Abstract

Objective

To describe the perspectives and experiences of chronic hemodialysis (CHD) patients regarding self-care and adherence to fluid restrictions.

Design

Semi-structured focus groups.

Setting

Two outpatient hemodialysis centers.

Participants

19 patients on chronic hemodialysis.

Intervention

Patients were asked a series of open-ended questions to encourage discussion about the management of fluid restriction within the broad categories of general knowledge, knowledge sources or barriers, beliefs and attitudes, self-efficacy, emotion, and self-care skills.

Main outcome measure

We analyzed session transcripts using the theoretical framework of content analysis to identify themes generated by the patients.

Results

Patients discussed both facilitators and barriers to fluid restriction which we categorized into 6 themes: knowledge, self-assessment, psychological factors, social, physical, and environmental. Psychological factors were the most common barriers to fluid restriction adherence, predominantly involving lack of motivation. Knowledge was the most discussed facilitator with accurate self-assessment, positive psychological factors, and supportive social contacts also playing a role. Dialysis providers were most commonly described as the source of dialysis information (54%), but learning through personal experience was also frequently noted (28%).

Conclusion

Interventions to improve fluid restriction adherence of chronic hemodialysis patients should target motivational issues, assess and improve patient knowledge, augment social support, and facilitate accurate self-assessment of fluid status.

Keywords: hemodialysis, interdialytic weight gain, focus group, quality of life, qualitative research

Introduction

Chronic hemodialysis (CHD) requires significant patient involvement in a complex and demanding medical regimen. Self-care behavior includes adherence to prescribed medications, caring for vascular access, and importantly, the daily management of dietary and fluid intake. Recommendations include selecting food items low in sodium, potassium and phosphorus, maintaining adequate protein intake, and limiting net daily fluid gain to no more than 1 to 2 liters. Studies suggest that many CHD patients do not successfully execute these self-care behaviors.1, 2 Of these factors, nonadherence to fluid intake is among the most common.3

In chronic hemodialysis, a patient’s fluid status is reflected by their interdialytic weight gain (IDWG). In the United States, 10–20% of CHD patients routinely experience high IDWG, often defined as ≥ 5.7% of a patient’s estimated dry weight.2, 4 High IDWG has been associated with complications such as hypertension, congestive heart failure, and even death.1, 2, 5, 6 Additionally, removal of this excess fluid during traditional hemodialysis is difficult and may result in hypotensive episodes and patient symptoms such as muscle cramps, nausea, and headache.

Programs to improve adherence with fluid restriction in CHD patients, incorporating a variety of psychological methods to change behavior as well as educational components to improve knowledge, have demonstrated mixed results.7 These programs were developed using the principles of health behavior theories, published literature, expert opinion, and occasionally surveys of dialysis patients. Few describe a priori attainment and use of patient perspectives to guide interventions, a method widely used in other chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.8–10 By soliciting patient perspectives on self-management of fluid restriction, we hope future interventions can be tailored and sensitive to the needs and culture of the chronic hemodialysis population.

Although individual patient-provider encounters are fundamental to dialysis care, engaging groups of patients in a discussion can yield important insights that may not be accessible without this peer interaction. Focus groups are widely used and well suited to explore patients’ experiences with disease and therapies.11 The objective of this study was to use focus group methods to describe chronic hemodialysis patients’ experiences with fluid management in order to identify specific content areas or strategies to guide the development of patient-centered, effective, and adaptable fluid adherence interventions.

Methods

Data Collection

We conducted a total of five focus groups with chronic hemodialysis patients from February through April 2008. Each focus group involved 3 to 5 participants who were recruited by convenience sampling from two hemodialysis facilities. These facilities care for a population that is 51% female, 69% African American, and a mean (standard deviation) age of 54 (16) years. Patients were eligible to participate if they spoke English, were at least 18 years-old, and were able to give informed consent. Focus groups met in a conference room adjacent to the hemodialysis unit for patient convenience and, to encourage openness, no nonparticipants or members of the healthcare team were present. Patients were given a demographic survey to complete prior to the start of the session. This included a single-item assessment of self-rated health as poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent. One of the authors (K.G.) facilitated the discussion using a list of questions relating to the following fluid management content areas: general knowledge, knowledge sources and barriers, beliefs and attitudes, self-efficacy, emotion, and self-care skills (See Appendix for Focus Group Guide Questions). Each session lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. All sessions were digitally audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. We continued to conduct focus groups until no new themes developed which occurred after five groups.

Analysis

Transcripts were entered into QSR NVivo 2.0 (QSR International Pty. Ltd.), a software program used to store, code, and search data. Using the theoretical framework of content analysis, transcripts were reviewed line by line by the first author, who searched for themes and developed a preliminary coding scheme. Transcripts were then read and coded by two authors independently (K.S., M.C.), who compared and discussed their individual coding choices with a 3rd author (K.C.) and any disagreements were resolved by group discussion and consensus. The coding scheme was revised to develop a final coding structure that captured all data. This qualitative assessment was complemented by an assessment of the numbers of comments in individual content areas. Previous studies have demonstrated that the frequency with which an item is mentioned correlates with direct measures of its importance to participants.12, 13

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Vanderbilt University Medical Center and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

The five focus groups involved 19 participants with a mean age of 54 years (range 28 to 82). Most participants were women, African American and with low socioeconomic status (Table 1). Participants had been on dialysis a mean of 5 years (range 1 to 14).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Characteristic (n=19) | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54 (15) |

| Female | 63% |

| African American | 78% |

| Income <$20,000 per year | 68% |

| Education (years) | 12 (3) |

| Married | 26% |

| Employed | 15% |

| Years on Dialysis | 5 (4) |

| Self-rated Health Good or Very Good | 54% |

We divided participant statements into two mutually exclusive themes: barriers--factors which made adherence to fluid restrictions more difficult; and facilitators--factors that helped patients adhere. Almost twice as many more patient statements described facilitators (881 statements (66%)) than barriers (443 statements (34%)).

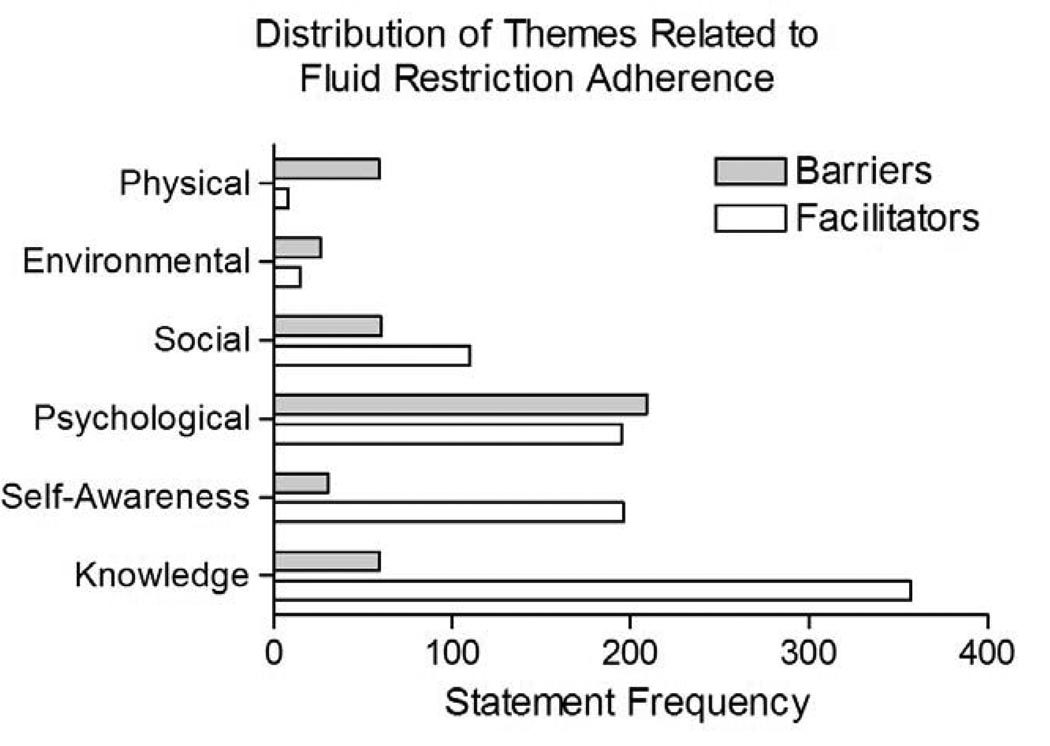

We identified six subthemes: knowledge, self-assessment, psychological, social, environmental, and physical. Barriers were most often related to psychological factors (47%), followed by social (14%), knowledge (13%), and physical (13%). Facilitators most described were knowledge (41%), self-assessment (22%) and psychological factors (22%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of themes related to facilitators and barriers to fluid restriction adherence.

Barriers - Psychological Factors

Psychological factors were the most commonly discussed barriers to fluid adherence. The majority of these statements described an overall lack of motivation to restrict fluid. Reasons included a sense that restriction techniques were ineffective, dialysis would compensate for any excess fluid intake, fluid goals were inappropriately low, and that previous excess fluid or sodium intake did not have immediate repercussions. Many patients described a general disinterest in restricting fluid or just described it as being “too hard” (Table 2).

“I’ll eat too many grapes. I am not supposed to have that many grapes. As soon as I get through eating them, I want some water.” (Female, 70s, 4 months CHD)

“The machine and that tech in there are my crutch. I know I can come in and they are going to take care of it [excess fluid].” (Male, 40s, 3 years CHD)

“You don’t always feel the consequences of eating that piece of pizza…it doesn’t resonate in your mind that what you are doing at that time is not good for you. Most of us don’t feel good anyway so we are not going to feel the consequences of it right away.” (Male, 20s, 2 years CHD)

Other psychological factors included dietary preferences and habits that made restricting fluid more difficult, cravings for fluid or sodium, difficulties balancing competing medical or social demands, and an overall negative outlook or comorbid depression.

“It’s like when you’re on a diet and you are not supposed to eat. When you are not supposed to drink, that’s all you think about.” (Female, 40s, 14 years CHD)

“I get stuck on one thing like trying to watch my protein or my phosphorous and I’ll forget about the other stuff.” (Female, 40s, 14 years CHD)

Table 2.

Patient identified reasons for lack of motivation to adhere to fluid restriction.

| Reason for Lack of Motivation | Statement Frequency n (%) |

|---|---|

| Nonspecific | 45 (41%) |

| Ineffective Techniques | 31 (28 %) |

| Dialysis will Compensate | 14 (13%) |

| Feels Fine Regardless | 8 (7%) |

| Disagree with Goals | 3 (3%) |

| Other | 8 (7%) |

| All Reasons | 109 (100%) |

Barriers - Social

Social barriers to fluid adherence included lack of support from family, friends, providers and peers, special occasions such as eating at restaurants and holiday gatherings, and continuing employment.

“I still work as much as I can, so I wouldn’t want to carry around something to try and keep up with it [fluid measurement].” (Female, 40s, 14 years CHD)

“It’s my social bridge that I have with another person. Cut out all my other bad habits, so now I have a drink and talk.” (Male, 40s, 3 years CHD)

Barriers - Knowledge

Lack of knowledge was seen as a barrier to fluid restriction adherence. Patients most commonly described limitations to education such as a lack of understanding of what they were taught until they personally experienced the consequences, an inability to self-educate, and providers’ use of technical terminology. Patients specifically discussed poor knowledge of renal physiology, dialysis practices, nutrition, and fluid goals.

“I would have been dead a long time ago if it [education] was left up to me, I really would hate to think about that.” (Male, 50s, 2 years CHD)

“They speak in a Latin tongue and I don’t understand. I have to say, ‘Wait a minute. What do you mean by that?’ And they just jibber, jibber, jibber.” (Female, 50s, 3 years CHD)

“[My physician asked,] ‘What have you been eating?’ I told him we just went out and had burgers and he said, ‘What?…. It’s all full of sodium’ and I didn’t realize that that stuff was full of sodium. I didn’t realize it.” (Female, 70s, 4 months CHD)

Barriers - Self-assessment

Lack of accurate self-assessment such as being unable to judge overall fluid status, fluid intake, or sodium intake was a less commonly discussed as a barrier. Often, patients reported not using objective measurements such as fluid volume measurement or body weights.

“To me I am not drinking that much. But you know, when I get to dialysis I overdid it.” (Female, 60s, 2 years CHD)

“I never tried to measure. I can try to remember what I drink. I’ll look back and say ‘Well maybe I did go over a little bit.’” (Male, 50s, 2 years CHD)

Barriers - Physical & Environmental

Thirst was the most common physical barrier, but patients also reported comorbid conditions which impacted their fluid intake.

“By the time I take medicine three times a day, that quart of water is gone.” (Female, 70s, 4 months CHD)

Dialysis-related physical barriers included thirst immediately following dialysis or the need for intradialytic fluid and saline boluses for hypotension.

Environmental factors were rarely discussed as barriers to fluid intake. When discussed these included the need for weekly two-day interdialytic periods, dialysis unit policies that were permissive of fluid intake while on dialysis, weather, poor access to appropriate foods, and being at or away from home.

Facilitators - Knowledge

Knowledge was the most commonly discussed facilitator of fluid adherence. Patients felt it was important to know basic physiology, dialysis practices, nutrition, techniques to aid in fluid restriction, volume measurement, how to read food labels, and overall fluid intake goals.

“If that fluid builds up and you can’t get rid of it, that poison goes around your heart and through your whole body.” (Male, 40s, 3 years CHD)

“They have to have a lot of sodium in there, so they can store them on the shelf as long as they do in the store. Mostly everything that you get prepared is full of sodium.” (Female, 70s, 4 months CHD)

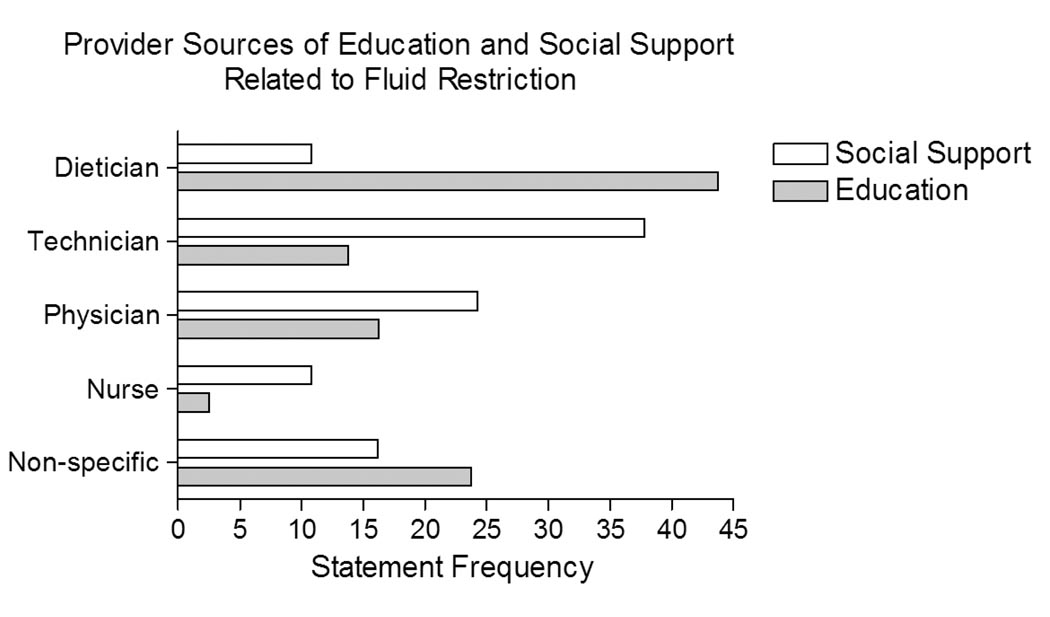

The knowledge theme also included statements describing sources of new knowledge. Most patients discussed learning primarily from dialysis providers and through personal experiences while very few discussed self-education (Table 3). Dieticians were most often credited with education while physicians and dialysis technicians were less often mentioned but discussed about equally (Figure 2).

“Once they [dieticians] say that [you need to restrict fluid more], if you have to come back to the hospital you will understand what she meant. And sometimes you don’t catch on right away, but soon, soon enough, what she is saying to you is starting to make sense. At that point, you just take the advice.” (Male, 50s, 2 years CHD)

“What really helps me [adhere to a fluid restriction] is remembering what it’s like to not breathe.” (Male, 40s, 3 years CHD)

Table 3.

Patient identified sources of information about fluid restriction.

| Source of Information | Statement Frequency n (%) |

|---|---|

| Dialysis Providers | 88 (54%) |

| Personal Experience | 45 (28%) |

| Pre-ESRD | 12 (7%) |

| Peer Experience | 8 (5%) |

| Self-Education | 6 (4%) |

| Other | 3 (2%) |

| Total | 162 (100%) |

Figure 2.

Patient identified dialysis provider sources of education and social support.

Facilitators - Self-assessment

Patients often discussed the importance of continuous and accurate self-assessment of their overall fluid status, their fluid and sodium intake, and which restriction techniques work best for them. They also discussed the importance of being aware of their urine output and adjusting their fluid intake accordingly.

“I try to drink water rather than something that tastes good, because if it tastes good, I want to drink more of it.” (Female, 40s, 14 years CHD)

“I weigh myself at night and when I get up in the morning. Last night I was like 5 pounds heavier, so I knew I had put that much fluid on just during the day. That was just one day. So I have got to tighten up even better.” (Female, 70s, 4 months CHD)

Facilitators - Psychological Factors

Patients also described psychological factors that facilitated adherence. These factors included beliefs that patients are personally responsible for their own fluid intake and are capable of self-restriction, and that it is important to restrict fluid.

“Let them [new dialysis patients] know how important it is to monitor your fluid because every day that you come in here overloaded, you are shortening your life span. It’s that critical. You have to let them know that.” (Male, 40s, 3 years CHD)

“I oftentimes just think about me and what I need to do for me. Who is going to stop you from doing for you? Nobody. Help yourself.” (Male, 20s, 4 years CHD)

Patients also discussed having an overall positive outlook, having personal dietary and lifestyle preferences and habits that made it easier to restrict fluid, being comfortable asking questions of their providers, and a enjoying a sense of accomplishment when they meet their fluid goals.

“I just decided the quality of our life is what we make of it. So it’s a frame of mind.” (Male, 40s, 3 years CHD)

Facilitators - Social

Patients discussed the importance of supportive social networks in helping them adhere to fluid restrictions, most often family and friends. They also acknowledged social support from dialysis providers, most commonly their dialysis technicians (Figure 2). Although less common, patients discussed support from religion and their dialysis peers.

“When I come in to treatment I will be looking at my tech like, ‘What is she going to say about me having all this fluid on?’ …I kind of look at her and see the look that she gives me like, ‘Boy, you better stop that.’“ (Male, 20s, 4 years CHD)

“I was just sitting there in the waiting room. There was a group of people waiting to go on the machine. People were talking fluid.” (Male, 40s, 3 years CHD)

Facilitators - Environmental & Physical

Environmental factors were rarely facilitators of fluid adherence. Few statements discussed physical facilitators of fluid adherence. These included early satiety, food intolerances, and symptoms following hemodialysis.

Discussion

Patient perspectives regarding the management of fluid restriction in chronic hemodialysis were diverse and were likely influenced by many patient characteristics, including their experience with hemodialysis. The most frequently discussed facilitator of adhering to fluid recommendations was knowledge, with accurate self-assessment and positive psychological factors also described as having a beneficial role. The majority of knowledge was gained through interactions with dialysis providers and personal experiences with few reports of self-education. The most often discussed barriers were psychological primarily relating to an overall lack of motivation to restrict fluid. Social networks such as family and friends, dialysis providers, and peers sometimes facilitated and sometimes were barriers to attaining fluid restriction goals. By considering these patient perspectives on the importance of issues in the management of fluid restriction, we hope to guide future interventions to be patient-centered and culturally sensitive.

Patients repeatedly discussed psychological factors that negatively impacted their ability to restrict fluid. Most commonly this involved lack of motivation to change their fluid intake behavior. Previous studies have identified 25–40% of dialysis patients in a precontemplative stage and have suggested the need to identify these patients and tailor interventions to strongly emphasize the benefits of fluid restriction adherence.14 Psychosocial interventions to improve motivation have shown promise in other chronic diseases such as diabetes15 and need to be further studied in the chronic kidney disease (CKD) population. A randomized controlled multicenter trial to assess improvement in CKD Stage 3 and 4 patients’ self-management using a nurse-driven intervention incorporating motivational interviewing is in progress.16 If successful, these techniques to improve patient motivation may also be useful in for dialysis patients.

Knowledge was the most commonly discussed facilitator of fluid restriction adherence. Specifically, patients discussed the importance of understanding basic physiology including the normal function of the kidneys and the role of dialysis, general nutrition, techniques to aid in fluid restriction, volume measurement, food label interpretation, and overall fluid intake goals. In dialysis patients, knowledge has been associated with improved adherence to dietary recommendations and permanent arteriovenous access use.17, 18 Despite this, few studies examine educational interventions to improve fluid restriction adherence.7, 19 Even fewer studies assess patient fluid management knowledge, and often do not employ a validated instrument to measure this important factor.7, 20 Development of a validated assessment tool of patient knowledge of fluid management in dialysis is needed to identify gaps in patient knowledge, tailor individual educational interventions, and to evaluate the impact of these interventions.

Identifying a trusted source of health information is fundamental to patient education and self-management. Dietitians were most often cited as providing information on fluid management, consistent with previous research identifying the renal dietitian as the most trusted provider to deliver dietary advice.21 It was notable, however, that hemodialysis technicians were also frequently mentioned as a source of information about fluid management, discussed nearly as often in our focus groups as nephrologists. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has required that every technician be certified as a Certified Clinical Hemodialysis Technician (CCHT) by April 201022, formalizing the technician’s role within the multidisciplinary hemodialysis care team. Because technicians often have the most contact time with patients, future interventions may benefit from increased use of CCHTs in educational initiatives.

The second most common facilitator of fluid restriction adherence was the ability to form an accurate self-assessment of overall fluid status as well as fluid and sodium intake. Patients based this assessment on physical symptoms such as edema, abdominal distension, and dyspnea on exertion but also described measurement of fluid volumes and body weights, and reading food labels. Patients less commonly discussed lack of accurate self-assessment as a barrier to fluid restriction adherence. While patients may simply be uncomfortable discussing shortcomings in a group setting, it is also possible that they are unaware of an inability to accurately assess volume status or fluid and sodium intake. For example, studies have shown that a surprising number of patients are unable to accurately interpret the information contained in a food label.23 This has obvious implications for their ability to accurately tabulate their sodium intake. In heart failure, interventions to improve food label interpretation and disease management programs that incorporate patient education on self-assessment of volume status such as daily weighing and early attention to signs and symptoms have had promising results.24

Social contacts were described sometimes as facilitators and sometimes as barriers to adherence to fluid restriction. Family and friends were most often cited with their effect dependent on their willingness to learn about the patient’s dietary needs and support them in making the necessary lifestyle changes. Few studies have examined the impact of social support interventions in dialysis patients and those that have are limited by small sample size, retrospective analyses, and lack of control groups.25 However, in patients with and without renal disease, increased social support positively affects outcomes and has been linked to survival through several mechanisms including improved adherence to treatment recommendations.26

The generalizability of our study is limited since our patients were most African American with low socioeconomic status. However, previous studies suggest that this population is at higher risk for nonadherence to the dialysis regimen and fluid restriction.1, 3, 27 We do not have an objective measure of the residual renal function of our participants or factors specific to their dialysis prescription such as sodium modeling, both of which may impact their ability to manage their fluid restriction. The small number of patients involved is another limitation; however, we continued to hold focus groups until no new themes developed. Despite these limitations, we believe our participants raised issues experienced by a larger subset of the hemodialysis population. Our results may not be generalizable to some specific patient end-stage renal disease groups, for example, peritoneal dialysis patients or incident hemodialysis patients who may have different perspectives and challenges regarding fluid management.

Through our focused discussions, we have obtained a view of what chronic hemodialysis patients perceive are the major facilitators and barriers to fluid restriction adherence. In the development of multi-faceted interventions, consideration should be given to assessment of baseline knowledge, targeting identified deficiencies for further education, identifying acceptable methods for accurate self-assessment, augmenting social support networks, identifying patients lacking motivation and working to enhance this motivation. With this information, we hope that future interventions better target issues patients feel are most important to their success or failure in restricting their fluid.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Kimberly Smith is supported by NIH NIDDK T32DK007569. Dr. Cavanaugh is supported by a National Kidney Foundation Young Investigator Grant and also by NIH NIDDK K23 DK080951-02; Dr. Elasy by NIH NIDDK K24DK077875 and P60DK020593; and Dr. Ikizler by NIH NIDDK K24DK062849. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Leggat JE, Jr, Orzol SM, Hulbert-Shearon TE, et al. Noncompliance in hemodialysis: predictors and survival analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998 Jul;32(1):139–145. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Rayner HC, et al. Nonadherence in hemodialysis: associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2003 Jul;64(1):254–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bame SI, Petersen N, Wray NP. Variation in hemodialysis patient compliance according to demographic characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 1993 Oct;37(8):1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90438-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ifudu O, Uribarri J, Rajwani I, et al. Relation between interdialytic weight gain, body weight and nutrition in hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2002 Jul–Aug;22(4):363–368. doi: 10.1159/000065228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Regidor DL, Kovesdy CP, et al. Fluid retention is associated with cardiovascular mortality in patients undergoing long-term hemodialysis. Circulation. 2009 Feb 10;119(5):671–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.807362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Movilli E, Gaggia P, Zubani R, et al. Association between high ultrafiltration rates and mortality in uraemic patients on regular haemodialysis. A 5-year prospective observational multicentre study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007 Dec;22(12):3547–3552. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp J, Wild MR, Gumley AI. A systematic review of psychological interventions for the treatment of nonadherence to fluid-intake restrictions in people receiving hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005 Jan;45(1):15–27. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peel E, Douglas M, Lawton J. Self monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: longitudinal qualitative study of patients' perspectives. BMJ. 2007 Sep 8;335(7618):493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39302.444572.DE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehane E, McCarthy G, Collender V, Deasy A. Medication-taking for coronary artery disease - patients' perspectives. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008 Jun;7(2):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Condon C, McCarthy G. Lifestyle changes following acute myocardial infarction: patients perspectives. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006 Mar;5(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995 Jul 29;311(7000):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groome PA, Hutchinson TA, Tousignant P. Content of a decision analysis for treatment choice in end-stage renal disease: who should be consulted? Med Decis Making. 1994 Jan–Mar;14(1):91–97. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9401400111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart DSP, Rook D. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. 2nd ed. Vol 20. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welch JL, Perkins SM, Evans JD, Bajpai S. Differences in perceptions by stage of fluid adherence. J Ren Nutr. 2003 Oct;13(4):275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1051-2276(03)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greaves CJ, Middlebrooke A, O'Loughlin L, et al. Motivational interviewing for modifying diabetes risk: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2008 Aug;58(553):535–540. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X319648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Zuilen AD, Wetzels JF, Bots ML, Van Blankestijn PJ. MASTERPLAN: study of the role of nurse practitioners in a multifactorial intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease patients. J Nephrol. 2008 May–Jun;21(3):261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas LK, Sargent RG, Michels PC, Richter DL, Valois RF, Moore CG. Identification of the factors associated with compliance to therapeutic diets in older adults with end stage renal disease. J Ren Nutr. 2001 Apr;11(2):80–89. doi: 10.1016/s1051-2276(01)98615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavanaugh KL, Wingard RL, Hakim RM, Elasy TA, Ikizler TA. Patient Dialysis Knowledge Is Associated with Permanent Arteriovenous Access Use in Chronic Hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Apr 23; doi: 10.2215/CJN.04580908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason J, Khunti K, Stone M, Farooqi A, Carr S. Educational interventions in kidney disease care: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008 Jun;51(6):933–951. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch JL, Thomas-Hawkins C. Psycho-educational strategies to promote fluid adherence in adult hemodialysis patients: a review of intervention studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005 Jul;42(5):597–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollingdale R, Sutton D, Hart K. Facilitating dietary change in renal disease: investigating patients' perspectives. J Ren Care. 2008 Sep;34(3):136–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2008.00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Services DoHaH. Medicare and Medicaid Programs: Conditions for Coverage for End-Stage Renal Disease Facilities; Final Rule. 2008. Apr 15, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Nov;31(5):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Sindaco D, Pulignano G, Minardi G, et al. Two-year outcome of a prospective, controlled study of a disease management programme for elderly patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2007 May;8(5):324–329. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32801164cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen SD, Sharma T, Acquaviva K, Peterson RA, Patel SS, Kimmel PL. Social support and chronic kidney disease: an update. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007 Oct;14(4):335–344. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel SS, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. The impact of social support on end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2005 Mar–Apr;18(2):98–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unruh ML, Evans IV, Fink NE, Powe NR, Meyer KB. Skipped treatments, markers of nutritional nonadherence, and survival among incident hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005 Dec;46(6):1107–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]