Summary

The transcription of genes that support memory processes are likely to be impacted by the normal aging process. Because Arc is necessary for memory consolidation and enduring synaptic plasticity, we examined Arc transcription within the aged hippocampus. Here, we report that Arc transcription is reduced within the aged hippocampus compared to the adult hippocampus during both “off line” periods of rest, and following spatial behavior. This reduction is observed within ensembles of CA1 “place cells”, which make less mRNA per cell, and in the dentate gyrus (DG) where fewer granule cells are activated by behavior. In addition, we present data suggesting that aberrant changes in methylation of the Arc gene may be responsible for age-related decreases in Arc transcription within CA1 and the DG. Given that Arc is necessary for normal memory function, these subregion-specific epigenetic and transcriptional changes may result in less efficient memory storage and retrieval during aging.

1. Introduction

Normal aging inevitably involves changes in memory function (Park and Reuter-Lorenz, 2009). While these changes occur with minimal gross brain pathology (Coleman and Flood, 1987; West, 1993), a number of subtle neural alterations do occur (Burke and Barnes, 2006). The formation and maintenance of memories relies on rapid and sustainable synaptic modification, and these processes require new gene expression. Several studies have reported age-associated changes in the expression of immediate-early genes (IEGs) within the hippocampus (Yau et al., 1996; Desjardins et al., 1997; Small et al., 2004), a brain region vulnerable to the aging process (Burke and Barnes, 2006). Among these genes, Arc (activity regulated cytoplasmic gene (Lyford et al., 1995), also known as Arg3.1 (Link et al., 1995) is necessary for memory consolidation (Guzowski et al., 2000; Plath et al., 2006), and is induced selectively in the principal cells of the hippocampus and other brain regions by neural activity specifically associated with active information processing (Miyashita et al., 2008). Thus, Arc has been used in the development of a method (catFISH; cellular compartment analysis of temporal activity by fluorescence in situ hybridization (Guzowski et al., 1999)) that allows precise identification of cells active in networks engaged by discrete behaviors. Although catFISH represents a powerful way to identify specific cells that comprise circuits supporting behavior, in isolation it does not provide a quantitative indication of the magnitude of gene transcription in the activated cells. Methods such as RT-PCR and gene microarrays, offer alternative approaches to determine whether the amount of a particular mRNA species changes with age (Blalock et al., 2003; Verbitsky et al., 2004; Rowe et al., 2007) but lack consideration for the identity of the cells that transcribe the mRNA of interest. Therefore, these approaches cannot address questions concerning the precise composition of behaviorally relevant circuits. Using catFISH, the initial development of a neural ensemble engaged as a result of brief exploratory activity was assessed, as well as the short-term stability of these ensembles within the dorsal hippocampus. Using RT-PCR within the same brain, the relative amount of Arc mRNA transcribed could also be determined. The combination of these methods revealed region-specific, age-related alterations in Arc transcription under both resting conditions, and following exploratory behavior.

To understand the mechanisms that may be responsible for attenuated Arc transcription, we measured DNA methylation of the Arc gene. DNA methylation involves the addition of methyl groups across CG-rich gene regulatory regions or at specific CG sites within those regions. These CpG sites or “islands” are generally found near or within the promoter region of mammalian genes, with about 40% of genes containing a CpG island. DNA methylation has been extensively studied in development, and until very recently, was thought to be a static process (Kangaspeska et al., 2008; Metivier et al., 2008; Ma et al., 2009). Recent work, however, suggests that DNA methylation remains an active process in the mature CNS, and can be rapidly and dynamically regulated by learning and memory processes. Further, interfering with this process can disrupt long-term memory consolidation (Miller and Sweatt, 2007; Lubin et al., 2008). Here, using bisulfite sequencing of the Arc gene, we demonstrate significant subregion-specific age-associated changes in the regulation of Arc DNA methylation.

2. Methods

2.1 Behavioral procedures

Experiments were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of animals and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arizona. Adult (9–12 months, n =29) and aged (24–32 months, n = 29) male Fischer-344 rats (National Institute on Aging at Harlan-Sprague Dawley) were used in these experiments. Prior to the beginning of experiments, the spatial and visual discrimination abilities of each rat were assessed using the Morris swim task as described in detail by Barnes et al. (1997). Performance on the the Morris swim task was analyzed using the corrected integrated path length (CIPL; Gallagher et al., 1993).

Experiments took place at least 2 hours after the house lights in the colony room were shut off. Animals were divided into 3 groups: (1) caged control (CC) animals that were sacrificed directly from their home cages; (2) rats that explored the environment once for 5 min, and were sacrificed immediately (A-5′); (3) animals that explored the same environment twice, with an intervening rest period of 20 min (A/A). Animals used for DNA methylation analysis explored the environment for 5 min, then returned to their home cages for 25 min prior to tissue collection. The procedure for exploration is described elsewhere (Guzowski et al., 1999). To ensure that the amount of exploratory activity between age groups could not explain differences in Arc transcription we verified that adult and aged rats showed similar exploratory behavior (see Figure S4).

2.2 Tissue harvesting and fluorescence in situ hybridization

After decapitation, brains were removed and hemisected, and half of the brain (used for in situ hybridization) was quick-frozen in isopentane. The remaining half (used for RT-PCR or DNA methylation analysis) was dissected into the CA region and the DG. These samples were flash frozen and stored at −70°C. Hemisections containing the dorsal hippocampus from 8 rats were molded in a block with Tissue-Tek OCT compound, so that all experimental conditions were represented in each block for each time point. Use of tissue blocks helps control for slide-to-slide variation in signal detection. Brains were sectioned at 20 μm coronally through the dorsal hippocampus (−3.2 to −3.8 mm from bregma; Paxinos and Watson, 1998), thaw-mounted on slides, and stored at −70°C. Fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed as described in detail elsewhere (Guzowski et al., 1999; Vazdarjanova and Guzowski, 2004).

2.3 Image acquisition and analysis

Images were collected using a Zeiss 510 Metaseries laser scanning confocal microscope. Photomultiplier tube assignment, pinhole size and contrast values were held constant for each brain region on a slide. The areas of analysis were z-sectioned in 1.0 μm optical sections. Similar methods were used to acquire images of the DG, except that the whole structure was imaged. Image analysis was conducted as described earlier (Guzowski et al., 1999; Vazdarjanova et al., 2002) using MetaMorph imaging software (Universal Imaging). Arc is not present in hippocampal glia or interneurons under these experimental conditions (Vazdarjanova et al., 2006). Only whole neuron-like cells found in the middle 20% of each stack were included in the analyses. Neurons were classified as: 1) foci+ which had one or two intense intranuclear foci present in at least three planes; 2) cytoplasmic+ which had perinuclear or cytoplasmic staining surrounding at least 60% of the cell and visible in at least three plains; 3) double+ which fulfilled both criteria 1 and 2, or 4) negative which did not have any detectable staining. An assessment of intranuclear foci fluorescent intensity in CA1 was conducted on tissue from rats that explored the environment for one 5 min session using a method similar to that described by Guzowski et al. (2006) and Miyashita et al. (2009). Image analysis was performed by an experimenter blind to the experimental conditions.

2.4 Real-time RT-PCR

Samples used for RT-PCR were prepared using the RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was DNase-treated and reverse-transcribed using SuperScript II (Invitrogen). A negative control was included in which no reverse transcriptase was added. Primers for Arc and for glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GapDH), were designed using Primer 3 software (www.genome.wi.mit.edu) based on the rat sequences deposited in GenBank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. GapDH was used to normalize data because its expression does not change with age or with various treatments (Tanic et al., 2007). The primer sequence for GapDH was as follows: forward, AATGGGAGTTGCTGTTGAAG; reverse, CTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTA. The primer sequence for Arc was as follows: forward, CTCCAGGGTCTCCCTAGTCC; reverse, TGAGACCAGTTCCACTGCTG. PCR amplification of cDNA was performed using the BioRad iCycler Real-Time Detection System (BioRad Laboratories). cDNA was added to a 1X reaction master mix (iQ SYBR Green Supermix, BioRad) along with the gene specific primers (0.5μM each of forward and reverse primer) and nuclease free H2O. For each experimental sample, duplicate reactions were conducted in 96-well plates, and these assays were run twice. Real-time PCR assays were tested to determine and compare the efficiencies of the target and control gene amplifications in order to ensure high (90–100%) and similar efficiency. A melt curve analysis was also conducted to determine the uniformity of product formation, primer-dimer formation, and amplification of non-specific products. The presence of specific amplification products was confirmed by a single peak on the melt curve and plotted as the negative derivative of fluorescence as a function of temperature (-d(RFU)/dT).

2.5 Bisulfite sequencing PCR

DNA was isolated and purified from hippocampal tissue, then subjected to bisulfite modification (Qiagen). Bisulfite-treated samples were amplified using primers that targeted either a CpG-rich region within the Arc promoter (Forward: GGTTAATGGGAGTTAGGGTTT; Reverse: TCATATAATCCAACTCCATCTACTC) or a CpG-rich region within the coding portion of the Arc gene (Forward: TGTGATTTTGTAGATTGGTAAGTGT; Reverse: CAAACCTTAATAAACTTCTTCCAAC). Following purification with a gel extraction kit (Qiagen), the PCR products were sequenced using the reverse primer at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Genomics Core Facility of the Heflin Center for Human Genetics. The percent methylation of each CpG site within the region amplified was determined by the ratio between peaks values of G and A (G/[G+A]), and these levels on the electropherogram were determined using Chromas software. Universally unmethylated and methylated standards (0–100% methylation; EpigenDx) were used as controls in these experiments. To confirm that direct sequencing is adequately sensitive to detect methylation, even when levels are very low, universally unmethylated and methylated standards from 6–10/standards, across multiple bisulfite treatments and gene targets including the 2 Arc regions examined in this manuscript were assessed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of results from standardized control samples

| Expected | Actual (mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|

| Standard, 0% methylation* | 2.51% ± 0.42 |

| Standard, 5% methylation** | 5.46% ± 0.85 |

| Standard, 10% methylation | 9.90% ± .0.94 |

| Standard, 75% methylation | 74.39% ± 1.71 |

| Standard, 100% methylation | 92.10% ± 0.16 |

t=−3.415, df=15, p=0.0038

t=−3.317, df=15, p=0.0047

2.6 Data analysis

Relative gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). To determine differences in the relative levels of Arc mRNA between adult and aged rats at baseline and following the behavioral treatment, the ΔCT was determined for each sample (CT Arc − CT GapDH) with the adult samples used as the calibrator samples in place of the caged control samples. Unpaired t-tests were used to assess mRNA levels measured by RT-PCR, and group differences for the cell count data were analyzed with analysis of variance tests (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests. The BSP data were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests. For all tests, the null hypotheses were rejected at the 0.05 level of significance.

3. Results

3.1 Aged rats show impaired spatial memory on the Morris swim task

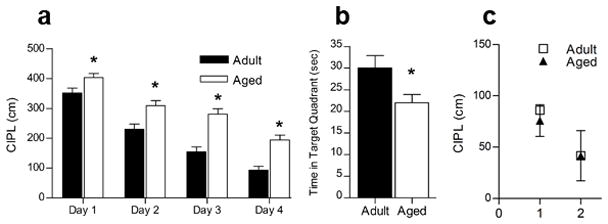

As shown in Figure 1, the behavioral data are consistent with previous comparisons of adult and aged rats on the Morris swim task (Gage et al., 1984; Gallagher et al., 1993). There was a significant effect of age on the corrected integrated path length (CIPL) over the 4-day training period; the aged rats take longer path lengths to the platform than adult rats (p < 0.0001). Post-hoc analysis showed that this effect appeared on day one of training and persisted through the 4th day of training (day 1: p = 0.018; day 2: p = 0.001; day 3: p < 0.0001; day 4: p < 0.0001). Overall, adult rats showed significant improvement across days, whereas old rats showed less robust learning (Figure 1A). This was further confirmed on the probe trial (Figure 1B), in which adult rats spent significantly more time in the target quadrant of the pool than did the old rats (p = 0.035). On visible trials (Figure 1C), there was no effect of age on the CIPL on day 1 (p = 0.755) or day 2 (p = 0.989) of testing. Both age groups showed significant learning across days, taking a shorter path to the platform on day 2 of the visible trials compared to day 1 (Figure 1C; aged, p = 0.001; adult, p = 0.029).

Figure 1.

Aged rats show impaired acquisition of the spatial version of the Morris swim task. A. Aged rats (n = 24) take a significantly longer path length (CIPL) to reach the platform than do adult rats (n = 24), and this difference was significant on all 4 days of training (*p < 0.0001). B. On the probe trial, aged rats spent significantly less time in the target quadrant than did adult rats (*p = 0.035). C. On the cued version of the task, in which the escape platform was visible, both adult and aged rats showed improvement in performance over 2 days of training. There was no significant effect of age on either day.

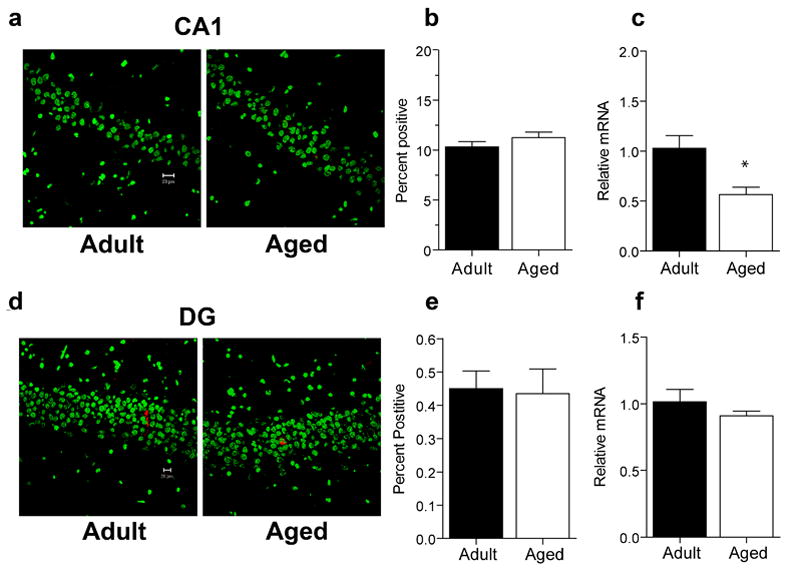

3.2 Resting levels of Arc mRNA in CA1

To assess potential age differences in the levels of Arc mRNA and the proportion of cells that transcribe Arc under resting conditions, a group of rats were sacrificed directly from their home cages. When FISH (see Figure 2A) was used, similar proportions of CA1 neurons transcribed Arc in both aged and adult groups (Figure 2B; p = 0.243). The proportion of cells that transcribe Arc is low; less than 12% of pyramidal cells were Arc+, values similar to previously published reports for adult rats (Guzowski et al., 1999; Vazdarjanova et al., 2002). RT-PCR data were then analyzed from the other hemisphere of the rats used for the FISH analysis. Aged rats had significantly lower resting levels of Arc in CA1 relative to adult rats (Figure 2C; p = 0.013). Together, these data indicate that Arc transcription in CA1, under resting conditions, is affected by age. Furthermore, this age effect is not due to changes in the proportion of neurons that transcribe Arc, but rather, to some or all aged CA1 cells transcribing less Arc.

Figure 2.

Caged control levels of Arc mRNA in area CA1 and the DG. A. Sample images of cells expressing Arc mRNA (red) in area CA1 of adult (n=6) and aged (n = 6) caged control animals. Nuclei are counterstained with Sytox Green. Calibration bar = 20 μm. B. Similar proportions of CA1 pyramidal neurons in aged and adult caged control animals showed Arc mRNA expression as determined by FISH. C. Caged control levels of Arc measured by RT-PCR are lower in aged rats compared to adult rats in area CA1 (*p = 0.013). D. Sample images of dentate granule neurons expressing Arc mRNA (red). Nuclei are counterstained with Sytox Green. Calibration bar = 20 μm. E. Aged and adult caged control rats have similar proportions of dentate granule neurons that transcribe Arc. F. Caged control levels of Arc mRNA measured by RT-PCR are similar in aged compared to adult rats in the DG.

3.3 Resting levels of Arc mRNA in the Dentate Gyrus

Examples of the pattern of Arc activation for caged control rats are shown in Figure 2D. Under resting conditions, similar proportions of aged and adult granule cells transcribe Arc (Figure 2E; p = 0.87). For both age groups, less than 0.5% of granule cells were Arc+. In contrast to area CA1, there was no significant effect of age on resting levels of Arc in the DG (Figure 2F; p = 0.313) as measured by RT-PCR. These data indicate that under resting conditions, Arc mRNA is expressed similarly in aged and adult granule cells.

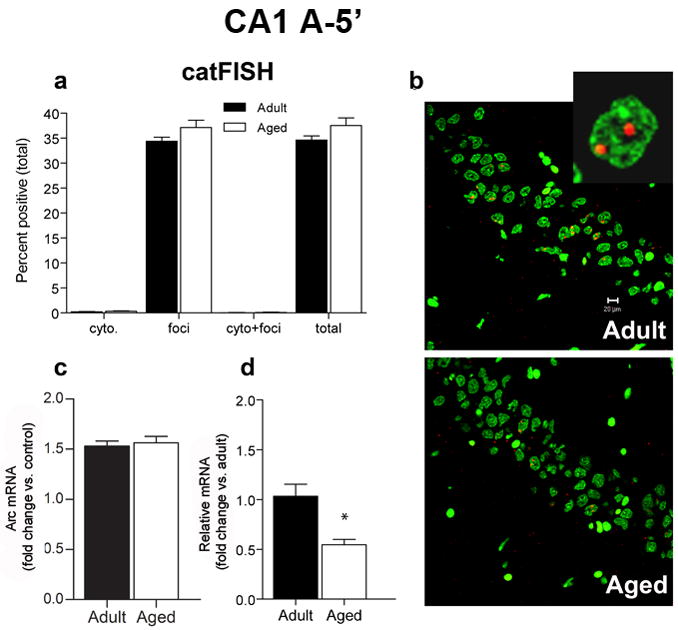

3.4 Exploration-induced Arc in CA1

When an animal enters a novel environment, new place fields form within minutes (Bostock et al., 1991; Wilson and McNaughton, 1993). To determine if aging affects this process, we measured the proportion of CA1 pyramidal neurons that expressed Arc mRNA following 5 min of exploration. A single 5 min episode of exploration results in an increase in the number of Arc+ neurons in CA1 in both adult and aged rats (Figure 3A); the total percentage of Arc+ neurons was 34% for adult rats and 38% for aged rats, values consistent with previous studies that examined behaviorally-induced Arc expression using a similar task (Small et al., 2004; Vazdarjanova and Guzowski, 2004). This difference was not statistically different (p = 0.114), indicating that both age groups recruit similar proportions of CA1 neurons following exploration. Using catFISH, we determined that nearly all of the Arc+ cells showed intranuclear transcriptional foci (Figure 3A and 3B), indicating that these cells began transcribing Arc within the 5 min period immediately prior to sacrifice, and thus, the initial transcriptional kinetics of Arc are similar between age groups. Additionally, we found no significant relationship between the proportion of Arc+ CA1 cells in individual adult and aged rats and behavioral performance on the spatial version of the Morris swim task (p = 0.158; Figure S1A).

Figure 3.

CatFISH and RT-PCR data for area CA1 after a single 5 min exposure to the environment (A-5′). A. After the 5 min exploration treatment, similar proportions of CA1 pyramidal neurons transcribe Arc for both aged (n = 6) and adult (n = 6) rats (total). The percentage of cells with Arc in the cytoplasm (cyto) or nucleus (foci) only or that were double-labeled (cyto + foci) was also similar between age groups. CatFISH analysis of the pattern of Arc labeling revealed that following exploration, most Arc+ cells are foci-labeled, indicating that transcription of Arc began ~5 min prior to sacrifice. B. Sample images of cells expressing Arc mRNA (red) in area CA1 from adult and aged rats that were sacrificed 5 min after exploration. Nuclei are counterstained with Sytox Green. Calibration bar = 20 μm. Inset is an example of a CA1 neuron with nuclear label. C. After exploring an environment for 5 min, the fold increase in Arc mRNA compared to caged control levels measured by RT-PCR is similar for both aged and adult rats. D. Relative levels of Arc (with adult levels used as the calibration sample) are lower in aged rats compared to adult rats (*p < 0.0001).

Adult and aged rats showed a similar fold increase in Arc above resting levels (Figure 3C; p = 0.69) as measured by RT-PCR, although the relative levels of Arc were lower for the aged rats compared to the adult rats (Figure 3D; p < 0.0001). This may be partly due to reduced resting levels of Arc (Figure 2) in some or all of the pyramidal cells that transcribe Arc.

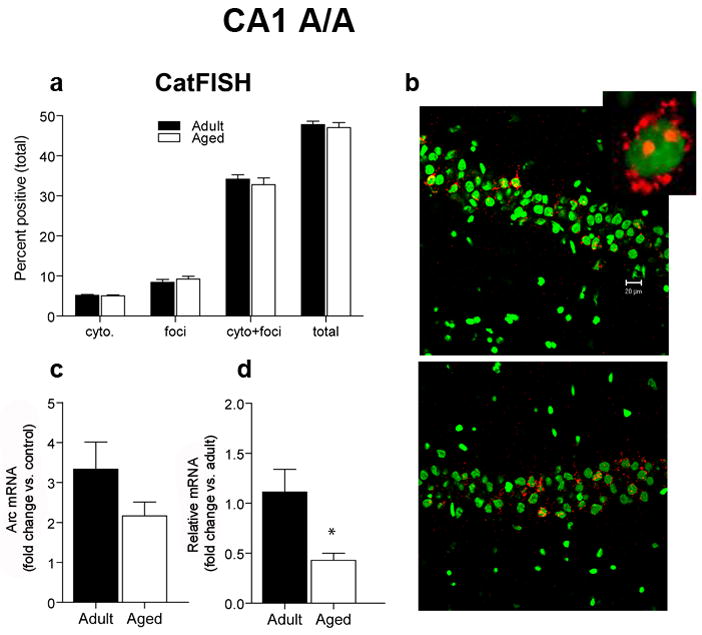

For the two-exposure exploration treatment, the total proportion of Arc+ pyramidal neurons after the A/A treatment was similar for aged (47%) and adult rats (48%; Figure 4A). Using catFISH analysis, we determined that the majority of Arc+ neurons had both intranuclear foci and cytoplasmic staining, indicating that most Arc+ neurons transcribed Arc on both exposures to the environment in both age groups (Figure 4A and 4B). RT-PCR indicated that both adult and aged rats showed a robust fold increase of Arc in CA1 that is not statistically different between groups (Figure 4C; p = 0.32). Possibly because resting levels of Arc were lower in the aged rats, the relative levels of Arc transcription were significantly lower compared to adult rats (Figure 4D; p = 0.624). Together, these results suggest that for the aged rats, the same number of pyramidal neurons transcribe Arc, but some or all of them transcribe less. Additionally, we found no significant relationship between the proportion of Arc+ CA1 pyramidal cells in individual adult and aged rats and behavioral performance on the Morris swim task (p = 0.947; Figure S1B).

Figure 4.

CatFISH and RT-PCR data for area CA1 after two 5 min exposures to the environment, separated by a 20 min rest (A/A). A. The proportion of CA1 pyramidal neurons that transcribe Arc after the A/A treatment is similar for aged (n = 6) and adult (n = 6) rats (total). The percentage of cells with Arc in the cytoplasm (cyto) or nucleus (foci) only or that were double-labeled (cyto + foci, see inset) was also similar between age groups. CatFISH analysis of the pattern of Arc labeling indicates that after the A/A treatment, most Arc+ cells have both cytoplasmic and nuclear Arc labeling, indicating that most of the Arc+ pyramidal neurons were activated by both the first and second behavioral epochs. B. Sample images of cells expressing Arc mRNA (red) in area CA1 of adult and aged rats that were sacrificed after the A/A treatment. Nuclei are counterstained with Sytox Green. Calibration bar = 20 μm. Inset is an example of a CA1 neuron with both a cytoplasmic and nuclear label. C. After the A/A treatment, the fold increase in Arc mRNA from caged control levels is similar for aged compared to adult rats as measured by RT-PCR. D. Because of the lower resting levels of Arc in the older animals, however, the relative amount of Arc mRNA is significantly reduced in aged compared to adult rats (with adult levels used as the calibration sample; *p < 0.0001).

3.5 Exploration-induced Arc in the aged Dentate Gyrus

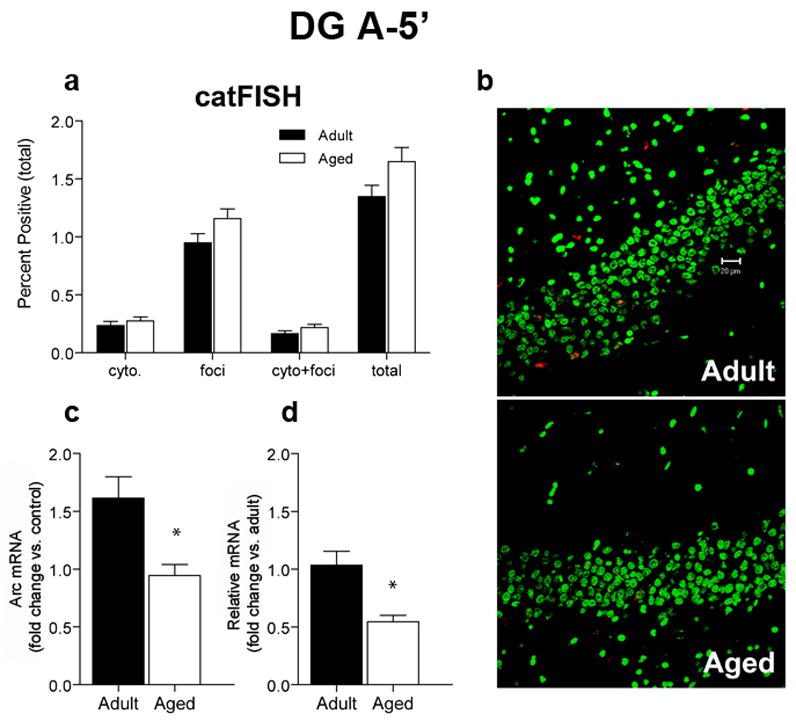

Within the DG (Figure 5) a single episode of exploration activated transcription of Arc in 1.3% of adult granule cells and 1.6% of aged granule cells (Figure 5A). This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.071) indicating that the majority of Arc+ neurons had the expected nuclear labeling in both age groups (Figure 5A and 5B). RT-PCR revealed that aged rats had a significantly reduced fold increase in Arc compared with adult rats following a single episode of exploration (Figure 5C, p = 0.001). This age-related reduction in fold increase resulted in less Arc in the DG for aged relative to adult rats (Figure 5D; p = 0.004). There was no significant relationship between the proportions of Arc+ granule cells and performance on the spatial version of the Morris swim task (p > 0.05; Figure S1C). Although the regression was positive, the numbers of animals in each age group were likely to have been insufficient to reveal small effect sizes.

Figure 5.

CatFISH and RT-PCR data for the DG after a single 5 min exposure to the environment. A. Similar proportions of aged (n = 6) and adult (n = 6) granule cells transcribe Arc after a single 5 min exploration treatment (total). The percentage of cells with Arc in the cytoplasm (cyto) or nucleus (foci) only or that were double-labeled (cyto + foci) was also similar between age groups. CatFISH analysis of the pattern of Arc labeling indicates that after the A-5′ treatment, most Arc+ cells have nuclear (foci) Arc labeling, indicating that most of the Arc+ granule neurons were activated during the preceding 5 min exploration period. B. Sample images of cells expressing Arc mRNA (red) after 5 min of exploration. Nuclei are counterstained with Sytox Green. Calibration bar = 20 μm. C. After exploring an environment for 5 min (A-5′), the fold increase in Arc mRNA from caged control levels is significantly reduced in aged rats compared to adult rats (*p < 0.001). D. The relative amount of Arc, as measured by RT-PCR is also lower in aged compared to adult rats (with adult levels used as the calibration sample; *p < 0.004).

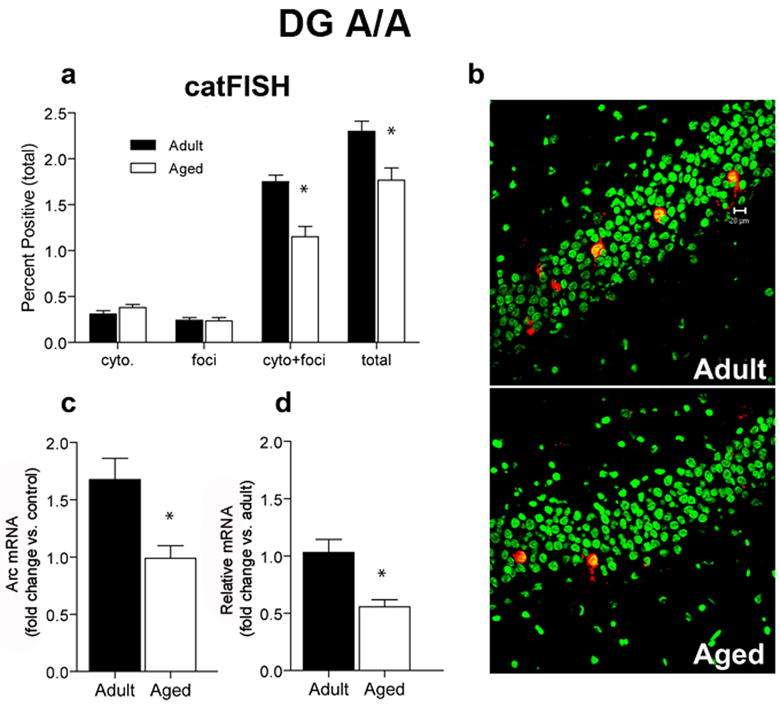

For the A/A treatment, adult rats had a greater proportion of Arc+ granule cells (2.3%) than did aged rats (1.75%; p = 0.006; Figure 6A and 6B). Using catFISH, we determined that the majority of Arc+ neurons had both nuclear and cytoplasmic labeling, indicating that these neurons were active on both exposures to the environment (Figure 6A). RT-PCR revealed that aged rats showed a smaller fold increase in Arc in the DG compared to adult rats (Figure 6C; p = 0.01), and furthermore, had significantly lower levels of Arc when compared to the adult rats (Figure 6D; p = 0.004). There was no significant relationship between the proportions of Arc+ granule cells and performance on the Morris swim task (p = 0.0938; Figure S1D). As noted above, although the regression was positive, the numbers of animals may have been insufficient to reveal small effect sizes.

Figure 6.

CatFISH and RT-PCR data for the DG after two exposures to the environment, separated by a 20 min rest (A/A). A. A smaller proportion of aged (n = 6) dentate granule neurons transcribe Arc compared to adult rats (n = 6; *p = 0.006). CatFISH analysis revealed that the percentage of cells with Arc in the cytoplasm (cyto) or nucleus (foci) were not different between adult and aged rats, but the percentage of Arc+ neurons that were double-labeled (cyto + foci) was significantly reduced in aged rats. Overall, the majority of Arc+ neurons were activated during both the first and second behavioral epochs in both age groups. B. Sample images of cells expressing Arc mRNA (red) after the A/A treatment. Nuclei are counterstained with Sytox Green. Calibration bar = 20 μm. C. After the A/A treatment, the fold increase in Arc mRNA from caged control levels is significantly lower for aged compared to adult rats (*p < 0.01). D. The relative amount of Arc as measured by RT-PCR is significantly lower in aged compared to adult rats (with adult levels used as the calibration sample; *p < 0.004).

3.6 The amount of primary transcript detected per Arc+ CA1 neuron is reduced in aged rats

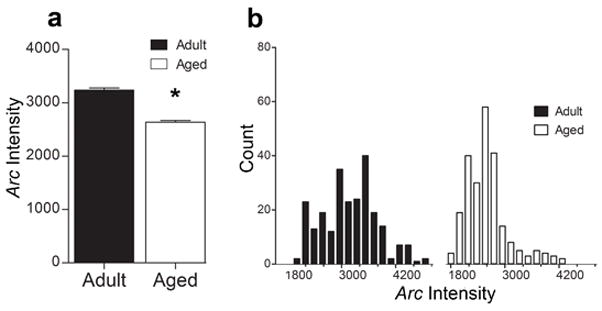

Within ~2 min of stimulation, Arc can be detected at the genomic site of transcription using FISH (Guzowski et al., 1999), and is detectable up to 15 min following the initiation of transcription (Vazdarjanova et al., 2002). We have reported that the number of neurons that transcribe Arc are similar between adult and aged rats in CA1, but using RT-PCR, we have shown that aged rats have less Arc mRNA relative to adult rats. Because the same number of cells transcribe Arc following behavior in CA1, this reduction measured by RT-PCR, may be the result of some or all aged pyramidal neurons transcribing less Arc. We measured the mean integrated fluorescent intensity of Arc intranuclear foci as an indicator of the amount of primary transcript detected per Arc+ CA1 neuron is different between age groups after 5 min of spatial exploration. The results of this analysis (Figure 7A) indicate that the mean integrated fluorescent intensity from aged rats is significantly lower than for adult rats (p < 0.0001), consistent with the idea that there is an age-related decrement of primary transcript. This reduction appears to affect the population of Arc-transcribing pyramidal cells as a whole, as the distribution of the intensities of Arc intranuclear foci was unimodal and shifted leftward in aged compared to the younger rats (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Mean integrated intensity of CA1 intranuclear foci after 5 min of spatial exploration treatment. A. The mean integrated intensity of intranuclear foci is significantly lower in aged rats compared to adult rats (*p < 0.0001). B. Frequency distribution histogram of the average intensity of Arc transcriptional foci for adult and aged rats. Note the leftward shift to the lower intensity values in the aged rats.

3.7 Age-associated changes in DNA methylation may modulate aberrant Arc transcription

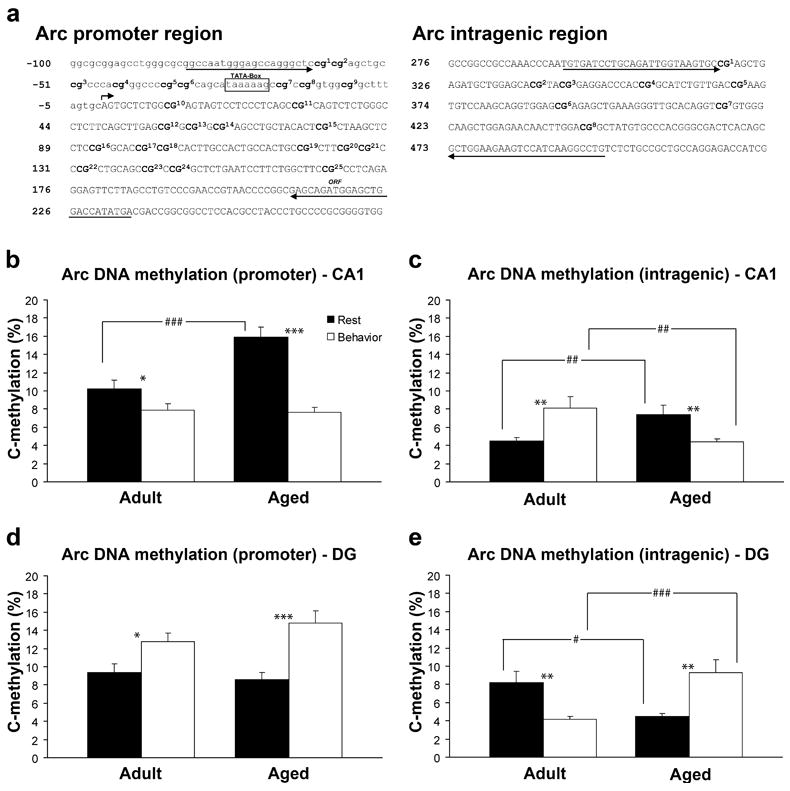

DNA methylation plays a key role in dynamically regulating gene transcription in the adult CNS (Graff and Mansuy, 2008; Roth and Sweatt, 2009), including several genes necessary for normal memory function (Miller and Sweatt, 2007; Lubin et al., 2008). To investigate whether DNA methylation contributes to the altered Arc transcription observed within the aged hippocampus, direct bisulfite sequencing PCR was used to examine changes at 2 loci of the Arc gene. Although Arc has multiple regulatory elements (Kawashima et al., 2009), we focused on two CpG islands (see Figure 8A), one that spans the promoter region, and a second island downstream from the promoter region (intragenic region). These CpG islands were sequenced for both CA1 and the DG.

Figure 8.

Methylation analysis of Arc CpG dinucleotides from the hippocampus of adult (n = 6) and aged (n = 6) animals. A. Schematic of examined CpG sites relative to the transcription initiation site (bent arrow) of the Arc gene. Sequencing primer pair positions are indicated by the left and right arrows. B–C. In area CA1 aged rats show significantly more methylation of Arc DNA at the promoter region (###p <0.0001) and the intragenic region (##p<0.01) under resting conditions. Following spatial behavior, both adult (*p < 0.05) and aged (***p<0.001) rats show a significant reduction in methylation at the promoter region compared to resting levels. At the intragenic region adult rats show a significant increase in methylation (**p<0.01), while aged rats show a significant decrease following spatial behavior (**p<0.01). There is also a significant difference in the intragenic region between age groups following spatial behavior (##p<0.01). D–E. In the DG adult and aged rats show similar methylation within the Arc promoter, but at the intragenic region, aged rats have less methylation than adult rats (#p<0.05). Following spatial behavior, both adult (*p<0.05) and aged rats (***p<0.001) show a significant increase in methylation at the promoter. At the intragenic region adult rats show a significant decrease in methylation (**p<0.01) after behavior, while aged rats show an increase (**p<0.01). There is also a significant difference between age groups following behavior at the intragenic region (###p<0.001).

In CA1, under resting conditions, aged rats show significantly greater methylation of Arc promoter (p < 0.0001; Figure 8B) and intragenic DNA (p = 0.01.; Figure 8C) than do adult rats. In the DG, both age groups show equivalent methylation within the promoter region (Figure 8D), but at the intragenic region of the Arc gene, aged rats show significantly less methylation (p = 0.0121; Figure 8E) compared to adult rats under resting conditions. The percent methylation at each CpG site for CA1 is shown in Figure S2A and C, and for the DG in Figure S3A and C.

To measure dynamic changes in methylation of Arc, we examined methylation 25 min after a single 5 min session of exploration. Within CA1 (Figure 8B), methylation of Arc is significantly reduced compared to resting levels at the promoter region for both adult (p = 0.0418) and aged rats (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference, however, between age groups after behavior (p = 0.793; Figure 8B). Within the intragenic region of the Arc gene, methylation is significantly increased in the adult brain (p = 0.0055; Figure 8C), whereas methylation is significantly reduced in aged rats following exploration (p = 0.0071; Figure 8C). In addition, there is a significant difference between age groups within the intragenic region following behavior, with adult rats showing significantly more methylation compared to aged rats (p = 0.0041; Figure 8C). The percent methylation at each CpG site for CA1 is shown in Figure S2B and D. For the DG, both adult (p = 0.0111) and aged rats (p = 0.0001) show significant increases in methylation at the promoter region (Figure 8D) compared to resting levels of methylation. At the intragenic region, however, adult rats show a significant reduction in methylation (p = 0.0034; Figure 8E), whereas the aged rats show an increase (p = 0.0032; Figure 8E) following exploration. Additionally, there is a significant difference between age groups at the intragenic but not the promoter region following exploration. The percent methylation at each CpG site for the DG is shown in Figure S3B and D. Together, these results demonstrate that methylation of the Arc gene can be dynamically regulated by spatial behavior, occurs in a subregion specific manner, and changes as a function of age.

4. Discussion

The network composition and transcriptional participation of individual cells activated by discrete behavioral experiences were examined using a combination of catFISH and RT-PCR methods. The present findings provide several insights into the Arc transcriptional response under conditions of “rest” and exploratory behavior. Resting and behavioral activation of Arc responses are altered with aging in both hippocampal pyramidal and granule cells; however, the changes observed are distinct in these cell types. The selective differences in transcriptional responses of aged hippocampal cells occur in network activation, resting levels of Arc per cell, and in levels of Arc transcribed in response to spatial behavior. Furthermore, these age-associated changes in Arc transcription within networks of hippocampal neurons may be influenced by age-related alterations in the DNA methylation status of the Arc gene.

4.1 ‘Resting’ levels of Arc

Arc is transcribed at low levels when an animal is resting. Recent work has shown that IEG transcription under these conditions reflects active information processing and is not simply noise (Marrone et al., 2008). When an animal engages in spatial behavior prior to a rest period, IEG activation during the rest period occurs in cells that transcribed IEGs in response to the previous spatial behavior. This finding complements work suggesting that the consolidation of memory occurs when the hippocampus is not actively processing external information (Marshall and Born, 2007). In the present study, Arc levels in the resting state are lower in aged CA1, but not in the aged DG when measured by RT-PCR. In neither case, was there an age difference under resting conditions in the proportion of pyramidal or granule cell that transcribe Arc. For CA1 cells, this suggests that some or all of the neurons that express Arc during rest may transcribe less per cell. Thus, even though aged rats are capable of a robust Arc response following behavior, this response is not sufficient to overcome these low resting levels of Arc. The reduced resting levels of Arc in pyramidal cells suggests that plasticity mechanisms important for memory consolidation during rest may be defective in aged animals, possibly resulting in inferior memory stabilization.

4.2 Behaviorally-induced Arc activity

In the current study, neural ensembles were activated by either a single spatial experience or by two separate experiences with an intervening rest period. For CA1 pyramidal cells, similar proportions of aged and adult cells expressed Arc mRNA following either one or two epochs. Moreover, the majority of pyramidal neurons activated by the first epoch were then reactivated by the second epoch in both age groups. Under these conditions, CA1 neurons are capable of activating and reactivating a similar sized ensemble. Although this finding appears to stand in contrast to the observation that old CA1 pyramidal cells show probabilistic place field remapping (Barnes et al., 1997; Wilson et al., 2004), there are a number of possible explanations. First, rats were exposed twice to an environment with a short interval in the present experiment, rather than multiple times, with longer intervening intervals. The temporal window and re-exposure may have made it less likely that global remapping would occur. Second, the assisted exploration procedure used here may provide a salient anchor for this episode of experience compared to the free foraging condition used during electrophysiological recordings. In combination, these factors may have contributed to the reliable map retrieval observed in aged rats of the present study.

Despite reliable map retrieval within CA1, RT-PCR reveals that in response to exploration, aged rats show lower Arc levels than do adult rats. Because the same proportions of neurons are activated by exploration, some or all of the Arc-transcribing CA1 neurons in aged rats make less mRNA. Additional analyses revealed an age-associated decrease in the mean integrated fluorescent intensity of transcriptional foci in individual pyramidal cells of aged rats. Interestingly, this age-related reduction in the Arc response in CA1 cells is consistent with the finding that aged rats show blunted place field expansion, and thus fire fewer spikes than do adult rats under identical behavioral conditions (Shen et al., 1997; Burke et al., 2008). As of yet, no experiments have equated numbers of spikes between young and old rats under the behavioral conditions used here (i.e., assisted exploration). A single pass through a place field, however, can induce Arc (Miyashita et al., 2009), although cell counts and simultaneous PCR measurements of the amount of Arc expressed with single or multiple passes through a field have not been examined in isolated hippocampal subregions.

In the DG, a single episode of spatial behavior engages similar proportions of granule neurons in adult and aged rats. If the rat has been exposed to the environment twice with a 20 min intervening rest period, however, a smaller proportion of aged granule cells transcribe Arc. Measurements of the amount of Arc by RT-PCR indicate higher levels in the adult DG in both conditions. The purported role of the DG in cognition is to orthogonalize incoming information such that similar inputs are rendered more discriminable (Leutgeb et al., 2007). Although there is no loss of layer II entorhinal cortical projection cells to the DG, there is clear axon collateral pruning (Barnes and McNaughton, 1979, 1980) and fewer synaptic contacts from this region onto granule cells in memory-impaired rats (Geinisman et al., 1992). One possible outcome of this reduced input in aged rats is lower levels of Arc in the DG with the prediction that older rats should be less able to distinguish between similar inputs. Although not explicitly tested here, lesion work indicates that rats without a functional DG do not detect relatively small environmental changes (Hunsaker et al., 2008).

4.3 Epigenetic regulation of Arc transcription

DNA methylation and demethylation actively participate in regulating synaptic plasticity and learning and memory processes via regulation of gene transcription (Roth and Sweatt, 2009). The present study reports several novel observations for DNA methylation of the Arc gene. First, methylation of Arc DNA is dynamically regulated by spatial behavior within CA1 and the DG. This finding extends recent work demonstrating that DNA methylation of the genes PP1, reelin, and BDNF are dynamically regulated by contextual fear conditioning (Miller and Sweatt, 2007; Lubin et al., 2008). Second, a significant effect of age on the methylation status of the Arc gene, within CA1 and the DG was found. In CA1, aged rats show significantly more methylation under resting conditions compared to adult rats at the Arc promoter and an intragenic site. These data are consistent with the observations of reduced mRNA levels in old CA1 neurons compared to young neurons.

Following spatial behavior, both age groups show a significant change in DNA methylation at both the promoter and intragenic region of the Arc gene. These data are consistent with the likelihood that reduced methylation within the promoter region can create a more permissive environment for Arc transcription in response to behavior. Within the intragenic region of the Arc gene, adult rats show a significant increase in methylation, while aged rats show a significant decrease. This is unexpected in light of the relative decrease in Arc mRNA following behavior within CA1 of aged rats, and because of the general view that DNA methylation is thought primarily to result in transcriptional silencing. Recent work indicates that DNA methylation, under some conditions, participates in transcriptional activation (Chahrour et al., 2008), suggesting that the observed increase in methylation within the intragenic region of the Arc gene in adult rats, but not aged rats, may be indicative of active transcription. Thus, optimal transcription of Arc may require two events in CA1 cells, demethylation at the promoter and methylation at the intragenic region of the gene.

Within the DG, significant changes in methylation of the Arc gene were also observed. Under resting conditions, both age groups show equivalent levels of DNA methylation within the promoter region, but adult rats show significantly greater levels of methylation within the intragenic region of the Arc gene. Following spatial behavior, both age groups show a significant increase in methylation within the Arc promoter region. Within the intragenic region, adult rats show a significant decrease in methylation, whereas aged rats show a significant increase. Because principle cells within the dentate gyrus are biologically distinct from principle cells within CA1 and moreover, participate in different aspects of information processing, it is not surprising that changes in methylation of the Arc gene are different here compared to CA1. In addition, although the changes observed in methylation of the Arc gene are small, even these small changes may have significant changes on information processing within these distinct brain regions. For example, changes in the methylation of the Arc gene within a small percentage of neurons within in a network that supports spatial information processing may serve to stabilize or destabilize the network via effects on Arc transcription. Together, our data indicate that there are age-associated changes in Arc DNA methylation and transcription, which likely contribute to the age-related impairment in spatial memory.

Dysregulated DNA methylation is thought to contribute to mental retardation syndromes, Alzheimer’s disease, and adult onset neuropsychiatric disorders (Graff and Mansuy, 2008). Recent work also demonstrates significant increases and decreases in DNA methylation within the human brain during both normal and pathological aging that corresponds to a concomitant change in mRNA levels (Siegmund et al., 2007). Although the mechanisms that control these processes are not fully understood, it is becoming increasingly clear that dynamic methylation and demethylation are involved in regulating learning and memory (Miller and Sweatt, 2007; Lubin et al., 2008). Because it is well documented that the transcription and expression of genes necessary for optimal learning and memory function are affected by the normal aging process (Yau et al., 1996; Desjardins et al., 1997; Blalock et al., 2003; Small et al., 2004; Verbitsky et al., 2004; Rowe et al., 2007), it is critical to better understand the mechanisms that control gene activation and how advancing age affects these processes. Such insights may not only lead to more effective preventative strategies to improve quality of life, but will also contribute to a better general understanding of memory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathy Olsen, Sara Burke, Saman Nematollahi, Bo Xiao, Anthony Lanahan and Heather Milliken for technical assistance, and Michelle Carroll and Luann Snyder for administrative support. This research was supported by NIA AG009219, AG031722, MH57014, and NS057098, the state of Arizona and ADHS, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Neurophysiological comparison of dendritic cable properties in adolescent, middle-aged, and senescent rats. Exp Aging Res. 1979;5:195–206. doi: 10.1080/03610737908257198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Physiological compensation for loss of afferent synapses in rat hippocampal granule cells during senescence. J Physiol. 1980;309:473–485. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, Suster MS, Shen J, McNaughton BL. Multistability of cognitive maps in the hippocampus of old rats. Nature. 1997;388:272–275. doi: 10.1038/40859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock EM, Chen KC, Sharrow K, Herman JP, Porter NM, Foster TC, Landfield PW. Gene microarrays in hippocampal aging: statistical profiling identifies novel processes correlated with cognitive impairment. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3807–3819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03807.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock E, Muller RU, Kubie JL. Experience-dependent modifications of hippocampal place cell firing. Hippocampus. 1991;1:193–205. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450010207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Barnes CA. Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:30–40. doi: 10.1038/nrn1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Maurer AP, Yang Z, Navratilova Z, Barnes CA. Glutamate receptor-mediated restoration of experience-dependent place field expansion plasticity in aged rats. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:535–548. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong ST, Qin J, Zoghbi HY. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science. 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PD, Flood DG. Neuron numbers and dendritic extent in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1987;8:521–545. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(87)90127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins S, Mayo W, Vallee M, Hancock D, Le Moal M, Simon H, Abrous DN. Effect of aging on the basal expression of c-Fos, c-Jun, and Egr-1 proteins in the hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(96)00206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH, Dunnett SB, Bjorklund A. Spatial learning and motor deficits in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 1984;5:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(84)90084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher M, Burwell R, Burchinal M. Severity of spatial learning impairment in aging: development of a learning index for performance in the Morris water maze. Behav Neurosci. 1993;107:618–626. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.4.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geinisman Y, deToledo-Morrell L, Morrell F, Persina IS, Rossi M. Structural synaptic plasticity associated with the induction of long-term potentiation is preserved in the dentate gyrus of aged rats. Hippocampus. 1992;2:445–456. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450020412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff J, Mansuy IM. Epigenetic codes in cognition and behaviour. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192:70–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Worley PF. Environment-specific expression of the immediate-early gene Arc in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1120–1124. doi: 10.1038/16046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Lyford GL, Stevenson GD, Houston FP, McGaugh JL, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Inhibition of activity-dependent arc protein expression in the rat hippocampus impairs the maintenance of long-term potentiation and the consolidation of long-term memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3993–4001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-03993.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsaker MR, Rosenberg JS, Kesner RP. The role of the dentate gyrus, CA3a,b, and CA3c for detecting spatial and environmental novelty. Hippocampus. 2008;18:1064–1073. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangaspeska S, Stride B, Metivier R, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Ibberson D, Carmouche RP, Benes V, Gannon F, Reid G. Transient cyclical methylation of promoter DNA. Nature. 2008;452:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature06640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima T, Okuno H, Nonaka M, Adachi-Morishima A, Kyo N, Okamura M, Takemoto-Kimura S, Worley PF, Bito H. Synaptic activity-responsive element in the Arc/Arg3.1 promoter essential for synapse-to-nucleus signaling in activated neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:316–321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806518106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb JK, Leutgeb S, Moser MB, Moser EI. Pattern separation in the dentate gyrus and CA3 of the hippocampus. Science. 2007;315:961–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1135801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link W, Konietzko U, Kauselmann G, Krug M, Schwanke B, Frey U, Kuhl D. Somatodendritic expression of an immediate early gene is regulated by synaptic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5734–5738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin FD, Roth TL, Sweatt JD. Epigenetic regulation of BDNF gene transcription in the consolidation of fear memory. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10576–10586. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1786-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyford GL, Yamagata K, Kaufmann WE, Barnes CA, Sanders LK, Copeland NG, Gilbert DJ, Jenkins NA, Lanahan AA, Worley PF. Arc, a growth factor and activity-regulated gene, encodes a novel cytoskeleton-associated protein that is enriched in neuronal dendrites. Neuron. 1995;14:433–445. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DK, Jang MH, Guo JU, Kitabatake Y, Chang ML, Pow-Anpongkul N, Flavell RA, Lu B, Ming GL, Song H. Neuronal activity-induced Gadd45b promotes epigenetic DNA demethylation and adult neurogenesis. Science. 2009;323:1074–1077. doi: 10.1126/science.1166859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone DF, Schaner MJ, McNaughton BL, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Immediate-early gene expression at rest recapitulates recent experience. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1030–1033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4235-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L, Born J. The contribution of sleep to hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R, Gallais R, Tiffoche C, Le Peron C, Jurkowska RZ, Carmouche RP, Ibberson D, Barath P, Demay F, Reid G, Benes V, Jeltsch A, Gannon F, Salbert G. Cyclical DNA methylation of a transcriptionally active promoter. Nature. 2008;452:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature06544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Sweatt JD. Covalent modification of DNA regulates memory formation. Neuron. 2007;53:857–869. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T, Kubik S, Lewandowski G, Guzowski JF. Networks of neurons, networks of genes: an integrated view of memory consolidation. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:269–284. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T, Kubik S, Haghighi N, Steward O, Guzowski JF. Rapid activation of plasticity-associated gene transcription in hippocampal neurons provides a mechanism for encoding of one-trial experience. J Neurosci. 2009;29:898–906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4588-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Reuter-Lorenz P. The adaptive brain: aging and neurocognitive scaffolding. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:173–196. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plath N, et al. Arc/Arg3.1 is essential for the consolidation of synaptic plasticity and memories. Neuron. 2006;52:437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth TL, Sweatt JD. Regulation of chromatin structure in memory formation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe WB, Blalock EM, Chen KC, Kadish I, Wang D, Barrett JE, Thibault O, Porter NM, Rose GM, Landfield PW. Hippocampal expression analyses reveal selective association of immediate-early, neuroenergetic, and myelinogenic pathways with cognitive impairment in aged rats. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3098–3110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4163-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL, Skaggs WE, Weaver KL. The effect of aging on experience-dependent plasticity of hippocampal place cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6769–6782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06769.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund KD, Connor CM, Campan M, Long TI, Weisenberger DJ, Biniszkiewicz D, Jaenisch R, Laird PW, Akbarian S. DNA methylation in the human cerebral cortex is dynamically regulated throughout the life span and involves differentiated neurons. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Chawla MK, Buonocore M, Rapp PR, Barnes CA. Imaging correlates of brain function in monkeys and rats isolates a hippocampal subregion differentially vulnerable to aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7181–7186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400285101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazdarjanova A, Guzowski JF. Differences in hippocampal neuronal population responses to modifications of an environmental context: evidence for distinct, yet complementary, functions of CA3 and CA1 ensembles. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6489–6496. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazdarjanova A, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Worley PF, Guzowski JF. Experience-dependent coincident expression of the effector immediate-early genes arc and Homer 1a in hippocampal and neocortical neuronal networks. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10067–10071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10067.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbitsky M, Yonan AL, Malleret G, Kandel ER, Gilliam TC, Pavlidis P. Altered hippocampal transcript profile accompanies an age-related spatial memory deficit in mice. Learn Mem. 2004;11:253–260. doi: 10.1101/lm.68204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ. Regionally specific loss of neurons in the aging human hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging. 1993;14:287–293. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(93)90113-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson IA, Ikonen S, Gureviciene I, McMahan RW, Gallagher M, Eichenbaum H, Tanila H. Cognitive aging and the hippocampus: how old rats represent new environments. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3870–3878. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5205-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science. 1993;261:1055–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.8351520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau JL, Olsson T, Morris RG, Noble J, Seckl JR. Decreased NGFI-A gene expression in the hippocampus of cognitively impaired aged rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;42:354–357. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.