Abstract

Background:

Tobacco use is a major public health problem globally. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), tobacco is the second most important cause of death in the world. It is currently estimated to be responsible for about 5 million deaths each year worldwide. In India, it is responsible for over 8 lakh deaths every year.

Objective:

To estimate the prevalence of tobacco use among power loom workers in Mau Aima Town, District Allahabad, UP.

Materials and Methods:

Five hundred power loom workers were randomly chosen. Out of them 448 workers were interviewed through a questionnaire survey during May-June 2007. Data on demographics, education, and type of work were collected along with details regarding tobacco use and smoking status, duration of the habit, and daily consumption. Prevalence of tobacco chewing and/or bidi and cigarette smoking, and their sociodemographic correlates, were examined.

Results:

The overall prevalence of tobacco use was 85.9%; the prevalence of smoking and tobacco chewing were 62.28% and 66.07%, respectively. Statistical analysis showed that smoking is more common in the elderly, while chewing gutka (a type of chewing tobacco) is popular among the younger age-groups.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of tobacco use among power loom workers is very high compared to that in general population. Immediate intervention programs are warranted to reduce the future burden of tobacco-related morbidity among these workers who are already exposed to the highly polluted environment in power loom factories.

Keywords: Tobacco chewing, tobacco smoking, power loom workers

Introduction

Tobacco use is one of the important preventable causes of death(1) and a leading public health problem all over the world.(2) According to the WHO, tobacco is the second major cause of death worldwide and is currently responsible for about 5 million deaths each year.(3) This figure is expected to rise to about 8.4 million by the year 2020, with 70% of those deaths occurring in developing countries.(4) Eighty-two percent of the world's 1.1 billion smokers now reside in low- and middle-income countries where, in contrast to the declining consumption in high-income countries, tobacco consumption is on the rise.(5) In India, tobacco use is estimated to cause 800,000 deaths annually.(6) The WHO predicts that tobacco deaths in India may exceed 1.5 million annually by 2020.(7)

Tobacco use is harmful and addictive. All forms of tobacco cause fatal and disabling health problems throughout life. Scientific evidence has linked tobacco use with the development of more than 25 diseases. Smoking tobacco is the major cause of lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), peripheral vascular disease, and various throat and mouth cancers. Tobacco smoking is a known cause of stroke, coronary heart disease, bladder cancer, aortic aneurysm, perinatal mortality, cervical cancer, and leukemia. Oral smokeless tobacco is associated with precancerous lesions and cancers of the oral cavity. In addition to the increased risk for developing these specific diseases, tobacco users have a significantly higher risk for general health problems than nonsmokers.(8)

According to Unani experts, tobacco consumption adversely affects the heart and brain; it can especially affect people having excitable temperaments, causing diseases such as headache, vertigo, loss of memory, insomnia, loss of vision, cough, pulmonary tuberculosis, palpitation, impotence, constipation, etc.(9–13)

Tobacco is used in different forms. Smoking is through cigarettes, bidis, hukka, and chilam (ganja). Smokeless tobacco products include tobacco that is used in pan, gutkha, zarda, khaini, and dohra.

Tobacco use is influenced by a variety of factors, including individual attitudes and beliefs, social norms and acceptability, availability, and advertising campaigns.(8) There are many misperceptions with regard to tobacco use, for example that it aids concentration, suppresses appetite, reduces anxiety and tension, causes skeletal muscle relaxation, and induces feelings of pleasure. Partly as a result of these perceived benefits tobacco consumption is highest in the labor classes and among those from a low socioeconomic status. Several studies have shown that tobacco use is higher among the less educated or illiterate, and the poor and marginalized groups.(8,14,15)

The present study was done to determine prevalence of tobacco use in a vulnerable population, i.e., power loom workers.

Materials and Methods

The present study was designed to find out the prevalence of tobacco use among power loom workers in Mau Aima Town, District Allahabad. This study was conducted over the period May 2007-June 2007. Mau Aima is a town and a Nagar Panchayat in Allahabad district in the Indian State of Uttar Pradesh. As per the 2001 Indian census,(16) Mau Aima has a population of 17,962. The main source of income in the study area is the power loom industry.

The sample size was calculated keeping in mind, level of the confidence interval 95%, precision 5% and the calculated existing population 19500. As per our calculations the minimum sample size required was 377 workers. Assuming a response rate of 75%, we randomly selected 500 power loom workers for interview via the pretested structured questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from the owners of the industries.

Data was collected on age, sex, sociodemographic profile of the workers, consumption of tobacco, age of initiation of habit, reason for initiation, money spent on the purchase of tobacco, frequency of consumption, and form of tobacco used, etc. Tobacco use was classified as current use (initiation of tobacco use within 6 months preceding the survey) and chronic use (the use of tobacco for more than 6 months).

The data were analyzed with the GraphPad InStat Demo version 3.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Standard methods were used to obtain summary statistics such as median, mean, and standard deviation. The Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used for statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 448 workers responded and were included in the study for analysis. The mean age of the workers was 39.77 ± 11.462 (SD) years. All the power loom workers were male. Fifty-one (11.38%) workers were unmarried; the rest were married or widowed.

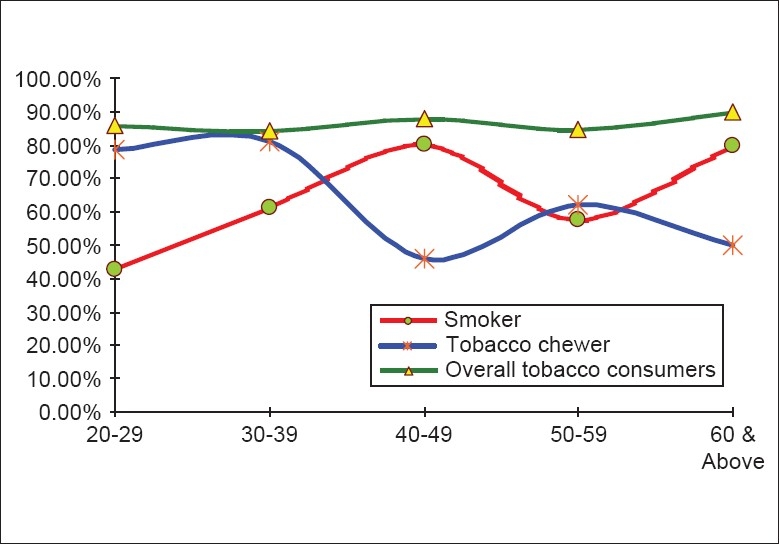

The overall prevalence of tobacco use was 85.9% (385/448), while the prevalence of smoking and tobacco chewing were 62.28% (279/448) and 66.07% (296/448), respectively. Amongst all tobacco users, 23.12% (89/385) workers were only smokers, 27.53% (106/385) used only chewing tobacco, and 49.35% (190/385) workers used both [Table 1]. Association between age and overall tobacco consumption was not statistically significant (Chi= 1.109, P = 0.8929) as shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Smoking prevalence was highest in those aged 40-49 years and lowest in those aged 20-29 years, whereas tobacco chewing was highest in those aged 30-39 years and lowest in 40-49 years [Table 2]. This difference was statistically significant (Chi = 25.526, P < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Characteristics | Data value (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 39.77 ± 11.462 years (SD) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 100 |

| Female | 0 |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 80 (17.86) |

| Muslim | 368 (82.14) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 397 (88.62) |

| Unmarried | 51 (11.38) |

| Mean monthly income | Rs. 2190.63 ± 248.49 (SD) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 55 (12.28) |

| Primary | 180 (40.18) |

| Middle | 126 (28.13) |

| Secondary | 71 (15.85) |

| Senior secondary | 13 (2.90) |

| Graduation | 2 (0.45) |

| Overall prevalence of tobacco use | 385 (85.9) |

| Smoking | 279 (62.28) |

| Tobacco chewing | 296 (66.07) |

| Smoking + tobacco chewing | 190 (42.41) |

| Overall tobacco consumers | 385/448 |

| Current consumer | 17 (4.42) |

| Chronic consumer | 368 (95.58) |

| Never consumer | 63 (14.1) |

| Age of initiation of tobacco consumption | 13.3 years (S.D. ± 3.23) |

| Influencing factor | |

| Family member | 166 (43) |

| Friends | 146 (38) |

| Advertisements/other sources | 73 (19) |

| Reason for initiating tobacco consumption | |

| Pleasure | 183 (47.6) |

| Curiosity | 113 (29.3) |

| Peer pressure | 89 (23.1) |

| Duration of tobacco consumption | Median of 24 years (17 at 25th percentile and 29 at 75th percentile) |

| Tobacco consumption/day | |

| Tobacco users | 5 (3 at 25th percentile and 8 at 75th percentile) |

| Cigarette users | 2 (1 at 25th percentile and 2 at 75th percentile) |

| Bidi users | 10 (10 at 25th percentile and 15 at 75th percentile) |

| Daily expenditure on tobacco | Rs. 8.63 ± 4.58 (SD) |

| Knowledge about hazards of tobacco use | 358 (80) |

| Desire to quit tobacco | 28 (7.3) |

| Number of subjects reporting that tobacco consumption helps in morning bowel movement | 281 (73) |

| Number of subjects reporting use of tobacco as the first thing in the morning | 334 (86.75) |

Table 2.

Age-wise distribution of tobacco consumption

| Age group | Smokers (%) | Tobacco chewers (%) | Smoker + Tobacco chewers (%) | Overall tobacco consumers (%) | No tobacco consumer (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 42 (42.86) | 77 (78.57) | 35 (35.71) | 84 (85.71) | 14 (14.29) | 98 |

| 30-39 | 74 (61.16) | 98 (81) | 70 (57.85) | 102 (84.3) | 19 (15.7) | 121 |

| 40-49 | 86 (80.37) | 49 (45.79) | 41 (38.32) | 94 (87.85) | 13 (12.15) | 107 |

| 50-59 | 53 (57.61) | 57 (61.96) | 32 (34.78) | 78 (84.78) | 14 (15.22) | 92 |

| ≥ 60 | 24 (80) | 15 (50) | 12 (40) | 27 (90) | 3 (10) | 30 |

| Total | 279 (62.28) | 296 (66.07) | 190 (42.41) | 385 (85.94) | 63 (14.06) | 448 |

Figure 1.

Relation between age and tobacco consumption

The median duration of tobacco use was 24 years (17 at the 25th percentile and 29 at the 75th percentile). We found that 17 (4.42%) workers were current users of tobacco products and 14% (63/448) had never used tobacco in any form.

Amongst the smokers, the percentages of bidi, hukka, cigarette, and ganja smoking was 74.2% (207/279), 25.45% (71/279), 11.47% (32/279), and 6.81% (19/279), respectively. Amongst the tobacco chewers, 57.8% (171/296) were gutka users, 29.4% (87/296) used tobacco with pan, 8.1% (24/296) used khaini, and 4.73% (14/296) were dohra users [Table 3].

Table 3.

Number of persons reporting consumption of tobacco in various forms according to age-group

| Form of tobacco consumption | Age group (in years) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | ≥60 | ||

| Smoking | 42 | 74 | 86 | 53 | 24 | 279 |

| Bidi | 38 | 47 | 56 | 45 | 21 | 207 |

| Cigarette | 11 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 32 |

| Hukka | 2 | 14 | 29 | 17 | 9 | 71 |

| Ganja | 0 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 19 |

| Tobacco chewing | 77 | 98 | 49 | 57 | 15 | 296 |

| Pan | 33 | 36 | 21 | 38 | 12 | 140 |

| Gutka | 47 | 73 | 26 | 18 | 7 | 171 |

| Khaini | 4 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 24 |

| Dohra | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 14 |

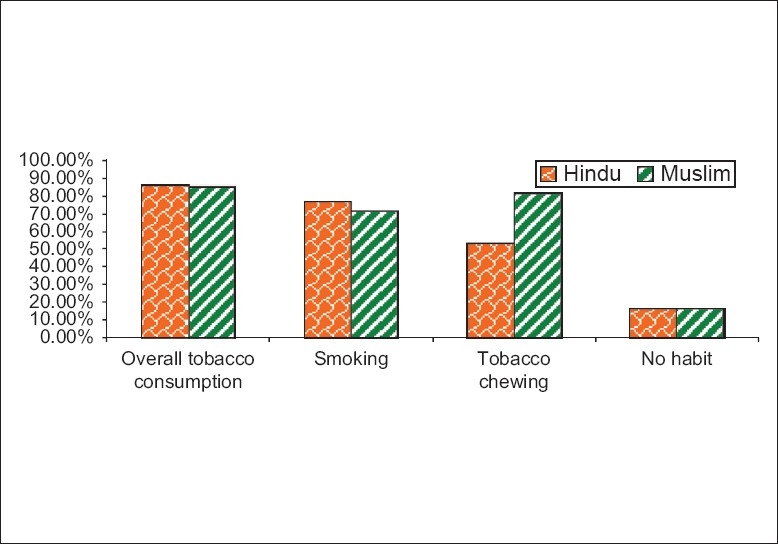

Religion-wise distribution of tobacco consumers is shown in Table 4 and Figure 2. In this study, 80 (17.86%) workers were Hindus and 368 (82.14%) were Muslims. Although the overall tobacco consumption was almost the same in Hindus and Muslims, smoking was more common in Hindus, while tobacco chewing was more in Muslims. This difference was statistically significant (Chi = 25.526, P < 0.0001).

Table 4.

Religion-wise distribution of tobacco consumption

| Habit | Religion | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hindu (%) | Muslim (%) | ||

| Tobacco consumption | 69 (86.25) | 316 (85.87) | 385 |

| Smoking | 53 (76.81) | 226 (71.52) | 279 |

| Tobacco chewing | 37 (53.62) | 259 (81.96) | 296 |

| Smoking + Tobacco chewing | 21 (30.43) | 169 (53.48) | 190 |

| No habit | 11 (15.94) | 52 (16.46) | 63 |

| Total | 80 | 368 | 448 |

Figure 2.

Religion wise distribution of tobacco consumers

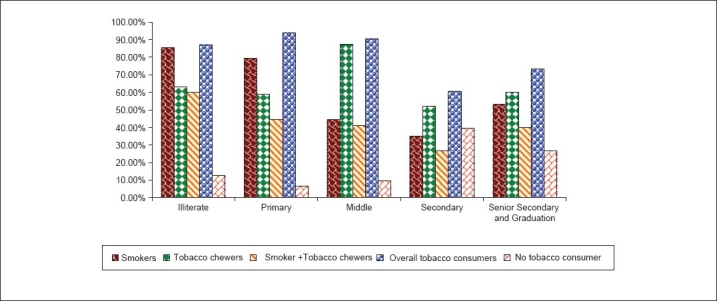

The relationship between level of education and tobacco consumption is shown in Table 5 and Figure 3. We found that tobacco consumption was more prevalent in those with less education. In general, the education level of power loom workers was very low. Only 0.04% (2/448) were graduates and only 2.9% (13/448) had been educated up to the 12th standard. The majority of the workers (40.4%) had been educated up to the 5th standard. An extremely significant negative association was found between education and tobacco consumption (Chi = 50.301, P < 0.0001).

Table 5.

Tobacco consumption according to educational level

| Level of education | Smokers (%) | Tobacco chewers (%) | Smoker + Tobacco chewers (%) | Overall tobacco consumers (%) | No tobacco consumer (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illiterate | 47 (85.45) | 34 (62.96) | 33 (60) | 48 (87.27) | 7 (12.73) | 55 (100) |

| Primary | 143 (79.44) | 106 (58.89) | 80 (44.44) | 169 (93.89) | 12 (6.67) | 180 |

| Middle | 56 (44.44) | 110 (87.30) | 52 (41.27) | 114 (90.48) | 12 (9.52) | 126 |

| Secondary | 25 (35.21) | 37 (52.11) | 19 (26.76) | 43 (60.56) | 28 (39.44) | 71 |

| Senior secondary and graduation | 8 (53.33) | 9 (60) | 6 (40) | 11 (73.33) | 4 (26.67) | 15 |

| Total | 279 | 296 | 190 | 385 | 63 | 448 |

Figure 3.

Distribution of tobacco consumers according to education

The mean income of workers was Rs. 2190.63 ± 248.49 (SD) per month. Thus, as per the revised Kuppuswamy scale, all workers were of low socioeconomic status [Table 1].

The mean daily expenditure on tobacco was Rs. 8.63 ± 4.58 (SD). Thus, 8.26% (37/448) of the workers spent one-fourth of their income on tobacco products and 27.46% (123/448) workers spent 15-20% of their income for this purpose.

The mean age at initiation of tobacco consumption was 13.3 ± 3.23 (SD) years. Nearly, 48.6% of the workers started using tobacco before the age of 13 years (23.64% at the age of 10 years or below). About 43% of workers reported that they were initiated into the habit by a family member, nearly 38% said that their friends had first introduced them to tobacco use, and 19% said that they had been induced to try out tobacco products by advertisements in various mass media (TV, videos, and movies). Pleasure(47.6%) and curiosity (29.3%) were the two major factors that instigated the consumption of tobacco, while 23.1% of the workers reported that peer pressure was the main reason for starting the habit.

The median use of chewing tobacco was 5 (3 at 25th percentile and 8 at 75th percentile) pouches or quids a day. Cigarette users smoked a median of 2 (1 at 25th percentile and 2 at 75th percentile) cigarettes per day and bidi users smoked 10 (10 at 25th percentile and 15 at 75th percentile) per day.

The majority (80%) of the workers knew that tobacco consumption was injurious to health; however, only 28 (7.3%) said that they wished to quit tobacco use.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and type of tobacco use among power loom workers in Mau Aima Town, District Allahabad, and to identify the factors that influenced them to initiate tobacco use.

The overall prevalence of tobacco use in the present study was 85.9%, which is higher than that reported by earlier community-based studies of tobacco use from other parts of the country. In a study of tobacco use in a rural area of Bihar, tobacco use had a prevalence of 78% among men and 52% among women.(17) In a rural community in Khera District in Gujarat, tobacco use was reported by 69% of males and 30% of females.(18) In a prevalence survey of tobacco use in Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh, the overall prevalence of ‘ever use’ of any kind of tobacco was 29.6% in Karnataka and 34.6% in Uttar Pradesh.(2) According to the National Sample Survey Organization, the prevalence rate of tobacco use in the country (rural + urban) is 35.5%.(19)

It is clear from this cross-sectional study that tobacco consumption is highly prevalent among power loom workers. The reasons underlying this may be low educational status, occupation involving hard labor, and poverty. Several studies have documented a positive relationship between tobacco consumption and low socioeconomic status. One major factor for heavy tobacco use in this group may be that they were also doing night shift work.

The educational level of the power loom workers was found to be very low. Consistent with earlier studies, this study found that the lower the education, the higher the prevalence of tobacco consumption. A study of smoking prevalence among men in Chennai (India) in 1997 showed that the highest rate is found among the illiterate population (64%).(20) Hence, education is an important factor to be considered in any tobacco control programme.

The average age at initiation of tobacco use was 13.3 years. About one out of four (23.64%) workers initiated tobacco use at 10 years of age or earlier, which is consistent with earlier studies.(17,21) Though the number of tobacco consumers is almost same in all the age-groups, those who started at an earlier age are more common in the 20-29 and 30-39 age-groups. This data reveals the failure of tobacco control programmes in the vulnerable section of the community.

In this study, we found that 8.26% (37/448) of the workers spent one-fourth of their income and 27.46% (123/448) spent 15-20% of their income on tobacco products. This expenditure on tobacco is very high. Money spent on tobacco means that there is less to be spent on basic human needs such as food, shelter, education, and health care. Tobacco can also worsen poverty among users and their families since tobacco users are at much higher risk of falling ill and dying prematurely of cancers, heart attacks, respiratory diseases, or other such tobacco-related diseases, imposing additional costs for health care and depriving families of much-needed income.(3) Earlier studies have also reported that tobacco consumption increases poverty.(4) In most countries, tobacco use tends to be higher among the poor.(22) The WHO says that in many societies the poorest people tend to smoke the most and bear the greatest health and economic burdens.(23)

Conclusions

The prevalence of tobacco use among power loom workers is very high compared to that in the general population. Immediate intervention programs are warranted to reduce the future burden of tobacco use-related morbidity among these workers who are already exposed to the high pollution levels in power loom factories.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Available from: www.who.org: WHO: Young girls using tobacco almost as much as boys in many regions of the world.

- 2.Chaudhry K, Prabhakar AK, Prabhakran PS. Prevalence of tobacco use in Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh in India 2001. Survey conducted y the Indian Council of Medical research with financial support by World Health Organization, South Asian regional Office.

- 3.Why is tobacco a public health priority? World Health Organization. 2004 Dec 01; [Google Scholar]

- 4.Press Release: Economic and Social Council 2002 Substantive Session 29th and 30th Meetings (AM and PM)

- 5.Gajalakshmi CK, Jha P, Ranson K, Nguyen S. Global patterns of smoking and smoking-attributable mortality. In: Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, editors. Tobacco Control in Developing Countries. New York, NY: Oxford University Press Inc; 2000. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Country profile India. J Indian Med Assoc. 1999;97:377–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, Massachussets: Harvard School of Public Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Available from: www.who.int/hpr/youth/html/yt-rar/: Introduction to the use of RAR in addressing tobacco use among young people.

- 9.Ghani Najmul. Khazainul Advia. Delhi: Illustrated Edition, Idara Kitabul Shifa Publishing House; [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdul Hakeem, Mohd . Bustanul Mufradat. Delhi: Idara Kitabul Shifa Publishing House; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan Ghulam Jilani. Makhzane Hikmat. Vol.2. New Delhi: Aijaz Publishing House; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Multani Hari. Chand: Hindustan Aur Pakistan ki Jari Botiyan Aur Un Kay Fawaed. Lahore: Maktaba Danial; [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabeeruddin Mohd. Makhzanul Mufradat Al-Maroof Khawasul Advia. Delhi: Aijaz Publishing House; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rani M, Bonu S, Jha P, Nguyen SN, Jamjoum L. Tobacco use in India: Prevalence and predictors of smoking and chewing in a national cross sectional household survey 2003. 12th ed. Tobacco Control; 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thankappan KR, Thresia CU. Tobacco use and social status in Kerala. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:300–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Census.

- 17.Sinha DN, Gupta PC, Pednekar MS. Tobacco use in a rural area of Bihar, India. Indian J Commun Med. 2003;28:167–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukherjee S. Tobacco use in a village community in Kheda District, Gujarat, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, PS Medical College, Karamsad, Gujarat, January 1999 (Unpublished)

- 19.NSSO 50th Round Survey.

- 20. Available from: www.who.int/tobacco: Tobacco increases the poverty of individuals and families.

- 21.Sinha DN, Gupta PC, Pednekar M. Tobacco use among students in Bihar. Indian J Public Health. 2004;48:111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guindon GE, Boisclair D. Past, Current and Future Trends in Tobacco Use. HNP Discussion paper, Economics of Tobacco Control Paper No.6. 2003. Feb,

- 23.Tobacco Linked to Poverty, U.N. Health Agency Reports. 2004. May 28, Available from: www.usinfo.state.gov.