Abstract

Atherosclerosis, driven by inflamed lipid-laden lesions, can occlude the coronary arteries and lead to myocardial infarction. This chronic disease is a major and expensive health burden. However, the body is able to mobilize and excrete cholesterol and other lipids, thus preventing atherosclerosis by a process termed reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). Insight into the mechanism of RCT has been gained by the study of two rare syndromes caused by the mutation of ABC transporter loci. In Tangier Disease, loss of ABCA1 prevents cells from exporting cholesterol and phospholipid, thus resulting in the build-up of cholesterol in the peripheral tissues and a loss of circulating HDL. Consistent with HDL being an athero-protective particle, Tangier patients are more prone to develop atherosclerosis. Likewise, sitosterolemia is another inherited syndrome associated with premature atherosclerosis. Here mutations in either the ABCG5 or G8 loci, prevents hepatocytes and enterocytes from excreting cholesterol and plant sterols, including sitosterol, into the bile and intestinal lumen. Thus, ABCG5 and G8, which from a heterodimer, constitute a transporter that excretes cholesterol and dietary sterols back into the gut, while ABCA1 functions to export excess cell cholesterol and phospholipid during the biogenesis of HDL. Interestingly, a third protein, ABCG1, that has been shown to have anti-atherosclerotic activity in mice, may also act to transfer cholesterol to mature HDL particles. Here we review the relationship between the lipid transport activities of these proteins and their anti-atherosclerotic effect, particularly how they may reduce inflammatory signaling pathways. Of particular interest are recent reports that indicate both ABCA1 and ABCG1 modulate cell surface cholesterol levels and inhibit its partitioning into lipid rafts. Given lipid rafts may provide platforms for innate immune receptors to respond to inflammatory signals, it follows that loss of ABCA1 and ABCG1 by increasing raft content will increase signaling through these receptors, as has been experimentally demonstrated. Moreover, additional reports indicate ABCA1, and possibly SR-BI, another HDL receptor, may directly act as anti-inflammatory receptors independent of their lipid transport activities. Finally, we give an update on the progress and pitfalls of therapeutic approaches that seek to stimulate the flux of lipids through the RCT pathway.

Keywords: ABCA1, ABCG1, ABCG5, ABCG8, Tangier Disease, Sitosterolemia, Atherosclerosis, Inflammation

Introduction

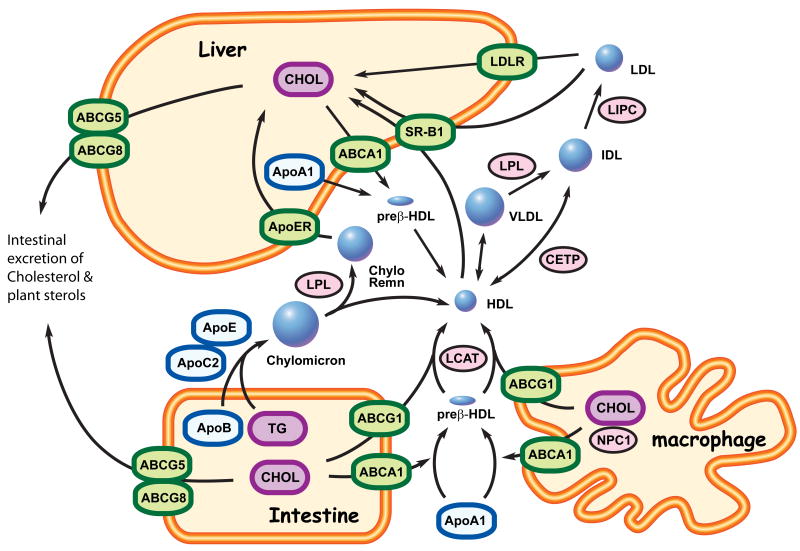

The human body requires cholesterol and other lipids for cell growth, axon myelination, hormone production, biogenesis of lung surfactant, and formation of the skin-barrier [1-4]. These lipids, acquired from the diet or endogenously synthesized, are packaged into lipoprotein particles that allow for their transport through the hydrophilic environment of the blood and tissue lymph. Lipoproteins and a coevolved network of enzymes, transporters and signaling processes that control particle generation, trafficking and uptake allows the body to store and mobilize lipids in response to altered metabolic demand for these essential cellular constituents. Mutation of genes that comprise this network cause distinct dyslipidemias, a classic example being familial hypercholesterolemia caused by mutation of the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR, Fig. 1) [5].

Figure 1. ABC transporters and lipoprotein metabolism.

Cells and organisms use lipoproteins to move hydrophobic lipid molecules, which are not water soluble, through the aqueous environment of the blood and tissue lymph. Lipoprotein particles are defined by their complement of associated apolipoproteins and their content of cholesterol (CHOL), triglyceride (TG) and phospholipid that each particle carries. This protein and lipid content defines the particles buoyant density and subdivides them into 4 major classes: High Density Lipoprotein (HDL), Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), Very Low Density Lipoprotein (VLDL), and chylomicrons. HDL is form by the transfer of cholesterol and phospholipids onto apolipoproteinA-I (apoA-I) to generate preβ-HDL. This process is catalyzed by the ABCA1 transporter, which is expressed in the peripheral tissues, intestine and liver. Lysolecithin Cholesterol Acyltransferase (LCAT) then esterifies the cholesterol in nascent preβ-HDL as part of the process that generates mature spherical HDL. ABCG1 is another ABC transporter that is able to load more cholesterol onto mature HDL from peripheral tissues and along with ABCA1 is important in allowing macrophages to efflux artery wall cholesterol, which prevents atherosclerotic vascular disease. HDL cholesteryl-esters are taken up by scavenger receptor BI (SRBI) in liver and after hydrolysis the resulting free cholesterol is metabolized to bile acids (BA). The bile acids, along with more free cholesterol, are excreted into the digestive tract via biliary secretion in a process that again utilizes ABC transporters (ABCG5/8, ABCB11, ABCB4, ABCC2). Conversely, in the small intestine, absorbed dietary fatty acids are converted into triglycerides (TG) and are packaged and secreted into the bloodstream as chylomicrons, a lipoprotein particle rich in TG and apoB-48. TG in this lipoprotein is rapidly hydrolyzed into free fatty acids by lipoprotein lipase (LPL), leading to the formation of chylomicron remnants (Chylo Remn), which are taken up by the liver via the apoE receptor (ApoER). Dietary cholesterol is also packaged into HDL particles by the action of ABCA1 and ABCG1, and as HDL circulates there is an increase in its apoC2 and apoE ratio due to apolipoprotein exchange between HDL and VLDL. Cholesteryl ester from HDL is also transferred to VLDL remnant particles (IDL) by the action of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP). IDL looses most of apolipoprotein except apoB and is converted to LDL by the action of hepatic lipase (LIPC). Finally, liver and other tissues take up LDL by an endocytotic process that involves the LDL receptor (LDLR). In humans, mutation of the LDL receptor leads to elevated plasma LDL levels (hypercholesterolemia), whereas mutation of ABCA1 ablates circulating HDL (Tangier disease). Mutations of ABCG5 or ABCG8 leads to the sitosterolemia, which is characterized by elevated levels of circulating cholesterol and dietary plant sterols.

Here we review two additional rare inherited dyslipidemias that are caused by mutation of loci encoding members of the ABC transporter superfamily. These proteins, as opposed to the LDL receptor, allow cells to export cholesterol and phospholipid. In Tangier disease mutations in ABCA1 prevent cells from moving cholesterol and phospholipid onto apolipoproteinA-I (apoA-I). This ABCA1-dependent lipid transfer to apoA-I is the rate-limiting step in the biogenesis of high density lipoprotein (HDL, Fig. 1). Thus, Tangier patients have little or no circulating HDL, and cells that experience large lipid fluxes, such as macrophages, accumulate cholesterol resulting in the formation of ‘foam cells’, an early hallmark of atherosclerosis. These cells are a prominent feature of the Tangier phenotype and there is significant interest in assessing whether pharmacologic stimulation of ABCA1-dependent lipid efflux may be a viable approach to raise HDL and prevent atherosclerosis.

Although ABCA1 is critical for cellular cholesterol efflux, contrary to expectations, the transporter does not play a critical role in the ability of the liver to excrete cholesterol into the bile, thus eliminating it from the body. However, analysis of sitosterolemia patients, who have abnormally high levels of plant sterols in their tissues, has shown that two ABCG transporters (ABCG5 and G8) that form a heterodimer are essential for elimination of cholesterol and other sterols from the body. Consistent with a direct role in excreting sterol from the body, the ABCG5/G8 transporter localizes to apical membrane domains of hepatocytes that form the bile canaliculus. In contrast, ABCA1 localizes to the basolateral domains of hepatocytes that are in intimate contact with the sinusoidal vasculature as expected for a transporter that moves cholesterol onto the apolipoproteins of HDL.

Thus, analysis of Tangier and sitosterolemia patients respectively, has revealed transporters that control mobilization of cholesterol into the plasma compartment and excretion of cholesterol and other dietary sterols back into the digestive compartment. These findings have given mechanistic insight into the first and last steps of a physiologic process termed reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), which is hypothesized to mobilize cholesterol from the peripheral tissues to the intestine for excretion. Nevertheless, many questions remain regarding the lipid transport activities of these molecules and how RCT prevents the formation of atherosclerotic lesions. In this regard, the activity of a third transporter, ABCG1 is of interest, since it may participate in an intermediate RCT step i.e. transfer of cholesterol to mature HDL particles. Moreover, its activity in concert with that of ABCA1 appears to be important in suppressing macrophage inflammatory cytokine secretion. Given that the activity of these ABC transporters suppresses atherosclerosis, a variety of therapeutic approaches are being developed to stimulate lipid flux through the RCT pathway, but as discussed the efficacy and safety of these approaches remains to be proven.

Tangier Disease, ABCA1 cholesterol efflux and HDL biogenesis

The Tangier phenotype

Tangier disease (OMIM 2054000) is a rare dyslipidemia first described by Donald Fredrickson et al in 1961 [6]. The syndrome takes its name from Tangier Island, located in Chesapeake Bay, Virginia (USA), home of the initial proband. This individual, a boy of five years, needed a tonsillectomy to relieve swallowing difficulties due to grossly enlarged yellowish tonsils. Histological study of these unique tonsils showed they were massively infiltrated with foam cells engorged with lipid that stained positive for cholesterol. Biochemical analysis of the tonsils confirmed a nearly 50-fold increase in cholesterol content, especially cholesterol esters. Correlated with this profound build-up of cholesterol esters, principally in tissues rich in reticular endothelial cells, lipoprotein analysis of the Tangier kindred and distinct kindreds in Kentucky and Missouri showed that these individuals had a near complete absence of circulating HDL (<1-2 mg HDL cholesterol/dl plasma). Moreover, close relatives of the affected had below normal HDL levels (<30-33 mg HDL cholesterol/dl plasma), an inheritance consistent with transmission of a single mutated allele causing an autosomal recessive phenotype [7]. Study of the major HDL apolipoproteins (apoA-I and apoA-II) further associated the Tangier phenotype with the hypercatabolism of circulating apoA-I, although this was not due to mutation of the apoA-I loci [8-14]. Subsequent studies indicated that unlike normal fibroblasts, which export cholesterol to lipid poor apoA-I, Tangier fibroblasts failed to mobilize intracellular stores of cholesterol ester to apoA-I [15-17]. This, along with the lost of high affinity cellular binding sites for apoA-I in Tangier fibroblasts, suggested that the mutated gene may encode a receptor for apoA-I [15]. In 1998, progress in mapping the mutated loci was reported by Rust et al using a linkage exclusion strategy that narrowed the Tangier lesion to chromosome 9q31 [18]. Soon after in 1999, four groups identified mutations in a gene at position 9q31.1 encoding an ABC transporter, now called ABCA1, whose inheritance correlated with the Tangier phenotype [19-22].

The ABCA1 cholesterol efflux mechanism

Subsequent to Tangier disease being associated with mutations in ABCA1, investigators focused on describing the mechanism by which this large transmembrane protein mediates cholesterol efflux and the biogenesis of HDL. As demonstrated by chemical cross-linking approaches, ABCA1 and apoA-I were found to form a close molecular complex (< 3 angstroms) that is saturable and of high affinity (Kd=7 nmolar) [23-27]. Analysis of naturally occurring ABCA1 Tangier mutations further indicated that formation of this complex is necessary but not sufficient for cellular cholesterol efflux to occur. That this is the case is indicated by the observation that the majority, but not all, of the described ABCA1 mutations disrupt both complex formation and cholesterol efflux. The exception to this behavior is the activity of the ABCA1 (W590S) missense mutant that is still able to bind and release apoA-I back into the media but fails to transfer lipid to the released apoA-I [24, 25, 28, 29]. The behavior of this mutant is consistent with a direct efflux mechanism wherein ABCA1 first binds apoA-I, resulting in subsequent transfer of lipid to the bound apoA-I, which is then released from the cell, with the latter steps presumably still occurring within the context of the high affinity complex. However, other more indirect models have also been proposed to account for data that indicates ABCA1 activity modifies cellular lipid domains in the absence of apoA-I and that these lipid domains may represent a larger capacity but lower affinity cellular binding site for apoA-I that is not closely associated with ABCA1, as assessed by chemical cross-linking [30-32]. Here, it is proposed that the high affinity complex leads to the insertion of apoA-I into the membrane bilayer, but that lipid transfer to apoA-I and its dissociation from the membrane does not occurs within the context of the ABCA1/apoA-I protein complex [33]. It is further proposed that this occurs through an intrinsic biophysical property of apoA-I to solubilize lipids out of membrane bilayers, a property that can be demonstrated with purified lipid free apoA-I and multilamellar vesicles, and that ABCA1 possesses a translocase activity that moves phospholipids to exterior leaflet of the plasma membrane causing local curvature strain that triggers this apoA-I solublization step [33]. That ABCA1 may possess such an activity has been suggested by immuno-gold electron micrographs showing clusters of anti-apoA-I antibodies binding to cell surface protrusions of cells induced to express ABCA1 [33, 34]. Additional studies have shown that independent of its interaction with apoA-I, ABCA1 expression decreases the lipid raft content in the plasma membrane and increases the sensitivity of cell surface cholesterol to oxidation by cholesterol oxidase [32]. These results suggest ABCA1 may have an intrinsic transport activity driven by its ability to hydrolyze ATP that acts to partition cholesterol into more membrane fluid domains at the cell surface. However, detailed measurements of transbilayer phospholipid movement in Tangier fibroblasts and Abca1-/- mouse macrophages found little evidence that this ability to alter the raft content of cells was due to a phospholipid translocase activity [35, 36]. Thus, although it is clear that ABCA1 can form a molecular complex with apoA-I that is tightly associated with the ability of ABCA1 to stimulate apoA-I dependent lipid efflux, the molecular details of how formation of this complex relates to the release of lipid rich apoA-I from the cell surface is in need of clarification.

The complexity of the apoA-I release mechanism is further illustrated by reports that have suggested both apoA-I and ABCA1 may participate in a retro-endocytosis cycle. Takahashi and Smith first reported in 1999 that macrophages internalize bound apoA-I and resecrete the endocytosed apoA-I after it has picked up cholesterol and phospholipid [37]. Subsequently, Neufeld et al using an ABCA1-GFP fusion protein showed that the transporter was actively endocytosed [38, 39], and Chen et al reported that deletion of the ABCA1 PEST motif impaired the trafficking of cell surface ABCA1 to the late endosome [40]. The failure of the ABCA1-PEST mutant to reach the late endosomes was associated with efflux impairment when cholesterol originated from the lysosome, but not when the cholesterol was derived from the cell surface. These observations and those of Hassan et al that indicate cell binding of apoA-I stimulates the endocytosis of ABCA1 has led to a proposed two compartment efflux model where ABCA1 efflux to apoA-I occurs at both the cell surface and in a late endosomal compartment [41]. However, subsequent studies by Denis et al, and Faulkner et al that have quantitated efflux from the endocytic pathway indicated it represented less than 5% of the total cellular efflux capacity and that a large fraction of the resecreted apoA-I is degraded [42, 43]. These quantitative studies, however, have the caveat that the radiolabeled cholesterol used to measure efflux was delivered directly to the plasma membrane. It maybe that if the radiolabel cholesterol is delivered in modified LDL particles to the lysosomes by scavenger receptors the quantitative importance of the endocytic efflux compartment may increase. In this regard studies using primary macrophages from Abca1-/- mice should be particularly informative since this would represent a more physiologically relevant cell model compared to the over-expression studies that have been used to make many of the observations cited above. Moreover, since ABCA1 activity has been reported to interact a number of cytoplasmic factors that mediate membrane and cytoskeletal dynamics, its effect on apoA-I trafficking may be secondary to perturbations on the vesicle trafficking machinery [44-55].

ABCA1, HDL and atherosclerosis

The identification of ABCA1 as a rate-limiting factor in HDL biogenesis and the inverse correlation of HDL with CVD, suggested that loss of ABCA1 function would increase atherosclerosis whereas increased ABCA1 activity would inhibit atherosclerosis. Early studies assessing the incidence of CVD in the Tangier kindreds supported this hypothesis with homozygous null carriers of age 35 to 65 years displaying a 46% incidence of CVD and heterozygous individuals displaying a 26% incidence compared to the 4% incidence in controls [56, 57]. Subsequent study of individuals heterozygous for ABCA1 mutations confirmed a threefold increased risk of CVD [58]. However, given the small number of individuals assessed in these studies it was unclear whether alterations in ABCA1 activity modulate HDL levels in the general population. That this is the case has been supported by a series of genome-wide studies that have consistently identified polymorphisms in the ABCA1 loci as a significant determinant of HDL cholesterol in the general population [59-61]. However, whether these more common promoter and missense polymorphisms in ABCA1 associate with altered risk of CVD is less clear. Smaller studies have found risk associations [62-64] [65, 66], while the larger meta-analysis and two replication studies did not report a significant correlation between ABCA1 polymorphisms and CVD risk [61, 67, 68]. Because Frikke-Schmitdt et al found that after correction for age and other CVD risk factors, ABCA1 polymorphisms were still associated with lower HDL levels but not with elevated triglycerides, which has been seen in Tangier patients, they suggest this isolated HDL lowering effect caused by partial loss of ABCA1 function does not alone increased the risk of CVD [67]. Why complete, but not partial, loss of ABCA1 function has been associated with hypertriglyceridemia remains to be resolved but it may have to do with the role that liver ABCA1 plays in suppressing hepatic VLDL secretion [69].

Studies in mice where the Abca1 locus is either deleted or over-expressed generally support the hypothesis that ABCA1 by maintaining circulating HDL levels and cellular cholesterol efflux significantly prevents atherosclerosis [70-73]. The most recent of these have used tissue specific knockouts of the Abca1 locus to assess the respective roles that liver and macrophage ABCA1 plays in preventing atherosclerosis [74]. This work has confirmed the importance of liver ABCA1 efflux activity in maintaining HLD levels and protecting against atherosclerosis. However, the macrophage specific deletion of ABCA1 was not found to have a strong impact on lesion burden, a result that contrasted a series of studies that found mice receiving Abca1-/- bone marrow transplants had significantly worse atherosclerosis [73, 75]. Whether this indicates ABCA1 operates at the level of the vessel wall to prevent atherosclerosis in the other immune compartments, such as dendritic cells and lymphocytes, remains to be investigated, but as discussed below, the results are of interest since ABCA1 and ABCG1 also modulate other immune functions such as the secretion of inflammatory cytokines and T cell proliferation.

Sitosterolemia, ABCG5/G8 and Dietary Sterol Excretion

The Sitosterolemia phenotype

Like Tangier disease, sitosterolemia (or phytosterolemia) (OMIM 210250) is a rare, autosomal recessive lipid disorder first described in 1974 by Bhattacharyya and Connor [76]. Characterized by markedly increased levels of dietary sterols in the body, including the plant sterol sitosterol, the syndrome also associates with xanthoma development, hypercholesterolemia and premature coronary heart disease (notably myocardial infarction) [77-81]. Studies on sitosterolemia patients reveal up to a 12 fold increase in plant sterol absorption and up to a 100 fold increase in plasma and tissue plant sterol levels [82, 83]. Along with other dietary sterols, sitosterolemia patients absorb a greater fraction of dietary cholesterol and excrete less cholesterol into the bile as compared with normal subjects, resulting in a hypercholesterolemia with elevated apolipoprotein B levels but with reduced hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis [84-87]. Unlike other hyperlipidemias, however, sterol dietary restriction or treatment with bile acid resins reduced circulating sterol levels in sitosterolemic individuals [88, 89].

The sitosterolemia lesion was first mapped to a locus on human chromosome 2p21, between microsatellite markers D2S2294 and D2S2298 by Patel et al in 1998 [90]. In 2000, Berge et al confirmed this association by showing that mutation of either of two genes in this region (encoding ABC transporters ABCG5 or ABCG8), results in sitosterolemia [91]. Subsequently, Patel et al. showed that the ABCG5 and ABCG8 genes contain 13 exons each and are arranged in a head-to-head configuration on chromosome 2p21, with only 140 bases separating their first exons [92, 93]. Like ABCA1, the ABCG5/G8 locus is transcriptionally induced by liver X receptors (LXR) in response to increased cellular oxysterol content [94]. However, unlike the basolateral localization of ABCA1 [95-98], ABCG5 and ABCG8 are localized in the apical brush border membrane of enterocytes and the canalicular membrane of hepatocytes [99, 100].

The ABCG5/8 sterol secretion mechanism

The ABCG5 and G8 transporters are structurally distinct from ABCA1. They are half transporters that contain one 6 transmembrane domain and one ATP binding cassette as compared to ABCA1 which is a full transporter with two 6-transmembrane domain cassettes and two ATP binding cassettes encoded in a single open reading frame. However, ABCG5 and G8 heterodimerize, allowing for the trafficking of the transporter to the apical membranes of hepatocytes where it mediates the selective secretion of sterols (but not phospholipids) into the bile [101]. Likewise, expression of the ABCG5/G8 transporter at the apical membranes of enterocytes in the intestinal brush border also functions to stimulate sterol secretion into the intestinal lumen. Mutational analysis has shown a functional asymmetry between the G5 and G8 ATP binding domains wherein mutation of the G5 Walker A and B motifs but not the G8 domain disrupts sterol transport function [102]. Interestingly, arginine substitution of the lysine residue of the G5 subunit Walker A motif abolished cholesterol transport but preserved biliary plant sterol transport. These results suggest alterations in the structure of G5 nucleotide binding domain possibly mediated by the hydrolysis of ATP may transmit conformation changes to the transmembrane domains, thus giving the heterodimer an ability to discriminate between cholesterol and other sterol substrates during the transport cycle.

ABCG5/G8 transport and atherosclerosis

Early studies of sitosterolemia patients indicated that they were prone to early and severe atherosclerosis, but unlike familial hypercholesterolemia or Tangier disease, this phenotype was not associated with profound changes in lipoprotein cholesterol levels [77-81]. Thus, it was suggested that the more dramatic elevation of plant sterols seen in these individuals may represent an independent risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis [103, 104]. The PROCAM study found that elevations in sitosterol concentrations and the sitosterol/cholesterol ratio were associated with an increased occurrence of major coronary events in men at high global risk of coronary heart disease [105]. Moreover, over-expressing ABCG5 and ABCG8 in an atherogenic Ldlr-/- mouse model attenuated diet-induced atherosclerosis in association with reduced liver and plasma cholesterol levels [106-108]. However, a study by Wilund et al did not find an association between plant sterol levels and atherosclerosis in the general population and further concluded that mice lacking the ABCG5/G8 transport function were also not more prone to atherosclerosis [109]. Similarly, Silbernagel et al concluded that although higher levels of dietary cholesterol absorption modestly correlated with increased coronary artery disease, increased plant sterol adsorption was not [110]. Thus, although sitosterolemia patients exhibit severe premature atherosclerosis, loss of ABCG5/8 transport function in mice has not unequivocally recapitulated this phenotype. Similarly, although larger genome wide studies in humans has linked ABCG5 and G8 polymorphisms to variation in dietary cholesterol adsorption, total plasma cholesterol levels and the incidence of gallstones, these studies have not clearly linked the ABCG5 and G8 transporters to the risk of cardiovascular disease in the general population [111, 112].

ABCG1, HDL and anti-inflammatory properties of RCT

That expression of ABCA1 and the ABCG5/8 transporter are transcriptionally induced by LXR nuclear hormone receptors suggests that their function is integrated into a larger genetic network that maintains sterol homeostasis [94, 113, 114]. Interestingly, the loci of another G class transporter, ABCG1, was also found to be induced by LXR-dependent signaling, suggesting that ABCG1 may also function in cholesterol homeostasis [115]. This hypothesis was supported by studies of Klucken et al who showed that antisense oligonucleotide suppression of ABCG1 in human macrophages resulted in decreased lipid efflux to HDL [116]. Subsequently, it was demonstrated that ABCG1 stimulates efflux of cholesterol and other phospholipids to HDL and that siRNA-mediated knockdown of ABCG1 suppresses cholesterol efflux to mature HDL but not to lipid free apoA-I [117, 118]. Although expression of ABCG1 did not increase cellular binding of HDL, it did increase the oxidation sensitivity of cellular cholesterol in the absence of HDL, suggesting that ABCG1 (like ABCA1) can also modify plasma membrane cholesterol domains such that they are more accessible to cholesterol oxidase [32, 117]. Whether the cholesterol in these ABCG1 modified domains is spatially distinct from the lipid domains generated by ABCA1 remains to be investigated.

To date, no human pathologies have been linked to mutation of ABCG1 and studies evaluating the physiological relevance of ABCG1 transport activity have relied mainly on mouse models where the endogenous the Abcg1 locus is deleted or human ABCG1 has been over-expressed. Kennedy et al first reported that Abcg1-/- animals are viable and do not display an overt dyslipidemia when maintained on a chow diet [119]. However, when fed a high fat diet, the null animals accumulated significantly more cholesterol, phospholipid and triglyceride in the liver and lungs. Conversely, over-expression of human ABCG1 reduced lipid accumulation in these tissues. Despite these observations, when administered a high fat diet, loss of total body ABCG1 transport did not significantly accelerate atherosclerosis, and loss of macrophage ABCG1 in the context of the Ldlr-/- or ApoE-/- atherosclerosis models has been variously reported to be either pro or anti-atherosclerotic [120-123]. These results indicate that loss of ABCG1 alone does not markedly impact atherosclerosis. In contrast, Yvan-Charvet et al found that Ldlr+/- mice had significantly greater atherosclerosis when transplanted with Abca1-/- Abcg1-/- bone marrow as compared to recipients receiving wild type or Abca1-/- bone marrow [75]. Out et al also reported that when Abca1-/- Abcg1-/- bone marrow was transplanted into Ldlr-/- recipient mice there was a marked accumulation of lipid in the liver, lung and spleen as compared to recipients receiving marrow lacking only ABCA1 or ABCG1. However, in the context of a Ldlr-/- recipient loss of ABCG1 did not significantly worsen atherosclerosis beyond that caused by the loss of only ABCA1 [124]. Taken together, these studies indicate that ABCG1 plays a primary role in maintaining lipid homeostasis in the lung and other tissues, but unlike ABCA1, it does not have a rate-limiting role in maintaining plasma HDL cholesterol levels. Likewise, loss of ABCG1 alone has not been found to markedly accelerate atherosclerosis. However, in spite of having a varied effect on atherosclerosis, ABCG1 along with ABCA1 has been reported to significantly affect macrophage reverse cholesterol transport as assessed by the peritoneal injection model developed by the Daniel Rader laboratory [125].

Although it remains unclear whether ABCG1 activity is atheroprotective, a series of reports do suggest lipid transport mediated by ABCG1 and ABCA1 has potent anti-inflammatory properties. Francone et al first reported that Ldlr-/- Abca1-/- mice when challenged by an intraperitoneal injection of bacterial lipopolysaccaride (LPS) the circulating levels of MCP-1, TNF-α and IL-6 were elevated 8-fold relative to control Ldlr-/- mice treated with LPS [126]. Subsequent studies by Koseki et al have further shown that cultured Abca1-/- macrophages secrete greater amounts of TNF-α in response to LPS and that this response was associated with increased levels of cell surface cholesterol in lipid rafts [127]. Moreover, Zhu et al reported similar findings and found the LPS hypersensitivity displayed by Abca1-/- macrophages required expression of MyD88, an adaptor protein that mediates LPS signaling initiated by the Toll-like receptor 4 [128]. Likewise, Yvan-Charvet et al found macrophages lacking either ABCG1, or both ABCG1 and ABCA1 secrete significantly more cytokines and chemokines, a finding that may provide an explanation for the increased tissue infiltration of the heart by macrophages and other inflammatory cells observed in animals receiving Abca1-/- Abcg1-/- bone marrow transplants [75]. In cell culture studies, this pro-inflammatory phenotype of the Abca1-/-Abcg1-/- macrophages was associated with an increased sensitivity to undergo apoptosis when the cells were exposed to acetylated or oxidized LDL in the presence of an ACAT inhibitor. These treatments exacerbate free cholesterol levels and the general consensus of the above studies was that the anti-inflammatory properties of ABCA1 and ABCG1 were being mediated by their ability to modulate free cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane and its distribution in lipid rafts. However, recent work by Tang et al. suggests that not all of the anti-inflammatory properties of ABCA1 are a consequence of its lipid transport activity [129]. Here it was shown that ABCA1 directly interacts with the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), and this bound JAK2 becomes phosphorylated upon incubating cells with apoA-I. Phosphorylated STAT-3, a transcription factor that mediates JAK2 signaling responses, was also found to bind ABCA1 in an apoA-I dependent manner. Significantly, ABCA1 mutations that disrupt the ABCA1/STAT-3 complex did not affect ABCA1 lipid efflux, but did block the ability of ABCA1 to suppress cytokine secretion in response to LPS. Thus, these results suggest that in addition to the ability of ABCA1 influence inflammatory signaling pathways indirectly by modifying cell surface lipid domains, ABCA1 may also directly act as an anti-inflammatory receptor by inducing signaling through the JAK2/STAT3 pathway in response to binding lipid poor apoA-I. This result is particularly interesting in light of the profound remodeling that HDL undergoes during the acute inflammatory response where serum amyloid A displaces apoA-I from HDL particles [130, 131]. Could this liberated lipid poor apoA-I now interact with ABCA1 in order to tamp down the inflammatory response by inducing the JAK2/STAT3 pathway as part of the resolution phase of an infection?

As indicated above the role that the anti-inflammatory properties that ABCA1 and ABCG1 may play in preventing atherosclerosis is in need of clarification. However, loss of LXR signaling and ABCG1 transport activity has been associated with a hyper-proliferation of T cells in response to antigenic stimulation [132, 133]. Moreover, LXR transcriptional responses in phagocytes ingesting apoptotic cells has also been shown to be important in inducing immune tolerance in mice. This latter effect of LXR signaling in preventing autoimmune reactions dose not appear to be acting through ABCA1 or ABCG1, thus one should be cautious in assuming that all the anti-inflammatory effects of LXR ligands are related to their ability to induce expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1. Furthermore, other receptors besides ABCA1 and ABCG1 that modulate HDL levels and flux of cholesterol through the RCT pathway have also been reported to have anti-inflammatory properties. In this regard the activity of scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) is of interest. SR-BI is structurally distinct from the ABC transporters and consists of only one extracellular loop and two transmembrane domains [134]. However, SR-B1 is able to bind mature HDL and through a process termed selective lipid uptake is able to mediate bulk transfer of cholesterol esters from the bound HDL to the cell [135]. SR-BI is prominently expressed in the liver and other steroidogenic organs but can also be found in macrophages and endothelial cells. In mice loss of SR-B1 disrupts selective cholesterol ester uptake by the liver, which increases the size and level of circulating HDL particles, and which is associated with increased atherosclerosis [136]. Although SR-BI has been reported to influence macrophage cholesterol efflux in vitro, recent in vivo studies have indicated that liver expressed SR-BI is most important for mediating reverse cholesterol transport from HDL [125, 137]. However, Guo et al have recently reported that in mice SR-BI protects against septic death and that macrophage expressed SR-B1 can suppress LPS induced cytokine secretion through a process that inhibits NF-κB activation [138]. Interestingly, like the ability of ABCA1 to modulate activation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway, the ability of SR-BI to inhibit NF-κB activation can proceed in the absence of SR-BI lipid transfer activity. Whether this indicates SR-BI can also directly act as an anti-inflammatory receptor remains to be investigated, particularly since it has also been reported that the SR-BI mediated delivery of HDL to the adrenal gland is important in protecting against LPS endotoxemia [139]. Here the SR-BI delivered cholesterol is required for production of glucocorticoids that also have anti-inflammatory properties. Thus, like ABCA1, SR-B1 appears to modulate inflammatory signaling both indirectly by its lipid transport activity and possibly by other mechanisms where it may act directly as a receptor in signal transduction cascades.

Therapeutic approaches to stimulate ABC transporter activity and HDL reverse cholesterol transport

As HDL cholesterol levels are consistently associated with a lower incidence of cardiovascular disease, a number of approaches are in development to raise HDL levels in an effort to reduce disease risk beyond that provided by statins, which act to inhibit endogenous synthesis of cholesterol. One approach is based upon the use of pharmacologic doses of niacin, also known as nicotinic acid or vitamin B3, which at high doses activates G-protein coupled receptors in adipocytes resulting in a decrease in triglyceride lipolysis and free fatty acid release [140]. Niacin also represses hepatic VLDL secretion and raises HDL levels. The drug has a long history of clinical use and a number of trials have shown that as a monotherapy or in combination with statin treatment, niacin reduces myocardial infarctions and total mortality [141]. Most recently in combination with statin therapy, niacin was found to have a greater efficacy in reducing carotid atherosclerosis compared to ezetimibe, which blocks intestinal absorbtion of cholesterol [142]. The drawback to niacin use is poor tolerability since it causes skin flushing by inducing dendritic cell prostaglandin secretion. However, it has recently been reported that high dose niacin therapy is better tolerated when flushing is blocked using a prostaglandin antagonist (laropiprant, MK-0524A, Merck) [143]. In a follow-up study comparing an extended release niacin/laropiprant treatment versus titrated niacin, there was a significant increase in adverse events associated with the combined treatment but this was thought to be due to the increased dose of niacin tolerated when taken with laropiprant and not due to laropiprant itself [144], a finding that will have to be substantiated before laropiprant is approved for use in the United States (at present the niacin/laropiprant combination is apporved for usage in the European Union).

A newer approach to elevating HDL levels is to inhibit cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP). This plasma protein directly associates with HDL, and through a carrier mechanism off-loads cholesteryl esters from the HDL particle and transfers it to VLDL particles [145]. CETP was thought to be an attractive target because individuals have been identified with loss of function CETP mutations that associate with increased levels of HDL cholesterol and reduced cardiovascular disease, although the latter association was found to be variable [146-148]. Since antibodies and small molecule inhibitors of CETP were also found to reduce diet induced atherosclerosis in rabbits, clinical trials have been initiated to test if the HDL raising properties of these compounds reduced the progression of coronary atherosclerosis [149]. Unexpectedly, the trial assessing torcetrapib (Pfizer) had to be halted because of a significant increase in cardiovascular disease events as well as increases non-CVD deaths in individuals treated with both torcetrapib and atorvastatin[150-152]. These events occurred in spite of 72% increase in HDL cholesterol and a 25% decrease in LDL cholesterol and may be due to a compound specific off target effect that also raised systolic blood pressure by up to 15 mm Hg. More recently, phase II trials assessing the efficacy and safety of two additional CETP inhibitors (anacetrapib and dalcetrapib) have been reported where both compounds were found to significantly raise HDL but were not associated with significant increases in blood pressure or adverse events [153-156]. Thus, it remains an open question as to whether inhibition of CETP is a viable means to raise HDL and reduce cardiovascular disease risk.

Finally, approaches expected to directly impact cholesterol efflux mediated by ABCA1, ABCG1 and the ABCG5/8 transporters are also being developed. Because synthetic LXR agonists are known to induce the transcription of these transporters as well as other molecules involved in the trafficking of lipids through the RCT pathway including apolipoprotein E [157], it is thought that these compounds would raise HDL and reduce atherosclerosis. Initial studies using the first generation of LXR agonists in mice suggested they were able reduce atherosclerosis. However, due to their induction of fatty acid synthesis, these compounds also caused liver steatosis, particularly in the db/db mouse obesity model [158-160] [161]. More recently, partial LXR agonists that still induce the expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1 but not fatty acid synthesis have been reported and one of these has been tested for safety in humans (LXR-623) [162-164]. However, an increase in adverse neurologic events were noted in individuals receiving the higher doses of the LXR-623 [162].

Besides transcriptionally activating RCT, other studies have involved infusion of lipid free apoA-I, apoA-I peptides or plasma with selectively delipidated HDL in efforts to directly provide increased levels of ABCA1 acceptor ligands [165-168]. Using a Milano variant of apoA-I, these infusions were reported to significantly reduce atherosclerotic plaque burden, but in larger studies with wt ApoA-I/phospholipid complexes this approach was associated with more mild reductions in atherosclerosis and significant hepatoxicity was observed in individuals receiving higher doses of the recombinant apoA-I lipid complex. Thus, although a number of approaches have been utilized to raise HDL levels and increase the flux of lipid through the RCT pathway, at present the efficacy and safety of these potential therapies remains an open question.

Conclusion

Since the discovery of ABCA1 and ABCG5/G8 as determinants of Tangier disease and sitosterolemia respectively, a global research effort has provided significant mechanistic insights into how these transporters maintain lipid homeostasis by a process termed reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). Although a significant amount of evidence suggests that this process protects against the development of atherosclerosis, more recent genome wide association studies have not strongly linked genetic variation in these transporters to the incidence of cardiovascular disease in the general population despite the finding that polymorphisms in ABCA1 that modulate HDL levels in the general population. Given this disconnect and the safety issues that have stymied efforts to develop compounds that raise HDL and increase flux of lipids through the RCT pathway, it is clear much insight is still needed into the basic mechanisms of RCT and why HDL cholesterol levels are inversely associated with the incidence of cardiovascular disease.

Figure 2. Anti-inflammatory properties of HDL and ABC transporters.

Bacterial sepsis can lead to the systemic circulation of microbial cell wall constituents such as lipopolysaccaride (LPS). This leads to an acute inflammatory response and a remodeling of HDL particles with serum amyloid A (SAA) displacing apoA-I. It has long been appreciated that HDL can play an anti-inflammatory role by binding circulating LPS and blocking its ability to trigger innate immune signaling cascades mediated by the CD14/MD2/Toll like Receptor 4 complex. However, more recent data indicates ABCA1 and ABCG1 mediate additional mechanisms by which these transporters can inhibit TLR4 signaling. Through their lipid transport activity ABCA1 and ABCG1 can reduce cell surface lipid rafts, and as a consequence inhibit TLR4 signal transduction, presumably because the formation and clustering of the CD14/MD2/TLR4 complex depends upon these lipid microdomains. Moreover, triggered by the binding of lipid poor apoA-I released by remodeled HDL particles, ABCA1 may directly act as a receptor by binding Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) and the transcriptional factor STAT3, which inhibits downstream signaling steps that macrophages use to express and secrete inflammatory cytokines. However, not all anti-inflammatory properties of the RCT process can be ascribed to the activity of ABCA1 and ABCG1 since scavenger receptor BI (SR-BI) expressed in macrophages and in adrenal tissues has also been reported to protect against endotoxemia by respectively inhibiting TLR4 signaling and stimulating glucocorticoid production (GC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald ML, Xavier R, Haley KJ, et al. ABCA3 inactivation in mice causes respiratory failure, loss of pulmonary surfactant, and depletion of lung phosphatidylglycerol. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(3):621–32. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600449-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(2):112–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wymann MP, Schneiter R. Lipid signalling in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(2):162–76. doi: 10.1038/nrm2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuo Y, Zhuang DZ, Han R, et al. ABCA12 Maintains the Epidermal Lipid Permeability Barrier by Facilitating Formation of Ceramide Linoleic Esters. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(52):36624–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807377200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rader DJ, Cohen J, Hobbs HH. Monogenic hypercholesterolemia: new insights in pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(12):1795–803. doi: 10.1172/JCI18925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fredrickson DSAP, Avioli LV, Goodman DW, Goodman HC. Tangier disease. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:1016–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fredrickson DS. The Inheritance Of High Density Lipoprotein Deficiency (Tangier Disease) J Clin Invest. 1964;43:228–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI104907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Assmann G, Herbert PN, Fredrickson DS, Forte T. Isolation and characterization of an abnormal high density lipoprotein in Tangier Diesase. J Clin Invest. 1977;60(1):242–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI108761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assmann G, Simantke O, Schaefer HE, Smootz E. Characterization of high density lipoproteins in patients heterozygous for Tangier disease. J Clin Invest. 1977;60(5):1025–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI108853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assmann G, Smootz E, Adler K, Capurso A, Oette K. The lipoprotein abnormality in Tangier disease: quantitation of A apoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1977;59(3):565–75. doi: 10.1172/JCI108672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bojanovski D, Gregg RE, Zech LA, et al. In vivo metabolism of proapolipoprotein A-I in Tangier disease. J Clin Invest. 1987;80(6):1742–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI113266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaefer EJ, Blum CB, Levy RI, et al. Metabolism of high-density lipoprotein apolipoproteins in Tangier disease. N Engl J Med. 1978;299(17):905–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197810262991701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaefer EJ, Kay LL, Zech LA, Brewer HB., Jr Tangier disease. High density lipoprotein deficiency due to defective metabolism of an abnormal apolipoprotein A-i (ApoA-ITangier) J Clin Invest. 1982;70(5):934–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI110705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zannis VI, Lees AM, Lees RS, Breslow JL. Abnormal apoprotein A-I isoprotein composition in patients with Tangier disease. J Biol Chem. 1982;257(9):4978–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis GA, Knopp RH, Oram JF. Defective removal of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids by apolipoprotein A-I in Tangier Disease. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(1):78–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI118082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Remaley AT, Schumacher UK, Stonik JA, Farsi BD, Nazih H, Brewer HB., Jr Decreased reverse cholesterol transport from Tangier disease fibroblasts. Acceptor specificity and effect of brefeldin on lipid efflux. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(9):1813–21. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.9.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogler G, Trumbach B, Klima B, Lackner KJ, Schmitz G. HDL-mediated efflux of intracellular cholesterol is impaired in fibroblasts from Tangier disease patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15(5):683–90. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rust S, Walter M, Funke H, et al. Assignment of Tangier disease to chromosome 9q31 by a graphical linkage exclusion strategy. Nat Genet. 1998;20(1):96–8. doi: 10.1038/1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodzioch M, Orso E, Klucken J, et al. The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease [see comments] Nat Genet. 1999;22(4):347–51. doi: 10.1038/11914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks-Wilson A, Marcil M, Clee SM, et al. Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency [see comments ] Nat Genet. 1999;22(4):336–45. doi: 10.1038/11905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawn RM, Wade DP, Garvin MR, et al. The Tangier disease gene product ABC1 controls the cellular apolipoprotein-mediated lipid removal pathway [see comments] J Clin Invest. 1999;104(8):R25–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI8119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rust S, Rosier M, Funke H, et al. Tangier disease is caused by mutations in the gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 [see comments] Nat Genet. 1999;22(4):352–5. doi: 10.1038/11921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chroni A, Liu T, Fitzgerald ML, Freeman MW, Zannis VI. Cross-linking and lipid efflux properties of apoA-I mutants suggest direct association between apoA-I helices and ABCA1. Biochemistry. 2004;43(7):2126–39. doi: 10.1021/bi035813p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fitzgerald ML, Morris AL, Chroni A, Mendez AJ, Zannis VI, Freeman MW. ABCA1 and amphipathic apolipoproteins form high-affinity molecular complexes required for cholesterol efflux. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(2):287–94. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300355-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzgerald ML, Morris AL, Rhee JS, Andersson LP, Mendez AJ, Freeman MW. Naturally occurring mutations in the largest extracellular loops of ABCA1 can disrupt its direct interaction with apolipoprotein A-I. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):33178–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204996200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oram JF, Lawn RM, Garvin MR, Wade DP. ABCA1 is the cAMP-inducible apolipoprotein receptor that mediates cholesterol secretion from macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(44):34508–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang N, Silver DL, Costet P, Tall AR. Specific binding of ApoA-I, enhanced cholesterol efflux, and altered plasma membrane morphology in cells expressing ABC1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(42):33053–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denis M, Haidar B, Marcil M, Bouvier M, Krimbou L, Genest J., Jr Molecular and cellular physiology of apolipoprotein A-I lipidation by the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279(9):7384–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rigot V, Hamon Y, Chambenoit O, Alibert M, Duverger N, Chimini G. Distinct sites on ABCA1 control distinct steps required for cellular release of phospholipids. J Lipid Res. 2002;43(12):2077–86. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200279-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hassan HH, Denis M, Lee DY, et al. Identification of an ABCA1-dependent phospholipid-rich plasma membrane apolipoprotein A-I binding site for nascent HDL formation: implications for current models of HDL biogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(11):2428–42. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700206-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Landry YD, Denis M, Nandi S, Bell S, Vaughan AM, Zha X. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 expression disrupts raft membrane microdomains through its ATPase-related functions. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(47):36091–101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaughan AM, Oram JF. ABCA1 redistributes membrane cholesterol independent of apolipoprotein interactions. J Lipid Res. 2003;44(7):1373–80. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300078-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vedhachalam C, Duong PT, Nickel M, et al. Mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1-mediated cellular lipid efflux to apolipoprotein A-I and formation of high density lipoprotein particles. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(34):25123–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin G, Oram JF. Apolipoprotein binding to protruding membrane domains during removal of excess cellular cholesterol. Atherosclerosis. 2000;149(2):359–70. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith JD, Waelde C, Horwitz A, Zheng P. Evaluation of the role of phosphatidylserine translocase activity in ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(20):17797–803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson P, Halleck MS, Malowitz J, et al. Transbilayer phospholipid movements in ABCA1-deficient cells. PLoS One. 2007;2(1):e729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi Y, Smith JD. Cholesterol efflux to apolipoprotein AI involves endocytosis and resecretion in a calcium-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(20):11358–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neufeld EB, Remaley AT, Demosky SJ, et al. Cellular localization and trafficking of the human ABCA1 transporter. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(29):27584–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neufeld EB, Stonik JA, Demosky SJ, Jr, et al. The ABCA1 transporter modulates late endocytic trafficking: insights from the correction of the genetic defect in Tangier disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(15):15571–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen W, Wang N, Tall AR. A PEST deletion mutant of ABCA1 shows impaired internalization and defective cholesterol efflux from late endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(32):29277–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505566200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hassan HH, Bailey D, Lee DY, et al. Quantitative analysis of ABCA1-dependent compartmentalization and trafficking of apolipoprotein A-I: implications for determining cellular kinetics of nascent high density lipoprotein biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(17):11164–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707720200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Denis M, Landry YD, Zha X. ATP-binding cassette A1-mediated lipidation of apolipoprotein A-I occurs at the plasma membrane and not in the endocytic compartments. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):16178–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709597200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faulkner LE, Panagotopulos SE, Johnson JD, et al. An analysis of the role of a retroendocytosis pathway in ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA1) - mediated cholesterol efflux from macrophages. J Lipid Res. 2008 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800048-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bared SM, Buechler C, Boettcher A, et al. Association of ABCA1 with syntaxin 13 and flotillin-1 and enhanced phagocytosis in tangier cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(12):5399–407. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowden K, Ridgway ND. OSBP negatively regulates ABCA1 protein stability. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(26):18210–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800918200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buechler C, Boettcher A, Bared SM, Probst MC, Schmitz G. The carboxyterminus of the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 interacts with a beta2-syntrophin/utrophin complex. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293(2):759–65. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drobnik W, Borsukova H, Bottcher A, et al. Apo AI/ABCA1-dependent and HDL3-mediated lipid efflux from compositionally distinct cholesterol-based microdomains. Traffic. 2002;3(4):268–78. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.030404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munehira Y, Ohnishi T, Kawamoto S, et al. Alpha1-syntrophin modulates turnover of ABCA1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(15):15091–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nofer JR, Feuerborn R, Levkau B, Sokoll A, Seedorf U, Assmann G. Involvement of Cdc42 signaling in apoA-I-induced cholesterol efflux. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(52):53055–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nofer JR, Remaley AT, Feuerborn R, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I activates Cdc42 signaling through the ABCA1 transporter. J Lipid Res. 2006;47(4):794–803. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500502-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okuhira K, Fitzgerald ML, Sarracino DA, et al. Purification of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 and associated binding proteins reveals the importance of beta1-syntrophin in cholesterol efflux. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(47):39653–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tamehiro N, Zhou S, Okuhira K, et al. SPTLC1 binds ABCA1 to negatively regulate trafficking and cholesterol efflux activity of the transporter. Biochemistry. 2008;47(23):6138–47. doi: 10.1021/bi800182t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsukamoto K, Hirano K, Tsujii K, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporter-1 induces rearrangement of actin cytoskeletons possibly through Cdc42/N-WASP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287(3):757–65. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan D, Lehto M, Rasilainen L, et al. Oxysterol binding protein induces upregulation of SREBP-1c and enhances hepatic lipogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(5):1108–14. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.138545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan D, Mayranpaa MI, Wong J, et al. OSBP-related protein 8 (ORP8) suppresses ABCA1 expression and cholesterol efflux from macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(1):332–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705313200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoffman HN, Fredrickson DS. Tangier disease (familial high density lipoprotein deficiency). Clinical and genetic features in two adults. Am J Med. 1965;39(4):582–93. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(65)90081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schaefer EJ, Zech LA, Schwartz DE, Brewer HB., Jr Coronary heart disease prevalence and other clinical features in familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency (Tangier disease) Ann Intern Med. 1980;93(2):261–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-2-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clee SM, Kastelein JJ, van Dam M, et al. Age and residual cholesterol efflux affect HDL cholesterol levels and coronary artery disease in ABCA1 heterozygotes. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(10):1263–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI10727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen JC, Kiss RS, Pertsemlidis A, Marcel YL, McPherson R, Hobbs HH. Multiple rare alleles contribute to low plasma levels of HDL cholesterol. Science. 2004;305(5685):869–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1099870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kathiresan S, Melander O, Guiducci C, et al. Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat Genet. 2008;40(2):189–97. doi: 10.1038/ng.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Willer CJ, Sanna S, Jackson AU, et al. Newly identified loci that influence lipid concentrations and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40(2):161–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benton JL, Ding J, Tsai MY, et al. Associations between two common polymorphisms in the ABCA1 gene and subclinical atherosclerosis: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Atherosclerosis. 2007;193(2):352–60. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clee SM, Zwinderman AH, Engert JC, et al. Common genetic variation in ABCA1 is associated with altered lipoprotein levels and a modified risk for coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;103(9):1198–205. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jensen MK, Pai JK, Mukamal KJ, Overvad K, Rimm EB. Common genetic variation in the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1, plasma lipids, and risk of coronary heart disease. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195(1):e172–80. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Jensen GB, Steffensen R, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Genetic variation in ABCA1 predicts ischemic heart disease in the general population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(1):180–6. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Schnohr P, Steffensen R, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Mutation in ABCA1 predicted risk of ischemic heart disease in the Copenhagen City Heart Study Population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(8):1516–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Stene MC, et al. Association of loss-of-function mutations in the ABCA1 gene with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and risk of ischemic heart disease. Jama. 2008;299(21):2524–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morgan TM, Krumholz HM, Lifton RP, Spertus JA. Nonvalidation of reported genetic risk factors for acute coronary syndrome in a large-scale replication study. Jama. 2007;297(14):1551–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.14.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chung S, Gebre AK, Seo J, Shelness GS, Parks JS. A novel role for ABCA1-generated large pre-beta migrating nascent HDL in the regulationof hepatic VLDL triglyceride secretion. J Lipid Res. 2009 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aiello RJ, Brees D, Bourassa PA, et al. Increased atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice with inactivation of ABCA1 in macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22(4):630–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000014804.35824.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Joyce CW, Wagner EM, Basso F, et al. ABCA1 overexpression in the liver of LDLr-KO mice leads to accumulation of pro-atherogenic lipoproteins and enhanced atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(44):33053–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singaraja RR, Fievet C, Castro G, et al. Increased ABCA1 activity protects against atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(1):35–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI15748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Eck M, Bos IS, Kaminski WE, et al. Leukocyte ABCA1 controls susceptibility to atherosclerosis and macrophage recruitment into tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(9):6298–303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092327399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brunham LR, Singaraja RR, Duong M, et al. Tissue-specific roles of ABCA1 influence susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(4):548–54. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yvan-Charvet L, Ranalletta M, Wang N, et al. Combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes foam cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(12):3900–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI33372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhattacharyya AK, Connor WE. Beta-sitosterolemia and xanthomatosis. A newly described lipid storage disease in two sisters. J Clin Invest. 1974;53(4):1033–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI107640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Katayama T, Satoh T, Yagi T, et al. A 19-year-old man with myocardial infarction and sitosterolemia. Intern Med. 2003;42(7):591–4. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kolovou G, Voudris V, Drogari E, Palatianos G, Cokkinos DV. Coronary bypass grafts in a young girl with sitosterolemia. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(6):965–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Miettinen TA. Phytosterolaemia, xanthomatosis and premature atherosclerotic arterial disease: a case with high plant sterol absorption, impaired sterol elimination and low cholesterol synthesis. Eur J Clin Invest. 1980;10(1):27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1980.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mymin D, Wang J, Frohlich J, Hegele RA. Image in cardiovascular medicine. Aortic xanthomatosis with coronary ostial occlusion in a child homozygous for a nonsense mutation in ABCG8. Circulation. 2003;107(5):791. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000050545.21826.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Salen G, Horak I, Rothkopf M, et al. Lethal atherosclerosis associated with abnormal plasma and tissue sterol composition in sitosterolemia with xanthomatosis. J Lipid Res. 1985;26(9):1126–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Salen G, Shore V, Tint GS, et al. Increased sitosterol absorption, decreased removal, and expanded body pools compensate for reduced cholesterol synthesis in sitosterolemia with xanthomatosis. J Lipid Res. 1989;30(9):1319–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Salen G, Tint GS, Shefer S, Shore V, Nguyen L. Increased sitosterol absorption is offset by rapid elimination to prevent accumulation in heterozygotes with sitosterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12(5):563–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beaty TH, Kwiterovich PO, Jr, Khoury MJ, et al. Genetic analysis of plasma sitosterol, apoprotein B, and lipoproteins in a large Amish pedigree with sitosterolemia. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;38(4):492–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gregg RE, Connor WE, Lin DS, Brewer HB., Jr Abnormal metabolism of shellfish sterols in a patient with sitosterolemia and xanthomatosis. J Clin Invest. 1986;77(6):1864–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI112513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Morganroth J, Levy RI, McMahon AE, Gotto AM., Jr Pseudohomozygous type II hyperlipoproteinemia. J Pediatr. 1974;85(5):639–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(74)80506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nguyen LB, Shefer S, Salen G, et al. A molecular defect in hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis in sitosterolemia with xanthomatosis. J Clin Invest. 1990;86(3):923–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI114794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Belamarich PF, Deckelbaum RJ, Starc TJ, Dobrin BE, Tint GS, Salen G. Response to diet and cholestyramine in a patient with sitosterolemia. Pediatrics. 1990;86(6):977–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salen G, Kwiterovich PO, Jr, Shefer S, et al. Increased plasma cholestanol and 5 alpha-saturated plant sterol derivatives in subjects with sitosterolemia and xanthomatosis. J Lipid Res. 1985;26(2):203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Patel SB, Salen G, Hidaka H, et al. Mapping a gene involved in regulating dietary cholesterol absorption. The sitosterolemia locus is found at chromosome 2p21. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(5):1041–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, et al. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science. 2000;290(5497):1771–5. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee MH, Lu K, Hazard S, et al. Identification of a gene, ABCG5, important in the regulation of dietary cholesterol absorption. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):79–83. doi: 10.1038/83799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lu K, Lee MH, Hazard S, et al. Two genes that map to the STSL locus cause sitosterolemia: genomic structure and spectrum of mutations involving sterolin-1 and sterolin-2, encoded by ABCG5 and ABCG8, respectively. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69(2):278–90. doi: 10.1086/321294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Repa JJ, Berge KE, Pomajzl C, Richardson JA, Hobbs H, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8 by the liver X receptors alpha and beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(21):18793–800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mulligan JD, Flowers MT, Tebon A, et al. ABCA1 is essential for efficient basolateral cholesterol efflux during the absorption of dietary cholesterol in chickens. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(15):13356–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Murthy S, Born E, Mathur SN, Field FJ. LXR/RXR activation enhances basolateral efflux of cholesterol in CaCo-2 cells. J Lipid Res. 2002;43(7):1054–64. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m100358-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Neufeld EB, Demosky SJ, Jr, Stonik JA, et al. The ABCA1 transporter functions on the basolateral surface of hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297(4):974–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ohama T, Hirano K, Zhang Z, et al. Dominant expression of ATP-binding cassette transporter-1 on basolateral surface of Caco-2 cells stimulated by LXR/RXR ligands. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296(3):625–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00853-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Graf GA, Li WP, Gerard RD, et al. Coexpression of ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCG5 and ABCG8 permits their transport to the apical surface. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(5):659–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI16000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Klett EL, Lee MH, Adams DB, Chavin KD, Patel SB. Localization of ABCG5 and ABCG8 proteins in human liver, gall bladder and intestine. BMC Gastroenterol. 2004;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Graf GA, Yu L, Li WP, et al. ABCG5 and ABCG8 are obligate heterodimers for protein trafficking and biliary cholesterol excretion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(48):48275–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang DW, Graf GA, Gerard RD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Functional asymmetry of nucleotide-binding domains in ABCG5 and ABCG8. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(7):4507–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Glueck CJ, Speirs J, Tracy T, Streicher P, Illig E, Vandegrift J. Relationships of serum plant sterols (phytosterols) and cholesterol in 595 hypercholesterolemic subjects, and familial aggregation of phytosterols, cholesterol, and premature coronary heart disease in hyperphytosterolemic probands and their first-degree relatives. Metabolism. 1991;40(8):842–8. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(91)90013-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sudhop T, Gottwald BM, von Bergmann K. Serum plant sterols as a potential risk factor for coronary heart disease. Metabolism. 2002;51(12):1519–21. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.36298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Assmann G, Cullen P, Erbey J, Ramey DR, Kannenberg F, Schulte H. Plasma sitosterol elevations are associated with an increased incidence of coronary events in men: results of a nested case-control analysis of the Prospective Cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;16(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Basso F, Freeman LA, Ko C, et al. Hepatic ABCG5/G8 overexpression reduces apoB-lipoproteins and atherosclerosis when cholesterol absorption is inhibited. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(1):114–26. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600353-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wilund KR, Yu L, Xu F, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. High-level expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 attenuates diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in Ldlr-/- mice. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(8):1429–36. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400167-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu JE, Basso F, Shamburek RD, et al. Hepatic ABCG5 and ABCG8 overexpression increases hepatobiliary sterol transport but does not alter aortic atherosclerosis in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(22):22913–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402838200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wilund KR, Yu L, Xu F, et al. No association between plasma levels of plant sterols and atherosclerosis in mice and men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(12):2326–32. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000149140.00499.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Silbernagel G, Fauler G, Renner W, et al. The relationships of cholesterol metabolism and plasma plant sterols with the severity of coronary artery disease. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(2):334–41. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P800013-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Buch S, Schafmayer C, Volzke H, et al. A genome-wide association scan identifies the hepatic cholesterol transporter ABCG8 as a susceptibility factor for human gallstone disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39(8):995–9. doi: 10.1038/ng2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gylling H, Hallikainen M, Pihlajamaki J, et al. Polymorphisms in the ABCG5 and ABCG8 genes associate with cholesterol absorption and insulin sensitivity. J Lipid Res. 2004;45(9):1660–5. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300522-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Costet P, Luo Y, Wang N, Tall AR. Sterol-dependent transactivation of the ABC1 promoter by the liver X receptor/retinoid X receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(36):28240–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Venkateswaran A, Laffitte BA, Joseph SB, et al. Control of cellular cholesterol efflux by the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(22):12097–102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200367697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Venkateswaran A, Repa JJ, Lobaccaro JM, Bronson A, Mangelsdorf DJ, Edwards PA. Human white/murine ABC8 mRNA levels are highly induced in lipid-loaded macrophages. A transcriptional role for specific oxysterols. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(19):14700–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Klucken J, Buchler C, Orso E, et al. ABCG1 (ABC8), the human homolog of the Drosophila white gene, is a regulator of macrophage cholesterol and phospholipid transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(2):817–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Vaughan AM, Oram JF. ABCG1 redistributes cell cholesterol to domains removable by high density lipoprotein but not by lipid-depleted apolipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(34):30150–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang N, Lan D, Chen W, Matsuura F, Tall AR. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(26):9774–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403506101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kennedy MA, Barrera GC, Nakamura K, et al. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell Metab. 2005;1(2):121–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Baldan A, Pei L, Lee R, et al. Impaired development of atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic Ldlr-/- and ApoE-/- mice transplanted with Abcg1-/- bone marrow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(10):2301–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000240051.22944.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lammers B, Out R, Hildebrand RB, et al. Independent protective roles for macrophage Abcg1 and Apoe in the atherosclerotic lesion development. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205(2):420–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Out R, Hoekstra M, Hildebrand RB, et al. Macrophage ABCG1 deletion disrupts lipid homeostasis in alveolar macrophages and moderately influences atherosclerotic lesion development in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(10):2295–300. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000237629.29842.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ranalletta M, Wang N, Han S, Yvan-Charvet L, Welch C, Tall AR. Decreased atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice transplanted with Abcg1-/- bone marrow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(10):2308–15. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000242275.92915.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Out R, Hoekstra M, Habets K, et al. Combined deletion of macrophage ABCA1 and ABCG1 leads to massive lipid accumulation in tissue macrophages and distinct atherosclerosis at relatively low plasma cholesterol levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(2):258–64. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wang X, Collins HL, Ranalletta M, et al. Macrophage ABCA1 and ABCG1, but not SR-BI, promote macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(8):2216–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI32057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Francone OL, Royer L, Boucher G, et al. Increased cholesterol deposition, expression of scavenger receptors, and response to chemotactic factors in Abca1-deficient macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(6):1198–205. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000166522.69552.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Koseki M, Hirano K, Masuda D, et al. Increased lipid rafts and accelerated lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion in Abca1-deficient macrophages. J Lipid Res. 2007;48(2):299–306. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600428-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhu X, Lee JY, Timmins JM, et al. Increased cellular free cholesterol in macrophage-specific Abca1 knock-out mice enhances pro-inflammatory response of macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(34):22930–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801408200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tang C, Liu Y, Kessler PS, Vaughan AM, Oram JF. The macrophage cholesterol exporter ABCA1 functions as an anti-inflammatory receptor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(47):32336–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Jahangiri A, de Beer MC, Noffsinger V, et al. HDL remodeling during the acute phase response. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(2):261–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.178681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]