Abstract

Hematopoietic growth factors are used to reverse chemotherapy-induced leukopenia. However some factors such as GM-CSF induce osteoclast-mediated bone resorption that can promote cancer growth in bone. Accordingly, we evaluated the ability of GM-CSF to promote bone metastases of breast cancer (BrCa) or prostate cancer (PCa) in a mouse model of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia. In this model, GM-CSF reversed cyclophosphamide-induced leukopenia but also promoted BrCa and PCa growth in bone but not soft tissue sites. Bone growth was associated with induction of osteoclastogenesis, yet in the absence of tumor GM-CSF did not affect osteoclastogenesis. Two osteoclast inhibitors, the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid and the RANKL inhibitor OPG, each blocked GM-CSF-induced tumor growth in bone but did not reverse the ability of GM-CSF to reverse chemotherapy-induced leukopenia. Our findings indicate that it is possible to dissociate bone resorptive effects of GM-CSF, to reduce metastatic risk, from the benefits of this growth factor in reversing leukopenia caused by treatment with chemotherapy.

Introduction

Over 5% of cancer patients have chemotherapy-induced sepsis that is associated with 8.5% of all cancer deaths (1). Granuloctye macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is commonly used to reverse leukopenia is (2, 3). In addition to its pro-hematopoietic effects, GM-CSF has been shown to both increase (4, 5) and decrease osteoclastogenesis (6–8). The conflicting studies were resolved by the demonstration that GM-CSF has a biphasic effect on osteoclast induction (9). Specifically, it was shown that short-term exposure to GM-CSF promotes osteoclastogenesis; whereas, long-term exposure inhibits osteoclastogenesis.

Bone metastasis is a frequent complication of cancers including breast cancer (BrCa) and prostate cancer (PCa) (10). Both BrCa and PCa bone metastases have a bone resorptive component (i.e. osteolytic metastases). Increased osteolytic activity promotes the development and progression of bone metastases (11). The increased osteolytic activity is due to tumor-mediated production of pro-osteoclastogenic factors that induce receptor activator NFkB ligand (RANKL) expression (12). RANKL is a key inducer of osteoclastogenesis through activation of its cognate receptor RANK that is present on osteoclast precursors (13).

Based on the observations that bone resorption promotes bone metastasis and GM-CSF induces osteoclastogenesis, it follows that GM-CSF administration to BrCa or PCa patients may induce bone resorption that promotes bone metastasis. However, the effect of GM-CSF on osteoclastogenesis in the presence of leukopenia, as occurs in patients receiving chemotherapy, is unknown. Accordingly, to recapitulate the clinical scenario, we tested if GM-CSF promotes cancer metastasis in the presence of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia in a murine model.

Materials and Methods

Cells

MDA-231-lux, T47D and MCF-7 BrCa cells were obtained from Dr. Stephen Ethier (Wayne State University). MDA-231-lux was established by stably transfecting MDA-231 BrCa cells with a constitutively active promoter driving luciferase expression (14). PC-3-lux is a PCa cell line that contains a constitutively active promoter driving luciferase expression (15). Cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin.

Animal Studies

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee. Eight-week-old nude mice (female for BrCa and male for PCa) were used. Recombinant murine GM-CSF (rmGM-CSF) dose was determined using a body surface area conversion program (http://www.fda.gov/cder/cancer/animalframe.htm) to determine that 1.4 µg/mouse is equivalent to the clinically used dose of 250 microgram/M2. Cyclophosphamide was administered at 3 mg/mouse via the i.p. route (16). Zoledronic acid (ZA) (Novartis, Switzerland) was administered at 3 µg/mouse subcutaneously (17). Recombinant mouse OPG/Fc chimeric protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was administered at 2mg/kg i.p.twice weekly (18). MDA-231-lux or PC-3-lux were injected into the left cardiac ventricle of mice as described (17, 19). This typically results in 100% of mice having bone tumors in bone and 25% of total tumor in mice as being at soft tissue sites based on imaging and pathological confirmation. To image tumor, luciferin (40 mg/mL) was injected i.p, images were acquired 15 min post-injection using an IVIS Imaging System (Caliper, Hopkinton, MA). Soft versus bone tissue lesions were determined based on location of luciferase positive areas. For areas that were not clearly defined on the original image, a perpendicular image of the animal was taken. Total soft and skeletal tumor burdens per mouse were calculated using summation of individual regions of luciferase-positive areas as described (17, 19). For measurement of osteoclast activity, serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRACP 5b) was quantified using mouse-specific TRACP 5B ELISA (IDS Ltd).

Cell counts

Blood was collected through retro-orbital puncture and total blood counts were performed using hemocytometer. Differential counts were performed on whole blood smears stained in Giemsa. For tumor cells, an aqueous cell viability assay was used per the manufacturer’s directions (Cell Titer96 Aqueous Solution Assay, Promega, Madison, WI). This assay measures the conversion of a tetrazolium salt (MTS) into a water soluble formazen compound using a spectrophotometer.

Measurement of bone lysis

Tibiae were radiographed using a Faxitron X-Ray unit (Faxitron, Lincolnshire, IL), digitized and the lytic area quantified as previously described (20). Briefly, the entire area of the lateral view of the bone is outlined to determine total area and the lytic areas are outlined to determine the percent lytic area. Bone mineral density (BMD) was quantified using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) on an Eclipse peripheral Dexa Scanner using pDEXA Sabre research software (Norland, Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin). ROIs were scanned at 2 mm/s and 0.1 mm × 0.1 mm resolution.

Bone histomorphometry

Bone samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin at 4°C for 24 hr then dehydrated in ethanol. The bone samples were processed, stained with modified Goldner stain and subjected to histomorphometry for osteoclast perimeter and the percent of trabecular bone volume based on the total tissue volume (BV/TV) of the tibia on a BIOQUANT system (R&M Biometrics, Inc. Nashville, TN) as we have previously described (18). For BV/TV the average of the right and left leg values for each animal was used.

Bone marrow cultures for osteoclastogenesis evaluation

To obtain bone marrow cells, tibiae were aseptically removed, ends were cut and marrow cavity was flushed into a dish by injecting MEM into the proximal end using a 21g needle. The bone marrow suspension was agitated to obtain a single cell suspension, cells were washed twice, resuspended in MEM containing 10% FBS, and incubated for 24 h (3 × 105 cells/ml) in a 75-cm2 flask. After 24 h, nonadherent cells were harvested, resuspended (106/ml) in MEM-FBS and cultured in 100 µl of MEM containing 10% FBS, nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, and sRANKL (125 ng/ml) in 96 well plates. In some instances, GM-CSF was added at 10 ng/ml as described. Cells were incubated for 14 days and 50% of the media was refreshed every 3 day.

Statistics

Data was analyzed with Statview Software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley CA). A one-way ANOVA analysis was used with Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis for comparison between multiple groups. A Student’s t test was used for comparison between two groups. Significance was defined as a P value of <0.05.

Results

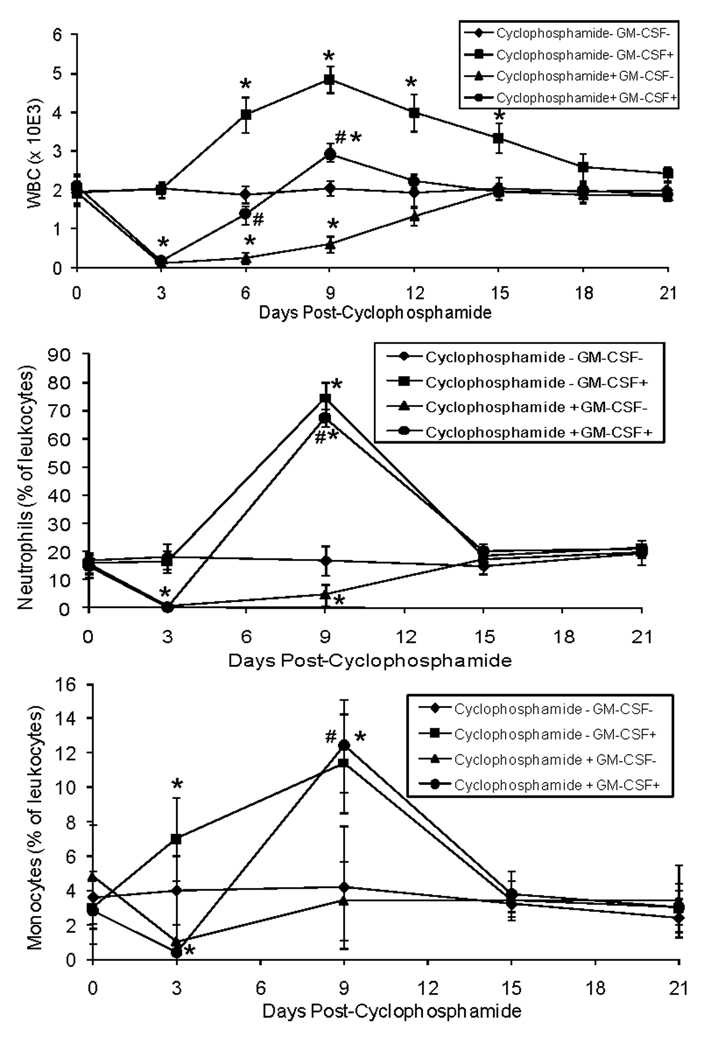

Establishment of a murine model of GM-CSF rescue of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia

To establish a model of leukopenia and GM-CSF rescue, we administered cyclophosphamide followed by rmGM-CSF three days post- cyclophosphamide. Cyclophosphamide induced leukopenia with the nadir at 3 day (Fig. 1). Administration of rmGM-CSF at day 3 post-cyclophosphamide resulted in normal leukocyte levels at 3 days post the nadir compared to 12 days for the mice that received vehicle. Administration of rmGM-CSF induced leukocytosis that normalized at 15 days post-administration. Cyclophosphamide reduced both neutrophils and monocytes and this was reversed rapidly by administration of rmGM-CSF. Taken together, these data demonstrate that administration of cyclophosphamide serves as a functional model of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia that can be reversed by rmGM-CSF.

Figure 1. GM-CSF rapidly reverses cyclophosphamide-induced leukopenia in mice.

On day 0, cyclophosphamide (or saline vehicle) was administered (6 mg/mouse IP) to 8-week-old female nude mice. On day 3, recombinant murine GM-CSF (rmGM-CSF) (or saline vehicle) was administered to mice at 1.4 µg/mouse. Whole blood was collected every 3 days to peform whole blood cell counts (WBC). Differential cell counts were performed on days 0, 3, 9, 15 and 21. (n=5 mice/group). Results are shown as mean±SD. *P<0.05 versus Cyclophosphamide- GM-CSF− group. #P<0.05 versus Cyclophosphamide+ GM-CSF− group.

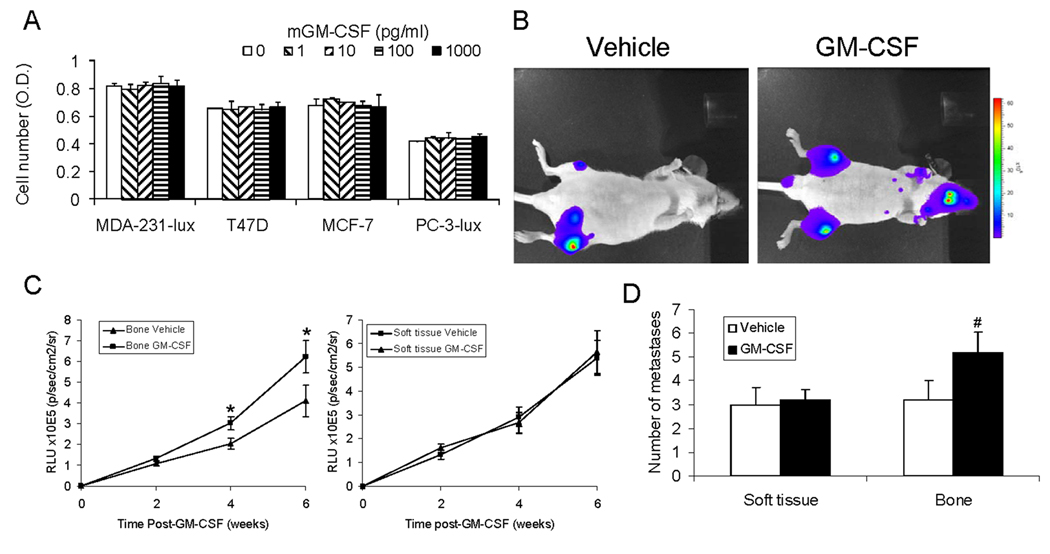

GM-CSF promotes MDA-231 growth in bone but not soft tissue

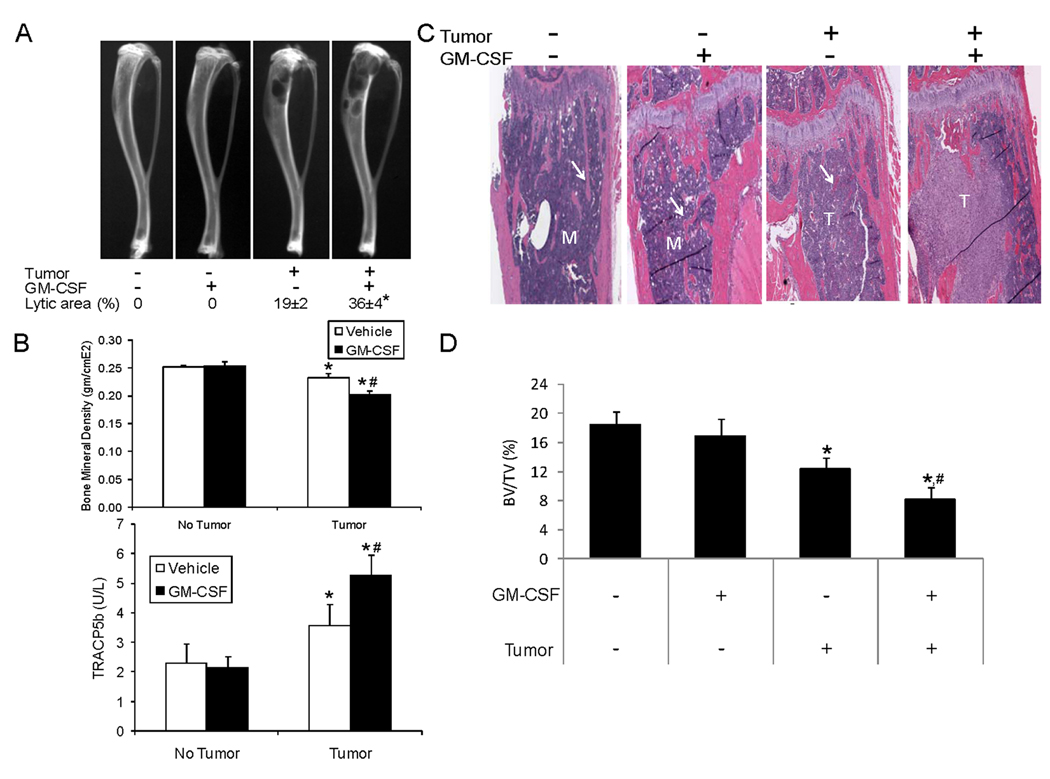

Murine and human GM-CSFs do not cross-react with the other species’ receptors (21). Thus, rmGM-CSF should have no direct effect on human BrCa or PCa cells. To confirm this, we incubated cancer cells with rmGM-CSF and found that it did not impact BrCa or PCa growth (Fig. 2A). To determine the impact of rmGM-CSF on BrCa growth in vivo, MDA-231-lux were injected into the left cardiac ventricle and rmGM-CSF (or saline) was initiated. Administration of rmGM-CSF increased tumor growth in bone, but not soft tissue, compared to vehicle administration (Fig. 2 B and C). The rmGM-CSF-induced increase in tumor bone volume was associated with an increase in the number of bone but not soft tissue metastases (Fig. 2D), which reflected that all sites of skeletal disease were impacted by rmGM-CSF. To determine the impact on the interaction between tumor and bone, we evaluated several parameters of bone remodeling. Specifically, radiographs to observe the lytic area; densitometry to evaluate the bone mineral density (BMD), which is an index of how much mineralized matrix is present; and serum levels of TRACP5b, that reflects overall osteoclast activity. In the absence of tumor, rmGM-CSF did not alter the lytic area, BMD, TRACP5b or metaphyseal trabeculae (Fig. 3). Tumor alone induced osteolysis, reduced BMD, increased serum TRACP5b and decreased metaphyseal trabeculae by approximately 44%. Administration of rmGM-CSF, in the presence of tumor, increased the lytic area by approximately 90%, reduced BMD compared to tumor alone, induced further increases of serum TRACP5b and resulted in greater loss of metaphyseal trabeculae (i.e. total of 56% versus 44%) then tumor alone. Taken together, these results indicate that GM-CSF administration promotes MDA-231 cell growth specifically in bone, which is associated with increased bone resorptive (i.e. osteoclastic) activity.

Figure 2. GM-CSF promotes MDA-231-lux growth in bone, but not soft tissue.

(A) The indicated cancer cells (plated at 5×103 cells/100ml/well in 96 well plates) were treated with rmGM-CSF (or saline vehicle). After 48 hours, cell numbers were quantified using a cell viablity assay measures the conversion of a tetrazolium salt (MTS) into a water soluble formazen compound. Results are from two experiments. Reported as mean±SD. (B–D) MDA-231-lux cells (1×106 cells in 10 µl of PBS) were injected into the left cardiac ventricle and either saline vehicle or GM-CSF (1.4 µg/mouse I.P.) was initiated. Tumor growth was monitored over every 2 weeks using bioluminescence imaging (BLI). (n=5 mice per group). (B) Images of mice with tumors. Color indicates presence of tumor. (C) BLI. Results are reported as mean relative light units (RLU)±SD for either bone (left graph) or soft tissue (right graph). *P<0.05 versus Vehicle at same time point. (D) 6 weeks post-tumor injection, the number of soft tissue or bone metastases detected using BLI were counted. Results are reported as mean±SD number of metastases/mouse. #P<0.05 versus bone metastases in Vehicle-treated mice.

Figure 3. GM-CSF administration increases tumor-induced osteolysis.

MDA-231-lux cells were injected (1×106 cells/10 µl of PBS) into the left cardiac ventricle. Mice were treated with either saline or GM-CSF (1.4 µg/mouse I.P.). Tumor growth was monitored over 6 weeks and mice were sacrificed (n=5 mice/ group). (A) Radiographs from different treatment groups. Note black areas of osteolysis in the proximal tibiae. Radiographs were digitized and the osteolytic area proportion of the tibia was calculated and is reported as mean±SD % osteolytic area. *P<0.05 versus tumor alone. (B) Upper graph: Bone mineral density (BMD) of the proximal tibia was quantified. Results are shown as mean±SD BMD. *P<0.05 versus No Tumor. #P<0.05 versus Vehicle with Tumor. Lower graph: Serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRACP5b) was quantified using ELISA. Results are shown as mean±SD enzyme activity (U/L). P<0.05 versus No Tumor. #P<0.05 versus Vehicle with Tumor. (C) Histological sections of proximal tibiae. Arrows indicate metaphyseal trabeculae; T indicates tumor; M indicates normal marrow. Note loss of trabeculae in GM-CSF− group compared to no tumor groups and extensive loss of trabeculae in Tumor:GM-CSF+ group compared to Tumor:GM-CSF− group. (D) Histomorphometric measurement of trabecular bone. Trabecular bone volume (BV) and total tissue volume (TV) were averaged between both tibia of each mouse and reported as BV/TV (%)±SD. *P<0.05 versus No tumor and no GM-CSF; #P<0.05 versus Tumor and no GM-CSF.

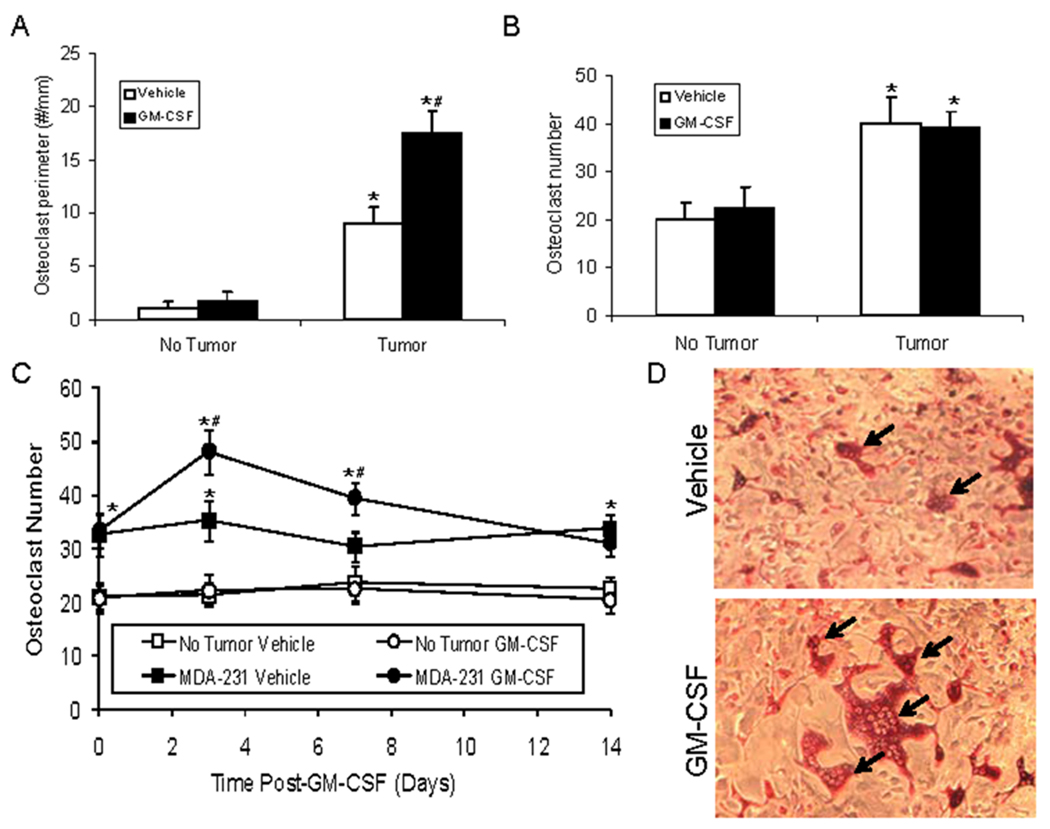

GM-CSF promotes MDA-231-induced osteoclastogenesis

To determine the role of GM-CSF directly on osteoclast activity versus tumor-induced osteoclast activity, we next determined the impact of rmGM-CSF administration on osteoclastogenesis in the context of tumor. In tumor absence, rmGM-CSF had no impact on osteoclast numbers (i.e., osteoclast perimeter) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, tumor alone increased osteoclast perimeter which was further increased by rmGM-CSF (Fig 4A). To determine if GM-CSF directly impacted osteoclastogenesis, we obtained marrow stromal cells from mice with or without intrafemoral MDA-231 tumor growth and incubated them with rmGM-CSF. Marrow stromal cells derived from mice with intraosseous tumor produced more osteoclasts than stromal cells derived from mice without tumor (Fig. 4B). However, administration of rmGM-CSF in vitro had no impact on osteoclast numbers produced by marrow stromal cells derived from mice with or without tumor present in the bone (Fig. 4B). These results were consistent with the increased osteolysis and osteoclast perimeter induced by the presence of tumor; however, they appeared to conflict with the in vivo results that demonstrated GM-CSF increased osteoclast perimeter in the presence of tumor (Fig. 4A). One possibility was that the increase of osteoclasts occurs in vivo only in the presence of tumors. To determine if the GM-CSF induced an increase of osteoclast production in vivo in presence of tumors, we injected mice with saline or MDA-231 cells; let tumors become established over 14 days, then administered GM-CSF or vehicle and after 24 hours collected bone marrow cells to evaluate their osteoclastogenic potential. In the absence of tumor, GM-CSF had no impact on osteoclast numbers; however, in the presence of tumor, GM-CSF induced an increase in bone marrow-stromal-derived osteoclasts that was observed at three and seven days post- GM-CSF administration (Fig. 4C and D). Taken together, these results indicate that GM-CSF promotes osteoclastogenesis indirectly with a requirement for tumor presence in vivo.

Figure 4. GM-CSF requires presence of tumor to promote osteolysis in vivo.

(A) MDA-231-lux cells were injected (1×106 cells/10 µl of PBS) into the left cardiac ventricle of mice and either saline vehicle or GM-CSF (1.4 µg/mouse I.P.) was initiated. Tumor growth was monitored over a period of 6 weeks and mice were sacrificed, tibiae collected and subjected to histomorphometry for osteoclast perimeter. (N=5/group). Results are shown as mean±SD osteoclast perimeter. *P<0.05 versus No Tumor. #P<0.05 versus Vehicle with Tumor. (B) MDA-231-lux cells (or saline vehicle) were injected (1×105 cells/10 µl of PBS) into the proximal tibia. After two weeks, mice were sacrificed and tibiae were flushed to obtain marrow cells. Marrow cells were plated and either vehicle or rmGM-CSF (10 ng/ml) was added to the media. After 14 days, cells were stained with TRAP and multinucleated TRAP+ cells were quantified. Results are reported as mean±SD osteoclasts per well. *P<0.05 versus No Tumor. (C and D) MDA-231-lux cells (or saline vehicle) were injected (1×105 cells in 10 µl of PBS) into the proximal tibia. After two weeks, mice were treated with either saline vehicle or GM-CSF (1.4 µg/mouse I.P.) and marrow was collected by flushing the tibiae at the indicated time points. Marrows were subjected to culturing and osteoclasts were identified as in (B). Results are reported as mean±SD osteoclasts per well. *P<0.05 versus No Tumor; #P<0.05 versus MDA-231 and Vehicle. (D) Demonstration of osteoclasts in cultures from mice bearing MDA-231 with either Vehicle or GM-CSF treatment. Arrows indicate osteoclast-like cells.

Inhibition of osteoclastogenesis blocks GM-CSF-induced MDA-231 cell growth in bone

That GM-CSF had no direct effect on BrCa cell proliferation in vitro (Fig. 2A) suggested it promotes BrCa growth through an indirect mechanism in vivo. Induction of bone remodeling promotes the ability of cancers, including BrCa and PCa, to grow in bone (17, 22, 23). Accordingly, we assessed if blocking GM-CSF-induced osteoclastogenesis would prevent GM-CSF-induced BrCa growth in bone. To accomplish this, the bisphosphonate ZA or vehicle was administered. After two weeks, MDA -231 cells were injected into the left cardiac ventricle and GM-CSF or vehicle was administered three days later. Tumor burden was monitored over 6 weeks. As observed earlier, GM-CSF administration promoted tumor growth in bone (Fig. 5A). Pre-treatment with ZA inhibited the GM-CSF-induced tumor growth. ZA alone also inhibited tumor growth. There was no difference in the levels of tumor growth between ZA alone compared to ZA in the presence of GM-CSF. Finally, ZA had no impact on MDA-231 growth in soft tissue in the presence or absence of GM-CSF (Fig. 5A). Taken together, these data indicate that ZA blocks the GM-CSF effect through a mechanism that is specific to the bone microenvironment and is consistent with the concept that GM-CSF mediates its pro-tumorigenic effects in bone through induction of osteoclastogenesis.

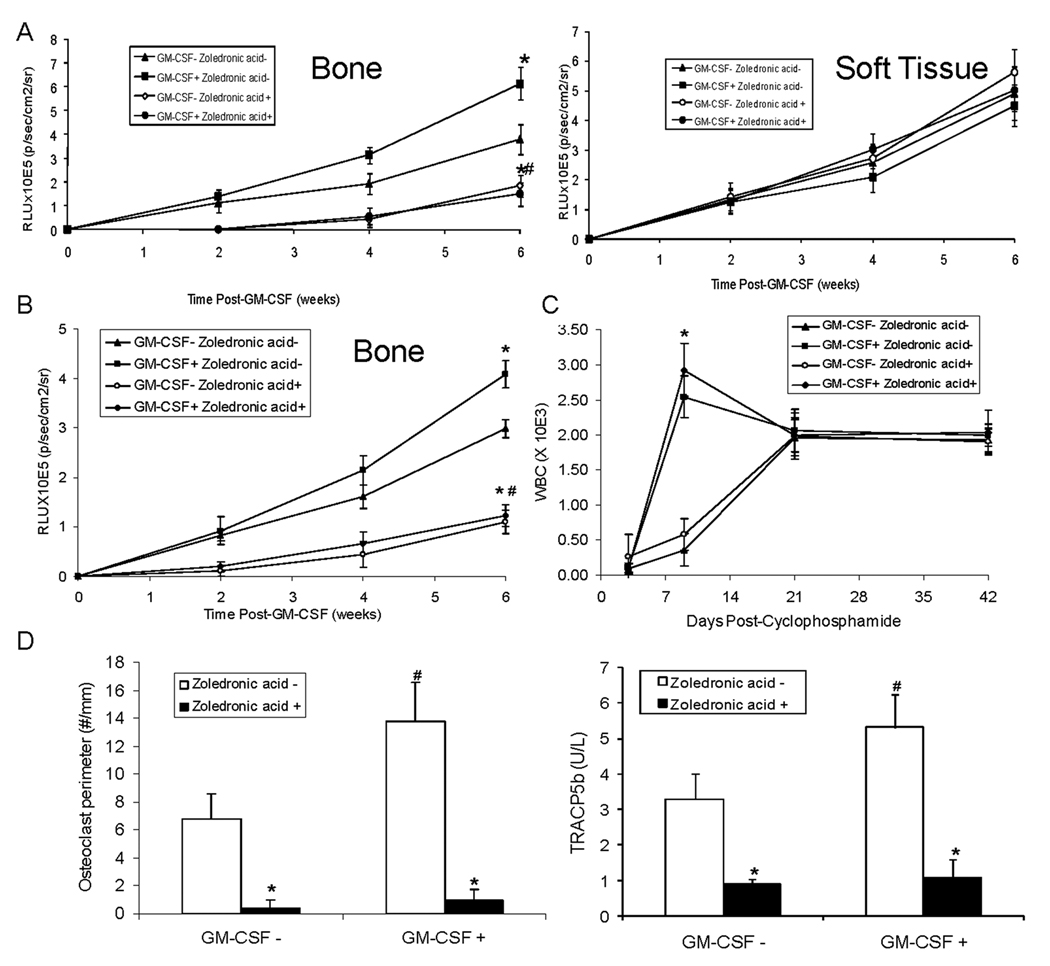

Figure 5. Zoledronic acid (ZA) can block GM-CSF induced intraosseous MDA-231 growth without blocking GM-CSF’s ability to reverse leukopenia.

(A) ZA (3µg/mouse subcutaneously) or saline vehicle was administered. Two weeks after the initiation of ZA, MDA-231-lux cells were injected (1×106 cells in 10 µl of PBS) into the left cardiac ventricle. Mice were treated with either saline vehicle or GM-CSF (1.4 µg/mouse I.P.). Tumor growth was monitored over a period of 6 weeks using in vivo bioluminescence every two weeks. (N=5/group). Results are reported as mean relative light units (RLU)±SD for either bone or soft tissue. *P<0.05 versus GM-CSF− & ZA −; #P<0.05 versus GM-CSF+ & ZA. (B through D) ZA (3µg/mouse subcutaneously one time) or saline vehicle were administered to mice Two weeks after the initiation of ZA, cyclophosphamide (or saline vehicle) was administered (6 mg/mouse IP) and MDA-231-lux cells were injected (1×106 cells in 10 µl of PBS) into the left cardiac ventricle. Three days after injection of tumors into mice, they were treated with either saline vehicle or GM-CSF (1.4 µg/mouse I.P.) and tumor growth was monitored using bioluminescence every two weeks. There were 5 mice per treatment group. (B) Results are reported as mean relative light units (RLU)±SD for tumor growth in bone. *P<0.05 versus GM-CSF− & ZA −; #P<0.05 versus GM-CSF+ & ZA−. (C) Whole blood was obtained at 0, 3, 9, 21 and 42 days post-administration of Cyclophosphamide using retro-orbital puncture. Total white blood cell counts were performed. Results are shown as mean±SD. *P<0.05 versus GM-CSF− for each respective drug. (D) At the end of the study, tibiae were harvested and subjected to histomorphometry for osteoclast perimeter (reported as mean±SD osteoclast perimeter) and serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRACP5b) (quantified using ELISA; reported as mean±SD enzyme activity (U/L)). *P<0.05 versus ZA−; #P<0.05 versus GM-CSF− & ZA−.

ZA can block GM-CSF induced intraosseous MDA-231 growth without blocking GM-CSF’s ability to reverse leukopenia

GM-CSF is administered during periods of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia that occurs secondary to destruction of cycling progenitor marrow cells. It is unclear if this destruction also impacts osteoclast production. In order to explore this uncertainty and recapitulate the clinical situation, we assessed if GM-CSF impacts cancer growth in bone in the presence of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia. Mice were treated with ZA (or vehicle) and two weeks later, MDA-231 cancer cells were injected into the left cardiac ventricle and cyclophosphamide was administered at the same time. Three days post-administration of cyclophosphamide GM-CSF (or vehicle) was administered and animals were followed over 6 weeks using BLI. Even in the presence of cyclophosphamide, GM-CSF induced cancer growth in bone and ZA inhibited this (Fig. 5B). To confirm the presence of leukopenia, we performed WBCs. As anticipated, leukopenia was present three days post-cyclophosphamide. GM-CSF reversed the leukopenia within 6 days after its administration; whereas, the mice that did not receive GM-CSF still had moderate leukopenia at this timepoint (Fig. 5C). (Neutropenia paralleled the total WBC; data not shown). By day 21, all groups had normal WBCs. To determine if the presence of osteolytic activity reflected the presence of tumor and GM-CSF in this clinical model we measured osteoclast perimeter and TRACP5b. Even in the presence of the chemotherapy-induced leukopenia that occurred at day three, at the end of the study at six weeks, administration of GM-CSF at day three induced an increase in osteoclast perimeter that was observed as late as six weeks (Fig. 5D). Administration of ZA blocked the GM-CSF induction of osteoclast perimeter. The induction of osteoclast activity by GM-CSF and its inhibition by ZA was reflected by serum TRACP5b levels (Fig. 5D). In summary, mice receiving chemotherapy developed leukopenia at day three, at which time GM-CSF was administered, which resolved the leukopenia by day nine and was associated with increased osteoclast perimeter at week 6. Furthermore, treatment with ZA prior to administration of GM-CSF did not inhibit GM-CSF’s restoration of the WBC, but did inhibit the GM-CSF-induced tumor growth and increase of osteoclast perimeter.

ZA or OPG can block GM-CSF induced intraosseous PC-3-lux growth without blocking GM-CSF’s ability to reverse leukopenia

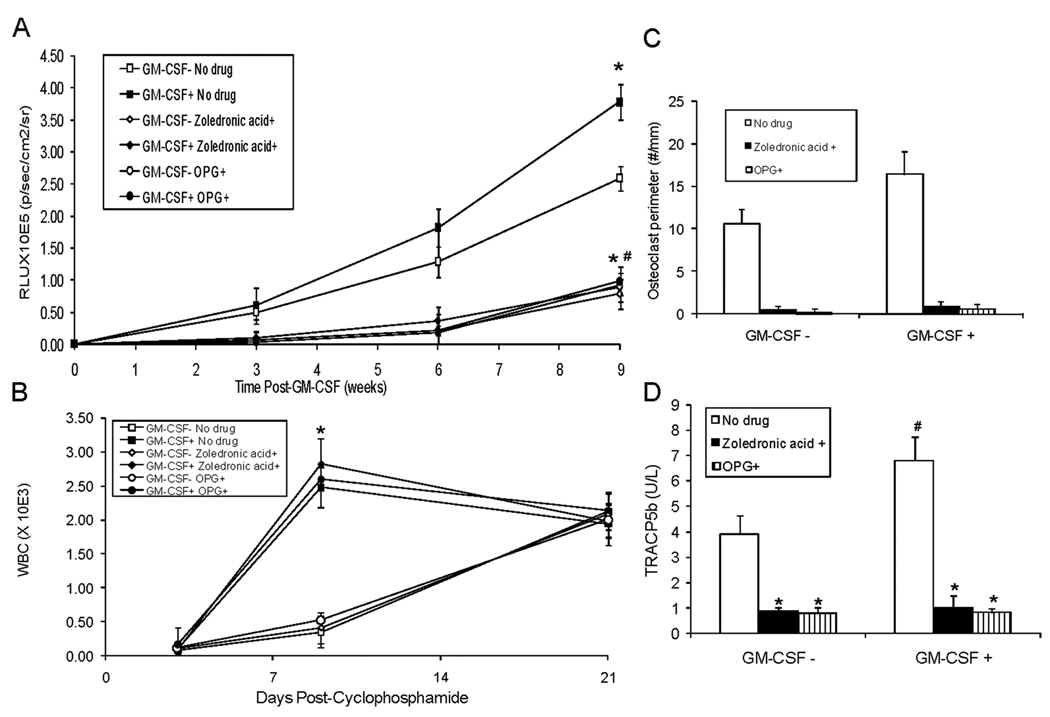

To determine if these results were specific to BrCa or relevant to other cancers we used PC-3 PCa cells. Furthermore, to evaluate if the inhibitory effects on tumor growth were specific to ZA, we used an additional method to inhibit osteoclast activity. Specifically, we treated an additional group with an inhibitor of RANKL, osteoprotegerin (OPG) (24). We and others have shown that OPG blocks tumor-induced osteoclastogenesis mediated by RANKL (18, 25). Mice were treated with ZA (1×), OPG (twice weekly for a total of 4 weeks) or vehicle. Two weeks after initiation of drugs, PC-3-lux PCa cells were injected into the left cardiac ventricle and cyclophosphamide was administered. Three days post-administration of cyclophosphamide, GM-CSF (or vehicle) was administered and tumor burden was monitored over 9 weeks. Similar to the results for the MDA-231 BrCa cell line, in the presence of cyclophosphamide, GM-CSF induced cancer growth in bone (Fig. 6A, see GM-CSF− ZA−/OPG− versus GM-CSF+ ZA−/OPG−). As previously observed for MDA-231, ZA inhibited the GM-CSF-induced cancer growth (Fig. 6A, see GM-CSF+ ZA−/OPG− versus GM-CSF+ ZA+). Similarly, OPG had as potent an inhibitory effect on GM-CSF-induced cancer growth as did ZA (Fig. 6A, see GM-CSF+ ZA−/OPG− versus GM-CSF+OPG+). GM-CSF reversed the cyclophosphamide-induced leukopenia in the presence of PC-3-lux and ZA or OPG with kinetics similar to that observed for MDA-231 (Fig 6B). These results indicate that both ZA and OPG can inhibit GM-CSF-mediated tumor growth in bone, while having no impact on GM-CSF’s ability to reverse leukopenia. To determine if the presence of osteolytic activity reflected the presence of tumor and GM-CSF in this PC-3 PCa model of the clinical scenario we measured osteoclast perimeter and TRACP5b. Even in the presence of the chemotherapy-induced leukopenia that occurs at day three, at the end of the study at nine weeks, administration of GM-CSF at day three induced an increase in osteoclast perimeter that was observed as late as nine weeks. Administration of ZA or OPG blocked the GM-CSF induction of osteoclast perimeter. (Fig. 6C). The induction of osteoclast activity by GM-CSF and its inhibition by ZA or OPG was reflected by serum TRACP5b levels (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. Zoledronic acid (ZA) or OPG can block GM-CSF induced intraosseous PC-3-lux growth.

ZA (3µg/mouse subcutaneously one time), OPG (2mg/kg i.p. twice weekly) or saline vehicle were administered to mice. Two weeks after the initiation of ZA or OPG, cyclophosphamide (6 mg/mouse) or an equivalent volume of saline vehicle was administered i.p. immediately followed by injection of PC-3-lux cells (1×106 cells in 10 µl of PBS) into the left cardiac ventricle. Three days after injection of PC-3-lux cells into mice, they were treated with either GM-CSF (1.4 µg/mouse) or an equivalent volume of saline vehicle i.p. and tumor growth was monitored over a period of 9 weeks using bioluminescence every three weeks. (N=5/group). (A) Results are reported as mean relative light units (RLU)±SD for tumor growth in bone. *P<0.05 versus GM-CSF− & ZA−/OPG−; #P<0.05 versus GM-CSF+ & ZA−/OPG−. (B) Whole blood was obtained at 0, 3 and 21 days post-administration of cyclophosphamide. WBCs were performed. Results are shown as mean±SD. *P<0.05 versus GM-CSF− for each respective drug. (C) At the end of the study, tibiae were harvested and subjected to histomorphometry for osteoclast perimeter. Results are shown as mean±SD osteoclast perimeter. *P<0.05 versus No drug; #P<0.05 versus GM-CSF− & No Drug. (D) Serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRACP5b) was quantified using ELISA. Results are shown as mean±SD enzyme activity (U/L). *P<0.05 versus No drug; #P<0.05 versus GM-CSF− & No drug.

Discussion

In the current study, we uncovered a previously unidentified risk associated with administration of GM-CSF for treatment of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia. Specifically, our work demonstrates that administration of GM-CSF to reverse chemotherapy-induced leukopenia promotes growth of BrCa and PCa in bone through induction of osteoclast activity. Furthermore, we identified that administration of an osteoclast inhibitor in conjunction with GM-CSF diminishes the induction of metastasis. The ability to dissociate the pro-metastatic osteoclastogenic activity from the ability to reverse leukopenia provides a potential therapeutic approach to diminish the morbidity associated with chemotherapy-induced leukopenia without adding additional therapy-induced risk for tumor progression.

G-CSF and GM-CSF are frequently administered in to reverse chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (26, 27). G-CSF has osteoclastic effects and pro-metastatic effects in bone (28); however, the effects of GM-CSF on osteoclastogenesis in the context of tumor were less known. Several studies have demonstrated that GM-CSF inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro; whereas, other reports have demonstrated that GM-CSF stimulates osteoclastogenesis (5, 9, 29). Of particular note is that short-term administration of GM-CSF, similar to how it would be used in the clinical scenario, was shown to induce osteoclasts in a murine model (29). One potential reason for the conflicting results was that the latter studies were performed in the face of an inflammatory environment in which a variety of cytokines are present that could confer a pro-osteoclastogenic effect on GM-CSF. We have previously reported that some BrCa cells produce GM-CSF that promotes bone metastasis through induction of osteoclastogenesis (30) which led to the supposition that administration of GM-CSF may promote the same pro-metastatic osteoclastogenic activity (31). In the current study, GM-CSF was administered in the context of cancer. This suggests that the cancer cells themselves provided factors that conferred pro-osteoclastogenic activity on GM-CSF. Another, possibility is that the tumor microenvironment itself may be pro-inflammatory through stromal production of cytokines and migration of leukocytes into the tumor (32). Thus, the pro-inflammatory tumor microenvironment may have conferred pro-osteoclastogenic activity on GM-CSF.

In light of the observation that increased bone resorption promotes bone metastasis (33) and the possibility the GM-CSF induces bone resorption through osteoclastogenesis, we hypothesized that administration of GM-CSF during chemotherapy-induced leukopenia would promote bone metastasis. We demonstrated that although murine GM-CSF had no direct affect on human cancer cells, administration of mGM-CSF promoted growth of cancer in bone, but not soft tissue. These results are consistent with the observations that (1) ZA had no impact on PCa growth in soft tissues; whereas, it inhibited growth in bone in vivo (34) and (2) ZA inhibited tumor-induced osteolysis and directly proportional to tumor burden (17). This indicates that GM-CSF promotes receptivity of bone but not soft tissue microenvironments for cancer establishment. This occurred in a background of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia; thus, making it clinically relevant. This suggests that clinical administration of GM-CSF to reverse chemotherapy-induced leukopenia may ultimately promote bone metastasis in patients. Our results are consistent with the observation that G-CSF, a known inducer of osteoclast activity, was demonstrated to induce tumor growth in bone in a murine model through a dependency on osteoclasts (28).

Several lines of evidence indicated that GM-CSF promoted osteoclast activity in our model system including increased serum TRACP, radiographic osteolysis, osteoclast perimeter and decreased BMD. The induction of osteoclast activity appeared critical for the development of tumor growth in bone. That ZA inhibited both bone resorption and tumor growth in bone; but not in soft tissue, indicated that ZA indirectly inhibited tumor growth through the bone microenvironment. This appears to be in conflict with the previous findings that ZA directly induced apoptosis in BrCa cells (35, 36) and PCa cells (37, 38) in vitro. However, the direct cytotoxic effects of bisphosphonates is controversial as several studies indicate that bisphosphonates have no pro-apoptotic effect (39) or were inconclusive (40) and the lack of anti-tumor effects upon bisphosphonates administration clinically (33). That OPG inhibited GM-CSF-induced tumor growth similarly to ZA provides further support that the anti-tumor effect is mediated through the bone microenvironment as opposed to directly by ZA. In support of this possibility is the previous report that OPG has no direct effect on PCa cell growth in vitro or at soft tissue sites in vivo (18).

In summary, we have demonstrated that administration of GM-CSF in a model of chemotherapy-induced leukopenia promotes establishment of cancer growth in bone. Furthermore, we determined that use of osteoclast inhibitors were able to dissociate the osteoclastic activity from the pro-leukocytic activity allowing for rapid restoration of leukocyte numbers while blocking the GM-CSF-induced growth of tumor in bone. These findings suggest that careful consideration should be given for the potential impact on tumor progression that clinical use of GM-CSF (and presumably G-CSF) for chemotherapy-induced leukopenia could have. Furthermore, this study indicates that methods to reverse leukopenia without promoting osteoclastogenesis should be developed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01CA093900 to E.T. Keller.

References

- 1.Williams MD, Braun LA, Cooper LM, et al. Hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis: analysis of incidence, mortality, and associated costs of care. Crit Care. 2004;8:R291–R298. doi: 10.1186/cc2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Disis ML. Clinical use of subcutaneous G-CSF or GM-CSF in malignancy. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bregni M, Siena S, Ravagnani F, Bonadonna G, Gianni AM. High-dose cyclophosphamide in patients with operable breast cancer: recombinant human GM-CSF ameliorates drug-induced leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Haematologica. 1990;75 Suppl 1:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myint YY, Miyakawa K, Naito M, et al. Granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-3 correct osteopetrosis in mice with osteopetrosis mutation. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:553–566. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65301-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nomura K, Kuroda S, Yoshikawa H, Tomita T. Inflammatory osteoclastogenesis can be induced by GM-CSF and activated under TNF immunity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367:881–887. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grcevic D, Lukic IK, Kovacic N, Ivcevic S, Katavic V, Marusic A. Activated T lymphocytes suppress osteoclastogenesis by diverting early monocyte/macrophage progenitor lineage commitment towards dendritic cell differentiation through down-regulation of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB and c-Fos. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:146–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorny G, Shaw A, Oursler MJ. IL-6, LIF, and TNF-alpha regulation of GM-CSF inhibition of osteoclastogenesis in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 2004;294:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn JM, Horwood NJ, Elliott J, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ. Fibroblastic stromal cells express receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand and support osteoclast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:1459–1466. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.8.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodge JM, Kirkland MA, Aitken CJ, et al. Osteoclastic potential of human CFU-GM: biphasic effect of GM-CSF. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:190–199. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chirgwin JM, Guise TA. Skeletal metastases: decreasing tumor burden by targeting the bone microenvironment. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:1333–1342. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roodman GD. High bone turnover markers predict poor outcome in patients with bone metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4821–4822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller ET. The role of osteoclastic activity in prostate cancer skeletal metastases. Drugs Today (Barc) 2002;38:91–102. doi: 10.1358/dot.2002.38.2.820105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougall WC, Glaccum M, Charrier K, et al. RANK is essential for osteoclast and lymph node development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2412–2424. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cailleau R, Young R, Olive M, Reeves WJ., Jr Breast tumor cell lines from pleural effusions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1974;53:661–674. doi: 10.1093/jnci/53.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall CL, Bafico A, Dai J, Aaronson SA, Keller ET. Prostate cancer cells promote osteoblastic bone metastases through Wnts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7554–7560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka T, Okamura S, Okada K, et al. Protective effect of recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in leukocytopenic mice. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1792–1799. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1792-1799.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider A, Kalikin LM, Mattos AC, et al. Bone turnover mediates preferential localization of prostate cancer in the skeleton. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1727–1736. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Dai J, Qi Y, et al. Osteoprotegerin inhibits prostate cancer-induced osteoclastogenesis and prevents prostate tumor growth in the bone. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1235–1244. doi: 10.1172/JCI11685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun YX, Schneider A, Jung Y, et al. Skeletal localization and neutralization of the SDF-1(CXCL12)/CXCR4 axis blocks prostate cancer metastasis and growth in osseous sites in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:318–329. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn LK, Mohammad KS, Fournier PG, et al. Hypoxia and TGF-beta drive breast cancer bone metastases through parallel signaling pathways in tumor cells and the bone microenvironment. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall PD, Kreitman RJ, Willingham MC, Frankel AE. Toxicology and pharmacokinetics of DT388-GM-CSF, a fusion toxin consisting of a truncated diphtheria toxin (DT388) linked to human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) in C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;150:91–97. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Y, Zhou H, Fong-Yee C, Modzelewski JR, Seibel MJ, Dunstan CR. Bone resorption increases tumour growth in a mouse model of osteosclerotic breast cancer metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10585-008-9172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozlow W, Guise TA. Breast cancer metastasis to bone: mechanisms of osteolysis and implications for therapy. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10:169–180. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-5399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostenuik PJ, Shalhoub V. Osteoprotegerin: a physiological and pharmacological inhibitor of bone resorption. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:613–635. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quinn JE, Brown LG, Zhang J, Keller ET, Vessella RL, Corey E. Comparison of Fc-osteoprotegerin and zoledronic acid activities suggests that zoledronic acid inhibits prostate cancer in bone by indirect mechanisms. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005 doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crawford J, Dale DC, Kuderer NM, et al. Risk and timing of neutropenic events in adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: the results of a prospective nationwide study of oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6:109–118. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2008.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, Lyman GH. Impact of primary prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on febrile neutropenia and mortality in adult cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3158–3167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirbe AC, Uluckan O, Morgan EA, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor enhances bone tumor growth in mice in an osteoclast-dependent manner. Blood. 2007;109:3424–3431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-048686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takamatsu Y, Simmons PJ, Moore RJ, Morris HA, To LB, Levesque JP. Osteoclast-mediated bone resorption is stimulated during short-term administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor but is not responsible for hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization. Blood. 1998;92:3465–3473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park BK, Zhang H, Zeng Q, et al. NF-kappaB in breast cancer cells promotes osteolytic bone metastasis by inducing osteoclastogenesis via GM-CSF. Nat Med. 2007;13:62–69. doi: 10.1038/nm1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roodman GD. Bone-breaking cancer treatment. Nat Med. 2007;13:25–26. doi: 10.1038/nm0107-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winter MC, Holen I, Coleman RE. Exploring the anti-tumour activity of bisphosphonates in early breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:453–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corey E, Brown LG, Quinn JE, et al. Zoledronic Acid exhibits inhibitory effects on osteoblastic and osteolytic metastases of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:295–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senaratne SG, Pirianov G, Mansi JL, Arnett TR, Colston KW. Bisphosphonates induce apoptosis in human breast cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1459–1468. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jagdev SP, Coleman RE, Shipman CM, Rostami HA, Croucher PI. The bisphosphonate, zoledronic acid, induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells: evidence for synergy with paclitaxel. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1126–1134. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan C, Lewis PD, Jones RM, Bertelli G, Thomas GA, Leonard RC. The in vitro anti-tumour activity of zoledronic acid and docetaxel at clinically achievable concentrations in prostate cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:669–677. doi: 10.1080/02841860600996447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coxon JP, Oades GM, Kirby RS, Colston KW. Zoledronic acid induces apoptosis and inhibits adhesion to mineralized matrix in prostate cancer cells via inhibition of protein prenylation. BJU Int. 2004;94:164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-4096.2004.04831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boissier S, Ferreras M, Peyruchaud O, et al. Bisphosphonates inhibit breast and prostate carcinoma cell invasion, an early event in the formation of bone metastases. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2949–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knight LA, Conroy M, Fernando A, Polak M, Kurbacher CM, Cree IA. Pilot studies of the effect of zoledronic acid (Zometa) on tumor-derived cells ex vivo in the ATP-based tumor chemosensitivity assay. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16:969–976. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000176500.56057.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]