Abstract

Objective

Couples coping with head and neck and lung cancers are at increased risk for psychological and relationship distress given patients’ poor prognosis and aggressive and sometimes disfiguring treatments. The relationship intimacy model of couples’ psychosocial adaptation proposes that relationship intimacy mediates associations between couples’ cancer-related support communication and psychological distress. Because the components of this model have not yet been evaluated in the same study, we examined associations between three types of cancer-related support communication (self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and protective buffering), intimacy (global and cancer-specific), and global distress among patients coping with either head and neck or lung cancer and their partners.

Method

One hundred and nine patients undergoing active treatment and their partners whose average time since diagnosis was 15 months completed cross-sectional surveys.

Results

For both patients and their partners, multilevel analyses using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model showed that global and cancer-specific intimacy fully mediated associations between self- and perceived partner disclosure and distress; global intimacy partially mediated the association between protective buffering and distress. Evidence for moderated mediation was found; specifically, lower levels of distress were reported as a function of global and cancer-specific intimacy, but these associations were stronger for partners than for patients.

Conclusions

Enhancing relationship intimacy by disclosing cancer-related concerns may facilitate both partners’ adjustment to these illnesses.

Keywords: Relationship intimacy, self-disclosure, relationship processes, cancer, psychological distress

Patients diagnosed with lung and head and neck cancers may be at high risk for psychological distress. Indeed, suicide rates in these two patient groups are higher than the general population and higher than individuals diagnosed with other cancers. Rates of distress among lung cancer patients are between 15% and 35% for clinical depression [1, 2], 33% for anxiety disorders [3], and 34.6% for overall emotional distress [4]. Similar rates of depression, anxiety, and low quality of life have been reported for head and neck cancer patients [5–8]. Contributing factors to the higher rates of distress in these two patient populations are symptom burden (including difficulties with breathing, swallowing, speaking, and eating) [9, 10], body image concerns and the reduced social contact associated with disfiguring facial surgeries among oral cancer patients [11–14], higher rates of stigma and self-blame associated with behaviors such as smoking and alcohol use [8, 15], an increased risk for recurrence, and a relatively poor long-term prognosis [4, 16].

These cancers can also have a detrimental effect on significant others. Approximately 38.8% of male partners and 33% of female partners of lung cancer patients exhibit significant psychological distress [4, 17, 18]. Similarly high rates of psychiatric disorders [19–21] and psychological distress [22] have been reported among partners of head and neck cancer patients. These rates of distress are higher than those reported among patients diagnosed with many other types of cancer including breast cancer, melanoma, colorectal, prostate, and gynecological cancers [23].

Patients and partners coping with cancer often manage their stress by sharing their worries and concerns with one another with the goal of obtaining emotional, informational, and practical support [24, 25]. The exchange of support between partners is important during the cancer experience. Indeed, both cancer patients and spouses choose each other as the most important source of support [26–28]. Given the importance of the marital relationship in adaptation, a greater understanding of the process by which couples’ support-related communication affects psychological adjustment may aid in the development of interventions for couples coping with lung or head and neck cancers who may be at risk for greater psychological distress.

Relationship Intimacy Model of Couples’ Psychosocial Adaptation to Cancer

According to the relationship intimacy model of couple’s psychosocial adaptation to cancer [29], cancer-specific support-related behaviors such as self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness to disclosure can improve couples’ adjustment to cancer by enhancing perceived relationship intimacy and engaging in cancer-specific unsupportive behaviors such as protective buffering can compromise couples’ adjustment to cancer by reducing perceived relationship intimacy. Intimacy is defined as a process in which one person expresses important self-relevant feelings and information to another and, as a result of the other’s response, comes to feel understood, validated, and cared for [30, 31]. Although the relationship intimacy model is specific to cancer, it is based partially on the interpersonal process model of intimacy [30, 31] which proposes that intimacy develops from the ongoing disclosures and responses to disclosures between partners. The relationship intimacy model of couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer suggests that patients and partners evaluate their relationship experiences regarding cancer and the feelings of closeness (or reduced closeness) which may arise from these experiences separately from relationship experiences that are not related to cancer. For example, sharing cancer-related concerns with a responsive partner should bolster the person’s evaluation of how close they feel to the partner. However, the experience of closeness that patients and partners are formed separately from global perceptions of intimacy. Therefore, this model proposes that the predictors and effects of cancer-specific and global evaluations of relationship intimacy should be studied separately.

There is support for the relationship intimacy model of couple’s psychosocial adaptation to cancer. With regard to support-related communication, Manne and colleagues[32] evaluated the associations between general and cancer-specific self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and cancer-specific relationship intimacy among couples dealing with early stage breast cancer. They found that perceived partner disclosure was associated with patient and partner perceptions of relationship intimacy and that self-disclosure about breast cancer concerns was associated with greater cancer-specific relationship intimacy. Similar findings were reported in a cross-sectional study of men diagnosed with early stage prostate cancer and their partners. In a sample of gastrointestinal cancer patients and their spouses, Porter and colleagues [33] found that individuals who disclosed more of their cancer-related concerns to their partners experienced more global relationship intimacy. Finally, Kayser and colleagues [34] reported that empathic expression of feelings, thoughts, and activity between partners was associated with lower depressive symptoms among women diagnosed with various types of cancer. There is no literature linking protective buffering to relationship intimacy. However, studies in cancer patients have shown that it is associated with decreases in marital quality [35, 36] as well as increases in psychological distress [37]. Together, these studies support the components of the relationship intimacy model among cancer patients by demonstrating that support-related communication is linked to both intimacy and adjustment. However, no studies have directly tested whether intimacy is a key mediator or whether cancer-related intimacy and global relationship intimacy should be considered separately.

Study Aims

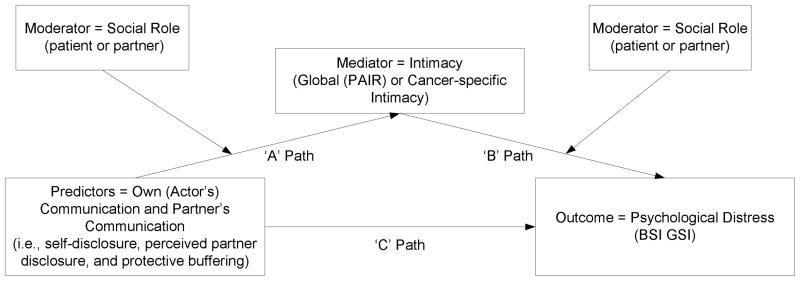

We evaluated the relationship intimacy model of couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer (see Figure 1) in a sample of patients with head and neck or lung cancers and their partners. We selected these two cancers because, as noted above, levels of distress are typically elevated in these couples and because communication and intimacy in the couple may be affected by the fact that the cancer may have been prevented with behavioral change (e.g., smoking cessation, ending substance use). The study had two aims. The first aim was to evaluate whether cancer-specific intimacy mediated the associations between the three support-related communication variables (self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, and protective buffering) and psychological distress. Although we proposed that support-related communication and intimacy would play a significant role for both partners, we evaluated whether there were differences in these associations by evaluating social role (i.e., whether the person being evaluated is the patient or the partner) in our model. The second aim was to evaluate whether global intimacy mediated the association between support-related communication (self-disclosure, perceived partner disclosure, protective buffering) and psychological distress. We proposed that global intimacy would mediate the association between the three support-related communication variables and psychological distress, and, as with our analyses for cancer-specific intimacy, we evaluated whether there were differences between patients and partners with regard to the role of support-related communication and intimacy in psychological distress. In both models, we predicted that self-disclosure and perceived partner disclosure would be associated with increased intimacy, which in turn would be associated with decreased distress, and that protective buffering would be associated with decreased intimacy, which in turn would be associated with increased distress. As noted above, we examined cancer-specific and general closeness separately in this initial examination of the model because we hypothesized that couples evaluate cancer-related relationship experiences separately from non-cancer related relationship experiences. We did not have specific predictions about role effects.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model testing moderated mediation.

Methods

Participants

The sample was comprised of head and neck or lung cancer patients undergoing active treatment at a cancer center in the northeastern United States and their significant others. Patients were eligible if they were: age 18 years or older; married or living with a significant other of either gender; had a Karnofsky Performance Status [38] of 80 or above or an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score of 0 or 1 [39], and were English speaking.

In all, 370 couples were approached to participate. One hundred and nine consented and completed the survey (29.4% acceptance). The most common reasons for refusal were that the study would take “too much time” (10% of the patients who provided reasons gave this as the reason) and that the patient felt too ill (10.6% of the patients who provided reasons gave this as the reason). Comparisons were made between patient participants and refusers on available data (i.e., age, ethnicity, cancer stage and type, time since diagnosis). No significant differences were found.

Differences between heterosexual and same-sex couples on the major study variables were examined as were differences between married couples and non-married cohabiting couples. No differences were found. Therefore, data from all the couples who participated were included in subsequent analyses.

Procedures

Participants were recruited for study participation from oncologists practicing at a comprehensive cancer center in northeast Pennsylvania. Participants were identified and approached by the research assistant either after an outpatient visit or by telephone. If patient and partner were interested, they were provided with a written informed consent and the study questionnaire to complete and return by mail. All participants signed an informed consent approved by an Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) for patients and partners on all the measures are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, Alphas, and Correlations for Patients and Partners

| Patients | Partners | Patient | Partner | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Cronbach’s Alpha |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1. Protective Buffering1 | 25.98±6.90 | 33.10±7.66 | .81 | .87 | .21* | −.05 | −.003 | −.19 | −.01 | .10 | −.04 |

| 2. Self-Disclosure1 | 15.44±5.17 | 13.69±5.29 | .90 | .89 | −.16 | .12 | .59** | .39** | .39** | −.12 | .11 |

| 3. Perceived Partner disclosure | 14.92±5.62 | 13.91±5.56 | .92 | .92 | −.09 | .70** | −.01 | .40** | .43** | −.21* | .11 |

| 4. Global Intimacy 1 | 4.14±.80 | 3.76±.90 | .84 | .88 | −.21* | .41** | .45** | .35** | .68** | −.50** | .20* |

| 5. Cancer-specific Intimacy 1 | 12.25±2.47 | 11.48±3.20 | .91 | .86 | −.16 | .60** | .49** | .65** | .44** | −.52** | .24* |

| 6. Global Distress 1 | 10.39±8.78 | 7.82±8.03 | .88 | .90 | .39** | −.22* | −.13 | −.14 | −.14 | .21* | −.27** |

| 7. Age | 61.76±10.01 | 59.19±10.37 | -- | -- | −.05 | −.09 | −.02 | .04 | .09 | −.20* | .88** |

| 8. Functional Impairment (Patients only) | 26.18±17.17 | -- | .91 | -- | .35** | −.01 | .04 | .09 | .03 | .52** | −.10 |

Note: p≤.01;

p≤.05; Correlations for patients are on the lower diagonal, correlations for partners are on the upper diagonal, and paired correlations (between patients and partners) are on the diagonal.

Mean scores for patients and partners significantly differed; p ≤ .01.

Physical impairment

The 26-item functional status subscale of the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) [40] assessed patients’ physical disability caused by the cancer and its treatment. Patients rated the degree to which they experienced difficulty during the past month from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicating greater functional impairment. Impairment was included as a possible medical covariate in the analyses because greater impairment may be associated with greater psychological distress.

Perceived self-disclosure

We used a 3-item measure adapted from Laurenceau and colleagues [41] and used in our previous research [42]. Participants rated how much they disclosed thoughts, information, and feelings and concerns about cancer in the past week on a scale ranging from 1 to 7 with higher scores indicating greater levels of disclosure. Cronbach’s alphas in the present study were similar to those reported in our research with early stage breast cancer patients and their partners (cronbach’s alphapatients= .86; cronbach’s alphapartners= .85) [42] and those reported by the scale’s authors (cronbach’s alphawives= .84; cronbach’s alphahusbands= .82) [43].

Perceived partner disclosure

We used a 3-item measure adapted from Laurenceau and colleagues [41] and used in our previous research [42]. Participants rated the degree to which their partner disclosed thoughts, information, and feelings and concerns about cancer to them in the past week on a scale ranging from 1 to 7 with higher scores indicating greater perceived partner disclosure. Cronbach’s alphas in the present study are higher than those reported in our research with early stage breast cancer patients and their partners (.77 for patient, .70 for partner) [42] and internal consistency reported by the scale’s authors in their studies using community samples of married couples (.77 for patient, .76 for partner) [43].

Protective Buffering

This 10-item scale was adapted from Coyne and colleagues’ work [44]. The scale measures the degree to which individuals hide concerns and negative feelings and avoid arguments with their partner and has been used in our prior work with cancer patients [45, 46]. Participants rated their responses in the past week on a scale ranging from 1 to 5 with higher scores indicating a greater frequency. Sample items are, “I try to hide my own distress about the cancer experience, so as to not upset my partner,” “I tend to give in during discussions or arguments.” Cronbach’s alphas were similar to those reported in previous work with early stage breast cancer patients and their partners (.80 –.89) [47], work with patients diagnosed with breast, lung, or colorectal cancers (.82 for patients, .89 for partners)[45] and research on couples coping with myocardial infarction (.91 for patients, .92 for partners)[48].

Cancer-Specific Relationship Intimacy

This two item measure was adapted from Laurenceau and colleagues [41] in their work using community samples of married couples and has been used in our previous research focusing on early stage breast cancer patients and their partners [42]. Previous work has used a single item indicator of this construct. We added an additional item “How emotionally intimate did you feel with your partner?” Participants rated the degree to which they felt close and emotionally intimate with their partner in the past week when talking about cancer on a scale from 1 to 7 with higher scores indicating greater intimacy. Because previous studies used a single item scale, we were not able to compare scale reliability with previous work.

Global Relationship Intimacy

The Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships intimacy scale (PAIR) [49] is a 7-item scale assessing emotional closeness. This scale has been used in a number of studies of relationship intimacy among healthy married couples [43, 50, 51]. The scale has demonstrated good internal consistency in previous work focusing on women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer and their partners (cronbach’s alphapatients= .90; cronbach’s alphapartners=.88)[29] and men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners (cronbach’s alphapatients=.88, cronbach’s alphapartners= .83, partners)[52].

Distress

The BSI-18 is a brief version of the BSI-53 [53]. It yields a global rating of psychological distress called the Global Severity Index (GSI) and a normalized T-score is used in analyses. The scale has illustrated excellent reliability [23]. The cutoff for clinically-significant levels of distress is a T-score ≥ 63 or two subscale scores ≥ 63 which translated to a score of 19 or greater for male partners, 22 or greater for female partners, 18 or greater for male patients, and 23 or greater for female patients [53].

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics (e.g., means, standard deviations, and correlations) were calculated for each of the major study variables. Because data from couples tend to be related, analyses must adjust for this non-independence so that statistical significance tests are not biased. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) accomplishes this by utilizing a multilevel modeling approach in which data from two dyad members are treated as nested scores within the same group (i.e., the couple; [54]). Essentially, the APIM estimates two kinds of effects: actor effects and partner effects. Actor effects are within-person main effects: They represent the influence of an individual’s level of a predictor variable (e.g., one’s self-disclosure) on that individual’s level of an outcome variable (e.g., one’s perceptions of relationship intimacy). Partner effects are between-person main effects: They represent the influence of an individual’s level of a predictor (e.g., one’s self-disclosure) on that individual’s partner’s level of the outcome variable (e.g., one’s partner’s perceptions of relationship intimacy). Because actor and partner effects represent the overall effects of one’s behavior on one’s own or a partner’s outcomes, interactions between these effects and within-dyad variables such as social role (i.e., whether the actor or partner is a patient or a spouse) can then be examined [36].

The APIM is rooted in regression [55], so it can be extended to include moderators, control variables, and mediators. We were interested in all of these possibilities. For example, a key question was whether intimacy mediates associations between the actor and partner effects of support-related communication on distress after controlling for medical and demographic variables. A series of analyses were conducted to examine the actor and partner effects of the communication variables (e.g., self-disclosure, protective buffering) on distress and to evaluate whether intimacy (general or cancer-specific) mediated this association. We only examined the actor effects of perceived partner disclosure because that variable already assesses one’s perceptions of a partner’s behaviors and partner effect analyses would not be meaningful. In total, 6 mediational models were tested. Because we were interested in determining whether the associations between communication and intimacy and/or the associations between intimacy and distress differed for patients and partners, we extended the basic APIM model to test for moderated mediation. Figure 1 displays the conceptual model for the analysis. As Muller and colleagues [56] explain, moderated mediation occurs when the ‘A’, ‘B’, or ‘A’ and ‘B’ mediational paths are moderated by a third variable. Specifically, to test for moderated mediation of the ‘A path’, we examined whether there was a significant interaction between the predictor (i.e., actor or partner reports of spousal communication) and the moderator (social role) on the mediator (actor’s intimacy), and whether there was a significant main effect of the mediator (actor’s intimacy) on the criterion (actor’s distress; BSI GSI scores). To determine whether there was moderated mediation of the ‘B path’, we examined whether there was a significant association between the predictor and the mediator, and whether there was a significant interaction between the mediator and the moderator on the outcome. Following Muller and colleagues [56], the predictor variables were centered at their sample mean and contrast coding was used for social role (patient = 1 and partner = −1). All analyses were conducted using the MIXED procedure in SPSS 16.0.

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 details the sample characteristics. Almost half of the patients were diagnosed with head and neck cancer and half were diagnosed with lung cancer. Twenty-nine percent were diagnosed with localized disease (stage I or II), and the remainder had advanced disease. The average time since initial diagnosis was approximately one year (M= 1.1 years, SD = 1.7 years, range = less than one month -12 years). Approximately half of the sample had physician-rated ECOG score of 0 (asymptomatic and fully active)(n = 59, 54.5%) and the other half of the sample had physician- rated ECOG score of 1 (symptomatic; fully ambulatory; restricted in physically strenuous activity) (n =50, 45.9). The average relationship length was approximately 31 years (Mpatients= 32.0, SD = 14.5 years, range = 3 to 55 years; Mpartners= 31.8 years, SD = 14.6, range = 2– 55 years).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Patients | Partners | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 41 | 37.6 | 72 | 66.1 | ||||

| Male | 68 | 62.4 | 37 | 33.9 | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 101 | 92.7 | 101 | 95.3 | ||||

| Non-white | 7 | 7.3 | 5 | 4.7 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Grade school | 2 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Partial high school | 9 | 8.3 | 1 | 0.1 | ||||

| High school | 31 | 28.7 | 41 | 38.0 | ||||

| Some college | 22 | 20.4 | 22 | 20.4 | ||||

| College | 17 | 15.7 | 13 | 12.0 | ||||

| Post-graduate | 27 | 25.1 | 31 | 28.7 | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 104 | 95.4 | 104 | 95.4 | ||||

| Co-habitating | 5 | 4.6 | 5 | 4.6 | ||||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||

| Heterosexual | 105 | 96.3 | 105 | 96.3 | ||||

| Homosexual | 4 | 3.7 | 4 | 3.7 | ||||

| Cancer type | ||||||||

| Head or neck | 57 | 52.3 | ||||||

| Lung | 52 | 47.7 | ||||||

| Stage of disease | ||||||||

| 1 | 18 | 16.5 | ||||||

| 2 | 14 | 12.8 | ||||||

| 3 | 38 | 34.9 | ||||||

| 4 | 39 | 35.8 | ||||||

| Recurrence status | ||||||||

| Yes | 7 | 6.4 | ||||||

| No | 96 | 88.1 | ||||||

| Missing | 6 | 5.5 | ||||||

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 1.1 | 1.7 | ||||||

| Patient ever smoked | ||||||||

| Yes | 92 | 84.4 | ||||||

| No | 17 | 15.6 | ||||||

Table 2 presents descriptive information for patients and partners for the major study variables. Overall, patients reported low functional impairment and patients and partners reported moderate levels of cancer and global intimacy and low levels of psychological distress. Paired t-tests were conducted to determine if patients and partners significantly differed on any of the major study variables. Partners reported engaging in more protective buffering than patients. Patients reported greater self-disclosure, global intimacy, cancer intimacy, and distress.

Twenty patients (18.3%) and ten spouses (9.3%) met the BSI criteria for psychological distress. However, couple-based rates were higher. There were 28 couples (25.7%) where the patient, spouse, or both were distressed.

Table 2 also shows correlations on the major study variables; correlations for partners are above the diagonal, correlations for patients are below the diagonal, and paired correlations (between patients’ and partners’ scores) are on the diagonal. Overall, low to moderate associations between support-related communication, intimacy, and distress were found. Of note, global and cancer-specific intimacy were significantly negatively correlated with partner distress but they were not significantly correlated with patient distress.

Correlations between intimacy, distress, and demographic (i.e., age, income, length of relationship) and medical factors (i.e., time since diagnosis, patient functional impairment) were examined, as were mean differences on the intimacy and distress based on gender, ethnicity, employment status, type of cancer (lung or head and neck cancer), disease stage, type of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or combined modality) and whether the patient ever smoked. Variables with p-values less than .05 (i.e., patient functional impairment, age, patient smoking status at the time of diagnosis, and type of cancer) were retained as model covariates.

APIM Mediation and Moderated Mediation Results

Does Cancer-Specific Intimacy Mediate the Association Between Communication and Distress for Patients and Partners?

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of our tests of APIM mediation and moderated mediation for cancer-specific intimacy. Mediation requires a significant association between the predictor and criterion, and regardless of the communication variable examined, only actors’ (not partners’) communication was significantly associated with distress (see Step 1). Likewise, according to Muller and colleagues [56] moderated mediation of the ‘A path’ requires a significant interaction between the predictor and the moderator. None of the interactions between actors’ communication and social role were significant (see Step 2). Thus, for simplicity, only the details of analyses involving the actor effects of communication and tests of moderated ‘B path’ mediation (as illustrated in Figure 1) are described below.

Table 3.

Tests of Mediation and Moderated Mediation: Cancer-specific Intimacy as Mediator

| Step 1 (Criterion = BSI) | Step 2 (Criterion = Cancer specific Intimacy) | Step 3 (Criterion = BSI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | b | t | b | T | |

| Self Disclosure (SD) | ||||||

| Intercept | 15.73 | 8.00 | 12.22 | |||

| Patient Functional Impairment (CARES) | .14 | 4.48*** | .01 | .52 | .14 | 4.90*** |

| Actor’s Age | −.19 | −3.60*** | .05 | 2.52** | −.15 | −2.86*** |

| Patient Smoking Status | 3.28 | 2.22* | −.14 | −.27 | 2.98 | 2.11* |

| Type of Cancer (Lung or HN) | 1.42 | 1.29 | .79 | 2.08* | 2.06 | 1.95* |

| Actor’s SD | −.32 | −3.26*** | .23 | 7.47*** | −.14 | −1.20 |

| Partner’s SD | .06 | .64 | .11 | 3.53*** | .15 | 1.52 |

| Social Role | 2.00 | 3.85*** | .22 | 1.55*** | 2.13 | 4.26*** |

| Actor’s SD × Social Role | −.11 | −1.10 | .06 | 1.57 | −.18 | −1.59 |

| Partner’s SD × Social Role | .10 | 1.05 | −.03 | −0.89 | .03 | 0.27 |

| Cancer-specific Intimacy | −.80 | −3.46*** | ||||

| Cancer-specific Intimacy × Social Role | .45 | 2.04* | ||||

| Perceived Partner Disclosure (PPD) | ||||||

| Intercept | 14.58 | 8.53 | 11.26 | |||

| Patient Functional Impairment (CARES) | .14 | 4.54*** | .01 | .86 | .15 | 5.05*** |

| Actor’s Age | −.17 | −3.24*** | .03 | 1.79^ | −.14 | −2.66** |

| Patient Smoking Status | 3.45 | 2.28* | −.10 | −.19 | 3.31 | 2.32* |

| Type of Cancer (Lung or HN) | 1.33 | 1.19 | .93 | 2.23* | 2.04 | 1.89^ |

| Actor’s PPD | −.22 | −2.34* | .18 | 5.96*** | −.03 | −.34 |

| Social Role | 1.79 | 3.48*** | .27 | 1.84^ | 1.92 | 3.91*** |

| Actor’s PPD × Social Role | −.03 | −.26 | .01 | .26 | −.13 | −1.24 |

| Cancer-specific Intimacy | −.86 | −4.08*** | ||||

| Cancer-specific Intimacy × Social Role | .39 | 1.92^ | ||||

| Protective Buffering (PB) | ||||||

| Intercept | 15.41 | 7.36 | 11.29 | |||

| Patient Functional Impairment (CARES) | .10 | 3.28*** | .02 | 1.67^ | .13 | 4.10*** |

| Actor’s Age | −.18 | −3.46*** | .04 | 2.07* | −.14 | −2.78** |

| Patient Smoking Status | 2.60 | 1.75^ | .51 | .80 | 2.83 | 1.98* |

| Type of Cancer (Lung or HN) | 1.51 | 1.41 | .80 | 1.74^ | 2.30 | 2.23* |

| Actor’s PB | .21 | 2.77** | −.03 | −1.07 | .18 | 2.54* |

| Partner’s PB | .95 | 1.28 | −.06 | −2.17* | .03 | .47 |

| Social Role | 2.07 | 3.20*** | .45 | 2.46* | 2.42 | 4.03*** |

| Actor’s PB × Social Role | 1.29 | 1.75^ | −.03 | −1.00 | .12 | 1.70^ |

| Partner’s PB × Social Role | .11 | 1.49 | .04 | 1.40 | .15 | 2.11* |

| Cancer-specific Intimacy | −.86 | −4.60*** | ||||

| Cancer-specific Intimacy × Social Role | .35 | 1.98* | ||||

Note. p ≤.005;

p ≤.01;

p ≤.05,

p ≤ .10

Self-Disclosure

As Table 3 shows, there were significant actor effects for self-disclosure. Regardless of social role, individuals who reported greater self-disclosure also reported lower levels of distress (Step 1) and greater cancer-specific intimacy (Step 2). Individuals who reported greater cancer-specific intimacy also reported lower levels of distress after controlling for actors’ self-disclosure (Step 3). Using the statistical methods recommended by MacKinnon and colleagues to test mediation [57, 58], cancer-specific intimacy was found to fully mediate the association between actors’ self-disclosure and distress (Sobel’s Z = 3.12, p = .002). The total effect of self-disclosure and cancer-specific intimacy on distress was estimated to be −.32 and the mediated effect was −.18. Based on decomposition of the total effect into direct and indirect effects, we calculated that 58% of the overall relationship between self-disclosure and distress was explained by cancer-specific intimacy.

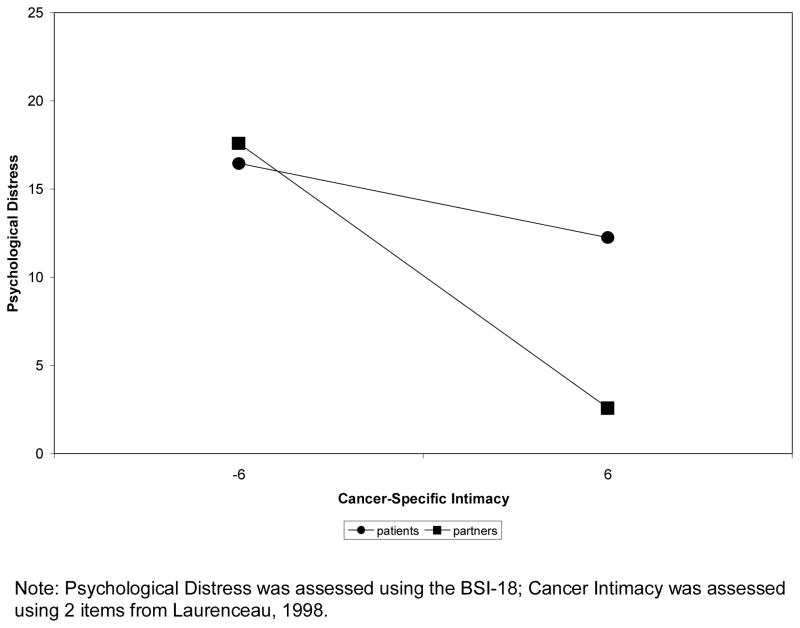

Having established that self-disclosure was significantly associated with cancer-specific intimacy in Step 2, the interaction between cancer-specific intimacy and social role (after controlling for cancer intimacy; Step 3) was examined and found to be significant (t (180) = 2.04, p = .04), satisfying Muller and colleague’s [56] criteria for moderated mediation. To test the simple slopes of the interaction, we used the procedures outlined by Preacher, Curran, & Bauer [59], developed specifically for multilevel models. Unlike the traditional approach outlined by Aiken and West [60] that requires inputting values that are 1 SD above and below the mean of the predictor, this technique allows inputting the upper and lower possible values of the predictor (here, cancer-specific intimacy was centered, so we used the values 6 and −6) in the simple slope calculation. As Figure 2 shows, patients who reported more cancer-specific intimacy had less distress; however, the slope was not significant (b patients = −.35, t (180) = −.94, p =.35). Partners who reported more cancer-specific intimacy also had less distress than partners who reported less cancer-specific intimacy, and the slope was significant (b partners = −1.25, t (180)=−5.10, p=.001).

Figure 2.

Results of multilevel analysis regressing BSI GSI scores on patient and partner reports of cancer-specific intimacy.

Perceived Partner Disclosure

As Table 3 shows, there were significant actor effects for perceived partner disclosure. Regardless of social role, greater perceived partner disclosure was associated with lower levels of distress (Step 1) and higher levels of cancer-specific intimacy (Step 2). Greater cancer-specific intimacy was also associated with lower distress after controlling for perceived partner disclosure (Step 3). Cancer-specific intimacy fully mediated the association between perceived partner disclosure and distress (Sobel’s Z = 3.33, p =.001). The total effect was −.18 and the mediated effect was −.15. Thus, 84% of the overall relationship between perceived partner disclosure and distress was explained by cancer-specific intimacy.

Having established that self-disclosure was significantly associated with cancer-specific intimacy in Step 2, the interaction between cancer-specific intimacy and social role (after controlling for cancer-specific intimacy) was examined in Step 3 to test for moderated mediation. This interaction was marginally significant (t (180) =1.92, p =.06).

Protective Buffering

Although protective buffering was significantly positively associated with distress (see Table 3, Step 1), it was not significantly associated with cancer-specific intimacy (Step 2). Thus, cancer-specific intimacy did not mediate the association between actors’ protective buffering and distress.

Does Global Intimacy Mediate the Association Between Communication and Distress for Patients and Partners?

The analyses testing global intimacy as a mediator proceeded in the same fashion as those for cancer-specific intimacy. As with the previous analyses, only actors’ (not partners’) communication was significantly associated with distress in Step 1 and none of the interactions between actors’ communication and social role were significant in Step 2. Thus, Table 4 provides a comprehensive overview of the analyses; but for simplicity, only the details of analyses involving the actor effects of communication and tests of moderated ‘B path’ mediation (as illustrated in Figure 1) are described below.

Table 4.

Tests of Mediation and Moderated Mediation: Global Intimacy as Mediator

| Step 1 (Criterion = BSI) | Step 2 (Criterion = Global Int) | Step 3 (Criterion = BSI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | b | t | b | T | |

| Self Disclosure (SD) | ||||||

| Intercept | 15.73 | 3.12 | 13.15 | |||

| Patient Functional Impairment | .14 | 4.48*** | −.001 | −.37 | .13 | 4.42*** |

| Actor’s Age | −.19 | −3.60*** | .01 | 1.89^ | −.15 | −3.06*** |

| Patient Smoking Status | 3.28 | 2.22* | .16 | .94 | 3.65 | 2.58** |

| Type of Cancer (Lung or HN) | 1.42 | 1.29 | .01 | .11 | 1.39 | 1.33 |

| Actor’s SD | −.32 | −3.26*** | .06 | 5.93*** | −.17 | −1.60 |

| Partner’s SD | .06 | .64 | .03 | 2.83*** | .13 | 1.30 |

| Social Role | 2.00 | 3.85*** | .16 | 3.45*** | 2.40 | 4.53*** |

| Actor’s SD × Social Role | −.11 | −.1.10 | .001 | .12 | −.18 | −1.67^ |

| Partner’s SD × Social Role | .10 | 1.05 | −.01 | −.94 | .06 | .56 |

| Global Intimacy | −2.46 | −3.68*** | ||||

| Global Intimacy × Social Role | 1.21 | 1.80^ | ||||

| Perceived Partner Disclosure (PPD) | ||||||

| Intercept | 14.58 | 3.25 | 12.17 | |||

| Patient Functional Impairment | .14 | 4.54*** | −.0003 | −.09 | .14 | 4.65*** |

| Actor’s Age | −.17 | −3.24*** | .01 | 1.41 | −.14 | −2.79** |

| Patient Smoking Status | 3.45 | 2.28* | .14 | .80 | 3.90 | 2.69** |

| Type of Cancer (Lung or HN) | 1.33 | 1.19 | .06 | .44 | 1.33 | 1.25 |

| Actor’s PPD | −.22 | −2.34* | .05 | 5.39*** | −.06 | −.59 |

| Social Role | 1.79 | 3.48*** | .16 | 3.36*** | 2.21 | 4.20*** |

| Actor’s PPD × Social Role | −.03 | −.26 | .001 | .18 | −.08 | −.78 |

| Global Intimacy | −2.79 | −3.88*** | ||||

| Global Intimacy × Social Role | 1.04 | 1.56 | ||||

| Protective Buffering (PB) | ||||||

| Intercept | 15.41 | 3.00 | 12.63 | |||

| Patient Functional Impairment | .10 | 3.28*** | .003 | .78 | .11 | 3.46*** |

| Actor’s Age | −.18 | −3.46*** | .01 | 1.86^ | −.14 | −2.87*** |

| Patient Smoking Status | 2.60 | 1.75^ | .22 | 1.14 | 3.04 | 2.14* |

| Type of Cancer (Lung or HN) | 1.51 | 1.41 | .01 | .10 | 1.50 | 1.48 |

| Actor’s PB | .21 | 2.77** | −.02 | −2.86*** | .16 | 2.14* |

| Partner’s PB | .95 | 1.28 | −.003 | −.47 | .09 | 1.20 |

| Social Role | 2.07 | 3.20*** | .11 | 1.83^ | 2.38 | 3.77*** |

| Actor’s PB × Social Role | 1.29 | 1.75^ | −.001 | −.19 | .15 | 2.14** |

| Partner’s PB × Social Role | .11 | 1.49 | .01 | 1.04 | .13 | 1.87^ |

| Global Intimacy | −2.64 | −4.35*** | ||||

| Global Intimacy × Social Role | 1.22 | 1.99* | ||||

Note: Int – Intimacy;

p ≤ .005;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .10

Self-Disclosure

Table 4 shows the significant actor effects for self-disclosure. Regardless of social role, greater self-disclosure was associated with less distress (Step 1) and greater global intimacy (Step 2). Greater global intimacy was also associated with less distress after controlling for self-disclosure (Step 3). Thus, global intimacy fully mediated the association between actors’ self-disclosure and distress (Sobel’s Z =3.10, p = .002). The total effect was −.32 and the mediated effect was −.15. In all, 46% of the overall relationship between self-disclosure and distress was explained by global intimacy [61].

Having established a significant association between self-disclosure and global intimacy in Step 2, we examined the interaction between global intimacy and social role (after controlling for global intimacy) in Step 3 to test for moderated mediation. The interaction was marginally significant (t (188) = 1.80, p = .07).

Perceived Partner Disclosure

As Table 4 shows, significant actor effects were found for perceived partner disclosure. Regardless of social role, greater perceived partner disclosure was associated with lower levels of distress (Step 1) and higher levels of global intimacy (Step 2). Greater global intimacy was also associated with less distress after controlling for perceived partner disclosure (Step 3). Thus, global intimacy fully mediated the association between perceived partner disclosure and distress (Sobel’s Z = 2.44, p = .01). The total effect was −.20 and the mediated effect was −.14. Thus, 70% of the overall relationship between perceived partner disclosure and distress was explained by global intimacy.

Having established that protective buffering was significantly associated with global intimacy in Step 2, the interaction between global intimacy and social role (after controlling for global intimacy) was examined to test for moderated mediation. Although the interaction was in the same direction as the previous analysis, it was not significant (t (192) = 1.56, p = .12).

Protective Buffering

As Table 4 (Step 1) shows, there were significant actor effects for protective buffering. Regardless of social role, more protective buffering was associated with greater distress (Step 1) and less global intimacy (Step 2). Less global intimacy was also associated with greater distress after controlling for protective buffering (Step 3). Global intimacy was found to partially mediate the association between protective buffering and distress (Sobel’s Z = 2.35, p = .02). The total effect was .21 and the mediated effect was .05. Thus, 25% of the overall relationship between protective buffering and distress was explained by global intimacy.

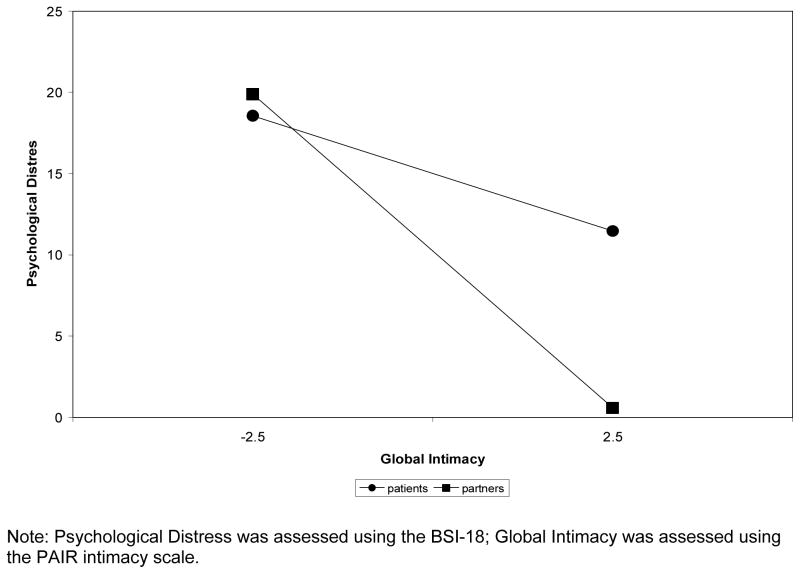

Having established that protective buffering was significantly associated with global intimacy in Step 2, the interaction between global intimacy and social role (after controlling for global intimacy; Step 3) was examined and found to be significant (t (189) =1.99, p = .05), satisfying Muller and colleague’s [56] criteria for moderated mediation. Again, using the procedures outlined by Preacher, Curran, & Bauer [59], we used the upper and lower possible values of the centered predictor, global intimacy (2.5 and −2.5) to test the simple slopes of the interaction. As Figure 3 shows, patients who reported more global intimacy had less distress than patients who reported less global intimacy, however, the slope was not significant (b patients = −1.42, t (189) = −1.61, p = .11). Partners who reported more global intimacy also had less distress than partners who reported less global intimacy, and the slope was significant (b partners = −3.86, t (189) = −4.61, p = .001).

Figure 3.

Results of multilevel analyses regressing BSI GSI scores on patient and partner reports of global intimacy.

Discussion

We evaluated the relationship intimacy model of couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer [29] in a sample of head and neck or lung cancer patients and their partners. Our findings were largely consistent with the model in that global intimacy partially mediated the association between protective buffering and distress, and global and cancer-specific intimacy fully mediated the association between self- and perceived partner disclosure and distress. Together, these findings suggest that both types of intimacy may be beneficial for couples’ psychological adjustment. Interestingly, the associations between intimacy and distress were generally stronger for partners than for patients. In the discussion that follows, we will discuss the theoretical implications of these findings for the study of intimacy processes in couples coping with cancer, limitations of the present study, and potential clinical implications.

Definitions of intimacy have at least one aspect in common - the concept that relationship closeness develops from communication. Intimacy process models suggest that self-disclosure is a central communication strategy that couples use to develop and maintain intimacy [62, 63]. Our findings support the importance of self-disclosure of cancer-related facts and feelings in perceived relationship closeness for both patients and partners. They also extend previous work evaluating the role of self-disclosure in global relationship intimacy among couples coping with gastrointestinal cancers [33] and the role of self-disclosure in cancer-specific relationship intimacy among couples coping with early stage breast cancer [32] by suggesting that self-disclosure plays a key role in intimacy among couples dealing with head and neck cancers and by suggesting that self-disclosure is associated with both global and cancer-specific intimacy.

Intimacy process models propose that reciprocal disclosure, which has been conceptualized in many studies as the degree of perceived disclosure from one’s partner, is important to the development of relational intimacy [43, 64]. Our results are consistent with this hypothesis: when patients and spouses reported greater self-disclosure and perceived their partners to be disclosing more (i.e., the actor effects for self-disclosure and perceived partner disclosure were significant), they reported greater cancer-specific intimacy as well as enhanced perceptions of global relationship intimacy. These findings are also consistent with studies of women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer and their partners [32]. However, there have been different approaches adopted for defining partner disclosure and reciprocal disclosure. For example, some studies have defined partner disclosure as observational ratings of the partner’s actual self-disclosures [64]. These results suggest gender differences in that women’s intimacy was predicted by men’s disclosures, whereas men’s intimacy was not predicted by women’s disclosures. In the present study, we used paper-and-pencil methods and did not find evidence for “partner effects.” That is, intimacy and distress were associated with the perception of the partner’s disclosure rather than partner’s reports of their own disclosure. With regard to reciprocity, some studies have evaluated reciprocity of disclosure using sequential analyses (i.e., observed self disclosure from one partner followed by observed self-disclosure by the other partner) and have found that reciprocity contributes to lower distress among women diagnosed with breast cancer [42]. In the present study, we did not employ observational methods. However, the correlation for patient and partner reports of self-disclosure was not significant, which may indicate a low degree of reciprocal disclosure. Taken together, these studies suggest that findings are significantly influenced by the methodology used to assess and define partner disclosure and reciprocal disclosure.

The results for protective buffering were not entirely consistent with the relationship intimacy model of couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Although protective buffering predicted global intimacy and partially mediated the association between buffering and distress when global intimacy was evaluated, buffering was not associated with cancer-specific intimacy. In our previous work, we hypothesized that one way protective buffering about cancer-related concerns may increase distress for both partners is by reducing relational intimacy [37]. The present findings are partially consistent with this hypothesis: protective buffering was associated with lower levels of global and cancer-specific intimacy and with higher levels of distress, and global intimacy partially mediated the association between protective buffering and distress (accounting for 25% of the association between protective buffering and distress). Our finding that protective buffering was not associated with cancer-specific distress may reflect the fact that this measure assessed attempts to avoid conflicts with the partner that are both cancer- and not cancer-related. The global nature of some of buffering behaviors may have interfered with global relationship closeness as compared with cancer-specific closeness. At the same time, the relatively small amount of variance in the association between protective buffering and distress accounted for by global intimacy suggests that other potential mechanisms should be examined. Other possible mechanisms may include lower levels of perceived spouse support and assistance as well as lower levels of support from other family and friends (if buffering also occurs in other relationships). Future studies may benefit from both refining the protective buffering measure to determine if the inclusion of cancer and non-cancer related protective buffering items would provide a better measure of this construct, and future studies may benefit from evaluating whether the motives for engaging in protective buffering are motivated by the cancer experience or not.

Overall, participants reported a low degree of psychological distress despite patients’ increased mortality risk. However, in one-quarter of the couples we sampled (25.7%) at least one partner was distressed, suggesting that this population of cancer patients may represent an important target for future couple-based interventions. As can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, there were stronger associations between intimacy and distress among partners than patients. An examination of these figures indicates that partners who reported low levels of global and cancer-specific intimacy reported very high levels of distress whereas partners who reported high levels of global and cancer-specific intimacy reported almost no distress. Although significant interactions between social role (patient versus partner) and intimacy effects were not universal, the pattern across communication variables was consistent. As other studies have not evaluated the importance of relationship intimacy between patients and partners, it is difficult to compare our findings with the previous literature. There are at least two possible explanations for these findings. The first explanation is the illness context, which in this case, consists primarily of individuals diagnosed with advanced cancers which have high morbidity and poor long term prognosis. Increasing disability and the threat of the possible loss of one’s partner may increase attachment worries and increase the desire for closeness [65, 66]. That is, relationship intimacy may take on a more important role for partners in these specific types of cancer. The second explanation is the possible role of gender differences in the role of intimacy. Approximately 66% of the partners were female. Although research examining gender differences in the role of disclosure and intimacy has reported inconsistent findings [67], there is evidence that suggests that relationship intimacy is more important for women [43]. Future research might benefit from evaluating intimacy processes in a larger sample of individuals with other types of cancer.

Study Limitations

Before moving to clinical and conceptual implications, limitations should be noted. We employed a cross-sectional, non-experimental design; causal associations between disclosure, intimacy, and distress cannot be inferred. Although our findings were consistent with the predictions of the relationship intimacy model, they should be interpreted with caution. The cross-sectional nature of our study did not allow us to fully test other possible models. For example, it is possible that communication mediates the association between intimacy and distress or that distress influences communication and intimacy. Our future work seeks to build upon these preliminary findings by examining the role of communication and intimacy processes over time. Second, it is possible that that global relationship satisfaction may influence both communication and intimacy between partners. Future studies should evaluate the influence of global relationship satisfaction on relationship processes. A third limitation was that our acceptance rate was modest (29.4%). This rate is lower than other studies of couples coping with cancer (45% [68]; 38.4% [46]; 59% [14]). Although we did not find differences between study refusers and participants on the limited demographic and medical characteristics we assessed, it is possible that participating couples were less psychologically distressed and had more satisfactory marital relationships than couples who did not participate or differed in other important ways. There are a number of reasons our acceptance rate may have been lower. First, we did not compensate couples for their participation and it is possible that a small incentive may have improved return rates [69]. We have compensated couples in prior studies [70]. Second, these patient populations, particularly patients with head and neck cancers, have pre-existing medical and addictive issues that may reduce their interest in psychosocial studies. Enrollment in future studies may benefit from providing incentives as well as physician involvement in recruitment.

A fourth limitation was that the sample consisted primarily of white couples who had been married for 30 years or more and therefore we may not be able to generalize our findings to ethnic or racial minorities and/or couples in relationships of less duration. There was also a great deal of variability in the time since diagnosis, which may have influenced the relationship dynamics. Future studies may benefit from focusing on patients who are coping with a specific phase of treatment (e.g., newly diagnosed, recurrence, end of life). Fifth, our measures of self- and partner disclosure and cancer-specific intimacy were relatively brief (2–3 items) and lengthier measures may provide a better assessment of each construct. Sixth, although we found no significant differences between men and women on the major study variables, previous research suggests husband-wife differences in the effects of self-disclosure on perceptions of intimacy [42, 64]. Thus, future research may benefit from simultaneously evaluating gender and social role differences in intimacy processes. Seventh, we did not evaluate effects of different types of cancer-related disclosure separately (e.g., disclosure about fears about death, concerns about symptoms), and it is possible that disclosures about different topics had different effects. Finally, our sample included couples coping with head and neck or lung cancers. There may be differences in intimacy processes between these two populations, and future research may benefit from evaluating them separately.

Clinical and Conceptual implications

With regard to clinical implications, our findings suggest that improving reciprocal disclosure about cancer concerns and relationship intimacy are important targets for psychological intervention. Talking together about cancer affects not just perceptions of closeness regarding the cancer itself but it also seems to generalize to global perceptions of marital intimacy. Because global relationship intimacy affects couples’ distress, methods of increasing general feelings of relationship closeness such as spending time engaging in non-cancer related activities that the couple enjoys, reflecting on their shared past history and other positive aspects of their relationship not related to cancer, and other strategies to maintain intimacy and a sense of “normalcy” in the relationship may be beneficial [68, 71, 72]. Since intimacy has a greater impact on partners’ distress, couple-focused, intimacy-enhancing interventions may be particularly effective for partners of individuals with these two types of cancer.

From a conceptual perspective, our findings provide empirical support for the relationship intimacy model of couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer as well as for the interpersonal process model of intimacy. Future work should endeavor to use longitudinal approaches to understanding relationship processes which may be better able to capture the interactional nature of intimacy processes, and future studies should attempt to evaluate the role of other important factors such as perceived partner responsiveness, unsupportive behaviors, and relationship maintenance strategies as they are likely to affect relationship intimacy. Cancer-specific factors that may impact the quality and level of disclosure, such as the degree of facial disfigurement, limited ability to speak and swallow, the degree to which the illness interferes with the ability to engage in sexual activity such as kissing and oral stimulation, and the degree of partner blame for causing the cancer, should also be evaluated. Because both cancers may be caused by behavioral factors (smoking, alcohol use), it would be interesting to asses partner blame and criticism of the patient for his or her smoking or alcohol use as well as evaluate their influence on communication and intimacy in future studies.

Despite its limitations, this study had a number of strengths. First, head and neck and lung cancers are among the most psychologically debilitating cancers [73] and bolstering the knowledge base regarding contributing factors to distress among these patients and their caregivers is likely to become increasingly important. Second, data were collected and analyzed at the couple-level. Although some previous studies of relationship processes have collected data from both partners, analytic approaches have not traditionally been at the couple-level utilizing actor-partner approaches. Third, we have advanced what is known about the role of support-related communication, intimacy, and distress by evaluating all three components of the relationship intimacy model. Although future studies can advance the present findings by using longitudinal, structural equation modeling approaches, the current findings provide an initial evaluation of relationship intimacy processes and adaptation to cancer.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an Established Investigator in Cancer Prevention and Control Award to Sharon Manne by the NCI (K05 CA109008) and by a Cancer Prevention and Control Career Development Award by the NCI (K07 CA124668) to Hoda Badr.

References

- 1.Montazeri A, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with lung cancer before and after diagnosis: findings from a population in Glasgow, Scotland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(3):203–4. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uchitomi Y, et al. Depression after successful treatment for nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89(5):1172–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1172::aid-cncr27>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopwood P, Stephens R. Depression in patients with lung cancer: Prevalence and risk factors derived from quality-of-life data. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18:893–903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmack Taylor CL, et al. Lung cancer patients and their spouses: Psychological and relationship functioning within 1 month of treatment initiation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36(2):129–140. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergquist H, Ruth M, Hammerlid E. Psychiatric morbidity among patients with cancer of the esophagus or the gastro-esophageal junction: a prospective, longitudinal evaluation. Diseases of the Esophagus. 2007;20(6):523–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy S, et al. Depressive symptoms, smoking, drinking, and quality of life among head and neck cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):142–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarna L, et al. Quality of life and health status of dyads of women with lung cancer and family members. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33(6):1109–16. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.1109-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sehlen S, et al. Quality of life (QoL) as predictive mediator variable for survival in patients with intracerebral neoplasma during radiotherapy. Onkologie. 2003;26(1):38–43. doi: 10.1159/000069862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broberger E, et al. Spontaneous reports of most distessing concerns in patients with inoperable cancer: at present, in retrospect and in comparison with EORTC-QLQ-30+LC13. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(10):1635–45. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9266-5. Epub 2007 Oct 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braz D, et al. Quality of life and depression in patients undergoing total and partial laryngectomy. Clinics. 2005;60(2):135–142. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322005000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callahan C. Facial disfigurement and sense of self in head and neck cancer. Soc Work Health Care. 2004;40(2):73–87. doi: 10.1300/j010v40n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dropkin M. Body image and quality fo life after head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer Practice. 1999;7(6):309–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.76006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schliephake H, Jamil MU. Prospective evaluation of quality of life after oncologic surgery for oral cancer. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2002;31(4):427–33. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vickery LE, et al. The impact of head and neck cancer and facial disfigurement on the quality of life of patients and their partners. Head and Neck. 2003;25(4):289–96. doi: 10.1002/hed.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPerson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: Qualitative study. British Medical Journal. 2004;328:1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humphris G, et al. Fear of recurrence and possible cases of anxiety and depression in orofacial cancer patients. International Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery. 2003:486–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y, et al. Levels of depressive symptoms in spouses of people with lung cancer: Effects of personality, Social Support, and caregiving burden. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:123–130. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg T, et al. Prevalence of emotional distress in newly diagnosed lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drabe N, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in wives of men with long-term head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17(2):199–204. doi: 10.1002/pon.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verdonck-de Leeuw I, et al. Computerized prospective screening for high levels of emotional distress in head and neck cancer patients and referral rate to psychosocial care. Oral Oncology. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.012. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zwahlen RA, et al. Quality of life and psychiatric morbidity in patients successfully treated for oral cavity squamous cell cancer and their wives. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2008;66(6):1125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vickery L, et al. The impact of head and neck cancer and facial disfigurement on the quality of life of patients and their partners. Head Neck. 2003;25(4):289–96. doi: 10.1002/hed.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zabora J, et al. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cutrona C. Social support in couples: Marriage as a resource in times of stress. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasch LA, Bradbury TN. Social support, conflict, and the development of marital dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(2):219–230. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Figueiredo MI, Fries E, Ingram KM. The role of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:96–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison J, Maguire P, Pitceathly C. Confiding in crisis: Gender differences in pattern of confiding among cancer patients. Social Science Medicine. 1995;41(9):1255–1260. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00411-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pistrang N, Barker C. Disclosure of concerns in breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1992;1:183–192. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manne SL, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(S11):2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reis R, Patrick B. Attachment and intimacy: Component processes. In: Higgins E, Kruglanski A, editors. Social Psychology: Handbook of basic principles. Wiley; England: 1996. pp. 523–563. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reis H, Shaver PR. Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In: Duck S, editor. Handbook of Personal Relationships: Theory, Research and Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1988. pp. 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manne SL, et al. Couples’ support-related communication, psychological distress and relationship satisfaction among women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(4):660–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porter L, et al. Disclosure between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their spouses. Psychooncology. 2005;14(12):1030–42. doi: 10.1002/pon.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kayser K, Sormanti M, Strainchamps E. Women Coping With Cancer: The Influence of Relationship Factors on Psychosocial Adjustment. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1999;23:725–729. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagedoorn M, et al. Marital satisfaction in patients with cancer: Does support from intimate partners benefit those who need it most? Health Psychology. 2000;19:274–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langer S, Rudd M, Syrjaia K. Protective buffering and emotional desynchrony among spousal caregivers of cancer patients. Health Psychol. 2007;26(5):635–43. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manne SL, et al. Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: The moderating role of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(3):380–388. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: CM M, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Columbia University Press; New York: 1949. pp. 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zubrod CG, et al. Appraisal of methods for the study of chemotherapy of cancer in man: Comparative therapeutic trial of nitrogen mustard and triethylene thiophosphoramide. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1960;11:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schag CA, Ganz PA, Heinrich RL. Cancer rehabilitation evaluation system-short form (CARES-SF): A cancer specific rehabilitation and quality of life instrument. Cancer. 1991;68(6):1406–1413. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910915)68:6<1406::aid-cncr2820680638>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Pietromonaco PR. Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(5):1238–1251. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manne SL, et al. The interpersonal process model of intimacy: The role of self-disclosure, partner disclosure and partner responsiveness in interactions between breast cancer patients and their partners. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:589–599. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Rovine M. The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: a daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(2):314–323. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Pietromonaco PR. Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1238–1251. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manne SL, et al. Hiding worries from one’s spouse: Protective buffering among cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer Research Therapy and Control. 1999;8:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manne SL, et al. Partner unsupportive responses, avoidant coping, and distress among women with early stage breast cancer: patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychology. 2005;24(6):635–41. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manne SL, Ostroff J, Winkel G. Social-cognitive processes as moderators of a couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2007;26(6):735–44. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coyne JC, Smith DAF. Couples coping with a myocardial infarction:A contextual perspective on wives’ distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(3):404–412. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaefer MT, Olson DH. Assessing intimacy: The pair inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1981:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talmadge L. Intimacy, conversational patterns, and concomitant cognitive/emotional processes in couples. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9(4):473–488. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greeff A, Malherbe H. Intimacy and marital satisfaction in spouses. Journal of Sex Marital Therapy. 2001;27(3):247–57. doi: 10.1080/009262301750257100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manne SL, et al. Couples at risk for long-term psychological distress following early stage breast cancer: The role of relationship communication and marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. under review. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Derogatis L. BSI 18 administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kenny D, Kashy DA, Cook D. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kashy DA, Kenny DA. The analysis of data from dyads and groups. In: Reis HT, Judd C, editors. Handbook of research methods in social psychology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1997. pp. 451–477. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muller D, Judd C, Yzerbyt V. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89(6):852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30(1):41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31(4):437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. London: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chelune GJ, Robinson JT, Kommor MJ. A cognitive interactional model of intimate relationships. In: Derlega VJ, editor. Communication, intimacy, and close relationships. Academic Press; New York: 1984. pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waring EM, Chelune GJ. Marital intimacy and self-disclosure. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1983;39(2):183–90. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198303)39:2<183::aid-jclp2270390206>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitchell AE, et al. Predictors of intimacy in couples’ discussions of relationship injuries: an observational study. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22(1):21–9. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Johnson S. Facilitating Intimacy: Interventions and effects. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1994;20:170–180. [Google Scholar]

- 66.McLean LM, Jones JM. A review of distress and its management in couples facing end-of-life cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:603–616. doi: 10.1002/pon.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clark M, Reis H. Interpersonal processes in close relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 1988;39:609–672. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.003141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Badr H, Acitelli LK, Taylor CL. Does talking about their relationship affect couples’ marital and psychological adjustment to lung cancer? J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(1):53–64. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shaw MJ, et al. The use of monetary incentives in a community survey: impact on response rates, data quality, and cost. Health Services Research. 2001;35(6):1339–1346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Manne SL, et al. Couple-Focused Group Intervention for Women with Early Stage Breast Cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(4):634–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Badr H, Acitelli LK. Dyadic adjustment in chronic illness: does relationship talk matter? J Fam Psychol. 2005;19(3):465–9. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Badr H, Carmack Taylor L. Effects of relationship maintenance on psychological distress and dyadic adjustment among couples coping with lung cancer. Health Psychol. 2008;27(5):616–27. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, Georgia: 2008. [Google Scholar]