Abstract

Background

Disparities in cancer screening among U.S. women are well documented. However, little is known about Pap test use by Asian women living in the U.S.

Methods

Data for women, ages 18 and older, living in the U.S. were obtained from National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) files from 1982 to 2005. Outcomes were ever having a Pap test and having a Pap test within the preceding three years. Pap test prevalence trends were estimated by race and ethnicity and for Asian subgroups. Fractional logit models were used to predict Pap test use in 2010.

Results

Although the rate of having a Pap test within the preceding three years increased slightly from 1982 to 2005 for all U.S. women, Asian women continue to have the lowest rate. Pap test use also varied within Asian subpopulations living in the U.S. None of the races and ethnicities are predicted to reach the Pap test targets of Healthy People 2010.

Discussion

To reduce or eliminate continuing disparities in Pap test use requires targeted policy interventions.

Keywords: disparities, minority health, women's health, prevention, cancer screening

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), cervical cancer is the second most prevalent cancer and the main cause of cancer death for women in the world.1 Though the incidence and mortality rates for cervical cancer have declined in developed countries since the introduction of screening programs,2 the National Cancer Institute estimates that in 2008 there were 11,070 new cases of cervical cancer and 3,870 deaths due to cervical cancer in the U.S.3 Fortunately, cervical cancer mortality is largely preventable through early detection and treatment, and the Papanicolaou (Pap) test provides an effective and inexpensive means of early detection.4–6 Healthy People 2010 identifies two specific goals related to Pap testing. The first goal is to increase the proportion of women ages 18 years or older ever having a Pap test to 97%. The second goal is to increase the proportion of women ages 18 years or older receiving a Pap test within the preceding 3 years to 90%.7

Substantial research has documented that cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates vary by race and ethnicity.8–14 Research indicates that the rates of Pap test use also vary by race and ethnicity.15–16 In the case of Asian women living in the U.S., the rates of Pap test use appear to be consistently lower than for women in other racial and ethnic groups.15–19 While such studies document the low rates of Pap test use among Asian women living in the U.S., they are limited by small sample sizes,17,18 the use of regional or single state populations as the sources of data15,17,19 , or by single point in time rate measurements.15,17,18

To address these limitations in the current understanding of Pap test use by Asian women in the U.S., we use National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data to examine Pap test utilization patterns by race and ethnicity among women living in the U.S. during 1982 to 2005, with a special focus on patterns within Asian subpopulations. Based on these examinations, we extrapolate the utilization patterns to 2010 to predict the likelihood of reaching the Healthy People 2010 targets for Pap test use.

METHODS

Data

We used twelve-years of NHIS data; viz., 1982, 1985, 1987, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005 for women, ages 18 and older, living in the U.S. As noted by Solomon et al., the NHIS is the only national-level survey from which it is possible to estimate cervical cancer-screening rates in theU.S.20 Demographic data, strata, and primary sampling units (PSU) were retrieved from the Integrated Health Interview Series (IHIS) website (http://www.ihis.us), a cross-sectional time series of harmonized NHIS data.21–22 Variables related to Pap testing were from the original NHIS public use files, which we merged with the data retrieved from IHIS.23 Although the 1973 NHIS person file contains Pap test variables, it does not have detailed race data. The 1991 Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Supplement has a question asking about Pap tests in the past 12 months, but the data are not comparable with other years in our analysis. We therefore excluded both 1973 and 1991. Table I summarizes the sample size and weighted population of women, ages 18 years and older, with valid values in the 1982–2005 variables of ever having a Pap test by race and ethnicity.

Table 1.

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) sample size and weighted population of women ages 18 years and older with valid value in variables – ever having a Pap test by race and ethnicity: 1982–2005.

| All | Asian | Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | Other racesa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year and file name containing Pap variables | SZb | WPc | SZ | WP | SZ | WP | SZ | WP | SZ | WP | SZ | WP |

| 1982 Preventive care supplement | 38,717 | 85.2 | 619 | 1.3 | 31,410 | 68.7 | 3,977 | 9.2 | 2,348 | 5.1 | 363 | 0.8 |

| 1985 Health promotion and disease prevention supplement HPDP sample person | 18,784 | 87.4 | 258 | 1.4 | 14,492 | 70.5 | 2,914 | 9.7 | 992 | 5.2 | 128 | 0.6 |

| 1987 Cancer control supplement | 12,563 | 90.1 | 183 | 1.8 | 9,616 | 71 | 1,858 | 10 | 816 | 6.5 | 90 | 0.8 |

| 1990 Health promotion and disease prevention (HPDP) sample person supplement | 23,028 | 91.7 | 361 | 1.8 | 17,468 | 71.3 | 3,393 | 10.5 | 1,615 | 7.4 | 191 | 0.8 |

| 1992 Cancer control supplement | 6,804 | 94.6 | 133 | 2.4 | 4,933 | 73.2 | 974 | 11.1 | 697 | 6.9 | 67 | 0.9 |

| 1993 Year 2000 objectives supplement | 11,844 | 95.3 | 268 | 2.8 | 9,007 | 73.1 | 1,666 | 11.2 | 759 | 7 | 144 | 1.2 |

| 1994 Year 2000 objectives | 10,986 | 94.9 | 238 | 2.6 | 8,200 | 71.5 | 1,567 | 11.2 | 832 | 8.2 | 149 | 1.3 |

| 1998 Adult prevention supplement | 17,547 | 98.9 | 420 | 2.9 | 11,667 | 74.3 | 2,509 | 11.6 | 2,828 | 9.4 | 123 | 0.8 |

| 1999 Sample adult person section | 17,200 | 101.9 | 391 | 3 | 11,273 | 75.9 | 2,568 | 12.1 | 2,832 | 10.1 | 136 | 0.8 |

| 2000 Sample adult person section | 17,264 | 99.0 | 407 | 2.9 | 11,230 | 73.5 | 2,657 | 11.8 | 2,832 | 10 | 138 | 0.8 |

| 2003 Sample adult person section | 16,894 | 107.6 | 456 | 3.6 | 10,905 | 77.9 | 2,481 | 12.8 | 2,916 | 12.4 | 136 | 0.9 |

| 2005 Cancer screening supplement | 16,279 | 104.1 | 437 | 3.5 | 10,479 | 74.9 | 2,417 | 12.4 | 2,806 | 12.3 | 140 | 1 |

Source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 1982, 1985, 1987, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005.

Other races includes Alaskan Native, American Indian, other races, and multiple races.

SZ: Sample size

WP: Weighted population. Unit: million

Measures

Pap test variables

The outcome of interest is Pap test use, measured in two ways consistent with the Healthy People 2010 objectives. The first is a measure of whether a woman ever had a Pap test. The second measure is whether a woman had a Pap test within the preceding three years. In all but one year, there is a categorical recode indicating the time since the last Pap test. Using this information, we created a dichotomous variable representing whether respondents had a Pap test within the preceding three years. The 2005 file contains only respondents' original response to the question, "How long has it been since your last Pap Test?" in terms of time unit (days, weeks, months or years) and number of units. We constructed a recoded variable approximately commensurate with the recoded variables from the other years. To assess the reliability of our recoding scheme, we applied it to the most recent data available that had both the original response and the recode (2003). Using this data, we found a 1.6% discrepancy between the agency recode and our recode.

Race/Ethnicity Variables

The categories of race and ethnicity used in this study are Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Asian, Other Races, and Hispanic. The racial category, "Asian," includes Asian or Pacific Islander (API), Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Vietnamese, Japanese, Asian Indian, Hawaiian, Samoan, Guamian, other Asian or Pacific Islander, and other Asian. The racial category, "Other races," includes Alaskan Native, American Indian, other races, and multiple races. Since the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) classification of race and ethnicity changed between 1982 and 2005,24 we used the RACEA and HISPETH variables from IHIS to classify race and ethnicity, respectively. RACEA is an integrated variable across years permitting consistent comparison of race groups during the period from 1982 to 2005 using pre-1997 OMB racial categories.

We also examined the trend of Pap test use in four specific subpopulations of Asian women living in the U.S. (i.e., Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian, and Other API) from 1992 to 2005. Chinese, Filipino, and Asian Indian subpopulations were the only groups consistently identified in these years, so we classified all other Asian subpopulations into the single group “other API”. We excluded earlier years because detailed Asian subpopulation information was not available.

Statistical analyses

We used Stata/IC 10.1 to conduct all analyses in order to account for the complex survey design of the NHIS.25–26 Strata, PSU, and sampling weights were accommodated using the appropriate survey commands in Stata.

Although our primary analysis represents unadjusted Pap test rates over time, we examined the demographic composition of our sample across three time periods: 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. We examined the distribution of selected characteristics and test for statistically significant differences using design-based F-tests.

There were two steps in our analyses of Pap test use over time. First, to document and examine trends in Pap test use from 1982 to 2005, we estimated, by race and ethnicity, the annual prevalence rates of our two Pap test variables. Second, we used data from 1990 to 2005 to predict the rates of Pap test use in 2010 on the assumption that the 1990 – 2005 trend would continue through 2010. Next, we did these two steps analysis across Asian subpopulations using data from 1992 to 2005. Since the dependent variable in the statistical analyses is proportional, we used a fractional logit model proposed by Papke and Wooldridge to predict the rates of Pap test use by race for 2010.27 This was accomplished in Stata using the generalized linear model (glm) command with a logit functional form and robust standard errors. A standard regression model will model the expected conditional proportional dependent variable as a linear probability and may predict expected values outside the boundaries of 0 and 100%. In contrast, a fractional logit model models the expected conditional proportional dependent variable as a non-linear function by using a functional form that ensures the predicted values lay between 0 and 100%.27

RESULTS

Asian women and other racial/ethnic groups

Table II shows selected characteristics of women ages 18 and older for three time periods – 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Overall, the demographic composition of adult women in the U.S. has changed over time. The proportion of women who are Asian, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic are increasing, while the proportion of non-Hispanic White women is decreasing (F-test = 13.0; p < 0.001). Women in the contemporary U.S. are also older (F-test = 830; p < 0.001) and more educated (F-test = 837; p < 0.001), but report lower levels of self-rated health than 20 years ago (F-test = 71.5; p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Selected characteristics of women ages 18 years and older in the U.S. by time period, NHIS 1982–2005 (N= 230,258).

| 1980s (N= 86,432) | 1990s (N= 90,347) | 2000s (N= 53,479) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| na | % | n | % | n | % | P-value | |

| Hispanic | |||||||

| No | 80,016 | 92.7 | 80,230 | 91.9 | 44,368 | 90.3 | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 5,728 | 6.5 | 9,910 | 7.9 | 9,111 | 9.7 | |

| Unknown | 688 | 0.8 | 207 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Race | |||||||

| Black | 11,089 | 11.6 | 13,210 | 12.3 | 8,090 | 12.8 | < 0.001 |

| Asian | 1,439 | 1.7 | 1,924 | 2.4 | 1,438 | 2.9 | |

| Chinese | 335 | 0.4 | 284 | 0.6 | |||

| Filipino | 353 | 0.4 | 353 | 0.7 | |||

| Asian India | 201 | 0.3 | 236 | 0.5 | |||

| Other API b | 706 | 0.9 | 627 | 1.3 | |||

| White | 67,047 | 78.8 | 64,311 | 76.4 | 34,341 | 73.6 | |

| Other/Multiple c | 770 | 0.9 | 836 | 0.9 | 437 | 0.9 | |

| Hispanic | 5,728 | 6.5 | 9,910 | 7.9 | 9,111 | 9.7 | |

| Unknown | 359 | 0.4 | 156 | 0.2 | 62 | 0.1 | |

| Age | |||||||

| 0–30 | 35,520 | 41.1 | 20,389 | 23.0 | 11,156 | 20.9 | < 0.001 |

| 31–50 | 24,394 | 27.8 | 35,254 | 38.6 | 20,716 | 37.7 | |

| 50+ | 26,518 | 31.1 | 34,704 | 38.4 | 21,607 | 41.4 | |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| Not married | 45,324 | 51.9 | 46,575 | 51.3 | 29,372 | 54.5 | < 0.001 |

| Married | 40,697 | 47.6 | 43,479 | 48.4 | 23,778 | 45.0 | |

| Unknown | 411 | 0.5 | 293 | 0.3 | 329 | 0.6 | |

| Education | |||||||

| High school degree or less | 62,865 | 72.0 | 51,371 | 54.3 | 26,043 | 45.9 | < 0.001 |

| College Degree or some college | 18,941 | 22.6 | 32,225 | 37.9 | 23,012 | 45.3 | |

| More than college | 3,852 | 4.6 | 6,221 | 7.2 | 3,825 | 7.8 | |

| Unknown | 774 | 0.9 | 530 | 0.6 | 599 | 1.0 | |

| Health status | |||||||

| Excellent | 29,156 | 33.8 | 26,169 | 29.6 | 14,140 | 27.5 | < 0.001 |

| Very good | 22,904 | 26.8 | 27,094 | 30.7 | 16,872 | 32.3 | |

| Good | 22,381 | 25.7 | 24,145 | 26.2 | 14,518 | 26.3 | |

| Fair | 8,465 | 9.7 | 9,466 | 9.9 | 5,893 | 10.3 | |

| Poor | 3,002 | 3.4 | 3,266 | 3.4 | 2,019 | 3.5 | |

| Unknown | 524 | 0.6 | 207 | 0.2 | 37 | 0.1 | |

Source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 1982, 1985, 1987, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005. (Asian subpopulation data from 1992, 1993, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005)

n = unweighted number of observations

Other Asian or Pacific Islander (API) includes Korean, Vietnamese, Japanese, Hawaiian, Samoan, Guamian, other API, and other Asian.

Other/Multiple includes Alaskan Native, American Indian, other races, and multiple races.

Overall, for 1982–2005, the rates of ever having a Pap test for Asian women living in the U.S. do not change much over time. The proportion of Non-Hispanic White and Black women who ever had a Pap test is greater than 90% throughout the period. In contrast, the rate of ever having a Pap test among Asian women is generally in the 70% range and peaks at only 80%. With the exception of 1987 Hispanic women, this 80% rate is lower than the rate for any other racial or ethnic group during the 24-year period. (Figure not shown)

On the assumption that the trend from 1990–2005 will remain constant another five years, the 2010 predicted rate (not shown) for Asian women living in the U.S. of ever having a Pap test is 75%. Compared with women from all other racial and ethnic groups, the predicted rate for Asian women is the lowest. Moreover, the rates for women in all racial and ethnic groups are lower than the 97% target in Healthy People 2010. The predicted rate for Asian women is furthest from the target. (Figure not shown)

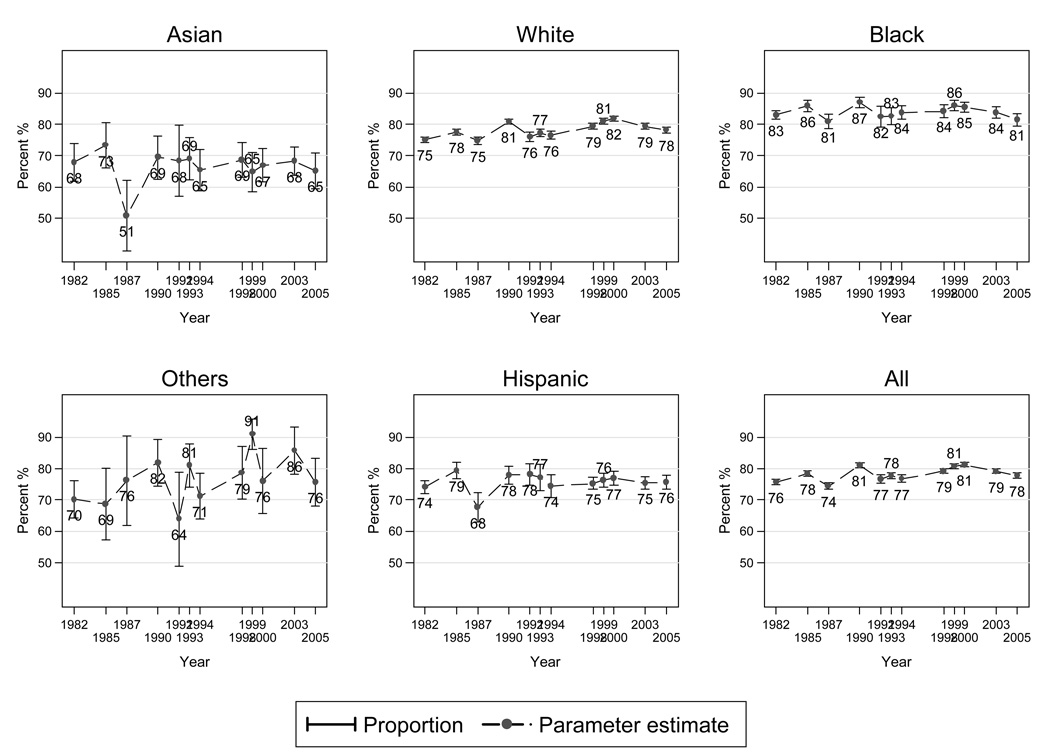

Figure 1 shows, for 1982 to 2005, the actual rates of having a Pap test in the preceding three years for women living in the U.S. Non-Hispanic Black women have the highest rates of Pap test use within the past three years, exceeding 80% throughout the period. Non-Hispanic White women have rates in the high 70% to low 80% range, while Hispanic women have rates in the mid to high 70% range during the same period. In contrast to all these groups, Asian women tend to have the lowest rates of Pap testing within the preceding three years with rates consistently in the 60% range.

Figure 1.

Percent of U.S. women 18 years and older who had a Pap test within the preceding 3 years, by race and ethnicity, 1982–2005.

Source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 1982, 1985, 1987, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005.

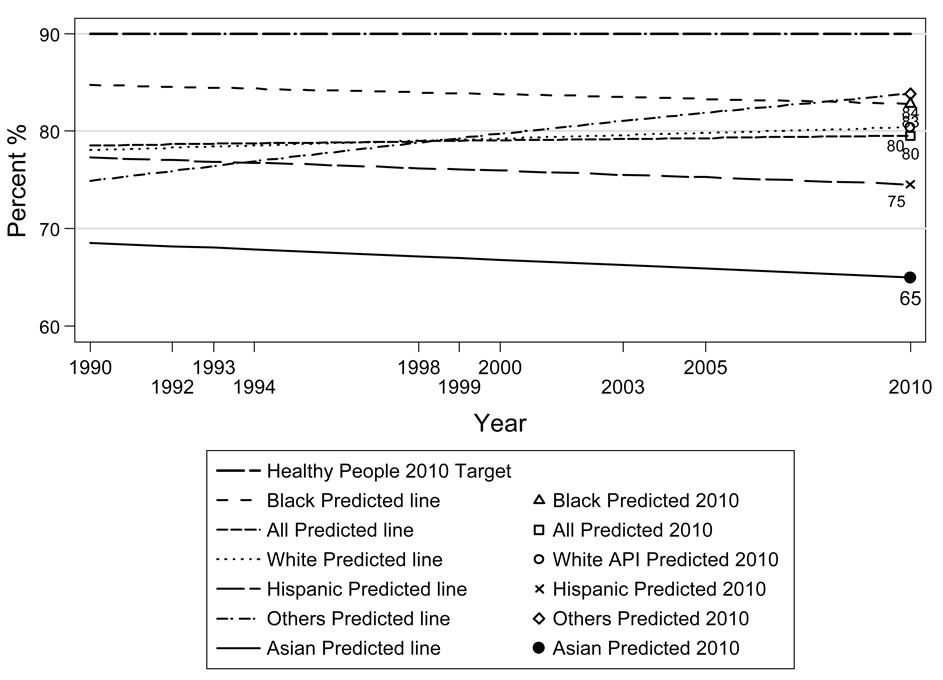

Figure 2 shows the overall trend and predicted rates both for U.S. Asian women and U.S. women in other racial and ethnic groups. For Asian women, the 2010 predicted rate of having a Pap test in the preceding three years is 65%. On the assumption that the trend from 1990–2005 will remain constant another five years, the 2010 rate of Asian women having a Pap test in the preceding three years will be lower than the rates for women in all other racial and ethnic groups. Furthermore, no racial or ethnic group has a predicted Pap test utilization rate close to the 90% target set in Healthy People.

Figure 2.

Predicted trend of U.S. women 18 years and older who had a Pap test within the preceding 3 years 1990 – 2005 and forecast 2010 by race and ethnicity.

Source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 1990, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005.

Asian Subpopulations

From 1992 to 2005, Filipino women have the highest rates of ever having a Pap test. The 2010 prediction of the rate of ever having a Pap test is the lowest for Asian Indian women. (Figure not shown)

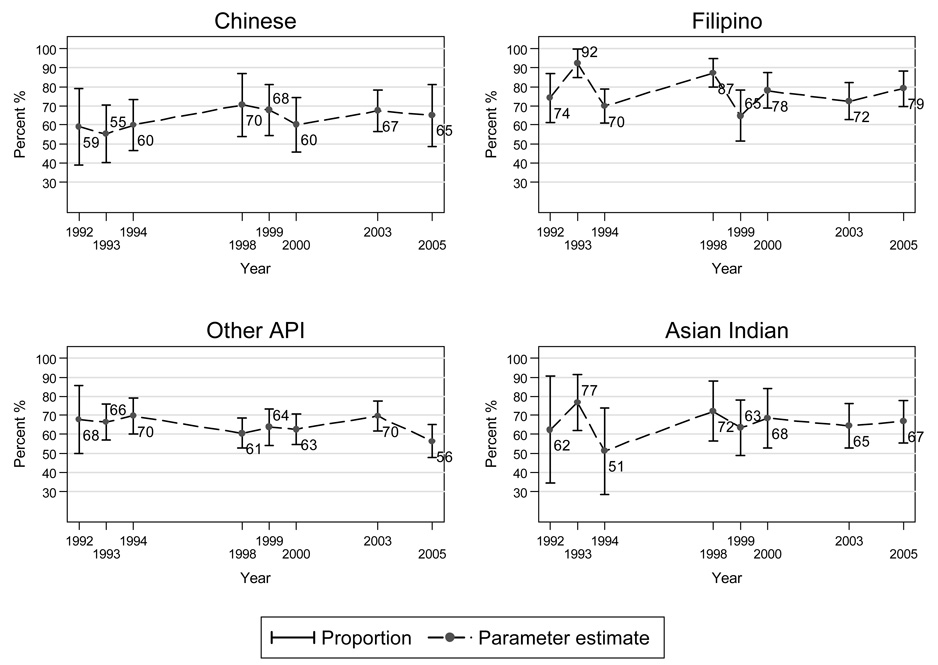

Figure 3 shows fluctuations in the rates of having a Pap test in the preceding three years during the fourteen-year study period for all four Asian subpopulations. Filipino women have, with the exception of 1999, the highest rates of having a Pap test within the preceding three years.

Figure 3.

Percent of U.S. Asian women 18 years and older who had a Pap test within the preceding 3 years by Asian subpopulation, 1992 – 2005.

Source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 1992, 1993, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005.

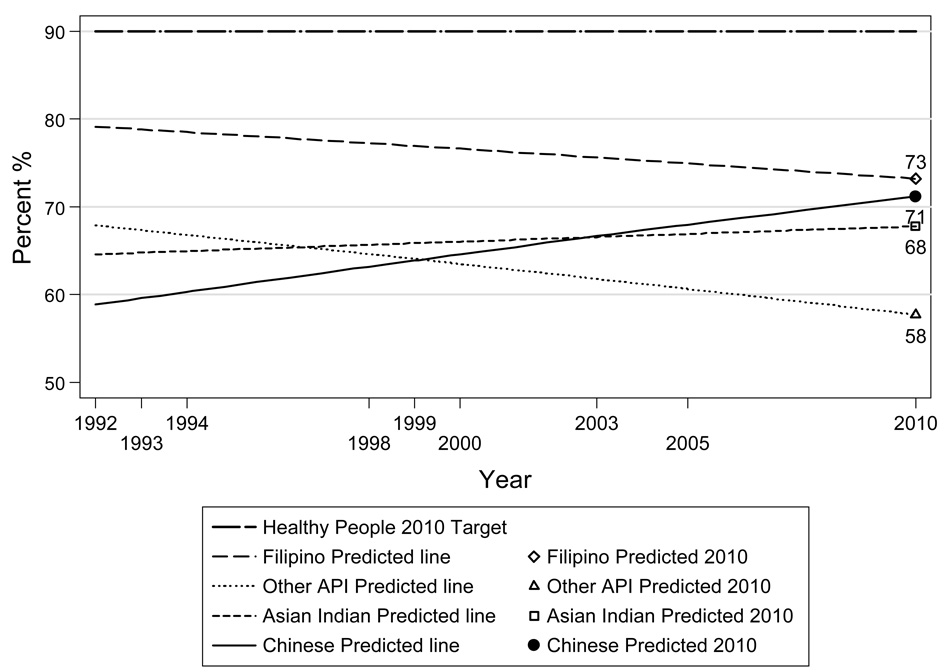

Figure 4 presents the overall trend and the 2010 prediction of the rates of having a Pap test in the preceding three years among four subpopulations of Asian women living in the U.S. from 1992 to 2005. The 2010 prediction of the rate of having a Pap test in the preceding three years is highest for Filipino women and lowest for Other API women. None of the four predicted Pap test utilization rates is close to the 90% target set in Healthy People.

Figure 4.

Predicted trend of U.S. Asian women 18 years and older who had a Pap test within the preceding 3 years 1992 – 2005 and forecast 2010 by Asian subpopulation.

Source: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 1992, 1993, 1994, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005.

DISCUSSION

Using NHIS data from 1982 to 2005, we examined the rates of Pap test use for Asian women living in the U.S. and for U.S. women in other racial and ethnic categories. We predicted the likelihood of women in all groups reaching the Pap test targets of Healthy People 2010 by assessing two outcomes – ever having a Pap test and having a Pap test within the preceding three years. The analyses of Pap test use for Asian women provide several important findings. First, from 1982 to 2005, there is a persistent disparity between the use of Pap tests by Asian women and by women in other racial and ethnic groups. This finding is consistent with point-in-time studies.15–19, 28 Second, if the trend from 1990 to 2005 continues, it seems unlikely that Asian women will meet the Healthy People 2010 targets for Pap testing. More generally, our predictions suggest that racial and ethnic disparities in Pap test use will continue relatively unchanged until at least 2010.

Analyses of Pap test use by women in Asian subpopulations living in the U.S. show that the rates of ever having a Pap test and having a Pap test within the preceding three years varied within those subpopulations. Thus, disparities in Pap test use are persistent both across U.S. racial and ethnic groups as well as across Asian subpopulations living in the U.S. These results are consonant with the finding from Kagawa-Singer et al. who report varied Pap test rates among seven subgroups of Asian women living in California.29 Our analyses further suggest that these disparities in Pap test use within Asian subpopulations in the U.S. are likely to continue.

To improve the rate of Pap test utilization among minority and underserved women, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) in 1991. Based on the Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act of 199030–31, the NBCCEDP helps minority and underserved women access breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services. Even though the NBCCEDP has been in existence for nearly two decades and over 1 million Women received NBCCEDP-funded Pap tests during January 2003 to December 200732 , our analyses show the utilization of Pap tests by Asian women is still lowest for women living in the U.S.

The results of our analyses, as well as the conclusions drawn from them, should be considered in light of limitations. First, using NHIS data, which relies on self-reports of Pap test use, could result in problems of overestimation. Previous studies have documented concerns about the validity of self-reported Pap test data. Some evidence suggests that women may confuse having a pelvic exam with having a Pap test.33–34 For example, Fiscella et al. found that the rates at which Hispanic and African American women reported having a Pap tests were greater than the rates supported by an examination of the relevant medical claim data.35In the same vein, recall bias may also affect determination of the time since the last Pap test.36 As reported by Newell et al., self-reported times of Pap tests are likely to be more recent than the date of their actual occurrence.37

Second, because administration of the NHIS occurs in only English or Spanish, it is likely that Asian women who do not speak English or Spanish are underrepresented in the NHIS sample. This is important because, as has been documented by several studies, Asian women who do not speak English tend to have fewer Pap tests.38 For example, Ponce et al. found that among Asian women surveyed in the California Health Interview Survey, those who interviewed in Vietnamese, Cantonese, Korean or Mandarin had significantly lower rates of having a Pap test in the preceding three years than did Asian women who interviewed in English.39 Kagawa-Singer et al. found that non-English speaking Asian American and Pacific Islander women living in the U.S. tend to have the lowest rates of Pap test use relative to women in other racial categories.40 Among Chinese American women, ages 40 to 69 years, Yu et al. found that less than one-third of those who spoke English poorly or not at all reported ever having had a Pap test, compared to 86% of those who spoke English moderately well or very well.41

Third, Pap test questions in the NHIS were not formulated uniformly across all years. For example, in 1982 the Pap test question asked was, “About how long has it been since you had a Pap smear test?” In contrast, in1998 the Pap test question asked was, “When did you have your most recent pap smear test? Was it a year ago or less, more than 1 year but not more than 2 years, more than 2 years but not more than 3 years, more than 3 years but not more than 5 years, or over 5 years ago?” Because of this variation in the wording, our analyses rely on comparable but not identical measures of Pap test use over time.

Finally, it is possible that the NHIS populations and subpopulations analyzed included women for whom Pap testing is no longer recommended (e.g. women having a hysterectomy with complete removal of the cervix). For example, using 1991, 1998 and 2000 NHIS data, Solomon et al. estimated that approximately 15% of the women who reported having a Pap test were women with hysterectomies.20 While in some years the NHIS had a question about having a hysterectomy, there is no way to distinguish whether the cervix was completely removed, and standard Pap test guidelines recommend that women with only partial cervix removal continue with recommended Pap test screening.31 Because the NHIS data do not permit exclusions of women without a cervix, the real rate of Pap test use within the preceding three years by women for whom the test is both appropriate and recommended may be underestimated.

CONCLUSION

Disparities between rates of Pap test use by Asian women living in the U.S., and rates for U.S. women in other racial and ethnic categories persist across the period from 1982–2005. Disparities in Pap test use also exist across Asian subpopulations living in the U.S. for the same period. As our analyses demonstrate, if current trends continue, it is quite likely that Asian women will not reach the Healthy People 2010 targets for Pap test use, and disparities both across Asian subpopulations and between Asian women and women in other racial and ethnic categories in the use of Pap tests will continue to exist. This is especially troubling because the Pap test is an effective, inexpensive test that is typically covered by both private and public health insurance. For this reason, we believe that changes in medical education and clinical practices are a good first step to reducing the disparities and increasing the use of Pap tests by Asian women living in the U.S. For example, a simple measure would be to attach a memo to the charts reminding physicians and other health professionals to speak with their patients about the importance of having a Pap test. Of course, knowing a problem exists and knowing how best to address and resolve that problem are two entirely different matters. Our analyses have uncovered the disparities problem for Asian women living in the U.S., and have characterized some of the problem's scope. Further research that aims to identify and understand the salient determinants of Pap test use by Asian women living in the U.S. is needed to better help physicians and health care workers enhance their patient care for this population.

Acknowledgments

Portions of the results in this study were presented at the 4th Annual Women's Health Research Conference at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2007 and 136th American Public Health Association Annual Meeting in San Diego, California, 2008. We acknowledge the helpful comments from the participants at the conference and anonymous reviewers. Any error remains ours. This study was funded by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, USA (R01HD046697 to the University of Minnesota (PI: Lynn A. Blewett)).

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. 2006 [PubMed]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F. Chapter 2: The burden of HPV-related cancers. Vaccine. 2006;24S3 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.111. S3/11–S3/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cancer Institute. Cervical cancer. [Accessed March 29, 2009]; http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/cervical/.

- 4.Schiffman M, Castle PE. The promise of global cervical-cancer prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2101–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer: Prevention and early detection. [Accessed November 30, 2008]; http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_6x_cervical_cancer_prevention_and_early_detection_8.asp?sitearea=PED.

- 6.National Cancer Institute. Cervical cancer screening. [Accessed November 30, 2008]; http://progressreport.cancer.gov/doc_detail.asp?pid=1&did=2007&chid=72&coid=717&mid=#benefits.

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed February 8, 2009];Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, November 2000; Healthy People. (2nd ed.). 2010 Volume I http://www.healthypeople.gov/Document/tableofcontents.htm#volume1.

- 8.Mills PK, Yang RC, Riordan D. Cancer incidence in the Hmong in California, 1998–2000. Cancer. 2005;104(12 Suppl):2969–2974. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saraiya M, Ahmed F, Krishnan S, et al. Cervical cancer incidence in a prevaccine era in the United States, 1998–2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:360–370. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000254165.92653.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese Ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller BA, Kolonel LN, Bernstein L, et al., editors. Racial/Ethnic Patterns of Cancer in the United States 1988–1992. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1996. NIH Pub. No. 96–4104. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang RC, Mills PK, Riordan DG. Cervical Cancer Among Hmong women in California, 1998 to 2000. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Alba I, Ngo-Metzger Q, Sweningson JM, et al. Pap smear use in California: Are we closing the racial/ethnic gap? Prev Med. 2005;40:747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keppel KG. Ten largest racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States based on Healthy People 2010 objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:97–103. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kagawa-Singer M, Wong L, Shostak S, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening practices for low-income Asian American women in ethnic-specific clinics. Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2005;3:180–192. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaudhry S, Fink A, Gelberg L, et al. Utilization of papanicolaou smears by south Asian women living in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:377–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiatt RA, Pasick RJ, Stewart S, et al. Community-based cancer screening for underserved women: Design and baseline findings from the breast and cervical cancer intervention study. Prev Med. 2001;33:190–203. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon D, Breen N, McNeel T. Cervical cancer screening rates in the United States and the potential impact of implementation of screening guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:105–111. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson PJ, Blewett LA, Ruggles S, et al. Four decades of population health data: The Integrated Health Interview Series. Epidemiology. 2008;19(6):872–875. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318187a7c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. [Accessed November 30, 2008];Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center, Integrated Health Interview Series: Version 1.0. http://www.ihis.us.

- 23.Integrated Health Interview Series. Link NHIS public use files to IHIS data. [Accessed November 30, 2008]; http://www.ihis.us/ihis/userNotes_links.shtml.

- 24.Office of Management and Budget. Provisional guidance on the implementation of the 1997 standards for the collection of Federal data on race and ethnicity. [Accessed November 30, 2008]; http://www.ofm.wa.gov/pop/race/omb.pdf.

- 25.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software; Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.StataCorp. Survey Data Reference Manual. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parke L, Wooldridge JM. Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401(K) plan participation rates. J Applied Econometrics. 1996;11:619–632. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen MS. Cancer health disparities among Asian Americans: What we know and what we need to do. Cancer. 2005;104(12 suppl):2895–2902. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kagawa-Singer M, Pourat N, Breen N, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening rates of subgroups of Asian American women in California. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64:706–730. doi: 10.1177/1077558707304638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryerson A, Benard V, Major A. National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program: 1991–2002 national report. [Accessed April 11, 2009];Atlanta GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available at http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/library/online/bc.htm.

- 31.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. Cancer screening in the United States, 2007: A review of current guidelines, practices, and prospects. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:90–104. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. National aggregate. [Accessed April 11, 2009]; http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/data/summaries/national_aggregate.htm#cervical.

- 33.Blake DR, Weber BM, Fletcher KE. Adolescent and young adult women's misunderstanding of the term Pap smear. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:966–970. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pizarro J, Schneider TR, Salovey P. A source of error in self-reports of Pap test utilization. J Community Health. 2002;27:351–356. doi: 10.1023/a:1019888627113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiscella K, Holt K, Meldrum S, et al. Disparities in preventive procedures: comparisons of self-report and Medicare claims data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudman S, Warnecke R, Johnson T, et al. Cognitive aspects of reporting cancer prevention examinations and tests. Vital Health Stat. 1994;6(7):324–329. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newell S, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. Accuracy of patients' recall of Pap and cholesterol screening. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1431–1435. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen TT, McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, et al. Predictors of cervical Pap smear screening awareness, intention, and receipt among Vietnamese-American women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00499-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ponce NA, Chawla N, Babey SH, et al. Is there a language divide in Pap test use? Med Care. 2006;44:998–1004. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233676.61237.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kagawa-Singer M, Pourat N. Asian American and Pacific Islander breast and cervical carcinoma screening rates and Healthy People 2000 objectives. Cancer. 2000;89:696–705. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<696::aid-cncr27>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu ESE, Kim KK, Chen EH, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Chinese American women. Cancer Practice. 2001;9:81–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009002081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]