Abstract

Dopamine D3 receptors have the highest dopamine affinity of all dopamine receptors, and may thereby regulate dopamine signaling mediated by volume transmission. Changes in D3 receptor isoform expression may alter D3 receptor function, however little is known regarding coordination of D3 isoform expression in response to perturbations in dopaminergic stimulation. In order to determine the effects of dopamine receptor stimulation and blockade on D3 receptor alternative splicing, we determined D3 and D3nf isoform mRNA expression following treatment with the D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904, and the indirect dopamine agonist amphetamine. Expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) mRNA, the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, was also determined. The D3/D3nf mRNA expression ratio was increased in ventral striatum, prefrontal cortex and hippocampus six hours following D3 antagonist NGB 2904 treatment, and remained persistently elevated at 24 hours in hippocampus and substantia nigra/ ventral tegmentum. D3 mRNA decreased 65% and D3nf mRNA expression decreased 71% in prefrontal cortex 24 hours following amphetamine treatment, however these changes did not reach statistical significance. TH mRNA expression was unaffected by D3 antagonist NGB 2904, but was elevated by amphetamine in ventral striatum, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. These findings provide evidence for an adaptive response to altered D3 receptor stimulation involving changes in D3 receptor alternative splicing. Additionally, these data suggest D3 autoreceptor regulation of dopamine synthesis does not involve regulation of TH mRNA expression. Finally, the observation of regulated TH mRNA expression in dopamine terminal fields provides experimental support for the model of local control of mRNA expression in adaptation to synaptic activity.

Keywords: Dopamine D3 receptor, NGB 2904, D3nf, alternative splicing, Amphetamine, Hippocampus, tyrosine hydroxylase, Tyrosine 3-Monooxygenase

1. Introduction

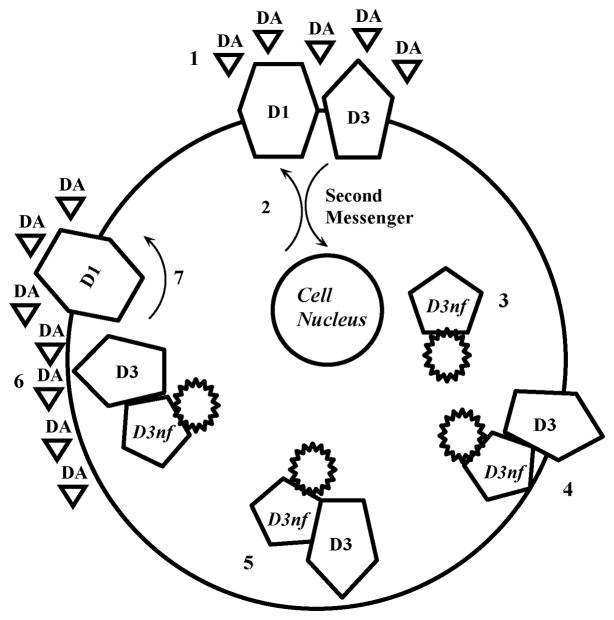

Dopamine plays an important role in modulating the expression of primitive, highly motivated behaviors by way of signaling through dopamine D1-family and D2-family receptors. Dopamine D1-family receptors are intronless, while D2- family receptor genes contain intron-exon junctions, and alternatively spliced receptor variants provide a potential mechanism for receptor regulatory control. Seven distinct alternatively spliced dopamine D3 receptor variants have been described, including the full length D3 receptor (called “D3”), and a shorter receptor isoform, D3S, (Fishburn, Belleli, David, Carmon, and Fuchs, 1993). Both D3 and D3S exhibit high-affinity dopamine binding. Five additional alternatively spliced variants have also been described which do not bind dopamine, and are believed to function instead through regulation of receptor dimerization (Snyder, Roberts, and Sealfon, 1991). D3nf is the best characterized of the non-dopamine-binding splice variants. D3nf is formed through a deletion of 98 base pairs in the third cytoplasmic loop, causing a coding frame shift resulting in creation of a novel 55 amino acid peptide and appearance of a new premature stop codon. The prematurely-truncated protein thus lacks transmembrane domains 6 and 7 (Schmauss, Haroutunian, Davis, and Davidson, 1993;Liu, Bergson, Levenson, and Schmauss, 1994), and does not bind dopamine (Elmhurst, Xie, O’Dowd, and George, 2000). The D3nf alternative splice junction nucleotide sequences are highly conserved across species between rodent and human, suggesting the functional importance of these splicing events may have exerted evolutionary pressure to conserve gene structure. D3nf binds to the full-length D3 receptor subunit (Nimchinsky, Hof, Janssen, Morrison, and Schmauss, 1997;Elmhurst, Xie, O’Dowd, and George, 2000;Karpa, Lin, Kabbani, and Levenson, 2000) and inhibits dopamine binding to full-length D3 receptor (Elmhurst, Xie, O’Dowd, and George, 2000). D3nf/D3 dimerization redirects full-length D3 receptor localization away from the plasma membrane into an intracellular compartment (Karpa, Lin, Kabbani, and Levenson, 2000). Dopamine D3 receptor mRNA expression is decreased in cortex of schizophrenia patients (Schmauss, Haroutunian, Davis, and Davidson, 1993), while increased D3nf splicing efficiency was observed in cortex of post-mortem tissue from schizophrenia patients (Schmauss, 1996). Collectively, these observations suggest that, in a manner analogous to dimerization playing an important role in modulation of cell signaling for the homologous insulin and gonadotropin releasing hormone receptors (Kahn, Baird, Flier, Grunfeld, Harmon, Harrison, Karlsson, Kasuga, King, Lang, Podskalny, and Van Obberghen, 1981;Gregory, Taylor, and Hopkins, 1982), adaptive responses to alterations in dopamine signaling may be regulated in part via D3nf dimerization with full-length D3 receptor. Thus, by altering the ratio of D3 to D3nf expression, alterations in dopamine D3 receptor isoform expression could contribute to functional states of altered dopaminergic activity (Pritchard, Logue, Taylor, Ahlbrand, Welge, Tang, Sharp, and Richtand, 2006;Richtand, 2006). This proposed dominant-negative model of D3nf function suggests that a decrease in the D3/D3nf ratio would lead to diminished availability of accessible D3 receptor and thereby decrease dopamine D3 receptor signaling (as illustrated in Figure 1). Of interest, D3/D3nf mRNA expression ratios differ in high responders vs. low responders to novelty (Pritchard, Logue, Taylor, Ahlbrand, Welge, Tang, Sharp, and Richtand, 2006), suggesting that individual differences in D3 receptor alternative splicing may contribute to differences in behavioral responses to novelty and drug abuse vulnerability, and supporting the hypothesis that alternative splicing may contribute to regulation of D3 dopamine receptor function. At present, however, little is known regarding the coordination of D3 and D3nf expression in response to perturbations in dopaminergic stimulation. In order to determine the effects of dopamine receptor stimulation and blockade on dopamine D3 receptor alternative splicing, we determined D3 and D3nf mRNA expression levels following treatment with the indirect dopamine agonist amphetamine, and the selective D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904. Additionally, because the role of D2 vs. D3 autoreceptor regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) function has not been unambiguously determined (Koeltzow, Xu, Cooper, Hu, Tonegawa, Wolf, and White, 1998;O’Hara, Uhland-Smith, O’Malley, and Todd, 1996;Goldstein, 1995), the expression level of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA, the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, was also determined.

Figure 1. D3/ D3nf model of adaptive response to altered dopamine levels.

The symbol  represents the novel 55 amino acid carboxy-terminal tail D3nf sequence, resulting from the alternative splicing frame shift. 1), Drugs of abuse, stress, and psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia increase extracellular dopamine. 2) D1 and D3 receptor stimulation activate opposing intracellular signaling systems. D3 receptor has the highest dopamine affinity. Persistent D3 stimulation results in homeostatic mechanisms opposing receptor stimulation, including 3) increased D3nf expression. 4) D3nf and D3 dimerize, directing the D3/D3nf dimer 5) towards intracytoplasmic trafficking pools and removing D3 receptor from the synaptic membrane. 6) At the next elevated extracellular dopamine exposure D3 receptor is not available to bind dopamine. 7) The result is release of D3 receptor-mediated opposition to D1 receptor stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity.

represents the novel 55 amino acid carboxy-terminal tail D3nf sequence, resulting from the alternative splicing frame shift. 1), Drugs of abuse, stress, and psychiatric conditions including schizophrenia increase extracellular dopamine. 2) D1 and D3 receptor stimulation activate opposing intracellular signaling systems. D3 receptor has the highest dopamine affinity. Persistent D3 stimulation results in homeostatic mechanisms opposing receptor stimulation, including 3) increased D3nf expression. 4) D3nf and D3 dimerize, directing the D3/D3nf dimer 5) towards intracytoplasmic trafficking pools and removing D3 receptor from the synaptic membrane. 6) At the next elevated extracellular dopamine exposure D3 receptor is not available to bind dopamine. 7) The result is release of D3 receptor-mediated opposition to D1 receptor stimulation of adenylate cyclase activity.

2. Materials and Methods

Animals

DBA/2J mice were chosen for study because previous work in our laboratory suggested DBA/2J mice display augmented dopamine D3 receptor function relative to C57BL/6J mice (McNamara, Levant, Taylor, Ahlbrand, Liu, Sullivan, Stanford, and Richtand, 2006), suggesting this mouse strain might provide more robust mRNA expression to detect adaptive change in mRNA levels in response to dopamine D3 receptor stimulation and/or blockade. Adult (8–9 weeks old) male DBA/2J mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, MA) were acclimated to their home cage for at least 1 week prior to drug treatment and tissue collection. Mice were housed in groups of 4–5 per cage, with food and water available ad libitum. Mice were maintained under standard vivarium conditions on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle, and all tissue collection were conducted during the light portion of the cycle. Adequate measures were taken to minimize pain or discomfort, and all experimental procedures were approved by the Cincinnati Department of Veteran Affairs, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Drugs

NGB 2904 (N-(4-[4-{2,3-dichlorphenyl}-1piperazinyl]butyl)-2-fluorenylcarboxamide) (Yuan et al., 1998) was dissolved in 50:50 polyethylene glycol (400):0.9% NaCl. NGB 2904 has 830-fold selectivity for rat D3 vs. D2 receptor expressed in Sf9 cells (Newman, Cao, Bennett, Robarge, Freeman, and Luedtke, 2003), 155-fold selectivity for cloned primate D3 vs. D2 receptor (Yuan, Chen, Brodbeck, Primus, Braun, Wasley, and Thurkauf, 1998), 60–90-fold selectivity for human D3 vs. D2 receptor (Grundt, Carlson, Cao, Bennett, McElveen, Taylor, Luedtke, and Newman, 2005), and greater than 3,500-fold selectivity for D3 vs D4 receptor. NGB 2904 also has 160-fold selectivity for D3 vs. rat 5HT2 receptor (Yuan, Chen, Brodbeck, Primus, Braun, Wasley, and Thurkauf, 1998). A global receptor screen indicated negligible affinity at other binding sites, including α1 adrenergic receptors (Yuan, Chen, Brodbeck, Primus, Braun, Wasley, and Thurkauf, 1998). The 1 mg/kg NGB 2904 dose selected for study has been shown previously to elevate spontaneous locomotion in wild-type, but not D3 receptor knockout mice. NGB 2904 also elevates amphetamine-stimulated locomotion in wild-type, but not D3 receptor knockout mice (Pritchard, Newman, McNamara, Logue, Taylor, Welge, Xu, Zhang, and Richtand, 2007).

D-amphetamine sulfate (AMPH) (Research Biochemicals, Int., Natick, MA) was dissolved in sterile 0.9% NaCl, and drug concentration is described as free base. The 10 mg/kg amphetamine dose selected for study causes a stereotyped behavioral response, preceded and followed by elevated locomotor behavior (Segal and Kuczenski, 1994). Control injections consisted of an equivalent volume of the drug vehicle, and all injections were administered subcutaneously in a volume of 1.0 ml/kg.

D3R and D3nf mRNA expression

Naïve adult (8–9 weeks) male DBA/2J mice (n = 7–9 mice/group) were sacrificed by decapitation 6 or 24 hours following treatment, brains extracted, and ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens [NAc], Islands of Calleja, and olfactory tubercle), hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and midbrain (substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum [SN/VTA]) isolated and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissue from individual animals was homogenized (Caframo Model RZR1 homogenizer) in 1.0 ml of Tri Reagent per 50–100 mg of tissue, and total RNA isolated and precipitated according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH). Pellets were resuspended in nuclease-free water and total RNA concentrations determined by A260 measurements. Samples were then diluted in nuclease-free water to achieve a final concentration of 0.1 μg/μl. D3R, D3nf, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA expression were determined by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) as described by others (Medhurst et al., 2000). Primers and fluorogenic probes were designed using Primer Express v.2.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) based on the mouse mRNA sequences for GAPDH (GenBank accession number M32599), Tyrosine hydroxylase (GenBank accession number NM_009377), D3R (accession number NM_007877), and D3nf determined from the full-length mouse D3R sequence using sequence homology to rat and human splice junctions. Primers used for GAPDH amplification were 5′-TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTGA-3′ and 5′-CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTGA-3′ and the probe sequence was 5′-CCGCCTGGAGAAACCTGCCAAGTATG-3′. Primers used for tyrosine hydroxylase amplification were 5′-CCGTCATGCCTCCTCACCTAT-3′ and 5′-TGAACCAGTACACCGTGGAGAGT-3′ and the probe sequence was 5′-ACCCATGTTGGCTGACCGCACA-3′. The sequences of D3 primers were 5′-GAACTCCTTAAGCCCCACCAT-3′ and 5′-GAAGGCCCCGAGCACAAT -3′ and the probe sequence was 5′-ACCCAAGCTCAGCTTAGAGGTTCGA-3′. The D3nf primers were 5′-ACTCGGAACTCCTTAAGTACCACTTC-3′ and 5′-GAAGGCCCCGAGCACAAT-3′ and the probe was 5′-AGAAGAAGGCCACCCAGATGGTGG-3′ (Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, TX). Each probe was conjugated to a FAM reporter at the 5′ end and a TAMRA quencher at the 3′ end. A portion of the forward primer and the entire probe for D3R were located within the 98 nucleotide sequence which was deleted in D3nf, such that only the full length D3R cDNA was amplified by the D3R primers. The forward primer for D3nf spanned the splice junction and amplified only the D3nf cDNA. In this way, the primer sets uniquely amplified full length D3R or D3nf without overlap. The reverse primer for D3R and D3nf and the probe for GAPDH spanned intron-exon junctions to minimize genomic DNA contamination. Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed using a two-step methodology. A standard curve was constructed for each brain region by combining the total RNA of untreated mice. Standard curves consisted of seven points, using twofold, serial dilutions of known concentrations of total RNA. All reagents for real-time RT-PCR were obtained from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA unless otherwise stated. Reverse transcription was performed using the 9600 GeneAmp thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT). For each 50 μl reaction, 10 μl of diluted total RNA was mixed with 6.25 μl random hexamer primers (100 μM), 5 μl PCR Buffer (10X), 6 μl MgCl2 (25mM), 2.5 μl dNTP mix (10 mM), 0.5 μl DTT (0.1M), 1.25 μl RNaseOUT, 1.25 μl MMLV RT and 17.25 μl nuclease-free water (Ambion, Austin, TX). For reverse transcription, samples were heated to 37°C for 1 hour and terminated by heating to 96°C for 5 min. Standard curves and experimental samples were prepared from the same cDNA for GAPDH, but at a 10-fold lower concentration. 5 μl of each cDNA sample was aliquoted into 96-well MicroAmp optical plates (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in duplicate. A mastermix of the following components was made and 20ul added to each sample for a total volume of 25μl: 2μl PCR Buffer, 0.5μl dNTP mix, 1.4μl MgCl2 for D3R and GAPDH, 3.4μl MgCl2 for D3nf, 0.5μl of forward and reverse primers (50 μM), 0.63μl probe (10 μM), 0.5μl ROX (50X) (BioRad,Hercules, CA), 0.25μl Platinum Taq polymerase and 13.72μl of water for D3R and GAPDH and 11.71μl for D3nf. Cycling parameters were as follows in a 7500 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Applied Biosystems): 95°C for 10 minutes (hot start), 95°C for 30 seconds (melting), 60°C for one minute (annealing and extension). The last two steps were repeated for 45 cycles. A plot of threshold cycle (Ct, defined as the cycle during which probe fluorescence reached ten times baseline) vs. log input RNA quantity was prepared for each standard curve. Linear regression analysis was performed using the 7500 Sequence Detection Software version 1.2.3 (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantities for D3R, D3nf, tyrosine hydroxylase and GAPDH mRNA in unknown samples were interpolated from the regression line for the corresponding standard curve, based on the mean Ct value for each unknown sample. The relative quantities for D3R, D3nf, and tyrosine hydroxylase were normalized to the GAPDH value obtained from the same mouse.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, with Treatment (saline, NGB 2904, or amphetamine) and Time (6 or 24 hours) as main factors. Individual group differences were assessed with Fisher’s LSD tests (α=0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using GB Stat (Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Spring, MD).

3. Results

Ventral Striatum

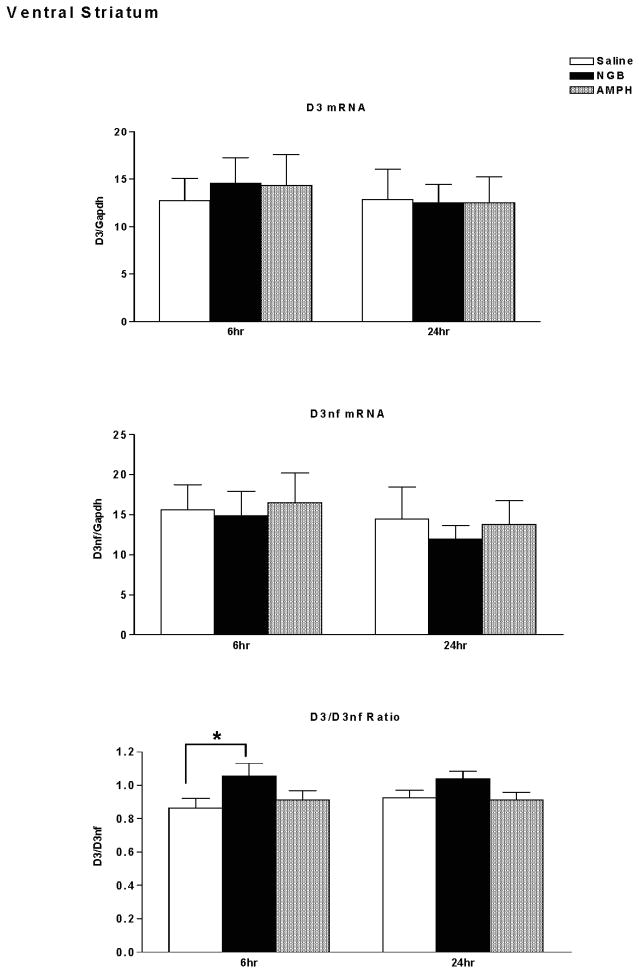

D3R and D3nf mRNA expression were determined in ventral striatum (nucleus accumbens and Islands of Calleja) of DBA/2J mice sacrificed 6 hours or 24 hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg). D3mRNA, D3nf mRNA, and the D3/D3nf mRNA expression ratio are shown in Figure 2. There were no significant differences in D3 mRNA expression following treatment with NGB 2904 or amphetamine relative to saline treated mice (Time, F(1,46)=0.33, p=0.570; Treatment, F(2,46)=0.04,p=0.959; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=0.09, p=0.910). Similarly, there were no significant differences in D3nf mRNA expression following treatment with NGB 2904 or amphetamine relative to saline treated mice (Time, F(1,46)=0.76, p=0.387; Treatment, F(2,46)=0.18,p=0.833; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=0.04, p=0.956).

Figure 2.

Dopamine D3 receptor/ GAPDH mRNA expression (top), D3nf/ GAPDH mRNA expression (middle), and D3R/D3nf mRNA ratio (lower) in ventral striatum (NAc/Islands of Calleja, IC). DBA/2J mice (n = 7–9 mice/group) were sacrificed for determination of mRNA expression 6 hours or twenty four hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg). Data are expressed as group mean ± S.E.M. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Saline.

Of interest, there was a significant effect of treatment on the D3/D3nf expression ratio (Time, F(1,46)=0.10, p=0.748; Treatment, F(2,46)=4.36, p=0.019; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=0.27, p=0.764). Post-hoc analysis with Fisher’s LSD (Protected t-Tests) demonstrated a significant increase in D3/D3nf ratio in the NGB 2904 treatment group at the 6-hour time point compared with the Saline group (p<0.05).

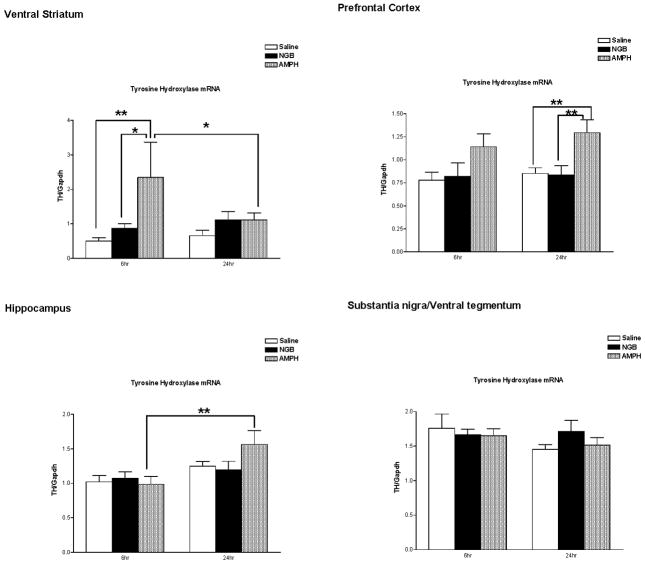

Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression in ventral striatum is shown in Figure 3 (upper left). There was a significant effect of treatment on TH mRNA expression in this brain region (Time, F(1,33)=0.59, p=0.447; Treatment, F(2,33)=3.51, p=0.042; Time × Treatment, F(2,33)=1.79, p= 0.183). Post-hoc analysis with Fisher’s LSD (Protected t-Tests) demonstrated significantly increased tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression in the amphetamine treatment group at the 6-hour time point compared with both the Saline (p<0.01) and NGB 2904 treatment groups (p<0.05), and compared to the 24-hour time point amphetamine treatment group (p<.05). In contrast, treatment with the D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904 did not have a significant effect on tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression relative to saline injection at either the 6-hour or 24-hour time points.

Figure 3.

Tyrosine hydroxylase/ GAPDH mRNA expression in ventral striatum (top left), prefrontal cortex (top right), hippocampus (lower left), and substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum (lower right). DBA/2J mice (n = 7–9 mice/group) were sacrificed for determination of mRNA expression 6 hours or twenty four hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg). Data are expressed as group mean ± S.E.M. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01.

Prefrontal cortex

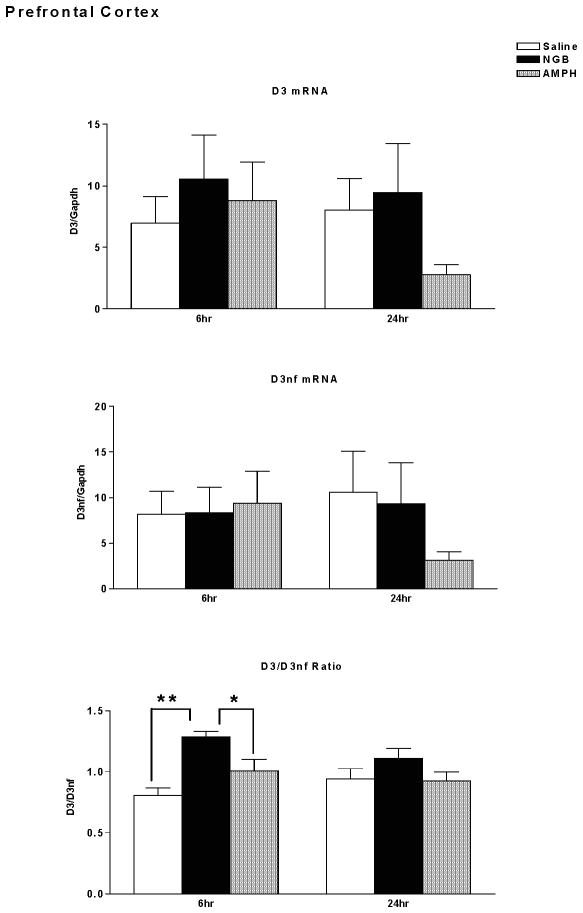

Dopamine D3 receptor mRNA, D3nf mRNA, and D3/D3nf mRNA expression ratio were determined in prefrontal cortex of mice sacrificed 6 hours or 24 hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg), as shown in Figure 4. There were no significant differences in D3 mRNA expression following treatment with NGB 2904 or amphetamine relative to saline treated mice (Time, F(1,44)=0.69, p=0.412; Treatment, F(2,44)=1.02, p=0.368; Time × Treatment, F(2,44)=0.74, p=0.481). The mean value of D3 mRNA expression decreased by 65% twenty-four hours following amphetamine treatment (saline group mean 8.033 +/− 2.6 vs. Amphetamine group mean 2.77 +/− 0.81 [mean +/− S.E.]), however this decrease was not statistically significant. There were also no significant differences in D3nf mRNA expression following treatment with NGB 2904 or amphetamine (AMPH) relative to saline treated mice (Time, F(1,44)=0.12, p=0.731; Treatment, F(2,44)=0.48, p=0.619; Time × Treatment, F(2,44)=0.96, p=0.392). The mean value of D3nf mRNA expression declined by 71% twenty-four hours following amphetamine treatment (saline group mean 10.6 +/− 4.5 vs. AMPH group mean 3.1 +/− 1.0 [mean +/− S.E.]), however this decrease was also not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Dopamine D3 receptor/ GAPDH mRNA expression (top), D3nf/ GAPDH mRNA expression (middle), and D3R/D3nf mRNA ratio (lower) in prefrontal cortex. DBA/2J mice (n = 7–9 mice/group) were sacrificed for determination of mRNA expression 6 hours or twenty four hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg). Data are expressed as group mean ± S.E.M. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. AMPH, **P ≤ 0.01 vs. Saline.

Of interest, the D3/D3nf expression ratio demonstrated a significant effect of treatment [Time, F(1,44)=0.45, p=0.505; Treatment, F(2,44)=9.80, p=0.0003; Time × Treatment, F(2,44)=2.27, p=0.115]. Post-hoc analysis with Fisher’s LSD (Protected t-Tests) demonstrated a significant increase in D3/D3nf ratio in the NGB 2904 treatment group at the 6-hour time point compared with both the Saline (p<0.01) and Amphetamine treatment groups (p<0.05).

Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression in prefrontal cortex is shown in Figure 3 (upper right). There was a significant effect of treatment on TH mRNA expression in this brain region [Time, F(1,53)= 0.567, p=0.455; Treatment, F(2,46)=6.00, p=0.0045; Time × Treatment, F(2,53)=0.131, p=0.877]. Post-hoc analyses demonstrated that tyrosine hydroxylase messenger RNA was elevated at the 24-hour time point following amphetamine treatment relative to both saline injection (p<.01) and NGB 2904 injection (p<.01) at the same 24- hour time point. The mean value of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression increased by 46% six hours following amphetamine treatment (saline group mean 0.780 +/− 0.084 vs. Amphetamine group mean 1.14 +/− 0.142 [mean +/− S.E.]), however this increase was not statistically significant. Similar to the findings in ventral striatum, treatment with the D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904 did not have a significant effect on prefrontal cortex tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression relative to saline injection at either the 6-hour or 24-hour time points.

Hippocampus

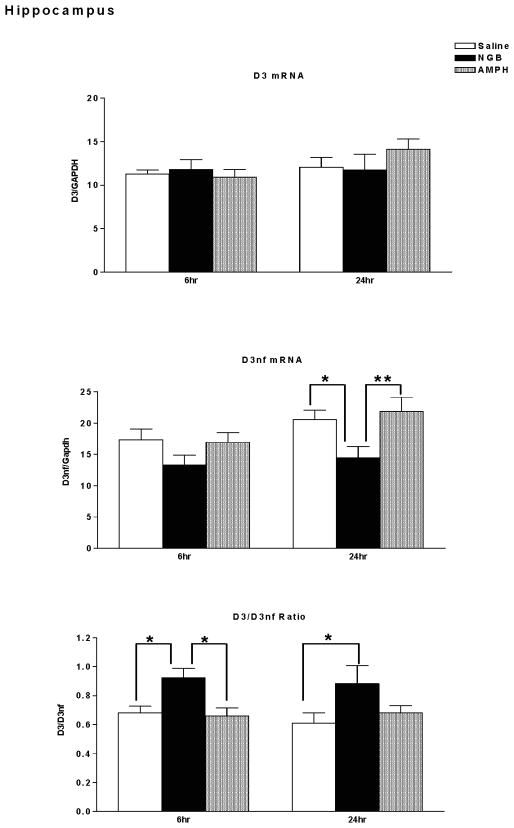

D3mRNA, D3nf mRNA, and D3/D3nf mRNA ratio in hippocampus of mice sacrificed 6 hours or 24 hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg) are shown in Figure 5. There were no significant differences in D3 mRNA expression following treatment with NGB 2904 or amphetamine relative to saline treated mice (Time, F(1,46)=1.76, p=0.191; Treatment, F(2,46)=0.30, p=0.739; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=1.03, p=0.366). In contrast, there were significant differences in hippocampal D3nf mRNA expression following treatment with NGB 2904 or amphetamine relative to saline treated mice (Time, F(1,46)=4.45, p=0.040; Treatment, F(2,46)=5.92, p=0.005; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=0.57, p=0.57). Post-hoc analyses with Fisher’s LSD (Protected t-Tests) demonstrated that 24 hours following treatment, D3nf mRNA expression is significantly decreased in the NGB 2904 treatment group compared with both Saline (p<0.05) and Amphetamine treatment groups (p<0.01).

Figure 5.

Dopamine D3 receptor/ GAPDH mRNA expression (top), D3nf/ GAPDH mRNA expression (middle), and D3R/D3nf mRNA ratio (lower) in hippocampus. DBA/2J mice (n = 7–9 mice/group) were sacrificed for determination of mRNA expression 6 hours or twenty four hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg). Data are expressed as group mean ± S.E.M. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01.

The D3/D3nf expression ratio also demonstrated a significant effect of treatment (Time, F(1,46)=0.24, p=0.629; Treatment, F(2,46)=7.25, p=0.0018; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=0.20, p=0.823). Post-hoc analysis with Fisher’s LSD (Protected t-Tests) demonstrate significant increases in D3/D3nf ratio in the NGB 2904 treatment group at the 6-hour time point compared with both Saline (p<0.05) and Amphetamine treatment groups (p<0.05). Twenty four hours following treatment, the D3/D3nf mRNA expression ratio is significantly increased in the NGB 2904 treatment group relative to the Saline treatment group(p<0.05).

Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression in hippocampus is shown in Figure 3 (lower left). There was a significant effect of time on TH mRNA expression in this brain region [Time, F(1,58)= 6.76, p=0.012; Treatment, F(2,58)=0.627, p=0.54; Time × Treatment, F(2,58)=1.34, p=0.269]. Post-hoc analyses demonstrated that tyrosine hydroxylase messenger RNA was elevated at the 24-hour time point following amphetamine treatment relative to the 6- hour amphetamine treatment group (p<.05). Treatment with the D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904 did not have a significant effect on tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression in hippocampus relative to saline injection at either the 6-hour or 24-hour time points.

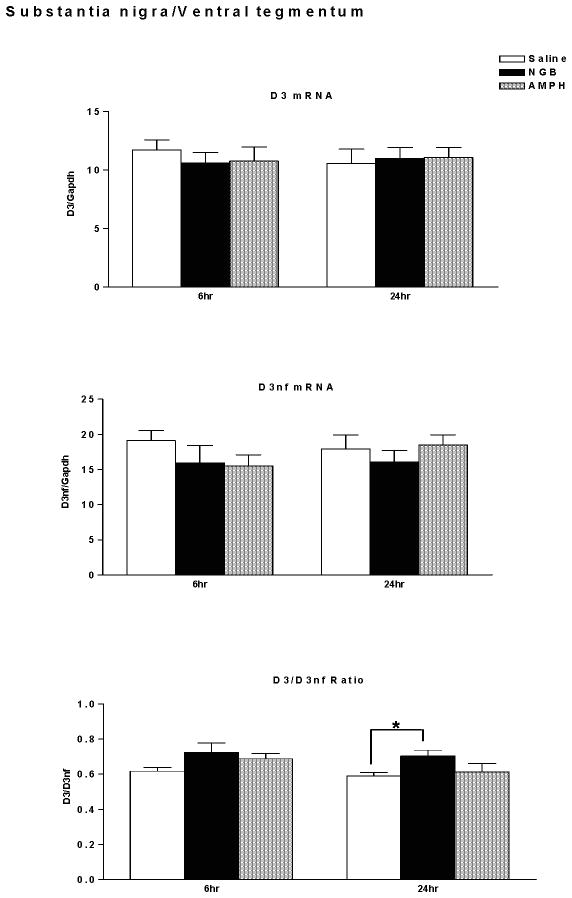

Midbrain (substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum)

D3R and D3nf mRNA expression were determined in midbrain (substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum) of mice sacrificed 6 hours or 24 hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg). D3mRNA, D3nf mRNA, and the ratio of D3/D3nf mRNA expression are shown in Figure 6. There were no significant differences in D3 mRNA expression following treatment with NGB 2904 or amphetamine relative to saline treated mice (Time, F(1,46)=0.03, p=0.861; Treatment, F(2,46)=0.06, p=0.944; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=0.38, p=0.685). Similarly, there were no significant differences in D3nf mRNA expression following treatment with NGB 2904 or amphetamine relative to saline treated mice (Time, F(1,46)=0.18, p=0.671; Treatment, F(2,46)=0.96, p=0.389; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=0.70, p=0.502). Of interest, the D3/D3nf ratio demonstrates a significant effect of treatment (Time, F(1,46)=1.70, p=0.198; Treatment, F(2,46)=4.21, p=0.021; Time × Treatment, F(2,46)=0.31, p=0.738). Post-hoc analysis with Fisher’s LSD (Protected t-Tests) demonstrated an increase in D3/D3nf ratio in the NGB 2904 group at the 24 hour time point compared with the Saline group (p<0.05).

Figure 6.

Dopamine D3 receptor/ GAPDH mRNA expression (top), D3nf/ GAPDH mRNA expression (middle), and D3R/D3nf mRNA ratio (lower) in substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum. DBA/2J mice (n = 7–9 mice/group) were sacrificed for determination of mRNA expression 6 hours or twenty four hours following treatment with saline, NGB 2904 (1 mg/kg), or amphetamine (10 mg/kg). Data are expressed as group mean ± S.E.M. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. Saline.

Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression in substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum is shown in Figure 3 (lower right). Surprisingly, neither treatment with amphetamine or NGB 2904 had a significant effect on tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression in substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum relative to saline injection at the 6-hour or 24-hour time points [Time, F(1,58)=1.74, p=0.19; Treatment, F(2,58)=0.412, p=0.66; Time × Treatment, F(2,58)=1.03, p=0.36].

A summary of the significant effects of NGB 2904 treatment on the ratio of D3/D3nf mRNA expression within different limbic brain regions is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of changes in D3/D3nf mRNA expression ratio following treatment with dopamine D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904. Single arrow indicates p <0.05 relative to saline pretreatment. Double arrow indicates p <0.01 relative to saline pretreatment. NC indicates no statistically significant change relative to saline pretreatment.

| brain region | Six hours | Twenty four hours |

|---|---|---|

| Ventral Striatum | ↑ | NC |

| Prefrontal Cortex | ↑↑ | NC |

| Hippocampus | ↑ | ↑ |

| Substantia nigra/Ventral tegmentum | NC | ↑ |

4. Discussion

The data presented above provide evidence for an adaptive response in D3 receptor isoform expression within specific regions of the limbic system in response to D3 receptor blockade with NGB 2904. Six hours following NGB 2904 treatment, the D3/D3nf ratio was increased in ventral striatum, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus (summarized in Table 1). Twenty-four hours following NGB 2904 treatment, the D3/D3nf ratio was persistently increased in hippocampus and substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum. The increased D3/D3nf ratio in hippocampus resulted primarily from decreased D3nf isoform expression. Our data is not able to distinguish the immediate effect of NGB 2904 antagonism from an adaptive response to dopamine D3 receptor blockade in other brain regions. It is therefore possible that changes observed in substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum at the twenty-four hour time point may result from adaptation to earlier D3 receptor blockade within the prefrontal cortex. D2/D3 receptors in prefrontal cortex inhibit the activity of glutamatergic efferents from prefrontal cortex to substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum (Harte and O’Connor, 2004). Blockade of prefrontal cortical D3 receptors could thereby increase glutamatergic input from prefrontal cortex to ventral tegmentum. Previous studies have demonstrated adaptive responses in ventral tegmentum neurons resulting from altered prefrontal cortical activity (Melis, Perra, Muntoni, Pillolla, Lutz, Marsicano, Di, V, Gessa, and Pistis, 2004). Further study is needed to elucidate the specific anatomic relationships and functions of D3 receptors in prefrontal cortex, and to test the validity of this hypothetical model.

We have previously suggested that adaptive down regulation of inhibitory dopamine D3 receptor function, which may be mediated by changes in alternative splicing, could account for the persistent long-term augmentation of behavioral sensitization observed following treatment with stimulant drugs including amphetamine (Richtand, Woods, Berger, and Strakowski, 2001;Richtand, Welge, Levant, Logue, Hayes, Pritchard, Geracioti, Coolen, and Berger, 2003;Richtand, 2006). It was therefore unexpected that we did not observe more robust changes in D3 receptor isoform expression following amphetamine treatment. D3 mRNA expression declined by 65% in prefrontal cortex, and D3nf mRNA expression decreased by 71%, twenty four hours following amphetamine treatment. These reductions did not reach the level of statistical significance, however, in part due to large individual differences in splice isoform mRNA expression within the prefrontal cortex. Additionally, the D3/D3nf mRNA expression ratio was not significantly altered in this brain region following amphetamine treatment.

The DBA/2J mouse strain chosen for this study may have contributed to the observed results. DBA/2J mice were chosen for study because previous work in our laboratory suggested DBA/2J mice display augmented dopamine D3 receptor function relative to C57BL/6J mice (McNamara, Levant, Taylor, Ahlbrand, Liu, Sullivan, Stanford, and Richtand, 2006). However, work in several laboratories has also shown that DBA/2J mice have a more limited adaptive response to stimulant drug administration than C57BL/6J mice (Puglisi-Allegra and Cabib, 1997;Orsini, Buchini, Piazza, Puglisi-Allegra, and Cabib, 2004). Further study is needed to elucidate the specific contribution of genetic background to adaptive changes in D3 receptor isoform expression in response to stimulant drug administration.

Tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis, is regulated at the levels of transcription, translation, and post-translationally by phosphorylation at multiple phosphorylation sites (Goldstein, 1995). Reports attempting to identify whether autoreceptors regulating dopamine synthesis are of the dopamine D2 and/or D3 subtype have observed contrasting results. Studies comparing wild-type and dopamine receptor knockout mice demonstrated a loss of autoreceptor inhibition of newly synthesized DA release in synaptosomes of D2 receptor knockout mice (L’hirondel, Cheramy, Godeheu, Artaud, Saiardi, Borrelli, and Glowinski, 1998), while autoreceptor function was comparable in wild-type and D3 receptor knockout mice (Koeltzow, Xu, Cooper, Hu, Tonegawa, Wolf, and White, 1998). Taken together, those data suggest that a significant D3 autoreceptor role regulating DA synthesis and release is unlikely. In contrast, another study observed elevated nucleus accumbens dopamine synthesis following dopamine D3 receptor antisense oligonucleotide administration, suggesting dopamine D3 autoreceptor influence of dopamine synthesis (Nissbrandt, Ekman, Eriksson, and Heilig, 1995). Studies using pharmacological approaches have also had contrasting results, concluding that autoreceptors regulating dopamine synthesis are of the D3 subtype (Meller, Bohmaker, Goldstein, and Basham, 1993), or that autoreceptors controlling dopamine release are of the D2 subtype (Fedele, Fontana, Munari, Cossu, and Raiteri, 1999). Because of improved technology allowing more sensitive and selective mRNA assays using semi-quantitative RT-PCR, it was therefore of interest to identify the effects of D3 receptor blockade by NGB 2904, and indirect dopamine receptor stimulation by amphetamine, on tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression. A previous study observed increased TH mRNA expression in substantia nigra 8 hours following acute administration of the mixed dopamine D2/D3 receptor antagonist haloperidol (Stork, Hashimoto, and Obata, 1994). In contrast, D3 receptor blockade by NGB 2904 did not have a measurable effect on tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression levels in any brain region in our study. Our findings suggest that D3 receptor involvement in autoreceptor regulation of dopamine synthesis does not extend to the level of regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression in cell body (SN/VTA) or terminal field regions.

In contrast to the lack of effect of D3 receptor blockade on TH mRNA levels, indirect dopamine receptor stimulation with amphetamine elevates tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in dopamine terminal field regions. Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression was elevated 5-fold in ventral striatum six hours following amphetamine administration; message levels declined back to baseline by 24 hours following treatment. In prefrontal cortex, tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels trended upwards at six hours, and were significantly elevated 24 hours following treatment. Tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels were also elevated in hippocampus 24 hours following amphetamine administration. In contrast, no appreciable change in tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA expression was observed in the dopamine cell body regions within the substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum. While the increase in tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels in terminal fields, rather than the cell body region where mRNA is synthesized, was unexpected, earlier studies have previously described axonal transport of processed tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA to specific targets for local protein synthesis (Melia, Trembleau, Oddi, Sanna, and Bloom, 1994). Our extension of these earlier findings is in part the result of greatly improved sensitivity and selectivity of semi-quantitative RT-PCR mRNA assays which allows reliable quantification of mRNA levels which were until recently below limits of detection. In combination, our current findings suggest regulated expression of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in pre-synaptic terminal field regions, and provide direct experimental support for the model that mRNA expression can be locally controlled in adaptation to synaptic activity (Tiedge, Bloom, and Richter, 1999;Wang and Tiedge, 2004;Schuman, Dynes, and Steward, 2006).

In summary, our data provide evidence for an adaptive response to D3 receptor blockade involving changes in D3 dopamine receptor isoform mRNA expression. These changes include a direct effect on post-synaptic mRNA expression in ventral striatum, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus, and suggest that a compensatory adaptation may occur in pre-synaptic D3 receptor isoform expression within substantia nigra/ventral tegmentum in response to adaptive changes in other brain regions. In combination, these findings provide evidence for an adaptive response to altered D3 dopamine receptor stimulation involving changes in D3 receptor alternative splicing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service, NIDA R01 16778 (NMR), NIMH R21MH083192 (NMR), and by NIDA- intramural research program, National Institute of Health (AHN).

Abbreviations

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

Reference List

- Elmhurst JL, Xie Z, O’Dowd BF, George SR. The splice variant D3nf reduces ligand binding to the D3 dopamine receptor: evidence for heterooligomerization. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;80:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedele E, Fontana G, Munari C, Cossu M, Raiteri M. Native human neocortex release-regulating dopamine D2 type autoreceptors are dopamine D2 subtype. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:2351–2358. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishburn CS, Belleli D, David C, Carmon S, Fuchs S. A novel short isoform of the D3 dopamine receptor generated by alternative splicing in the third cytoplasmic loop. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5872–5878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein M. Long- and short-term regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, editors. Psychopharmacology: the Fourth Generation of Progress. New York: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory H, Taylor CL, Hopkins CR. Luteinizing hormone release from dissociated pituitary cells by dimerization of occupied LHRH receptors. Nature. 1982;300:269–271. doi: 10.1038/300269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundt P, Carlson EE, Cao J, Bennett CJ, McElveen E, Taylor M, Luedtke RR, Newman AH. Novel heterocyclic trans olefin analogues of N-{4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]butyl}arylcarboxamides as selective probes with high affinity for the dopamine D3 receptor. J Med Chem. 2005;48:839–848. doi: 10.1021/jm049465g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte M, O’Connor WT. Evidence for a differential medial prefrontal dopamine D1 and D2 receptor regulation of local and ventral tegmental glutamate and GABA release: a dual probe microdialysis study in the awake rat. Brain Res. 2004;1017:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn CR, Baird KL, Flier JS, Grunfeld C, Harmon JT, Harrison LC, Karlsson FA, Kasuga M, King GL, Lang UC, Podskalny JM, Van Obberghen E. Insulin receptors, receptor antibodies, and the mechanism of insulin action. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1981;37:477–538. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571137-1.50015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpa KD, Lin R, Kabbani N, Levenson R. The dopamine D3 receptor interacts with itself and the truncated D3 splice variant d3nf: D3-D3nf interaction causes mislocalization of D3 receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:677–683. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeltzow TE, Xu M, Cooper DC, Hu XT, Tonegawa S, Wolf ME, White FJ. Alterations in dopamine release but not dopamine autoreceptor function in dopamine D3 receptor mutant mice. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2231–2238. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L’hirondel M, Cheramy A, Godeheu G, Artaud F, Saiardi A, Borrelli E, Glowinski J. Lack of autoreceptor-mediated inhibitory control of dopamine release in striatal synaptosomes of D2 receptor-deficient mice. Brain Res. 1998;792:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Bergson C, Levenson R, Schmauss C. On the origin of mRNA encoding the truncated dopamine D3-type receptor D3nf and detection of D3nf-like immunoreactivity in human brain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29220–29226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Levant B, Taylor B, Ahlbrand R, Liu Y, Sullivan JR, Stanford K, Richtand NM. C57BL/6J Mice Exhibit Reduced Dopamine D3 Receptor-Mediated Inhibitory Function Relative to DBA/2J Mice. Neuroscience. 2006;143:141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melia KR, Trembleau A, Oddi R, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Detection and regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA in catecholaminergic terminal fields: possible axonal compartmentalization. Exp Neurol. 1994;130:394–406. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis M, Perra S, Muntoni AL, Pillolla G, Lutz B, Marsicano G, Di MV, Gessa GL, Pistis M. Prefrontal cortex stimulation induces 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol-mediated suppression of excitation in dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10707–10715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3502-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller E, Bohmaker K, Goldstein M, Basham DA. Evidence that striatal synthesis-inhibiting autoreceptors are dopamine D3 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;249:R5–R6. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90674-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AH, Cao J, Bennett CJ, Robarge MJ, Freeman RA, Luedtke RR. N-(4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]butyl, butenyl and butynyl)arylcarboxamides as novel dopamine D(3) receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:2179–2183. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimchinsky EA, Hof PR, Janssen WGM, Morrison JH, Schmauss C. Expression of dopamine D3 receptor dimers and tetramers in brain and in transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29229–29237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissbrandt H, Ekman A, Eriksson E, Heilig M. Dopamine D3 receptor antisense influences dopamine synthesis in rat brain. Neuroreport. 1995;6:573–576. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199502000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara CM, Uhland-Smith A, O’Malley KL, Todd RD. Inhibition of dopamine synthesis by dopamine D2 and D3 but not D4 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:186–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini C, Buchini F, Piazza PV, Puglisi-Allegra S, Cabib S. Susceptibility to amphetamine-induced place preference is predicted by locomotor response to novelty and amphetamine in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;172:264–270. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1647-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard LM, Logue AD, Taylor B, Ahlbrand RL, Welge JA, Tang Y, Sharp FR, Richtand NM. Relative Expression of D3 Dopamine Receptor and Alternative Splice Variant D3nf mRNA in High and Low Responders to Novelty. Brain Res Bull. 2006;70:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard LM, Newman AH, McNamara RK, Logue AD, Taylor B, Welge JA, Xu M, Zhang J, Richtand NM. The dopamine D3 receptor antagonist NGB 2904 increases spontaneous and amphetamine-stimulated locomotion. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi-Allegra S, Cabib S. Psychopharmacology of dopamine: the contribution of comparative studies in inbred strains of mice. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;51:637–661. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtand NM. Behavioral Sensitization, Alternative Splicing, and D3 Dopamine Receptor-Mediated Inhibitory Function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2368–2375. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtand NM, Welge JA, Levant B, Logue AD, Hayes S, Pritchard LM, Geracioti TD, Coolen LM, Berger SP. Altered behavioral response to dopamine D3 receptor agonists 7-OH-DPAT and PD 128907 following repetitive amphetamine administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1422–1432. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richtand NM, Woods SC, Berger SP, Strakowski SM. D3 dopamine receptor, behavioral sensitization, and psychosis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:427–443. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(01)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmauss C. Enhanced cleavage of an atypical intron of dopamine D3-receptor pre-mRNA in chronic schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7902–7909. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07902.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmauss C, Haroutunian V, Davis KL, Davidson M. Selective loss of dopamine D3-type receptor mRNA expression in parietal and motor cortices of patients with chronic schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8942–8946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman EM, Dynes JL, Steward O. Synaptic regulation of translation of dendritic mRNAs. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7143–7146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1796-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Behavioral pharmacology of amphetamine. In: Cho AK, Segal DS, editors. Amphetamine and its analogues: pharmacology, toxicology, and abuse. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LA, Roberts JL, Sealfon SC. Alternative transcripts of the rat and human dopamine D3 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;180:1031–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork O, Hashimoto T, Obata K. Haloperidol activates tyrosine hydroxylase gene-expression in the rat substantia nigra, pars reticulata. Brain Res. 1994;633:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91542-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedge H, Bloom FE, Richter D. RNA, whither goest thou? Science. 1999;283:186–187. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Tiedge H. Translational control at the synapse. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:456–466. doi: 10.1177/1073858404265866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Chen X, Brodbeck R, Primus R, Braun J, Wasley JW, Thurkauf A. NGB 2904 and NGB 2849: two highly selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8:2715–2718. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]