and quadratic slope (Mq = .07, z =4.61, p < .001). When the linear slope variance was estimated, tests yielded a small negative variance term. Thus, the linear slope variance was set to zero (cf. Ichiyama et al., 2009). The variances for the intercept and quadratic slope wereDi= 1.65, z = 12.56, p <.001, and Dq = .016, z = 8.14, p <.001, respectively, indicating substantial variation across girls in initial conduct problems and conduct problem trajectory. The intercept and quadratic slope were not significantly correlated.

In the multiple group model testing for racial differences in growth parameters for the unconditional LGCM of conduct problems, chi-square difference tests revealed that the intercept mean was not equivalent for African American and White girls: Δχ2(1) = 9.14,p = .003. African American girls demonstrated a significantly higher intercept, suggesting that African American girls had higher initial levels of conduct problems at age 11, compared with White girls. However, no racial differences were identified for linear slope means, Δχ2(l) = 0.04,p =841, or quadratic slope means, Δχ2(1) = 0.24, p =.624, which suggests that the rate of increase in conduct problems was similar for African American and White girls. Additionally, differences in the intercept, Δχ2(1) = 0.56, p =.454, and quadratic slope variances, Δχ2(1) = 2.53, p =.112, were not observed, indicating that the intraindividual variability in initial and developmental course of conduct problems did not differ substantially between African American and White girls.

Do conduct problems predict time-specific elevations in alcohol use trajectories?

Concurrent associations (Model 1).

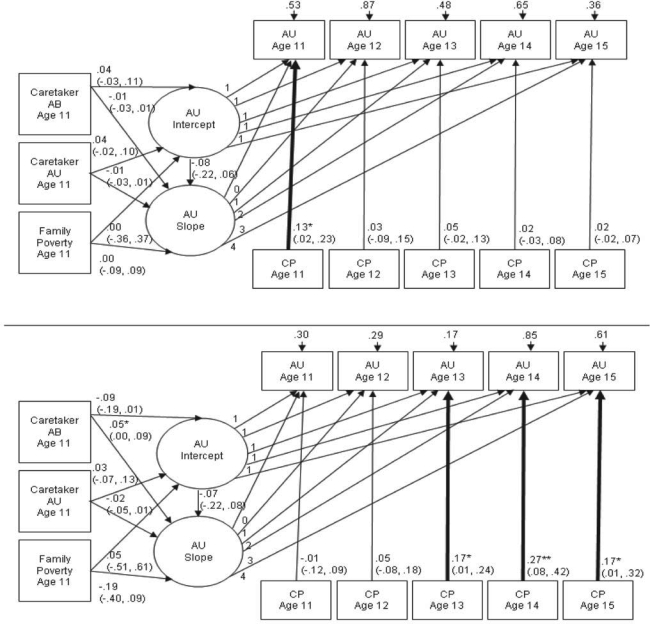

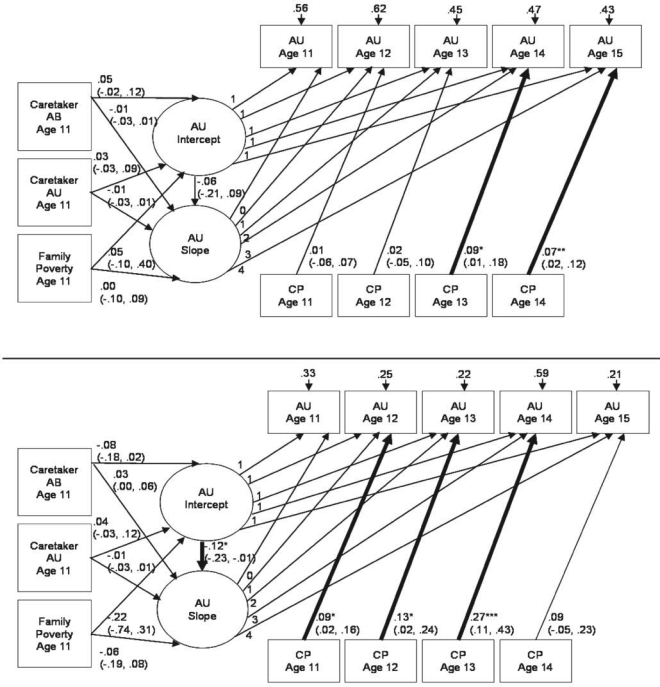

The full multiple group LGCM of girls' alcohol use, with time-invariant (i.e., receipt of public assistance, caretaker alcohol use, and caretaker antisocial behavior at age 11) and time-varying (concurrent conduct problems at ages 11-15) covariates fit the data well, χ2(42, n = 493) = 46.91,p = .278, CFI = .98, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .022. Results are shown in Figure 1. Among African American girls, those with higher conduct problem scores at age 11 were more likely to report using alcohol than would be expected based on their individual trajectories alone (b = 0.13, z = 2.41, p =.016). For African American girls, conduct problems were not associated with alcohol use at ages 12-15, suggesting that conduct problems at these ages did not significantly contribute to increases in alcohol use above and beyond girls' individual trajectories. For White girls, at ages 13-15, girls with higher conduct problem scores were more likely to report using alcohol than would be expected based on their individual trajectories of alcohol use (at age 13: b = 0.17, z =2.05, p =.041; at age 14: b = 0.27, z =2.91, p = 004; at age 15: b = 0.17, z = 2.16, p = .031). Conduct problems were not concurrently associated with alcohol use beyond what would be expected by girls' individual alcohol use trajectories at ages 11 and 12. Caretaker antisocial behavior was positively associated with growth in White girls' alcohol use.

Figure 1.

Concurrent association growth model with time-invariant and time-varying covariates for conduct problems predicting alcohol use above and beyond the growth in alcohol use that is accounted for by the alcohol use trajectory for African American (top) and White (bottom) girls. Significant parameters are denoted with asterisks and bold lines, and the 95% confidence intervals for each parameter are provided in parentheses. Residual variances for alcohol use variables are included. AU = alcohol use; AB = antisocial behavior; CP = conduct problems. *p <.05; ** p <.01.

Prospective associations (Model 2).

The full multiple group LGCM of alcohol use with time-invariant and time-varying (conduct problems at ages 11-14 as prospective predictors of alcohol use) covariates resulted in acceptable fit to the data, χ2(38, n = 503) = 44.05,p = .231, CFI = .98, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .025. Results are shown in Figure 2. For African American girls, conduct problems at age 13 (b = 0.09, z =2.01, p = .044) and age 14 (b = 0.07, z =2.78, p = .005) predicted increases in alcohol use at ages 14 and 15, respectively, beyond what would be expected by girls' individual alcohol use trajectories. Conduct problem scores at ages 11 and 12 did not exert a time-lagged influence on alcohol use at age 12 or 13, respectively, beyond what would be expected by their individual alcohol trajectories in African American girls. For White girls, conduct problems at age 11 (b = 0.09, z =2.36,p = .018), age 12 (b = 0.13, z =2.34,p = .019), and age 13 (b = 0.27, z =3.36,p < .001) predicted increases in alcohol use at ages 12, 13, and 14, respectively, beyond what would be expected by girls' individual trajectories of alcohol use. Conduct problems at age 14, however, did not prospectively predict alcohol use at age 15 beyond what would be expected by White girls' individual alcohol use trajectories.

Figure 2.

Prospective association growth model of alcohol use with time-invariant and time-varying covariates for conduct problems predicting alcohol use above and beyond the growth in alcohol use 1 year later that is accounted for by the alcohol use trajectory for African American (top) and White (bottom) girls. Significant parameters are denoted with asterisks and bold lines, and the 95% confidence intervals for each parameter are provided in parentheses. Residual variances for alcohol use variables are included. AU = alcohol use; AB = antisocial behavior; CP = conduct problems. *p <.05; **p <.01; ***p < .001.

Does alcohol use predict time-specific elevations in conduct problem trajectories?

Concurrent associations (Model 3).

The full multiple group LGCM of conduct problems with time-invariant and time-varying (concurrent alcohol use at ages 11-15) covariates did not fit the data well, χ2(66, n = 492) = 163.70,p < .001, CFI = .87, TLI = .81, RMSEA = .072, suggesting that alcohol use did not clearly predict within-time elevations in conduct problem trajectories for either racial/ethnic group.

Prospective associations (Model 4).

Similar to Model 3, the full multiple group LGCM with time-invariant and time-varying (alcohol use at ages 11-14) covariates had relatively poor fit to the data: χ2(49, n = 503) = 156.20, p < .001, CFI = .80, TLI = .87, RMSEA = .077, suggesting that alcohol use did not prospectively predict conduct problems, beyond what would be expected by girls' individual trajectories. Based on the results from Models 3 and 4, we concluded that the hypothesis that alcohol use predicts time-specific elevations in conduct problems in African American and White girls during early adolescence is not supported by the data (path results for Models 3 and 4 are available from the corresponding author on request).

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies, we found that alcohol use and conduct problems increased steadily in adolescent girls between ages 11-15. Results from contemporaneous and prospective analyses of the time-varying association between conduct problems and alcohol use provide further support for a conduct-problem-effect model, in which conduct problems predict alcohol use, in both African American and White girls during early adolescence. In contrast, the data did not provide support for an alcohol effect, replicating results obtained in some longitudinal studies (e.g., White et al., 1993; Young et al., 2008). Study results extend the existing literature by documenting ethnic differences in the development of girls' conduct problems during early adolescence, and characterizing differences in the timing of the effect of conduct problems on alcohol use trajectories in White and African American girls.

For the sample as a whole, the prevalence of alcohol use through age 15 was similar to that reported by girls in a national survey (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). The lower, on average, level of alcohol use through early adolescence among African American girls, compared with White girls, also is consistent with other studies (e.g., Flory et al., 2006). By contrast, the prevalence of conduct problems in the study sample was higher, but in the mild range overall, compared with rates reported for girls in other community surveys (e.g., Maughan et al., 2004), and likely reflects the oversampling of girls from disadvantaged neighborhoods in the PGS. The higher rate, on average, of parent-reported conduct problems among African American girls, compared with White girls, also likely reflects, in part, the greater proportion of African American families living in poverty in the study sample, given that poor neighborhood conditions are associated with conduct problems (Fontaine et al., 2009; Keenan et al., submitted for publication). Of note, the data also suggest a short-term decrease in parent-reported conduct problems at age 12, which may reflect a time-specific developmental transition (e.g., starting middle school) that warrants replication in other cohorts and samples.

The contemporaneous and prospective models of the time-varying association of conduct problems on girls' trajectory of alcohol use suggest ethnic differences in the timing and nature of the association of conduct problems as a risk factor for alcohol use in early adolescence. Among African American girls, greater conduct problem severity had a contemporaneous effect on alcohol use only at age 11. In contrast, among White girls, greater conduct problem severity had a contemporaneous effect on alcohol use at ages 13-15. Findings from the prospective associations between conduct problems and alcohol use indicate that, among African American girls, conduct problem severity at ages 13-14 prospectively predicted alcohol use at ages 14-15, respectively. However, among White girls, conduct problem severity at ages 11-13 prospectively predicted time-specific increases in alcohol use 1 year later, at ages 12-14, respectively. The time-specific pattern of findings for White girls in this study is strikingly similar to that reported for a primarily White (90%) sample of males followed over ages 12-18 (White et al., 1993), specifically in terms of prospective prediction at younger ages, and later emergence of concurrent associations of conduct problems and alcohol use.

Although a conduct-problem-effect model of the association between conduct problems and alcohol use was supported for both White and African American girls, ethnic differences in the timing of the associations were observed, suggesting that distinct developmental processes underlie the association in White and African American girls. Among White girls, the early prospective association between conduct problems and alcohol use may be interpreted in terms of the acquired preparedness model (Anderson et al., 2003), which proposes that parental influences (i.e., caretaker antisocial behavior) and trait disinhibition (e.g., manifest as conduct problems) influence the formation of alcohol expectancies, which, in turn, influence alcohol use. Although this study did not examine alcohol expectancies, results from this study and other analyses of PGS data (Chung et al., 2008) suggest that, among White girls, those with externalizing behaviors are at risk for early alcohol use and may benefit from early intervention to delay the onset of alcohol use.

Among African American girls, the later emergence of conduct problems as a prospective predictor of alcohol use is in accordance with the generally later onset of alcohol use in African American, compared with White, adolescents (e.g., Flory et al., 2006). The generally later onset of alcohol use in African American girls, despite somewhat greater apparent risk in terms of greater proportion living in poverty and higher prevalence of conduct problems, suggests the importance of protective factors that appear to delay the onset of alcohol use. For example, parental norms and rules regarding alcohol use, and the more limited availability of alcohol in the household, may reduce the likelihood of early alcohol use in African American girls. Of note, a study of older adolescents found that African American high school seniors had greater exposure to contextual risk factors (e.g., economic deprivation) than White seniors, whereas White seniors had greater exposure to individual (e.g., sensation seeking) and interpersonal (e.g., peer use) risks (Wallace and Muroff, 2002). Further work is needed to clarify how ethnic differences in risk and protective factors result in different developmental patterns of the time-varying association between conduct problems and alcohol use in early adolescence.

Certain study limitations warrant comment. Generaliz-ability of study results may be limited to an urban community sample of African American and White girls in one particular geographic area. In addition, because of relatively low rates of alcohol use in early adolescence, we were not able to examine frequency of alcohol use or alcohol-related problems. The relatively low level of alcohol use during early adolescence also may explain the lack of support for the alcohol-effect model, which has been supported in longitudinal studies that included coverage of late adolescence (e.g., Huang et al., 2001). Furthermore, the use of parental report of conduct problems may underestimate certain covert conduct-disordered behaviors but provides a way to reduce shared method variance with regard to report of girls' alcohol use. Self-report of alcohol use was used, which is generally a valid method for collecting substance use information (Winters et al., 2008). The study also focused on a relatively short developmental window (i.e., ages 11-15), and limited the number and type of covariates included to facilitate the interpretation of concurrent and prospective effects. Analyses by ethnicity assumed within-group homogeneity, although, in some cases, differences within ethnic groups may be as great as between-group differences (Barrera et al., 1999), and, as such, results obtained warrant replication in other samples. Similarly, the findings presented herein may not apply to all girls in our sample because different developmental trajectories may exist. For instance, some girls may have low and stable levels of conduct problems and/or alcohol use over time. Finally, there probably are several factors, not included in the analyses, that may affect the association between conduct problems and alcohol use, such as peer factors and availability of alcohol. Additionally, the conduct problem items used in the current study are limited to the DSM-IV symptoms of conduct disorder and do not include other forms of conduct problems more prevalent in females, such as relational aggression. Future studies are needed to examine the relation between a wider array of conduct problems and alcohol use in girls.

This study tested conduct-problem-effect and alcohol-effect models of the time-varying association between conduct problems and alcohol use during adolescent girls, and the moderating effect of race/ethnicity on the association. Support for conduct problems as a risk factor for alcohol use was obtained, but no support for the alcohol-effect model was observed. These findings suggest that, among girls, during early adolescence, conduct problems tend to predict alcohol use, but alcohol use appears to have no significant effect on the trajectory of girls' conduct problems over the same period. Racial/ethnic differences in the emergence of the association during early adolescence suggest early prospective effects for White girls but later prospective effects for African American girls, highlighting the need to examine processes that underlie ethnic differences in the development of conduct problems and alcohol use, as well as to examine the potential utility of culturally tailored alcohol screening and prevention efforts.

The findings have clinical importance in that they are relevant for assessment and screening. We advocate a careful assessment of substance use in girls with emerging conduct problems. Also, clinical interventions with conduct problem girls should focus on the reduction of current conduct problems, and for those conduct problem girls who are not using alcohol, the prevention of future underage drinking.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant MH056630, National Institute on Drug Abuse grant DA012237, and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants AA014357, AA017128, and AA016798. It was also funded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the FISA Foundation, and the Falk Fund. Alison E. Hipwell's effort was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant K01 MH07179.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K, Smith GT, Fischer S. Women and acquired preparedness: Personality and learning implications for alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:384–392. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Dolinsky ZS, Meyer RE, Hesselbrock M, Hofmann M, Tennen H. Types of alcoholics: Concurrent and predictive validity of some common classification schemes. British Journal of Addiction. 1992;87:1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG, Biglan A. Ethnicity, substance use, and development: Exemplars for exploring group differences and similarities. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:805–822. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerda M, Sagdeo A, Galea S. Comorbid forms of psychopathology: Key patterns and future research directions. Epidemiological Review. 2008;30:155–177. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Hipwell A, Loeber R, White HR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Ethnic differences in positive alcohol expectancies during childhood: The Pittsburgh Girls Study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:966–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Development of psychiatric comor-bidity with substance abuse in adolescents: Effects of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:298–312. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Brown T, Lynam D, Miller J, Leukefeld CR. Developmental patterns of African American and Caucasian adolescents' alcohol use. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:740–746. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine N, Carbonneau R, Vitaro F, Barker E, Tremblay R. Research review: A critical review of studies on the developmental trajectories of antisocial behavior in females. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:363–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow K, Sprafkin J. Child symptom inventories manual. New York: Checkmate Plus; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gadow K, Sprafkin J. Adolescent symptom inventories manual. New York: Checkmate Plus; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell AE, Loeber R, Southamer-Loeber M, Keenan K, White HR, Kroneman L. Characteristics of girls with early onset disruptive and antisocial behavior. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health. 2002;12:99–118. doi: 10.1002/cbm.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Davis BD, Lewis LM. The development of alcohol and other substance use: A gender study of family and peer context. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;13:22–31. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, White HR, Kosterman R, Catalano R, Hawkins JD. Developmental associations between alcohol and interpersonal aggression during adolescence. Journal of Research on Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ichiyama MA, Fairlie AM, Wood MD, Turrisi R, Francis DP, Ray AE, Stanger LA. A randomized trial of a parent-based intervention on drinking behavior among incoming college freshmen. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;16:67–76. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2008 (NIH Publication No. 09-7401) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Kasza K, Hipwell AE, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. An empirically derived approach to operationally defining conduct disorder for females. Manuscript submitted for publication; n.d.. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Rowe R, Messer J, Goodman R, Meltzer H. Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: Developmental epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:609–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho MH. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide (Version 5.2) Los Angeles, CA: Author; 1998–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers C, Moffitt T, Broadbent J, Dickson N, Hancox R, Harrington H, Caspi A. Female and male antisocial trajectories: From childhood origins to adult outcomes. Developmental Psychopathology. 2008;20:673–716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandina RJ, Labouvie EW, White HR. Potential contributions of the life span developmental approach to the study of adolescent alcohol and drug use: The Rutgers Health and Human Development Project, a working model. Journal of Drug Issues. 1984;14:253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Jacob T, True W. The role of childhood risk factors in initiation of alcohol use and progression to alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2007;102:216–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske W, Heath A, Dinwiddie S, Madden P, Bucholz K, Dunne M, Martin N. Common genetic risk factors for conduct disorder and alcohol dependence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:363–374. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Office of Applied Studies) Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings (DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343) Rockville, MD: Author; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Orlando M, Ellickson P. Patterns and correlates of binge drinking trajectories from early adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychology. 2003;22:79–87. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM, Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students, 1976–2000. Addiction. 2003;98:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Muroff JR. Preventing substance abuse among African American children and youth: Race differences in risk factor exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;22:235–261. [Google Scholar]

- White HR. Longitudinal perspective on alcohol use and aggression during adolescence. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent developments in alcoholism: Vol. 13. Alcohol and violence. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 81–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Brick J, Hansell S. A longitudinal investigation of alcohol use and aggression in adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;(Supplement No. 11):62–77. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Gorman DM. Dynamics of the drug-crime relationship. In: LaFree G, editor. Criminal Justice 2000: Vol. 1: The Nature of Crime: Continuity and Change. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Hansell S. The moderating effects of gender and hostility on the alcohol-aggression relationship. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1996;33:451–472. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington D. Developmental associations between substance use and violence. Developmental Psychopathology. 1999;11:785–803. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Xie M, Thompson W, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Psychopathology as a predictor of adolescent drug use trajectories. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:210–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters K, Stinchfield R, Bukstein O. Assessing adolescent substance use and abuse. In: Kaminer Y, Bukstein O, editors. Adolescent substance abuse: Psychiatric comorbidity and high risk behaviors. New York: Routledge Press; 2008. pp. 53–86. [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Sweeting H, West P. A longitudinal study of alcohol use and antisocial behavior in young people. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2008;43:204–214. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SE, Stallings MC, Corley RP, Krauter KS, Hewitt JK. Genetic and environmental influences on behavioral disinhibi-tion. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000;9:684–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Noll RB. Assessment of antisocial behavior: Development of an instrument. East Lansing, MI: Unpublished manuscript, Michigan State University; 1980. [Google Scholar]