Abstract

Objective:

This study examined the role of cognitive factors—such as expectancies regarding the consequences of not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking—in mediating affective and personality-based risk associated with adolescents' decisions to initiate alcohol use.

Method:

Nondrinking high school students (N = 1,268) completed confidential surveys on adolescent attitudes and behaviors related to substance use in 2 consecutive years. Self-reported alcohol use was assessed in both years, and social anxiety, depression, sensation seeking, expectancies for not drinking, and perceived peer alcohol use were assessed in the second year.

Results:

The odds of initiation were considerably lower for students with higher expectancies for not drinking, compared with those with lower expectancies. Odds of initiation rose significantly with each additional perceived peer drink reported. Both cognitive factors mediated the relationships between social anxiety, depression, sensation seeking, and alcohol-use initiation.

Conclusions:

Beliefs regarding the consequences of not drinking and perceived peer drinking play key roles in the relationship between affective and personality styles on adolescent drinking. These cognitive differences may explain varying affective risk profiles for alcohol initiation and use during adolescence, and they can provide tools for prevention efforts.

Early initiation of alcohol use is associated with multiple developmental problems, including future alcohol dependence (Grant and Dawson, 1997) and delinquency (Dawkins, 1997; Gruber et al., 1996). Many investigators have examined external influences on alcohol-use initiation, such as peer use (Curran et al., 1997; Jackson, 1997) and alcohol availability (Komro et al., 2007). However, there is considerable need to examine the influence of individual characteristics on alcohol initiation, specifically personality-based (McGue et al., 2001; Webb et al., 1991), affective (Crum et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2008), and cognitive factors (Fisher et al., 2007; Meier et al., 2007). Stable personal characteristics may influence ways that environmental cues are interpreted and used in adolescent decision making regarding drinking (Brown, 2001; Coie and Dodge, 1998). The current study explored the role that previously identified personal risk factors—such as negative affect, including social anxiety and depression, and sensation seeking—play in adolescent drinking initiation. Proximal cognitive influences, including expectancies for not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking, were examined as potential mediators of affective and personality risk for drinking onset.

Negative affect

Multiple studies have identified a relationship between negative affect and increased substance use during adolescence (Colder and Chassin, 1997; Myers et al., 2003; Shoal and Giancola, 2003; Stice et al., 1998), suggesting that individuals use substances to alleviate or cope with negative affect (Sher and Trull, 1994). Several researchers, however, have found this relationship to be negative or inconclusive (Brook et al., 1986; McGue et al., 2001; Stice et al., 1998; White et al., 1986). There also is evidence of a nonlinear relationship between negative affect and substance use, such that both abstainers and heavy users express heightened depression and anxiety in comparison with adolescents who use at moderate levels (Shedler and Block, 1990). Alternatively, both alcohol-use disorders and psychological distress or negative mood states may be in part driven by shared risk factors such as genetic risk and behavioral undercontrol (Jackson and Sher, 2003). Several recent studies have found longitudinal relationships between childhood or adolescent depression and earlier onset of alcohol use (Crum et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2008). Research examining anxiety symptoms has shown that there may be different risk and protective patterns with varying clinical presentations. Kaplow and colleagues (2001) found that generalized anxiety disorder was a risk factor for early alcohol-use initiation, whereas separation anxiety was negatively related to alcohol-use onset. In addition, social anxiety has been shown to have a somewhat protective role with regard to initiation of alcohol and other substance use (Myers et al., 2003).

Sensation seeking

Sensation seeking, or the propensity to seek new diverse experiences despite potential risks, is strongly associated with early-onset problematic alcohol use during adolescence (Arnett, 1992; Crawford et al., 2003; D'Amico et al., 2001; Hittner and Swickert, 2006). Of note, heightened levels of sensation seeking occur during this developmental period, relative to any other time in the life course (Zuckerman and Neeb, 1980). Individuals with a higher drive toward sensation seeking often choose friends and social settings that include others with similar activation levels and interest in novelty (Donohew et al., 1999; Yanovitzky, 2005, 2006), such as alcohol and drug involvement. Such social contexts and models may increase the likelihood of early initiation of alcohol use. These relationships can both directly and indirectly reinforce continued risk-taking behaviors by increasing access to and social opportunities for risk taking (Schulen-berg and Maggs, 2002). Risk-taking peers also may provide an approving and supportive social network of people who encourage these behaviors and whose support may reduce negative feelings, such as fear or apprehension regarding potential adverse consequences of substance involvement.

Proximal cognitive influences

Stable intrapersonal characteristics predispose aspects of information processing via self-selection of environments (Caspi and Roberts, 2001) and preparedness to respond to certain stimuli (Smith and Anderson, 2001) that ultimately determine alcohol-use decisions (e.g., Brown, 2001). Both negative affect and sensation-seeking preferences may influence drinking onset by impacting (a) an individual's choice of activities, peers, and contexts, (b) differential attention and interpretation of alcohol-relevant materials in those contexts (Goldman et al., 1999), (c) anticipation of the outcome associated with drinking or not drinking, and (d) distinctive reward values experienced for each outcome (McCarthy et al., 2001). Teens higher in sensation seeking may be more likely to attend to and encode positive information about alcohol use from media outlets or peers' conversations and be less responsive to information about delayed negative outcomes of use (Smith and Anderson, 2001; Zuckerman, 1994). Because of this, they may be more likely to develop negative beliefs about the consequences of abstinence and to overestimate alcohol use of others their age.

The relationship between negative affect and alcohol use may be less straightforward. Some individuals may worry about and focus on potential negative effects of alcohol use or have less exposure to alcohol in social contexts because of isolative tendencies, thus decreasing their alcohol-initiation risk. Conversely, others may be motivated by the desire to affiliate with peers or experience positive alcohol effects, especially if their own positive experiences have been limited by their affective style (Myers et al., 2003). These divergent motivations may lead to contrasting cognitions about peer behavior and the consequences of drinking versus abstaining from alcohol use.

Expectancies for not drinking.

Alcohol-use expectancies play a strong mediational role in the relationships between personality, affect, and alcohol use (Anderson et al., 2005; Johnson and Gurin, 1994; Kassel et al., 2000). Recent research on expectancies regarding the outcomes associated with not drinking alcohol has shown expectancies for not drinking to be related to changes in drinking, including efforts to decrease or desist in drinking behavior (Metrik et al., 2004). Expectancies about both drinking and abstention are likely to have considerable impact on adolescents' decisions to initiate alcohol use. Specifically, at stages of attention to stimuli and evaluation of consequences, youth likely take into account the expected effects drinking will have on their friendships, school performance, and family responses. Although expectancies of drinking outcomes have been identified as robust predictors of alcohol use during adolescence, no study has examined the impact of expectancies for not drinking on initiation.

Perceived peer drinking.

Perceptions of the frequency and intensity with which peers drink is another influential factor on adolescent drinking decisions, especially in early adolescence (Scheier and Botvin, 1997; Wood et al., 2001). Consistent with the theory that perceived norms play a causal role in drinking initiation, these beliefs have been shown to predict subsequent initiation of alcohol and marijuana (D'Amico and McCarthy, 2006). Although perceptions about how much others are drinking are partially affected by what adolescents see or hear from friends and classmates, teens' estimates of the rates of alcohol use among their age group are typically much higher than the amount of drinking their peers report (Jacobs and Johnston, 2005; Monreal et al., 2009; Perkins, 2002; Schulte et al., in press). For high-risk youth, these misperceptions may be a direct reflection of the effects that personality and affective differences have on interpretation of external cues and information. They also may be influenced by demographic differences, such as age, gender, and ethnicity. Ultimately such perceptions may influence how willing adolescents are to join in with others in drinking and related activities.

Current study

The current study aimed to examine the roles of affective, personality, and cognitive risk factors in decisions to initiate alcohol use. We examined drinking onset by selecting teens who reported no lifetime alcohol use at baseline and assessing them after 1 year to evaluate differences between those who maintained abstinence and others who began to drink alcohol. We explored the influence of expectancies for not drinking on alcohol-use initiation, as well as the mediational role of expectancies for not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking in the relationships between the prediction of personality and affective risk on drinking initiation. We hypothesized that expectancies for not drinking would strongly differentiate individuals who initiate alcohol use from youth who maintain abstinence. Because of differences found in the literature regarding types of negative affect (e.g., Crum et al., 2008; Myers et al., 2003), we hypothesized that depression would be associated with increased risk for alcohol initiation, whereas social anxiety would be associated with decreased risk for alcohol-use initiation. Additionally, we hypothesized that expectancies for not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking would partially mediate the relationships between sensation seeking, negative affect, and the initiation of alcohol use. Because of differences in age of progression through puberty (Tanner and Davies, 1985), personality (i.e., Romer and Hennessy, 2007), affective styles (i.e., Nolen-Hoeksema and Girgus, 1994), drinking behaviors and contexts by gender (e.g., Schulte et al., in press), we explored these hypotheses separately for girls and boys.

Method

Sample

The current assessments were conducted with 9th through 12th graders in fall 2000 and fall 2001 as part of a confidential survey on adolescent attitudes and behaviors related to alcohol and drug use in metropolitan San Diego County, CA. As with other large-scale studies (D'Amico et al., 2001; Stice et al., 1998), invariant demographic and personal characteristics (e.g., month of birth, number of older biological siblings, middle school attended) were used to create a unique identifier for each participant, which was then used to match two assessment time points. Using this procedure, 75% of 10th-12th graders' data collected in mid-October 2001 were matched to data collected in mid-October 2000 (n = 2,967) using unique identifiers. Of this group, 103 participants were dropped from analyses who endorsed use of a fictitious substance or inconsistent reporting of alcohol use (e.g., reporting no lifetime use and some past-month alcohol use). Forty-four percent of the remaining sample of matched participants reported no lifetime alcohol use at Time 1 (n = 1,268). Of these students, 53% were male; 63.1% reported that they were White, 6.7% Hispanic, 14.0% Asian, 2.1% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 1.43 % African American; 12.7 % identified themselves as “other” or of mixed ethnic origin. Forty-four percent were in 9th grade, 35% in 10th grade, and 21% in 11th grade at Time 1. Alcohol use was assessed at both time points, and all other variables were assessed at Time 2.

Measures

Depression.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (Radloff, 1977) has been validated in both general and psychiatric populations, as well as with adolescents (Radloff, 1991). Participants completed one item from each of three subscales: depressed affect (“How often in the past week did you feel depressed?”), somatic (“How often in the past week did you feel bothered and restless?”), and interpersonal (“How often in the past week did you feel people disliked you?”). Together the results demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = .77). To ease the interpretation of results, we rescaled the scores by dividing the score by the range to vary from 0 (low depression endorsement) to 1 (high depression endorsement).

Social anxiety.

To assess the amount of social anxiety expressed by the teens in this sample, we chose five items from the Social Avoidance and Distress-New Scale of the Social Anxiety Scales for Adolescence (La Greca, 1998; e.g., “How true for you is the following statement: I get nervous when I meet new people.”). These items demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = .87) in the current sample. We re-scaled scores by dividing the score by the range to vary from 0 (low social-anxiety endorsement) to 1 (high social-anxiety endorsement).

Sensation seeking.

Four items from the Fun-Seeking Scale from the Behavioral Inhibition/Activation System Scales (Carver and White, 1994) examined adolescents' level of sensation seeking (i.e., “Agree or disagree: I crave excitement and new sensations.”). We used a 5-point Likert-scale response style, with values ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Internal consistency was high in this sample (α = .85). We rescaled scores by dividing the score by the range to vary from 0 (low sensation-seeking endorsement) to 1 (high sensation-seeking endorsement).

Expectancies for not drinking.

Seventeen items assessed students' beliefs about life in general (11 items) and social consequences of not using alcohol or reducing alcohol use (6 items) (Metrik et al., 2004; e.g., “How would the following change if someone cut down or stopped drinking: Fitting in with others.”). We recorded their responses in a 5-point forced-choice format (0 = a lot worse, 1 = worse, 2 = no difference, 3 = better, 4 = a lot better). Two scales, global and peer social, demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .90 and .95, respectively). Because of a high level of collinearity (r = .75), we combined these scales in the current study. We rescaled scores by dividing the score by the range to vary from 0 (negative expectancies for not drinking endorsement) to 1 (positive expectancies for not drinking endorsement).

Perceived peer alcohol use.

Students estimated the intensity of drinking behavior among their same-grade peers. We assessed quantity estimates of peer use by the item, “When students in your grade drink alcohol, on average, how many drinks do you think they have?” Responses ranged from 0 to 15 drinks per occasion (Fromme and Ruela, 1994).

Alcohol-use variables.

We used items from well-established measures, including the Monitoring the Future Study (Johnston and O'Malley, 1999) and the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (Brown et al., 1998), to assess lifetime (7-point scale, never to more than 100 times) and current (past 30 days; 5-point scale, never to 20 or more times) alcohol use. Students also reported their average number of drinks consumed per drinking occasion in the past month.

Procedure

With approval from the University of California, San Diego Research Protection Program and each high school, passive consent was used. Letters describing the survey were mailed to parents, and they were given the option to request that their child not participate by returning a marked form. Less than 1% of parents declined participation for their child. Classrooms at each school were surveyed by trained research proctors during a 1-week period when typical drinking and absences were expected. After verbally reviewing written assent statements, all assenting youth (94%-95%; ages 14-18) with parental consent completed the survey. Surveys were monitored by and returned to the independent proctor after 45 minutes.

Analyses

Several approaches were used to assess hypothesized mediation pathways. However, the results were not reported using the “causal-step” approach outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) because of recent clarification in the literature that not all steps included in that approach are necessary when testing for mediation (MacKinnon et al., 2007), nor do they improve interpretability as compared with other approaches. Both Kenny (2008) and MacKinnon (2008) have noted that establishing the relationship between the independent variable and the mediator (Path A) and then the mediator and the outcome variable (Path B) is sufficient to achieve the evidentiary strength of the causal step approach, without an unnecessary loss of power (MacKinnon et al., 2002). We used and reported ordinary least squares regressions to assess Path A and logistic regression to assess Path B.

We also estimated single-mediation models, which tested the significance of the model overall and provided an estimate of the size of the mediated effect, under the assumption that the model had been correctly specified. The size and significance of the mediated effect for each proposed mediator was first estimated in separate single-mediation models. The mediated effects modeled were evaluated with a Z test using Sobel standard errors (Sobel, 1982) and supplemented with bootstrap-corrected confidence intervals (Preacher and Hayes, 2004). These mediated effects also were assessed in a multiple-mediation model, which allowed for conditional effects of the mediators to be estimated (MacKinnon, 2000; Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Both specific and total effects are reported. As defined by Bollen (1987), specific indirect effects are the estimate of the mediation transmitted through each particular mediator after adjusting for the other medi-ational pathways. The total indirect effect gauges the joint mediated effect through all of the specified mediators in the model.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Approximately 39% of the 9th- to 1 1th-grade students who did not endorse lifetime alcohol use at Time 1 (n = 1,268) reported that they had initiated alcohol use by Time 2 (in 10th-12th grade). Among these newly initiated drinkers, female and male participants reported consuming an average of three to four drinks per occasion, respectively; amounts equivalent to the average consumption of the full sample of high school drinkers, regardless of year of initiation. Male students had slightly higher perceptions of how many average drinks their peers would have per drinking occasion than female students (Table 1). These perceptions were higher than the average self-reported number of drinks per drinking episode in the general sample of high school drinkers for both males and females (males: M = 4.11, SD = 4.06; females: M = 3.06, SD= 3.26).

Table 1.

Description of sensation seeking, affect, and cognitive factors at Time 2 among male and female high school students with no reported lifetime alcohol experience at Time 1 and correlations between them for male adolescents (below the diagonal) and female adolescents (above the diagonal)

| Male (n = 677) |

Female (n = 591) |

Correlations |

|||||||

| Variable | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1. Nondrinking expect | 0.71 | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.18 | — | −.10* | .01 | −.16** | −.15* |

| 2. Perceived peer use | 5.51 | 3.38 | 4.92 | 2.52 | −.05* | — | −.04 | .13* | .07* |

| 3. Social anxiety | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.22 | .12* | −.06* | — | .26** | −.19** |

| 4. Depression | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.24 | −.03 | .14* | .29** | — | .07* |

| 5. Sensation seeking | 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.25 | −.18** | .20* | −.20** | −.09* | — |

p <.01;

p <.001.

Items related to depression were endorsed at a lower rate than items related to social anxiety and sensation seeking for both male and female students, and there was considerable variation among all three of these risk factors (Table 1). These scores did not differ significantly by gender, although girls had slightly higher levels of depression than boys. On average, adolescents endorsed relatively positive expectancies for not drinking. When measured at Time 2, expectancies were lower among initiators (male: M= 0.59, SD= 0.22; female: M= 0.64, SD = 0.16) when compared with abstainers (male: M= 0.75, SD= 0.19; female: M= 0.75, SD = 0.17).

In correlational analyses (Table 1) assessing the relationships between predictor, mediator, and outcome variables, expectancies for not drinking demonstrated a small, significant positive relationship with social anxiety in males and negative association with depression in females. Expectancies for not drinking also had a modest negative link with sensation seeking and perceptions of peer drinking for both genders. Perceptions of peer drinking was connected with depression and sensation seeking but was negatively related to expectancies for not drinking and social anxiety (males only). Although social anxiety and depression were moderately correlated with one another, they demonstrated opposite relationships with other variables of interest.

Putative mediators

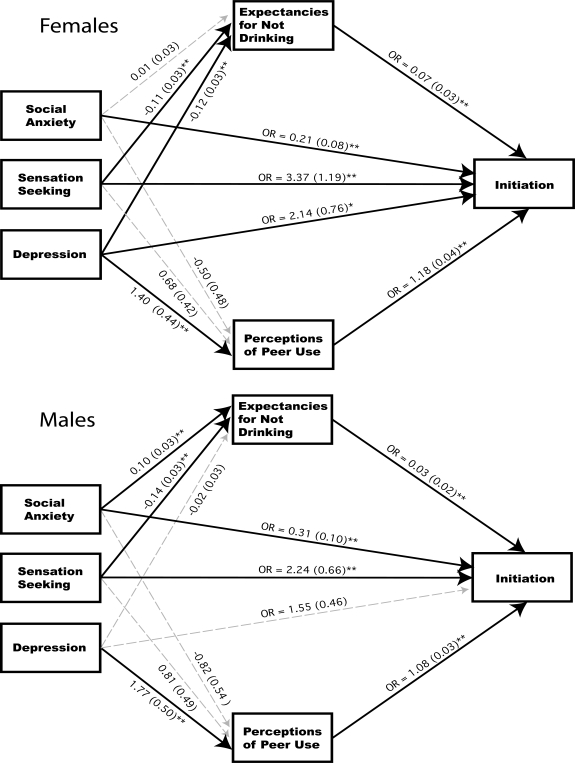

The strength of the relationships between risk factors and hypothesized cognitive mediators (Figure 1) were estimated using regression analyses. For male students, sensation seeking was negatively related to expectancies for not drinking, but there was evidence of a positive relationship between social anxiety and expectancies for not drinking. For females, sensation seeking and depression were found to be negatively related to expectancies for not drinking, but no significant relationship was found for social anxiety. The only independent variable significantly related to perceptions of peer drinking for both male and female students was depression.

Figure 1.

Putative mediational paths of expectancies of not drinking and perceived peer alcohol use between social anxiety, depression, sensation seeking, and initiation of alcohol use for females (upper panel) and males (lower panel). Notes: Links contain the regression coefficients and standard errors; the central path is the direct effect; scores for sensation seeking and nondrinking expectancies fall on a scale from 0 to 1, whereas perceptions of peer consumption represents number of drinks. OR = odds ratio.

*p < 05; **p < 01.

We also found evidence to support a relationship between both cognitive mediators and the outcome variable, initiation of alcohol use (Figure 1). Both expectancies for not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking were significantly related to the initiation of drinking behavior in male and female students, but this effect was stronger for expectancies for not drinking than perceptions of peer drinking. The odds of initiation were 93% and 97% lower for students with the high expected consequences of not drinking compared with nondrinking students with low expectancies, for females and males, respectively. Among males, the odds of initiation rose by 8% for each additional drink reported for peer perceptions. Among females, the odds rose by 18% for each perceived drink.

Single-mediation models

Next, we examined the extent to which each cognitive factor individually mediated the relationship between affect or personality and drinking in the hypothesized mediational pathways (Table 2). Models describing the pathways from social anxiety and sensation seeking to alcohol initiation as mediated by expectancies for not drinking were significant for males (13% reduction in odds of initiation and 22% increased odds of initiation, respectively), and sensation seeking and depression were significant for females (22% and 26% increased odds of initiation, respectively). Models with perceptions of peer drinking mediating the relationship between depression and alcohol initiation were significant for both males and females (9% and 15% increased odds of initiation, respectively), but perceptions of peer drinking did not appear to mediate the risk for alcohol initiation related to either sensation seeking or social anxiety. The bootstrap results were similar for all single-mediation models (Table 2).

Table 2.

Single and multiple mediation coefficients of the indirect relationship between sensation seeking, social anxiety, and depression and initiation of alcohol use

| Single-mediation models |

Multiple-mediation models |

|||||||||||||||

| Male Bootstrap CIa |

Female Bootstrap CIa |

Male Bootstrap CIa |

Female Bootstrap CIa |

|||||||||||||

| Indirect effects | OR | SE | Ll | Ul | OR | SE | Ll | Ul | OR | SE | Ll | Ul | OR | SE | Ll | Ul |

| Social anxiety | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.81** | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.94 | 0.79* | 0.08 | 0.64 | 0.97 |

| END | 0 87* | 0 05 | 0 78 | 0 96 | 0.98 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 1.14 | 0.87* | 0.05 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.88 | 0.07 | 0.76 | 1.03 |

| PPD | 0 96 | 0 03 | 0.91 | 1 02 | 0 95 | 0 .05 | 0 86 | 1 05 | 0.92 | 0 04 | 0.85 | 1 01 | 0.89 | 0 .06 | 0 78 | 1 02 |

| Sensation seeking | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.25* | 0.09 | 1.07 | 1.45 | 1.51* | 0.18 | 1.21 | 1.90 |

| END | 1 22** | 0 07 | 1.10 | 1.36 | 1.22* | 0.08 | 1.07 | 1.39 | 1.11 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 1.24 | 1.27* | 0.11 | 1.07 | 1.51 |

| PPD | 1.04 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 0.05 | 0.97 | 1.18 | 1.12* | 0.05 | 1.02 | 1.23 | 1.19* | 0.08 | 1.04 | 1.36 |

| Depression | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.26* | 0.09 | 1.09 | 1.45 | 1.27* | 0.12 | 1.06* | 1.52 |

| END | 1.03 | 0.05 | 0.94 | 1.13 | 1.26* | 0.10 | 1.09 | 1.47 | 1.21* | 0.08 | 1.07 | 1.37 | 1.22* | 0.09 | 1.05 | 1.41 |

| PPD | 1.09* | 0.04 | 1.01 | 1.18 | 1.15* | 0.06 | 1.03 | 1.28 | 1.04 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 0.05 | 0.95 | 1.15 |

Notes: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; Ll = lower limit; Ul = upper limit; END = expectations for not drinking; PPD = perceptions of peer drinking.

Bootstrap bias corrected and accelerated CIs (5,000 resamples).

p < .05;

p < .001, based on Ztests and Sobel standard errors.

Multiple-mediation models

We next examined the data with a multiple-mediation model (MacKinnon, 2008) to better understand the effect of both expectancies for not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking in the context of each other (Table 2). The specific effects of social anxiety, depression, or sensation seeking and alcohol-use initiation through expectancies for not drinking (when controlling for mediation through perceptions of peer drinking) and perceptions of peer drinking (when controlling for mediation through expectancies for not drinking) were all significant. In the single-mediation models, expectancies for not drinking mediated reduced risk associated with social anxiety for males only (13% decreased odds of initiation), but when perceptions of peer drinking were included as a second mediator in the multiple-mediator model, joint mediation of expected consequences of not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking was moderately significant for females (21% decreased odds of initiation). Interpretation of this aspect of the model is difficult because the two specific indirect effects are of similar magnitude and nonsignificant. The indirect effects for sensation-seeking risk through expectancies for not drinking were significant and of similar magnitude, and the indirect effects for perceptions of peer drinking were nonsignificant for both genders. In the multiple-mediation model the significance of perceptions of peer drinking changed such that, when adjusted for expectancies for not drinking, the specific indirect effect of perceptions of peer drinking became significant.

In the single-mediation models, the indirect effects from depression risk through expectancies for not drinking were significant for girls but not for boys (26% increased odds of initiation). Although perceptions of peer drinking were significant in the single-mediation models for both boys and girls, in the multiple-mediation models the specific indirect effects were attenuated and nonsignificant for both sexes (Table 2). The pattern for expectancies for not drinking was more complex. In the multiple-mediation model for boys, the indirect effect of expectancies for not drinking increased by 16 points as compared with the single-mediation model and became significant.

Discussion

The current study sought to examine the utility of expectancies for not drinking or beliefs about the consequences of not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking in understanding decisions to initiate alcohol involvement. Both expectancies for not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking were associated with initiation of drinking behavior in male and female students at Time 2, and this effect was particularly strong for expectancies for not drinking. There has been consistent support for the powerful predictive value of alcohol-use expectancies for drinking initiation, intensity, and problems related to drinking (e.g., Barnow et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2001; Meier et al., 2007; Smith et al., 1995), and the current study extends this impact to adolescents' beliefs about the consequences of not drinking. Recent research has demonstrated that expectancies for not drinking also are related to the intensity of drinking (Bekman et al., in press) and attempts to quit or reduce drinking (Metrik et al., 2004), and they partially mediate the relationship between sensation seeking and drinking intensity (Bekman et al., in press). The current study expanded these findings to include relationships with the onset of drinking behavior and mediation of affective and personality variables associated with alcohol-use initiation.

As hypothesized, whereas endorsement of depression symptoms and sensation-seeking characteristics were related to increased risk for the initiation of alcohol use, social anxiety was associated with reduced risk of alcohol-use onset. This finding corresponds with research demonstrating that, although symptoms of anxiety and depression both reflect negative affective states and frequently co-occur, they may have distinct relationships to alcohol and other substances, especially during adolescence. Although depression has been shown to have a strong impact on enhanced substance-related risk, even when assessed in childhood (e.g., Wu et al., 2008), anxiety tends to have a more complex relationship with regard to risky alcohol use. Because of the diverse presentations of anxiety, some conditions (such as posttrau-matic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder) tend to relate to increased risk for drinking, whereas others (such as social anxiety, separation anxiety, or phobias) may actually serve a more protective role during adolescence (e.g., Kaplow et al., 2001). We hypothesized that this outcome would be largely because of fear of negative consequences from alcohol use, specifically related to possible strain on family and peer relationships, as well as on health and school performance.

When we examined the potential mediational role of expectancies for not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking, we found that they play a significant role in reduced risk of initiation associated with social anxiety. This finding may be the result of cognitive rumination about potential negative outcomes typically associated with anxiety (e.g., fears of getting in trouble or negative health outcomes; Crick and Dodge, 1994) or benefits of staying sober (e.g., staying alert, feeling in control of one's behavior). Depression risk was mediated primarily by expectancies for not drinking and shared variance with perceptions of peer drinking, indicating that adolescents endorsing depression symptoms may be affected by more negative expectancies for not drinking relevant to peer relationships, such as trouble fitting in with others. We found evidence to support a relationship between social anxiety and more positive expectancies for not drinking for boys but were unable to confirm the same relationship for girls. Conversely, girls evidenced a relationship between depression symptoms and more negative expectancies for not drinking, but this support was not found for boys. Despite these differences in significance, mediational relationships for both expectancies for not drinking and perceptions of peer drinking were equivalent in magnitude between males and females, indicating that these mediators may be similarly important for both genders.

Sensation seeking was strongly associated with alcohol initiation, especially for girls, and also was related to negative expectancies for not drinking. Although, in single-mediation models, perceptions of peer drinking did not appear to explain a significant portion of the risk for alcohol initiation related to sensation seeking, in the multiple-mediation models, this risk was best explained by perceptions of peer drinking and the combined variance associated with these perceptions, and expectancies for not drinking. Because adolescents higher in sensation seeking tend to spend time with peers who have similar characteristics (e.g., Donohew et al., 1999), they are likely to affiliate with deviant peer groups and be exposed to greater levels of alcohol use. These activities may play a larger role in bonding and friendships within these peer groups, and thus the perceived consequences of not partaking in drinking or drug-use activities on friendship and social identity would be key influences in decisions to initiate alcohol use.

Cognitive factors such as alcohol use expectancies, expectancies for not drinking, and perceptions of peer drinking have proven to be quite valuable in prevention and intervention efforts because they are malleable (e.g., Darkes and Goldman, 1993; Schulte et al., in press). Additional information regarding the impact of affective and temperamental differences on the interpretation and relative importance of potential consequences of alcohol use versus abstention from use—as well as perceived normative adolescent behavior— provides new understanding of what approaches might work best in different teen populations. Although the importance of peer relationships is elevated for most adolescents, specific affective and personality characteristics may impact the degree to which these peer relationships influence decisions to drink or to abstain relative to other competing value domains, such as school, family, or health. These characteristics also affect teen's views on whether alcohol involvement or avoidance of alcohol will be positive or negative, and this information can be used to tailor prevention to the needs of adolescents at risk for alcohol-related problems. For example, given the evidence that adolescents experiencing social anxiety may initiate alcohol use later than other teens and that expectancies for not drinking play a role in this delayed onset, treatment of social anxiety during adolescence could include a focus on strengthening negative alcohol-use expectancies and positive expectancies for not drinking to potentially delay the onset of alcohol use and reduce the risk of problematic alcohol use that frequently co-occurs with social anxiety in adults.

Limitations and future directions

A key advantage for the current examination was that we were able to identify participants who had recently initiated alcohol use (within a 1-year period). However, because all predictor and mediator variables were assessed at Time 2, we were not able to provide evidence of the temporal sequence for the hypothesized mediational processes. Although some of these were measures of traits that are relatively stable over time (i.e., negative affect and sensation seeking), it is possible that these could have been influenced by alcohol use. Additionally, participants' expectancies for not drinking or how much peers may be drinking may have been affected by their own experience with alcohol rather than having preceded their alcohol-use initiation. To fully investigate causality with regard to these mediational pathways, future studies would be needed that assess mediator and outcome variables at several time points across adolescent development to strengthen our understanding of the roles that cognitive factors play before and after alcohol initiation. Further information may be gained by experimentally modifying cognitions and then observing changes in drinking/abstinence behaviors.

Additionally, data in this and other studies point to disparities in the relationships between negative affect and alcohol use (a) at different life stages and (b) based on the type of negative affect being studied (e.g., depression, anxiety, and anger). Specifically, different types of anxiety symptoms with high rates of comorbidity with alcohol-use disorders in adulthood can be either a risk factor or a protective factor during adolescence. This study was able to examine only a subset of these types of negative affect, and only a small number of items were used to assess symptoms of depression and social anxiety. Further research is needed to examine the trajectories of diverse affective styles as adolescents mature, the function of cognitive factors in the development of co-morbid alcohol problems, and the role of social involvement or isolation as moderators of these relationships (e.g., Hus-song and Chassin, 1994).

Similar to alcohol-use expectancies, beliefs regarding the consequences of not drinking alcohol may be an important component in understanding how adolescents make decisions about the initiation of alcohol use. These beliefs, as well as perceptions of peer alcohol use, play a key role relevant to the impact of affective and personality styles on drinking, as adolescents navigate potentially conflicting value domains, such as peer acceptance, school performance, and family relationships. Differences in these cognitions also explain why diverse types of negative affect have varying risk profiles for alcohol initiation among adolescent boys and girls and may provide additional tools for prevention and intervention efforts. Further research exploring expectancies for not drinking and their relationship to other key cognitive factors, such as drinking motives or alcohol-use expectancies, will enhance our understanding of how these cognitions act in concert with others to shape adolescent drinking decisions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the programs, staff, and participants in this study. Special thanks go to Ryan Trim for his suggestions on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants and fellowships R01 AA12171 -09 (Sandra A. Brown, principal investigator), R37 AA07033-23 (Sandra A. Brown, principal investigator), and T32 AA013525 (Nicole M. Bekman, fellow, and Edward P. Riley, principal investigator).

References

- Anderson KG, Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Fischer SF, Fister S, Grodin D, Hill KK. Elementary school drinking: The role of temperament and learning. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:21–27. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. Reckless behavior in adolescence: A developmental perspective. Developmental Review. 1992;12:339–373. [Google Scholar]

- Barnow S, Schultz G, Lucht M, Ulrich I, Preuss U, Freyberger H. Do alcohol expectancies and peer delinquency/substance use mediate the relationship between impulsivity and drinking behaviour in adolescence? Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2004;39:213–219. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekman NM, Cummins K, Brown SA. The influence of alcohol-related cognitions on personality-based risk for alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. in press [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Total, direct, and indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1987;17:37–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Gordon AS, Nomura C, Brook DW. Onset of adolescent drinking: A longitudinal study of intraper-sonal and interpersonal antecedents. Advances in Alcohol and Substance Abuse. 1986;5:91–110. doi: 10.1300/J251v05n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA. Facilitating change for adolescent alcohol problems: A multiple options approach. In: Wagner EF, Waldron HB, editors. Innovations in adolescent substance abuse interventions. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Pergamon/Elsevier Science; 2001. pp. 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, D'Amico EJ, McCarthy DM, Tapert SF. Four-year outcomes from adolescent alcohol and drug treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:381–388. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Myers MG, Lippke L, Tapert SF, Stewart DG, Vik PW. Psychometric evaluation of the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR): A measure of adolescent alcohol and drug involvement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:427–438. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW. Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry. 2001;12:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology, 5th ed.: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 779–862. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Chassin L. Affectivity and impulsivity: Temperament risk for adolescent alcohol involvement. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AM, Pentz MA, Chou C, Li C, Dwyer JH. Parallel developmental trajectories of sensation seeking and regular substance use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:179–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Storr CL, Ialongo N, Anthony JC. Is depressed mood in childhood associated with an increased risk for initiation of alcohol use during early adolescence? Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:24–40. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Stice E, Chassin L. The relation between adolescent alcohol use and peer alcohol use: A longitudinal random coefficients model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:130–140. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, McCarthy DM. Escalation and initiation of younger adolescents' substance use: The impact of perceived peer use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Metrik J, McCarthy DM, Frissell KC, Applebaum M, Brown SA. Progression into and out of binge drinking among high school students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, Goldman MS. Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: Experimental evidence for a mediational process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:344–353. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins MP. Drug use and violent crime among adolescents. Adolescence. 1997;32:395–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohew RL, Hoyle RH, Clayton RR, Skinner WF, Colon SE, Rice RE. Sensation seeking and drug use by adolescents and their friends: Models for marijuana and alcohol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:622–631. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LB, Miles IW, Austin SB, Camargo CA, Colditz GA. Predictors of initiation of alcohol use among US adolescents: Findings from a prospective cohort study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:959–966. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.10.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Ruela A. Mediators and moderators of young adults' drinking. Addiction. 1994;89:63–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Darkes J, Del Boca FK. Expectancy mediation of biopsychosocial risk for alcohol use and alcoholism. In: Kirsch I, editor. How expectancies shape experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber E, DiClemente RJ, Anderson MM, Lodico M. Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25:293–300. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hittner JB, Swickert R. Sensation seeking and alcohol use: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1383–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Chassin L. The stress-negative affect model of adolescent alcohol use: Disaggregating negative affect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:707–718. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. Initial and experimental stages of tobacco and alcohol use during late childhood: Relation to peer, parent, and personal risk factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Alcohol use disorders and psychological distress: A prospective state-trait analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:599–613. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JE, Johnston KE. “Everyone else is doing it”: Relations between bias in base-rate estimates and involvement in deviant behaviors. In: Jacobs JE, Klaczynski PA, editors. The development of judgment and decision making in children and adolescents. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PB, Gurin G. Negative affect, alcohol expectancies and alcohol-related problems. Addiction. 1994;89:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM. National survey results on drug use from the Monitoring the Future study, 1975-1998. Volume I: Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 99-4660) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Angold A, Costello EJ. The prospective relation between dimensions of anxiety and the initiation of adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:316–326. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Reflections on mediation. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina MM, Tobler AL, Bonds JR, Muller KE. Effects of home access and availability of alcohol on young adolescents' alcohol use. Addiction. 2007;102:1597–1608. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM. Manual for the social anxiety scales for children and adolescents. Miami, FL: Author; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Contrasts in multiple mediator models. In: Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, editors. Multivariate applications in substance use research: New methods for new questions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis (Multivariate Applications Series) Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Kroll LS, Smith GT. Integrating disin-hibition and learning risk for alcohol use. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:389–398. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink: I. Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier MH, Slutske WS, Arndt S, Cadoret RJ. Positive alcohol expectancies partially mediate the relation between delinquent behavior and alcohol use: Generalizability across age, sex, and race in a cohort of 85,000 Iowa schoolchildren. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:25–34. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrik J, McCarthy DM, Frissell KC, MacPherson L, Brown SA. Adolescent alcohol reduction and cessation expectancies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:217–226. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monreal TK, Kia-Keating M, Schulte MT, Brown SA. Manuscript submitted for publication; 2009. Perceived norms of adolescent drinking in a brief high school secondary intervention program. [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Aarons GA, Tomlinson K, Stein MB. Social anxiety, negative affectivity, and substance use among high school students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:277–283. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:424–443. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Supplement No. 14):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments and Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer D, Hennessy M. A biosocial-affect model of adolescent sensation seeking: The role of affect evaluation and peer-group influence in adolescent drug use. Prevention Science. 2007;8:89–101. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier L, Botvin G. Expectancies as mediators of the effects of social influences and alcohol knowledge on adolescent alcohol use: A prospective analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maggs JL. A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Supplement No. 14):54–70. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte MT, Monreal TK, Kia-Keating M, Brown SA. Influencing adolescent social perceptions of alcohol use to facilitate change through a school-based intervention. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. in press [Google Scholar]

- Shedler J, Block J. Adolescent drug use and psychological health: A longitudinal inquiry. American Psychologist. 1990;45:612–630. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: Alcoholism and antisocial personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoal GD, Giancola PR. Negative affectivity and drug use in adolescent boys: Moderating and mediating mechanisms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:221–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Anderson KG. Personality and learning factors combine to create risk for adolescent problem drinking. In: Monti P, Colby S, O'Leary T, editors. Adolescents, alcohol, and substance abuse. New York: Guilford; 2001. pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Goldman MS, Greenbaum PE, Christiansen BA. Expectancy for social facilitation from drinking: The divergent paths of high-expectancy and low-expectancy adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:32–40. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Myers MG, Brown SA. A longitudinal grouping analysis of adolescent substance use escalation and de-escalation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12:14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner J, Davies PS. Clinical longitudinal standards for height and height velocity for North American children. Journal of Pediatrics. 1985;107:317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JA, Baer PE, McLaughlin RJ, McKelvey RS, Caid CD. Risk factors and their relation to initiation of alcohol use among early adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1991;30:563–568. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Johnson V, Horwitz A. An application of three deviance theories to adolescent substance use. International Journal of the Addictions. 1986;21:347–366. doi: 10.3109/10826088609074839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Read JP, Palfai TP, Stevenson JF. Social influence processes and college student drinking: The mediational role of alcohol outcome expectancies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:32–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Hoven CW, Okezie N, Fuller CJ, Cohen P. Alcohol abuse and depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;17:51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitzky I. Sensation seeking and adolescent drug use: The mediating role of association with deviant peers and pro-drug discussions. Health Communication. 2005;17:67–89. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1701_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitzky I. Sensation seeking and alcohol use by college students: Examining multiple pathways of effects. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11:269–280. doi: 10.1080/10810730600613856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Neeb M. Demographic influences in sensation seeking and expressions of sensation seeking in religion, smoking and driving habits. Personality and Individual Differences. 1980;1:197–206. [Google Scholar]