Abstract

We report a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of major depressive disorder (MDD) in 1,221 cases from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study and 1,636 screened controls. No genome-wide evidence for association was detected. We also carried out a meta-analysis of three European-ancestry MDD GWAS datasets: STAR*D, Genetics of Recurrent Early-Onset Depression (GenRED) and the publicly-available Genetic Association Information Network MDD dataset (GAIN-MDD). These datasets, totaling 3,957 cases and 3,428 controls, were genotyped using four different platforms (Affymetrix 6.0, 5.0 and 500K, and Perlegen). For each of 2.4 million HapMap II SNPs, using genotyped data where available and imputed data otherwise, single-SNP association tests were carried out in each sample with correction for ancestry-informative principal components. The strongest evidence for association in the meta-analysis was observed for intronic SNPs in ATP6V1B2 (P = 6.78 × 10−7), SP4 (P = 7.68 × 10−7) and GRM7 (P = 1.11 × 10−6). Additional exploratory analyses were carried out for a narrower phenotype (recurrent MDD with onset before age 31, N = 2,191 cases), and separately for males and females. Several of the best findings were supported primarily by evidence from narrow cases or from either males or females. Based on previous biological evidence, we consider GRM7 a strong MDD candidate gene. Larger samples will be required to determine whether any common SNPs are significantly associated with MDD.

Keywords: major depressive disorder; genetics; GWAS; meta-analysis, neuroscience

Introduction

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is the leading cause of disability for adults under 45 years of age1, and has a lifetime incidence of 12–20%.2 Twin studies suggest a heritability of about 40% (perhaps higher in clinical samples), with a 2–3-fold increased risk to first-degree relatives of MDD probands.3 There are no established neurobiological mechanisms or definitive genetic associations. Here, we report on a new genome-wide association study (GWAS) of MDD in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) sample, and on a meta-analysis of STAR*D and two other datasets: the Genetics of Recurrent Early-Onset Depression (GenRED) GWAS reported in a companion article4; and GAIN-MDD, a dataset that was analyzed in the first MDD GWAS report5 and that has been made available to scientists through the dbGAP (Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes) repository.6

The new GWAS sample includes 1,221 cases from STAR*D, a multi-center, NIMH-sponsored antidepressant clinical trial.7, 8 The GenRED GWAS4 included 1,020 cases, with 1,636 controls from the Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia (MGS) study9 (excluding controls who reported any history of MDD). The STAR*D analysis uses the same control data, and our meta-analysis corrects for that overlap. We accessed the GAIN-MDD dataset and carried out a new analysis (for methodological consistency) of 1,715 cases and 1,792 controls, slightly smaller than the published sample5 but with very similar results.

GWAS methods evaluate the contribution of common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to common diseases. They have identified robust associations to many non-psychiatric disorders10 and to bipolar disorder11, schizophrenia12–14 and autism.15 No genome-wide significant findings were reported for GAIN-MDD5 or GenRED4, or for a GWAS (not included in this meta-analysis) of 1,514 recurrent MDD cases and 2,052 controls (without lifetime depressive or anxiety disorders) from a German clinical sample and a Swiss population-based sample.16 This is not surprising, as most GWAS findings have emerged when multiple datasets were combined to achieve large sample sizes (often 10,000–20,000 cases plus controls) with power to detect variants that produce small increases in risk.10 We have reported separate GenRED and STAR*D analyses, because their distinctive characteristics could prove relevant to interpreting results across studies in the future, but to achieve a larger sample size we also report a meta-analysis of STAR*D, GenRED and GAIN-MDD data.

Materials and Methods

SUBJECTS

STAR*D

Cases were participants in STAR*D. Individuals (ages 18–75) were enrolled from primary care or psychiatric outpatient clinics if they had a diagnosis of MDD (by clinician rating of DSM-IV criteria) and a current 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating score of ≥14 by independent raters7, 8 (although that score did not capture the severity of past depression). Of 1,953 participants who donated DNA, we selected the 1,500 who self-identified as “white” as they represented most of the sample and European-ancestry controls were available. Following quality control (QC) procedures (described below), 1,221 cases were available for analyses. All subjects signed informed consent for genetic studies. Work described here was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco.

Controls were the same as those used in the GenRED GWAS analysis.4 Details are described elsewhere.9, 13 They were recruited for MGS by a survey research company (Knowledge Networks, Inc., Menlo Park, CA) from a nationally-representative internet-based panel that was selected by random digit dialing. Participants had completed an online version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF)17 for lifetime history of common mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. They consented to anonymization and deposition of their DNA and clinical information in the NIMH repository for use in any medical research. The 1,636 European-ancestry controls used here had no lifetime history of MDD (or of recurrent depression missing MDD by one criterion) by CIDI-SF criteria (which over-diagnose MDD18). The MGS collaboration gave permission for us to use genotypes for the part of the control sample that is still under a dbGAP publication embargo. Clinical and demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of STAR*D participants

| Cases | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 1,221 | 1,636 |

| Age | 42.8 ± 13.6 | 52.5 ± 17.2 |

| Female | 58.6% (715) | 43.9% (718) |

| Initial HAM-D | 18.4 ± 6.6 | |

| Age of 1stMDE | 27.3 ± 12.9 | |

| Recurrent MDD | 73.8% (901) | |

| Presence of comorbid anxiety disorder (GAD, panic, social phobia, OCD) | 463 (37.9%) |

Shown are mean ± SD for age, first HAM-D score after study entry, and age of first major depressive episode (MDE); and numbers for other variables (i.e., 1st major depressive episode) are percents, with correponding Ns in parentheses.

Meta-analysis

GenRED cases (N = 1,020) were recruited from multiple clinical settings and media and internet announcements and advertisements. Cases were assessed with the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies19 (DIGS, version 3; http://nimhgenetics.org) and consensus best estimate diagnoses were assigned by review of DIGS, informant report and available psychiatric records.4 Probands had recurrence (two or more episodes, or one episode lasting at least three years), onset before age 31, and recurrent MDD in a sibling or parent with onset before age 41 (but no suspected bipolar-I disorder in a sibling or parent), features which predict greater familial liability to MDD.3, 20, 21 The GenRED GWAS used the same MGS controls as STAR*D (see above). GAIN-MDD recruited individuals from a twin registry and two population-based samples in the Netherlands, selecting cases who received MDD diagnoses based on a Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), and controls without MDD and without high neuroticism scores.5 Each study excluded bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and more severe substance use disorders, with minor differences in exclusion criteria.

For meta-analysis, we defined two phenotypic models: Broad (all 3,957 MDD cases from the three samples, vs. 3,428 controls), and Narrow (2,191 cases with onset before age 31 and recurrence, including GenRED chronic cases). We did not require positive family history because STAR*D and GAIN-MDD assessed this by proband response to a single question. Exploratory separate analyses of males and females were carried out for each phenotype, because women are at a two-fold increased risk, and twin studies suggest partial independence of genetic risk factors for women and men.22, 23 Characteristics of the three samples are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Samples and SNPs included in meta-analysis

| GAIN | GenRED | STAR*D | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects (Males+Females) | ||||

| Broad cases | 1716 | 1020 | 1221 | 3957 |

| Narrow cases | 469 | 1020 | 702 | 2191 |

| Controls | 1792 | 16361 | 3428 | |

|

| ||||

| Males | ||||

| Broad cases | 524 | 298 | 506 | 1328 |

| Narrow cases | 113 | 298 | 276 | 687 |

| Controls | 681 | 9181 | 1599 | |

|

| ||||

| Females | ||||

| Broad cases | 1192 | 722 | 715 | 2629 |

| Narrow cases | 356 | 722 | 426 | 1504 |

| Controls | 1111 | 7181 | 1829 | |

|

| ||||

| Proportion of cases with the clinical features defining the Narrow phenotype | ||||

| Recurrent | 39.6% | 100% | 73.8% | |

| Onset < 31 | 59.1% | 100% | 69.0% | |

| Recurrent+Onset<31 | 27.3% | 100% | 57.9% | |

|

| ||||

| Genotyping platform | ||||

| Affy 5.0 | ||||

| Perlegen | Affy 6.0 | Affy 500K2 | ||

|

| ||||

| GenotypedSNPs (post-QC) | ||||

| Autosomal | 427,874 | 646,431 | 254,857 | |

| X | 6,438 | 22,546 | 5,617 | |

|

| ||||

| HapMap II SNPs in final meta-analysis | ||||

| Autosomal | 2,339,408 | |||

| X | 51,795 | |||

| Total | 2,391,203 | |||

Shown are the Ns for each sample in each analysis after all QC filtering. Slightly smaller samples were available for X chromosome analyses. See online Supplementary Methods for further details of QC procedures and exclusions. The GAIN-MDD sample sizes are slightly different than those in the published report64, because of the independent QC analyses, but association test results are quite similar. The HapMap II SNPs selected for association analyses had MAF > 1% and imputation r2>0.3 in all three datasets.

The same controls were used in the GenRED and STAR*D analyses (although with separate imputation procedures using the SNPs available for cases in each dataset), with statistical correction for this correlation in the meta-analyses. See online Supplementary Methods for details. Note that analyses in the companion article on STAR*D used a subset of these controls (see text).

Affymetrix 5.0 for 606 cases; Affymetrix 500K for 639 cases. Note that the Affymetrix 500K data for controls were not used in this meta-analysis.

SOFTWARE

Genotypic data were managed and analyzed using PLINK v1.04–1.06.24 STAR*D results were compiled and visualized with WGAViewer v1.25T-Z25 and HaploView v4.126. Quality control and association analyses were carried out with PLINK, except for imputation analyses and analysis of imputed data as described below and in Supplementary Methods.

GENOTYPING

STAR*D cases

Genotyping was conducted for 754 cases by Affymetrix, Inc., with the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 500K Array Set and genotypes called with the Bayesian Robust Linear Model with Mahalanobis distance classifier (BRLMM)27. We genotyped the remaining 746 cases with the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP 5.0 Array and called genotypes with the updated BRLMM-P algorithm. There were 500,568 SNPs that were assayed by both arrays.

GenRED cases and MGS controls were genotyped at the Broad Institute on the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP 6.0 Array, and genotypes were called with Birdseed version 2.4, 13 The GAIN-MDD sample was genotyped with the Perlegen platform.5

QUALITY CONTROL ANALYSES

SNPs

STAR*D

DNA samples were genotyped on three related platforms: cases on Affymetrix 500K and 5.0, and controls on Affymetrix 6.0, resulting in 382,598 SNPs that were assayed on all three platforms and that passed QC for the MGS/GenRED controls. To ensure consistency of results, we then excluded SNPs for all samples in the STAR*D analysis based on cross-platform data as follows:

(a) using data for 806 controls genotyped on Affy 6.0 and 500K28, 61,440 SNPs were excluded for which more than 1% of samples had discordant calls (>8 for autosomal SNPs, >7 for chromosome X);

(b) using 12 cases genotyped with Affy 500K and 5.0, 4,049 SNPs had one or more discordant calls and were excluded;

(c) we also examined data for 12 controls genotyped by us with Affy 5.0 and 6.0, but found no additional SNPs (not already excluded) with one or more discordancies.

SNPs were also excluded for deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in controls at a p < 1 × 10−6, SNP call rate <98% in either cases or controls, a 2% or greater difference in call rate between cases and controls, or minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.05. After all QC there were 260,474 SNPs available for analysis that captured an estimated 52.2% of common variation at an r2 threshold of 0.8 and 66.3% at a threshold of 0.5 (that better reflects the power of a GWAS29). Total genotyping rates in the final post-QC datasets were 99.8% and 99.9% for autosomal and X SNPs, respectively.

GenRED and GAIN-MDD

SNP QC for the GenRED sample is described in the companion paper4 and Supplementary Methods. We carried out new QC analyses of the GAIN MDD dataset (Supplementary Methods), to ensure consistency across the datasets and because final post-QC data were not available from dbGAP. We included 434,312 SNPs (vs. 435,291 in the published GWAS report5).

Cluster plots of genotype intensity data were visually examined for all top results discussed below for STAR*D or the meta-analysis, including genotyped SNPs or (for the meta-analysis) those critical for the imputation of ungenotyped SNPs that produced strong signals.

Table 2 summarizes the numbers of SNPs available for each dataset for meta-analysis.

INDIVIDUALS

STAR*D

Cases were initially evaluated with PLINK24 using a subset of approximately 85,000 SNPs. Pairwise estimates of identity-by-descent detected 3 unexpected duplicates and 21 cryptic relatives (estimated kinship ≥ 0.1); for each pair the sample with the lower call rate was excluded. Four additional cases were removed for unusual degrees of SNP heterozygosity. To evaluate ancestry differences, Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) vectors were computed and plotted, and 230 outliers to the main European-ancestry cluster were removed -- most self-identified Hispanics were excluded, but 24 had scores within the main European cluster and were retained. We also removed cases with ambiguous gender (N=20), or call rate < 97% (N=1 for autosomal and 11 for chromosome X analyses), leaving 1,221 cases for autosomal analyses and 1,211 for chromosome X. QC procedures for the 1,636 controls have been described in the companion paper4 and in Supplementary Methods; briefly, samples were excluded for genotyping call rate <97%; inconsistency between reported and genotypic gender; outlier values for mean heterozygosity across genotypes; outliers in the distributions of principle component scores for ancestry; outliers in the number of other subjects with which kinship was estimated at > 10%; and cryptic relatives (retaining the sample with the best call rate).

Meta-analysis

QC procedures for GenRED and GAIN-MDD (similar to methods described above for controls) are described in Supplementary Methods. For GAIN-MDD, we excluded slightly more ancestry outliers based on principal component scores. Genomic control λ values are shown in Table 3 for each analysis. QQ plots are shown in Tables S8–11.

Table 3.

Genomic control γ values for genotyped and imputed autosomal SNPs in the meta-analysis

| All cases (Broad) | Narrow cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M+F | M | F | M+F | M | F | |

| GAIN | 1.047 | 1.029 | 1.036 | 1.025 | 1.030 | 1.028 |

| GenRED | 1.034 | 1.007 | 1.022 | 1.034 | 1.007 | 1.022 |

| STAR*D | 1.023 | 1.025 | 1.029 | 1.021 | 1.009 | 1.030 |

| Combined | 1.046 | 0.996 | 1.036 | 1.029 | 0.998 | 1.023 |

F = females; M = males

Population substructure

To obtain consistent ancestry-informative covariates, we carried out a final principal components analysis (PCA)30 of all subjects, using the 82,361 autosomal SNPs common to the three datasets. Subjects who were outliers to the distributions of the two largest components were excluded (no additional STAR*D cases had to be excluded beyond those noted above), and the first ten PC scores were entered into the analyses as covariates to correct for population substructure.

IMPUTATION OF DATA FOR NON-GENOTYPED SNPS

For the meta-analysis, to create genotypic data for the same SNPs for all datasets, we imputed data for each sample for HapMap II SNPs that were not genotyped in that sample, using MACH 1.031 (autosomal SNPs) or IMPUTE32 (X chromosome). For each dataset, imputation was based on SNPs that passed QC for both cases and controls. MACH and IMPUTE are two of several available methods with similar accuracy.33 Using a Hidden Markov Model algorithm with phased CEU HapMap haplotypes as training data, a non-integer “allele dosage” is assigned to each individual for each SNP based on weighted probabilities of possible genotypes. For each SNP, an r2 value estimates concordance with actual genotypes (and thus the predicted concordance with the association tests they would produce). A low r2 predicts greater variance in the concordance of genotypes and of test statistics. This uncertainty is taken into account in the meta-analysis procedure. SNPs have been excluded from analysis if MAF was less than 1% in any dataset or if imputation r2 was less than 0.3. This threshold was used in four previous large meta-analyses because it removed most poorly-imputed SNPs but few well-imputed SNPs.34–37 The meta-analysis included 2,391,203 SNPs (2,339,408 autosomal and 51,795 X chromosome SNPs).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Analysis of genetic association

For each dataset, separate association analyses were carried out for Broad and Narrow phenotypes (all GenRED cases were Narrow) for all subjects and then for males and for females separately. The a priori primary analyses (for STAR*D and for the meta-analysis) considered the Broad phenotype for all subjects. For STAR*D, the primary analysis was limited to genotyped SNPs; for the meta-analysis it included genotyped plus imputed SNPs.

For each analysis, single-SNP tests were carried out for each dataset by logistic regression for genotyped and imputed SNPs. For discrete genotypes without covariates, logistic regression is asymptotically equivalent to a trend test for additive effects, while permitting covariates. We used custom software to implement the same logistic regression approach for imputed non-integer genotype “dosages.” Covariates included the first ten ancestry-informative PCs, plus an indicator for sex for X chromosome SNPs. Combined analysis (“mega-analysis”) of genotypes was not straightforward because of the overlapping STAR*D/GenRED controls, with different numbers of genotyped SNPs for the two case groups. We could have assigned unique subsets of controls to GenRED and STAR*D, but some power is lost when imputation information content is much lower in one sample (see Supplementary Methods). Therefore, we used a meta-analysis procedure as described in Supplementary Methods. Briefly, for each SNP, the procedure weights the Z-score for each dataset by the case and control sample sizes and imputation r2 values (r2=1 for genotyped SNPs), while correcting for the shared controls between STAR*D and GenRED. Combined odds ratios were obtained with a similar procedure. This method takes into account the direction of association in the datasets (i.e., which allele is associated), assuming that the same allele should be associated in samples with closely-related ancestries. This increases power compared with the classical procedure which ignores direction. For the primary analysis, P < 5 × 10−8 was considered the 5% genome-wide significance threshold.38–40

We also examined STAR*D and meta-analysis results for SNPs within 50 kb of forty-one previously-noted MDD candidate genes. For the meta-analysis, we used a permutation-based procedure to determine whether the distribution of P-values observed for these SNPs deviated from chance expectation (see Supplementary Methods for details)

Power Analyses

Power analysis methods are described on page S-19 and results shown in Tables S3 and S4 and Figure S13. Power was computed for a genome-wide significance threshold of P < 5 × 10−8 and additive inheritance. For the primary STAR*D analysis, there was 80% power to detect an allele with a genotypic relative risk (GRR) of 1.70, 1.50, and 1.43 for allele frequencies of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3; and for the primary meta-analysis, power was approximately 50% for an allele with GRRs of 1.19 or 1.16 for allele frequencies of 20% or 50%, and was approximately 80% with GRR of 1.20 and frequency of 30%.

DATA SHARING

Genotypic and clinical data are available to qualified scientists through controlled-access repository programs: the NIMH repository program (http://nimhgenetics.org) for the GenRED and STAR*D case samples; dbGAP for the MGS control sample and the GAIN-MDD sample.

Results

STAR*D

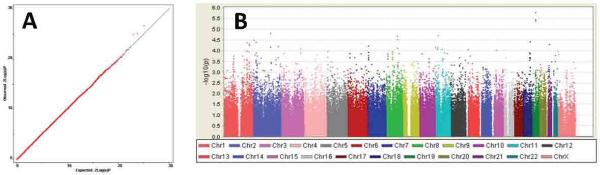

The distribution of P-values is similar to chance expectation (Figure 1), with a genomic control λ value of 1.022. Figure 1 also summarizes association findings by chromosomal location. The top 25 findings are listed in Table 4, and all results with P < 0.001 in any analysis are provided online in stard_supplementary_data.txt. There were no genome-wide significant findings. Our top finding (rs12462886, P = 1.73 × 10−6) is located in a gene desert in 19q12. Brain-expressed genes tagged by the top 100 SNPs include: LPHN2, SRD5A2, DYSF, RPRM, CCDC109B, CTNND2, MSR1, SLC18A1, ANKRD46, CSMD3, SLC5A12, MARK2, RCOR2, KCTD14, SYN3, NLGN4X and FGF13. None of the genes had strong signals in more than one linkage disequilibrium (LD) block, but in several instances there were clusters of SNPs with strong signals within an LD block, which is evidence against genotyping error. For sex-specific analyses, signals (among the top 100 for either sex) in genes of known neurobiological function or expressed in brain include: in males, SNPs in CTNND2, GRIA1, SLC18A1, PLEKHA7, ERBB2IP, KIFAP3, CLTCL1,THRB, and SYN3; and in females, SNPs in CSMD3, CACNA2D4, SV2B, and NRXN3.

Figure 1. Overview of STAR*D GWAS results for 260,474 SNPs.

(A) Q-Q plot of observed vs. expected -log (P-value). λ, the genomic inflation factor, is estimated at 1.022. (B) Manhattan plot of all results by chromosomal location.

Table 4.

STAR*D GWAS results

| Band | SNP | bp | A1 | A2 | frq | OR | P | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19q12 | rs12462886 | 33955530 | G | T | 0.40 | 0.76 | 1.73E-06 | |

| 11p14.2 | rs10835065 | 26729194 | T | C | 0.27 | 0.76 | 1.87E-05 | SLC5A12(−27645) |

| 8q22.2 | rs2844043 | 101557997 | C | A | 0.46 | 1.27 | 1.96E-05 | ANKRD46 (33984) |

| 8q22.3 | rs1786330 | 101761306 | T | C | 0.32 | 0.78 | 2.96E-05 | PABPC1 (23014) |

| 2p25.1 | rs7566637 | 10340390 | T | C | 0.16 | 1.35 | 3.20E-05 | HPCAL1 (−20101) |

| 18q22.1 | rs627419 | 64466738 | T | C | 0.15 | 1.35 | 3.85E-05 | TMX3 (25169) |

| 2p23.1 | rs13027103 | 31745075 | A | G | 0.11 | 0.68 | 3.98E-05 | SRD5A2 (−85531) |

| 1q32.1 | rs493474 | 197627600 | T | C | 0.34 | 1.26 | 4.13E-05 | AK125573 (intron) |

| 1q41 | rs12125058 | 219344131 | C | T | 0.43 | 0.80 | 4.65E-05 | HLX (219108) |

| 21q21.3 | rs2831649 | 28504218 | A | G | 0.26 | 0.77 | 5.01E-05 | C21orf94 (187075) |

| 7p21.3 | rs11764174 | 12563141 | T | C | 0.40 | 0.80 | 6.05E-05 | SCIN (−13729) |

| 2q35 | rs934036 | 218577633 | A | G | 0.26 | 0.77 | 6.23E-05 | RUFY4 (−30323) |

| 2q23.3 | rs1221754 | 154081012 | C | T | 0.27 | 0.77 | 6.84E-05 | RPRM (−37444) |

| 11p14.3 | rs4550218 | 22820234 | G | C | 0.35 | 1.26 | 7.10E-05 | SVIP (−12276) |

| 11p15.4 | rs7942744 | 6700466 | C | T | 0.45 | 0.80 | 7.14E-05 | GVIN1 (−3309) |

| 3q26.1 | rs1517057 | 167926707 | T | C | 0.38 | 1.25 | 8.10E-05 | |

| 11q13.1 | rs11231662 | 63495218 | G | T | 0.38 | 1.25 | 8.43E-05 | COX8A (−3437) |

| Xp22.32 | rs5916245 | 5671536 | C | T | 0.35 | 0.76 | 1.04E-04 | NLGN4X (146549) |

| 5p15.2 | rs27520 | 11271488 | C | T | 0.47 | 1.24 | 1.05E-04 | CTNND2 (intron) |

| 8q12.1 | rs7013994 | 58388614 | C | T | 0.18 | 1.30 | 1.10E-04 | C8orf71 (28772) |

| 7p21.2 | rs2116624 | 13371189 | A | G | 0.31 | 0.79 | 1.18E-04 | |

| 11q14.1 | rs7127866 | 82487248 | T | A | 0.25 | 0.78 | 1.22E-04 | RAB30 (−26716) |

| 18q21.33 | rs8099455 | 57412153 | A | G | 0.18 | 1.31 | 1.26E-04 | CDH20 (38808) |

| 6p22.3 | rs10946320 | 19569533 | C | T | 0.36 | 0.80 | 1.32E-04 | |

| 8q23.3 | rs7012271 | 114386848 | C | T | 0.29 | 1.26 | 1.33E-04 | CSMD3 (intron) |

Shown are the best 25 results of the STAR*D GWAS, ranked in order of P-value. For each region, the SNP with the lowest P-value is shown.

Abbreviations: SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism), bp (basepair position), A1 (minor allele & tested allele), frq (control minor allele frequency), OR (odds ratio), P (P-value). Distance is in base pairs.

Results for SNPs in 41 previous MDD candidate genes are shown in Table S7. The best finding was for rs3788477, a SNP intronic to SYN3 (p = 1.64 × 10−4). No other SNP in this analysis achieved P < 10−3.

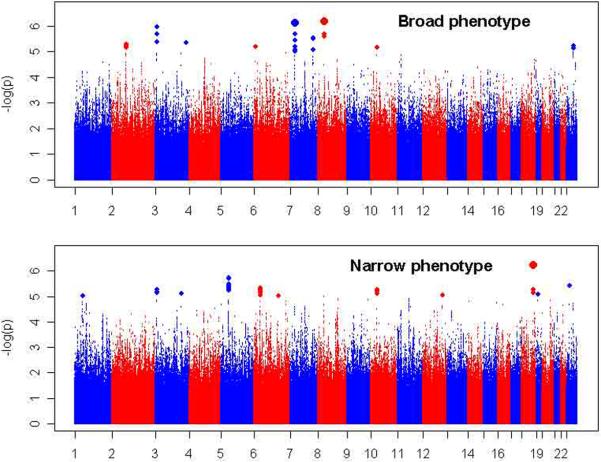

META-ANALYSIS

No genome-wide significant result was observed. Figure 2 illustrates results for all genotyped and imputed SNPs. Table 5 (Broad) and Table 6 (Narrow) summarize results for all regions with at least one SNP with P < 10−5. Results for SNPs with P < 10−3 in any analysis are provided in online files meta-analysis_broad_supplementary_data.txt and meta-analysis_narrow_supplementary_data.txt. The Annotation columns of Tables 5 and 6 provide information about the closest gene (within 250 kb) or other functional elements annotated in the UCSC browser (full gene names and summaries of known functions are provided in Supplementary Results). For all regions with no genes or elements listed, peaks of high homology with known regulatory sequences were detected by the ESPERR (evolutionary and sequence pattern extraction through reduced representations) method for estimating regulatory potential.41

Figure 2. Meta-analysis results.

Shown are association test results (-log10[P-values] on the Y-axis) for the meta-analyses of the GenRED, STAR*D and GAIN MDD datasets, for the Broad phenotype (primary analysis) and the Narrow phenotype (recurrent early-onset cases). The X-axis shows the start position of each chromosome. Plots for males and females separately are available in online Supplementary Figures S15 and S16.

Table 5.

Strongest meta-analysis findings for Broad phenotype (All, Male or Female subjects)

| R2 | --GAIN-MDD-- | --GenRED-- | --STAR*D-- | Meta-analysis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | SNP | BP | A1/ A2 |

All Frq |

GAIN | GR | SD | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | Annotation |

| ALL-BROAD | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 8p21.3 | rs1106634 | 20110329 | A/G | 0.12 | 0.703 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 1.270 | 3.93E-03 | 1.270 | 5.39E-03 | 1.346 | 8.18E-05 | 1.295 | 6.78E-07 | ATP6V1B2; SLC18A1 (up); LZTS1 (dwn) |

| 7p15.3 | rs17144465 | 21470952 | A/G | 0.04 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.457 | 1.440 | 4.82E-03 | 1.820 | 5.97E-06 | 1.325 | 1.47E-01 | 1.561 | 7.68E-07 | SP4 |

| 3p26.1 | rs9870680 | 7504555 | C/T | 0.43 | 0.847 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.230 | 1.23E-04 | 1.220 | 4.76E-04 | 1.104 | 6.89E-02 | 1.188 | 1.11E-06 | GRM7 |

| 7q32.3 | rs10265216 | 130550661 | A/T | 0.29 | 1.000 | 0.993 | 0.798 | 1.230 | 7.64E-05 | 1.140 | 3.12E-02 | 1.161 | 2.32E-02 | 1.190 | 3.02E-06 | mRNA AK294384 (amygdala) |

| 3q26.32 | rs644695 | 178774391 | A/G | 0.87 | 0.739 | 0.665 | 0.557 | 1.610 | 3.06E-07 | 1.260 | 3.20E-02 | 0.998 | 9.85E-01 | 1.354 | 4.46E-06 | |

| 2p14 | rs724568 | 67795984 | A/C | 0.36 | 0.997 | 1.000 | 0.992 | 1.200 | 2.58E-04 | 1.090 | 1.51E-01 | 1.191 | 1.68E-03 | 1.171 | 5.32E-06 | mRNA BC043421 (hypothalamus) (dwn) |

| Xq21.33 | rs5990417 | 94966526 | T/C | 0.82 | 0.940 | 0.870 | 0.550 | 1.200 | 2.90E-03 | 1.250 | 3.70E-03 | 1.266 | 5.27E-03 | 1.230 | 6.11E-06 | |

| 6p25.1 | rs2326810 | 6557466 | C/G | 0.92 | 0.930 | 0.863 | 0.754 | 1.210 | 7.29E-02 | 1.480 | 1.84E-03 | 1.751 | 1.07E-05 | 1.411 | 6.52E-06 | LY86,within |

| 10p11.23 | rs1612122 | 29331904 | A/T | 0.48 | 0.959 | 0.953 | 0.923 | 1.150 | 4.51E-03 | 1.200 | 2.38E-03 | 1.177 | 4.34E-03 | 1.169 | 6.98E-06 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| MALES-BROAD | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 11p15.1 | rs435206 | 16859754 | A/C | 0.13 | 0.994 | 0.998 | 0.987 | 1.460 | 1.68E-03 | 1.580 | 6.70E-04 | 1.353 | 6.72E-03 | 1.444 | 1.23E-06 | PLEKHA7,within |

| 6p23 | rs12526133 | 14390002 | C/T | 0.54 | 0.954 | 0.971 | 0.803 | 1.330 | 8.80E-04 | 1.225 | 4.07E-02 | 1.355 | 7.75E-04 | 1.311 | 1.88E-06 | |

| 10q11.21 | rs10900126 | 44706328 | G/T | 0.54 | 0.999 | 0.977 | 0.619 | 1.200 | 2.75E-02 | 1.370 | 1.80E-03 | 1.522 | 5.23E-05 | 1.321 | 2.20E-06 | KSP37 (up) |

| 2q24.1 | rs10187367 | 155029880 | A/G | 0.03 | 0.990 | 0.993 | 0.804 | 1.260 | 1.93E-02 | 2.260 | 2.92E-04 | 1.884 | 3.68E-03 | 1.635 | 5.42E-06 | GALNT13 (dwn) |

| 11q25 | rs329640 | 133326341 | A/G | 0.41 | 0.826 | 0.847 | 0.716 | 1.310 | 3.38E-03 | 1.240 | 4.18E-02 | 1.380 | 7.37E-04 | 1.314 | 6.49E-06 | IGSF9B |

| 12q23.3 | rs7978310 | 103272750 | A/G | 0.05 | 0.832 | 0.869 | 0.776 | 1.360 | 8.53E-02 | 1.870 | 2.05E-03 | 2.057 | 8.66E-05 | 1.704 | 6.84E-06 | TXNRD1 (dwn); EID3 (dwn) |

| 4q22.3 | rs7654559 | 97529818 | C/T | 0.25 | 0.969 | 0.966 | 0.959 | 1.260 | 1.39E-02 | 1.340 | 7.27E-03 | 1.349 | 8.40E-04 | 1.309 | 7.55E-06 | |

| 9q22.32 | rs2147256 | 97966948 | C/T | 0.37 | 0.993 | 0.792 | 0.786 | 1.247 | 8.53E-03 | 1.298 | 1.91E-02 | 1.367 | 7.86E-04 | 1.296 | 9.10E-06 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| FEMALES-BROAD | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 3q26.32 | rs644695 | 178774391 | A/G | 0.86 | 0.739 | 0.665 | 0.557 | 1.810 | 3.23E-07 | 1.390 | 1.80E-02 | 1.374 | 4.30E-02 | 1.612 | 3.18E-08 | |

| 7p15.3 | rs17144465 | 21470952 | A/G | 0.03 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.457 | 1.540 | 7.17E-03 | 2.110 | 4.44E-05 | 1.457 | 1.69E-01 | 1.731 | 4.54E-06 | SP4 |

| 20p13 | rs867722 | 4000298 | A/G | 0.03 | 0.827 | 0.809 | 0.648 | 1.970 | 4.92E-05 | 1.760 | 1.14E-02 | 1.324 | 3.42E-01 | 1.821 | 4.89E-06 | |

| 7p21.2 | rs11772451 | 15073019 | C/G | 0.21 | 0.911 | 0.972 | 0.862 | 1.260 | 1.93E-03 | 1.360 | 9.14E-04 | 1.259 | 1.72E-02 | 1.284 | 5.70E-06 | |

| 14q32.12 | rs7151193 | 92681288 | G/T | 0.67 | 0.960 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.200 | 5.16E-03 | 1.280 | 2.46E-03 | 1.295 | 9.91 E-04 | 1.240 | 5.85E-06 | ITPK1 (up); MOAP1 (dwn); C14orf109 (up) |

| 10p12.32 | rs11011581 | 20140825 | C/T | 0.04 | 0.966 | 1.000 | 0.950 | 1.480 | 1.86E-03 | 1.660 | 1.27E-03 | 1.518 | 1.47E-02 | 1.530 | 6.19E-06 | PLXDC2 (dwn) |

| 16q21 | rs4620978 | 60750205 | A/C | 0.51 | 0.951 | 0.891 | 0.785 | 1.130 | 4.61 E-02 | 1.340 | 2.72E-04 | 1.474 | 9.19E-06 | 1.236 | 6.44E-06 | |

| 2q22.1 | rs6711718 | 137123482 | C/T | 0.39 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.749 | 1.210 | 1.27E-03 | 1.200 | 7.23E-03 | 1.276 | 6.05E-03 | 1.218 | 7.80E-06 | |

For each region with at least one P < 10−5, the SNP with the lowest P-value is shown. Note that only the best SNP in each region is shown; data for all SNPs with P > 0.001 for each meta-analysis (Broad and Narrow; All, Males, Females) are provided in online files (see text).

For findings listed for Males or Females, P-values at the same SNP in the other gender were > 0.05. Genes are listed if P < 10−5 was observed within the gene, 50 kb upstream (up) or downstream (dwn); or otherwise within 200 kb upstream as noted. All listed genic SNPs are intronic except for PLEKHA7 SNPs at intron-exon boundaries. Nongenic regions all contained peaks of bioinformatically predicted high homology to known regulatory sequences.41

A1/A2=Alleles 1 and 2. Bold font indicates the allele associated with increased risk of MDD.

GAIN=GAIN-MDD; GR=GenRED; SD=STAR*D.

OR=Odds Ratio for the risk allele (OR>1) as indicated under A1A/2.

FRQ=HapMap CEU frequency of the tested allele (this was always very similar to the frequency in GenRED/STAR*D controls, and similar to GAIN-MDD control frequencies). (Case and control allele frequencies for each sample are shown in online Table S12.)

R2 is the value predicted (by MACH 1.0) for the squared correlation between imputed and actual genotypes (R2 = 1 for genotyped SNPs). Lower values predict greater variance between imputed and actual P-values, and thus lower confidence in the P-value.

Table 6.

Strongest meta-analysis findings for Narrow phenotype (All, Male or Female subjects)

| R2 | --GAIN-MDD-- | --GenRED-- | --STAR*D-- | Meta-analysis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | SNP | BP | A1/ A2 |

All Frq |

GAIN | GR | SD | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | OR | P | Annotation |

| ALL-NARROW | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 18q22.1 | rs17077540 | 63436259 | A/G | 0.110 | 0.331 | 0.859 | 0.649 | 1.250 | 2.93E-01 | 1.610 | 1.83E-07 | 1.302 | 3.94E-02 | 1.481 | 6.04E-07 | mRNA BC053410 (LOC643542);DSEL (up) |

| 5p13.2 | rs270592 | 38102343 | A/G | 0.570 | 0.996 | 0.989 | 0.991 | 1.170 | 3.62E-02 | 1.320 | 2.49E-06 | 1.150 | 3.56E-02 | 1.223 | 1.88E-06 | GDNF (220kb up) |

| Xp21.1 | rs2405829 | 32364267 | A/G | 0.540 | 0.960 | 0.960 | 0.960 | 1.280 | 5.50E-04 | 1.130 | 1.87E-02 | 1.190 | 2.10E-03 | 1.180 | 3.84E-06 | DMD |

| 6p22.1 | rs6930508 | 27161121 | C/T | 0.560 | 0.988 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1.240 | 5.41 E-03 | 1.180 | 4.19E-03 | 1.231 | 1.55E-03 | 1.213 | 4.73E-06 | histone 2/4 gene cluster; GUSBL1 (up,noncoding) |

| 10p11.23 | rs1612122 | 29331904 | A/T | 0.480 | 0.959 | 0.953 | 0.923 | 1.280 | 1.48E-03 | 1.200 | 2.38E-03 | 1.176 | 1.78E-02 | 1.218 | 5.39E-06 | |

| 3p26.1 | rs9870680 | 7504555 | C/T | 0.433 | 0.847 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.287 | 1.97E-03 | 1.220 | 4.76E-04 | 1.134 | 5.13E-02 | 1.211 | 5.56E-06 | GRM7 |

| 3q25.1 | rs1456139 | 152123994 | A/G | 0.610 | 0.999 | 0.845 | 0.839 | 1.180 | 1.99E-02 | 1.240 | 9.11E-04 | 1.242 | 3.40E-03 | 1.219 | 7.92E-06 | CLRN1 (dwn) |

| CRLF1; up:C19orf50,UBA52,C19orf60; | ||||||||||||||||

| 19p13.11 | rs7249956 | 18576203 | A/C | 0.770 | 0.893 | 0.898 | 0.732 | 1.270 | 1.41E-02 | 1.260 | 1.69E-03 | 1.316 | 2.77E-03 | 1.277 | 8.11E-06 | dwn:TMEM59L,KLHL26 |

| 12q23.3 | rs1895943 | 106764962 | A/C | 0.040 | 0.989 | 1.000 | 0.803 | 1.350 | 6.85E-02 | 1.600 | 1.67E-04 | 1.602 | 4.03E-03 | 1.519 | 8.70E-06 | CpG island at 106.76 Mb; PRDM4 (85kb up) |

| 6q22.1 | rs1855625 | 114535864 | G/T | 0.684 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.110 | 2.00E-01 | 1.283 | 9.00E-05 | 1.279 | 7.64E-04 | 1.226 | 9.34E-06 | HS3ST5,−45130 |

| 1p32.2 | rs6694643 | 57121995 | A/T | 0.120 | 0.990 | 1.000 | 0.885 | 1.510 | 7.88E-05 | 1.210 | 1.16E-02 | 1.189 | 8.94E-02 | 1.294 | 9.50E-06 | C8A,within; C8B,45475 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| MALES-NARROW | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 3p14.1 | rs11710109 | 66836364 | C/T | 0.380 | 0.990 | 0.991 | 0.843 | 1.580 | 2.46E-03 | 1.500 | 6.06E-05 | 1.397 | 2.70E-03 | 1.483 | 6.54E-08 | |

| 11p15.1 | rs389967 | 16831186 | A/G | 0.100 | 0.947 | 1.000 | 0.975 | 1.470 | 8.23E-02 | 1.710 | 2.33E-04 | 1.761 | 1.64E-04 | 1.675 | 5.75E-07 | PLEKHA7,within |

| 4q23 | rs10007831 | 99911315 | C/T | 0.520 | 0.977 | 0.984 | 0.684 | 1.600 | 1.75E-03 | 1.340 | 3.39E-03 | 1.493 | 1.13E-03 | 1.441 | 9.64E-07 | |

| 10q11.21 | rs7079573 | 44720412 | A/G | 0.540 | 0.920 | 0.882 | 0.624 | 1.430 | 2.46E-02 | 1.380 | 2.42E-03 | 1.473 | 2.58E-03 | 1.418 | 9.53E-06 | KSP37,−6357 check dir |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| FEMALES-NARROW | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 5p13.2 | rs270584 | 38110611 | A/C | 0.560 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.200 | 3.47E-02 | 1.390 | 1.64E-05 | 1.421 | 1.53E-04 | 1.321 | 3.71E-07 | GDNF (230kb up) |

| 2q22.1 | rs6711718 | 137123482 | C/T | 0.390 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.749 | 1.400 | 1.14E-04 | 1.200 | 7.23E-03 | 1.295 | 1.33E-02 | 1.293 | 1.71E-06 | |

| 6q25.2 | rs644377 | 153260377 | A/T | 0.420 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.280 | 5.08E-03 | 1.330 | 1.44E-04 | 1.256 | 1.13E-02 | 1.294 | 1.91E-06 | |

| 4q28.1 | rs2203374 | 128653784 | C/G | 0.790 | 0.801 | 0.814 | 0.770 | 1.390 | 1.36E-02 | 1.560 | 5.91E-05 | 1.400 | 1.20E-02 | 1.461 | 2.71E-06 | INTU (120kb up) |

| 12q14.1 | rs7977950 | 60513443 | C/T | 0.120 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.991 | 1.230 | 9.52E-02 | 1.400 | 1.30E-03 | 1.824 | 1.01E-06 | 1.421 | 3.40E-06 | FAM19A2,within |

| 11q13.4 | rs17133921 | 74712634 | A/G | 0.060 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.550 | 3.77E-03 | 1.550 | 3.47E-03 | 1.643 | 1.96E-03 | 1.571 | 5.29E-06 | ARRB1,within |

| 15q25.3 | rs11634319 | 84224912 | C/T | 0.760 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.829 | 1.450 | 1.94E-03 | 1.340 | 1.98E-03 | 1.353 | 1.40E-02 | 1.385 | 5.67E-06 | KLHL25 (86kb up) |

| 4q34.3 | rs346101 | 179841206 | A/G | 0.510 | 0.991 | 0.989 | 0.886 | 1.330 | 1.56E-03 | 1.160 | 5.59E-02 | 1.508 | 1.70E-05 | 1.289 | 6.01E-06 | |

There are annotated reports of copy number variants (CNVs) in some of these regions, but none were detected in a survey of HapMap data42, and Birdsuite42 (Birdseye module) CNV analysis of the GenRED dataset showed that no SNP listed in Tables 5 and 6 was spanned by a CNV in more than a few subjects.

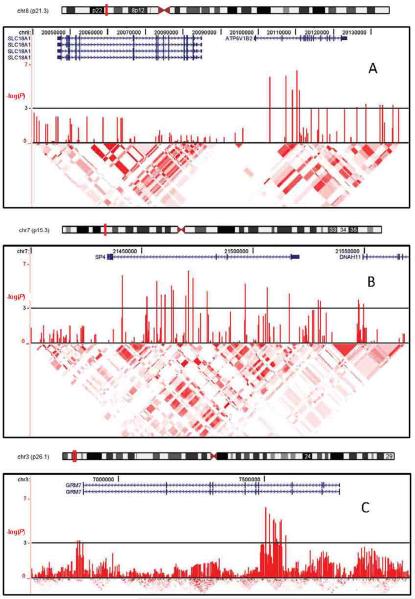

Figure 3 illustrates annotation information and P-values for all SNPs in the three best-supported gene-containing regions (8p21.2/ATP6V1B2, 3p26.1/GRM7 and 7p15.3/SP4).

Figure 3. Best-supported regions in the meta-analysis.

Shown are plots of association test results (males+females unless noted otherwise) for the three gene-containing regions with the lowest P-values in the primary (Broad) meta-analysis (see Table 5): ATP6V1B2 (Panel A), SP4 (B), GRM7 (C). Shown in each panel from top to bottom are: an ideogram of the chromosome with the plotted area marked in red; locations in base pairs; RefSeq genes with arrows representing direction of transcription; association test results as the -log10 of the P-value for each genotyped and imputed SNP; and color-coded marker-marker linkage disequiibrium results for phased HapMap II CEU genotypes (UCSC browser). Similar plots for additional top findings are available as online Supplementary Figures.

Results of the analyses of SNPs in or near forty-one MDD candidate genes are summarized in Table S8 and online file candidate_gene_results.xls. The aggregate analysis did not support the hypothesis of an excess of low P-values among these SNPs.

Discussion

The GWAS of STAR*D for the MDD phenotype (1,221 cases and 1,636 controls) did not produce genome-wide significant findings. Several regions with modest levels of significance in STAR*D were more strongly supported in the meta-analysis, including SLC18A1, ATP6V1B2 and PLEKHA7 for the Broad phenotype and SYN3 for the Narrow phenotype. Because genotypes were assayed on three different platforms, stringent QC measures were required to avoid spurious findings. The very low genomic control inflation factor (λ) suggests that these measures succeeded, but they also reduced the number of SNPs (260,474) available for analysis.

In the meta-analysis of 3,957 cases (2,191 with a narrow phenotype) and 3,428 controls, genome-wide significant evidence for association to MDD was not observed for 2,391,203 genotyped or imputed HapMap II SNPs, suggesting that if any common SNPs are associated with MDD, their individual genotypic relative risks (GRRs) are likely to be small. Such associations could be detected in future, larger GWAS meta-analyses, a strategy that has succeeded for dozens of other common diseases.43, 44 In samples of one or a few thousand cases, many such loci will produce unimpressive results, but the regions with the strongest evidence for association are statistically most likely to be true associations. We discuss here the three genes in which P-values of approximately P < 10−6 were observed in the primary meta-analysis: ATP6V1B2, SP4 and GRM7.

ATP6V1B2 encodes a subunit for a vacuolar proton pump ATPase. H+-ATPases consist of three A, three B and two G domains. In a bipolar disorder GWAS28, a P-value of 3.32 × 10−5 was observed in ATP6V1G1, encoding the G subunit of the same cytosolic V1 domain to which ATP6V1B2 contributes and which forms a complex with the transmembrane V0 domain for organelle acidification, critical to some forms of receptor-mediated endocytosis and generation of proton gradients across synaptic vesicle membranes. Modest association to bipolar disorder was also reported in an adjacent gene, SLC18A1 (previously VMAT1), which transports monoamines into synaptic vesicles45. Our signal lies in a distinct LD block within ATP6V1B2, but SLC18A1 could conceivably have regulatory sequences in this upstream region.

SP4 encodes the brain-specific Sp4 zinc finger transcription factor.46 In several small samples, modest association to bipolar disorder was observed for SNPs in an Sp4 binding site in the promoter of ADRBK2 (beta adrenergic receptor kinase 2; previously GRK3, G-protein receptor kinase 3)47 as well as in SP4 itself.48 SP4 mutant mice showed decreased granule cell density in the hippocampal dentate gyrus49, deficits in sensorimotor gating and contextual learning50, and infertility in surviving male knockout mice despite histologically intact testes and mature sperm, suggesting a possible behavioral deficit51. In our data, association is observed primarily in females; it may be noteworthy that Sp4 forms gene-regulating complexes with estrogen receptors.52 Sp4 may also play a role in glutamate-induced neurotoxicity.53, 54

GRM7 encodes metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 (mGluR7), which may be involved in mood regulation55, 56. Chronic treatment with mood stabilizers (lithium or valproate) decreased a hippocampal micro-RNA, increasing GRM7 expression.57 An mGluR7 agonist (AMN082) had antidepressant-like effects in mice that were blocked by knockout of GRM758, and chronic antidepressant treatment with citalopram in rodents decreased mGluR7 immunoreactivity in hippocampus and frontal cortex59. This is the third GWAS to report evidence of association to mood disorders in this long gene (880 kb). Our lowest P-value (7.11 × 10−7) was at 7.5 Mb (3p26.1), with P-values less than 10−4 extending to 7.56 Mb. In the German/Swiss recurrent MDD GWAS16, the lowest P-value (0.0001) was at 7.68 Mb, with P-values around 0.01 overlapping our signals. In the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium bipolar disorder GWAS60, the best P-value in GRM7 (0.0001 in a genotypic analyses) was at 7.63 Mb. Larger samples will be required to determine the significance of these findings, but the biological evidence suggests that GRM7 merits further investigation.

The most strongly-associated non-genic regions contain multiple peaks of high regulatory potential, but no known regulatory elements. Strong associations in non-genic regions should not be ignored; for example, several cancers are strongly associated with non-genic SNPs on chromosome 8q2461, whose functional relevance is now under intensive study. In secondary analyses, very low P-values were observed in non-genic regions (3q26.32 in females, Broad phenotype, P = 3.85 × 10−8; 3p14.1 in males, Narrow phenotype, P = 3.81 × 10−8. These values are not significant after accounting for multiple testing, and on 3q26.32 there is no support from other SNPs in the region (Figure S16).

For the Narrow (recurrent early-onset) phenotype, the strongest signal was in chromosome 18q22.1. The SNP with the lowest P-value had low imputation r2 values, but two other nearby SNPs had P-values less than 10−5. This region has previously been of interest in linkage studies of both bipolar disorder and MDD (see discussion in the companion paper4), and given that support for this region varied widely across our three samples, one might wonder whether they differed with respect to bipolar features, but we lacked the relevant data to compare the datasets. GenRED provided the strongest support and also had the most specific procedures to exclude bipolar disorder in probands and relatives, although the severe, recurrent, early-onset phenotype more closely resembles bipolar disorder. The next strongest signals were in a non-genic region of 5p13.2, 220kb upstream of GDNF; and in a cluster of histone genes on 6p22.1, in the same region where significant association to schizophrenia was recently observed.12–14 The latter finding was detected in a meta-analysis that included MGS, using a superset of the GenRED/STAR*D controls. However, MGS contributed very little of the statistical support for 6p22.1 association to schizophrenia.

Our meta-analysis findings were generally not more strongly supported by the Narrow analysis, but that sample was also smaller (55% of cases). Narrow cases provided most of the support for such signals in the Broad analysis as ATP6V1B2, GRM7, SP4, PLEKHA7, ITPK1/C14orf109 and regions 10p11.23, 10q11.21, 6p23 and 2q22.1 (Tables 5 and 6 and Supplementary Files). Larger samples of cases with this phenotype might prove useful.

Several candidate genes were supported primarily in one gender such as SP4 (females) and PLEKHA7 (males). PLEKHA7, which encodes a poorly-understood gene (pleckstrin homology domain containing, family A member 7), is associated with systolic blood pressure.62 Sex differences are likely to exist for genetic effects in MDD.

The strongest signal in the published GAIN-MDD GWAS was in PCLO (P = 7.7 × 10−7)5, encoding Piccolo, a protein involved in cycling of synaptic vesicles including at monoaminergic synapses. The association was supported in only one of five follow-up datasets (that totaled 6,079 cases and 5,893 controls), and it (like GAIN-MDD) was population-based, suggesting possible phenotypic heterogeneity. P-values in PCLO were less significant in our meta-analyses (~10−5) than in GAIN-MDD alone. Recurrent early-onset cases provided most of the evidence for association in GAIN-MDD, but the lowest P-value in the GenRED sample was 0.017. We have no independent data to test whether association is stronger in population-based samples.

In conclusion, a meta-analysis of three GWAS datasets did not detect genome-wide significant evidence for association to MDD. Of the best-supported genes and regions, GRM7 has the greatest previous biological support for involvement in processes such as mediation of response to antidepressant and antimanic drugs. It is likely that much larger samples will be required to clarify the role of common SNPs in genetic susceptibility to MDD. We are participating in the efforts of the Psychiatric GWAS Consortium44, 63 to carry out meta-analyses incorporating additional samples. Given the moderate heritability and clinical heterogeneity of MDD, larger samples with careful phenotypic characterization would be useful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The STAR*D GWAS study wishes to acknowledge Shaun Purcell (Broad Institute) for technical assistance and Eric Jorgenson (UCSF) for helpful discussion. Genotyping of STAR*D was supported by an NIMH grant to SPH (MH072802), and made possible by the laboratory of Pui Kwok (UCSF) and the UCSF Institute for Human Genetics. This work was further supported by NIMH training funds to SIS (R25 MH060482 & T32 MH19126) and to HAG (F32 MH082562 & T32 MH19552); a NARSAD Young Investigators Award to HAG (A109584); the State of New York, which provided partial support to PJM for this work. The authors appreciate the efforts of the STAR*D Investigator Team for acquiring, compiling, and sharing the STAR*D clinical dataset. STAR*D was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health via a contract (N01MH90003) to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (A. John Rush, principal investigator). The authors thank Stephen Wisniewski, Ph.D., Director, STAR*D Data Coordinating Center, University of Pittsburgh, for demographic data.

The GenRED project is supported by grants from NIMH (see online Supplementary Acknowledgements). We acknowledge the contributions of Dr. George S. Zubenko and Dr. Wendy N. Zubenko, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, to the GenRED I project. The NIMH Cell Repository at Rutgers University and the NIMH Center for Collaborative Genetic Studies on Mental Disorders made essential contributions to this project. Genotyping was carried out by the Broad Institute Center for Genotyping and Analysis with support from grant U54 RR020278 (which partially subsidized the genotyping of the GenRED cases) from the National Center for Research Resources.

The meta-analysis was supported by grants from NIMH and the National Cancer Institute, and by support from the State of New York.

GWAS data for the GAIN MDD dataset were accessed by D.F.L. through the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN), through dbGaP accession number phs000020.v1.p1 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000020.v2.p1); samples and associated phenotype data for Major Depression: Stage 1 Genome-wide Association in Population-Based Samples were provided by P. Sullivan.

Data for Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia (MGS) control subjects was used here by permission of the MGS project. Collection and quality control analyses of the control dataset were supported by grants from NIMH and the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. Genotyping of the controls was supported by grants from NIMH and by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN) (http://www.fnih.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=338&Itemid=454). Control data are available through dbGAP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap). We are grateful to Knowledge Networks, Inc. (Menlo Park, CA) for assistance in collecting the control dataset.

The authors express their profound appreciation to the families who participated in this project, and to the many clinicians who facilitated the referral of participants to the study.

(Additional information is available in online Supplementary Acknowledgements.)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020; summary. Published by the Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank; Distributed by Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Mass.: 1996. p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belmaker RH, Agam G. Major depressive disorder. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jan 3;358(1):55–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 Oct;157(10):1552–1562. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi J, Potash JB, Knowles JA, Weissman MM, Coryell W, Scheftner WA, et al. Genomewide association study of recurrent early-onset major depressive disorder. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.124. (submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan PF, de Geus EJ, Willemsen G, James MR, Smit JH, Zandbelt T, et al. Genome-wide association for major depressive disorder: a possible role for the presynaptic protein piccolo. Mol Psychiatry. 2009 Apr;14(4):359–375. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mailman MD, Feolo M, Jin Y, Kimura M, Tryka K, Bagoutdinov R, et al. The NCBI dbGaP database of genotypes and phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2007 Oct;39(10):1181–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fava M, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Sackeim HA, et al. Background and rationale for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) study. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003 Jun;26(2):457–494. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rush AJ, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, Lavori PW, Trivedi MH, Sackeim HA, et al. Sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D): rationale and design. Control Clin Trials. 2004 Feb;25(1):119–142. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders AR, Duan J, Levinson DF, Shi J, He D, Hou C, et al. No significant association of 14 candidate genes with schizophrenia in a large European ancestry sample: implications for psychiatric genetics. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Apr;165(4):497–506. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Coordinating Committee. Cichon S, Craddock N, Daly M, Faraone SV, Gejman PV, et al. Genomewide association studies: history, rationale, and prospects for psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2009 May;166(5):540–556. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08091354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira MAR, O'Donovan MC, Meng YA, Jones IR, Ruderfer DM, Jones L, et al. Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nature genetics. 2008 Sep;40(9):1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/ng.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O'Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009 Jul 1; doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, Sanders AR, Zheng Y, Pe'er I, et al. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2009 Jul 1; doi: 10.1038/nature08192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Rujescu D, et al. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2009 Jul 1; doi: 10.1038/nature08186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang K, Zhang H, Ma D, Bucan M, Glessner JT, Abrahams BS, et al. Common genetic variants on 5p14.1 associate with autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2009 May 28;459(7246):528–533. doi: 10.1038/nature07999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muglia P, Tozzi F, Galwey NW, Francks C, Upmanyu R, Kong XQ, et al. Genome-wide association study of recurrent major depressive disorder in two European case-control cohorts. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.131. 12/23/online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun TB, Wittchen H-U. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7(4):171–185. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aalto-Setala T, Haarasilta L, Marttunen M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Poikolainen K, Aro H, et al. Major depressive episode among young adults: CIDI-SF versus SCAN consensus diagnoses. Psychol Med. 2002 Oct;32(7):1309–1314. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurnberger JI, Jr., Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, et al. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 Nov;51(11):849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. Clinical indices of familial depression in the Swedish Twin Registry. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007 Mar;115(3):214–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levinson DF, Zubenko GS, Crowe RR, DePaulo RJ, Scheftner WS, Weissman MM, et al. Genetics of recurrent early-onset depression (GenRED) Am J Med Genet B NeuropsychiatrGenet. 2003 May 15;119(1):118–130. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Neale MC, Prescott CA. Genetic risk factors for major depression in men and women: similar or different heritabilities and same or partly distinct genes? PsycholMed. 2001 May;31(4):605–616. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. A Swedish National Twin Study of Lifetime Major Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006 Jan 01;163(1):109–114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007 Sep;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ge D, Zhang K, Need AC, Martin O, Fellay J, Urban TJ, et al. WGAViewer: software for genomic annotation of whole genome association studies. Genome Res. 2008 Apr;18(4):640–643. doi: 10.1101/gr.071571.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005 Jan 15;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabbee N, Speed TP. A genotype calling algorithm for affymetrix SNP arrays. Bioinformatics. 2006 Jan 1;22(1):7–12. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sklar P, Smoller JW, Fan J, Ferreira MA, Perlis RH, Chambert K, et al. Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 Jun;13(6):558–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jorgenson E, Witte JS. A gene-centric approach to genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2006 Nov;7(11):885–891. doi: 10.1038/nrg1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006 Aug;38(8):904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang L, Li Y, Singleton AB, Hardy JA, Abecasis G, Rosenberg NA, et al. Genotype-imputation accuracy across worldwide human populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2009 Feb;84(2):235–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007 Jul;39(7):906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nothnagel M, Ellinghaus D, Schreiber S, Krawczak M, Franke A. A comprehensive evaluation of SNP genotype imputation. Hum Genet. 2009 Mar;125(2):163–171. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, Schadt EE, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nature genetics. 2009 Jan;41(1):56–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott LJ, Mohlke KL, Bonnycastle LL, Willer CJ, Li Y, Duren WL, et al. A genome-wide association study of type 2 diabetes in Finns detects multiple susceptibility variants. Science (New York, NY. 2007 Jun 1;316(5829):1341–1345. doi: 10.1126/science.1142382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, Scuteri A, Bonnycastle LL, Clarke R, et al. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nature genetics. 2008 Feb;40(2):161–169. doi: 10.1038/ng.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willer CJ, Speliotes EK, Loos RJ, Li S, Lindgren CM, Heid IM, et al. Six new loci associated with body mass index highlight a neuronal influence on body weight regulation. Nature genetics. 2009 Jan;41(1):25–34. doi: 10.1038/ng.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dudbridge F, Gusnanto A. Estimation of significance thresholds for genomewide association scans. Genet Epidemiol. 2008 Apr;32(3):227–234. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoggart CJ, Clark TG, De Iorio M, Whittaker JC, Balding DJ. Genome-wide significance for dense SNP and resequencing data. Genet Epidemiol. 2008 Feb;32(2):179–185. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pe'er I, Yelensky R, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol. 2008 May;32(4):381–385. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor J, Tyekucheva S, King DC, Hardison RC, Miller W, Chiaromonte F. ESPERR: Learning strong and weak signals in genomic sequence alignments to identify functional elements. Genome Res. 2006 Dec;16(12):1596–1604. doi: 10.1101/gr.4537706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCarroll SA, Kuruvilla FG, Korn JM, Cawley S, Nemesh J, Wysoker A, et al. Integrated detection and population-genetic analysis of SNPs and copy number variation. Nat Genet. 2008 Oct;40(10):1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ng.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manolio TA, Brooks LD, Collins FS. A HapMap harvest of insights into the genetics of common disease. J Clin Invest. 2008 May;118(5):1590–1605. doi: 10.1172/JCI34772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Coordinating Committee. Cichon S, Craddock N, Daly M, Faraone SV, Gejman PV, et al. Genomewide Association Studies: History, Rationale, and Prospects for Psychiatric Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(5):540–556. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08091354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lohoff FW, Dahl JP, Ferraro TN, Arnold SE, Gallinat J, Sander T, et al. Variations in the vesicular monoamine transporter 1 gene (VMAT1/SLC18A1) are associated with bipolar i disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006 Dec;31(12):2739–2747. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suske G. The Sp-family of transcription factors. Gene. 1999 Oct 01;238(2):291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou X, Barrett TB, Kelsoe JR. Promoter variant in the GRK3 gene associated with bipolar disorder alters gene expression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008 Jul 15;64(2):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou X, Tang W, Greenwood TA, Guo S, He L, Geyer MA, et al. Transcription factor SP4 is a susceptibility gene for bipolar disorder. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(4):e5196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou X, Qyang Y, Kelsoe JR, Masliah E, Geyer MA. Impaired postnatal development of hippocampal dentate gyrus in Sp4 null mutant mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2007 Apr;6(3):269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou X, Long JM, Geyer MA, Masliah E, Kelsoe JR, Wynshaw-Boris A, et al. Reduced expression of the Sp4 gene in mice causes deficits in sensorimotor gating and memory associated with hippocampal vacuolization. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;10(4):393–406. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001621. 11/23/online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Supp DM, Witte DP, Branford WW, Smith EP, Potter SS. Sp4, a Member of the Sp1-Family of Zinc Finger Transcription Factors, Is Required for Normal Murine Growth, Viability, and Male Fertility. Developmental Biology. 1996 Jun 15;176(2):284–299. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Safe S, Kim K. Non-classical genomic estrogen receptor (ER)/specificity protein and ER/activating protein-1 signaling pathways. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008 Nov;41(5):263–275. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mao X, Moerman-Herzog AM, Wang W, Barger SW. Differential transcriptional control of the superoxide dismutase-2 kappaB element in neurons and astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006 Nov 24;281(47):35863–35872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604166200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mao X, Yang SH, Simpkins JW, Barger SW. Glutamate receptor activation evokes calpain-mediated degradation of Sp3 and Sp4, the prominent Sp-family transcription factors in neurons. J Neurochem. 2007 Mar;100(5):1300–1314. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pilc A, Chaki S, Nowak G, Witkin JM. Mood disorders: Regulation by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2008 Mar 01;75(5):997–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Witkin JM, Marek GJ, Johnson BG, Schoepp DD. Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors in the Control of Mood Disorders. CNSNeurol DisordDrug Targets. 2007 Apr;6:87–100. doi: 10.2174/187152707780363302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou R, Yuan P, Wang Y, Hunsberger JG, Elkahloun A, Wei Y, et al. Evidence for Selective microRNAs and their Effectors as Common Long-Term Targets for the Actions of Mood Stabilizers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008 doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.131. 08/13/online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palucha A, Klak K, Branski P, van der Putten H, Flor P, Pilc A. Activation of the mGlu7 receptor elicits antidepressant-like effects in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2007 Nov 01;194(4):555–562. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wieronska JM, Klak K, Palucha A, Branski P, Pilc A. Citalopram influences mGlu7, but not mGlu4 receptors' expression in the rat brain hippocampus and cortex. Brain Research. 2007 Dec 12;1184:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007 Jun 7;447(7145):661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghoussaini M, Song H, Koessler T, Al Olama AA, Kote-Jarai Z, Driver KE, et al. Multiple loci with different cancer specificities within the 8q24 gene desert. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Jul 2;100(13):962–966. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levy D, Ehret GB, Rice K, Verwoert GC, Launer LJ, Dehghan A, et al. Genome-wide association study of blood pressure and hypertension. Nature genetics. 2009 May 10; doi: 10.1038/ng.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Psychiatric GWAS Consortium A framework for interpreting genome-wide association studies of psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2009 Jan;14(1):10–17. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sullivan PF, de Geus EJC, Willemsen G, James MR, Smit JH, Zandbelt T, et al. Genome-wide association for major depressive disorder: a possible role for the presynaptic protein piccolo. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.125. 12/09/online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.