Abstract

As the skeleton ages, the balanced formation and resorption of normal bone remodeling is lost, and bone loss predominates. The osteoclast is the specialized cell that is responsible for bone resorption. It is a highly polarized cell that must adhere to the bone surface and migrate along it while resorbing, and cytoskeletal reorganization is critical. Podosomes, highly dynamic actin structures, mediate osteoclast motility. Resorbing osteoclasts form a related actin complex, the sealing zone, which provides the boundary for the resorptive microenvironment. Similar to podosomes, the sealing zone rearranges itself to allow continuous resorption while the cell is moving. The major adhesive protein controlling the cytoskeleton is αvβ3 integrin, which collaborates with the growth factor M-CSF and the ITAM receptor DAP12. In this review, we discuss the signaling complexes assembled by these molecules at the membrane, and their downstream mediators that control OC motility and function via the cytoskeleton.

Keywords: αvβ3 integrin, M-CSF, podosome, migration

Skeletal Aging

Maintenance of skeletal integrity is an important part of healthy aging. In both women and men, peak bone mass is attained in early adulthood, and significant declines occur as levels of sex hormones drop, leading to osteoporosis. In the mature skeleton, the process of remodeling constantly replaces bone elements, with an average turnover interval of about 10 years. The basic multicellular unit (BMU) consists of the coupled activity of osteoclasts (OCs), which remove bone, and osteoblasts (OBs), which lay down the new organic matrix on which mineralization occurs. Bone mass is stable when the amount of bone removed by OCs is evenly balanced by osteoblastic bone formation. Bones have a dense outer shell, the cortex, and an inner network of trabeculae composed of a dense network of rods and plates, which impart structural stability, while allowing for needed flexibility. Over time, both cortical and trabecular bone is remodeled. In osteoporosis, bone resorption outpaces bone formation, resulting in net bone loss, particularly in the trabeculae-rich bone of vertebrae and femoral neck, which are common sites of fragility fracture.

OC differentiation

The only cell capable of removing both the organic and inorganic matrices of bone is the OC, a multinucleated cell derived from fusion of bone marrow cells in the monocyte/macrophage lineage (Ikeda, et al., 1998). Like other monocyte/macrophages, they require the growth factor M-CSF to interact with its receptor c-Fms, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), which provides proliferative signals to the precursors as well as survival signals for mature cells (Ross and Teitelbaum, 2005). Differentiation to the OC lineage also requires Receptor Activator of NF-κB Ligand (RANKL), a TNF family cytokine that binds to the receptor RANK (Lacey, et al., 1998; Yasuda, et al., 1998). RANK is related to other TNF receptors, and has a long cytoplasmic tail that complexes with signaling modules activating NF-κB, JNK/AP1,Ca/calmodulin, c-Src and PI3K pathways (Novack and Teitelbaum, 2008). Signaling via RANK requires costimulation via one of 2 ITAM-containing receptors, DAP12 and FcRγ (Koga, et al., 2004; Mocsai, et al., 2004). For differentiation, cooperative activation of the NF-κB, JNK/AP1, and Ca/calmodulin pathways leads to activation of the transcription factor NFATc1, a primary driver of expression of many genes required for OC function, including cathepsin K, β3 integrin, and calcitonin receptor (Ikeda, et al., 2004). NF-κB activity is one of the earliest signals following RANKL stimulation, and is required for precursor survival during commitment to the OC lineage (Vaira, et al., 2008a) as well as for full differentiation (Vaira, et al., 2008b). OCs can be differentiated in vitro from bone-marrow derived macrophages by treatment with soluble M-CSF and RANKL. In vivo, OBs and their precursors appear to be the most important source of both M-CSF and RANKL for osteoclastogenesis (Tsurukai, et al., 2000).

Another necessary feature of OC differentiation is fusion of mononuclear precursors to form the mature polykaryon. Transmembrane proteins DC-STAMP and Atp6v0d2, a subunit of the vacuolar ATPase, are required for OC multinucleation, and both are transcriptionally regulated by NFATc1 (Kim, et al., 2008; Yagi, et al., 2005; Yagi, et al., 2007). Mononuclear OCs lacking DC-STAMP or Atp6v0d2 have decreased bone-resorbing capacity, despite normal expression of markers of differentiation.

Resorptive machinery of an active OC

Mature OCs polarize when attached to bone, which occurs via the αvβ3 integrin that recognizes matrix proteins such as bone sialoprotein and osteopontin. The integrin and an associated cytoskeletal complex (discussed below) form a sealing zone, a ring-shaped boundary where the OC membrane is very closely apposed to the bone surface, defining an isolated extracellular space between the OC and the bone surface. In fact, at least in vitro, individual OCs can form more than one sealing zone. Bone resorption occurs in the space between the bone and OC defined by the sealing zone, known as the resorption lacuna. A specialized resorptive organelle, the ruffled membrane, is formed by fusion of secretory vesicles into the plasma membrane within the sealing zone. This directional vesicular trafficking occurs along microtubules, and then microfilaments, mediated by the small GTPases Rab7, Rab3D and Rac1 (Coxon and Taylor, 2008; Sun, et al., 2005). The vesicles contain the H+/ATPase needed for secretion of acid, and the ClC-7 chloride channel, which maintains electroneutrality across the OC membrane. In order to accomplish acidification, the OC also requires activity of a HCO3-/Cl- exchanger on the basolateral membrane and cytoplasmic carbonic anhydrase, which generates HCO3- and H+ from CO2 and H2O. Acidification of the lacunar space due to secretion of HCl dissolves the mineral hydroxyapatite, which precedes enzymatic degradation of collagen. Abnormalities of components of the acidification pathway, such as the H+/ATPase (Frattini, et al., 2000) or ClC-7 (Kornak, et al., 2001) cause osteopetrosis, a rare inherited disease in which the bones become very dense and fracture easily. Matrix proteases, particularly cathepsin K, are also present in the vesicles transported to the ruffled membrane (Saftig, et al., 1998). Inactivating mutations of cathepsin K in humans cause pyknodysostosis, a disorder characterized by increased bone mass, dwarfism and facial dysmorphism (Hunt, et al., 1998). Thus, a combination of acidification and enzymatic digestion of organic matrix components cooperate to fully remove bone within this well-defined area (Novack and Teitelbaum, 2008).

Podosomes: organizing principle of the OC cytoskeleton

The primary component of the cytoskeleton is F-actin, and the OC has a distinct actin complex known as the podosome which mediates its attachment to the bone matrix (Destaing, et al., 2003). Podosomes contain an F-actin core that also concentrates actin regulatory proteins including cortactin, Wiskott Aldrich Syndrome Protein (WASP), WASP Interacting Protein (WIP), Arp2/3, and gelsolin, as well as CD44, another adhesion receptor. Surrounding the core are adhesion-associated proteins such as integrins, vinculin, paxillin, and talin (Linder and Deschenes, 2007; Linder and Aepfelbacher, 2003; Marchisio, et al., 1988; Pfaff and Jurdic, 2001; Zambonin-Zallone, et al., 1989). Co-staining of OCs for actin and αvβ3 integrin or vinculin shows a characteristic “donut” of the latter complex of adhesive proteins enclosing a dense actin core. The area surrounding the actin core is also rich in kinases such as c-Src and Pyk2, and the small GTPases Rho, Rac, and cdc42. Also surrounding the dense actin core is a loose network of F-actin cables known as the actin cloud. Although both the actin core and the actin clouds are essential for proper podosome organization and bone resorption, they appear to be independent structures. OCs lacking the kinase c-Src do not have an actin cloud, while those lacking WIP have no actin core (Chabadel, et al., 2007; Destaing, et al., 2008). Ultimately, both molecules are essential for podosome formation, since both c-Src- and WIP-deficient OCs have resorptive defects.

In vivo imaging studies using preosteoclasts expressing green fluorescent protein-actin plated on glass have been useful in studying podosome dynamics. In OC precursors, podosomes randomly distribute throughout the cell, then coalesce into simple clusters and rings as differentiation proceeds. Continuous addition of new podosomes at the outer edge of each ring, with suppression of podosome formation within rings finally generates a single podosome belt at the periphery of mature OCs (Destaing, et al., 2003). Interestingly, the podosome belt is surrounded by an actin cloud, which interconnects all podosome cores (Saltel, et al., 2008). Although the podosome belt appears to be a stable structure, individual podosomes are short lived, with an average lifespan of 2-12 min. Photobleaching experiments show that the F-actin within each podosome is even more dynamic, with recovery in 1 min, suggesting that the podosome belt is also a site of continuous actin polymerization.

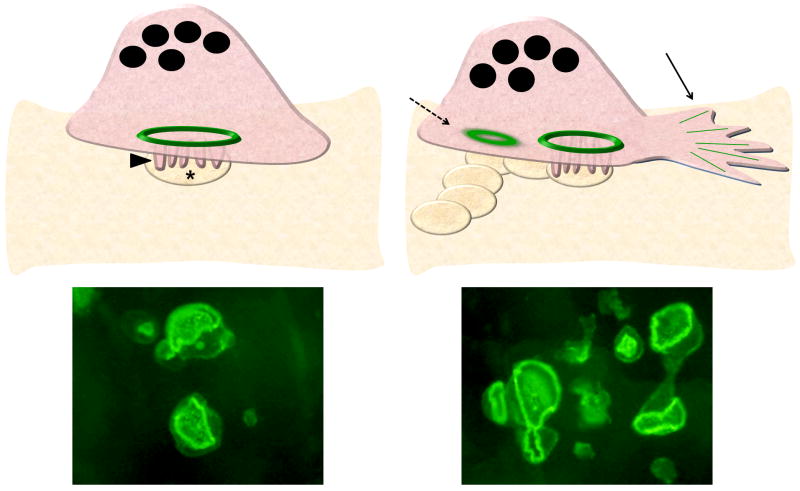

How is it that the podosome belt, comprised of dynamic and short-lived actin structures, does not dissolve? It is believed that podosome belts are stabilized by a network of microtubules (MTs), although the exact molecular interactions between F-actin and MTs have not been elucidated (Jurdic, et al., 2006). Indeed, treatment with nocodazole (an MT depolymerizing agent), while not affecting podosome formation per se, controls the transition between podosome clusters and rings into peripheral belts. During this transition, tubulin, the subunit of MTs, accumulates a specific post-translational modification, acetylation. The specific function of this acetylation is still unknown, but it is believed to play an important role in MT stabilization because only the pool of MTs associated with the stable podosome belt is acetylated. Further evidence of the functional importance of MT acetylation comes from the study of active OCs (Saltel, et al., 2008). When plated on bone (or on surfaces mimicking bone such as apatite collagen complex) that can be resorbed, OCs do not form single podosomes or the peripheral podosome belts typical of cells plated on glass. Instead these resorptive cells organize an inner actin ring which is the functional unit of the OC membrane at the sealing zone (Luxenburg, et al., 2007) (Figure 1, left). Although the actin ring in the sealing zone is thicker than in the podosome belt, the molecular components (eg. αvβ3, vinculin, c-Src, Pyk2, small GTPases) are the same. Like the podosome belt, the sealing zone is associated with acetylated MTs, suggesting that its stability is also MT dependent.

Figure 1.

The sealing zone in resorbing OCs. Left, An OC on bone is a tall polarized cell with its robust actin ring (green) forming the backbone of the sealing zone, and area of membrane tightly juxtaposed to the bone surface that defines the resorption lacuna (asterix). Within the sealing zone is the specialized membrane organelle known as the ruffled border (arrowhead), formed by fusion of intracellular vesicles containing the enzymes and transmembrane proteins needed for bone resorption. A FITC-phalloidin stained OC plated on bone, demonstrating a single actin ring, is shown below. Right, As it resorbs, an OC moves, with forward membrane extensions (solid arrow). New sealing zones form, encircling a ruffled border, and forming a trail of resorption lacuae. Old sealing zones (dotted arrow) toward the rear of the cell dissolve. Each OC can have several actin rings, as shown in the FITC-phalloidin stain of OCs on bone, below.

MT stability is also regulated by the small GTPase Rho. Indeed, Rho inhibition by the bacterial exoenzyme C3 induces formation of stable and highly acetylated MTs, making the podosome belt more resistant to dissolution by nocodazole (Destaing, et al., 2005). Colocalizing with MTs is a complex Rho itself, mDIA2, a Rho effector, and HDAC6, a cytosolic histone deacetylase which deacetylates MTs (Matsuyama, et al., 2002). The interaction between mDIA2 and HDAC6 increases the deacetylase activity of the enzyme. Thus it appears that Rho modulates the stability of the MTs, by decreasing acetylation of tubulin in a mDIA2/HDAC6-dependent manner. During osteoclastogenesis, this pathway is downregulated to allow the acetylation of a subset of MTs which are important for the formation of the podosome belt (on glass) and sealing zone (on bone).

Visualization of the pits formed by OCs plated on bone demonstrates that each OC typically produces a “trail” that is longer than the cell is wide, indicating that migration is part of the resorption process. As the cell moves, it rearranges its cytoskeleton to form new sealing zones and dissolve old ones (Figure 1, right). In fact, a single resorbing OC on bone can have multiple sealing zones. Although the exact signals leading to sealing zone dissolution and reassembly remain undefined, it is likely that dynamic regulation of MTs by the Rho pathway is central to this process.

M-CSF: a migratory stimulus and actin regulator

In most cells, migration involves directed protrusion at the leading edge through localized polymerization of actin, forming a membrane extension called a lamellipodium. Integrin-mediated adhesion to the substrate stabilizes adhesions, allowing cells to generate tension and the contractile force required for cell movement. Adhesion is then released at the rear of the cell to allow continued forward movement. Migration in OCs is regulated by 2 main pathways, αvβ3 integrin, which mediates substrate attachment, and M-CSF, which is a potent chemotactic stimulus for these cells. Re-addition of M-CSF to quiescent macrophages and OCs stimulates rapid cytoskeletal reorganization, podosome dissolution and lamellipodia formation (Faccio, et al., 2003a; Fuller, et al., 1993). Exposure to the cytokine also increases cell motility within a few minutes, followed by chemotactic migration up a gradient of diffusing cytokine.

M-CSF binds to its receptor c-Fms, a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family and induces receptor autophosphorylation at seven tyrosine residues within the cytoplasmic domain (Pixley and Stanley, 2004; Ross and Teitelbaum, 2005). Several Src homology 2 (SH2) and PTB domain-containing molecules are recruited to the phospho-Tyr residues upon M-CSF binding and initiate cell proliferation, differentiation, and cytoskeletal reorganization. The key members of the signaling complex from c-Fms to the cytoskeleton are c-Src, Syk, PI3K, and Cbl.

By using a chimeric receptor approach consisting of the extracellular domain of the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) fused to the transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail of c-Fms, expressed in macrophages and osteoclasts, critical c-Fms Tyr residues modulating the migratory response and actin dynamics have been identified in these cells (Faccio, et al., 2007). Specific Tyr to Phe mutations confirm that c-Fms Tyr-559 binds c-Src in OCs and other Src Family Kinases (SFKs) in macrophages, while Tyr-721 binds phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K). Surprisingly, despite the known role of PI3K in M-CSF-dependent signaling to the cytoskeleton (Grey, et al., 2000; Jones, et al., 2003), the c-Fms Tyr-721 to Phe mutant, while affecting the direct binding of PI3K, does not impair podosome redistribution or the chemotactic response to M-CSF. Indeed, it is Tyr-559 of c-Fms which is required for M-CSF dependent cytoskeletal changes, lamellipodia formation and motility. These data suggest that although PI3K is important for M-CSF-induced macrophage and OC motility, direct binding of PI3K to c-Fms is not necessary.

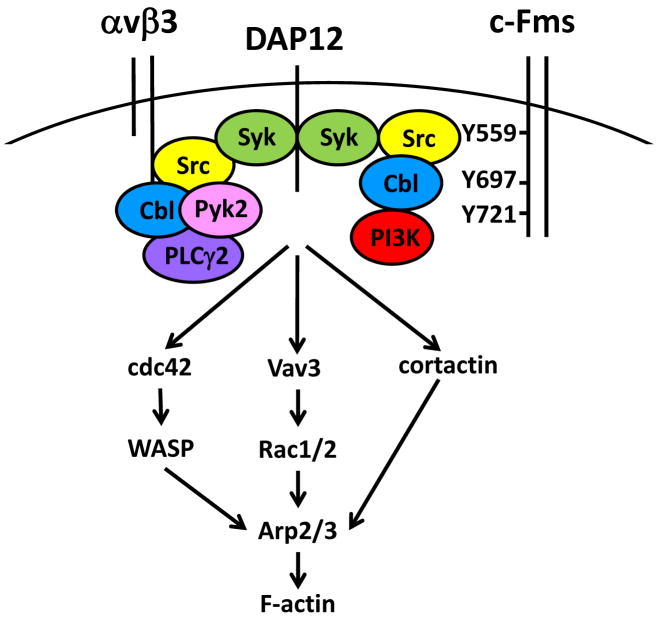

Co-immunoprecipitation studies demonstrate that a ternary complex between c-Src, Cbl and PI3K forms at Tyr559 (Faccio, et al., 2007). Upon M-CSF stimulation, c-Src becomes phosphorylated and binds to c-Fms-Tyr559 via its SH2 motif. c-Src also binds the proline rich region of Cbl with its SH3 domain and phosphorylates it. Cbl then recruits PI3K to activate the downstream pathways leading to actin reorganization. Although the c-Src/Cbl/PI3K complex is anchored to c-Fms-Tyr559, it does not form in cells expressing a mutant c-Fms receptor with the Tyr559 as the sole intact tyrosine. Instead, this complex requires stabilization via secondary binding to Tyr697 and Tyr721 of c-Fms. In concert with the critical role of the c-Src/Cbl/PI3K complex, cooperation between c-Fms Tyr559, Tyr697 and Tyr721 is required to restore the full chemotactic response to M-CSF (Figure 2). This set of interactions eventuates in Vav3/Rac activation and thus cytoskeletal reorganization (see below for details).

Figure 2.

Signaling complexes assembled at c-Fms and αvβ3, and downstream effectors to the cytoskeleton in the OC. Right, The cytoplasmic tail of c-Fms (the receptor for M-CSF) recruits a complex of Src, Cbl, and PI3K anchored at Tyr(Y)559, and stabilized by Y697 and Y721. This complex interacts with the ITAM-containing adapter DAP12, which associates with Syk to initiate downstream signals to the cytoskeleton. Left, The cytoplasmic tail of β3 integrin, binds a complex containing Src, Cbl, Pyk2, and PLCγ2, which also interacts with DAP12-associated Syk to activate cytoskeleton-modifying pathways. Vav3, an upstream regulator of Rac1/2, is activated by both pathways and is a direct target of Syk. The αvβ3 integrin and c-Fms complexes can also activate cdc42 and WASP, as well as cortactin, which along with Rac lead to Arp2/3 dependent changes in F-actin.

αvβ3 integrin: linking the OC to bone

Dynamic changes in the osteoclast cytoskeleton associated with the bone resorptive process are controlled by αvβ3 integrin (Faccio, et al., 2003a). Deletion of β3 in mice leads to a progressive increase in bone mass, due to failure of resorption (McHugh, et al., 2000). When differentiated in vitro, β3-/- osteoclasts do not spread or form a podosome belt when plated in physiological amounts of RANKL and M-CSF (Feng, et al., 2001). Confirming their attenuated resorptive activity, β3-/- osteoclasts generate fewer and shallower resorptive lacunae on dentin slices than do their wildtype counterparts. Furthermore, absence of β3 integrin also impairs motility towards M-CSF (Faccio, et al., 2003a). Consequently, anti-αvβ3 antibodies (Horton, et al., 1991), and peptides and proteins containing the arg-gly-asp (RGD) motif recognized by the integrin (Fisher, et al., 1993; Horton, et al., 1991) inhibit bone degradation, in vitro, and are now under investigation for their use in vivo.

Similar to other integrin receptors, αvβ3 exists in two configurations, which confer either low affinity or high affinity towards RGD motif containing proteins in the bone matrix, such as osteopontin. In the default low affinity state, the extracellular domain of the receptor assumes a bent conformation which is maintained by interactions between the cytoplasmic tails of the α and β subunits (Takagi, et al., 2002). Separation of the two cytoplasmic tails causes the extracelluar domain to straighten, leading to an open configuration that allows efficient ligand binding, thereby increasing its affinity. The process of conformational change is known as integrin activation, and it can occur by two distinct mechanisms known as outside-in and inside-out activation.

In outside-in activation, ligand initially binds to αvβ3 in its low affinity state causing conformational changes that enhance the affinity of the integrin receptor (Qin, et al., 2004). Artificially induced outside-in activation can also be caused by extracellular chemicals or monoclonal antibodies prior to ligand binding (Honda, et al., 1995).

In contrast, inside-out activation is an indirect process in which intracellular signals driven by another receptor, typically that of a cytokine or growth factor, affects the intracellular domain of the integrin. In the OC, M-CSF targets the β3 subunit cytoplasmic domain, and alters the conformation of αvβ3 to its high affinity, ligand-binding state (Faccio, et al., 2002; Faccio, et al., 2003a). M-CSF also induces a stable interaction between c-Fms and αvβ3 in these cells (Elsegood, et al., 2006). Additionally, defective c-Fms prevents OC spreading on αvβ3-ligand coated surfaces (Faccio, et al., 2007). The consequences of this cytokine-induced, inside-out activation of αvβ3 are increased adhesion, motility and stimulation of the resorptive signaling pathway. These experiments support a cooperative model, in which αvβ3 and M-CSF signals are both required for optimal bone resorption.

αvβ3 integrin and OC motility

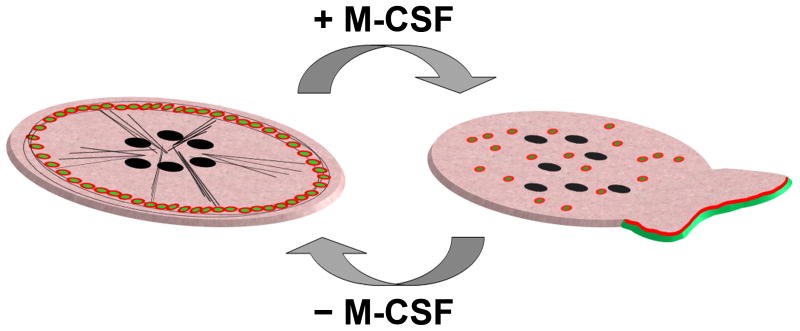

αvβ3 integrin localizes around the actin core of podosomes in the podosome belt of OCs plated on glass (Figure 3, left). When OCs are stimulated to migrate with M-CSF, their cytoskeleton rapidly reorganizes. Podosome belts dissolve and αvβ3 moves to the leading edge of the lamellipodia (Figure 3, right). In resorbing cells on bone, αvβ3 integrin is distributed along the inner and outer edge of the ring of actin forming the sealing zone. The cytoplasmic tail of the integrin receptor is required for its localization to the podosomes and lamellipodia. Retroviral expression of various β3 integrins with cytoplasmic tail mutations in β3-deficient OC precursors revealed that Ser752 is important for M-CSF-induced cytoskeletal reorganization and membrane protrusion. Mutation of Ser752 to Pro prevented OC adhesion, migration, and bone resorption (Faccio, et al., 2003a). This finding is particularly important in light of the human disease called Glanzmann's thrombasthenia, characterized by excessive bleeding, in which the mutation of β3 Ser752 to Pro is causative. Osteopetrosis was associated in one individual with this disease (Yarali, et al., 2003), but most patients have relatively normal bone mass, perhaps due to compensation by β1 integrins (Horton, et al., 2003).

Figure 3.

Cytoskeletal changes in migrating OCs on glass.

Left, OCs on glass or plastic are flat, nonpolarized cells. Their peculiar characteristic is the presence of a peripheral ring of actin formed by aligned podosomes, short lived and highly dynamic actin structures. Each podosome is composed of a bundle of perpendicular actin filaments (green dots) surrounded by αvβ3 integrin (red circle) and actin binding proteins. Microtubules (black lines) associate with, and are thought to stabilize, the actin ring. Right, Extracellular stimuli, including M-CSF, can lead to rapid actin reorganization. The peripheral ring of actin dissolves, podosomes redistribute throughout the cell and polarized membrane extensions called lamellipodia form. F-actin (green line) is present at the leading edge of the lamellipodia, where it is associated with activated αvβ3 integrin (red line).

The β3 cytoplasmic tail also contains Tyr747 and Tyr759. While affecting platelet functions, β3 Tyr747/759Phe mutants expressed in OCs do not have any effect on the appearance and resorptive capabilities of these cells, despite moderately decreased adhesiveness to OPN (Faccio, et al., 2003a). In other cellular contexts, phosphorylation levels of the β3 Tyr747 and Tyr759 have been correlated with strength of binding during adhesion (Boettiger, et al., 2001). It is possible that during the dynamic process of migration and resorption in OCs, stable and strong adhesion, such as that supported by phosphorylation of these two Tyr residues, is not required.

αvβ3 adhesion complex

Engagement of the αvβ3 integrin leads to remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton through the formation and activation of a large “adhesion complex”, containing enzymes, adaptors and scaffolding proteins. One major component of this complex in the OC is c-Src. c-Src knockout mice are severely osteopetrotic with OCs that fail to resorb bone (Soriano, et al., 1991). In Src-/- OCs, the peripheral podosome belt is absent and replaced by irregular patches at the cell center, likely due to a decrease in podosome number and/or altered dynamics (Destaing, et al., 2008). Not surprisingly, Src-/- OCs also show impaired adhesion, spreading and migration (Destaing, et al., 2008; Insogna, et al., 1997; Sanjay, et al., 2001).

The similar cytoskeletal phenotypes of c-Src and αvβ3-deficient osteoclasts further indicate a commonality of intracellular signaling between the two molecules. c-Src binds directly to the terminal three amino acids of the β3 subunit in the context of the platelet integrin αIIbβ3 (Arias-Salgado, et al., 2003), and the same residues regulate αvβ3–c-Src association in the OC (Zou, et al., 2007). Activation of c-Src in this complex is αvβ3-ligand dependent. Phosphorylation at Tyr527 by C-terminal Src kinase (Csk) induces an intramolecular interaction with the SH2 domains of Src that inhibits Src kinase activity, whereas autophosphorylation at Tyr416 is required for its activation (Yeatman, 2004). Protein-protein interactions with the SH2 and SH3 domains can also relieve the intramolecular inhibitory state and serve to activate Src. For instance, when the SH3 domain of Src interacts with the tail of the β3 integrin, following integrin clustering, phosphorylation of Src at Tyr416 is induced.

Still controversial is the mode of integrin-dependent Src activation and its localization at particular intracellular sites. One model holds that Pyk2 and c-Cbl mobilize c-Src to the integrin (Sanjay, et al., 2001). Upon adhesion, Pyk2 Tyr402 becomes phosphorylated and activates c-Src by occupying its SH2 domain. However, this scenario does not explain why the bone phenotype of Cbl or Pyk2 deficient animals is not as profound as that attending Src deletion, or why Pyk2 phosphorylation is normal in β3 integrin null OCs, in which Src and Cbl activation is downmodulated (Chiusaroli, et al., 2003; Gil-Henn, et al., 2007). An alternative hypothesis posits that c-Src is an upstream mediator of Pyk2 activation. Rodan's group demonstrated that following αvβ3 integrin engagement, c-Src is phosphorylated at Tyr416, activating its kinase activity and inducing an interaction between the SH2 domain of Src and Pyk2 (Lakkakorpi, et al., 2003). Calcium signals lead to Pyk2 autophosphorylation and subsequent further tyrosine phosphorylation by Src and mobilization to the integrin.

From all the above studies it appears that the mechanistic relationship between Src and Pyk2 is complex. The activity of each is diminished in the absence of the other, suggesting mutual dependence. It is surprising that despite the fact that Pyk2 is an integral component of the adhesive complex, the bone phenotype of Pyk2 deficient mice is not as dramatic as c-Src or αvβ3-/- mice.

Phospholipase C (PLC)γ2 is an additional molecule shown to regulate Src activation and localization with αvβ3 and Pyk2 (Epple, et al., 2008). PLCγ2 can generate PIP2 and DAG, thereby increasing intracellular calcium, and also acts as an adapter protein via its SH2, SH3, and pleckstrin homology domains. Association between PLCγ2 SH2 motifs and Pyk2 in OCs is dependent on adhesion (Nakamura, et al., 2001). Mice deficient for PLCγ2 are osteopetrotic due to inhibition of OC differentiation (Mao, et al., 2006). By using PLCγ2-deficient OC precursors overexpressing NFATc1 to circumvent their blockade in OC differentiation, it has been shown that PLCγ2 is critical for Src phosphorylation and its recruitment to the αvβ3 adhesion complex. In PLCγ2-/- OCs, Src is randomly distributed on the cell membrane without localizing to the peripheral podosome belt. While not affecting Pyk2 localization, PLCγ2 is still required for its phosphorylation and association with c-Src and αvβ3. Consequently, NFATc1-rescued PLCγ2-deficient OCs do not migrate or spread normally or resorb bone (Epple, et al., 2008).

Both the catalytic activity and adapter functions of PLCγ2 may be required for Pyk2 activation and consequently Src localization. Pyk2 autophosphorylation at Tyr402 is a calcium-dependent event that occurs independent of Src activity (Sanjay, et al., 2001). PLCγ2-null cells have decreased levels of Pyk2 -phosphoTyr402 in response to integrin engagement (Epple, et al., 2008), which may contribute to abnormal Src localization in these cells. Furthermore, treatment with the PLCγ inhibitor U73122, which likely influences Tyr402 phosphorylation of Pyk2, disrupts the Src/Pyk2/β3 adhesive complex in adherent WT OCs. In further support of a role for the lipase activity of PLCγ2, OCs carrying the PLCγ2 catalytic domain mutant display improper Src localization. However, the adapter function of PLCγ2 also appears to modulate the αvβ3 adhesive complex. Mutation in the SH2, but not SH3, domains of PLCγ2 abrogates Src activation, localization and consequently the formation of a sealing zone. Thus, while the catalytic activity of PLCγ2 enhances Pyk2 phosphorylation via calcium signals, PLCγ2, via its SH2 motif, can also directly bind to Pyk2, recruiting it and Src to the integrin complex.

The mechanism of PLCγ2 regulation in response to adhesion remains to be fully elucidated. Considering that ITAM (immune tyrosine-based activating motif)-containing receptors, such as DAP12 and FcRγ, modulate PLCγ2 phosphorylation in neutrophils, macrophages, platelets, and osteoclasts (Jakus, et al., 2007), it is likely that these receptors also control PLCγ2 activation in response to integrin engagement (Figure 2).

DAP12: a point of convergence between αvβ3 and M-CSF signaling pathways

DAP12, a transmembrane adapter molecule expressed in immune cells, is one common orchestrator of growth factor and integrin signals (Lanier and Bakker, 2000; Tomasello, et al., 1998). In myeloid cells, DAP12 pairs with surface residing receptors including triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells and osteoclasts (TREMs) (Colonna, 2003). The cytoplasmic domain of DAP12 contains the ITAM motif, which when phosphorylated functions as a docking site for tyrosine kinases, including Syk (McVicar, et al., 1998). Deletion of the DAP12 gene, in man, results in Nasu-Hakola disease, which includes skeletal abnormalities in its phenotype (Hakola, 1972). Furthermore, DAP12 is expressed by OCs and, as evidenced by the development of mild osteopetrosis in mice lacking the protein, is important for normal resorptive function (Kaifu, et al., 2003; Kondo, et al., 2002).

Due to the presence of another ITAM-containing receptor on the OC surface, FcRγ, DAP12-deficient precursors differentiate normally in vitro. However, they appear smaller, do not form podosome belts, and lack the ability to resorb bone (Faccio, et al., 2003b; Zou, et al., 2007; Zou, et al., 2008). The functional defect of DAP12-/- OCs is due to impaired M-CSF and αvβ3 integrin signaling. In response to integrin engagement or M-CSF stimulation, the 2 tyrosine residues of the DAP12 ITAM motif are phosphorylated by c-Src. The modified ITAM can then bind another non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Syk and trigger a cascade of signals, including PLCγ2 activation, which culminates in cytoskeletal reorganization. Syk is directly phosphorylated by c-Src following αvβ3 integrin engagement. Mutation in the Syk SH2 motifs which abrogates the capacity of the molecule to bind to DAP12 while retaining binding with αvβ3 disrupts the association of Src and Syk and thus the OC cytoskeleton (Zou, et al., 2008). The Syk-/- OC phenotype resembles that of β3 integrin-deficient cells, as Syk-/- preosteoclasts show defective spreading and adhesion when plated on αvβ3 integrin-ligand surfaces and do not resorb bone (Faccio, et al., 2003b). Although lethal in utero, the in vivo bone phenotype of Syk-/- embryos or chimeric mice bearing Syk-/- hematopoietic cells also manifest defective bone resorption (Zou, et al., 2007). In addition to its activation by integrin adhesion, Syk also becomes activated by M-CSF stimulation in a DAP12-dependent manner, although in this circumstance the mechanism is autophosphorylation rather than trans-phosphorylation by Src (Zou, et al., 2008). Mutation in the SH2 motif of Syk abrogates its binding to the ITAM motif of DAP12 and dampens the response to M-CSF. Thus, the Syk/DAP12 association represents a point of convergence between M-CSF and αvβ3 signaling to the cytoskeleton.

Downstream mediators of motility/cytoskeleton in the OC

The key effector for cytoskeletal rearrangement in OCs immediately downstream of Syk, and therefore M-CSF, αvβ3 integrin and DAP12, is Vav3. Syk activates Vav3 by direct phosphorylation. Vav3 null mice have increased bone mass due to decreased bone resorption by OCs (Faccio, et al., 2005). In vitro, Vav3-/- OCs differentiate normally, but they fail to form podosome belts on glass or a sealing zone on bone, and have little resorptive activity.

Vav3 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the Rho family small GTPase Rac. GTPases such as Rac are regulated by the type of guanine nucleotide bound; GTP-bound Rac is active, while the GDP-bound form is inactive. GEFs such as Vav3 bind GDP-Rac, causing a conformational change that favors release of GDP and binding of GTP, which is present at high concentrations in the cell. Rac is also regulated by post-translational addition of a geranylgeranyl moiety at its C-terminus, which allows insertion into the plasma membrane. The intrinsic GTPase activity of Rac returns it to the GDP-bound inactive form, a process which is accelerated by binding of another class of regulators, the GTPase activating proteins (GAPs). However, a specific GAP for Rac that is active in OCs has not yet been described. In most cell types, Rac is important for cell motility because it regulates formation of lamellipodia at the leading edge, and promotes formation and turnover of adhesive complexes such as podosomes (Ridley, et al., 2003).

Rac has 3 isoforms, but only Rac1 and Rac2 are present in OCs and their precursors. Rac1 is expressed at higher levels than Rac2 in this lineage (Wells, et al., 2004; Yamauchi, et al., 2004). Studies of mice lacking Rac1 and Rac2, alone or in combination establish some compensation between the isoforms. Deletion of both is required to generate a significant increase in bone mass in vivo. Rac1/2 double-deficient OC precursors are smaller, and have fewer lamellipodia than wildtype controls. They also migrate poorly in response to M-CSF, with the latter effect being controlled only by Rac1 (Wang, et al., 2008). Adenovirus vector-mediated expression of dominant-negative Rac1 reduces membrane ruffling and spreading of OCs in response to M-CSF, suggesting that Rac controls OC motility as well as spreading (Fukuda, et al., 2005). Further supporting evidence of the role of Rac in OC motility comes from neurofibromatosis type 1 (Nf1). Nf1+/- OCs have increased motility and podosome belts, resulting in increased resorptive activity. In mice, removing Rac1 from Nf1+/- cells normalized actin organization and OC motility (Yan, et al., 2008).

Activated Rac stimulates many downstream effectors, several of which regulate the formation or stabilization of F-actin. However, Rac-activated pathways have not been defined in the OC.

cdc42

cdc42 is another Rho family small GTPase which, when overexpressed as an activated mutant form in macrophages and OCs disrupts podosomes, depleting the core of F-actin (Chellaiah, 2005; Linder, et al., 1999). However, more recent studies using mice with increased cdc42 activation due to knockout of its negative regulator cdc42GAP have shown increased sealing zone formation and bone resorption, compared to wildtype cells. Additionally, the formation of the Par3/Par6/aPKC polarity complex downstream of RANKL in OCs seems to depend on cdc42 (Ito, et al., 2007), further supporting the important role of cdc42 in OC activity.

Cdc42 binds directly to Wiscott Aldrich Syndrome protein (WASP) (Chellaiah, 2005; Rohatgi, et al., 1999), a multi-domain adapter protein regulating transmission of signals to the actin cytoskeleton. WASP depletion in macrophages leads to a virtual absence of podosomes (Jones, et al., 2002) and a defective chemotactic response under a gradient of M-CSF. Similarly, WASP deficient OCs are depleted of podosomes and fail to assemble normal actin rings on bone, resulting in impaired resorption (Calle, et al., 2004). Although physiological steady-state levels of bone resorption are maintained, a major impairment is observed when WASP-null animals are exposed to a resorptive challenge (Calle, et al., 2004). Interestingly, when PIP2 is bound to WASP, its interaction with cdc42 is enhanced. Furthermore, PIP2 levels are affected by the activity of RhoA (Chellaiah, 2005).

One important function of WASP is to activate the actin-related protein (Arp) 2/3 complex, required for de novo actin polymerization. The Arp2/3 complex is essential for formation of actin trimers, which can quickly be assembled into actin filaments, generating the force necessary for membrane protrusions. Small interfering RNA suppression of the Arp2/3 complex (Hurst, et al., 2004) disrupted podosomes and actin ring formation in OCs.

Another protein important for actin dynamics in the OC is cortactin (Tehrani, et al., 2006), which directly binds both Arp2/3 and F-actin. Cortactin, whose expression is upregulated during OC differentiation, is a prominent Src substrate (Maa, et al., 1992). Depletion of cortactin from OCs with shRNA results in a loss of podosomes and membrane protrusions, resulting in a lack of a sealing zone and ablation of bone resorption (Tehrani, et al., 2006). A cortactin mutant that could not be phosphorylated by Src localizes normally but does not rescue podosome formation in cortactin-depleted OCs.

RANKL and the OC cytoskeleton

In addition to its critical role in OC differentiation, RANKL has also been linked to control of the cytoskeleton. Addition of RANKL to mature OCs on bone enhances actin ring formation and bone resorption (Burgess, et al., 1999). With RANKL stimulation of OCs expressing RANK mutants that are unable to interact with TRAF6, F-actin is found in clumps rather than rings, and c-src and c-cbl are mislocalized. As expected, bone resorption is impaired (Armstrong, et al., 2002). Recently, a cell-permeable peptide corresponding to a non-TRAF binding RANK cytoplasmic motif was found to disrupt the OC cytoskeleton by blocking phosphorylation of Vav3, and preventing Rac and Cdc42 activation (Kim, et al., 2009). Addition of this peptide to mature OCs caused cell retraction, loss of the actin ring, and a dramatic reduction in bone resorption. This peptide did not affect Vav3 and Rac signaling initiated by M-CSF, indicating that these two cytokines can activate the same downstream pathways independently. Considering that RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis requires costimulation of ITAM receptors, DAP12 and FcRγ, it is very likely that these cooperative signals also modulate RANKL-dependent cytoskeletal changes, in a similar manner to that described for M-CSF signaling.

Conclusion

The most common bone disease affecting the aging population is osteoporosis, a disease in which bone resorption exceeds formation. Because the OC is responsible for bone resorption, it has been the focus of anti-osteoporosis therapies, and the most commonly used class of drugs is the nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. These drugs target FPP synthase, an enzyme in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway required for the post-translational modification of small GTPases (including Rho, Rac, and cdc42) which allows their membrane insertion. Because appropriate localization at the membrane is critical for these small GTPases, which themselves are required for regulation of the OC cytoskeleton, bisphosphonates disrupt the OC cytoskeleton and reduce resorptive activity. Thus, the machinery of OC motility is an effective therapeutic target, and a better understanding of this complex process may contribute to even more effective treatments. One area that is still understudied is the motion of OC on bone, especially in vivo. Hopefully, advances in in vivo microscopy will provide insights into the activity of the OC in its natural environment.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arias-Salgado EG, Lizano S, Sarkar S, Brugge JS, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ. Src kinase activation by direct interaction with the integrin β cytoplasmic domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13298–13302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336149100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong AP, Tometsko ME, Glaccum M, Sutherland CL, Cosman D, Dougall WC. A RANK/TRAF6-dependent signal transduction pathway is essential for osteoclast cytoskeletal organization and resorptive function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44347–44356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettiger D, Huber F, Lynch L, Blystone S. Activation of alpha(v)beta3-vitronectin binding is a multistage process in which increases in bond strength are dependent on Y747 and Y759 in the cytoplasmic domain of beta3. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1227–1237. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess TL, Qian Y, Kaufman S, Ring BD, Van G, Capparelli C, Kelley M, Hsu H, Boyle WJ, Dunstan CR, Hu S, Lacey DL. The ligand for osteoprotegerin (OPGL) directly activates mature osteoclasts. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:527–538. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.3.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calle Y, Jones GE, Jagger C, Fuller K, Blundell MP, Chow J, Chambers T, Thrasher AJ. WASp deficiency in mice results in failure to form osteoclast sealing zones and defects in bone resorption. Blood. 2004;103:3552–3561. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabadel A, Banon-Rodriguez I, Cluet D, Rudkin BB, Wehrle-Haller B, Genot E, Jurdic P, Anton IM, Saltel F. CD44 and beta3 integrin organize two functionally distinct actin-based domains in osteoclasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4899–4910. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chellaiah MA. Regulation of actin ring formation by rho GTPases in osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32930–32943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiusaroli R, Sanjay A, Henriksen K, Engsig MT, Horne WC, Gu H, Baron R. Deletion of the gene encoding c-Cbl alters the ability of osteoclasts to migrate, delaying resorption and ossification of cartilage during the development of long bones. Dev Biol. 2003;261:537–547. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M. TREMs in the immune system and beyond. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:445–453. doi: 10.1038/nri1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxon FP, Taylor A. Vesicular trafficking in osteoclasts. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:424–433. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destaing O, Saltel F, Geminard JC, Jurdic P, Bard F. Podosomes Display Actin Turnover and Dynamic Self-Organization in Osteoclasts Expressing Actin-Green Fluorescent Protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:407–416. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destaing O, Saltel F, Gilquin B, Chabadel A, Khochbin S, Ory S, Jurdic P. A novel Rho-mDia2-HDAC6 pathway controls podosome patterning through microtubule acetylation in osteoclasts. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2901–2911. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Destaing O, Sanjay A, Itzstein C, Horne WC, Toomre D, De Camilli P, Baron R. The tyrosine kinase activity of c-Src regulates actin dynamics and organization of podosomes in osteoclasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:394–404. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsegood CL, Zhuo Y, Wesolowski GA, Hamilton JA, Rodan GA, Duong le T. M-CSF induces the stable interaction of cFms with alphaVbeta3 integrin in osteoclasts. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1518–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epple H, Cremasco V, Zhang K, Mao D, Longmore GD, Faccio R. Phospholipase Cgamma2 modulates integrin signaling in the osteoclast by affecting the localization and activation of Src kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3610–3622. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00259-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccio R, Grano M, Colucci S, Villa A, Giannelli G, Quaranta V, Zallone A. Localization and possible role of two different αvβ3 integrin conformations in resting and resorbing osteoclasts. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2919–2929. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.14.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccio R, Novack DV, Zallone A, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. Dynamic changes in the osteoclast cytoskeleton in response to growth factors and cell attachment are controlled by β3 integrin. J Cell Biol. 2003a;162:499–509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccio R, Zou W, Colaianni G, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. High dose M-CSF partially rescues the Dap12-/- osteoclast phenotype. J Cell Biochem. 2003b;90:871–883. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccio R, Teitelbaum SL, Fujikawa K, Chappel J, Zallone A, Tybulewicz VL, Ross FP, Swat W. Vav3 regulates osteoclast function and bone mass. Nat Med. 2005;11:284–290. doi: 10.1038/nm1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccio R, Takeshita S, Colaianni G, Chappel JC, Zallone A, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. M-CSF regulates the cytoskeleton via recruitment of a multimeric signaling complex to c-Fms Tyr-Y559/697/721. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18991–18999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610937200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Novack DV, Faccio R, Ory DS, Aya K, Boyer MI, McHugh KP, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. A Glanzmann's mutation in β3 integrin specifically impairs osteoclast function. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1137–1144. doi: 10.1172/JCI12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JE, Caulfield MP, Sato M, Quartuccio HA, Gould RJ, Garsky VM, Rodan GA, Rosenblatt M. Inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption in vivo by echistatin, an “arginyl-glycyl-aspartyl” (RGD)-containing protein. Endocrinology. 1993;132:1411–1413. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.3.8440195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frattini A, Orchard PJ, Sobacchi C, Giliani S, Abinun M, Mattsson JP, Keeling DJ, Andersson AK, Wallbrandt P, Zecca L, Notarangelo LD, Vezzoni P, Villa A. Defects in TCIRG1 subunit of the vacuolar proton pump are responsible for a subset of human autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. Nat Genet. 2000;25:343–346. doi: 10.1038/77131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Hikita A, Wakeyama H, Akiyama T, Oda H, Nakamura K, Tanaka S. Regulation of Osteoclast Apoptosis and Motility by Small GTPase Binding Protein Rac1. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2245–2253. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller K, Owens JM, Jagger CJ, Wilson A, Moss R, Chambers TJ. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates survival and chemotactic behavior in isolated osteoclasts. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1733–1744. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Henn H, Destaing O, Sims NA, Aoki K, Alles N, Neff L, Sanjay A, Bruzzaniti A, De Camilli P, Baron R, Schlessinger J. Defective microtubule-dependent podosome organization in osteoclasts leads to increased bone density in Pyk2 / mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1053–1064. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey A, Chen Y, Paliwal I, Carlberg K, Insogna K. Evidence for a functional association between phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and c-src in the spreading response of osteoclasts to colony-stimulating factor-1. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2129–2138. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakola HP. Neuropsychiatric and genetic aspects of a new hereditary disease characterized by progressive dementia and lipomembranous polycystic osteodysplasia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1972;232:1–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda S, Tomiyama Y, Pelletier AJ, Annis D, Honda Y, Orchekowski R, Ruggeri Z, Kunicki TJ. Topography of ligand-inducing binding sites, including a novel cation-sensitive epitope (AP5) at the amino terminus, of the human integrin β3 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11947–11954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton MA, Taylor ML, Arnett TR, Helfrich MH. Arg-gly-asp (RGD) peptides and the anti-vitronectin receptor antibody 23C6 inhibit dentine resorption and cell spreading by osteoclasts. Exp Cell Res. 1991;195:368–375. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton MA, Massey HM, Rosenberg N, Nicholls B, Seligsohn U, Flanagan AM. Upregulation of osteoclast α2β1 integrin compensates for lack of αvβ3 vitronectin receptor in Iraqi-Jewish-type Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:950–957. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt NP, Cunningham SJ, Adnan N, Harris M. The dental, craniofacial, and biochemical features of pyknodysostosis: a report of three new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:497–504. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90722-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst IR, Zuo J, Jiang J, Holliday LS. Actin-related protein 2/3 complex is required for actin ring formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:499–506. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda A, Chang KT, Matsumoto Y, Furuhata Y, Nishihara M, Sasaki F, Takahashi M. Obesity and insulin resistance in human growth hormone transgenic rats. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3057–3063. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda F, Nishimura R, Matsubara T, Tanaka S, Inoue J, Reddy SV, Hata K, Yamashita K, Hiraga T, Watanabe T, Kukita T, Yoshioka K, Rao A, Yoneda T. Critical roles of c-Jun signaling in regulation of NFAT family and RANKL-regulated osteoclast differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:475–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI19657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insogna KL, Sahni M, Grey AB, Tanaka S, Horne WC, Neff L, Mitnick M, Levy JB, Baron R. Colony-stimulating factor-1 induces cytoskeletal reorganization and c-src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of selected cellular proteins in rodent osteoclasts. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2476–2485. doi: 10.1172/JCI119790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Zheng Y, Johnson JF, Yang L, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP, Zhao H. The Small GTPase cdc42 Enhances Osteoclastogenesis and Bone Resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:S42. [Google Scholar]

- Jakus Z, Fodor S, Abram CL, Lowell CA, Mocsai A. Immunoreceptor-like signaling by beta 2 and beta 3 integrins. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GE, Zicha D, Dunn GA, Blundell M, Thrasher A. Restoration of podosomes and chemotaxis in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome macrophages following induced expression of WASp. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:806–815. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GE, Prigmore E, Calvez R, Hogan C, Dunn GA, Hirsch E, Wymann MP, Ridley AJ. Requirement for PI 3-kinase [gamma] in macrophage migration to MCP-1 and CSF-1. Exp Cell Res. 2003;290:120–131. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurdic P, Saltel F, Chabadel A, Destaing O. Podosome and sealing zone: specificity of the osteoclast model. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaifu T, Nakahara J, Inui M, Mishima K, Momiyama T, Kaji M, Sugahara A, Koito H, Ujike-Asai A, Nakamura A, Kanazawa K, Tan-Takeuchi K, Iwasaki K, Yokoyama WM, Kudo A, Fujiwara M, Asou H, Takai T. Osteopetrosis and thalamic hypomyelinosis with synaptic degeneration in DAP12-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:323–332. doi: 10.1172/JCI16923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Choi HK, Shin JH, Kim KH, Huh JY, Lee SA, Ko CY, Kim HS, Shin HI, Lee HJ, Jeong D, Kim N, Choi Y, Lee SY. Selective inhibition of RANK blocks osteoclast maturation and function and prevents bone loss in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:813–825. doi: 10.1172/JCI36809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lee SH, Kim JH, Choi Y, Kim N. NFATc1 induces osteoclast fusion via up-regulation of Atp6v0d2 and DC-STAMP. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:176–185. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga T, Inui M, Inoue K, Kim S, Suematsu A, Kobayashi E, Iwata T, Ohnishi H, Matozaki T, Kodama T, taniguchi T, Takayanagi H, Takai T. Costimulatory signals mediated by the ITAM motif cooperate with RANKL for bone homeostasis. Nature. 2004;428:758–763. doi: 10.1038/nature02444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T, Takahashi K, Kohara N, Takahashi Y, Hayashi S, Takahashi H, Matsuo H, Yamazaki M, Inoue K, Miyamoto K, Yamamura T. Heterogeneity of presenile dementia with bone cysts (Nasu-Hakola disease): Three genetic forms. Neurology. 2002;59:1105–1107. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornak U, Kasper D, Bosl MR, Kaiser E, Schweizer M, Schulz A, Friedrich W, Delling G, Jentsch TJ. Loss of the ClC-7 chloride channel leads to osteopetrosis in mice and man. Cell. 2001;104:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, Hsu H, Sullivan J, Hawkins N, Davy E, Capparelli C, Eli A, Qian YX, Kaufman S, Sarosi I, Shalhoub V, Senaldi G, Guo J, Delaney J, Boyle WJ. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93:165–176. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakkakorpi PT, Bett AJ, Lipfert L, Rodan GA, Duong LT. PYK2 Autophosphorylation, but Not Kinase Activity, Is Necessary for Adhesion-induced Association with c-Src, Osteoclast Spreading, and Bone Resorption. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11502–11512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier LL, Bakker ABH. The ITAM-bearing transmembrane adaptor DAP12 in lymphoid and myeloid cell function. Immunol Today. 2000;21:611–614. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01745-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Palmitoylation: policing protein stability and traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:74–84. doi: 10.1038/nrm2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder S, Nelson D, Weiss M, Aepfelbacher M. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein regulates podosomes in primary human macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9648–9653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder S, Aepfelbacher M. Podosomes: adhesion hot-spots of invasive cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:376–385. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luxenburg C, Geblinger D, Klein E, Anderson K, Hanein D, Geiger B, Addadi L. The architecture of the adhesive apparatus of cultured osteoclasts: from podosome formation to sealing zone assembly. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maa MC, Wilson LK, Moyers JS, Vines RR, Parsons JT, Parsons SJ. Identification and characterization of a cytoskeleton-associated, epidermal growth factor sensitive pp60c-src substrate. Oncogene. 1992;7:2429–2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao D, Epple H, Uthgenannt B, Novack DV, Faccio R. PLCγ2 regulates osteoclastogenesis via its interaction with ITAM proteins and GAB2. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2869–2879. doi: 10.1172/JCI28775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchisio PC, Bergui L, Corbascio GC, Cremona O, D'Urso N, Schena M, Tesio L, Caligaris-Cappio F. Vinculin, talin, and integrins and localized at specific adhesion sites of malignant B lymphocytes. Blood. 1988;72:830–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama A, Shimazu T, Sumida Y, Saito A, Yoshimatsu Y, Seigneurin-Berny D, Osada H, Komatsu Y, Nishino N, Khochbin S, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. In vivo destabilization of dynamic microtubules by HDAC6-mediated deacetylation. EMBO J. 2002;21:6820–6831. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh KP, Hodivala-Dilke K, Zheng MH, Namba N, Lam J, Novack D, Feng X, Ross FP, Hynes RO, Teitelbaum SL. Mice lacking β3 integrins are osteosclerotic because of dysfunctional osteoclasts. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:433–440. doi: 10.1172/JCI8905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVicar DW, Taylor LS, Gosselin P, Willette-Brown J, Mikhael AI, Geahlen RL, Nakamura MC, Linnemeyer P, Seaman WE, Anderson SK, Ortaldo JR, Mason LH. DAP12-mediated Signal Transduction in Natural Killer Cells. A DOMINANT ROLE FOR THE Syk PROTEIN-TYROSINE KINASE. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32934–32942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocsai A, Humphrey MB, Van Ziffle JA, Hu Y, Burghardt A, Spusta SC, Majumdar S, Lanier LL, Lowell CA, Nakamura MC. The immunomodulatory adapter proteins DAP12 and Fc receptor gamma-chain (FcRgamma) regulate development of functional osteoclasts through the Syk tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6158–6163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401602101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura I, Lipfert L, Rodan GA, Duong LT. Convergence of αvβ3 integrin- and macrophage colony stimulating factor-mediated signals on phospholipase Cgamma in prefusion ostelclasts. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:361–373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novack DV, Teitelbaum SL. The osteoclast: friend or foe? Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:457–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff M, Jurdic P. Podosomes in osteoclast-like cells: structural analysis and cooperative roles of paxillin, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) and integrin αvβ3. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2775–2786. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley FJ, Stanley ER. CSF-1 regulation of the wandering macrophage: complexity in action. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Vinogradova O, Plow EF. Integrin Bidirectional Signaling: A Molecular View. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:726–729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi R, Ma L, Miki H, Lopez M, Kirchhausen T, Takenawa T, Kirschner MW. The interaction between N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex links Cdc42-dependent signals to actin assembly. Cell. 1999;97:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. αvβ3 and macrophage colony-stimulating factor: partners in osteoclast biology. Immunol Rev. 2005;208:88–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saftig P, Hunziker E, Wehmeyer O, Jones S, Boyde A, Rommerskirch W, Moritz JD, Schu P, von Figura K. Impaired osteoclastic bone resorption leads to osteopetrosis in cathepsin-K-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13453–13458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltel F, Chabadel A, Bonnelye E, Jurdic P. Actin cytoskeletal organisation in osteoclasts: a model to decipher transmigration and matrix degradation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjay A, Houghton A, Neff L, DiDomenico E, Bardelay C, Antoine E, Levy J, Gailit J, Bowtell D, Horne WC, Baron R. Cbl associates with Pyk2 and Src to regulate Src kinase activity, alpha(v)beta(3) integrin-mediated signaling, cell adhesion, and osteoclast motility. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:181–195. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P, Montgomery C, Geske R, Bradley A. Targeted disruption of the c-src proto-oncogene leads to osteopetrosis in mice. Cell. 1991;64:693–702. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90499-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Buki KG, Ettala O, Vaaraniemi JP, Vaananen HK. Possible role of direct Rac1-Rab7 interaction in ruffled border formation of osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32356–32361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi J, Petre B, Walz T, Springer T. Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell. 2002;110:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani S, Faccio R, Chandrasekar I, Ross FP, Cooper JA. Cortactin has an essential and specific role in osteoclast actin assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2882–2895. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello E, Olcese L, Vely F, Geourgeon C, Blery M, Moqrich A, Gautheret D, Djabali M, Mattei MG, Vivier E. Gene Structure, Expression Pattern, and Biological Activity of Mouse Killer Cell Activating Receptor-associated Protein (KARAP)/DAP-12. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34115–34119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurukai T, Udagawa N, Matsuzaki K, Takahashi N, Suda T. Roles of macrophage-colony stimulating factor and osteoclast differentiation factor in osteoclastogenesis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2000;18:177–184. doi: 10.1007/s007740070018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaira S, Alhawagri M, Anwisye I, Kitaura H, Faccio R, Novack DV. RelA/p65 promotes osteoclast differentiation by blocking a RANKL-induced apoptotic JNK pathway in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008a;118:2088–2097. doi: 10.1172/JCI33392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaira S, Johnson T, Hirbe AC, Alhawagri M, Anwisye I, Sammut B, O'Neal J, Zou W, Weilbaecher KN, Faccio R, Novack DV. RelB is the NF-kappaB subunit downstream of NIK responsible for osteoclast differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008b;105:3897–3902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708576105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Lebowitz D, Sun C, Thang H, Grynpas MD, Glogauer M. Identifying the relative contributions of Rac1 and Rac2 to osteoclastogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:260–270. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells CM, Walmsley M, Ooi S, Tybulewicz V, Ridley AJ. Rac1-deficient macrophages exhibit defects in cell spreading and membrane ruffling but not migration. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1259–1268. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi M, Miyamoto T, Sawatani Y, Iwamoto K, Hosogane N, Fujita N, Morita K, Ninomiya K, Suzuki T, Miyamoto K, Oike Y, Takeya M, Toyama Y, Suda T. DC-STAMP is essential for cell-cell fusion in osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:345–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi M, Ninomiya K, Fujita N, Suzuki T, Iwasaki R, Morita K, Hosogane N, Matsuo K, Toyama Y, Suda T, Miyamoto T. Induction of DC-STAMP by Alternative Activation and Downstream Signaling Mechanisms. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:992–1001. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi A, Kim C, Li S, Marchal CC, Towe J, Atkinson SJ, Dinauer MC. Rac2-deficient murine macrophages have selective defects in superoxide production and phagocytosis of opsonized particles. J Immunol. 2004;173:5971–5979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Chen S, Zhang Y, Li X, Li Y, Wu X, Yuan J, Robling AG, Kapur R, Chan RJ, Yang FC. Rac1 mediates the osteoclast gains-in-function induced by haploinsufficiency of Nf1. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:936–948. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarali N, Fisgin T, Duru F, Kara A. Osteopetrosis and Glanzmann's thrombasthenia in a child. Ann Hematol. 2003;82:254–256. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0571-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Mochizuki S, Tomoyasu A, Yano K, Goto M, Murakami A, Tsuda E, Morinaga T, Higashio K, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Suda T. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeatman TJ. A renaissance for SRC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:470–480. doi: 10.1038/nrc1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambonin-Zallone A, Teti A, Grano M, Rubinacci A, Abbadini M, Gaboli M, Marchisio PC. Immunocytochemical distribution of extracellular matrix receptors in human osteoclasts: A β3 integrin is colocalized with vinculin and talin in the podosomes of osteoclastoma giant cells. Exp Cell Res. 1989;182:645–652. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(89)90266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Kitaura H, Reeve J, Long F, Tybulewicz VLJ, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. Syk, c-Src, the αvβ3 integrin, and ITAM immunoreceptors, in concert, regulate osteoclastic bone resorption. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:877–888. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W, Reeve JL, Liu Y, Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. DAP12 couples c-Fms activation to the osteoclast cytoskeleton by recruitment of Syk. Mol Cell. 2008;31:422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]