Abstract

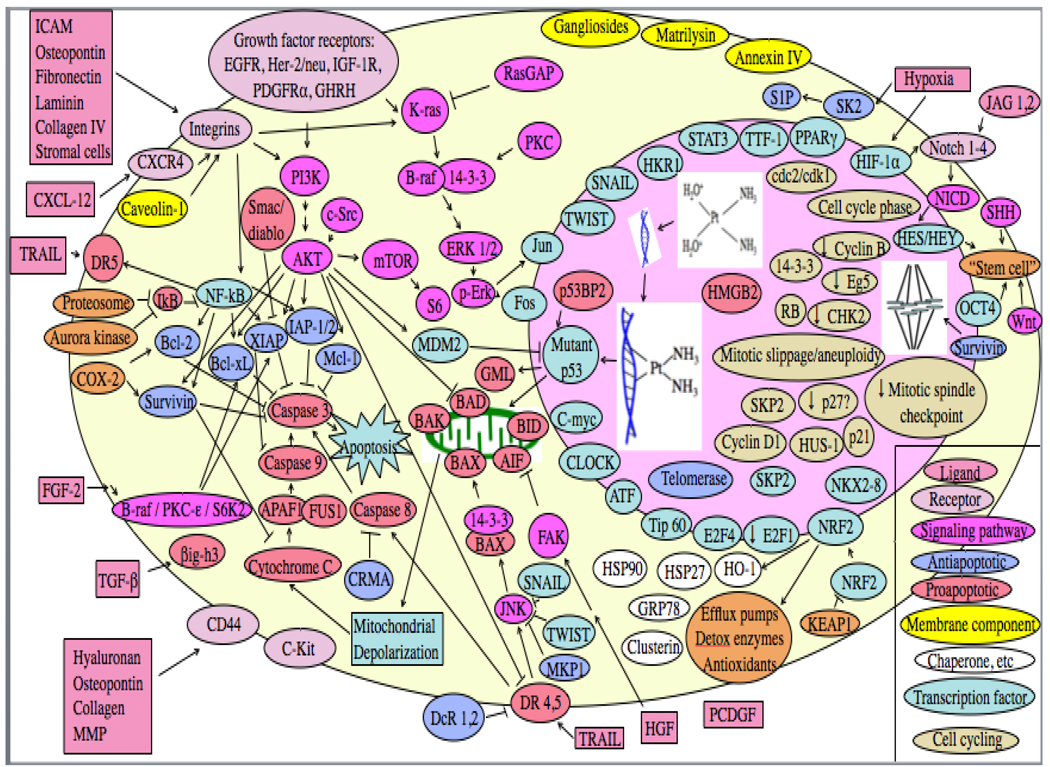

While chemotherapy provides useful palliation, advanced lung cancer remains incurable since those tumors that are initially sensitive to therapy rapidly develop acquired resistance. Resistance may arise from impaired drug delivery, extracellular factors, decreased drug uptake into tumor cells, increased drug efflux, drug inactivation by detoxifying factors, decreased drug activation or binding to target, altered target, increased damage repair, tolerance of damage, decreased proapoptotic factors, increased antiapoptotic factors, or altered cell cycling or transcription factors. Factors for which there is now substantial clinical evidence of a link to small cell lung cancer (SCLC) resistance to chemotherapy include MRP (for platinum-based combination chemotherapy) and MDR1/P-gp (for non-platinum agents). SPECT MIBI and Tc-TF scanning appears to predict chemotherapy benefit in SCLC. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the strongest clinical evidence is for taxane resistance with elevated expression or mutation of class III β-tubulin (and possibly α tubulin), platinum resistance and expression of ERCC1 or BCRP, gemcitabine resistance and RRM1 expression, and resistance to several agents and COX-2 expression (although COX-2 inhibitors have had minimal impact on drug efficacy clinically). Tumors expressing high BRCA1 may have increased resistance to platinums but increased sensitivity to taxanes. Limited early clinical data suggest that chemotherapy resistance in NSCLC may also be increased with decreased expression of cyclin B1 or of Eg5, or with increased expression of ICAM, matrilysin, osteopontin, DDH, survivin, PCDGF, caveolin-1, p21WAF1/CIP1, or 14-3-3sigma, and that IGF-1R inhibitors may increase efficacy of chemotherapy, particularly in squamous cell carcinomas. Equivocal data (with some positive studies but other negative studies) suggest that NSCLC tumors with some EGFR mutations may have increased sensitivity to chemotherapy, while K-ras mutations and expression of GST-pi, RB or p27kip1 may possibly confer resistance. While limited clinical data suggest that p53 mutations are associated with resistance to platinum-based therapies in NSCLC, data on p53 IHC positivity are equivocal. To date, resistance-modulating strategies have generally not proven clinically useful in lung cancer, although small randomized trials suggest a modest benefit of verapamil and related agents in NSCLC.

Keywords: lung cancer, chemotherapy, resistance

1.0 BACKGROUND

1.1 Lung cancer and resistance

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States and has a 5-year relative survival rate of only 16%1. Chemotherapy yields response rates of 20–50% in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and 60–80% in extensive small cell lung cancer (SCLC), but almost all tumors that are not intrinsically resistant rapidly develop acquired resistance, often with broad cross-resistance to other unrelated chemotherapy agents. Alternating chemotherapy agents with differing mechanisms of action does not overcome this resistance2.

1.2 Types of resistance

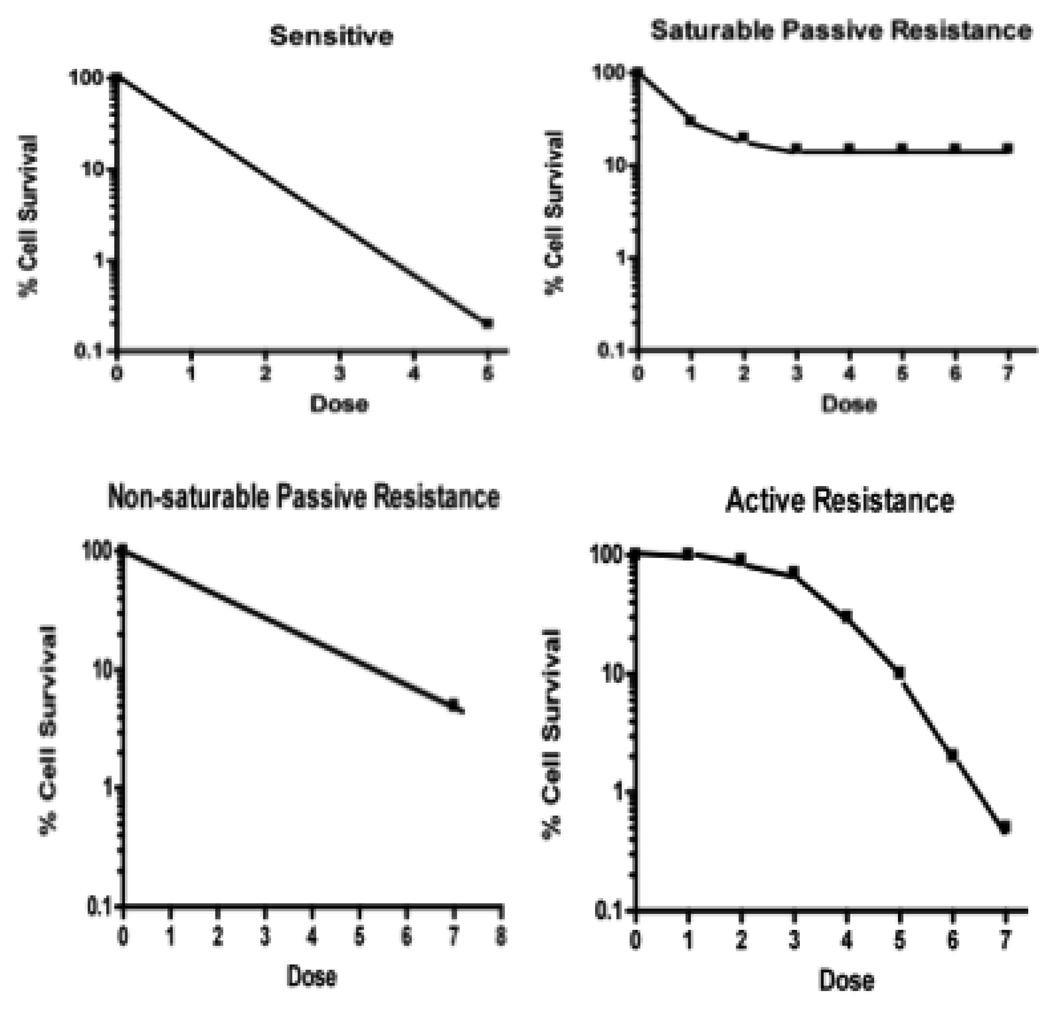

Resistance may be classified in several ways (Table 1). In addition to being intrinsic vs acquired, it may also be classified pharmacodynamically as “active” (due to excess of a resistance factor, analogous to competitive inhibition of drug effect) vs “non-saturable passive” (due to mutation or alteration of a factor, analogous to decreased affinity of a drug for its receptor) vs “saturable passive” (due to deficiency or saturation of a factor required for drug efficacy, analogous to non-competitive inhibition of drug effect)3. Just as dose-response curve shapes reflect whether drug inhibition is competitive vs non-competitive, they may also reflect the predominant type of resistance (Fig. 1)3. Dose response curve flattening at higher drug doses in NSCLC and the failure of bone marrow transplant approaches to impact other epithelial tumors suggests that the major reason for not being able to cure metastatic NSCLC and other epithelial tumors is due to saturable passive resistance (deficiency or saturation of factors required for drug efficacy)4.

Table 1.

Classification of resistance

| Classification Method | Types of resistance |

|---|---|

| Time of onset | Intrinsic (de novo) Acquired |

| Pharmacodynamic | Active (competitive inhibition) Non-saturable passive (decreased affinity) Saturable passive (non-competitive inhibition) |

| Kinetic | Quiescent Accelerated |

| Genetic | Mutation Epigenetic |

| Host vs tumor | Host factor Tumor factor |

| Cell involved | Tumor cell factor Microenvironment/stromal cell factor Abscopal effect of distant resistant tumor |

Fig 1.

Cell kill by first order kinetics gives a straight line in sensitive cells. Deficiency of a factor needed for tumor cell killing (“saturable passive resistance”) gives a terminal plateau on the dose-response curve, analogous to non-competitive inhibition of drug effect. Alteration or mutation of a factor (“non-saturable passive resistance”) results in a decreased dose-response curve slope (analogous to decreased affinity of a drug for its receptor). Excess of a mutation factor (“active resistance”) gives a shoulder on a dose-response curve, analogous to competitive inhibition of drug effect.

Resistance may also be classified as “quiescent” (due to lack of cell cycling through a sensitive cell cycle phase) vs “accelerated” (with treatment failure due to rapid repopulation after initial tumor cell killing). Resistance may be classified as genetic (due to selection of tumor cell subpopulations with mutations that render the cells resistant) or it may arise epigenetically (with rapid up-regulation or down-regulation of relevant genes). In genetic resistance, mutations could involve simple point mutations or could be associated with extensive chromosomal changes5 including aneuploidy6 or with amplification of resistance factors as a result of repeated chromosomal breakage-fusion-bridge cycles7. Epigenetic changes could arise due to alterations of DNA methylation8.

Resistance may also be classified as arising due to tumor cell characteristics or due to factors in the tumor environment. With few exceptions9, in vitro sensitivity testing in lung cancers has done well at predicting resistance with very few false negatives (ie, there have been few patients predicted to be resistant but who responded clinically), while false positives have been relatively common (predicted sensitive but failed clinically)10–15. Cases that are resistant clinically despite in vitro testing predicting sensitivity are potential examples of resistance arising from tumor environmental factors despite intrinsic sensitivity of the tumor cells.

More than one of these classifications may be relevant for a single resistance mechanism. For example, the broad down-regulation of membrane transporters reported previously in cisplatin-resistant hepatoma and cervical carcinoma cell lines16 would be an example of resistance that is both epigenetic and saturable passive. The development of reversible senescence17 and autophagy18 in response to chemotherapy exposure has characteristics of each of acquired, epigenetic, quiescent and saturable passive resistance. Clinically, quiescent tumor cells may survive the first cycle of chemotherapy, and surviving tumor cells may then undergo rapid epigenetic changes leading to enhanced resistance due to upregulation of active resistance mechanisms and to accelerated repopulation4. Alternatively, the epigenetic changes may lead to down-regulation of growth factors, transporters, etc, and saturable passive resistance associated with reversible quiescence4.

In preclinical models, a sensitive tumor may also be rendered resistant if a resistant tumor is implanted on the opposite flank19. While the mechanism of this effect is unknown, one might speculate that it is mediated through cytokines produced by the resistant tumor. Such cytokines could potentially directly impact characteristics of tumors located in other sites, or, alternatively they could have an indirect effect (eg, mediated by their stimulation of release of mesenchymal stem cells from the bone marrow20).

1.3 Resistance factors and normal tissues

Many putative cancer resistance factors are the same factors that normal cells use to protect themselves from oxygen radicals, ingested toxins, radiation, temperature extremes, and other components of a hostile environment. The dependence of normal tissues on these may explain in part our limited ability to successfully and safely counter them sufficiently with resistance modulators to augment sensitivity of tumors to therapy. Adding to the problem is the fact that multiple different resistance factors probably enter into play simultaneously21–23.

1.4 Cross-resistance

The problem is also magnified by the reality that factors that render a tumor resistant to one drug may also simultaneously increase resistance to several other agents. As a result, alternating up to 4 regimens2 or combining 6 chemotherapy agents24 with differing mechanisms of action in patients with NSCLC did not appear to improve outcome. In preclinical studies in lung cancer cell lines and xenografts, cross-resistance is seen frequently, but is not universal25–33. While there are no completely consistent patterns, there may be a higher probability of lack of lung cancer cross-resistance for platinums vs taxanes25, 27–29 or vs pemetrexed34, or for gemcitabine vs other agents26, 30, 33, 35, 36.

1.5 Implications of correlations of resistance with the host genotype

In addition to tumor cell characteristics being important, the observed relationship between chemotherapy-induced leukopenia and tumor response in SCLC37 and in NSCLC38 supports a role for host factors in treatment outcome. For example, patient genotype for various drug metabolism pathways could alter both drug efficacy and drug toxicity. We will not discuss these further in this paper, but several examples of these have been described in lung cancer patients39–41. However, we will discuss in later sections how host genotype for specific resistance factors impacts therapy outcome, and examples are presented in Table 2. Resistance to chemotherapy may correlate with a resistance factor’s gene copy number, gene mutation status, mRNA expression, or protein expression within a tumor, or with host genotype polymorphisms. Little work has been done to correlate host genotype polymorphisms with tumor expression of a gene, but genotype variations may lead to alteration of a factor’s enzymatic activity or protein stability or half-life. Hence, altered (increased or decreased) expression of a resistance or sensitivity factor in a tumor could result from increased or decreased production related to gene copy number or due to up-regulation or down-regulation in response to cellular factors, or it could be due to prolonged or shortened protein half-life due either to tumor gene mutations or due to the tumor inheriting from the host a specific gene factor polymorphism that prolongs or shortens the half-life of the gene product. Similarly, enzymatic activity of the protein could be increased or decreased due to tumor gene mutations or due to polymorphisms inherited from the host. Hence, for a specific factor that may be important in resistance, there could be lack of correlations of outcome with mRNA expression or protein expression because of mutations or polymorphisms that alter gene product half-life or activity. During tumorigenesis, oncogene mutations often drive tumor growth, and are selected for, but one might not expect to see selection for specific resistance factor mutations until after initiation of therapy; hence, host genotype polymorphisms might hypothetically be particularly likely to play a major role in intrinsic resistance, with a possibility of resistance factor mutation or gene amplification or deletion playing a bigger role in acquired resistance.

Table 2.

Resistance factors for which host gene polymorphisms correlate with resistance clinically

| Platinum regimens: |

| MRP2 |

| Glutathione-S-transferase-π |

| Other glutathione-related genes |

| ERCC1 |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum Ca |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum Da |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum G |

| XRCC1a |

| BRCA1 |

| NQO1 |

| P53 |

| Cyclin D1 |

| SHH |

| Gemcitabine: |

| Deoxycytidine deaminase |

| Irinotecan (with cisplatin): |

| MRP2 |

| Etoposide/vinorelbine (with cisplatin): |

| MDR1/P-glycoproteinb |

Data were negative or equivocal in some individual trials

No association with outcome in patients treated with cisplatin-docetaxel

1.6 Chemotherapy as “targeted” therapy

There is now substantial interest in “targeted therapies” for cancer, but chemotherapy agents may also be “targeted”. The fact that there is any selectivity of effect, with marked shrinkage of some tumors in response to chemotherapy, suggests the possibility that those tumors not only are deficient in resistance factors but that they also possess the target required for drug effect. We have traditionally thought of chemotherapy as simply targeting DNA, tubulin, topoisomerases, etc, but all normal cells also possess these, and the ability to selectively kill some (but not other) tumor cells suggests that the sensitive tumor cells may possess an additional target (or activating system, etc) required for sensitivity, and hence, resistance may arise from the absence or saturation of a required target, etc, rather than from the presence of a resistance factor. Dose-response curve flattening at higher drug doses would be in keeping with this. On the whole, we have not done a good job of searching for these hypothetical unique chemotherapy targets. In the past, the sensitivity of cells to chemotherapy has been attributed to rapid cell growth, but this does not explain things well. For example, cisplatin is active against many types of tumors and is toxic to cochlear hair cells, renal convoluted tubule cells, dorsal root ganglion neurons and gastrointestinal enterochromaffin cells but is not toxic to most rapidly dividing normal tissues.

While tumor type may be used to guide choice of agents (eg, pemetrexed was more effective in lung adenocarcinomas than was gemcitabine, while gemcitabine was more effective than pemetrexed against squamous cell carcinomas42), molecular characteristics are only infrequently used in choosing patients for clinical trials. We feel that it is important to raise the efficacy bar by putting substantially more effort into defining molecular determinants of sensitivity vs resistance43. Resistance modulators have generally had equivocal or negative effects in solid tumors. Modulators aimed at resistance factors such as efflux pumps might not be expected to make much of a difference if the tumor lacks a target, activating system, etc required for chemotherapy action.

Below we will discuss resistance to a variety of chemotherapy agents in lung cancer. Resistance mechanisms, agents affected and presence or absence of supporting clinical evidence is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Tumor factors contributing to lung cancer resistance to chemotherapy

| Factor | Agents affected preclinically | Clinical data support link to resistance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Decreased tumor blood flow: | |||

| ↓ Drug delivery | All? | Cisplatin combinations | |

| ↓ Oxygen delivery | Etoposide, paclitaxel (not cisplatin, topotecan) | ||

| ↑ sphingosine kinase 2 / sphingosine- 1-phosphate |

Etoposide | ||

| ↑ HIF-1α | Cisplatin, doxorubicin, paclitaxel | Cisplatin-gemcitabine | |

| ↑ VEGF | Cisplatin-gemcitabine | ||

| Alterations of tumor extracellular pH: | |||

| ↓ pH | Weak bases (doxorubicin, vinca alkaloids) | ||

| ↑ pH | Weak acids (platinums, alkylating agents) | ||

| Decreased drug uptake: | |||

| ↑ Cell membrane rigidity/sphingomyelin/cholesterol |

Platinums, etoposide, paclitaxel | ||

| ↓ Long chain/unsaturated fatty acids | Platinums | ||

| ↓ CTR1 | Platinums | ||

| ↓ Multiple membrane transporters | Platinums | ||

| ↓ Na+, K+ ATPase/ ↑ thromboxane A2/ ↑ sorbitol |

Platinums | Platinums a | |

| ↑ Intracellular chloride or zinc | Platinums | ||

| ↓ Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 |

Gemcitabine | Gemcitabinea | |

| ↓ Folate transporters | Pemetrexed | Pemetrexed | |

| Increased drug efflux: | |||

| ↑ MRP/GSH-conjugate pump | Platinumsa, anthracyclines, vincas, etoposide, taxanes, gemcitabinea |

Multiple platinum regimensa; vindesine + etoposide |

|

| ↑ MDR1/p-glycoproteinb | Anthracyclines, vincas, etoposide, taxanes | Multiple regimensa | |

| ↓ Connexin 32 | Vinorelbine | ||

| ↑ Breast cancer resistance protein | Platinum regimens | ||

| ↑ RLIP76/RALBP1 | Vinorelbine, doxorubicin | ||

| ↑ Lung resistance proteinc | Cisplatina, etoposidea | Platinum regimensa | Taxanes, CAV, some cisplatin regimens |

| ↑ P-type adenosine triphosphatase 7B | Cisplatin | ||

| Increased drug detoxification: | |||

| ↑ Glutathione (GSH) | Cisplatin, etoposidea, anthracyclinesa, vincasa, radiation, camptothecins, mitomycin, alkylating agents, methotrexate |

||

| ↑ Glutamate-cysteine ligase | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ GSH peroxidase/GSH reductase | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Glutathione-S-transferase-π | Cisplatina | Platinum regimensa | Vinorelbine regimens |

| ↑ Metallothioneins | Cisplatin, etoposide | Cisplatin-etoposide/CAV | |

| ↑ Dihydrodiol dehydrogenase | Cisplatin, doxorubicin, taxanesa, vincas, melphalan | ||

| ↑ Thymidine & folate pools | Pemetrexed | ||

| ↑ Peroxiredoxin V | Doxorubicin, etoposide | ||

| ↑ Deoxycytidine deaminase | Gemcitabine | ||

| Decreased drug activation or binding: | |||

| ↓ Deoxycytidine kinase activity | Gemcitabine | ||

| ↓ drug binding/ ↑ intracellular pH | Cisplatin | ||

| Increased, decreased or altered target: | |||

| ↑ Ribonucleotide reductase M1 | Gemcitabine | Gemcitabine regimens | Platinum + etoposide |

| ↑ Ribonucleotide reductase M2 | Gemcitabine + docetaxel | ||

| ↑ Folate pathway enzymes | Pemetrexed | ||

| ↓ Stathmin (oncoprotein 18) | Vincas | Cisplatin-vinorelbineg | |

| ↑/mutated III β tubulin (+/− α tubulin) | Taxanes, vincasa, cisplatin, doxorubicin, etoposide | Taxanes, cisplatin- vinorelbinea |

|

| ↑ histone deacetylase 6 (↑ tubulin staility) |

Taxanes | ||

| ↓ /mutated Topoisomerase II-α | Etoposide, anthracyclines | Etoposide | |

| ↑ Fragile histidine triad gene | Etoposide, camptothecins | ||

| Increased DNA damage repair: | |||

| ↑ Topoisomerase II-α | Cisplatin, radiation, vincas | Cisplatin regimens | |

| ↑ ERCC1 | Platinumsa | Platinum regimensa | Gemcitabine/docetaxel, gemcitabine/epirubicin |

| ↑ Xeroderma Pigmentosum A | Platinums | ||

| ↑ Rad23A | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Ribonucleotide reductase M1 | Gemcitabine, cisplatin | Gemcitabine regimens | Platinum + etoposide |

| ↑ Rad51 (homologous DNA repair) | Platinums, etoposide | Cisplatin + gemcitabine | |

| ↑ DNA-dependent protein kinase | Etoposide | ||

| ↑ Hus1 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ BRCA1 | Platinumsd | Cisplatin + gemcitabinea, cisplatin regimens |

Gemcitabine + epirubicin or docetaxeld |

| ↑ FANCD2 | Platinum regimens | ||

| ↑ apurinic/apyridinimic endonuclease | Cisplatin | Cisplatin regimens | |

| ↑ Eme1 endonuclease | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ PARP | Cisplatin, topotecan, temozolamide | ||

| ↓ High mobility group box 2 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↓ Fragile histidine triad gene | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Thymidylate synthase | Platinums | ||

| ↑ Dihdropyrimidine dehydrogenase | Platinums | ||

| Decreased apoptotic response: | |||

| ↓ DNA mismatch repair | Platinums | Platinum regimensa | |

| p53 mutation/ ↑ IHC expression | Cisplatin, etoposide, camptothecin, methotrexate, anthracyclines, radiation, taxanesa, others |

Platinum regimensa,c, CAV | Taxanes or vincas without platinums |

| ↓ p53-binding protein 2 | Cisplatin, radiation | ||

| ↓ GML protein | Cisplatin | Cisplatin | |

| ↓ Caspase-8 activity | Cisplatin, topotecan, radiation | ||

| ↓ Caspase-9 activity | Cisplatin | ||

| ↓ FUS1 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↓ SAPK/c-Jun N-terminal kinase | Platinums, gemcitabine | ||

| ↓ Bak, Bad, Bid | Cisplatin, etoposide, radiation, Fas ligand | Vinorelbine | |

| ↓ Baxa | Cisplatin, etoposide, taxanes, doxorubicin | Cisplatin regimens, Vinorelbine/docetaxel |

|

| ↓ Apoptosis signal transduction | Cisplatin, taxanes | ||

| ↓ ERK1/2 & MAPK/ERK kinase | Taxanesa, cisplatina | ||

| ↓ p-ERK | Gemcitabine | Platinum regimens, taxane regimens |

|

| ↓ βig-h3 | Etoposide | ||

| Increased Apoptosis Inhibitors: | |||

| ↑ Cyclooxygenase-2 | Cisplatin, anthracycline, etoposide, vinca, taxane, gemcitabine |

Carboplatinh, gemcitabineh, vinorelbinei, docetaxel |

|

| ↑ Bcl-2a,f | Cisplatin, camptothecin, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincas | Platinum regimens, vincas, taxanes, etoposide regimens |

|

| ↑ Bcl-xL | Cisplatin, gemcitabine, doxorubicin, vincas, taxanes, etoposide, others |

Vinorelbine | |

| ↑ Mcl-1 | Cisplatin, etoposide, taxanes, radiation | ||

| ↑ Survivin | Cisplatin, gemcitabine, taxanes | Cisplatin/etoposide | |

| ↑ Livin | Etoposide | ||

| ↑ XIAP | Cisplatin, etoposide | ||

| ↑ IAPs | Gemcitabine | ||

| ↑ Telomerase | Cisplatin, docetaxel, etoposide | ||

| ↑ TRAIL decoy receptors 1 & 2 | Doxorubicin, etoposide | ||

| ↑ Epidermal growth factor receptor (by IHC or gene copy number)j |

Cisplatina, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincas, taxanes, camptothecin, pemetrexed, gemcitabine, others |

Platinums, taxane, XRT, gemcitabine, vinorelbine |

|

| EGFR wild type vs exon 19 deletion | Platinum regimens | ||

| ↑ HER-2/neu (erbB-2, p185) | Cisplatin, etoposide, doxorubicin, taxanes, gemcitabinea,e |

Platinum regimensa | |

| ↑ IGF-1R | Platinums, etoposide, taxanes | Carboplatin/paclitaxel | |

| ↑ Attachment to ECM: integrins | Cisplatin, doxorubicin, taxanes, etoposide, others | ||

| ↑ Intercellular adhesion molecule | Cisplatin/paclitaxel | ||

| ↑ Osteopontin | Cisplatin | Carboplatin/paclitaxel | |

| ↑ Stromal-cell-derived factor- 1/CXCL12 |

Etoposide | ||

| ↑ Matrix metalloproteinase-7 (matrilysin) |

Platinum regimens | ||

| ↑ Hyaluronan/CD44 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Growth hormone releasing hormone | Taxanes | ||

| ↓ c-Kit | Cisplatin + etoposide | ||

| ↑ PDGFRα | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Hepatocyte growth factor | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Fibroblast growth factor 2 | Etoposide | ||

| ↑ PC cell-derived growth factor | Platinum regimens | ||

| ↑ PTEN/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway activation |

Cisplatin, etoposide, taxanes, gemcitabine, others | Platinum regimens, taxanes |

|

| ↑ p70S6K & S6 phosphorylation | Cisplatin | ||

| K-ras mutation | Taxanes | Platinum regimensa,j | |

| ↑ ERK1/2 | Etoposide, cisplatina, taxanesa | ||

| ↑ MAPK phosphatase-1 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ PKC-α | Platinumsa, vincas, taxanesa, doxorubicin, others | Cisplatin + gemcitabine | |

| ↓ PKC-β | Cisplatin, etoposide | ||

| ↑ PKC-δ | Etoposide, cisplatin | ||

| ↑ PKC-ε | Etoposide, doxorubicin | ||

| ↑ PKC-η | Platinumsa, vincas, taxanesa, doxorubicin, others | ||

| ↑ Caveolin-1/Caveolae organelles | Etoposide, paclitaxel | Gemcitabine/cisplatin, gemcitabine/epirubicin |

|

| Altered membrane gangliosides | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Annexin IV | Taxanes | ||

| ↑ c-Src | Amrubicin | ||

| ↑ Heat shock protein 90 | Taxanes | ||

| ↑ Heat shock protein 27 | Vinorelbinei | ||

| ↑ Clusterin | Paclitaxel, gemcitabine | ||

| ↑ Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 | Platinums, etoposide, doxorubicin | ||

| ↓ / mutated Keap1 | Platinums, etoposide, doxorubicin | ||

| ↑ Glucose-regulated protein 78 | Etoposide | ||

| Altered cell cycling: | |||

| Cell cycle phase | Varies with drug | ||

| Abnormal mitotic spindle checkpoint | Vinorelbine, taxanes | ||

| ↓ mitotic slippage/ ↓ aneuploidy | Taxanes | ||

| ↑ aneuploidy | Etoposide, topotecan, gemcitabine | ||

| ↓ CHK2 kinase | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ HUS1 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ RB/ ↓ pRB | Cisplatin, etoposide, taxanes, 5-FU | Cisplatin regimensa | |

| ↑ 14-3-3ζ | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ 14-3-3σ | Cisplatin + gemcitabine | ||

| ↑ p27Kip1 | Cisplatin regimensa | ||

| ↑ P21WAF1/CIP1 | Cisplatin, camptothecin, doxorubicin, etoposide | Platinum regimens | |

| ↑ SKP2 | Cisplatin, camptothecin, others | ||

| ↑ Cdc2/cdk1 | Platinum regimens | ||

| Cyclin D1 polymorphisms | Platinum regimens | ||

| ↓ Eg5 | Cisplatin + antimitotic agent |

||

| ↓ Cyclin B1 | Platinums + antimitotic agents |

||

| Increased transcription factors: | |||

| ↑ NF-κB | Cisplatin, doxorubicin a, etoposidea, gemcitabine, taxanes |

||

| ↑ Clock | Cisplatin, etoposide | ||

| ↑ Activating Transcription Factor 4 | Cisplatin, etoposide | ||

| ↑ HIV-1 Tat Interacting Protein 60 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ TWIST | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ SNAIL | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Kruppel-related zinc finger protein-1 (HKR-1) |

Cisplatin | Cisplatin | |

| ↑ STAT3 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ Thyroid Transcription Factor-1 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ NKX2–8 | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ PPARγ splice variant | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ c-myc | Cisplatin | ||

| ↑ E2F4/ ↓ E2F1 | Cisplatin, etoposide | ||

| ↑ Oct4 | Cisplatin | ||

| Stem cell markers and pathways | |||

| ↑ CD133 | Cisplatin, etoposide, doxorubicin, paclitaxel | Platinum regimens | |

| SHH polymorphisms | Cisplatin, carboplatin | Platinum regimens | |

| “Global” factors | |||

| Gene expression arrays | Cisplatin, taxanes, irinotecan, gemcitabine, vinorelbine | Cisplatin regimens, pemetrexed |

|

| Chromosomal alterations | Platinums, taxanes, etoposide, topotecan | ||

| DNA methylation | |||

| In vitro sensitivity | Platinums, vincas, taxanes, topo I & II inhibitors, gemcitabine, cyclophosphamide |

||

Data were not consistent, and were equivocal or negative in some studies

No association preclinically with resistance to platinums; may sensitize to gemcitabine

No association preclinically with resistance to anthracyclines, vinca alkaloids, bleomycin, irinotecan/SN-38

BRCA1 expression sensitized cells to antimicrotubule agents, and improved clinical outcome with gemcitabine + docetaxel

Paradoxical increase in sensitivity to gemcitabine-cisplatin combination in one preclinical study

Paradoxical increase in sensitivity to taxanes in some preclinical studies

Effect clinically was opposite to preclinical effect, with worse outcome in patients with tumors with high stathmin

Paradoxical increase in efficacy for patients with tumors positive for p53 by IHC

Trend present

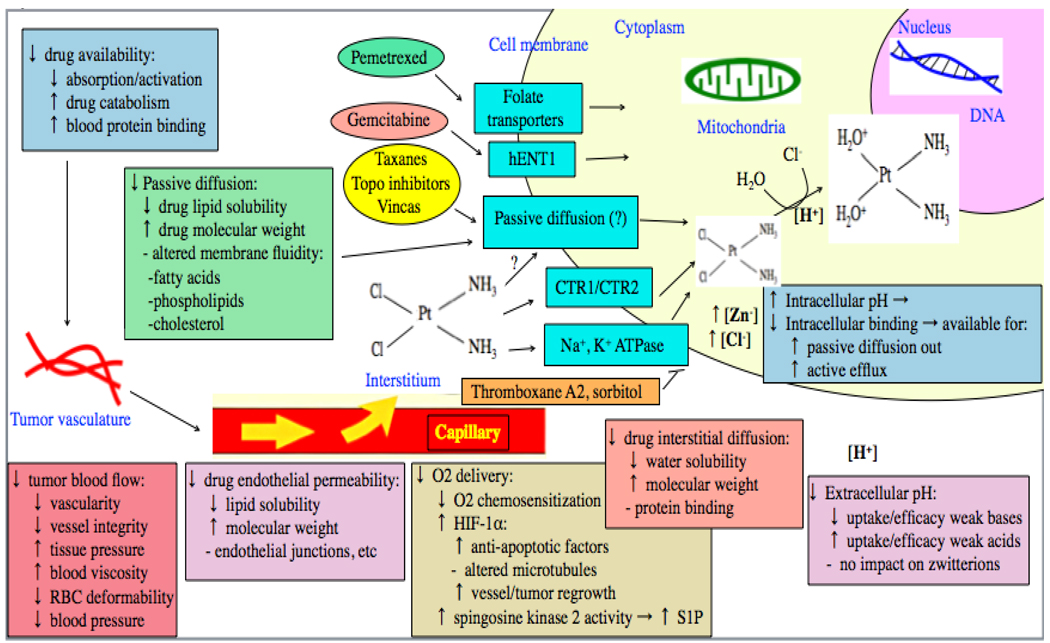

2.0 Drug and oxygen delivery (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Drug effect may be decreased by a decrease in drug bioavailability, hepatic activation, penetration across vessel endothelium or interstitium, uptake across cell membranes, or intracellular activation, or by decrease in tumor blood flow or oxygenation.

Drug concentrations achieved in tumor may conform to either a “flow-limited model” (proportional to tumor blood flow)44 or to a “membrane-limited model” (not proportional to blood flow and presumably limited by ability of the drug to cross cell membranes)45, 46. In a SCLC model, uptake of gemcitabine appeared to be flow-limited47, but correlation with tumor blood flow has not been adequately assessed in lung cancer for most drugs. A variety of observations suggest that delivery of cisplatin to tissues may be primarily membrane-limited48. As recently reviewed48, several factors associated with tumors may reduce tumor blood flow, including high tissue pressure, high blood viscosity (eg, due to fibrinogen), and decreased red blood cell membrane deformability. Due to impaired vascular autoregulation, tumor blood flow is more susceptible to blood pressure fluctuations than is blood flow to normal tissues49. As reviewed48, delivery of drugs such as cisplatin could also be reduced by rapid, irreversible binding to blood and extracellular proteins.

Factors limiting blood flow to tumor also secondarily reduce delivery of oxygen, and hypoxia has a variety of effects on therapy efficacy50. Some agents that are important in the treatment of lung cancer (eg, etoposide51 and paclitaxel52) are less effective in hypoxic tumor cells, while others (eg, topotecan53) are more effective in hypoxic tissues, and still others (eg, cisplatin53, 54) are equally effective in aerobic and hypoxic conditions. While hypoxia itself may not alter efficacy of some agents, cell exposure to hypoxia may activate anti-apoptotic signaling pathways that augment drug resistance51. For example, hypoxia activates sphingosine kinase 2, which in turn promotes the synthesis and release of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P)55. S1P then binds to S1P receptors, thereby activating p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase and protecting lung cancer cells from etoposide cytotoxicity55.

Hypoxia also leads to increased expression of hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), which in turn augments resistance of NSCLC cell lines to cisplatin56, doxorubicin56, and paclitaxel52, alters conformation and dynamics of microtubules52, and fosters tumor regrowth through stimulating angiogenesis by up-regulation of expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet derived growth factor (PDGF)57.

Clinically, in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with platinum-based regimens, there was no evidence that therapy efficacy was increased by the addition of any of pentoxifylline (which may improve blood flow by decreasing red blood cell membrane rigidity)58, tiripazamine (which sensitizes hypoxic tissues to therapy)59, or motexafin gadolinium (which increases the formation of superoxide and other reactive oxygen species in the presence of oxygen)60. Limited clinical data suggested possible benefit for NSCLC patients from addition of the hypoxic cell sensitizer metronidazole to doxorubicin, carmustine or mitomycin-C single agent chemotherapy, with responses in 4 of 8 patients61, although little efficacy was seen in NSCLC or other tumor types when metronidazole was added to epirubicin62, carboplatin63 or etoposide64 concurrently with multiple other potential resistance modulators including ketoconazole62–64, dipyridamole62–64, tamoxifen62–64, pentoxifylline63, novobiocin63 and cyclosporin62, 64. While administration of the vasodilator nitroglycerin prior to surgical removal of NSCLCs did reduce the rate of immunohistochemistry (IHC) positivity for HIF-1α and VEGF65, imaging studies using (18)F-Fluoromisonidazole (which concentrates in hypoxic tissues) suggested that the hypoxic cell fraction of primary NSCLC is low in humans, and there was no significant correlation between hypoxia and glucose metabolism as assessed by (18)F-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) scanning66. Furthermore, in operable NSCLC patients treated with neoadjuvant cisplatin-gemcitabine, HIF-1α mRNA in post chemotherapy resected specimens did not correlate with patient survival67, serum or plasma levels of VEGF did not correlate with survival in patients with advanced NSCLC receiving platinum-based chemotherapy alone68 or combined with tirapazamine69 or bevacizumab70, and tumor IHC expression of VEGF did not correlate with response or survival in advanced NSCLC patients treated with a variety of cisplatin-based combinations71. Overall, it remains unclear whether tumor blood flow and hypoxia-related factors play a major role in resistance of human lung cancers to chemotherapy.

In addition to trying to improve delivery of drugs and/or oxygen to tissues by manipulations that could alter blood flow, other strategies have also been tested. Liposome encapsulation of drug overcame resistance to cisplatin72, daunorubicin73 and vinorelbine74 in lung cancer cell lines. Howver, administration of liposomeencapsulated cisplatin75–77, docetaxel plus gemcitabine combined with liposomal doxorubicin78 or docetaxel plus liposomal doxorubicin plus radiotherapy79 to patients with NSCLC did not appear to augment efficacy in phase II trials, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin was inactive in recurrent SCLC80. Inhaled aerosolized liposomal cisplatin has also undergone phase I trials, but none of 16 patients experienced tumor regression81.

Drug administration via nanoparticles has also been tested. Preclinical studies suggested that cisplatin delivery via inhaled biotinylated-EGF-modified gelatin nanoparticles would improve delivery to EGFR-expressing tumor cells82, and a micellar nanoparticle formulation increased the ability of paclitaxel to radiosensitize lung cancer cell lines83. Nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (NAB-paclitaxel) reached higher tumor concentrations and was more active than cremophor-based paclitaxel in preclinical models that included lung cancer84. In a phase I/II trial of NAB-paclitaxel, the observed response rate of 30% was somewhat higher than what would be expected with standard taxane therapy85, and a phase II trial of NAB-paclitaxel with carboplatin and bevacizumab yielded a median survival time (16.8 months) which was longer than generally seen with advanced NSCLC86. Hence, while liposomal administration of drug did not appear to improve outcome, preliminary clinical data with nanoparticle administration are suggestive of possible enhancement of efficacy. Randomized phase III trials are ongoing to assess this further.

3.0 Extracellular pH

Extracellular pH (which may be manipulated by systemic administration of a glucose load, by medications such as amiloride or by bicarbonate87) may also be important (Fig. 2). Tumor extracellular pH is often acidic, while tumor intracellular pH is often neutral or alkaline. A low extracellular pH favors uptake into tumor cells and enhances cytotoxicity of weak acids such as cisplatin88 and alkylating agents89, while a higher extracellular pH favors uptake into tumor cells of weak bases such as doxorubicin89 and vinca alkaloids87, and has little net effect on zwitterions like paclitaxel89. Hence, both dietary factors and concurrent medications could potentially contribute to tumor resistance by altering tumor pH.

4.0 Drug uptake

Tumor uptake of some drugs is by passive diffusion, whereas other drugs enter cells by active transport or by a combination of active transport and passive diffusion (Fig.2).

4.1 Cisplatin

Reduced uptake of cisplatin has been noted in many resistant NSCLC32, 90–94 and SCLC32, 93, 95 cell lines, although it is not a universal finding. Cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cell lines with reduced platinum uptake have also been noted to have increased intracellular chloride96 or zinc content91, increased cell membrane rigidity97, increased sphingomyelin content97, and increased density of membrane lipid packing, with reduced long chain and unsaturated fatty acids98. These changes could potentially alter passive diffusion of cisplatin into cells or might reduce the activity of membrane transporters. Culturing cisplatin-resistant SCLC cells in long chain fatty acids (that were then incorporated into cell phospholipids) increased cisplatin cellular uptake and DNA binding, and reduced resistance99. Dipyridamole increased the concentration of both cisplatin and its active aquated species in cells through mechanisms that were uncertain100. However, when dipyridamole was added to high dose cisplatin in the treatment of chemonaive NSCLC, the response rate was only 14%, with a median survival time of 8 months, suggesting that clinical activity was not increased substantially101.

4.1.1 CTR1 and CTR2

Platinum-resistance may be associated with broad cross-resistance and with down-regulation of expression of a wide range of membrane transporters16. Platinums may be transported into cells by the copper transporter CTR1, and platinum resistance in lung cancer may be associated with decreased CTR1 expression102. A role for the related copper transporter CTR2 in platinum uptake has also been suggested in other tumor types103 but has not yet been assessed in lung cancer. Decreased CTR1 expression was noted in patients with a variety of malignancies who had been exposed to a wide range of chemotherapy and targeted agents within the previous 3 months104 suggesting that exposure to many types of drugs could lead to platinum resistance by down-regulating expression of CTR1104, 105.

4.1.2 Na+, K+ ATPase

Na+, K+ ATPase and agents that activate it are also associated with increased intracellular accumulation and/or efficacy of cisplatin, with the association being stronger in NSCLC than in SCLC cell lines106–108. Inhibition of factors (such as thromboxane A2108, 109) that antagonize Na+, K+ ATPase also increased cisplatin uptake and cytotoxicity. Inhibition of thromboxane A2 also resulted in upregulation of expression of interleukin-1β-converting enzyme, the expression of which is reduced in some platinum-resistant NSCLC cell lines109. Whether N+, K+ ATPase plays a direct role in cisplatin cellular uptake or whether it instead exerts an effect indirectly through alteration of intracellular pH110 or other mechanisms is unclear. In NSCLC cell lines, the glucose metabolite sorbitol decreased cisplatin cytotoxicity, Na+, K+-ATPase activity, and cisplatin uptake, suggesting a possible mechanism for cisplatin resistance in poorly controlled diabetes111.

Tumor retention of Thallium-201 (T201) on SPECT scanning may reflect Na+, K+ ATPase activity, and in one study in which SCLC patients were treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy, response correlated with pretreatment T201 retention112, but this was not noted in another study in which SCLC patients were treated with a broader spectrum of chemotherapy agents113, and no correlation between T201 retention and outcome was seen in NSCLC patients treated with mitomycin-vindesine-cisplatin114. Hence, it is unclear if T201 scanning is of any value in this setting.

4.2 Taxanes, vinca alkaloids and etoposide

There is relatively little information available on mechanisms by which taxanes, vinca alkaloids or etoposide enter cancer cells, nor on the potential role of decreased drug influx in resistance, although etoposide uptake is significantly higher in sensitive SCLC cell lines than in more resistant NSCLC lines115. The nonionic detergent Tween-80 augmented uptake and cytotoxicity of etoposide in NSCLC cell lines116, and some etoposide-resistant cell lines have greatly increased content of cholesterol117, which would increase cell membrane rigidity. Transfection into NSCLC cells of the human HERG K+ channel gene significantly increased the cytotoxicity of vincristine, paclitaxel and hydroxycamptothecin (but not cisplatin)118, but it is unknown if it plays any role in drug transport.

4.3 Gemcitabine

For gemcitabine, human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (hENT1) plays a role in cellular uptake, and hENT 1-deficient cells are resistant to gemcitabine119. A deficiency in hENT 1 may be more important in intrinsic than in acquired gemcitabine resistance120. Liposome encapsulation may augment gemcitabine uptake and efficacy121.

While pretreatment hENT-1 expression did not correlate with response or survival in one NSCLC study of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy in which only 16% expressed hENT 1 by IHC119, in another trial, no NSCLC patient in whom hENT 1 was absent by IHC responded to gemcitabine-based therapy122.

4.4 Pemetrexed

For the multitargeted antifolate pemetrexed, the proton-coupled folate receptor123, the reduced folate carrier123, 124 and the folate receptor-α125 all appear to play a role in cellular uptake, although they have not been extensively assessed in lung cancer. Pemetrexed is more active in lung adenocarcinomas than in squamous cell carcinomas clinically42, possibly related to the fact that adenocarcinomas have significantly higher expression of folate receptor-α and a strong trend towards increased expression of the reduced folate carrier compared to squamous cell carcinomas126.

Overall, low drug uptake may be an important cause of resistance, and uptake may vary with extracellular pH. With cisplatin, CTR1, Na+, K+ ATPase, and membrane fluidity may play a role in uptake and resistance, while hENT1 may play a role with gemcitabine and folate carriers may play a role with pemetrexed. Little is known regarding how other drugs enter cells.

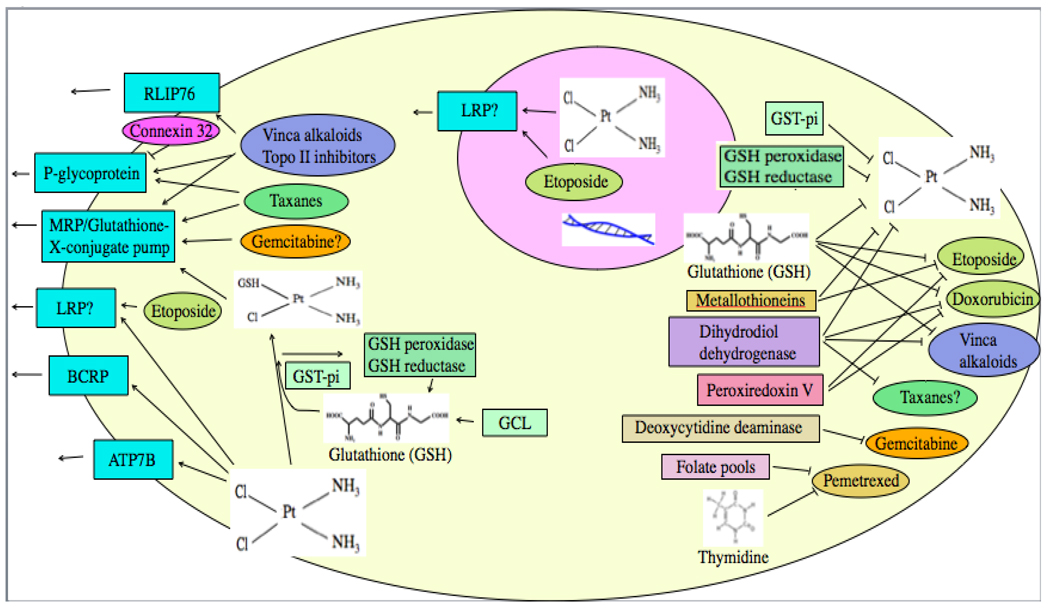

5.0 Drug efflux

More is known about the role of efflux (Fig. 3) than about the role of uptake in drug resistance. Various membrane efflux pumps have been assessed that may play a role in reducing drug intracellular concentrations.

Fig. 3.

Drug intracellular concentration may be decreased by efflux pumps, or drug may be detoxified by various factors.

5.1 Multidrug resistance protein (MRP)

A high proportion of SCLC127, 128 and NSCLC127, 129 cell lines express MRP mRNA, with greater MRP protein and/or mRNA expression in NSCLC than in SCLC cell lines130, 131. MRP expression is associated with decreased cellular drug accumulation of cisplatin95, paclitaxel132 and other agents133. In NSCLC heterotransplants in nude mice, there was a statistically non-significant trend toward a higher response rate to paclitaxel in MRP-negative tumors134. In both SCLC95, 127, 128, 130–132 and NSCLC29, 127, 129–133, 135 cell lines, MRP mRNA or protein expression correlated significantly with resistance to anthracyclines95, 127, 128, 130, 131, 133, 136 vinca alkaloids95, 129, 130, 133, 136, etoposide127, 130, 131, 136, docetaxel29, paclitaxel132, gemcitabine135 and cisplatin95, 130. However, an association between MRP expression and resistance was not seen in some cell lines137–139, and in some, MRP was not associated with resistance to cisplatin despite contributing to resistance to other agents127, 133. Paradoxically, in still other lines, resistance to gemcitabine was decreased instead of being increased by MRP1 expression139. Similarly, in another study, the anti-inflammatory agent indomethacin induced apoptosis preferentially in SCLC cells that were doxorubicin resistant and that overexpressed MRP1, and this apoptosis was decreased if MRP1 was inhibited by siRNA140

MRP1130, MRP3130, and MRP7129, 132 may be particularly important in resistance, with less of a role for MRP2129, 130 and MRP3129. The MRP7 inhibitor sulfin-pyrazone increased NSCLC cell line sensitivity to vinorelbine129. 5-Fluorouracil may sensitize cells to cisplatin by inhibiting MRP expression141, and verapamil may also modulate MRP effect131. Depleting cells of glutathione reversed resistance associated with MRP in one study, suggesting that MRP functions as a glutathione S-conjugate (“GS-X”) pump that exports molecules that are bound to glutathione136. Increased GS-X pump activity is associated with cisplatin resistance and decreased cellular cisplatin accumulation142.

MRP mRNA and/or protein by IHC was found in 32–100% of clinical NSCLC tumor specimens127, 143–145, but gene amplification has not been noted127. MRP expression was significantly higher in more differentiated tumors than in less differentiated tumors143, in squamous cell carcinomas than in other NSCLCs145, and in tumors with mutant p53144. MRP expression is also common in SCLC clinical tumor samples128.

There is not a consensus on whether tumor MRP expression correlates with clinical outcome, although tumor type and chemotherapy type may have a bearing on the relationship. In SCLC patients treated with platinum-based combinations, response rates were significantly lower for tumors that were IHC-positive vs −negative for MRP1146, 147 or MRP2148. After being taken up by cells, Tc-99m methoxyisobutyl isonitrile (MIBI) and technetium-99m tetrofosmin (Tc-TF) may be exported from cells by either MRP or by MDR1/p-glycoprotein, and retention of these compounds on SPECT scanning has been used clinically as an indicator of efflux pump activity. Higher tumor uptake of MIBI149 and Tc-TF150 on SPECT scanning was associated with better response to chemotherapy, and, in keeping with preclinical predictions, uptake of MIBI and Tc-TF correlated negatively with tumor MRP and MDR1 expression149–151). Furthermore, MRP1 expression in SCLC tumors was markedly increased at relapse after cisplatin-etoposide compared to chemonaive values146 or there was a strong trend towards an increase in MRP IHC positivity after treatment with etoposide or teniposide152, suggesting that chemotherapy exposure either upregulates expression of MRP or else selects for resistant, MRP-positive cells. Similarly, in autopsy NSCLC tumor tissues, mRNA expression levels of MRP3153 and MRP5154 (but not MRP4153) were significantly higher in patients who had been exposed to platinum drugs ante mortem than in patients who had not received platinum agents.

In advanced NSCLC, response rates to cisplatin plus irinotecan were higher and survival was longer in patients with some MRP2 host genotypes than with other genotypes155, tumor MRP2 (but not MRP1 or MRP3) IHC expression correlated with survival (but not with response) in patients treated with platinum-based combination chemotherapy156, and tumor MRP expression was associated with poor survival in patients treated with vindesine plus etoposide144, 145. However, in another NSCLC study, MRP mRNA expression only correlated inversely with response in lung adenocarcinoma, and not in squamous cell carcinoma157, there was no correlation between MRP IHC expression and response to platinum-based combinations in other studies156, 158, MIBI scanning did not correlate with response to chemotherapy in a study involving 14 NSCLC and 9 SCLC patients151, and tumor MRP1 or MRP2 IHC expression did not correlate with survival in patients with resected NSCLC receiving adjuvant cisplatin plus a vinca alkaloid or etoposide159.

Overall, preclinical data strongly support a role for MRP in resistance to several types of chemotherapy. Clinical observations suggest that MRP is probably associated with resistance to chemotherapy in SCLC. The clinical data remain less convincing in NSCLC, but are suggestive of a possible role for MRP in chemoresistance, and the increased MRP expression seen in treated NSCLC and SCLC tumors suggest the possibility that it may play a greater role in acquired than in intrinsic resistance.

5.2 MDR1/p-glycoprotein (P-gp)

Like MRP, P-gp may also render tumors resistant to chemotherapy by transporting drugs out of cells. In NSCLC cell lines, increased MDR1 mRNA and/or protein expression levels were associated with resistance to anthracyclines25, 160, 161, vinca alkaloids25, 129, 160–162, etoposide160, 161, and taxanes25, 160, 161, 163, 164. With occasional exceptions165, MDR1/P-gp expression did not correlate significantly with sensitivity to cisplatin25, 92, 137 or carboplatin160, nor with intracellular92, 137 or intranuclear137 cisplatin accumulation, and cisplatin and carboplatin may actually increase cellular concentrations of some other agents by inhibiting P-gp166. Increased expression of P-gp is also frequently seen in cell lines that are sensitive to cisplatin despite resistance to paclitaxel167. In addition, some NSCLC and SCLC cell lines transfected with the MDR1 gene had augmented sensitivity to gemcitabine, and this augmented sensitivity was reversed by the P-gp inhibitor verapamil139. MDR1 gene amplification was detected in some resistant lines25.

MDR1 gene overexpression was also seen in SCLC cell lines selected for resistance by exposure to paclitaxel132, anthracyclines33 or etoposide168, 169, although MDR1 mRNA expression was relatively uncommon in SCLC cell lines not selected for resistance128.

Some resistant lines that overexpress P-gp also overexpressed caveolin 1, and P-gp localized to caveolin-rich membrane domains in these cells117. P-gp expression correlated with HIF-1α expression in NSCLC cell lines170 and in resected NSCLC tumors65. P-gp expression was increased when lung adenocarcinoma cells were cultured in hypoxia170 and was reduced in tumors of patients who had nitroglycerin patches applied to improve tumor blood flow and oxygenation prior to surgical resection65.

Expression of Connexin 32 in a NSCLC cell line significantly potentiated vinorelbine-induced cytotoxicity and induction of apoptosis by down-regulating expression of MDR1162. Connexins are important in gap junctions and normally play a role in electrical signaling between cells.

Clinically, in chemonaive NSCLC patients, MDR1 mRNA and/or P-gp were expressed in 11–32% of surgical specimens152, 165, 171–173, but were expressed in 61% of tumors that had been treated with chemotherapy172. MDR1 expression in NSCLC did not correlate with histopathology or with clinical details171. In SCLC, MDR1 expression was seen in 13–60% of tumor biopsy samples128, 152, 173, and in 50% of SCLCs xenografted from treated and untreated patients into nude mice174.

With MDR1/P-gp, as with MRP, there is stronger evidence of an association of expression with outcome in SCLC than in NSCLC, so we will discuss SCLC first. In SCLC, there was a negative correlation between expression of P-gp and response146, 147, 149, 173, 175, 176 and/or survival176, 177 in patients treated with cisplatin-etoposide146, 147, 149, 173, 175, 176, cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-vincristine (CAV)173, 176, or other doxorubicin or etoposide regimens177, and P-gp expression was significantly increased in tumors previously exposed to therapy compared to pretreatment expression146, 152. Response of SCLC patients to cisplatin plus etoposide also correlated with MDR1 host polymorphisms, with a significantly better chemotherapy response in patients with the 3435 CC genotype (exon 26) compared with the combined 3435 CT and TT genotypes, and patients harboring the 2677G-3435C haplotype also responded significantly better than did other patients 178. Similarly there was a strong correlation between uptake of MIBI113, 149, 179 or Tc-TF150, 175, 180 on SPECT scanning and response of SCLC to cisplatin plus etoposide149, 150, 175, 179, 180 (EP), to EP plus doxorubicin181, and to CAV plus mitomycin-C and vindesine113, or there was a trend towards a correlation of response with MIBI182, 183. Patients with SCLC demonstrated significantly greater MIBI uptake than those with NSCLC184.

In NSCLC, there was a significant correlation of tumor P-gp IHC expression with response in 2 studies using paclitaxel and a platinum185, 186 and in one study using cisplatin, ifosfamide, vinblastine and radiation187, and P-gp expression also correlated inversely with survival in this latter study187. The MDR1 3435 CC host genotype was associated with a significantly better response to cisplatin-vinorelbine compared with the combined 3435 CT and TT genotypes, and patients with the 2677G-3435C haplotype also had significantly better responses to chemotherapy compared to patients with other haplotypes combined 188. In another NSCLC study, tumor MDR1 mRNA expression did correlate with shortened survival even though it did not correlate with response to chemotherapy157. In NSCLC, while tumor P-gp status did not correlate with MIBI uptake on SPECT scanning in some studies189, 190, it did correlate in other studies185, 191. Furthermore, MIBI114, 185, 190, 191 and Tc-TF192, 193 uptake on SPECT scanning correlated significantly with response to chemotherapy with cisplatin, mitomycin-C plus vindesine114, 190, with paclitaxel185, with paclitaxel-based regimens191, or with radiation combined with cisplatin plus etoposide193, and also correlated with survival190.

However, in a number of other studies involving patients with advanced156, 173, 194 or locally advanced195 NSCLC, P-gp expression by IHC did not correlate with response to cisplatin-based regimens156, 173, 194 or carboplatin-based regimens195 that also included vinca alkaloids156, 173, 195, irinotecan156, taxanes156, gemcitabine156 or radiation195, and host MDR1 C3435T polymorphisms did not correlate with outcome in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with docetaxel-cisplatin196 despite their association with efficacy of cisplatin-vinorelbine in another study, as noted above188. Similarly, preoperative MIBI uptake did not correlate with in vitro sensitivity (for etoposide, doxorubicin, vindesine, cyclophosphamide and cisplatin) of resected specimens189, nor with clinical response to chemotherapy151 in some studies.

P-gp antagonists have been assessed in both NSCLC and in SCLC. The P-gp antagonist verapamil augmented paclitaxel accumulation in human lung cancer cells overexpressing P-gp138, increased vinorelbine efficacy in NSCLC cell lines overexpressing MDR1129, and improved the efficacy of a cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and etoposide regimen against SCLC xenografts197. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor gefitinib also reversed P-gp mediated taxane resistance in NSCLC cell lines164, 198, but did not improve efficacy of chemotherapy in NSCLC in randomized clinical trials199, 200.

In a phase II clinical trial in which the P-gp antagonist cyclosporine A was added to paclitaxel in NSCLC patients (18 of whom had received one prior chemotherapy regimen and 8 of whom were chemonaive), the response rate was 26%, median time to progression was 3.5 months and median overall survival was 6 months, suggesting a possible modest beneficial impact of the cyclosporine on paclitaxel efficacy201. However, when cyclosporine was added to etoposide plus cisplatin as front line therapy in advanced NSCLC, there was no evidence of benefit, with a response rate of 22.7% and a 2-year survival rate of 8%, and better outcome in patients receiving a lower vs higher dose of cyclosporine202.

In a small randomized phase II trial with 54 NSCLC patients, addition of the P-gp antagonist dexverapamil to vindesine plus etoposide was associated with a response rate of 31.3 % compared to only 11.1 % for the chemotherapy alone203, and addition of verapamil to vindesine plus ifosfamide/mesna in a randomized study involving 72 NSCLC patients was associated with an increase in response rate from 18% to 41% (p=0.057) and the overall survival time was increased significantly (p=0.02). However the calcium channel blocker nifedipine (which reverses resistance to chemotherapy both through P-gp antagonism plus through other mechanisms, as previously reviewed204) plus the methylxanthine pentoxifylline did not reverse resistance to combination chemotherapy in previously-treated patients with NSCLC and other malignancies58. Similarly, while hydroxyurea is thought to reverse MDR1-associated resistance by breaking down double minute chromosomes carrying amplified MDR1205, the addition to paclitaxel of hydroxyurea in previously-treated patients with advanced NSCLC did not appear to improve outcome, with a response rate of only 3% and a median survival time of 4.6 months206.

In randomized clinical trials in SCLC, the P-gp modulator megestrol acetate did not improve outcome with chemotherapy207 and verapamil did not improve response or survival rates in patients receiving cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine plus etoposide208.

Based on the above, we can conclude that there is strong preclinical evidence of an association between MDR1/P-gp expression and resistance to several agents in lung cancer cell lines, but probably no increased resistance to platinum agents, and possible collateral sensitivity to gemcitabine. Clinically, there is relatively strong evidence of an association between MDR1/P-gp expression in SCLC and resistance to combination chemotherapy. The clinical evidence is inconclusive for an association with outcome in NSCLC. With respect to P-gp modulation, verapamil or dexverapamil may possibly increase chemotherapy efficacy in NSCLC, but other strategies have been ineffective, and neither verapamil nor megestrol helped in SCLC.

5.3 Lung Resistance Protein/Major Vault Protein (LRP)

Vaults are ribonucleoparticles involved in nuclear-cytoplasmic transport, cell signaling and immune responses, and LRP is a major component of vaults209. In some NSCLC cell lines, LRP expression correlated significantly with resistance to cisplatin210, 211 or etoposide212. However, in other NSCLC cell lines, resistance to cisplatin92, 137 and cisplatin intracellular concentration92, 137 did not correlate with LRP mRNA92, 137 and protein137 expression. LRP expression also did not correlate with resistance of NSCLC cell lines to anthracyclines210, 211, etoposide210, 211, 213, vinca alkaloids210, 211, bleomycin210, 211 or the irinotecan metabolite SN-38211.

In some clinical studies, NSCLC tumor LRP expression was associated with reduced response to platinum-based chemotherapy157, 172, 214. However, this association was only noted in squamous cell carcinomas in one study214, and in still other studies, there was no correlation with response to platinum-based chemotherapy (including platinum combinations with taxanes and epipodophyllotoxins158, 215) or to taxane-based chemotherapy216. Autopsy tumor LRP gene expression was not increased by prior platinum exposure217. Tumor LRP expression correlated with MRP expression in one NSCLC study157, but it did not correlate with MIBI191 or Tc-TF150, 192 uptake on SPECT scanning.

In SCLC, there was a statistically insignificant trend towards decreased response to CAV in patients whose tumors overexpressed LRP146, while in other studies, there was no apparent association between tumor LRP expression and response to CAV215 or with response to cisplatin plus etoposide147. Overall, there is no conclusive evidence that LRP plays a major role in resistance of lung cancer to chemotherapy.

5.4 P-type adenosine triphosphatase (ATP 7B)

As recently reviewed48, the copper transporter ATP 7B is thought to play a role in cisplatin efflux. While ATP 7B mRNA and IHC expression significantly correlated with cisplatin resistance in NSCLC xenografts218, it did not correlate with resistance in some lung cancer cell lines102. There is evidence of a link between ATP 7B expression and resistance to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in some other tumor types219, but data from clinical tumor specimens are not yet available for lung cancer. It remains uncertain whether ATP 7B is important in lung cancer resistance to chemotherapy.

5.5 Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP)

In advanced NSCLC patients undergoing platinum-based chemotherapy, tumor IHC expression of BCRP (a transporter and member of the ATP binding cassette family) was significantly associated with shortened survival in two studies156, 220, and blood BCRP concentrations were significantly higher in chemoresistant patients than in chemosensitive patients221. Tumor BCRP IHC expression correlated with lack of response in one study222, but not in another study220. Overall, the data suggest a possible role for BCRP in lung cancer chemotherapy resistance.

5.6 Ral-interacting protein (RLIP76) (RALBP1)

In NSCLC and SCLC cell lines, overexpression of the non-ABC glutathione-conjugate transporter RLIP76 (which is involved in receptor-ligand endocytosis and in multispecific drug transport) was associated with augmented efflux, decreased intracellular concentrations and resistance to vinorelbine223 and doxorubicin224–226, and its inhibition enhanced cisplatin-vinorelbine efficacy in lung cancer xenografts227. RLIP76 transport activity appeared to be regulated by protein-kinase-C-α (PKC-α)-mediated phosphorylation226, 228. The greater resistance to doxorubicin in NSCLC cells compared to SCLC cells may be mediated through differential phosphorylation of RLIP76 in NSCLC vs SCLC226. Lung cancer clinical data are unavailable.

6.0 Drug detoxification

Drugs may also be neutralized or detoxified by various cellular mechanisms (Fig. 3).

6.1 Glutathione (GSH)

GSH may bind cisplatin, thereby decreasing formation of platinum-DNA adducts. It may also play a role in increased repair of platinum-DNA adducts 229 and it plays a role in drug efflux via pumps that expel GSH-conjugates from cells (“GS-X pumps”). In lung cancer cell lines that had been rendered resistant to anthracyclines, vinca alkaloids and etoposide by transfection with the MRP gene, GSH depletion by DL-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine (BSO) reversed resistance, suggesting that MRP functions as a GS-X pump136. While efficacy of cisplatin against NSCLC cell lines90, NSCLC xenografts230, or SCLC cell lines231, 232 did not correlate with GSH content in some studies, in several other NSCLC cell lines92, 93, 233, 234 and SCLC cell lines 32, 93, 142, 233, 235–237, increase in GSH content was accompanied by increase in cisplatin resistance32, 92, 93, 142, 233–237, with decreased platinum-DNA binding93, 236, 237, and with decreased intracellular platinum accumulation32. Factors that reduced cellular GSH augmented sensitivity to cisplatin93, 141 or other agents238.

Etoposide-resistant and doxorubicin-resistant NSCLC cell lines also may have increased GSH content 238, and in some cases, cisplatin resistance and increased GSH content was accompanied by cross-resistance to vinca alkaloids236, anthracyclines32, etoposide32, camptothecins32, mitomycin-C32, alkylating agents32, methotrexate32, and radiation234, while in other instances, resistance to cisplatin with augmented GSH was accompanied by lack of cross-resistance to anthracyclines or epipodophyllotoxins236, or by collateral sensitivity to vinca alkaloids and 5-fluorouracil32.

Expression of genes involved in GSH synthesis (glutamate-cysteine ligase [GCL], also known as gammaglutamylcysteine synthetase [GGCS]) in NSCLC xenografts also enhanced resistance to cisplatin239, 240, and inhibition of GCL decreased cisplatin resistance241. The expression level of the GCL light chain subunit gene was significantly higher in NSCLC than in SCLC239. Survival of NSCLC patients treated with cisplatin-based regimens was significantly associated with host genotype for some GSH metabolic genes242.

In vitro sensitivity testing of lung cancers that had been resected demonstrated increased resistance to cisplatin for tumors that were IHC positive for GSH peroxidase and GSH reductase, and IHC expression also varied significantly with lung cancer histologic types243.

Overall, the preponderance of preclinical evidence supports a role for GSH in resistance to cisplatin and perhaps other agents in both NSCLC and SCLC, although the relationship is not consistent across all studies, and clinical data are limited.

6.2 Glutathione-S-transferase-pi (GST-pi)

GST catalyzes the binding of GSH to various compounds. There has been particular interest in the GST-pi variant in chemotherapy resistance, and SCLC cell lines had lower GST-pi expression than did NSCLC cell lines244, 245. Cisplatin resistance correlated with GST-pi expression244–246, GST activity 231, or absence of GST inhibitor232, 247 in cells harvested from resected NSCLC tumors246, in some NSCLC cell lines244, and in some SCLC cell lines231, 232, 244, 245, 247, but in other NSCLC cell lines90, 92, 93, 160, 248 and SCLC cell lines93, 95, 236, resistance to cisplatin90, 92, 93, 95, 236, 248, anthracyclines95, 160, vinca alkaloids95, 160, 236, etoposide160, 248, irinotecan248, taxanes248, 5-fluorouracil160 and radiation95 did not correlate with GST-pi expression.

Clinically, NSCLC tumors were positive for GST-pi or had high GST-pi IHC expression in 56–69% of patients246, 249–251. Some clinical studies showed a correlation between lack of response187, 249–251 or increased risk of relapse or shortened survival187 and high tumor187, 249–251 or serum252 GST-pi expression in NSCLC patients treated with platinum-vindesine249, platinum-etoposide250, cisplatin, ifosfamide, vinblastine and radiation187 or various platinum-based regimens251, 252 for advanced disease249–252, for locally advanced disease187, or with adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy for resected disease246. NSCLC patients treated with platinum-based regimens who had the GST-pi exon 6 wild type host genotype (Ala/Ala) had significantly worse survival than did patients with the variant genotype (Ala/Val or Val/Val), while GSTpi exon 5 genotype was not associated with survival253.

On the other hand, some other NSCLC studies showed no correlation between tumor GST-pi IHC expression and response194, 195 or survival195 in patients with locally advanced disease undergoing radiotherapy combined with vinorelbine +/− carboplatin195 or in patients with advanced disease receiving platinum-based chemotherapy194, 254. Furthermore, a second pharmacogenetic study failed to demonstrate an association between GST-pi exon 5 and exon 6 polymorphisms and response to chemotherapy or survival, although patients possessing the variant alleles GSTP1 105Val or GSTP1*B demonstrated trends toward inferior response and survival255.

Overall, as with GSH, the association of GST-pi with resistance of lung cancer to platinums and other agents is suggestive but is not consistent across studies, and there is little experience with attempts to clinically modulate GST-pi in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy.

6.3 Metallothioneins

Metallothioneins are a family of cysteine-rich low molecular weight proteins that are involved in zinc homeostasis and may also be involved in chemotherapy binding and detoxification. Increased metallothionein expression was noted in some cisplatin-resistant NSCLC92 and SCLC232 cell lines, and metallothionein expression also correlated with resistance to etoposide256. Exposure of lung cancer cell lines to cadmium or zinc increased metallothionein synthesis and increased resistance to etoposide256.

In patients with SCLC treated with alternating cisplatin-etoposide/CAV, IHC for metallothionein (45% positive) correlated significantly with short survival257. Overall, IHC expression of metallothionein in human tumors was less common in SCLC than in NSCLC, and it increased post exposure to chemotherapy258.

6.4 Dihydrodiol dehydrogenase (DDH)

NSCLC cells overexpressing or transfected with DDH (a cytoplasmic aldo-keto oxidoreductase enzyme that plays an important role in the detoxification process259 and in the metabolism of steroid hormones, prostaglandins and xenobiotics260) had increased resistance to cisplatin259–261, doxorubicin259, 261, vincristine261, melphalan261 and radiation259. While some assessments suggested an association between DDH expression and paclitaxel resistance261, a systematic review of cell lines with an inverse resistance relationship between cisplatin and paclitaxel (resistant to cisplatin but sensitive to paclitaxel) suggested that increased expression of DDH was a common characteristic of such cells167. Proinflammatory mediators such as interleukin-6 induced DDH expression in NSCLC cells, but this induction could be prevented by protein kinase C inhibitors260. DDH expression inversely correlated with the DNA repair factor Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 (NBS1) and with apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF)260. DDH is often overexpressed in NSCLC cells, and patients with DDH overexpression are at increased risk of recurrence259, and have a poor prognosis and chemoresistance260. Hence, preclinical data and limited clinical data suggest a role for DDH in lung cancer resistance.

6.5 Deoxycytidine deaminase

Gemcitabine is activated by conversion to the metabolite gemcitabine triphosphate (see below), and gemcitabine triphosphate may then be inactivated by the enzyme deoxycytidine deaminase. Deoxycytidine deaminase activity was lower in SCLC33, 139 and NSCLC139 variants that were sensitive to gemcitabine compared to resistant variants. In pharmacogenetic analyses in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with cisplatin-gemcitabine, a cytidine deaminase host polymorphism associated with significantly reduced enzymatic activity correlated with better clinical benefit, toxicity and longer time to progression and overall survival262.

6.6 Other potential detoxifying mechanisms

Down-regulation of expression of the redox factor peroxiredoxin V in lung cancer cell lines augmented efficacy of etoposide and doxorubicin, suggesting a role for redox reactions in resistance to these agents263. In NSCLC and other cell lines, thymidine administration inhibited cytotoxicity of pemetrexed, and dipyridamole prevented this rescue by blocking thymidine transport264. High extracellular folate pools also markedly decreased cell killing by pemetrexed265. The clinical importance of these observations is uncertain.

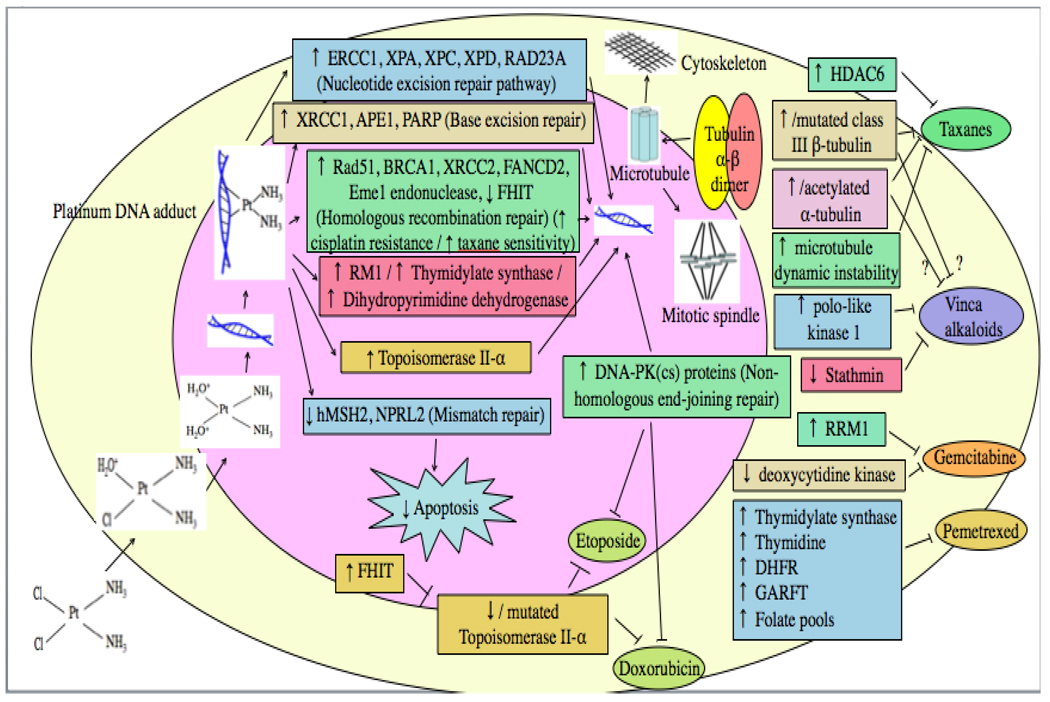

7.0 Drug activation and binding

Resistance may also occur if there is defective drug activation (Fig. 2 and 4).

Fig. 4.

Drug-induced DNA damage may be repaired by various DNA repair pathways, or apoptosis may be triggered as a result of attempted repair of platinum-induced damage by the Mismatch Repair pathway. Drug effect can also be reduced due to increased, decreased or mutated target.

7.1 Deoxycytidine kinase

Some NSCLC21, 120, 135, 139, 266, 267 and SCLC33, 139 cell lines resistant to gemcitabine had decreased activity of the enzyme deoxycytidine kinase which is responsible for conversion of gemcitabine to its active metabolite, gemcitabine triphosphate. Observations in some lines suggested that deoxycytidine kinase deficiency may play more of a role in acquired gemcitabine resistance than in intrinsic resistance120.

MRP1 expression was associated with increased deoxycytidine kinase expression and with augmented sensitivity to gemcitabine, and antagonism of MRP1 by verapamil reduced sensitivity to gemcitabine, possibly be decreasing expression of deoxycytidine kinase139, 268. Corticosteroids alone decreased deoxycytidine kinase activity and also decreased gemcitabine efficacy in NSCLC cell lines268. Synergism between gemcitabine and pemetrexed in NSCLC cell lines appears to be mediated in part through the up-regulation of expression of deoxycytidine kinase expression by pemetrexed135, 267, although upregulation of expression of the gemcitabine transporter (hENT1) and decreased phosphorylation of Akt may also play a role267. Clinical data on the importance of deoxycytidine kinase remain limited.

7.2 DNA binding of platinum agents and intracellular pH

DNA binding of cisplatin (ie, platinum-DNA adduct formation) was increased in some cisplatin sensitive NSCLC93, 94, 269 and SCLC93, 99, 232, 237, 270 cell lines compared to resistant variants, although this was not seen in all cases93, 233. Through mechanisms that are unclear, the antifungal agent amphotericin B increased sensitivity to cisplatin while increasing cisplatin uptake and DNA binding in both NSCLC and SCLC cell lines271. As outlined in an earlier review48, when cisplatin or carboplatin enter tumor cells, chloride adducts are lost in the low-chloride intracellular milieu and are replaced by water molecules to form highly reactive, positively charged aquated species or relatively non-reactive, neutral hydroxy moieties. A more acidic intracellular pH favors formation of the positively charged species, and it is the positively charged species that is the active form of cisplatin that binds to DNA. An acidic intracellular pH was also associated with a reduction in cisplatin efflux in NSCLC cell lines, possibly due to both more rapid intracellular binding as well as decreased ability to passively diffuse back out across cell membranes269. Resistant lung cancer variants with decreased DNA binding had a more alkaline intracellular pH compared to sensitive variants269, 272. However, the proton pump inhibitor AG-2000 did not alter sensitivity of a cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cell line273. In more resistant lines with higher intracellular pH, platinums tended to concentrate more in acidic organelles due to their tropism for an acidic environment272.

In NSCLC patients treated with daily low dose cisplatin and XRT, cisplatin-DNA-adduct staining in buccal cells was an independent prognostic factor, with shorter survival times for patients with low adduct staining274. Overall, preclinical data support a role for reduced DNA-adduct formation and for increased intracellular pH in lung cancer resistance to platinums, but clinical data remain limited.

8.0 Increased, decreased or altered target

Depending on the drug and its target, resistance may also occur if drug target is increased, decreased or mutated (Fig. 4).

8.1 Tubulin

NSCLC cell lines rendered resistant to taxanes had significantly increased expression of class III β-tubulin275–279 encoded by the Hβ4 gene279, and may also have had increased α-tubulin278. Findings were less consistent in NSCLC lines rendered resistant to vinca alkaloids, in that some had significantly increased β-tubulin280 while others instead had significantly decreased expression of class III β-tubulin275. Increased expression of β-tubulin after taxane exposure was inhibited in the presence of wild type p53276.

In two NSCLC cell lines, siRNA vs βIII-tubulin inhibited its expression, and increased sensitivity not only to the tubulin binding agents paclitaxel, vincristine, and vinorelbine, but also to cisplatin, doxorubicin, and etoposide281. In some NSCLC cell lines that were more resistant to paclitaxel under hypoxic conditions than under normoxic conditions, the expression level of β-tubulin was comparable under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, but the distribution of β-tubulin and cell morphology were changed according to HIF-1α expression levels, suggesting that HIF-1 influences the conformation and dynamics of microtubules52.

Polo-like kinases (PLKs) play a role in mitotic entry, spindle pole function and cytokinesis282. Expression of PLK 1 was elevated in NSCLC, and inhibiting it abolished microtubule polymerization, led to abnormalities in spindle formation and to abnormalities in staining for α-tubulin, arrested cells in G2/M, induced apoptosis, and substantially potentiated the efficacy of vinorelbine283.

In NSCLC284 and SCLC285 cell lines resistant to taxanes, there was increased microtubule dynamic instability284 or increased acetylation of α-tubulin285 and partial dependence on taxane for growth284, 285. In addition, histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) decreased microtubule stability and antagonized the effect of paclitaxel on NSCLC cells, while the farnesyl transferase inhibitor lonafarnib blocked the effect of HDAC6 on tubulin and was synergistic with paclitaxel286.

In IHC assessments of advanced NSCLC, all tumors stained with pan-β tubulin antibody and class I tubulin isotype287. A majority of the tumor samples expressed class II and class III tubulins, although the percentage of positive cells varied significantly between tumors287. Expression of delta2 α tubulin was uncommon287. In another study involving European patients, β-tubulin mutations in exons 1 or 4 were noted in 33% of NSCLC patients, and β-tubulin mutations were also detected in serum DNA of 42% of 131 NSCLC patients (vs none of a control group)288, although they were uncommon in tumors of Japanese patients with NSCLC or SCLC289. In NSCLC patients treated with surgery alone, high class III β-tubulin expression was associated with poorer relapse-free and overall survival290.

In locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC treated with taxane-containing regimens, patients with tumor β- tubulin mutations had substantially lower response rates288 or a trend towards lower response rates287 than did patients with wild type β-tubulin. Response rates were also lower in patients with high tumor expression of β-tubulin III compared to those with low expression291, 292. There was also a longer time to progression287, 291, 292 and longer survival292 with low β-tubulin III mRNA expression in patients treated with taxane-containing regimens, but not in patients receiving non-tubulin-binding regimens292.

Advanced NSCLC patients treated with vinorelbine/cisplatin who had low β-tubulin III mRNA expression also had a significantly longer time to progression291, 293, lower likelihood of tumor progression while on therapy293 and longer overall survival293 than patients with high expression. Low Delta2 α-tubulin expression was also associated with a significantly longer overall survival in patients treated with cisplatin/vinorelbine293, while tubulin II levels did not correlate with patient outcome293. Conversely, when cisplatin/vinorelbine was administered as adjuvant therapy to patients who had undergone surgical resection of their NSCLC tumors, greater benefit of the therapy was seen in patients with high vs low class III β-tubulin, and the adjuvant therapy appeared to overcome the negative prognostic effect of high β-tubulin290. It is unclear why the effects of tubulin on vinorelbine efficacy appear to be different in the adjuvant setting than in advanced disease.

Overall, the available data suggest that elevated expression or mutation of class III β-tubulin (and possibly α-tubulin) increases resistance to taxanes, with somewhat more equivocal data for its effect on resistance to vinca alkaloids.

8.2 Topoisomerase II-α (topo II-α)

Ordinarily, topo II temporarily breaks DNA, permitting it to unwind, then puts it back together again. Epipodophyllotoxins such as etoposide and teniposide, and anthracyclines such as doxorubicin and epirubicin bind to topo II and permit it to break DNA, but block its ability to rejoin the cleaved strands, leading to potentially lethal DNA breaks. A variety of topo II-α abnormalities have been found in resistant lines.

On average, SCLC cell lines are more sensitive to topo II inhibitors than are NSCLC cell lines115, 294. SCLC cell lines had only a modest increase in topo II-α levels and topo II catalytic activity compared to NSCLC cell lines in one study, and no clear association across all unrelated cell lines between sensitivity and topo II-α levels or topo II activity294. However, in another cell line comparison, nuclear topo II activity was twofold higher in SCLC cell lines than in NSCLC cell lines115, and when resistant variants were compared to their sensitive parent line in matched comparisons, expression of topo II-α mRNA and protein levels were lower in the resistant variants295.